Delays, Deferment, and Continuous At-Sea Deterrence: The United Kingdom’s Increasing Nuclear Stockpile and the Infrastructure That Makes it Happen

Between 2006 and 2015, the United Kingdom repeatedly and publicly announced its intentions to decrease the size of its nuclear weapons stockpile, most recently committing to at most 180 weapons by the mid-2020s. As the years went by, non-government policy experts and nuke watchers assumed that the UK Government was making good on its word and that the UK nuclear arsenal would continue to gradually reduce. In reality, the United Kingdom is thought to have maintained a nuclear stockpile of approximately 225 weapons, and, in a surprise move in 2021, the United Kingdom declared that it would extend the ceiling of its “overall nuclear weapon stockpile” to no more than 260 weapons. This constituted an abrupt about-face from its previous commitments and trajectory.

However, the infrastructure underpinning the sustainability of the United Kingdom’s nuclear weapons and their modernization has experienced significant budgetary and scheduling challenges. Furthermore, the UK has dramatically reduced the public transparency of its nuclear forces, making it increasingly difficult to understand and debate the true scope of these challenges.

The UK’s Nuclear Warhead Modernization

Announced in 2005, the Atomic Weapons Establishment’s (AWE) Nuclear Warhead Capability Sustainment Programme (NWCSP) was an initiative to deliver infrastructure and technology to sustain the United Kingdom’s current stockpile and underpin its warhead replacement program. Each of these main infrastructure and technology projects is named after a constellation: Project Orion for a high-power research laser that began operations in 2013, Project Leo for a small parts manufacturing facility, Project Pegasus for the manufacturing of uranium components effort, and so on. Several of these projects under the NWCSP related to techniques used for nuclear weapons development in place of explosive testing. Part of the NWCSP mission also involved refurbishing the United Kingdom’s current warheads for integration with the U.S.-supplied, upgraded Mk4A aeroshell, which was completed in 2023. The NWCSP was scheduled to run from April 2008 until April 2025 and was removed from the MOD Government Major Projects Portfolio data starting in 2022, indicating it could have been downsized from a large-scale development initiative.

In February 2020, the UK defence secretary announced a new warhead program—the A21/Mk7/ Astraea. This new warhead is currently in the concept stage but is planned to eventually replace the Mk4A/Holbrook beginning in the late 2030s. As was the case with the previous version, the A21/Mk7 Astraea design and production will have a “very close connection” to the future US W93/Mk7.

In 2023, the MOD confirmed that £127 million had been spent on the A21 Astraea warhead replacement program as of March 2022. The total cost of the replacement program has not been released, given it is still in the early stages. However, even if cumulative costs are released, individual costs associated with the warhead modernization program will be challenging to identify due to changes in UK budgetary reporting practices. In 2023, nuclear-related programs and expenditures—including the AWE and the NWCSP—were compiled into one heading under Defence Nuclear Enterprise (DNE), which appears as a single line item in the departmental estimates. This makes it impossible to see the direct in-service costs associated with the individual programs. DNE funding was also “ringfenced” within the MOD budget to protect it against spending cuts.

The UK’s declaration that its stockpile ceiling will be raised to 260 raises several questions. In the early- to mid-2000s, the United Kingdom possessed a stockpile of roughly 280 warheads, but in 2010 announced it would reduce this level to “no more than 225 warheads.” To be able to increase this level to up to 260 warheads, as announced by the UK government in 2021, it seems some of the retired warheads—or components from them—must have been retained in some form. The United Kingdom appears to use the term “stockpile” to describe operational, deployed, and retired weapons. The timeline for potentially increasing the stockpile to up to 260 is not known, but if it is a relatively short timeline, it would seem to require reconstituting some retired warheads. If it is a longer timeline, it could potentially involve increasing the number of A21 Astraea warheads in the future. Of the “no more than 225” warhead stockpile level, the United Kingdom has previously explained that 120 warheads would be operationally available, of which 40 would be deployed on the single ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) on patrol at all times. The reason for increasing the stockpile to up to 260 warheads appears to be derived from an interest in increasing the number of “operationally available” warheads to be able to deploy a full warhead load on the SSBN fleet—something the recent warhead level did not allow.

Critical Infrastructure

Any warhead design, manufacturing, and testing occurs at the AWE site at Aldermaston while the warheads are assembled, maintained, and decommissioned at AWE Burghfield. These two sites are critical to maintaining the United Kingdom’s existing stockpile and will play a significant role in the new warhead replacement program.

