New START Ratification: Seeing the Bigger Picture

|

| Morton Halperin speaks at CSIS |

By Hans M. Kristensen

Kevin Kallmyer at CSIS has an interesting recap of a recent debate between Paula DeSutter and Mort Halperin about the New START Treaty.

Ratification of the treaty is held up in Congress by a handful of Senators who (mis)use questions about, among other issues, verification to extort billions of dollars to pet nuclear modernization projects at the expense of greater U.S. interests.

During the CSIS debate, Mort Halperin provided an enlightening anecdote about how to judge whether ratification of the treaty is in the U.S. interest. It cuts to the heart of what is important and deserves a repost here:

How do you decide whether a Treaty is in the American interest in relation to verification? The question cannot be are we sure that we will have 100% confidence that we would detect the first instance of Russian cheating. The question has to take into account the limits of the Treaty, and some degree of Russian cheating, is it in our interest to have the limit in the treaty, as opposed to not constraining the Russian forces. Our notion of what is acceptable verification goes back to the Reagan administration, it actually goes back before that…because the last time the Joint Chiefs of Staff held the view that a limit was not acceptable unless it could be 100% verifiable was in 1968. At that point, the Administration was planning to put forward a proposal to the Soviet Union to ban the further production of any ballistic missiles or submarines. The Joint Chief’s position then was to we can only include things in the agreement if we could be absolutely certain there will be no Russian cheating. A navy officer came to me one day and said, “Well, we cannot include submarines in the agreement.”

I said, “Why is that?”

He said, “Because the CIA has just come out with its estimate that said the Russians could cheat on an agreement that bans Russia from building any more ballistic missile submarines.”

And I said, “What does it say?”

He said, “It says the Russians could build as many as 3 submarines and we wouldn’t detect it, and only if they build a fourth submarine could we have very high confidence of detection.”

And I said, “How many submarines doe we have now?”

He said, “41.”I said, “How many submarines do we plan to have 10 years from now.”

He said “41.”

I said, “How many submarines do the Russians have now?”

He said, “I think one.”

I said, “How many do we think they will have in 10 years from now.”

He said, “50.”

I said, “So, you prefer a world where we do not limit this and the Russians have 50 submarines and we have 41, to a world where we have 41, and the Russians have [4] until we can be sure we detect the [5th] submarine.”

And he said, “That’s right, the principle is that you do not include something in an agreement that cannot be verified.”

I looked at him and said, “Well, I think I’m going to win this fight…and I did.”

And the Joint Chiefs changed their position then, to what is clearly the correct position. You ask yourself about each limit, including the warhead limit in this treaty; is it in our interest to have this limit, recognizing that there obviously could be some amount of Russian cheating. The question is how much Russian cheating can there be before we detect it, and the question is what is the strategic significance of that cheating. We have seen no such analysis, because no such analysis that could be presented would be the slightest bit persuasive. The fact is that with the margin of deterrence we have to deter a Russian attack, that the margins of cheating the Russians can do is simply insignificant to the security to the United States.

Check out the full debate at the CSIS web site.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

NATO Strategic Concept: One Step Forward and a Half Step Back

|

| NATO General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen presents the alliance’s new Strategic Concept |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The new Strategic Concept adopted today by NATO represents one step forward and a half step backward for the alliance’s nuclear weapons policy.

The forward-leaning part of the nuclear policy pledges to actively try to create the conditions for further reducing the number of and reliance on nuclear weapons, recommits to the ultimate goal of nuclear disarmament, and reaffirms that circumstances in which the alliance could contemplate using its nuclear weapons are “extremely remote.”

But the strategy fails to present any steps that reduce the number of or reliance on nuclear weapons. As such, the new Strategic Concept – Active Engagement, Modern Defence – falls short of the Obama administration’s recent Nuclear Posture Review.

Even so, there are important changes in the document that hint of things to come.

The Role of Nuclear Weapons

The new Strategic Concept does not explicitly reduce the role of NATO’s nuclear weapons. Instead, it echoes the Obama administration’s formulation that “as long as nuclear weapons exist,” NATO will remain a nuclear alliance.

And the formulation in the 1999 Strategic Concept that “NATO’s nuclear forces no longer target any country” is gone from the new document. Instead, it states that NATO “does not consider any country to be its adversary.”

Overall, the 2010 document is far less explicit than the 1999 document about what the role of nuclear weapons is. The previous document explicitly described the role “to preserve peace and prevent coercion and war of any kind…by ensuring uncertainty in the mind of any aggressor about the nature of the Allies’ response to military aggression,” and “demonstrate that aggression of any kind is not a rational option.”

The new document, in contrast, describes the role of nuclear weapons in very general terms, essentially with no specifics, and as part of an overall mix of nuclear and conventional capabilities.

Gone is the previous language about U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in Europe providing an essential political and military link between Europe and North America, or that sub-strategic forces provide a link with strategic forces.

Instead, the document states that it is the strategic forces of the United States, in particular, and to some extent Britain and France, that provide the “supreme guarantee of the security of the Alliance”.

US Nuclear Forces in Europe

Combined, these significant changes could be seen as hints of an attempt to lessen the importance the alliance attributes to having U.S. tactical nuclear weapons forward deployed in Europe.

To be sure, the document still contains what appears to be a commitment to some form of U.S. nuclear presence in Europe, by committing to “the broadest possible participation of Allies in collective defence planning on nuclear roles, in peacetime basing of nuclear forces, and in command, control and consultation arrangements.” (Emphasis added)

|

But this is vague language compared with the 1999 document. It could simply be met by Allies taking part in Nuclear Planning Group meetings, deployment of some U.S. dual-capable aircraft in Europe but without weapons, and Allies continuing to be part of the decision making process for potential use of nuclear weapons.

