Testing the No-New-Nuclear-Weapons Pledge

|

| The Air Force is considering a replacement for the nuclear air-launched cruise missile. Will the NPR agree or adhere to Barack Obama’s no-new-nuclear-weapons pledge? |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen [updated March 18, 2010]

One of the important tests of Obama Administration’s nuclear nonproliferation policy will be whether the long-delayed Nuclear Posture Review will approve new nuclear weapons.

During his election campaign, Barack Obama promised not to build new nuclear weapons, a pledge that recently has been reiterated by the administration.

Yet the Air Force’s budget request for 2011 includes several projects that, if approved, would contradict the pledge.

The “No New” Pledge

During the presidential election campaign, Barack Obama pledge to “stop the development of new nuclear weapons” if elected president. The pledged lived on for the first few months after the election on the Obama administration’s White House foreign policy web page, but disappeared when the page was reorganized at the time of the Prague speech in April 2009.

Since the, the president has, to my knowledge, not repeated the pledge. But Under Secretary of State Ellen Tauscher echoed the election pledge last month when she explained that the Pentagon says it does “not need new nuclear weapons capabilities. They just want to be confident in what we have,” she said and declared: “We are not in the business of seeking new nuclear capabilities. They are not needed to preserve a strong, credible deterrent.”

New Nuclear Weapons

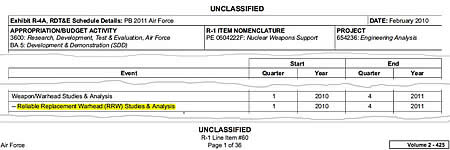

Yet “new” seems to be an elusive term. Even though Tauscher promised that the “RRW is dead and is not coming back,” the Air Force nuclear weapons support program includes “Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW) Studies & Analysis” in both 2010 and 2011. Perhaps she meant RRW as it was known rather than ruling out future replacement warheads. [Update March 18, 2010: The US Air Force now says the reference to RRW studies and analysis is an error and that the item mistakenly was left in the budget request from the previous year]

| More RRW Studies? |

|

| Despite a promise that the “RRW is dead and is not coming back,” the Air Force budget request includes RRW studies and analysis in both 2010 and 2011. Click for larger version. |

.

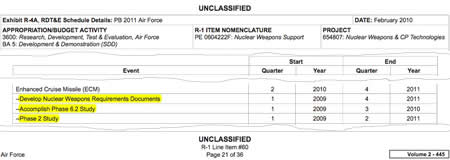

Another apparent contradictions with the administration’s no new nuclear weapons pledge is a new nuclear cruise missile to replace the current Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM) that expires in 2030. The new weapon is known as the Enhanced Cruise Missile (ECM), and development of nuclear weapons requirements documents are planned for 2010 and 2011, along with a Phase 6.2 Study, also known as a Feasibility Study and Option Down Select study. [Update March 18, 2010: The US Air Force now says the reference to the ECM is an error and that the item mistakenly was left in the budget request from the previous year. But the reference to the LRSO is not an error]

| A New Nuclear Cruise Missile? |

|

| The Air Force budget request includes what appears to be a replacement for the nuclear Air Launched Cruise Missile. Will the NPR approve? Click for larger version. |

.

The Enhanced Cruise Missile appears to be part of a program known as the Follow-On Long Range Stand-Off (LRSO) Vehicle to develop a replacement for the Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM).

The plan includes production of the Initial Capabilities Document (ICD) in early 2010, a Material Development Decision (MDD) in September 2010, and an Acquisition Decision in late 2011 or 2012. With that timeline, the NPR will have to make a decision.

New or Modified Warhead

One question is whether the new cruise missile will use a modified version of the existing W80-1 warhead currently deployed on the ALCM for B-52 delivery, or require development of a new warhead.

|

| A W80-1 warhead is mated with an ALCM. |

Until 2006, a life extension program (LEP) existed to extend the life of the W80-1. The LEP version was called W80-3. A parallel program to extend the W80-0 warhead would have produced the W80-2. But the Bush administration decided to “defer” the programs in pursuit of the RRW. That effort failed but the W80 LEP is still “archived,” according to the Air Force FY2011 budget request.

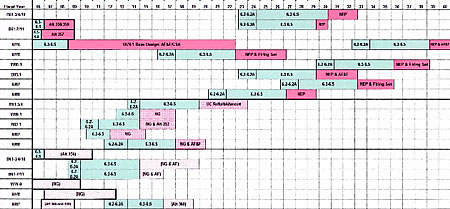

The remaining W80-1 warheads are scheduled to receive new neutron generators in 2015-2017, but a refurbishment of the nuclear explosive package is not planned until 2036-2039, according to the NNSA’s FY09 refurbishment planning schedule (no schedule exists yet for FY2010 or FY2011). No life-extension is planned for the W80-0, which will be retired.

| Warhead Refurbishment Plan? |

|

| The National Nuclear Security Administration’s nuclear warhead refurbishment plan does not include a formal life-extension program for the W80-1 warhead. An expensive program would be added if the NPR approves the Air Force’s cruise missile plan. Chart obtained under FOIA. Click for larger version. |

.

A decision to use a modified version of the existing W80-1 in the new cruise missile would involve reviving the $200 million per year W80-3 LEP program.

New or Just “New”

Nuclear weapons modernization programs risk triggering a contentious debate similar to the dispute over the RRW and whether Obama’s no-nuclear-weapons pledge can be trusted.

Does a new “weapon” refer to the warhead on the missile or the delivery vehicle itself or both? And how new must a weapon be to be considered “new” – does it require an entirely new design or can a modified design be considered a “new” weapon?

Government officials have to be crystal clear when they present the results of the NPR to make sure the administration’s nonproliferation policy doesn’t get stuck in the mud of misunderstandings and contradictions about what constitutes a “new” nuclear weapon. A lot is at stake.

Additional Information: Pentagon Eyes More Than $800 Million for New Nuclear Cruise Missile

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Changing the Nuclear Posture: moving smartly without leaping

Release of the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) is delayed once again. Originally due late last year, in part so it could inform the on-going negotiations on the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty Follow-on (START-FO), after a couple of delays it was supposed to be released today, 1 March, but last week word got out that it will be coming out yet another 2-4 weeks later. Some reports are that the delay reflects deep divisions within the administration over the direction of the NPR. That means that there is really only one person left whose opinion matters and that is the president.

We can only hope that President Obama makes clear that he meant what he said in Prague and elsewhere. This NPR is crucial. If it is incremental, if it relegates a world free of nuclear weapons to an inspiring aspiration, then we are stuck with our current nuclear standoff for another generation. This is the time to decisively shift direction. But we should not be paralyzed by thinking that the only movement available is a giant leap into the unknown. We need to move decisively in the right direction, sure, but we can do that in steps. (more…)

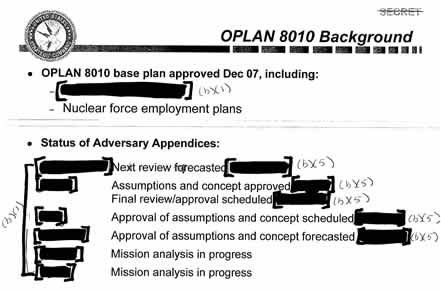

Obama and the Nuclear War Plan

|

| The current U.S. strategic war plan is directed against six adversaries. Guess who. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

While the completion of the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review continues to slide, FAS today published an issue paper on how a decision to reduce the role of nuclear weapons might influence the U.S. strategic war plan.

President Obama pledged in his Prague speech last year that he would “reduce the role of nuclear weapons” to “put an end to Cold War thinking,” and reaffirmed earlier this month that the “Nuclear Posture Review will reduce [the] role….”