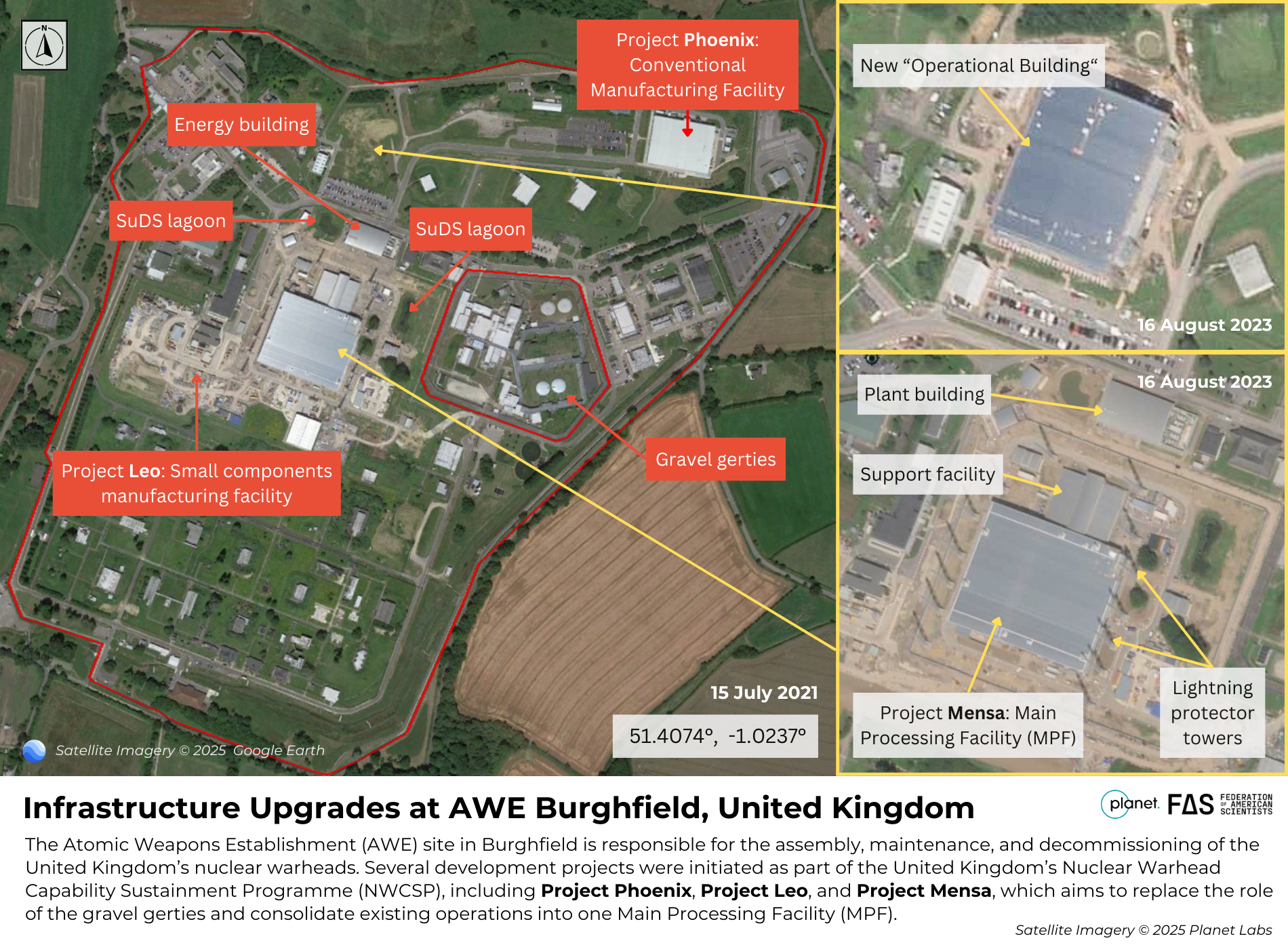

Upgrades at AWE Burghfield

Project MENSA—one of the infrastructure programs under the NWCSP—aims to consolidate existing nuclear warhead assembly and disassembly operations into a single building located in the center of the AWE Burghfield complex called the Main Processing Facility (MPF). MENSA will replace the existing Gravel Gertie bunkers used for warhead assembly and disassembly on the eastern part of the campus, which are designed to collapse inward in the event of an explosion. Other new infrastructure for this project includes a support building and 16 lightning protector towers to accompany the MPF, as well as an associated plant building, gatehouses, vehicle inspection bays, substation buildings, security fences, access roads, and Sustainable Drainage System (SuDS) infrastructure.

