Creating a National HVDC Transmission Network

The United States should continue to pursue its commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50–52% from 2005 levels by 2030 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. To reach these goals, the United States must rapidly increase renewable-energy production while simultaneously building the transmission capacity needed to carry power generated from new renewable sources. Such an investment requires transforming the American electricity grid at a never-before-seen speed and scale. For example, the 2024 DOE National Transmission Planning study estimates that the American transmission system will need to grow between 2.4 – 3.5 times its 2020 size by 2050 to achieve a 90% greenhouse gas emissions reduction from a 2005 baseline by 2035 and net-zero emissions in 2050. A promising way to achieve this ambitious transmission target is to create a national High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) transmission network overlaid atop the existing alternating current (AC) grid. In addition to advancing America’s climate goals, such an effort would spur economic development in rural areas, improve the grid’s energy efficiency, and bolster grid stability and security. This memo proposes several policy options the Department of Energy (DOE) and Congress can pursue to incentivize private-sector efforts to construct a national HVDC transmission network while avoiding permitting issues that have doomed some previous HVDC projects.

Challenge and Opportunity

The current American electricity grid resembles the roadway system before the Eisenhower interstate system. Just as roads extended to most communities by the early 1950s, few areas are unelectrified today. However, the AC power lines that cross the United States today are tangled, congested, and ill-suited to quickly move large amounts of renewable power from energy-producing regions with lower demand (such as the Midwest and Southwest) directly to large population centers with high demand. Since HVDC transmission lines lose less power than AC lines at distances > 300 miles, HVDC technology is the best option to directly connect the renewable generation needed to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 with consumers.

There are few HVDC lines in the United States today. Those that do exist are scattered across the country and were not designed to facilitate renewable development. As a result, the United States is a long way from the integrated nationwide HVDC network needed to achieve net-zero emissions. Many recent attempts by the private sector to begin building long-distance HVDC transmission lines between renewable producing regions and consumers—such as Clean Line Energy’s proposal for an aboveground line that would have linked much of the Great Plains to the Southeast—have been unsuccessful due to a host of challenges. These challenges included negotiating leases with thousands of landowners with understandable concerns about how the project could alter their properties, negotiating with many local and state jurisdictions to secure project approval, and maintaining investor confidence throughout the complex and time-consuming permitting and leasing process.

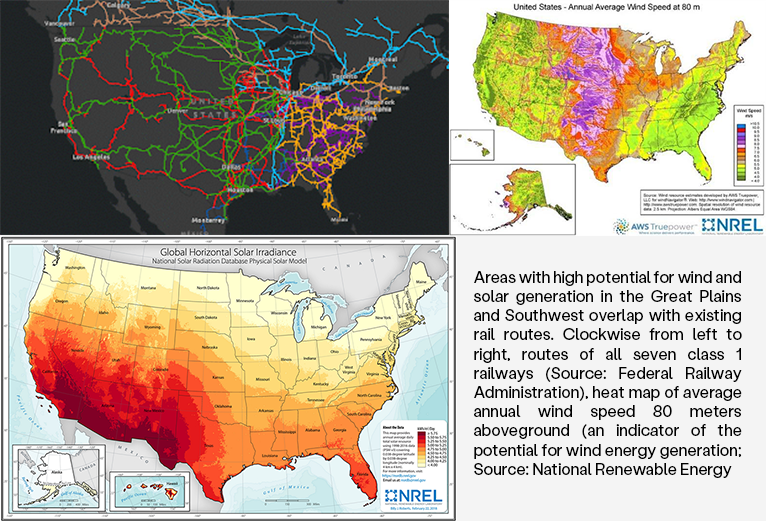

However, a new generation of private developers has proposed an innovative solution that bypasses these challenges: the construction of an underground nationwide HVDC network alongside existing rail corridors. Unlike aboveground transmission built through a mosaic of property owners’ holdings, this solution requires negotiation with only the seven major American rail companies. This approach also takes advantage of the proximity of these already-disturbed corridors to many areas with high renewable-energy potential (Figure 1), does not add visual pollution to the aboveground landscape, and would weatherproof grid infrastructure against natural disasters.

Areas with high potential for wind and solar generation in the Great Plains and Southwest overlap with existing rail routes. Clockwise from left to right, routes of all seven class 1 railways (Source: Federal Railway Administration), heat map of average annual wind speed 80 meters aboveground (an indicator of the potential for wind energy generation; Source: National Renewable Energy

Importantly, these benefits apply to co-location next to highways or existing transmission lines as well. While this memo focuses on rail co-location, co-location next to other infrastructure should be simultaneously pursued by first removing regulatory barriers as was recently enacted in Minnesota and promoting the efficiencies gained from all forms of infrastructure co-location to relevant stakeholders.

In addition to the political considerations discussed above, several recent advances in HVDC technology have driven costs low enough to make HVDC installation cost-competitive with installing high voltage alternating current (HVAC) lines (see FAQ for more details). As a result, incentivizing HVDC makes sense from perspectives beyond addressing climate change. The U.S. electric grid must be modernized to address pressing challenges beyond climate, such as the need for improved grid reliability and stability. Because HVDC transmission, unlike AC transmission, can maintain consistent power, voltage, and frequency, constructing a HVDC transmission network is a promising way to support the large-scale incorporation of renewable sources into our nation’s energy mix while simultaneously bolstering grid stability and efficiency, and spurring economic growth in rural areas.

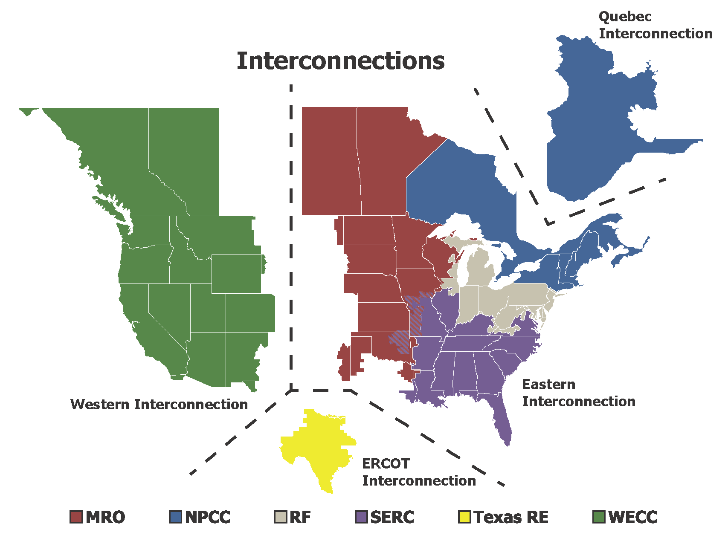

A nationwide HVDC network would also increase grid stability by connecting the four large interconnections that make up the shared American and Canadian power grid (Figure 2). Currently, the two largest of these interconnections—the Eastern and Western interconnections—manage 700 and 250 GW of electricity respectively. Yet, these interconnections are connected by transfer stations with a capacity of only about 1 GW. A recent study led by NREL modeled the economics of building a nationwide HVDC macrogrid that would tie the Eastern and Western interconnections together. The study concluded that such an investment would have a net benefit-to-cost ratio of 1.36 due to the possible ability for a nationwide HVDC grid to (i) shuttle renewable energy across the country as different power sources begin and end generation capabilities each day, and (ii) respond more nimbly to power outages in regions affected by natural disasters.

