Pandemic Readiness Requires Bold Federal Financing for Vaccines

Summary

Most people will experience a severe pandemic within their lifetime, and the world remains dangerously unprepared. In fact, scientists predict a nearly 50% chance––the same probability as flipping heads or tails on a coin––that we will endure another COVID-19-level pandemic within the next 25 years. Shifting America’s pandemic response capability from reactive to proactive is, therefore, urgent. Failure to do so risks the country’s welfare.

Getting ahead of the next pandemic is impossible without government financing. Vaccine production is costly, and these expenses will hinder industries from preemptively developing the tools needed to halt disease transmission. For example, the total expected revenues over a 20-year vaccine patent lifecycle would cover just half of the upfront research and development (R&D) costs.

However, research suggests that a portfolio-based approach to vaccine development — especially now with new, broadly applicable mRNA technology — dramatically increases the returns on investment while also guarding against an estimated 31 of the next 45 epidemic outbreaks. With lessons learned from Operation Warp Speed, Congress can deploy this approach by (i) authorizing and appropriating $10 billion to the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) (ii) developing a vaccine portfolio for 10 emerging infectious diseases (EIDs), and (iii) a White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP)-led interagency effort focused on scaling up production of priority vaccines.

Challenge & Opportunity

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to wreak havoc across the world, with an ongoing total cost of $16 trillion and more than 6 million dead. Three conditions increase the likelihood that we will experience another pandemic that is just as disastrous:

- New outbreaks of infectious diseases––like ––are emerging due to population growth, increased zoonotic transmission from animals, habitat loss, climate change, and more. Over 1.6 million yet-to-be-discovered, human-infecting viral species are thought to exist in mammals and birds.

- More laboratories are handling dangerous pathogens around the world, which increases the likelihood of an accidental contagion release.

- It is easier than ever to purchase biotechnologies once reserved only for scientists. Consequently, malign actors now have more resources to develop a human-engineered bioweapon.

The United States and the rest of the world are still woefully unprepared for future pandemic or epidemic threats. The lack of progress is largely due to little to no vaccine development for these six EIDs, all of which have pandemic potential:

- Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)

- Lassa fever virus

- Nipah virus

- Rift Valley fever virus

- Chikungunya virus

- Ebola virus

Failure to produce and supply vaccines doses to Americans could undermine the U.S. government’s response to a vaccine crisis. This is illustrated in the recent monkeypox response. The federal government invested in a new monkeypox vaccine with a significantly longer shelf life. While focused on this effort, it failed to replace its existing vaccine stockpile as it expired, leaving the American population woefully unprepared during the recent monkeypox outbreak.

An immediate national strategy is needed to course correct, the beginnings of which are articulated in the recent plan for American Pandemic Preparedness: Transforming our Capabilities. These overarching concerns were also echoed in a bipartisan letter from the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions and Armed Services Committees, urging the Biden Administration to re-establish a “2.0” version of Operation Warp Speed (OWS)––the government’s prior effort to accelerate COVID-19 vaccine production.

The President’s recent FY23 Budget advocates for a historic pandemic preparedness investment. The plan allocates nearly $40 billion to the Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response to “invest in advanced development and manufacturing of countermeasures for high priority threats and viral families, including vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and personal protective equipment.” BARDA also declared the need to prepare prototype vaccines for virus families with pandemic potential and has included such investments in its most recent strategic plan. And, the recent calls for increased “piloting and prototyping efforts in biotechnology and biomanufacturing to accelerate the translation of basic research results into practice.”

Robust federal investment in America’s vaccine industry is especially needed since––as demonstrated by COVID-19––industries garner minimal profit from vaccine development before or during a widespread outbreak. A recent study predicted that in the unlikely scenario where 10 million vaccines are manufactured during a crisis response, pharmaceutical companies can expect to recoup only half of the upfront R&D costs. The same research states that “new drug development has become slower, more expensive, and less likely to succeed” because:

- The probability of developing a successful vaccine candidate is low.

- A lengthy investment time (i.e., a long investment horizon) is required before selling for profit is possible.

- Clinical trials are very expensive.

- To justify and overcome all costs, a high financial return is needed (i.e., there is a high cost of capital).

With clinical costs accounting for 96% of total investment, companies have a weak financial justification for investing in risky vaccine research.

To minimize these uncertainties and improve investment returns for vaccine and therapeutic production, the federal government should embrace two key lessons from OWS:

- Guaranteed government demand enables the pursuit of innovative, speedy, and effective vaccine R&D. OWS selected companies pursuing different scientific methods to develop a vaccine, each of which possessed breakthrough potential. Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech utilized mRNA, AstraZeneca and Janssen worked with replication-defective live vectors, and Novavax and Sanofi/GSK utilized a recombinant protein. Merck is working on a live attenuated virus that may be given orally. By frequently evaluating vaccine candidates, scientists ensured that only the most promising contenders continued to subsequent regulatory phases. This workflow dramatically expedited vaccine development. Relatedly, companies were able to invest in large-scale vaccine manufacturing during clinical trials thanks to government financial support. They not only received guaranteed investment installments, but also advanced commitments to purchase vaccines. This significantly decreased the financial risk and saved tremendous amounts of time and resources.

- Public-private partnerships utilize incentives and rewards to foster highly effective and dynamic teams. OWS created a “unique distribution of responsibilities … based upon core competencies rather than on political or financial considerations.” The interests of eight pharmaceutical companies were aligned based on the potential to receive an upfront commitment from the federal government to bulk purchase vaccines. Such approaches are critical to ensuring vaccine R&D not only happens in an efficient, coordinated manner but also that such R&D yields production at scale. Moreover, it enabled a suite of approaches to vaccine development rather than one method, raising the overall probability of developing a successful vaccine.

Repeating these lessons in subsequent EID vaccine developments would generate both significant returns on investment and benefits to society.

Plan of Action

By incentivizing vaccine development for priority EIDs, the federal government can preemptively solve market failures without picking winners or losers.

First, Congress should authorize and appropriate $10 billion to BARDA over 10 years to create a Dynamic Vaccine Development Fund. This fund would build on BARDA’s unique competencies as an engagement platform with the private sector. would allow for new developments to emerge

It would also enact the following strategies, gleaned from all of which were proven to be effective in OWS:

- Advanced market commitments to purchase large quantities of vaccines in cases of an outbreak.

- Ensuring steady incremental progress in combatting the most dangerous EIDs.

- Supporting manufacturing and distribution facilities.

- Providing limited government guarantees, equities, and securities to investors funding vaccine programs for a pre-specified list of priority diseases.

As illustrated by its successful history, BARDA is well-positioned to manage a large-scale vaccine initiative. Last year, BARDA announced the first venture capital partnership with the Global Health Investment Corporation to “allow direct linkage with the investment community and establish sustained and long-term efforts to identify, nurture, and commercialize technologies that aid the U.S. in responding effectively to future health security threats.” During the COVID-19 pandemic, BARDA and Janssen shared the R&D costs to help move Janssen’s investigational novel coronavirus vaccine into clinical evaluation—a collaboration supported by their previous successes on the Ebola vaccine. The Government Accountability Office reported that BARDA had also supported scaled production by identifying additional manufacturing partners. This partnership record shows that BARDA not only knows how to manage global health projects to completion but also is particularly adept at interfacing with the private sector. As such, it stands out as an ideal manager for the Dynamic Vaccine Development Fund.

