Ending Nuclear Counterforce

Last Wednesday, 8 April, the Federation of American Scientists and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) jointly released FAS Occasional Paper Number 7, From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence — A New Nuclear Policy on the Path Toward Eliminating Nuclear Weapons. As part of the release, my coauthors, Stan Norris of NRDC and Hans Kristensen of FAS, and I held a panel discussion at the Carnegie Endowment, where each of us presented results of our research that is covered in the paper. This essay summarizes my comments on that panel.

There are three things we describe in this paper. First, we are proposing a new set of military missions for nuclear weapons—actually the “set” is just one mission, second, we are describing what that mission would look like, and, third, we are describing one way to actually get that single mission properly implemented.

(more…)

Study Calls for New U.S. Nuclear Weapons Targeting Policy

|

| Click on image for PDF-version of full report. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Federation of American Scientists and Natural Resources Defense Council today published a study that calls for fundamental changes in the way the United States military plans for using nuclear weapons.

The study From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence: A New Nuclear Policy on the Path Toward Eliminating Nuclear Weapons recommends abandoning the decades-old “counterforce” doctrine and replacing it with a new and much less ambitious targeting policy the authors call Minimal Deterrence. [Update: see Washington Post – Report Urges Updating of Nuclear Weapons Policy]

Global Security Newswire reported last week that Department of Defense officials have concluded that significant reductions to the nuclear arsenal cannot be made unless President Barack Obama scales back the nation’s strategic war plan. The FAS/NRDC report presents a plan for how to do that.

The last time outdated nuclear guidance stood in the way of nuclear cuts was in 1997, when then President Clinton had to change President Reagan’s 17-year old guidance to enable U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) to go to the START-III force level that the Bush administration subsequently adopted as the Moscow Treaty force level. The series of STRATCOM force structure studies examining lower force levels is described in The Matrix of Deterrence.

Resources: Full Report | US Nuclear Forces 2009 | United States Reaches Moscow Treaty Warhead Limit Early | Press Conference Video

Russian Tactical Nuclear Weapons

|

| New low-yield nuclear warheads for cruise missiles on Russia’s submarines?. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Two recent news reports have drawn the attention to Russia’s tactical nuclear weapons. Earlier this week, RIA Novosti quoted Vice Admiral Oleg Burtsev, deputy head of the Russian Navy General Staff, saying that the role of tactical nuclear weapons on submarines “will play a key role in the future,” that their range and precision are gradually increasing, and that Russia “can install low-yield warheads on existing cruise missiles” with high-yield warheads.

This morning an editorial in the New York Times advocated withdrawing the “200 to 300” U.S. tactical nuclear bombs deployed in Europe “to make it much easier to challenge Russia to reduce its stockpile of at least 3,000 short-range weapons.”

Both reports compel – each in their own way – the Obama administration to address the issue of tactical nuclear weapons.

The Russian Inventory

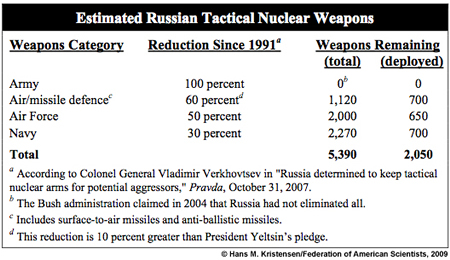

Like the United States, Russia doesn’t say much about the status of its tactical nuclear weapons. The little we have to go by is based on what the Soviet Union used to have and how much Russian officials have said they have cut since then.

Unofficial estimates set the Soviet inventory of tactical nuclear weapons at roughly 15,000 in mid-1991. In response to unilateral cuts announced by the United States in late 1991 and early 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin pledged in 1992 that production of warheads for ground-launched tactical missiles, artillery shells, and mines had stopped and that all such warheads would be eliminated. He also pledged that Russia would dispose of half of all airborne and surface-to-air warheads, as well as one-third of all naval warheads.

In 2004, the Russian Foreign Ministry stated that “more than 50 percent” of these warhead types have been “liquidated.” And in September 2007, Defense Ministry official Colonel-General Vladimir Verkhovtsev gave a status report of these reductions that appeared to go beyond President Yeltsin’s pledge.

Based on this, Robert Norris and I make the following cautious estimate (to be published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in late April) of the current Russian inventory of tactical nuclear weapons:

|

| Estimate from forthcoming Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. |

.

Based on the number of available nuclear-capable delivery platforms, we estimate that nearly two-thirds of these warheads are in reserve or awaiting dismantlement. The remaining approximately 2,080 warheads are operational for delivery by anti-ballistic missiles, air-defence missiles, tactical aircraft, and naval cruise missiles, depth bombs, and torpedoes. The Navy’s tactical nuclear weapons are not deployed at sea under normal circumstances but stored on land.

The Other Nuclear Powers

The United States retains a small inventory of perhaps 500 active tactical nuclear weapons. This includes an estimated 400 bombs (including 200 in Europe) and 100 Tomahawk cruise missiles (all on land). Others, perhaps 700, are in inactive storage.

France also has 60 tactical-range cruise missiles, including some on its aircraft carrier, although it calls them strategic weapons.

The United Kingdom has completely eliminated its tactical nuclear weapons, although it said until a couple of years ago that some of its strategic Trident missiles had a “sub-strategic” mission.

Information about possible Chinese tactical nuclear weapons is vague and contradictory, but might include some gravity bombs.

India, Pakistan, and Israel have some nuclear weapons that could be considered tactical (gravity bombs for fighter-bombers and, in the case of India and Pakistan, short-range ballistic missiles), but all are normally considered strategic.

| Russian Nuclear-Capable Cruise Missile Launch |

|

| A nuclear-capable SS-N-19 Shipwreck cruise missile is launched from a Kirov-class nuclear-powered guided missile cruiser. The ship is equipped with 20 launchers for the SS-N-19 missile, which can carry a 500-kiloton warhead. Other tactical nuclear weapon systems include the SS-N-16 anti-submarine rocket, and the SA-N-6 anti-air missile. |

.

Implications and Issues

Whether Vice Admiral Burtsev’s statement is more than boasting remains to be seen, but it is a timely reminder to the Obama administration of the need to develop a plan for how to tackle the tactical nuclear weapons.

Russia’s nuclear posture is now approaching a situation where there are more tactical nuclear weapons in the inventory than strategic weapons. And NATO’s remnant of the Cold War tactical nuclear posture in Europe seems stuck in the mud of nuclear dogma and bureaucratic inaction.

None of these tactical nuclear weapons are limited or monitored by any arms control agreements, and – for all the worries about terrorists stealing nuclear weapons – are the most easy to run away with.

In April, NATO is widely expected to kick off a (long-overdue) review of its Strategic Concept from 1999. It would be a mistake to leave the initiative on what to do with the tactical nuclear weapons to the NATO bureaucrats. The vision must come from the top and President Obama needs to articulate what it is soon.

U.S. Strategic Submarine Patrols Continue at Near Cold War Tempo

|

| U.S. ballistic missile submarines conducted 31 nuclear deterrent patrols in 2008 at an operational tempo comparable to that of the Cold War. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen [updated]

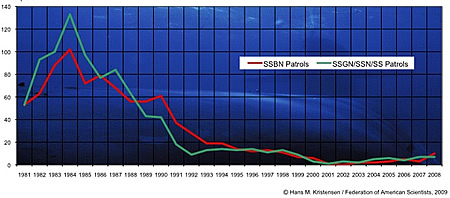

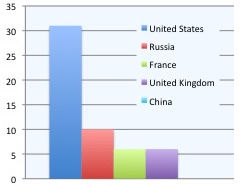

The U.S. fleet of 14 nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines conducted 31 nuclear deterrent patrols in 2008 at an operational tempo comparable to during the Cold War.

