Not Accessible: Federal Policies Unnecessarily Complicate Funding to Support Differently Abled Researchers. We Can Change That.

Persons with disabilities (PWDs) are considered the largest minority in the nation and in the world. There are existing policies and procedures from agencies, directorates, or funding programs that provide support for Accessibility and Accommodations (A&A) in federally funded research efforts. Unfortunately, these policies and procedures all have different requirements, processes, deadlines, and restrictions. This lack of standardization can make it difficult to acquire the necessary support for PWDs by placing the onus on them or their Principal Investigators (PIs) to navigate complex and unique application processes for the same types of support.

This memo proposes the development of a standardized, streamlined, rolling, post-award support mechanism to provide access and accommodations for PWDs as they conduct research and disseminate their work through conferences and convenings. The best case scenario is one wherein a PI or their institution can simply submit the identifying information for the award that has been made and then make a direct request for the support needed for a given PWD to work on the project. In a multi-year award such a request should be possible at any time within the award period.

This could be implemented by a single, streamlined policy adopted by all agencies with the process handled internally. Or, by a new process across agencies under Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) or Office of Management and Budget (OMB) that handles requests for accessibility and accommodations at federally funded research sites and at federally funded convenings. An alternative to a single streamlined policy across these agencies might be a new section in the uniform guidance for federal funding agencies, also known as 2 CFR 200.

This memo focuses on Federal Open Science funding programs to illustrate the challenges in getting A&A funding requests supported. The authors have taken an informal look at agencies outside of science and technology funding. We found similar challenges across federal grantmaking in the Arts and Humanities, Social Services, and Foreign Relations and Aid entities. Similar issues likely exist in private philanthropy as well.

Challenge and Opportunity

Deaf/hard-of-hearing (DHH), Blind/low-vision (BLV), and other differently abled academicians, senior personnel, students, and post-doctoral fellows engaged in federally funded research face challenges in acquiring accommodations for accessibility. These include, but are not limited to:

- Human-provided ASL-English interpreting and interview transcription services for the DHH and non-DHH participants. While there are some applications of artificial intelligence (AI) that show promise on the transcription side, there’s a long way to go on ASL interpretation in an AI provided model versus the use of human interpreters.

- Visual and Pro-tactile interpreting/descriptive services for the BLV participants

- Adaptive lab equipment and computing peripherals

- Accessibility support or remediation for physical sites

Having these services available is crucial for promoting an inclusive research environment on a larger scale.

Moving to a common, post-award process:

- Allows the PI and the reviewers more time and space to focus on the core research efforts being described in the initial proposal

- Removes any chance of the proposal funding being taken out of consideration due to higher costs in comparison to similar proposals in the pool

- Creates a standard, replicable pathway for seeking accommodations once the overall proposal has been funded. This is especially true if the support comes from a single process across all federal funding programs rather than within each agency.

- Allows for flexibility in accommodations. Needs vary from person-to-person and case-to-case. For example, in the case of workplace accommodations for DHH team members, one full-time researcher may request full-time ASL interpretation on-site, while another might prefer to work primarily through digital text channels; only requiring ASL interpretation for staff meetings and other group activities.

- Potentially reduces federal government financial and human resources currently expended in supporting such requests by eliminating duplication of effort across agencies or, at minimum streamlining processes within agencies.

Such a process might follow these steps below. The example below is from the National Science Foundation (NSF), but the same, or similar process could be done within any agency:

- PI receives notification of grant award from NSF. PI identifies need for A & A services at start, or at any time during the grant period

- PI (or SRS staff) submits request for A&A funding support to NSF. Request includes NSF program name and award number, the specifics of the requested A & A support, a budget justification and three vendor quotes (if needed)

- Use of funds is authorized, and funding is released to PI’s institution and acquisition would follow their standard purchasing or contracting procedures

- PI submits receipts/ paid vendor invoice to funding body

- PI cites and documents use of funds in annual report, or equivalent, to NSF

Current Policies and Practices

Pre-Award Funding

Principal Investigators (PIs) who request A&A support for themselves or for other members of the research team are sometimes required to apply for it in their initial grant proposals. This approach has several flaws.

First and foremost, this funding process reduces the direct application of research dollars for these PIs and their teams compared to other researchers in the same program. Simply put, if two applicants are applying for a $100,000 grant, and one needs to fund $10,000 worth of accommodations, services, and equipment out of the award, they have $10,000 less to pursue the proposed research activities. This essentially creates a “10% A & A tax” on the overall research funding request.

Lived Experience Example

In a real world example, the author and his colleague, the late Dr. Mel Chua, were awarded a $60,000, one year grant to do a qualitative research case study as part of the Ford Foundation Critical Digital Infrastructure Research cohort. As Dr. Chua was Deaf, the PIs pointed out to Ford that $10,000 worth of support services would be needed to cover costs for

- American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters during the qualitative interviews and advisory committee meetings

- Transcription of the interviews

- ASL Interpreting for conference dissemination and collection of comments at formal and informal meetings during those conferences

We communicated the fact that spending general research award money on those services would reduce the research work the funds were awarded to support. The Ford Foundation understood and provided an additional $10,000 as post-award funding to cover those services. Ford did not inform the PIs as to whether that support came from another directed set of funds for A&A support or from discretionary dollars within the foundation.

Second, it can be limiting for the funded project to work with or hire PWDs as co-PIs, students, or if they weren’t already part of the original grant proposal. For example, suppose a research project is initially awarded funding for four years without A&A support and then a promising team member who is a PWD appears on the scene in year three who would require it. In this case, PIs then must:

- Reallocate research dollars meant for other uses within the grant to support A&A;

- Find other funding to support those needs within their institution;

- Navigate the varied post-award support landscape, sometimes going so far as to write an entirely new full proposal with a significant review timeline, to try to get support. If this happens off cycle, the funding might not even arrive until the last few months of the fourth year.

- Or, not hire the person in question because they can’t provide the needed A&A.

Post-Award Funding

Some agencies have programs for post-award supplemental funding that address the challenges described above. While these are well-intentioned, many are complicated and often have different timelines, requirements, etc. In some cases, a single supplemental funding source may be addressing all aspects of diversity, equity and inclusion as well as A&A. The needs and costs in the first three categories are significantly different than in the last. Some post-award pools come from the same agency’s annual allocation program-wide. If those funds have been primarily expended on the initial awards for the solicitation, there may be little, or no money left to support post-award funding for needed accommodations. The table below briefly illustrates the range of variability across a subset of representative supplemental funding programs. There are links in the top row of the table to access the complete program information. Beyond the programs in this table, more extensive lists of NSF and NIH offerings are provided by those agencies. One example is the NSF Dear Colleague Letter Persons with Disabilities – STEM Engagement and Access.

Ideally these policies and procedures, and others like them, would be replaced by a common, post-award process. PIs or their institutions would simply submit the identifying information on the grant that had been awarded and the needs for Accommodations and Accessibility to support team members with disabilities at any time during the grant period.

