One Year into the Trump Administration: DOE’s Diminished Organizational Capacity

This piece is the first in a series analyzing the current state of play at DOE, one year into the second Trump administration.

As the heart of energy innovation and infrastructure policy in the federal government, the Department of Energy (DOE) and its national labs play a crucial role in ensuring that the energy sector can meet the needs of the American people and the economy. DOE serves as a key funder of R&D for not just energy technologies, but also basic science and emerging technologies like AI and quantum computing. DOE’s 17 national labs are key supporters of that mission, conducting R&D in house and hosting facilities used by tens of thousands of researchers and innovators from the private sector and academia.

Over the course of 2025, the second Trump administration has overseen a major loss in staff at DOE; the cancellation and slow-walking of awards across the agency, primarily from Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) programs but also others; the rescission of billions of dollars from IRA programs through the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA). Most recently, Congress passed FY26 appropriations for DOE, reducing funding levels and reallocating BIL funding.

These changes will not deliver the energy and innovation impacts that this administration, or any administration, wants. The departure of seasoned career staff takes with them significant technical expertise and institutional knowledge; while the loss of new talent recruited from the private sector diminishes DOE’s industry and project finance expertise. Reducing DOE’s organizational capacity like this undermines DOE’s fundamental ability to carry out its mission and implement programs crucial to U.S. energy security, innovation and abundance.

Staff Loss

DOE has experienced deep and systematic cuts to its career staff. Early in the administration, the President issued an executive order calling for “large-scale reductions in force” (RIFs) across all executive branch agencies.1 As a part of that effort, the administration launched the Deferred Resignation Program (DRP), which was first offered on January 28th, 2025 and then again at the end of March 2025. This “fork in the road” gave career staff the option to resign or, if eligible, retire voluntarily in return for retaining their pay and benefits through September or December 2025, respectively. Expectations of upcoming RIFs incentivized many career staff to opt in to the program, rather than risk being laid off without the DRP benefits. Congressional leaders have questioned the legality of this program.

Nevertheless, the DRP was fully implemented by the Trump administration over the course of 2025, driving the majority of staff departures at DOE during the first six months of the administration. Staff data obtained by FAS indicate that 21% of DOE staff departed the agency between January 16th, right before the Trump administration began, and June 6th of 2025.2 Nineteen percent (19%) of DOE staff participated in the DRP, far outnumbering those who left the agency through other paths (e.g. layoffs, other resignations or retirements, etc.).3,4

The largest number of departing staff came from the offices under the former Under Secretary for Infrastructure (S3), which lost 52% of its staff due to the DRP and 55% of staff overall. At the most extreme end, the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED), established by BIL under the Biden administration, lost 80% of its staff due to the DRP and 84% of its staff overall. Other new offices established under the Biden administration, such as the Grid Deployment Office (GDO) and the Office of State and Community Energy Programs (SCEP), also suffered heavy losses.

In addition to the DRP, the S3 offices lost a number of staff to the Trump administration’s decision to end remote work, despite a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report finding that remote work policies improve talent attraction and retention, while reducing costs and enhancing productivity. Under the Biden administration, remote work policies enabled DOE to hire early- and mid-career staff who were unable or unwilling to move, especially those from the private sector who had valuable experience with commercial project development and finance.5 The new S3 offices established under the Biden administration benefitted the most from this, since they needed to rapidly hire qualified staff to design and implement programs for the large amounts of funding they received from BIL and IRA.

By attracting many industry leaders from the private sector, the S3 offices were able to build trust with major energy companies, leading to much higher participation from top companies in BIL and IRA programs compared to the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). Many of the staff responsible for this heightened private sector trust have now left the agency.

Offices under the former Under Secretary for Science and Innovation (S4) also suffered greater than average loss of staff: 28% due to the DRP and 29% overall. Even the Office of Fossil Energy (FE) and the Office of Nuclear Energy (NE) lost nearly a third of their staff. According to former DOE staff, some people moved from S3 to S4 in anticipation of the transition to the Trump administration.6 In particular, many of them moved to NE, which is why the number of staff in NE on January 16th actually exceeded the number of total positions the office was supposed to have.

