Creating Auditing Tools for AI Equity

The unregulated use of algorithmic decision-making systems (ADS)—systems that crunch large amounts of personal data and derive relationships between data points—has negatively affected millions of Americans. These systems impact equitable access to education, housing, employment, and healthcare, with life-altering effects. For example, commercial algorithms used to guide health decisions for approximately 200 million people in the United States each year were found to systematically discriminate against Black patients, reducing, by more than half, the number of Black patients who were identified as needing extra care.

One way to combat algorithmic harm is by conducting system audits, yet there are currently no standards for auditing AI systems at the scale necessary to ensure that they operate legally, safely, and in the public interest. According to one research study examining the ecosystem of AI audits, only one percent of AI auditors believe that current regulation is sufficient.

To address this problem, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) should invest in the development of comprehensive AI auditing tools, and federal agencies with the charge of protecting civil rights and liberties should collaborate with NIST to develop these tools and push for comprehensive system audits.

These auditing tools would help the enforcement arms of these federal agencies save time and money while fulfilling their statutory duties. Additionally, there is a pressing need to develop these tools now, with Executive Order 13985 instructing agencies to “focus their civil rights authorities and offices on emerging threats, such as algorithmic discrimination in automated technology.”

Challenge and Opportunity

The use of AI systems across all aspects of life has become commonplace as a way to improve decision-making and automate routine tasks. However, their unchecked use can perpetuate historical inequities, such as discrimination and bias, while also potentially violating American civil rights.

Algorithmic decision-making systems are often used in prioritization, classification, association, and filtering tasks in a way that is heavily automated. ADS become a threat when people uncritically rely on the outputs of a system, use them as a replacement for human decision-making, or use systems with no knowledge of how they were developed. These systems, while extremely useful and cost-saving in many circumstances, must be created in a way that is equitable and secure.

Ensuring the legal and safe use of ADS begins with recognizing the challenges that the federal government faces. On the one hand, the government wants to avoid devoting excessive resources to managing these systems. With new AI system releases happening everyday, it is becoming unreasonable to oversee every system closely. On the other hand, we cannot blindly trust all developers and users to make appropriate choices with ADS.

This is where tools for the AI development lifecycle come into play, offering a third alternative between constant monitoring and blind trust. By implementing auditing tools and signatory practices, AI developers will be able to demonstrate compliance with preexisting and well-defined standards while enhancing the security and equity of their systems.

Due to the extensive scope and diverse applications of AI systems, it would be difficult for the government to create a centralized body to oversee all systems or demand each agency develop solutions on its own. Instead, some responsibility should be shifted to AI developers and users, as they possess the specialized knowledge and motivation to maintain proper functioning systems. This allows the enforcement arms of federal agencies tasked with protecting the public to focus on what they do best, safeguarding citizens’ civil rights and liberties.

Plan of Action

To ensure security and verification throughout the AI development lifecycle, a suite of auditing tools is necessary. These tools should help enable outcomes we care about, fairness, equity, and legality. The results of these audits should be reported (for example, in an immutable ledger that is only accessible by authorized developers and enforcement bodies) or through a verifiable code-signing mechanism. We leave the specifics of the reporting and documenting the process to the stakeholders involved, as each agency may have different reporting structures and needs. Other possible options, such as manual audits or audits conducted without the use of tools, may not provide the same level of efficiency, scalability, transparency, accuracy, or security.

The federal government’s role is to provide the necessary tools and processes for self-regulatory practices. Heavy-handed regulations or excessive government oversight are not well-received in the tech industry, which argues that they tend to stifle innovation and competition. AI developers also have concerns about safeguarding their proprietary information and users’ personal data, particularly in light of data protection laws.

Auditing tools provide a solution to this challenge by enabling AI developers to share and report information in a transparent manner while still protecting sensitive information. This allows for a balance between transparency and privacy, providing the necessary trust for a self-regulating ecosystem.

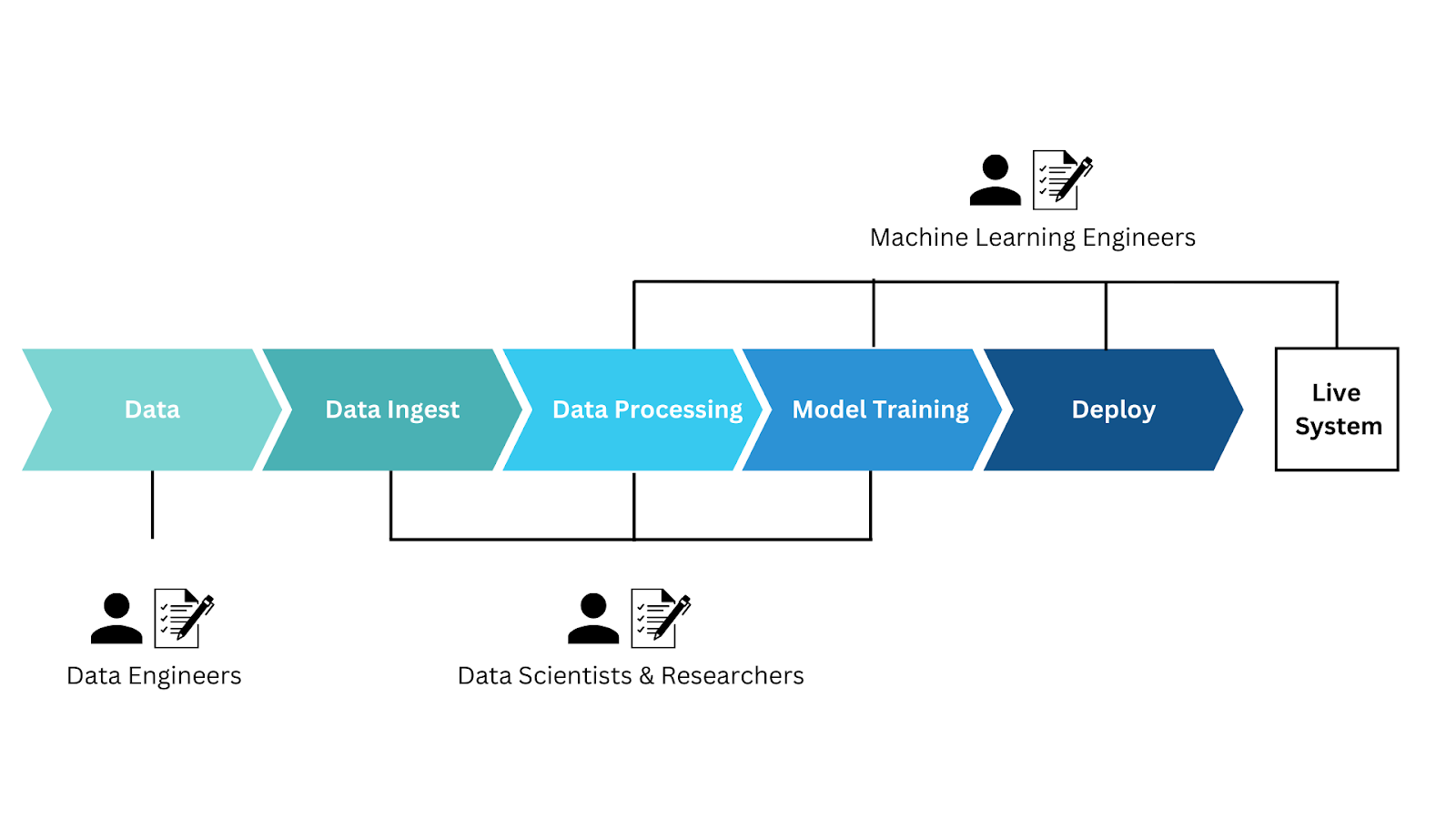

A general machine learning lifecycle. Examples of what system developers at each stage would be responsible for signing off on the use of the security and equity tools in the lifecycle. These developers represent companies, teams, or individuals.

