Life-of-the-Ship Reactors and Accelerated Testing of Naval Propulsion Fuels and Reactors

This special report is a result of the FAS U.S.-French Naval Nuclear Task Force and is focused on the life-of-the-ship reactors and role of accelerated testing on naval propulsion fuels and reactors. The report is written by Dr. George Moore.

https://issuu.com/fascientists/docs/life-of-the-ship-reactors-and-accel

France’s Choice for Naval Nuclear Propulsion: Why Low-Enriched Uranium Was Chosen

This special report is a result of an FAS task force on French naval nuclear propulsion and explores France’s decision to switch from highly-enriched uranium (HEU) to low-enriched uranium (LEU). By detailing the French Navy’s choice to switch to LEU fuel, author Alain Tournyol du Clos — a lead architect of France’s nuclear propulsion program — explores whether France’s choice is fit for other nations.

https://issuu.com/fascientists/docs/france_s_choice_for_naval_nuclear_p

President’s Message: What Will the Next President’s Nuclear Policies Be?

The presidential candidates’ debates will soon occur, and the voters must know where the candidates stand on protecting the United States against catastrophic nuclear attacks. While debating foreign policy and national security issues, the Democratic and Republican candidates could reach an apparent agreement about the greatest threat facing the United States, similar to what happened on September 30, 2004. During that first debate between then President George W. Bush and then Senator John Kerry (now Secretary of State), they appeared to agree when posed the question: ”What is the single most serious threat to the national security to the United States?” Kerry replied, “Nuclear proliferation. Nuclear proliferation.” He went on to critique what he perceived as the Bush administration’s slow rate of securing hundreds of tons of nuclear material in the former Soviet Union.

When Bush’s turn came, he said, “First of all, I agree with my opponent that the biggest threat facing this country is weapons of mass destruction in the hands of a terrorist network. And that’s why proliferation is one of the centerpieces of a multi-prong strategy to make the country safer.”1 President Bush also mentioned that his administration had devoted considerable resources toward securing nuclear materials in the former Soviet Union and elsewhere.

Despite this stated agreement, the two candidates disagreed considerably on how to deal with nuclear threats. Today, the leading Democratic and Republican candidates appear to be in even further disagreement on this issue than Bush and Kerry, while nuclear dangers arguably look even more dangerous. I will not analyze each candidate’s views, especially because their views could change between the time of writing this president’s message in late June and the start of the debates in September. I think it is more useful here to outline several of the major themes on nuclear policy that should be addressed in the campaign and during the debates.

The most fundamental theme is: what is the role or roles of U.S. nuclear weapons? Deterrence is the easy answer, but against what or whom? That is, should nuclear weapons only be used when another nuclear-armed state uses them against the United States or U.S. allies or should the mission be expanded to include deterrence against massive biological attacks, for instance? Assuming the next president wants his policy team to elucidate that the sole purpose of nuclear weapons is solely for deterring others’ use of nuclear weapons, the next question is: should the United States have a no-first-use policy of not launching nuclear weapons before others launch nuclear weapons?

Such a policy would emphasize having nuclear weapons that would be secure against a nuclear attack that would come first from an enemy. For example, deployed submarines underneath the surface of the oceans would provide this type of secure force, whereas land-based nuclear-armed missiles and bombers could be more vulnerable to an incoming attack. Would the next president want to reduce the nuclear triad to a single leg of ballistic missile submarines? This decision would require considerable political courage and would have to withstand opposition from proponents who would want to keep the Air Force’s legs of the triad of intercontinental ballistic missiles and strategic bombers. However, the Air Force could transform its nuclear forces to have solely conventionally-armed missiles and bombers and in effect, it could have more militarily usable weapons that would not have to cross the high threshold of nuclear use.

Another argument for shifting to having just submarines deploy nuclear weapons is the cost savings from having to maintain nuclear arms for land-based missiles and bombers. This leads to the debate topic of whether the United States should spend up to $1 trillion in the coming decades on “modernizing” its nuclear forces. All three legs of the triad are showing their age. Each leg will require $100 billion or more to upgrade the launching platforms of missiles, bombers, and submarines, and in addition, there would be several $100 billion more in refurbishing and maintaining the half dozen types of nuclear warheads plus the related infrastructure costs. Would a presidential candidate seize the opportunity to save hundreds of billions of dollars by smartly downsizing U.S. nuclear forces?