The new patrol information, which was obtained from the U.S. Navy under the Freedom of Information Act, coincides with the completion on February 11, 2009, of the 1,000th deterrent patrol by an Ohio-class submarine since 1982.

The information shows that the United States conducts more nuclear deterrent patrols each year than Russia, France, United Kingdom and China combined.

Patrols by the Number

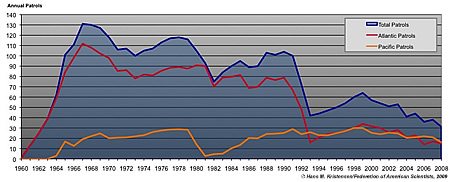

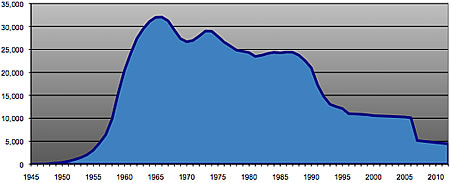

The 31 patrols conducted in 2008 top a 48-year history of continuous deterrent patrols. Since the USS George Washington (SSBN-598) departed Charleston, S.C., on the first nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) patrol on November 15, 1960, 59 SSBNs have conducted 3,814 patrols through 2008 (see Figure 1).

.

The annual number of patrols has fluctuated considerably over the years, peaking at 131 patrols in 1967. Declines occurred mainly due to retirement of SSBNs rather than changes in the mission. The retirement of the early classes of SSBNs in 1979-1981 almost eliminated patrols in the Pacific, but the new Ohio-class gradually rebuilt the posture. The stand-down of Poseidon SSBNs in October 1991 and the retirement of all non-Ohio-class SSBNs by 1993 reduced Atlantic patrols by nearly 60 percent. The patrols increased again in the second half of the 1990s and more Ohio-class SSBNs were added to the fleet, but started dropping from 2000 as four Ohio-class SSBNs were withdrawn from nuclear missions and four others underwent lengthy backfits from the Trident I C4 to the Trident II D5 Trident missile.

|

Figure 2: |

|

|

The United States conducts more SSBN patrols than all other nuclear powers combined. China’s SSBNs have yet to conduct a deterrent patrol. |

During the Cold War standoff with the Soviet Union, the vast majority of patrols were done in the Atlantic Ocean. Since the early 1990s, patrols in the Atlantic have plummeted and the SSBN force been concentrated on the west coast. The majority of U.S. SSBN patrols today occur in the Pacific.

The current number of patrols is significantly greater than the patrol levels of other countries with sea-based nuclear weapon systems. In fact, the U.S. navy conducted three times the number of SSBN patrols that the Russian navy did in 2008, and more patrols than Russia, France, Britain and China combined (see figure 2).

High Operational Tempo

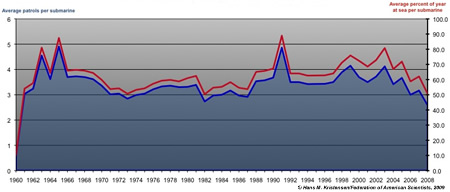

Although the total annual number of SSBN patrols has decreased significantly since the end of the Cold War, the operational tempo of each submarine has not. Each Ohio-class SSBNs today conducts about the same number of patrols per year as during the Cold War, but the duration of each patrol has increased, with each submarine spending approximately 50-60 percent of its time on patrol (see Figure 3).

.

The high operational tempo is made possibly by each SSBN having two crews, Blue and Gold. Each time a submarine returns from a patrol, the other crew takes over, spends a few weeks repairing and replenishing the boat, and takes the SSBN out for its next patrol.

The data also reveals a couple of interesting spikes of increased patrols in 1963/1965 and 1991. The reasons for this increased activity is not known but the periods coincide with the Cuban missile crisis and the failed coup attempt in the final days of the Soviet Union in 1991.

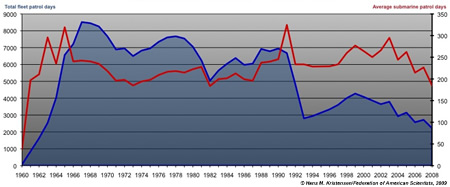

Another way to examine the data is to see how may patrol days each submarine and the fleet accumulate each year. During the Cold War the larger submarine fleet averaged approximately 6,000 patrol days each year, with a peak of 8,515 patrol days in 1967. That performance declined to an average of 3,400 days in the post-Cold War era as the size of the SSBN fleet was reduced. With the removal of four SSBNs from nuclear operations and four others undergoing lengthy missile backfits, the fleet’s total patrol days has now dropped to a little over 2,200 (see figure 4).

.

Yet total patrol day numbers can be deceiving because they can obscure how each submarine is doing. Because the Ohio-class SSBN design was optimized for lengthy deterrent patrols, the average number of days each submarine spends on patrol has been higher in the post-Cold War period than during the Cold War itself. Patrols can be shortened by technical problems, but many Ohio-class submarines today stay on patrol for more than 80 days. Last year, the USS Maine (SSBN-741) conducted a 98-day patrol in the Pacific.

What is a Deterrent Patrol?

An SSBN deterrent patrol is an extended operational deployment during part of which the submarine covers its assigned target package in support of the strategic war plan. Each Ohio-class patrol typically lasts 60-90 days, but one submarine in late 2008 conducted an extended patrol of 98 day and patrols have occasionally exceeded 100 days. Occasionally a patrol is cut short by technical problems, in which case another SSBN can be deployed on short notice. As a result, patrols today in average last about 72 days.

Being on patrol does not mean the submarine is continuously submerged on-station and holding targets at risk. In fact, when the submarine is not on Hard Alert holding targets at risk in Russia, China, or regional states, much of the patrol time is spent on cruising between homeport, patrol areas, exercising with other naval forces, undergoing inspections and certifications, performing Weapon System Readiness Tests (WSRTs), conducting retargeting exercises, and Command and Control exercises.

Another activity involves so-called SCOOP exercises (SSBN Continuity of Operations Program) where the SSBN will practice replenishment or refit in forward ports in case the homeport is annihilated in wartime. In the Pacific, the SCOOP ports include Pearl Harbor, Hawaii (see Figure 5), Guam, Seaward, Alaska, Astoria, Oregon, and San Diego, California. In the Atlantic they include Port Canaveral and Mayport, Florida, Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico, and Halifax, Canada. The SSBN may even return to its homeport and redeploy a day or two later on the same patrol.

|

Figure 5: |

|

| USS Henry M. Jackson (SSBN-730) loading fresh fruit in Pearl Harbor during a SCOOP visit to Hawaii in March 2008 on its first patrol after a four-year overhaul where it was refueled and modernized to carry the Trident II D5 ballistic missile. |

.

Although patrols normally end at the base where they started, this is not always the case. An SSBN that departs Naval Submarine Base Bangor, Washington, might go on-station for several weeks in alert operational areas, conduct various training and exercises, and then arrive at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. After a brief port visit and replenishment the submarine typically resumes its patrol and eventually returns to Bangor. But sometimes the patrol will end in Hawaii, a new crew be flown in to replace the old, and the submarine undergo refit at the forward location as part of a SCOOP exercise. The SSBN then departs Hawaii on a new patrol, goes on-station in alert operational areas, conducts more exercises and inspections, and eventually returns to Bangor where the new patrol ends.

This type of broken up patrol where the submarine is allowed to do more than on-station operations is sometimes described as “modified alert” and said to be different from the Cold War. But SSBNs have never been on-station all the time, with most deployed submarines being in transit between on-station alert areas and other non-alert operations. In fact, “modified alert” patrols date back to the early 1970s.