The equity tool and process, funded and developed by government agencies such as NIST, would consist of a combination of (1) AI auditing tools for security and fairness (which could be based on or incorporate open source tools such as AI Fairness 360 and the Adversarial Robustness Toolbox), and (2) a standardized process and guidance for integrating these checks (which could be based on or incorperate guidance such as the U.S. Government Accountability Office’s Artificial Intelligence: An Accountability Framework for Federal Agencies and Other Entities).1

Dioptra, a recent effort between NIST and the National Cybersecurity Center of Excellence (NCCoE) to build machine learning testbeds for security and robustness, is an excellent example of the type of lifecycle management application that would ideally be developed. Failure to protect civil rights and ensure equitable outcomes must be treated as seriously as security flaws, as both impact our national security and quality of life.

Equity considerations should be applied across the entire lifecycle; training data is not the only possible source of problems. Inappropriate data handling, model selection, algorithm design, and deployment, also contribute to unjust outcomes. This is why tools combined with specific guidance is essential.

As some scholars note, “There is currently no available general and comparative guidance on which tool is useful or appropriate for which purpose or audience. This limits the accessibility and usability of the toolkits and results in a risk that a practitioner would select a sub-optimal or inappropriate tool for their use case, or simply use the first one found without being conscious of the approach they are selecting over others.”

Companies utilizing the various packaged tools on their ADS could sign off on the results using code signing. This would create a record that these organizations ran these audits along their development lifecycle and received satisfactory outcomes.

We envision a suite of auditing tools, each tool applying to a specific agency and enforcement task. Precedents for this type of technology already exist. Much like security became a part of the software development lifecycle with guidance developed by NIST, equity and fairness should be integrated into the AI lifecycle as well. NIST could spearhead a government-wide initiative on auditing AI tools, leading guidance, distribution, and maintenance of such tools. NIST is an appropriate choice considering its history of evaluating technology and providing guidance around the development and use of specific AI applications such as the NIST-led Face Recognition Vendor Test (FRVT).

Areas of Impact & Agencies / Departments Involved

Security & Justice

The U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Special Litigation SectionDepartment of Homeland Security U.S. Customs and Border Protection U.S. Marshals Service

Public & Social Sector

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity

Education

The U.S. Department of Education

Environment

The U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil RightsThe Federal Energy Regulatory CommissionThe Environmental Protection Agency

Crisis Response

Federal Emergency Management Agency

Health & Hunger

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Civil RightsCenter for Disease Control and PreventionThe Food and Drug Administration

Economic

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, The U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs

Infrastructure

The U.S. Department of Transportation, Office of Civil RightsThe Federal Aviation AdministrationThe Federal Highway Administration

Information Verification & Validation

The Federal Trade Commission, The Federal Communication Commission, The Securities and Exchange Commission.

Many of these tools are open source and free to the public. A first step could be combining these tools with agency-specific standards and plain language explanations of their implementation process.

Benefits

These tools would provide several benefits to federal agencies and developers alike. First, they allow organizations to protect their data and proprietary information while performing audits. Any audits, whether on the data, model, or overall outcomes, would be run and reported by the developers themselves. Developers of these systems are the best choice for this task since ADS applications vary widely, and the particular audits needed depend on the application.

Second, while many developers may opt to use these tools voluntarily, standardizing and mandating their use would allow an evaluation of any system thought to be in violation of the law to be easily assesed. In this way, the federal government will be able to manage standards more efficiently and effectively.

Third, although this tool would be designed for the AI lifecycle that results in ADS, it can also be applied to traditional auditing processes. Metrics and evaluation criteria will need to be developed based on existing legal standards and evaluation processes; once these metrics are distilled for incorporation into a specific tool, this tool can be applied to non-ADS data as well, such as outcomes or final metrics from traditional audits.

Fourth, we believe that a strong signal from the government that equity considerations in ADS are important and easily enforceable will impact AI applications more broadly, normalizing these considerations.

Example of Opportunity

An agency that might use this tool is the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), whose purpose is to ensure that housing providers do not discriminate based on race, color, religion, national origin, sex, familial status, or disability.

To enforce these standards, HUD, which is responsible for 21,000 audits a year, investigates and audits housing providers to assess compliance with the Fair Housing Act, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, and other related regulations. During these audits, HUD may review a provider’s policies, procedures, and records, as well as conduct on-site inspections and tests to determine compliance.

Using an AI auditing tool could streamline and enhance HUD’s auditing processes. In cases where ADS were used and suspected of harm, HUD could ask for verification that an auditing process was completed and specific metrics were met, or require that such a process be undergone and reported to them.

Noncompliance with legal standards of nondiscrimination would apply to ADS developers as well, and we envision the enforcement arms of protection agencies would apply the same penalties in these situations as they would in non-ADS cases.

R&D

To make this approach feasible, NIST will require funding and policy support to implement this plan. The recent CHIPS and Science Act has provisions to support NIST’s role in developing “trustworthy artificial intelligence and data science,” including the testbeds mentioned above. Research and development can be partially contracted out to universities and other national laboratories or through partnerships/contracts with private companies and organizations.

The first iterations will need to be developed in partnership with an agency interested in integrating an auditing tool into its processes. The specific tools and guidance developed by NIST must be applicable to each agency’s use case.

The auditing process would include auditing data, models, and other information vital to understanding a system’s impact and use, informed by existing regulations/guidelines. If a system is found to be noncompliant, the enforcement agency has the authority to impose penalties or require changes to be made to the system.

Pilot program

NIST should develop a pilot program to test the feasibility of AI auditing. It should be conducted on a smaller group of systems to test the effectiveness of the AI auditing tools and guidance and to identify any potential issues or areas for improvement. NIST should use the results of the pilot program to inform the development of standards and guidelines for AI auditing moving forward.

Collaborative efforts

Achieving a self-regulating ecosystem requires collaboration. The federal government should work with industry experts and stakeholders to develop the necessary tools and practices for self-regulation.

A multistakeholder team from NIST, federal agency issue experts, and ADS developers should be established during the development and testing of the tools. Collaborative efforts will help delineate responsibilities, with AI creators and users responsible for implementing and maintaining compliance with the standards and guidelines, and agency enforcement arms agency responsible for ensuring continued compliance.

Regular monitoring and updates

The enforcement agencies will continuously monitor and update the standards and guidelines to keep them up to date with the latest advancements and to ensure that AI systems continue to meet the legal and ethical standards set forth by the government.

Transparency and record-keeping

Code-signing technology can be used to provide transparency and record-keeping for ADS. This can be used to store information on the auditing outcomes of the ADS, making reporting easy and verifiable and providing a level of accountability to users of these systems.

Conclusion

Creating auditing tools for ADS presents a significant opportunity to enhance equity, transparency, accountability, and compliance with legal and ethical standards. The federal government can play a crucial role in this effort by investing in the research and development of tools, developing guidelines, gathering stakeholders, and enforcing compliance. By taking these steps, the government can help ensure that ADS are developed and used in a manner that is safe, fair, and equitable.