Plan of Action

The OSTP, possibly in a National Science and Technology Council interworking group process,, should conduct an internal review of the A&A policies and procedures for grant programs from federal scientific research aligned agencies. This could be led by OSTP directly or under their auspices and led by either NSF or the National Institute of Health (NIH). Participants would be relevant personnel from DOE, DOD, NASA, USDA, EPA, NOAA, NIST and HHS, at minimum. The goal should be to create a draft of a single, streamlined policy and process, post-award, for all federal grant programs or a new section in the uniform guidance for federal funding agencies.

There should be an analysis of the percentages, size and amounts of awards currently being made to support A&A in research funding grant programs. It’s not clear how the various funding ranges and caps listed in the table above were determined or if they meet the needs. One goal of this analysis would be to determine how well current needs within and across agencies are being met and what future needs might be.

A second goal would be to look at the level of duplication of effort and scope of manpower savings that might be attained by moving to a single, streamlined policy. This might be a coordinated process between OMB and OSTP or a separate one done by OMB. No matter how it is coordinated, an understanding of these issues should inform whatever new policies or new additions to 2 CFR 200 would emerge.

A third goal of this evaluation could be to consider if the support for A&A post-award funding might best be served by a single entity across all federal grants, consolidating the personnel expertise and policy and process recommendations in one place. It would be a significant change, and could require an act of Congress to achieve, but from the point of view of the authors it might be the most efficient way to serve grantees who are PWDs.

Once the initial reviews as described above, or a similar process is completed, the next step should be a convening of stakeholders outside of the federal government with the purpose of providing input to the streamlined draft policy. These stakeholder entities could include, but should not be limited to, the National Association for the Deaf, The American Foundation for the Blind, The American Association of People with Disabilities and the American Diabetes Association. One of the goals of that convening should be a discussion, and decision, as to whether a period of public comment should be put in place as well, before the new policy is adopted.

Conclusion

The above plan of action should be pursued so that more PWDS will be able to participate, or have their participation improved, in federally funded research. A policy like the one described above lays the groundwork and provides a more level playing field for Open Science to become more accessible and accommodating.It also opens the door for streamlined processes, reduced duplication of effort and greater efficiency within the engine of Federal Science support.

Acknowledgments

The roots of this effort began when the author and Dr. Mel Chua and Stephen Jacobs received funding for their research as part of the first Critical Digital Infrastructure research cohort and were able to negotiate for accessibility support services outside their award. Those who provided input on the position paper this was based on are:

- Dr. Mel Chua, Independent Researcher

- Dr. Liz Hare, Quantitative Geneticist, Dog Genetics LLC

- Dr. Christopher Kurz, Professor and Director of Mathematics and Science Language and Learning Lab, National Technical Institute for the Deaf

- Luticha Andre-Doucette, Catalyst Consulting

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Based on the percentage of PWDs in the general population size, conference funders should assume that some of their presenters or attendees will need accommodations. Funding from federal agencies should be made available to provide an initial minimum-level of support for necessary A & A. The event organizers should be able to apply for additional support above the minimum level if needed, provided participant requests are made within a stated time before the event. For example, a stipulated deadline of six weeks before the event to request supplemental accommodation, so that the organizers can acquire what’s needed within thirty days of the event.

Yes, in several ways. In general, most of the support needed for these is in service provision vs. hardware/software procurement. However, understanding the breadth and depth of issues surrounding human services support is more complex and outside the experience of most PIs running a conference in their own scientific discipline.

Again, using the example of DHH researchers who are attending a conference. A conference might default to providing a team of two interpreters during the conference sessions, as two per hour is the standard used. Should a group of DHH researchers attend the conference and wish to go to different sessions or meetings during the same convening, the organizers may not have provided enough interpreters to support those opportunities.

By providing interpretation for formal sessions only, DHH attendees are excluded from a key piece of these events, conversations outside of scheduled sessions. This applies to both formally planned and spontaneous ones. They might occur before, during, or after official sessions, during a meal offsite, etc. Ideally interpreters would be provided for these as well.

These issues, and others related to other groups of PWDs, are beyond the experience of most PIs who have received event funding.

There are some federal agency guides produced for addressing interpreting and other concerns, such as the “Guide to Developing a Language Access Plan” Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). These are often written to address meeting needs of full-time employees on site in office settings. These generally cover various cases not needed by a conference convener and may not address what they need for their specific use case. It might be that the average conference chair and their logistics committee is a simply stated set of guidelines to address their short-term needs for their event. Additionally, a directory of where to hire providers with the appropriate skill sets and domain knowledge to meet the needs of PWDs attending their events would be an incredible aid to all concerned.

The policy review process outlined above should include research to determine a base level of A & A support for conferences. They might recommend a preferred federal guide to these resources or identify an existing one.

Promoting Fairness in Medical Innovation

There is a crisis within healthcare technology research and development, wherein certain groups due to their age, gender, or race and ethnicity are under-researched in preclinical studies, under-represented in clinical trials, misunderstood by clinical practitioners, and harmed by biased medical technology. These issues in turn contribute to costly disparities in healthcare outcomes, leading to losses of $93 billion a year in excess medical-care costs, $42 billion a year in lost productivity, and $175 billion a year due to premature deaths. With the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare, there’s a risk of encoding and recreating existing biases at scale.

The next Administration and Congress must act to address bias in medical technology at the development, testing and regulation, and market-deployment and evaluation phases. This will require coordinated effort across multiple agencies. In the development phase, science funding agencies should enforce mandatory subgroup analysis for diverse populations, expand funding for under-resourced research areas, and deploy targeted market-shaping mechanisms to incentivize fair technology. In the testing and regulation phase, the FDA should raise the threshold for evaluation of medical technologies and algorithms and expand data-auditing processes. In the market-deployment and evaluation phases, infrastructure should be developed to perform impact assessments of deployed technologies and government procurement should incentivize technologies that improve health outcomes.

Challenge and Opportunity

Bias is regrettably endemic in medical innovation. Drugs are incorrectly dosed to people assigned female at birth due to historical exclusion of women from clinical trials. Medical algorithms make healthcare decisions based on biased health data, clinically disputed race-based corrections, and/or model choices that exacerbate healthcare disparities. Much medical equipment is not accessible, thus violating the Americans with Disabilities Act. And drugs, devices, and algorithms are not designed with the lifespan in mind, impacting both children and the elderly. Biased studies, technology, and equipment inevitably produce disparate outcomes in U.S. healthcare.

The problem of bias in medical innovation manifests in multiple ways: cutting across technological sectors in clinical trials, pervading the commercialization pipeline, and impeding equitable access to critical healthcare advances.

Bias in medical innovation starts with clinical research and trials

The 1993 National Institutes of Health (NIH) Revitalization Act required federally funded clinical studies to (i) include women and racial minorities as participants, and (ii) break down results by sex and race or ethnicity. As of 2019, the NIH also requires inclusion of participants across the lifespan, including children and older adults. Yet a 2019 study found that only 13.4% of NIH-funded trials performed the mandatory subgroup analysis, and challenges in meeting diversity targets continue into 2024 . Moreover, the increasing share of industry-funded studies are not subject to Revitalization Act mandates for subgroup analysis. These studies frequently fail to report differences in outcomes by patient population as a result. New requirements for Diversity Action Plans (DAPs), mandated under the 2023 Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act, will ensure drug and device sponsors think about enrollment of diverse populations in clinical trials. Yet, the FDA can still approve drugs and devices that are not in compliance with their proposed DAPs, raising questions around weak enforcement.

