Speaking at the CSIS Global Security Forum

|

By Hans M. Kristensen

Clark Murdock and John Warden with the Center for Strategic and International Studies invited me to speak today at their Global Security Forum. My co-panelists were General Larry Welch (USAF, ret.) and Morton Halperin.

The question posed to us was whether the United States should, in a proliferated world, continue to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in its national security strategy. There were different views on how much and for what reasons the role could be reduced, but at least no one could envision a need to increase the role.

CSIS will probably make the video available online soon, but in the meantime here are my prepared remarks: (more…)

FAS side events at the RevCon

by Alicia Godsberg

Yesterday FAS premiered our documentary Paths To Zero at the NPT RevCon. The screening was a great success and there was a very engaging conversation afterward between the audience and Ivan Oelrich, who was there to promote the film. As a result of some suggestions, we are hoping to translate the narration to different languages so the film can be used as an educational tool around the world. You can see Paths To Zero by following this link – we will also be putting up the individual chapters soon.

This morning I spoke at a side event at the NPT RevCon entitled “Law Versus Doctrine: Assessing US and Russian Nuclear Postures.” I was asked to give FAS’s perspective on the New START, NPR, and new Russian military doctrine. Several people asked me for my remarks, so I’m posting them below the jump. (more…)

Speaking at the NPT-Review Conference

|

| The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference is Underway in New York |

By Hans M. Kristensen

I gave two talks at the review conference of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, both on non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The first was an FAS/BASIC panel on May 10 on Prospects for a shift in NATO’s nuclear posture.

The second was a panel organized by Pax Christi on May 12 on NATO’s nuclear policy.

My prepared remarks follow below:

U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Which Way Forward?

Hans M. Kristensen

Director, Nuclear Information Project

Federation of American Scientists

Presentation to FAS/BASIC Panel on Shifting NATO’s Nuclear Posture

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference, New York, May 10, 2010I’ve been asked to talk about the status of the deployment in Europe and about the Obama administration’s policy. There are of course many other issues affecting the status and future of the deployment, but let me focus on those two here.

There are currently about 200 U.S. nuclear bombs deployed in Europe. That is a far cry from the peak of 7,300 tactical nuclear weapons that were deployed there in 1971. But comparing with the Cold War is no longer relevant; the issue is how the posture fits the security challenges of today.

The deployment currently is about as big as the entire Chinese arsenal, or nearly as much as India, Pakistan, and Israel have combined. That’s a lot for an arsenal that NATO says is not targeted or directed against anyone.

Yet for an alliance that officially emphasizes the importance of continued and widespread deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, the past two decades have been a contradiction: since 1993 when the withdrawal of ground-launched and naval weapons was completed, these “essential” bombs have been reduced from 700 to 200, the number of nuclear bases reduced from 14 to 6, and the number of countries participating in the NATO strike mission reduced from six to four.

The burden sharing principle has been reduced to a shadow of it former self: out of NATO’s 28 members, only five (18 percent) have nuclear weapons on their territory, and only four (14 percent) have the strike mission. Most recently, three of the remaining four asked NATO to formally discuss the future of the mission.

The practice of equipping and training non-nuclear NPT signatories in NATO with U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities was largely tolerated by the NPT community during the Cold War. But this arrangement is untenable in an era where the focus is on nonproliferation because it muddles the message, condones double standards, and is – plain and simple – in contradiction with the intention of the NPT. It is not a standard NATO or the United States should defend today.

So although some officials cling to Cold War arguments for maintaining U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, the reality is that it is entirely in line with post-Cold War NATO policy and actions to reduce, curtail, and phase out the nuclear mission. It’s not going the other way. So NATO’s focus should not be whether to withdraw the weapons but how.

The top of the new American administration supports a withdrawal from Europe. You might be surprised to hear that given Hillary Clinton’s statements in Tallinn last month and what some defense officials are saying inside. But those statements are part of a strategy intended to avoid triggering a backlash from some Eastern European NATO countries and Turkey that could lock NATO’s Strategic Concept into decades of nuclear status quo.

The strategy reflects that a clear priority of the Obama administration is to reassure allies and partners and repair the rift that began to open during the previous administration. The Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), the Ballistic Missile Defense Review (BMDR), and the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) all emphasize this, and all hint of changes to come in the European deployment.

The QDR states: “To reinforce U.S. commitments to our allies and partners, we will consult closely with them on new, tailored, regional deterrence architectures that combine our forward presence, relevant conventional capabilities (including missile defenses), and continued commitment to extend our nuclear deterrent. These regional architectures and new capabilities, as detailed in the Ballistic Missile Defense Review and the forthcoming Nuclear Posture Review, make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” (Emphasis added.)

The BMDR is a little more explicit, stating: “Against nuclear-armed states, regional deterrence will necessarily include a nuclear component (whether forward-deployed or not). But the role of U.S. nuclear weapons in these regional deterrence architectures can be reduced by increasing the role of missile defenses and other capabilities.” (Emphasis added.)

Although the NPR states that the presence of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe and the nuclear sharing arrangement “contribute to Alliance cohesion and provide reassurance to allies and partners who feel exposed to regional threats,” it also reminds that extended deterrence relies less and less of nuclear weapons and that the role will continue to decrease as the new, regional, deterrence architecture matures.

This new, tailored, regional deterrence architecture includes all components of U.S. military capabilities, ranging from effective missile defense, counter-WMD capabilities, conventional power-projection capabilities, and integrated command and control – all underwritten by strong political commitments. The missile defense, the NPR states explicitly, is “part of our extended deterrent and a visible demonstration of our Article 5 commitment to Europe.”

So it is important to understand that the Obama administration sees its security commitments as much more – and increasingly other – than forward deployment of nuclear bombs in Europe. In fact, the forward deployment is the least relevant today, and many U.S. officials privately make no attempt to conceal that they would like to withdraw the weapons and for NATO to move out of the Cold War.

Not only does the NPR retire the nuclear Tomahawk that supported NATO, there are subtle hints that the nuclear bombs may be withdrawn. The NPR reminds that even if the bombs were withdrawn from Europe, the United States will “retain the capability to forward-deploy U.S. nuclear weapons on tactical fighter-bombers (in the future, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter) and heavy bombers (the B-2 and B-52H).” In addition, the NPR promises, the United States will “continue to maintain and develop long-range strike capabilities that supplement U.S. forward military presence and strengthen regional deterrence.”

The subtle point, I think, is that forward deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe is not very suitable for today’s security challenges, that regional deterrence and reassurance of allies are better served by a new regional security architecture that relies less on nuclear weapons, and that there are plenty of other nuclear capabilities to provide the nuclear umbrella anyway. But none of those changes to U.S. extended deterrence capabilities will be made, the NPR promises, without close consultations with allies and partners.

So I don’t think it’s matter of if but when and how the remaining U.S. weapons will be withdrawn from Europe. The problem with additional gradual unilateral reductions is that it’s hard to cut much more without looking increasingly silly when arguing that the few that will remain are still essential for NATO.

Well aware of this dilemma, opponents of withdrawal have proposed linking further cuts to reductions in Russian tactical nuclear weapons; they know full well that such a link would means nothing will happen anytime soon.

But making further reductions conditioned on Russia reducing its non-strategic nuclear weapons seems insincere because NATO for the past two decades has been perfectly capable of and willing to reduce unilaterally without any demands on Russia. Insisting on reciprocity now, when NATO has been insisting for years that the weapons are not directed against Russia, seems like a step back to the 1980s and intended to shield the last weapons against withdrawal.

Another reason why it makes little sense to link further reductions to Russian reductions is that the improved conventional and missile defense capabilities that are required by the new, tailored, regional deterrence architecture likely will deepen Russian concerns about NATO conventional capabilities. Even though Russia’s non-strategic forces are expected to decline significantly during the next decade, this will probably increase the importance of the remaining weapons in Russian thinking even more.