Code signing is used to establish trust in code that is distributed over the internet or other networks. By digitally signing the code, the code signer is vouching for its identity and taking responsibility for its contents. When users download code that has been signed, their computer or device can verify that the code has not been tampered with and that it comes from a trusted source.

Code signing can be extended to all parts of the AI lifecycle as a means of verifying the authenticity, integrity, and function of a particular piece of code or a larger process. After each step in the auditing process, code signing enables developers to leave a well-documented trail for enforcement bodies/auditors to follow if a system were suspected of unfair discrimination or unsafe operation.

Code signing is not essential for this project’s success, and we believe that the specifics of the auditing process, including documentation, are best left to individual agencies and their needs. However, code signing could be a useful piece of any tools developed.

Additionally, there may be pushback on the tool design. It is important to remember that currently, engineers often use fairness tools at the end of a development process, as a last box to check, instead of as an integrated part of the AI development lifecycle. These concerns can be addressed by emphasizing the comprehensive approach taken and by developing the necessary guidance to accompany these tools—which does not currently exist.

New York regulators are calling on a UnitedHealth Group to either stop using or prove there is no problem with a company-made algorithm that researchers say exhibited significant racial bias. This algorithm, which UnitedHealth Group sells to hospitals for assessing the health risks of patients, assigned similar risk scores to white patients and Black patients despite the Black patients being considerably sicker.

In this case, researchers found that changing just one parameter could generate “an 84% reduction in bias.” If we had specific information on the parameters going into the model and how they are weighted, we would have a record-keeping system to see how certain interventions affected the output of this model.

Bias in AI systems used in healthcare could potentially violate the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race. If the algorithm is found to have a disproportionately negative impact on a certain racial group, this could be considered discrimination. It could also potentially violate the Due Process Clause, which protects against arbitrary or unfair treatment by the government or a government actor. If an algorithm used by hospitals, which are often funded by the government or regulated by government agencies, is found to exhibit significant racial bias, this could be considered unfair or arbitrary treatment.

Example #2: Policing

A UN panel on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has raised concern over the increasing use of technologies like facial recognition in law enforcement and immigration, warning that it can exacerbate racism and xenophobia and potentially lead to human rights violations. The panel noted that while AI can enhance performance in some areas, it can also have the opposite effect as it reduces trust and cooperation from communities exposed to discriminatory law enforcement. Furthermore, the panel highlights the risk that these technologies could draw on biased data, creating a “vicious cycle” of overpolicing in certain areas and more arrests. It recommends more transparency in the design and implementation of algorithms used in profiling and the implementation of independent mechanisms for handling complaints.

A case study on the Chicago Police Department’s Strategic Subject List (SSL) discusses an algorithm-driven technology used by the department to identify individuals at high risk of being involved in gun violence and inform its policing strategies. However, a study by the RAND Corporation on an early version of the SSL found that it was not successful in reducing gun violence or reducing the likelihood of victimization, and that inclusion on the SSL only had a direct effect on arrests. The study also raised significant privacy and civil rights concerns. Additionally, findings reveal that more than one-third of individuals on the SSL, approximately 70% of that cohort, have never been arrested or been a victim of a crime yet received a high-risk score. Furthermore, 56% of Black men under the age of 30 in Chicago have a risk score on the SSL. This demographic has also been disproportionately affected by the CPD’s past discriminatory practices and issues, including torturing Black men between 1972 and 1994, performing unlawful stops and frisks disproportionately on Black residents, engaging in a pattern or practice of unconstitutional use of force, poor data collection, and systemic deficiencies in training and supervision, accountability systems, and conduct disproportionately affecting Black and Latino residents.

Predictive policing, which uses data and algorithms to try to predict where crimes are likely to occur, has been criticized for reproducing and reinforcing biases in the criminal justice system. This can lead to discriminatory practices and violations of the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures, as well as the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law. Additionally, bias in policing more generally can also violate these constitutional provisions, as well as potentially violating the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition on excessive force.

Example #3: Recruiting

ADS in recruiting crunch large amounts of personal data and, given some objective, derive relationships between data points. The aim is to use systems capable of processing more data than a human ever could to uncover hidden relationships and trends that will then provide insights for people making all types of difficult decisions.

Hiring managers across different industries use ADS every day to aid in the decision-making process. In fact, a 2020 study reported that 55% of human resources leaders in the United States use predictive algorithms across their business practices, including hiring decisions.

For example, employers use ADS to screen and assess candidates during the recruitment process and to identify best-fit candidates based on publicly available information. Some systems even analyze facial expressions during interviews to assess personalities. These systems promise organizations a faster, more efficient hiring process. ADS do theoretically have the potential to create a fairer, qualification-based hiring process that removes the effects of human bias. However, they also possess just as much potential to codify new and existing prejudice across the job application and hiring process.

The use of ADS in recruiting could potentially violate several constitutional laws, including discrimination laws such as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Americans with Disabilities Act. These laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, gender, and disability, among other protected characteristics, in the workplace. Additionally, the these systems could also potentially violate the right to privacy and the due process rights of job applicants. If the systems are found to be discriminatory or to violate these laws, they could result in legal action against the employers.

Supporting Historically Disadvantaged Workers through a National Bargaining in Good Faith Fund

Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) are underrepresented in labor unions. Further, people working in the gig economy, tech supply chain, and other automation-adjacent roles face a huge barrier to unionizing their workplaces. These roles, which are among the fastest-growing segments of the U.S. economy, are overwhelmingly filled by BIPOC workers. In the absence of safety nets for these workers, the racial wealth gap will continue to grow. The Biden-Harris Administration can promote racial equity and support low-wage BIPOC workers’ unionization efforts by creating a National Bargaining in Good Faith Fund.

As a whole, unions lift up workers to a better standard of living, but historically they have failed to protect workers of color. The emergence of labor unions in the early 20th century was propelled by the passing of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), also known as the Wagner Act of 1935. Although the NLRA was a beacon of light for many working Americans, affording them the benefits of union membership such as higher wages, job security, and better working conditions, which allowed many to transition into the middle class, the protections of the law were not applied to all working people equally. Labor unions in the 20th century were often segregated, and BIPOC workers were often excluded from the benefits of unionization. For example, the Wagner Act excluded domestic and agricultural workers and permitted labor unions to discriminate against workers of color in other industries, such as manufacturing.

Today, in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and amid a renewed interest in a racial reckoning in the United States, BIPOC workers—notably young and women BIPOC workers—are leading efforts to organize their workplaces. In addition to demanding wage equity and fair treatment, they are also fighting for health and safety on the job. Unionized workers earn on average 11.2% more in wages than their nonunionized peers. Unionized Black workers earn 13.7% more and unionized Hispanic workers 20.1% more than their nonunionized peers. But every step of the way, tech giants and multinational corporations are opposing workers’ efforts and their legal right to organize, making organizing a risky undertaking.

A National Bargaining in Good Faith Fund would provide immediate and direct financial assistance to workers who have been retaliated against for attempting to unionize, especially those from historically disadvantaged groups in the United States. This fund offers a simple and effective solution to alleviate financial hardships, allowing affected workers to use the funds for pressing needs such as rent, food, or job training. It is crucial that we advance racial equity, and this fund is one step toward achieving that goal by providing temporary financial support to workers during their time of need. Policymakers should support this initiative as it offers direct payments to workers who have faced illegal retaliation, providing a lifeline for historically disadvantaged workers and promoting greater economic justice in our society.