Project MENSA’s completion has been delayed by more than seven years, and its expected cost is £1.36 billion over its original total budget of £0.8 billion. Construction progress at the site can be observed through satellite imagery and should be nearing completion of construction according to the MoD’s 2024 Major Project Portfolio data.

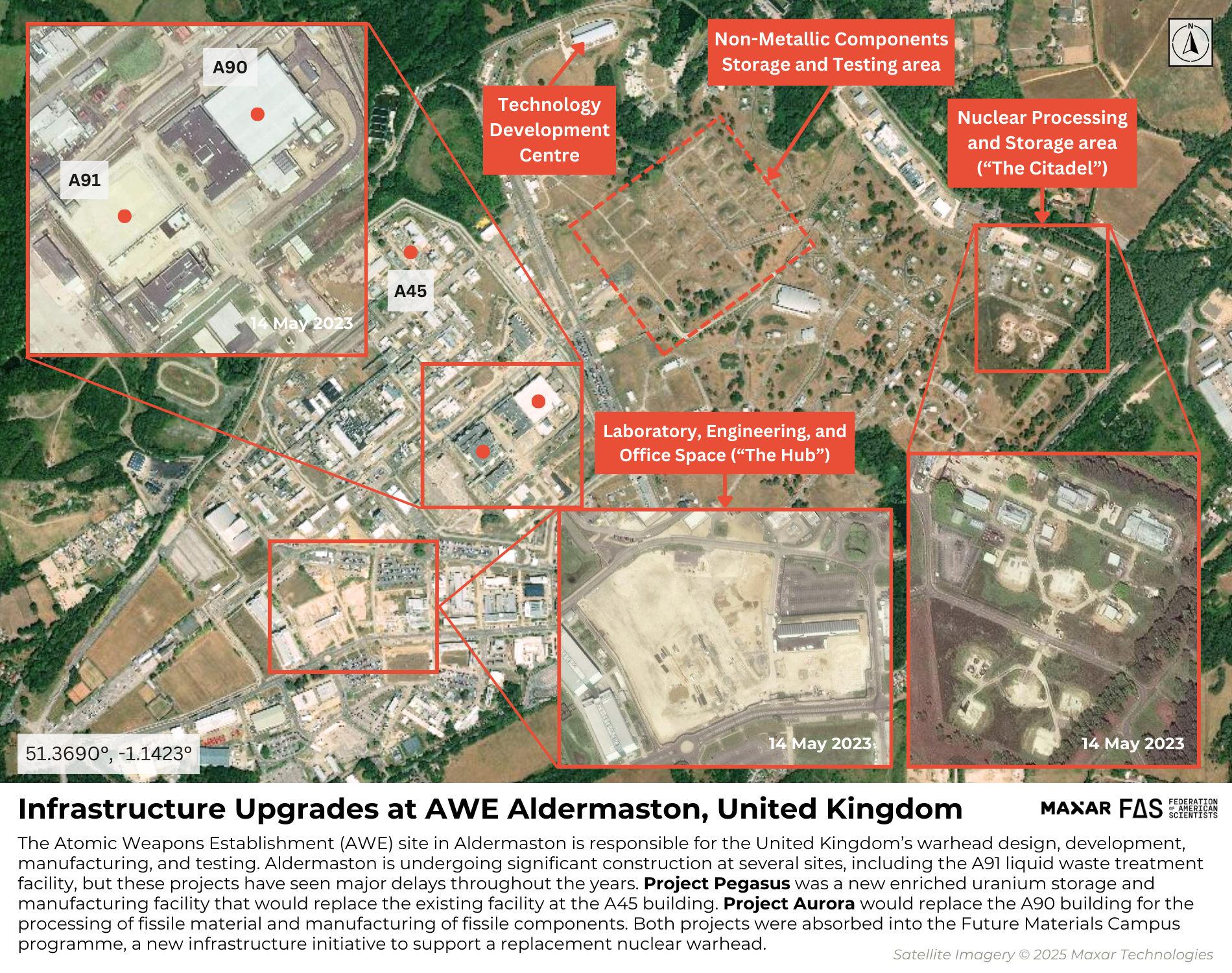

Upgrades at AWE Aldermaston

AWE Aldermaston, where warhead design, development, manufacturing, assembly, and testing occur, is also undergoing significant upgrades and revitalization. In 2024, AWE announced two new infrastructure programs—the Future Infrastructure Programme (FIP) for general infrastructure and the Future Materials Campus (FMC) for nuclear material manufacturing and storage—to consolidate existing programs and invest in new ones to increase capacity for maintaining, manufacturing, and storing nuclear weapons. The procurement process for these multi-year, multi-billion pound projects began on April 22 and December 12, 2024, respectively. The FMC, in particular, will be a collection of facilities, including nuclear science and technology centers and laboratories, to be built at AWE Aldermaston. This program will replace two major projects that initially fell under the NWCSP—Project Pegasus and Project Aurora.