During the October government shutdown, the Trump administration directed agencies to move forward with another round of RIFs. DOE leadership informed staff in OCED, the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE), the Office of State and Community Energy Programs (SCEP), and the Office of Minority Economic Impact that they may be fired, transferred, or reassigned due to their involvement in implementing programs under the Biden administration. The Data Foundation estimated that 187 staff were impacted by the RIF. However, the Continuing Resolution, passed on November 12th to end the shutdown, rescinded the RIF notices and guaranteed backpay to impacted federal workers.

The Impacts of Staff Loss

Staff changes and resignations at DOE will inevitably slow down implementation and threaten DOE’s ability to fulfill its mandate. DOE has struggled over the past few years to obligate funding from its budget due to its lengthy application and award negotiation process. Crucial to that process are the institutional knowledge and cohesion between technical and legal contracting teams that career staff build up over time. Every staff member lost creates a gap in the implementation process; the loss of so many staff members threatens to break down DOE’s operations entirely. Even if new staff are hired, that institutional knowledge and working dynamic can’t be recovered.

Contracting in particular is a major bottleneck for implementation. Career staff with decades of contracting experience have now left the agency and national labs. In particular, this loss will make it more difficult to implement demonstration and deployment programs like those funded by BIL and IRA, which require novel and very detailed contracting work.

Furthermore, the deep cuts to S3 call into question DOE’s ability to implement the remaining BIL and IRA funding for demonstration and deployment programs, not to mention DOE’s ability to oversee the billions of dollars worth of demonstration and deployment awards it has already made. Many of the new S3 staff were intentionally hired from the private sector for their industry knowledge and connections. These federal workers were subsequently the first to leave after the presidential transition. They took a risk in working for the federal government, and then were made to feel expendable by the new administration’s heavy-handed attempts to push people out. That experience will color any future attempts by DOE to rehire private sector talent.

The damage to implementation from staff losses will have direct impacts on peoples’ lives. For example, a 63 percent cut to SCEP staff means that whichever new office in charge of its programs post-reorganization (see next section) will not have enough capacity to run key energy affordability programs, like rebates to low-income households for cost-saving appliances or weatherization programs that keep peoples’ homes warm and reduce utility bills. Gutting of OCED and GDO will mean that major projects have a smaller chance of getting built, denying communities the new jobs and energy infrastructure they were promised.

In addition to implementation capacity, DOE is losing technical expertise that is crucial to informing its research and innovation agenda. DOE’s S4 offices have historically housed the top experts on technology areas from battery chemistry to solar panel design to advanced turbines. Many of these industry-leading experts have now left the agency, which will hamstring DOE’s ability to support private sector innovation in technologies that are critical to building an affordable and reliable energy sector and maintaining U.S. leadership globally.

The loss of crucial staff can also be expensive. For example, DOE has traditionally relied on internal counsel for the majority of its programmatic work. Now, however, roughly 50% of the field lawyers at DOE who run contracting and oversee the national labs are gone. In September 2025, DOE issued a solicitation for up to $50 million worth of external counsel in support of the agency’s day-to-day needs.

Lastly, the management of national labs (NLs) from DOE headquarters is becoming significantly harder. As seasoned program managers leave, DOE is losing the deep institutional knowledge necessary to manage the Government-Managed Laboratory Complex and to execute core functions, especially the allocation and oversight of funds that Congress intends for the labs. The flow of funds requires experienced staff who understand authorizing statutes, lab agreements, and budget execution mechanics; losing them creates the risk of both bottlenecks and misalignment.

