Make government-funded hardware open source by default

While scientific publications and data are increasingly made publicly accessible, designs and documentation for scientific hardware — another key output of federal funding and driver of innovation — remain largely closed from view. This status quo can lead to redundancy, slowed innovation, and increased costs. Existing standards and certifications for open source hardware provide a framework for bringing the openness of scientific tools in line with that of other research outputs. Doing so would encourage the collective development of research hardware, reduce wasteful parallel creation of basic tools, and simplify the process of reproducing research. The resulting open hardware would be available to the public, researchers, and federal agencies, accelerating the pace of innovation and ensuring that each community receives the full benefit of federally funded research.

Federal grantmakers should establish a default expectation that hardware developed as part of federally supported research be released as open hardware. To retain current incentives for translation and commercialization, grantmakers should design exceptions to this policy for researchers who intend to patent their hardware.

Details

Federal funding plays an important role in setting norms around open access to research. The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP)’s recent Memorandum Ensuring Free, Immediate, and Equitable Access to Federally Funded Research makes it clear that open access is a cornerstone of a scientific culture that values collaboration and data sharing. OSTP’s recent report on open access publishing further declares that “[b]road and expeditious sharing of federally funded research is fundamental for accelerating discovery on critical science and policy questions.”

These efforts have been instrumental in providing the public with access to scientific papers and data — two of the foundational outputs of federally funded research. Yet hardware, another key input and output of science and innovation, remains largely hidden from view. To continue the move towards an accessible, collaborative, and efficient scientific enterprise, public access policies should be expanded to include hardware. Specifically, making federally funded hardware open source by default would have a number of specific and immediate benefits:

Reduce Wasteful Reinvention. Researchers are often forced to develop testing and operational hardware that supports their research. In many cases, unbeknownst to those researchers, this hardware has already been developed as part of other projects by other researchers in other labs. However, since that original hardware was not openly documented and licensed, subsequent researchers are not able to learn from and build upon this previous work. The lack of open documentation and licensing is also a barrier to more intentional, collaborative development of standardized testing equipment for research.

Increase Access to Information. As the OSTP memo makes clear, open access to federally funded research allows all Americans to benefit from our collective investment. This broad and expeditious sharing strengthens our ability to be a critical leader and partner on issues of open science around the world. Immediate sharing of research results and data is key to ensuring that benefit. Explicit guidance on sharing the hardware developed as part of that research is the next logical step towards those goals.

Alternative Paths to Recognition. Evaluating a researcher’s impact often includes an assessment of the number of patents they can claim. This is in large part because patents are easy to quantify. However, this focus on patents creates a perverse incentive for researchers to erect barriers to follow on study even if they have no intention of using patents to commercialize their research. Encouraging researchers to open source the hardware developed as part of their research creates an alternative path to evaluate their impact, especially as those pieces of open source hardware are adopted and improved by others. Uptake of researchers’ open hardware could be included in assessments on par with any patented work. This path recognizes the contribution to a collective research enterprise.

Verifiability. Open access to data and research are important steps towards allowing third parties to verify research conclusions. However, these tools can be limited if the hardware used to generate the data and produce the research are not themselves open. Open sourcing hardware simplifies the process of repeating studies under comparable conditions, allowing for third-party validation of important conclusions.

Recommendations

Federal grantmaking agencies should establish a default presumption that recipients of research funds make hardware developed with those funds available on open terms. This policy would apply to hardware built as part of the research process, as well as hardware that is part of the final output. Grantees should be able to opt out of this requirement with regards to hardware that is expected to be patented; such an exception would provide an alternative path for researchers to share their work without undermining existing patent-based development pathways.

To establish this policy, OSTP should conduct a study and produce a report on the current state of federally funded scientific hardware and opportunities for open source hardware policy.

- As part of the study, OSTP should coordinate and convene stakeholders to discuss and align on policy implementation details — including relevant researchers, funding agencies, U.S. Patent and Trademark Office officials, and leaders from university tech transfer offices.

- The report should provide a detailed and widely applicable definition of open source hardware, drawing on definitions established in the community — in particular, the definition maintained by the Open Source Hardware Association, which has been in use for over a decade and is based on the widely recognized definition of open source software maintained by the Open Source Initiative.

- It should also lay out a broadly acceptable policy approach for encouraging open source by default, and provide guidance to agencies on implementation. The policy framework should include recommendations for:

- Minimally burdensome components of the grant application and progress report with which to capture relevant information regarding hardware and to ensure planning and compliance for making outputs open source

- A clear and well-defined opportunity for researchers to opt out of this mandate when they intend to patent their hardware

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) should issue a memorandum establishing a policy on open source hardware in federal research funding. The memorandum should include:

- The rationale for encouraging open source hardware by default in federally funded scientific research, drawing on the motivation of public access policies for publications and data

- A finalized definition of open source hardware to be used by agencies in policy implementation

- The incorporation of OMB’s Open Source Scientific Hardware Policy, in alignment with the OSTP report and recommendations

Conclusion

The U.S. government and taxpayers are already paying to develop hardware created as part of research grants. In fact, because there is not currently an obligation to make that hardware openly available, the federal government and taxpayers are likely paying to develop identical hardware over and over again.

Grantees have already proven that existing open publication and open data obligations promote research and innovation without unduly restricting important research activities. Expanding these obligations to include the hardware developed under these grants is the natural next step.

Promoting reproducible research to maximize the benefits of government investments in science

Scientific research is the foundation of progress, creating innovations like new treatments for melanoma and providing behavioral insights to guide policy in responding to events like the COVID-19 pandemic. This potential for real-world impact is best realized when research is rigorous, credible, and subject to external confirmation. However, evidence suggests that, too often, research findings are not reproducible or trustworthy, preventing policymakers, practitioners, researchers, and the public from fully capitalizing on the promise of science to improve social outcomes in domains like health and education.

To build on existing federal efforts supporting scientific rigor and integrity, funding agencies should study and pilot new programs to incentivize researchers’ engagement in credibility-enhancing practices that are presently undervalued in the scientific enterprise.

Details

Federal science agencies have a long-standing commitment to ensuring the rigor and reproducibility of scientific research for the purposes of accelerating discovery and innovation, informing evidence-based policymaking and decision-making, and fostering public trust in science. In the past 10 years alone, policymakers have commissioned three National Academies reports, a Government Accountability Office (GAO) study, and a National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) report exploring these and related issues. Unfortunately, flawed, untrustworthy, and potentially fraudulent studies continue to affect the scientific enterprise.

The U.S. government and the scientific community have increasingly recognized that open science practices — like sharing research code and data, preregistering study protocols, and supporting independent replication efforts — hold great promise for ensuring the rigor and replicability of scientific research. Many U.S. science agencies have accordingly launched efforts to encourage these practices in recent decades. Perhaps the most well-known example is the creation of clinicaltrials.gov and the requirements that publicly and privately funded trials be preregistered (in 2000 and 2007, respectively), leading, in some cases, to fewer trials reporting positive results.

