New Report: US and Russian Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

|

| A new report describes U.S. and Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A new report estimates that Russia and the United States combined have a total of roughly 2,800 nuclear warheads assigned to their non-strategic nuclear forces. Several thousands more have been retired and are awaiting dismantlement.

The report comes shortly before the NATO Summit in Chicago on 20-21 May, where the alliance is expected to approve the conclusions of a year-long Deterrence and Defense Posture Review that will, among other things, determine the “appropriate mix” of nuclear and non-nuclear forces in Europe. It marks the 20-year anniversary of the Presidential Unilateral Initiatives in the early 1990s that resulted in sweeping reductions of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

Twenty years later, the new report Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons estimates that U.S. and Russian non-strategic nuclear forces are deployed at nearly 100 bases across Russia, Europe and the United States. The nuclear warheads assigned to these forces are in central storage, except nearly 200 bombs that the U.S. Air Force forward-deploys in almost 90 underground vaults inside aircraft shelters at six bases in five European countries.

The report concludes that excessive and outdated secrecy about non-strategic nuclear weapons inventories, characteristics, locations, missions and dismantlements have created unnecessary and counterproductive uncertainty, suspicion and worst-case assumptions that undermine relations between Russia and NATO.

Russia and the United States and NATO can and should increase transparency of their non-strategic nuclear forces by disclosing overall numbers, storage locations, delivery vehicles, and how much of their total inventories have been retired and are awaiting dismantlement.

The report concludes that unilateral reductions have been, by far, the most effective means to reducing the number and role of non-strategic nuclear weapons. Yet now the two sides appear to be holding on to the remaining weapons to have something to bargain with in a future treaty to reduce non-strategic nuclear weapons.

NATO has decided that any further reductions in U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe must take into account the larger Russian arsenal, and Russia has announced that it will not discuss reductions in its non-strategic nuclear forces unless the U.S. withdraws its non-strategic nuclear bombs from Europe. Combined, these positions appear to obstruct reductions rather facilitate reductions. Russian reductions should be a goal, not a precondition, for further NATO reductions.

Download the full report here: /_docs/Non_Strategic_Nuclear_Weapons.pdf

Slides from briefing at U.S. Senate are here: /programs/ssp/nukes/publications1/Brief2012_TacNukes.pdf

See also our Nuclear Notebooks on the total nuclear arsenals of Russia and the United States.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

On May 20-21, 28 NATO member countries will convene in Chicago to approve the conclusions of a year-long Deterrence and Defense Posture Review (DDPR). Among other issues, the review will determine the number and role of the U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons deployed in Europe and how NATO might work to reduce its nuclear posture as well as Russia’s inventory of such weapons in the future.

Lack of transparency fuels mistrust and worst-case assumptions and the concerns some eastern NATO countries have about Russia have been used to prevent a withdrawal of the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe. The DDPR is expected to endorse the current deployment in Europe.

A new FAS report (PDF) concludes that non-strategic nuclear weapons are neither the reason nor the solution for Europe’s security issues today but that lack of political leadership has allowed bureaucrats to give these weapons a legitimacy they don’t possess and shouldn’t have.

Nuclear Studies and Republican Disarmers

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A recent report by the Associated Press that the administration is considering deep cuts in U.S. nuclear forces has Congressional Republicans and frequent critics of nuclear reductions up in arms.

The AP report quoted “a former government official and a congressional staffer” saying the administration is studying options for the next round of arms control talk with Russia that envision reducing the number of deployed strategic warheads to 1,000-1,100, 700-800, and 300-400.

Congressional Republicans and right-wing institutions have criticized the administration for preparing reckless unilateral cuts that jeopardize U.S. security.

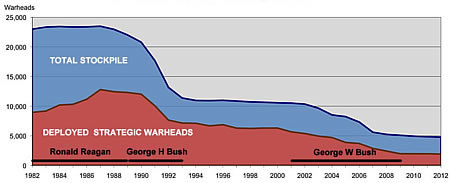

As it turns out, Republican presidents have been the biggest nuclear reducers in the post-Cold War era. Republican presidents seem to have a thing for 50 percent nuclear reductions.

During the George H.W. Bush presidency from 1989-1993, the size of the U.S. nuclear stockpile was cut by nearly 50 percent from 22,217 to 11,511 warheads. The number of deployed strategic warheads dropped from 12,300 to 7,114, or 42 percent, during the same period.

Likewise, during the George W. Bush presidency from 2001-2009, the stockpile was cut by nearly 50 percent from 10,526 to 5,113 warheads. The number of deployed strategic warheads was cut by 65 percent from 5,668 to 1,968 warheads.

A reduction to 1,000-1,100 would be about 30 percent below the New START treaty limit, a drop similar to the 30 percent reduction between the New START treaty and the Moscow Treaty ceiling of 2,200 warheads. A reduction to 300-400 would be a reduction of approximately 77 percent – right up there with the Bush cuts of the past two decades.

Those Bushies must have been reckless liberals in disguise.

Outside Congress, conservative institutions and analysts rally against the administration’s nuclear review saying it’s done in the wrong way, no one will follow, and the U.S. is not modernizing its nuclear forces like other nuclear powers.

A Heritage Foundation blog post mischaracterizes the reduced force levels being studied as “unilateral” cuts and says “there is ample historical evidence” that unilateral reductions will not cause other nuclear powers to follow.

But while there may be no guarantee that other nuclear powers will follow, there certainly is ample historical evidence that they have done so in the past. The unilateral presidential initiative by president George H.W. Bush in 1991 canceled nuclear modernizations, withdrew nonstrategic nuclear weapons from overseas locations and the fleet, retired strategic weapon systems, and stood down bombers from alert with nuclear weapons onboard. The Soviet Union and later Russia followed with significant reductions of their own – reductions that directly benefitted U.S. national security and that of its allies. Britain and France later followed with their own unilateral reductions.

Although I don’t think the current review is about unilateral reductions but about developing potential options for the next round of negotiations with Russia, unilateral initiatives can jumpstart a process by cutting through the fog of naysayers.

The Heritage blog also mischaracterizes the United States as “the only country without a substantial nuclear weapons modernization program.” That’s quite a stretch given that the U.S. has recently converted four SSBNs to carry the Trident II D5 SLBM, has just finished modernizing its Minuteman III ICBM force and replacing the W62 warhead with the more powerful W87, has full-scale production underway of the W76-1 warhead, is preparing full-scaled production of the new B61-12 bomb, is producing a nuclear-capable F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, is studying a new common warhead for ICBMs and SLBMs, is designing a new class of 12 SSBNs, is designing a new long-range bomber, is studying a replacement for the Minuteman III ICBM, and is building new or modernized nuclear weapons production facilities.

That looks like a pretty busy modernization effort to me.

Similarly, an article in The Washington Free Beacon warns that the deepest cut being considered “would leave Pentagon with fewer warheads than China.” Not so. The 300-400 option is for deployed strategic warheads, not the total arsenal. China’s total arsenal includes about 240 warheads, none of which are deployed.

