$1 Billion for a Nuclear Bomb Tail

The U.S. Air Force plans to spend more than $1 billion on developing a guided tailkit to increase the accuracy of the B61 nuclear bomb.

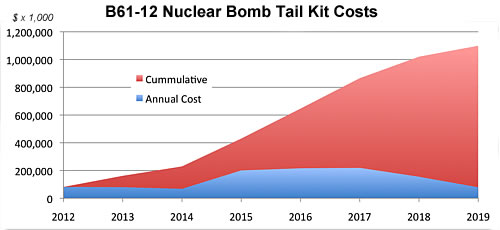

The cost is detailed (to some extent) in the Air Force’s budget request for FY2014, which shows development and engineering through FY2014 and full-scaled production starting in FY2015.

The annual costs increase by nearly 200 percent from $67.9 million in FY2014 to more than $200 million in FY2015. The high cost level will be retained for three years until the project decreases after production ceases in FY2018. Some additional funding is needed after that to complete the integration and certification on (see graph).

Production of the guided tailkit is intended to match completion of the first new B61-12 bomb in 2019, a program that is estimated to cost more than $10 billion. Although the number is a secret, it is thought that the U.S. plans to produce roughly 400 B61-12s.

The expensive guided tailkit is needed, advocates claim, to make it possible to use the 50-kiloton nuclear explosive package from the tactical B61-4 bomb in the new B61-12 against targets that today require the 360-kiloton strategic B61-7 bomb. By increasing accuracy, the B61-12 becomes more useable because it significantly reduces the amount of radioactive fallout created in an attack.

Once deployed in Europe, the B61-12 will also be able to hold at risk targets that the B61-3 and B61-4 bombs currently deployed in Belgium, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, and Turkey cannot target.

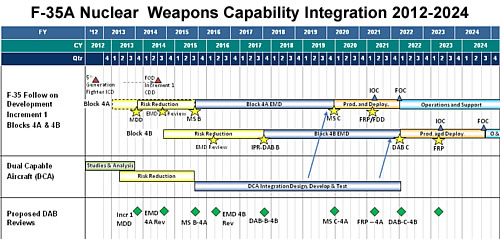

The B61-12 program will maintain compatibility on all five current B61-capable aircraft (B-2A, B-52H, F-16, F-15E and PA 200). In 2015, integration, design and testing will begin on the new stealthy F-35A Joint Strike Fighter. The Air Force budget request shows that B61-12 integration is scheduled for Block 4A and Block 4B aircraft in 2015-2021 with full operational capability in 2022 – three years after the first B61-12 is scheduled to be delivered (see table).

The combination of the new and more accurate guided B61-12 on the stealthy F-35A will significantly increase the capability of the U.S. non-strategic nuclear posture in Europe. This development is out of tune with U.S. and NATO pledges to reduce the role and reliance on nuclear weapons, and will make it a lot easier for hardliners in the Russian military to reject reductions of Russia’s larger inventory of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

US Nuclear War Plan Updated Amidst Nuclear Policy Review

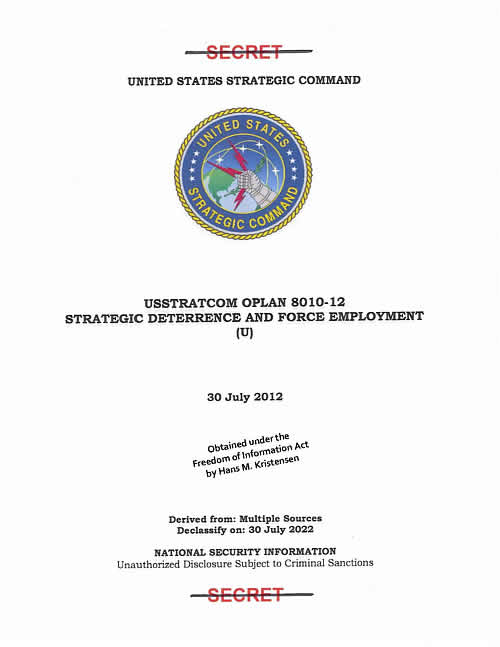

At the same time the White House is finishing a review of nuclear weapons policy, U.S. Strategic Command has quietly put into effect a new strategic nuclear war plan.