Challenges and Opportunities

The United States faces several triangulating challenges. First is our rapidly evolving economy, which threatens to displace millions of already vulnerable low-wage workers due to technological advances and automation. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated automation, which is a long-term strategy for the tech companies that underpin the gig economy. According to a report by an independent research group, self-driving taxis are likely to dominate the ride-hailing market by 2030, potentially displacing 8 million human drivers in the United States alone.

Second, we have a generation of workers who have not reaped the benefits associated with good-paying union jobs due to decades of anti-union activities. As of 2022, union membership has dropped from more than 30% of wage and salary workers in the private sector in the 1950s to just 6.3%. The declining percentage of workers represented by unions is associated with widespread and deep economic inequality, stagnant wages, and a shrinking middle class. Lower union membership rates have contributed to the widening of the pay gap for women and workers of color.

Third, historically disadvantaged groups are overrepresented in nonunionized, low-wage, app-based, and automation-adjacent work. This is due in large part to systemic racism. These structures adversely affect BIPOC workers’ ability to obtain quality education and training, create and pass on generational wealth, or follow through on the steps required to obtain union representation.

Workers face tremendous opposition to unionization efforts from companies that spend hundreds of millions of dollars and use retaliatory actions, disinformation, and other intimidating tactics to stop them from organizing a union. For example, in New York, Black organizer Chris Smalls led the first successful union drive in a U.S. Amazon facility after the company fired him for his activities and made him a target of a smear campaign against the union drive. Smalls’s story is just one illustration of how BIPOC workers are in the middle of the collision between automation and anti-unionization efforts.

The recent surge of support for workers’ rights is a promising development, but BIPOC workers face challenges that extend beyond anti-union tactics. Employer retaliation is also a concern. Workers targeted for retaliation suffer from reduced hours or even job loss. For instance, a survey conducted at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that one in eight workers perceived possible retaliatory actions by their employers against colleagues who raised health and safety concerns. Furthermore, Black workers were more than twice as likely as white workers to experience such possible retaliation. This sobering statistic is a stark reminder of the added layers of discrimination and economic insecurity that BIPOC workers have to navigate when advocating for better working conditions and wages.

The time to enact strong policy supporting historically disadvantaged workers is now. Advancing racial equity and racial justice is a focus for the Biden-Harris Administration, and the political and social will is evident. The day one Biden-Harris Administration Executive Order on Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government seeks to develop policies designed to advance equity for all, including people of color and others who have been historically underinvested in, marginalized, and adversely affected by persistent poverty and inequality. Additionally, the establishment of the White House is a significant development. Led by Vice-President Kamala Harris and Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh, the Task Force aims to empower workers to organize and negotiate with their employers through federal government policies, programs, and practices.

A key focus for the Task Force is to increase worker power in underserved communities by examining and addressing the challenges faced by workers in jurisdictions with restrictive labor laws, marginalized workers, and workers in certain industries. The Task Force is well-timed, given the increased support for workers’ rights demonstrated through the record-high number of petitions filed with the National Labor Relations Board and the rise in strikes over the past two years. The Task Force’s approach to empowering workers and supporting their ability to organize and negotiate through federal government policies and programs offers a promising opportunity to address the unique challenges faced by BIPOC workers in unionization efforts.

The National Bargaining in Good Faith Fund is a critical initiative that can help level the playing field by providing financial assistance to workers facing opposition from employers who refuse to engage in good-faith bargaining, thereby expanding access to unions for Black, Indigenous, and other people of color. In addition, the proposed initiative would reinforce Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) policies regarding employer discrimination and retaliation. The Bargaining in Good Faith Fund will provide direct payments to workers whose employers have retaliated against them for engaging in union organizing activities. The initiative also includes monitoring cases where a violation has occurred against workers involved in union organization and connecting their bargaining unit with relevant resources to support their efforts. With the backing of the Task Force, the fund could make a significant difference in the lives of workers facing barriers to organizing.

Plan of Action

While the adoption of a policy like the Bargaining in Good Faith Fund is unprecedented at the federal level, we draw inspiration from successful state-level initiatives aimed at improving worker well-being. Two notable examples are initiatives enacted in California and New York, where state lawmakers provided temporary monetary assistance to workers affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Taking a cue from these successful programs, we can develop federal policies that better support workers, especially those belonging to historically disadvantaged groups.

The successful implementation of worker-led, union-organized, and community-led strike assistance funds, as well as similar initiatives for low-wage, app-based, and automation-adjacent workers, indicates that the Bargaining in Good Faith Fund has strong potential for success. For example, the Coworker Solidarity Fund provides legal, financial, and strategic support for worker-activists organizing to improve their companies, while the fund invests in ecosystems that increase worker power and improve economic livelihoods and social conditions across the U.S. South.

New York state lawmakers have also set a precedent with their transformative Excluded Workers Fund, which provided direct financial support to workers left out of pandemic relief programs. The $2.1 billion Excluded Workers Fund, passed by the New York state legislature and governor in April 2021, was the first large-scale program of its kind in the country. By examining and building on these successes, we can develop federal policies that better support workers across the country.

A national program requires multiple funding methods, and several mechanisms have been identified to establish the National Bargaining in Good Faith Fund. First, existing policy needs to be strengthened, and companies violating labor laws should face financial consequences. The labor law violation tax, which could be a percentage of a company’s profits or revenue, would be directed to the Bargaining in Good Faith Fund. Additionally, penalties could be imposed on companies that engage in retaliatory behavior, and the funds generated could also be directed to the Bargaining in Good Faith Fund. New legislation from Congress is required to enforce existing federal policy.

Second, as natural allies in the fight to safeguard workers’ rights, labor unions should allocate a portion of their dues toward the fund. By pooling their resources, a portion of union dues could be directed to the federal fund.

Third, a portion of the fees paid into the federal unemployment insurance program should be redirected to Bargaining in Good Faith Fund.

Fourth, existing funding for worker protections, currently siloed in agencies, should be reallocated to support the Bargaining in Good Faith Fund more effectively. To qualify for the fund, workers receiving food assistance and/or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families benefits should be automatically eligible once the NLRB and the EEOC recognize the instance of retaliation. Workers who are not eligible could apply directly to the Fund through a state-appointed agency. This targeted approach aims to support those who face significant barriers to accessing resources and protections that safeguard their rights and well-being due to historical labor exploitation and discrimination.

Several federal agencies could collaborate to oversee the Bargaining in Good Faith Fund, including the Department of Labor, the EEOC, the Department of Justice, and the NLRB. These agencies have the authority to safeguard workers’ welfare, enforce federal laws prohibiting employment discrimination, prosecute corporations that engage in criminal retaliation, and enforce workers’ rights to engage in concerted activities for protection, such as organizing a union.

Conclusion

The federal government has had a policy of supporting worker organizing and collective bargaining since the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935. However, the federal government has not fully implemented its policy over the past 86 years, resulting in negative impacts on BIPOC workers, who face systemic racism in the unionization process and on the job. Additionally, rapid technological advances have resulted in the automation of tasks and changes in the labor market that disproportionately affect workers of color. Consequently, the United States is likely to see an increase in wealth inequality over the next two decades.

The Biden-Harris Administration can act now to promote racial equity by establishing a National Bargaining in Good Faith Fund to support historically disadvantaged workers in unionization efforts. Because this is a pressing issue, a feasible short-term solution is to initiate a pilot program over the next 18 months. It is imperative to establish a policy that acknowledges and addresses the historical disadvantage experienced by these workers and supports their efforts to attain economic equity.