The four interconnections comprising the American and Canadian electricity grid: the Western, Eastern, ERCOT (Texas), and Quebec interconnections. Colors within the Eastern interconnection represent the territories of non-profit entities established to promote and enhance grid reliability within the territories shown on the map. These grid-reliability non-profits should not be confused with independent system operators (ISOs). (Source: National Electricity Reliability Council (NERC)).

Many private companies are already starting to realize an upgraded U.S. grid via new co-located HVDC transmission lines. For example, Minneapolis-based Direct Connect, with financial backing from American and international investors, has begun the permitting process for SOO Green, a buried HVDC line along a low-use railway that will link the Iowa countryside to the Chicago area. Direct Connect estimates that the SOO Green HVDC link will spur $1.5 billion of new renewable-energy development, create $2.2 billion of economic output in Iowa and Illinois, and create thousands of construction, operation, and maintenance jobs. Although geographically short, the line is also significant because it will join the Midwest (MISO) and PJM Independent System Operators (ISOs), two of the seven regional bodies that manage much of the United States’ grid. The combined territory of the MISO and PJM ISOs stretches from the wind-rich Great Plains to demand centers like Chicago and the Northeast corridor. Facilitating HVDC transmission in this project will allow renewable power to be efficiently funneled from regions that produce lots of energy to the regions that need it.

The Champlain Hudson Power Express joining NY-ISO and the Quebec interconnection is another example demonstrating the promise of buried, co-located HVDC transmission. The project is projected to save New York homes and businesses $17.3 billion over 30 years through wholesale electricity costs by supplying Quebec hydropower to New York City. The line is currently permitted and under construction and when finished will stretch 339 miles underneath Lake Champlain & the Hudson River and underground through New York State to a converter in Astoria, New York City. The terrestrial portions will be built alongside existing railroad and highway right of ways.

While these two projects and the handful of other buried and co-located HVDC lines currently in permitting, permitted, or under construction are important projects, far more transmission needs to be built to meet the U.S.’ climate goals. As a result, scaling underground co-located HVDC rapidly enough to achieve the transmission required for net-zero emissions in 2050 requires federal action to make these types of lines a more attractive proposition. The policy options outlined below would encourage other privately backed HVDC projects with the potential to boost rural economies while advancing climate action.

Plan of Action

The following policy recommendations would accelerate the development of a national HVDC network by stimulating privately funded construction of underground HVDC transmission lines located alongside existing rail corridors. Recommendations one and two are easily actionable rule changes that can be enacted by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) under existing authority. Recommendation three proposes that the DOE Grid Deployment Office should consider rail co-location in its NIETC designation process. Recommendation four is a more ambitious proposal for federal tax credits which would require Congressional action.

Recommendation 1. FERC should issue a new order that requires ISOs to review new renewable generation and new transmission projects on separate tracks to decrease permitting time delays.

New merchant transmission projects (transmission lines developed by private companies and not by rate-regulated utilities) such as SOO Green and the Champlain Hudson Power Express are often reviewed by ISOs in the same interconnection queue as new generation projects. Due to the high volume backlog of new, often speculative, renewable generation project proposals, transmission projects can wait for years before they are reviewed. This then creates a vicious cycle holding back the clean-energy sector: a delayed review of the transmission capabilities required by new renewable-generation projects ultimately chills the market for generation projects as well.

FERC recently reformed its regulations for interconnection requests (FERC Order 2023). FERC’s expectation is that switching to a first-ready, first-served system, clustering projects together in groups to be approved en masse, and increasing both submission deposits and withdrawal penalties should prevent speculative submissions and reduce approval times. Order 2023’s removal of the reasonable effects standard (i.e. hardening deadlines for transmission providers to complete impact and interconnection studies) as well as allowing multiple generation projects to share interconnections should also reduce wait times.

FERC Order 2023 is a laudable first step to address interconnection backlogs; however there is a chance that reality may not match FERC’s expectations. Therefore, FERC should continue to improve the regulatory regime in this area by issuing a new order that requires ISOs to review new renewable generation and new transmission projects on separate tracks. Such a rule would greatly decrease the permitting time for co-located HVDC transmission projects.

Recommendation 2. FERC should encourage ISOs to re-examine older transmission interconnection rules that are appropriate for AC transmission regulation but do not take into account the benefits of HVDC. External capacity rules, which govern the ability to trade power across ISO boundaries, are a specific area in need of action because they can create barriers to building HVDC transmission across ISO boundaries.

One granular example is described in SOO Green’s complaint to FERC about the PJM ISO (FERC Docket EL21-103). Under current rules set by the PJM ISO, energy generated outside of the PJM service area can participate in PJM’s energy marketplace only if grid operators can directly dispatch that energy. This rule was established because grid operators cannot otherwise control the free flow of power through cross-ISO AC transmission, but it results in the exclusion of external, non-dispatchable renewable energy resources from PJM’s market. However, HVDC lines offer the capacity to schedule current flow at pre-agreed upon times, allowing PJM to directly control transmission and negating the need to control energy dispatch. PJM should look for solutions to this issue from ISO New England and NYISO’s external capacity rules, which have enabled them to import external capacity through HVDC lines into their territories.

FERC should encourage PJM ISO to revise its external capacity rules to enable less burdensome pathways to market participation for external resources connecting through HVDC transmission. PJM can look to ISO New England and NYISO as examples.

Recommendation 3. As the DOE proposes possible National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors (NIETCs), it should pursue co-location with rail, highways, and existing transmission whenever possible.

Previous attempts by Congress to establish greater federal power over transmission siting and permitting have revolved around the DOE’s authority to designate areas as NIETCs. NIETCs are regions that the DOE identifies as particularly prone to grid congestion or transmission-capacity constraints. Creation of NIETCs was authorized by the Federal Power Act (Sec. 216), which also grants FERC the authority to supersede states’ permitting and siting decisions if the rejected transmission project is in a NIETC and meets certain conditions (including benefits to consumers (even those in other states), enhancement of energy independence, or if the project is “consistent with the public interest”). This “backstop” authority was created by the Energy Policy Act of 2005, was recently reformed in 2021’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and was further clarified by FERC Order 1977 through the creation of a landowner bill of rights.

While a laudable attempt to spur transmission investment and respect landowners, the revised authority in its current form is unlikely to lead to the sudden acceleration of transmission siting and permitting necessary to achieve the United States’ climate goals. This is because NIETC designation, as well as any FERC action under Section 216, (i) trigger the development of environmental impact statements under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and (ii) may still engender strong political opposition by states and landowners whose properties would be part of proposed routes but would not receive any benefits from transmission investments.

The DOE recently released a list of proposed NIETCs, which if designated would be the first corridors in the country. Some of the NIETCs were designed with co-location in mind, for example the NY – NE ISO link is located alongside roadways and mid-Atlantic routes are co-located with already existing transmission. However, rail co-location was not mentioned, yet the DOE’s proposed NIETCs overlap with the nation’s class 1 railways in many locations, especially in the Southwest and Midwest. In order to speed up the NEPA review process and reduce NIETC opposition, the DOE should i) consider discussing rail co-location in addition to highway and transmission infrastructure during the upcoming public engagement process, and ii) promote the possibility of co-location to transmission developers in all relevant NIETCs after they are officially designated.

Recommendation 4. Create federal tax credits to stimulate domestic manufacturing and construction of HVDC transmission, including HVDC lines along rail corridors.