The same article also quotes an unnamed congressional official saying that no president in the past ever told the Pentagon to conduct a review based on specific numbers of warheads. “In the past, the way it worked was, ‘tell me what the world is like and then tell me what the force should be,’” the official said. “That is not happening in this review.”

Well, in this review, as in other reviews intended to reduce nuclear forces, the process begins with the White House asking the Pentagon to examine the options for lower levels. Of course the military is asked to examine implications of a certain range of options; Pentagon reviews have a tendency to be worst-case and the force levels higher than strictly needed. The nice round numbers of arms control treaties are shaped by 1) presidential intent, 2) force structure analysis, and 3) they have to be lower than the previous treaty limit.

During the 1990s, for example, STRATCOM conducted a series of force structure studies in response to – and in anticipation of – future reductions. STRATCOM was created partly to get around the Air Force-Navy rivalry and create a single voice for nuclear force structure analysis. But STRATCOM’s analysis obviously is focused on the needs of the warfighter to meet presidential guidance. As such, there is a tendency to protect force structure and avoid cutting too much too fast. That’s to be expected but it shows that one cannot simply leave it to the military to define what the force should be; it should be an interactive and inter-agency process because the proper nuclear posture is not – and should not be – simply a military matter.

So even if the United States were to cut it’s number of deployed strategic warheads to the lowest number said to be under consideration, those 300-400 warheads would be still more than enough to threaten destruction of Russia. Thousands of additional non-deployed warheads would be in reserve to upload if necessary. Requirements for greater numbers of deployed warheads only emerge when warfighters are asked to use them to hold at risk other nuclear forces, command and control facilities, political and military leadership targets, and war-supporting industry in a myriad of different strike scenarios.

If the administration could convince the Kremlin that it is in Russia’s interest to reduce as well, both countries would be better off.

Further reading:

• “Perspectives on the 2013 Budget Request and President Obama’s Guidance on the Future of the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Program,” briefing to the Fourth Nuclear Deterrence Summit, February 15, 2011.

• “Reviewing Nuclear Guidance: Putting Obama’s Words Into Action,” Arms Control Today, November 2011.

See also: Ivan Oelrich, “Obama’s ‘Radical’ Option for America’s Nuclear Future,” The Atlantic, February 20, 2012.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Cirincione: Obama’s Turn on Nuclear Weapons

By Hans M. Kristensen

It is worth your time reading Joe Cirincione’s article in Foreign Affairs: Obama’s Turn on Nuclear Weapons.

And I’m not just saying this because Joe is president of the Ploughshares Fund, one of my funders. He does a great job in describing the Obama administration’s ongoing nuclear targeting review and its place in the life of the administration with the myriads of policy issues and special interests that limit the president’s options in fulfilling the nuclear disarmament vision he presented in Prague in 2009.

That vision, as I wrote last week, was not visible in the Pentagon’s preview of it FY2013 defense budget request. It is an oversight that must be fixed. The defense budget must be in sync with U.S. nuclear policy, which now requires concrete steps to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons.

For more background on the targeting review and the strategic nuclear war plan, see:

* Reviewing Nuclear Guidance: Putting Obama’s Words Into Action (November 2011)

* Obama and the Nuclear War Plan (February 2010)

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Budget Blunder: “No Cuts” in Nuclear Forces

|

| The new defense budget has “no cuts” in nuclear forces. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

“There are no cuts made in the nuclear force in this budget.” That clear statement was made yesterday by deputy defense secretary Ashton Carter during the Pentagon’s briefing on the defense budget request for Fiscal Year 2013.

We’ll have to see what’s hidden in the budget documents once they are released next month, but the statement is disappointing for anyone who had hopes that the administration’s promises about “concrete steps” to reduce the number and role of nuclear weapons and to “put an end to Cold War thinking” would actually be reflected in the new defense budget.

Not so for the FY13 budget. Other than a decision to delay work for two years on the next generation ballistic missile submarine, the Defense Budget Priorities and Choices report released yesterday does not list any nuclear reductions; neither previously announced nor new ones.

But one year after the New START treaty entered into effect and 18 months after the Nuclear Posture Review was completed, it would have made sense to include some nuclear cuts in this budget – especially because this budget includes programming for future budget years through 2017, only one year before the New START treaty has to be implemented. Specifically, the Pentagon should have explained how (and how soon) it will achieve the previously announced plans to:

- Reduce the number of nuclear bombers to 60 deployed aircraft;

- Reduce the number of ICBMs to no more than 420 deployed missiles;

- Reduce the number of SLBMs to no more than 240 deployed missiles;

- Retire the nuclear Tomahawk cruise missile.

Why wait? Demonstrating that the U.S. is not only talking about reducing its nuclear forces but also doing so through near term defense budget cuts would have been an important signal to other nuclear weapon states whose militaries are waiting to see what has changed in the U.S. nuclear posture. It would also have been an important signal to the countries in the international nuclear nonproliferation regime that will convene in May to prepare for the next review of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, countries whose support we need to strengthen the nonproliferation regime.

Instead, the administration might now have to spend a good part of the next year saying: “Trust us, we’re working on it.”

And it is working on it. The most important effort is the review currently underway within the administration of the requirements for targeting and alert levels of nuclear forces – requirements that determine the force level. The review may well decide additional reductions beyond New START.

In a hint to what might come, the new defense strategic guidance published in early January stated: “It is possible that our deterrence goals can be achieved with a smaller nuclear force, which would reduce the number of nuclear weapons in our inventory as well as their role in U.S. national security strategy.” (Emphasis in original.)

The Defense Budget Priorities and Choices document appears to reaffirm this by stating that the White House review “will address the potential for maintaining our deterrent with a different nuclear force.”

Once the deterrence review is completed, it is important that the White House explains to the world what it has decided and doesn’t leave it to leaks and vague comments by anonymous officials to determine what the international perception of the direction of the U.S. nuclear posture will be.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

A New Defense Strategy: A New Nuclear Strategy?

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Obama administration today presented a new defense strategy that it says is needed to realign U.S. military forces and doctrine with the reductions in combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan as well as the new fiscal constraints created by the financial crisis.

There are few details in the new strategy for how this will be done but more will come in the Fiscal Year 2013 defense budget request expected in early February.

On nuclear forces the new strategy reaffirms the commitment to maintain a “safe, secure, and effective” nuclear arsenal as long as nuclear weapons exist. “We will field nuclear forces that can under any circumstances confront an adversary with the prospect of unacceptable damage, both to deter potential adversaries and to assure U.S. allies and other security partners that they can count on America’s security commitments.” The strategy appears heavily focused on the Pacific region and the Middle East. China and Iran, more so than North Korea, appear to be the primary potential adversaries, although Russian is by far the largest potential nuclear adversary.