With $10 billion, this Fund could not only support the vaccine economy, but also save millions of lives and trillions of dollars. Although the price tag is admittedly hefty, it is reasonable. After all, OWS had a price tag of $12+ billion––a small investment compared to the $16+ trillion cost of COVID-19. As seen in OWS, the long-term benefits of upfront, robust financing are even more impactful. One back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests immense economic returns for the Fund:

- With a 50% chance of another $16 trillion COVID-like pandemic in the next 25 years, the expected cost over this timeframe is $8 trillion globally.

- One expected outcome of this Fund would be to prevent 31 of the next 45 pandemics, or a nearly 69% chance of preventing the next epidemic in expectation.

- A 69% chance of preventing an $8 trillion cost over the next 25 years would yield an expected value of $5.6 trillion globally.

A $10 billion down payment would allow the Fund to excel in its normal operations (see bulleted list above) and support up to 120 vaccine candidates. OWS also spawned more than just new breakthrough R&D in the use of mRNA vaccine models. It also led to a health and biotechnology innovation windfall:

“Now that we know that mRNA vaccines work, there is no reason we could not start the process of developing those for the top 20 most likely pandemic pathogen prototypes”

Dr. Francis Collins, former director of the National Institutes of Health

Ten billion dollars would ensure the Fund’s impact could be similarly force-multiplied by private sector partnerships. There would be more time available and more opportunity for creative partnerships with the private sector. The Fund’s purpose is to lower financial risks and attract large amounts of capital from the bond market, whose size outweighs the venture capital, public equity, or private equity markets. Indeed, there has been growing interest in the application of social bonds to pandemic preparedness as a unique instrument for rapidly frontloading resources from capital markets. Though this Fund will assume a different form, the International Finance Facility for Immunisation represents a proof of concept for coordinating philanthropic foundations, governments, and supranational organizations for the purpose of “raising money more quickly.” With seed capital, this Fund could provide a strong signal — and perhaps an anchor for coordination — to debt capital markets to make issuances for vaccines. To this end, the targeted critical mass of $10 billion is estimated to generate both tremendous societal value by preventing future epidemic outbreaks as well as producing positive returns for investors.

Second, in executing Fund activities, BARDA should leverage investment strategies––such as milestone-based payments––to incentivize maximum vaccine innovation. When combatting EIDs, the U.S. will need as many vaccine options as possible. To facilitate this outcome, vaccine manufacturers should be rewarded for producing multiple kinds of vaccines at the same time. For example, BARDA might support the development of vaccines for a given EID by funding progress for four novel methods (e.g., mRNA, recombinant protein, gene-therapy, and live attenuated, orally-administered vaccines).

Furthermore, these rewards should come regularly during major events––or “milestones”––during development. Initial-stage milestones include vaccine candidates that protect an animal model against disease; later-stage milestones include human clinical trials. This financing model would provide companies with clear, short-term targets, reducing uncertainty and rewarding progress dynamically. Additionally, it would support the recent executive order, which calls for “increasing piloting and prototyping efforts in biotechnology and biomanufacturing to accelerate the translation of basic research results into practice.”

BARDA could expand the milestone-based financing mechanism further by employing early-stage challenges. In this scenario, it would only fund the first two of three candidates that successfully complete small-scale clinical trials. The final milestone stage––which should only be offered to a limited number of candidates––should provide an advanced market commitment to house complete vaccines within U.S. storage facilities, based on the interagency effort (described in the paragraph below). The selections process would retain sufficient competition throughout the development process, while ensuring a sustainable method for scaling up certain vaccines based on mission priorities.

Third, to support Fund activities towards late-stage clinical trials, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) should coordinate a larger-scale interagency effort leveraging advanced market commitments, prize challenges, and other innovative procurement techniques. OSTP should be a coordinator across federal agencies that address pandemic preparedness, which might include: the Department of Defense, BARDA, the U.S. Agency for International Development, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the Development Finance Corporation. In doing so, the OSTP can (i) consolidate investments for particular vaccine candidates, and (ii) utilize networks and incentive strategies across the U.S. government to secure vaccines. Separately––and based on urgent priorities shared by agencies––OSTP should work closely with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to explore opportunities for pre-approval of vaccines as they develop through the trial phase.

Conclusion

Vaccines are among the most powerful tools for fighting pandemics. Unfortunately, bringing vaccines to market at scale is challenging. However, Operation Warp Speed (OWS) established a new precedent for tackling vaccine innovation market failures, laying the groundwork for a new era of industrial strategy. Congress should take advantage and supercharge U.S. pandemic preparedness by enabling the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) to build a Dynamic Vaccine Development Fund. Embracing lessons learned from OWS, the Fund would incentivize companies to create vaccines for the six emerging infectious diseases most likely to cause the next pandemic.

The regulatory process for approving vaccines is even more reason to develop them ahead of time—before they are needed, rather than after an outbreak. Having access to an effective vaccine even days sooner can save thousands of lives due to the exponential rate of growth of all infectious diseases. Moreover, the FDA approval process—especially its Emergency Use Authorization Program—is extremely efficient, and is not the bottleneck for vaccine development. The main delay involved in vaccine development is the time it takes to conduct randomized clinical trials. Unfortunately, there are no shortcuts to this process if we want to ensure that vaccines are safe and effective. That is why we need to develop vaccines before pandemics occur. The idea here is simply to develop the minimum viable product of vaccines for priority EIDs that positions these vaccines to rapidly scale in the event of a pandemic.

Yes, there are several examples of vaccine initiatives using this strategy. To list a few:

- The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) has a “megafund” vaccine portfolio (i.e., they have 32 vaccine candidates as of April 2022). This portfolio spans 13 different therapeutic mechanisms and five different stages of clinical development, from preclinical to “Emergency Use Listing” by the World Health Organization.

- BridgeBio, Roivant Sciences have used portfolio-based approaches for drug development.

- The National Brain Tumor Society is also leveraging this approach to finance novel drug candidates that can treat glioblastoma.

Ideally, vaccines in the final milestone stage would be stored in the United States and in line with new CDC guidance in the Vaccine Storage and Handling toolkit. This prevents the scenario where vaccines are held up in transit due to complex international negotiations and, potentially, expire during the lengthy proceedings. This exact scenario occurred when the 300,000 doses of monkeypox vaccine held in a Denmark-based facility were slowly and inconsistently onshored back to the U.S.

In addition, vaccines that are financed through the Fund would not always be final products. Instead, they would potentially be at varying stages of development thanks to the milestone-based payment strategy and frequent progress reviews. This would make it easier for the federal government to closely coordinate vaccine development with manufacturing professionals and rapidly increase vaccine production if necessary. The strategy offered in this memo lowers the risk of a similar situation occurring again.

We recommend that the executive order on biomanufacturing continue exploring this issue and investigate ways to securely store completed vaccines. The Government Accountability Office, for example, recently suggested several promising and discrete changes to update the requirements and operations of the Strategic National Stockpile.

This list was derived from justifications listed on CEPI’s website, linked here.

There are simply too many infectious diseases in nature, and most of are too rare to pose a significant threat. It would be scientifically and financially impractical––and unnecessary––to develop vaccines against all of them. However, we can greatly increase our readiness by widening our scope and developing a library of prototyped vaccines based on the 25 viral families (as called for by CEPI). Doing so would allow us to respond quickly against even unlikely pandemic scenarios.

Public Value Evidence for Public Value Outcomes: Integrating Public Values into Federal Policymaking

Summary

The federal government––through efforts like the White House Year of Evidence for Action––has made a laudable push to ensure that policy decisions are grounded in empirical evidence. While these efforts acknowledge the importance of social, cultural and Indigenous knowledges, they do not draw adequate attention to the challenges of generating, operationalizing, and integrating such evidence in routine policy and decision making. In particular, these endeavors are generally poor at incorporating the living and lived experiences, knowledge, and values of the public. This evidence—which we call evidence about public values—provides important insights for decision making and contributes to better policy or program designs and outcomes.