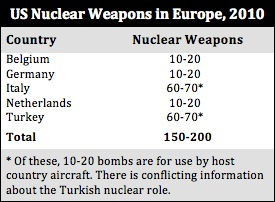

The number of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe today is down to 150-200 B61 bombs deployed at six bases in five countries (see table).

The Role of Russia

In the years between the 1999 and 2010, NATO unilaterally reduced the number of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons deployed in Europe by more than half, from 480 to 150-200 B61 bombs. The 1999 Strategic Concept did not mention Russia at all as a factor for sizing the U.S. deployment.

The new Strategic Concept, in contrast, returns Russia to a central position for how the Alliance sizes the number of U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

“In any future reductions,” NATO declares, “our aim should be to seek Russian agreements to increase transparency on its nuclear weapons in Europe and relocate these weapons away from the territory of NATO members.”

Moreover, “Any further steps must take into account the disparity with the greater Russian stockpiles of short-range nuclear weapons.”

While seeking to achieve reductions in Russian tactical nuclear weapons is important – it has more than 5,000 of them, formally linking the U.S. deployment in Europe to Russia seems to contradict the policy of the past two decades that the U.S. weapons in Europe are not directed against Russia. And NATO has repeatedly made unilateral reductions without demanding Russian reductions. Indeed, the new Strategic Concept declares that “NATO poses no threat to Russia,” and that the Alliance “does not consider any country to be its adversary.”

So to begin now to argue that the size of the U.S. arsenal in Europe is linked to Russia after all resembles the Cold War policy when NATO looked to Russia for sizing the U.S. arsenal in Europe.

Moreover, Russia’s tactical nuclear weapons posture is less tied to the U.S. nuclear posture in Europe and more to Russia’s perception of countering NATO’s superior conventional forces and defending the long border with China. Since those factors determine the size of the large Russian tactical nuclear weapons arsenal, it is hard to see why Moscow would agree to reduce its tactical nuclear weapons in return for reductions of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in Europe.

The Future

The changes in the new Strategic Concept are many and important. The language could hint that NATO may be preparing the ground for the withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe. But the way forward is muddled with preconditions on Russian reductions.

A joint communiqué from the Lisbon Summit might make things clearer tomorrow but it will require a new deterrence review in 2011 for NATO to translate what the Strategic Concept means for NATO’s nuclear posture.

Conditioning future reductions on Russia could be a roadblock, so hopefully the vague “aim to seek” and “taking into account” formulations don’t imply tit-for-tat reciprocity. The success of the unilateral withdrawals in the early 1990s suggests that a unilateral withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe would be more effective in stimulating a Russian response.

The Obama administration sees the emergence of a “new, tailored, regional deterrence architecture” that “make[s] possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” The new Strategic Concept seems to agree, so hopefully the Obama administration can now become more assertive in pushing for a withdrawal of the last U.S. tactical nuclear weapons from Europe so it can focus on an agreement to reduce U.S. and Russian tactical nuclear weapons in general.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Delay: Gambling With National and International Security

|

| A few Senators are preventing US inspectors from verifying the status of Russian nuclear weapons. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The ability of a few Senators to delay ratification of the New START treaty is gambling with national and international security.

At home the delay is depriving the U.S. intelligence community important information about the status and operations of Russian strategic nuclear forces. And abroad the delay is creating doubts about the U.S. resolve to reduce the number and role of nuclear weapons, doubts that could undermine efforts to limit proliferation.

New START may not be the most groundbreaking treaty ever, but it is a vital first step in moving U.S.-Russian relations forward and paving the way for additional nuclear reductions and nonproliferation efforts. Essentially all current and former officials and experts recommend verification of New START, and after more than 20 hearings and nearly 1,000 detailed questions answered it is time for the Senate to ratify the treaty.

Important Inspections

Ratification would set in motion a wide range of data exchange and on-site inspection activities. By delaying ratification, the Senators are depriving the U.S. intelligence community important information about Russian nuclear forces. Apart from monitoring how Russian strategic nuclear forces are evolving and operating, the information is important to avoid worst-case threat assessments that can negatively affect U.S.-Russian relations.

It has now been 348 days since the last U.S. inspection team left Russia.

During the 15 years the START Treaty was in effect between 1994 and 2009, U.S. teams conducted 659 inspections of Russian nuclear weapons facilities; Russian conducted 481 inspections of U.S. facilities.

The last U.S. on-site inspection took place on November 18-19, 2009, at an SS-25 mobile missile base near Teykovo, approximately 130 miles (210 km) northeast of Moscow.

.

That inspection had special meaning because the SS-25 is being phased out from this area and replaced with the new SS-27. While each SS-25 is equipped with one warhead, the SS-27 comes in two versions: one with a single warhead and one with three warheads. The U.S. intelligence community calls the latter the SS-27 Mod 2, while the Kremlin named it RS-24 so as to avoid conflict with the now expired START treaty.

One of the four bases at Teykovo has already been equipped with the SS-27 Mod 2, two still have the SS-25, while the fourth base has been emptied and might be converting to the newer missile. Within the next decade, all four bases may be equipped with the SS-27 Mod 2.

The Russians chose Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri for their final on-site inspection in the United States. That inspection took place on December 1-2, 2009, just two days before the treaty expired.

| B-2 of the 509th Bomb Wing over Whiteman AFB |

|

| Russia chose the B-2 base at Whiteman Air Force Base as its final inspection in the United States under the now expired START treaty. |

.

The Nonproliferation Gamble

From the outset, the Obama administration appears to have seen Russia as the main potential obstacle to the treaty, rather than the U.S. Senate. Absent a strategy to secure the votes for ratification early on, the tables have now turned; with the White House desperate to secure ratification, a few Senators who still see Russia through Cold War lenses have effectively managed to use hearings and voting rules to extort concessions (read: money) from the administration to modernize the nuclear weapons production complex and delivery systems.

| Senator Jon Kyl |

|

| A few senators, most prominently Senator Jon Kyl (R-Arizona), have managed to delay ratification of the New START treaty. |

.