How to reduce the role in a way that is seen as significant by the global nonproliferation community, visible to adversaries, and compatible with the president’s other pledge to “maintain a safe, secure and effective arsenal to deter any adversary…as long as these weapons exist” apparently is the subject of a heated debate within the administration.

|

| Click image to download report. |

The most persistent rumor is that the review might remove a requirement to plan nuclear strikes against chemical and biological weapons; reduce the mission to the core role of deterring use of other nuclear weapons. I recently described that the Quadrennial Defense Review stated that new regional deterrence architectures and non-nuclear capabilities “make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.”

A reduction of the mission to only deter nuclear use would roll back much of the expansion of nuclear doctrine that happened during the Clinton and Bush administrations. But it would not “put an end to Cold War thinking,” but to post-Cold War thinking.

To put an end to Cold War thinking, the reduced role would have to affect the core of the war plan that is directed against Russia and China.

The issue paper describes how the strategic war plan is structured, how it has evolved, and discusses options for reducing the mission and the war plan itself.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Kleine Brogel Nukes: Not There, Over Here!

|

| The U.S. Air Force’s 701 Munitions Support Squadron at Kleine Brogel Air Base must protect and handle the nuclear weapons at the base. |

An astounding statement by a Belgian defense official has pointed an unexpected light on the apparent location of nuclear weapons at the Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium.

After a group of peace activists climbed the base fence and made their way deep into an area assumed to store nuclear weapons, Ingrid Baeck, a chief spokesperson for the Belgian Ministry of Defense, bluntly told Stars and Stripes: “I can assure you these people never, ever got anywhere near a sensitive area. They are talking nonsense….It was an empty bunker, a shelter,” she said and added: “When you get close to sensitive areas, then it’s another cup of tea.”

Baeck did not go so far as to explicitly confirm or deny if there were nuclear weapons on the base, but the Belgium Ministry of Defense’s mission statement for the 10th Tactical Wing clearly shows that it has a nuclear mission (see Figure 1).

| Figure 1: Belgian 10th Tactical Wing Mission |

|

| The Belgian Ministry of Defense’s mission statement for the 10th Tactical Wing (10 W Tac) at Kleine Brogel clearly lists a nuclear mission. Emphasis added. |

.

Shelter Searching

It is unclear whether Baeck as a spokesperson actually knows where the weapons are stored or if “sensitive area” only refers to the particular shelter the activists reached. But her statement that the activists “ever got anywhere near a sensitive area” inadvertently redirects the attention to the western area of the base.

Kleine Brogel has 26 Protective Aircraft Shelters (PAS) located in three clusters: Area 1 at the western part of the base with 11 shelters; Area 2 at the center of the base also with 11 shelters; and Area 3 at the eastern end of the base with four shelters (see Figure 2).

| Figure 2: Nuclear Weapons Storage Areas |

|

| Estimated locations for nuclear weapons at Kleine Brogel Air Base have changed over the years. Click image for large version. |

.

During the Cold War, nuclear weapons were stored in the Weapons Storage Area northeast of the base, while aircraft loaded with nuclear weapons stood alert in the shelters in Area 3.

Area 2 has long been the suspected nuclear weapons storage area, given its 11 shelters, pronounced fencing, and separation from the outer base perimeter. This is the area the activists managed to penetrate on January 31st.

Baeck’s statement appears to draw the attention to Area 1 at the western end of the base where 11 shelters are clustered. It also has an additional fence perimeter that appears to have been improved since 2006, but the gates were open on a satellite image dated April 8, 2007. Moreover, the area is close to the outer base fence, with the busy N748 highway only 225 feet (68 meters) from one shelter and another shelter only 134 feet (40 meters) from a residential neighborhood. Jeffrey L also has an interesting photo interpretation.

Whether the nuclear shelters necessarily have to be in one cluster inside the same perimeter is unknown, although safety and management issues seem to suggest so.

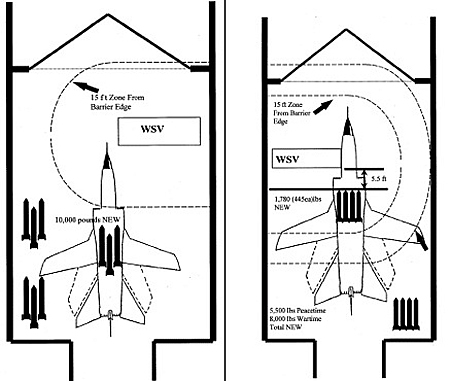

The Weapons Security and Storage System (WS3)

Only 11 of the 26 Protective Aircraft Shelters at Kleine Brogel are equipped with the Weapons Storage Security System (WS3), a nuclear weapons storage system unique to Europe. The system at Kleine Brogel was completed in 1992.

The mechanical part of the WS3 includes a Weapons Storage Vault (WSV), a reinforced concrete foundation and a steel structure recessed into the floor of the shelter. The vault platform can be elevated out of the concrete foundation by means of an elevator drive system to provide access to the weapons in two stages or levels, or can be lowered into the floor to provide protection and security for the weapons. The floor slab is approximately 16 inches (40 cm) thick. Sensors to detect intrusion attempts are embedded in the concrete vault body.

Each of the 11 vaults can store up to four B61 bombs, but normally contains only one or two for a total of 10-20 bombs currently at Kleine Brogel.

Location of the vault inside the shelter depends on the size of the shelter and the proximity of conventional weapons storage racks. Two layouts are in use (see Figure 3), and the vaults at Kleine Brogel are the smaller located at the front-left end of the shelter.

| Figure 3: Weapons Storage Vaul Locations |

|

| The location of the underground Weapons Storage Vault depends on the size of the aircraft shelter. Kleine Brogel shelters use the right-hand layout. |

.

The vaults are rarely visible on photos from outside the shelters, but in this unique photo (see Figure 4) taken at nearby Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands in 2009 the outline of the vault can be seen in the front-left corner (right in the picture) of the shelter.

| Figure 4: External View of Munitions Storage Vault |

|

| A vault cover is visible inside this shelter at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands. The picture of the specially painted F-16 (no. J-015) was taken during a pilot ceremony in 2009. Reprinted with permission. Original photo at Touchdown Aviation. |

.

The vault can be elevated in two stages, halfway to provide access to the top rack, or fully to provide access to the lower rack as well. An example of halfway elevation is the photo below showing the command of U.S. Air Forces in Europe, General Roger Brady, receiving a briefing next to a vault at Volkel Air Base in June 2008 (see Figure 5) (he also visited Kleine Brogel). The visits happened shortly after the Blue Ribbon Review report concluded that “most sites” storing nuclear weapons in Europe did not meet DOD security standards.

| Figure 5: Halfway Elevation of Weapons Storage Vault |

|

| This picture, taken inside a shelter at Volkel Air Base, shows Gen. Grady receiving a briefing from a member of the 703rd MUNSS. The vault is halfway raised showing one B61 bomb, with the lower bomb rack hidden below the floor level. |

.

If fully elevated the vault appears as on the image below (see Figure 6). The base name is unknown, but given the location of the vault it appears to be inside a large shelter at a U.S. base, possibly Aviano Air Base in Italy or Ramstein Air Base in Germany (all B61s were removed from Ramstein in 2005).

| Figure 6: Full Elevation of Weapons Storage Vault |

|

| Full elevation of the Weapons Storage Vault inside what appears to be an aircraft shelter at Aviano Air Base or Ramstein Air Base. |

.

What is Security?

Kleine Brogel base commander Col. Fred Vansina insisted that the penetration of the base by the activists did not constitute a security incident: “Our installations are very well secured, in different ways,” there was “no single security incident, whatever the activists claim.”