The federal government should broaden institutional capacity to collect and integrate evidence on public values into policy and decision making. Specifically, we propose that the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP):

- Provide a directive on the importance of public value evidence.

- Develop an implementation roadmap for integrating public value evidence into federal operations (e.g., describe best practices for integrating it into federal decision making, developing skill-building opportunities for federal employees).

Challenge and Opportunity

Evidence about public values informs and improves policies and programs

Evidence about public values is, to put it most simply, information about what people prioritize, care, or think about with respect to a particular issue, which may differ from ideas prioritized by experts. It includes data collected through focus groups, deliberations, citizen review panels, and community-based research, or public opinion surveys. Some of these methods rely on one-way flows of information (e.g., surveys) while others prioritize mutual exchange of information among policy makers and participating publics (e.g., deliberations).

Agencies facing complex policymaking challenges can utilize evidence about public values––along with expert- and evaluation-based evidence––to ensure decisions truly serve the broader public good. If collected as part of the policy-making process, evidence about public values can inform policy goals and programs in real time, including when program goals are taking shape or as programs are deployed.

Evidence about public values within the federal government: three challenges to integration

To fully understand and use public values in policymaking, the U.S. government must first broadly address three challenges.

First, the federal government does not sufficiently value evidence about public values when it researches and designs policy solutions. Federal employees often lack any directive or guidance from leadership that collecting evidence about public values is valuable or important to evidence-based decision making. Efforts like the White House Year of Evidence for Action seek to better integrate evidence into policy making. Yet––for many contexts and topics––scientific or evaluation-based evidence is just one type of evidence. The public’s wisdom, hopes, and perspectives play an important mediating factor in determining and achieving desired public outcomes. The following examples illustrate ways public value evidence can support federal decision making:

- An effort to implement climate intervention technologies (e.g., solar geoengineering) might be well-grounded in evidence from the scientific community. However, that same strategy may not consider the diverse values Americans hold about (i) how such research might be governed, (ii) who ought to develop those technologies, and (iii) whether or not they should be used at all. Public values are imperative for such complex, socio-technical decisions if we are to make good on the Year of Evidence’s dual commitment to scientific integrity (including expanded concepts of expertise and evidence) and equity (better understanding of “what works, for whom, and under what circumstances”).

- Evidence about the impacts of rising sea levels on national park infrastructure and protected features has historically been tense. To acknowledge the social-environmental complexity in play, park leadership have strived to include both expert assessments and engagement with publics on their own risk tolerance for various mitigation measures. This has helped officials prioritize limited resources as they consider tough decisions on what and how to continue to preserve various park features and artifacts.

Second, the federal government lacks effective mechanisms for collecting evidence about public values. Presently, public comment periods favor credentialed participants—advocacy groups, consultants, business groups, etc.—who possess established avenues for sharing their opinions and positions to policy makers. As a result, these credentialed participants shape policy and other experiences, voices, and inputs go unheard. While the general public can contribute to government programs through platforms like Challenge.gov, credentialed participants still tend to dominate these processes. Effective mechanisms for collecting public values into decision making or research are generally confined to university, local government, and community settings. These methods include participatory budgeting, methods from usable or co-produced science, and participatory technology assessment. Some of these methods have been developed and applied to complex science and technology policy issues in particular, including climate change and various emerging technologies. Their use in federal agencies is far more limited. Even when an agency might seek to collect public values, it may be impeded by regulatory hurdles, such as the Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA), which can limit the collection of public values, ideas, or other input due to potentially long timelines for approval and perceived data collection burden on the public. Cumulatively, these factors prevent agencies from accurately gauging––and being adaptive to––public responses.

Third, federal agencies face challenges integrating evidence about public values into policy making. These challenges can be rooted in the regulatory hurdles described above, difficulties integrating with existing processes, and unfamiliarity with the benefits of collecting evidence about public values. Fortunately, studies have found specific attributes present among policymakers and agencies that allowed for the implementation and use of mechanisms for capturing public values. These attributes included:

- Leadership who prioritized public involvement and helped address administrative uncertainties.

- An agency culture responsive to broader public needs, concerns, and wants.

- Agency staff familiar with mechanisms to capture public values and integrate them in the policy- and decision-making process. The latter can help address translation issues, deal with regulatory hurdles, and can better communicate the benefits of collecting public values with regard to agency needs. Unfortunately, many agencies do not have such staff, and there are no existing roadmaps or professional development programs to help build this capacity across agencies.

Aligning public values with current government policies promotes scientific integrity and equity

The White House Year of Evidence for Action presents an opportunity to address the primary challenges––namely a lack of clear direction, collection protocols, and evidence integration strategies––currently impeding public values evidence’s widespread use in the federal government. Our proposal below is well aligned with the Year of Evidence’s central commitments, including:

- A commitment to scientific integrity. Complex problems require expanded concepts of expertise and evidence to ensure that important details and public concerns are not lost or overlooked.

- A commitment to equity. We have a better understanding of “what works, for whom, and under what circumstances” when we have ways of discerning and integrating public values into evidence-based decision making. Methods for integrating public values into decision making complement other emerging best practices––such as the co-creation of evaluation studies and including Indigenous knowledges and perspectives––in the policy making process.

Furthermore, this proposal aligns with the goals of the Year of Evidence for Action to “share leading practices to generate and use research-backed knowledge to advance better, more equitable outcomes for all America…” and to “…develop new strategies and structures to promote consistent evidence-based decision-making inside the Federal Government.”

Plan of Action

To integrate public values into federal policy making, the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) should:

- Develop a high-level directive for agencies about the importance of collecting public values as a form of evidence to inform policy making.

- Oversee the development of a roadmap for the integration of evidence about public values across government, including pathways for training federal employees.

Recommendation 1. OMB and OSTP should issue a high-level directive providing clear direction and strong backing for agencies to collect and integrate evidence on public values into their evidence-based decision-making procedures.

Given the potential utility of integrating public value evidence into science and technology policy as well as OSTP’s involvement in efforts to promote evidence-based policy, OSTP makes a natural partner in crafting this directive alongside OMB. This directive should clearly connect public value evidence to the current policy environment. As described above, efforts like the Foundations for Evidence-Based policy making Act (Evidence Act) and the White House Year of Evidence for Action provide a strong rationale for the collection and integration of evidence about public values. Longer-standing policies––including the Crowdsourcing and Citizen Science Act––provide further context and guidance for the importance of collecting input from broad publics.

Recommendation 2. As part of the directive, or as a follow up to it, OMB and OSTP should oversee the development of a roadmap for integrating evidence about public values across government.

The roadmap should be developed in consultation with various federal stakeholders, such as members of the Evaluation Officer Council, representatives from the Equitable Data Working Group, customer experience strategists, and relevant conceptual and methods experts from within and outside the government.

A comprehensive roadmap would include the following components:

- Appropriate contexts and uses for gathering and integrating public values as evidence. Public values should be collected when the issue is one where scientific or expert evidence is necessary, but not sufficient to address the question at hand. This may be due to (i) uncertainty, (ii) high levels of value disagreement, (iii) cases where the societal implications of a policy or program could be wide ranging, or (iv) situations where policy or program outcomes have inequitable impacts on certain communities.

- Specific approaches to collecting and integrating public values evidence, accompanied by illustrative case studies describing how the methods have been used. While various approaches for measuring and applying public values evidence exist, a few additional conditions can help enable success. These include staff knowledgeable about social science methods and the importance of public value input; clarity of regulatory requirements; and buy-in from agency leadership. These could include practices for: recruiting and convening diverse public participants; promoting exchanges among those participants; comparing public values against scientific or expert evidence; and ensuring that public values are translated into actionable policy solutions.