Congress should create two federal investment tax credits (ITCs) to stimulate a market for American HVDC lines. One tax credit should be directed to American manufacturers of cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE) which serves as the material for the liner in HVDC cables. Since most producers are based in Asia, such an incentive would help ensure a reliable domestic supply of this essential material. The second tax credit should be directed to HVDC line developers who propose new regionally significant transmission projects that join ISOs or the three interconnections together. Since the United States’ grid grew in an ad-hoc, decentralized way, a Congressional tax credit of this type would further build on FERC’s recent order 1920, which requires transmission providers to think more big picture, long-term and strategically by developing a long-term regional transmission plan that covers at least the next 20 years.

Such a tax credit was recently introduced into Congress. In 2023, Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-NM) proposed a 30% ITC for “regionally significant” transmission projects which was also introduced in a companion bill by Rep. Steven Horsford, (D-Nev). Their Grid Resiliency Tax Credit Act would provide a 10-year credit for projects that begin building before 2033. The bill is currently under discussion by the Senate Finance committee and should be amended to also include a tax credit for XLPE manufacturers. The expiration of parts of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2025 will focus attention on tax legislation in the next Congress and offer a legislative window for transmission construction and component manufacturing tax credits. In the potentially acrimonious debate about the future of tax policy, transmission tax credits could be a rare point of agreement and an opportunity for both parties to invest in American manufacturing and infrastructure growth.

Conclusion

A significant increase in transmission capacity is needed to meet the United States’ efforts to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. Creating a nationwide HVDC transmission network would not only greatly aid the United States’ efforts to address climate change, it would also improve grid stability and provide sustained economic development in rural areas. Direct Connect’s SOO Green project and the Champlain Hudson Power Express are examples of innovative solutions to legitimate stakeholder concerns over environmental impacts and individual property rights – concerns that have plagued previous failed efforts to construct long-distance HVDC transmission. The federal government can stimulate private development of HVDC infrastructure via rule changes to the transmission interconnection process by FERC, promoting rail co-location in the NIETC design and designation process, and by passing new HVDC transmission-specific tax credits.

This idea was originally published on May 5, 2022; we’ve re-published this updated version on November 12, 2024.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Direct current (DC) runs continually in a single direction. DC became the standard current for American electricity early in the development of the U.S. grid, due largely to Thomas Edison’s endorsement. However, at that time DC could not be easily converted to different voltages, making it expensive and difficult to supply power to consumers since different end uses require different voltages. Alternating current (AC), or current that reverses direction at a set frequency, could be converted to different voltages and had its own prominent proponent in Nikola Tesla. Due to the lower costs associated with AC voltage conversion, AC became the technology of choice as city-wide and regional scale power plants and transmission developed in the early 20th century.

In general, AC transmission is more cost-effective for lines that cover short distances, while HVDC transmission is ideal for longer projects. This is mainly due to the physical properties of DC, which reduce power loss when compared to AC transmission over long distances. As a result, DC transmission is ideal for moving renewable energy generated in rural areas to areas of high demand.

An additional factor is the need for HVDC lines to convert to AC at the beginning and end of the line. Due to the history discussed above, most generation and end-use applications respectively generate and require AC power. As a result, the use of HVDC transmission usually involves two converter stations located at either end of the line. The development of voltage source converter (VSC) technology has significantly shrunk the land footprint required for siting converter stations (to as little as ~1 acre) and reduced power loss associated with conversion. While VSC stations are expensive (costing $100 million or more), the expenses of VSC technology begin to be balanced by the savings in efficiency gained through HVDC transmission at distances above 300 miles.

Additional factors that lower the costs for underground rail co-located lines are (i) that America’s fracking boom has led to significant technological advances in horizontal drilling, and (ii) the wealth of engineering experience accumulated by co-locating much of America’s fiber-optic network alongside roads or railways.

The current backlog is estimated to be 30 months or more, according to SOO Green’s first FERC complaint.

Yes, FERC has the authority to issue these proposed rule changes under Section 206 of the Federal Power Act (FPA), which states:

“Whenever the Commission, after a hearing held upon its own motion or upon complaint, shall find that any rate, charges, or classification demanded, observed, charged, or collected by any public utility for any transmission or sale subject to the jurisdiction of the Commission, or that any rule, regulation, practice, or contract affecting such rate, charge, or classification is unjust, unreasonable, unduly discriminatory or preferential, the Commission shall determine the just and reasonable rate, charge, classification, rule, regulation, practice, or contract to be thereafter observed and in force, and shall fix the same by order.”

FERC has the authority under Section 206 of the FPA to issue the proposed rule changes because the classification of HVDC transmission as generation by ISOs (recommendation 1) and ISO rules governing external capacity (recommendation 2) are practices and rules that affect the rates charged by public utilities.

Large-scale HVDC transmission projects do not meet the categorical exclusion criteria under the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) for transmission construction (<20 miles in length along previously disturbed rights of way; 10 C.F.R. 2021 Appendix B). As a result, environmental impact statements are required to be created by all relevant federal agencies (possibly including the Environmental Protection Agency as well as the Departments of Commerce, Energy, the Interior, Labor, and Transportation). All relevant state and local permitting requirements also apply.

To take advantage of the political momentum granted to the newly created DOE Undersecretary of Infrastructure and the relevant expertise within FERC, the new undersecretary, in partnership with FERC’s Office of Energy Policy and Innovation (OEPI), should together lead the collaborative effort by DOE and FERC to work with states, utilities, class 1 railways, and interested transmission developers. To expedite transmission development, efforts to bring representatives from these stakeholders to the table should begin as soon as possible. Once a quorum of interested parties has been established, the Infrastructure Undersecretary and FERC OEPI should facilitate the establishment of regular “transmission summits” to build consensus on possible transmission routes that meet the concerns of all parties.

When necessary, the Undersecretary of Infrastructure and OEPI should also include other relevant agencies and offices in these regularly scheduled planning summits. Possible DOE offices with valuable perspectives are the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations; the Office of Energy Efficiency, and Renewable Energy; and the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation (co-managed by the DOE and Department of Transportation (DOT)). Possible additional FERC offices include the Office of Energy Market Regulation and the newly created Office of Public Participation. Other relevant agencies include the National Railway Administration within DOT, the Department of Labor, and the Department of the Interior (since lines built in the West are very likely to cross federal land).

Because HVDC transmission is a young industry, coordination among all these agencies and all relevant stakeholders for rail co-located HVDC transmission to proactively develop a clear regulatory framework would greatly aid the maturation of HVDC transmission in America.

Tax credits for HVDC transmission projects and components are a logical extension of existing renewable energy tax credits designed to strengthen the positive economic effects of renewable energy growth in many rural American communities. The original renewable energy tax credits within the Energy Policy Acts of 1992 and 2005 were passed with large, bipartisan margins (93 – 3 and 85 – 12). A focused advocacy effort that unites all stakeholders who stand to benefit from these new proposed tax credits (including rural communities where new renewable generation will be spurred, railroad companies, HVDC developers and manufacturers, urban centers with high renewable demand) would generate the needed bipartisan support.

China leads the world in installed point-to-point HVDC transmission. China also recently opened the world’s first HVDC grid. Behind China, the European Union has made extensive investments in deploying point-to-point HVDC lines and is planning to develop an integrated European grid by requiring EU members to meet a 15% interconnection target (meaning that each country must be able to send 15% of its electricity to neighbors) by 2030. India, Brazil, Australia, and Singapore have opened or are planning ambitious HVDC projects as well.

