New Report: Trimming Nuclear Excess

The US and Russian nuclear arms reduction process needs to be revitalized by new treaties and unilateral initiatives to reduce nuclear force levels, a new FAS report argues (click on image to download report).

By Hans M. Kristensen

Despite enormous reductions of their nuclear arsenals since the Cold War, the United States and Russia retain more than 9,100 warheads in their military stockpiles. Another 7,000 retired – but still intact – warheads are awaiting dismantlement, for a total inventory of more than 16,000 nuclear warheads.

This is more than 15 times the size of the total nuclear arsenals of all the seven other nuclear weapon states in the world – combined.

The U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals are far beyond what is needed for deterrence, with each side’s bloated force level justified only by the other’s excessive force level.

A new FAS report – Trimming Nuclear Excess: Options for Further Reductions of U.S. and Russian Nuclear Forces – describes the status and 10-year projection for U.S. and Russian nuclear forces.

The report concludes that the pace of reducing nuclear forces appears to be slowing compared with the past two decades. Both the United States and Russia appear to be more cautious about reducing further, placing more emphasis on “hedging” and reconstitution of reduced nuclear forces, and both are investing enormous sums of money in modernizing their nuclear forces over the next decade.

Even with the reductions expected over the next decade, the report concludes that the United States and Russia will continue to possess nuclear stockpiles that are many times greater than the rest of the world’s nuclear forces combined.

New initiatives are needed to regain the momentum of the nuclear arms reduction process. The New START Treaty from 2011 was an important but modest step but the two nuclear superpowers must begin negotiations on new treaties to significantly curtail their nuclear forces. Both have expressed an interest in reducing further, but little has happened.

New treaties may be preferable, but reaching agreement on the complex inter-connected issues ranging from nuclear weapons to missile defense and conventional forces may be unlikely to produce results in the short term (not least given the current political climate in the U.S. Congress). While the world waits, the excess nuclear forces levels and outdated planning principles continue to fuel justifications for retaining large force levels and new modernizations in both the United States and Russia.

To break the stalemate and reenergize the arms reductions process, in addition to pursuing treaty-based agreements, the report argues, unilateral steps can and should be taken in the short term to trim the most obvious fat from the nuclear arsenals. The report includes 32 specific recommendations for reducing unnecessary and counterproductive U.S. and Russian nuclear force levels unilaterally and bilaterally.

Full report: Trimming Nuclear Excess

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Detailed Data For US Nuclear Forces Counted Under New START Treaty

|

| Air Force personnel perform New START Treaty inspection training on a Minuteman III ICBM payload section at Minot AFB in 2011. Nearly two years into the treaty, there have been few reductions of U.S. deployed strategic nuclear forces. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. State Department today released the full (unclassified) and detailed aggregate data categories for U.S. strategic nuclear forces as counted under the New START treaty. This is the forth batch of data published since the treaty entered into force in February 2011.

Although the new data shows a reduction compared with previous releases, a closer reading of the documents indicates that changes are due to adjustments of delivery vehicles in overhaul at any given time and elimination on so-called phantom platforms, that is aircraft that carry equipment that make them accountable under the treaty even though they are no longer assigned a nuclear mission. Actual reduction of deployed nuclear delivery vehicles has yet to occur.

The joint U.S.-Russian aggregate data and the full U.S. categories of data are released at different times and not all information is made readily available on the Internet. Therefore, a full compilation of the September data is made available here.

Overall U.S. Posture

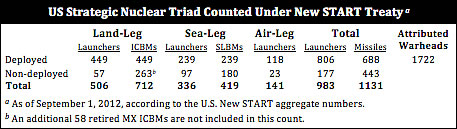

The data attributes 1,722 warheads to 806 deployed ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers as of September 1, 2012. This is a reduction of 15 deployed warheads and 6 deployed delivery vehicles compared with the previous data set from March 2012.

A large number of non-deployed missiles and launchers that could be deployed are not attributed warheads.

The data shows that the United States will have to eliminate 234 launchers over the next six years to be in compliance with the treaty limit of 800 deployed and non-deployed launchers by 2018. Fifty-six of these will come from reducing the number of launch tubes per SSBN from 24 to 20, roughly 80 from stripping B-52Gs and nearly half of the B-52Hs of their nuclear capability, and destroying about 100 old ICBM silos.

The released data does not contain a breakdown of how the 1,722 deployed warheads are distributed across the three legs of the Triad. But because the bomber number is disclosed and each bomber counts as one warhead, and because 450-500 warheads remain on the ICBMs (downloading to one warhead per ICBM was scheduled to resume in 2012), it appears that the deployed SLBMs carry 1,104 to 1,154 warheads, or more than two-thirds of the total number of warheads counted by New START.

Just to remind readers: the New START numbers do not represent the total number of nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal – only about a third. The total military stockpile is just under 5,000 warheads, with several thousand additional retired (but still intact) warheads awaiting dismantlement. For an overview, see this article.

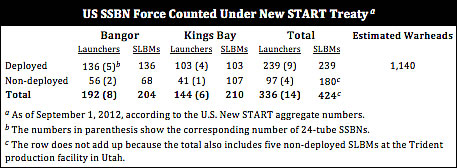

Ballistic Missile Submarines

The New START data shows that the United States as of September 1, 2012, had 239 Trident II SLBMs onboard its SSBN fleet, a reduction of three compared with March 2012. That is only enough to fill nine SSBNs to capacity, but it doesn’t reflect an actual reduction of SLBMs or SSBNs but a fluctuation in the number of SLBMs onboard SSBNs during overhaul. Each SSBN has 24 missile tubes for a maximum loadout of 288 missiles (48 tubes on two SSBNs in overhaul are not counted), but at the time of the New START count it appears that two or three of the 14 SSBNs were empty (including the two in refueling overhaul) and two or three were only partially loaded (in missile loadout).

It is widely assumed that 12 out of 14 SSBNs normally are deployable, but the various sets of aggregate data all indicate that the force ready for deployment at any given time may be closer to 10. This ratio can fluctuate significantly and in average 64 percent (8-9) of the SSBNs are at sea with roughly 920 warheads. Up to five of those subs are on alert with 120 missiles carrying an estimated 540 warheads – enough to obliterate every major city on the face of the earth.

