ARPA-I: Share an Idea

Do you have ideas that could inform an ambitious Advanced Research Projects Agency-Infrastructure (ARPA-I) portfolio at the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT)? We’re looking for your boldest infrastructure moonshots.

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is seeking to engage experts across the transportation policy space who can leverage their expertise to help FAS identify a set of grand solutions around transportation infrastructure challenges and advanced research priorities for DOT to consider. Priority topic areas include but are not limited to metropolitan safety, rural safety, resilient and climate-prepared infrastructure, digital infrastructure, expediting “mega projects,” and logistics. You can read more about these topic areas in depth here.

What We’re Looking For and How to Submit

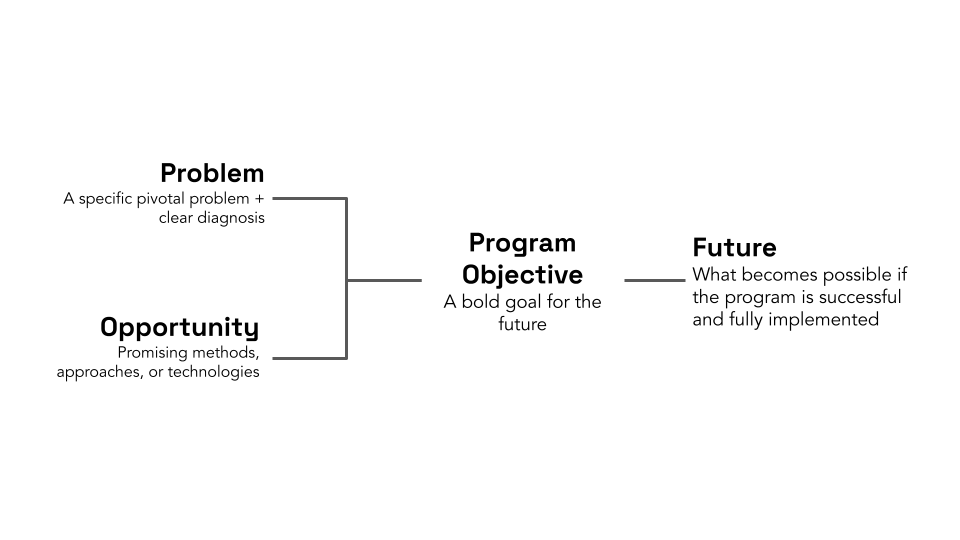

We are looking for experts to develop and submit an initial program design in the form of a wireframe that could inform a future advanced research portfolio at DOT. A wireframe is an outline of a potential program that captures key components that need to be considered in order to assess the program’s fit and potential impact. The template below reflects the components of a program wireframe. Wireframes can be submitted by email here. Please include all four sections of the wireframe shown in the template below in the body of your email submission.

When writing your wireframe, we ask you aim to avoid the following common challenges to ensure that ideas are properly scoped, appropriately ambitious, and are in line with the agency’s goals:

- No clear diagnosis of the problem: Many challenges facing our transportation infrastructure are not defined by a single problem; rather, they are an ecosystem of issues that simultaneously need addressing. An effective program will not only isolate a single “problem” to tackle, but it will approach it at a level where something can actually be done to solve it through root cause analysis.

- Thinking small and narrow: On the other hand, problems being considered for advanced research programs can be isolated down to the point that solving them will not drive transformational change. In this situation, narrow problems would not cater to a series of progressive and complimentary projects that would fit an ARPA.

- Incorrect framing of opportunities: When doing early-stage program design, opportunities are sometimes framed as “an opportunity to tackle a problem.” Rather, an opportunity should reflect a promising method, technology, or approach that is already in existence but would benefit from funding and resources through an advanced research agency program.

- Approaching solutions solely from a regulatory or policy angle: While regulations and policy changes are a necessary and important component of tackling challenges in transportation infrastructure, approaching issues through this lens is not the mandate of an ARPA. ARPAs focus on supporting breakthrough innovations across methods, technologies, and approaches. Additionally, regulatory approaches to problem solving can often be subject to lengthy policy processes.

- No explicit ARPA role: An ARPA should pursue opportunities to solve problems where, without its intervention, breakthroughs may not happen within a reasonable timeframe. If solving a problem already has significant interest from the private or public sector, and they are well on their way to developing a transformational solution in a few years time, then ARPA funding and support might provide a higher value-add elsewhere.