A Public Jobs Board For A Fairer Political Appointee Hiring Process

Current hiring processes for political appointees are opaque and problematic; job openings are essentially closed off except to those in the right networks. To democratize hiring, the next administration should develop a public jobs board for non-Senate-confirmed political appointments, which includes a list of open roles and job descriptions. By serving as a one-stop shop for those interested in serving in an administration, an open jobs board would bring more skilled candidates into the administration, diversify the appointee workforce, expedite the hiring process, and improve government transparency.

Challenge and Opportunity

Hiring for federal political appointee positions is a broken process. Even though political appointees steer some of the federal government’s most essential functions, the way these individuals are hired lacks the rigor and transparency expected in most other fields.

Political appointment hiring processes are opaque, favoring privileged candidates already in policy networks. There is currently no standardized hiring mechanism for filling political appointee roles, even though new administrations must fill thousands of lower-level appointee positions. Openings are often shared only through word-of-mouth or internal networks, meaning that many strong candidates with relevant domain expertise may never be aware of available opportunities to work in an administration. Though the Plum Book (an annually updated list of political appointees) exists, it does not list vacancies, meaning outside candidates must still have insider information on who is hiring.

These closed hiring processes are deeply problematic because they lead to a non-diverse pool of applicants. For example, current networking-based processes benefit graduates of elite universities, and similar networking-based employment processes such as employee referral programs tend to benefit White men more than any other demographic group. We have experienced this opaque process firsthand at the Aspen Tech Policy Hub; though we have trained hundreds of science and technology fellows who are interested in serving as appointees, we are unaware of any that obtained political appointment roles by means other than networking.

Appointee positions often do not include formal job descriptions, making it difficult for outside candidates to identify roles that are a good fit. Most political appointee jobs do not include a written, formalized job description—a standard best practice across every other sector. A lack of job descriptions makes it almost impossible for outside candidates utilizing the Plum Book to understand what a position entails or whether it would be a good fit. Candidates that are being recruited typically learn more about position responsibilities through direct conversations with hiring managers, which again favors candidates who have direct connections to the hiring team.

Hiring processes are inefficient for hiring staff. The current approach is not only problematic for candidates; it is also inefficient for hiring staff. Through the current process, PPO or other hiring staff must sift through tens of thousands of resumes submitted through online resume bank submissions (e.g. the Biden administration’s “Join Us” form) that are not tailored to specific jobs. They may also end up directly reaching out to candidates that may not actually be interested in specific positions, or who lack required specialized skills.

Given these challenges, there is significant opportunity to reform the political appointment hiring process to benefit both applications and hiring officials.

Plan of Action

The next administration’s Presidential Personnel Office (PPO) should pilot a public jobs board for Schedule C and non-career Senior Executive Service political appointment positions and expand the job board to all non-Senate-confirmed appointments if the pilot is successful. This public jobs board should eventually provide a list of currently open vacancies, a brief description for each currently open vacancy that includes a job description and job requirements, and a process for applying to that position.

Having a more transparent and open jobs board with job descriptions would have multiple benefits. It would:

- Bring in more diverse applicants and strengthen the appointee workforce by broadening hiring pools;

- Require hiring managers to write out job descriptions in advance, allowing outside candidates to better understand job opportunities and hiring managers to pinpoint qualifications they are looking for;

- Expedite the hiring process since hiring managers will now have a list of qualified applicants for each position; and

- Improve government transparency and accessibility into critical public sector positions.

Additionally, an open jobs board will allow administration officials to collect key data on applicant background and use these data to improve recruitment going forward. For example, an open application process would allow administration officials to collect aggregate data on education credentials, demographics, and work experience, and modify processes to improve diversity as needed. Having an updated, open list of positions will also allow PPO to refer strong candidates to other open roles that may be a fit, as current processes make it difficult for administration officials or hiring managers to know what other open positions exist.

Implementing this jobs board will require two phases: (1) an initial phase where the transition team and PPO modify their current “Join Us” form to list 50-100 key initial hires the administration will need to make; and (2) a secondary phase where it builds a more fulsome jobs board, launched in late 2025, that includes all open roles going forward.

Phase 1. By early 2025, the transition team (or General Services Administration, in its transition support capacity) should identify 50-100 key Schedule C or non-career Senior Executive service hires they think the PPO will need to fill early in the administration, and launch a revised resume bank to collect applicants for these positions. The transition team should prioritize roles that a) are urgent needs for the new administration, b) require specialized skills not commonly found among campaign and transition staff (for instance technical or scientific knowledge), and c) have no clear candidate already identified. The transition team should then revise the current administration’s “Join Us” form to include this list of 50-100 soon-to-be vacant job roles, as well as provide a 2-3 sentence description of the job responsibilities, and allow outside candidates to explicitly note interest in these positions. This should be a relatively light lift, given the current “Join Us” form is fairly easy to build.

Phase 2. Early in the administration, PPO should build a larger, more comprehensive jobs board that should aim to go live in late 2025 and includes all open Schedule C or non-Senior Executive Service (SES) positions. Upon launch, this jobs board should include open jobs for whom no candidate has been identified, and any new Schedule C and non-SES appointments that are open going forward. As described in further detail in the FAQ section, every job listed should include a brief description of the position responsibilities and qualifications, and additional questions on political affiliation and demographics.

During this second phase, the PPO and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) should identify and track key metrics to determine whether it should be expanded to cover all non-Senate confirmed appointments. For example, PPO and OPM could compare the diversity of applicants, diversity of hires, number of qualified candidates who applied for a position, time-to-hire, and number of vacant positions pre- and post-implementation of the jobs board.

If the jobs board improves key metrics, PPO and OPM should expand the jobs board to all non-Senate confirmed appointments. This would include non-Senate confirmed Senior Executive Service appointee positions.

Conclusion

An open jobs board for political appointee positions is necessary to building a stronger and more diverse appointee workforce, and for improving government transparency. An open jobs board will strengthen and diversify the appointee workforce, require hiring managers to specifically write down job responsibilities and qualifications, reduce hiring time, and ultimately result in more successful hires.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

An open jobs board will attract many applicants, perhaps more than the PPO’s currently small team can handle. If the PPO is overwhelmed by the number of job applicants it can either directly forward resumes to hiring managers — thereby reducing burden on PPO itself — or consider hiring a vetted third-party to sort through submitted resumes and provide a smaller, more focused list of applicants for PPO to consider.

PPO can also include questions to enable candidates to be sorted by political experience and political alignment, so as (for instance) to favor those who worked on the president’s campaign.

Both phases of our recommendation would be a relatively light lift, and most costs would come from staff time. Phase 1 costs will solely include staff time; we suspect it will take ⅓ to ½ of an FTE’s time over 3 months to source the 50-100 high-priority jobs, write the job descriptions, and incorporate them into the existing “Join Us” form.

Phase 2 costs will include staff time and cost of deploying and maintaining the platform. We suspect it will take 4-5 months to build and test the platform, and to source the job descriptions. The cost of maintaining the Phase 2 platform will ultimately depend on the platform chosen. Ideally, this jobs board would be hosted on an easy-to-use platform like Google, Lever, or Greenhouse that can securely hold applicant data. If that proves too difficult, it could also be built on top of the existing USAJobs site.

PPO may be able to use existing government resources to help fund this effort. The PPO may be able to pull on personnel from the General Services Administration in their transition support capacity to assist with sourcing and writing job descriptions. PPO can also work with in-house technology teams at the U.S. Digital Service to actually build the platform, especially given they have considerable expertise in reforming hiring for federal technology positions.