The resulting disparities in clinical-trial representation are stark: African Americans represent 12% of the U.S. population but only 5% of clinical-trial participants, Hispanics make up 16% of the population but only 1% of clinical trial participants, and sex distribution in some trials is 67% male. Finally, many medical technologies approved prior to 1993 have not been reassessed for potential bias. One outcome of such inequitable representation is evident in drug dosing protocols: sex-aware prescribing guidelines exist for only a third of all drugs.

Bias in medical innovation is further perpetuated by weak regulation

Algorithms

Regulation of medical algorithms varies based on end application, as defined in the 21st Century Cures Act. Only algorithms that (i) acquire and analyze medical data and (ii) could have adverse outcomes are subject to FDA regulation. Thus, clinical decision-support software (CDS) is not regulated even though these technologies make important clinical decisions in 90% of U.S. hospitals. The FDA has taken steps to try and clarify what CDS must be considered a medical device, although these actions have been heavily criticized by industry. Finally, the lack of regulatory frameworks for generative AI tools is leading to proliferation without oversight.

Even when a medical algorithm is regulated, regulation may occur through relatively permissive de novo pathways and 510(k) pathways. A de novo pathway is used for novel devices determined to be low to moderate risk, and thus subject to a lower burden of proof with respect to safety and equity. A 510(k) pathway can be used to approve a medical device exhibiting “substantial equivalence” to a previously approved device, i.e., it has the same intended use and/or same technological features. Different technical features can be approved so long as there are no questions raised around safety and effectiveness.

Medical algorithms approved through de novo pathways can be used as predicates for approval of devices through 510(k) pathways. Moreover, a device approved through a 510(k) pathway can remain on the market even if its predicate device was recalled. Widespread use of 510(k) approval pathways has generated a “collapsing building” phenomenon, wherein many technologies currently in use are based on failed predecessors. Indeed, 97% of devices recalled between 2008 to 2017 were approved via 510(k) clearance.

While DAP implementation will likely improve these numbers, for the 692 AI-ML enabled medical devices, only 3.6% reported race or ethnicity, 18.4% reported age, and only .9% include any socioeconomic information. Further, less than half did detailed analysis of algorithmic performance and only 9% included information on post-market studies, raising the risk of algorithmic bias following approvals and broad commercialization.

Even more alarming is evidence showing that machine learning can further entrench medical inequities. Because machine learning medical algorithms are powered by data from past medical decision-making, which is rife with human error, these algorithms can perpetuate racial, gender, and economic bias. Even algorithms demonstrated to be ‘unbiased’ at the time of approval can evolve in biased ways over time, with little to no oversight from the FDA. As technological innovation progresses, especially generative AI tools, an intentional focus on this problem will be required.

Medical devices

Currently, the Medical Device User Fee Act requires the FDA to consider the least burdensome appropriate means for manufacturers to demonstrate the effectiveness of a medical device or to demonstrate a device’s substantial equivalence. This requirement was reinforced by the 21st Century Cures Act, which also designated a category for “breakthrough devices” subject to far less-stringent data requirements. Such legislation shifts the burden of clinical data collection to physicians and researchers, who might discover bias years after FDA approval. This legislation also makes it difficult to require assessments on the differential impacts of technology.

Like medical algorithms, many medical devices are approved through 510(k) exemptions or de novo pathways. The FDA has taken steps since 2018 to increase requirements for 510(k) approval and ensure that Class III (high-risk) medical devices are subject to rigorous pre-market approval, but problems posed by equivalence and limited diversity requirements remain.

Finally, while DAPs will be required for many devices seeking FDA approval, the recommended number of patients in device testing is shockingly low. For example, currently, only 10 people are required in a study of any new pulse oximeter’s efficacy and only 2 of those people need to be “darkly pigmented”. This requirement (i) does not have the statistical power necessary to detect differences between demographic groups, and (i) does not represent the composition of the U.S. population. The standard is currently under revision after immense external pressure. FDA-wide, there are no recommended guidelines for addressing human differences in device design, such as pigmentation, body size, age, and pre-existing conditions.

Pharmaceuticals

The 1993 Revitalization Act strictly governs clinical trials for pharmaceuticals and does not make recommendations for adequate sex or genetic diversity in preclinical research. The results are that a disproportionately high number of male animals are used in research and that only 5% of cell lines used for pharmaceutical research are of African descent. Programs like All of Us, an effort to build diverse health databases through data collection, are promising steps towards improving equity and representation in pharmaceutical research and development (R&D). But stronger enforcement is needed to ensure that preclinical data (which informs function in clinical trials) reflects the diversity of our nation.

Bias in medical innovation are not tracked post-regulatory approval

FDA-regulated medical technologies appear trustworthy to clinicians, where the approval signals safety and effectiveness. So, when errors or biases occur (if they are even noticed), the practitioner may blame the patient for their lifestyle rather than the technology used for assessment. This in turn leads to worse clinical outcomes as a result of the care received.

Bias in pulse oximetry is the perfect case study of a well-trusted technology leading to significant patient harm. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many clinicians and patients were using oximeter technology for the first time and were not trained to spot factors, like melanin in the skin, that cause inaccurate measurements and impact patient care. Issues were largely not attributed to the device. This then leads to underreporting of adverse events to the FDA — which is already a problem due to the voluntary nature of adverse-event reporting.

Even when problems are ultimately identified, the federal government is slow to respond. The pulse oximeter’s limitations in monitoring oxygenation levels across diverse skin tones was identified as early as the 1990s. 34 years later, despite repeated follow-up studies indicating biases, no manufacturer has incorporated skin-tone-adjusted calibration algorithms into pulse oximeters. It required the large Sjoding study, and the media coverage it garnered around delayed care and unnecessary deaths, for the FDA to issue a safety communication and begin reviewing the regulation.

Other areas of HHS are stepping up to address issues of bias in deployed technologies. A new ruling by the HHS Office of Civil Rights (OCR) on Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act requires covered providers and institutions (i.e. any receiving federal funding) to identify their use of patient care decision support tools that directly measure race, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability, and to make reasonable efforts to mitigate the risk of discrimination from their use of these tools. Implementation of this rule will depend on OCR’s enforcement, and yet it provides another route to address bias in algorithmic tools.

Differential access to medical innovation is a form of bias

Americans face wildly different levels of access to new medical innovations. As many new innovations have high cost points, these drugs, devices, and algorithms exist outside the price range of many patients, smaller healthcare institutions and federally funded healthcare service providers, including the Veterans Health Administration, federally qualified health centers and the Indian Health Service. Emerging care-delivery strategies might not be covered by Medicare and Medicaid, meaning that patients insured by CMS cannot access the most cutting-edge treatments. Finally, the shift to digital health, spurred by COVID-19, has compromised access to healthcare in rural communities without reliable broadband access.

Finally, the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) has a commitment to have all programs and projects consider equity in their design. To fulfill ARPA-H’s commitment, there is a need for action to ensure that medical technologies are developed fairly, tested with rigor, deployed safely, and made affordable and accessible to everyone.