The candidates would have to confront the promises made by the Obama administration to key Republican senators to “modernization” of the nuclear arsenal. This commitment was a crucial part of the bargain to convince enough Republican senators to vote in favor of the New START agreement with Russia in 2010. On June 17, 2016, Senator John McCain (R-Arizona) and Senator Bob Corker (R-Tennessee) sent a letter to President Obama to remind him of this commitment.2 Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) and former Under Secretary of State Ellen Tauscher have called for Congress not to fund the proposed nuclear-armed cruise missile, known as the Long Range Standoff Weapon (LRSO), because: there is no compelling military need; it could lower the threshold of nuclear use; and it is too costly at an estimate of up to $30 billion.3

New START was a relatively modest reduction in strategic nuclear forces. The tough challenge for the next president is whether further reductions with Russia are even possible given the heightened tensions over Ukraine and other sticking points between Russia and NATO, as well as between Russia and the United States. Going much lower in numbers of strategic nuclear arms might require a rethinking of the nuclear weapons configurations in both nuclear superpowers. Thus, the next president will need a highly capable team who will understand U.S.-Russia relations, the concerns of certain NATO allies, the concerns of East Asian allies, namely Japan and South Korea, as well as the effect on China.

China has remained apart from nuclear arms reductions, although Chinese leaders have made their views clear that they want to ensure that China has a secure nuclear deterrent. While China has for decades been content to have a relatively small nuclear force, there have been signs in recent years of a buildup and modernization of Chinese nuclear weapons and associated delivery platforms, particularly the ballistic missile submarines that have recently demonstrated (after years of technical setbacks) the capability to deploy further out to sea and within striking range of the United States. The next president will have to wrestle with a host of political and military challenges from China, and in the nuclear area, he or she will have to determine how best to deter China without having China further buildup its nuclear arms.

A major issue of concern to China is the potential buildup of U.S. missile defense beyond just a relatively small number of missile interceptors. The ostensible purpose of this very limited U.S. missile defense system is to counter North Korean missiles and Iranian missiles, which are still relatively few in number in terms of longer range missiles. China has been concerned that even a limited or “small” missile defense system could threaten China’s capability to launch a retaliatory nuclear attack against the United States.

In recent weeks, some senators have opened up a debate about whether to remove the word “limited” in the Missile Defense Authorization Act. In particular, Senator Tom Cotton (R-Arkansas) and Senator Kelly Ayotte (R-NH) have taken such action in the Senate Armed Services Committee, while Senator Edward Markey (D-Mass.) has sought to restore the word “limited.” Over the past 20 years, the debate in Congress has shifted, such that there is really no debate about whether the United States should have some strategic missile defense system; instead the debate has been about how much the United States should spend on a limited system and how limited it should be. The next president has an opportunity to renew this debate on first principles: that is, whether a strategic missile system provides some crisis stability, whether this system would impede further nuclear arms reductions, and whether this system could achieve adequate technical effectiveness.

I will save (until a future president’s message) the challenges of Iran and North Korea. For this message, I will close by noting that both the George W. Bush administration and the Barack Obama administration made significant progress in securing and reducing nuclear materials that could be vulnerable to theft by terrorists. Preventing nuclear terrorism is very much a bipartisan issue, as is reducing any and all nuclear dangers. How will the next president build on the tremendous legacies of the two previous presidents in keeping the world’s leaders focused on achieving much better security over nuclear materials? Should the Nuclear Security Summit process be continued? What other cooperative international mechanisms can and should be implemented? As the leader of the world’s superpower, the next president must lead and must cooperate with other leaders in the shared endeavor of making the world safer against nuclear threats. As citizens, let’s encourage the candidates to debate seriously these issues and provide practical plans for reducing nuclear dangers.

I am grateful to all the supporters of FAS and readers of the PIR.

