New Environmental Assessment Reveals Fascinating Alternatives to Land-Based ICBMs

A new Air Force environmental assessment reveals that it considered basing ICBMs in underground railway tunnels––or possibly underwater.

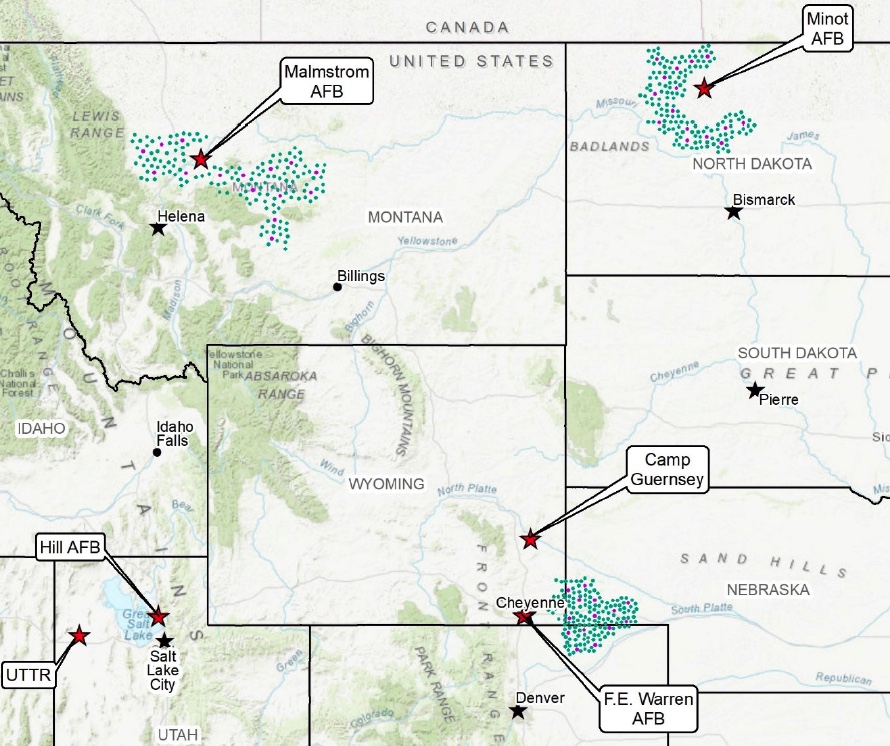

Map of the ICBM missile fields contained within the Air Force’s July 2022 assessment.

On July 1st, the Air Force published its Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for its proposed ICBM replacement program, previously known as the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) and now by its new name, “Sentinel.” The government typically conducts an EIS whenever a federal program could potentially disrupt local water supplies, transportation, socioeconomics, geology, air quality, and other related factors.

A comprehensive environmental assessment is certainly warranted in this case, given the tremendous scale of the Sentinel program––which consists of a like-for-like replacement of all 400 Minuteman III missiles that are currently deployed across Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Wyoming, plus upgrades to the launch facilities, launch control centers, and other supporting infrastructure.

Cover page of the Air Force’s July 2022 Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the GBSD.

The Draft EIS was anxiously awaited by local stakeholders, chambers of commerce, contractors, residents, and… me! Not because I’m losing sleep about whether Sentinel construction will disturb Wyoming’s Western Bumble Bee (although maybe I should be!), but rather because an EIS is also a wonderful repository for juicy, and often new, details about federal programs––and the Sentinel’s Draft EIS is certainly no exception.

Interestingly, the most exciting new details are not necessarily about what the Air Force is currently planning for the Sentinel, but rather about which ICBM replacement options they previously considered as alternatives to the current program of record. These alternatives were assessed during in the Air Force’s 2014 Analysis of Alternatives––a key document that weighs the risks and benefits of each proposed action––however, that document remains classified. Therefore, until they were recently referenced in the July 2022 Draft EIS, it was not clear to the public what the Air Force was actually assessing as alternatives to the current Sentinel program.

