A Reflection on the 2023 Hiroshima ICAN Academy

The views expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Government.

As I stood outside of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, now memorialized as the Atomic Bomb Dome, I was amazed by the profound stillness of the park even though it sat in the shadow of the city’s tall buildings beside busy streets filled with cars and pedestrians.

I glanced at an image on my phone of the area taken several days after the bomb dropped. The Atomic Bomb Dome stood defiantly amidst the wasteland of flattened buildings and burnt rubble. Now, it stood beside large green trees and towering apartment buildings in the gaze of a large athletic stadium. I had learned that the river beside me, now full of boats bringing tourists to the nearby Miyajima Island, was once filled with bodies of people who sought a brief relief for their burning flesh. I tried to imagine how this peaceful and modernized city looked in 1945, but visualizing such horror was beyond my imagination.

Without intentionally traveling to the Peace Park in Hiroshima, one could almost entirely overlook the city’s tragic history. Amidst the modern stores, apartment buildings, and restaurants, several buildings that survived the atomic bomb blast have been preserved, bearing the heavy weight of Hiroshima’s legacy. They remember the flattened buildings, waves of fire, black rain, and harrowing human cries for water.

The New Voices on Nuclear Weapons Fellowship at the Federation of American Scientists helped me enter the field with no prior knowledge of nuclear weapons, let alone deterrence theory and the history of nuclear proliferation. I can confidently say that without this fellowship opportunity, I would not have thought I could have the authority to speak about nuclear weapons.

Many conversations and debates about nuclear weapons are rooted in complicated theories and hypothetical scenarios, making it difficult to join the discussion. While I believe it’s challenging for any human brain to fully internalize nuclear weapons’ lethal capacity, we can comprehend how nuclear weapons surpass the threats posed by other forms of warfare in terms of their destructive and indiscriminate potential.

I applied to the 2023 Hiroshima-ICAN Academy on Nuclear Weapons and Global Security to conceptualize the true destructive power of a nuclear weapon. Prior to the academy, I believed indisputable international norms prevented government officials from accepting disarmament and abolition as plausible nuclear policy guidelines. In speaking with hibakusha and many young activists in Japan, my preconceived notion was challenged; I learned that the propensity to dismiss the feasibility of nuclear abolition is not innate. Those who have experienced the apocalyptic repercussions of a nuclear weapon not only endorse the necessity of abolition but themselves underscore that the pursuit of disarmament is not just a policy objective but a moral responsibility—one that demands collective action and a commitment to preventing future generations from experiencing the unspeakable tragedies of the past.

The 2023 Hiroshima-ICAN Academy on Nuclear Weapons and Global Security is organized by Hiroshima Prefecture and the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize laureate. The goal of the program is to educate young leaders who can make concrete contributions toward a more peaceful and secure world. In addition to several peers from the United States, I joined other participants from China, Italy, India, Kenya, Lebanon, Ukraine, and more.

The 2023 Hiroshima-ICAN Academy hosted several online lectures and four days of educational sessions in Hiroshima, Japan. Online webinars gave participants the opportunity to interact with famous activists, such as Koko Kondo, Mary Dickson, and Melissa Parke, and hear from esteemed professionals in the nuclear field like Dr. Vincent Intondi and Izumi Nakamitsu. We learned about the suffering of downwinders in the United States, ICAN’s initiatives towards abolition, the UN’s disarmament efforts, and the racial history of nuclear weapons testing and usage. Prior to the online portion of the academy, I knew nothing of the intersectionality of nuclear weapons threats.