The administration quickly agreed to boost the FY 2011 budget for the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) well above the FY 2010 level. But that didn’t satisfy the Senators. So when Congress was unable to approve the budget before the mid-term election, the administration agreed that a Continuing Resolution (CR) designed to keep federal agencies operating at FY2010 budget levels through December 3rd would include an exemption for NNSA’s weapons program to fund the agency at the higher FY 2011 budget request – about $7 billion or an additional $625 million. But since the provisions in the defense appropriations bill and report don’t apply to the CR, the appropriators have lost control of how the funds are used; Congress is basically providing NNSA with a blank check to spend the $7 billion.

In addition, in an effort to buy the Senators’ votes for ratification during the “lame duck” session before the new Congress begins, the administration has offered $600 million more for the FY 2012 NNSA budget above FY 2011 levels, as well as an additional $3.6 billion spread out over FY 2013-2016.

Altogether, in a nuclear spending spree that would have been inconceivable during the Bush administration, the Obama administration plans to spend well over $180 billion to modernize nuclear weapons delivery systems and production facilities over the next decade.

There is a real risk that in the coming years, this modernization could backfire and undermine the second pillar of U.S. nuclear policy: strengthening nonproliferation.

The reason is simple: U.S. nonproliferation efforts dependent upon international support, but if the international community sees the increased nuclear modernizations as contradicting the U.S. pledge to work toward nuclear disarmament, some countries may well decide not to support the administration’s nonproliferation agenda.

This risk could be compounded later this week if NATO approves a new Strategic Concept that reaffirms the importance of nuclear weapons – and fails to order the withdrawal of the remaining tactical nuclear weapons from Europe.

The Senate needs to demonstrate that it understands that the Cold War is over and that it cares more about national and international security than politics by ratifying the New START treaty before Christmas. And the administration must be careful to balance its nuclear modernization plans with the need to sustain the vision of nuclear disarmament that so inspired the international community just 18 months ago.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

START in a Lame Duck

|

| The Senate should vote on the New START during the “lame duck” session. |

The New START arms control treaty, negotiated between the United States and Russia and signed by the presidents of both countries last April, is awaiting ratification by the United States Senate. Objections to the treaty rest primarily upon misunderstandings or misrepresentation. In addition, though, some opponents of the treaty are arguing that, whether one supports or opposes the treaty, it is improper for the Senate to vote on the treaty during the post-election or “lame duck” session of Congress. But there is neither a constitutional nor a commonsense reason to delay a vote.

Some of us who hope to dramatically and rapidly reduce the salience of nuclear weapons were disappointed that the treaty was rather modest, but it clearly moves in the right direction. This treaty is not a radical departure from past treaties, it is not even a post-Cold War treaty; it is an extrapolation of the Cold War SALT and START treaties stretching back to the days of the Soviet Union. Given the current strategic security environment, neither Richard Nixon, nor Ronald Reagan, nor George H. W. Bush would blink an eye at this treaty. (more…)

Scrapping the Unsafe Nuke

|

| The author next to a B53 shape outside the Atomic Museum in Albuquerque, NM. This open-air display is located at these coordinates: 35° 3’54.78″N, 106°32’7.09″W. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The National Nuclear Surety Administration (NNSA) has announced that it has authorized the Pantex Plant in Texas to begin dismantlement of the B53 nuclear bomb.

Everything about the B53 is big: it weighs as much as a minivan and has an explosive yield of nine megatons, equivalent to 600 Hiroshima bombs.

Initially designed to annihilate Soviet cities, the large yield later earned the B53 one of the longest careers in the U.S. nuclear arsenal as a nuclear shovel; literally to dig up Soviet underground command bunkers. The mission was seen as so important that the B53 was even saved from an earlier retirement and allowed to serve for another decade until 1997 even though the Pentagon knew it had serious safety and security flaws.

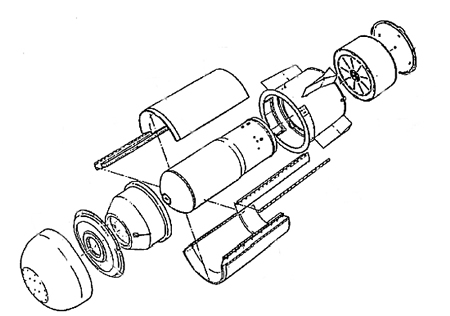

Characteristics

The B53 is a two-stage thermonuclear bomb with a nuclear yield of nine megatons. At 148 inches (3.8 m) long and 50 inches (1.3 m) in diameter, the whole bomb weighs approximately 8,850 pounds (4 tons).

| “Exploded” B53 Bomb Components |

|

| The behemoth B53 weighed as much as a minivan and had a yield of nine megatons. It’s mission was to destroy deeply buried facilities with enormous radioactive fallout as a consequence. Drawing obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. |

.

Approximately 340 B53s of two versions (Mod 0 and Mod 1) were produced between 1962 and 1965. The bomb weighs as much as a minivan and could only be delivered by the B-52 bomber, each of which could carry two of the behemoth weapons.

The B53 only had a laydown option and was timer armed and fired so the delivery bomber had time to get away before detonation.

The large yield could destroy facilities buried 750 feet (230 meters) underground.

History

The B53 was on continuous airborne alert onboard B-52 bombers between 1962 and 1968, when about a dozen bombers were kept in the air 24 hours a day loaded with fully ready nuclear weapons to ensure the Soviet Union couldn’t disarm the United States in a first strike. After the airborne alert was canceled, the B53 was on ground-alert until retirement first began in 1987.

