Increasing Capacity and Community Engagement for Environmental Data

Summary

Environmental justice (EJ) is a priority issue for the Biden Administration, yet the federal government lacks capacity to collect and maintain data needed to adequately identify and respond to environmental-justice (EJ) issues. EJ tools meant to resolve EJ issues — especially the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s EJSCREEN tool — are gaining national recognition. But knowledge gaps and a dearth of EJ-trained scientists are preventing EJSCREEN from reaching its full potential. To address these issues, the Administration should allocate a portion of the EPA’s Justice40 funding to create the “AYA Research Institute”, a think tank under EPA’s jurisdiction. Derived from the Adinkra symbol, AYA means “resourcefulness and defiance against oppression.” The AYA Research Institute will functionally address EJSCREEN’s limitations as well as increase federal capacity to identify and effectively resolve existing and future EJ issues.

Challenge and Opportunity

Approximately 200,000 people in the United States die every year of pollution-related causes. These deaths are concentrated in underresourced, vulnerable, and/or minority communities. The EPA created the Office of Environmental Justice (OEJ) in 1992 to address systematic disparities in environmental outcomes among different communities. The primary tool that OEJ relies on to consider and address EJ concerns is EJSCREEN. EJSCREEN integrates a variety of environmental and demographic data into a layered map that identifies communities disproportionately impacted by environmental harms. This tool is available for public use and is the primary screening mechanism for many initiatives at state and local levels. Unfortunately, EJSCREEN has three major limitations:

- Missing indicators. EJSCREEN omits crucial environmental indicators such as drinking-water quality and indoor air quality. OEJ states that these crucial indicators are not included due to a lack of resources available to collect underlying data at the appropriate quality, spatial range, and resolution.

- Small areas are less accurate. There is considerable uncertainty in EJSCREEN environmental and demographic estimates at the census block group (CBG) level. This is because (i) EJSCREEN’s assessments of environmental indicators can rely on data collected at scales less granular than CBG, and (ii) some of EJSCREEN’s demographic estimates are derived from surveys (as opposed to census data) and are therefore less consistent.

- Deficiencies in a single dataset can propagate across EJSCREEN analyses. Environmental indicators and health outcomes are inherently interconnected. This means that subpar data on certain indicators — such as emissions levels, ambient pollutant levels in air, individual exposure, and pollutant toxicity — can compromise the reliability of EJSCREEN results on multiple fronts.

These limitations must be addressed to unlock the full potential of EJSCREEN as a tool for informing research and policy. More robust, accurate, and comprehensive environmental and demographic data are needed to power EJSCREEN. Community-driven initiatives are a powerful but underutilized way to source such data. Yet limited time, funding, rapport, and knowledge tend to discourage scientists from engaging in community-based research collaborations. In addition, effectively operationalizing data-based EJ initiatives at a national scale requires the involvement of specialists trained at the intersection of EJ and science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). Unfortunately, relatively poor compensation discourages scientists from pursuing EJ work — and scientists who work on other topics but have interest in EJ can rarely commit the time needed to sustain long-term collaborations with EJ organizations. It is time to augment the federal government’s past and existing EJ work with redoubled investment in community-based data and training.

Plan of Action

EPA should dedicate $20 million of its Justice40 funding to establish the AYA Research Institute: an in-house think tank designed to functionally address EJSCREEN’s limitations as well as increase federal capacity to identify and effectively resolve existing and future EJ issues. The word AYA is the formal name for the Adinkra symbol meaning “resourcefulness and defiance against oppression” — concepts that define the fight for environmental justice.

The Research Institute will comprise three arms. The first arm will increase federal EJ data capacity through an expert advisory group tasked with providing and updating recommendations to inform federal collection and use of EJ data. The advisory group will focus specifically on (i) reviewing and recommending updates to environmental and demographic indicators included in EJSCREEN, and (ii) identifying opportunities for community-based initiatives that could help close key gaps in the data upon which EJSCREEN relies.

The second arm will help grow the pipeline of EJ-focused scientists through a three-year fellowship program supporting doctoral students in applied research projects that exclusively address EJ issues in U.S. municipalities and counties identified as frontline communities. The program will be three years long so that participants are able to conduct much-needed longitudinal studies that are rare in the EJ space. To be eligible, doctoral students will need to (i) demonstrate how their projects will help strengthen EJSCREEN and/or leverage EJSCREEN insights, and (ii) present a clear plan for interacting with and considering recommendations from local EJ grassroots organization(s). Selected students will be matched with grassroots EJ organizations distributed across five U.S. geographic regions (Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, Southwest, and West) for mentorship and implementation support. The fellowship will support participants in achieving their academic goals while also providing them with experience working with community-based data, building community-engagement and science-communication skills, and learning how to scale science policymaking from local to federal systems. As such, the fellowship will help grow the pipeline of STEM talent knowledgeable about and committed to working on EJ issues in the United States.

The third arm will embed EJ expertise into federal decision making by sponsoring a permanent suite of very dominant resident staff, supported by “visitors” (i.e., the doctoral fellows), to produce policy recommendations, studies, surveys, qualitative analyses, and quantitative analyses centered around EJ. This model will rely on the resident staff to maintain strong relationships with federal government and extragovernmental partners and to ensure continuity across projects, while the fellows provide ancillary support as appropriate based on their skills/interest and Institute needs. The fellowship will act as a screening tool for hiring future members of the resident staff.

Taken together, these arms of the AYA Research Institute will help advance Justice40’s goal of improving training and workforce development, as well as the Biden Administration’s goal of better preparing the United States to adapt and respond to the impacts of climate change. The AYA Research Institute can be launched with $10 million: $4 million to establish the fellowship program with an initial cohort of 10 doctoral students (receiving stipends commensurate with typical doctoral stipends at U.S. universities), and $6 million to cover administrative expenses and staff expert salaries. Additional funding will be needed to maintain the Institute if it proves successful after launch. Funding for the Institute could come from Justice40 funds allocated to EPA. Alternatively, EPA’s fiscal year (FY) 2022 budget for science and technology clearly states a goal of prioritizing EJ — funds from this budget could hence be allocated towards the Institute using existing authority. Finally, EPA’s FY 2022 budget for environmental programs and management dedicates approximately $6 million to EJSCREEN — a portion of these funds could be reallocated to the Institute as well.

Conclusion

The Biden-Harris Administration is making unprecedented investments in environmental justice. The AYA Research Institute is designed to be a force multiplier for those investments. Federally sponsored EJ efforts involve multiple programs and management tools that directly rely on the usability and accuracy of EJSCREEN. The AYA Research Institute will increase federal data capacity and help resolve the largest gaps in the data upon which EJSCREEN depends in order to increase the tool’s effectiveness. The Institute will also advance data-driven environmental-justice efforts more broadly by (i) growing the pipeline of EJ-focused researchers experienced in working with data, and (ii) embedding EJ expertise into federal decision making. In sum, the AYA Research Institute will strengthen the federal government’s capacity to strategically and meaningfully advance EJ nationwide.

Many grassroots EJ efforts are focused on working with scientists to better collect and use data to understand the scope of environmental injustices. The AYA Research Institute would allocate in-kind support to advance such efforts and would help ensure that data collected through community-based initiatives is used as appropriate to strengthen federal decision-making tools like EJSCREEN.

EJSCREEN and CEJST are meant to be used in tandem. As the White House explains, “EJSCREEN and CEJST complement each other — the former provides a tool to screen for potential disproportionate environmental burdens and harms at the community level, while the latter defines and maps disadvantaged communities for the purpose of informing how Federal agencies guide the benefits of certain programs, including through the Justice40 Initiative.” As such, improvements to EJSCREEN will inevitably strengthen deployment of CEJST.

Yes. Examples include the U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute and the Asian-Pacific Center for Security Studies. Both entities have been successful and serve as primary research facilities.

To be eligible for the fellowship program, applicants must have completed one year of their doctoral program and be current students in a STEM department. Fellows must propose a research project that would help strengthen EJSCREEN and/or leverage EJSCREEN insights to address a particular EJ issue. Fellows must also clearly demonstrate how they would work with community-based organizations on their proposed projects. Priority would be given to candidates proposing the types of longitudinal studies that are rare but badly needed in the EJ space. To ensure that fellows are well equipped to perform deep community engagement, additional selection criteria for the AYA Research Institute fellowship program could draw from the criteria presented in the rubric for the Harvard Climate Advocacy Fellowship.