More recent federal actions have focused on facilitating sharing of research data and materials and supporting open science-related education. These efforts seek to build on areas of consensus given the diversity of the scientific ecosystem and the resulting difficulty of setting appropriate and generalizable standards for methodological rigor. However, further steps are warranted. Many key practices that could enhance the government’s efforts to increase the rigor and reproducibility of scientific practice — such as the preregistration of confirmatory studies and replication of influential or decision-relevant findings — remain far too rare. A key challenge is the weak incentive to engage in these practices. Researchers perceive them as costly or undervalued given the professional rewards created by the current funding and promotion system, which encourages exploratory searches for new “discoveries” that frequently fail to replicate. Absent structural change to these incentives, uptake is likely to remain limited.

Recommendations

To fully capitalize on the government’s investments in education and infrastructure for open science, we recommend that federal funding agencies launch pilot initiatives to incentivize and reward researchers’ pursuit of transparent, rigorous, and public good-oriented practices. Such efforts could enhance the quality and impact of federally funded research at relatively low cost, encourage alignment of priorities and incentive structures with other scientific actors, and help science and scientists better deliver on the promise of research to benefit society. Specifically, NIH and NSF should:

Establish discipline-specific offices to launch initiatives around rigor and reproducibility

- Use the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke’s Office of Research Quality (ORQ) as a model; similar ORQs would encourage uptake of under-incentivized practices through both internal initiatives and external funding programs.

- To ensure that programs are tailored to fit the priorities of a single disciplinary context, offices should be established within individual NIH institutes and within individual NSF directorates.

Incorporate assessments of transparent and credible research methods into their learning agendas

- Include questions to better understand existing practices, such as “How frequently and effectively do [agency]-funded researchers across disciplines engage in open science practices — e.g., preregistration, publication of null results, and external replication — and how do these practices relate to future funding and research outcomes?”

- Include questions to inform new policies and initiatives, such as “What steps could [agency] take to incentivize broader uptake of open science practices, and which ones — e.g., funding programs, application questions, standards, and evaluation models — are most effective?”

- To answer these questions, solicit feedback from applicants, reviewers, and program officers, and partner with external “science of science management” researchers to design rigorous prospective and retrospective studies; use the information obtained to develop new processes to incentivize and reward open science practices in funded research.

Expand support for third-party replications

- Allocate a consistent proportion of funds to support independent replications of key findings through the use of non-grant mechanisms — e.g., prizes, cooperative agreements, and contracts. The high value placed on scientific novelty discourages such studies, which could provide valuable information about treatment, policy, regulatory approval, or future scientific inquiry. A combination of agency prioritization and public requests for information should be used to identify topics for which additional supportive or contradictory evidence would provide significant societal and/or scientific benefit.

- The NSF, in partnership with an independent third party organization like the Institute for Replication, should run a pilot study to assess the utility of commissioning targeted and/or randomized replication studies for advancing research rigor and informing future funding.

Build capacity for agency use of open science hardware

When creating, using, and buying tools for agency science, federal agencies rely almost entirely on proprietary instruments. This is a missed opportunity because open source hardware — machines, devices, and other physical things whose design has been released to the public so that anyone can make, modify, distribute, and use them — offer significant benefits to federal agencies, to the creators and users of scientific tools, and to the scientific ecosystem.

In scientific work in the service of agency missions, the federal government should use and contribute to open source hardware.

Details

Open source has transformative potential for science and for government. Open source tools are generally lower cost, promote reuse and customization, and can avoid dependency on a particular vendor for products. Open source engenders transparency and authenticity and builds public trust in science. Open source tools and approaches build communities of technologists, designers, and users, and they enable co-design and public engagement with scientific tools. Because of these myriad benefits, the U.S. government has made significant strides in using open source software for digital solutions. For example, 18F, an office within the General Services Administration (GSA) that acts as a digital services consultancy for agency partners, defaults to open source for software created in-house with agency staff as well as in contracts it negotiates.

Open science hardware, as defined by the Gathering for Open Science Hardware, is any physical tool used for scientific investigations that can be obtained, assembled, used, studied, modified, shared, and sold by anyone. It includes standard lab equipment as well as auxiliary materials, such as sensors, biological reagents, and analog and digital electronic components. Beyond a set of scientific tools, open science hardware is an alternative approach to the scientific community’s reliance on expensive and proprietary equipment, tools, and supplies. Open science hardware is growing quickly in academia, with new networks, journals, publications, and events crossing institutions and disciplines. There is a strong case for open science hardware in the service of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, as a collaborative solution to challenges in environmental monitoring, and to increase the impact of research through technology transfer. Although limited so far, some federal agencies support open science hardware, such as an open source Build-It-Yourself Rover; the development of infrastructure, including NIH 3D, a platform for sharing 3D printing files and documentation; and programs such as the National Science Foundation’s Pathways to Enable Open-Source Ecosystems.

If federal agencies regularly used and contributed to open science hardware for agency science, it would have a transformative effect on the scientific ecosystem.

Federal agency procurement practices are complex, time-intensive, and difficult to navigate. Like other small businesses and organizations, the developers and users of open science hardware often lack the capacity and specialized staff needed to compete for federal procurement opportunities. Recent innovations demonstrate how the federal government can change how it buys and uses equipment and supplies. Agency Innovation Labs at the Department of Defense, Department of Homeland Security, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration, National Institute of Standards and Technology, and the Census Bureau have developed innovative procurement strategies to allow for more flexible and responsive government purchasing and provide in-house expertise to procurement officers on using these models in agency contexts. These teams provide much-needed infrastructure for continuing to expand the understanding and use of creative, mission-oriented procurement approaches, which can also support open science hardware for agency missions.

Agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), NOAA, and the Department of Agriculture (USDA) are well positioned to both benefit greatly from and make essential contributions to the open source ecosystem. These agencies have already demonstrated interest in open source tools; for example, the NOAA Technology Partnerships Office has supported the commercialization of open science hardware that is included in the NOAA Technology Marketplace, including an open source ocean temperature and depth logger and a sea temperature sensor designed by NOAA researchers and partners. These agencies have significant need for scientific instrumentation for agency work, and they often develop and use custom solutions for agency science. Each of these agencies has a demonstrated commitment to broadening public participation in science, which open science hardware supports. For example, EPA’s Air Sensor Loan Programs bring air sensor technology to the public for monitoring and education. Moreover, these agencies’ missions invite public engagement in a way that a commitment to open source instrumentation and tools would build a shared infrastructure for progress in the public good.

Recommendations

We recommend that the GSA take the following steps to build capacity for the use of open science hardware across government:

- Create an Interagency Community of Practice for federal staff working on open source–related topics.

- Direct the Technology Transformation Services to create boilerplate language for procurement of open source hardware that is compliant with the Federal Acquisition Authority and the America COMPETES Reauthorization Act of 2010.

- Conduct training on open source and open science hardware for procurement professionals across government.

We also recommend that EPA, NOAA, and USDA take the following steps to build capacity for agency use of open science hardware:

- Task agency representatives to identify agency scientific instrumentation needs that are most amenable to open source solutions. For example, the EPA Office of Research and Development could use and contribute to open source air quality sensors for research on spatial and temporal variation in air quality, and the USDA could use and contribute to an open source soil testing kit.