Building a Comprehensive NEPA Database to Facilitate Innovation

The Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Innovation and Jobs Act are set to drive $300 billion in energy infrastructure investment by 2030. Without permitting reform, lengthy review processes threaten to make these federal investments one-third less effective at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. That’s why Congress has been grappling with reforming the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) for almost two years. Yet, despite the urgency to reform the law, there is a striking lack of available data on how NEPA actually works. Under these conditions, evidence-based policy making is simply impossible. With access to the right data and with thoughtful teaming, the next administration has a golden opportunity to create a roadmap for permitting software that maximizes the impact of federal investments.

Challenge and Opportunity

NEPA is a cornerstone of U.S. environmental law, requiring nearly all federally funded projects—like bridges, wildfire risk-reduction treatments, and wind farms—to undergo an environmental review. Despite its widespread impact, NEPA’s costs and benefits remain poorly understood. Although academics and the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) have conducted piecemeal studies using limited data, even the most basic data points, like the average duration of a NEPA analysis, remain elusive. Even the Government Accountability Office (GAO), when tasked with evaluating NEPA’s effectiveness in 2014, was unable to determine how many NEPA reviews are conducted annually, resulting in a report aptly titled “National Environmental Policy Act: Little Information Exists on NEPA Analyses.”

The lack of comprehensive data is not due to a lack of effort or awareness. In 2021, researchers at the University of Arizona launched NEPAccess, an AI-driven program aimed at aggregating publicly available NEPA data. While successful at scraping what data was accessible, the program could not create a comprehensive database because many NEPA documents are either not publicly available or too hard to access, namely Environmental Assessments (EAs) and Categorical Exclusions (CEs). The Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) also built a language model to analyze NEPA documents but contained their analysis to the least common but most complex category of environmental reviews, Environmental Impact Statements (EISs).

Fortunately, much of the data needed to populate a more comprehensive NEPA database does exist. Unfortunately, it’s stored in a complex network of incompatible software systems, limiting both public access and interagency collaboration. Each agency responsible for conducting NEPA reviews operates its own unique NEPA software. Even the most advanced NEPA software, SOPA used by the Forest Service and ePlanning used by the Bureau of Land Management, do not automatically publish performance data.

Analyzing NEPA outcomes isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s an essential foundation for reform. Efforts to improve NEPA software have garnered bipartisan support from Congress. CEQ recently published a roadmap outlining important next steps to this end. In the report, CEQ explains that organized data would not only help guide development of better software but also foster broad efficiency in the NEPA process. In fact, CEQ even outlines the project components that would be most helpful to track (including unique ID numbers, level of review, document type, and project type).

Put simply, meshing this complex web of existing softwares into a tracking database would be nearly impossible (not to mention expensive). Luckily, advances in large language models, like the ones used by NEPAccess and PNNL, offer a simpler and more effective solution. With properly formatted files of all NEPA documents in one place, a small team of software engineers could harness PolicyAI’s existing program to build a comprehensive analysis dashboard.

Plan of Action

The greatest obstacles to building an AI-powered tracking dashboard are accessing the NEPA documents themselves and organizing their contents to enable meaningful analysis. Although the administration could address the availability of these documents by compelling agencies to release them, inconsistencies in how they’re written and stored would still pose a challenge. That means building a tracking board will require open, ongoing collaboration between technologists and agencies.

- Assemble a strike team: The administration should form a cross-disciplinary team to facilitate collaboration. This team should include CEQ; the Permitting Council; the agencies responsible for conducting the greatest number of NEPA reviews, including the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; technologists from 18F; and those behind the PolicyAI tool developed by PNNL. It should also decide where the software development team will be housed, likely either at CEQ or the Permitting Council.

- Establish submission guidelines: When handling exorbitant amounts of data, uniform formatting ensures quick analysis. The strike team should assess how each agency receives and processes NEPA documents and create standardized submission guidelines, including file format and where they should be sent.

- Mandate data submission: The administration should require all agencies to submit relevant NEPA data annually, adhering to the submission guidelines set by the strike team. This process should be streamlined to minimize the burden on agencies while maximizing the quality and completeness of the data; if possible, the software development team should pull data directly from the agency. Future modernization efforts should include building APIs to automate this process.

- Build the system: Using PolicyAI’s existing framework, the development team should create a language model to feed a publicly available, searchable database and dashboard that tracks vital metadata, including:

- The project components suggested in CEQ’s E-NEPA report, including unique ID numbers, level of review, document type, and project type

- Days spent producing an environmental review (if available; this information may need to be pulled from agency case management materials instead)

- Page count of each environmental review

- Lead and supporting agencies

- Project location (latitude/longitude and acres impacted, or GIS information if possible)

- Other laws enmeshed in the review, including the Endangered Species Act, the National Historic Preservation Act, and the National Forest Management Act

- When clearly stated in a NEPA document, cost of producing the review

- When clearly stated in a NEPA document, staff hours used to produce the review

- When clearly stated in a NEPA document, jobs and revenue created by the project

- When clearly stated in a NEPA document, carbon emissions mitigated by the project

Conclusion

The stakes are high. With billions of dollars in federal climate and infrastructure investments on the line, a sluggish and opaque permitting process threatens to undermine national efforts to cut emissions. By embracing cutting-edge technology and prioritizing transparency, the next administration can not only reshape our understanding of the NEPA process but bolster its efficiency too.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

It’s estimated that only 1% of NEPA analyses are Environmental Impact Statements (EISs), 5% are Environmental Assessments (EAs), and 94% are Categorical Exclusions (CEs). While EISs cover the most complex and contentious projects, using only analysis of EISs to understand the NEPA process paints an extremely narrow picture of the current system. In fact, focusing solely on EISs provides an incomplete and potentially misleading understanding of the true scope and effectiveness of NEPA reviews.

The vast majority of projects undergo either an EA or are afforded a CE, making these categories far more representative of the typical environmental review process under NEPA. EAs and CEs often address smaller projects, like routine infrastructure improvements, which are critical to the nation’s broader environmental and economic goals. Ignoring these reviews means disregarding a significant portion of federal environmental decision-making; as a result, policymakers, agency staff, and the public are left with an incomplete view of NEPA’s efficiency and impact.

Using Home Energy Rebates to Support Market Transformation

Without market-shaping interventions, federal and state subsidies for energy-efficient products like heat pumps often lead to higher prices, leaving the overall market worse off when rebates end. This is a key challenge that must be addressed as the Department of Energy (DOE) and states implement the Inflation Reduction Act’s Home Electrification and Appliance Rebates (HEAR) program.

DOE should prioritize the development of evidence-based market-transformation strategies that states can implement with their HEAR funding. The DOE should use its existing allocation of administrative funds to create a central capability to (1) develop market-shaping toolkits and an evidence base on how state programs can improve value for money and achieve market transformation and (2) provide market-shaping program implementation assistance to states.

There are proven market-transformation strategies that can reduce costs and save consumers billions of dollars. DOE can look to the global public health sector for an example of what market-shaping interventions could do for heat pumps and other energy-efficient technologies. In that arena, the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) has shown how public funding can support market-based transformation, leading to sustainably lower drug and vaccine prices, new types of “all-inclusive” contracts, and improved product quality. Agreements negotiated by CHAI and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation have generated over $4 billion in savings for publicly financed health systems and improved healthcare for hundreds of millions of people.

