Don’t Fight Paper With Paper: How To Build a Great Digital Product With the Change in the Couch Cushions

Barriers abound. If there were a tagline for most peoples’ experience building tech systems in government, that would be a contender. At FAS, we constantly hear about barriers agencies face in building systems that can help speed permitting review, a challenge that’s more critical than ever as the country builds new infrastructure to move away from a carbon economy. But breaking down barriers isn’t just a challenge in the permitting arena. So today we’re bringing you an instructive and hopefully inspiring story from Andrew Petrisin, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Multimodal Freight at the U.S. Department of Transportation. We hope his success in building a new system to help manage the supply chain crisis provides the insight – and motivation – you need to overcome the barriers you face.

To understand Andrew’s journey, we need to go back to the start of the pandemic. Shelter-in-place orders around the world disrupted global supply chains. Increased demand for many goods could not be met, creating a negative feedback loop that drove up costs and propelled inflation. In June of 2021, the Biden Administration announced it would establish a Supply Chain Disruption Task Force to address near-term supply and demand misalignments. Andrew joined the team together with Port Envoy and previous Deputy Secretary of Transportation John Porcari.

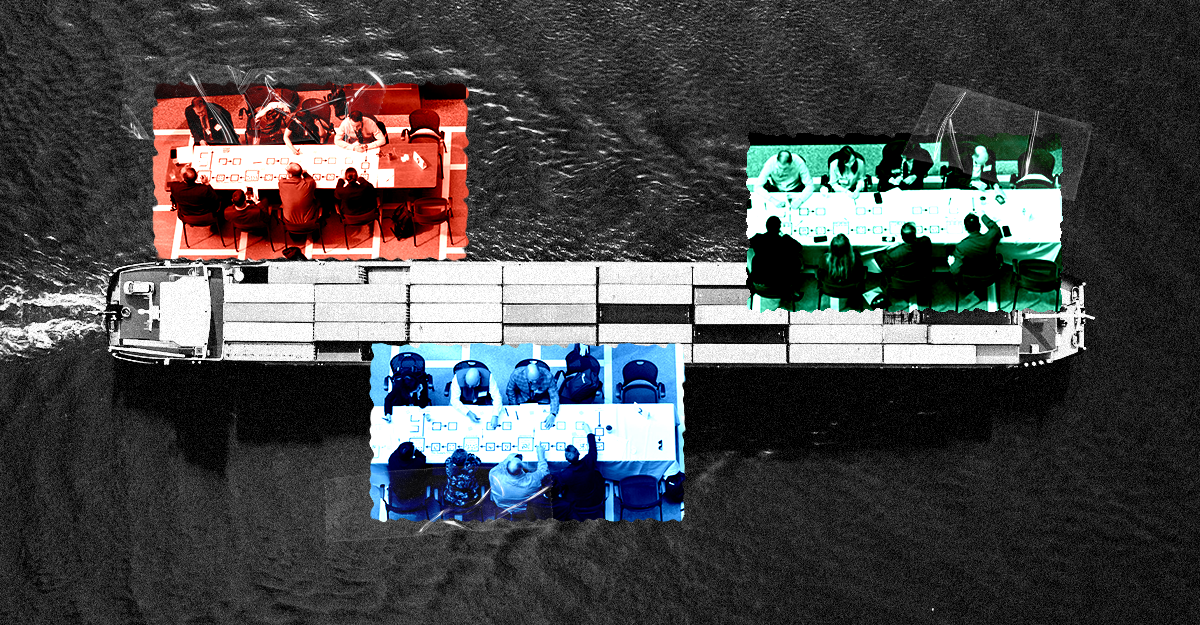

Porcari pulled together all the supply chain stakeholders out of the Port of LA on a regular basis to build situational awareness. That included the ports, terminal operators, railroads, ocean carriers, trucking associations, and labor. These types of meetings, happening three times each week during the height of the crisis, allowed stakeholders to share data and talk through challenges from different perspectives. Before the supply-chain crisis, meetings with all of the key players – in what Petrisin calls a “wildly interdependent system” – were rare. Now, railroads and the truckers had better awareness of the dwell times at the port (i.e., how long a container is sitting on terminal). Ocean carriers and ports now had greater understanding of what might be causing delays inland.