- Task agency challenge and prize coordinators with working intra-agency on a challenge or prize competition to create an open source option for one of the identified scientific instruments or sensors above that meets agency quality requirements.

- Support agency staff in using open source approaches when creating and using scientific instrumentation. Include open source scientific instrumentation in internal communication products, highlight staff efforts to create and use open science hardware, and provide training to agency staff on its development and use.

- Integrate open source hardware into Procurement Innovation Labs or agency procurement offices. This may include training for acquisition professionals on the use of open science hardware so that they can understand the benefits and better support agency staff use. This can include options for using open source designs and how to understand and use open source licenses.

Conclusion

Defaulting to open science hardware for agency science will result in an open library of tools for science that are replicable and customizable and result in a much higher return on investment. Beyond that, prioritizing open science hardware in agency science would allow all kinds of institutions, organizations, communities, and individuals to contribute to agency science goals in a way that builds upon each of their efforts.

Open scientific grant proposals to advance innovation, collaboration, and evidence-based policy

Grant writing is a significant part of a scientist’s work. While time-consuming, this process generates a wealth of innovative ideas and in-depth knowledge. However, much of this valuable intellectual output — particularly from the roughly 70% of unfunded proposals — remains unseen and underutilized. The default secrecy of scientific proposals is based on many valid concerns, yet it represents a significant loss of potential progress and a deviation from government priorities around openness and transparency in science policy. Facilitating public accessibility of grant proposals could transform them into a rich resource for collaboration, learning, and scientific discovery, thereby significantly enhancing the overall impact and efficiency of scientific research efforts.

We recommend that funding agencies implement a process by which researchers can opt to make their grant proposals publicly available. This would enhance transparency in research, encourage collaboration, and optimize the public-good impacts of the federal funding process.

Details

Scientists spend a great deal of time, energy, and effort writing applications for grant funding. Writing grants has been estimated to take roughly 15% of a researcher’s working hours and involves putting together an extensive assessment of the state of knowledge, identifying key gaps in understanding that the researcher is well-positioned to fill, and producing a detailed roadmap for how they plan to fill that knowledge gap over a span of (typically) two to five years. At major federal funding agencies like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation (NSF), the success rate for research grant applications tends to fall in the range of 20%–30%.

The upfront labor required of scientists to pursue funding, and the low success rates of applications, has led some to estimate that ~10% of scientists’ working hours are “wasted.” Other scholars argue that the act of grant writing is itself a valuable and generative process that produces spillover benefits by incentivizing research effort and informing future scholarship. Under either viewpoint, one approach to reducing the “waste” and dramatically increasing the benefits of grant writing is to encourage proposals — both funded and unfunded — to be released as public goods, thus unlocking the knowledge, frontier ideas, and roadmaps for future research that are currently hidden from view.

The idea of grant proposals being made public is a sensitive one. Indeed, there are valid reasons for keeping proposals confidential, particularly when they contain intellectual property or proprietary information, or when they are in the early stages of development. However, these reasons do not apply to all proposals, and many potential concerns only apply for a short time frame. Therefore, neither full disclosure nor full secrecy are optimal; a more flexible approach that encourages researchers to choose when and how to share their proposals could yield significant benefits with minimal risks.

The potential benefits to the scientific community, and science funders include:

- Encouraging collaboration by making promising unfunded ideas and shared interests discoverable by disparate researchers

- Supporting early-career scientists by giving them access to a rich collection of successful and unsuccessful proposals from which to learn

- Facilitating cutting-edge science-of-science research to unlock policy-relevant knowledge about research programs and scientific grantmaking

- Allowing for philanthropic crowd-in by creating a transparent and searchable marketplace of grant proposals that can attract additional or alternative funding

- Promoting efficiency in the research planning and budgeting process by increasing transparency

- Giving scientists, science funders, and the public a view into the whole of early-stage scientific thought, above and beyond the outputs of completed projects.

Recommendations

Federal funding agencies should develop a process to allow and encourage researchers to share their grant proposals publicly, within existing infrastructures for grant reporting (e.g., NIH RePORTER). Sharing should be minimally burdensome and incorporated into existing application frameworks. The process should be flexible, allowing researchers to opt in or out — and to specify other characteristics like embargoes — to ensure applicants’ privacy and intellectual property concerns are mitigated.

The White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) should develop a framework for publicly sharing grant proposals.

- OMB’s Evidence Team — in partnership with federal funding agencies (e.g., NIH, NSF, NASA, DOE) — should review statutory and regulatory frameworks to determine whether there are legal obstacles to sharing proposal content for extramural grant applications with applicant permission.

- OMB should then issue a memo clarifying the manner in which agencies can make proposals public and directing agencies to develop plans to allow and encourage the public availability of scientific grant proposals, in alignment with the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act and the “Memorandum on Restoring Trust in Government Through Scientific Integrity and Evidence-Based Policymaking.”

The NSF should run a focused pilot program to assess opportunities and obstacles for proposal sharing across disciplines.

- NSF’s Division of Institution and Award Support (DIAS) should work with at least three directorates to launch a pilot study assessing applicants’ perspectives on proposal sharing, their perceived risks and concerns, and disciplinary differences in applicants’ views.

- The National Science Board (NSB) should produce a report outlining the findings of the pilot study and the implications for optimal approaches to facilitating public access of grant proposals.

Based on the NSB’s report, OSTP and OMB should work with federal funding agencies to refine and implement a proposal-sharing process across agencies.

- OSTP should work with funding agencies to develop a unified application section where researchers can indicate their release preferences. The group should agree on a set of shared parameters to align the request across agencies. For example, the guidelines should establish:

- A set of embargo options, such that applicants can choose to make their proposal available after, for example, 2, 5, or 10 years

- Whether the sharing of proposals can be made conditional on acceptance/rejection

- When in the application process applicants should be asked to opt in or out, and an approach for allowing applicants to revise their decision following submission

- OMB should include public access for grant proposals as a budget priority, emphasizing its potential benefits for bolstering innovation, efficiency, and government data availability. It should also provide guidance and technical assistance to agencies on how to implement the open grants process and require agencies to provide evidence of their plans to do so.

Establish data collaboratives to foster meaningful public involvement

Federal agencies are striving to expand the role of the public, including members of marginalized communities, in developing regulatory policy. At the same time, agencies are considering how to mobilize data of increasing size and complexity to ensure that policies are equitable and evidence-based. However, community engagement has rarely been extended to the process of examining and interpreting data. This is a missed opportunity: community members can offer critical context to quantitative data, ground-truth data analyses, and suggest ways of looking at data that could inform policy responses to pressing problems in their lives. Realizing this opportunity requires a structure for public participation in which community members can expect both support from agency staff in accessing and understanding data and genuine openness to new perspectives on quantitative analysis.

To deepen community involvement in developing evidence-based policy, federal agencies should form Data Collaboratives in which staff and members of the public engage in mutual learning about available datasets and their affordances for clarifying policy problems.