But that retirement coincided with the retirement of the high-yield Titan II ICBM in June 1987, another nine-megaton weapon used to hold Soviet underground facilities at risk. So the Joint Chiefs of Staff in March 1987 directed Strategic Air Command to return B53s to B-52 bombers on alert:

“In order to hold selected deeply targets at risk in all scenarios, a day-to-day alert capability is required. The current capability will be lost when the last Titan II ICBM is deactivated on Jun [sic] 87. Therefore, a B53 ALFA Alert capability must be developed as soon as possible.”

One of these targets probably was the nuclear command and control center under Kosvinsky Mountain in central Russia.

The B53 stayed on alert until 1991, when the bomber ground alert was finally cancelled.

Unsafe but Important

The B53 was not built with modern safety features, although it was one-point safe (detonation of any one chemical high explosives would not produce a nuclear yield). And over its many years in the stockpile some basic safety design features were added to the weapon to enhance nuclear explosive safety, for example to prevent accidental electrical energy from lightning to trigger the weapon. But the B53 did not have Enhanced Nuclear Detonation Safety (ENDS), Insensitive High Explosive (IHE), Fire-Resistant Pit (FRP), Protective Action Link (PAL), or Command Disable (CD).

The government had known about safety issues in the B53 “for twenty years,” former Sandia Director Paul Robinson later stated. But holding a few high-priority Soviet underground targets at risk was considered so important that safety requirements were waived, allowing the B53 to remain in the stockpile.

Legislation passed by Congress in 1992 specified three modern safety features that should be incorporated into all U.S. nuclear warheads: ENDS; IHE; FRP. The nuclear weapons stockpile plan from early 1993 directed the retirement of all warheads that lacked ENDS.

So in July 1993, then DOE Deputy Assistant Secretary for Military Application (Defense Programs) Winford Ellis “strongly recommended” to Harold Smith, the Assistant to the Secretary of Defense (Atomic Energy), that the B53 bomb be retired “at the earliest possible date.” The weapon “has no assured level of nuclear safety in a broad range of multiple abnormal environments.”

In addition to safety issues, the B-52 bomber was no longer considered capable of penetrating the most advanced air defense systems, so U.S. Strategic Command wanted a modern nuclear bunker-buster capability on the B-2 stealth bomber.

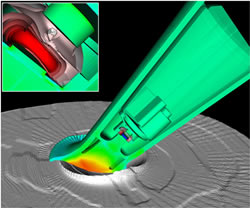

| The B53 Replacement: The B61-11 |

|

| The B-2 delivered B61-11 nuclear earth-penetrator (above, with spin motors in drop test) replaced the B-52 delivered B53 in 1997, improving the ability to penetrate modern air defenses and attack deeply buried facilities such as Russian command bunkers. |

.

The September 1994 NPR recommended replacing the B53 with a new bunker-buster, which eventually became the B61-11, a modified version of the B61-7 with earth-penetrating capability and increased yield. As the B61-11 entered the stockpile in 1997 on the B-2 bomber, the B53 was finally retired for the second time.

Only one other warhead, the W62 on the Minuteman III ICBM, had worse surety features than the B53. The W62 was allowed to remain in service until 2009.

That Good Old Nuclear Secrecy

Now, don’t hold your breath to be told how many B53s are being dismantled. After the Obama administration in May declassified the entire history of the size of the nuclear weapons stockpile as well as the number of warheads dismantled each year, mysterious national security now requires the government to keep secret the number of B53s to be dismantled at Pantex. Some things never change.

Excessive secrecy aside, the number of B53s to be dismantled is approximately 36.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear De-Alerting Panel at the United Nations

|

| Panelists from left: Hans M. Kristensen (FAS), John Hallam (Nuclear Flashpoint), Dell Higgie (New Zealand Ambassador for Disarmament), Christian Schoenenberger (Swiss UN Mission), Col Valery Yarynich (Institute of the United States and Canada, Russian Academy of Sciences), Stephen Starr (Physicians for Social Responsibility) |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

On Wednesday, October 13th, I gave a briefing at the United Nations on the status of U.S. and Russian nuclear forces in the context of the interesting article Safe and Smaller recently published in Foreign Affairs.

One of the co-authors, Valery Yarynich, a retired colonel who served at the Center for Operational and Strategic Studies of the Russian General Staff, spoke about the main conclusion of the article: that is possible to significantly reduce the alert-level of U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear weapons without creating risks of crisis instability.

That conclusion directly contradicts the Obama administration’s recently completed Nuclear Posture Review, which rejected a reduction of the alert rates for land- and sea-based ballistic missiles because, “such steps could reduce crisis stability by giving an adversary the incentive to attack before ‘re-alerting’ was complete.”

The panel coincided with the meeting of the First Committee of the General Assembly, during which New Zealand submitted a resolution on decreasing the operational readiness of nuclear weapons.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Scrapping the Safe Nuke?

|

| The compact W84 warhead (left) was designed to be delivered by the ground-launched cruise missile. Some 380 W84s are awaiting dismantlement – or reuse. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) recently announced that disassembly of the W84 warhead has begun at the Pantex Plant in Texas.

This marks the final phase for a group of 400 warheads that were at the center of the Cold War in Europe as part of NATO’s Double Track Decision in 1979 to deploy intermediate-range weapons in response to Soviet deployments. The W84 armed the Ground-Launched Cruise Missile (GLCM) that was eliminated by the 1987 INF Treaty.

Redundant before production was completed in 1988, the W84 spent the rest of its life on shelves in military warehouses in the United States. The NNSA press release states that the W84 “remains in the inactive stockpile,” but the weapon was formally retired in 2006-2007, and neither the DOE budget request for FY2011 nor the latest Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan (SSMP) lists the W84 as part of the DOD stockpile. NNSA told me they would correct the press release.

The W84 was and probably is the safest of all the warhead types produced by the United States. It is equipped with more safety and security (surety) features than any other warhead: Insensitive High Explosives; Fire Resistant Pit; Enhanced Nuclear Detonation Safety (ENDS/EEI) with detonator stronglinks; Command Disable; and the most advanced Permissive Action Link (PAL G).