Missile alternatives

The Draft EIS notes that the Air Force assessed four potential missile alternatives to the current plan, which involves designing a completely new ICBM:

- Reproducing Minuteman III ICBMs to “existing specifications” by washing out and refilling the first- and second-stage rocket boosters; remanufacturing the third stages and Propulsion System Rocket Engine––the ICBM’s post-boost vehicle; and refurbishing and replacing all other subsystems;

The Air Force appears to have ultimately eliminated all four of these options from consideration because they did not meet all of their “selection standards,” which included criteria like sustainability, performance, safety, riskiness, and capacity for integration into existing or proposed infrastructure.

Of particular interest, however, is the Air Force’s note that the Minuteman III reproduction alternative was eliminated in part because it did not “meet the required performance criteria for ICBMs in the context of modern and evolving threats (e.g., range, payload, and effectiveness.” It is highly significant to state that the Minuteman III cannot meet the required performance criteria for ICBMs, given that the Minuteman III currently performs the ICBM role for the US Air Force and will continue to do so for the next decade.

This statement also suggests that “modern and evolving threats” are driving the need for an operationally improved ICBM; however, it is unclear what the Air Force is referring to, or how these threats would necessarily justify a brand-new ICBM with new capabilities. As I wrote in my March 2021 report, “Siloed Thinking: A Closer Look at the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent,”

“With respect to US-centric nuclear deterrence, what has changed since the end of the Cold War? China is slowly but steadily expanding its nuclear arsenal and suite of delivery systems, and North Korea’s nuclear weapons program continues to mature. However, the range and deployment locations of the US ICBM force would force the missiles to fly over Russian territory in the event that they were aimed at Chinese or North Korean targets, thus significantly increasing the risk of using ICBMs to target either country. Moreover, […] other elements of the US nuclear force––especially SSBNs––could be used to accomplish the ICBM force’s mission under a revised nuclear force posture, potentially even faster and in a more flexible manner. […] It is additionally important to note that even if adversarial missile defenses improved significantly, the ability to evade missile defenses lies with the payload––not the missile itself. By the time that an adversary’s interceptor was able to engage a US ICBM in its midcourse phase of flight, the ICBM would have already shed its boosters, deployed its penetration aids, and would be guided solely by its reentry vehicle. Reentry vehicles and missile boosters can be independently upgraded as necessary, meaning that any concerns about adversarial missile defenses could be mitigated by deploying a more advanced payload on a life-extended Minuteman III ICBM.”

Of additional interest is the passage explaining why the Air Force dismissed the possibility of using the Trident II D5 SLBM as a land-based weapon:

“The D5 is a high-accuracy weapon system capable of engaging many targets simultaneously with overall functionality approaching that of land- based missiles. The D5 represents an existing technology, and substantial design and development cost savings would be realized; but the associated savings would not appreciably offset the infrastructure investment requirements (road and bridge enhancements) necessary to make it a land-based weapon system. In addition, motor performance and explosive safety concerns undermine the feasibility of using the D5 as a land-based weapon system.”

The Air Force’s concerns over road and bridge quality are probably justified––missiles are incredibly heavy, and America’s bridges are falling apart at a terrifying rate. However, it is unclear why the Air Force is not confident about the D5’s motor performance, given that even aging Trident SLBMs have performed very well in recent flight tests: in 2015 the Navy conducted a successful Trident flight test using “the oldest 1st stage solid rocket motor flown to date” (over 26 years old), with 2nd and 3rd stage motors that were 22 years old. In January 2021, Vice Admiral Johnny Wolfe Jr.––the Navy’s Director for Strategic Systems Programs––remarked that “solid rocket motors, the age of those we can extend quite a while, we understand that very well.” This is largely due to the Navy’s incorporation of nondestructive testing techniques––which involve sending a probe into the bore to measure the elasticity of the propellant––to evaluate the reliability of their missiles.

As a result, the Navy is not currently contemplating the purchase of a brand-new missile to replace its current arsenal of Trident SLBMs, and instead plans to conduct a second life-extension to keep them in service until 2084. However, the Air Force’s comments suggest either a lack of confidence in this approach, or perhaps an institutional preference towards developing an entirely new missile system. [Note: Amy Woolf helpfully offered up another possible explanation, that the Air Force’s concerns could be related to the ability of the Trident SLBM’s cold launch system to perform effectively on land, given that these very different launch conditions could place additional stress on the missile system itself.]