Details

Executive Order 14094 and the Office of Management and Budget’s subsequent guidance memo direct federal agencies to broaden public participation and community engagement in the federal regulatory process. Among the aims of this policy are to establish two-way communications and promote trust between government agencies and the public, particularly members of historically underserved communities. Under the Executive Order, the federal government also seeks to involve communities earlier in the policy process. This new attention to community engagement can seem disconnected from the federal government’s long-standing commitment to evidence-based policy and efforts to ensure that data available to agencies support equity in policy-making; assessing data and evidence is usually considered a job for people with highly specialized, quantitative skills. However, lack of transparency about the collection and uses of data can undermine public trust in government decision-making. Further, communities may have vital knowledge that credentialed experts don’t, knowledge that could help put data in context and make analyses more relevant to problems on the ground.

For the federal government to achieve its goals of broadened participation and equitable data, opportunities must be created for members of the public and underserved communities to help shape how data are used to inform public policy. Data Collaboratives would provide such an opportunity. Data Collaboratives would consist of agency staff and individuals affected by the agency’s policies. Each member of a Data Collaborative would be regarded as someone with valuable knowledge and insight; staff members’ role would not be to explain or educate but to learn alongside community participants. To foster mutual learning, Data Collaboratives would meet regularly and frequently (e.g., every other week) for a year or more.

Each Data Collaborative would focus on a policy problem that an agency wishes to address. The Environmental Protection Agency might, for example, form a Data Collaborative on pollution prevention in the oil and gas sector. Depending on the policy problem, staff from multiple agencies may be involved alongside community participants. The Data Collaborative’s goal would be to surface the datasets potentially relevant to the policy problem, understand how they could inform the problem, and identify their limitations. Data Collaboratives would not make formal recommendations or seek consensus; however, ongoing deliberations about the datasets and their affordances can be expected to create a more robust foundation for the use of data in policy development and the development of additional data resources.

Recommendations

The Office of Management and Budget should

- Establish a government-wide Data Collaboratives program in consultation with the Chief Data Officers Council.

- Work with leadership at federal agencies to identify policy problems that would benefit from consideration by a Data Collaborative. It is expected that deputy administrators, heads of equity and diversity offices, and chief data officers would be among those consulted.

- Hire a full-time director of Data Collaboratives to lead such tasks as coordinating with public participants, facilitating meetings, and ensuring that relevant data resources are available to all collaborative members.

- Ensure agencies’ ability to provide the material support necessary to secure the participation of underrepresented community members in Data Collaboratives, such as stipends, childcare, and transportation.

- Support agencies in highlighting the activities and accomplishments of Data Collaboratives through social media, press releases, open houses, and other means.

Conclusion

Data Collaboratives would move public participation and community engagement upstream in the policy process by creating opportunities for community members to contribute their lived experience to the assessment of data and the framing of policy problems. This would in turn foster two-way communication and trusting relationships between government and the public. Data Collaboratives would also help ensure that data and their uses in federal government are equitable, by inviting a broader range of perspectives on how data analysis can promote equity and where relevant data are missing. Finally, Data Collaboratives would be one vehicle for enabling individuals to participate in science, technology, engineering, math, and medicine activities throughout their lives, increasing the quality of American science and the competitiveness of American industry.

Make publishing more efficient and equitable by supporting a “publish, then review” model

Preprinting – a process in which researchers upload manuscripts to online servers prior to the completion of a formal peer review process – has proven to be a valuable tool for disseminating preliminary scientific findings. This model has the potential to speed up the process of discovery, enhance rigor through broad discussion, support equitable access to publishing, and promote transparency of the peer review process. Yet the model’s use and expansion is limited by a lack of explicit recognition within funding agency assessment practices.

The federal government should take action to support preprinting, preprint review, and “no-pay” publishing models in order to make scholarly publishing of federal outputs more rapid, rigorous, and cost-efficient.

Details

In 2022, the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP)’s “Ensuring Free, Immediate, and Equitable Access to Federally Funded Research” memo, written by Dr. Alondra Nelson, directed federal funding agencies to make the results of taxpayer-supported research immediately accessible to readers at no cost. This important development extended John P. Holdren’s 2013 “Increasing Access to the Results of Federally Funded Scientific Research” memo by covering all federal agencies and removing 12-month embargoes to free access and mirrored developments such as the open access provisions of Horizon 2020 in Europe.

One of the key provisions of the Nelson memo is that federal agencies should “allow researchers to include reasonable publication costs … as allowable expenses in all research budgets,” signaling support for the Article Processing Charges (APC) model. Thus, the Nelson memo creates barriers to equitable publishing for researchers with limited access to funds. Furthermore, leaving the definition of “reasonable costs” open to interpretation creates the risk that an increasing proportion of federal research funds will be siphoned by publishing. In 2022, OSTP estimated that American taxpayers are already paying $390 to $798 million annually to publish federally funded research.

Without further interventions, these costs are likely to rise, since publishers have historically responded to increasing demand for open access publishing by shifting from a subscription model to one in which authors pay to publish with article processing charges (APCs). For example, APC charges increased by 50 percent from 2010 to 2019.

The “no pay” model

In May 2023, the European Union’s council of ministers called for a “no pay” academic publishing model, in which costs are paid directly by institutions and funders to ensure equitable access to read and publish scholarship. There are several routes to achieve the no pay model, including transitioning journals to ‘Diamond’ Open Access models, in which neither authors nor readers are charged.

However, in contrast to models that rely on transforming journal publishing, an alternative approach relies on the burgeoning preprint system. Preprints are manuscripts posted online by authors to a repository, without charge to authors or readers. Over the past decade, their use across the scientific enterprise has grown dramatically, offering unique flexibility and speed to scientists and encouraging dynamic conversation. More recently, preprints have been paired with a new system of preprint peer review. In this model, organizations like Peer Community In, Review Commons, and RR\ID organize expert review of preprints from the community. These reviews are posted publicly and independent of a specific publisher or journal’s process.

Despite the growing popularity of this approach, its uptake is limited by a lack of support and incorporation into science funding and evaluation models. Federal action to encourage the “publish, then review” model offers several benefits:

- Research is available sooner, and society benefits more rapidly from new scientific findings. With preprints, researchers share their work with the community months or years ahead of journal publication, allowing others to build off their advances.

- Peer review is more efficient and rigorous because the content of the review reports (though not necessarily the identity of the reviewers) is open. Readers are able to understand the level of scrutiny that went into the review process. Furthermore, an open review process enables anyone in the community to join the conversation and bring in perspectives and expertise that are currently excluded. The review process is less wasteful since reviews are not discarded with journal rejection, making better use of researchers’ time.

- Taxpayer research dollars are used more effectively. Disentangling transparent fees for dissemination and peer reviews from a publishing market driven largely by prestige would result in lower publishing costs, enabling additional funds to be used for research.

Recommendations

To support preprint-based publishing and equitable access to research:

Congress should

- Commission a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine on benefits, risks, and projected costs to American taxpayers of supporting alternative scholarly publishing approaches, including open infrastructure for the “publish, then review” model.

OSTP should

- Coordinate support for key disciplinary infrastructures and peer review service providers with partnerships, discoverability initiatives, and funding.

- Draft a policy in which agencies require that papers resulting from federal funding are preprinted at or before submission to peer review and updated with each subsequent version; then work with agencies to conduct a feasibility study and stakeholder engagement to understand opportunities (including cost savings) and obstacles to implementation.