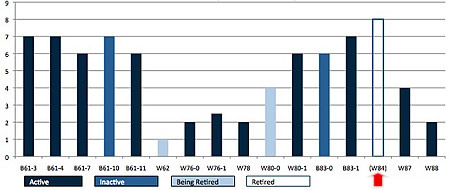

| Relative Surety of U.S. Nuclear Warheads |

|

| The W84 is the equipped with more safety and security features (surety combined) than any other warhead in the U.S. stockpile. The W84 was retired in 2006-2007. |

.

It may seem as an irony that the safest warhead is being scrapped at a time when the administration is asking Congress to authorize billions of dollars to increase the safety and security of the remaining warheads in the stockpile. But there is a twist.

A few years ago, dismantlement at Pantex would have meant the end for the W84. But the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review decided that the “full range of LEP approaches will be considered: refurbishment of existing warheads, reuse of nuclear components from different warheads, and replacement of nuclear components.”

As a result, the W84 – and all other retired warheads currently in line for dismantlement – “will be assessed for reuse applications as appropriate,” NNSA told me.

Therefore, they said, “it would be premature to assume that components from the W84 operations will be for immediate disposal (scrapping).”

So who knows, one day the W84 – or components of it – might be deployed once again as part of a replacement warhead.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Rasmussen: Lay Short-Range Nuclear Weapons Thinking to Rest

By Hans M. Kristensen

The next steps in European security should include additional reductions in the number short-range nuclear weapons in Europe, according to a video statement issued by NATO General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen:

“We also have to make progress sooner or later in our efforts to reduce the number of short-range nuclear weapons in Europe. NATO has cut the number of short-range nuclear weapons in Europe by over 90 percent. But there are still thousands of short-range nuclear weapons left over from the Cold War and most of them are in Russia. NATO is not threatening Russia and Russia is not threatening NATO. Time has come to lay this Cold War thinking to rest and focus on the common threats we face from outside: terrorism, extremism, narcotics, proliferation of missiles, weapons of mass destruction, side by side, and piracy. We can make progress of all three tracks – missile defense, conventional forces, and nuclear weapons – and create a secure Europe. It is time to stop spending our time and resources watching each other and look outward at how to reinforce our common security hope.”

That vision appears similar to the “new regional deterrence architecture” that several recent Obama administration reviews concluded would permit a reduction of the role of nuclear weapons. With that in mind, and Rasmussen’s conclusion that “Russia is not threatening NATO” and that the “time has come to lay this Cold War thinking to rest,” it should be relatively straightforward for him to recommend a withdrawal of the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe.

Unfortunately, rather than taking the initiative to complete the withdrawal of U.S. short-range nuclear weapons from Europe – a process that have been underway now for two decades but held up by Cold War thinking and NATO bureaucrats, Rasmussen instead appears to weave the future of the weapons in Europe into a web of new conditions that must be met first. In a speech at the Aspen Institute in Rome, Rasmussen described his three-track vision of collaborating with Russia on missile defenses, conventional weapons negotiations, and reducing short-range nuclear weapons:

“I think we have before us three tracks, which, if we follow them, will lead to a different, better and safer Europe: where we don’t look over our shoulders for someone else’s tanks or fighters; where missile defences bind us together, and protect us too; and where steadily, the number of short-range nuclear weapons on the continent is going down.”

Nuclear reductions appear to be the third track, after missile defense collaboration and conventional arms negotiations with Russia. For two decades, NATO has insisted the U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe have no military mission and that they’re not linked to Russia. The alliance has repeatedly been capable of and willing to make unilateral reductions – even complete withdrawal from Greece and the United Kingdom – without conditions or demanding reductions in Russian short-range nuclear weapons.

So why start linking reductions to Russia now?

Doing so seems to turn back the clock to the Cold War when NATO looked to Russia’s military forces to determine its nuclear posture in Europe. If the conclusion that “Russia is not threatening NATO” is more than words, then why make a three-track vision that assumes that Russia’s short-range nuclear weapons threaten NATO? Because the short-range weapons are not covered by any arms control regime, Rasmussen explains, the lack of transparency “makes allies cautious.”

There are certainly many good reasons to want to try to secure and reduce Russian short-range nuclear weapons. But if Russia is not threatening NATO, then Russian and U.S. short-range nuclear weapons should be addressed as a generic arms control challenge and not one that is linked to whether the U.S. has nuclear weapons in Europe or not.

| Did They Lay Cold War Nuclear Thinking to Rest? |

|

| During his meeting with Italian defense minister Ignazio La Russa, did Rasmussen discuss the possibility of a withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe, including Italy, or just the threat of Russian short-range nuclear weapons? |

.

If NATO unilaterally withdrew the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe, what would happen?

Would Russia decide that it didn’t have to reduce its short-range nuclear weapons? Hardly, since those forces seem to be more tied to Russia’s perception of NATO’s conventional superiority and a need to safeguard the long border with China. Besides, many of the Russian weapons are so old that they’re likely to be retired soon.

Would Russia get an advantage in a hypothetical crisis with NATO? Hardly, since it would require that Russia ignores NATO’s conventional superiority and U.S., British, and French long-range nuclear forces.

Would Russia decide that it had more freedom to deploy conventional forces on NATO periphery? Hardly, since such decisions seem to be made regardless of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe.

Would Iran somehow conclude that it could take additional steps acquiring nuclear weapons capability? Hardly, since its security assessment is not affected by whether the U.S. deploys nuclear weapons in Europe and it would still face serious consequences if it developed – certainly if it used – nuclear weapons.