Basing alternatives

The Draft EIS also notes that the Air Force assessed two fascinating––and somewhat familiar––alternatives for basing the new missiles: in underground tunnels and in “deep-lake silos.”

The tunnel option––which had been teased in previous programmatic documents but never explained in detail––would include “locating, designing, excavating, developing, and installing critical support infrastructure such as rail systems and [launch facilities] for an array of underground tunnels that would likely span hundreds of miles”––and it is effectively a mashup of two concepts from the late Cold War.

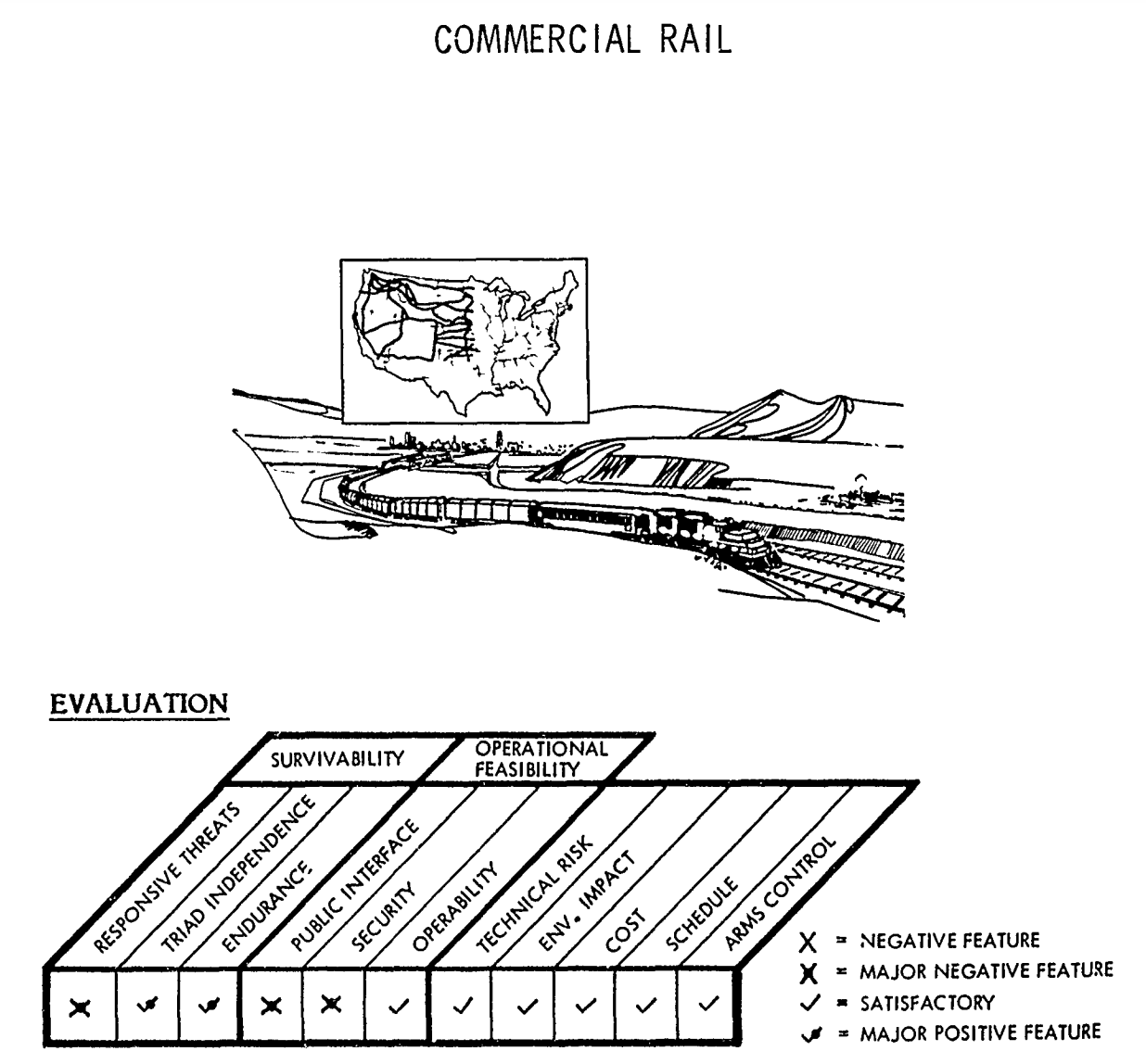

The rail concept was strongly considered during the development of the MX missile in the 1980s, although the plan called for missile trains to be dispersed onto the country’s existing civilian rail network, rather than into newly-built underground tunnels. Both the rail and tunnel concepts were referenced in one of my favourite Pentagon reports––a December 1980 Pentagon study called “ICBM Basing Options,” which considered 30 distinct and often bizarre ICBM basing options, including dirigibles, barges, seaplanes, and even hovercraft!

Illustrations of “Commercial Rail” concept from 1980 Pentagon report, “ICBM Basing Options.”