A key step will be grounding the Institute in the expertise of salaried, career staff. This will offset potential politicization of research outputs.

EJSCREEN 2.0 is largely using data from the 2020 U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, as well as many other sources (e.g., the Department of Transportation (DOT) National Transportation Atlas Database, the Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) modeling system, etc.) The EJSCREEN Technical Document explicates the existing data sources that EJSCREEN relies on.

The demographic indicators are: people of color, low income, unemployment rate, linguistic isolation, less than high school education, under age 5 and over age 64. The environmental indicators are: particulate matter 2.5, ozone, diesel particulate matter, air toxics cancer risk, air toxics respiratory hazard index, traffic proximity and volume, lead paint, Superfund proximity, risk management plan facility proximity, hazardous waste proximity, underground storage tanks and leaking UST, and wastewater discharge.

Creating the Make it in America Regional Challenge

Summary

In response to growing supply chain challenges and rising inflation, the Biden Administration should create a national competition — The Make it in America Regional Challenge (MIARC) — that activates demand in underinvested regions with cluster-based techno-economic development efforts. MIARC would be a $10 billion two phase competition that would award 30-50 regions planning grants and then 10-15 ultimate winners up to $1 billion to strengthen regional capacity in economic clusters that align with critical U.S. supply chain priorities.

Challenge and Opportunity

Roughly one in five Americans mention the high costs of living or fuel prices as the most important problem facing the United States. Meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic, global competition with China, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine has exposed significant, long-standing weaknesses in U.S. supply chains. For example, more than 40 percent of active pharmacological ingredients, 50 percent of global personal protective equipment supplies, and 90 percent of chemical ingredients for generic drugs are sourced or made in China.

This is just one small cross-section of a range of critical sectors with diffuse but at-risk supply chains globally. Offshored production in critical sectors not only induces economic loss — like the recent chip shortage which resulted in over $210 billion of foregone revenue — but places a drag on America’s ability to innovate. Indeed, America’s innovation ecosystem has lost the art of “learning-by-building”, the substantial, value-add interactions that happen when manufacturers are seated at the table with designers. The past is full of examples, including solar panels in which China-based firms have captured nearly 80 percent of market share by betting early on manufacturing innovations that precipitated a nearly 100 percent drop in PV cells’ module costs over the last 30 years.

One reason for the breakdown in supply chains is the geographic gap between where innovation and production takes place in America. Currently, there are only a handful of cities with the “industries and a solid base of human capital [to] keep attracting good employers and offering high wages … ecosystems form in these hot cities, complete with innovation companies, funding sources, highly educated workers and a strong service economy.” Increasing the capability for non-“superstar” regions to have comprehensive supply chain solutions that couple research, manufacturing, and distribution would improve these regions’ global competitiveness and drastically reduce the nation’s reliance on unstable, global supply chains. Doing so would create new jobs in distressed communities and strengthen U.S. economic independence.

The $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) launched in 2021 by the Economic Development Administration offers a recent example of how national competitions can spur both local and national economic competitiveness. The competition received 529 applications from all 50 states and will ultimately award between 20 and 30 regions up to $100 million. Representing tribal, coal, and next-generation hubs of global competitiveness, the 60 finalists each brought unique regional resources to bear including leveraging a total of $30+ billion in federal R&D investments at universities and national labs.

Final awards aside, new and extraordinary local collaborations and clusters have sprouted across these regions due to the convening power of the BBBRC. Congress and the Department of Commerce should take advantage of this nascent, in-real-time progress by creating a new national competition — The Make it in America Regional Challenge (MIARC).

If modeled after BBBRC, MIARC would restore America’s full potential to innovate, with supply chains secured by onshoring innovation and production capacities in both the heartland and coastal regions. But it would also spread bring demand to underinvested “stone cold” markets. In turn, total demand and multi-factor economic growth would skyrocket, while prices would stabilize, from the bottom up and middle out.

This approach should not be attempted in every sector. Given the serious supply chain needs, MIARC should focus on critical innovation industries where manufacturing can play a complementary role: semiconductors, high-capacity batteries, rare earth minerals, and pharmaceuticals. As described in the BBBRC Finalist Proposal Narratives, each region is uniquely positioned to support the growth of different sectors. However, public R&D funding into certain industries often generates spillover patent and citation creation in entirely different fields as well. For example, every patent generated from R&D grant funding for energy technologies yields three more patents in other sectors, suggesting a more holistic economic development strategy from targeted cluster investments.

In fact, extant academic research has described an unparalleled multiplier effect by investing in innovation sectors: “for each new high-tech job in a city, five additional jobs are ultimately created outside of the high-tech sector in that city, both in skilled occupations (lawyers, teachers, nurses) and in unskilled ones (waiters, hairdressers, carpenters).” Exemplifying this effect are America’s top 25 “most dynamic” metros, which over-index on “technology hub” cities that are beginning to spread away from Silicon Valley to previously underutilized regions as “other metros are now more capable than ever of producing the next tech company with a trillion-dollar market value.”

But successful regional innovation is a complex process, dependent on interregional spillovers of private and university knowledge, frequent face-to-face contact and knowledge-sharing between capable workforces, and sufficient resources for startups to commercialize research from labs to the marketplace. To accomplish these effects, MIARC should target investments that support a dual R&D and commercialization effort, similar to BBBRC’s cluster-building approach.