For example, in 2019, the city of Evanston, Illinois, established a fund to provide reparations to Black residents who can demonstrate that they or their ancestors have been affected by discrimination in housing, education, and employment. The fund is financed by a three percent tax on the sale of recreational marijuana and is intended to provide financial assistance for housing, education, and other needs.

Another example is the proposed H.R. 40 bill in the U.S. Congress that aims to establish a commission to study and develop proposals for reparations for African Americans who are descendants of slaves and who have been affected by slavery, discrimination, and exclusion from opportunities. The bill aims to study the impacts of slavery and discrimination and develop proposals for reparations that would address the lingering effects of these injustices, including the denial of education, housing, and other benefits.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, was challenged in court but upheld by the Supreme Court in 1964.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, which aimed to eliminate barriers to voting for minorities, was challenged in court several times over the years, with the Supreme Court upholding key provisions in 1966 and 2013, but striking down a key provision in 2013.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968, which banned discrimination in housing, was challenged in court and upheld by the Supreme Court in 1968.

The Affirmative Action policies, which aimed to increase the representation of minorities in education and the workforce, have been challenged in court multiple times over the years, with the Supreme Court upholding the use of race as a factor in college admissions in 2016.

Despite court challenges, policymakers must persist in bringing forth solutions to address racial equity as many complex federal policies aimed at promoting racial equity have been challenged in court over the years, not just on constitutional grounds.

Ensuring Fairness in Federal Procurement and Use of Artificial Intelligence

In pursuit of lower costs and improved decision-making, federal agencies have begun to adopt artificial intelligence (AI) to assist in government decision-making and public administration. As AI occupies a growing role within the federal government, algorithmic design and evaluation will increasingly become a key site of policy decisions. Yet a 2020 report found that almost half (47%) of all federal agency use of AI was externally sourced, with a third procured from private companies. In order to ensure that agency use of AI tools is legal, effective, and equitable, the Biden-Harris Administration should establish a Federal Artificial Intelligence Program to govern the procurement of algorithmic technology. Additionally, the AI Program should establish a strict data collection protocol around the collection of race data needed to identify and mitigate discrimination in these technologies.

Researchers who study and conduct algorithmic audits highlight the importance of race data for effective anti-discrimination interventions, the challenges of category misalignment between data sources, and the need for policy interventions to ensure accessible and high-quality data for audit purposes. However, inconsistencies in the collection and reporting of race data significantly limit the extent to which the government can identify and address racial discrimination in technical systems. Moreover, given significant flexibility in how their products are presented during the procurement process, technology companies can manipulate race categories in order to obscure discriminatory practices.

To ensure that the AI Program can evaluate any inequities at the point of procurement, the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) National Science and Technology Council Subcommittee on Equitable Data should establish guidelines and best practices for the collection and reporting of race data. In particular, the Subcommittee should produce a report that identifies the minimum level of data private companies should be required to collect and in what format they should report such data during the procurement process. These guidelines will facilitate the enforcement of existing anti-discrimination laws and help the Biden-Harris Administration pursue their stated racial equity agenda. Furthermore, these guidelines can help to establish best practices for algorithm development and evaluation in the private sector. As technology plays an increasingly important role in public life and government administration, it is essential not only that government agencies are able to access race data for the purposes of anti-discrimination enforcement—but also that the race categories within this data are not determined on the basis of how favorable they are to the private companies responsible for their collection.

Challenge and Opportunity

Research suggests that governments often have little information about key design choices in the creation and implementation of the algorithmic technologies they procure. Often, these choices are not documented or are recorded by contractors but never provided to government clients during the procurement process. Existing regulation provides specific requirements for the procurement of information technology, for example, security and privacy risks, but these requirements do not account for the specific risks of AI—such as its propensity to encode structural biases. Under the Federal Acquisition Regulation, agencies can only evaluate vendor proposals based on the criteria specified in the associated solicitation. Therefore, written guidance is needed to ensure that these criteria include sufficient information to assess the fairness of AI systems acquired during procurement.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) defines minimum standards for collecting race and ethnicity data in federal reporting. Racial and ethnic categories are separated into two questions with five minimum categories for race data (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and White) and one minimum category for ethnicity data (Hispanic or Latino). Despite these standards, guidelines for the use of racial categories vary across federal agencies and even across specific programs. For example, the Census Bureau classification scheme includes a “Some Other Race” option not used in other agencies’ data collection practices. Moreover, guidelines for collection and reporting of data are not always aligned. For example, the U.S. Department of Education recommends collecting race and ethnicity data separately without a “two or more races” category and allowing respondents to select all race categories that apply. However, during reporting, any individual who is ethnically Hispanic or Latino is reported as only Hispanic or Latino and not any other race. Meanwhile, any respondent who selected multiple race options is reported in a “two or more races” category rather than in any racial group with which they identified.

These inconsistencies are exacerbated in the private sector, where companies are not uniformly constrained by the same OMB standards but rather covered by piecemeal legislation. In the employment context, private companies are required to collect and report on demographic details of their workforce according to the OMB minimum standards. In the consumer lending setting, on the other hand, lenders are typically not allowed to collect data about protected classes such as race and gender. In cases where protected class data can be collected, these data are typically considered privileged information and cannot be accessed by the government. In the case of algorithmic technologies, companies are often able to discriminate on the basis of race without ever explicitly collecting race data by using features or sets of features that act as proxies for protected classes. Facebook’s advertising algorithms, for instance, can be used to target race and ethnicity without access to race data.

Federal leadership can help create consistency in reporting to ensure that the government has sufficient information to evaluate whether privately developed AI is functioning as intended and working equitably. By reducing information asymmetries between private companies and agencies during the procurement process, new standards will bring policymakers back into the algorithmic governance process. This will ensure that democratic and technocratic norms of agency rule-making are respected even as privately developed algorithms take on a growing role in public administration.

Additionally, by establishing a program to oversee the procurement of artificial intelligence, the federal government can ensure that agencies have access to the necessary technical expertise to evaluate complex algorithmic systems. This expertise is crucial not only during the procurement stage but also—given the adaptable nature of AI—for ongoing oversight of algorithmic technologies used within government.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Establish a Federal Artificial Intelligence Program to oversee agency procurement of algorithmic technologies.

The Biden-Harris Administration should create a Federal AI Program to create standards for information disclosure and enable evaluation of AI during the procurement process. Following the two-part test outlined in the AI Bill of Rights, the proposed Federal AI Program would oversee the procurement of any “(1) automated systems that (2) have the potential to meaningfully impact the American public’s rights, opportunities, or access to critical resources or services.”

The goals of this program will be to (1) establish and enforce quality standards for AI used in government, (2) enforce rigorous equity standards for AI used in government, (3) establish transparency practices that enable public participation and political accountability, and (4) provide guidelines for AI program development in the private sector.

Recommendation 2. Produce a report to establish what data are needed in order to evaluate the equity of algorithmic technologies during procurement.

To support the AI Program’s operations, the OSTP National Science and Technology Council Subcommittee on Equitable Data should produce a report to establish guidelines for the collection and reporting of race data that balances three goals: (1) high-quality data for enforcing existing anti-discrimination law, (2) consistency in race categories to reduce administrative burdens and curb possible manipulation, and (3) prioritizing the needs of groups most affected by discrimination. The report should include opportunities and recommendations for integrating its findings into policy. To ensure the recommendations and standards are instituted, the President should direct the General Services Administration (GSA) or OMB to issue guidance and request that agencies document how they will ensure new standards are integrated into future procurement vehicles. The report could also suggest opportunities to update or amend the Federal Acquisition Regulations.