Fortunately, none of this prevents a unilateral withdrawal of the remaining U.S. weapons from Europe. Indeed, it seems that the way forward is perhaps a two-step process beginning with ending the nuclear sharing mission followed by complete withdrawal a little later. Whatever the schedule is, the good news is that reducing the deployment in Europe is both consistent with NATO history and security interests.

Thank you.

U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Status and Issues

Hans M. Kristensen

Presentation toPax Christi Panel on Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Europe

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference, New York, May 12, 2010I’ve been asked to talk about the status of the deployment in Europe and what some of the implications are for NATO.

The 200 U.S. nuclear bombs currently deployed in Europe are a far cry from the peak of 7,300 tactical nuclear weapons in 1971, but comparing with the Cold War is no longer relevant; the issue is how the posture fits the security challenges of today. The current deployment is about as big as the entire Chinese arsenal, or nearly as much as India, Pakistan, and Israel have combined. That’s a lot for an arsenal that NATO says has no military mission.

Yet for an alliance that officially emphasizes the importance of continued and widespread deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, the past two decades have been somewhat of a contradiction: since 1993 when the withdrawal of ground-launched and naval weapons was completed, these “essential” bombs have been reduced from 700 to 200, the number of nuclear bases reduced from 14 to 6, and the number of countries participating in the NATO strike mission reduced from six to four countries that now appear to have serious doubts about continuing the mission. And burden sharing in NATO is actually not very widespread: out of NATO’s 28 members, only five (18 percent) have nuclear weapons on their territory, and only four of those (14 percent) have the strike mission. So nuclear burden sharing is the exception, not the rule, in NATO.

There are several issues that need to be addressed. The first is the mission. NATO is fond of saying that the forward deployment no longer has any military mission. It only serves as a symbol of the U.S. commitment to defend NATO, and without this forward symbol, so the argument goes, the U.S. security interest in Europe would weaken. Whether one agrees with this argument – and I for one believe it is absolutely nonsense – the last thing Europe should look to as the Atlantic glue is a deployment that the United States itself no longer thinks is important. There is a view forming back in Washington that it’s kind of silly for some of the NATO governments to continue to put so much emphasis on this deployment and you only have to look to the NPR report to see how much effort it makes to signal to Europe that extended deterrence and Article V do not depend on deploying nuclear bombs in Europe.

NATO is currently reviewing the nuclear mission, of which the forward deployment is a sub-issue. I think the deployment constrains the review and limits NATO’s ability think anew about the appropriate contribution of nuclear weapons to NATO security. No matter how the forward deployment has been adjusted and what one might otherwise think about the virtues of the deployment, it is at its core a Cold War posture.

Related to the mission review is the question of resources. The forward deployment requires special personnel, special equipment, special command and control, special inspections, special security arrangements, special emergency plans, special political and legal agreements, and special funding, all of which compete with conventional missions and place unnecessary burdens on people, equipment, and institutions. The weapons were withdrawn from Lakenheath and Ramstein partly because those bases needed to focus their mission on real-world contingencies. Those who insist that the deployment is still necessary need to demonstrate what the net benefit is to NATO.

The mission review is closely related to how the deployment affects relations with Russia and other potential adversaries. NATO has insisted for two decades that the weapons in Europe are not aimed at Russia or any country. That may or may not be true, but the deployment is frequently used by Russian officials as an excuse to reject constraints on their own non-strategic nuclear weapons. And Russian military planners will necessarily have to plan contingencies against potential NATO attacks with the weapons deployed in Europe. This ties NATO and Russia to a deterrence relationship that they don’t need to have, and that works against closer relations.

We now see some proposing that further reductions in the U.S. deployment should be linked to reductions in Russian non-strategic weapons. That would of course be one way to make sure the U.S. weapons are not withdrawn anytime soon, but making further reductions conditioned on Russia reducing its non-strategic nuclear weapons is misguided for several reasons. First, because NATO for the past two decades has been perfectly capable of and willing to reduce unilaterally without any demands on Russia. Second, the United States has unilaterally reduced its nonstrategic arsenal far more than Russia because these weapons are no longer seen as important to national security. Insisting on reciprocity now, when NATO has been insisting for years that the deployment is not linked to Russia, seems a step back that would give the European deployment an importance it doesn’t deserve and risk complicating prospects for Russian reductions.

Then there is the issue of safety. This is more significant than people generally think. The 200 weapons are scattered in 87 aircraft shelters at six bases in five countries. Ten years ago, the U.S. Air Force discovered that weapons maintenance procedures at the shelters under specific conditions could lead to accidents with a nuclear yield. Two years ago, the Air Force Blue Ribbon Review determined that security at the host country bases did not meet U.S. security standards. And just a few months ago, peace activists at Kleine Brogel demonstrated loudly and clearly that despite extensive security arrangements unauthorized people can get deep into a nuclear base and very close to the weapons. The widespread deployment was designed to survive a Soviet attack, but in today’s world widespread deployment is out of sync with nuclear weapons storage in the age of extreme terrorism.

Finally there is the issue of NATO’s nonproliferation standard. The practice of equipping and training non-nuclear NPT signatories in NATO with U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities was largely tolerated by the NPT community during the Cold War. But this arrangement is untenable in an era where the focus is on nonproliferation because it muddles the message, creates double standards, and is – plain and simple – in contradiction with the intention of the NPT. It is not a standard that NATO or the United States should defend today. The nuclear sharing is simply not important enough to justify this contradiction.

—

The top of the new American administration supports a withdrawal from Europe. You might be surprised to hear that given Hillary Clinton’s statements in Tallinn last month and what some defense officials are saying inside. But those statements are, I think, part of a strategy intended to avoid triggering a backlash from some Eastern European NATO countries and Turkey that could lock NATO’s Strategic Concept into another two decades of nuclear status quo.

Not only does the NPR retire the nuclear Tomahawk that supported NATO, there are subtle hints that the bombs may be withdrawn. The NPR reminds that even if the nuclear bombs were withdrawn from Europe, the United States will “retain the capability to forward-deploy U.S. nuclear weapons on tactical fighter-bombers (in the future, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter) and heavy bombers (the B-2 and B-52H).” In addition, the NPR promises, the United States will “continue to maintain and develop long-range strike capabilities that supplement U.S. forward military presence and strengthen regional deterrence.”

The subtle message to NATO, I think, is that the Obama administration does not believe that forward deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe is necessary for today’s security challenges, that regional deterrence and reassurance of allies are better served by a new regional security architecture that relies less on nuclear weapons, and that there are plenty of other nuclear capabilities to provide the nuclear umbrella to the limited extent that that is necessary. Such a posture has been in effect in Northeast Asia since 1992, and many U.S. officials privately make no attempt to conceal that they would like to withdraw the weapons from Europe too and for NATO to move on.

So I don’t think it’s matter of if but when and in what form the U.S. weapons will be withdrawn from Europe. A way forward might be a two-step process beginning with ending the nuclear sharing mission followed by complete withdrawal a little later. Whatever the schedule is, the good news is that reducing the deployment in Europe is both consistent with NATO history and security interests and the views of the new American administration.

Thank you.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

United States Discloses Size of Nuclear Weapons Stockpile

|

| The Obama administration has declassified the history and size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile, a long-held national secret. Click image to get the fact sheet. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

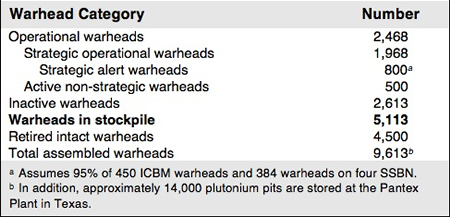

The Obama administration has formally disclosed the size of the Defense Department’s stockpile of nuclear weapons: 5,113 warheads as of September 30, 2009.