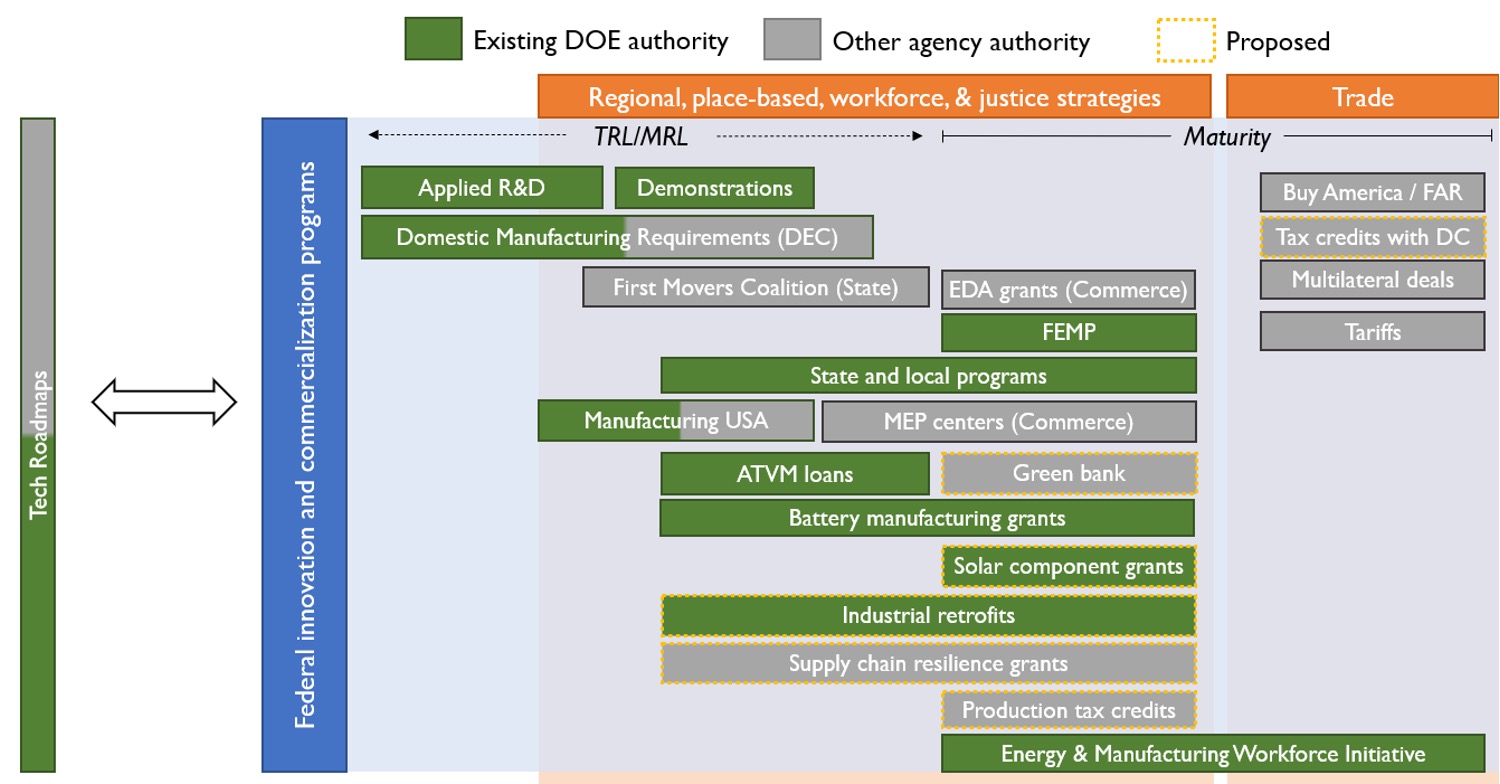

This research-commercialization funding approach would yield dividends, as the Department of Energy, National Science Foundation, and additional Department of Commerce programs are deploying a range of regional economic growth strategies. Stitching together ongoing federal resources — either through research assets such as FFRDCs and national labs, or federal research funding at universities — would multiply the effects of these collective upfront investments. For example, empirical research found that research funding investments generated two times as many startups in the proximity of a national laboratory and three times the amount of successful startups (i.e., $10+ million IPO).

In addition to BBBRC, both the Senate and House have passed different versions of legislation that calls for up to $10 billion for regional “tech hubs”, which programmatically align with the concept of the Make it in America Regional Challenge.

Plan of Action

The Make it in America Regional Challenge would be a $10 billion two phase competition that would award 30-50 regions planning grants and then 10-15 ultimate winners up to $1 billion to strengthen regional capacity in economic clusters that align with critical U.S. supply chain priorities (e.g. semiconductors, lithium batteries, etc.). Drawing from lessons from the BBB Regional Challenge, these investments would be:

- Split across multiple projects within an economic region and focused on a targeted industry or technology cluster that is critical to both regional competitiveness and U.S. economic independence.

- Based on regional supply chain needs, including investments in tailored workforce strategies, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

- Include some percentage of rural counties within the chosen geography, due to the rural-urban nature of supply chains.

In addition, any application design should allow for throughput from BBBRC applications components into MIARC Phase I applications. The existing Phase I BBBRC applicants, regardless of final award, have embarked on a herculean undertaking assembling unique regional coalitions.

In selecting additional regions, the Department of Commerce should identify the industry, the region’s related extent of intersectoral knowledge, its source (e.g., local, neighboring, or external regions), and effect on patenting. For example, recent research describes a serious difference in interregional spillover as “innovation in the chemical and electrical and electronic industries is not affected by long-distance private R&D spillovers while it is in other industries.”

Establishing Village Corps: A National Early Childhood Education (ECE) Program at AmeriCorps

Summary

While becoming a parent can bring great joy, having children can also impose an economic burden on families, reduce familial productivity in society, or cause one or more adults in a family — often mothers — to step back from their careers. In addition, many parents lack access to reliable information and resources related to childhood wellness, nutrition, and development.

As the saying goes, “It takes a village to raise a child.” But what if the metaphorical “village” was our entire nation? The momentum of the American Rescue Plan, as well as the spotlight that the COVID-19 pandemic focused on the demands of caretaking, provides the federal government an opportunity to create a new branch of its existing service corps — AmeriCorps — focused on early childhood education (ECE). This new “Village Corps” branch would train AmeriCorps members in ECE and deploy them to ECE centers across the country, thereby helping fill gaps in childcare availability and quality for working families. The main goals of Village Corps would be to:

- Alleviate the economic burden on parents by making affordable, consistent, and reliable care and education available for all children ages zero to four.

- Address the high turnover rate in ECE by leveraging AmeriCorps as a stable pipeline of ECE workers, and by coupling corps placements in ECE centers with a training program designed to grow and retain the overall ECE workforce.

- Boost the American economy by making it easier for parents with young children — particularly mothers — to stay in the workforce.

- Increase childhood health and education outcomes through high-quality early care.

Challenge and Opportunity

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the vast disparity in childcare services available for families in the United States. Our nation spends only 0.3% of GDP on childcare, lagging most other countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Put another way, average public spending on childcare for toddlers in the United States is about $500, while the OECD average is more than $14,000 (Figure 1). The problem is compounded by the lack of mandated paid family or medical leave in most states.

The Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCBG)’s Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) is the primary source of federal funding for childcare. CCDF support is intended to assist eligible families by providing subsidy vouchers for childcare. However, only one out of every nine eligible children actually receives this support, and many families who need support do not meet eligibility requirements. Furthermore, according to the National Center for Children in Poverty, the federal Early Head Start program (which includes infants and toddlers before pre-K age) serves only 3% of those eligible, leaving a major gap for families of children under the age of three.

Limited federal support for families that need childcare creates a vicious cycle. Unlike public school from kindergarten onwards, ECE and childcare facilities rely mostly on parent fees to stay open and operational. When not enough parents can afford to pay, ECE and childcare facilities will lack sufficient revenue to provide high-quality care. Indeed, the Center for American Progress found that “the true cost of licensed child care for an infant is 43 percent more than what providers can be reimbursed through the [CCDF] child care subsidy program and 42 percent more than the price programs currently charge families.” This revenue gap has resulted in a worrying hollowing of our nation’s ECE infrastructure. 51% of Americans live in an area that has few or no licensed1 childcare options. Only in high-income communities does the predominant model of parent-funded childcare provide enough high-quality ECE to meet the demand.

Underfunding has left ECE workers barely making a living wage with little to no benefits; although there has been a heavy public focus on low K–12 teacher salaries, the situation for ECE workers is worse. The average annual salary for childcare workers falls in the lowest second percentile of occupations in the United States, versus the 61st percentile for kindergarten teachers (Figure 2). Poor working conditions and compensation create high turnover in ECE, making it even harder for ECE facilities to meet demand.

Moreover, scholarship and policy initiatives designed to strengthen the training and satisfaction of the ECE workforce tend to focus on lead teachers. Such initiatives largely overlook the needs of assistant teachers/teacher’s aides, even though (i) these support personnel contribute meaningfully to classroom quality, and (ii) professional development at the aide level has been found to increase retention (Figure 3) and improve longer-term career outcomes.

These challenges merit federal intervention. Even though ECE is largely a private endeavor, high-quality and widely available early childcare and education contributes to the public good. Research shows that public investment in childcare pays for itself several times over by making it easier for parents to participate in the labor force. Additionally, spending $1 on early care and education programs has been shown to generate $8.60 in economic activity.

But it is not only the cost of childcare that is inhibitory. In 2016, two million parents made career sacrifices due to problems encountered with obtaining childcare. Mothers and single parents are especially likely to be adversely impacted by limited access to childcare. In 2020, mothers of older children remained more likely to participate in the labor force than mothers with younger children. Families are finding it increasingly difficult within the current system to find and gain access to quality childcare, leading to employment issues and an attrition of women from the workforce. Deploying a federally funded corps to fill the ECE personnel gap would stabilize ECE and childcare centers, creating a strong foundation for families and communities that will yield increased economic growth and equity. Americans have never fully benefited from a federally funded and run childcare system. It is time for the federal government and Congress to treat childcare as a public responsibility rather than a personal one

Plan of Action

Building on momentum for familial support established by the American Rescue Plan, the federal government should launch Village Corps, a new ECE-focused branch of AmeriCorps. AmeriCorps is “one of the only federal agencies tasked with elevating service and volunteerism in America.” AmeriCorps also has a long history of implementing programs in classrooms throughout the United States to “support students’ social, emotional, and academic development”, but has never had a program dedicated exclusively to training and placing Corps members in ECE. Village Corps would do just that. Participants in Village Corps would receive federally administered and/or sponsored training in fundamental aspects of high-quality ECE, including but not limited to CPR and first aid, child-abuse prevention, appropriate child and language development, classroom management, and child psychology. Village Corps members would then be placed in ECE centers across the country, providing an affordable, reliable source of infant and early childhood care for working families in the United States. Village Corps members would also have access to ongoing professional-development opportunities, enabling them to ultimately receive a Child Development Associate® (CDA) or similar tangible credential, and preparing them to pursue longer-term career opportunities in ECE.

Village Corps can be developed and deployed via the following steps:

Step 1. Establish Village Corps as a new programmatic branch of AmeriCorps.