In Prague in 2009, President Obama forcefully committed the United States “to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons,” that it was necessary to “ignore the voices who tell us that the world cannot change,” that the “United States will take concrete steps toward a world without nuclear weapons,” and that “To put and end to Cold War thinking, we will reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy….” The New START treaty requires some reductions in deployed strategic forces, and the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) reaffirmed the commitment to nuclear disarmament and further reducing the role of nuclear weapons.

The new defense strategy language comes across as somewhat timid, stating only: “It is possible that our deterrence goals can be achieved with a smaller nuclear force, which would reduce the number of nuclear weapons in our inventory as well as their role in U.S. national security strategy.” This language presumably reflects the preliminary findings of the administration’s so-called Post-NPR Analysis, an ongoing effort within the administration to make “preparations for the next round of nuclear reductions” with Russia through “potential changes in targeting requirements and alert postures.”

FAS has long argued that U.S. nuclear forces can and should be reduced further and that a sufficient nuclear deterrent can be maintained with far fewer weapons, lower operational readiness, and by changing the presidential guidance for how the military is required to plan for the potential use of nuclear weapons.

In Europe, which was the focus of U.S. strategy during the Cold War, FAS has argued that the demise of the Soviet threat and the fundamentally different security challenges requiring NATO’s attention today permit the withdrawal of the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe. The new U.S. defense strategy concludes that the changed security landscape allows changes in the European posture that, while maintaining the US security commitment to NATO, require development of a smarter posture that is better suited to meet the challenges of today’s world. Whether this language envisions a withdrawal of non-strategic nuclear weapons from Europe remains to be seen, but it appears to make make it harder to justify continued deployment.

It is important that the commitment in the new defense strategy to maintaining a nuclear deterrent does not overshadow the equally important commitment to reducing the size and role of nuclear forces. The clear message to other nuclear weapons states must be that the emphasis of U.S. policy is the nuclear disarmament trajectory described in Prague and that it is in their interest to follow the lead. Billions of dollars can be saved over the next decade by reducing the nuclear forces and removing nuclear doctrine further from the warfighting thinking that characterized the Cold War and which is still prevalent in today’s planning. That, not indefinite nuclear modernizations, ought to be the priority for the 21st century.

Further reading: “Reviewing Nuclear Guidance: Putting Obama’s Words Into Action,” Arms Control Today, November 2011

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

US Releases Full New START Data

|

| The Obama administration gets a medal for disclosing its New START treaty numbers. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen [updated 12 Dec 2011 with new bomber information]

Anyone familiar with my writings knows that I don’t hand out medals to the nuclear weapon states very often. But the Obama administration deserves one after the U.S. State Department’s recent release of the full U.S. aggregate data under the New START treaty.

The release breaks with the initial practice under the treaty of only publishing overall nuclear force category numbers, and re-establishes the U.S. practice from the previous START treaty of providing maximum disclosure of the strategic forces counted by the treaty. This is a good development that has gone totally unnoticed in the news media.

The pressure is now squarely on Russia to follow suit and publish its New START aggregate data as well.

Overall Posture

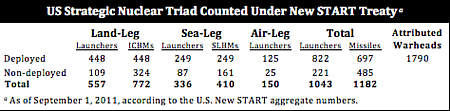

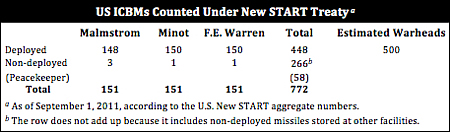

The New START data attributes 1,790 warheads to 822 deployed ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers as of September 1, 2011. A large number of non-deployed missiles and launchers that could be deployed are not attributed warheads.

The data shows that the United States will have to eliminate 243 launchers over the next six years to be in compliance with the treaty by 2018. Fifty-six of these will come from reducing the number of launch tubes per SSBN from 24 to 20, roughly 80 from stripping B-52Gs and nearly half of the B-52Hs of their nuclear capability, and destruction of 100 ICBM launchers.

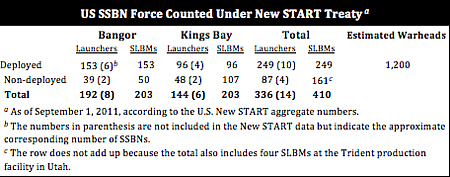

The released data does not contain a breakdown of how the 1,790 deployed warheads are distributed across the three legs of the Triad. But because the bomber number is now disclosed (each bomber counts as one warhead) and because roughly 500 warheads remain on the ICBMs, it is possible to make an estimate of the number of warheads deployed on the ballistic missile submarines: approximately 1,200 warheads, or two-thirds of the total count under New START.

Ballistic Missile Submarines

The New START data shows that the United States as of September 1, 2011, had 249 Trident II SLBMs onboard its SSBN fleet. Each SSBN has 24 missile tubes for a maximum loadout of 288 missiles, but at the time of the New START count three SSBNs were empty and one partially loaded. With an estimated 1,200 warheads on the SLBMs, that translates to an average of 4-5 warheads per missile.

The assumption is normally that 12 out of 14 SSBNs are deployed, with the remaining two in overhaul at any given time. But the New START data illustrates that the force ready for deployment sometimes is smaller, in this case only 10 SSBNs. Other information shows that this ratio fluctuates significantly, and in average 64 percent (8-9) of the SSBNs are at sea with roughly 920 warheads. Up to five of those subs are on alert with 120 missiles carrying an estimated 540 warheads. That’s enough to obliterate every major city on the face of the earth.

The SSBN fleet conducted 33 deterrent patrols last year, with each operational SSBN sailing on three patrols per year, each lasing 70-100 days. That’s a very high operational tempo, comparable to that of the Cold War.

The bulk of the SSBN fleet is based at Bangor (Kitsap) Submarine Base in Washington. Eight subs are homeported at this base, and the New START data shows that two were out of commission on September 11, 2011: one had empty missile tubes – possibly because it was in dry dock – and another was only partially loaded – possibly because it was in the middle of a missile exchange when the count occurred. This means that six of eight SSBNs at the base were loaded with Trident II D5 missiles at the time of the New START count.

A satellite image taken on August 20, 2011, only 11 days before the New START data count, shows three Ohio-class subs present at Bangor, including one in dry dock and another at the Explosives Handling Wharf. (see figure below).

|

| Three SSBNs were present at Bangor Submarine Base on August 20, shortly before the New START count. Click on image for full size. |

.

The same image also shows two Ohio-class subs at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard at Bremerton, Washington, only a few miles away. One of the two is an SSGN, a former SSBN stripped of its nuclear missiles and converted to carry cruise missiles and special forces. The other appears to be an SSBN. The New START data does not reflect two entirely empty SSBNs on the west coast, so either one of them was loaded with missiles between the time of the satellite image and the New START count, or the SSBN at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard is from Kings Bay.

The remaining five Bangor-based SSBNs that were at sea the day the image was taken carried 120 missiles with an estimated 540 warheads. Three of those were on alert with 72 missiles and roughly 325 warheads.