Of the 14 SSBNs currently in the fleet, two are normally in overhaul at any given time. Of the remaining operational 12 submarines, 8-9 are deployed on patrol at any given time. Four of these (two in each ocean) are on “Hard Alert” while the 4-5 non-alert SSBNs can be brought to alert level within a relatively short time if necessary. One to three SSBNs are in refit at the home base in preparation for their next patrol.

The SSBNs on Hard Alert continuously hold at risk facilities in Russia, China and regional states with an estimated 384 nuclear warheads on 96 Trident II D5 missiles that can be launched within “a few minutes” after receiving the launch order. The targets in the “target packages” are selected based on the taskings of the strategic war plan, known today as Operations Plan (OPLAN) 8010.

What is the Mission?

But why, nearly two decades after the Cold War ended, are 28 crews ordered to sail 14 SSBNs with more than 1,000 nuclear warheads on 30-plus patrols each year at an operational tempo comparable to that of the Cold War?

The official line is, as stated last month by Secretary of the Navy Donald Winter during the celebration of the 1,000th Ohio-class deterrent patrol, that “the ability of our Trident fleet to [be ready to launch its missiles] 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year, has promoted the interests of peace and freedom around the world….Since the beginning of the nuclear age, the world has seen a drastic reduction in wartime deaths.”

|

Figure 6: |

|

|

STRATCOM commander General Kevin Chilton (left) and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Gary Roughead. General Chilton says SSBNs deter not only nuclear conflict but “conflict in general” and are “as equally important today, as they ever were during the height of the Cold War.” |

The warfighters add more nuances, including Commander Jeff Grimes of the Trident submarine USS Maryland (SSBN-738) who at the start of a recent deterrent patrol explained it to Navy Times: “There are nuclear weapons in the world today. Many nations have them. Proliferation is possible in the growing technologies societies have. The power of the deterrent is the knowledge that the capability exists in the hands of controlled people. So on a global scale, deterrence is showing how it’s working every day. We haven’t had a global, world war, in a long time,” he said. “Intelligence is different, the threats are different, so we do adjust the planning and contingencies for strategic operations continually to face the threats that may or may not be seen….We’re there on the front line, ready to go,” Grimes declared.

STRATCOM commander General Kevin Chilton, who in a war would advise the president on which nuclear strike options to use, said recently that although some people thought the Trident mission would end with the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, the SSBNs “are as equally important today, as they ever were during the height of the Cold War….The application of deterrence can actually be more complicated in the 21st century, but some fundamentals don’t change,” he said and added: “And it is not just to deter nuclear conflict. These forces have served to deter conflict in general, writ large, since they’ve been fielded.”

These are strong and diverse claims that are also made in some of the command histories that each SSBN produces. Some of them state that the mission is to “maintain world peace,” which has certainly not been the case in the post-Cold War era. Others describe the mission as “providing strategic deterrence to prevent nuclear war” (my emphasis), which sounds more credible. But even in that case, can we really tell whether it is the SSBNs that prevent nuclear war and not the ICBMs or bombers?

The enormous differences between maintaining world peace, preventing wars, and preventing nuclear war demand that officials articulate the SSBN mission much more clearly. To that end, it would be good to hear why it takes 12 operational SSBNs with more than 1,100 nuclear warheads on 30-plus patrols per year to deter nuclear attack against the United States, but only three operational SSBNs with less than 160 warheads on six patrols per year to safeguard the United Kingdom.

|

Figure 7: |

|

| USS Maryland (SSBN-738) departs Kings Bay on February 15, 2009, for its 53rd deterrent patrol in the Atlantic Ocean to prevent nuclear war, prevent world war, deter conflict, maintain world peace, promote the interests of peace of freedom, deter proliferators, in a mission that remains“equally important…as during the height of the Cold War,” depending on who is describing it. |

.

Last year Russia’s SSBNs returned to sea at a level not seen in a decade and it plans to build eight new Borey-class SSBNs with new multi-warhead missiles. France is completing its fourth Triomphant-class SSBNs also with a new multi-warhead missile, and Britain has announced plans to build four new SSBNs. China is building 3-5 new Jin-class SSBNs with 8000-kilometer missiles, and India is said to be working on an SSBN as well. The U.S. Navy has also begun design work on its next ballistic missile submarine to replace the Ohio-class.

In short, the nuclear powers seem to be recommitting themselves to an era of deploying large numbers of nuclear weapons in the oceans. Most people tend to view sea-based nuclear weapons as the most legitimate leg of the Triad. Yet of all strategic nuclear weapons, sea-based ballistic missiles are the most difficult to track, the most problematic to communicate with in a crisis, the hardest to verify in an arms control agreement, and the only ones that can sneak up on an adversary in a surprise attack.

If the Obama administration wants to decisively move the world toward “dramatic reductions” and ultimately the elimination of nuclear weapons, then it must seek answers to these issues. In the short term, it needs to ask whether the Cold War operational tempo of U.S. SSBNs is counterproductive by sending a signal to other nuclear weapon states that triggers modernization of their forces and makes reductions harder to achieve than otherwise. In other words, what is the net impact of the SSBN patrols on U.S. national security objectives in an era of pursuing nuclear disarmament?

Addition Resources: Russian Sub Patrols | Chinese Sub Patrols

_____________________________________________________________

US-Chinese Anti-Submarine Cat and Mouse Game in South China Sea

|

| The Chinese military harassment of a U.S. submarine surveillance vessel Sunday occurred only 75 miles from China’s growing naval base near Yulin on Hainan Island. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen [updated 1:50 P.M., 3/10/09]

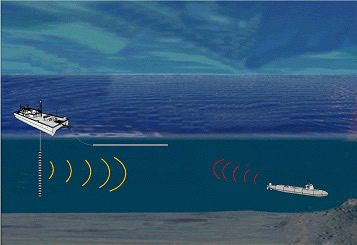

The incident that unfolded in the South China Sea Sunday, where the U.S. Navy says five Chinese ships harassed the U.S. submarine surveillance vessel USNS Impeccable, appears to be part of a wider and dangerous cat and mouse game between U.S. and Chinese submarines and their hunters.

News media reports cite Pentagon reports of half a dozen other incidents just within the past week in which U.S. surveillance vessels were “subjected to aggressive behavior, including dozens of fly-bys by Chinese Y-12 maritime surveillance aircraft.”

The latest incident allegedly occurred in international waters only 75 miles south of a budding naval base near Yulin on Hainan Island from where China has started operating new nuclear attack and ballistic missile submarines. The U.S. Navy on its part is busy collecting data on the submarines and seafloor to improve its ability to detect the submarines in peacetime and more efficiently hunt them in case of war.

|

USNS Impeccable (T-AGOS-23) |

|

|

The USNS Impeccable was designed specifically as a platform for the SURTASS towed array and its Low Frequency Array upgrade. |

An Impeccable “Civilian Crew”

The U.S. Navy’s description of the incident states that “a civilian crew mans the ship, which operates under the auspices of the Military Sealift Command.” Yet as one of five ocean surveillance ships, the USNS Impeccable (T-AGOS 23) has the important military mission of using its array of both passive and active low frequency sonar arrays to detect and track submarines. The USNS Impeccable works directly with the Navy’s fleets, and in 2007 operated with the three-carrier strike battle group in Valiant Shield 07 exercise in the Western Pacific.

USNS Impeccable is equipped with the Surveillance Towed Array Sensor System (SURTASS), a passive linear underwater surveillance array attached to a tow cable. SURTASS was developed as a floating submarine detection system for deep waters, and the Navy wants to add an active Low Frequency Array (LFA) to improve long-range detection of submarines in shallow waters.

|

SURTASS LFA Deployment |

|

| The SURTASS LFA passive-active surveillance system is designed to detect submarines and surface ships at long range in deep and shallow waters. |

.

Indeed, according to the U.S. Navy, the USNS Impeccable is “designed specifically as a platform for the SURTASS towed array and its LFA adjunct.”