Would Turkey and Eastern European NATO members conclude that NATO’s security guarantee was no longer credible and begin building nuclear weapons? Hardly, since their assurance is much more determined by conventional forces and political relations, and, to the limited extent nuclear forces play any role, the long-range forces of the United States, Britain, and France, would be more than adequate for any realistic scenario. Moreover, any NATO member country that began to develop nuclear weapons would face enormous pressure from the international community and from within NATO itself.

To the extent that some officials in some eastern European NATO countries feel uneasy about the inevitable withdrawal of U.S. short-range nuclear weapons from Europe, the obvious job for the Obama administration and the majority of NATO countries that favor a withdrawal is a concerted effort to educate those officials about the significant conventional and long-range nuclear capabilities that will continue to provide security when the short-range weapons are withdrawn. The revised Strategic Concept to be adopted at the Lisbon Summit in November is expected to reaffirm a role for nuclear weapons in NATO.

Rasmussen would do more for European security if he tried to decouple the future of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe from the need to reduce and eventually eliminate short-range nuclear weapons in general. Doing so would indeed be to “lay this Cold War thinking to rest.”

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Report reveals $11.7 billion in arms deliveries in 2009, but sheds little light on individual exports

Deliveries of arms through the Defense Department’s Foreign Military Sales Program (FMS) increased by nearly $700 million in fiscal year (FY) 2009, according to the most recent edition of the Annual Military Assistance Report. The report, which is often referred to as the “Section 655 Report,” is compiled each year by the Defense Department and the State Department. The Defense Department’s contributions to the annual report are acquired by the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) through annual requests under the Freedom of Information Act. While the report is useful for tracking trends in the overall value of certain types of arms sales to specific countries, it provides very little detailed information on individual exports, or exports arranged through non-traditional US military aid programs. Changing the way the data is aggregated and presented, and expanding the report to include data on all arms exports, would make the report more useful and improve congressional and public understanding of US arms exports.

Click here to read the full article.

Nuclear Commanders Endorse New START

|

| The men behind a decade and a half of U.S. strategic nuclear planning say the New START treaty will enhance American national security. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Seven former commanders of U.S. nuclear strategic planning have endorsed the New START treaty and recommended early ratification by the U.S. Senate.

In a letter sent to Senator Carl Levin and John McCain of the Senate Armed Services Committee and Senators John Kerry and Richard Lugar of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the retired nuclear commanders conclude that the treaty “will enhance American national security in several important ways.”

The list includes four former commanders of U.S. Strategic Air Command (SAC) and four former commanders of U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) – one served both as SAC and STRATCOM commander – who were responsible for U.S. strategic nuclear war planning and for executing the strategic war plan during the last phases of the Cold War and until as recently as 2004.

In doing so, the nuclear commanders – who certainly can’t be accused of being peaceniks – effectively pull the rug under the feet of the small number of conservative Senators who have held the treaty and U.S. nuclear policy hostage with a barrage of nitpicking and frivolous questions and claims about weakening U.S. national security interests.

The endorsement by the former nuclear commanders adds to the extensive list of current and former military and civilian leaders who have recommended ratification of the New START treaty. In fact, it is hard to find any credible leader who does not support ratification.

It’s time to end the show and do what’s right: ratify the New START treaty!

REPRODUCTION OF LETTER:

July 14, 2010

Senator Carl Levin, Chairman, Armed Services Committee

Senator John McCain, Ranking Member, Senate Armed Services CommitteeSenator John F. Kerry, Chairman, Senate Foreign Relations Committee

Senator Richard G. Lugar, Ranking Member, Senate Foreign Relations CommitteeGentlemen:

As former commanders of Strategic Air Command and U.S. Strategic Command, we collectively spent many years providing oversight, direction and maintenance of U.S. strategic nuclear forces and advising presidents from Ronald Reagan to George W. Bush on strategic nuclear policy. We are writing to express our support for ratification of the New START Treaty. The treaty will enhance American national security in several important ways.

First, while it was not possible at this time to address the important issues of non-strategic weapons and total strategic nuclear stockpiles, the New START Treaty sustains limits on deployed Russian strategic nuclear weapons that will allow the United States to continue to reduce its own deployed strategic nuclear weapons. Given the end of the Cold War, there is little concern today about the probability of a Russian nuclear attack. But continuing the formal strategic arms reduction process will contribute to a more productive and safer relationship with Russia.

Second, the New START Treaty contains verification and transparency measures—such as data exchanges, periodic data updates, notifications, unique identifiers on strategic systems, some access to telemetry and on-site inspections—that will give us important insights into Russian strategic nuclear forces and how they operate those forces. We will understand Russian strategic forces much better with the treaty than would be the case without it. For example, the treaty permits on-site inspections that will allow us to observe and confirm the number of warheads on individual Russian missiles; we cannot do that with just national technical means of verification. That kind of transparency will contribute to a more stable relationship between our two countries. It will also give us greater predictability about Russian strategic forces, so that we can make better-informed decisions about how we shape and operate our own forces.

Third, although the New START Treaty will require U.S. reductions, we believe that the post-treaty force will represent a survivable, robust and effective deterrent, one fully capable of deterring attack on both the United States and America’s allies and partners.

The Department of Defense has said that it will, under the treaty, maintain 14 Trident ballistic missile submarines, each equipped to carry 20 Trident D-5 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). As two of the 14 submarines are normally in long-term maintenance without missiles on board, the U.S. Navy will deploy 240 Trident SLBMs.

Under the treaty’s terms, the United States will also be able to deploy up to 420 Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and up to 60 heavy bombers equipped for nuclear armaments. That will continue to be a formidable force that will ensure deterrence and give the President, should it be necessary, a broad range of military options.

We understand that one major concern about the treaty is whether or not it will affect U.S. missile defense plans. The treaty preamble notes the interrelationship between offense and defense; this is a simple and long-accepted reality. The size of one side’s missile defenses can affect the strategic offensive forces of the other. But the treaty provides no meaningful constraint on U.S. missile defense plans. The prohibition on placing missile defense interceptors in ICBM or SLBM launchers does not constrain us from planned deployments.