High-Quality Data

The new guidelines should make efforts to ensure the reliability of race data furnished during the procurement process. In particular:

- Self-identification should be used whenever possible to ascertain race. As of 2021, Food and Nutrition Service guidance recommends against the use of visual identification based on reliability, respect for respondents’ dignity, and feedback from Child and Adult Care Food Program) and Summer Food Service Program participants.

- The new guidelines should attempt to reduce missing data. People may be reluctant to share race information for many legitimate reasons, including uncertainty about how personal data will be used, fear of discrimination, and not identifying with predefined race categories. These concerns can severely impact data quality and should be addressed to the extent possible in the OMB guidelines. New York’s state health insurance marketplace saw a 20% increase in response rate for race by making several changes to the way they collect data. These changes included explaining how the data would be used and not allowing respondents to leave the question blank but instead allowing them to select “choose not to answer” or “don’t know.” Similarly, the Census Bureau found that a single combined race and ethnicity question improved data quality and consistency by reducing the rate of “some other race,” missing, and invalid responses as compared with two separate questions (one for race and one for ethnicity).

- The new guidelines should follow best practices established through rigorous research and feedback from a variety of stakeholders. In June 2022, the OMB announced a formal review process to revise Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. While this review process is intended for the revision of federal data requirements, its findings can help inform best practices for collection and reporting requirements for nongovernmental data as well.

Consistency in Data Reporting

Whenever possible and contextually appropriate, the guidelines for data reporting should align with the OMB guidelines for federal data reporting to reduce administrative burdens. However, the report may find that other data is needed that goes beyond the OMB guidelines for the evaluation of privately developed AI.

Prioritizing the Needs of Affected Groups

In their Toolkit for Centering Racial Equity Throughout Data Integration, the Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy group at the University of Pennsylvania identifies best practices for ensuring that data collection serves the groups most affected by discrimination. In particular, this toolkit emphasizes the need for strong privacy protections and stakeholder engagement. In their final report, the Subcommittee on Equitable Data should establish protocols to secure data and for carefully considered role-based access to it.

The final report should also engage community stakeholders in determining which data should be collected and establish a plan for ongoing review that engages with relevant stakeholders, prioritizing affected populations and racial equity advocacy groups. The report should evaluate the appropriate level of transparency in the AI procurement process, in particular, trade-offs between desired levels of transparency and privacy.

Conclusion

Under existing procurement law, the government cannot outsource “inherently governmental functions.” Yet key policy decisions are embedded within the design and implementation of algorithmic technology. Consequently, it is important that policymakers have the necessary resources and information throughout the acquisition and use of procured AI tools. A Federal Artificial Intelligence Program would provide expertise and authority within the federal government to assess these decisions during procurement and to monitor the use of AI in government. In particular, this would strengthen the Biden-Harris Administration’s ongoing efforts to advance racial equity. The proposed program can build on both long-standing and ongoing work within the federal government to develop best practices for data collection and reporting. These best practices will not only ensure that the public use of algorithms is governed by strong equity and transparency standards in the public sector but also provide a powerful avenue for shaping the development of AI in the private sector.

Scaling High-Impact Solutions with a Market-Shaping Mechanism for Global Health Supply Chains

Summary

Congress created the Development Finance Corporation (DFC) to finance private sector solutions to the most critical challenges facing the developing world. In parallel, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has committed to engaging the private sector and shifting more resources to local market providers to further the impact of U.S. foreign aid dollars.

USAID is on the verge of awarding its largest-ever suite of foreign aid contracts, totaling $17 billion over the next ten years and comprising nine awards as part of the “NextGen Global Health Supply Chain” (GHSC) contracts. This is a continuation of previous global health supply chain contracts that date back to the 1960s that have grown exponentially in total value but have underperformed and not meaningfully transitioned responsibility for deployment to low- and middle-income country (LMIC) governments and LMIC-based organizations.

Now is the time for USAID and the DFC to pilot new ways of working with the private sector that put countries on a path to high-impact, sustainable development that builds markets.

We propose that USAID set aside $300 million of the overall $17 billion package – or less than 2 percent of the overall value – to create a Supply Chain Commercialization Fund to demonstrate a new way of working with the private sector and administering U.S. foreign aid. USAID and the DFC can deploy the Commercialization Fund to:

- Create and finance instruments that pay for results against certain well-defined success metrics, such as on-time delivery;

- Provide blended financing to expand the footprint and capabilities of established LMIC-based healthcare and logistics service providers that may require additional working capital to grow their presence and/or expand operations; and

- If successful, invite other countries to participate in this model, with the potential for replication to other geographies and sectors where there are robust private sector markets, such as in agriculture, water, and power.

USAID and the DFC can pilot this new model in three countries where there are already thriving and well-established private markets, like Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria.

Challenge and Opportunity

The world is facing an unprecedented concurrence of crises: pandemics, war, rising food insecurity, and a rapidly warming climate. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are deeply affected, with many having lost decades’ worth of gains made toward the Sustainable Development Goals in only a few short years. We now face the dual tasks of regaining lost ground while ensuring those gains are more durable and lasting than before.

The Biden Administration recognizes this pivotal moment in its new U.S. Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa. The Strategy acknowledges the continent’s growing importance to U.S. global priorities and lays out a 21st-century partnership to contribute to a strong and sustainable global economy, foster new technology and innovation, and ultimately support the long-envisioned transition from donor-driven to country-driven programs. This builds on past U.S. foreign aid initiatives led by administrations of both political parties, including Administrator Mark Green’s Journey to Self Reliance and Administrator Raj Shah’s USAID Forward initiatives. Rather than creating a new flagship program, the U.S. Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa focuses on improved implementation and better integration of existing initiatives to supercharge results. Such aims were echoed repeatedly during the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit in December 2022.

To realize a new vision for U.S.-Africa partnerships, the Biden Administration should more effectively fuse the work of USAID and the DFC. A key policy rationale for the DFC’s creation in 2018 was to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and growing economic influence in frontier markets. By combining this investment arm with USAID’s programmatic work, Congress hoped to accelerate major development impact. However numerous mismatches between USAID and DFC priorities have limited and sometimes actively undermined Congress’ goals. In the worst cases, USAID dollars have been used to pay international aid contractors to perform work in places where existing market providers could. Rather than bolster markets, this can distort them.

This memo lays out a new approach to development rooted in better USAID-DFC collaboration, where the work of both agencies contributes to the commercialization of sectors ready to transition from aid-dependent models to commercial and trade-enabled ones. In these sectors, USAID should work to phase out its international aid contractor-led model and instead scale up the work of existing market participants, including by paying them for results. This set of recommendations also advances USAID priorities outlined in the Agency’s new Acquisition and Assistance Strategy and proposed implementation plan, as well as USAID’s policy framework, which each call for working more closely with the private sector and transitioning to more pay-for-performance models.