Public Interest Report: June 2016

President’s Message: What Will the Next President’s Nuclear Policies Be?

by Charles D. Ferguson

The presidential candidates’ debates will soon occur, and the voters must know where the candidates stand on protecting the United States against catastrophic nuclear attacks.

Three-Dimensional Arms Control: A Thought Experiment

by Heather Williams

In order to move beyond old-school arms control, it is useful to revisit the initial goals of arms control.

Welcome Back, Multiple Object Kill Vehicles

by Debalina Ghoshal

Ever since the United States began developing a missile defense system, the focus has been on pursuing a

robust missile defense system.

Nuclear Security and Safety in America: A proposal on illicit trafficking of radioactive material and orphan sources

by Diva Puig

The special nature of nuclear energy requires particular safety and security conditions and stronger protective measures. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), as do other international and regional organizations, provides assessment, but it does not know a great deal about the security status of most Member States.

More From FAS: Highlights and Achievements Throughout Recent Months

Three-Dimensional Arms Control: A Thought Experiment

The George W. Bush Administration is not typically viewed as the paragon of arms control. This was the Administration that withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty in 2002, agreed to the Moscow Treaty that same year with no verification provisions, and generally eschewed traditional approaches to arms control, including negotiations and treaties, as Cold War legacies. To be sure, in practice the Administration’s minimal attempts at arms control failed to produce significant results; but in principle, creative and new approaches cannot be so readily discarded. With that in mind, this article is a thought experiment. Some of the proposals suggested here are radical and come with major hurdles, but a non-traditional approach to arms control, based on opportunities rather than challenges, can hopefully generate new thinking.

Welcome Back, Multiple Object Kill Vehicles

Ever since the United States began developing a missile defense system, the focus has been on pursuing a robust missile defense system. As not much progress has been made on boost phase interception, it becomes mandatory to study a technology that could make the midcourse system of the ballistic missile more vulnerable to enemy missile defense system. At present, with counter measures like decoys, chaffs, and multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRVs), the mid-course phase of the ballistic missile becomes a complicated phase of interception. The Multiple Object Kill Vehicle (MOKV), a program of the United States, is believed to negate these challenges of the missile defense system in the mid-course phase.

Nuclear Security and Safety in America: A proposal on illicit trafficking of radioactive material and orphan sources

The special nature of nuclear energy requires particular safety and security conditions and stronger protective measures. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), as do other international and regional organizations, provides assessment, but it does not know a great deal about the security status of most Member States. It is necessary to learn of and determine the needs and concerns of a State for improving legal framework, reviewing detection of and response to illicit trafficking, and in order to develop a strategic plan that will enhance work that results in tangible improvements of security.

Nuclear law has an international dimension because the risks of nuclear materials do not respect borders. Terrorist acts defy the law; they don’t belong to a State. The possibility of transboundary impacts requires harmonization of policies, programs, and legislation. Several international legal instruments have been adopted in order to codify obligations of States in various fields, which can limit national legislation. There are legal and governmental responsibilities regarding the safe use of radiation sources, radiation protection, the safe management of radioactive waste, and the transportation of radioactive material.

The terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 represented a clear challenge, but they must not stand as obstacles in the development of nuclear technology. It is necessary to reinforce these efforts in order to improve nuclear energy security, because energy is a vital issue that cannot wait.

More From FAS: Highlights and Achievements Throughout Recent Months

NGOs AND THEIR ROLES IN THE VERIFICATION OF NUCLEAR AGREEMENTS – APRIL 2016

After finishing up his second MacArthur Foundation-sponsored research project on issues related to verifying a nuclear agreement with Iran, Christopher Bidwell, FAS Senior Fellow for Nonproliferation Law and Policy, and his team are now focused on a third project that will look at the increased role played by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in verifying compliance and noncompliance with nuclear nonproliferation obligations. Special attention will be paid to how the privacy rights of entities and individuals whose data are used to make a determination can be protected.