The New START Treaty will contribute to a more stable U.S.-Russian relationship. We strongly endorse its early ratification and entry into force.

Sincerely,

General Bennie Davis (USAF, Ret) [SAC CINC 1981-1985]

General Larry Welch (USAF, Ret) [SAC CINC 1985-1986]

General John Chain (USAF, Ret) [SAC CINC 1986-1991]

General Lee Butler (USAF, Ret) [SAC CINC 1991-1992, STRATCOM CINC 1992-1994]

Admiral Henry Chiles (USN, Ret) [STRATCOM CINC 1994-1996]

General Eugene Habiger (USAF, Ret) [STRATCOM CINC 1996-1998]

Admiral James Ellis (USN, Ret) [STRATCOM CINC 2002-2004]

The original letter is here.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Plan Shows Cuts and Massive Investments

The Obama administration’s first nuclear weapons stockpile management plan is ready

By Hans M. Kristensen

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) has sent Congress the FY 2011 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) with new information about what the administration plans to spend on maintaining and modernizing nuclear weapons and facilities over the next 15-20 years.

FAS and UCS got hold of the unclassified sections of the plan and have analyzed what the Obama administration’s first nuclear weapons management plan tells us about how the Prague speech vision will be translated into national nuclear weapons policy. The SSMP consists of five sections (three are unclassified):

- FY 2011 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan Summary (unclassified)

- Annex A – FY 2011 Stockpile Stewardship Plan (unclassified)

- Annex B – FY 2011 Stockpile Management Plan (classified)

- Annex C – FY 2011 Science, Technology, and Engineering Report on Stockpile Stewardship Criteria and Assessment of Stockpile Stewardship Program (classified), and

- Annex D – FY 2011 Biennial Plan and Budget Assessment on the Modernization and Refurbishment of the Nuclear Security Complex (unclassified)

Smaller Nuclear Stockpile Planned

The good news is that plan shows that the United States intends to reduce the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile by 30 to 40 percent from today’s total of approximately 5,000 weapons to 3,000-3,500 weapons at least by 2022.

Initiatives already underway from the previous administration are currently reducing the arsenal to some 4,700 weapons by the end of 2012, and the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) released in April will likely result in additional reserve weapons being retired.

The “3,000 to 3,500 active, logistic spare, and reserve warheads” would be the largest stockpile that could be supported by the weapons industrial complex proposed by the new plan, and about twice the size of the New START treaty limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads (note that the stockpile also contains non-strategic and non-deployed warheads).

Massive Investments Forecast

The reduction comes at a considerable price. To support the stockpile, the NNSA intends to spend more than $175 billion (in then-year dollars) over the next two decades on building new nuclear weapons factories, testing and simulation facilities, and modernizing and extending the life of the nuclear weapons in the stockpile.

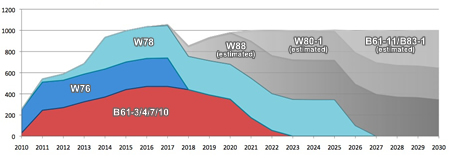

The plan shows for the first time how much will be spent on modernizing and extending the life of three nuclear weapons: the B61 gravity bomb, the W76 sea-based strategic warhead, and the W78 land-based strategic warhead. The cost is approximately $10 billion (in then-year dollars) between 2010 and 2025, peaking at about $1.05 billion in 2017 (at about the same time the New START strategic arms reduction treaty enters into force). Additional costs will follow as the remaining warheads in the stockpile are modernized and life-extended, projected at $1 billion per year in 2021-2030 (in then-year dollars).

.

The plan does not include the more than $100 billion the Department of Defense is expected to spend in 2010-2030 on the platforms needed to deliver the warheads. This includes a new class of ballistic missile submarines (estimated at $80 billion-plus), a new long-range bomber (presumably with a new cruise missile), and a new tactical fighter-bomber. (See latest Nuclear Notebook on US forces)

Smaller Stockpile, Expensive Complex

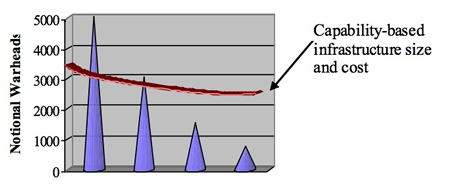

One of the more interesting parts of the plan is NNSA’s claim that even a much smaller nuclear weapons stockpile “would not lead to a smaller, less costly infrastructure” than the one proposed. In fact, NNSA concludes, “the costs to maintain capabilities necessary to support the stockpile are essentially independent of the size of the stockpile.” (Emphasis added)

| NNSA Stockpile-Complex Cost Matrix

|

|

| The NNSA plan suggests that the infrastructure needed to support a stockpile of less than 1,000 warheads will be about the same size and cost about as much money as the infrastructure needed to support a stockpile of 3,500 warheads.

|

.

According to NNSA’s calculations, even for a nuclear weapons stockpile of about 500 weapons, the size and cost of the infrastructure would be essential the same as what NNSA says is needed for a stockpile of 3,000-3,500 weapons. “After achieving a capability-based infrastructure, smaller total stockpiles than prescribed by post-NPR implementation strategies would not lead to a smaller, less costly infrastructure.” The basis for the argument is that even with 500 weapons, maintaining them would, in NNSA’s assessment, involve the same basic work and facilities as with the larger stockpile.

It is not uncommon to hear claims that proposed funding is the absolute minimum possible, but this claim will demand a lot of scrutiny in the months and years ahead. It implies that today’s complex maintaining 5,000 weapons would be about the same size and cost as the complex needed to maintain 8,000 weapons, which of course is not the case.