AmeriCorps already comprises several distinct branches, including State and National, VISTA, and RSVP. Village Corps would be a new programmatic branch focused on training corps members in ECE and placing them in ECE centers nationwide. The program could start by placing corps members in Early Head Start and Head Start locations, since these are directly funded by the federal government. Piloting the program for a year at 10 sites, with five corps members per site, would require about $2 million: $1.25 million to cover salary costs, plus an additional $750,000 to subsidize living and healthcare expenses, provide an optional education credit, and account for administrative costs.

Program reach could ultimately be expanded to additional childcare centers. The federal government could even consider creating and operating a new network of ECE centers staffed predominantly or exclusively by corps members. As Village Corps develops and grows, it should prioritize placements in states, regions, and cities where a disproportionate share of the population lives in a childcare desert.

Step 2. Develop the core components of the Village Corps volunteer experience.

Recruitment and placement of Village Corps participants should follow the same general mechanisms used for other AmeriCorps divisions; however, the program should strive to place Village Corps participants in positions within their own communities. Village Corps service should be for a minimum of one year, with the option to extend to two. In addition to a modest salary, access to healthcare benefits, and a possible living stipend, Village Corps participants should receive the following benefits:

- Student loan forgiveness. There is precedent for AmeriCorps offering participants assistance with student loan debt: AmeriCorps service counts towards Public Service Loan Forgiveness and may make participants eligible for temporary loan forbearance; the Segal AmeriCorps Education Award can also be used to repay qualified student loans and/or to pay current educational expenses at eligible institutions. Expanding this precedent — at least temporarily — to provide complete student-loan forgiveness for Village Corps participants would be a compelling way to attract initial cohorts and help get the program off the ground.

- Non-Competitive Eligibility status to give Village Corps alumni a step up in the federal hiring process.

- A pathway to Child Development Associate® (CDA) credentialing. The CDA® credentialing program “is a professional development opportunity for early educators working in a variety of settings with children ages birth to 5 years old”. Earning a CDA credential yields multiple benefitsfor people interested in pursuing careers in ECE. CDA® credentials can currently be earned through a variety of pathways. AmeriCorps should work with the Council for Professional Recognition on establishing a designated pathway for Village Corps members.

- Connections to future career opportunities. Leveraging models like Grow Your Own Teachers, Village Corps should provide participants with structured avenues to translate skills and experienced acquired during their service into long-term career opportunities in their home communities. Additionally, Village Corps and its training could be utilized as a talent pipeline and pathway for upward mobility in Head Start and Early Head Start centers.

Step 3. Build a path for program funding and growth.

To start, the Biden-Harris Administration should work with the House Committee on Education and Labor and the Senate HELP Committee to see if Village Corps can be integrated into legislation like the Universal Child Care and Early Learning Act. The Administration could also consider launching Village Corps as part of the American Families Plan, and/or capitalizing on the budget reconciliation package for Build Back Better. This package is awarding $9.5 billion in grants to Head Start agencies in states that have not received payments under universal preschool programs and $2.5 billion annually for FY2022–2027 to improve compensation for Head Start staff. An additional way to make the program even more attractive would be to propose cost-matching of federal funds for Village Corps by states (if program participants are deployed in state-aided childcare centers), and/or through partnerships with key stakeholders and philanthropic organizations (e.g., Child Care Aware of America, the Child Care Network, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), and the First Five Year Fund) that have a history of supporting expansion and access to ECE. Given the downstream effects of ECE disparity in the workforce, capitalizing on the Defense Production Act could also be an avenue of support for Village Corps (see FAQ). For the longer term, the federal government could consider complementing Village Corps with a Federal Childcare and Education Savings Account (CESA) that would further subsidize childcare for families nationwide.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted gaping holes in our national early childhood care and education (ECE) fabric and has significantly exacerbated a failing system. The effects of this failure are widespread, compromising familial stability and economic security, the health, and future outcomes of American children, ECE worker retention, national productivity, and workforce participation. Establishing a new ECE-focused branch of AmeriCorps is an innovative solution to a pressing issue: a solution that builds on existing programmatic infrastructure to use talent and funds efficiently and equitably. Village Corps would create a talent pipeline for future ECE educators, boost the American workforce, and make high-quality infant and childcare easily accessible to all working families.

Current federal assistance for ECE is provided in the forms of subsidies and grants. This avenue is limited in its impact, reaching only 1 in 9 eligible families. Moreover, licensed childcare in many instances costs 43% more than what providers are eligible to be reimbursed for through federal childcare subsidies, and 42% more than what providers can sustainably charge families. This disparity between subsidized and actual costs has created a system that underpays ECE providers, resulting in lower-quality childcare and scarce availability of childcare slots for subsidy-eligible families. Additionally, because even federally subsidized ECE centers rely heavily on fees collected by families, they are at higher risk of closure during difficult times (such as the COVID-19 pandemic) than educational facilities (e.g., K–12 schools) that are fully federally funded.

The federal government could try to remedy these issues through a massive infusion of cash into childcare subsidy programs. But a national-service-oriented approach — i.e., working through AmeriCorps to direct additional human capital to ECE — is a creative and potentially more cost-efficient strategy that is worth trying.

The first suite of Village Corps participants will be placed at existing Early Head Start Centers, which must adhere to a strict set of performance standards. In later years, Village Corps could partner with state agencies or NGOs and philanthropic organizations that support ECE centers in areas characterized by childcare deserts.

Not directly, but it has been shown that teachers and caregivers who work in publicly funded settings earn higher wages than those in non-publicly funded settings. Hence it is reasonable to expect that public funding for ECE will translate into higher salaries for ECE workers.

AmeriCorps currently has seven sub-programs through which it disseminates volunteers; Village Corps would become the eighth. As a sub-program of AmeriCorps, Village Corps participants would have to undergo the general AmeriCorps application process to be selected to serve. In addition, Village Corps should look for the following traits in its applicants:

- Coachable

- Accountable

- Problem solver and critical thinker

- Takes initiative and possess leadership qualities

- Resilient

- Adaptive

- Excels in a fast paced/challenging environment

- Team player

5. What is an alternative support mechanism for Village Corps?

A lack of quality ECE options has a dramatic effect on workforce participation. The market failure of undersupplied ECE options decreases economic productivity. Village Corps would address some of these market failures by stabilizing the ECE workforce and fulfilling the labor requirements for high-quality ECE centers, thereby enabling families to increase workforce participation and economic productivity. Increased workforce participation is especially important for helping the United States remain globally competitive in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields. 40% of women and 23% of men in full-time STEM jobs leave or switch to part-time work after their first child. Taken together, these facts make a compelling case for using the Defense Production Act to support Village Corps.

There is precedent for the government utilizing funds in this manner. During World War II, large-scale entry of women into the workforce created sudden and pressing demands for childcare. Congress responded by passing the Defense Housing and Community Facilities and Services Act of 1940, also known as the Lanham Act. The law funded public works — including childcare facilities — in communities that had defense industries. About 3,000 federally subsidized and run Lanham centers ultimately provided childcare for up to six days a week and certain holidays. Parents only paid the equivalent today of $10/day for care.

Establishing a National Endemic Disease Surveillance Initiative (NEDSI)

Summary

Global pandemics cause major human and financial losses. Our nation has suffered nearly a million deaths associated with COVID-19 to date. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that COVID-19 will cost the United States $7.6 trillion in lost economic output over the next decade. While much has rightly been written on preventing the next pandemic, far less attention has been paid to mitigating the compounding effects of endemic diseases. Endemic diseases are consistently present over time and typically restricted to a defined geographic region. Such diseases can exacerbate pandemic-associated financial losses, complicate patient care, and delay patient recovery. In a clinical context, endemic diseases can worsen existing infections and compromise patient outcomes. For example, co-infections with endemic diseases increase the likelihood of patient mortality from pandemic diseases like COVID-19 and H1N1 influenza.

Accurate and timely data on the prevalence of endemic diseases enables public-health officials to minimize the above-cited burdens through proactive response. Yet the U.S. government does not mandate reporting and/or monitoring of many endemic diseases. The Biden-Harris administration should use American Rescue Plan funds to establish a National Endemic Disease Surveillance Initiative (NEDSI), within the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS), to remove barriers to monitoring endemic, infectious diseases and to incentivize reporting. The NEDSI will support the goals of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Data Modernization Initiative by providing robust infection data on a typically overlooked suite of diseases in the United States. Specifically, the NEDSI will:

- Provide healthcare practitioners with resources to implement/upgrade digital disease reporting.