For a national secret, we’re pleased that the stockpile number is only 87 warheads off the estimate we made in February 2009. By now, the stockpile is probably down to just above 5,000 warheads.

The disclosure is a monumental step toward greater nuclear transparency that breaks with outdated Cold War nuclear secrecy and will put significant pressure on other nuclear weapon states to reciprocate.

The stockpile disclosure, along with the rapid reduction of operational deployed warheads disclosed yesterday, the Obama administration is significantly strengthening the U.S. position at the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference.

Progress toward deep nuclear cuts and eventual nuclear disarmament would have been very difficult without disclosing the inventory of nuclear weapons.

FAS and others have long advocated disclosure and argued that keeping the size of the nuclear arsenal secret serves no real national security purpose in the post-Cold War era. Now that the size of the nuclear stockpile is no longer a secret, that dismantlement numbers are no longer secret, and the number of deployed strategic warheads is no longer a secret, the United States should also disclose the total number of strategic and non-strategic weapons in the stockpile.

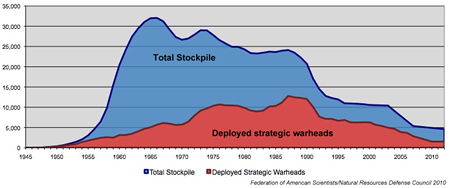

Stockpile History and Forecast

When the Bush administration took office in 2001, the stockpile included 10,526 warheads. In June 2004, the NNSA announced a decision to cut the 2001 stockpile “nearly in half” by 2012. That goal was achieved five years early in December 2007, at which point the White House announced an additional cut of 15 percent by 2012. Once these reductions are completed, the stockpile will include approximately 4,600 warheads, a force level last seen in 1956.

.

The Obama administration has not yet announced a decision to further reduce the nuclear stockpile, but there are several hints in the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) that it intends to reduce the stockpile further. The NPR states that the United States will be “significantly reducing the size of the technical hedge overall,” a reference to the thousands of non-deployed but intact warheads kept in storage for potential upload back unto missiles and bombers in case of Russia or China building up and to replace warheads that develop technical problems.

The NPR also states that the number of warheads awaiting dismantlement “will increase as weapons are removed from the stockpile under New START.” Since the New START does not require removing weapons from the stockpile – only from strategic delivery vehicles – this is also a reference to further stockpile reductions. One senior official told me that some of these reductions would be made soon.

But the “major reductions in the nuclear stockpile” promised by the NPR appear to be conditioned on “implementation of the Stockpile Stewardship Program and the nuclear infrastructure investments….” If Congress approves these investments, some “hedge” warheads can “be retired along with other stockpile reductions planned over the next decade.”

| Estimated U.S. Nuclear Weapons Inventories, 2010 |

|

| The nuclear stockpile is only a portion of the total U.S. inventory of nuclear weapons. We estimate the total number of assembled warheads is close to 9,600, probably a little less given ongoing dismantlement of retired warheads. |

.

Stockpile Warhead Categories

The stockpile contains many subcategories of warheads. There are two overall categories: active and inactive. The active category includes two subcategories: deployed warheads on missiles and bomber bases and nondeployed warheads in the “Responsive Force” for uploading in case of Russia or China building up or technical failure of deployed warheads. The inactive category includes warheads without limited-life components (such as tritium) in long-term storage.

But since the stockpile is always in a flux with warheads being moved between platforms and maintenance, each of these subcategories have numerous other categories that relate to the readiness of the warheads. According to information obtained from the government, there are four readiness state (RS) categories related to warhead functions:

RS-A: Warheads that may be used for possible wartime employment.

RS-B: Warheads intended to be used for logistical purposes (e.g., LLC exchange (LLCE), repairs, surveillance, transportation, etc.).

RS-C: Warheads intended to be used for QUART replacement.

RS-D: Warheads intended to be used for reliability replacement.

There are also five readiness state categories that relate to the warhead location an maintenance requirements:

RS-1: Active stockpile warheads intended to be located primarily on launchers or at an operational base.

RS-2: Active stockpile warheads intended to be located primarily at either an operational base or depot.

RS-3: Inactive stockpile warheads intended to be located primarily at a depot, have the LLCs removed as soon as logistically practical, require refurbishment, and require reliability and safety assessments.

RS-4: Inactive stockpile warheads intended to be located primarily at a depot, have the LLCs removed as soon as logistically practical, do NOT require refurbishment, but do require reliability and safety assessments.

RS-5: Inactive stockpile warheads intended to be located at a depot, have LCCs removed as soon as logistically practical, do NOT require refurbishment, do NOT require reliability assessments, but do require safety assessments.

Other Countries

The disclosure puts pressure of the other nuclear weapon states to reciprocate. Nuclear weapon states that do not disclose the size of their nuclear arsenals will now be seen as secretive and obstructing nuclear transparency and progress towards deep cuts and eventually disarmament. Some nuclear countries have given ballpark numbers:

The Chinese Foreign Ministry declared in a fact sheet in 2004 that, “Among the nuclear-weapon states, China. . . possesses the smallest nuclear arsenal.” That suggested fewer than 200 operationally available warheads, as declared by Britain in 1998. (See also the latest Nuclear Notebook on China.)

Britain further declared in 2007 that it would “reduce the maximum number of operationally available warheads from fewer than 200 to fewer than 160” by 2007. This suggests that a limited inventory of non-operationally available warheads exists.

France declared in 2008 that its “arsenal will include fewer than 300 nuclear warheads” following a reduction of the bombers. French president Nicolas Sarkozy claimed France was “completely transparent because it has no other weapons beside those in its operational arsenal.” Nonetheless, a small number of spares or warheads undergoing surveillance probably exist in additional to those in the “operational arsenal.” (See also the latest Nuclear Notebook on France.)

Russia has not, to my knowledge, disclosed anything about the size of its stockpile. (See latest Nuclear Notebook on Russia.)

Dismantlements

The Pentagon also released warhead dismantlement numbers back to 1995. I’ll blog later on what that means.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

2010 RevCon begins

by Alicia Godsberg

Today marked the opening of the 8th Review Conference to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons at the United Nations. The general debate began today and will continue through Thursday, with an NGO presentation to the delegates this Friday to end the week. Today’s plenary provided a few revelations from the U.S. and Indonesia that could impact the rest of the RevCon and the nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament regime in general… (more…)

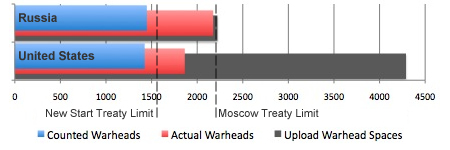

United States Moves Rapidly Toward New START Warhead Limit

|

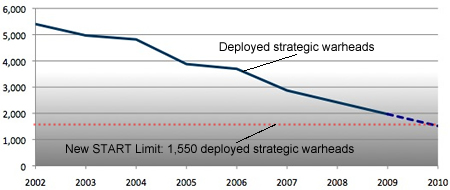

| Current pace of U.S. strategic warhead downloading could reach New START limit in 2010. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The United States appears to be moving toward early implementation of the New START treaty signed with Russian less than one month ago.

The rapid implementation is evident in the State Department’s latest fact sheet, which declares that the United States as of December 31, 2009, deployed 1,968 strategic warheads.

The New START force level of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads is not required to be reached until 2017 at the earliest. But at the current downloading rate, the United States could reach the limit before the end of this year.

Since the signing of the Moscow Treaty in 2002, the United States has removed an average of 490 warheads each year from ballistic missiles and bomber bases, for a total of approximately 3,436 warheads. There are now only a few hundred strategic warheads left at U.S. bomber bases, with most of the deployed warheads concentrated on ballistic missiles.

