Optimizing $4 Billion of Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program Funding To Protect the Most Vulnerable Households From Extreme Heat

The federal government needs to maximize existing funds to mitigate heat stress and ensure the equitable distribution of these resources to the most vulnerable households. Agencies could increase Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) funding allocations through incentives or by mandating a floor of benefits from these programs be distributed to a well-defined set of vulnerable households. This approach is similar to Justice40, the Biden administration’s signature environmental justice initiative that requires federal agencies to ensure a minimum allocation of 40% of program benefits are received by disadvantaged communities.

Challenge and Opportunity

In addition LIHEAP, which is administered by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Justice40 covered programs with high potential to mitigate heat stress include:

- American Climate Corps (Corporation for National & Community Service, CNCS)

- Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF; EPA)

- Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grants (EECBG; DOE)

- Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP; DOE)

- Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC; FEMA)

LIHEAP and these five priority programs have combined allocations of about $30 billion in 2024 alone. Allocating even 10% of this collective budget to the most vulnerable communities and households could significantly reduce heat mortality and morbidity.

Since its inception in 1974, LIHEAP has provided more than $100 billion in direct bill payment assistance, more than double the allocation of seven other low-income energy programs combined. LIHEAP provides a formula block grant to all states and territories and more than 150 tribes. The FY24 LIHEAP allocation is $3.6 billion; state allocations vary depending on overall and low-income population and climate.

LIHEAP is disbursed by the HHS Administration for Children and Families (ACF) to state-level HHS counterparts. These in turn distribute funding to subgrantees, including local HHS offices, national NGOs, and community-based organizations. Furthermore, there is often coordination between state and local LIHEAP administrators and utilities, which provide additional low-income energy efficiency, solar and storage programs, and rate discounts.

HHS understands the impetus for LIHEAP to reduce heat stress. For instance, in 2021, HHS published a “Heat Stress Flexibilities and Resources” memo, which outlined the disproportionate impacts of future heat conditions on communities of color and recommended using a portion of the state allocation for cooling assistance, providing or loaning air conditioners, targeting vulnerable households, and a range of public educational activities. In 2016, the agency designated a national Extreme Heat Week on how LIHEAP can be a part of the solution.

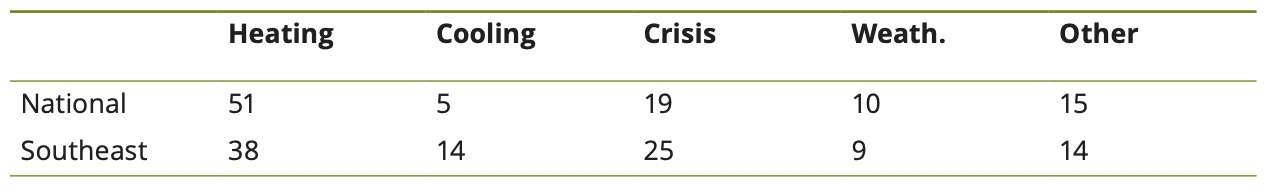

LIHEAP Formula Funding Favors Heating Assistance

However, LIHEAP funds have not been sufficiently used for cooling assistance. Nationally, from 2001 to 2019, just 5% of all LIHEAP funds were used for cooling assistance, with heating receiving ten times more funding than cooling. Even among states in the Southeast, just 14% of the budget was for cooling assistance. In 2019, only 21 states opted to provide cooling assistance, compared to the 49 that allocated funding to weatherization and 26 that used LIHEAP for energy education and supplemental energy efficiency programs.

Some states with the highest heat risk — such as Missouri, Nevada, North Carolina, and Utah — offer no cooling assistance funds from LIHEAP. Despite their warm climates, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, and Hawai’i all limit LIHEAP cooling assistance per household to less than half the available heating assistance benefit.

Prior efforts to encourage the use of LIHEAP for cooling have not resulted in a sufficient shift of this landmark funding source. LIHEAP was originally developed to provide home heating assistance at a time when winters were more severe and summers less searing. State LIHEAP administrators used the vast majority of their budgets during the heating season; many viewed cooling assistance as a luxury. This is despite the extreme heat events of recent summers, including temperatures topping 115ºF in the Pacific Northwest in 2019 and 31 days in a row of highs above 110ºF in Phoenix in 2023.

With many households still struggling to pay their winter bills, LIHEAP administrators may be reluctant to shift allocations from heating assistance that already cannot serve even 50% of eligible households. States that do not set aside dedicated cooling assistance funds frequently run out of LIHEAP, which they receive in October, well before summer. Even if crisis funds could theoretically be used to support families in crisis during heat waves, these funds are exhausted by high crisis demand in winter.