- Support effective allocation of funding to hospitals, clinics, and healthcare providers in regions with severe endemic disease.

- Prepare quarterly memos updating healthcare providers about endemic disease prevalence and spread.

- Alert citizens and health-care practitioners in real time of notable infections and disease outbreaks.

- Track and predict endemic-disease burden, enabling strategic-intervention planning within the CDC and with partner entities.

Challenge and Opportunity

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for a multilevel approach to addressing endemic diseases. Endemic diseases are defined as those that persist at relatively stable case numbers within a defined geographic region. Though endemic diseases are typically geographically restricted, changes in population movement, population behaviors, and environmental conditions are increasing the incidence of endemic diseases. For example, Valley fever, a fungal respiratory disease endemic to the California Central Valley and the American Southwest, is predicted to spread to the American Midwest by 2060 due to climate change.

Better preparing the United States for future pandemics depends partly on better countering endemic disease. Effective patient care during a pandemic requires clinicians to treat not only the primary infection, but also potential secondary infections arising from endemic pathogens taking advantage of a weakened, preoccupied host immune system. Though typically not dangerous on their own, secondary infections from even common fungi such as Aspergillus or Candida can become deadly if the host is pre-infected with a respiratory virus. On the individual level, secondary infections with endemic diseases adversely impact patient recovery and survival rates. On the state level, secondary infections impose major healthcare costs by prolonging patient recovery and increasing medical intervention needs. And on the national level, poor endemic-disease management in one state can cause disease persistence and spread to other states.

Robust surveillance is integral to endemic-disease management. The case of endemic schistosomiasis in the Sichuan province of China illustrates the point. Though the province successfully controlled the disease initially, decreased funding for disease tracking and management—and hence lack of awareness and apathy among stakeholders—caused the disease to re-emerge and case numbers to grow. During active endemic-disease outbreaks, comprehensive data improves decision-making by reflecting the real-time state of infections. In between outbreaks, high-quality surveillance data enables more accurate prediction and thus timely, life-saving intervention. Yet the U.S. government mandates reporting and/or monitoring of relatively few endemic diseases.

Part of the problem is that improvements are needed in our national infrastructure for tracking and reporting diseases of concern. Approximately 95% of all hospitals within the United States use some form of electronic health record (EHR) keeping, but not all hospitals have the same resources to maintain or use EHR systems. For example, rural hospitals generally have poorer capacity to send, receive, find, and integrate patient-care reports. This results in drastic variation in case-reporting quality across the United States: and hence drastic variation in availability of the standardized, accurate data that policy and decision makers need to maximize public health.

With these issues in mind, the Biden-Harris administration should use American Rescue Plan (ARP) funds to establish a National Endemic Disease Surveillance Initiative (NEDSI) within the CDC’s National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS). Fighting an individual pandemic disease is difficult enough. We need better systems to stop endemic diseases from making the battle worse. Implementing NEDSI will equip decision makers with the data they need to respond to real-time needs— thereby protecting our nation’s economy and, more importantly, our people’s lives.

Plan of Action

To build NEDSI, the CDC should use a portion of the $500 million allocated in the ARP to strengthen surveillance and analytic infrastructure and build infectious-disease forecasting systems. NEDSI will support the goals of the CDC’s Data Modernization Initiative by allocating resources to implement and/or upgrade digital-disease reporting capabilities needed to obtain robust infection data on endemic diseases. Specifically, NEDSI would strive to minimize healthcare burdens of endemic diseases through the following four actions:

- Disease monitoring. NEDSI will identify and track notable endemic infectious diseases for each state, including but not exclusive to (i) existing infectious diseases with historical presence and/or relevance, and (ii) infectious diseases that disproportionately impact particular workers. For example, Valley fever disproportionately impacts those employed in outdoor occupations related to ground/soil work (such as agricultural workers, solar farmers, construction workers, etc.). Endemic-disease reporting under NEDSI will follow reporting templates and frameworks that have already been developed by the NNDSS, but will also include information on co-infections (i.e., whether a reported endemic-disease case was a primary, secondary, or higher-order infection).

- Disease notification. As part of monitoring, case-report numbers that rise above historical norms will be automatically flagged for alerts to community members, health-care providers, public-health officials, and other stakeholders.

- Alerts to community members will be geotargeted (for example, by city, county, or region), enabling residents and travelers in endemic zones to take precautions. Alerts will be text-message-based and include resource links vetted by public-health experts.

- Alerts to health-care providers will contain links to resources providing the latest information on accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment of the disease in question. This will allow providers to quickly identify emerging cases of the disease, as well as to prepare for above-average use/need of particular treatments and equipment.

- Alerts to public-health officials will help shape recommendations for travel restrictions, emergency-funding requests and allocations, and rapid-response resources.

- Disease prediction. NEDSI will work with the CDC and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to build an endemic-disease prediction model that ranks the severity of current and anticipated endemic-disease burden by geographic region in the United States, enabling proactive intervention against emerging threats.

- Model insights will be shared with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and state health departments to inform allocation of funds (e.g., from the federal-to-state and state-to-county levels) to support public health.

- Key model insights could also be posted on the CDC’s website and transmitted in notices to regional public-health officials and healthcare practitioners, especially when predicted risks and infection trends are high.

- Data underlying the model should be made publicly available and accessible to support external disease-modeling and -prediction efforts.

- In alignment with priorities of the Data Modernization Initiative and the American Pandemic Preparedness Plan, the CDC could also consider offering financial assistance (e.g., through grants or cooperative agreements) to external research efforts conducted in partnership with NEDSI and/or using NEDSI data. NEDSI and NNDSS should work to identify key research targets and promote them appropriately in Notices of Funding Opportunities.

- Health education. The NNDSS, utilizing data and model outputs from NEDSI, should prepare quarterly memos synthesizing key information related to endemic diseases in the United States, including (i) summary statistics of endemic-disease case numbers and co-infections by state and county; (ii) an up-to-date list of available treatments, medications, and therapies for different endemic diseases, and (iii) predicted disease trends for coming months and years. Memos should be published digitally and archived on the CDC website. Publication of each memo should be accompanied by a digital campaign to help spread the resource to healthcare practitioners, public-health authorities, and other stakeholders. NEDSI representatives should also prioritize participation in disease-specific research/clinical conferences to ensure that the latest scientific findings and developments are reflected in the memos.

Conclusion

Despite the clear burdens that endemic diseases impose, such diseases are still largely understudied and poorly understood. Until we have better knowledge of immunology related to endemic-disease co-infections, our best “treatment” is robust surveillance of opportunistic co-infections—surveillance that will enable proactive steps to minimize endemic-disease impacts on already vulnerable populations. Establishing a National Endemic Disease Surveillance Initiative within the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System will close a critical gap in our nation’s disease-monitoring and -reporting infrastructure, helping reduce healthcare burdens while strengthening pandemic preparedness.

NEDSI, like other systems standardizing and streamlining disease reporting, will allow healthcare practitioners to efficiently—and in some cases, automatically—share data on endemic diseases. Such real-time, consistent data are invaluable for informing public-health responses as well as future emergency planning.

An ounce of endemic-disease prevention is worth far more than a pound of cure—and effective prevention depends on effective monitoring. Research shows that endemic diseases account for an alarming number of co-infections with COVID-19. These co-infections have detrimental impacts on patient outcomes. Further, population growth and migration trends are increasing transmission of and exposure to endemic diseases. Mitigating the severity of future epidemics and pandemics hence requires near-term investment in endemic-disease monitoring.

Yes: even in non-pandemic times, co-infections represent a major risk for the immunocompromised and elderly. AIDS patients succumb to secondary infections as a direct result of becoming immunocompromised by their primary HIV infection. Annual flu seasons are worsened by opportunistic co-infections. Monitoring and tracking endemic diseases and their co-infection rates will help mitigate existing healthcare burdens even outside the scope of a pandemic.