In the Atlantic, six SSBNs are based at Kings Bay Submarine Base in Georgia, a significant change from the Cold War when most U.S. SSBNs were homeported on the east coast. Two of the six subs did not carry missiles on September 1, 2011, leaving a deployable force of four SSBNs carrying 96 missiles with an estimated 430 warheads.

The New START data shows that the U.S. Navy has not yet begun to reduce the number of missile tubes on each SSBN. The Pentagon has stated that the number of missile tubes on each submarine will be reduced from 24 to 20 before the New START enters into force in 2018.

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles

The New START data shows that the United States deployed 448 Minuteman III ICBMs as of September 1, 2011. Most were at the three launch bases, but a significant number were in storage at maintenance and storage facilities in Utah. That included 58 MX Peacekeeper ICBMs retired in 2003-2005 but which have not been destroyed.

The New START data does not show how many warheads were loaded on the 448 deployed ICBMs, but the number is thought to be approximately 500. The 2010 NPR decided to “de-MIRV” the ICBM force, an unfortunately choice of words because the force will be downloaded to one warhead per missile, but retain the capability to re-MIRV if necessary.

Heavy Bombers [updated 12 Dec 2011 with new B-1 information]

The New START data shows that the U.S. Air Force possessed 152 B-2 and B-52 bombers as of September 1, 2011. Of these, 125 were counted as deployed. The disclosure of the bomber count breakdown is important because it has been unclear how many bombers were actually counted by the treaty. The count includes B-52G bombers that are not used for nuclear missions, but still carry equipment that makes them accountable under the treaty. The last of the B-1s that were still nuclear capable when the treaty was signed were denuclearized in early 2011.

Of the 20 B-2s and 93 B-52s, 18 and 76 (a total of 94), respectively, are nuclear-capable. But only about 60 those are thought to be nuclear tasked at any given time. Stripping excess B-52Hs and the remaining B-52Gs of their nuclear equipment will be necessary to get down to 60 nuclear-capable bombers by 2018.

Heavy bombers do not carry nuclear weapons under normal circumstances, but a few hundred warheads are thought to be stored at the three bomber bases. In addition, hundreds of additional bomber warheads are in central storage. Overall, some 1,000 bombs and cruise missiles are thought to be earmarked for use by the bombers. The NPR states that bombers (along with SSBNs) play an important role in warhead upload scenarios.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The State Department’s release of the full U.S. aggregate data under the New START treaty deserves credit because it increases transparency of U.S. nuclear forces and restores the practice under the previous START treaty of disclosing such information to the public.

After the New START treaty was signed in April 2010 and entered into force in February 2011, it first appeared as if this information would not be released. I warned against this in March, and in May, three former U.S. officials joined FAS in urging the United States and Russia to disclose the full aggregate data.

The first New START aggregate data from February (released in June) did not follow the advice; only six overall numbers were disclosed. The new release of the full September data corrects that mistake.

In context, the data release is extra impressive because it follows the release of other important nuclear information by the United States over the past 18 months, most importantly the disclosure in May last year of the size and history of the total nuclear warhead stockpile and warhead dismantlement.

Following all of this, a clear responsibility now rests on Russia to follow suit and begin to lift the veil for its nuclear arsenal as well. Russia generally discloses very little about its nuclear forces and is falling behind Britain, France, and the United States in transparency. Andrei Nesterenko from the Russian foreign ministry stated in May 2010 that after the New START treaty “comes into force, we will also be able to consider practically the issue of publishing the total amount of deployed strategic carriers and…warheads.”

Well, now the treaty is in force, and with the Preparatory Committee for the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) – the so-called NPT PREPCOM – coming up in early May 2012, the next few months would be a good time for Russia to follow the U.S. lead and release the full New START aggregate numbers.

After all, if the Kremlin can share this information with the Pentagon, what’s the point in denying it to the rest of the world?

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Article On Obama Administration Nuclear Targeting Review

|

| New article published in Arms Control Today |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The latest issue of Arms Control Today includes a new article by Robert Norris and myself about the nuclear targeting review that is currently underway in the Obama administration.

In ordering the review, formally known as the Post-NPR Review, President Obama has asked the military to review and revise U.S. nuclear strategy and guidance on the roles and missions of nuclear weapons, including potential changes in targeting requirements and alert postures, in preparation for the next round of nuclear reductions beyond the New START treaty with Russia.

Our article describes the bureaucratic labyrinth the review will go through before new presidential guidance emerges to change the U.S. nuclear war plan. To that end, we offer a wide range of suggestions for how the review could reduce the requirements for U.S. nuclear forces to “put an end to Cold War thinking,” as President Obama said in his Prague speech in 2009.

Note: accessing the article requires subscription to Arms Control Today.

Further information: Obama and the Nuclear War Plan (FAS, 2010).

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

End of the B53 Era; Continuation of the Spin Era

By Katie Colten and Hans Kristensen

[Modifed] Today, one of the largest weapons in the United States nuclear weapons arsenal, the B53, will be dismantled at the Pantex Plant in Amarillo, Texas. Developed during the Cold War and deployed in 1962, this bomb weighs as much as a minivan and has an explosive yield of nine megatons, equivalent to 750 Hiroshima bombs.

Retired from the arsenal in 1997, the dismantlement of the B53 marks the end of the era of large, multi-megaton bombs, a hallmark of the Cold War. The largest-yield warhead in the U.S. stockpile today is the B83 bomb, which has a maximum yield of 1.2 Megatons.

Administration officials have been busy spinning the dismantlement as proof of the administration’s commitment to nuclear disarmament and as vindication of its plan to spend billions of extra dollars to modernize the nuclear weapons production complex.

In a statement published on the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) web site, Daniel Poneman, the deputy secretary of energy, said that the B53 dismantlement “is a major accomplishment that has made the world safer,” and that “safely [sic] and securely dismantling surplus weapons is a critical step along the road to achieving President Obama’s vision of a world without nuclear weapons.”

“The elimination of the B53 is a significant milestone in our efforts to reduce the number of nuclear weapons and implement President Obama’s nuclear security agenda,” said Thomas D’Agostino, head of NNSA. “Today, we’re moving beyond the Cold War nuclear weapons complex that built it and toward a 21st century Nuclear Security Enterprise.”

If the B53 dismantlement indeed “is a major accomplishment that has made the world safer” and “a critical step along the road to achieving President Obama’s vision of a world without nuclear weapons,” as Boneman says, one might ask why it took 13 years to dismantle the weapon after it was retired in 1997? One reason is that dismantlement is not the priority at the Pantex Plant, which is busy with full-scale production of the W76-1 warhead for U.S. and British sea-launched ballistic missiles, as well as surveillance and repair of the warheads in the “enduring stockpile.”