The last time the United States deployed less than 2,000 strategic warheads was in 1956. The peak was nearly 12,790 deployed strategic warheads in 1987.

The rapid downloading of U.S. strategic forces illustrates just how confident the military is in the capability of U.S. nuclear forces to provide a credible deterrent even at the New START level. Several thousand non-deployed warheads in storage can be loaded back onto missiles and bombers if necessary.

Even so, the rapid downloading gives the Obama administration a strong basis to argue at the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference that it is serious about moving forward on nuclear arms control.

Additional information: United States Reaches Moscow Treaty Warhead Level Early | Obama and the Nuclear War Plan

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

U.S. Defense Department sold more than $15 billion in arms in the first quarter of Fiscal Year 2009, report reveals

By Matt Schroeder

Arms sold by the Defense Department to foreign recipients totaled more than $15 billion in the first quarter of Fiscal Year 2009, according to a report obtained by the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). The quarterly report, which is dated February 2009 and is required by Section 36(a) of the Arms Export Control Act, indicates that defense articles and services sold through Defense Department Security Assistance programs from October through December 2008 were worth approximately $15.79 billion[1]. The United Arab Emirates was the largest buyer, accounting for $7 billion of sales. Saudi Arabia was a distant second with $1.87 billion, and Iraq was third with $947 million in sales. The remaining top ten recipients are listed in the table below. Sales to the top ten countries accounted for more than 80% of total sales, and nearly 89% of unclassified arms sales. These data show that a handful of countries continue to account – in dollar value terms – for the vast majority of arms sold through the US Defense Department.

| DSCA Security Assistance Sales

1 October 2008 through 31 December 2008 |

|

| Country | Total Estimated Case Value |

| United Arab Emirates | $7,017,276,438 |

| Saudi Arabia | $1,874,981,657 |

| Iraq | $947,469,859 |

| NAMO | $871,283,087 |

| Egypt | $479,317,918 |

| South Korea | $476,861,899 |

| Switzerland | $303,522,255 |

| Turkey | $258,385,648 |

| Canada | $255,271,952 |

| Colombia | $219,957,504 |

| Source: Quarterly report required under Section 36(a) of the Arms Export Control Act, February 2009. Table compiled by the Federation of American Scientists. | |

The report contains new or more detailed data on the following:

• Foreign Military Sales (FMS) Direct Credits and Grant Apportionment for FY09 as of 31 December 2008.

• Foreign Military Sales projections for FY09 as of 31 December 2008.

• Foreign Military Construction Sales, 1 October 2008 through 31 December 2008.

• Security Assistance Surveys authorized between 1 October and 31 December 2008.

• Waivers of nonrecurrent cost (NC) recoupment charges, 1 October 2008 through 31 December 2008. Note: this section contains detailed commodity data.

Much of this data is not available in other reports, or is not as detailed. For example, the Section 36(a) report contains specific data on missile sales, most of which are redacted in the most comprehensive publicly available source of data, the Annual Military Assistance Report (i.e. Section 655 report).[2] Data on sales of other commodities are also notably more specific than comparable data in the Annual Military Assistance Report. For example, the Section 36(a) report reveals that an October 2008 ammunition sale to Israel consisted of HEDP, White Star & Practice 40 mm ammunition valued at $9,897,682. Comparable data on ammunition (deliveries) in the Annual Military Assistance Report is aggregated into commodity categories that are so broad (e.g. “cartridge, 37 mm to 75 mm”) that the data are almost meaningless.

The Section 36(a) report is not a substitute for the Annual Military Assistance Report. It only includes disaggregated data[3]. on sales agreements, not actual deliveries, and only on a small sub-set of Defense Department arms sales (i.e. sales of Major Defense Equipment valued at $1 million or more). Furthermore, the data on commercial sales were withheld from public release by the Department of State [To the State Department’s credit, however, they recently posted a CSV file containing the data on commercial exports in the FY08 Section 655 report. CSV files are readily convertable into excel spreadsheets, databases, and other use-friendly research tools].

In short, the Section 36(a) report is a useful supplement to the Annual Military Assistance Report, and its narrow and specific commodity categorization is a model for other reports, many of which, like the Annual Military Assistance Report, are in dire need of an overhaul (See Eight Recommendations for Improving Transparency in US Arms Transfers).

The FAS has submitted requests for more recent editions of the Section 36(a) report, and will post them on the Strategic Security Blog and our U.S. Arms Transfers: Government Data webpage as they become available.

Click here for a pdf version of this summary.

[1] A more complete accounting of the value of arms sales in FY2009 will be released within the next couple months as part of the “supporting information” in the Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Operations. Data from previous years is available on the Federation of American Scientists’ website.

[2] It should be noted that the commodity-specific data in the Section 36(a) report is on agreements (i.e. accepted Letters of Offer and Acceptance) while the data on Defense Department exports in the Section 655 report is on arms that were delivered to the foreign recipient.

[3] By disaggregated data, we are referring to country-specific data that is disaggregated by commodity.

Second Chinese Naval Demagnetization Facility Spotted

|

| Click image for large version |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

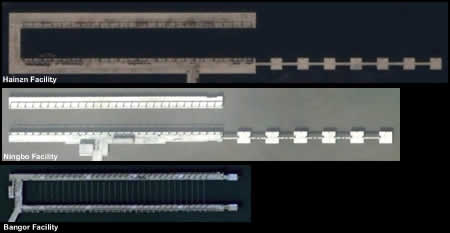

The Chinese navy has constructed what appears to be a demagnetization facility near an East Sea Fleet submarine base.

The facility is the second spotted at Chinese naval bases since 2008.

Chinese Naval Demagnetization Facilities

The new demagnetization facility is located less than 10 km from the Kilo submarine base at Maocao Nong approximately 40 km southeast of Ningbo in the Zhejiang province.

Seven Kilo-class submarines were visible at the base on January 15, 2009, nearly a third of the roughly 19 diesel-electric attack submarines that are deployed with the East Sea Fleet.

.

The East Sea Fleet facility was built between August 2007 and March 2008.

The East Sea Fleet facility is the second known Chinese demagnetization facility. In April 2008, I identified the first such facility at the South Sea Fleet base near Yulin on Hainan Island.

The South Sea Fleet facility was constructed sometime between January 2006 and February 2008.

.

The two demagnetization facilities are similar but with differences. The South Sea Fleet facility is built in a c-shape, similar to the U.S. design. The East Sea Fleet facility, which is located in a river, consists of two parallel piers, perhaps to accommodate strong currents.

The Purpose of Demagnetization

Demagnetization is conducted before deployment to remove residual magnetic fields in the metal of a vessel to make it harder to detect by other submarines and surface ships. It reduces the ship’s vulnerability to mines that are triggered by magnetic signals from metal hulls. Demagnetization apparently also can improve the speed of the vessel.

| Demagnetization of Ballistic Missile Submarine |

|

| A U.S. SSBN is prepared for demagnetization at the Kitsap Naval Submarine Base near Bangor, Washington. The U.S. Navy has such facilities on both coasts. |

.

Both submarines and surface ships are demagnetized at regular intervals.

Nuclear-powered submarines including SSBNs are based at the North Sea and South Sea Fleets, but not at the East Sea Fleet. I suspect that we’ll see construction of a North Sea Fleet demagnetization facility soon.

Some Implications

Occasional Chinese naval force operations get prominent attention in western news media, such as the recent transit between Okinawa and Miyako Island of eight destroyers and two submarines. Routine operations by U.S. forces, on the other hand, are rarely described except when they involve large exercises or when incidents occasionally expose secret options such as the Impeccable incident in 2009.