Due to a combination of funding challenges and lack of research progress/understanding, endemic-disease monitoring was only recently identified as a crucial gap in overall infectious disease preparedness. But now, with allocated funds from the American Rescue Plan to strengthen surveillance and infectious-disease forecasting systems, there is a historic opportunity to invest in this important area

Taking Out the Space Trash: Creating an Advanced Market Commitment for Recycling and Removing Large-Scale Space Debris

Summary

In the coming decades, the United States’ space industry stands to grow into one of the country’s most significant civil, defense, and commercial infrastructure providers. However, this nearly $500 billion market is threatened by a growing problem: space trash. Nonoperational satellites and other large-scale debris items have accumulated in space for decades as a kind of celestial junkyard, posing a serious security risk to future business endeavors. When companies launch new satellites needed for GPS, internet services, and military operations into Earth’s lower orbit, they risk colliding with dead equipment in the ever-crowding atmosphere. While the last major satellite collision was over a decade ago, it is only a matter of time until the next occurs. As space traffic density increases, scientists project that collisions (and loss of satellite-based services as a result) will become progressively problematic and frequent.

Due to the speed of innovation within the space industry, the rate of space commercialization is outpacing the federal government’s regulatory paradigms. Therefore, the U.S. government should give businesses the means to resolve the space debris problem directly. To do so, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the U.S. Space Force, and the Department of Commerce (DOC) should create an advanced market commitment for recycling and de-orbiting satellites and large-sized debris. By incentivizing businesses with financial stimulus, novel regulation, and sustained market ecosystems, the federal government can mitigate the space debris problem in a way that also bolsters national economic growth.

Challenge and Opportunity

The sustainability and security of Earth’s outer orbit and the future success of launch missions depend on the removal of sixty years’ worth of accumulated space debris. The space debris population in the lower-Earth orbit (LEO) region has reached the point where the environment is considered unstable. Over 8,000 metric tons of dead, human-deposited objects orbit the planet, including over 13,000 defunct satellites. While this accumulated trash is the product of numerous countries’ space activities, the United States is an undeniably large contributor to the problem. Approximately 30% of orbiting, functional satellites belong to the United States. As such, we as a nation have a responsibility to tackle the space debris challenge head-on.

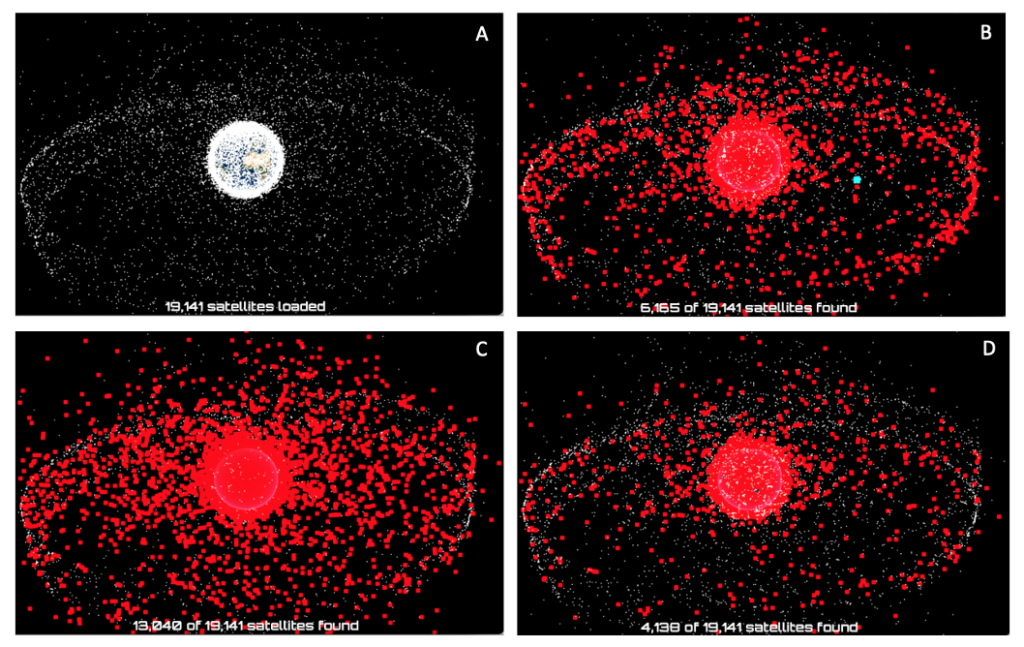

Space is becoming littered with dead satellites, and the United States is a major contributor. Over 19,000 satellites have been launched between 1950 and 2020 and currently orbit the Earth (Tile A). The red dots in Tile B above represent the satellites, both dead and active, owned and launched by the United States. Nearly 70% of all satellites in orbit are classified as “junk” (Tile C). The United States is one of the largest contributors of satellite refuse, second only to Russia (4,138 satellites vs. 4,714; Tile D). (Source: Generated using ESRI satellite data)

Our nation’s responsibility is especially acute since rapid growth in the American commercial space sector is likely to further exacerbate the space debris problem. New technology advancements mean that it is cheaper than ever to manufacture and launch new satellites. Additionally, recent improvements in rocket engineering and design provide more economical options for getting payloads into space. This changing cost environment means that the space industry is no longer monopolized by a select number of large, multinational companies. Instead, smaller businesses now face fewer barriers-to-entry for satellite deployment and have an equal opportunity to compete in the market. However, since space debris management is not yet fully regulated, this increased commercial activity means that more industries may be littering LEO in the near future.

America’s mounting demand for satellite-based services will congest LEO’s already crowded environment even further. The U.S. defense sector in particular requires further space resources due to their reliance on sophisticated communication and image-capturing capabilities. As a result, the Department of Defense (DOD) has started recruiting space industries to provide these services through increased satellite deployment in LEO. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has boosted consumer demand for satellite-based internet. In response, space industries are racing to extend broadband access to rural areas and remote populations, an effort which the Biden Administration hopes to support through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal. Overall, this combined demand for commercial satellite services from the American public and federal government means that more launches will occur in the years ahead and add to the ongoing debris issue.

The worsening congestion in outer space is a severe nuisance for America’s space industry. Floating trash in LEO creates an immediate physical barrier to commercial space activity. Rocket launches and payload delivery must first chart a safe flight that avoids collision with pre-orbiting objects, which, given the growing congestion in LEO, will only become more difficult in the future.

The space debris issue is also a serious security risk that may one day end in disaster. If space traffic becomes too dense, a single collision between two large objects could produce a cloud of thousands of small-scale debris. These fragments could, in turn, act as lethal missiles that hit other objects in orbit, thereby causing even more collisional debris. This cascade of destruction, known as the Kessler Syndrome, ultimately results in a scenario where LEO is saturated with uncontrollable projectiles that render further space launch, exploration, and development impossible. The financial, industrial, and societal consequences of this situation would be devastating.

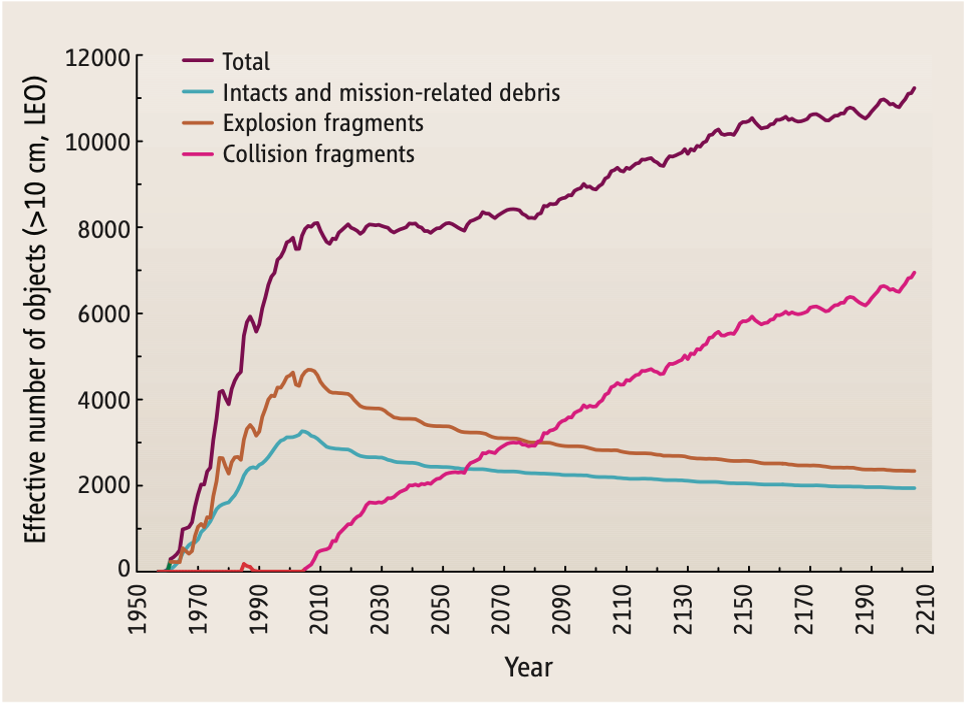

Space debris, especially debris resulting from collisions, is projected to grow significantly in the years ahead. Lines in this figure represent the number of trackable low-Earth orbit (LEO) objects (based on a NASA-based mathematical simulation). The blue line represents rocket bodies, spacecrafts, and other launch-related refuse that have not experienced breakups. The brown line represents debris resulting from explosions, which are caused by internal malfunctions of a given piece of equipment. The pink line represents debris resulting from two or more objects colliding with one another in orbit. (Source: Science Magazine)