Warhead Dismantlements

We certainly congratulate the administration on finally dismantling the old B53, but one should not over-spin the achievement. The B53 dismantlement involves less than 50 warheads; the U.S. has approximately 8,500 intact warheads (counting those in the stockpile and dismantlement queue). And warhead dismantling under the Obama administration continues to follow the low rate standard set by the Bush administration. The current dismantlement rate is secret (though past history has been declassified), but very low (only 300-400 warheads per year, according to my estimate) compared with the rate during the 1990s when more than 1,000 warheads were dismantled each year. And it’s not as if there is a lack of retired warheads waiting to be dismantled: more than 3,000 (according to my estimate; the official number is also secret). At the current rate, the backlog of warheads retired through 2009 will not be dismantled until 2022. Additional warheads retired after 2009 will push the completion date further into the future.

Dismantlement performance is an important way to demonstrate U.S. commitment to non-proliferation and disarmament, but the low rate and the secrecy undermine that important effort. And so does the spin. When D’Agostino said in May 2009 that the dismantlement rate had risen more than 150 percent since 2006, he didn’t say that it would drop by half in 2009. Nor did NNSA announce the reduction. Rather than cherry-picking the good news and hiding the bad behind secrecy, the administration should disclose the real numbers and let them speak for themselves.

Warhead Safety

We also agree that it is good to get rid of an unsafe weapon. But since NNSA points to the importance of safety, one should not gloss over the fact that consecutive administrations allowed the B53 to remain in the stockpile even though they knew full well that it was unsafe. The Reagan administration retired the B53 but then decided in 1987 to return the weapon to the stockpile to stand alert against Soviet underground facilities. After a review in 1991 found the B53 to be unsafe, DOE “strongly recommended” to DOD in 1993 that the weapon be retired at the “earliest possible date.” Yet the B53 war allowed to remain in the stockpile for another four years until 1997 when its mission was taken over by the new B61-11 nuclear earth penetrator.

The B53 is not the only case of safety being overruled by targeting requirements. The W62 warhead, the last of which was dismantled in August 2010, was deployed on the Minuteman III ICBMs through 2009, even though the warhead had a lower safety rating than the B53 (D versus C-, according to a 1991 Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory study). The W62 safety exemption is all the more striking given that the ICBMs that carried the warhead were on high alert, something that ended for the B53 in 1991.

|

| Even though it was found to be more unsafe than the B53 bomb, the W62 warhead (seen here at Warren Air Force Base in 2009) was allowed to continue to arm Minuteman III ICBMs on alert until 2009. |

.

Nuclear Funding

As for the B53 dismantlement being used to justify funding the modernization of the nuclear weapons complex, that claim is certainly a stretch given the dismantlement was done using the “old” complex; the modernized complex is not scheduled to come online until the mid-2020s, at which point the current backlog of retired nuclear warheads will be gone. NNSA’s nuclear weapons budget has already been increased by 10 percent over the Bush administration, and the latest Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan shows that the administration plans another 10 percent increase. That funding level is incompatible with current fiscal realities, and no amount of B53 spin can change that fact.

News Clips:

Oct 26: USA Today, “U.S.-made ‘monster’ nuclear warhead B53 dismantled”

Oct 25: Associated Press, “US’s most powerful nuclear bomb being dismantled”

Oct 25: National Public Radio – All Things Considered, “Cold War Bomb to be Dismantled”

Oct 25: Agence France-Presse, “U.S. Dismantles Last Big Cold War Nuclear Bomb”

Oct 25: Wired UK, “Last Nuclear ‘Monster Weapon’ Gets Dismantled”

Oct 25: Daily Mail (UK), “Dismantling the mega-nuke: America begins to take apart B53 that was 600 times more powerful than bomb that flattened Hiroshima”

Oct 25: Gawker, “Goodnight Sweet ‘Monster Weapon'”

More Information:

October 2010: FAS Strategic Security Blog, “Scrapping the Unsafe Nuke”

2005: nukestrat.com, “Reagan Administration Decision to Retain the B53”

April 2005: nukestrat.com, “The Birth of a Nuclear Bomb: B61-11”

December 1991: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, “Assessment of the Safety of U.S. Nuclear Weapons and Related Nuclear Test Requirements: A Post-Bush Initiative Update”

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Data: Modest Reductions and Decreased Transparency

|

| New START aggregate numbers have been published by the United States and Russia. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The latest New START treaty aggregate numbers of strategic arms, which was quietly released by the State Department earlier last week, shows modest reductions and important changes in U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear forces.

Most surprisingly, the data shows that Russia has increased its number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads and is now again above the New START limit.

Because of the limited format of the released aggregate numbers, however, the changes are not explained or apparent. As a result, though not yet one year old, the New START treaty is already beginning to increase uncertainty about the status of U.S. and Russian nuclear forces.

Overall Changes

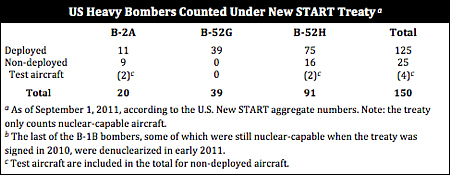

Combined, the data shows that the United States and Russia as of September 2011 deployed 3,356 nuclear warheads on 1,338 strategic delivery vehicles, down from 3,337 warheads on 1,403 delivery vehicles in February 2011.

A modest combined reduction of 65 delivery vehicles in seven months, but an increase of 19 warheads; apparently they two nuclear superpowers are not in a hurry to reduce.

|

| The New START aggregate data shows modest reductions in strategic delivery vehicles and a Russian increase of deployed strategic warheads. |

.

The aggregate numbers not include thousands of additional strategic and non-strategic warheads that are not counted by the treaty. To put things in perspective, the U.S. military stockpile includes nearly 5,000 warheads; the Russian stockpile probably about 8,000. In addition, thousands of retired, but still intact, warheads are in storage for a total combined U.S. and Russian inventory of perhaps 19,000 warheads.

Russia

Most surprising is that the New START data erases Russia’s achievement from earlier this year when its number of deployed strategic warheads temporarily dipped below the treaty limit of 1,550 warheads. According to the new data, Russia has slightly increased (by 29) the number of warheads deployed on its ballistic missiles and now stands 16 warheads above the treaty limit.

The warhead increase comes at the same time that the number of delivery vehicles has declined by five. But since the New START aggregate data – unlike the previous START treaty – does not include a breakdown of missile types, it is impossible to see where the change happened. As a result, transparency of Russia’s strategic nuclear forces is decreasing.

Part of the explanation is the deployment of additional RS-24 ICBMs, which carry three warheads each. But that’s a limited deployment that doesn’t account for all. Other parts of the puzzle include continued reduction of the single-warhead SS-25 ICBM force, the operational status of individual Delta IV SSBNs, and possibly retirement of one of the aging Delta III SSBNs.

The United States

The New START data shows that the United States only removed 10 warheads from its ballistic missiles during the previous seven months, down from 1,800 to 1,790 warheads.

The number of delivery vehicles declined by 60, from 882 to 822, a change that probably reflects the removal of nuclear-capable equipment from so-called “phantom” bombers. These bombers are counted under the treaty even though they are not actually assigned nuclear missions. The U.S. has not disclosed the number, but another 24, or so, “phantom” bombers probably need to be denuclearized. Stripping these aircraft of their leftover equipment reduces the number of nuclear delivery vehicles counted by the treaty, although it doesn’t actually reduce the nuclear force.