Mining of harbors and costal areas would likely be an important mission for both U.S. and Chinese attack submarines and anti-submarine warfare forces in a hypothetical military conflict between China and the United States. Chinese naval forces have, despite ongoing modernization, significant technological and operational deficiencies.

So why has China not constructed naval demagnetization facilities earlier? After all, other naval powers have done so for decades after German engineers during World War II invented the magnetic mine. According to one report, China appears to have used degaussing vessels rather than fixed facilities.

Perhaps construction now reflects acquisition of new technology, a decision that fixed facilities are more efficient than degaussing vessels, or that modifications to China’s naval strategy make demagnetization more important.

Whatever the motivation, the construction of demagnetization facilities at China’s fleets are clear tell-signs of the cat-and-mouse game that is in full swing in the region between the naval forces of China and the United States and its Asian allies.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

What’s Wrong with What’s Wrong with the Nuclear Posture Review

On Tuesday, the Secretary of Defense released the new Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). I was quite disappointed in the document, thinking it is timid and gradualist. So you can imagine how distracting it is when I am part way through writing a blog trashing the new doctrine for not going far enough that I see a flurry of articles about how the new doctrine goes way too far. So now I have to divert my valuable time to defending the NPR. (I will still finish the other blog, promise.) Some of the criticism is simply inane but most comes from not reading, or perhaps not even caring what’s in, the actual report. Still, it is probably a preview of the assaults to come.

Let’s begin with Sarah Palin, who said, “No administration in America’s history would, I think, ever have considered such a step that we just found out President Obama is supporting today. It’s kinda like getting out there on a playground, a bunch of kids, getting ready to fight, and one of the kids saying, ‘Go ahead, punch me in the face and I’m not going to retaliate. Go ahead and do what you want to with me.’”

Where does one start? Let’s begin with the big picture: Nuclear weapons are, by far, the most destructive instruments in human history, able to blow down entire cities within seconds, to kill millions at a shot, to end—quite literally—human civilization as we know it. Is a playground quarrel between a pair of schoolchildren a useful analogy? If we really wish to pursue the analogy then it would be more accurate to say that the NPR’s doctrine is equivalent to a child’s saying, “Even if you punch me, I will punch you back and perhaps beat you unconscious, I may even kill you, but I will not use a hand grenade to do it.” I believe that a no-hand-grenades-on-the-playground policy is something that many parents would endorse.

Ms. Palin is apparently assuming that by sometimes forgoing nuclear retaliation we remove all options. The NPR, in fact, states very clearly that countries that attack us with chemical or biological weapons will be met with devastating conventional attack. Moreover, the “negative security guarantees” that she is describing have long been an explicit or implicit part of U.S. nuclear doctrine.

A similar theme appeared when Sean Hannity interviewed Newt Gingrich on the NPR and other issues. In Hannity’s introduction, he says, “The Obama administration declared yesterday that the president plans to, well, depart from these precedents [of other Presidents’ nuclear policy]. Now, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton announced that the president will not use nuclear weapons against any non-nuclear state, even in the event of a chemical or biological attack.”

This is not at all what the NPR says. The NPR specifically excludes states, whether nuclear or non-nuclear, that are not meeting their Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) obligations. Without explicitly listing their names there could not be a clearer reference to Iran and North Korea. So even if Iran never actually takes the final step of building a bomb, it is on the nuclear target list because we have declared that it is not in compliance with their NPT obligations. Moreover, the NPR reserves a big caveat: if future developments in biological weapons increase their effectiveness, then the United States will revisit this policy.

Like Palin, he later says, “So what he’s [Obama] saying here is that the United States will not even in self-defense, if there’s a biological, a chemical attack or a crippling cyber attack of some kind, that we’re not going to respond.” By Mr. Hannity’s definition, the United States did not “respond” to Pearl Harbor until it bombed Hiroshima.

Mr. Gingrich responded, in part, with “…I would love to see a White House reporter ask the simple question. If there was a biological attack, which killed over a million Americans, is this president really saying we would not retaliate?” Again, “retaliate” means apparently only nuclear retaliation and such a biological attack is, in any case, explicitly exempted (p. 16).

(These comments also show the dangers of the promiscuous use of the term “weapons of mass destruction.” We now call cyber attacks and truck bombs “WMD” and conflate them with nuclear weapons that can blow down cities. This bundled term confuses more than it enlightens and should be eliminated from any discussion of national strategy.)

Mr. Hannity goes on to say, “Now, beyond that, the United States will not develop any new nuclear weapons.” I wish I could agree with his interpretation here but I cannot. The NPR says that “The United States will not develop new nuclear warheads.” It states that warheads will be maintained by Life Extension Programs, with a strong preference for refurbishment and some replacement but each warhead will be considered on a case-by-case basis and some nuclear components could be replaced with components from different warheads not necessarily in the current stockpile. By my definition, that would be a “new” warhead but not by the NPR definition. The only restriction is that nuclear components would have to have to be based on tested components but that would not, I believe, disqualify the recent Livermore Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW) design.

John Bolton writes that “The Nuclear Posture Review is deeply troubling in many respects, starting at the conceptual level with its unfounded assertion that the need for American nuclear deterrence has declined.” It is difficult to imagine what the definition of “need” is here. During the Cold War, nuclear “deterrence” included the threat of a disarming first strikes against Soviet central nuclear forces to deter a conventional attack on NATO by Soviet tank armies poised west of Berlin. The growing capability of conventional weapons is making nuclear weapons obsolete for most missions. Can anyone believe the need for nuclear deterrence has not declined? (Perhaps he means it has not declined in the last few years?) Russia and the United States still have a couple of thousand nuclear weapons pointed at each other but not because of any conflict existing today but because of momentum left over twenty years after the end of the Cold War.

Keith Payne worries that declaring that a policy of not threatening nations in compliance with the Non-Proliferation Treaty implies that the IAEA board of governors, which determines question compliance, will determine U.S. nuclear policy. As Frank Gaffney puts it, “The paramount question is: Who will determine whether a state is complying with the treaty?” Well, if he were really interested he could always ask that question and, indeed, it has been asked of the authors of the NPR and the answer is that the only thing that matters is whether the United States, not the IAEA, believes the nation in question is in compliance.

Charles Krauthammer muddles historical analysis and the current doctrine. He writes that “During the Cold War, we let the Russians know that if they dared use their huge conventional military advantage and invaded Western Europe, they risked massive U.S. nuclear retaliation.” Seeing that the lack of such attack proves that deterrence worked, he argues that we should, therefore, not change our doctrine. But the part of the doctrine relevant to his example would not change, the United States can still attack Russia, a nuclear power, with nuclear weapons and, in fact, the NPR makes clear that Russia is our largest nuclear target. In cases where the doctrine would change—forgoing attack on non-nuclear nations—the deterrence story is not so clear: Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq were not deterred even by America’s unilateral possession of nuclear weapons so his historical analysis seems at best to be irrelevant if not contradicted.

After explaining that the new doctrine would exempt NPT-compliant nations from nuclear attack, he writes “This is quite insane. It’s like saying that if a terrorist deliberately uses his car to mow down a hundred people waiting at a bus stop, the decision as to whether he gets (a) hanged or (b) 100 hours of community service hinges entirely on whether his car had passed emissions inspections.” It is the analogy that is so over the top as to be insane but it brings up the question of why the U.S. might have different responses under different circumstances. If we tone down his childish exaggeration, criminal penalties do, in fact, vary depending on circumstances. For example, many states have more severe penalties for a crime if the perpetrator had a gun, even if the gun was not used. Why? Because society has an interest in discouraging gun violence, so we make having the gun, and the potential for gun violence, cause for a greater penalty. (Now one could turn that around and say with indignant incredulity that we are giving a criminal some sort of reward for not using a gun even though he committed the very same crime rather than greater punishment for using a gun but clearly these amount to the same thing.) Most people would agree this policy makes some sense. Similarly, is it not in the interest of the United States to discourage nations from acquiring nuclear weapons? And isn’t it reasonable to create incentives? In this context, Mr. Krauthammer misrepresents the meaning of NPT compliance when he writes “If it turns out that the attacker is up to date with its latest IAEA inspections, well, it gets immunity from nuclear retaliation.” This is, of course, wrong. Iran is “up to date with its latest IAEA inspections” but it is not compliant with the NPT. “Compliant with the NPT” is a surrogate for not having a nuclear weapons program and discouraging that is in the greater, long-term interest of the United States. This sort of wild exaggeration and cavalier misrepresentation does a disservice to the national debate about a serious topic.