New Chinese Nuclear Submarines at Yulin Naval Base

Among Chinese submarines the USNS Impeccable was monitoring is probably the Shang-class (Type-093) nuclear-powered attack submarine, a new class China is building to replace the old Han-class, and which has recently been seen at the Yulin base.

A commercial satellite image taken September 15, 2008, shows two Shang-class submarines present at the base, the first time – to my knowledge – that two Shang-class SSNs have been seen at the base at the same time.

.

An earlier image from February 2008 showed a Jin-class (Type-094) ballistic missile submarine at the Hainan base for the first time. The Jin-class is not visible on the later image. China has been reducing its submarine fleet by replacing old boats with fewer modern ones. The submarines normally stay close to shore, but in 2008 sailed on 12 longer patrols – twice as many as in 2007.

Time For an Incident Agreement

The incident begs the question who or at what level in the Chinese government the harassment in international waters was ordered. The incident will make life harder for those in the Obama administration who want to ease the military pressure on U.S.-Chinese relations, and easier for hardliners to argue their case.

For both countries the Sunday incident and the many other incidents that have occurred recently are reminders that the time is long overdue for an agreement to regulate military operations. Following a break in response to U.S. military sales to Taiwan, U.S.-Chinese mid-level military-to-military talks were scheduled to resume last month, and the Commander of U.S. Pacific Command, Admiral Timothy Keating, said “nascent initiatives” were underway to draw up some “rules of the road” to address some of these issues.

Absent a substantial agreement, building on the 1998 US-Chinese Military Maritime Safety Agreement (which already includes discussions on “interpretation of the Rules of the Nautical Road and avoidance of accidents-at-sea”) and the 1972 US-Russian Incidents at Sea Agreement, incidents like the USNS Impeccable incident will continue as a serious irritant and source of mistrust between China and the United States, a situation neither country nor other nations in the region can afford.

Additional resources: US-Chinese Military Maritime Safety Agreement (1998) | US-Russian Incidents at Sea Agreement (1972) | Secrecy News Blog: U.S., China, and Incidents at Sea

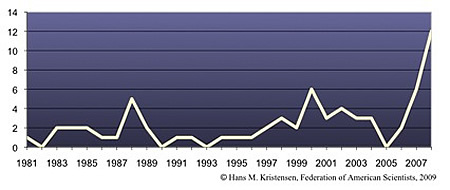

Russian Strategic Submarine Patrols Rebound

|

| Russian SSBN patrols tripled from 2007 to 2008. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

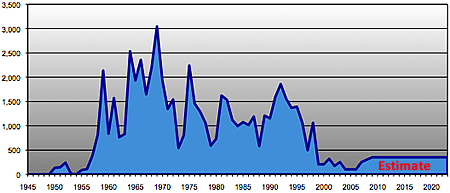

Russia sent more nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines on patrol in 2008 than in any other year since 1998, according to information obtained by Federation of American Scientists from U.S. naval intelligence.

The information shows that Russian missile submarine conducted ten patrols in 2008, compared with three in 2007 and five in 2006. In 2002, no patrols were conducted at all.

Return of Continuous Russian SSBN Patrols?

For the past ten years, Russian remaining 11 SSBNs have not maintained continuous patrols, but instead carried out occasional patrols for training purposes. Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov said in on September 11, 2006, that five SSBNs were on patrol at that time. But since that number matched the total number of patrols conducted that year, it revealed a cluster of patrols rather than a continuous at-sea presence.

The United States, France and Britain, in contrast, continuously have at least one SSBN on patrol. In the case of the United States, two-thirds of its 14 SSBNs are at sea at any given time, of which four are on alert.

.

The ten Russian patrols in 2008 raise the question whether Russia has now resumed continuous SSBN patrols. Neither the duration nor the dates of Russian SSBN patrols are known, but if they east last more than 36 days and do not overlap, then Russia could have a continuous at-sea deterrent. If the patrols cluster like in 2006, then the posture might still be sporadic.

The Voyage of Ryazan

Although not specified in the information obtained from U.S. naval intelligence, one of the Russian patrols probably was the 30-days under-ice voyage of the Delta III-class submarine Ryazan from the Northern Fleet on the Kola Peninsula in the Barents Sea to the Pacific Fleet on the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Pacific.

|

Figure 2: |

|

| One of the 10 SSBN patrols probably involved the transfer of a Delta III SSBN from the Northern Fleet to the Pacific Fleet. |

.

The voyage occurred shortly after Ryazan completed a successful test launch of a ballistic missile – probably an SS-N-18 – from the Barents Sea on August 1, 2008. The missile type was not announced, which is unusual, but its payload flew across Northern Russia and impacted in the Kura test range on the Kamchatka Peninsula.

At end the of August, Ryazan departed the Northern Fleet and sailed submerged along Russia’s ice covered northern coast through the Bering Strait before it headed south to the ballistic missile submarine base in Vladivostok, where it arrived on September 30.

Arms Control Implications

It would be ironic – now that the Obama administration has proposed reductions in strategic nuclear forces and Kremlin seems to respond favorably – if Russian SSBNs returned to the Cold War practice of continuous deterrent patrols.

SSBNs continuously roaming the oceans are one of the last symbols of the Cold War when long-range nuclear missiles were hidden in the deep to survive a massive first strike. United States SSBNs continue a patrol rate comparable to that of the 1980s, France and Britain try to keep one or two at sea at any time – two apparently collided last month, and China and India are trying to build SSBNs fleets too.

Many still see SSBNs as purely retaliatory weapons passively hiding in the oceans. But as U.S. and Russian nuclear forces are reduced further and China and India join the SSBS club, forward deployed submerged nuclear weapons could become some of the most problematic challenges for nuclear arms control.

United States Reaches Moscow Treaty Warhead Limit Early

|

| B83 thermonuclear bombs are offloaded from a C-17 aircraft for storage in preparation for meeting the limit of the Moscow Treaty three and a half years early. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The United States has reduced its deployed strategic warheads to the maximum number allowed under 2002 Moscow Treaty, three and a half years early.

As of today, a total of 2,200 strategic warheads are deployed on ballistic missiles and at long-range bomber bases. The reduction was initially planned to be met in 2012, then 2010, but was achieved a few days ago.

The information is described in the forthcoming “Nuclear Notebook: U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2009,” which I co-author with Robert Norris from Natural Resources Defense Council. The article will be published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists later this month.

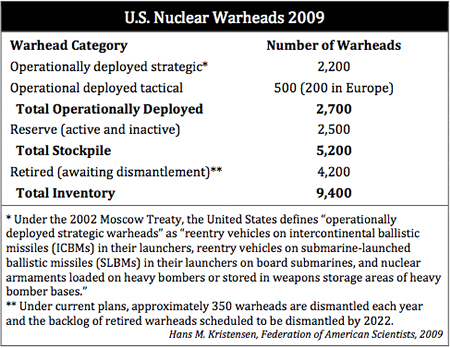

Warhead Number Confusion

We obtained the information from the U.S. government. While the number of operationally deployed strategic warheads is not classified the total number of weapons in the U.S. inventory is a closely held secret. The government also keeps secret how many warheads are held in reserve as well as the number of warheads dismantled each year.

As a result, there is considerable confusion in the public about the size and categories of U.S. nuclear weapons. One recent Associated Press report, for example, said the “American stockpile is believed to be about 2,300,” a number that is now being repeated by news media across the globe.