The new plan, which entered into effect in July 2012, is called OPLAN 8010-12 Strategic Deterrence and Force Employment. It replaces an earlier plan from 2008, that was revised in 2009.

A copy of the front page of OPLAN 8010-12 was obtained from U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) under the Freedom of Information Act.

OPLAN 8010-12 is the first strategic nuclear war plan update made since the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review in 2010. The administration has completed another review of nuclear targeting policy but not yet issued new presidential guidance, so the new war plan probably does not incorporate changes resulting from the review.

Triggering Plan Changes

Details of OPLAN 8010-12 are highly classified and it is yet unclear why a new plan has been issued at this point instead of awaiting the results of the administration’s targeting review. Minor adjustments are made to war plans all the time but new plan numbers are thought to reflect more significant changes.

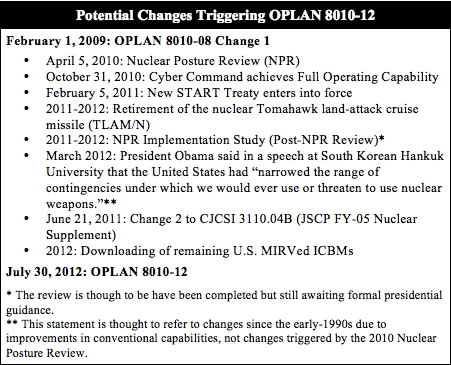

Plan updates can be triggered by several factors: changes in the adversaries that are targeted by the plan; changes to the U.S. nuclear force structure (introduction, modification, or retirement of nuclear weapon systems); or promulgation of new military or political guidance. Since the previous plan change in 2009, several important developments have occurred that could potentially have triggered production of OPLAN 8010-12 (see table).

The formal reason for the new plan was probably the update of the Nuclear Supplement to the Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan (CJCSI 3110.04B) that was issued by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in June 2011. The document, known as JSCP-N (formerly Annex C), provides nuclear planning guidance to combatant commanders in accordance with the Policy Guidance for the Employment of Nuclear Weapons (NUWEP) issued by the Secretary of Defense. This probably eliminates strike scenarios involving the recently retired nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N).

Over the same time period, the number of Russian ICBMs declined by approximately 80 missiles, most of them silo-based SS-18 and SS-19 missiles, a change that potentially would allow a reduction of at least 160 warheads from the U.S. war plan.

Plan Context

OPLAN 8010-12 is the nuclear combat employment portion (known as SIOP during the Cold War) of a wider plan also known as OPLAN 8010 (but without the update year). OPLAN 8010 is a “base plan” with annexes, one of which is OPLAN 8010-12. The annexes consist of plans for different elements of national power that span the entire spetrum of STRATCOM missions: nuclear forces; conventional strike options; non-kinetic (incuding cyber operaitons); misssile defense; intelligence, surveillance and reconnaisance; and counter-WMD.

The base plan (OPLAN 8010) is thought to be directed against six potential adversaries: Russia, China, North Korea, Iran, Syria, and WMD attacks by non-state actors.

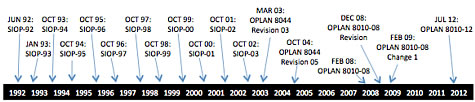

OPLAN 8010-12 replaces the previous nuclear war plan from 2008 (OPLAN 8010-08), which was most recently updated in February 2009. The current plan is the 18th major plan update since the end of the Cold War (see table).

OPLAN 8010-12 is produced, maintained, and – if so ordered by the president – executed by the Joint Functional Component Command for Global Strike (JFCC-GS), a 430-people unit located at STRATCOM at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska. JFCC-GS is responsible for not only nuclear plans but for the full spectrum of kinetic (nuclear and conventional) and non-kinetic effects.