If outer space is to remain a viable environment for development and industry, the space debris problem must be solved. NASA and other space agencies have shown that at least five to ten of the most massive debris objects must be removed each year to prevent space debris accumulation from getting out of hand. Orbital decay from atmospheric drag, the only natural space clean-up process, is insufficient for removing large-sized debris. In fact, orbital decay could compound problems posed by massive debris objects as surface erosion may cause wakes of smaller debris cast-offs. Therefore, cleanup and removal of massive debris objects must be done manually.

According to the National Space Policy, the U.S. government can “develop governmental space systems only when it is in the national interest and there is no suitable, cost-effective U.S. commercial or, as appropriate, foreign commercial service or system that is or will be available.” As such, any future U.S. space cleanup program must actively involve the space industry sector to be successful. Such a program must create an environment where space debris removal is a competitive economic opportunity rather than an obligation.

Presently, an industrial sector focused on space debris removal and recycling—including on-site satellite servicing, in-orbit equipment repair and satellite life extensions, satellite end-of-life services, and active debris removal—remains nascent at best. However, the potential and importance of this sector is becoming increasingly evident. The U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s Robotic Servicing of Geosynchronous Satellites program seeks to cheaply recycle still-functioning pieces of defunct satellites and incorporate them into new space systems. Northrop Grumman, an American multinational aerospace and defense-technology company, as well as a number of other small and medium-sized U.S. businesses, have ongoing projects to build in-orbit recycling systems to reduce the costs and risks of new satellite launches. However, federal intervention is needed to rapidly stimulate further growth in this sector and to address the following challenges:

- The cost of active space debris removal, satellite decommissioning and recycling, and other cleanup activities is largely unknown, which dissuades novel business ventures.

- Space law can be convoluted and the right to access satellites and own or reuse recycled material is contentious. To generate a successful large-scale debris mitigation economy, business norms and regulations need to be further defined with safety nets in place.

- The large debris objects that pose the greatest collision risks need to be prioritized for decommission. These objects have not yet been identified, nor has their cleanup been prioritized.

Plan of Action

To address the aforementioned challenges, multiple offices within the federal government will need to coordinate and support the American space industry. Specifically, they will need to create an advanced market commitment for space debris removal and recycling, using financial incentives and new regulatory mechanisms to support this emerging market. To achieve this goal, we recommend the following five policy steps:

Recommendation 1. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) should collaborate to provide U.S. space industries with a standard means of identifying which satellites are viable for recycling once they have reached the end of their life cycle.

One reason why the satellite and large debris object recycling and removal industry remains small is because the market is small. The market can be grown by creating a verified system for satellite providers and operators to indicate that their equipment can be recycled or decommissioned by secondary service providers once a mission is completed. To encourage widespread use of this elective registration system, it will need to be incentivized and incorporated into ongoing satellite and rocket regulatory schemes.

Because federal authority over space activity has evolved over time, multiple federal agencies currently regulate the commercial space industry. The FCC licenses commercial satellite communications, the FAA licenses commercial launch and reentry vehicles (i.e., rockets and spaceplanes) as well as commercial spaceports, and NOAA licenses commercial Earth remote-sensing satellites. These agencies must collaborate to develop a standard and centralized registration system that promotes satellite recycling.

Industries will need incentives for opting into this registration system and for marking their equipment as recyclable and decommission-viable. With respect to the former, the recycling registration mechanism should be incorporated into federal pre-launch or pre-licensing protocols. With respect to the latter, the FCC, the FAA, and NOAA could:

- Coordinate with satellite and space insurance industries to offer reduced premiums to those who elect into the registration system.

- Coordinate with satellite and space insurance industries to offer a subsidy for in-orbit satellites that retroactively enroll.

- Offer prioritized licensing or expedited payload launch to registered satellites and rockets.

Recommendation 2. NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office (ODPO), in coordination with the DOD’s Space Surveillance Network, should create a prioritized list of massive space debris items in LEO for expedited cleanup.

Rocket bodies, nonfunctioning satellites, and other large debris represent the highest percentage of overall orbital debris mass in LEO. Since these objects pose the highest risks of additional debris generation through collisions and decay, reducing their stay in LEO is a priority. However, given the continuous generation of space debris and sometimes uncertain or tenuous ownership of older debris items, the federal government needs to create a public and regularly updated “large-debris criticality” index. This index would give large debris items a risk-assessment score based on (i) their ability to generate additional debris through erosion or collision, (ii) the feasibility of their removal, (iii) their ownership status, and (iv) other risk factors. Objects that were put into orbit before NASA ODPO issued its standard debris mitigation guidelines need to be assessed retroactively.

By creating and regularly updating this public index, the federal government would make it easier for public and private actors alike to identify which debris items need to be prioritized for cleanup, what risks are involved, and what technology may be required for successful removal.

Recommendation 3. The Space Force, in collaboration with the Department of Commerce (DOC), should fund removal and/or recycling of a set number of large debris objects each year, thereby creating a reliable market for space debris removal.

By committing to fully or partially fund the NASA-recommended removal of five to ten large debris items each year, the Space Force and the DOC would lower the risk of business entry into the orbital debris removal market and create a sustained market economy for space debris mitigation. The specific monetary reward offered by these agencies for debris removal could be commensurate with the nature and size of the debris item, the speed of removal, and the manner of removal. An additional payout could be offered for the removal of a high-priority large debris item (e.g., an item identified in Recommendation 2 above), or for debris removal that is done sustainably (e.g., in ways that recycle or reuse parts and do not generate secondary, smaller debris).

Recommendation 4. The Space Force – Space Systems Command should coordinate with NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer (SBIR/STTR) program to issue a satellite design-based grand challenge aimed at facilitating future satellite recycling efforts.

Grand challenges are popular and often effective tools for stimulating public interest in a given issue and advancing technologies. However, they can fall short of creating a sustainable, long-lasting commercial industry. The Space Force and NASA can overcome this difficulty by designing a grand challenge wherein: (i) research and development costs are shared among private and public participants; (ii) multiple winners are selected at the end of the challenge; (iii) winners are chosen based on whether they meet government capability thresholds in addition to being commercially viable; and (iv) challenge winners are guaranteed a long-term government service contract.

For this grand challenge, Space Force and NASA should encourage the creation and, afterwards, widespread commercial use of satellite design strategies that facilitate satellite recycling, mission extension, or deconstruction. Specifically, the design challenge should focus on:

- Providing enhanced protection against mission-ending impacts by small orbital debris.

- Generating standardized features (e.g., docking mechanisms) that allow future servicing equipment to latch in orbit for repair, deconstruction, and recycling.

- Crafting modular and scalable components that can be easily swapped out, removed, and replaced and thereby lead to downstream recycling and repair.

Recommendation 5. NOAA’s Office of Space Commerce, in conjunction with the Space Force and NASA’s ODPO, should jointly issue an annual research report outlining risk, cost-benefit analyses, and the economics of orbital debris removal and recycling.

For the growing number of debris recycling and satellite maintenance industries, large orbital debris represent a potential source of valuable materials and resources. While it is theorized that repurposing or salvaging these large debris objects may be more cost effective than de-orbiting them, exact costs and benefits are often unspecified. Additionally, the financial repercussions of accumulating space debris and collisions are largely unknown.