The stockpile number is not correct. Norris and I estimate that the U.S. “stockpile” currently includes approximately 5,200 warheads, of which only about half are deployed. This includes about 2,200 strategic and 500 tactical warheads (including 200 in Europe). Moreover, an additional roughly 4,200 intact warheads are no longer in the DOD Stockpile but awaiting dismantlement. All included, the United States is estimated to possess approximately 9,400 warheads in all categories (see table).

|

.T

The “operationally deployed strategic warheads” is a special counting rule the United States uses under the Moscow Treaty. It does not count hundreds of warheads in storage at the Navy’s two missile submarine bases and the Air Forces’ three ballistic missile bases. Russia, which does not use this counting rule and does not release its warhead count, is estimated to have approximately 2,700 operational strategic warheads.

Reductions But What Kind?

The “real” numbers are important at a time when the United States and Russia are discussing if and how to extend the 1991 START agreement, which expires later this year, and whether to reduce further the number of nuclear warheads.

The news media has recently reported that the Obama administration might seek to cut the “stockpile” by 80 percent, and quoted an anonymous official saying “nobody would be surprised if the number reduced to the 1,000 mark for the post-Start treaty.”

It matters a great deal whether the cut will be of the total stockpile or just the “operationally deployed strategic warheads.” An 80 percent cut in the 5,200-warhead stockpile corresponds to approximately 1,000 warheads. A reduction of the START number limit (6,000 warheads) by 80 percent would leave about 1,200 warheads. Cutting the SORT limit (2,200 warheads) to 1,000 would be a reduction of about 54 percent.

If the total stockpile were reduced to 1,000 warheads, only a portion of them would presumably be deployed. Using the current ratio (52 percent) that would mean only 520 of the 1,000 warheads would be deployed with the balance in reserve. The entire ICBM force today carries about 520 warheads, but it is doubtful that a Triad could be justified with so few operational warheads. There are some hard choices ahead about which leg to cut.

Chinese Submarine Patrols Doubled in 2008

|

| Chinese submarines conducted 12 patrols in 2008, the highest ever. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Chinese attack submarines sailed on more patrols in 2008 than ever before, according to information obtained by Federation of American Scientists from U.S. naval intelligence.

The information, which was declassified by U.S. naval intelligence in response to a Freedom of Information Act request from the Federation of American Scientists, shows that China’s fleet of more than 50 attack submarines conducted 12 patrols in 2008, twice the number of patrols conducted in 2007.

China’s strategic ballistic missile submarines have never conducted a deterrent patrol.

Highest Patrol Rate Ever

The 12 patrols conducted in 2008 constitute the highest patrol rater ever for the Chinese submarine fleet. They follow six patrols conducted in 2007, two in 2006, and zero in 2005. China has four times refrained from conducting submarine patrols since 1981, and the previous peaks were six patrols conducted in 2000 and 2007 (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1: |

|

| Chinese attack submarines conducted 12 patrols in 2008, double the number from 2007. Yet Chinese ballistic missile submarines have yet to conduct a deterrent patrol. |

.

While the increase is submarine patrols is important, it has to be seen in comparison with the size of the Chinese submarine fleet. With approximately 54 submarines, the patrol rate means that each submarine on average goes on patrol once every four and a half years. In reality, the patrols might have been carried out by only a small portion of the fleet, perhaps the most modern and capable types. A new class of nuclear-powered Shang-class (Type-093) attack submarines is replacing the aging Han-class (Type-091).

Few of the details for assessing the implications of the increased patrol rate are known, nor is it known precisely what constitutes a patrol in order for U.S. naval intelligence to count it. A request for the definition has been denied. It is assumed that a patrol in this case involves an extended voyage far enough from the submarine’s base to be different from a brief training exercise.

In comparison with other major navies, twelve patrols are not much. The patrol rate of the U.S. attack submarine fleet, which is focused on long-range patrols and probably operate regularly near the Chinese coast, is much higher with each submarine conducting at least one extended patrol per year. But the Chinese patrol rate is higher than that of the Russian navy, which in 2008 conducted only seven attack submarine patrols, the same as in 2007.

Still no SSBN Patrols

The declassified information also shows that China has yet to send one of its strategic submarines on patrol. The old Xia, China’s first SSBN, completed a multi-year overhaul in late-2007 but did not sail on patrol in 2008.

|

| Neither the Xia-class (Type-092) ballistic missile submarine (image) nor the new Jin-class (Type-094) have ever conducted a deterrent patrol. |

.

The first of China’s new Jin-class (Type-094) SSBN was spotted in February 2008 at the relatively new base on Hainan Island, where a new submarine demagnetization facility has been constructed. But the submarine did not conduct a patrol the remainder of the year. A JL-2 missile was test launched Bohai Bay in May 2008, but it is yet unclear from what platform.

Two or three more Jin-class subs are under construction at the Huludao (Bohai) Shipyard, and the Pentagon projects that up to five might be built. How these submarines will be operated as a “counter-attack” deterrent remains to be seen, but they will be starting from scratch.

The Minot Investigations: From Fixing Problems to Nuclear Advocacy

|

| The second report from the Schlesinger Task Force goes beyond fixing nuclear problems to promoting new nuclear weapons. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

For nuclear weapon advocates, the Minot incident in August 2007, where the Air Force lost track of six nuclear-armed cruise missiles for 36 hours, was a gift sent from heaven. No other event short of a nuclear attack against the United States could have provided a better opportunity to breathe new life into the declining nuclear mission.

But where is the line between fixing problems and advocacy?

Although the latest report from the Secretary of Defense Task Force on DOD Nuclear Weapons Management, also known as the Schlesinger report, contains many reasonable recommendations to ensure that the Services and agencies are capable of fulfilling the nuclear mission, it is also sprinkled with recommendations that have more to do with promoting nuclear weapons.

And it makes some remarkable claims about the deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe.

Fuzzy Tasking Leads to Fuzzy Focus

The leap from investigation to promotion is an unfortunate byproduct of the tasking Defense Secretary Robert Gates provided to the Schlesinger Task Force in June 2008. That letter not only directed the task force to examine accountability and control procedures for nuclear weapons to “sustain public confidence in the safe handling of DoD nuclear assets,” but also to “bolster a clear international understanding of the continued role and credibility of the U.S. nuclear deterrent.”

The task force appears to have taken the second objective a bit far.

Rather than being focused on fixing the problems that resulted in the Minot incident and several other events, the report reads like a second volume of the Defense Science Board (DSB) report from 2006 in which disgruntled nuclear advocates lamented a decline in support for the nuclear mission.

The Schlesinger report is, at times, a phenomenal concoction of Cold War nuclear jargon and claims made without presenting any evidence or analysis to support their continued validity. The report skips over the expansion from deterring nuclear to deterring all forms of WMD (it doesn’t even list the difference), and it suggests that U.S. nuclear weapons even have a mission against “violent extremists and nonstate actors.”

Nuclear Promotions

Anticipating that some elements of the nuclear posture will probably be cut in the future as a result of the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission, the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, and an potential arms control agreement with Russia, the Schlesinger report correctly states that such cuts “should be a reflection of policy decisions at the highest level rather than a result of Service preferences or budgetary concerns.” Given this conclusion, it is all the more noteworthy how the Schlesinger report throws itself into a blunt advocacy of nuclear posture issues that clearly should be the purview of the next administration.

Examples of posture recommendations that go beyond “accountability and control procedures” to promotion of new nuclear weapons include:

* Develop follow-on capabilities that can come online prior to expiration of the nuclear Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM-N) effectiveness or, should there be a gap, extend the TLAM-N service life commensurate with introduction of the new system.

* The Secretary of Defense should direct the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to develop validated operational requirements for modernizing or replacing the capabilities now provided by Dual-Capable Aircraft (DCA), Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM), and TLAM-N.

* Review and update the concept of operations for the TLAM-N to make it a more viable and responsive option for national leadership.

Clearly, these appear to be future posture decisions that are beyond the job the Schlesinger Task Force was asked to do.

