Much-needed supplies for responding to COVID-19 remain limited

Unlike countries such as South Korea, New Zealand, or Germany, the US has not controlled the spread of COVID-19 in a coordinated fashion, and the nation is in danger of a second surge of cases. Some experts already see indicators of the second surge. For instance, COVID-19 hospitalizations rose sharply in several states after Memorial Day, and the percentage of COVID-19 tests that are positive is rising in some parts of the country. Tragically, more than 113,000 Americans have died from COVID-19, about a quarter of all deaths reported globally. This week’s Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee hearing examined key aspects of US preparedness for a second surge of COVID-19.

Status of US availability of medical supplies

From mid March through April, when COVID-19 was first on the rise throughout the country – with cases especially surging in New York City and New Jersey – there were shortages of almost every COVID-19-related medical supply imaginable. N95 respirator masks. Face shields. Cleaning supplies. Drugs for patients on ventilators. Swabs for COVID-19 tests. States scrambled to obtain much-needed supplies, sometimes forced into bidding against one another. This was all due to the combined impacts of the sudden worldwide surge in demand for these goods, deficiencies with US caches of emergency supplies, domestic distribution issues, and a lack of timely, decisive, evidence-based leadership in the White House.

The US should have been ready for the intensified needs brought on by the pandemic, with the health security community recommending for many years that more resources be dedicated to infectious disease preparedness and response, but unfortunately, the country was caught flat-footed. The White House COVID-19 Supply Chain Task Force’s own estimates of US personal protective equipment (PPE) needs and availability – made public because Senator Maggie Hassan (D, NH) pressed the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to release them during the hearing – show US supplies of N95 respirator masks, surgical masks, gowns, and nitrile gloves not meeting demand in March, April, and May. Moving forward, the Task Force projects that beginning in July for N95 respirator masks, surgical masks, and gowns, and beginning this month for nitrile gloves, supply will meet demand for hospitals, long-term care facilities like nursing homes, first responders, and janitorial, laboratory, and correctional workers.

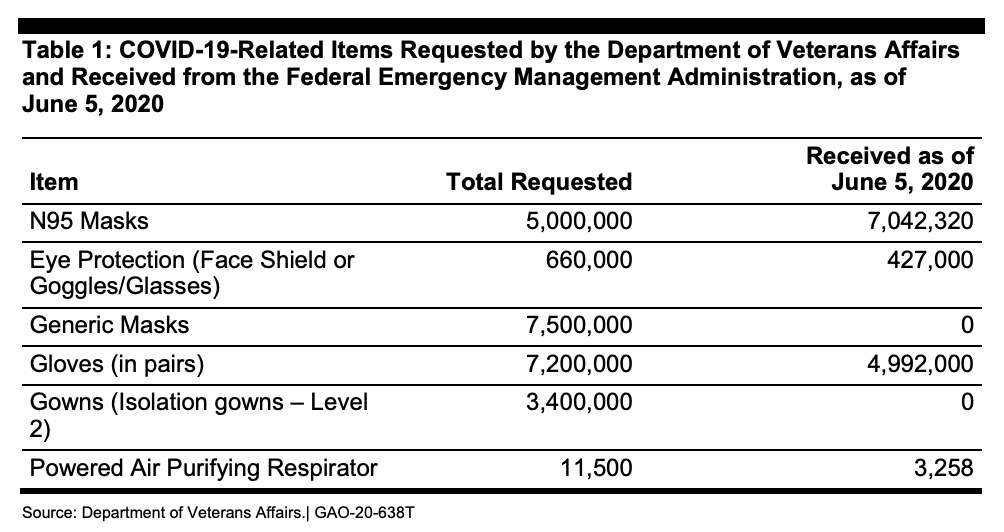

But America’s PPE supply is in flux, and there are clearly inadequacies. For example, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) says it needs a six-month supply of PPE to handle a second surge of COVID-19. At the height of the initial surge, the VA’s 170 medical centers were using 250,000 N95 respirator masks every day. Right now, the VA only has about a 30-day supply of PPE, and as of June 5th, the VA had not received any of the 7.5 million “generic masks,” nor any of the 3.4 million “isolation gowns,” it had requested from FEMA’s Strategic National Stockpile program back in mid-April.

Strategic National Stockpile

The Strategic National Stockpile was intended to be America’s fallback plan. Through April 1st (the Administration changed the wording on April 2nd), the stockpile was defined as

“…the nation’s largest supply of life-saving pharmaceuticals and medical supplies for use in a public health emergency severe enough to cause local supplies to run out. When state, local, tribal, and territorial responders request federal assistance to support their response efforts, the stockpile ensures that the right medicines and supplies get to those who need them most during an emergency. Organized for scalable response to a variety of public health threats, the repository contains enough supplies to respond to multiple large-scale emergencies simultaneously.”

The stockpile was initially launched in 1999 and managed by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2018, responsibility for the stockpile shifted to the HHS assistant secretary for preparedness and response (ASPR). In March, responsibility for the stockpile shifted again, this time to FEMA.

In the face of the coronavirus pandemic, the stockpile did not offer much resilience. Government officials estimated that the US would require 3.5 billion N95 respirator masks for a severe outbreak. There were only 12 million unexpired N95 respirator masks in the stockpile in February. In early March, the stockpile contained only 16,600 ventilators, and on April 3rd, the federal government had just 9,800 ventilators available. It is unlikely that the stockpile is being replenished since PPE that becomes available is generally immediately put to use in COVID-19 hot spots or delivered to medical centers, and it is difficult to gain insight into the current inventory of the stockpile. For instance, after not receiving a response to their Freedom of Information Act request, ProPublica filed a lawsuit against the Administration to get medical stockpile records.

A group of nine former presidential science advisors warned that the US needs to build the stockpile back up by September 1st in order to be prepared for a possible COVID-19 resurgence in the fall, and that state and local supply inventories need to be stocked as well. Their recommendations revolve around increased funding for producing essential medical goods, stockpiling supplies, and improving the coordination of the supply chain and distribution.

Moving forward through the pandemic

During the hearing, the vice director of logistics for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Rear Admiral John Polowczyk, testified that the US is ramping up domestic production of at least some critical medical supplies. Polowczyk cited the current capacity to manufacture 180 million N95 respirator masks each month, his expectation for the production of an adequate number of reusable gowns by the fall, the beginnings of at least some nitrile glove manufacturing (compared to essentially zero previous domestic capacity), and initiating the process of onshoring the making of some ventilator drugs.

Despite these signs of progress, at the moment, the US does not appear ready for another surge of coronavirus. And that surge may come sooner rather than later.

A deeper understanding of methane could help scientists better address these impacts – including potentially through methane removal.

We are encouraged that the Administration and Congress are recognizing the severity of the wildfire crisis and elevating it as a national priority. Yet the devil is in the details when it comes to making real-world progress.

The good news is that even when the mercury climbs, heat illness, injury, and death are preventable. The bad news is that over the past five months, the Trump administration has dismantled essential preventative capabilities.

The Federation of American Scientists supports H.Res. 446, which would recognize July 3rd through July 10th as “National Extreme Heat Awareness Week”.