Going with the FLOW

These meetings were helpful, but to better see around corners, it needed to evolve to something more sophisticated. “The irony is that the problem was staring us right in the face,” Andrew told us, “but at the time we really had limited options to proactively fix it.” The meetings were building new relationships and strengthening existing ones, but there was a clear need for more than what had, thus far, consisted mostly of exchanges of slide decks. This prompted Petrisin to start asking some new questions: “How could we provide more value? What would make the data more actionable for each of you?” And critically, “Who would each of you trust with the data needed to make something valuable for everyone?” This was the genesis of FLOW (Freight Logistics Optimization Works).

Looking back, it might be easy to see a path from static data in slide decks shared during big conference calls to a functional data system empowering all the actors to move more quickly. But that outcome was far from certain. To start, the DOT is rarely a direct service provider. There was little precedent for the agency taking on such a role. The stakeholders Andrew was dealing with saw the Department as either a regulator or a grantmaker, both roles with inherent power dynamics. Under normal circumstances, if the Department asked a company for data, the purpose was to evaluate them to inform either a regulatory or grantmaking decision. That makes handing over data to the Department something private companies do carefully, with great caution and often trepidation. In fact, one company told Andrew “we’ve never shared data with the federal government that didn’t come back to bite us.” Yet to provide the service Andrew was envisioning, the stakeholders would need to willingly share their data on an ongoing, near real-time basis. They would need to see DOT in a whole new light, and a whole new role. DOT would need to see itself in a new light as well.

Oh, This is Different: Value to the Ecosystem

Companies had no obligation to give DOT this data, and until now, had no real reason to do so. In fact, other parts of government had asked for it before, and been turned down. But companies did share the data with Andrew’s team, at least enough of them to get started. Part of what Andrew thinks was different this time was that DOT wasn’t collecting this data primarily for its own use. “Oh, this is very different,” one of his colleagues said. “You are collecting data for other people to use.” The goal in this case was not a decision about funding or rules, but rather the creation of value back to the ecosystem of companies whose data Andrew’s system was ingesting.

To create that value, Andrew could not rely on a process that presumed to know up front what would work. Instead, he, his team, and the companies would need to learn along the way. And they would need to learn and adjust together. Instead of passive customers, Andrew’s team needed active participants who would engage in tight ‘build-measure-learn’ cycles – partners who would immediately try out new functionality and not only provide candid, quick feedback, but also share how they were using the data provided to improve their operations. “I was very clear with the companies: I need you guys to be candid. I need to know if this is working for you or not; if it’s valuable for you or not. I don’t need advice, I need active participation,” Petrisin says.

This is an important point. Too often, leaders of tech projects misunderstand the principle of listening to users as soliciting advice and opinions from a range of stakeholders and trying to find an average or mid-point from among them. What product managers should be trying to surface are needs, not opinions. Opinions get you what people think they want.“If I’d asked them what they wanted, they would have said faster horses,” Henry Ford is wrongly credited with saying. It’s the job of the digital team to uncover and prioritize needs, find ways to meet those needs, serve them back to the stakeholders, learn what works, adjust as necessary, and continue that cycle. The FLOW team did this again and again.

Building Trust through Partnership

That said, many of the features of FLOW exist because of ideas from users/companies that the team realized would create value for a larger set of stakeholders. “People sometimes ask How’d you get the shippers to give you purchase order data? The truth is, it was their idea,” Petrisin says. But this brings us back to the importance of an iterative process that doesn’t presume to know what will work up front. If the FLOW team had asked shippers to give them purchase order data in a planning stage, the answer most certainly would have been no, in part because the team hadn’t built the necessary trust yet, and in part because the shippers could not yet imagine how they would use this tool and how valuable it would be to them.