At least he does not make the mistake of implying that no nuclear response equals no response at all when he says, “Our response is then restricted to bullets, bombs and other conventional munitions.” I will simply remind the reader that this would describe, for example, the Second World War.

I could go on (and, alas, on) but I will close with a Washington Times column by Jeffrey T. Kuhner. His article is also filled with wild exaggeration and I will only cite one of his points. The NPR supposedly puts unacceptable limitations on the maintenance and modernization of U.S. nuclear weapons. He writes, “Moreover, the NPR stipulates that the United States will not modernize its nuclear weapons systems; rather, Washington will rely upon its aging warheads and nuclear infrastructure. China and Russia have gained a decisive advantage in pursuing innovative nuclear weapons technology.” This is flagrant misrepresentation of what is actually in the document. The NPR clearly states that weapons will be maintained and even upgraded. The only stipulation being that we will only use nuclear components with a proven test pedigree, a prudent design philosophy that most weapons designers fully support, including the directors of all three weapons labs. Moreover, the Pentagon is already in the early planning stages for new ballistic missile submarines, intercontinental ballistic missiles, and a new nuclear-capable strategic bomber. The budget for the national labs is increasing. And to his last point, Mr. Kuhner should ask any U.S. weapons designer or military nuclear specialist whether they would trade the Russian arsenal for America’s. The answer will in all cases be no. (And China? Please.)

I have presented this sample of objections to the NPR because this may be, I am afraid, representative of the “debate.” We can only hope for a more mature discussion of the issues. I strongly recommend Peter Feaver’s op-ed in the New York Times. I know Peter and he is a thoughtful, intelligent, and absolutely reasonable fellow and he does not support Obama’s NPR. But he argues that, while the NPR goes in the wrong direction, it is, on balance, a fairly modest document that, regardless of what direction it goes, does not go very far at all from past positions. I agree, which I say with some regret because I wanted it to go further.

The Nuclear Posture Review

|

| The Nuclear Posture Review enshrines nuclear disarmament as a real goal for U.S. nuclear weapons policy for the first time. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

It’s finally here! Hot off the press after a three months delay. For the first time since the end of the Cold War, the United States has published a Nuclear Posture Review report.

Granted, it’s a sanitized version, but the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) contains strong language that commits the United States to work for nonproliferation. And for the first time, the goal of elimination of nuclear weapons is enshrined into the NPR.

By incorporating a broader range of policy issues in setting the nuclear posture, the review represents a break with the Bush administration’s NPR, which was more focused on military capabilities. As such, the new NPR is more a nuclear policy review than a nuclear posture review.

At the same time, the new NPR comes across as a surprisingly cautious document that recommends curtailing the U.S. nuclear posture further in the future but for now preserves many of the key nuclear weapons force structure and policy elements of the previous administration.

Proliferators and Peer Adversaries

The truly new in this NPR is that a good portion of it has very little to do with the U.S. nuclear posture and more to do with policies intended to curtail the spread of nuclear weapons to others. As such, this NPR has a much broader horizon than previous versions. A much needed update.

The NPR illustrates how proliferation has had and continues to have a real effect on U.S. nuclear weapons policy. This is most vivid in the sections dealing with the role of nuclear weapons and regional deterrence.

In the end, however, the NPR illustrates that proliferation is a side-chapter for the sizing and characteristics of the U.S. nuclear posture, which continues to be dominated by planning against Russia and China.

As such, it is in the regional mission that most of the change that President Obama has promised may eventually emerge.

Clarifying the Nuclear Carrot

The NPR adopts a much needed simplification and clarification of the U.S. negative security assurance, an important “carrot” intended to help persuade countries not to acquire nuclear weapons. This is not a new policy by any means, but the NPR surely clarifies it:

|

| The NPR clarifies and simplifies the “nuclear carrot” |

The “United States will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapons states that are party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and in compliance with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations.”

Compare that to the Cold War version most recently repeated by the Bush administration in 2002:

The United States “will not use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states parties to the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons [NPT], except in the case of an invasion or any other attack on the United States, its territories, its armed forces or other troops, its allies or on a state toward which it has a security commitment, carried out or sustained by such a non-nuclear weapon state in association or alliance with a nuclear weapon state.”

Oy ve! There were so many exemptions buried in the old version that it was hard to understand what it meant. The new version fixes that: sign and abide by the NPT and you’re covered!

Yet as soon as you begin thinking about how this policy would be applied in the real world, questions arise.

Take Iran, for example, a non-nuclear weapon state that has signed the NPT, but is not – how to say it – on the best terms with the regime. How much in breach of its obligations under the NPT does Iran have to be before the policy kicks in? In other words, at what point would the president decide to include or exclude Iran from the list of potential adversaries he orders the military to plan nuclear strikes against?

Likewise, the negative security assurance only relates to Iran’s nuclear status. But Iran is already a target for U.S. nuclear planning because of its chemical and biological weapons capabilities. And as the NPR makes clear, U.S. nuclear weapons continue to play a role in deterring chemical and biological weapons. So could a country that has signed the NPT and abide by its obligations still be a target because it has chemical and biological weapons? In other words, which part of the policy rules?

Reducing the Role of Nuclear Weapons?

President Obama pledged in his Prague speech last year that he would “reduce the role of nuclear weapons” to “put an end to Cold War thinking,” and reaffirmed in February this year that the “Nuclear Posture Review will reduce [the] role….”

At a first glance the NPR appears to reduce the role of nuclear weapons. The document states in the executive summary that, the “fundamental role of U.S. nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attack on the United States, our allies, and partners.” (They’ll probably have to add “U.S. forces” to that list.)

While most of the debate so far has focused on what “fundamental” means, I think the important part of that statement is the word “nuclear.” Because the two previous administrations used a broader role: to deter weapons of mass destruction attacks. Weapons of mass destruction (WMD) is a much broader category that includes nuclear, biological, chemical, and radiological weapons. Nuclear strike plans against regional adversaries armed with WMD were added to the strategic war plan in 2003.

Under the section “Reducing the Role of U.S. Nuclear Weapons” the NPR lists three overall conclusions about the role:

- The United States will continue to strengthen conventional capabilities and reduce the role of nuclear weapons in deterring non-nuclear attack, with the objective of making deterrence of nuclear attack on the United States or our allies and partners the sole purpose of U.S. nuclear weapons.

- The United States would only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defense the vital interests of the United States or its allies and partners.

- The United States will not use of threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapons states that are party to the NPT and in compliance with their nuclear proliferation obligations.

The “deter nuclear attack” and pursuit of “sole purpose” is clearly new language, and they would, if implemented, constitute a roll-back of the Clinton and Bush administrations’ policy of using nuclear weapons to deter all forms of WMD.

But a little further into the document, it soon becomes clear that the actual reduction in the nuclear mission – at least for now – is rather modest, if anything at all. In fact, it’s difficult to see why under the language used in this NPR, U.S. nuclear planning would not continue pretty much the way it is now.

|

| The NPR appears to continue nuclear planning against regional adversaries with weapons of mass destruction |

The NPR explicitly rejects the adoption of a “sole purpose” policy for now, and leaves it up to future presidents to possibly change the policy in that direction. The price for a “sole purpose” policy, it seems, is more conventional weapons.