Of the eight SSBNs based at Bangor (Kitsap) Submarine Base in Washington, the data indicates that three were out of commission on September 1, 2012: one had empty missile tubes (possibly because it was in dry dock) and two others were only partially loaded. This means that five SSBNs from the base were fully loaded and probably deployed with 120 Trident II D5 missiles carrying some 540 warheads at the time of the New START count.

For the six SSBNs based at Kings Bay Submarine Base in Georgia, the New START data shows that 103 missiles were counted as deployed on September 1, 2012. That number is enough to load four SSBNs, with two other SSBNs only partially loaded. The four deployed SSBNs probably carried 96 Trident II SLBMs with some 430 warheads.

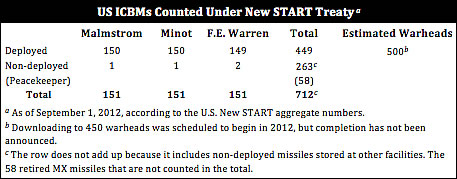

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles

The New START data shows that the United States deployed 449 Minuteman III ICBMs as of September 1, 2012, the same number that was deployed in March 2012. Most were at the three launch bases, but a significant number (321) were at maintenance and storage facilities in Utah. That included 58 MX Peacekeeper ICBMs retired in 2003-2005 but which have not been destroyed.

The New START data does not show how many warheads were loaded on the 449 deployed ICBMs. Downloading to single warhead loading was scheduled to begin in FY2012, but a completion has not been announced. The warhead number is 450-500. The 2010 NPR decided to “de-MIRV” the ICBM force, an unfortunately choice of words because the force will retain the capability to re-MIRV if necessary.

Heavy Bombers

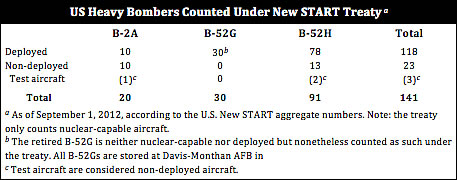

The New START data shows that the U.S. Air Force possessed 141 B-2 and B-52 nuclear-capable heavy bombers as of September 1, 2012. Of these, 118 were counted as deployed, a reduction of four compared with March 2012. The data shows that only half of the B-2 stealth bombers are deployed.

Unfortunately the bomber data is misleading because it counts 30 retired B-52G bombers stored at Davis-Monthan AFB in Arizona as “deployed” at Minot AFB in North Dakota. The mischaracterization is the result of a counting rule in the treaty, which says that bombers can only be deployed at certain bases. As a result, the 30 retired B-52Gs are listed in the treaty as deployed at Minot AFB – even though there are no B-52Gs at that base. According to Air Force Global Strike Command, “There are no B-52Gs at Minot AFB, N.D…In accordance with accounting requirements, we have them assigned to Minot and as visiting Davis-Monthan.” The actual number of deployed heavy bombers should more accurately be listed as 88 B-2A and B-52H, with another 53 non-deployed (including the 30 at Davis Monthan AFB.

All of these bombers carry equipment that makes them accountable under New START, but only a portion of them are actually involved in the nuclear mission. Of the 20 B-2s and 91 B-52Hs in the Air Force inventory, 18 and 76, respectively, are nuclear-capable, but only 60 of those (16 B-2s and 44 B-52Hs) are thought to be nuclear tasked at any given time. None of the aircraft are loaded with nuclear weapons under normal circumstances but are attributed a fake count under New START of only one nuclear weapon per aircraft even though each B-2 and B-52H can carry up to 16 and 20 nuclear weapons, respectively. Roughly 1,000 nuclear bombs and cruise missiles are in storage for use by these bombers. Stripping excess B-52Hs and the remaining B-52Gs of their nuclear equipment will be necessary to get down to 60 counted nuclear bombers by 2018.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The New START data released by the State Department continues the decision made last year to release the full U.S. unclassified aggregate numbers, an important policy that benefits international nuclear transparency and counters misunderstandings and rumors.

The latest data set shows that the U.S. reduction of deployed strategic nuclear forces over the past six months has been very modest: 6 delivery vehicles and 15 warheads. The reduction is so modest that it probably reflects fluctuations in the number of deployed weapon systems in overhaul at any given time. Indeed, while there have been some reductions of non-deployed and retired weapon systems, there is no indication from the new data that the United States has yet begun to reduce its deployed strategic nuclear forces under the New START treaty.

Those reductions will come slowly over the next five-six years to meet the treaty limits of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads and 800 deployed and non-deployed strategic delivery vehicles by February 2018. But almost two years after the New START treaty entered into force, it is clear that the Pentagon is not in a hurry to implement it.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

B61-12: Contract Signed for Improving Precision of Nuclear Bomb

|

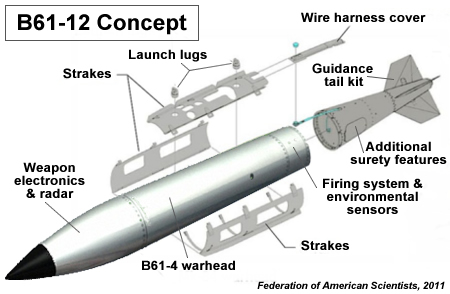

| The first contract was signed yesterday for the development of the guided tail kit that will increase the accuracy of the B61 nuclear bomb. This conceptual drawing illustrates the principle of adding a guided tail kit assembly to the gravity bomb. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. Air Force’s new precision-guided nuclear bomb B61-12 moved one step closer to reality yesterday with the Pentagon issuing a $178.6 million contract to Boeing. The contract covers Phase 1 (Engineering and Manufacturing Development) to be completed in October 2015. The contract also includes options for a Phase 2 and production.

In a statement on the contract, Boeing said that the tail kit program “further expands Boeing’s Direct Attack weapons portfolio” and that the precision-guided B61-12 would “effectively upgrade a vital deterrent capability.”

The expensive B61-12 project will use the 50-kiloton warhead from the B61-4 gravity bomb but add the tail kit to increase the accuracy and boost the target kill capability to one similar to the 360-kiloton strategic B61-7 bomb.

Because the B61-4 warhead also has selective lower-yield options, the tail kit will also allow war planners to select lower yields to strike targets that today require higher yields, thereby reducing radioactive fallout of an attack. The Air Force tried in 1994 to get a precision-guided low-yield nuclear bomb (PLYWD), but Congress rejected it because of concern that it would lead to more useable nuclear weapons. Now the Air Force get’s a precision-guided nuclear bomb anyway.