Similar impact can be achieved in the market for heat pumps if DOE and states can supply information to empower consumers to purchase the most cost-effective products, offer higher rebates for those cost-effective products, and seek supplier discounts for heat pumps eligible for rebates.

Challenge and Opportunity

HEAR received $4.5 billion in appropriations from the Inflation Reduction Act and provides consumers with rebates to purchase and install high-efficiency electric appliances. Heat pumps, the primary eligible appliance, present a huge opportunity for lowering overall greenhouse gas emissions from heating and cooling, which makes up over 10% of global emissions. In the continental United States, studies have shown that heat pumps can reduce carbon emissions up to 93% compared to gas furnaces across their lifetime.

However, direct-to-consumer rebate programs have been shown to enable suppliers to increase prices unless these subsidies are used to reward innovation and reduce cost. If subsidies are dispersed and the program design is not aligned with a market-transformation strategy, the result will be a short-term boost in demand followed by a fall-off in consumer interest as prices increase and the rebates are no longer available. This is a problem because program funding for heat pump rebates will support only ~500,000 projects over the life of the program—but more than 50 million households will need to convert to heat pumps in order to decarbonize the sector.

HEAR aims to address this through Market Transformation Plans, which states are required to submit to DOE within a year after receiving the award. States will then need to obtain DOE approval before implementing them. We see several challenges with the current implementation of HEAR:

- Need for evidence: There is a lack of evidence and policy agreement on the best approaches for market transformation. The DOE provides a potpourri of areas for action, but no evidence of cost-effectiveness. Thus, there is no rational basis for states to allocate funding across the 10 recommended areas for action. There are no measurable goals for market transformation.

- Redundancy: It is wasteful and redundant to have every state program allocate administrative expenses to design market-transformation strategies incorporating some or all of the 10 recommended areas for action. There is nothing unique to Georgia, Iowa, or Vermont in creating a tool to better estimate energy savings. A best-in-class software tool developed by DOE or one of the states could be adapted for use in each state. Similarly, if a state develops insights into lower-cost ways to install heat pumps, these insights will be valuable in many other state programs. The best tools should be a public good made known to every state program.

Despite these challenges, DOE has a clear opportunity to increase the impact of HEAR rebates by providing program design support to states for market-transformation goals. To ensure a competitive market and better value for money, state programs need guidance on how to overcome barriers created by information asymmetry – meaning that HVAC contractors have a much better understanding of the technical and cost/benefit aspects of heat pumps than consumers do. Consumers cannot work with contractors to select a heat pump solution that represents the best value for money if they do not understand the technical performance of products and how operating costs are affected by Seasonal Energy Efficiency Rating, coefficient of performance, and utility rates. If consumers are not well-informed, market outcomes will not be efficient. Currently, consumers do not have easy access to critical information such as the tradeoff in costs between increased Seasonal Energy Efficiency Rating and savings on monthly utility bills.

Overcoming information asymmetry will also help lower soft costs, which is critical to lowering the cost of heat pumps. Based on studies conducted by New York State, Solar Energy Industries Association and DOE, soft costs run over 60% of project costs in some cases and have increased over the past 10 years.

There is still time to act, as thus far only a few states have received approval to begin issuing rebates and state market-transformation plans are still in the early stages of development.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Establish a central market transformation team to provide resources and technical assistance to states.

To limit cost and complexity at the state level for designing and staffing market-transformation initiatives, the DOE should set up central resources and capabilities. This could either be done by a dedicated team within the Office of State and Community Energy Programs or through a national lab. Funding would come from the 3% of program funds that DOE is allowed to use for administration and technical assistance.

This team would:

- Collect, centralize, and publish heat pump equipment and installation cost data to increase transparency and consumer awareness of available options.

- Develop practical toolkits and an evidence base on how to achieve market transformation most cost-effectively.

- Provide market-shaping program design assistance to states to create and implement market transformation programs.

Data collection, analysis, and consistent reporting are at the heart of what this central team could provide states. The DOE data and tools requirements guide already asks states to provide information on the invoice, equipment and materials, and installation costs for each rebate transaction. It is critical that the DOE and state programs coordinate on how to collect and structure this data in order to benefit consumers across all state programs.

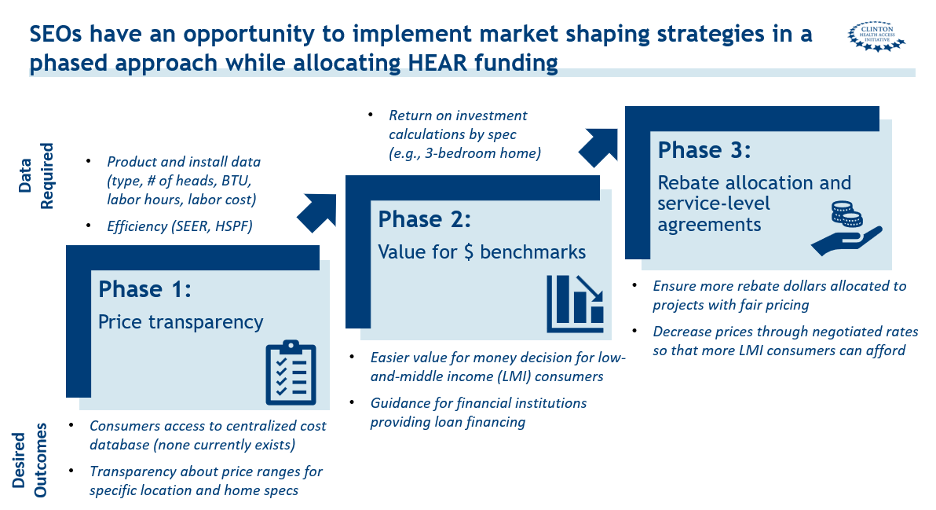

A central team could provide resources and technical assistance to State Energy Offices (SEOs) on how to implement market-shaping strategies in a phased approach.

Phase 1. Create greater price transparency and set benchmarks for pricing on the most common products supported by rebates.

The central market-transformation team should provide technical support to states on how to develop benchmarking data on prices available to consumers for the most common product offerings. Consumers should be able to evaluate pricing for heat pumps like they do for major purchases such as cars, travel, or higher education. State programs could facilitate these comparisons by having rebate-eligible contractors and suppliers provide illustrative bids for a set of 5–10 common heat pump installation scenarios, for example, installing a ductless mini-split in a three-bedroom home.

States should also require contractors to provide hourly rates for different types of labor, since installation costs are often ~70% of total project costs. Contractors should only be designated as recommended or preferred service providers (with access to HEAR rebates) if they are willing to share cost data.

In addition, the central market-transformation team could facilitate information-sharing and data aggregation across states to limit confusion and duplication of data. This will increase price transparency and limit the work required at the state level to find price information and integrate with product technical performance data.

Phase 2. Encourage price and service-level competition among suppliers by providing consumers with information on how to judge value for money.

A second area to improve market outcomes is by promoting competition. Price transparency supports this goal, but to achieve market transformation programs need to go further to help consumers understand what products, specific to their circumstances, offer best value for money.

In the case of a heat pump installation, this means taking account of fuel source, energy prices, house condition, and other factors that drive the overall value-for-money equation when achieving improved energy efficiency. Again, information asymmetry is at play. Many energy-efficiency consultants and HVAC contractors offer to advise on these topics but have an inherent bias to promoting their products and services. There are no easily available public sources of reliable benchmark price/performance data for ducted and ductless heat pumps for homes ranging from 1500 to 2700 square feet, which would cover 75% of the single-family homes in the United States.