Changes in the role of nuclear weapons are much harder to see when it comes to Russia and China, where the NPR appears to continue the Bush administration’s policies. The retention of the Triad and an upload capability seem explicitly tied to those scenarios. Indeed, the NPR bluntly states that “Russia’s nuclear force will remain a significant factor in determining how much and how fast we are prepared to reduce U.S. forces.”

The first test of how and when the role of U.S. nuclear weapons might be reduced will come in a few months when president Obama issues his first presidential directive with nuclear weapons planning guidance to the military. The U.S. nuclear war plan is currently based on NSPD-14 from June 2002.

Reducing the Number of Nuclear Weapons?

President Obama also pledged in the Prague speech that he would “reduce the number of nuclear weapons” to “put an end to Cold War thinking.”

The NPR force structure analysis was the basis for the New START limits of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads and 700 deployed strategic delivery vehicles. Those limits represent a reduction compared with previous limits set by the 1991 START and 2002 Moscow Treaty.

But, as I’ve said earlier, and president Obama acknowledged in his interview with the New York Times, the New START reduces the limit for how many warheads can be deployed but not the actual number of warheads in the arsenal.

Surprisingly, the NPR does not identify how the New START limits will be achieved. Potential areas for the reductions are: a retirement of two SSBNs from the nuclear mission; a cut of about 50-100 additional Minuteman III ICBMs; conversion of some of the B-52s to conventional-only aircraft.

The NPR continues the conversion of the ICBM force to single-warhead configuration. That decision implements a decision made by the 1994 NPR, but which the Bush administration modified to allow for a few ICBMs to continue to carry multiple warheads. They were not many, though, so the reduction in warheads from finishing the conversion will be modest, although a decision to reduce the number of ICBMs further would increase the reduction.

|

| The NPR and START “will not affect the number of deployed nuclear warheads on SSBNs” |

One apparent example of the effect of not counting bomber weapons under the START ceiling is the NPR decision that even a retirement of two SSBNs “will not affect the number of deployed nuclear warheads on SSBNs.”

The NPR does not clearly direct a reduction in the size of the total nuclear weapons stockpile, which currently contains about 5,000 warheads. The Bush administration reduced the stockpile by nearly 50 percent between 2004 and 2007, and announced an additional 12 percent reduction by 2012, leaving about 4,600 warheads.

A change might come from a reduction in the inventory of non-deployed warheads. The Bush administration’s decision in 2001 to retain a Responsive Force of reserve warheads that can be loaded back onto missiles and bombers if necessary received a lot of criticism for making a mockery of arms cuts. There are currently an estimated 2,500 active warheads in that hedge. The new NPR says that the U.S. will “significantly reduce” the size of the hedge, but that the United States will retain the ability to ‘upload’ some nuclear warheads as a technical hedge against any future problems with U.S. delivery systems or warheads, or as a result of a fundamental deterioration of the security environment.” Whether the reduction will happen unconditionally or be dependent on Congressional approval of new bomb factories is unclear, but it appears to depend on construction of the new facilities.

Overall, the NPR retains the Cold War force structure of nuclear weapons deployed on a Triad of delivery vehicles and concludes that, “the current alert posture of U.S. strategic forces – with heavy bombers off full-time alert, nearly all ICBMs on alert, and a significant number of SSBNs at sea at any given time – should be retained for the present.” President Obama’s campaign pledge to “work with Russia to take U.S. and Russian ballistic missiles off hair trigger alert” appears to have been put on hold.

No doubt, retaining a Cold War posture with only modest reductions and delaying decisions about where the cuts will fall will help win crucial votes in the Senate for ratification of the New START treaty and the CTBT.

With the modest reductions recommended by this NPR, the report states that president Obama has already directed a review of future reductions of nuclear weapons. But potential reductions are conditioned on further strengthening regional deterrence, maintain strategic stability with Russia and China, provide nuclear umbrellas over allies, and building new bomb making factories.

Extended Deterrence and Nuclear Weapons

The NPR does a good job of underscoring that extended deterrence is much more than nuclear weapons. There has been an unfortunate tendency in the public debate to equate extended deterrence for NATO allies with a need to forward deploy tactical nuclear weapons in Europe.

Unfortunately, the NPR does not recommend reducing or withdrawing the approximately 200 nuclear bombs currently deployed at six bases in five European countries. Instead, it says the U.S. “will consult with our allies regarding the future basing of nuclear weapons in Europe, and is committed to making consensus decisions through NATO processes.” This is probably intended to formally leave a decision to NATO’s Strategic Review process scheduled for completion in November.

For a document that emphasizes nonproliferation and adherence to NPT obligations, the description of “NATO’s unique nuclear sharing arrangements under which non-nuclear members participate in nuclear planning and possess specially configured aircraft capable of delivering nuclear weapons” does come across as somewhat out of sync. Training and equipping non-nuclear countries to deliver nuclear weapons is not a standard the Obama administration should support.

|

| The NPR recommends production of a new nuclear fighter (F-35) with a new nuclear weapon (B61-12) |

Regardless of what NATO might decide, the NPR concludes that some of the Joint Strike Fighters (F-35) will be equipped to deliver the new B61-12 nuclear bomb to “retain the capability to forward-deploy non-strategic nuclear weapons in support of its Alliance commitments.” So even if NATO decides the weapons can be withdrawn, a tactical nuclear fighter capability will remain.

Nuclear Tomahawk sea-launched land-attack cruise missiles (TLAM/Ns) that previously supported extended deterrence of NATO and Pacific allies will be retired and the NPR correctly concludes that the remaining nuclear forces provide amble capability to both signal and deter. This brushes aside warnings from the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission and others. As for the future role of nuclear weapons in regional scenarios, the NPR states:

“U.S. nuclear weapons will play a role in the deterrence of regional states so long as those states have nuclear weapons, but the decisions taken in the NPR, BMDR, and QDR reflect the U.S. desire to increase reliance on non-nuclear means to accomplish our objectives of deterring such states and reassuring our allies and partners.”

Warhead Dismantlement and Production

There are currently about 4,500 retired nuclear warheads in queue to be dismantled. At the low dismantlement rate currently used (200-400 warheads per year) it will take more than decade to dismantle the backlog. More retired warheads will come from the decision to “significantly reduce” the hedge, further extending the timeline.

Dismantlements compete with warhead maintenance and production for limited capacity at the Pantex Plant in Texas. The NPR recommends full-rate production of the W76-1 warhead, followed by the B61-12, and possibly the W78.

These programs are described as extending the lives of existing warhead designs, although modifications can be significant. The NPR pledges that

“The United States will not develop new nuclear warheads. Life Extension Programs will use only nuclear components based on previously tested designs, and will not support new military missions or provide for new military capabilities.”

This policy leaves the door open for extensive modifications of nuclear warheads – it would even permit production of the Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW), although officials insist that program is “dead” – and the NPR states that the full range of warhead work will be considered: refurbishment of existing warheads, reuse of nuclear components from different warheads, and replacement of nuclear components.

Mindful of how controversial a decision to build replacement warheads is, the NPR assures that decisions to modify warheads “will give strong preference to options for refurbishment or reuse” rather than replacement.

Conclusion

The NPR elevates nonproliferation to the same level in U.S. nuclear policy as the nuclear weapons posture. It enshrines eventual nuclear disarmament as a central goal for U.S. nuclear weapons policy for the first time, and it sets the stage for possible future reductions in the role and numbers of nuclear weapons.

For those of us who looked forward to the NPR to clearly and significantly reduce the role and numbers of nuclear weapons, however, the report is a disappointment. President Obama has cautioned that his vision of a nuclear free world might not happen in our lifetime and the NPR shows why he might be right.