Plan of Action

The next Administration should launch “Healthcare Innovation for All Americans” (HIAA), a whole of government initiative to improve health outcomes by ensuring Americans have access to bias-free medical technologies. Through a comprehensive approach that addresses bias in all medical technology sectors, at all stages of the commercialization pipeline, and in all geographies, the initiative will strive to ensure the medical-innovation ecosystem works for all. HIAA should be a joint mandate of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Office of Science Technology and Policy (OSTP) to work with federal agencies on priorities of equity, non-discrimination per Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act and increasing access to medical innovation, and initiative leadership should sit at both HHS and OSTP.

This initiative will require involvement of multiple federal agencies, as summarized in the table below. Additional detail is provided in the subsequent sections describing how the federal government can mitigate bias in the development phase; testing, regulation, and approval phases; and market deployment and evaluation phases.

Three guiding principles should underlie the initiative:

- Equity and non-discrimination should drive action. Actions should seek to improve the health of those who have been historically excluded from medical research and development. We should design standards that repair past exclusion and prevent future exclusion.

- Coordination and cooperation are necessary. The executive and legislative branches must collaborate to address the full scope of the problem of bias in medical technology, from federal processes to new regulations. Legislative leadership should task the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to engage in ongoing assessment of progress towards the goal of achieving bias-free and fair medical innovation.

- Transparent, evidence-based decision making is paramount. There is abundant peer-reviewed literature that examines bias in drugs, devices, and algorithms used in healthcare settings — this literature should form the basis of a non-discrimination approach to medical innovation. Gaps in evidence should be focused on through deployed research funding. Moreover, as algorithms become ubiquitous in medicine, every effort should be made to ensure that these algorithms are trained on representative data of those experiencing a given healthcare condition.

Addressing bias at the development phase

The following actions should be taken to address bias in medical technology at the innovation phase:

- Enforce parity in government-funded research. For clinical research, NIH should examine the widespread lack of adherence to regulations requiring that government funded clinical trials report sex, racial or ethnicity, and age breakdown of trial participants. Funding should be reevaluated for non-compliant trials. For preclinical research, NIH should require gender parity in animal models and representation of diverse cell lines used in federally funded studies.

- Deploy funding to address research gaps. Where data sources for historically marginalized people are lacking, such as for women’s cardiovascular health, NIH should deploy strategic, targeted funding programs to fill these knowledge gaps. This could build on efforts like the Initiative on Women’s Health Research. Increased funding should include resources for underrepresented groups to participate in research and clinical trials through building capacity in community organizations. Results should be added to a publicly available database so they can be accessed by designers of new technologies. Funding programs should also be created to fill gaps in technology, such as in diagnostics and treatments for high-prevalence and high-burden uterine diseases like endometriosis (found in 10% of reproductive-aged people with uteruses).

- Invest in research into healthcare algorithms and databases. Given the explosion of algorithms in healthcare decision-making, NIH and NSF should launch a new research program focused on the study, evaluation, and application of algorithms in healthcare delivery, and on how artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) can exacerbate healthcare inequities. The initial request for proposals should focus on design strategies for medical algorithms that mitigate bias from data or model choices.

- Task ARPA-H with developing metrics for equitable medical technology development. ARPA-H should prioritize developing a set of procedures and metrics for equitable development of medical technology. Once developed, these processes should be rapidly deployed across ARPA-H, as well as published for potential adoption by additional federal agencies, industry, and other stakeholders. ARPA-H could also collaborate with NIST on standards setting with NIST and ASTP on relevant standards setting. For instance, NIST has developed an AI Risk Management Framework and the ONC engages in setting standards that achieve equity by design. CMS could use resultant standards for Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements.

- Leverage procurement as a demand-signal for medical technologies that work for diverse populations. As the nation’s largest healthcare system, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) can generate demand-signals for bias-free medical technologies through its procurement processes and market-shaping mechanisms. For example, the VA could put out a call for a pulse oximeter that works equally well across the entire range of human skin pigmentation and offer contracts for the winning technology.

Addressing bias at the testing, regulation, and approval phases

The following actions should be taken to address bias in medical innovation at the testing, regulation, and approval phases:

- Raise the threshold for FDA evaluation of devices and algorithms. Equivalency necessary to receive 510(k) clearance should be narrowed. For algorithms, this would involve consideration of whether the datasets for machine learning tactics used by the new device and its predicate are similar. For devices (including those that use algorithms), this would require tightening the definition of “same intended use” (currently defined as a technology having the same functionality as one previously approved by the FDA) as well as eliminating the approval of new devices with “different technological characteristics” (the application of one technology to a new area of treatment in which that technology is untested).

- Evaluate FDA’s guidance on specific technology groups for equity. Requirements for the safety of a given drug, medical device, or algorithm should have the statistical power necessary to detect differences between demographic groups and represent all end-users of the technology..

- Establish a data bank for auditing medical algorithms. The newly established Office of Digital Transformation within the FDA should create a “data bank” of healthcare images and datasets representative of the U.S. population, which could be done in partnership with the All of Us program. Medical technology developers could use the data bank to assess the performance of medical algorithms across patient populations. Regulators could use the data bank to ground claims made by those submitting a technology for FDA approval.

- Allow data submitted to the FDA to be examined by the broader scientific community. Currently, data submitted to the FDA as part of its regulatory-approval process is kept as a trade secret and not released pre-authorization to researchers. Releasing the data via an FDA-invited “peer review” step in the regulation of high-risk technologies, like automated decision-making algorithms, Class III medical devices, and drugs, will ensure that additional, external rigor is applied to the technologies that could cause the most harm due to potential biases.

- Establish an enforceable AI Bill of Rights. The federal government and Congress should create protections for necessary uses of artificial intelligence (AI) identified by OSTP. Federally funded healthcare centers, like facilities part of the Veterans Health Administration, could refuse to buy software or technology products that violate this “AI Bill of Rights” through changes to federal acquisition regulation (FAR).

Addressing bias at the market deployment and evaluation phases

- Strengthen reporting mechanisms at the FDA. Healthcare providers, who are often closest to the deployment of medical technologies, should be made mandatory reporters to the FDA of all witnessed adverse events related to bias in medical technology. In addition, the FDA should require the inclusion of unique device identifiers (UDIs) in adverse-response reporting. Using this data, Congress should create a national and publicly accessible registry that uses UDIs to track post-market medical outcomes and safety.

- Require impact assessments of deployed technologies. Congress must establish systems of accountability for medical technologies, like algorithms, that can evolve over time. Such work could be done by passing the Algorithmic Accountability Act which would require companies that create “high-risk automated decision systems” to conduct impact assessments reviewed by the FTC as frequently as necessary.

- Assess disparities in patient outcomes to direct technical auditing. AHRQ should be given the funding needed to fully investigate patient-outcome disparities that could be caused by biases in medical technology, such as its investigation into the impacts of healthcare algorithms on racial and ethnic disparities. The results of this research should be used to identify technologies that the FDA should audit post-market for efficacy or the FTC should investigate. CMS and its accrediting agencies can monitor these technologies and assess whether they should receive Medicare and Medicaid funding.

- Review reimbursement guidelines that are dependent on medical technologies with known bias. CMS should review its national coverage determinations for technologies, like pulse oximetry, that are known to perform differently across populations. For example, pulse oximeters can be used to determine home oxygen therapy provision, thus potentially excluding darkly-pigmented populations from receiving this benefit.