Later this decade will come a gradual reduction of the number of SLBMs deployed on SSBNs from 288 to 240. Likewise, if the bomber force is retained, the ICBM force might be reduced to 400 missiles from 450 today.

Conclusions

The New START data shows that Russia and the United States have gotten off to a slow start and excessive nuclear secrecy is reducing the international community’s ability to monitor and analyze the changes.

Russia essentially has seven and half years to offload 16 warheads from its force to be in compliance with New START by 2018. Not an impressive arms control standard. Instead, the task for Russian planners will be how to phase out old missiles and phase in new missiles. There will be no real constraint on the Russian force.

|

| The United States ICBM force could be a big as Russia’s entire triad by the mid-2020s. |

The new data underscores the substantial lead the United States has over Russia in strategic nuclear delivery vehicles. Even as Russia deploys the RS-24 ICBM and Bulava SLBM in the coming years, the gradual retirement of the SS-18, SS-19, SS-25 and SS-N-18 could reduce the total number of delivery vehicles to perhaps 400 by the time the New START treaty enters into force in 2018.

In contrast, under current plans, the United States intends to retain 700 strategic delivery vehicles by 2018. Without additional unilateral reductions, the United States could end up with 50 percent more strategic delivery vehicles than Russia in its triad by the turn of the decade. Indeed, the U.S. ICBM force alone could at that time include as many delivery vehicles as the entire Russian triad!

The U.S. force will retain a huge upload capability with several thousand non-deployed nuclear warheads that can double the number of warheads on deployed ballistic missiles if necessary. Russia’s ballistic missile force, which is already loaded to capacity, does not have such an upload capability.

This disparity creates fear of strategic instability and is fueling worst-case planning in Russia to deploy a new “heavy” ICBM later this decade.

To prevent a deepening of this trend, the Obama administration’s ongoing nuclear targeting review (see also forthcoming article in Arms Control Today) must significantly reduce the excessive nuclear posture currently planned under New START.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Deficiencies in Deterrence Doctrine

By Darren Ruch, 1st Lt, MA ANG USAF*

In 1991, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the United States was armed with a stockpile of over 18,300 nuclear weapons.[1] Since then, the US Air Force (USAF) has conducted a range of military operations while maintaining a nuclear deterrence capability. Due to a nuclear warhead mishap in 2007, the Air Force reshaped its nuclear deterrence mission and created Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). While the establishment of AFGSC streamlined the effectiveness of US nuclear deterrence, Air Force doctrine still has failed to articulate its leadership requirements at the Non-Commissioned Officer and Company Grade Officer levels to successfully accomplish its mission.

Deterrence is defined as “the prevention from action by fear of the consequences.”[2] Nuclear weapons are not the only deterrent that the US maintains, but it does underpin all other deterrent elements.[3] In order for the nuclear strategic forces to employ an effective mission of deterrence, adversaries and allies must have a fundamental belief that the US has a credible nuclear capability.[4] The US forwards its credibility by maintaining a modified nuclear triad, which includes strike capabilities, active and passive defenses, and responsive infrastructure.[5]

Accidents are inevitable in the military, and the handling and transporting of nuclear weapons is no exception. During the Cold War, with the possibility of a nuclear-tipped missile launch at any given moment, the USAF experienced a number of accidents involving its arsenal.[6] Since the Cold War, the USAF continues to experience occasional mishaps.

The most notable post-Cold War incident occurred in August 2007. A B-52 crew at Minot AFB was tasked to ferry AGM-129 cruise missiles 1,000 miles to Barksdale AFB for terminal storage. Because of an ad hoc change, lack of communication, and failure to follow published procedures, some cruise missiles mistakenly contained W80-1 nuclear warheads.[7] These warheads went unreported missing for nearly 36 hours.[8] This was the first time in over 40 years that a nuclear weapon was flown over US airspace without special high-level authorization.[9]

This incident violated the principals of deterrence, specifically the passive defense corner of the triad mentioned above. The warheads were vulnerable because of deficiencies to physical security and mobility.[10] The credibility of the US’ ability to conduct nuclear operations was negatively impacted, and the Department of Defense (DOD) reacted with reforms.

The DOD and USAF conducted a series of reports, independent assessments, and studies into its ability to conduct nuclear deterrence. One finding on the nuclear enterprise read: “The nuclear mission…has been dispersed from a single-focused strategic command to three operational commands that have had little or no focus on the nuclear mission.”[11] Based on these and other findings, the USAF established AFGSC, a new Major Command under Strategic Command.

The principal mission of AFGSC is nuclear deterrence and global strike operations. Its assets include intercontinental ballistic missiles and B-52 and B-2 bombers. Today, the USAF allocates about 23,000 personnel and $5.2B for nuclear deterrence operations, just over 3% of the FY12 USAF budget.[12][13]

Overseas, the deterrent impacts of AFGSC were nearly immediate and universal. In August 2009, North Korean radio propagated, “the United States is heated up…a command in charge of nuclear forces was newly established.”[14] Also, in the same month, a main Russian national press headlined, “Russia to Create New Strike Systems in Response to US Air Force Activity.”[15] Adversarial states took note of the revamped US deterrence mission and responded to it.

The Air Force’s senior executives, however, did not address the fundamental problem from the 2007 incident: failure of low-level leadership. A series of low-level leadership failures leading up to the mishap, rather than high-level leadership failures, led to the B-52 crew mistakenly ferrying a nuclear warhead over the US.[16] The first error occurred when personnel of the Minot Munitions Maintenance Squadron made a last minute change of which cruise missiles were to be transported and failed to note this change in documents from the internal coordination process.[17] After this first oversight, the breakout crew failed to notice that nuclear warheads were aboard one of the pylons of missiles. The aircrew also failed to conduct a thorough pre- and post-flight inspection of their aircraft, as mandated in standard operating procedures, that would have revealed the presence of nuclear warheads. Inspections of the bomber’s payload failed at three independent and subsequent steps.[18] This series of incidents, all of which stemmed from a failure to follow standard operating procedures, occurred at or below the Squadron level, not because of actions taken by anyone at the General or Senior Executive Service corps.

This incident prompted resignations up the chain of command, from Squadron Commanders to the Secretary and Chief of Staff of the Air Force. But the central failure, which has yet to be addressed in nuclear doctrine or other studies, occurred because of the lack of leadership at the Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO) and Company Grade Officer (CGO) levels. Lieutenant General Frank Klotz, Commander of AFGSC, joked, “the newest B-52 is older than the pilots who fly it, and in some cases twice their age.”[19] Nuclear doctrine, however, centralizes on executive leaders and others who are as old as the B-52. Air Force Doctrine Document (AFDD) 3-72, Nuclear Operations, does not make a single mention of leadership below the national level. The AFDD references a wide range of doctrinal documents, from Basic Doctrine (AFDD 1) to Joint Targeting (JP 3-60), but fails to refer to AFDD 1-1, Leadership and Force Development.[20]

In the first paragraph of its first page, AFDD 1-1 reads, “[there are] two fundamental elements of leadership: the mission, objective, or task to be accomplished, and the people who accomplish it.”[21] While all supporting documentation that drive the deterrence mission is composed at senior executive levels, NCOs and CGOs are the Airmen who accomplish it. Until doctrine addresses this actuality, billions of dollars can continue to reform structures but the US nuclear deterrence strategy will continue to operate at a deficit.