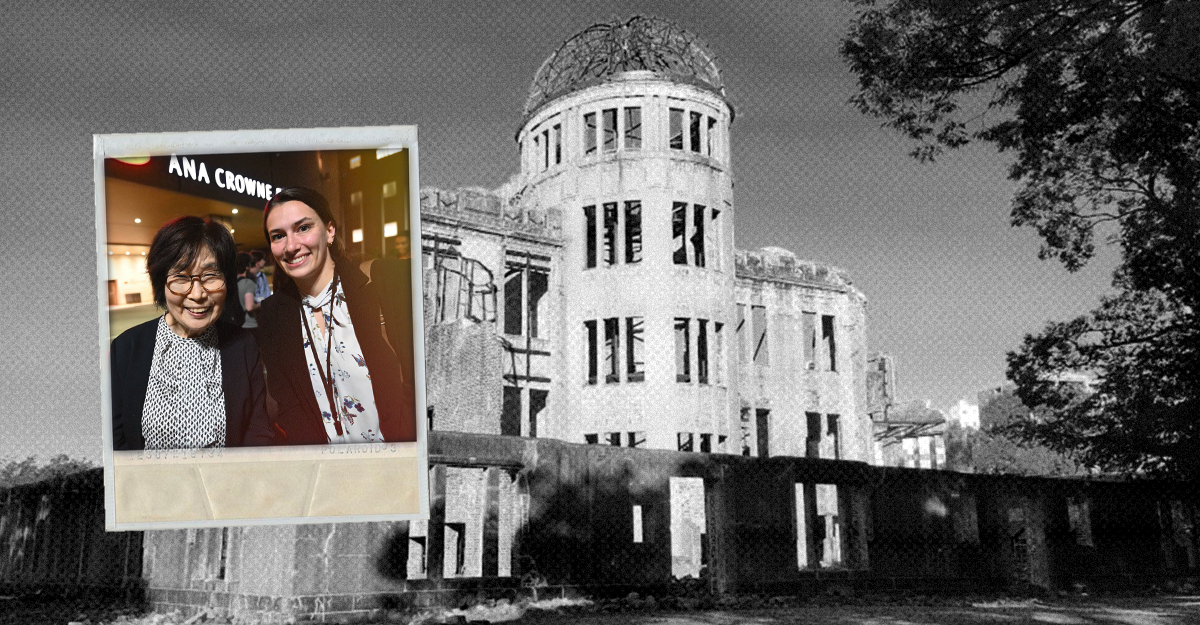

While in Hiroshima, we had a busy week of meetings, lectures, and tours, including a guided tour of the Peace Park and meetings with Hiroshima Mayor Kazumi Matsui, Hiroshima Governor Hidehiko Yuzaki, and atomic bomb survivor Keiko Ogura. Together, we learned about Hiroshima nonprofit efforts to support atomic bomb survivors, discussed the ecological effects and colonial history of nuclear weapons testing, and planned how to effectively interject discussions about disarmament in our respective communities.

The most memorable part of the ICAN Academy for me was speaking with atomic bomb survivors, also known as hibakusha. I was fortunate to spend several hours with hibakusha Ms. Sadae Kasaoka, who was 12 years old when the atomic bomb dropped. Ms. Kasaoka urged all of the Hiroshima ICAN participants to share her story with our communities.

I was struck by Ms. Kasaoka’s bravery and resilience. No human wants to dwell on the most traumatic experience of their lives, let alone recount it for hundreds of listeners each year. However, Ms. Kasaoka has been doing so year after year for the benefit of our education.

Like many children in Japan during World War II, Ms. Kasaoka would help demolish wooden houses to prevent the spread of fire after air raids. Her life consisted of work, rushing to bomb shelters, and fearing for her family. On the morning of August 6, 1945, Ms. Kasaoka was in her home when the atomic bomb was dropped. Ms. Kasaoka saw a blast of light through the window of her home and was knocked down by the initial blast of the bomb. Hours later, the images she would see in her town would be seared into her memory forever.

During our conversation with Ms. Kasaoka, she recounted the destruction of her friends’ homes and vividly remembered watching humans walk up the mountain, skin hanging off of their bodies like ghosts. When her father was brought back to the house on a stretcher several hours later, she did not recognize him because his face had significantly swelled and his skin was burnt black. She would spend the next two days applying cucumbers and potatoes to his skin to cool the burning while picking maggots out of her father’s flesh as he pleaded with her for water. Later, she would be brought a bag of ashes and hair, allegedly belonging to her mother. The atomic bomb would leave Sadae Kasaoka an orphan like thousands of young Japanese children in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In Ms. Kasaoka’s words, “This is the reality of war.” Her story is only one of hundreds of thousands.

Prior to my fellowship with FAS, like many young Americans, I believed that nuclear weapons were a rusting relic of the past. At the end of my fellowship, I recognize these weapons are being cleaned and shined as arsenals expand and the risk of nuclear weapons use grows to be higher than at any time since the Cold War. Both FAS and the ICAN Academy led to my realization of a sobering truth: nuclear weapons cannot coexist with mankind indefinitely.

The Federation of American Scientists values diversity of thought and believes that a range of perspectives — informed by evidence — is essential for discourse on scientific and societal issues. Contributors allow us to foster a broader and more inclusive conversation. We encourage constructive discussion around the topics we care about.