Science funding agencies should

- Recognize preprints and public peer review. Following the lead of the National Institutes of Health’s 2017 Guide Notice on Reporting Preprints and Other Interim Research Products, revise grant application and report guidelines to allow researchers to cite preprints. Extend this provision to include publicly accessible reviews they have received and authored. Provide guidance to reviewers on evaluating these outputs as scientific contributions within an applicant’s body of work.

Establish grant supplements for open science infrastructure security

Open science infrastructure (OSI), such as platforms for sharing research products or conducting analyses, is vulnerable to security threats and misappropriation. Because these systems are designed to be inclusive and accessible, they often require few credentials of their users. However, this quality also puts OSI at risk for attack and misuse. Seeking to provide quality tools to their users, OSI builders dedicate their often scant funding resources to addressing these security issues, sometimes delaying other important software work.

To support these teams and allow for timely resolution to security problems, science funders should offer security-focused grant supplements to funded OSI projects.

Details

Existing federal policy and funding programs recognize the importance of security to scholarly infrastructure like OSI. For example, in October 2023, President Biden issued an Executive Order to manage the risks of artificial intelligence (AI) and ensure these technologies are safe, secure, and trustworthy. Also, under the Secure and Trustworthy Cyberspace program, the National Science Foundation (NSF) provides grants to ensure the security of cyberinfrastructure and asks scholars who collect data to plan for its secure storage and sharing. Furthermore, agencies like NSF and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) already offer supplements for existing grants. What is still needed is rapid dispersal of funds to address unanticipated security concerns across scientific domains.

Risks like secure shell (SSH) attacks, data poisoning, and the proliferation of mis/disinformation on OSI threaten the utility, sustainability, and reputation of OSI. These concerns are urgent. New access to powerful generative AI tools, for instance, makes it easy to create disinformation that can convincingly mimic the rigorous science shared via OSI. In fact, increased open access to science can accelerate the proliferation of AI-generated scholarly disinformation by improving the accuracy of the models that generate it.

OSI is commonly funded by grants that afford little support for the maintenance work that could stop misappropriation and security threats. Without financial resources and an explicit commitment to a funder, it is difficult for software teams to prioritize these efforts. To ensure uptake of OSI and its continued utility, these teams must have greater access to financial resources and relevant talent to address these security concerns and norms violations.

Recommendations

Security concerns may be unanticipated and urgent, not aligning with calls for research proposals. To provide support for OSI with security risks in a timely manner, executive action should be taken through federal agencies funding science infrastructure (NSF, NIH, NASA, DOE, DOD, NOAA). These agencies should offer research supplements to address OSI misappropriation and security threats. Supplement requests would be subject to internal review by funding agencies but not subject to peer review, allowing teams to circumvent a lengthier review process for a full grant proposal. Research supplements, unlike full grant proposals, will allow researchers to nimbly respond to novel security concerns that arise after they receive their initial funding. Additionally, researchers who are less familiar with security issues but who provide OSI may not anticipate all relevant threats when the project is conceived and initial funding is distributed (managers of from-scratch science gateways are one possible example). Supplying funds through supplements when the need arises can protect sensitive data and infrastructure.

These research supplements can be made available to principal investigators and co-principal investigators with active awards. Supplements may be used to support additional or existing personnel, allowing OSI builders to bring new expertise to their teams as necessary. To ensure that funds can address unanticipated security issues in OSI from a variety of scholarly domains, supplement recipients need not be funded under an existing program to explicitly support open science infrastructure (e.g., NSF’s POSE program).

To minimize the administrative burden of review, applications for supplements should be kept short (e.g., no more than five pages, excluding budget) and should include the following:

- A description of the security issue to be addressed

- A convincing argument that the infrastructure has goals of increasing the inclusion, accessibility, and/or transparency of science and that those goals are exacerbating the relevant security threat

- A description of the steps to be taken to address the security issue and a well-supported argument that the funded researchers have the expertise and tools necessary to carry those steps out

- A brief description of the original grant’s scope, making evident that the supplemental funding will support work outside of the original scope

- An explanation as to why a grant supplement is more appropriate for their circumstances than a new full grant application

- A budget for the work

By appropriating $3 million annually across federal science funders, 40 supplemental awards of $75,000 each could be distributed to OSI projects. While the budget needed to address each security issue will vary, this estimate demonstrates the reach that these supplements could have.

Research software like OSI often struggles to find funding for maintenance. These much-needed supplemental funds will ensure that OSI developers can speedily prioritize important security-related work without doing so at the expense of other planned software work. Without this funding, we risk compromising the reputation of open science, consuming precious development resources allocated to other tasks, and negatively affecting OSI users’ experience. Grant supplements to address OSI security threats and misappropriation ensure the sustainability of OSI going forward.

Expand capacity and coordination to better integrate community data into environmental governance

Frontline communities bear the brunt of harms created by climate change and environmental pollution, but they also increasingly generate their own data, providing critical social and environmental context often not present in research or agency-collected data. However, community data collectors face many obstacles to integrating this data into federal systems: they must navigate complex local and federal policies within dense legal landscapes, and even when there is interest or demonstrated need, agencies and researchers may lack the capacity to find or integrate this data responsibly.

Federal research and regulatory agencies, as well as the White House, are increasingly supporting community-led environmental justice initiatives, presenting an opportunity to better integrate local and contextualized information into more effective and responsive environmental policy.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) should better integrate community data into environmental research and governance by building internal capacity for recognizing and applying such data, facilitating connections between data communities, and addressing misalignments with data standards.

Details

Community science and monitoring are often overlooked yet vital facets of open science. Community science collaborations and their resulting data have led to historic environmental justice victories that underscore the importance of contextualized community-generated data in environmental problem-solving and evidence-informed policy-making.

Momentum around integrating community-generated environmental data has been building at the federal level for the past decade. In 2016, the report “A Vision for Citizen Science at EPA,” produced by the National Advisory Council for Environmental Policy and Technology (NACEPT), thoroughly diagnosed the need for a clear framework for moving community-generated environmental data and information into governance processes. Since then, EPA has developed additional participatory science resources, including a participatory science vision, policy guidelines, and equipment loan programs. More recently, in 2022, the EPA created an Equity Action Plan in alignment with their 2022–2026 Strategic Plan and established an Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights (OEJECR). And, in 2023, as a part of the cross-agency Year of Open Science, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)’s Transform to Open Science (TOPS) program lists “broadening participation by historically excluded communities” as a requisite part of its strategic objectives.

It is evident that the EPA and research funding agencies like NASA have a strategic and mission-driven interest in collaborating with communities bearing the brunt of environmental and climate injustice to unlock the potential of their data. It is also clear that current methods aren’t working. Communities that collect and use environmental data still must navigate disjointed reporting policies and data standards and face a dearth of resources on how to share data with relevant stakeholders within the federal government. There is a critical lack of capacity and coordination directed at cross-agency integration of community data and the infrastructure that could enable the use of this data in regulatory and policy-making processes.