35 NOBEL LAUREATES CALL ON WORLD LEADERS TO TAKE ACTION ON NUCLEAR TERRORISM – MARCH 2016

In a letter dated March 26, 2016, 35 Nobel Laureates from physics, chemistry, and medicine urged national leaders attending President Obama’s fourth and final Nuclear Security Summit on March 31st to reduce the risk of nuclear or radiological terrorism to near-zero in three sectors. The signees stressed that because terrorist threats “cross national boundaries,” they “require the concerted work of all nations to prevent… terrorist acts from happening.” They also “urge” world leaders “to devote the necessary resources to make further substantial progress in the coming years to real risk reduction in preventing nuclear and radiological terrorism.” The letter, written by Dr. Burton Richter, a Nobel Laureate in physics and the Paul Pigott Professor in the Physical Sciences at Stanford University and Director Emeritus, Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, and Dr. Charles D. Ferguson, President of FAS, and list of signees is available online at: https://fas.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/nobel-laureates-letter-to-nss-march-20162.pdf.

REPORT: SUGGESTIONS ABOUT JAPAN’S NUCLEAR FUEL RECYCLING POLICY BASED ON U.S. CONCERNS – MARCH 2016

To date, Japan’s peaceful nuclear energy use has taken the form of a nuclear fuel recycling policy that reprocesses spent fuel and effectively utilizes the plutonium retrieved in light water reactors (LWRs) and fast reactors (FRs). With the aim to complete recycling domestically, Japan has introduced key technology from abroad and has further developed its own technology and industry. However, Japan presently seems to have issues regarding its recycling policy and plutonium management and, because of recent increasing risks of terrorism and nuclear proliferation in the world, the international community seeks much more secure use of nuclear energy. Yusei Nagata, an FAS Research Fellow from MEXT, Japan, analyzes U.S. experts’ opinions and concerns about Japan’s problem and considers what Japan can (and should) do to solve it.. A full version of the report can be accessed online at: https://fas.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/japannukefuelrecyling_final.pdf.

REPORT: USE OF MICROBIAL FORENSICS IN THE MIDDLE EAST/NORTH AFRICA REGION – MARCH 2016

In this study, Christopher Bidwell and Dr. Randall Murch explore the use of microbial forensics as a tool for creating a common base line for understanding biologically-triggered phenomena, as well as one that can promote mutual cooperation in addressing these phenomena. A particular focus is given to the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) region, as it has been forced to deal with multiple instances of both naturally-occurring and man-made biological threats over the last 10 years. Although the institution of a microbial forensics capability in the MENA region (however robust) is still several years away, establishing credibility of the results offered by microbial forensic analysis performed by western states and/or made today in workshops and training have the ability to prepare the policy landscape for the day in which the source of a bio attack, either man-made or from nature, needs to be accurately attributed. A full version of the report can be accessed online at: /pub-reports/microbial-forensics-middle-east-north-africa/.

REPORT: USE OF ATTRIBUTION AND FORENSIC SCIENCE IN ADDRESSING BIOLOGICAL WEAPON THREATS – FEBRUARY 2016

The threat from the manufacture, proliferation, and use of biological weapons (BW) is a high priority concern for the U.S. Government. As reflected in U.S. Government policy statements and budget allocations, deterrence through attribution (“determining who is responsible and culpable”) is the primary policy tool for dealing with these threats. According to those policy statements, one of the foundational elements of an attribution determination is the use of forensic science techniques, namely microbial forensics. In this report, Christopher Bidwell and Kishan Bhatt, an FAS summer research intern and undergraduate student studying public policy and global health at Princeton University, look beyond the science aspect of forensics and examine how the legal, policy, law enforcement, medical response, business, and media communities interact in a bioweapon’s attribution environment. The report further examines how scientifically based conclusions require credibility in these communities in order to have relevance in the decision making process about how to handle threats. The report can be found online at: /pub-reports/biological-weapons-and-forensic-science/.