The U.S. Air Force plans to deploy some of the B61-12s in Europe late in the decade for delivery by F-15E, F-16, F-35 and Tornado aircraft to replace the B61-4s currently deployed in Europe. The improved accuracy will increase the capability of NATO’s nuclear posture, which will be further enhanced by delivery of the B61-12 on the stealthy F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

Increasing the capability of NATO’s nuclear posture contradicts the Deterrence and Defense Posture Review (DDPR) adopted in May 2012, which concluded that “the Alliance’s nuclear force posture currently meets the criteria for an effective deterrence and defense posture.” Moreover, improving NATO’s nuclear capabilities undercuts efforts to persuade Russia to decrease its non-strategic nuclear forces.

Instead of improving nuclear capabilities and wasting scarce resources, the Obama administration must re-take the initiative to reduce the role of nuclear weapons and work with NATO to withdraw the nuclear weapons from Europe.

See also: Modernizing NATO’s Nuclear Forces: Implications for the Alliance’s Defense Posture and Arms Control

And: Previous blogs about NATO and nuclear weapons

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Modernization Talk at BASIC Panel

|

| Linton Brooks and I discussed nuclear modernization at a November 13 panel organized by BASIC. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

BASIC invited me to discuss nuclear weapons modernization with Linton Brooks at a Strategic Dialogue panel held at the Capitol Hill Club on November 13, 2012. We’re still waiting for the official transcript, but BASIC has a rough recording and my prepared remarks are available here. [Update: all material, including transcript with questions/answers, is available from BASIC].

In my talk, I argued that the Obama administration’s nuclear arms control profile is at risk of being overshadowed by extensive nuclear weapons modernization plans, and that the approach must be adjusted to ensure that efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons and put and end to Cold War thinking are clearly visible as being the priority of U.S. nuclear policy.

The administration has nearly completed a strategic review of nuclear targeting and alert requirements to identify additional reductions of nuclear forces. Release of the findings was delayed by the election, but the administration now needs to use the review to reinvigorate the nuclear arms reduction agenda that has slowed with the slow implementation of the modest New START Treaty and the disappointing “nuclear status quo” decision of the NATO Chicago Summit.

Germany and B61 Nuclear Bomb Modernization

|

| During a recent visit to Germany I did an interview with the Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk magazine FAKT on the status of the B61 nuclear bomb modernization. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Last week, I was in Berlin to testify before the Disarmament Subcommittee of the German Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee on the future of the U.S. B61 nuclear bombs in Europe (see my prepared remarks and fact sheet).

One of the B61 bombs currently deployed in Europe is scheduled for an upgrade to extend its life and add new military capabilities and use-control features. The work has hardly begun but the project is already behind schedule and the cost has increased by more than 150 percent in two years, from $4 billion to $10.4 billion. The subcommittee wanted to know if the program is in trouble. I said I believe it certainly is.

The German television magazine FAKT did an interview (article; video) with me and it came as somewhat of a surprise to them that the B61 life-extension will not install a fire-resistant pit to improve the safety of the weapon. They also tried to get German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle on the program. The policy of the German government coalition is to try to have nuclear weapons removed from Germany and Westerwelle has publicly promoted this position clearly in the past. This time he did not want to talk, however, as journalists and camera-teams chased him down the hallway. He may have gotten shell-shocked by the pushback from the old nuclear guard in NATO.

|

| German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle did not want to talk with MDR FAKT about withdrawal of US nuclear weapons. |

.

Although NATO recently determined that the current nuclear posture in Europe meets the Alliance’s deterrence and defense needs, NATO has decided – with German backing – to introduce a new precision-guided nuclear bomb in Europe with increased military capabilities at the end of the this decade for delivery by a new stealthy aircraft.

During my briefing to the foreign affairs committee I urged Germany to continue to push for a withdrawal. Otherwise it will have to explain to the German public why it has decided instead to support deployment of precision-guided nuclear bombs on stealth-delivered aircraft in Europe. The two positions will be hard to square.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Cuban Missile Crisis: Nuclear Order of Battle

|

| At the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis blockade, unknown to the United States, the Soviet Union already had short-range nuclear weapons on the island, such as this FKR-1 cruise missile, that would most likely have been used against a U.S. invasion. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris

Fifty years ago the world held its breath for a few weeks as the United States and the Soviet Union teetered on the brink of nuclear war in response to the Soviet deployment of medium-range nuclear missiles in Cuba.

The United States imposed a military blockade around Cuba to keep more Soviet weapons out and prepared to invade the island if necessary. As nuclear-armed warships sparred to enforce and challenge the blockade, a few good men made momentous efforts and decisions that prevented use of nuclear weapons and eventually defused the crisis.

What the Kennedy administration did not know, however, was that the Soviet Union had 158 nuclear warheads of five types already in Cuba by the time of the blockade. This included nearly 100 warheads for short-range ballistic missiles and cruise missiles. If the invasion had been launched, as the military recommended but the White House fortunately decided against, it would most likely have triggered Soviet use of those short-range nuclear weapons against the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo and at amphibious forces storming the Cuban beaches. That, in turn, would have triggered wider use of nuclear forces.

In our latest Nuclear Notebook – The Cuban Missile Crisis: a nuclear order of battle, October and November 1962 – we outline the nuclear order of battle that the United States and the Soviet Union had at their disposal. At the peak of the crisis, the United States had some 3,500 nuclear weapons ready to use on command, while the Soviet Union had perhaps 300-500.

The Cuban Missile Crisis order of battle of useable weapons represented only a small portion of the total inventories of nuclear warheads the United States and Russia possessed at the time. Illustrating its enormous numerical nuclear superiority, the U.S. nuclear stockpile in 1962 included more than 25,500 warheads (mostly for battlefield weapons). The Soviet Union had about 3,350.

For all the lessons the Cuban Missile Crisis taught the world about nuclear dangers, it also left some enduring legacies and challenges that are still confronting the world today. Among other things, the crisis fueled a build-up of quick-reaction nuclear weapons that could more effectively hold a risk the other side’s nuclear forces in a wider range of different strike scenarios.