The principal functions of doctrine are to provide an analysis of past experiences, to forward lessons learned and best practices, and to provide a basis of knowledge and understanding that can provide guidance for actions.[22] In the last week of August 2007, there were many lessons that should be passed on to the succeeding generations to provide a common basis of knowledge because of failures at the NCO and CGO levels. By excluding the critical function of the NCO and CGO corps in the AFDD 3-72, the deterrence doctrine document sends a message to General Officers, Senior Executives, and subsequent ranks that the deterrence strategy is accomplished solely at the mission and objective level, not at the operational level. As demonstrated by the August incident, this is inaccurate.

The Air Force underwent a major reshaping effort following the 2007 incident in which a B-52 mistakenly carried nuclear weapons across the country. Assessments from this mishap culminated in the creation of AFGSC, a new Major Command. Responses to those reports and studies failed to modify doctrine to address the critical importance of the NCOs and CGOs carrying out the deterrence mission. Until AFDD 3-72 includes the importance of CGO and NCO leadership, US deterrence will not function at its true potential.

* Darren Ruch works at the Joint Improvised Explosive Device Defeat Organization (JIEDDO) and is a reservist in the US Air Force. As a homemade explosive specialist at JIEDDO, he primarily assists military units deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Also, Ruch serves as a traditional reservist in the Massachusetts Air National Guard as an Officer in their Air Operations Center, a unit that falls under Air Force Global Strike Command. He can be contacted at darren.ruch@ang.af.mil.

References

[1]. Natural Resources Defense Council, “Table of Global Nuclear Weapons Stockpiles, 1945-2002,” http://www.nrdc.org/nuclear/nudb/datab19.asp (accessed 11 June 2011).

[2]. Joint Publication (JP) 1-02, Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, 8 November 2010, 107.

[3]. Air Force Doctrine Document (AFDD) 3-72, Nuclear Operations, 17 September 2010, 2.

[4]. Ibid.

[5]. Ibid, 6.

[6]. Department of Defense, “Narrative Summaries of Accidents Involving U.S. Nuclear Weapons, 1950-1980,” http://www.dod.gov/pubs/foi/reading_room/965.pdf (accessed 11 June 2011).

[7]. Department of Defense, The Defense Science Board Permanent Task Force on Nuclear Weapons Surety, Report on the Unauthorized Movement of Nuclear Weapons (Washington, DC: Office of the Under Secretary of Defense [Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics], February 2008), 3.

[8]. Joby Warrick and Walter Pincus, “Missteps in the Bunker,” Washington Post, 23 September 2007, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/09/22/AR2007092201447.html.

[9]. Ibid.

[10]. Air Force Doctrine Document (AFDD) 3-72, Nuclear Operations, 17 September 2010, 6.

[11]. Department of Defense, The Defense Science Board Permanent Task Force on Nuclear Weapons Surety, Report on the Unauthorized Movement of Nuclear Weapons (Washington, DC: Office of the Under Secretary of Defense [Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics], February 2008), 13.

[12]. United States Air Force, FY 2012 Budget Overview, 34

[13]. United States Air Force, “Air Force Global Strike Command,” http://www.af.mil/information/factsheets/factsheet.asp?id=16613 (accessed 11 June 2011).

[14]. “US Launches ‘Global Strike Command’ on 7 August,” Korean Central Broadcasting Station, 11 August 2009, in Open Source Center, KPP20090812104001, 11 June 2011.

[15]. “Russia To Create New Strike Systems In Response To US Air Force Activity,” Itar-Tass, 11 August 2009, in Open Source Center, CEP20090811950161, 11 June 2011.

[16]. Department of Defense, The Defense Science Board Permanent Task Force on Nuclear Weapons Surety, Report on the Unauthorized Movement of Nuclear Weapons (Washington, DC: Office of the Under Secretary of Defense [Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics], February 2008), 3.

[17] Department of Defense, The Defense Science Board Permanent Task Force on Nuclear Weapons Surety, Report on the Unauthorized Movement of Nuclear Weapons, 3.

[18] Ibid.

[19]. Lieutenant General Frank G. Klotz, Commander, Air Force Global Strike Command (presentation, Senate Arms Services Committee, Strategic Forces Subcommittee, Washington, DC, 17 March 2010), 7.

[20]. Air Force Doctrine Document (AFDD) 3-72, Nuclear Operations, 17 September 2010, 31.

[21]. Air Force Doctrine Document (AFDD) 1-1, Leadership and Force Development, 18 February 2006, 1.

[22] Drew, Dennis and Don Snow, Making Strategy: An Introduction to National Security Processes and Problems, Air University Press, 1988, 164.

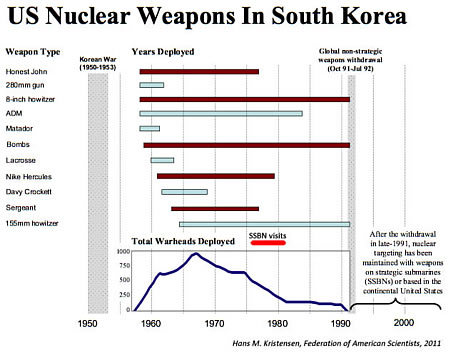

When the Boomers Went to South Korea

There are not many public pictures showing the U.S. ballistic missile submarine visits to South Korea. This one apparently shows the USS John Marshall (SSBN-611) in Chinhae in 1979. The submarine carried 16 Polaris A3 missiles with a total of 48 200-kt warheads.

.

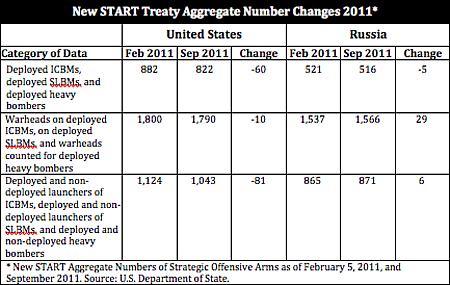

Back in the late-1970s, U.S. nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines suddenly started conducting port visits to South Korea. For a few years the boomers arrived at a steady rate, almost every month, sometimes 2-3 visits per month. Then, in 1981, the visits stopped and the boomers haven’t been back since.

At the time the visits began, the United States also had several hundred nuclear weapons deployed on land in South Korea, but the submarine visits apparently were needed to further demonstrate that the United States was prepared to defend the south against an attack from the north.