A nuclear base is a sensitive area and unauthorized personnel meandering around deep inside its inner perimeters is a security incident, but Vansina’s definition appears to require an unauthorized and dangerous approach of a nuclear facility. Both he and Baeck have great confidence in the WS3 and the security forces’ ability to protect the weapons under all circumstances.

I agree that it would be very difficult for anyone to steal or destroy the weapons under normal circumstances when they’re stored underground. But it is the abnormal circumstances that concern me; weapons are occasionally brought up from the vault, serviced, and moved (see Figure 7). Overconfidence is dangerous because incidents and accidents have a nasty habit of happening in ways that were not anticipated. And that requires us to weigh the risks against the necessity of the deployment, a necessity I have an increasingly hard time to see.

| Figure 7: Halfway Elevation of Weapons Storage Vault |

|

| The safety of the underground Weapons Storage Vault no longer applies when nuclear bombs in Europe are brought up for maintenance or transport. A 1997 Air Force study even found a risk of lightning causing a nuclear detonation. |

.

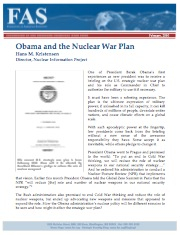

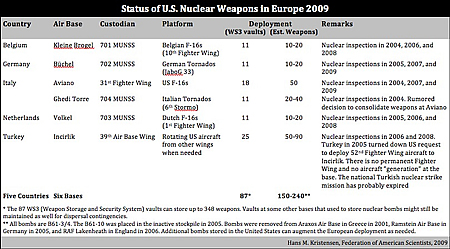

Status of Nuclear Weapons in Europe

The 10-20 weapons at Kleine Brogel are part of a stockpile of an estimated 150-200 U.S. nuclear bombs scattered in 87 vaults at six bases in five countries, a reduction from approximately 480 bombs in 2001. My current estimate looks like this (see Figure 8):

| Figure 8: |

|

| Click image to download larger pdf-version. |

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

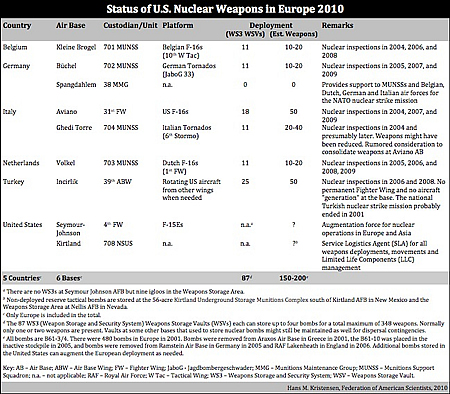

US Nuclear Weapons Site in Europe Breached

|

| Peace activists walked one kilometer onto a US nuclear weapons storage site in Belgium for more than one hour before security personnel reacted. Click image for larger version. (For an update to this map, go here) |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A group of people last week managed to penetrate deep onto Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium where the U.S. Air Force currently deploys 10-20 nuclear bombs. (For an update to this blog, go here)

Fortunately, the people were not terrorists but peace activists from a group known as Vredesactie, who managed to climb the outer base fence, walk cross the runway, breach a double-fenced security perimeter, and walk into the very center of the air base alongside the aircraft shelters where the nuclear bombs are thought to be stored in underground vaults.

A Nuclear Cake Walk |

|

| The activists climbed the outer base fence (1), breached the inner double-fence (2), tagged a nuclear aircraft shelter (3), walked across the tarmac (4), before being arrested (5) after more than one hour inside the base. The numbers on the images correspond to the location of the numbers on the map above. |

The activists penetrated nearly one kilometer onto the base over more than an hour before a single armed security guard appeared and asked what they were doing. Soon more arrived to arrest the activists, who later described: “The military blindfolded for hours, they forced us to kneel in the snow, arms outstretched at 90° and threatened us if we intend to return to the base in the months to come.”

The activists videotaped their entire walk across the base. The security personnel confiscated cameras, but the activists removed the memory card first and smuggled it out of the base. Ahem…

In June 2008, I disclosed how an internal Air Force investigation had concluded that most nuclear weapons sites in Europe did not meet US security requirements. The Dutch government denied there was a problem, and an investigative team later sent by the US congress concluded that the security was fine.

They might have to go back and check again.

The nuclear bombs at Kleine Brogel are part of a stockpile of about 200 nuclear weapons left in Europe after the Cold War ended. Whereas nuclear weapons have otherwise been withdrawn to the United States and consolidated, the bombs in Europe are scattered across 62 aircraft shelters at six bases in five European countries. The 130-person US 701st Munitions Support Squadron (MUNSS) is based at Kleine Brogel to protect and service the nuclear bombs and facilities.

They might have to go back to training.

The activists will likely be charged with trespassing a military base but they should actually get a medal for having exposed security problems at Kleine Brogel. And this follows two years of the Air Force creating new nuclear command structures and beefing up inspections and training to improve nuclear proficiency following the embarrassing incident at Minot Air Force Base in 2007. Despite that, the activists not only made their way deep into the nuclear base but also discovered that the double-fence around the nuclear storage area had a hole in it! “We’re not the first,” one of the activists said.

NATO needs to get over its obsession with nuclear weapons and move out of the Cold War and the Obama administration’s upcoming Nuclear Posture Review needs to bring those weapons home before the wrong people try to do what the peace activists did.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Japanese Government Rejects TLAM/N Claim

|

| Katsuya Okada and Hillary Clinton met in September 2009. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Japanese government has officially rejected claims made by some that Japan is opposed to the United States retiring the nuclear Tomahawk Land-Attack Missile (TLAM/N).

The final report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States from May 2009 emphasized the importance of maintaining the TLAM/N for extended deterrence in Asia by referring to private conversations with specifically “one particularly important ally” (read: Japan) that “would be very concerned by TLAM/N retirement.”

In a letter sent to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on December 24, 2009, Japanese Foreign Minister Katsuya Okada explicitly says that the Japanese government has expressed no such views.

The Japanese Foreign Minister’s letter explicitly refers to the Commission: “It was reported in some sections of the Japanese media that, during the production of the report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States released in May this year, Japanese officials of the responsible diplomatic section lobbied your government not to reduce the number of its nuclear weapons, or, more specifically, opposed the retirement of the United States Tomahawk Land Attack Missile – Nuclear (TLAM/N) and requested that the United States maintain a Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP).

I don’t know who made a reference to RNEP (the Commission didn’t; perhaps it was a reference to earth-penetration capabilities in general rather than RNEP per ce), but Okada’s rejection of the TLAM/N claim is clear:

“[A]lthough the discussions were held under the previous Cabinet, it is my understanding that, in the course of exchanges between our countries, including the deliberations of the above mentioned Commission, the Japanese Government has expressed no view concerning whether or not your government should possess particular [weapons] systems such as TLAM/N and RNEP.” (my emphasis)

Okada’s statement suggests that he has checked the government’s files. It also matches the statement made by Admiral Timothy J. Keating, the former Commander of U.S. Pacific Command, in July 2009, that he was “unaware of specific Japanese interests in the” TLAM/N.

If the TLAM/N were retired, Okada says, Japan would of course like to be informed about how this would affect extended deterrence and how it could be supplemented. I hope “supplemented” means by other existing nuclear and non-nuclear means, not by new nuclear weapon system.

It seem so, because Okada writes that he favors nuclear disarmament, and he also expresses interest in the proposal made recently by the International Commission on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Nuclear Disarmament (ICNND) – and many others – that the role of nuclear weapons be restricted to deterrence of the use of nuclear weapons. That is important for the Japanese government to say because one of the current missions for U.S. nuclear weapons involve North Korean chemical and biological attacks on Japan. Apparently, closer consultations between the United States and Japan on extended deterrence issues would be a good idea.