THE NEW B61-12 GUIDED NUCLEAR BOMB – JANUARY 2016

From the start of the development of the new $10 billion B61-12 guided nuclear bomb, FAS has been at the forefront of providing the public with factual information about the status and capabilities of the program. In November 2015, Hans Kristensen, Director of the FAS Nuclear Information Project, was featured in a PBS Newshour program about the weapon where former STRATCOM commander and Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General James Cartwright confirmed FAS assessments that the increased accuracy of the B61-12 could make it a more usable weapon [/blogs/security/2015/11/b61-12_cartwright/]. In early 2016, FAS and NRDC used a government video of a B61-12 test drop to analyze the bomb’s increased accuracy and earth-penetrating capability [/blogs/security/2016/01/b61-12_earth-penetration/]. The analysis was used in a New York Times feature article, “As U.S. Modernizes Nuclear Weapons, ‘Smaller’ Leaves Some Uneasy.” 1

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE CONFRONTS “CLIMATE CHANGE” – MARCH 7, 2016

The official entry of the term “climate change” in the latest revision of the Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms reflects a growing awareness of the actual and potential impacts of climate change on military operations. Steven Aftergood, Director of the FAS Project on Government Secrecy, reported in Secrecy News that according to a Pentagon directive issued in January 2016, “The DoD must be able to adapt current and future operations to address the impacts of climate change in order to maintain an effective and efficient U.S. military.” Among other things, the new directive requires the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and the Director of National Intelligence to coordinate on “risks, potential impacts, considerations, vulnerabilities, and effects [on defense intelligence programs] of altered operating environments related to climate change and environmental monitoring.” In a report to Congress last year, the DoD said that “The Department of Defense sees climate change as a present security threat, not strictly a long-term risk.” Read Aftergood’s analysis in full here: /blogs/secrecy/2016/01/dod-climate/.

THE NEW NUCLEAR CRUISE MISSILE – OCTOBER-DECEMBER 2015

The FAS Nuclear Information Project provided the public with important analysis about the mission and capabilities of the new nuclear air-launched cruise missile the Air Force is developing: the Long-Range Standoff missile (LRSO). The analysis was the first to highlight an overview of the mission government officials say the missile is needed for, a mission that includes a worrisome nuclear war-fighting role [/blogs/security/2015/10/lrso-mission/]. Hans Kristensen was also quick to point out that a new long-range conventional air-launched cruise missile being deployed by the Air Force could do much of the LRSO mission and he recommended canceling the LRSO, a measure which would save $20-$30 billion [/blogs/security/2015/12/lrso-jassm/].

PAKISTANI NUCLEAR FORCES – OCTOBER 2015

FAS research on the status and modernization of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons was covered extensively in news media reports in connection with Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s visit to Washington in October 2015. The FAS Nuclear Notebook, co-authored by Hans Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, FAS Senior Fellow for Nuclear Policy, published by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, estimated that Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal has grown by 20 weapons since 2011 to 130 warheads presently, including new tactical nuclear weapons. The research was used by the New York Times in a background article, “U.S. Set to Sell Fighter Jets to Pakistan, Balancing Pressure on Nawaz Sharif,”2 and an editorial, “The Pakistan Nuclear Nightmare,”3 as well as by the Associated Press and Indian and Pakistani news media. The Nuclear Notebook can be accessed at: https://fas.org/blogs/security/2015/10/pakistan-notebook/.

ODNI ISSUES TRANSPARENCY IMPLEMENTATION PLAN – OCTOBER 28, 2015

Transparency is not ordinarily a trait that one associates with intelligence agencies. But the Office of the Director of National Intelligence has released a transparency implementation plan that establishes guidelines for increasing public disclosure of information by and about U.S. intelligence. Based on a set of principles on transparency that were published earlier last year, the plan prioritizes the objectives of transparency and describes potential initiatives that could be undertaken. Thus, the plan aims “to provide more information about the IC’s governance framework; to provide more information about the IC’s mission and activities; to encourage public engagement [by intelligence agencies in social media and other venues]; and to institutionalize transparency policies and procedures.” FAS Secrecy News reports that the plan neither includes any specific commitments nor sets any deadlines for action. Moreover, it is naturally rooted in self-interest. Its purpose is explicitly “to earn and retain public trust” of U.S. intelligence agencies. Nonetheless, it has the potential to provide new grounds for challenging unnecessary secrecy and to advance a corresponding “cultural reform” in the intelligence community. Read Aftergood’s analysis here: /blogs/secrecy/2015/10/transparency-plan/.