Today, 50 years later and more than 20 years after the Cold War ended, the United States and Russia still have more than 10,000 nuclear weapons combined. Of those, an estimated 1,800 nuclear warheads are on alert on top of long-range ballistic missiles, ready to be launched on short notice to inflict unimaginable devastation on each other. The best way to honor the Cuban Missile Crisis would be to finally end that legacy and take nuclear weapons off alert.

Nuclear Notebook: The Cuban Missile Crisis: A nuclear order of battle, October and November 1962

NATO: Nuclear Transparency Begins At Home

|

| What’s wrong with this picture? Despite NATO’s call for greater nuclear transparency, old-fashioned nuclear secrecy prevents media access to the Nuclear Planning Group. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Less than six months after NATO’s Deterrence and Defense Posture Review (DDPR) adopted at the Chicago Summit called for greater transparency of non-strategic nuclear force postures in Europe, the agenda for the NATO defense minister get-together in Brussels this week listed the Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) meeting with the usual constraint: “no media opportunity.”

Why should the news media not have access to the NPG meeting just like they have access to other meetings discussing NATO security issues? After all, the high stakes that justified nuclear secrecy in the past disappeared with the demise of the Soviet Union, no urgent military mission is (publicly) attributed to the remaining nearly 200 U.S. nuclear bombs left in Europe, and NATO now officially advocates greater nuclear transparency.

Whatever the reason, the “no media opportunity” is symbolic of the old-fashioned secrecy that continues to constrain NATO nuclear policy discussions. The nuclear planners are insulated deep within the alliance with little or no public scrutiny. Even for NATO officials, tradition, past political statements, and turf can make it difficult to ascertain and question the rationales behind the nuclear posture.

The DDPR determined “that the Alliance’s nuclear force posture currently meets the criteria for an effective deterrence and defense posture.” The reasons for that conclusion remain elusive and the news media should have access to the NPG meeting to ask the questions. Not least because the conclusion is now resulting in significant modernization of NATO’s nuclear forces at considerable cost to the Alliance and some of its member countries. Another potential cost is how it will affect relations with Russia.

If NATO wants to increase nuclear transparency, it should and could break with old-fashioned nuclear secrecy and disclose the broad outlines of its non-strategic nuclear deployment in Europe. It is already widely known and NATO’s nuclear members are already transparent about the broad outlines of their strategic nuclear forces – those that unlike the non-strategic weapons in Europe are actually tasked to provide the ultimate security guarantee to the Allies.

Rather than limiting nuclear transparency efforts to prolonged negotiations for what’s likely to be small incremental steps that essentially surrender the agenda to hardliners in Moscow, unilateral disclosure of NATO’s non-strategic posture would jump-start the process, put pressure on Russia to follow suit, and be consistent with the already considerable transparency of NATO’s strategic forces.

See also: Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons, FAS, May 2012.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

DOD: Strategic Stability Not Threatened Even by Greater Russian Nuclear Forces

A Department of Defense (DOD) report on Russian nuclear forces, conducted in coordination with the Director of National Intelligence and sent to Congress in May 2012, concludes that even the most worst-case scenario of a Russian surprise disarming first strike against the United States would have “little to no effect” on the U.S. ability to retaliate with a devastating strike against Russia.

I know, even thinking about scenarios such as this sounds like an echo from the Cold War, but the Obama administration has actually come under attack from some for considering further reductions of U.S. nuclear forces when Russia and others are modernizing their forces. The point would be, presumably, that reducing while others are modernizing would somehow give them an advantage over the United States.

But the DOD report concludes that Russia “would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty” (emphasis added).

The conclusions are important because the report come after Vladimir Putin earlier this year announced plans to produce “over 400” new nuclear missiles during the next decade. Putin’s plan follows the Obama administration’s plan to spend more than $200 billion over the next decade to modernize U.S. strategic forces and weapons factories.

The conclusions may also hint at some of the findings of the Obama administration’s ongoing (but delayed and secret) review of U.S. nuclear targeting policy.

No Effects on Strategic Stability

The DOD report – Report on the Strategic Nuclear Forces of the Russian Federation Pursuant to Section 1240 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 – was obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. It describes the U.S. intelligence community’s projection for the likely development of Russian nuclear forces through 2017 and 2022, the timelines of the New START Treaty, and possible implications for U.S. national security and strategic stability.

Much of the report’s content was deleted before release – including general and widely reported factual information about Russian nuclear weapons systems that is not classified. But the important concluding section that describes the effects of possible shifts in the number and composition of Russian nuclear forces on strategic stability was released in its entirety.

|

| As long as a sufficient number of U.S. SSBNs are at sea, strategic stability is intact even with significantly greater Russian nuclear forces, the DOD says. |

.

The section “Effects on Strategic Stability” begins by defining that stability in the strategic nuclear relationship between the United States and the Russian Federation depends upon the assured capability of each side to deliver a sufficient number of nuclear warheads to inflict unacceptable damage on the other side, even with an opponent attempting a disarming first strike.

Consequently, the report concludes, “the only Russian shift in its nuclear forces that could undermine the basic framework of mutual deterrence that exists between the United States and the Russian Federation is a scenario that enables Russia to deny the United States the assured ability to respond against a substantial number of highly valued Russian targets following a Russian attempt at a disarming first strike” (emphasis added). The DOD concludes that such a first strike scenario “will most likely not occur.”

But even if it did and Russia deployed additional strategic warheads to conduct a disarming first strike, even significantly above the New START Treaty limits, DOD concludes that it “would have little to no effects on the U.S. assured second-strike capabilities that underwrite our strategic deterrence posture” (emphasis added).

In fact, the DOD report states, the “Russian Federation…would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty, primarily because of the inherent survivability of the planned U.S. Strategic force structure, particularly the OHIO-class ballistic missile submarines, a number of which are at sea at any given time.” (more…)

New START Data Released: Nuclear Flatlining

|

| Reductions under the New START Treaty have gotten off to a very slow start |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

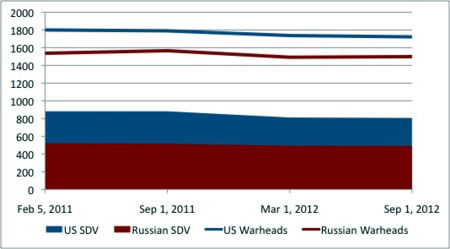

More than a year and a half after the New START Treaty between the United States and Russia entered into force on January 5, 2011, one thing is clear: they are not in a hurry to reduce their nuclear forces.