It seems more and more that the TLAM/N claim resulted from a shady collusion between a few U.S. and Japanese officials (some current and some former) who sought to present private views as more than that in an effort to put brakes on the Obama administration’s disarmament agenda.

Hopefully the pending Nuclear Posture Review will not be led astray.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Doctrine and Missing the Point.

The government’s much anticipated Nuclear Posture Review, originally scheduled for release in the late fall, then last month, then early February is now due out the first of March. The report is, no doubt, coalescing into final form and a few recent newspaper articles, in particular articles in Boston Globe and Los Angeles Times, have hinted at what it will contain.

Before discussing the possible content of the review, does yet another release date delay mean anything? I take the delay of the release as the only good sign that I have seen coming out of the process. Reading the news, going to meetings where government officials involved in the process give periodic updates, and knowing something of the main players who are actually writing the review, what jumps out most vividly to me is that no one seems to share President Obama’s vision. And I mean the word vision to have all the implied definition it can carry. The people in charge may say some of the right words, but I have not yet discerned any sense of the emotional investment that should be part of a vision for transforming the world’s nuclear security environment, of how to make the world different, of how to escape old thinking. As I understand the president, his vision is truly transformative. That is why he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. His appointees who are developing the Nuclear Posture Review, at least the ones I know anything about, are incredibly smart and knowledgeable, but they are also careful, cautious, and, I suspect, incrementalists who might understand intellectually what the president is saying but don’t feel it (and, in many cases, fundamentally don’t really agree with it). A transformative vision not driven by passion will die. As far as I can see (and, I admit, I am not the least bit connected so perhaps I simply cannot see very far) the only person in the administration working on the review who really feels the president’s vision is the president. Much of what I hear from appointees in the administration has, to me at least, the feel of “what the president really means is…” If the cause of the delay is that yet more time is needed to find compromise among centers of power, reform is in trouble because we will see a nuclear posture statement that is what it is today neatened up around the edges. But if the delay is because the president is not getting the visionary document he demands, delay might be the only hopeful sign we are getting.

Now, onto the possible content of the review: The main question to be addressed by the review is what the nuclear doctrine and policy of the United States ought to be. This has sparked a secondary debate about just how specific any declaration of policy should be and the value of declaratory policy at all.

Some hints coming out of the administration suggest that the new review may explicitly state that the sole purpose of nuclear weapons be specifically limited to countering enemy nuclear weapons, what we and others have called a “minimal deterrence” doctrine. Currently, the United States claims that chemical and biological weapons may merit nuclear attack and that could go away with the current review.

Most reports leaking out from the review participants hint that the NPR almost certainly will not include a declaration that the United States will not be the first to use nuclear weapons. The current U.S. policy is to intentionally maintain ambiguity about how and when we might use nuclear weapons, to keep the bad guys guessing. The new review could keep that basic idea and still be a little less ambiguous around the edges.

Some question the value of having a declaratory policy at all. For example, if a no-first-use policy can be reversed by a phone call from the president, what does it actually mean? As Jeffrey Lewis argues, if having a declared policy causes an intense drilling down into what-ifs, it can increase suspicion and do actual harm. (Although the example Lewis offers raises questions about whether China should have a no-first-use policy and is not particularly relevant to whether the U.S. should.)

A bigger problem with any declaratory policy is figuring out what it actually means. Do we agree on what “no first use” means? I think it means that we will not be the first to explode a nuclear weapon. But, for example, in a recent article in Foreign Affairs, Lieber and Press argue that the United States could be justified in using nuclear weapons if an adversary first “introduced” nuclear weapons into a conflict, where “introduce” might be to explode one, but might also include putting them on higher alert, moving them, or simply implying their relevance to the contest. So a nuclear war-planner and I could agree on a no-first-use policy and have differing, almost opposite, views of what that meant.

But if statements of doctrine don’t mean anything, then why the big deal? Why would the nuclear establishment invest any political capital fighting for or against them? While it is true that doctrinal statements are always taken with a huge grain of salt by other nations (just as the United States applies a steep discount to statements coming from others), they do make a difference in the domestic debate. In the previous administration, the Department of Energy went to the Congress with a request to build a new facility to build the plutonium cores or “pits” for 250 new nuclear warheads every year. This made no sense whatsoever; it was completely out of synch with our own plans for future nuclear forces and Congress voted it down because the DOE was not remotely able to justify its request. The DOE proposal went down to 125, then 80, and some current variations on the basic proposal are for a dozen or so, which actually makes some sense.

So doctrine and declaratory policy are important in very concrete ways when they can affect force structure decisions, including the numbers and types of weapons we have, their capabilities, and how they are deployed. Moreover, these are the sorts of changes that other nations will see and pay attention to.

The uncertainty of the link between words and weapons is what causes wariness on every side of the debate. Foreign governments might not believe our declarations but such declarations might form the basis for changes in the U.S. nuclear force structure, with all the implications for budgets and personnel, weapons, bases, and jobs back home. That is why the nuclear establishment is resisting. On the other hand, those who desire fundamental and profound change could be completely hoodwinked by nice sounding words that allow the status quo to coast ahead on its own momentum.

The danger I see is that, if discussion is so tightly focused on what we say, then too little attention will be given to what we do. If we take our declarations seriously, they should have profound effects on the nuclear posture but I can imagine big changes in the review with little real physical change actually resulting. For example, if we take seriously a no-first-use policy, our deployment of forces could be radically different. Reentry vehicles could be stored separated from their missiles, missiles in silos could be made visibly unable to launch quickly, for example, by piling boulders over the silo doors. Much of the ambiguity in any verbal statement of doctrine is squeezed out when we discuss the concrete questions of what the forces look like. The nuclear war-planner and I might have effectively opposite definitions of “no first use” but we would agree entirely on what it means to piles boulders on our ICBM silo doors.

What I would hope to see come out of the NPR is not simply a statement of no first use but a plan for, for example, taking our nuclear weapons off alert. We will certainly hear that nuclear weapons are for deterrence, perhaps that they are only for deterrence. But that has become utterly meaningless because the definition of deterrence has been warped to the point that it can now be defined as whatever it is that nuclear weapons do. Indeed, nuclear weapons are often simply called our “deterrent.” Michele Flournoy, the current Undersecretary of Defense in charge of the NPR process, wrote a report while at CSIS describing how U.S. nuclear weapons should be able, among other things, to execute a disarming first strike against central Soviet nuclear forces, the better to “deter.” When a word has that much flexibility, I don’t care whether it gets included in the posture statement or not but I do care whether we mount our nuclear weapons on fast flying ballistic missiles or on slow, air-breathing cruise missiles.

If we take seriously some of the statements that might come out of the review, then we can start to imagine radically different force structures. For example, if the requirement for nuclear preemption is removed and the number of nuclear targets is substantially reduced, then new ways to base nuclear weapons become feasible. We could, for example, store missiles in tunnels dug deep inside a mountain where the missiles would be both invulnerable and impossible to launch quickly. We could invite a Russian to live in a Winebago on top of the mountain to confirm to his own nuclear commanders that we were not preparing our missiles for launch.

These are things the world can see. Indeed, if we have no interest in a first strike capability, we have every incentive to invite the world to come in and see for themselves. These are the types of changes that need to occur in the U.S. nuclear force structure and, if they do, debate about the words in the review is less important.