DOD SECURITY-CLEARED POPULATION DROPS AGAIN – OCTOBER 7, 2015

The number of people in the Department of Defense holding security clearances for access to classified information declined by 100,000 in the first six months of FY2015, recounts FAS Secrecy News. The latest available data show 3.8 million DoD employees and contractors with security clearances, down from 3.9 million earlier in 2015, and a steep 17.4 percent drop from 4.6 million two years ago. Furthermore, only 2.2 million of the 3.8 million cleared DoD personnel are actually “in access,” meaning that they have current access to classified information. Thus, further significant reductions in clearances would seem to be readily achievable by shedding those who are not currently “in access.” The total number of security-cleared persons government-wide is roughly 0.5 million higher than the number of DoD clearances, putting it at around 4.3 million, down from 5.1 million in 2013. The new DoD security clearance numbers were presented in the latest quarterly report on Insider Threat and Security Clearance Reform, FY2015 Quarter 3, September 2015. The reduction in security clearances is not simply a reflection of programmatic or budgetary changes – rather, it has been defined as a policy goal in its own right. A bloated security bureaucracy is harder to manage, more expensive, and more susceptible to catastrophic security failures than a properly streamlined system would be. The full post is available to view here: /blogs/secrecy/2015/10/clearances-down/.

President’s Message: Reinvention and Renewal

From its inception 70 years ago, the founders and members of the Federation of American Scientists were reinventing themselves. Imagine yourself as a 26-year old chemist having participated in building the first atomic bombs. You may have joined because your graduate school adviser was going to Los Alamos and encouraged you to come. You may also have decided to take part in the Manhattan Project because you believed it was your patriotic duty to help America acquire the bomb before Nazi Germany did. And even when Hitler and the Nazis were defeated in May 1945, you continued your work on the bomb because the war with Japan was still raging in the Pacific. Moreover, by then, you may have felt like Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Scientific Director, that the project was “technically sweet”—you had to see it through to the end.

But when the end came—the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—in August 1945, you may have had doubts about whether you should have built the bombs, or you may have at least been deeply concerned about the future of humanity in facing the threat of nuclear destruction. What should you then do? About a thousand of the “atomic scientists” throughout the country at various sites, such as Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Chicago began to organize and discuss the implications of this new military technology.1

This political activity was not natural for scientists. Almost all of the founders of FAS were so-called “rank-and-file” scientists in their 20s and 30s. Members of this youth brigade—led by Dr. Willie Higinbotham, who was in his mid-30s but who looked younger—arrived in Washington. With their “crew cuts, bow ties, and tab collars [testifying] to their youth,” they roamed the halls of Capitol Hill, educating Congressmen and their staffs.2 Newsweek called them the “reluctant lobby.” As a history of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) notes, “Part of their reluctance stemmed from their conviction that the cause of science should not be dragged through the political arena.”3

Fortunately, these scientists persisted and achieved the notable result of successfully lobbying for civilian control of the AEC. While they also wanted international control of nuclear energy, they fell short of that goal. However, they were indefatigable in their educational efforts on promoting peaceful uses of nuclear energy and warning about the dangers of nuclear arms races.

Throughout FAS’s seven decades, the organization has transformed itself into various incarnations depending on the issues to be addressed and the resources available for operating FAS. To learn about this continual reinvention, I invite you to read all the articles in this special edition of the Public Interest Report. This edition has an all-star list of writers—many of whom have served in leadership roles at FAS and others who have deep, scholarly knowledge of FAS. These authors discuss many of the accomplishments of FAS, but they also do not shy away from mentioning several of the challenges faced by FAS.

What will FAS achieve and what adversities will occur in the next 70 years? As scientists know, research results are difficult, if not impossible, to predict. However, we do know that the mission of FAS is as relevant as ever, perhaps even more so than it was 70 years ago. Nuclear dangers—the founding call to action—have become more complex; instead of one nuclear weapon state in 1945, there are now nine countries with nuclear arms. Instead of a few nuclear reactors in 1945, today there are more than 400 power reactors in 31 countries and more than 100 research reactors in a few dozen countries. Moreover, some non-nuclear weapon states have acquired or want to acquire uranium enrichment or reprocessing facilities that can further sow the seeds of future proliferation of nuclear weapons programs. For these dangers alone, FAS has the important purpose to serve as a voice for scientists, engineers, and policy experts working together to develop practical means to reduce nuclear risks.