Reorganization

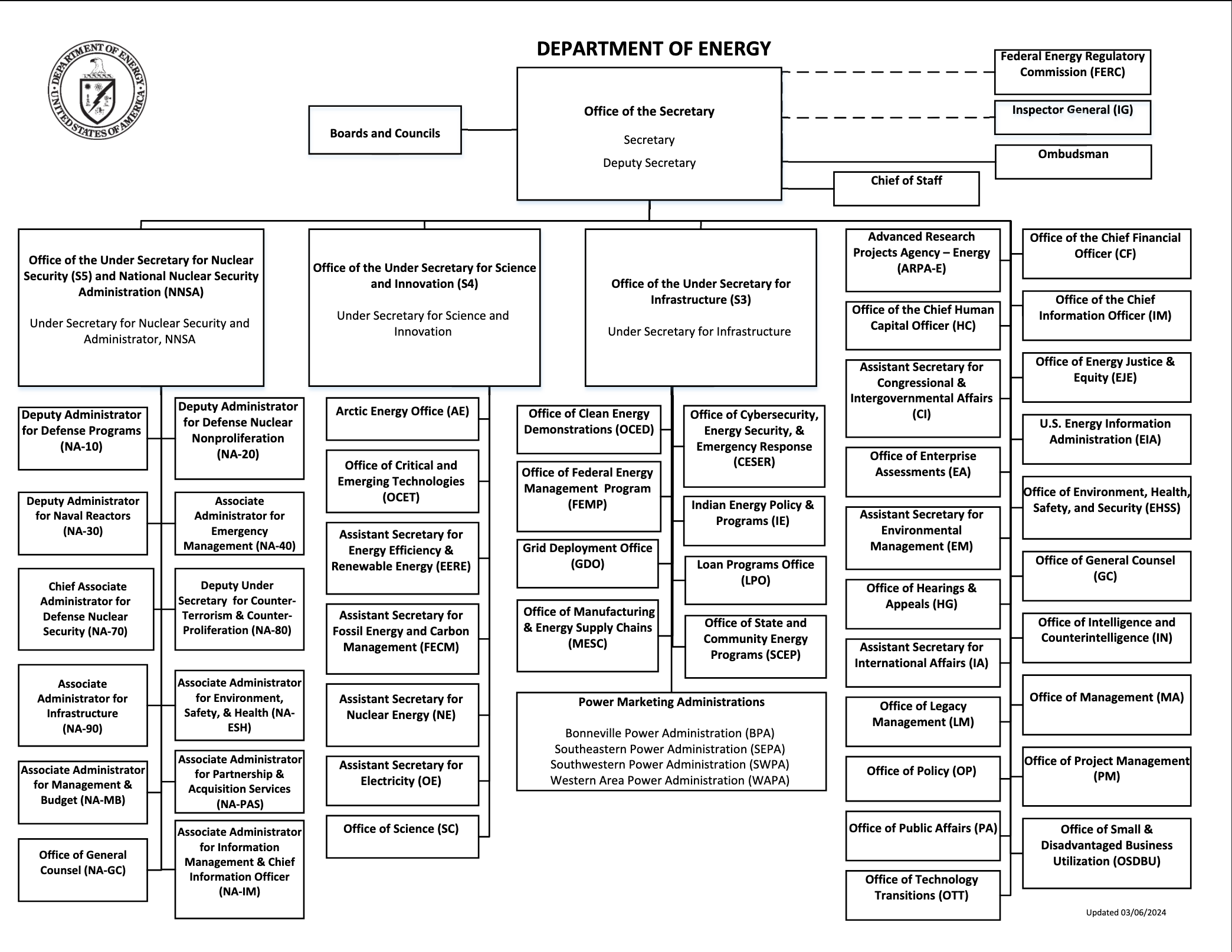

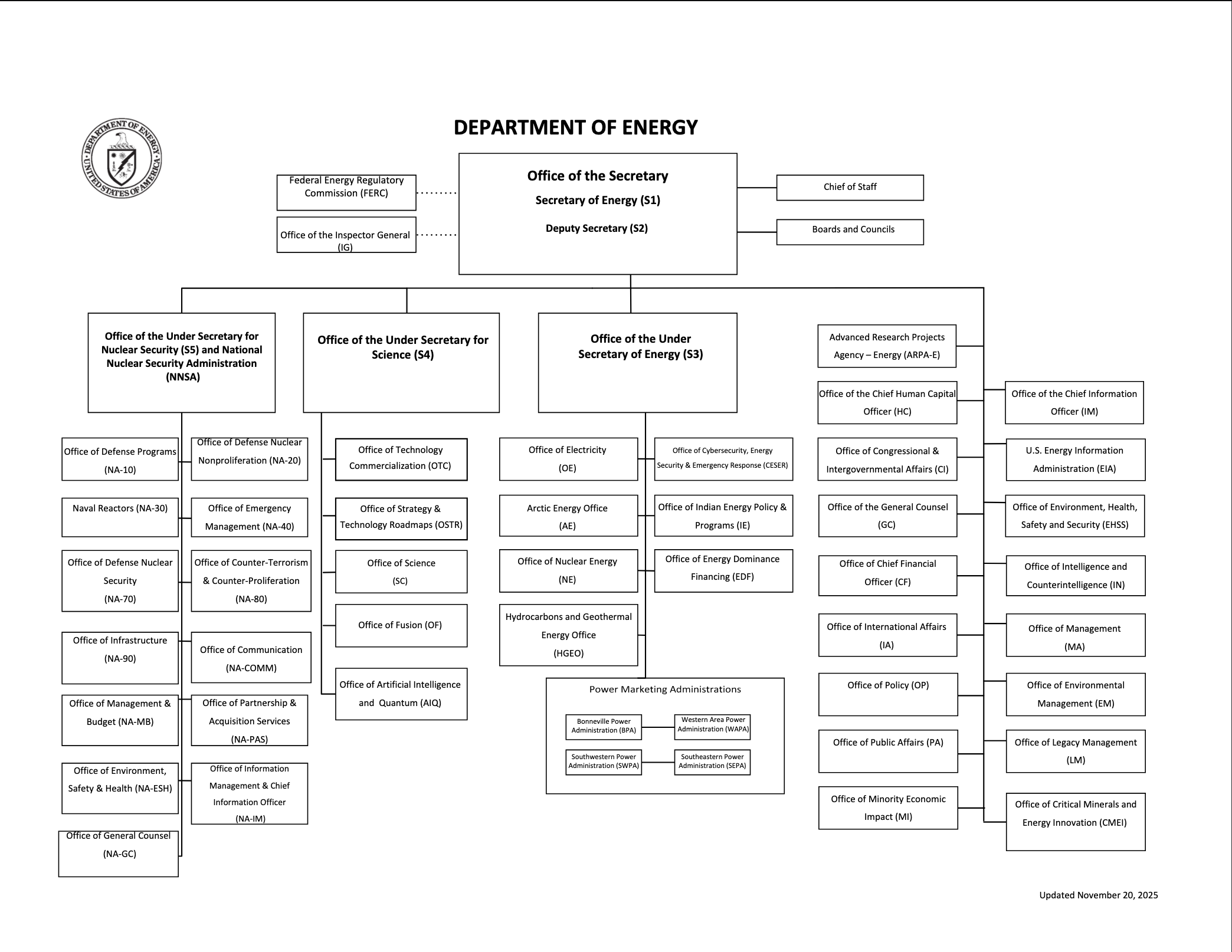

In November 2025, DOE leaders announced a sweeping reorganization that eliminated, consolidated, and rebranded major program offices while creating several new ones, formalizing a significant shift in the Department’s priorities (see Figures 1 and 2).7 Several of DOE’s most recognizable clean energy innovation and deployment offices — including EERE, OCED, SCEP, the Grid Deployment Office (GDO), and the Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains (MESC) — were dissolved as standalone entities. Their programs were redistributed across a new set of divisions organized around broad technology themes rather than the previous approach of differentiating between developmental stages (i.e. R&D vs. demonstration and deployment).