- Potential training program designs for federal employees. The goal of these training programs should be to develop a workforce that can integrate public value evidence into U.S. policymaking. Participants in these trainings should learn about the importance of integrating evidence about public values alongside other types of evidence, as well as strategies to collect and integrate that evidence into policy and programs. These training programs should promote active learning through applied pilot projects with the learner’s agency or unit.

- Specifying a center tasked with improving methods and tools for integrating evidence about public values into federal decision making. This center could exist as a public-private partnership, a federally-funded research and development center, or an innovation lab1 within an agency. This center could conduct ongoing research, evaluation, and pilot programs of new evidence-gathering methods and tools. This would ensure that as agencies collect and apply evidence about public values, they do so with the latest expertise and techniques.

Conclusion

Collecting evidence about the living and lived experiences, knowledge, and aspirations of the public can help inform policies and programs across government. While methods for collecting evidence about public values have proven effective, they have not been integrated into evidence-based policy efforts within the federal government. The integration of evidence about public values into policy making can promote the provision of broader public goods, elevate the perspectives of historically marginalized communities, and reveal policy or program directions different from those prioritized by experts. The proposed directive and roadmap––while only a first step––would help ensure the federal government considers, respects, and responds to our diverse nation’s values.

Federal agencies can use public value evidence where additional information about what the public thinks, prioritizes, and cares about could improve programs and policies. For example, policy decisions characterized by high uncertainty, potential value disputes, and high stakes could benefit from a broader review of considerations by diverse members of the public to ensure that novel options and unintended consequences are considered in the decision making process. In the context of science and technology related decision making, these situations were called “post-normal science” by Silvio Funtowicz and Jerome Ravetz. They called for an extension of who counts as a subject matter expert in the face of such challenges, citing the potential for technical analyses to overlook important societal values and considerations.

Many issues where science and technology meet societal needs and policy considerations warrant broad public value input. These issues include emerging technologies with societal implications and existing S&T challenges that have far reaching impacts on society (e.g., climate change). Further, OSTP is already involved in Evidence for Action initiatives and can assist in bringing in external expertise on methods and approaches.

While guidance from elected officials is an important mechanism for representing public values, evidence collected about public values through other means can be tailored to specific policy making contexts and can explore issue-specific challenges and opportunities.

There are likely more current examples of identifying and integrating public value evidence than we can point out in government. The roadmap building process should involve identifying those and finding common language to describe diverse public value evidence efforts across government. For specific known examples, see footnotes 1 and 2.

Evidence about public values might include evidence collected through program and policy evaluations but includes broader types of evidence. The evaluation of policies and programs generally focuses on assessing effectiveness or efficiency. Evidence about public values would be used in broader questions about the aims or goals of a program or policy.

Unlocking Federal Grant Data To Inform Evidence-Based Science Funding

Summary

Federal science-funding agencies spend tens of billions of dollars each year on extramural research. There is growing concern that this funding may be inefficiently awarded (e.g., by under-allocating grants to early-career researchers or to high-risk, high-reward projects). But because there is a dearth of empirical evidence on best practices for funding research, much of this concern is anecdotal or speculative at best.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF), as the two largest funders of basic science in the United States, should therefore develop a platform to provide researchers with structured access to historical federal data on grant review, scoring, and funding. This action would build on momentum from both the legislative and executive branches surrounding evidence-based policymaking, as well as on ample support from the research community. And though grantmaking data are often sensitive, there are numerous successful models from other sectors for sharing sensitive data responsibly. Applying these models to grantmaking data would strengthen the incorporation of evidence into grantmaking policy while also guiding future research (such as larger-scale randomized controlled trials) on efficient science funding.

Challenge and Opportunity

The NIH and NSF together disburse tens of billions of dollars each year in the form of competitive research grants. At a high level, the funding process typically works like this: researchers submit detailed proposals for scientific studies, often to particular program areas or topics that have designated funding. Then, expert panels assembled by the funding agency read and score the proposals. These scores are used to decide which proposals will or will not receive funding. (The FAQ provides more details on how the NIH and NSF review competitive research grants.)

A growing number of scholars have advocated for reforming this process to address perceived inefficiencies and biases. Citing evidence that the NIH has become increasingly incremental in its funding decisions, for instance, commentators have called on federal funding agencies to explicitly fund riskier science. These calls grew louder following the success of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19, a technology that struggled for years to receive federal funding due to its high-risk profile.

Others are concerned that the average NIH grant-winner has become too old, especially in light of research suggesting that some scientists do their best work before turning 40. Still others lament the “crippling demands” that grant applications exert on scientists’ time, and argue that a better approach could be to replace or supplement conventional peer-review evaluations with lottery-based mechanisms.

These hypotheses are all reasonable and thought-provoking. Yet there exists surprisingly little empirical evidence to support these theories. If we want to effectively reimagine—or even just tweak—the way the United States funds science, we need better data on how well various funding policies work.

Academics and policymakers interested in the science of science have rightly called for increased experimentation with grantmaking policies in order to build this evidence base. But, realistically, such experiments would likely need to be conducted hand-in-hand with the institutions that fund and support science, investigating how changes in policies and practices shape outcomes. While there is progress in such experimentation becoming a reality, the knowledge gap about how best to support science would ideally be filled sooner rather than later.

Fortunately, we need not wait that long for new insights. The NIH and NSF have a powerful resource at their disposal: decades of historical data on grant proposals, scores, funding status, and eventual research outcomes. These data hold immense value for those investigating the comparative benefits of various science-funding strategies. Indeed, these data have already supported excellent and policy-relevant research. Examples include Ginther et. al (2011) which studies how race and ethnicity affect the probability of receiving an NIH award, and Myers (2020), which studies whether scientists are willing to change the direction of their research in response to increased resources. And there is potential for more. While randomized control trials (RCTs) remain the gold standard for assessing causal inference, economists have for decades been developing methods for drawing causal conclusions from observational data. Applying these methods to federal grantmaking data could quickly and cheaply yield evidence-based recommendations for optimizing federal science funding.

Opening up federal grantmaking data by providing a structured and streamlined access protocol would increase the supply of valuable studies such as those cited above. It would also build on growing governmental interest in evidence-based policymaking. Since its first week in office, the Biden-Harris administration has emphasized the importance of ensuring that “policy and program decisions are informed by the best-available facts, data and research-backed information.” Landmark guidance issued in August 2022 by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy directs agencies to ensure that federally funded research—and underlying research data—are freely available to the public (i.e., not paywalled) at the time of publication.

On the legislative side, the 2018 Foundations for Evidence-based Policymaking Act (popularly known as the Evidence Act) calls on federal agencies to develop a “systematic plan for identifying and addressing policy questions” relevant to their missions. The Evidence Act specifies that the general public and researchers should be included in developing these plans. The Evidence Act also calls on agencies to “engage the public in using public data assets [and] providing the public with the opportunity to request specific data assets to be prioritized for disclosure.” The recently proposed Secure Research Data Network Act calls for building exactly the type of infrastructure that would be necessary to share federal grantmaking data in a secure and structured way.

Plan of Action

There is clearly appetite to expand access to and use of federally held evidence assets. Below, we recommend four actions for unlocking the insights contained in NIH- and NSF-held grantmaking data—and applying those insights to improve how federal agencies fund science.

Recommendation 1. Review legal and regulatory frameworks applicable to federally held grantmaking data.