- Train physicians to identify bias in medical technologies and identify new areas of specialization. ED should work with medical schools to develop curricula training physicians to identify potential sources of bias in medical technologies and ensuring that physicians understand how to report adverse events to the FDA. In addition, ED should consider working with the American Medical Association to create new medical specialties that work at the intersection of technology and care delivery.

- Ensure that technologies developed by ARPA-H have an enforceable access plan. ARPA-H will produce cutting-edge technologies that must be made accessible to all Americans. ARPA-H should collaborate with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to develop strategies for equitable delivery of these new technologies. A cost-effective deployment strategy must be identified to service federally-funded healthcare institutions like Veterans Health Administration hospitals and clinical, federally qualified health centers, and Indian Health Service.

- Create a fund to support digital health technology infrastructure in rural hospitals. To capitalize on the $65 billion expansion of broadband access allocated in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill, HRSA should deploy strategic funding to federally qualified health centers and rural health clinics to support digital health strategies — such as telehealth and mobile health monitoring — and patient education for technology adoption.

A comprehensive road map is needed

The GAO should conduct a comprehensive investigation of “black box” medical technologies utilizing algorithms that are not transparent to end users, medical providers, and patients. The investigation should inform a national strategic plan for equity and non-discrimination in medical innovation that relies heavily on algorithmic decision-making. The plan should include identification of noteworthy medical technologies leading to differential healthcare outcomes, creation of enforceable regulatory standards, development of new sources of research funding to address knowledge gaps, development of enforcement mechanisms for bias reporting, and ongoing assessment of equity goals.

Timeline for action

Realizing HIAA will require mobilization of federal funding, introduction of regulation and legislation, and coordination of stakeholders from federal agencies, industry, healthcare providers, and researchers around a common goal of mitigating bias in medical technology. Such an initiative will be a multi-year undertaking and require funding to enact R&D expenditures, expand data capacity, assess enforcement impacts, create educational materials, and deploy personnel to staff all the above.

Near-term steps that can be taken to launch HIAA include issuing a public request for information, gathering stakeholders, engaging the public and relevant communities in conversation, and preparing a report outlining the roadmap to accomplishing the policies outlined in this memo.

Conclusion

Medical innovation is central to the delivery of high-quality healthcare in the United States. Ensuring equitable healthcare for all Americans requires ensuring that medical innovation is equitable across all sectors, phases, and geographies. Through a bold and comprehensive initiative, the next Administration can ensure that our nation continues leading the world in medical innovation while crafting a future where healthcare delivery works for all.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

HIAA will be successful when medical policies, projects, and technologies yield equitable health care access, treatment, and outcomes. For instance, success would yield the following outcomes:

- Representation in preclinical and clinical research equivalent to the incidence of a studied condition in the general population.

- Research on a disease condition funded equally per affected patient.

- Existence of data for all populations facing a given disease condition.

- Medical algorithms that have equal efficacy across subgroup populations.

- Technologies that work equally well in testing as they do when deployed to the market.

- Healthcare technologies made available and affordable to all care facilities.

Regulation alone cannot close the disparity gap. There are notable gaps in preclinical and clinical research data for women, people of color, and other historically underrepresented groups that need to be filled. There are also historical biases encoded in AI/ML decision making algorithms that need to be studied and rectified. In addition, the FDA’s role is to serve as a safety check on new technologies — the agency has limited oversight over technologies once they are out on the market due to the voluntary nature of adverse reporting mechanisms. This means that agencies like the FTC and CMS need to be mobilized to audit high-risk technologies once they reach the market. Eliminating bias in medical technology is only possible through coordination and cooperation of federal agencies with each other as well as with partners in the medical device industry, the pharmaceutical industry, academic research, and medical care delivery.

A significant focus of the medical device and pharmaceutical industries is reducing the time to market for new medical devices and drugs. Imposing additional requirements for subgroup analysis and equitable use as part of the approval process could work against this objective. On the other hand, ensuring equitable use during the development and approval stages of commercialization will ultimately be less costly than dealing with a future recall or a loss of Medicare or Medicaid eligibility if discriminatory outcomes are discovered.

Healthcare disparities exist in every state in America and are costing billions a year in economic growth. Some of the most vulnerable people live in rural areas, where they are less likely to receive high-quality care because costs of new medical technologies are too high for the federally qualified health centers that serve one in five rural residents as well as rural hospitals. Furthermore, during continued use, a biased device creates adverse healthcare outcomes that cost taxpayers money. A technology functioning poorly due to bias can be expensive to replace. It is economically imperative to ensure technology works as expected, as it leads to more effective healthcare and thus healthier people.

U.S. Energy Security Compacts: Enhancing American Leadership and Influence with Global Energy Investment

This policy proposal was incubated at the Energy for Growth Hub and workshopped at FAS in May 2024.

Increasingly, U.S. national security priorities depend heavily on bolstering the energy security of key allies, including developing and emerging economies. But U.S. capacity to deliver this investment is hamstrung by critical gaps in approach, capability, and tools.

The new administration should work with Congress to give the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) the mandate and capacity to lead the U.S. interagency in implementing ‘Energy Security Compacts’, bilateral packages of investment and support for allies whose energy security is closely tied to core U.S. priorities. This would require minor amendments to the Millennium Challenge Act of 2003 to add a fourth business line to MCC’s Compact operations and grant the agency authority to coordinate an interagency working group contributing complementary tools and resources.

This proposal presents an opportunity to deliver on global energy security, an issue with broad appeal and major national security benefits. This initiative would strengthen economic partnerships with allies overseas, who consistently rank energy security as a top priority; enhance U.S. influence and credibility in advancing global infrastructure; and expand growing markets for U.S. energy technology. This proposal is built on the foundations and successes of MCC, a signature achievement of the G.W. Bush administration, and is informed by lessons learned from other initiatives launched by previous presidents of both parties.

Challenge and Opportunity

More than ever before, U.S. national security depends on bolstering the energy security of key allies. Core examples include:

- Securing physical energy assets: In countries under immediate or potential military threat, the U.S. may seek to secure vulnerable critical energy infrastructure, restore energy services to local populations, and build a foundation for long-term restoration.

- Countering dependence on geostrategic competitors: U.S. allies’ reliance on geostrategic competitors for energy supply or technologies poses short- and long-term threats to national security. Russia is building large nuclear reactors in major economies including Turkey, Egypt, India, and Bangladesh; has signed agreements to supply nuclear technology to at least 40 countries; and has agreed to provide training and technical assistance to at least another 14. Targeted U.S. support, investment, and commercial diplomacy can head off such dependence by expanding competition.

- Driving economic growth and enduring diplomatic relationships: Many developing and emerging economies face severe challenges in providing reliable, affordable electricity to their populations. This hampers basic livelihoods; constrains economic activity, job creation, and internet access; and contributes to deteriorating economic conditions driving instability and unrest. Of all the constraints analyses conducted by MCC since its creation, roughly half identified energy as a country’s top economic constraint. As emerging economies grow, their economic stability has an expanding influence over global economic performance and security. In coming decades, they will require vast increases in reliable energy to grow their manufacturing and service industries and employ rapidly growing populations. U.S. investment can provide the foundation for market-driven growth and enduring diplomatic partnerships.