Estimated Nuclear Weapons Locations 2009

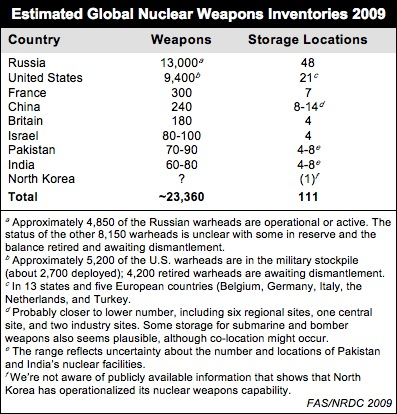

Some 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at 111 locations around the world

.The world’s approximately 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at an estimated 111 locations in 14 countries, according to an overview produced by FAS and NRDC.

Nearly half of the weapons are operationally deployed with delivery systems capable of launching on short notice.

The overview is published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and includes the July 2009 START memorandum of understanding data. A previous version was included in the annual report from the International Panel of Fissile Materials published last month.

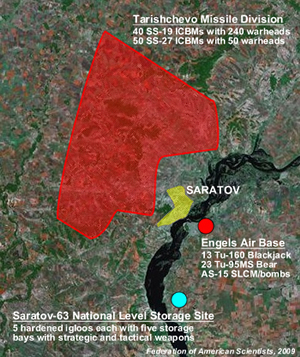

More than 1,000 nuclear weapons surround Saratov.

Russia has an estimated 48 permanent nuclear weapon storage sites, of which more than half are on bases for operational forces. There are approximately 19 storage sites, of which about half are national-level storage facilities. In addition, a significant number of temporary storage sites occasionally store nuclear weapons in transit between facilities.

This is a significant consolidation from the estimated 90 Russian sites ten years ago, and more than 500 sites before 1991.

Many of the Russian sites are in close proximity to each other and large populated areas. One example is the Saratov area where the city is surrounded by a missile division, a strategic bomber base, and a national-level storage site with probably well over 1,000 nuclear warheads combined (Figure 2).

The United States stores its nuclear weapons at 21 locations in 13 states and five European countries. This is a consolidation from the estimated 24 sites ten year ago, 50 at the end of the Cold War, and 164 in 1985 (see Figure 3).

Approximately 50 B61 nuclear bombs inside an igloo at what might be Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada. Seventy-five igloos at Nellis store “one of the largest stockpile in the free world,” according to the U.S. Air Force, one of four central storage sites in the United States.

Europe has about the same number of nuclear weapon storage locations as the Continental United States, with weapons scattered across seven countries. This includes seven sites in France and four in Britain. Five non-nuclear NATO countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey) still host U.S. nuclear weapons first deployed there during the Cold War.

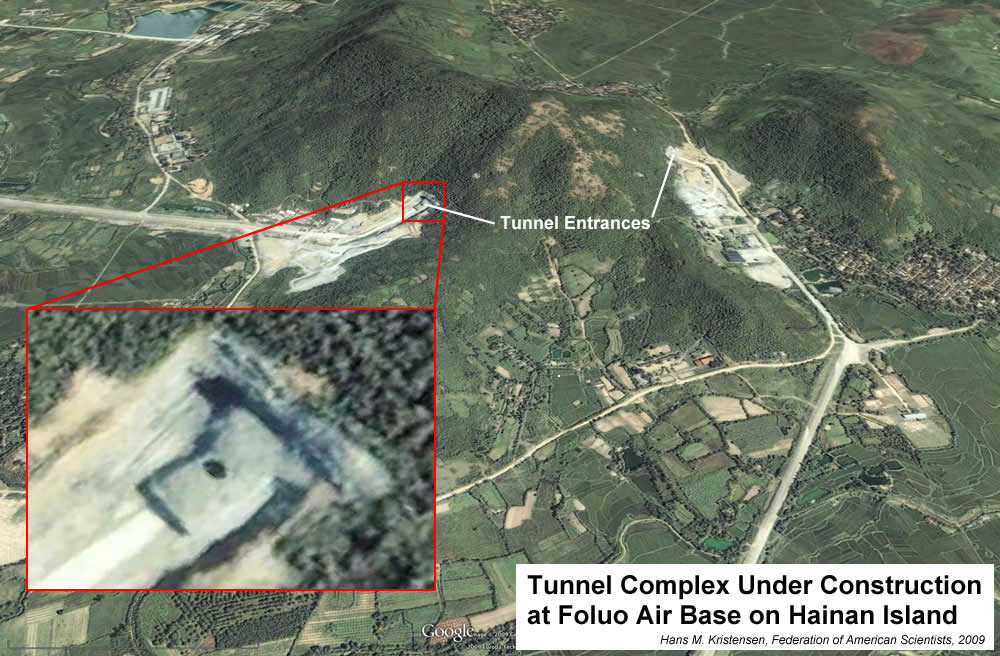

We estimate that China has 8-14 facilities associated with nuclear weapons, most likely closer to the lower number, near bases with units that operate nuclear missiles or aircraft. None of the weapons are believed to be fully operational but stored separate from delivery vehicles at sites controlled by the Central Military Commission.

Where does China store nuclear warheads for its ballistic missile submarines? The naval base near Julin on Hainan Island has extensive underground facilities. An alternative to the base itself could potentially be a facility elsewhere on the island, such as Foluo Air Base where construction of an underground facility began five years before the first SSBN arrived at Hainan. Or are the weapons stored on the mainland? Click image to enlarge.

Israel probably has about four nuclear sites, whereas the nuclear storage facilities in India and Pakistan are – despite many rumors – largely undetermined. All three countries are thought to store warheads separate from delivery vehicles.

Despite two nuclear tests and many rumors, we are unaware of publicly available evidence that North Korea has operationalized its nuclear weapons capability.

Warhead concentrations vary greatly from country to country. With 13,000 warheads at 48 sites, Russian stores an average of 270 warheads at each location. The U.S. concentration is much higher with an average of 450 warheads at each location. These are averages, however, and in reality the distribution is thought to be much more uneven with some sites only storing tens of warheads.

Finally, a word of caution is in order: estimates such as these obviously come with a great deal of uncertainty, as we don’t have access to classified intelligence estimates. Based on publicly available information and our own assumptions we have nonetheless produced a best estimate that we hope will assist the public debate. Comments and suggestions are encouraged so we can adjust the overview in the future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

JASON and Replacement Warheads

|

|

Claims that nuclear weapons need to be as safe as a coffee table might drive warhead replacement |

By Hans M. Kristensen and Ivan Oelrich

The latest study from the JASON panel is an unambiguous rejection of claims made by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), the nuclear weapon labs, defense secretary Robert Gates, and U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) that some or all U.S. nuclear weapons should be replaced to ensure the future reliability of the arsenal.

The executive summary of the study, Lifetime Extension Program (LEP), finds “no evidence that accumulation of changes incurred from aging and LEPs have increased risk to certification of today’s deployed nuclear warheads.” The study concludes that the lifetime of today’s nuclear warheads “could be extended for decades, with no anticipated loss in confidence, by using approaches similar to those employed in LEPs today.” [Emphasis added.]

The JASON appears to have prevented a wasteful and counterproductive nuclear warhead replacement program. Even so, we expect parts of the report’s conclusions to be used by proponents of nuclear warhead replacements in the months and years ahead.

The Surety Argument

With JASON’s rejection in 2006 that pit aging is a reason to build replacement warheads, and its latest conclusion that stockpile reliability is achievable with the existing Live Extension Programs, only two of the core justifications used by proponents of RRW remains: surety and training. (There is no agreed definition of the terms safety, security, and surety. The DOD defines that nuclear safety reduces the probability of accidental explosion of the warhead; security reduces the possibility of unintentional or unauthorized intentional use of the warhead; surety combines these aspects.)