Co-creation with users relies on a foundation of trust and demonstrable value, which is built over time. It’s very hard to build that foundation through a traditional requirements-heavy up front planning process, which is assumed to be the norm in government. An iterative – and more nimble – process matters. One industry partner told Petrisin, “‘usually the government comes in and tells us how to do our jobs, but that isn’t what you did. It was a partnership.’”

One way that iterative, collaborative process manifested for the FLOW team was regular document review with the participating companies. “Each week we’d send them a written proposal on something like how we’re defining demand side data elements, for example,” Petrisin told us. “It would essentially say, ‘This is what we heard, this is what we think makes sense based on what we’re hearing from you. Do you agree?’ And people would review it and comment every week. Over time, you build that culture, you show progress, and you build trust.”

Petrisin’s team knew you can’t cultivate this kind of rapid, collaborative learning environment at scale from day one. So he started small, with a group of companies that were representative of the larger ecosystem. “So we got five shippers, two ocean carriers, three ports, two terminals, two chassis companies, three third-party logistics firms, a trucking company, and a warehouse company,” he told us, trying to keep the total number under 20. “Because when you get above 20, it becomes hard to have a real conversation.” In these early stages, quality mattered more than quantity, and the quality of the learning was directly tied to the ability to be in constant, frank communication about what was working, what wasn’t, and where value was emerging.

Byrne’s Law states that you can get 85% of the features of most software for 10% of the price. You just need to choose the right priorities. This is true not only for features, but for data, too. The FLOW team could have specified that a system like this could only succeed if it had access to all of the relevant data, and very often thorough requirements-gathering processes reinforce this thinking. But even with only 20 companies participating early on, FLOW ensured those companies were representative of the industry. This enabled real insights from very early in the process. Completeness and thoroughness, so often prized in government software practices, is often neither practical nor desired.

Small Wins Yield Large Returns

Starting small can be hard for government tech programs. It’s uncomfortable internally because it feels counter to the principle that government serves everyone equally; external stakeholders can complain if a competitor or partner is in the program and they’re not. (Such complaints can be a good problem to have; it can mean that the ecosystem sees value in what’s being built.) But too often, technology projects are built with the intent of serving everyone from day one, only to find that they meet a large, pre-defined set of requirements but don’t actually serve the needs of real users, and adoption is weak. Petrisin didn’t enjoy having to explain to companies why they couldn’t be in the initial cohort, but he stuck to his guns. The discipline paid off. “Some of my favorite calls were to go back to those companies a few months later and say, ‘We’re ready! We’re ready to expand, and we can onboard you.’” He knew he was onboarding them to a better project because his team had made the hard choices they needed to make earlier.

Starting small can ironically position products to grow fast, and when they do, strategies must change. Petrisin says his team really felt that. “I’ve gone from zero to one on a bunch of different things before this, but never really past the teens [in terms of team size], so to speak,” he says. “And now we’re approaching something like 100. So a lot of the last fiscal year for me was learning how to scale.” Learning how to scale a model of collaborative and shared governance was challenging.

Petrisin had to maintain FLOW’s commitment to serving the needs of the broader public, while also being pragmatic about who DOT could serve with given resources and continuing to build tight build-measure-learn cycles. Achieving consensus or even directional agreement during a live conversation with 20 stakeholders is one thing, but it’s much harder, and possibly counterproductive, with 60 or 100. So instead of changing the group of 20, which provided crucial feedback and served as a decision-making body, Andrew developed a second point of engagement: a bi-weekly meeting open to everyone for the FLOW team to share progress against the product roadmap weekly, which provided transparency and another opportunity to build trust through communicating feature delivery.