The majority of LIHEAP allocations are based on a formula rooted in a state’s low-income population, energy costs, and the severity of a state’s winter climate (its heating degree days). Residential energy costs may account for the number of cooling degree days, but they do not account for variation in electricity prices and have no consideration of population sensitivity (e.g., age) or adaptive capacity measures that are included in many Heat Vulnerability Indices (HVIs).

LIHEAP’s website on extreme heat points to the 2021 “heat dome” in the Pacific Northwest, which saw daily hospitalizations 69 times higher than the same week in 2020. In Washington state alone, 441 people died. The event, previously thought to be a 1 in 1,000-year occurrence, could occur every 5 to 10 years with just 2℃ of global warming (2023 was 1.35℃ warmer than the preindustrial average).

With advanced forecasts, LIHEAP could be deployed both to restore disconnected electric service and to make payments on extreme energy bills, which may surge even higher with the increase in demand response pricing. In Michigan, for example, DTE Energy offers a dynamic peak pricing rate that has critical peak periods at $1.03 per kWh, eight times higher than its off-peak rate. Maximum demand for electricity for continuous cooling coupled with time-of-use rate structures is a recipe for exorbitant bills that low-income customers will not be able to afford.

The risk to vulnerable households from the absence of cooling assistance is compounded by a lack of disconnection protections from extreme heat. Forty-one states offer protections for cooling, compared to just 20 that prevent utilities from disconnecting households during extreme heat. Heat protections often only kick in when a specific temperature is reached (e.g., 95°F) or even when a particular alert is issued by the National Weather Service, leaving households uncertain about their status.

In the bi-weekly Pulse Survey of the U.S. Census (June 28 to July 10, 2023, the most recent period of extreme heat nationally), 58.5% of national respondents reported keeping their home at an uncomfortable or unsafe temperature at least some months in the last year, with 18.7% reporting these indoor temperatures almost every month. Households that spend more of their income on energy bills allow indoor temperatures to rise up to 7.5°F more than higher-income households before using air-conditioning, thus dramatically increasing their risk of heat stress.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Maximize LIHEAP funding for cooling assistance

Congressional mandate – Congress could require states to use a specific percentage of their LIHEAP allocations for cooling. This percentage could be derived from FEMA’s National Risk Index (NRI), which accounts for exposure to extreme heat, the vulnerability of the population, and adaptive capacity, such as civic resources to provide emergency response. Heat Factor by First Street and Community Resilience Estimates for Heat by U.S. Census offer more granular estimates of heat vulnerability.

Incentives – LIHEAP regularly receives supplemental federal allocations (e.g. CARES Act); HHS could use these as a pool of matching funds to encourage states to leverage non-federal dollars for cooling assistance. States also have an important role to play in leveraging both public and utility funds to match and expand the impact of LIHEAP.

Emergency funds – HHS should release Emergency Contingency Funds to address extreme heat. In the 1990s and 2000s, these funds were regularly used, sometimes in excess of $700 million per year to direct cooling assistance to extreme heat events; these funds could also be used to provide cooling measures like fans, air conditioners, and insulation. These funds have been authorized but not allocated by Congress and not disbursed since 2011.

Report back to state LIHEAP administrators – Peer comparisons can be a powerful source of information and motivation. A study from the 1990s “targeting index” for the share of LIHEAP delivered to the elderly revealed stark differences between Arizona, where the elderly were underrepresented, and Texas, where they were represented above their proportion of the population. An annual dashboard of how a state compares to its close peers (e.g., to other states in its EPA region) in cooling allocations is a low-effort step that could result in significant shifts in state plans and community outreach.

Expand outreach and education to state LIHEAP administrators and subgrantees – Memos from 2016 and 2021 were insufficient to encourage many state and local budget shifts. Communications should emphasize the significantly greater risk of fatalities from extreme heat than extreme cold. One study simulated indoor temperatures in Phoenix during the 2006 heat wave and showed that by day two, temperatures in single-story homes would peak at 115ºF (46ºC). Another study projected that a five-day heat wave on the order of the record July 2023 temperatures that corresponds with a blackout would result in a fatality rate of ~1% in Phoenix, or about 1,500 deaths.

Recommendation 2. Maximize LIHEAP distribution to the most vulnerable households

While LIHEAP providers do collect significant household data through their intake forms, most states do not have firm guidelines on which households to distribute LIHEAP funds to and use a modified first-come, first-served approach. A small number of questions specific to heat risk could be added to LIHEAP applications and used to generate a household heat vulnerability score (raw or percentile). A list of 10 potential sensitivity factors to assess is included in the Frequently Asked Questions.

In partnership with extreme heat experts, US Digital Service could support the development of an algorithm to assess the likelihood of each household experiencing acute heat stress and the optimal uses of LIHEAP funding to mitigate these threats, at the household level and portfolio-wide.