The Extended Deterrence Confusion

The TLAM and DCA are weapons that are weapon systems that are both have roles in the extended deterrence mission. Yet the authors of the Schlesinger report repeatedly confuse the description of what extended deterrence means. Sometime they describe it as forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. At other times they describe as a nuclear umbrella extended over allies from afar.

For example, in the opening paragraphs of the section called “The Special Case of NATO,” the report concludes: “As long as NATO members rely on U.S. nuclear weapons for deterrence, no action should be taken to remove them without a thorough and deliberate process of consultation.”

Certainly NATO members should be consulted, but withdrawing “them” (which refers to the roughly 200 tactical nuclear bombs deployed in five European countries) hardly constitutes eliminating the entire U.S. nuclear weapons deterrent. A withdrawal from Europe would not be the end of the nuclear umbrella, as the Schlesinger report indicates, which could be continued by long-range forces just like it was in the Pacific after tactical nuclear weapons were withdrawn from South Korea in 1991.

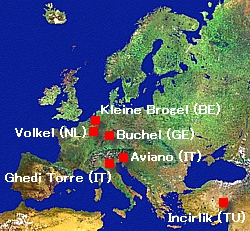

|

Figure 1: |

|

|

About 200 U.S. tactical nuclear weapons are deployed at six bases in five European countries. After the Blue Ribbon Review report in 2008 concluded that it would take considerable additional resources for security at European nuclear sites to meet DOD standards, the Schlesinger report now concludes that everything is fine. |

The Deployment in Europe

One of the most interesting parts of the report concerns the deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. Unfortunately, the European section is filled with sweeping statements and conclusions about the virtues of the deployment that are not supported by any accompanying analysis except deterrence jargon and echoes from the Cold War:

“Much of the deterrent value of NATO’s DCA deployment is derived from their in-theater presence, demonstrating and maintaining the capability to employ them. This creates in the minds of potential aggressors an unacceptable level of uncertainty concerning the success of any contemplated attack on NATO. This deterrent effect cannot be created by simply having nuclear weapons stored and locked up or relying exclusively on “over-the-horizon” nuclear delivery capabilities.”

It is? It does? It cannot? Why?

Many actually do believe – including apparently U.S. European Command (EUCOM) – that the deployment in Europe is not necessary anymore. But the authors of the Schlesinger report do not share that view and they spend a good portion of the report criticizing EUCOM for believing that “deterrence provided by USSTRATCOM’s strategic nuclear capabilities outside of Europe are more cost effective” and that “an ‘over the horizon’ strategic capability is just as credible.”

That assessment sounds pretty sound to me. But instead of accepting EUCOM’s assessment that forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe is not necessary for extended deterrence and a burden on real-world nonnuclear operations, the Schlesinger report brushes aside EUCOM’s “narrow assessment.” It is a much broader issue, the authors’ claim, about Russia, flexible regional nuclear deterrence (although the weapons are not targeted against anyone), and a trans-Atlantic link between Europe and the United States. But as far as the tactical nuclear weapons in Europe are concerned, that link was a Cold War link between a Soviet conventional invasion of Europe and U.S. strategic nuclear weapons, a concept that is getting a little dated. And if the glue in NATO depends on forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons, then I think the alliance is in deeper trouble that people normally think.

Interestingly, one person who shares the view of EUCOM was recently selected to become national security advisor to President-elect Barack Obama: General James L. Jones. When he was the head of EUCOM and Supreme Allied Commander Europe in 2005, the New York Times reported that Jones “has privately told associates that he favors eliminating the American nuclear stockpile in Europe, but has met resistance from some NATO political leaders.”

|

Figure 2: |

|

| Unlike the authors of the Schlesinger report, General (Ret.) James Jones, who is President-elect Obama’s national security advisor and former Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR), reportedly favors a withdrawal of tactical nuclear weapons from Europe. |

.

Shortly before the U.S. in 2005 and 2006 secretly withdrew half of the nuclear weapons from Europe – including all weapons from the United Kingdom, Jones told a Belgian Senate committee: “The reduction will be significant. Good news is on the way.” NATO sources attempted to downplay the issue by claiming Jones had not mentioned nuclear weapons specifically, but the Belgian government later stated for the record that, “the United States has decided to withdraw part of its nuclear arsenal deployed in Europe….” German weekly Der Spiegel followed up by asking “whether German nuclear weapons sites will benefit from Gen. Jones’ ‘good news.’” They did: all weapons were withdrawn from Ramstein Air Base.

The authors also leave out that the European political landscape on the tactical nuclear weapons issue has changed dramatically since the justifications the authors use were concocted. An overwhelming majority of the public today favors a withdrawal, the German government parties favor a withdrawal, and the Belgium Senate has unanimously called for a withdrawal. While ignoring those views, the Schlesinger report instead refers to anonymous allies who allegedly have expressed concern over calls for a unilateral withdrawal.

Who are those allies? From what department in the government bureaucracies did the officials that sent those signals come from? Whenever I mention these “allied concerns” during conversations with European government officials, they always smile because they know quite well that what’s a play here is a small group of nuclear bureaucrats deep within the ministries of defense who are defending their own turf. [There are some hints here; none of them seem to be directly related to the deployment in Europe].

Extended Deterrence as Nonproliferation

Another prominent assertions in the NATO section of the report is that by holding a nuclear umbrella over allied countries – by promising to retaliate with nuclear weapons if they are attacked by nuclear weapons (or weapons of mass destruction, as the authors say) – U.S. nuclear weapons prevent allied countries from developing nuclear weapons themselves. This sure sounds good and is a popular claim, but how widespread is this effect.

The report states that the United States has “extended its nuclear protective umbrella to 30-plus friends and allies.” The countries are not identified, but most of them are known:

NATO (25): Albania, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Turkey.

ANZUS (2): Australia, New Zealand.

Northeast Asia (3): Japan, South Korea, Taiwan .

That’s 30, so who are the remaining -plus countries are that the authors say are covered by the U.S. umbrella? France and the U.K. obviously don’t need it because they have their own nuclear deterrents. So do Israel and India. Are there non-nuclear allies in the Middle East that are under the umbrella?

|

Figure 3: |

|

|

A NATO briefing in 2006 acknowledged serious pressure for a withdrawal of nuclear weapons. Click image to download. |

The Schlesinger report recommends that the views of those 30-plus countries should be included in U.S. nuclear policy guidance documents. That would indeed be interesting, given that many of the countries actually have policies that favor a total withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Europe, elimination of non-strategic nuclear weapons, and total nuclear disarmament – political realities the report completely leave out.

Although all 30-plus are used to underscore the virtue of extended deterrence, how many of them would seriously consider acquiring their own nuclear weapons if things changed? Denmark? Iceland? Lithuania? Luxembourg? Portugal? New Zealand? Seriously! Only a few of the 30 are normally considered potential nuclear weapon proliferators: Germany, Japan, and perhaps South Korea.

It is probably also worth mentioning that two NATO countries – France and the United Kingdom – decided years ago to go nuclear even though the United States had thousands of nuclear weapons deployed to defend them. The report doesn’t mention why the NATO countries would not feel sufficiently protected by British or French nuclear forces in Europe.

The report also doesn’t mention that the United States since the early-1990 has maintained a nuclear umbrella over its allies in Northeast Asia without it requiring forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in those countries. Why is it possible to maintain extended deterrence with long-range nuclear weapons in the Pacific but not in Europe?

Conclusions and Remarks

Obviously the virtues of extended deterrence and the deployment in Europe are a little more nuanced than the Schlesinger report purports. But the central proposition that NATO and extended deterrence will go down the tube if tactical nuclear weapons were withdrawn from Europe seems preposterous.

It asks us to believe that if NATO really were attacked or threatened with nuclear (or, for those who believe nuclear weapons are also needed to deter chemical or biological weapons, WMD), U.S., British, and French ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), land-based missiles (ICBMs), and long-range bombers – along with all of NATO combined conventional military might (which is far more credible as a deterrent) – would sit idle in their bases because the political and military leaders somehow were incapable of reacting.