- Diversifying supply chains: Many crucial technologies depend on minerals sourced from developing economies without reliable electricity. For example, Zambia accounts for about 4% of global copper supply and would like to scale up production. But recurring droughts have shuttered the country’s major hydropower plant and led to electricity outages, making it difficult for mining operations to continue or grow. Scaling up the mining and processing of key minerals in developing economies will require investment in improving power supply.

The U.S. needs a mechanism that enables quick, efficient, and effective investment and policy responses to the specific concerns facing key allies. Currently, U.S. capacity to deliver such support is hamstrung by key gaps in approach, capabilities, and tools. The most salient challenges include:

A project-by-project approach limits systemic impact: U.S. overseas investment agencies including the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), the U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA), and the Export-Import Bank (EXIM) are built to advance individual commercial energy transactions across many different countries. This approach has value–but is insufficient in cases where the goal is to secure a particular country’s entire energy system by building strong, competitive markets. That will require approaching the energy sector as a complex and interconnected system, rather than a set of stand-alone transactions.

Diffusion of tools across the interagency hinders coordination. The U.S. has powerful tools to support energy security–including through direct investment, policy support, and technical and commercial assistance–but they are spread across at least nine different agencies. Optimizing deployment will require efficient coordination, incentives for collaboration; and less fragmented engagement with private partners.

Insufficient leverage to incentivize reforms weakens accountability. Ultimately, energy security depends heavily on decisions made by the partner country’s government. In many cases, governments need to make tough decisions and advance key reforms before the U.S. can help crowd in private capital. Many U.S. agencies provide technical assistance to strengthen policy and regulatory frameworks but lack concrete mechanisms to incentivize these reforms or make U.S. funding contingent on progress.

Limited tools supporting vital enabling public infrastructure blocks out private investment. The most challenging bottleneck to modernizing and strengthening a power sector is often not financing new power generation (which can easily attract private investment under the right conditions), but supporting critical enabling infrastructure including grid networks. In most emerging markets, these are public assets, wholly or partially state-owned. However, most U.S. energy finance tools are designed to support only private sector-led investments. This effectively limits their effectiveness to the generation sector, which already attracts far more capital than transmission or distribution.

To succeed, an energy security investment mechanism should:

- Enable investment highly tailored to the specific needs and priorities of partners;

- Provide support across the entire energy sector value chain, strengthening markets to enable greater direct investment by DFC and the private sector;

- Co-invest with partner countries in shared priorities, with strong accountability mechanisms.

Plan of Action

The new administration should work with Congress to give the Millennium Challenge Corporation the mandate to implement ‘Energy Security Compacts’ (ESCs) addressing the primary constraints to energy security in specific countries, and to coordinate the rest of the interagency in contributing relevant tools and resources. This proposal builds on and reflects key lessons learned from previous efforts by administrations of both parties.

Each Energy Security Compact would include the following:

- A process led by MCC and the National Security Council (NSC) to identify priority countries.

- An analysis jointly conducted by MCC and the partner country on the key constraints to energy security.

- Negotiation, led by MCC with support from NSC, of a multi-year Energy Security Compact, anchored by MCC support for a specific set of investments and reforms, and complemented by relevant contributions from the interagency. The Energy Security Compact would define agency-specific responsibilities and include clear objectives and measurable targets.

- Implementation of the Energy Security Compact, led by MCC and NSC. To manage this process, MCC and NSC would co-lead an Interagency Working Group comprising representatives from all relevant agencies.

- Results reporting, based on MCC’s top-ranked reporting process, to the National Security Council and Congress.

This would require the following congressional actions:

- Amend the Millennium Challenge Act of 2003: Grant MCC the expanded mandate to deploy Energy Security Compacts as a fourth business line. This should include language applying more flexible eligibility criteria to ESCs, and broadening the set of countries in which MCC can operate when implementing an ESC. Give MCC the mandate to co-lead an interagency working group with NSC.

- Plus up MCC Appropriation: ESCs can be launched as a pilot project in a few markets. But ultimately, the model’s success and impact will depend on MCC appropriations, including for direct investment and dedicated staff. MCC has a track record of outstanding transparency in evaluating its programs and reporting results.

- Strengthen DFC through reauthorization. The ultimate success of ESCs hinges on DFC’s ability to deploy more capital in the energy sector. DFC’s congressional authorization expires in September 2025, presenting an opportunity to enhance the agency’s reach and impact in energy security. Key recommendations for reauthorization include: 1) Addressing the equity scoring challenge; and 2) Raising DFC’s maximum contingent liability to $100 billion.

- Budget. The initiative could operate under various budget scenarios. The model is specifically designed to be scalable, based on the number of countries with which the U.S. wants to engage. It prioritizes efficiency by drawing on existing appropriations and authorities, by focusing U.S. resources on the highest priority countries and challenges, and by better coordinating the deployment of various U.S. tools.

This proposal draws heavily on the successes and struggles of initiatives from previous administrations of both parties. The most important lessons include:

- From MCC: The Compact model works. Multi-year Compact agreements are an effective way to ensure country buy-in, leadership, and accountability through the joint negotiation process and the establishment of clear goals and metrics. Compacts are also an effective mechanism to support hard infrastructure because they provide multi-year resources.

- From MCC: Investments should be based on rigorous analysis. MCC’s Constraints Analyses identify the most important constraints to economic growth in a given country. That same rigor should be applied to energy security, ensuring that U.S. investments target the highest impact projects, including those with the greatest positive impact on crowding in additional private sector capital.

- From Power Africa: Interagency coordination can work. Coordinating implementation across U.S. agencies is a chronic challenge. But it is essential to ESCs–and to successful energy investment more broadly. The ESC proposal draws on lessons learned from the Power Africa Coordinator’s Office. Specifically, joint-leadership with the NSC focuses effort and ensures alignment with broader strategic priorities. A mechanism to easily transfer funds from the Coordinator’s Office to other agencies incentivizes collaboration, and enables the U.S. to respond more quickly to unanticipated needs. And finally, staffing the office with individuals seconded from relevant agencies ensures that staff understand the available tools, how they can be deployed effectively, and how (and with whom) to work with to ensure success. Legislative language creating a Coordinator’s Office for ESCs can be modeled on language in the Electrify Africa Act of 2015, which created Power Africa’s interagency working group.

Conclusion

The new administration should work with Congress to empower the Millennium Challenge Corporation to lead the U.S. interagency in crafting ‘Energy Security Compacts’. This effort would provide the U.S. with the capability to coordinate direct investment in the energy security of a partner country and contribute to U.S. national priorities including diversifying energy supply chains, investing in the economic stability and performance of rapidly growing markets, and supporting allies with energy systems under direct threat.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

MCC’s model already includes multi-year Compacts targeting major constraints to economic growth. The agency already has the structure and skills to implement Energy Security Compacts in place, including a strong track record of successful investment across many energy sector compacts. MCC enjoys a strong bipartisan reputation and consistently ranks as the world’s most transparent bilateral development donor. Finally, MCC is unique among U.S. agencies in being able to put large-scale grant capital into public infrastructure, a crucial tool for energy sector support–particularly in emerging and developing economies. Co-leading the design and implementation of ESCs with the NSC will ensure that MCC’s technical skills and experience are balanced with NSC’s view on strategic and diplomatic goals.