Project Pegasus was described as a new enriched uranium storage and manufacturing facility at AWE Aldermaston that would replace the existing enriched uranium handling facility located at the A45 building. Work began in 2003, and the original projected service date was 2016. The approved cost was originally £634 million before it skyrocketed to £1.7 billion. After a six-year delay and a three-year pause, construction of the new storage facility began, and the manufacturing facility was scheduled to be finished by 2030. The severe delays were mainly due to challenges with the supply chain environment and an “overly complex technical solution” that resulted in additional construction and safety costs and a “reassessment” of the project design and requirements.

The UK government was also in the early design phase of Project Aurora, an infrastructure project for a new plutonium manufacturing facility that would replace the current A90 building at AWE Aldermaston. This program was experiencing delays due to resourcing problems, supply chain shortages, and high-skilled workforce challenges. Project Aurora was removed from the NWCSP and added as an independent program to the MOD’s Major Projects Portfolio in 2022. Projects Aurora and Pegasus were both removed from the 2024 version of the MOD’s Major Projects Portfolio database, likely due to their absorption into the new FMC program.

The other central element of NWCSP is the delivery of a new hydrodynamics facility. In 2010, the United Kingdom and France signed the Teutates Treaty, which allowed for cooperation on warhead physics research between the two nations. From this agreement, the EPURE radiographic facility was built at Valduc in France, and a joint UK-France Technology Development Centre was established at Aldermaston. These facilities will support hydrodynamic research that will allow the study of the effects of aging and manufacturing processes on nuclear warheads without nuclear explosive testing. Because of the Teutates program, the UK’s original plans for a ‘Project Hydrus’ hydrodynamics facility were canceled.

Outstanding Challenges

The facilities described above are deemed crucial to the United Kingdom’s effort to modernize and refurbish its nuclear deterrent. However, the significant delays and cost overruns have elicited criticism from the public and concern from government authorities over the years. In August 2024, the House of Commons reported a spending deficit on nuclear programs across the Defence Equipment Plan. Over the next ten years (2023 to 2033), costs are forecasted at £117.8 billion, of which only £109.8 billion had been budgeted for when the report was released.

Alongside these warhead development and infrastructure programs, the United Kingdom is also replacing its four SSBNs with the new Dreadnaught class, the first of which is expected to enter service in the early 2030s. This modernization has also been plagued by cost increases and threatens to be delayed, given maintenance issues with the existing fleet.

Moreover, the recent decrease in UK government transparency regarding the status of its nuclear arsenal and modernization program reflects a worrisome global trend. The United Kingdom has not publicly declared the approximate size of its stockpile since 2010, following the Obama Administration’s decision to release its stockpile number. In 2021, the MOD referred to the 2010 announcement again but did not explicitly say what the stockpile number was. Moreover, it said it would “no longer give public figures for our operational stockpile, deployed warhead or deployed missile numbers.”

Additionally, the MOD said in 2023 that it was withholding information on planned in-service dates for many of the above-referenced projects for “reasons of national security” and did not release this information in its 2022, 2023, and 2024 Major Projects Portfolio data. Finally, the MOD has published an annual update to Parliament since 2011 on the progress of nuclear weapons upgrades, but there has been no report published for 2023 or 2024.

While some of this backsliding is likely rooted in concerns about public perception of persistent programmatic delays, the overall picture raises concerns about a pattern of declining transparency and reduced public ability to monitor and hold the UK government accountable for its nuclear weapons program.

Even without weapons present, the addition of a large nuclear air base in northern Europe is a significant new development that would have been inconceivable just a decade-and-a-half ago.

Known as Steadfast Noon, the two-week long exercise involves more than 60 aircraft from 13 countries and more than 2,000 personnel.

The United Kingdom is modernizing its stockpile of nuclear weapons and delivery systems, as detailed today in the Federation of American Scientists latest edition of its Nuclear Notebook, “United Kingdom Nuclear Forces, 2024”.