Recommendations

To build government capacity to integrate community-generated data into environmental governance, the EPA should:

- Create a memorandum of understanding between the EPA’s OEJECR, National Environmental Justice Advisory Council (NEJAC), Office of Management and Budget (OMB), United States Digital Service (USDS), and relevant research agencies, including NASA, National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration (NOAA), and National Science Foundation (NSF), to develop a collaborative framework for building internal capacity for generating and applying community-generated data, as well as managing it to enable its broader responsible reuse.

- Develop and distribute guidance on responsible scientific collaboration with communities that prioritizes ethical open science and data-sharing practices that center community and environmental justice priorities.

- Create a capacity-building program, designed by and with environmental justice and data-collecting communities, focused on building translational and intermediary roles within the EPA that can facilitate connections and responsible sharing between data holders and seekers. Incentivize the application of the aforementioned guidance within federally funded research by recruiting and training program staff to act as translational liaisons situated between the OEJECR, regional EPA offices, and relevant research funding agencies, including NASA, NOAA, and NSF.

To facilitate connections between communities generating data, the EPA should:

- Expand the scope of the current Environmental Information Exchange Network (EN) to include facilitation of environmental data sharing by community-based organizations and community science initiatives.

- Initiate a working group including representatives from data-generating community organizations to develop recommendations on how EN might accommodate community data and how its data governance processes can center community and environmental justice priorities.

- Provide grant funding within the EN earmarked for community-based organizations to support data integration with the EN platform. This could include hiring contractors with technical data management expertise to support data uploading within established standards or to build capacity internally within community-based organizations to collect and manage data according to EN standards.

- Expand the resources available for EN partners that support data quality assurance, advocacy, and sharing, for example by providing technical assistance through regional EPA offices trained through the aforementioned capacity-building program.

To address misaligned data standards, the EPA, in partnership with USDS and the OMB, should:

- Update and promote guidance resources for communities and community-based organizations aiming to apply the data standards EPA uses to integrate data in regulatory decisions.

- Initiate a collaborative co-design process for new data standards that can accommodate community-generated data, with representation from communities who collect environmental data. This may require the creation of maps or crosswalks to facilitate translation between standards, including research data standards, as well as internal capacity to maintain these crosswalks.

Community-generated data provides contextualized environmental information essential for evidence-based policy-making and regulation, which in turn reduces wasteful spending by designing effective programs. Moreover, healthcare costs will be reduced for the general public if better evidence is used to address pollution, and climate adaptation costs could be reduced if we can use more localized and granular data to address pressing environmental and climate issues now rather than in the future.

Our recommendations call for the addition of at least 10 full-time employees for each regional EPA office. The additional positions proposed could fill existing vacancies in newly established offices like the OEJECR. Additional budgetary allocations can also be made to the EPA’s EN to support technical infrastructure alterations and grant-making.

While there is substantial momentum and attention on community environmental data, our proposed capacity stimulus can make existing EPA processes more effective at achieving their mission and supports rebuilding trust in agencies that are meant to serve the public.

A Matter of Trust: Helping the Bioeconomy Reach Its Full Potential with Translational Governance

The promise of the bioeconomy is massive and fast-growing—offering new jobs, enhanced supply chains, novel technologies, and sustainable bioproducts valued at a projected $4 trillion over the next 16 years. Although the United States has been a global leader, advancements in the bioeconomy—whether it’s investing in specialized infrastructural hardware or building a multidisciplinary STEM workforce—are subject to public trust. In fact, public trust is the key to unlocking the full potential of the bioeconomy, and without it, the United States may fall short of long-term economic goals and even fall behind peer nations as a bioeconomy leader. Recent failures of the federal regulatory system for biotechnology threaten public trust, and recent regulations have been criticized for their lack of transparency. As a result, cross-sector efforts aim not just to reimagine the bioeconomy but to create a coordinated regulatory system for it. Burdened by decreasing public trust in the federal government, even the most coordinated regulatory systems will fail to boost the bioeconomy if they cannot instill public trust.

In response, the Biden-Harris Administration should direct a Bioeconomy Initiative Coordination Office (BICO) to establish a public engagement mechanism parallel with the biotechnology regulatory system. Citizen engagement and transparency are key to building public trust, yet current public engagement mechanisms cannot convey trust to a public skeptical of a biotechnology’s rewards in light of perceived risks. Bioeconomy coordination efforts should therefore prioritize public trust by adopting a new public-facing biotechnology evaluation program that collects data from nontraditional audiences via participatory technology assessments (pTA) and Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA/MCDM) and provides insight that addresses limitations. In accordance with the CHIPS and Science Act, the public engagement program will provide a mechanism for a BICO to build public trust while advancing the bioeconomy.

The public engagement program will serve as a decision-making resource for the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology (CFRB) and a data repository for evaluating public acceptance in the present and future bioeconomy.

Challenge and Opportunity

While policymakers have been addressing the challenge of sharing regulatory space among the three key agencies—Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and USDA—transparency and public trust remain challenges for federal agencies, small to midsize developers, and even the public at large. The government plays a vital role in the regulatory process by providing guidelines that govern the interactions between the developers and consumers of biotechnology. For over 30 years, product developers have depended on strategic alliances between product developers and the government to ensure the market success of biotechnology. The marketplace and regulatory oversight are tightly linked, and their impacts on public confidence in the bioeconomy cannot be separated.

When it comes to a consumer’s purchase of a biotechnology product, the pivotal factor is often not price but trust. In 2016, the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released recommendations on aligning public values with gene drive research. The report revealed that public engagement that promotes a “bi-directional exchange of information and perspectives” can increase public trust. Moreover, a 2022 report on Gene Drives in Agriculture highlights the importance of considering public perception and acceptance in risk-based decision-making.

The CHIPS and Science Act provides an opportunity to address transparency and public trust within the federal regulatory system for biotechnology by directing the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to establish a Coordination Office for the National Engineering Biology Research and Development Initiative. The coordination office (i.e., BICO) will serve as a point of contact for cross-sector engagement and create a junction for the exchange of technical and programmatic information. Additionally, the office will conduct public outreach and produce recommendations for strengthening the bioeconomy.

This policy window presents a novel opportunity to create a regulatory system for the bioeconomy that also encompasses the voice of the general public. History of requests for information, public hearings, and cross-sector partnerships demonstrates the public’s capacity—or at least specific subsets of experts therein—to fill gaps, oversights, and ambiguities within biotechnology regulations.

While expert opinion is essential for developing regulation, so too are the opinions of the general public. Historically, discussions about values, sentiments, and opinions on biotechnology have been dominated by technical experts (for example, through debates on product vs. process, genetically engineered vs. genetically modified organisms, and perceived safety). Biotechnology discourse has primarily been restricted to these traditional, technical audiences, and as a result, public calls to address concerns about biotechnology are drowned out by expert opinions. We need a mechanism for public engagement that prioritizes collecting data from nontraditional audiences. This will ensure sustainable and responsible advancements in the bioeconomy.

If we want to establish a bioeconomy that increases national competitiveness, then we need to increase the participation of nontraditional audiences. Although some public concerns are unlikely to be allayed through policy change (e.g., addressing calls for a ban on genetically engineered or modified products), a public engagement program could identify the underlying issue(s) for these concerns. This would enable the adoption of comprehensive strategies that increase public trust, further sustaining the bioeconomy.