- Lack of throughline: The problems identified for ARPA program consideration should be present as themes throughout the opportunities chosen to solve them as well as how programs are ultimately structured–otherwise, a program may lack a targeted approach to solving a particular challenge.

- Forgetting about end-users: Human-centered design should be at the heart of how ARPA programs are scoped, especially when thinking about the scale at which designers need to think about how solving a problem will provide transformational change for everyday users of transportation infrastructure.

- Being solutions-oriented: Research programs should not be built with pre-determined solutions already in mind; they should be oriented around a specific problem in order to ensure that any solutions put forward are targeted and effective.

For a more detailed primer on ARPA program ideation, please read our publication, “Applying ARPA-I: A Proven Model for Transportation.”

Sample Idea

Informed by input from non-federal subject matter experts

Problem

Urban and suburban environments are complex, with competing uses for public space across modes and functions – drivers, transit users, cyclists, pedestrians, diners, etc. Humans are prone to erratic, unpredictable, and distracted driving behavior, and when coupled with speed, vehicle size, and infrastructure design, such behaviors can cause injury, death, property damage, and transportation system disruption. A decade-old study from NHTSA – at a time when roadway fatalities were approximately 25% lower than current levels – found that the total value of societal harm from crashes in 2010 was $836 billion.

Opportunity

What if the relationships between the driver, the environment (including pedestrians), and the vehicle could be personalized?

- Driver-to-Vehicle: Using novel data gathered from cars’ sensors, driver smartphones, and other collectible data, design a feedback loop that customizes Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) to unique driving behavior signatures.

- Vehicle-to-Environment: Using V2I/V2X and geofencing technologies to govern and harmonize speed and lane operations that optimize max speeds for safety in unique street contexts.

- Driver-to-Environment: Blending both D2V and V2E technologies, develop integrated awareness of the surrounding environment that alerts drivers of potential risks in parked (e.g., car door opening to a bike lane) and moving states (e.g., approaching car).

Program Objective

- Driver-to-Vehicle: (1) Identify the totality of usable driver data within the vehicular environment, from car sensors to phone usage; (2) develop a series of driver profiles that will build the foundation for human-centered, personalized ADAS that can both intervene in an emergency and nudge behavior change through informational updates, intuitive behavioral feedback, or modifying vehicle operations (e.g., acceleration); (3) develop dynamic, intelligent ADAS systems that customize to driver signatures based on preset profiles and experiential, local training of the algorithm; (4) establish this as a proof of concept for a novel, personalized ADAS and architect a grand-challenge for industry to improve upon this personalized, human-centered ADAS with key target metrics; (5) create a regulatory framework mandating Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) to include a baseline level of ADAS, given the results of the grand challenge.

- Vehicle-to-Environment: (1) Design the universal mobile application or geofence trigger that will contour virtual boundaries for a set of diverse, transferrable streets (e.g., school zones) and characteristics (e.g., bike lanes); (2) engage OEMs to design and integrate the geofence triggers with the human-centered ADAS and/or another vehicle-based receiver within a test fleet of different car types to modify vehicle responses to the geofence criteria as outlined by the pilot cities; (3) broker partnerships with 10 cities to identify a menu of geofence criteria, pilot the use of them, and establish a mechanism to measure before-and-after outcomes and comparisons from neighboring regions;

- Driver-to-Environment: integrate ADAS with the geofence trigger to develop an advanced and dynamic situational awareness environment for drivers that is customized to their profile and based on built environment conditions such as bike lanes and school zones, as well as weather, high traffic, and time of day.

Future

Digital transportation networks can communicate personalized information with drivers through their cars in a uniform medium and with a goal of augmenting safety in each of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas.

To secure the U.S. bio-infrastructure, maintain global leadership in biotechnology, and safeguard American citizens from emerging threats to their privacy, the federal government must modernize its approach to human genetic and biological data.

From use to testing to deployment, the scaffolding for responsible integration of AI into high-risk use cases is just not there.

The Federation of American Scientists supports Congress’ ongoing bipartisan efforts to strengthen U.S. leadership with respect to outer space activities.

By preparing credible, bipartisan options now, before the bill becomes law, we can give the Administration a plan that is ready to implement rather than another study that gathers dust.