The report leaves the door open for replacement warheads by concluding that addition of nuclear surety or use-control features to the nuclear explosive package of reentry vehicles on ballistic missiles (W76, W78, W87, and W88) “would require reuse or replacement LEP options.” Note that replacement warhead would not necessarily be a new design, but could be new components in an existing design.

Additional use-control, not warhead reliability, has thus become the main technical justification for building replacement warheads and we expect to see a sudden emphasis on surety by those who want to build new warheads.

This begs the questions: how much surety is enough, who sets the bar, and what is it worth?

All U.S. warheads contain one or several surety features to prevent unauthorized use and accidents (see Table). The last time the United States went through a stockpile-wide safety and security related upgrade was in the early 1990s. Back then several weapons were phased out because they didn’t meet new safety and security standards, and new features were added to others. Not all nuclear weapons were created equal, however, and those that were seen as too important to retire were allowed to remain in the inventory even thought they did not meet the standard. But they will be gone soon.

|

U.S. Nuclear Warhead Surety Features |

|

| All U.S. nuclear warheads have surety features but details vary greatly due to history and deployment. Click for table. |

.

After 9/11, the administration began arguing for raising the standard again. National Security Presidential Directive 28 (NSPD-28) issued in June 20, 2003, ordered the “incorporation of enhanced surety features independent of any threat scenario,” a capability-based safety philosophy based on technology rather than threats. Under the headline “Urgency of RRW,” NNSA Director Thomas D’Agostino told Congress in February 2008 that “after 9/11 we realized that the security threat to our nuclear warheads had fundamentally changed.”

We have repeatedly probed officials about this alleged change, and they say it has to do with fear that terrorists will do anything to steal and use a nuclear weapon. The theory was that terrorists would go to greater length to steal U.S. nuclear weapons than the Soviet Union. Existing security features and well-protected storage sites are no longer sufficient; a nuclear weapon must be as inherently safe against unauthorized use as a coffee table, as one senior official recently put it.

Who can be against safety of nuclear weapons? But if the price is several billion dollars then it is appropriate to ask what the surety and safety requirements are for U.S. nuclear weapons, how they have been set, by whom, and for what purpose. Another way to pose the question is: How will we know when we are done?

Since 9/11 the government has already spent huge sums to improve the physical security of nuclear weapons at bases and storage sites, and has upgraded use control features of some weapons. The safety of US nuclear weapons is probably better today than it has ever been. The greatest weakness is almost certainly administrative, as when military personnel loose track of the weapons, which happened in August 2007 at Minot Air Force Base. We also note that suggestions to increase surety by changing the deployment and readiness of nuclear weapons, for example, taking weapons off alert or removing warheads from missiles and storing them separately, are dismissed out of hand. So there are some actions that could improve surety that are clearly out of bounds.

The claim that the weapons themselves have to be made even more secure came later. It was not a prominent component of the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review, and a concurrent review of “all activities involved in maintaining the highest standards of nuclear weapons safety, security, control, and reliability” did not result in a list of new warhead surety features in the subsequent Stockpile Stewardship Plans. Indeed, the 2004-2008 plan instead declared: “The physical protection and security of nuclear weapons…remains [sic] strong….”

But after the Bush administration in 2004-2005 began lobbying Congress for authorization to begin industrial-scale production of new warheads to replace existing ones, the claim that additional warhead surety features are necessary has become a key justification. For example, STRATCOM has recently proposed consolidating four versions of the B61 bomb into one based on the need for additional surety features (see Figure).

|

New Bombs For Surety |

|

| STRATCOM has recently used hypothetical needs for additional surety features as justification for building a new version of the B61 nuclear bomb. Click to download. |

.

The slide includes some interesting assertions and assumptions underlined by a quote by Osama bin Laden saying it is a religious duty to acquire nuclear weapons to defend Muslims. The main assertion is that current U.S. nuclear weapons are “not designed to address potential for nuclear terrorism.” That certainly depends on what the “potential” is. If it means terrorists trying to force their way into a storage facility, steal a weapon, and detonate it somewhere at their choosing, the claim is almost certainly wrong. If on the other hand “potential” refers to the most worst-case scenario, where all U.S. safety and defensive efforts fail, then everything is of course possible. But worst-case scenarios are not interesting when assessing what is necessary; realistic scenarios are.

The statement that only a small percentage of the stockpile has “internal disablement features” to prevent unauthorized use probably refers to bombs and cruise missiles that happen to make up a smaller portion of the stockpile than reentry vehicles for ballistic missiles. But as the Jason report concludes, “All proposed surety features for today’s air-carried systems could be implemented through reuse LEP options.” Reentry vehicle warheads do not have these surety features, which might be a problem, but adding some does not necessarily requirement replacements, according to JASON.

The claim that all weapons lack modern surety features “to further reduce” the possibility that an accident could trigger a nuclear yield is of course true because one can always add more security features to further reduce the possibility. The sky is the limit. The issue is, however, how much is needed. In fact, once the remaining W62 warheads are retired (DOD missed the October 1, 2009, deadline), the entire stockpile will contain surety features that reduce the chance of warhead detonation due to accidents or terrorist attacks to less than one in a million.

The Skills Argument

Proponents of the RRW frequently have argued that it is necessary to build replacement warheads to keep a cadre of scientists, designers, and builders well trained and at the ready so that if sometime in the future we need new weapons we will be able to produce them. The JASON recommends improving the surveillance programs, but the language that “Continued success of the stockpile stewardship is threatened by lack of program stability, placing any LEP strategy at risk,” seems to criticize the NNSA and labs for being so fixated on building new bombs that the surveillance program has suffered.

The training argument depends on a combination of assumptions: (1) the country will eventually need new nuclear weapons and these will need to be sophisticated weapons requiring high levels of expertise, (2) the expertise needed for continuing stockpile maintenance is not adequate to maintain the expertise needed to design and build new weapons, and (3) the knowledge and skills needed to build new weapons cannot be written down and can only be preserved over the next two or three decades by keeping it alive in people. The truth of all of these assumptions depends in large part on choices we make about the future missions and requirements for nuclear weapons. None of the assumptions is of necessity true.

Recommendations

The quest for new weapons is not dead yet. Now that one main justification, reliability, has been deflated, those who want to continue to build new warheads are more likely to retreat to the second line of defense rather than surrender. We expect the NNSA, the nuclear laboratories, and the military to focus their efforts on surety technology and laboratory expertise. We need Congress (and perhaps JASON) to study the need for new surety features, and determine what level is sufficient for real-world threat levels.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Change at the United Nations

by: Alicia Godsberg

The First Committee of this year’s 64th United Nations General Assembly (GA) just wrapped up a month of meetings. The GA breaks up its work into six main committees, and the First Committee deals with disarmament and international security issues. During the month-long meetings, member states give general statements, debate on such issues as nuclear and conventional weapons, and submit draft resolutions that are then voted on at the end of the session. Comparing the statements and positions of the U.S. on certain votes from one year to the next can help gauge how an administration relates to the broader international community and multilateralism in general. Similarly, comparing how other member states talk about the U.S. and its policies can give insight into how likely states may be to support a given administration’s international priorities.

The Obama administration will certainly be looking in the near future for support on some of its new international priorities – the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference is happening in May, 2010 and the U.S. delegation will likely seek to promote certain non-proliferation measures, such as universal acceptance of the Additional Protocol and the creation of a nuclear fuel bank.[i] However, many states see these and other proposed non-proliferation measures as further restrictions on their NPT rights while the U.S. and the other NPT nuclear weapon states parties (NWS) continue to avoid adequate progress in implementing their nuclear disarmament obligation. At the same time, other states with nuclear weapons continue to develop them (and the fissile material needed for them) with no regulation at all. The United Nations (UN) is the court of world public opinion, a place where all member states have a voice. If President Obama expects to win support for his non-proliferation agenda next May, he needs to win the GA’s support by showing that the U.S. is ready to engage multilaterally again and take seriously its past commitments and the concerns of other states.