The White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB)’s Evidence Team, working with the NIH’s Office of Data Science Strategy and the NSF’s Evaluation and Assessment Capability, should review existing statutory and regulatory frameworks to see whether there are any legal obstacles to sharing federal grantmaking data. If the review team finds that the NIH and NSF face significant legal constraints when it comes to sharing these data, then the White House should work with Congress to amend prevailing law. Otherwise, OMB—in a possible joint capacity with the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP)—should issue a memo clarifying that agencies are generally permitted to share federal grantmaking data in a secure, structured way, and stating any categorical exceptions.

Recommendation 2. Build the infrastructure to provide external stakeholders with secure, structured access to federally held grantmaking data for research.

Federal grantmaking data are inherently sensitive, containing information that could jeopardize personal privacy or compromise the integrity of review processes. But even sensitive data can be responsibly shared. The NIH has previously shared historical grantmaking data with some researchers, but the next step is for the NIH and NSF to develop a system that enables broader and easier researcher access. Other federal agencies have developed strategies for handling highly sensitive data in a systematic fashion, which can provide helpful precedent and lessons. Examples include:

- The U.S. Census Bureau (USCB)’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Data. These data link individual workers to their respective firms, and provide information on salary, job characteristics, and worker and firm location. Approved researchers have relied on these data to better understand labor-market trends.

- The Department of Transportation (DOT)’s Secure Data Commons. The Secure Data Commons allows third-party firms (such as Uber, Lyft, and Waze) to provide individual-level mobility data on trips taken. Approved researchers have used these data to understand mobility patterns in cities.

In both cases, the data in question are available to external researchers contingent on agency approval of a research request that clearly explains the purpose of a proposed study, why the requested data are needed, and how those data will be managed. Federal agencies managing access to sensitive data have also implemented additional security and privacy-preserving measures, such as:

- Only allowing researchers to access data via a remote server, or in some cases, inside a Federal Statistical Research Data Center. In other words, the data are never copied onto a researcher’s personal computer.

- Replacing any personal identifiers with random number identifiers once any data merges that require personal identifiers are complete.

- Reviewing any tables or figures prior to circulating or publishing results, to ensure that all results are appropriately aggregated and that no individual-level information can be inferred.

Building on these precedents, the NIH and NSF should (ideally jointly) develop secure repositories to house grantmaking data. This action aligns closely with recommendations from the U.S. Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking, as well as with the above-referenced Secure Research Data Network Act (SRDNA). Both the Commission recommendations and the SRDNA advocate for secure ways to share data between agencies. Creating one or more repositories for federal grantmaking data would be an action that is simultaneously narrower and broader in scope (narrower in terms of the types of data included, broader in terms of the parties eligible for access). As such, this action could be considered either a precursor to or an expansion of the SRDNA, and could be logically pursued alongside SRDNA passage.

Once a secure repository is created, the NIH and NSF should (again, ideally jointly) develop protocols for researchers seeking access. These protocols should clearly specify who is eligible to submit a data-access request, the types of requests that are likely to be granted, and technical capabilities that the requester will need in order to access and use the data. Data requests should be evaluated by a small committee at the NIH and/or NSF (depending on the precise data being requested). In reviewing the requests, the committee should consider questions such as:

- How important and policy-relevant is the question that the researcher is seeking to answer? If policymakers knew the answer, what would they do with that information? Would it inform policy in a meaningful way?

- How well can the researcher answer the question using the data they are requesting? Can they establish a clear causal relationship? Would we be comfortable relying on their conclusions to inform policy?

Finally, NIH and NSF should consider including right-to-review clauses in agreements governing sharing of grantmaking data. Such clauses are typical when using personally identifiable data, as they give the data provider (here, the NIH and NSF) the chance to ensure that all data presented in the final research product has been properly aggregated and no individuals are identifiable. The Census Bureau’s Disclosure Review Board can provide some helpful guidance for NIH and NSF to follow on this front.

Recommendation 3. Encourage researchers to utilize these newly available data, and draw on the resulting research to inform possible improvements to grant funding.

The NIH and NSF frequently face questions and trade-offs when deciding if and how to change existing grantmaking processes. Examples include:

- How can we identify promising early-career researchers if they have less of a track record? What signals should we look for?

- Should we cap the amount of federal funding that individual scientists can receive, or should we let star researchers take on more grants? In general, is it better to spread funding across more researchers or concentrate it among star researchers?

- Is it better to let new grantmaking agencies operate independently, or to embed them within larger, existing agencies?

Typically, these agencies have very little academic or empirical evidence to draw on for answers. A large part of the problem has been the lack of access to data that researchers need to conduct relevant studies. Expanding access, per Recommendations 1 and 2 above, is a necessary part of but not a sufficient solution. Agencies must also invest in attracting researchers to use the data in a socially useful way.

Broadly advertising the new data will be critical. Announcing a new request for proposals (RFP) through the NIH and/or the NSF for projects explicitly using the data could also help. These RFPs could guide researchers toward the highest-impact and most policy-relevant questions, such as those above. The NSF’s “Science of Science: Discovery, Communication and Impact” program would be a natural fit to take the lead on encouraging researchers to use these data.

The goal is to create funding opportunities and programs that give academics clarity on the key issues and questions that federal grantmaking agencies need guidance on, and in turn the evidence academics build should help inform grantmaking policy.

Conclusion

Basic science is a critical input into innovation, which in turn fuels economic growth, health, prosperity, and national security. The NIH and NSF were founded with these critical missions in mind. To fully realize their missions, the NIH and NSF must understand how to maximize scientific return on federal research spending. And to help, researchers need to be able to analyze federal grantmaking data. Thoughtfully expanding access to this key evidence resource is a straightforward, low-cost way to grow the efficiency—and hence impact—of our federally backed national scientific enterprise.

For an excellent discussion of this question, see Li (2017). Briefly, the NIH is organized around 27 “Institutes or Centers” (ICs) which typically correspond to disease areas or body systems. ICs have budgets each year that are set by Congress. Research proposals are first evaluated by around 180 different “study sections”, which are committees organized by scientific areas or methods. After being evaluated by the study sections, proposals are returned to their respective ICs. The highest-scoring proposals in each IC are funded, up to budget limits.

Research proposals are typically submitted in response to announced funding opportunities, which are organized around different programs (topics). Each proposal is sent by the Program Officer to at least three independent reviewers who do not work at the NSF. These reviewers judge the proposal on its Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts. The Program Officer then uses the independent reviews to make a funding recommendation to the Division Director, who makes the final award/decline decision. More details can be found on the NSF’s webpage.

The NIH and NSF both provide data on approved proposals. These data can be found on the RePORTER site for the NIH and award search site for the NSF. However, these data do not provide any information on the rejected applications, nor do they provide information on the underlying scores of approved proposals.

Masks via Mail: Maintaining Critical COVID-19 Infrastructure for Future Public Health Threats

Summary

To protect against future infectious disease outbreaks, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Coordination Operations and Response Element (H-CORE) should develop and maintain the capacity to regularly deliver N95 respirator masks to every home using a mail delivery system. H-CORE previously developed a mailing system to provide free, rapid antigen tests to homes across the U.S. in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. H-CORE can build upon this system to supply the American public with additional disease prevention equipment––notably face masks. H-CORE can helm this expanded mail-delivery system by (i) gathering technical expertise from partnering federal agencies, (ii) deciding which masks are appropriate for public use, (iii) pulling from a rotating face-mask inventory at the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS), and (iv) centralizing subsequent equipment shipping and delivery. In doing so, H-CORE will fortify the pandemic response infrastructure established during the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing the U.S. government to face future pathogens with preparedness and resilience.