Existing data from the Community Resilience Estimates for Heat (CRE) by the U.S. Census shows that more than two-thirds of extreme heat vulnerability is concentrated in just 1.5% of U.S. census tracts across 10 states. Even a small amount of LIHEAP cooling assistance, if effectively targeted, could dramatically reduce the risk of heat stroke and death.

Recommendation 3. Congressional Amendments to the LIHEAP Statute

Congress has revisited the LIHEAP formula in the past and should consider revising the formulas to elevate the role of cooling assistance and disconnection prevention during extreme heat. Rep. Watson Coleman (D-NJ) proposed this in the Stay Cool Act introduced in 2022. As the climate has changed dramatically since LIHEAP’s inception and will continue to in coming decades, Congress could peg an updated formula to an HVI as a national standard to ensure shifts in climate and population would be automatically updated in the annual LIHEAP formula. It could also update household data collection requirements under LIHEAP Statute Section 2605(c)(1)(G).

Conclusion

The number of heat-related deaths continues to rise in the U.S. In the long term, a multipronged strategy that increases funding for energy efficiency improvements, distributed generation and storage, and bill assistance is needed. But in the near term, it is critically important to work with existing resources and maximize the value of LIHEAP to mitigate the pressures of extreme heat.

Despite some positive spikes, annual LIHEAP allocations have not kept pace with accelerating demand. The number of households eligible for LIHEAP has grown four times faster than available funding; the number of eligible households served has declined from 36% to 16%. As utility bills outpace inflation, per-household LIHEAP allocations have increased without a corresponding increase in the overall allocation.

States have broad discretion on how to use LIHEAP. Overcoming the inertia of budgets dominated by heating assistance is likely to require significant advocacy, both top-down from the federal government and bottom-up from grassroots community organizations that share concerns about vulnerability to extreme heat.

This idea of merit originated from our Extreme Heat Ideas Challenge. Scientific and technical experts across disciplines worked with FAS to develop potential solutions in various realms: infrastructure and the built environment, workforce safety and development, public health, food security and resilience, emergency planning and response, and data indices. Review ideas to combat extreme heat here.

The process to develop household heat risk assessments and performance reporting could entail:

1) Design a method for assigning household scores for heat risk. Scores might consider risk of mortality, risk of heat sickness requiring medical attention/hospitalization, and risk of chronic impacts (e.g., declines in cognition and sleep quality) from consistent, low to moderate exposure to excessive heat.

Current data: LIHEAP reporting by each state’s lead agency currently includes some data that can be used to analyze prioritization of funds to mitigate extreme heat risks:

- Cooling assistance (dollars; number of households served)

- Weatherization (funded through LIHEAP)

- Assistance distributed to households with a vulnerable person (under age 5, over age 60, or a person with a disability)

- Demographic variables (e.g. race and ethnicity)

- Housing variables, namely occupancy status and for renters, whether utility bills are included in rent

- Disconnections

Proposed data collection:

- Keeping house at an unsafe temperature Medical conditions associated with heat stress (e.g., diabetes)

- Prior experience of heat stress

- Additional age distinctions (children under 2, adults over 70, over 80, over 90)

- Presence and adequacy of cooling systems Housing age and type (e.g., masonry, duplex)

- Electricity cost Solar exposure (provided by Google’s Project Sunroof)

- Urban heat island effect

- Employment

- Personal behaviors

2) Design a process so that existing program resources are distributed among the most vulnerable households, as determined by their individual heat risk scores. LIHEAP administrators might decide to spend 25% of cooling assistance funds among the most vulnerable 10% of LIHEAP applicants, for instance.

Yes, the Community Resilience Estimates for Heat (CRE) uses American Community Survey Data to determine the number of vulnerability factors a household possesses, down to census tract resolution. The tool sorts census tracts based on the number of households with zero vulnerabilities, 1–2 vulnerabilities, and 3 or more vulnerabilities. Of 73,060 census tracts, just 1,616 (2.2%) have a majority of households with more than three heat vulnerabilities. The Community Resilience Estimates (CRE) for Heat offers 10 binary risk factors.

From California to New Jersey, wildfires are taking a toll—costing the United States up to $424 billion annually and displacing tens of thousands of people. Congress needs solutions.

FAS is launching the Center for Regulatory Ingenuity (CRI) to build a new, transpartisan vision of government that works – that has the capacity to achieve ambitious goals while adeptly responding to people’s basic needs.

This runs counter to public opinion: 4 in 5 of all Americans, across party lines, want to see the government take stronger climate action.

Cities need to rapidly become compact, efficient, electrified, and nature‑rich urban ecosystems where we take better care of each other and avoid locking in more sprawl and fossil‑fuel dependence.