This proposal supports existing proposed legislative changes to increase MCC’s impact by expanding the set of countries eligible for support. The Millennium Challenge Act of 2003 currently defines the candidate country pool in a way that MCC has determined prevents it from “considering numerous middle-income countries that face substantial threats to their economic development paths and ability to reduce poverty.” Expanding that country pool would increase the potential for impact. Secondly, the country selection process for ESCs should be amended to include strategic considerations and to enable participation by the NSC.

America’s Teachers Innovate: A National Talent Surge for Teaching in the AI Era

Thanks to Melissa Moritz, Patricia Saenz-Armstrong, and Meghan Grady for their input on this memo.

Teaching our young children to be productive and engaged participants in our society and economy is, alongside national defense, the most essential job in our country. Yet the competitiveness and appeal of teaching in the United States has plummeted over the past decade. At least 55,000 teaching positions went unfilled this year, with long-term annual shortages set to double to 100,000 annually. Moreover, teachers have little confidence in their self-assessed ability to teach critical digital skills needed for an AI enabled future and in the profession at large. Efforts in economic peer countries such as Canada or China demonstrate that reversing this trend is feasible. The new Administration should announce a national talent surge to identify, scale, and recruit into innovative teacher preparation models, expand teacher leadership opportunities, and boost the profession’s prestige. “America’s Teachers Innovate” is an eight-part executive action plan to be coordinated by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), with implementation support through GSA’s Challenge.Gov and accompanied by new competitive priorities in existing National Science Foundation (NSF), Department of Education (ED), Department of Labor (DoL), and Department of Defense education (DoDEA) programs.

Challenge and Opportunity

Artificial Intelligence may add an estimated $2.6 trillion to $4.4 trillion annually to the global economy. Yet, if the U.S. is not able to give its population the proper training to leverage these technologies effectively, the U.S. may witness a majority of this wealth flow to other countries over the next few decades while American workers are automated from, rather than empowered by, AI deployment within their sectors. The students who gain the digital, data, and AI foundations to work in tandem with these systems – currently only 5% of graduating high school students in the U.S. – will fare better in a modern job market than the majority who lack them. Among both countries and communities, the AI skills gap will supercharge existing digital divides and dramatically compound economic inequality.

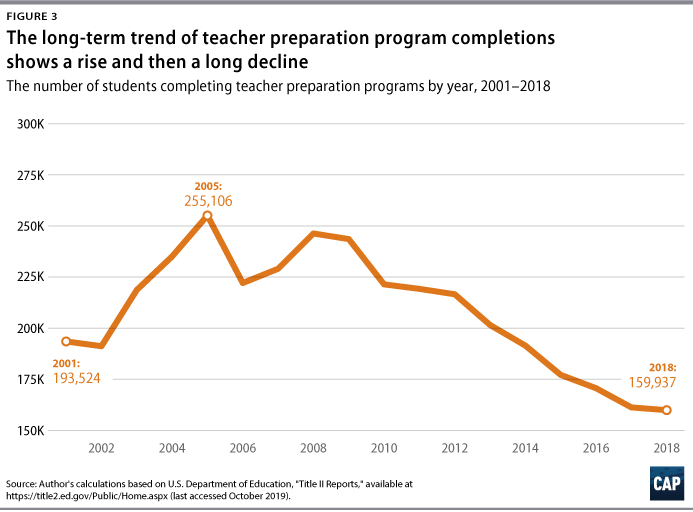

China, India, Germany, Canada, and the U.K. have all made investments to dramatically reshape the student experience for the world of AI and train teachers to educate a modern, digitally-prepared workforce. While the U.S. made early research & development investments in computer science and data science education through the National Science Foundation, we have no teacher workforce ready to implement these innovations in curriculum or educational technology. The number of individuals completing a teacher preparation program has fallen 25% over the past decade; long-term forecasts suggest at least 100,000 shortages annually, teachers themselves are discouraging others from joining their own profession (especially in STEM), and preparing to teach digital skills such as computer science was the least popular option for prospective educators to pursue. In 2022, even Harvard discontinued its Undergraduate Teacher Education Program completely, citing low interest and enrollment numbers. There is still consistent evidence that young people or even current professionals remain interested in teaching as a possible career, but only if we create the conditions to translate that interest into action. U.S. policymakers have a narrow window to leverage the strong interest in AI to energize the education workforce, and ensure our future graduates are globally competitive for the digital frontier.

Plan of Action

America’s teaching profession needs a coordinated national strategy to reverse decades of decline and concurrently reinvigorate the sector for a new (and digital) industrial revolution now moving at an exponential pace. Key levers for this work include expanding the number of leadership opportunities for educators; identifying and scaling successful evidence-based models such as UTeach, residency-based programs, or National Writing Project’s peer-to-peer training sites; scaling registered apprenticeship programs or Grow Your Own programs along with the nation’s largest teacher colleges; and leveraging the platform of the President to boost recognition and prestige of the teaching profession.

The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) should coordinate a set of Executive Actions within the first 100 days of the next administration, including:

Recommendation 1. Launch a Grand Challenge for AI-Era Teacher Preparation

Create a national challenge via www.Challenge.Gov to identify the most innovative teacher recruitment, preparation, and training programs to prepare and retain educators for teaching in the era of AI. Challenge requirements should be minimal and flexible to encourage innovation, but could include the creation of teacher leadership opportunities, peer-network sites for professionals, and digital classroom resource exchanges. A challenge prompt could replicate the model of 100Kin10 or even leverage the existing network.

Recommendation 2. Update Areas of National Need

To enable existing scholarship programs to support AI readiness, the U.S. Department of Education should add “Artificial Intelligence,” “Data Science,” and “Machine Learning” to GAANN Areas of National Need under the Computer Science and Mathematics categories to expand eligibility for Masters-level scholarships for teachers to pursue additional study in these critical areas. The number of higher education programs in Data Science education has significantly increased in the past five years, with a small but increasing number of emerging Artificial Intelligence programs.

Recommendation 3. Expand and Simplify Key Programs for Technology-Focused Training

The President should direct the U.S. Secretary of Education, the National Science Foundation Director, and the Department of Defense Education Activity Director to add “Artificial Intelligence, Data Science, Computer Science” as competitive priorities where appropriate for existing grant or support programs that directly influence the national direction of teacher training and preparation, including the Teacher Quality Partnerships (ED) program, SEED (ED), the Hawkins Program (ED), the STEM Corps (NSF), the Robert Noyce Scholarship Program (NSF), and the DoDEA Professional Learning Division, and the Apprenticeship Building America grants from the U.S. Department of Labor. These terms could be added under prior “STEM” competitive priorities, such as the STEM Education Acts of 2014 and 2015 for “Computer Science,”and framed under “Digital Frontier Technologies.”

Additionally, the U.S. Department of Education should increase funding allocations for ESSA Evidence Tier-1 (“Demonstrates Rationale”), to expand the flexibility of existing grant programs to align with emerging technology proposals. As AI systems quickly update, few applicants have the opportunity to conduct rigorous evaluation studies or randomized control trials (RCTs) within the timespan of an ED grant program application window.