Challenge and Opportunity

The infrastructure put in place to respond to COVID-19 should be maintained and improved to better prepare for and respond to the next pandemic. As the federal government thinks about the future of COVID-19 response programs, it should prioritize maintaining systems that can be flexibly used to address a variety of health threats. One critical capability to maintain is the ability to quickly deliver medical countermeasures across the US. This was already done to provide the American public with COVID-19 rapid tests, but additional medical countermeasures––such as N95 respirators––should also be included.

N95s are an incredibly effective means of preventing deadly infectious disease spread. Wearing an N95 respirator reduces the odds of testing positive for COVID-19 by 83%, compared to 66% for surgical masks and 56% for cloth masks. The significant difference between N95 respirators and other face coverings means that N95 respirators can provide real public health benefits against a variety of biothreats, not just COVID-19. Adding N95 respirators to H-CORE’s mailing program would increase public access to a highly effective medical countermeasure that protects against a variety of harmful diseases. Providing equitable access to N95 masks can also protect the United States against other dangerous public health emergencies, not just pandemics. Additionally, N95s protect individuals from harmful, wildfire-smoke-derived airborne particles, providing another use-case beyond protection against viruses.

Beyond the benefit of expanding access to masks in particular, it is important to have an active public health mailing system that can be quickly scaled up to respond to emergencies. In times of need, this established mailing system could distribute a wide array of medical countermeasures, medicines, information, and personal protective equipment––including N95s. Thankfully, the agencies needed to coordinate this effort are already primed to do so. These authorities already have the momentum, expertise, and experience to convert existing COVID-19 response programs and pandemic preparedness investments into permanent health response infrastructure.

Plan of Action

The newly-elevated Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) should house the N95 respirator mailing system, granting H-CORE key management and distribution responsibilities. Evolving out of the operational capacities built from Operation Warp Speed, H-CORE has demonstrated strong logistical capabilities in distributing COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and at-home tests across the United States. H-CORE should continue operating some of these preparedness programs to increase public access to key medical countermeasures. At the same time, it should also maintain the flexibility to pivot and scale up these response programs as soon as the next public health emergency arises.

H-CORE should bolster its free COVID-19 test mailing program and include the option to order one box of 10 free N95 respirator masks every quarter.

H-CORE partnered with the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) to develop an unprecedented initiative––creating an online ordering system for rapid COVID-19 testing to be sent via mail to American households. ASPR should maintain its relationships with USPS and other shipping companies to distribute other needed medical supplies––like N95s. To ensure public comfort, a simple N95 ordering website could be designed to mimic the COVID-19 test ordering site.

An N95-distribution program has already been piloted and proven successful. Thanks to ASPR and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), masks previously held at SNS were made available to the public at select retail pharmacies. This program should be made permanent and expanded to maximize the convenience of obtaining medical countermeasures, like masks. Doing so will likely increase the chance that the general population will acquire and use them. Additionally––if supplies are sourced primarily from domestic mask manufacturers––this program can stabilize demand and incentivize further manufacturing within the United States. Keeping this production at a steady base level will also make it easier to scale up quickly, should America face another pandemic or other public health crisis.

H-CORE and ASPR should coordinate with the SNS to provide N95 respirators through a rotating inventory system.

As evidenced by the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic and the COVID-19 pandemic, static stockpiling large quantities of masks is not an effective way to prepare for the next bio-incident.

Congress has long recognized the need to shift the stockpiling status quo within HSS, including within the SNS. Recent draft legislation––including the Protecting Providers Everywhere (PPE) in America Act and PREVENT Pandemics Act, as well as being mentioned in the National Strategy for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain––have advocated for a rotating stock system. While the concept is mentioned in these documents, there are few details on what the system would look like in practice or a timeline for its implementation.

Ultimately, the SNS should use a rotating inventory system where its stored masks get rotated out to other uses in the supply chain using a “first in, first out” approach. This will prevent N95s from being stored beyond their recommended shelf-life and encourage continual replenishment of the SNS’ mask stockpile.

To make this new rotating inventory system possible, ASPR should pilot rotating inventory through this H-CORE mask mailing program while they decide if and how rotating inventory could be implemented in larger quantities (e.g. rotating out to Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense, and other purchasers). To pilot a rotating inventory system, the Secretary of HHS may enter into contracts and cooperative agreements with vendors, through the SNS contracting mechanisms, and structure the contracts to include maintaining a constant supply and re-stock capacity of the stated product in such quantities as required by the contract. As a guide, the SNS can model these agreements after select pharmaceutical contracts, especially those that have stipulated similar rotating inventory systems (i.e., the radiological countermeasure Neupogen).

The N95 mail-delivery system will allow ASPR, H-CORE, and the SNS to test the rotating stock model in a way that avoids serious risk or negative consequences. The small quantity of N95s needed for the pilot program should not tax the SNS’ supply-at-large. After all, the afore-mentioned H-CORE/NIOSH mask-distribution programs are similarly designed to this pilot, and they do not disrupt the SNS supply for healthcare workers.

Conclusion

To be fully prepared for the next public health emergency, the United States must learn from its previous experience with COVID-19 and continue building the public health infrastructures that proved efficient during this pandemic. Widespread distribution of COVID-19 rapid diagnostic tests is one such success story. The logistics and protocols that made this resource dispersal possible should be continued for other flexible medical countermeasures, like N95 respirators. After all, while the need for COVID-19 tests may wane over time, the relevance of N95 respirators will not.

HHS should therefore distribute N95 respirators to the general public through H-CORE to (i) maintain the existing mailing infrastructure and (ii) increase access to a medical countermeasure that efficiently impedes transmission for many diseases. The masks for this effort should be sourced from the Strategic National Stockpile. This will not only prevent stock expiration, but also pilot rotating inventory as a strategy for larger-scale integration into the SNS. These actions will together equip the public with medical countermeasures relevant to a variety of diseases and strengthen a critical distribution program that should be maintained for future pandemic response.

Medical countermeasures (MCMs) can include both pharmaceutical interventions (such as vaccines, antimicrobials, antivirals, etc.) and non-pharmaceutical interventions (such as ventilators, diagnostics, personal protective equipment, etc.) that are used to prevent, mitigate, or treat the adverse health effects or a public health emergency. Examples of MCM deployment during the COVID-19 pandemic include the COVID-19 vaccines, therapeutics for COVID-19-hospitalized patients (e.g., antivirals and monoclonal antibodies), and personal protective equipment (e.g., respirators and gloves) deployed to healthcare providers and the public.

This proposal would build off of capabilities already being executed under the Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (HHS ASPR). ASPR oversees both H-CORE and the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) and was recently reclassified from a staff division to an operating division. This change allowed ASPR to better mobilize and respond to health-related emergencies. ASPR established H-CORE at the beginning of 2022 to create a permanent team responsible for coordinating medical countermeasures and strengthening preparedness for future pandemics. While H-CORE is currently focused on providing COVID-19 countermeasures––including vaccines, therapeutics, masks, and test kits––their longer-term mission is to augment capabilities within HHS to solve emerging health threats. As such, their ingrained mission and expertise match those required to successfully launch an N95 mail-delivery system.

Presently, 270 million masks have been made available to the U.S. population. It’s estimated that this same number of masks would be enough for American households to receive 10 masks per quarter, assuming a 50% participation rate in the program.

The total annual cost of this program is an estimated $280 million to purchase 270 million masks and facilitate shipping across the United States.

There are several ways this initiative could be funded. Initial funding to purchase and mail COVID-19 tests to homes came from the American Rescue Plan. By passing the COVID Supplemental Appropriations Act, Congress could provide supplemental funds to maintain standing COVID-19 programs and help pivot them to address evolving and future health threats.