“New” Weapons or Just New Weapons

| New Capabilities Planned

|

|

| The NNSA plan includes new capabilities, such as Arming, Fuzing & Firing (AF&AF) for all the warheads in the stockpile

|

The plan echoes the NPR’s promise that the United States will not build “new” nuclear weapons, but it shows that there are plenty of modernization options short of “new.”

Until a few years ago, the United States did not have the capacity to build new nuclear weapons. Since then, however, production of new W88 warheads has restarted and “war reserve” W88s are now entering the stockpile to replace those destroyed in surveillance tests. Other warhead types will follow in the years to come. The SSMP includes plans for building new nuclear weapons production facilities to ramp up warhead production capacity from 20 per year today to 80 per year by 2022.

The planned W78 modernization is described as “the next reentry system,” and the NNSA plan states that modernizing the complex will ensure that “the development cycle of future weapons is compressed.”

The plan strongly commits to continuing “current weapon alterations and modifications” and for adding “alterations/modifications to the enduring stockpile (or future strategic systems).” This includes advanced designs to “enable vastly improved capabilities for next system arming, fuzing, and firing [AF&F] and/or radar componentry….”

AF&F and radar systems are not part of the nuclear explosive package and therefore not normally considered covered by the pledge not to improve military capabilities of nuclear warheads. But “vastly improved capabilities” for AF&F and radar systems can significantly improve the military capabilities of a weapon and change the scenarios in which it can be used. One example is the new AF&F installed on the W76-1 during the current life-extension program, which adds new height of burst settings that increase the type of facilities the weapon can be used against. Another example is the B61-11 introduced in 1997, which is a modified B61-7 but with significantly different military capabilities.

Safety and Security as Modernization Drivers

Another category of warhead modernizations described in the plan involves the addition of new safety and security features to existing (and future) warheads. The demand for increased surety, as safety and security are jointly called, was triggered by the terrorist attacks in 2001 and has resulted in the pursuit of what the NNSA plan describes as “effective, affordable use denial options that address 21st century threats.”

| Safety and Security Pursuit

|

|

| Additional nuclear surety capabilities have become important divers for warhead modernization: all warheads will get some

|

It is not clear why the requirement for new surety features has increased, much less how much is needed. The same weapons were deployed before 2001 without any problems, but NNSA states that the new surety features are being pursued “independent of any threat scenario.”

In the near-term, the development focuses on new power management systems, security sensors, and integrated surety solutions such as advanced internal/external use-denial technologies. Warheads refurbished after 2010 will get new stronglink concepts, optical firing sets, and detonator safing. Longer-term developments include “multi-point safety for future insertion opportunities,” a capability that can significantly affect the nuclear package.

Most people obviously see nuclear weapons safety and security as important, but the addition of new features will gradually bring modified life-extended warheads further from their tested design. Since this could lead to demands for warhead replacements or even testing in the future, and given “the high cost and long time frame associated with integrating, qualifying, and certifying deeply buried subsystems through the LEP process,” a cost-benefit assessment is needed to create a benchmark for how much surety is enough.

And it is important to remember that nuclear weapons surety is not only a matter of what adversaries might do. Does our deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe and atop missiles on alert expose the weapons to additional risks that could be mitigated much cheaper and effectively by withdrawing and de-alerting the weapons?

Plan in Prague Speech Context

The nuclear investments forecast by the NNSA plan – combined with DOD modernization plans – should help undercut claims by (ultra)conservatives and uninformed that the New START treaty with Russia will somehow put the United States at a disadvantage.

Yet the massive investments to build weapons factories and modify warheads also raise questions about how the plan will be seen by the international community that is needed to support the Obama administration’s nonproliferation agenda. How will other nuclear weapon states interpret the plan and U.S. intensions, given that they need to be convinced to reduce, stop producing, and ultimately eliminate nuclear weapons to make nuclear reductions and eventually disarmament a reality?

In his Prague speech in April 2009, President Obama made a dual pledge: On the one hand, to “take concrete steps towards a world without nuclear weapons,” and to “put an end to Cold War thinking” by reducing “the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, and urge others to do the same.” On the other hand, he pledged to “maintain a safe, secure and effective arsenal to deter any adversary, and guarantee that defense to our allies….” Whereas the president spoke of maintaining a nuclear deterrent, the NNSA plan speaks of “evolving and sustaining the nuclear deterrent.” (Emphasis added)

Likewise, while Congress during the past decade canceled or delayed, as NNSA describes them, “opportunities to exercise the full suite of design competencies through life extensions and modernizations” of nuclear weapons (presumably the Nuclear Robust Earth Penetrator and the Reliable Replacement Warhead), the new plan is designed for “providing the opportunity to fully exercise design and production skills” and “vastly improved capabilities” of modified warhead components.

The plan does echo the pledge to reduce the nuclear weapons stockpile, but that goal is conditioned on building new nuclear weapons production factories and creating a “more agile deterrent.” As the plan bluntly states, a “multi-year and steady investment in the modernization of the complex is an essential element of the NPR, allowing the United States to safely reduce the role of nuclear weapons.”

Striking a balance between disarmament and deterrence – a balance that conveys an clear transition towards disarmament – will be delicate and the administration must work to ensure that the goodwill of Prague is not undercut by nuclear modernizations.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

NPT RevCon ends with a consensus Final Document

by Alicia Godsberg

The NPT Review Conference ended last Friday with the adoption by consensus of a Final Document that includes both a review of commitments and a forward looking action plan for nuclear disarmament, non-proliferation and the promotion of the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. In the early part of last week it was unclear if consensus would be reached, as states entered last-minute negotiations over contentious issues. While the consensus document represents a real achievement and is a relief after the failure of the last Review Conference in 2005 to produce a similar document, much of the language in the action plan has been watered down from previous versions and documents, leaving the world to wait until the next review in 2015 to see how far these initial steps will take the global community toward fulfilling the Treaty’s goals. (more…)