Fighting Trade-off Denial

One thing that didn’t change as the project scaled up was the team’s commitment to realistic and transparent prioritization. “We have to be very honest with ourselves that we can’t do everything,” Petrisin tells us. “But we can figure out what we want to do and transparently communicate that to the industry. They [the industry members] run teams. They manage P&Ls [profits and loss statements]. They understand what it is to make trade-offs with a given budget.” There was a lot of concern about not serving all potential supply chain partners, but Petrisin fought that “trade-off denial.” At that point, his team could either serve a smaller group well or serve everyone poorly. Establishing the need for prioritization early allowed for an incremental and iterative approach to development.

What drove that prioritization is not the number of features, lines of code, or fidelity to a predetermined plan, but demonstrable value to the ecosystem, and to the public. “Importers are working to better forecast congestion, which improves their ability to smooth out their kind of warehouse deliveries. Ocean carriers are working to forecast their bookings using the purchase order data. The chassis providers have correlated the flow demand data to their chassis utilization.” These are all qualitative outcomes, highly valuable but ones that could not necessarily have been predicted. There are quantitative measures too. FLOW aims to reduce operational variance, smoothing out the spikes in the supply chain because the actors can better manage changing demands. That means a healthier economy, and it means Americans are more likely to have access to the goods they need and want.

Major Successes Don’t Have to Start With Major Funding

What did the FLOW team have that put them in a position to succeed that other government software products don’t have? Given that FLOW was born out of the pandemic crisis, you might guess that it had a big budget, a big team, and a brand-name vendor. It had none of those. The initial funding was “what we could find in the couch cushions, so to speak,” says Andrew. More funding came as FLOW grew, but at that point there was already a working product to point to, and its real-world value was already established, both inside DOT and with industry. What did the procurement look like and how did they choose a vendor? They didn’t. So far, FLOW has been built entirely by developers led by DOT’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics, and the FLOW team continues to hire in-house. Having the team in-house and not having to negotiate change orders has made those build-measure-learn cycles a lot tighter.

FLOW did have great executive support, all the way up to the office of Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, who understood the critical need of better digital infrastructure for the global supply chain. It’s unfortunately not as common as it should be for leadership to be involved and back development the way DOT’s top brass showed up for Petrisin and his team. But the big difference was just the team’s approach. “The problem already existed, the data already existed, the data privacy authorities already existed, the people already existed,” he told us. “What we did was put those pieces together in a different way. We changed processes and culture, but otherwise, the tools were already there.”

FLOW into the Future

FLOW is still an early stage product. There’s a lot ahead for it, including new companies to onboard that bring more and more kinds of data, more features, and more insights that will allow for a more resilient supply chain in the US. When Andrew thinks about where FLOW is going, he thinks about his role in its sustainability. “My job is to get the people, processes, purpose, and culture in place. So I’ve spent a lot of time on making sure we have a really great team who are ready to continue to move this forward, who have the relationships with industry. It’s not just my vision. It’s our vision.” He also thinks about inevitability, or at least the perception of it. “Five years from now we should look back and think, why did we not do this before? Or why would we ever have not done it? It’s digital public infrastructure we need. This is a role government should play, and I hope in the future people think it’s crazy that anyone would have thought government can’t or shouldn’t do things like this.”

Just this spring, when the Baltimore bridge collapsed, FLOW allowed stakeholders to monitor volume changes and better understand the impact of cargo rerouting to other ports. Following the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge, Ports America Chesapeake, the container terminal operator at the Port of Baltimore, committed to joining FLOW for the benefits of supply chain resiliency to the Baltimore region. But FLOW’s success was not inevitable. Anyone who’s worked on government tech projects can rattle off a dozen ways a project like this could have failed. And outside of government, there’s a lot of skepticism, too. Petrisin remembers talking to the staff of one of the companies recently, who admitted that when they’d heard about the project, they just assumed it wouldn’t go anywhere and ignored it. He admits that’s a fair response. Another one, though, told him that he’d realized early on that the FLOW team wasn’t going to try to “press release” their way to success, but rather prove their value. The first company has since come back and told him, “Okay, now that everyone’s in it, we’re at a disadvantage to not be in it. When can we onboard?“