In contrast, the commercial building sector benefits from very detailed cost information published on virtually every type of building material and specialty trade procedure. Data from sources such as RSMeans provides pricing and unit cost information for ductwork, electrical wiring, and mean hourly wage rates for HVAC technicians by region. Builders of newly constructed single-family homes use similar systems to estimate and manage the costs of every aspect of the new construction process. But a homeowner seeking to retrofit a heat pump into an existing structure has none of this information. Since virtually all rebates are likely to be retrofit installations, states and the DOE have a unique interest in making this market more competitive by developing and publishing cost/performance benchmarking data.

State programs have considerable leverage that can be used to obtain the information needed from suppliers and installers. The central market-transformation team should use that information to create a tool that provides states and consumers with estimates of potential bill savings from installation of heat pumps in different regions and under different utility rates. This information would be very valuable to low- and middle-income (LMI) households, who are to receive most of the funding under HEAR.

Phase 3. Use the rebate program to lower costs and promote best-value products by negotiating product and service-level agreements with suppliers and contractors and awarding a higher level of rebate to installations that represent best value for money.

By subsidizing and consolidating demand, SEOs will have significant bargaining power to achieve fair prices for consumers.

First, by leveraging relationships with public and private sector stakeholders, SEOs can negotiate agreements with best-value contractors, offering guaranteed minimum volumes in return for discounted pricing and/or longer warranty periods for participating consumers. This is especially important for LMI households, who have limited home improvement budgets and experience disproportionately higher energy burdens, which is why there has been limited uptake of heat pumps by LMI households. In return, contractors gain access to a guaranteed number of additional projects that can offset the seasonal nature of the business.

Second, as states design the formulas used to distribute rebates, they should be encouraged to create systems that allocate a higher proportion of rebates to projects quoted at or below the benchmark costs and a smaller proportion or completely eliminate the rebates to projects higher than the benchmark. This will incentivize contractors to offer better value for money, as most projects will not proceed unless they receive a substantial rebate. States should also adopt a similar process as New York and Wisconsin in creating a list of approved contractors that adhere to “reasonable price” thresholds.

Recommendation 2. For future energy rebate programs, Congress and DOE can make market transformation more central to program design.

In future clean energy legislation, Congress should direct DOE to include the principles recommended above into the design of energy rebate programs, whether implemented by DOE or states. Ideally, that would come with either greater funding for administration and technical assistance or dedicated funding for market-transformation activities in addition to the rebate program funding.

For future rebate programs, DOE could take market transformation a step further by establishing benchmarking data for “fair and reasonable” prices from the beginning and requiring that, as part of their applications, states must have service-level agreements in place to ensure that only contractors that are at or below ceiling prices are awarded rebates. Establishing this at the federal level will ensure consistency and adoption at the state level.

Conclusion

The DOE should prioritize funding evidence-based market transformation strategies to increase the return on investment for rebate programs. Learning from U.S.-funded programs for global public health, a similar approach can be applied to the markets for energy-efficient appliances that are supported under the HEAR program. Market shaping can tip the balance towards more cost-effective and better-value products and prevent rebates from driving up prices. Successful market shaping will lead to sustained uptake of energy-efficient appliances by households across the country.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

There is compelling evidence that federal and state subsidies for energy-efficient products can lead to price inflation, particularly in the clean energy space. The federal government has offered tax credits in the residential solar space for many years. While there has been a 64% reduction in the ex-factory photovoltaic module price for residential panels, the total residential installed cost per kWh has increased. The soft costs, including installation, have increased over the same period and are now ~65% or more of total project costs.

In 2021, the National Bureau of Economic Research linked consumer subsidies with firms charging higher prices, in the case of Chinese cell phones. The researchers found that by introducing competition for eligibility, through techniques such as commitment to price ceilings, price increases were mitigated and, in some cases, even reduced, creating more consumer surplus. This type of research along with the observed price increases after tax credits for solar show the risks of government subsidies without market-shaping interventions and the likely detrimental long-term impacts.

CHAI has negotiated over 140 agreements for health commodities supplied to low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) with over 50 different companies. These market-shaping agreements have generated $4 billion in savings for health systems and touched millions of lives.

For example, CHAI collaborated with Duke University and Bristol Myers Squibb to combat hepatitis-C, which impacts 71 million people, 80% of whom are in LMICs, mostly in Southeast Asia and Africa [see footnote]. The approval in 2013 of two new antiviral drugs transformed treatment for high-income countries, but the drugs were not marketed or affordable in LMICs. Through its partnerships and programming, CHAI was able to achieve initial pricing of $500 per treatment course for LMICs. Prices fell over the next six years to under $60 per treatment course while the cost in the West remained at over $50,000 per treatment course. This was accomplished through ceiling price agreements and access programs with guaranteed volume considerations.

CHAI has also worked closely with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to develop the novel market-shaping intervention called a volume guarantee (VG), where a drug or diagnostic test supplier agrees to a price discount in exchange for guaranteed volume (which will be backstopped by the guarantor if not achieved). Together, they negotiated a six-year fixed price VG with Bayer and Merck for contraceptive implants that reduced the price by 53% for 40 million units, making family planning more accessible for millions and generating $500 million in procurement savings.

Footnote: Hanafiah et al., Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: New estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence, J Hepatol. (2013), Volume 57, Issue 4, Pages 1333–1342; Gower E, Estes C, Blach S, et al. Global epidemiology and genotype distribution of the hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. (2014),61(1 Suppl):S45-57; World Health Organization. Work conducted by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Global Hepatitis Report 2017.

Many states are in the early stages of setting up the program, so they have not yet released their implementation plans. However, New York and Wisconsin indicate which contractors are eligible to receive rebates through approved contractor networks on their websites. Once a household applies for the program, they are put in touch with a contractor from the approved state network, which they are required to use if they want access to the rebate. Those contractors are approved based on completion of training and other basic requirements such as affirming that pricing will be “fair and reasonable.” Currently, there is no detail about specific price thresholds that suppliers need to meet (as an indication of value for money) to qualify.

DOE’s Data and Tools Requirements document lays out the guidelines for states to receive federal funding for rebates. This includes transaction-level data that must be reported to the DOE monthly, including the specs of the home, the installation costs, and the equipment costs. Given that states already have to collect this data from contractors for reporting, this proposal recommends that SEOs streamline data collection and standardize it across all participating states, and then publish summary data so consumers can get an accurate sense of the range of prices.

There will be natural variation between homes, but by collecting a sufficient sample size and overlaying efficiency metrics like Seasonal Energy Efficiency Rating, Heating Seasonal Performance Factor, and coefficient of performance, states will be able to gauge value for money. Rewiring America and other nonprofits have software that can quickly make these calculations to help consumers understand the return on investment for higher-efficiency (and higher-cost) heat pumps given their location and current heating/cooling costs.

In the global public health markets, CHAI has promoted price transparency for drugs and diagnostic tests by publishing market surveys that include product technical specifications, and links to product performance studies. We show the actual prices paid for similar products in different countries and by different procurement agencies. All this information has helped public health programs migrate to the best-in-class products and improve value for money. Stats could do the same to empower consumers to choose best-in-class and best-value products and contractors.