Earlier today the fourth batch of so-called aggregate data was released by the U.S. State Department. It shows that the United States and Russia since January 5, 2011, have reduced their accountable deployed strategic delivery vehicles by 76 and 30, respectively. Parts of those numbers are fluctuations due to delivery platforms entering or leaving maintenance. The U.S. number obscures the fact that it involves destruction of some of three dozen old B-52G bombers that still count as deployed even though they were retired two decades ago. The Russian number obscures replacement of older missiles with new ones on a less than one-for-one basis.

During the same period, the United States and Russia have reduced their number of accountable deployed strategic warheads by 78 and 38, respectively. Much of these numbers are fluctuations due to delivery platform maintenance and it is not clear that either country has made any explicit warhead reductions yet under the treaty. In any case, 38-78 warheads don’t amount to much out of the approximately 5,000 nuclear warheads the two countries retain in each of their respective nuclear stockpiles.

With 1,499 accountable warheads on 491 deployed strategic delivery vehicles, Russia is already well below the treaty limit and is only required to scrap 84 non-deployed delivery vehicles before the treaty enters into effect in six years on February 5, 2018.

The United States is well above the Russian force level, with 1,722 accountable warheads on 806 deployed strategic delivery vehicles. Over the next six years, it will have to remove 96 deployed delivery vehicles with 172 accountable warheads, and scrap 234 non-deployed platforms.

The U.S. posture appears even more bloated when considering that the Pentagon retains a large reserve of non-deployed warheads intended to increase the loading on the missiles in a crisis.

Russia does not have such an upload capacity. And even President Putin’s promised increased missile production over the next decade will not be able to offset the expected continued decline in the Russian triad that will result form the retirement of four old ICBM and SLBM systems over the next decade-plus.

This nuclear force structure asymmetry must be addressed in the next round of U.S.-Russian strategic nuclear talks. But even before such talks get underway, reductions can and should be made. There is simply no reason for the Pentagon to stretch reductions of excess nuclear forces through 2017. Forces slated for retirement should be removed from service now and the reserve of upload warheads should be trimmed. Doing so is good planning. Not only is it expensive (and stupid) to keep more nuclear forces than needed. But a bloated force structure provides unhelpful justification for those in the Russian establishment who argue for increasing missile production and deploying new missiles.

See previous analysis of New START data:

1. Second Batch of New START Data Released

2. US Releases Full New START Data

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

In Warming US-NZ Relations, Outdated Nuclear Policy Remains Unnecessary Irritant

|

| U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta meets with New Zealand Defense Minister Jonathan Coleman, in a first step to normalize relations between the two countries nearly 30 years after the U.S. punished New Zealand for its ban on nuclear weapons. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Hat tip to the Obama administration for doing the right and honorable thing: breaking with outdated Reagan administration policy and sending Defense Secretary Leon Panetta to New Zealand and ease restrictions on New Zealand naval visits to U.S. military bases.

The move shows that Washington after nearly 30 years of punishing the small South Pacific nation for its ban against nuclear weapons may finally have come to its senses and decided to end the vendetta in the interest of more important issues.

The New Zealand defense minister made it quite clear that the move does not mean a change to New Zealand’s policy of denying nuclear warships access to its harbors. “New Zealand has made it very clear that the policy remains unchanged and will remain unchanged.”

Whether (or how soon) the move will result in a resumption of U.S. naval visits to New Zealand remains to be seen. The U.S. Navy still has two policies that would appear to prevent this. One is a “one-fleet” policy that holds that if any U.S. ships are restricted from an area, it will refrain from sending any ships there. The other is the Neither Confirm Nor Deny Policy (NCND), which prohibits disclosing if a warship carries nuclear weapons or not, a leftover from the Cold War when stuff like that was important.

These policies leave an irritant in place that doesn’t need to be there. It seems that both countries can makes modifications to their policies to allow normal military relations to resume.

Cold War Policy in Need of Change

Panetta’s visit to New Zealand is the first by a U.S. defense secretary in 30 years since the gong ho nuclear policy of the Reagan administration threw New Zealand out of the Australia-New Zealand-US (ANZUS) alliance for refusing to accept visits by nuclear-armed warships to its ports. The treatment of New Zealand was intended as a warning to countries not to dare enforce their non-nuclear policies. As former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Leslie Gelb diplomatically put it in the New York Times at the time: “Unless we hold our allies’ feet to the fire over ship visits and nuclear deployments, one will run away and then the next.”

At the core of the dispute is the so-called Neither Confirm Nor Deny Policy (NCND), according to which the U.S. will not reveal – directly or indirectly – whether nuclear weapons are present on a warship, an aircraft, or on a base. The policy emerged in the 1950s as a way to counter anti-nuclear and left wing demonstrations in Europe during port visits. Later it was re-coined as a way to protect ships against terrorist attacks and to complicate Soviet military planning. Spin aside, the central objective was always to ensure unfettered access for U.S. warships to foreign ports – no matter the nuclear policy of the host country. (For a chronology of the NCND policy, see: The Neither Confirm Nor Deny Policy: Nuclear Diplomacy at Work).

During the Cold War, U.S. warships bristled with non-strategic nuclear weapons. Bombs, anti-submarine rockets, air-defense missiles, land-attack cruise missiles, depth bombs and torpedoes were continuously at sea onboard aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, frigates, supply ships and attack submarines. Every single day some of them sailed into foreign ports around the world. The deployment war part of a global posture against the Soviet Union, which also deployed non-strategic nuclear weapons on its fleet (Britain and France had similar postures).

The NCND was a brilliant diplomatic arrangement. The host country could have whatever nuclear policy it wanted and the United States could continue to visit its ports with nuclear-armed warships. The only problem with the NCND was that it put allied governments with non-nuclear policies in an unreasonable dilemma: one, reject the visit or ask the United States to deny that the ship carried nuclear weapons; or, two, turn a blind eye and accept that nuclear weapons come in on warships once in a while.

That dilemma is the dirty little secret of the NCND: It required not just that the United States was ambiguous about the weapons loadout, but also that the host country accepted ambiguity about the armament. For the host country to accept ambiguity was, of course, incompatible with a policy that prohibited nuclear weapons on its territory.