The options for how to reduce nuclear weapons are vague in the NPR but probably buried in the classified version. Some of those options, including how deep many reserve warheads will be retired, and how many ICBMs, SSBNs and bombers will be cut, will be made in the months and years ahead.

Above all, the NPR is a pragmatic policy document that combines maintaining a strong nuclear arsenal, modest reductions in nuclear weapons, nonproliferation efforts, and a vision of a world free of nuclear weapons to position the Obama administration for the April Nuclear Summit, the May NPT Review Conference, and ratification of the New START treaty and Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty.

Successful outcomes of those milestones are essential for the prospects of future reductions in the role and number of nuclear weapons, as is honest critique of when initiatives don’t go far enough.

There is a risk here, of course, that after having galvanized international hopes and expectations about dramatic changes to decisively move the world toward nuclear disarmament, the modest NPR instead will be seen by the international community as a sign that Cold Warriors managed to block much of president Obama’s vision.

Hopefully that won’t happen, but there sure is a lot of work ahead.

Further Reading: 1994 NPR | 2001 NPR

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Hardly a Jump START

Four months past a “deadline” imposed by the expiration of the old START treaty and amid much fanfare, President Obama announced that he and Russian President Medvedev had agreed on a new arms control treaty. I am not as excited as most are about the treaty and much of the following might be interpreted as raining on the parade so let me begin by saying that the negotiation of this treaty is an important step. While not as big a step as I had hoped for, it is an essential step.

Whatever the actual reductions mandated by the treaty—and they are modest—it was vital to get the United States and Russia talking about nuclear weapons again. The U.S. and Russia have at least 95% of the world’s nuclear weapons and they have to lead the world in nuclear reductions. Without this first step there cannot be a second step and there are many steps between where we are today and a world free of nuclear weapons.

The Bush administration did not simply dismiss arms control as irrelevant but argued that negotiating agreements was actually counter productive, potentially creating confrontation where it would not otherwise arise. Avoid talking and let sleeping dogs lie was the philosophy. The Bush administration had the best of both worlds, from its perspective, by negotiating the nearly meaningless Strategic Offensive Reduction Treaty, SORT, sometimes called the Moscow Treaty, that simply allowed each side to declare their plans for what they were going to do anyway and contained no verification provisions.

This treaty is different. The White House has released summaries of the main features of the treaty, not the full text, but it is clear this is a real treaty with real limits and real verification. This treaty and, more importantly, the process that produced it, gets the arms control train back on the track.

Even so, this treaty is a modest step. Hans Kristensen has described the numbers and their implications for the nuclear force structure. The treaty makes some modest reductions from the SORT limits but not large enough changes to make a qualitative difference in the nuclear standoff between the legacy forces of the two Cold War superpowers. (If anyone can explain to me why we and the Russians continue to need over a thousand nuclear bombs, each five to twenty five times more powerful than the bomb that flattened Hiroshima, pointed at each other, please send me an email. I want to know what the beef between us is that makes that seem proportionate.)

The treaty does not even approach territory that would call for a fundamental rethinking of how we deploy our nuclear weapons. As the military would say, the treaty protects the force structure. That is, we will still have a triad of bombers and both land-based and sea-based ballistic missiles, another obsolete artifact of the Cold War that dates back to fears of a disarming first strike from the Soviet Union (and inter-Service competition). Even Air Force advocacy groups such as the Mitchell Institute have considered eliminating the nuclear mission for the manned bomber and moving from a triad to a dyad of land- and sea-based missiles. In fact, the treaty contains a peculiar counting rule that increases the importance of bombers: each bomber counts only as one nuclear bomb although the B-52 can carry 20 nuclear-armed cruise missiles and the Russian bombers, for example the Backfire and Blackjack, have similar payloads. If we define corn as a type of tree, then suddenly Iowa would be covered in forests. If we define a bomber with 20 bombs as a single bomb, then suddenly we get a substantial reduction in the nuclear of weapons. (Hans discusses the numbers in more detail.) This rule reportedly resulted from Russia’s refusal to allow the necessary on-site inspections at its bomber bases but it creates an important caveat on any claim of “reductions.”

The treaty apparently does not address in any way nuclear weapon alert levels. Most of the deployed weapons both sides will have under the treaty will be continuously ready to launch within minutes. The treaty does nothing to restrict both nuclear powers to a no-first-use capability. If we wanted to reduce the threat that Russia and the U.S. pose to one another, we would be far better off to ignore the numbers of weapons but take weapons off alert so the current treaty has that exactly wrong.

Non-deployed warheads are not covered by the treaty at all as far as I can tell from the summaries. Both sides will still retain thousands of nuclear weapons not mounted on missiles and these are not even counted, much less limited, by the treaty. Apparently the verification of reserve warhead limits was too intrusive. While inspection of warhead dismantlement facilities is allowed, I cannot tell from the summary exactly what is going to be verified. I believe that the dismantlement itself will not be monitored.

One of the strengths of the treaty is that it limits actual missile warheads and provides for the verification of deployed missile warheads. In the past, there has been no way to verify warhead numbers so treaties resorted to “counting rules,” that is, those things that could be counted, namely bombers, submarines, and missile silos, were counted and each launcher was simply assumed to have a certain number of nuclear warheads associated with it. For example, if a type of missile had been tested with eight warheads, then all missiles of that type would be counted as having eight warheads regardless of the number actually mounted on top. Thus, in previous treaties, limits on the number of warheads were indirect. With this treaty, on-site inspections will allow each side to confirm though a limited number of spot-checks the number of missile warheads actually mounted on missiles.

The U.S. has wanted to keep the number of launchers high while accommodating modest reductions in the number of warheads. It has done this up to now by removing (or off-loading) warheads from multiple warhead missiles. The Russians have objected that this creates worrying breakout potential: the U.S. could reactivate reserve warheads and quickly mount them back atop the existing missiles, called uploading. In a crisis, this creates instability: if the one side sees the other uploading warheads, there is a strong incentive to strike before the process can proceed to completion. This is the argument the Russians used for limits on launchers. (Plus, of course, the Russians are short of money and want to reduce the number of their missiles anyway so better to get the Americans to come along with them.) The U.S. accepted the Russian launcher number but was unwilling to proportionately cut warheads. This creates a ratio of launchers and warheads that is not terrible but could be better. Having several warheads atop each missile makes them relatively more attractive targets of a disarming surprise first strike; this is called first strike instability. So the conflicting goals of Russia and the U.S. have forced them into trading one form of crisis instability for another. Note that, if reserve warheads were verifiably eliminated, the Russian fear of uploading would be addressed.

Given the very modest nature of the treaty, it should sail through ratification, in a normal political climate. But this is not a normal political climate. As Secretary Clinton pointed out, past arms control treaties have been ratified by the Senate by 90 votes or more. But after the passage of the health care bill, the Republicans may be unwilling to give President Obama a foreign policy success. Senator McCain has said that there will be no more cooperation in the Senate for the rest of the year. We shall see. But clearly, the Senate Republicans’ no-compromise tactics may doom treaty ratification. One thing seems certain to me: the Republicans have shown remarkable party discipline in the Senate so treaty ratification will either fail or it will succeed with close to one hundred votes. It depends on a political decision by the minority caucus.

I did not attend the White House briefing on the treaty but Hans did and reports that, according to the administration, many shortcomings of the treaty resulted from Russian resistance to intrusive verification measures. If true, this bodes ill for future dramatic achievements, for example, limits on non-deployed warheads or verifying the dismantlement of nuclear warheads. The Russians may, in part, be cautious about intrusive verification because it might reveal strategic vulnerabilities. If this is so, then the U.S. could do much to allay those fears by moving away from a counterforce capability that threatens Russian central nuclear forces every minute of the day.