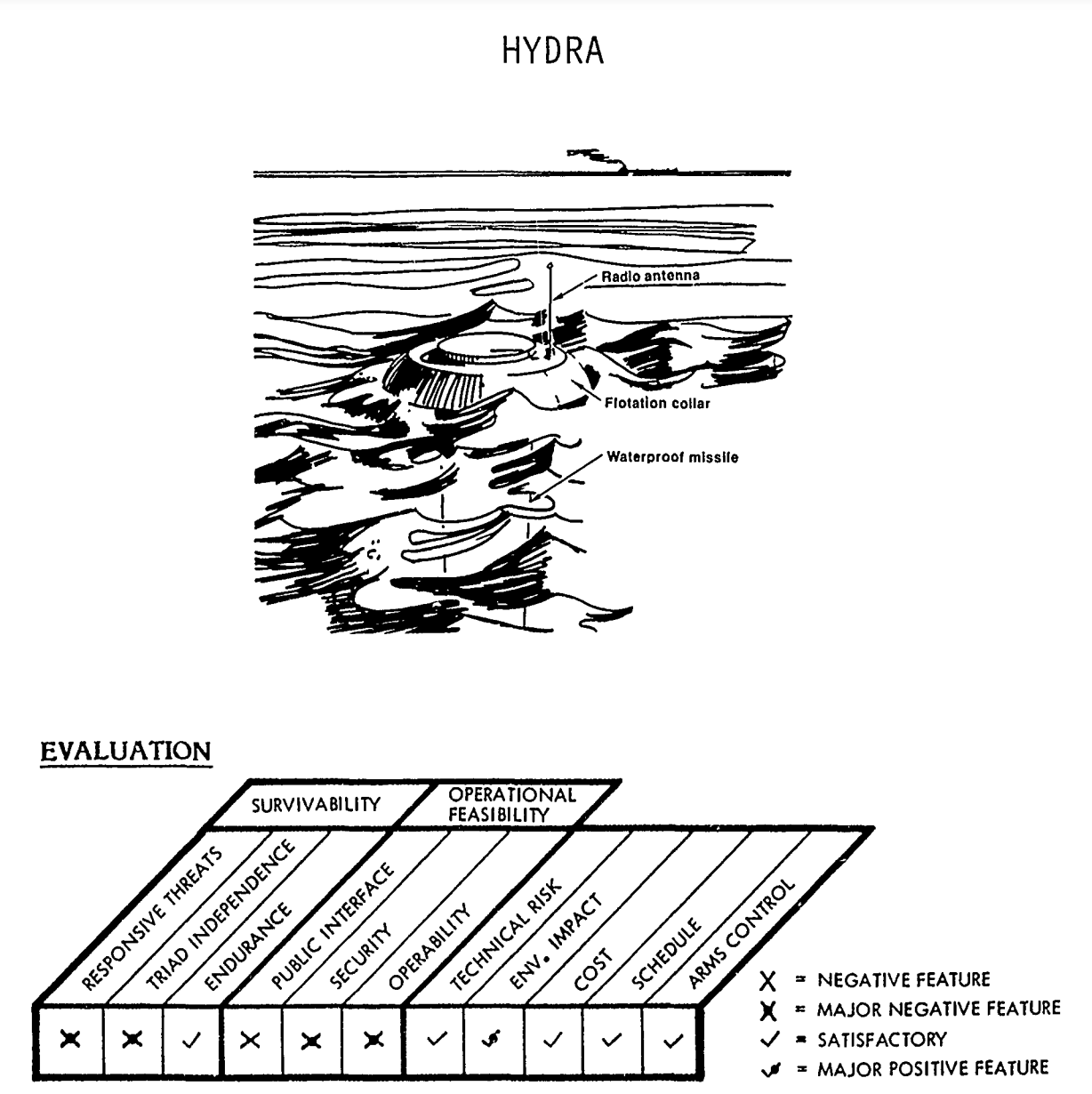

The second option––basing ICBMs in deep-lake silos––was also referenced in that same December 1980 study. The concept––nicknamed “Hydra”––proposed dispersing missiles across the ocean using floating silos, with “only an inconspicuous part of the missile front end [being] visible above the surface.” Interestingly, this raises the theoretical question of whether the Air Force would still maintain control over the ICBM mission, given that the missiles would be underwater.

Illustration of “Hydra” concept from 1980 Pentagon report, “ICBM Basing Options.”

When considering alternative basing modes for the Sentinel ICBM, the Air Force eliminated both concepts due to cost prohibitions, and, in the case of underwater basing, a lack of confidence that the missiles would be safe and secure. This concern was also floated in the 1980 study as well, with the Pentagon acknowledging the likelihood that US adversaries and non-state actors “would also be engaged in a hunt for the Hydras. Not under our direct control, any missile can be destroyed or towed away (stolen) at leisure.”

Another potential option?

In addition to revealing these fascinating details about previously considered alternatives to the Sentinel program, the Draft EIS also highlighted a public comment suggesting that “the most environmentally responsible option” would simply be the reduction of the Minuteman III inventory.

The Air Force rejected the comment because it says that it is “required by law to accelerate the development, procurement, and fielding of the ground based strategic deterrent program;’” however, the public commenter’s suggestion is certainly a reasonable one. The current force level of 400 deployed ICBMs is not––and has never been––a magic number, and it could be reduced further for a variety of reasons, including those related to security, economics, or a good faith effort to reduce deployed US nuclear forces. In particular, as George Perkovich and Pranay Vaddi wrote in a 2021 Carnegie Endowment for International Peace report, “This assumption that the ICBM force would not be eliminated or reduced before 2075 is difficult to reconcile with U.S. disarmament obligations under Article VI of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.”