FAS has also served and will continue to serve as a platform for innovative projects that shine spotlights on government policies that work and don’t work and how to improve these policies. In particular, for a quarter century, the Government Secrecy Project, directed by Steve Aftergood, has worked to reduce the scope of official secrecy and to promote public access to national security information.

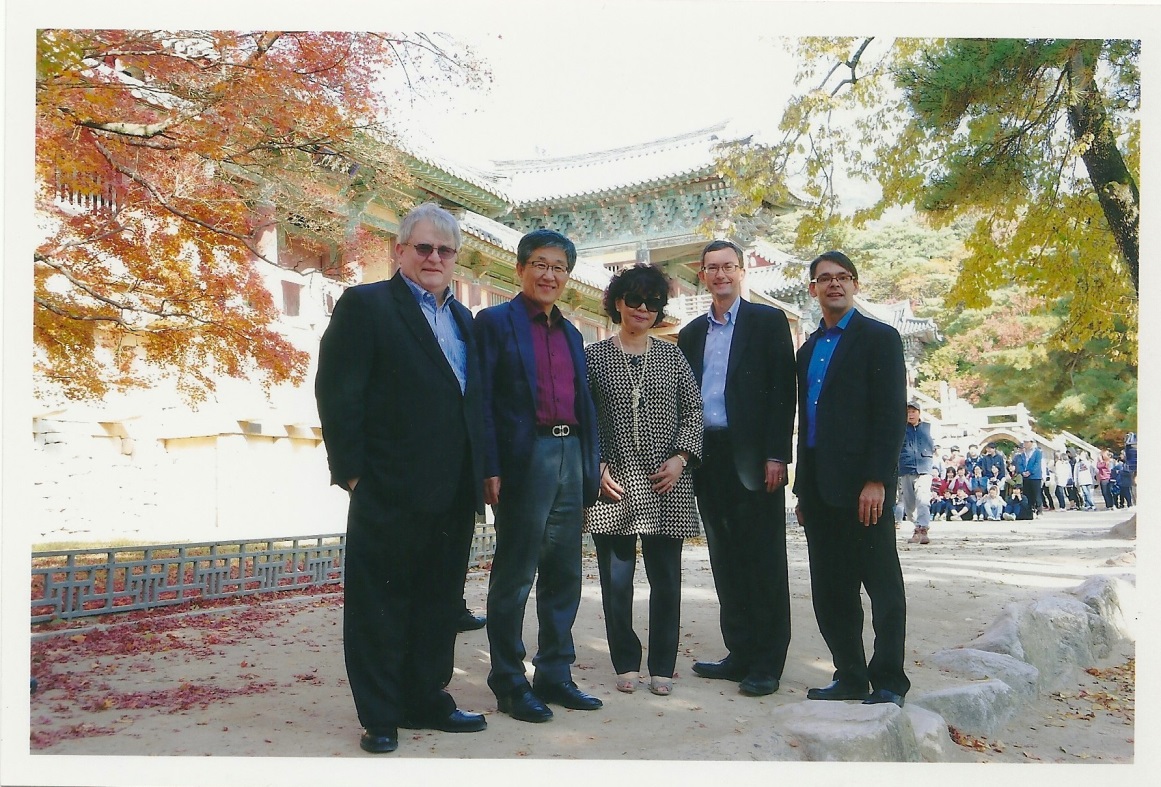

Nuclear energy research travel (cosponsored by FAS) to the Republic of Korea, November 7, 2013, taken at Gyeongju National Museum: From left to right: Paul Dickman, Argonne National Laboratory, Lee Kwang-seok, Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute, Florence Lowe-Lee, Global America Business Institute, Everett Redmond, Nuclear Energy Institute, and Charles D. Ferguson, FAS.