The global health supply chain is ideal for USAID and the DFC to test the concept of a commercialization fund because of the sector’s discrete metrics and robust existing logistics companies. Investing in cheaper, more efficient evidence-driven solutions in a competitive marketplace can improve aid effectiveness and better serve target populations with the health goods like PPE, vaccines, and medications they need. This sector receives USAID’s largest contracts, with the Agency spending more than $1B each year on procurement and logistics to get the right health products to the right place, at the right time, and in the right condition across dozens of countries. In the logistics space, only about 25%1 of USAID’s expenditure supports directly distributing commodities to health facilities in target nations; the other 75% is spent on fly-in contractors who oversee that work. Despite this premium, on-time and in-full distribution rates often miss their targets, and stockouts are still common, according to USAID’s reports and audits.2

A Commercialization Fund can directly address policy goals such as localization or private-sector engagement by building resilient health supply chains through a marketplace of providers that ensures patients and providers access the supplies they need on time. In addition to improving sustainability and results and cutting costs, a well-structured Commercialization Fund can improve global health donor coordination, crowd-in new investments from other funders and philanthropy that want to pay for outcomes, and hasten the transition from donor-led aid models to country-led ones.

Plan of Action

USAID should create the Global Health Supply Chain Commercialization Fund, a $300 million initiative to purchase commercial supply chain services directly from operators, based on performance or results. USAID should pilot using the Commercialization Fund to pay providers in three countries where there are already thriving and well-established private logistics markets, such as Kenya, Nigeria, and Ghana. In these countries, dozens of logistics and healthcare providers operate at scale, serving millions of people.

With an initial focus on health logistics, USAID should use $300 million from its yet-to-be-awarded suite of $17 billion NextGen Global Health Supply Chain contracts to provide initial funding for the Commercialization Fund. If successful, the Commercialization Fund will create an open playing field for competition and crowd-in high-impact technology, innovation, and more market-based actors in global health supply chains. This fund will build upon existing efforts across the Agency to identify, incubate, and catalyze innovations from the private sector.

To quickly stand up this Commercialization Fund and select vendors, Administrator Power should utilize her “impairment authority.” Though typically applied to emergencies, the “impairment authority” has been used previously during global health events like the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ebola response and could be used to achieve a specific policy priority such as localization and/or transforming the way USAID administers its global health supply chains. (See FAQ for more information regarding this authority).

The creation of this Fund, which can be fully budget-neutral, requires the following steps:

Step 1. USAID and DFC take administrative action to design and capitalize the $300 million, five-year, cross-cutting, and disease-agnostic Supply Chain Commercialization Fund. A joint aid effectiveness “tiger team” within USAID and the DFC should:

- Spearhead the design and implementation framework for the Fund and stipulate clear, standardized key performance indicators (KPIs) to indicate significant improvements in health supply chain performance in countries where the Commercialization Fund operates.

- Select three countries to adopt the Commercialization Fund, chosen in coordination with overseas USAID Missions and the DFC. Countries should be selected and prioritized based on factors such as analyses of health systems’ needs, the existence of local supply chain service providers, and countries’ desire to manage more of their own health supply chains. As a follow-on to the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit, we recommend USAID and the DFC direct initial Commercialization Fund funds to support activities in Africa where there are already thriving and well-established private markets such as Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria.

- Set pricing for each KPI and product in each Commercialization Fund country market. For example, pay-for-performance indicators could include percent of on-time deliveries. USAID and the DFC should set high expectations for performance, such as 95+ percent on-time delivery, especially in geographies where existing market providers can already deliver against similarly rigorous targets in other sectors. USAID bureaus and missions, partner country governments, and in-country private sector healthcare and logistics leaders, as well as supply chain and innovative financing experts, should be consulted during this process.

- Choose funding mechanisms that pay for results (see Step 2 for details).

- Provide blended financing to vendors that may need additional resources to scale their footprint and/or increase their capabilities.

- Select a third-party auditor(s) to audit the results upon which providers are paid.

Step 2: USAID structures financial instruments to pay service providers against results delivered in selected Commercialization Fund countries

USAID should pay Commercialization Fund providers to deliver results, consistent with the KPIs set in Step 1 by the joint aid effectiveness “tiger team.” Pay-for-performance contracts can also provide incentives and/or price assurances for service providers to build infrastructure and expand to areas they don’t traditionally serve.

Structuring pay-for-performance tools will favor providers that can demonstrate their ability to deliver superior and/or more cost-effective results relative to status quo alternatives. Preference should be given to providers that are operational in the target country where there is existing market demand for their services, as evidenced by factors such as whether the host country government, national health insurance program, or consumers already pay for the providers’ services. USAID should work with the host country government(s) to select vendors to ensure strong country buy-in.

To maximize performance and competition, USAID should explicitly not use cost-reimbursable payment models that reimburse for effort and optimize for compliance and reporting. The red tape associated with these awards is so cumbersome that non-traditional USAID service providers cannot compete.3

USAID should consider using the following pay-for-performance modalities:

- Fixed-price, milestone-based awards that trigger payment when a service provider meets certain milestones, such as for each delivery made with a 95% on-time rate and with little-to-no product spoilage or wastage. Using fixed-price grants and contracts in this way can effectively make them function as forward-contracts that provide firms with advanced price assurances that, as long as they continue to deliver against predetermined objectives, the U.S. Government will pay. Fixed-amount grants and contracts are easier for non-traditional USAID partners to apply for and manage than more commonly-used “cost reimbursement” awards that reimburse vendors for time, materials, and effort and have enormous compliance costs. Because pay-for-results awards only pay upon proof of milestones achieved, they also increase accountability for the U.S. taxpayer.

As USAID’s proposed acquisition and assistance implementation plan points out, “‘pay-for-result’ awards (such as firm fixed price contracts or fixed amount awards) can substantially reduce burdens on [contracting officers] and financial management staff as well as open doors for technically strong local partners unable to meet U.S. Government financial standards.” - Innovation Incentive Awards (IIAs) that pay providers retroactively after they meet certain predetermined results criteria. This award authority, expanded by Congress in December 2022, enables USAID to pre-publish its willingness to pay up to $100,000 for certain well-defined, predetermined results; then pay retroactively once a service provider can demonstrate it met the intended objective.

Unlike a fixed-price award, which establishes a longer-term relationship between USAID and the selected vendor, USAID can use the IIA modality to provide vendors with one-time spot payments. However, USAID could still use this payment modality to move more money at scale provided a vendor(s) can successfully meet multiple objectives (e.g. USAID could make multiple $100,000 payments for multiple on-time deliveries). - USAID could pursue Other Transaction Authority (OTA) opportunities without additional authorization, but the Agency may also benefit from consultation with the White House, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and The Office of Information & Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), as well as Congress, to secure additional authorities or waivers to disburse Commercialization Fund resources using innovative pay-for-results tools, including OTA, which other federal agencies have used to invite greater private sector participation from nontraditional U.S. Government partners.

Step 3: USAID and DFC should provide countries with additional technical assistance resources to create intentional pathways for selected countries to contribute to the design and management of program implementation.

To ensure these initiatives support countries’ needs and facilitate country ownership and increase voice, USAID should also consider establishing a supra-agency advisory board to support the success of the Commercialization Fund modeled after DFC’s Africa Investment Advisor Program that seats a panel of experts that can continually advise both agencies on strategic priorities, key risks, and award structure, etc. It could also model elements of the Millennium Challenge Corporation’s compact model to ensure participating countries have a hand in the design of relevant aspects of the Commercialization Fund.

USAID should additionally provide participating Commercialization Fund countries with Technical Assistance resources to ensure that host country governments can eventually take on larger management responsibilities regarding the administration of Commercialization Fund pay-for-performance contracts.

Step 4: As needed, USAID and the DFC should collaborate to provide sustainable pathways for blended financing that allows existing market providers to access working capital to scale their footprint.