Research shows that public comment and notice periods are less likely to hear from nontraditional audiences—that is, members of underserved communities, workers, smaller market entities, and new firms. Despite the statutory and capacity-based obstacles federal agencies face in increasing public participation, the Executive Office of the President seeks to broaden public participation and community engagement in the federal regulatory process. Public engagement programs provide a platform to interact with interested parties that represent a wide range of perspectives. Thus, information gathered from public engagement could inform future proposed updates to the CFRB and the regulatory pathways for new products. In this way, the public opinions and sentiments can be incorporated into a translational governance framework to bring translational value to the bioeconomy. Since increasing public trust is complementary to advancing the bioeconomy, there is a translational value in strategically integrating a collective perception of risk and safety into future biotechnology regulation. In this case, translational governance allows for regulation that is informed by science and is responsive to the values of citizens, effectively introducing a policy lever that improves the adoption of, and investment in, the U.S. bioeconomy.

The future of biotechnology regulation is an emerging innovative ecosystem. The path to accomplishing economic goals within this ecosystem requires a new public-facing engagement mechanism framework that satisfies congressional directives and advances the bioeconomy. This framework provides a BICO with the scaffolding necessary to create an infrastructure that invites public input and community reflection and the potential to decrease the number of biotechnologies that fail to reach the market. The proposed public engagement mechanism will work alongside the current regulatory system for biotechnology to enhance public trust, improve interagency coordination, and strengthen the bioeconomy.

Plan of Action

To reach our national bioeconomic policy goals, the BICO should use a public engagement program to solicit perspectives and develop an understanding of non-economic values, such as deeply held beliefs about the relationship between humans and the environment or personal or cultural perspectives related to specific biotechnologies. The BICO should devote $10 million over five years to public engagement programs and advisory board activities that (a) report to the BICO but are carried out through external partnerships; (b) provide meaningful social data for biotechnology regulation while running parallel to the CFRB regulatory system; and (c) produce a repository of public acceptance data for horizon scanning. These programs will inform regulatory decision-making, increase public trust, and achieve the congressional directives outlined in Sec. 10402 of the CHIPS & Science Act.

Recommendation 1. Establish a Bioeconomy Initiative Coordination Office (BICO) as a home office for interagency coordination.

The BICO should be housed within the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). The creation of a BICO is in alignment with the mandates of Executive Order (EO) 14081, Advancing Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing Innovation for a Sustainable, Safe, and Secure Bioeconomy, and the statutory authority granted to the OSTP through the CHIPS and Science Act.

Congress should allocate $2 million annually for five years to the BICO to carry out a public engagement program and advisory board activities in coordination with the EPA, FDA, and USDA.

The public engagement program would be housed within the BICO as a public-facing data-generating mechanism that parallels the current federal regulatory system for biotechnology.

The bioeconomy cuts across sectors (e.g., agriculture, health, materials, energy) and actively creates new connections and opportunities for national competitiveness. A thriving bioeconomy must ensure regulatory policy coherence and alignment among these sectors, and the BICO should be able to comprehensively integrate information from multiple sectors into a strategy that increases public awareness and acceptance of bioeconomy-related products and services. Public engagement should be used to build a data ecosystem of values related to biotechnologies that advance the bioeconomy.

Recommendation 2. Establish a process for public engagement and produce a large repository of public acceptance data.

Public acceptance data will be collected alongside the “biological data ecosystem,” as referenced by the Biden Administration in EO 14081, that advances innovation in the bioeconomy. To provide an expert element to the public engagement process, an advisory board should be involved in translating public acceptance data (opinions on how biotechnologies align with values) into policy suggestions and recommendations for regulatory agencies. The advisory board should be a formal entity recognizable under the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) and the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). It should be diverse but not so large that it becomes inefficient in fulfilling its mandate. Striking a balance between compositional diversity and operational efficiency is critical to ensuring the board provides valuable insights and recommendations to the BICO. The advisory board should consist of up to 25 members, reflect NSF data on diversity and STEM, and include a diverse range of citizens, from everyday consumers (such as parents, young adults, and patients from different ethnic backgrounds) to specialists in various disciplines (such as biologists, philosophers, hair stylists, sanitation workers, social workers, and dietitians). To promote transparency and increase public trust, data will be subject to FACA and the FOIA regulations, and advisory board meetings must be accessible to the public and their details must be published in the Federal Register. Additionally, management and applications of any data collected should employ CARE (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, Ethics) Principles for Indigenous Data Governance, which complement FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable) Principles. Adopting CARE brings a people and purpose orientation to data governance and is rooted in Indigenous Peoples’ sovereignty.

The BICO can look to the National Science and Technology Council’s published requests for information (RFI) and public meetings as a model for public engagement. BICO should work with an inclusive network of external partners to design workshops for collecting public acceptance data. Using participatory technology assessments (pTA) methods, the BICO will fund public engagement activities such as open-framing focus groups, workshops, and forums that prioritize input from nontraditional public audiences. The BICO office should use pre-submission data, past technologies, near-term biotechnologies, and, where helpful, imaginative scenarios to produce case studies to engage with these audiences. Public engagement should be hosted by external grantees who maintain a wide-ranging network of interdisciplinary specialists and interested citizens to facilitate activities.

Qualitative and quantitative data will be used to reveal themes, public values, and rationales, which will aid product developers and others in the bioeconomy as they decide on new directions and potential products. This process will also serve as the primary data source for the public acceptance data repository. Evolving risk pathways are a considerable concern for any regulatory system, especially one tasked with regulating biotechnologies. How risks are managed is subject to many factors (history, knowledge, experience product) and has a lasting impact on public trust. Advancing the bioeconomy requires a transparent decision-making process that integrates public input and allows society to redefine risks and safety as a collective. Public acceptance data should inform an understanding of values, risks, and safety and improve horizon-scanning capabilities.

Conclusion

As the use of biotechnology continues to expand, policymakers must remain adaptive in their regulatory approach to ensure that public trust is acquired and maintained. Recent federal action to boost the bioeconomy provides an opportunity for policymakers to expand public engagement and improve public acceptance of biotechnology. By centralizing coordination and integrating public input, policymakers can create a responsive regulatory convention that advances the bioeconomy while also building public trust. To achieve this, the public engagement program will combine elements of community-based participatory research, value-based assessments, pTA, and CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. This approach will create a translational mechanism that improves interagency coordination and builds public trust. As the government works to create a regulatory framework for the bioeconomy, the need for public participation will only increase. By leveraging the expertise and perspectives of a diverse range of interested parties, policymakers can ensure that the regulatory framework is aligned with public values and concerns while promoting innovation and progress in the U.S. bioeconomy.

Translational governance focuses on expediting the implementation of regulations to safeguard human health and the environment while simultaneously encouraging innovation. This approach involves integrating non-economic values into decision-making processes to enhance scientific and statutory criteria of risk and safety by considering public perceptions of risk and safety. Essentially, it is the policy and regulatory equivalent of translational research, which strives to bring healthcare discoveries to market swiftly and safely.

The Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) should use translational governance through public engagement as a backbone of the National Engineering Biology Research and Development Initiative. Following the designation of an interagency committee by the OSTP—and once established under the scope of direction outlined in Sec. 10403 of the CHIPS and Science Act—the Initiative Coordination Office should use a public engagement program to support the following National Engineering Biology Research and Development Initiative congressional directives (Sec. 10402):

- 1) Supporting social and behavioral sciences and economics research that advances the field of engineering biology and contributes to the development and public understanding of new products, processes, and technologies.

- 2) Improving the understanding of engineering biology of the scientific and lay public and supporting greater evidence-based public discourse about its benefits and risks.

- 3) Supporting research relating to the risks and benefits of engineering biology, including under subsection d: Ensuring, through the agencies and departments that participate in the Initiative, that public input and outreach are integrated into the Initiative by the convening of regular and ongoing public discussions through mechanisms such as workshops, consensus conferences, and educational events, as appropriate].

- 4) Expanding the number of researchers, educators, and students and a retooled workforce with engineering biology training, including from traditionally underrepresented and underserved populations.

- 5) Accelerating the translation and commercialization of engineering biology and biomanufacturing research and development by the private sector.

- 6) Improving the interagency planning and coordination of federal government activities related to engineering biology.

In 1986, the newly issued regulatory system for biotechnology products faced significant statutory challenges in establishing the jurisdiction of the three key regulatory agencies (EPA, FDA, and USDA). In those early days, agency coordination allowed for the successful regulation of products that had shared jurisdiction. For example, one agency would regulate the plant in the field (USDA), and another would regulate the feed or food produced by the plant (FDA/DHHS). However, as the biotechnology product landscape has advanced, so has the complexity of agency coordination. For example, at the time of their commercialization, plants that were modified to exhibit pesticidal traits, specific microbial products, and certain genetically modified organisms cut across product use-specific regulations that were organized according to agency (i.e., field plants, food, pesticides). In response, the three key agencies have traditionally implemented their own rules and regulations (e.g., EPA’s Generally Recognized as Safe, USDA’s Am I Regulated?, USDA SECURE Rule). While such policy action is under their statutory authorities, it has resulted in policy resistance, reinforcing the confusion and lack of transparency within the regulatory process.

Since its formal debut on June 26, 1986, the CFRB has undergone two major updates, in 1992 and 2017. Additionally, the CFRB has been subject to multiple memorandums of understanding as well as two executive orders across two consecutive administrations (Trump and Biden). With the arrival of The CHIPS and Science Act (2022) and Executive Order 14081, the CFRB will likely undertake one of its most extensive updates—modernization for the bioeconomy.

According to the EPA, when the CFRB was issued in 1986, the expectation was that the framework would respond to the experiences of the industry and the agencies and that modifications would be accomplished through administrative or legislative actions. Moreover, upon their release of the 2017 updates to the CFRB, the Obama Administration described the CFRB as a “flexible regulatory structure that provides appropriate oversight for all products of modern biotechnology.” With this understanding, the CFRB is designed to be iterative and responsive to change. However, as this memo and other reports demonstrate, not all products of modern biotechnology are subject to appropriate oversight. The opportunity loss between addressing regulatory concerns and acquiring the regulations necessary to capitalize on the evolving biotechnology landscape fully presents a costly delay. The CFRB is falling behind biotechnology in a manner that hampers the bioeconomy—and likely—the future economy.

Automating Scientific Discovery: A Research Agenda for Advancing Self-Driving Labs

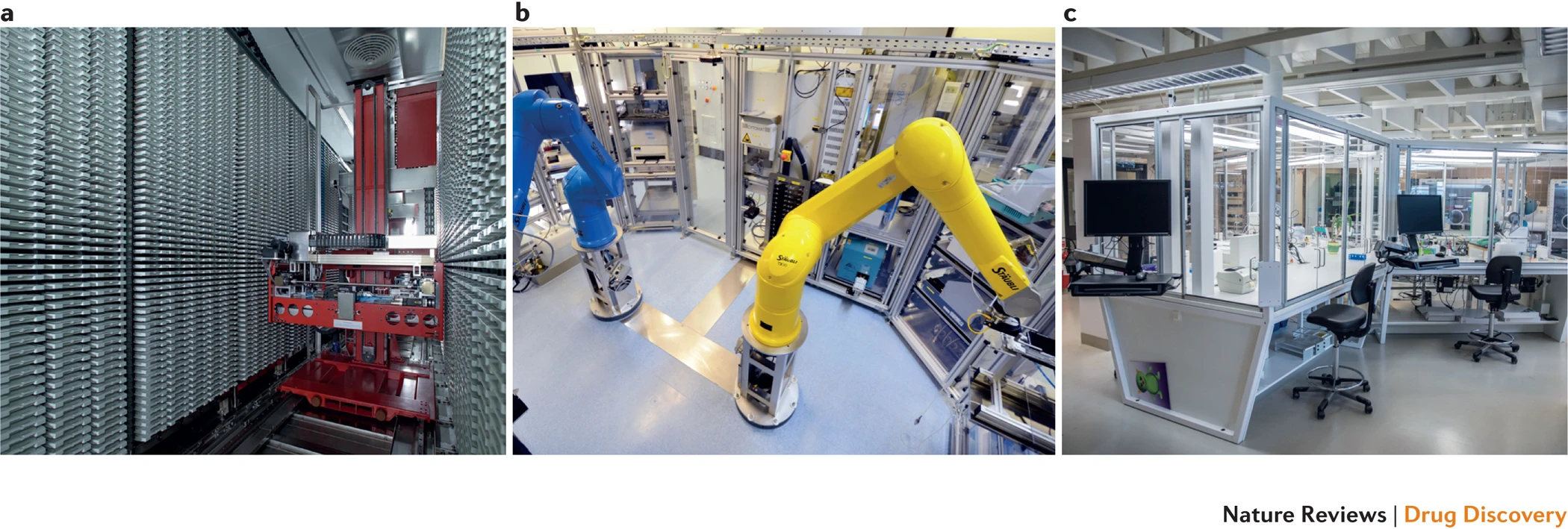

Despite significant advances in scientific tools and methods, the traditional, labor-intensive model of scientific research in materials discovery has seen little innovation. The reliance on highly skilled but underpaid graduate students as labor to run experiments hinders the labor productivity of our scientific ecosystem. An emerging technology platform known as Self-Driving Labs (SDLs), which use commoditized robotics and artificial intelligence for automated experimentation, presents a potential solution to these challenges.

SDLs are not just theoretical constructs but have already been implemented at small scales in a few labs. An ARPA-E-funded Grand Challenge could drive funding, innovation, and development of SDLs, accelerating their integration into the scientific process. A Focused Research Organization (FRO) can also help create more modular and open-source components for SDLs and can be funded by philanthropies or the Department of Energy’s (DOE) new foundation. With additional funding, DOE national labs can also establish user facilities for scientists across the country to gain more experience working with autonomous scientific discovery platforms. In an era of strategic competition, funding emerging technology platforms like SDLs is all the more important to help the United States maintain its lead in materials innovation.

Challenge and Opportunity