While the U.S. continued to vote “no” on certain nuclear disarmament resolutions[ii], there were some noteworthy changes in the position of the new U.S. administration during this year’s voting. One major shift away from the Bush administration’s voting through last year was a change to a “yes” vote on a resolution entitled, “Renewed determination towards the total elimination of nuclear weapons.” In fact, the U.S. also became a co-sponsor of this resolution. The change in the U.S. position on the CTBT was likely an important factor in this reversal, as the resolution “urges” states to ratify the Treaty, something Bush opposed but the Obama administration strongly supports. Similarly, the U.S. voted “yes” on the resolution entitled, “Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty,” and for the first time all five permanent members of the Security Council joined this resolution as co-sponsors.

The change in the U.S. position on the CTBT was welcomed by many delegations on the floor. Indonesia stated it would move to ratify the Treaty once the U.S. ratifies, and China has hinted at a similar position. Non-nuclear weapon states have found the past U.S. position – that no new states should have nuclear weapons programs while the U.S. continues its own without any legal restrictions on the right to test nuclear weapons – to be hypocritical. Add to this that the U.S. and other NWS have promised to work for the entry into force of the CTBT in the final documents of the 1995 and 2000 NPT Review Conferences, even using this promise as a way to get the indefinite extension of the NPT in 1995, and it may be that the CTBT is the sine qua non for the future of the NPT regime.

The U.S. delegation gave some strong signals that the Obama administration may be planning on decreasing the operational readiness of U.S. nuclear weapons (so-called “de-alerting”) in the upcoming Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). This speculation comes from remarks on the floor, when the sponsors of a resolution that had been tabled for the past two years entitled, “Decreasing the operational readiness of nuclear weapon systems” stated they would not be tabling the resolution this year.[iii] The sponsors stated that they would not be tabling the resolution because nuclear posture reviews were underway in a few countries and they hoped leaving the issue of operational readiness off the floor would, “facilitate inclusion of disarmament-compatible provisions in these upcoming reviews and help maintain a positive atmosphere for the NPT Review Conference.” Apparently the U.S. delegation pushed to leave this resolution off the floor, not wanting to vote against it again while the NPR was underway. Many took these political dealings as a sign that the Obama administration was pushing at home for a review of the operational readiness of the U.S. nuclear arsenal. Decreasing the operational readiness of U.S. nuclear forces would be a welcome change in the U.S. nuclear posture, adding time for decision-making and deliberation during a potential nuclear crisis. Such a change would also send an unambiguous signal to the international community that the U.S. was taking its nuclear disarmament obligation seriously, the perception of which is necessary for cooperation on non-proliferation goals in 2010 and beyond.

Another long-standing U.S. position apparently under review by the Obama administration relates to outer space activities. The Bush administration spoke of achieving “total space dominance” and the U.S. has been against the multilateral development of a legal regime on outer space security for 30 years. U.S. Ambassador to the CD Garold N. Larson spoke during the First Committee’s thematic debate on space issues, saying that the administration is now in the process of assessing U.S. space policy, programs, and options for international cooperation in space as part of a comprehensive review of space policy. The U.S. delegation changed its vote on the resolution, “Prevention of an arms race in outer space” from a “no” last year to an abstention this year, and did not participate in a vote on a resolution entitled, “Transparency and confidence-building measures in outer space” due to the current review of space policy. The U.S. message on outer space issues seemed to be that here too the new administration was looking to engage multilaterally instead of pursuing a unilateral agenda.

Under Secretary of State Ellen Tauscher mentioned another change in U.S. policy in her remarks to the First Committee – the support for the negotiation of an effectively verifiable fissile material cutoff treaty (FMCT)[iv]. Previously, the Bush administration had removed U.S. support for negotiating an FMCT with verification protocols, stating that such a Treaty would be impossible to verify. Without verification measures, which were part of the original Shannon Mandate[v] for the negotiation of an FMCT, many non-nuclear weapon states saw little value in negotiating the Treaty. Further, because verification was part of the original package for negotiation, the Bush administration’s change was seen as dismissive of the multilateral process and a further example of U.S. unilateral action without regard for the concerns of other countries or the value of multilateral processes. With the U.S. delegation stating that it supported negotiating an effectively verifiable FMCT as called for under the original mandate, the Obama administration again showed a marked change from its predecessor and a willingness to engage in multilateralism.

What does all this mean? President Obama stood before the world in Prague and pledged that the U.S. would work toward achieving a world free of nuclear weapons and has brought the issue of nuclear disarmament back to the forefront of international politics. President Obama recognizes that the U.S. cannot work toward this vision alone – we have security commitments to allies that need to be addressed as the U.S. makes changes to its strategic posture and policy, there are other nuclear armed countries that need to have the same goal and work toward it in a safe and verifiable manner, and there is the danger of nuclear terrorism and unsecured fissile material that needs to be addressed by the entire global community. In other words, the new administration recognizes the value in collective action to solve global problems, and at the 64th annual meeting of the UN General Assembly this year, the U.S. began putting some specific meaning behind President Obama’s general statements. With a pledge to work toward ratifying the CTBT at home and to work for other ratifications necessary for the Treaty’s entry into force, a renewed commitment to negotiating an effectively verifiable FMCT, and changes in long standing positions on outer space security and likely also on operational readiness of nuclear weapons, the Obama administration has shown the U.S. is back as a willing partner to the institutions of multilateral diplomacy. More than anything, this change – if it turns out to be genuine – will help advance President Obama’s non-proliferation goals at the upcoming NPT Review Conference. Of course the U.S. has internal battles to overcome, such as Senate ratification of the CTBT, but if promise and policy reviews are met with actions that can easily be interpreted by the rest of the world as genuine nuclear disarmament measures, President Obama has a greater chance to achieve an atmosphere of cooperation on U.S. non-proliferation goals at the upcoming NPT Review Conference in May, 2010.

[i] President Obama’s non-proliferation agenda was presented on May 5, 2009 to the United Nations by Rose Gottemoeller (Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Verification, Compliance, and Implementation) at the Third Session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2010 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference. http://www.state.gov/t/vci/rls/122672.htm

[ii] A few of the nuclear disarmament-related resolutions the US voted “no” on were: Towards a nuclear weapon free world: accelerating the implementation of nuclear disarmament commitments; Nuclear disarmament; and Follow-up to nuclear disarmament obligations agreed to at the 1995 and 200 Review Conferences of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

[iii] The US had voted “no” on this resolution the past two years, joined only by France and the UK.

[iv] Ellen Tauscher mentioned that the US “looks forward to the start of negotiations on a Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty” without further elaboration. President Obama, unlike President Bush, has made clear that his administration supports an effectively verifiable FMCT. For examples of this new policy direction, see: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/us-eu-joint-declaration-and-annexes; http://geneva.usmission.gov/2009/06/04/gottemoeller/; and http://www.state.gov/t/vci/rls/127958.htm

[v] Historical background on FMCT negotiations: http://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/legal/fmct.html

Germany and NATO’s Nuclear Dilemma

|

| Security personnel monitor nuclear weapons transport at German air base. Image: USAF |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The new German government has announced that it wants to enter talks with its NATO allies about the withdrawal of the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Germany.

The announcement coincides with the Obama administration’s ongoing Nuclear Posture Review, which is spending an unprecedented amount of time pondering the “international aspects” of to what extent nuclear weapons help assure allies of their security.