“You can’t fight paper with paper.” Ultimately, this sentiment sums up the approach Petrisin and his team took, and why FLOW has been such a success with such limited resources. It reminds us of the giant poster Mike Bracken, who founded the Government Digital Service in the UK, and inspired the creation of such offices as the US Digital Service, used to have on the wall behind his desk. In huge letters, it said “SHOW THE THING.” There’ll never be a shortage of demands for paperwork, for justification, for risk mitigation, for compliance in the game of building technology in government. These “government needs” (as Mike would call them) can eat up all your team has to give, leaving little room for meeting user needs. But momentum comes from tangible progress — working software that provides your stakeholders immediate value and that they can imagine getting more and more from over time. That’s what the FLOW team delivered, and continues to. They fought paper with value.

If Andrew and the FLOW team at DOT can do it, you can too. Where do you see successes like this in your work? What’s holding you back and what help do you need to overcome these barriers? Share on LinkedIn.

Lessons

Use a precipitating event to change practices. The supply chain crisis gave the team both the excuse to build this infrastructure that now seems indispensable, and the room to operate a little differently in how they built it. Now the struggle will be to sustain these different practices when the crisis is perceived to be over.

Make data function as a compass, not a grade. Government typically uses data for purposes of after-the fact evaluation, which can make internal and external actors wary of sharing it. When it can serve instead to inform one’s actions in closer to real-time, its value to all parties becomes evident. As Jennifer says in her book Recoding America, make data a compass, not a grade.

Build trust. Don’t try to “press release your way to success.” Actively listen to your users and be responsive to their concerns. Use that insight to show your users real value and progress frequently, and they’ll give you more of their time and attention.

Trust allows you to co-create with your users. Many of FLOW’s features came from the companies who use it, who offered up the relevant data to enable valuable functionality.

But understand your users’ needs, don’t solicit advice. The FLOW roadmap was shaped by understanding what was working for its stakeholders and what wasn’t, by what features were actually used and how. The behavior and actions of the user community are better signals than people’s opinions.

Start small. A traditional requirements-heavy up front planning process asks you to know everything the final product will do when you start. The FLOW team started with the most basic needs, built that, observed how the companies used it, and added from there. This enables them to learn along the way and build a product with greater value at lower cost.

Be prepared to change practices as you scale. How you handle stakeholders early on won’t work as you scale from a handful to hundreds. Adapt processes to the needs of the moment.

Fight trade-off denial. There will always be stakeholders, internal and external, who want more than the team can provide. Failing to prioritize and make clear decisions about trade-offs benefits no one in the end.

Don’t just reduce burden – provide value. There’s been a huge focus on reduction of burden on outside actors (like the companies involved in FLOW) over the past years. While it’s important to respect their time, FLOW’s success shows that companies will willingly engage deeply, offering more and more of their time, when there’s a real benefit to them. Watch your ratio of burden to value.

Measure success by use and value to users. Too many software projects define success as on-time and on-budget. Products like FLOW define success by the value they create for their users, as measured by quantitative measures of use and qualitative use cases.

Fund products not projects. FLOW started with a small internal team trying to build an early prototype, not a lengthy requirements-building stage. It was funded with “what we could find in the couch cushions” followed by modest dedicated allocations, and continues to grow modestly. This matches Jennifer’s model of product funding, as distinct from project funding.

This rule gives agencies significantly more authority over certain career policy roles. Whether that authority improves accountability or creates new risks depends almost entirely on how agencies interrupt and apply it.

Our environmental system was built for 1970s-era pollution control, but today it needs stable, integrated, multi-level governance that can make tradeoffs, share and use evidence, and deliver infrastructure while demonstrating that improved trust and participation are essential to future progress.

Durable and legitimate climate action requires a government capable of clearly weighting, explaining, and managing cost tradeoffs to the widest away of audiences, which in turn requires strong technocratic competency.

The American administrative state, since its modern creation out of the New Deal and the post-WWII order, has proven that it can do great things. But it needs some reinvention first.