Additionally, the National Science Foundation should relaunch the 2014 Application Burden Taskforce to identify the greatest barriers in NSF application processes, update digital review infrastructure, review or modernize application criteria to recognize present-day technology realities, and set a 2-year deadline for recommendations to be implemented agency-wide. This ensures earlier-stage projects and non-traditional applicants (e.g. nonprofits, local education agencies, individual schools) can realistically pursue NSF funding. Recommendations may include a “tiered” approach for requirements based on grant size or applying institution.

Recommendation 4. Convene 100 Teacher Prep Programs for Action

The White House Office of Science & Technology Policy (OSTP) should host a national convening of nationally representative colleges of education and teacher preparation programs to 1) catalyze modernization efforts of program experiences and training content, and 2) develop recruitment strategies to revitalize interest in the teaching profession. A White House summit would help call attention to falling enrollment in teacher preparation programs; highlight innovative training models to recruit and retrain additional graduates; and create a deadline for states, districts, and private philanthropy to invest in teacher preparation programs. By leveraging the convening power of the White House, the Administration could make a profound impact on the teacher preparation ecosystem.

The administration should also consider announcing additional incentives or planning grants for regional or state-level teams in 1) catalyzing K-12 educator Registered Apprenticeship Program (RAPs) applications to the Department of Labor and 2) enabling teacher preparation program modernization for incorporating introductory computer science, data science, artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, and other “digital frontier skills,” via the grant programs in Recommendation 3 or via expanded eligibility for the Higher Education Act.

Recommendation 5. Launch a Digital “White House Data Science Fair”

Despite a bipartisan commitment to continue the annual White House Science Fair, the tradition ended in 2017. OSTP and the Committee on Science, Technology, and Math Education (Co-STEM) should resume the White House Science Fair and add a national “White House Data Science Fair,” a digital rendition of the Fair for the AI-era. K-12 and undergraduate student teams would have the opportunity to submit creative or customized applications of AI tools, machine-learning projects (similar to Kaggle competitions), applications of robotics, and data analysis projects centered on their own communities or global problems (climate change, global poverty, housing, etc.), under the mentorship of K-12 teachers. Similar to the original White House Science Fair, this recognition could draw from existing student competitions that have arisen over the past few years, including in Cleveland, Seattle, and nationally via AP Courses and out-of-school contexts. Partner Federal agencies should be encouraged to contribute their own educational resources and datasets through FC-STEM coordination, enabling students to work on a variety of topics across domains or interests (e.g. NASA, the U.S. Census, Bureau of Labor Statistics, etc.).

Recommendation 6. Announce a National Teacher Talent Surge at the State of Union

The President should launch a national teacher talent surge under the banner of “America’s Teachers Innovate,” a multi-agency communications campaign to reinvigorate the teaching profession and increase the number of teachers completing undergraduate or graduate degrees each year by 100,000. This announcement would follow the First 100 Days in office, allowing Recommendations 1-5 to be implemented and/or planned. The “America’s Teachers Innovate” campaign would include:

A national commitments campaign for investing in the future of American teaching, facilitated by the White House, involving State Education Agencies (SEAs) and Governors, the 100 largest school districts, industry, and philanthropy. Many U.S. education organizations are ready to take action. Commitments could include targeted scholarships to incentivize students to enter the profession, new grant programs for summer professional learning, and restructuring teacher payroll to become salaried annual jobs instead of nine-month compensation (see Discover Bank: “Surviving the Summer Paycheck Gap”).

Expansion of the Presidential Awards for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching (PAMEST) program to include Data Science, Cybersecurity, AI, and other emerging technology areas, or a renaming of the program for wider eligibility across today’s STEM umbrella. Additionally, the PAMEST Award program should resume in-person award ceremonies beyond existing press releases, which were discontinued during COVID disruptions and have not since been offered. Several national STEM organizations and teacher associations have requested these events to return.

Student loan relief through the Teacher Loan Forgiveness (TLF) program for teachers who commit to five or more years in the classroom. New research suggests the lifetime return of college for education majors is near zero, only above a degree in Fine Arts. The administration should add “computer science, data science, and artificial intelligence” to the subject list of “Highly Qualified Teacher” who receive $17,500 of loan forgiveness via executive order.

An annual recruitment drive at college campus job fairs, facilitated directly under the banner of the White House Office of Science & Technology Policy (OSTP), to help grow awareness on the aforementioned programs directly with undergraduate students at formative career choice-points.

Recommendation 7. Direct IES and BLS to Support Teacher Shortage Forecasting Infrastructure

The IES Commissioner and BLS Commissioner should 1) establish a special joint task-force to better link existing Federal data across agencies and enable cross-state collaboration on the teacher workforce, 2) support state capacity-building for interoperable teacher workforce data systems through competitive grant priorities in the State Longitudinal Data Systems (SLDS) at IES and the Apprenticeship Building America (ABA) Program (Category 1 grants), and 3) recommend a review criteria question for education workforce data & forecasting in future EDA Tech Hub phases. The vast majority of states don’t currently have adequate data systems in place to track total demand (teacher vacancies), likely supply (teachers completing preparation programs), and the status of retention/mobility (teachers leaving the profession or relocating) based on near- or real-time information. Creating estimates for this very brief was challenging and subject to uncertainty. Without this visibility into the nuances of teacher supply, demand, and retention, school systems cannot accurately forecast and strategically fill classrooms.

Image: AmericanProgress.org

Recommendation 8. Direct the NSF to Expand Focus on Translating Evidence on AI Teaching to Schools and Districts.

The NSF Discovery Research PreK-12 Program Resource Center on Transformative Education Research and Translation (DRK-12 RC) program is intended to select intellectual partners as NSF seeks to enhance the overall influence and reach of the DRK-12 Program’s research and development investments. The DRK-12 RC program could be utilized to work with multi-sector constituencies to accelerate the identification and scaling of evidence-based practices for AI, data science, computer science, and other emerging tech fields. Currently, the program is anticipated to make only one single DRK-RC award; the program should be scaled to establish at least three centers: one for AI, integrated data science, and computer science, respectively, to ensure digitally-powered STEM education for all students.

Conclusion

China was #1 in the most recent Global Teacher Status Index, which measures the prestige, respect, and attractiveness of the teaching profession in a given country; meanwhile, the United States ranked just below Panama. The speed of AI means educational investments made by other countries have an exponential impact, and any misstep can place the United States far behind – if we aren’t already. Emerging digital threats from other major powers, increasing fluidity of talent and labor, and a remote-work economy makes our education system the primary lever to keep America competitive in a fast-changing global environment. The timing is ripe for a new Nation at Risk-level effort, if not an action on the scale of the original National Defense Education Act in 1958 or following the more recent America COMPETES Act. The next administration should take decisive action to rebuild our country’s teacher workforce and prepare our students for a future that may look very different from our current one.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

This memo was developed in partnership with the Alliance for Learning Innovation, a coalition dedicated to advocating for building a better research and development infrastructure in education for the benefit of all students. Read more education R&D memos developed in partnership with ALI here.