The decline in nuclear prowess that the Minot investigations have detected hasn’t simply happened because overstretched officers failed to do their job or the nation lost faith in nuclear weapons. It is a symptom, a hint. It has declined because nuclear weapons are no longer center and square to the national security of the United States nor its foreign policy. For sure, nuclear weapons haven’t gone away and there are still many challenges, but there are elements of the nuclear mission that are no longer essential and can and should be reassessed.

But the Minot investigations haven’t done that. Instead they have gone beyond fixing safety and security issues to using the incident to reaffirm status quo and reject change. Hopefully the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission and the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review can do better.

Cautious Interim Report From Congressional Strategic Posture Commission

|

| The interim report from the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States appears to reinstate Russia as a center for U.S. nuclear thinking. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States has published an interim report that buys into many of the arguments of the Bush administration, but also appears to accept some points made by the arms control community.

Overall, however, the report comes across as a cautious and somewhat lukewarm report that doesn’t rock the boat; that appears to reinstate Russia at the center of U.S. nuclear thinking; that strongly reaffirms extended nuclear deterrence (but ignores whether that requires U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe); that accepts many of the administration’s key arguments for modernizing the nuclear weapons production complex and building modified nuclear weapons; that accepts a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (if the Stockpile Stewardship Program is revitalized); that recommends additional reductions in deployed and (if the production complex is modernized) reserve warheads; that sees nuclear disarmament as a distant future dream; and accepts that a strong and credible nuclear posture likely will be needed for the “indefinite future.”

The findings will be subject to five months of debate before the full report is published in April 2009. After that the Obama administration is expected to conduct a Nuclear Posture Review.

Nuclear Déjà Vu At Carnegie

By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

Only one week before Barack Obama is expected to win the presidential election, Defense Secretary Robert Gates made one last pitch for the Bush administration’s nuclear policy during a speech Tuesday at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

What is the opposite of visionary? Whatever, that’s the word that best describes Mr. Gates’s speech. Had it been delivered in the mid-1990s it would not have sounded out of place. The theme was that the world is the way the world is and, not only is there little to be done about changing the world, our response pretty much has to be more of the same.

Granted, Gates’s job is to implement nuclear policy not change it but, at a time when Russia is rattling its nuclear sabers, China is modernizing its forces, some regional states either have already acquired or are pursuing nuclear weapons, and yet inspired visions of a world free of nuclear weapons are entering the political mainstream, we had hoped for some new ideas. Rather than articulating ways to turn things around, Gates’ core message seemed to be to “hedge” and hunker down for the long haul. And, while his arguments are clearer than most, this speech is yet another example of faulty logic and sloppy definitions justifying unjustifiable nuclear weapons.

They Do It So We Must Do It Too

Reductions cannot go on forever, Secretary Gates argues because there is still a mission for nuclear weapons. Using language from the Clinton Administration, he says we can reduce our arsenal but we must also “hedge” against unexpected threats. He said, “Rising and resurgent powers, rogue nations pursuing nuclear weapons, proliferation of international terrorism, all demand that we preserve this hedge. There is no way to ignore efforts by rogue states such as North Korea and Iran to develop and deploy nuclear weapons or Russian or Chinese strategic modernization programs.”

While the potential threats he lists are real and must be addressed, how do nuclear weapons address these threats? And even if there were some nuclear component to our responses, the nature of those responses would be so varied that lumping these threats together muddles the issue. A nuclear response to international terrorism? Even if, for example, al Qaeda used a nuclear weapon to attack an American city, what target would we strike back at with a nuclear weapon? The implicit argument of symmetry is unsustainable. Just as we don’t respond to roadside bombs with our own roadside bombs, nor would we respond to chemical attack with chemical weapons or biological attack with biological weapons. We might respond to nuclear attack with nuclear weapons but we should not allow this to be an unstated assumption. The reason rogue nations, let’s say Iran and North Korea, are developing nuclear weapons is not to counter our nuclear weapons but as a counter to our overwhelming conventional capability. They certainly are not making the mistake of implicitly assuming symmetry.

The near universal logical sleight of hand is to make some argument for nuclear weapons, let’s say we need them because North Korea has them, and then, when people nod in agreement that we need nuclear weapons, let slip in the assumption that this implies we need the nuclear arsenal the administration wants. Not so fast. If North Korea has one, perhaps we need two, but that does not mean we need two thousand.

It helps to clarify the typically foggy nuke-think if we remove Russia and China from the picture and ask whether the United States could justify anything near its currently planned nuclear arsenal only to deter and defeat rogue states and terrorists. Of course not. And perhaps we don’t need nuclear weapons for regional scenarios at all, given our overwhelming conventional capabilities. So those odds and ends are thrown into the pot just to scare, not to explain, and not because there is any well thought out strategy for how nuclear weapons are going to stop a terrorist attack on an American city, or why it be an appropriate response to a regional state that doesn’t have the capability to threaten the survival of the United States.

Russia is a very different case: Russian long-range nuclear forces are the only things in the world today that could destroy us as a nation and society, just as we could destroy them. While relations with Russia are not friendly, no conceivable difference between the United States and Russia justifies this mutual hostage relationship. This pointless threat to our very existence persists because of a failure of imagination typified by this speech. In this case, it is the nuclear weapons that are creating the threat, not protecting us from it.

That Ole Warhead Production Fever

Whatever the supposed justification of nuclear weapons, the primary purpose of the Secretary’s speech seemed to be to promote the Reliable Replacement Warhead or RRW but again, his argument rests on hidden (and unjustified) assumptions and, at times, misstatements of fact. The basic premise is that, without testing, we are slowly but certainly losing confidence in the reliability of our nuclear arsenal. He said, “With every adjustment, we move farther away from the original design that was successfully tested when the weapons was first fielded.”

We do? The implication is that we have no other choice, what we could do in 1990 we simply can’t reproduce today, like handing a modern-day native American a hunk of flint and asking him to chip out an arrowhead. Why should this be? With a budget of billions of dollars, we can’t duplicate parts that we could make twenty years ago? We can spend billions on the National Ignition Facility to create the world’s most powerful laser but we can’t reproduce a 1980s O-ring? The problem the Secretary describes is certainly possible and something we have to be alert to but it isn’t inevitable; we can maintain weapons within design margins as long as we want and in the past—pre-RRW—that was precisely the plan. And parts of the weapon that are not the nuclear core of the bomb can be improved and modernized and tested as much as we want.

But Mr. Gates claims that we are slowly and helplessly drifting, “So the information on which we base our annual certification of the stockpile grows increasing dated and incomplete.” This implies the Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP) has failed. We believe the Secretary is wrong. Everyone we have talked to who is familiar with the enormous effort that has gone into the SSP says that our understanding of nuclear weapons today is substantially greater than it was the day after our last nuclear test. Our knowledge of the aging of nuclear warheads is increasing faster than the warheads are aging. Early uncertainties and concerns about stability, for example, of the plutonium parts of the weapon have been resolved and the parts have been shown to be stable for many decades, if not a century or more. Our computer models are dramatically and significantly more detailed and sophisticated. In fact, one weapon designer has told us that, given a fixed budget, the best investment of your next dollar would never be in a nuclear test but in more inspections, more computer simulations, more replacement of non-nuclear components, more material tests, more frequent tritium replenishment, and so forth.