After North Korea’s nuclear tests in 2006 and 2009, shelling of South Korean territory and the sinking of one of its warships, there have been reports recently that an increasing number of South Koreans want the United States to deploy nuclear weapons in South Korea again, after the last such weapons were withdrawn in 1991. They think it is necessary to deter North Korea.

Some analysts have even suggested that the United States should develop an improved nuclear earth penetrator to better threaten North Korean deeply buried targets, an idea that was previously proposed the Bush administration but rejected by Congress.

Boomers in Chinhae

The SSBN visits to South Korea are unique; the United States normally does not send SSBNs into foreign ports. But there are exceptions. In 1963, the USS Sam Houston (SSBN-609) sailed into Izmir in Turkey on a mission to assure the Turkish government that the United States still had the nuclear capability to defend Turkey even after Jupiter missiles were withdrawn from bases in Turkey following the Cuban missile crisis. The Izmir visit was a one-time event, however, and no SSBN visited foreign ports for the next 12 years.

|

| Between December 1976 and March 1981, nine U.S. ballistic missile submarines conducted 35 port visits to South Korea |

Then, on December 19, 1976, the USS Sam Houston suddenly arrived in Chinhae, South Korea. The ship was under order to “surface in Korea for 3 days to ‘rattle the saber,” according to a former crew member. This was the first foreign port visit of a U.S. SSBN in the Pacific.

Two visits followed in 1978 but in 1979 the operations expanded with 14 visits conducted by eight SSBNs. In October that year, three SSBNs made three visits for a combined presence of 15 days.

The following year, in 1980, the number of visits expanded to 15, in June with three visits for a combined 17 days in port. In 1981, coinciding with the phase-out of the Polaris SLBM, the visits dropped to only two.

The Political Context

The 35 port visits conducted by nine SSBNs to Chinhae were a powerful message to South Korea and its potential adversaries about the U.S. nuclear capabilities in the area. But exactly what the reasons for the visits were remain unclear.

The visits took place in a complex political situation. South Korea had started a program to develop nuclear weapons technology, President Carter wanted to withdraw U.S. nuclear weapons from South Korea, and North Korea was building up its military forces backed by China and the Soviet Union.

Ironically, South Korea had started a nuclear weapons technology program in 1974 not because of doubts about the U.S. nuclear umbrella per ce, but because, according to the CIA, of doubts about the reliability of the overall U.S. security commitment. The program reportedly was terminated in 1976 after U.S. and French pressure. [See here for an insightful analysis]

At the same time, newly elected president Jimmy Carter wanted to withdraw U.S. nuclear weapons from bases in South Korea. At the time the SSBN visits began, the U.S. had approximately 500 ground-launched nuclear weapons at bases in South Korea – roughly the same number of warheads as onboard the missiles of the nine visiting SSBNs. [For a brief history of U.S. deployment of nuclear weapons in South Korea, go here]. In the end, Carter’s withdrawal didn’t happen but the land-based weapons were significantly reduced (see below).

|

| During the time of the SSBN visits, the number of U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in South Korea was reduced from roughly 500 to 150. The last were withdrawn in 1991. |

.

The SSBN visits might also have been designed to remind China about the U.S. military presence in the region, despite its defeat in Vietnam. The end of the SSBN visits to South Korea in 1981 and the phase-out of the Polaris SSBNs fleet in the Pacific coincided with China’s removal from the U.S. strategic war plan as part of the Reagan administration’s efforts to recruit China as a partner against the Soviet Union. (China was later reinstated in the war plan in 1997 by the Clinton administration.)

In September 1982, the first new Ohio-class SSBN deployed on its first patrol in the Pacific and over the next five years it was followed by seven other boats, each loaded with 24 longer-range and more accurate Trident I C-4 missiles. (All have since been upgraded to the even more capable Trident II D-5 missile). None of the Trident SSBNs have ever visited South Korea, even after the withdrawal of the last land-based nuclear weapons from the country in 1991.

Implications

The SSBN visits to South Korea are a curious but little noticed footnote in the Cold War history. More research is needed to better describe exactly why they happened, but the visits seemed intended to signal assurance to South Korea and deterrence to its adversaries.

As such the visits have potential implications for today. North Korea has since crossed the nuclear threshold, support seems to be growing in South Korea for returning U.S. nuclear weapons to the peninsula, and some argue that better nuclear capabilities are needed to deter Pyongyang.

But the visits are a reminder of the already considerable nuclear capabilities in the region that could be used to signal. Nuclear-capable bombers routinely forward deploy to Guam, and the eight SSBNs patrolling in the Pacific could surface again and visit South Korea if necessary.

|

| Nearly 30,000 U.S. troops in South Korea, large-scale conventional exercises such as the three-carrier battlegroup Valiant Shield (image) and the half-a-million-man Ulchi Freedom Guardian, as well as forward operations of nuclear-capable forces in the region provide a powerful deterrent. |

.

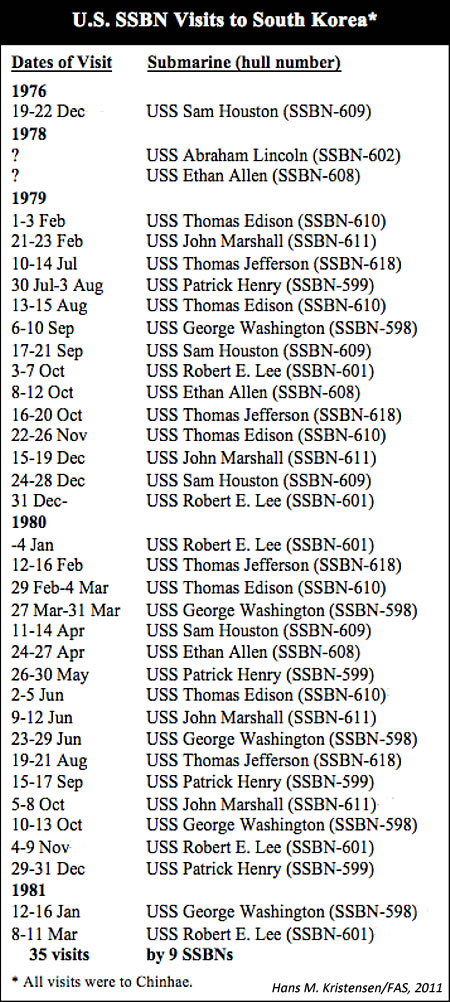

The question is whether it is necessary. The nuclear capabilities the United States operates in the Pacific region today are far more capable than in the 1970s, and the combined conventional forces of South Korea and the United States enjoy a significant advantage over North Korea’s aging conventional forces. To the extent that anything can, these forces should be sufficient to deter large-scale North Korean attacks against the south.

Indeed, Pyongyang’s obsession with the U.S. nuclear capabilities – even its misperception that Washington still deploys nuclear weapons in South Korea – strongly suggests that the current nuclear umbrella has Pyongyang’s full attention and that nuclear redeployment or nuclear bunker busters are not needed. After all, the objective is to move forward toward a denuclearization of the Korean peninsula, not return to the past.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.