While the DFC and USAID have worked on blended finance deals in the past, the Biden Administration should explicitly direct the two agencies to work together to identify and scale the footprints and capabilities of logistics and healthcare providers in targeted Commercialization Fund countries.

Many of the existing healthcare and logistics providers that could potentially manage a greater share of global health supply chains could need additional financing to expand their operations, increase working capital, or grow their capabilities, but they often find themselves in a chicken or the egg problem to secure financing from financial institutions like the DFC.

Traditional banks and DFC investment officers often consider these companies to be potentially risky investments because their revenue in health supply chains is not assured, especially because one of the largest healthcare payers in many LMICs is the U.S. Government, but USAID (and other global health donors) have historically funded international aid contractors to manage countries’ health supply chains, not local firms or alternative service providers. However, at the same time, USAID and other donors have not relied more on existing logistics service providers to manage health supply chains because many of these providers do not operate at the scale of larger international aid contractors.

To break this cycle, and to enable the DFC and other lenders to offer better financing terms to firms that need it to grow their capabilities or secure working capital, USAID could provide identified firms with more blended finance deals, including guaranteed eligibility to receive pay-for-performance revenue using the funding modalities described above. It could also provide unrestricted early-stage and/or phased funding to cover operational costs associated with working with the U.S. Government.

Increasing available credit to firms via the DFC and using a USAID pay-for-performance contract as collateral would also enhance firms’ overall ability to raise credit from other sources. This assurance, in turn, reduces the cost of capital for receiving firms, resulting in more significant, impactful investments from private capital in the construction of other supply chain infrastructure, including warehouses, IT systems, and shipping fleets.

Step 5: Pending success, USAID and the DFC should replicate the Commercialization Fund in additional countries. Congress should codify the Commercialization Fund into law and authorize larger-scale commercialization funds in additional geographies and sectors as part of the BUILD Act reauthorization in 2025.

While this initial Commercialization Fund will focus on building sustainable, high-performing global health supply chains in three LMICs, the same blueprint could be leveraged in other countries and in other sectors where there are robust private sectors, such as in food or power.

- Congress should require USAID and DFC to report overall Commercialization Fund performance every six months for a minimum of three years.

- If the Commercialization Fund proves successful after the first year, USAID and the DFC should proactively invite other countries to participate to expand this model to other geographies, where appropriate.

- If successful with healthcare supply chains, the Commercialization Fund should also be expanded to cover additional sectors and geographies and included in the BUILD Act 2025 reauthorization.

Conclusion

Continued reliance on traditional aid in commercial-ready sectors contributes to market failures, limits local agency, and minimizes the opportunity for sustainable impact.

As a team of researchers from the Carnegie Endowment’s Africa Program pointed out on the heels of the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit, “A persistent humanitarian approach to Africa…creates pathologies of unhelpful dependency, insufficient focus on the drivers of inclusive growth, and perverse incentives for the continuation of the status quo by a small coterie of connected beneficiaries.” Those researchers identified 18 new initiatives announced at the Summit supported with public money in economic sectors that can facilitate trade, investments, entrepreneurship, and jobs creation, signaling an unprecedented readiness in this Administration to prioritize trade alongside aid.

The Commercialization Fund outlined in this memo — a market-shaping mechanism designed to correct market failures that conventional aid models can perpetuate — has the potential to become a model for accelerating the transition of other key economic sectors away from the status quo and toward innovation, investment, impact, and long-term sustainability.

The global health supply chain is an ideal sector for USAID and the DFC to test the concept of a Commercialization Fund:

First, virtually every industry relies on robust supply chains to get goods around the world. There are dozens of African logistics companies that deliver goods to last-mile communities every day, including hard-to-transport items that require cold-chain storage like perishable goods and vaccines. These firms can deliver health commodities faster, cheaper, and more sustainably than traditional aid implementers, especially to last-mile communities.

Second, health supply chain performance metrics are relatively straightforward and easy to define and measure. As a result, USAID can facilitate managed competition that pays multiple logistics providers against rigorous, predetermined pay-for-performance indicators. To provide additional accountability to the taxpayer, it could withhold payment for factors such as health commodity spoilage.

Third, global health receives the largest share of USAID’s overall budget, but a significant share of those resources pay for contractor overhead and profit margin, so there is considerable opportunity to re-allocate those resources to create a pay-for-performance Supply Chain Commercialization Fund. Only about 25 percent of USAID’s in-country logistics expenditures pay for the actual work of distributing commodities to health facilities in target nations; the other 75 percent pays for larger aid contractors’ overhead, management, and other costs. Despite this premium, on-time and in-full distribution rates often miss their targets, and stockouts are still a common occurrence, according to USAID’s reports and audits.

Investing in cheaper, more efficient, and effective operators in a competitive marketplace can improve aid effectiveness and better serve target populations with essential healthcare. A Commercialization Fund can directly address policy goals of “progress over programs” by building resilient health supply chains that, once and for all, ensure patients and providers get the supplies they need on time. Since local providers can typically provide services faster, cheaper, and more sustainably than international aid contractors, transitioning to models that pay for results with fees set to prevailing local rates can also advance USAID’s localization priorities and bolster markets rather than distort them.

The administrator could activate her unique “impairment authority” to fashion the scope of procurement competitions at will. The fundamental concept is that if full and open competition for a contract or set of contracts—the normal process followed to fulfill the U.S. Government’s requirements—would impair foreign assistance objectives, then the administrator can divide procurements falling under the relevant category to advance an objective like localization. This authority, which is codified in USAID’s core authorizing legislation (the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended), along with a formal U.S. Government regulation, was previously used to quickly procure during Iraq reconstruction, Afghanistan humanitarian needs, and the Ebola and COVID-19 responses. While “impairment authority” may be an untested pathway for global health supply chains, it does offer the administrator a viable pathway to launch the Fund and ensure high-impact operators are receiving USAID contracts while continuing to consult with Congress to codify the Fund’s activities long-term. The administrator’s extraordinary “impairment authority” comes from 636(a)(3) of the Foreign Assistance Act and AIDAR (the USAID-specific Supplement to the FAR) Section 706.302-70 “Impairment of foreign aid programs.” See especially 706.302-70(a)(3)(ii).

Many LMIC governments increasingly embrace technological solutions outside of traditional aid models because they know technology can lead to greater efficiencies, support job creation and economic development, and drive improved results for their populations. Sustaining a marketplace within a country or region is an advantage to supporting new entrants and existing firms in the sector. The impact of these companies’ services can also be scaled via pay-for-results models and domestic government spending, as the firms that deliver superior performance will rise to the top and continue to be demanded, and those that do not meet established metrics will not be contracted with again.

Supply chain and innovative financing experts who deeply understand the challenges plaguing global health supply chains should be consulted to design successful pay-for-results vehicles. These individuals should support the USAID/DFC tiger team to support the design and implementation framework for the Commercialization Fund, define KPIs, set appropriate pricing, and select auditors. USAID Missions and local governments will be most familiar with the unique supply chain challenges within their jurisdictions and should work alongside supply chain experts to define the desired supply chain results for the Commercialization Funds in their countries.

Through the Commercialization Fund, USAID will contract any supply chain service provider that can meet exceptionally high performance targets set by the Agency. USAID will increase its volume of business with providers that consistently hit relevant targets over consecutive months. Operators will be paid based on their performance under these contracts, providing them with predictable and consistent cash flows to grow their businesses and reach system-wide scale and impact. Based on these anticipated cash flows, DFC will be well-positioned with equity investments and able to provide upfront and working capital financing.