The FY2023 President’s Budget for HHS also provides ample funding for H-CORE, the SNS, and ASPR, meaning it could also provide alternative funding for an N95 mail-delivery system. Presently, the budget asks for: $133 million for H-CORE and mentions their role in making masks available nationwide. Additionally, $975 million has been allotted to the SNS, which includes coordination with HHS and maintaining the stockpile. Furthermore, is petitions for ASPR to receive $12 billion to generally prepare for pandemics and other future biological threats (and here it also specifically recommends strong coordination with HHS agency efforts).

N95 respirators have a number of benefits that make them a critical defense strategy in a public health emergency. First, they are pathogen-agnostic, shelf-stable countermeasures that filter airborne particles very efficiently, meaning they can impede transmission for a variety of diseases––especially airborne and aerosolized ones. This is important, since these two latter disease categories are the most likely naturally occurring and intentional biothreats. Second, N95 respirators are useful beyond pandemic responses and also protect against wildfire smoke. Additionally, N95 masks have a long shelf-life. Therefore, the ability to quickly and widely distribute N95s is a critical public health preparedness measure.

Domestic mask manufacturers have also frequently experienced boom and bust cycles as public demand for masks can change rapidly and without warning. This inconsistent market makes it difficult for manufacturers to invest in increased manufacturing capacity in the long-term. One example is the company Prestige Ameritech, which invested over $1 million in new equipment and hired 150 new workers to produce masks in response to the 2009 swine flu outbreak. However, by the time production was ready, demand for masks had dropped and the company almost went bankrupt. Given overwhelmingly positive benefits of having mask manufacturing capacity available when needed, it is worthwhile for the government to provide some ongoing demand certainty.

Furthermore, making masks free and easily available to the general public could increase the public’s mask usage during the annual flu season and other periods of sickness. While personal protective equipment has decreased in cost since the peak of the pandemic, making them as accessible as possible will disproportionately increase access for low-income citizens and help ensure equitable access to protective medical countermeasures.

It is true that N95s are not regulated outside of healthcare settings, but that shouldn’t dissuade public use. Presently, there is no federal agency currently tasked with regulating respiratory protection for the public. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) currently have a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) coordinating regulatory authority over N95 respirators for medical use. Neither the FDA nor NIOSH, though, have jurisdiction of mask use in a non-medical, non-occupational setting. Using an N95 respirator outside of a medical setting does not satisfy all of the regulatory requirements, like undergoing a fit-test to ensure proper seal. However, using N95 respirators for every-day respiratory protection (i) provides better protection than no mask, a cloth mask, or a surgical mask, and (ii) realistically should not need to meet the same regulatory standards as medical use as people are not regularly exposed to the same level of risk as medical professionals.

Presently, there is no central regulator for public respiratory protection in general. In fact, the National Academies of Science Engineering and Medicine recently issued a recommendation for Congress to “expeditiously establish a coordinating entity within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) with the necessary responsibility, authority, and resources (financial, personnel, and infrastructure) to provide a unified and authoritative source of information and effective oversight in the development, approval, and use of respiratory protective devices that can meet the needs of the public and protect the public health.”

Moving forward, NIOSH alone should regulate N95 use for the public just as they do in occupational settings. The approval process used by other regulators––like the FDA––is more restrictive than necessary for public use. The FDA’s standards for medical protection understandably need to be high in order to protect doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals against a wide variety of dangerous exposure situations. NIOSH can provide alternative regulation and guidance for the general public, who realistically are unlikely to be in similar circumstances.

Aside from federal agencies, professional scientific societies have also provided their input in regulating N95s. The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), for example, recently published standards for barrier face coverings not intended for medical use or currently regulated under NIOSH standards. While ASTM does not have any regulatory or enforcement authority, HHS could use these standards for protection, comfort, and usability as a starting point for developing guidelines for respirators suitable for public distribution and use.

After the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic and the COVID-19 pandemic, it became evident that SNS must change its stockpile management practices. The stockpile’s reserves of N95 respirators were not sufficiently replenished after the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, in large part due to the significant up-front supply restocking cost. During the early days of COVID-19 response, many states received expired respirators and broken ventilators from the SNS. These incidents revealed a number of issues with the current stockpiling paradigm. Shifting to a rotating inventory system would prevent issues with expiration, smooth out the costs of large periodic restocks, and help maintain a capable and responsive manufacturing base.

Strengthening Policy by Bringing Evidence to Life

Summary

In a 2021 memorandum, President Biden instructed all federal executive departments and agencies to “make evidence-based decisions guided by the best available science and data.” This policy is sound in theory but increasingly difficult to implement in practice. With millions of new scientific papers published every year, parsing and acting on research insights presents a formidable challenge.

A solution, and one that has proven successful in helping clinicians effectively treat COVID-19, is to take a “living” approach to evidence synthesis. Conventional systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and associated guidelines and standards, are published as static products, and are updated infrequently (e.g., every four to five years)—if at all. This approach is inefficient and produces evidence products that quickly go out of date. It also leads to research waste and poorly allocated research funding.

By contrast, emerging “Living Evidence” models treat knowledge synthesis as an ongoing endeavor. By combining (i) established, scientific methods of summarizing science with (ii) continuous workflows and technology-based solutions for information discovery and processing, Living Evidence approaches yield systematic reviews—and other evidence and guidance—products that are always current.

The recent launch of the White House Year of Evidence for Action provides a pivotal opportunity to harness the Living Evidence model to accelerate research translation and advance evidence-based policymaking. The federal government should consider a two-part strategy to embrace and promote Living Evidence. The first part of this strategy positions the U.S. government to lead by example by embedding Living Evidence within federal agencies. The second part focuses on supporting external actors in launching and maintaining Living Evidence resources for the public good.

Challenge and Opportunity

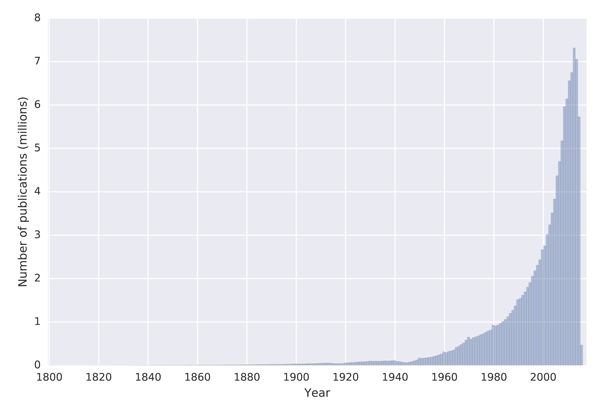

We live in a time of veritable “scientific overload”. The number of scientific papers in the world has surged exponentially over the past several decades (Figure 1), and millions of new scientific papers are published every year. Making sense of this deluge of documents presents a formidable challenge. For any given topic, experts have to (i) scour the scientific literature for studies on that topic, (ii) separate out low-quality (or even fraudulent) research, (iii) weigh and reconcile contradictory findings from different studies, and (iv) synthesize study results into a product that can usefully inform both societal decision-making and future scientific inquiry.

This process has evolved over several decades into a scientific method known as “systematic review” or “meta-analysis”. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are detailed and credible, but often take over a year to produce and rapidly go out of date once published. Experts often compensate by drawing attention to the latest research in blog posts, op-eds, “narrative” reviews, informal memos, and the like. But while such “quick and dirty” scanning of the literature is timely, it lacks scientific rigor. Hence those relying on “the best available science” to make informed decisions must choose between summaries of science that are reliable or current…but not both.