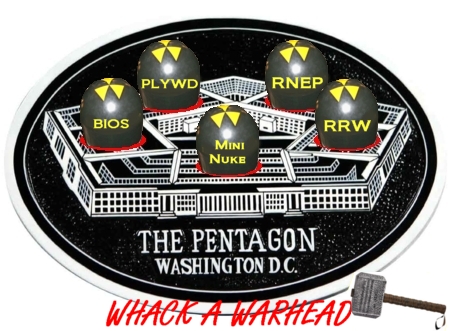

|

How Many Times Does Congress Have to Say No? |

|

| Every time the Pentagon has proposed a new nuclear warhead since the end of the Cold War, Congress has refused to fund it. Now that the RRW appears to have been whacked, what will the next proposal for a new warhead look like? |

.

Aside from the question of the reliability of current warheads, Mr. Gates argues that we still need an RRW because we need to modernize. The British, French, Russians, and Chinese are modernizing so we must too, obviously. Why? Nuclear weapons are a mature technology. There is no new science in nuclear weapons. They are powerful, efficient explosives. They are intended to blow up things and they have specific missions, which typically involve blowing up specific things. If they can accomplish these missions, what is the problem? If the technology, even the weapons, is decades, even centuries old, if they work then they work. Nuclear weapons are not fighter planes or tanks or submarines, duking it out on a battlefield with the enemy’s opposite number, so our nuclear weapons should be evaluated with regard to the targets they are expected to destroy, not anyone else’s nuclear weapons. They can destroy the targets. We’re done.

The important factor is not the warhead but the delivery vehicle that is intended to bring the warhead to the target. And the reason the United States is not producing new nuclear weapons while Russia and China do is not because they can and we can’t, or they’re ahead and we’re behind, as the Secretary indicated. Rather, the United States has not been producing new nuclear weapons because it didn’t have to – the existing ones are more than adequate – and because not producing has been seen as much more important to U.S. foreign policy objectives. And if Russian and Chinese warhead production is a problem, why not propose how to influence them to change rather than advocating that we repeat their mistake?

The final argument for the RRW is that the US must maintain a nuclear production industry and the RRW is grist for that mill. But many of the RRW technologies and capabilities were developed by the very SSP that Gates now implies is failing. Six years ago – before they came up with RRW after having failed to get permission to build the Precision Low-Yield Weapon Design (PLYWD) and the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP) – the National Nuclear Security Administration assured Congress: “We believe the life extension programs authorized by the Nuclear Weapons Council for the B61, W80, and the W76 will sufficiently exercise the design, production and certification capabilities of the weapons complex” (emphasis added). That assurance was given after the Foster Panel recommended, “developing new designs of robust, alternative warheads.” Now the claim suddenly is that the life extension programs do not sufficiently exercise the weapons complex. At least get the argument straight.

What’s Around the Corner?

We would be more sympathetic to the production argument if the fundamental minimal needs of the nuclear production industry were better thought out and justified, but what we see is an effort to maintain a slimmed down version of what we have without thinking through what we need. In fact, if maintaining the production industry is the core objective, we would have expected the administration to ask for an RRW design that doesn’t need a complex production industry, one that is extremely simple, perhaps using uranium rather than plutonium, perhaps a clunky design but one sure to work that does not require any sophisticated skills that must be maintained in standby in perpetuity.

We’re concerned that in the end Congress will accept a beefed-up life extension program – they seem to have already found a name for it: Advanced Certification Program – that will relax the restrictions for what modifications can be made to existing warheads in order to incorporate as much as the RRW concept as possible and add new capabilities if necessary. Unless the next president significantly changes the nuclear guidance for what the Pentagon is required to plan for, RRW-like proposals will likely continue to make it harder to create a national consensus on the future role of nuclear weapons. And Barack Obama has not explicitly rejected the RRW, but said he does “not support a premature decision to produce the RRW” and “will not authorize the development of new nuclear weapons and related capabilities.” Enhanced life-extended warheads could fit within such a policy.

In the end, justifying the nuclear weapons production industry is shaky because the justification for the weapons themselves is shaky, resting on assertion and Cold War momentum – as Gates’ speech illustrated – more than on rigorous assessments of missions and the security of the nation.

The Secretary’s speech was a disappointing missed opportunity. We are a bit perplexed about why he gave it and gave it now. Perhaps he is putting down a marker for a debate he expects in the next administration and Congress. We welcome that debate because we believe that, with careful attention to definition and no hidden assumptions, the arguments for nuclear weapons fade away.

Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Secrecy And Confusion

|

| Sorry, can’t tell! The size of the nuclear weapons stockpile is secret, but not hard to figure out. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

In a letter to the editor in Boston Globe, Thomas D’Agostino, the administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), writes that the United States is reducing its nuclear weapons and that, “Currently, the stockpile is the smallest it has been since the Eisenhower administration.”

That statement leaves considerable confusion about the size of the stockpile. If “since the Eisenhower administration” means counting from 1961 when the Kennedy administration took over, that would mean the stockpile today contains nearly 20,000 warheads. If it means counting from the day the Eisenhower administration took office in 1953, it would mean fewer than 1,500 warheads.

Why leave an order of magnitude of confusion about the size of the nuclear weapons stockpile?

Stockpile History

Neither number is correct. The actual stockpile size today, based on what I and my colleagues at NRDC can piece together, is approximately 5,300 warheads, or roughly the size of the stockpile in 1957 (see Figure 1). That is certainly a lot less than the 1980s, but it’s also an awful lot for the 21st century.

|

Figure 1: |

|

| The size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile has declined ever since the mid-1960s, and currently includes roughly 5,300 warheads, or approximately the size of the stockpile in 1957. When all announced reductions have been implemented in 2012, the size of the stockpile will have returned to the 1956-level of approximately 4,600 warheads. |

.

Mr. D’Agostino is, of course, in a bind because even though he and others at NNSA might agree that the stockpile size could be declassified, the Department of Defense insists it has to be kept secret. Even disclosing the number of nuclear weapons dismantled each year is prohibited, because it could help reveal the size of the nuclear stockpile. As it turns out, warhead dismantlement during the Bush administration has been the lowest since 1956 (see Figure 2).

|

Figure 2: |

|

| Even with the recent announcement of an “astounding 146 percent increase” in warhead dismantlement in 2007 and another 20 percent in 2008, the Bush administration’s dismantlement rate remains the lowest of any administration since 1956. |

.

What motivates this secrecy, other than the usual resistance to transparency in nuclear weapons matters, is preparation for a world of smaller nuclear arsenals a decade or two from now, when the United States might have reduced the number of deployed nuclear weapons to perhaps 1,000 or even less. In such a world, some fear, Russia or China might suddenly turn for the worse and secretly increase their nuclear arsenals and change the strategic balance. Knowing how many nuclear weapons the United States holds in reserve to increase the deployed force could, so the argument goes, greatly affect the U.S. ability to act and protect its allies. It’s kind of like reverse psychology: With fewer nuclear weapons it matters more what adversaries know.

A Policy For The Future

Keeping the size of the stockpile secret might have been a valid national security requirement during the Cold War, even though I don’t find the arguments very convincing. But today, nearly two decades after the Cold War ended, it is fair to ask: So what if potential adversaries know how many nuclear weapons the United States has?

If my colleagues and I can make a fairly accurate estimate, so can Russia and China. How can anyone in this day and age seriously argue that it matters that they’re 10-100 warheads off? And isn’t it better that they and our allies know the truth, instead of making their own assumptions?

More importantly, however, is that the stockpile and dismantlement numbers today are very effective instruments for showing the world that the United States is not building up its nuclear arsenal. They reassure allies and deprive adversarial hardliners the uncertainty they need to argue for nuclear modernization. Stockpile transparency, not worst-case breakout and warfighting theories, combined with an aggressive and sustained foreign policy effort to engage other nuclear weapon states, should be the priority for the next administration.

Background Information: Status of World Nuclear Forces 2008 | US Nuclear Force 2008 | Russian Nuclear Forces 2008 | Chinese Nuclear Forces 2008