Germany and many other NATO countries apparently don’t want to be protected by U.S. forward-deployed tactical nuclear weapons, which they see as a relic of the Cold War that locks NATO in the past and prevents it’s transition to the future.

Current Deployment

The U.S. Air Force currently deploys approximately 200 B61 nuclear bombs at six bases in five NATO countries (see Table 1). The weapons are the last remnant of a vast force of more than 7,000 tactical nuclear weapons that used to clutter bases in Europe during the Cold War as a defense against the Soviet threat and the Warsaw Pact’s large conventional forces.

|

Table 1: |

|

| Approximately 200 U.S. nuclear bombs are currently deployed at six bases in five European countries. Click image to download larger table. |

.

The bombs are scattered among 87 individual aircraft shelters where they are stored in underground vaults. Although well protected, this widespread deployment contrasts normal U.S. nuclear weapons security procedures that favor consolidation at as few locations as possible.

An Air Force investigation concluded in 2008 that “most” sites in Europe did not meet U.S. security requirements. NATO officials publicly dismissed the conclusion, and a visit by a team from the U.S. government apparently found issues but nothing alarming.

Consolidation Versus Withdrawal

Rumors have circulated for several years about plans to consolidate the remaining weapons from the current six bases to one or two bases. The plans would either terminate the Cold War arrangement of non-nuclear NATO countries being assigned strike missions with U.S. nuclear weapons, or move the weapons to U.S. bases with the promise that they could be returned if necessary.

Consolidation has occurred frequently since the end of the Cold War: withdrawal from Turkish national bases Akinci and Balikesir in 1995; withdrawal from German national bases Memmingen and Norvenich in 1996; withdrawal from Greek national base Araxos in 2001; withdrawal from Ramstein in Germany in 2005 ; withdrawal from Lakenheath in England in 2006. Another round of consolidation would just be another slow step toward the inevitable: withdrawal from Europe.

Consolidation of the remaining nuclear bombs to the two U.S. southern bases at Aviano in Italy and Incirlik in Turkey would be problematic for two reasons. First, Turkey does not allow the U.S. Air Force to deploy the fighter-bombers to Incirlik that are needed to deliver the bombs if necessary, and has several times restricted U.S. deployments through Turkey into Iraq. Given that history, and apparent doubts about Turkey’s future direction, is nuclear deployment in Turkey a credible posture? Second, absent a fighter wing deployment to Incirlik, Aviano carries the overwhelming burden of conventional air operations on the southern flank of NATO, operations that are already burdened by the nuclear addendum and would further be so by a decision to consolidate the nuclear mission at the base.

An End to NATO Nuclear Strike Mission

The German policy to seek withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Büchel Air Base essentially means – if implemented – the unraveling of the NATO nuclear strike mission, whereby non-nuclear NATO countries equip and train their air forces to deliver U.S. nuclear weapons. Germany shares this mission with Belgium, Italy, and the Netherlands, while Greece and Turkey opted out in 2001.

|

Table 1: |

|

| German personnel attach a U.S. B61 nuclear bomb shape to a German Tornado fighter-bomber under supervision of U.S. personnel. As a signatory to the NPT Germany has pledged not to receive nuclear weapons, yet, as this picture illustrates, is preparing its military to do so anyway. Image: German Ministry of Defense/Der Spiegel |

.

The mission is highly controversial because these countries as signatories to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) have all pledged not to receive nuclear weapons: “undertakes not to receive the transfer from any transferor whatsoever of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices or of control over such weapons or explosive devices directly, or indirectly.” Yet that’s precisely what the NATO strike mission entails: peacetime preparations for direct transfer of nuclear weapons and control over such weapons in times of war.

The mission is clearly inconsistent with if not the letter then certainly the spirit of the NPT. The arrangement was tolerated during the Cold War but is incompatible with nonproliferation policy is the 21st century.

Real-World Security Commitments

Germany is one of the “30-plus” allies and friends that some have argued recently need to be protected by nuclear weapons to prevent them from developing their own nuclear weapons. It has even been suggested that extended deterrence necessitates equipping the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter with nuclear capability.

Yet high-level officials in both the White House and the Pentagon have already concluded that the United States no longer needs to deploy nuclear bombs in Europe to meet its security obligations to NATO. Those security obligations today have very little to do with nuclear weapons and extended deterrence is predominantly served by non-nuclear means. The limited role nuclear weapons still serve can adequately be fulfilled by long-range weapon systems just as they have been in the Pacific for 17 years. Whether the ongoing Nuclear Posture Review will reflect those views will be seen in February 2010 when the review is completed.

|

Figure 2: |

|

| The U.S. nuclear bombs were deployed in Europe to defend NATO against a conventional attack from the Warsaw Pact, a threat that has long-since disappeared. |

Regardless, Germany apparently does not want to be protected by U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe. Neither does Belgium, where the parliament unanimously has requested nuclear bombs be withdrawn. Dutch officials privately say that they see no need for the deployment either. In fact, in all of the countries where nuclear weapons are deployed, an overwhelming majority of the public favors withdrawal. Turkey – one of the countries said by some to oppose withdrawal – has the highest public support for withdrawal of any of the countries that currently store nuclear weapons. In the long run this is a serious challenges for NATO; that its nuclear posture is so clearly out of sync with public opinion.

The biggest challenge seems to be to convince Poland and Turkey that withdrawal will not undermine the U.S. security commitment. Poland is worried about Russia; Turkey about Iran. But tactical nuclear weapons were the Cold War way of addressing such concerns. What’s needed now is focused diplomacy, stewardship, and reaffirmation of non-nuclear arrangements to convince these countries that the nuclear bombs that were deployed in Europe to defend NATO against a conventional attack from the Warsaw Pact can now finally be withdrawn.

The previous two German governments also favored withdrawal but did little to push the issue. Whether the new government will be any different will be put to the test during NATO’s ongoing revision of its Strategic Concept scheduled for completion in 2010.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Clinton On Nuclear Preemption

|

|

No preemptive nuclear options, according to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

During an interview with Ekho Moskvy Radio last week, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton was asked if “the American [nuclear] doctrine incorporate[s] preemptive nuclear strikes against an aggressor?”

The Secretary’s answer was: “No, no.”

Ahem….

Secretary Clinton’s denial that U.S. nuclear doctrine incorporates preemptive strike options is at odds with numerous statements made by U.S. government officials over the past eight years, who have sought to give precisely the opposite impression; that the nuclear doctrine does indeed also contains preemptive options. An draft revision of U.S. nuclear doctrine in 2005 revealed such options.

So unless the U.S. has changed its nuclear doctrine since the Bush administration, then the Secretary’s denial is, well, at odds with the doctrine.

The confusion could of course be academic; that Secretary Clinton is under the impression that the doctrine includes preventive, no preemptive, strike options. Or perhaps she simply doesn’t know, yet believes that preemptive nuclear strike options should not be part of U.S. nuclear doctrine. It is of course important that the U.S. Secretary of State knows what U.S. nuclear policy is, since she is in charge of negotiations with Russia about the START Follow-On treaty and laying the groundwork for a subsequent and more substantial treaty and nuclear relationship.

The context of her denial was an Izvestia interview with Nikolai Patrushev, Secretary of Russia’s Security Council, about Russia’s ongoing review of its nuclear doctrine. Mr. Patrushev reportedly said: “In situations critical to national security, a nuclear strike, including a preventative one, against an aggressor is not ruled out.”

Russia’s current doctrine already allows preemptive strikes, something the Kremlin says it needs because of Russian inferior conventional forces. Whether the new revision will change or reaffirm preemptive options remains to be seen.

Background: Counterproliferation and US Nuclear Strategy (2009); Global Strike Chronology (2006); Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations (2005)

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.