FAS has also contributed to the public debate on bio-safety and bio-security. Daniel Singer (one of the contributors to this issue) and Dr. Maxine Singer have been active for more than 50 years in bio-ethics. Dr. Barbara Hatch Rosenberg and Dorothy Preslar in the 1990s and early 2000s worked through FAS to develop methods (such as an email list serve, which was cutting edge in the 1990s) to connect biologists and public health experts around the globe to identify, monitor, and evaluate emerging diseases. In recent years, Chris Bidwell, Senior Fellow for Law and Nonproliferation Policy, has led projects examining potential biological attacks or outbreaks and the forensic evidence needed for a court of law or government decision making in countries in the Middle East and North Africa. The Nuclear Information Project, directed by Hans Kristensen, continues its longstanding work on providing the public with reliable information and analysis on the status and trends of global nuclear weapons arsenals. Its famed Nuclear Notebook, co-authored by Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, a senior fellow at FAS, is one of the most widely referenced sources for consistent data about the status of the world’s nuclear weapons.

I believe the greatest renewal and reinvention of FAS has been emerging in the past three years with the creation of networks of experts to work together to prevent threats from becoming global catastrophes. FAS has organized task forces that have provided practical guidance to policy makers about the implementation of the agreement on Iran’s nuclear program and that have examined the benefits and risks of the use of highly enriched uranium in naval nuclear propulsion. As I look to the next 70 years, I foresee numerous opportunities for FAS to seize by being the bridge between the technical and policy communities.

I am very grateful for the support of FAS’s members and donors and encourage you to invite your friends and colleagues to join FAS. Happy 70th anniversary!

The Legacy of the Federation of American Scientists

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) formed after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, precisely because many scientists were genuinely concerned for the fate of the world now that nuclear weapons were a concrete reality. They passionately believed that, as scientific experts and citizens, they had a duty to educate the American public about the dangers of living in the atomic age. Early in 1946, the founding members of FAS established a headquarters in Washington, D.C.,and began to coordinate the political and educational activities of many local groups that had sprung up spontaneously at universities and research facilities across the country. The early FAS had two simultaneous goals: the passage of atomic energy legislation that would ensure civilian control and promote international cooperation on nuclear energy issues, and the education of the American public about atomic energy. In addition, from its very inception, FAS was committed to promoting the broader idea that science should be used to benefit the public. FAS aspired, among other things, “To counter misinformation with scientific fact and, especially, to disseminate those facts necessary for intelligent conclusions concerning the social implications of new knowledge in science,” and “To promote those public policies which will secure the benefits of science to the general welfare.”

Scientists and Nuclear Weapons, 1945-2015

On August 8, 2015, twenty-nine scientists sent a letter to President Obama in support of the agreement with Iran that would block (or at least significantly delay) Iran’s pathways to obtain nuclear weapons. This continues a tradition that began seventy years ago of scientists having a role in educating the public, advising government officials, and helping shape policy about nuclear weapons.

Soon after the end of World War II, scientists mobilized themselves to address the pressing issues of how to deal with the many consequences of atomic energy. Of prime importance was the question of which government entity would control the research, development and production of atomic weapons, and any peaceful applications. Would it be the military, as it was during World War II, or a civilian agency, such as the newly created Atomic Energy Commission (AEC)?

Government Secrecy and Censorship

From its beginning, the Federation of American Scientists has been immersed in policies and issues regarding government secrecy and censorship. By the time World War II broke out, the fission process had been observed, followed by detection of the neutron, and recognition of induced uranium fission. In the early 1940s, some scientists in the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and Germany realized the potential for nuclear weapons.

The three atomic bombs detonated in the summer of 1945 were created and assembled at secret U.S. government sites by a mixed pedigree of scientists, engineers, and military officers. The decision to drop two of them on Japanese cities was determined by military and political events then occurring, particularly in the final year of World War II.

Our Soviet wartime ally, excluded from the American, British, and Canadian nuclear coalition, used its own espionage network to remain informed. Well-placed sympathizers and spies conveyed many essential details of nuclear-explosive development. Through this network, Stalin learned of the Manhattan Project and the Trinity test. As the German invaders began to retreat from Soviet borders, he established his own secret nuclear development project.

Frequent contributor and longtime FAS member Dr. Alexander DeVolpi has just published a new book, Cold War Brinkmanship. Dr. DeVolpi’s firsthand account “chronicles the half-century nuclear crisis,” with several mentions of and citations to the work of FAS. It is available now in paperback on Amazon.