Figure 1. DOE organization chart prior to November 20th, 2025 (Source: DOE).

Figure 2. DOE’s new organizational structure after November 20th, 2025 (Source: DOE)

As part of this shift, DOE created or elevated new offices focused on emerging priorities. A new Office of Critical Minerals and Energy Innovation now centralizes critical minerals programs, which were previously spread across EERE, FE, and MESC, while also seeming to be a catch-all office for remaining EERE, OCED, MESC, and SCEP programs. A Hydrocarbons and Geothermal Office merges FE with the Geothermal Technologies Office. The reorganization also expanded the department’s work on emerging technologies by splintering off programs that used to be contained within the Office of Science: pairing AI and quantum programs into a new office and creating a dedicated fusion office with a more prominent role than before.

These changes significantly alter DOE’s internal map. Programs that once lived together are now split apart, while other functions have been consolidated under new leadership structures. The result is a department whose mission areas are organized very differently than they were even a few months ago, leaving open questions about how core clean energy, deployment, and innovation functions will be staffed and managed going forward.

Though previous administrations, including the Biden administration, have conducted reorganizations of DOE in the past, this reorganization was implemented with significantly less transparency. As of late December, the brief initial announcement and new organization chart are the only information the public has received on the reorganization. DOE’s website is currently inaccessible. Career staff have reported that they still lack clarity as to how their chains-of-command will be affected and whether or not the programs they work on will continue or change.

These structural changes are unfolding at the same time DOE is experiencing substantial workforce losses, which heightens uncertainty about staff capacity. It remains unclear how remaining staff are being reassigned within the new organizational chart. With offices being renamed or re-scoped — and in many cases merged, split, or relocated — advocacy and stakeholder communities cannot easily determine whether DOE retains the necessary expertise or institutional knowledge to carry out ongoing work.

Basic information like program areas and suboffices within each office, program leadership, and staffing data is now outdated, making it difficult to track where core functions have moved. Managing this transition is essential for retaining remaining staff and preventing further loss of expertise. DOE leaders must clearly communicate roles, reporting lines, and program continuity to restore internal morale and ensure the agency can continue driving energy innovation and promoting energy abundance amid an unprecedented U.S. energy affordability crisis.

This uncertainty underscores the need for greater transparency from DOE. Providing updated information on each new office’s missions and internal structure, staffing data, and explanations of how programs map onto the new structure would help rebuild trust and give stakeholders a clearer understanding of the agency’s operational capacity. Without this information, questions about DOE’s ability to execute its mission will persist at precisely the time when federal leadership on clean energy, innovation, and energy affordability is most needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Megan Husted and Arjun Krishnaswami for their pivotal roles in shaping the vision for this project, planning and executing the convenings that informed this report, and providing insightful feedback throughout the entire process. The authors would also like to thank Kelly Fleming for her leadership of the project team while she was at FAS. Additional gratitude goes to Colin Cunliff, Keith Boyea, Kyle Winslow, and all the other individuals and organizations who helped inform this report through participating in workshops and interviews and reviewing an earlier draft.

Appendix: DOE Staff Data

How DOE can emerge from political upheaval achieve the real-world change needed to address the interlocking crises of energy affordability, U.S. competitiveness, and climate change.

As Congress begins the FY27 appropriations process this month, congress members should turn their eyes towards rebuilding DOE’s programs and strengthening U.S. energy innovation and reindustrialization.

Politically motivated award cancellations and the delayed distribution of obligated funds have broken the hard-earned trust of the private sector, state and local governments, and community organizations.

Over the course of 2025, the second Trump administration has overseen a major loss in staff at DOE, but these changes will not deliver the energy and innovation impacts that this administration, or any administration, wants.