New Zealand was the first allied country that refused to accept that ambiguity. It did so in 1984 by adopting a law that prohibited access for nuclear-armed and nuclear-propelled vessels. The law did not demand that the United States confirm or deny whether there were nuclear weapons on the ships (that is a widespread misperception); it only required the New Zealand government in its own right to make a determination and announce its decision. But such an announcement was incompatible with the NCND, which required the host country to keep quiet about what it knew.

|

| The USS Buchanan (DDG-14) arrives in Sydney, Australia, in March 1985 after it was barred from visiting New Zealand. |

When the U.S. wanted to send a warship to New Zealand in the spring of 1985, it could have sent a warship that was not nuclear-capable (in fact, the News Zealand government asked the U.S. to do so, but it refused). But that would not have fully tested New Zealand’s adherence to the NCND. So the Reagan administration decided to send the guided missile destroyer USS Buchannan (DDG-14), which was equipped to carry nuclear ASROC missiles. This visit was to be followed by several other ships, some of which most likely carried nuclear weapons.

The New Zealand government turned down the request and the Reagan administration retaliated by throwing New Zealand out of the ANZUS alliance, curtailing intelligence sharing, and prohibiting New Zealand warships from visiting U.S. military and Cost Guard facilities in the region. In effect, the Reagan administration chose to sacrifice an ally in a part of the world where the military implications were limited to prevent the anti-nuclear “allergy” from spreading to other more vital parts of the world.

The strategy failed. In 1988, the nuclear port visits issue triggered an election in Denmark, and in 1990 the Swedish governing party decided to enforce Sweden’s ban against nuclear weapons on its territory after a study determined that U.S. warships routinely carried nuclear weapons into Swedish ports despite the ban.

Instead of a tool for protecting nuclear warships and ensuring allied security, the NCND policy became a lightening rod for political controversy and soured relations with U.S. allies all over the world. Whenever a nuclear-capable warship sailed into a foreign port on a “goodwill visit,” the thorny issue of whether it carried nuclear weapons and the host government being seen as turning a blind eye to violations of its own non-nuclear policy overshadowed the goodwill the U.S. and the host government were trying to demonstrate.

Today the policy continues even though it is hopelessly outdated and counterproductive. All non-strategic nuclear weapons were removed from U.S. surface ships and attack submarines by the first Bush administration in 1992 – effectively rendering the nuclear port visit issue moot. Moreover, the Clinton administration decided in 1994 to denuclearize all U.S. surface ships. The only remaining non-strategic naval nuclear weapon – the Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N) – has been stored on land since 1992 and is now being scrapped. (Russia has also offloaded its naval non-strategic nuclear weapons and Britain has completely eliminated its inventory.)

Restoration of Normal Relations is Possible

There is nothing that prevents restoration of normal U.S.-New Zealand military relations. Yet even though the non-strategic nuclear weapons have been offloaded and the U.S. surface fleet denuclearized, there are still Cold War warriors inside the bureaucracies who argue that it is necessary to maintain ambiguity about what U.S. warships carry and that no warship should sail where others are rejected.

Likewise, given that the U.S. surface fleet has been denuclearized and the last non-strategic naval nuclear weapon is being retired, there is no problem in the New Zealand government ascertaining – even publicly – that visiting U.S. warships do not carry nuclear weapons.

The policies that required nuclear ambiguity for warship visits to New Zealand are unnecessary and counterproductive and should be abolished. Hopefully they will not prevail for long. It is only a matter of time before U.S. warships begin visiting New Zealand again and Panetta must order the navy to stop pretending ambiguity where there is none: U.S. warships no longer carry nuclear weapons.

In the meantime, the U.S. embassy in Wellington might want to update its fact sheet on New Zealand-U.S. relations, which doesn’t seem to have caught up with Panetta’s visit:

“New Zealand’s legislation prohibiting visits of nuclear-powered ships continues to preclude a bilateral security alliance with the U.S. The legislation enjoys broad public and political support in New Zealand. The United States would welcome New Zealand’s reassessment of its legislation to permit that country’s return to full ANZUS cooperation.” (Emphasis added).

I think that ship has sailed.

B61-12: NNSA’s Gold-Plated Nuclear Bomb Project

Escalating cost estimates for the B61 Life- Extension Program threaten to make the new B61-12 bomb the most expensive ever.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The disclosure during yesterday’s Senate Appropriations Subcommittee hearing that the cost of the B61 Life Extension Program (LEP) is significantly greater that even the most recent cost overruns calls into question the ability of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) to manage the program and should call into question the B61 LEP itself.

If these cost overruns were in the private sector, heads would roll and the program would probably be canceled.

At the hearing yesterday, Senator Dianne Feinstein revealed that NNSA recently told her that the $4 billion cost estimate they provided in the FY2011 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan was too low and that they would need $4 billion more to complete the program. Two months ago I reported that the cost had increased to $6 billion.

NNSA’s new cost estimate is already being challenged, this time by the Pentagon’s Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) office, which only a few days ago increased the estimate by another $2 billion to a whopping $10 billion.

But get this: the already too high B61 LEP cost estimate does not include other pricy elements of the B61 modernization program. In addition to the LEP itself comes a new guided tail kit assembly that the Air Force is developing to increase the accuracy of the B61. The cost estimate for that tail kit has recently increased by 50 percent from $800 million to $1.2 billion.

Add to that the cost of equipping the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter with the capability to carry the new weapons, recently estimated at around $340 million. If the LEP and tail kit increases mentioned above are any indication, however, then the cost of equipping the F-35 with nuclear capability is also likely to increase.

The escalating costs may eventually make the B61 LEP the most expensive nuclear weapons program (per warhead unit) in the U.S. arsenal. Already the projected B61 LEP cost far exceeds the cost of the W76 LEP, which probably involves three times as many warheads as will produced by the B61 LEP. As Nick Roth points out, the new $10 billion estimate is equivalent to two-thirds of what NNSA planned to spend on life extending all the other warhead types in the US arsenal over the next twenty years!

The precise number of B61-12 planned is still a secret. My take currently is around 400. If so, that would mean each B61-12 bomb would cost $28 million (including cost of tail kit).