If industries know the upfront expenses and potential profit of space debris removal, the debris removal market will be far less risky and more lucrative. NASA, NOAA, and the Space Force can fill that information gap by collaboratively creating better tools to assess both the risk and costs posed by orbital debris to future uses of space, including commercial development and investment.

Conclusion

For America’s space industry to grow to its full potential, end-of-life satellites and other orbiting dead equipment need to be cleared from Earth’s lower orbit. Without removing these items, the increasing possibility of a severe in-orbit collision poses a major security risk to civilian, military, and commercial infrastructure providers. By creating an advanced market commitment for recycling and de-orbiting large-sized debris items, the federal government does more than just address the growing space debris problem. It also creates a new market for the U.S. space industry and stimulates further economic growth for the country. Additionally, it encourages greater public-private collaboration as well as consistent communication between crucial offices within the U.S. government.

Global space governance is very complicated since no single country has a right to this territory. As such, space activity is broadly guided by UN treaties such as the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 and the Moon Agreement of 1979. While these treaties establish important guidelines for the peaceful use of space, they fail to address important present-day concerns, such as governing space debris and private industry activity. Thus, these treaties are not fully able to guide modern challenges in space commercialization. It is also important to note that it took nearly ten years for diplomats to reach an agreement and ratify these treaties. Therefore, the timeline needed to either revisit outer space treaties or craft new ones is too slow to fully match the breakneck speed at which space activity is developing today. Given the U.S. space industry’s influential role in shaping behaviors and norms in outer space, addressing the space debris problem effectively will require the U.S. space industry sector’s involvement.

In 2018, the FAA estimated the value of the U.S. space industry at approximately $158 billion. Since then, the space economy has continued to grow, largely due to a record period of private investment and new investor opportunities in spaceflight, satellite, and other space-related companies. As a result, the space industry was valued at $424 billion in 2019. By 2030, it is believed that the space industry will be one of the most valuable sectors of the U.S. economy, with a projected value of between $1.5 and $3 trillion.

It all has to do with cost. Mounting competition among private space companies means it is cheaper than ever to launch equipment into space, which creates numerous opportunities for businesses to meet the ever-increasing need for alternative supply chain routes and satellite-based internet connectivity.

From 1970–2000, the cost of launching a kilogram of material into space remained fairly steady and was determined primarily by NASA. When NASA’s space shuttle fleet was in operation, it could launch a payload of 27,500 kilograms for $1.5 billion($54,500 per kilogram). Today, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket advertises a cost of just $62 million to launch 22,800 kilograms ($2,720 per kilogram). In other words, commercial launch has reduced the cost of getting a satellite into LEO by a factor of 20. Additional developments in reusable rocket technology may decrease that cost to just $5 million in the future. Improvements in satellite technology and mass production will further cut costs and make more launches possible. It is projected that satellite mass production techniques could decrease launch cost from $500 million per satellite to $500,000.

Decreasing costs lead to increasing rocket and satellite launch rates and, hence, to increasing accumulation of space debris.

If the satellites in question are active, fully functioning, and capable of maneuvering, then to an extent—yes. Satellites can be remotely programmed to change course and avoid a collision. Even under these circumstances, though, these objects adhere to the laws of physics; it can take a lot of energy to alter their orbit to avoid a crash. As such, most satellite operators require hours or days to plan and execute a collision avoidance maneuver.

Not all active equipment is capable of maneuvering, though; there is no way to control objects that are inactive or dead. So, orbiting debris are uncontrollable.

To date, there is no official or internationally recognized “Space Traffic Control” agency. Within the U.S., responsibility for space traffic surveillance is shared among numerous government agencies and even some companies.

Satellites and rockets are not designed for disposal; they’re designed to withstand the tremendous aerodynamic forces, heat, drag, etc. experienced when exiting the Earth’s atmosphere. Furthermore, many satellites are built with reinforcements to maintain orbit and withstand minor collisions with space debris. Hence, breaking down, recycling, and fixing satellites in space is currently very challenging.

LEO is defined as the area close to Earth’s surface (between 160 and 1,000 km). This territory is especially viable for satellites for several reasons. First, the close distance to Earth means that it takes less fuel to station satellites in orbit, making LEO one of the cheapest options for space industries. Second, LEO satellites do not always have to follow a strict path around Earth’s equator; they can instead follow tilted and angled orbital paths. This means there are more available flight routes for satellites in LEO, making it an attractive territory for space industries. As a result, most satellites and, by consequence, the majority of satellite junk is located in LEO. (See first image in Challenge and Opportunity of littered satellites).

Smaller debris do outnumber larger debris in outer space. According to NASA, there are approximately 23,000 pieces of debris larger than a softball orbiting the Earth. There are 500,000 pieces of debris the size of a marble (up to 0.4 inches, or 1 centimeter), and approximately 100 million pieces of debris that are about .04 inches (or 1 millimeter) and larger. Micrometer-sized (0.000039 of an inch in diameter) debris are even more abundant. These small-sized space debris may be traveling upwards of 17,500 mph, meaning they can do massive amounts of damage during collisions.

Clearly (see image below), small debris are also a significant security risk and should be included in space debris cleanup considerations. However, an inability to track small-scale debris orbits, the specific challenges in “catching” these small, high velocity objects, and a significant lack of reliable information on small-sized space debris means that this aspect of space debris mitigation will likely require its own unique policy actions.

We presently have more data on large-sized debris, and these items pose the greatest threat to ongoing space efforts, should they collide. Therefore, this memo focuses on policy actions targeting these debris items first.

Regulating Probiotic Use and Improving Veterinary Care to Bolster Honeybee Health

This memo is part of the Day One Project Early Career Science Policy Accelerator, a joint initiative between the Federation of American Scientists & the National Science Policy Network.

Summary

One-third of the food Americans eat comes from honeybee-pollinated crops. Honeybees used for commercial pollination operations are routinely treated with antibiotics as a preventative measure against bacterial infections. Pre- and probiotics are marketed to beekeepers to help restore honeybee gut health and improve overall immune function. However, there is little to no federal oversight of these supplements. Apiculture supplements currently on the market are expensive but often ineffective. This leaves unaware farmers wasting money on “snake oil” products while honeybee colonies remain weakened — threatening not just the U.S. agricultural economy, but also the livelihoods of beekeepers and farmers. At the same time, widespread use of antibiotics in apiculture puts honeybees at high risk of spreading antibiotic resistance.

To address these issues, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s Office of Human and Animal Food Operations and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s National Institute for Food and Agriculture (NIFA) should work together to (1) create an FDA review and approval process for pre- and probiotic apiculture products, (2) design educational programs designed to educate veterinarians on best practices for beekeeping health and husbandry, and (3) offer grants to help farmers and apiculturists access high-quality veterinary care for honeybee colonies.

Challenge and Opportunity

Honeybee pollination services are pivotal to the U.S. agricultural economy. It is estimated that about one-third of the food Americans eat comes from crops pollinated by honeybees. Throughout the past decade, beekeepers have suffered colony losses that make commercial apiculture challenging. These colony losses are caused by complex and interconnected issues including the rise of honeybee diseases such as bacterial infections like American Foulbrood or viral infections linked to pests like the Varroa mite, a general increase in hive pests, habitat fragmentation and nutrition loss, and increased use of pesticides and/or pesticide exposure.

The substantial threats posed by bacterial and viral diseases to honeybee colonies have driven commercial beekeeping operations to routinely treat their hives with antibiotics (mainly oxytetracycline). Unfortunately, antibiotic treatment can also (i) compromise honeybee health by wiping out beneficial bacteria in the honeybee microbiome, and (ii) promote antibiotic resistance. Routine use of antibiotics in apiculture hence compounds the challenges mentioned above and further compromises the livelihoods of U.S. farmers and the security of U.S. food systems.

In 2017, the FDA responded to antibiotic overuse in apiculture by amending the Veterinary Feed Directive (VFD) section of the Animal Drug Availability Act of 1996 (ADAA). The 2017 amendment required beekeepers to obtain veterinary approval to treat their colonies with antibiotics against certain diseases. While attractive on paper, the implementation of this policy has encountered challenges in practice. Finding a vet who understands the highly complex dynamics of apiculture has been a substantial challenge for commercial beekeepers, especially in rural areas. Improvements to the implementation of the VFD are needed to contain the spread of antibiotic resistance in apiculture.