Driving Product Model Development with the Technology Modernization Fund

The Technology Modernization Fund (TMF) currently funds multiyear technology projects to help agencies improve their service delivery. However, many agencies abdicate responsibility for project outcomes to vendors, lacking the internal leadership and project development teams necessary to apply a product model approach focused on user needs, starting small, learning what works, and making adjustments as needed.

To promote better outcomes, TMF could make three key changes to help agencies shift from simply purchasing static software to acquiring ongoing capabilities that can meet their long-term mission needs: (1) provide education and training to help agencies adopt the product model; (2) evaluate investments based on their use of effective product management and development practices; and (3) fund the staff necessary to deliver true modernization capacity.

Challenge and Opportunity

Technology modernization is a continual process of addressing unmet needs, not a one-time effort with a defined start and end. Too often, when agencies attempt to modernize, they purchase “static” software, treating it like any other commodity, such as computers or cars. But software is fundamentally different. It must continuously evolve to keep up with changing policies, security demands, and customer needs.

Presently, agencies tend to rely on available procurement, contracting, and project management staff to lead technology projects. However, it is not enough to focus on the art of getting things done (project management); it is also critically important to understand the art of deciding what to do (product management). A product manager is empowered to make real-time decisions on priorities and features, including deciding what not to do, to ensure the final product effectively meets user needs. Without this role, development teams typically march through a vast, undifferentiated, unprioritized list of requirements, which is how information technology (IT) projects result in unwieldy failures.

By contrast, the product model fosters a continuous cycle of improvement, essential for effective technology modernization. It empowers a small initial team with the right skills to conduct discovery sprints, engage users from the outset and throughout the process, and continuously develop, improve, and deliver value. This approach is ultimately more cost effective, results in continuously updated and effective software, and better meets user needs.

However, transitioning to the product model is challenging. Agencies need more than just infrastructure and tools to support seamless deployment and continuous software updates – they also need the right people and training. A lean team of product managers, user researchers, and service designers who will shape the effort from the outset can have an enormous impact on reducing costs and improving the effectiveness of eventual vendor contracts. Program and agency leaders, who truly understand the policy and operational context, may also require training to serve effectively as “product owners.” In this role, they work closely with experienced product managers to craft and bring to life a compelling product vision.

These internal capacity investments are not expensive relative to the cost of traditional IT projects in government, but they are currently hard to make. Placing greater emphasis on building internal product management capacity will enable the government to more effectively tackle the root causes that lead to legacy systems becoming problematic in the first place. By developing this capacity, agencies can avoid future costly and ineffective “modernization” efforts.

Plan of Action

The General Services Administration’s Technology Modernization Fund plays a crucial role in helping government agencies transition from outdated legacy systems to modern, secure, and efficient technologies, strengthening the government’s ability to serve the public. However, changes to TMF’s strategy, policy, and practice could incentivize the broader adoption of product model approaches and make its investments more impactful.

The TMF should shift from investments in high-cost, static technologies that will not evolve to meet future needs towards supporting the development of product model capabilities within agencies. This requires a combination of skilled personnel, technology, and user-centered approaches. Success should be measured not just by direct savings in technology but by broader efficiencies, such as improvements in operational effectiveness, reductions in administrative burdens, and enhanced service delivery to users.

While successful investments may result in lower costs, the primary goal should be to deliver greater value by helping agencies better fulfill their missions. Ultimately, these changes will strengthen agency resilience, enabling them to adapt, scale, and respond more effectively to new challenges and conditions.

Recommendation 1. The Technology Modernization Board, responsible for evaluating proposals, should:

- Assess future investments based on the applicant’s demonstrated competencies and capacities in product ownership and management, as well as their commitment to developing these capabilities. This includes assessing proposed staffing models to ensure the right teams are in place.

- Expand assessment criteria for active and completed projects beyond cost savings, to include measurements of improved mission delivery, operational efficiencies, resilience, and adaptability.

Recommendation 2. The TMF Program Management Office, responsible for stewarding investments from start to finish, should:

- Educate and train agencies applying for funds on how to adopt and sustain the product model.

- Work with the General Services Administration’s 18F to incorporate TMF project successes and lessons learned into a continuously updated product model playbook for government agencies that includes guidance on the key roles and responsibilities needed to successfully own and manage products in government.

- Collaborate with the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) to ensure that agencies have efficient and expedited pathways for acquiring the necessary talent, utilizing appropriate assessments to identify and onboard skilled individuals.

Recommendation 3. Congress should:

- Encourage agencies to set up their own working capital funds under the authorities outlined in the TMF legislation.

- Explore the barriers to product model funding in the current budgeting and appropriations processes for the federal government as a whole and develop proposals for fitting them to purpose.

- Direct OPM to reduce procedural barriers that hinder swift and effective hiring.

Conclusion

The TMF should leverage its mandate to shift agencies towards a capabilities-first mindset. Changing how the program educates, funds, and assesses agencies will build internal capacity and deliver continuous improvement. This approach will lead to better outcomes, both in the near and long terms, by empowering agencies to adapt and evolve their capabilities to meet future challenges effectively.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Congress established TMF in 2018 “to improve information technology, and to enhance cybersecurity across the federal government” through multiyear technology projects. Since then, more than $1 billion has been invested through the fund across dozens of federal agencies in four priority areas.

Introducing Certification of Technical Necessity for Resumption of Nuclear Explosive Testing

The United States currently observes a voluntary moratorium on explosive nuclear weapons testing. At the same time, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) is required by law to maintain the capability to conduct an underground nuclear explosive test at the Nevada National Security Site, if directed to do so by the U.S. president.

Restarting U.S. nuclear weapons testing could have very negative security implications for the United States unless it was determined to be an absolute technical or security necessity. A restart of U.S. nuclear testing for any reason could open the door for China, Russia, Pakistan, and India to do the same, and make it even harder to condemn North Korea for its testing program. This would have significant security consequences for the United States and global environmental impacts.

The United States conducted over 1,000 nuclear weapons tests before the 1991 testing moratorium took effect. It was able to do so with the world’s most advanced diagnostic and data detection equipment, which enabled the US to conduct advanced computer simulations after the end of testing. Neither Russia or China conducted as many tests, and many fewer of those were able to collect advanced metrics, hampering these countries’ ability to match American simulation capabilities. Enabling Russia and China to resume testing could narrow the technical advantage the United States has held in testing data since the testing moratorium went into effect in 1992.

Aside from the security loss, nuclear testing would also have long-lasting radiological effects at the test site itself, including radiation contamination in the soil and groundwater, and the chance of venting into the atmosphere. Despite these downsides, a future president has the legal authority—for political or other reasons—to order a resumption of nuclear testing. Ensuring any such decision is more democratic and subject to a broader system of political accountability could be achieved by creating a more integrated approval process, based on scientific or security needs. To this end, Congress should pass legislation requiring the NNSA administrator to certify that an explosive nuclear test is technically necessary to rectify an existing problem or doubt in U.S. nuclear surety before a test can be conducted.

Challenges and Opportunities

The United States is party to the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty, which prohibits atmospheric tests, and the Threshold Ban Treaty of 1974, limiting underground tests of more than 150 kilotons of explosive yield. In 1992, the United States also established a legal moratorium on nuclear testing through the Hatfield-Exon-Mitchell Amendment, passed during the George H.W. Bush Administration. After extending this moratorium in 1993, the United States, Russia, and China also signed the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) in 1996, which prohibits nuclear explosions. However, none of the Annex 2 (nuclear armed) states have ratified the CTBT, which prevents it from entering into force.