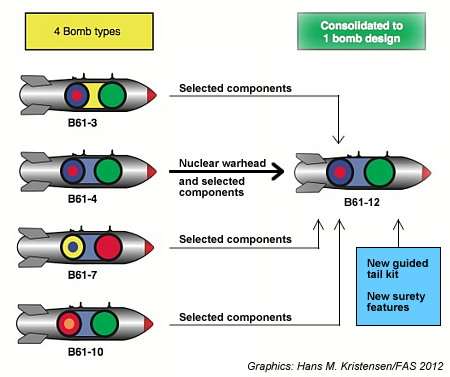

Because of the way the B61 LEP has been presented, many have the impression that the program will life-extend all four versions of the B61. In reality, only one of the four versions will be life-extended: the B61-4. It may cannibalize components from the other three (B61-3/7/10), but the heart of the new B61-12 is the B61-4 nuclear explosive package. Instead of the simple chart that STRATCOM has been circulating, the following chart more accurately illustrates the process:

Rather than a B61 life-extension program that consolidates four bombs into one, the B61 LEP should more accurately be described as a life-extension of the B61-4 that incorporates selected non-nuclear components from three other B61 versions that will be retired with new surety features and a new guided tail kit assembly.

Implications and Recommendations.

The fact that the B61-12 will use the B61-4 nuclear explosive package obviously limits the number of B61-12s that can be built to the number of B61-4 that were originally produced. That number is about 660. But most of those have been retired and only about 200 are thought to be left in the DOD stockpile. If B61-12 production is to exceed 200, then it would have to also use warheads from retired B61-4s. Given that the B61-12 will not be carried on the B-52 bomber, that B-2 bombers are probably not allocated a maximum load of weapons (they also carry others), and that the stockpile in Europe is likely to decrease within the next decade, it seems reasonable to assume a B61-12 stockpile of around 400 weapons. But the number is secret – not because it matters to national security but because it is nuclear.

The escalating cost of the B61 LEP adds to NNSA’s abysmal record of underestimating costs of nuclear weapons programs. It follows enormous budget overruns of the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement – Nuclear Facility (CMRR-NF) at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, and the Uranium Processing Facility (UPF) at the Y-12 National Security Complex at Oak Ridge in Tennessee.

As mentioned above, if these cost overruns happened in the private sector, heads would roll and the program would probably be canceled.

Apart from poor planning, the B61 LEP cost escalation is probably also fueled by planners that appear to be drunk on promises of increased nuclear funding and political commitments to nuclear modernization. The result is an overly ambitious program that instead of doing basic life-extension of existing designs is trying to add exotic features and components to the weapon that was originally tested. And the planned B61-12 is not even the most ambitious version the planners had asked for (they were not allowed to add multi-point safety and optical firing sets), which would have been even more expensive.

If poor planning is not the reason, then NNSA must be working under the assumption that costs should be underestimated when seeking initial program approval from Congress because the taxpayers will have to pay for the cost increase later on anyway. To her credit, Senator Feinstein is pushing for greater program control and told Aviation Week that the cost escalation will trigger additional congressional scrutiny. “We have to find a way to stop this from happening. …We’ve asked that we receive monthly reports, that one person be put in charge. … The purpose of that is to make people solve problems quickly, before they are left and they just continue to grow.”

The B61 LEP is not the only or necessarily most complex LEP on the horizon. NNSA and DOD are already planning the W78 LEP and envision building a “common” warhead that can be used on both ICBMs and SLBMs. Such a warhead is not currently in the stockpile. Although the design is still being worked out, it could combine W78 and W88 features and use a plutonium pit from a third warhead – the W87. If you’re worried about B61 LEP costs, just wait for the W78 LEP! Is Congress prepared to authorize $10 billion-plus per exotic LEP versus more basic LEPs?

But apart from money, the escalating B61 LEP costs must also raise questions about the importance of the mission. While the strategic mission on the B-2 strategic bomber is probably not in doubt, the non-strategic mission certainly should be. Under current plans, the B61-12 will be fitted onto four tactical aircraft – F-15E Strike Eagle, F-16 Falcon, F-35A Lightning and PA-200 Tornado. There are no important or urgent threats that require the United States to equip all these tactical aircraft with the new bomb. But the modernization will increase the military capability of NATO’s nuclear posture, not exactly in sync with the pledges from the White House and NATO to reduce the role of nuclear weapons and not increase military capabilities during LEPs.

And the few NATO officials that have either misunderstood their security requirements or been lobbied by nuclear cold warriors to support continued deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe need to be debriefed – or asked to pay their share. That would certainly end the deployment quickly.

Whatever the best way forward, the U.S. should phase out its remaining non-strategic nuclear weapons, delay and redesign the B61 LEP, and focus its resources on maintaining the strategic nuclear weapons and conventional forces that are actually needed for U.S. and allied security in the foreseeable future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Second Batch of New START Data Released

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. State Department today released the full (unclassified) aggregate data for U.S. strategic nuclear forces as counted under the New START treaty. The data shows only very modest reductions of deployed strategic nuclear weapons over the past six months.

The full U.S. aggregate data follows the joint and much more limited overall U.S. and Russian aggregate numbers released in March 2012. Under the previous START treaty, the United States used to make Russian data available, but accepted Russia’s demand during the New START negotiations to no longer release their data.

The joint aggregate data and the full U.S. aggregate data are released at different times and not all information is made reality available on the Internet. Therefore, a full compilation of the data is made available here.

Overall U.S. Posture

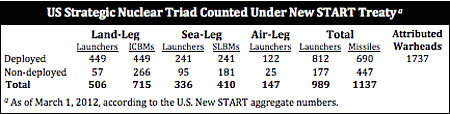

The New START data attributes 1,737 warheads to 812 deployed ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers as of March 1, 2012. This is a reduction of 53 deployed warheads and 10 deployed delivery vehicles compared with the previous data set from September 2011.

A large number of non-deployed missiles and launchers that could be deployed are not attributed warheads.

The data shows that the United States will have to eliminate 289 launchers over the next six years to be in compliance with the treaty limit of 700 deployed and non-deployed launchers by 2018. Fifty-six of these will come from reducing the number of launch tubes per SSBN from 24 to 20, roughly 80 from stripping B-52Gs and nearly half of the B-52Hs of their nuclear capability, possibly retiring 50 ICBMs, and destroying about 100 old ICBM silos.

The released data does not contain a breakdown of how the 1,737 deployed warheads are distributed across the three legs of the Triad. But because the bomber number is now disclosed and each bomber counts as one warhead, and because between 450 and 500 warheads remain on the ICBMs, it appears that the deployed SLBMs carried 1,112 to 1,165 warheads, or about two-thirds of the total number of warheads counted by New START.