The lack of trustworthy and up-to-date summaries of science constrains efforts, including efforts championed by the White House, to promote evidence-informed policymaking. It also leads to research waste when scientists conduct research that is duplicative and unnecessary, and degrades the efficiency of the scientific ecosystem when funders support research that does not address true knowledge gaps.

Total number of scientific papers published over time, according to the Microsoft Access Graph (MAG) dataset. (Source: Herrmannova and Knoth, 2016)

The emerging Living Evidence paradigm solves these problems by treating knowledge synthesis as an ongoing rather than static endeavor. By combining (i) established, scientific methods of summarizing science with (ii) continuous workflows and technology-based solutions for information discovery and processing, Living Evidence approaches yield systematic reviews that are always up to date with the latest research. An opinion piece published in The New York Times called this approach “a quiet revolution to surface the best-available research and make it accessible for all.”

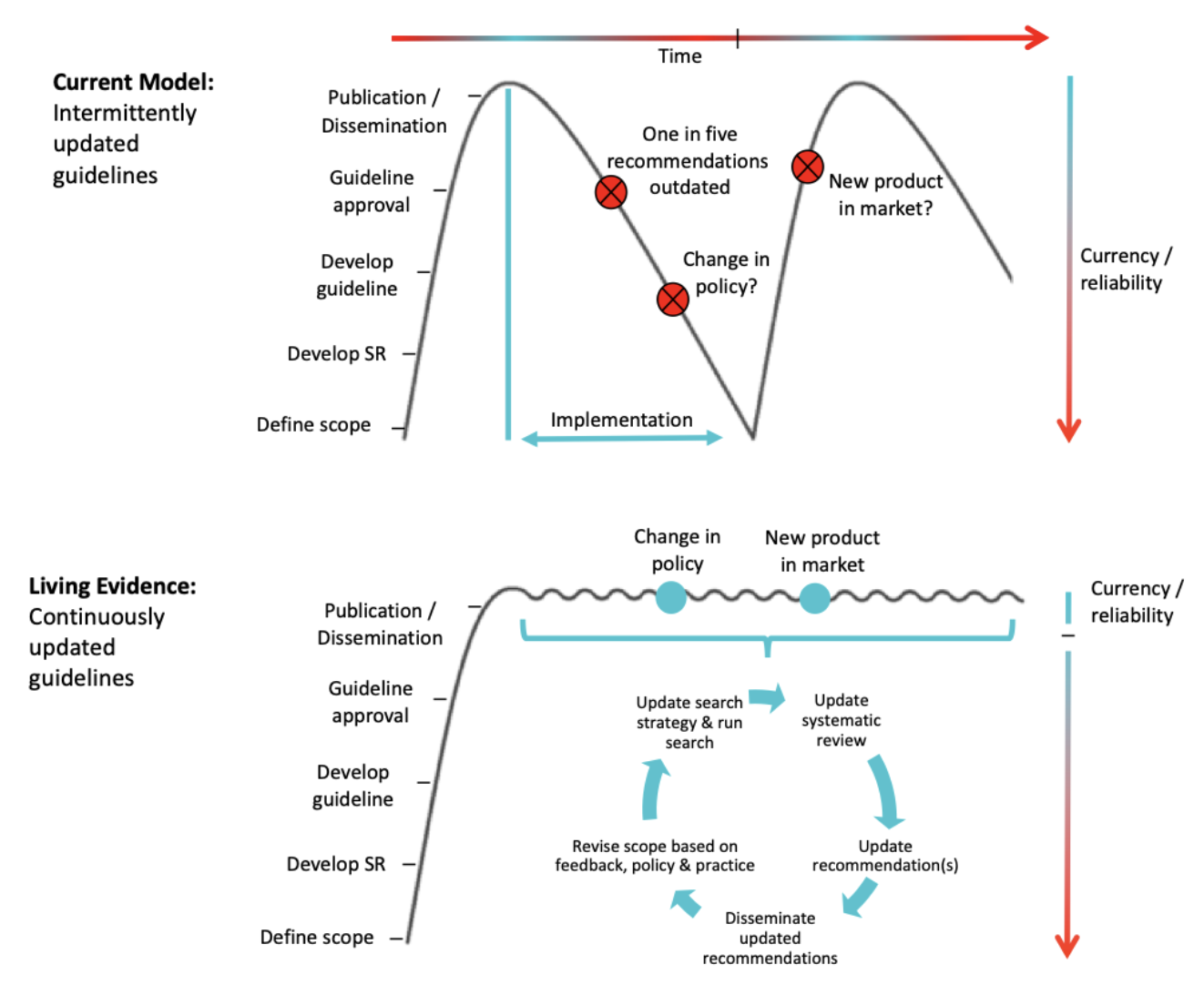

To take a Living Evidence approach, multidisciplinary teams of subject-matter experts and methods experts (e.g., information specialists and data scientists) first develop an evidence resource—such as a systematic review—using standard approaches. But the teams then commit to regular updates of the evidence resource at a frequency that makes sense for their end users (e.g., once a month). Using technologies such as natural-language processing and machine learning, the teams continually monitor online databases to identify new research. Any new research is rapidly incorporated into the evidence resource using established methods for high-quality evidence synthesis. Figure 2 illustrates how Living Evidence builds on and improves traditional approaches for evidence-informed development of guidelines, standards, and other policy instruments.

Illustration of how a Living Evidence approach to development of evidence-informed policies (such as clinical guidelines) is more current and reliable than traditional approaches. (Source: Author-developed graphic)

Living Evidence products are more trusted by stakeholders, enjoy greater engagement (up to a 300% increase in access/use, based on internal data from the Australian Stroke Foundation), and support improved translation of research into practice and policy. Living Evidence holds particular value for domains in which research evidence is emerging rapidly, current evidence is uncertain, and new research might change policy or practice. For example, Nature has credited Living Evidence with “help[ing] chart a route out” of the worst stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) has since committed to using the Living Evidence approach as the organization’s “main platform” for knowledge synthesis and guideline development across all health issues.

Yet Living Evidence approaches remain underutilized in most domains. Many scientists are unaware of Living Evidence approaches. The minority who are familiar often lack the tools and incentives to carry out Living Evidence projects directly. The result is an “evidence to action” pipeline far leakier than it needs to be. Entities like government agencies need credible and up-to-date evidence to efficiently and effectively translate knowledge into impact.

It is time to change the status quo. The 2019 Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act (“Evidence Act”) advances “a vision for a nation that relies on evidence and data to make decisions at all levels of government.” The Biden Administration’s “Year of Evidence” push has generated significant momentum around evidence-informed policymaking. Demonstrated successes of Living Evidence approaches with respect to COVID-19 have sparked interest in these approaches specifically. The time is ripe for the federal government to position Living Evidence as the “gold standard” of evidence products—and the United States as a leader in knowledge discovery and synthesis.

Plan of Action

The federal government should consider a two-part strategy to embrace and promote Living Evidence. The first part of this strategy positions the U.S. government to lead by example by embedding Living Evidence within federal agencies. The second part focuses on supporting external actors in launching and maintaining Living Evidence resources for the public good.

Part 1. Embedding Living Evidence within federal agencies

Federal science agencies are well positioned to carry out Living Evidence approaches directly. Living Evidence requires “a sustained commitment for the period that the review remains living.” Federal agencies can support the continuous workflows and multidisciplinary project teams needed for excellent Living Evidence products.

In addition, Living Evidence projects can be very powerful mechanisms for building effective, multi-stakeholder partnerships that last—a key objective for a federal government seeking to bolster the U.S. scientific enterprise. A recent example is Wellcome Trust’s decision to fund suites of living systematic reviews in mental health as a foundational investment in its new mental-health strategy, recognizing this as an important opportunity to build a global research community around a shared knowledge source.