The security environment of the 21st century is already very different than that of the previous century. The greatest threats to Americans’ collective safety are non-militarized, global phenomena like climate change, domestic unrest and inequality, and public health crises. And recent polling efforts by ReThink Media, the Union of Concerned Scientists, and the Federation of American Scientists suggest that Americans overwhelmingly want the government to invest in more proximate social issues, rather than on nuclear weapons. To that end, rather than considering building new missile tunnels, it would likely be much more domestically popular to spend money on domestic priorities––perhaps new subway tunnels?

—

Background Information:

- “Siloed Thinking: A Closer Look at the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent,” Federation of American Scientists (Mar. 2021)

- “Environmental Assessment Reveals New Details About the Air Force’s ICBM Replacement Plan,” Federation of American Scientists (Nov. 2020)

- ICBM Information Project, Federation of American Scientists

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and Longview Philanthropy. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The U.S. should continue its voluntary moratorium on explosive nuclear weapons tests and implement further checks on the president’s ability to call for a resumption of nuclear testing.

This missile launch provides an opportunity to further examine China’s nuclear posture and activities, including the type of missile, how it fits into China’s nuclear modernization, and where it was launched from.

Known as Steadfast Noon, the two-week long exercise involves more than 60 aircraft from 13 countries and more than 2,000 personnel.

Increasing women in leadership roles is important for gender parity and bringing in new perspectives, but it does not guarantee peace.