Just to remind readers: the New START numbers do not represent the total number of nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal – only about a third. The total military stockpile is just under 5,000 warheads, with several thousand additional retired (but still intact) warheads awaiting dismantlement. For an overview, see this article.

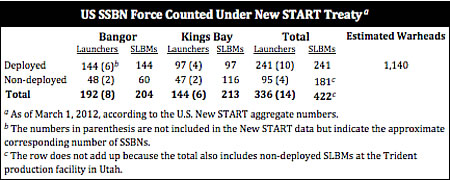

Ballistic Missile Submarines

The New START data shows that the United States as of March 1, 2012, had 241 Trident II SLBMs onboard its SSBN fleet. That is a reduction of eight SLBMs compared with the New START data from September 2011, but it doesn’t reflect an actual reduction in missiles on deployable submarines but a fluctuation in the number of missiles onboard SSBNs during loadout. Each SSBN has 24 missile tubes for a maximum loadout of 288 missiles, but at the time of the New START count two SSBNs were empty and two only partially loaded. With an estimated 1,140 warheads on the SLBMs, that translates to an average of 4-5 warheads per missile.

It is widely assumed that 12 out of 14 SSBNs normally are deployed, but two sets of aggregate New START data both indicate that the force ready for deployment at any given time may be closer to 10. This ratio can fluctuate significantly and in average 64 percent (8-9) of the SSBNs are at sea with roughly 920 warheads. Up to five of those subs are on alert with 120 missiles carrying an estimated 540 warheads – enough to obliterate every major city on the face of the earth.

Of the eight SSBNs based at Bangor (Kitsap) Submarine Base in Washington, the New START data indicates that two were out of commission on March 11, 2012: one had empty missile tubes – possibly because it was in dry dock – and another was only partially loaded – possibly because it was in the middle of a missile exchange when the count occurred. This means that six SSBNs at the base were loaded with Trident II D5 missiles carrying some 650 warheads at the time of the New START count.

For the six SSBNs based at Kings Bay Submarine Base in Georgia, the New START data shows that 97 missiles were deployed on March 1, 2012. That number is enough to load four SSBNs, with a fifth boat partially loaded. The 96 Trident II SLBMs on four SSBNs carried an estimated 430 warheads.

The New START data indicates that the U.S. Navy has not yet begun to reduce the number of missile tubes on each SSBN. The number will be reduced from 24 to 20 before the New START enters into effect in 2018.

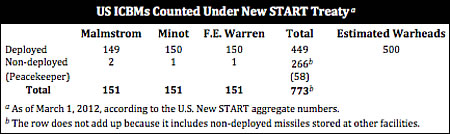

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles

The New START data shows that the United States deployed 449 Minuteman III ICBMs as of March 1, 2012. That is one more than on September 1, 2011. Most were at the three launch bases, but a significant number were in storage at maintenance and storage facilities in Utah. That included 58 MX Peacekeeper ICBMs retired in 2003-2005 but which have not been destroyed.

The New START data does not show how many warheads were loaded on the 449 deployed ICBMs, but the number is thought to be nearly 500. The 2010 NPR decided to “de-MIRV” the ICBM force, an unfortunately choice of words because the force will be downloaded to one warhead per missile, but retain the capability to re-MIRV if necessary. Downloading might have begun, but the status is unclear.

Heavy Bombers

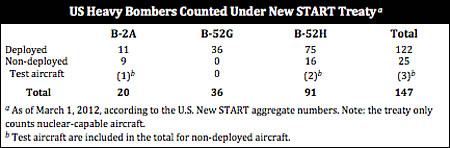

The New START data shows that the U.S. Air Force possessed 147 B-2 and B-52 bombers as of March 1, 2012. Of these, 122 were counted as deployed, a reduction of three compared with September 2011.

Unfortunately the bomber data is misleading because it counts 36 retired B-52G bombers stored at Davis Monthan AFB in Arizona as “deployed” at Minot AFB in North Dakota. The miscount is the result of a counting rule in the treaty, which says that bombers can only be deployed at certain bases. As a result, the 36 retired B-52Gs are listed in the treaty as deployed at Minot AFB – even though there are no B-52Gs at that base. According to Air Force Global Strike Command, “There are no B-52Gs at Minot AFB, N.D…In accordance with accounting requirements, we have them assigned to Minot and as visiting David Monthan.” The actual number of heavy bombers should more accurately be listed as 86 B-2A and B-52H, with another 61 non-deployed (including the 36 at Davis Monthan AFB.

All of these bombers carry equipment that makes them accountable under New START, but only a portion of them are actually involved in the nuclear mission. Of the 20 B-2s and 91 B-52s, 18 and 76, respectively, are nuclear-capable, although only about 60 of those are thought to be nuclear tasked at any given time. None of the aircraft are loaded with nuclear weapons under normal circumstances but are attributed a fake count under New START of only one nuclear weapon per aircraft even though each B-2 and B-52s can carry up to 16 and 20 nuclear weapons, respectively. Roughly 1,000 nuclear bombs and cruise missiles are in storage for use by these bombers. Stripping excess B-52Hs and the remaining B-52Gs of their nuclear equipment will be necessary to get down to 60 counted nuclear bombers by 2018.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The New START data released by the State Department continues the decision made last year to release the full U.S. unclassified aggregate numbers, an important policy that benefits nuclear transparency and counters misunderstandings and rumors. In parallel with the data comes a busy treaty implementation effort and inspection schedule that reassures the United States and Russia that each side is abiding by the terms of the treaty. Now we need Russia to follow the U.S. example and also release its full unclassified data under New START.

The latest data set shows that the U.S. reduction of its deployed strategic nuclear warheads over the past six months has been modest: 53 warheads. The reduction is so modest that it might not reflect a cut as much as a fluctuation in the number of deployed weapons at any given time due to maintenance of delivery systems. While there have been some reductions of non-deployed and retired weapon systems, there is no indication from the New START data that the United States has yet begun to reduce its deployed strategic nuclear weapons.

Those reductions are scheduled to come, however, over the next five years as the New START treaty limits of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads and 700 deployed strategic delivery vehicles are to be met in February 2018. Despite the high cost of maintaining unnecessary weapon systems, 18 months after the New START treaty entered into force the Pentagon does not seem to be in a hurry to meet the treaty limits.

Download the full New START data here.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.