The Name Game

The new plan has a new name: Strategic Deterrence and Force Employment. The previous plan from 2009 was called Strategic Deterrence and Global Strike, changed from the original Global Deterrence and Strike in 2008.

- OPLAN 8010-08 Revision (December 1, 2008): Global Deterrence and Strike

- OPLAN 8010-08 Change 1 (February 1, 2009): Strategic Deterrence and Global Strike

- OPLAN 8010-12 (July 30, 2012): Strategic Deterrence and Force Employment

Three names in five years indicate a plan in evolution. The frequent name changes probably reflect an ongoing search for a name that more accurately captures the essense of the plan. Global Strike might have caused confusion with the non-nuclear Prompt Global Strike mission.

Guiding Further Reductions

As mentioned above, the Obama administration has completed an internal review of U.S. nuclear targeting policy, but has yet to issue formal presidential guidance to the military for how this will affect future revisions of OPLAN 8010-12. Yet indications are that important changes might be forthcoming.

While defense hawks lament the administration’s intension to reduce U.S. (and Russian) nuclear forces, the military has already concluded that nuclear forces can be reduced without undermining national or extended deterrence commitments:

- The Pentagon’s February 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review concluded that “new, tailored, regional deterrence architectures…make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.”

- The Pentagon’s February 2010 Ballistic Missile Defense Review stated: “Against nuclear-armed states, regional deterrence will necessarily include a nuclear component (whether forward-deployed or not). But the role of U.S. nuclear weapons in these regional deterrence architectures can be reduced by increasing the role of missile defenses and other capabilities.”

- The Pentagon’s April 2010 Nuclear Posture Review Report concluded that the United States can deter potential adversaries and reassure allies and partners “at significantly lower nuclear force levels and with reduced reliance on nuclear weapons” while “working to reduce the salience of nuclear weapons in international affairs and moving step-by-step toward eliminating them…”

- The Pentagon’s January 2012 strategy Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense concluded that, “It is possible that out deterrence goals can be achieved with a smaller nuclear force, which would reduce the number of nuclear weapons in our inventory as well as their role in U.S. national security strategy.” (Emphasis in original).

Underpinning these decisions is that only small nuclear forces are needed for contingencies against regional adversaries such as North Korea and Iran, which can better be addressed with conventional forces. But even against Russia (and increasingly China), which continues to dominate U.S. nuclear planning, the Pentagon and the Intelligence Community have concluded that “a disarming first strike [against the United States] will most likely not occurr,” and that Russia would “not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or break-out scenario under the New START Treaty…”

These changes have allowed reductions of nuclear forces and strike scenarios in the past, leaving a stockpile of roughly 4,650 warheads. But although very different from the SIOP, OPLAN 8010-12 is still thought to be focused on nuclear warfighting scenarios using a Cold War-like Triad of nuclear forces on high alert to hold at risk and, if necessary, hunt down and destroy nuclear (and to a smaller extent chemical and biological) forces, command and control facilities, military and national leadership, and war supporting infrastructure in a myriad of tailored strike scenarios.

In Prague four years ago, President Obama said: “To put an end to Cold War thinking, we will reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security…” Doing so takes more than trimming limited scenarios against small regional adversaries but changing the core mission against Russia and China.

So when President Obama signs his new Presidential Policy Directive in the near future, it is important that it directs the military to change OPLAN 8010-12 in such a way that it actually puts an end to Cold War thinking. This will be his last chance to do so.

Other background: Reviewing Nuclear Guidance: Putting Obama’s Words Into Action (Arms Control Today, 2011) | Obama and the Nuclear War Pan (FAS 2010) | From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence (FAS/NRDC 2009)

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Data: US Reductions Finally Picking Up; Russia Flatlining

By Hans M. Kristensen

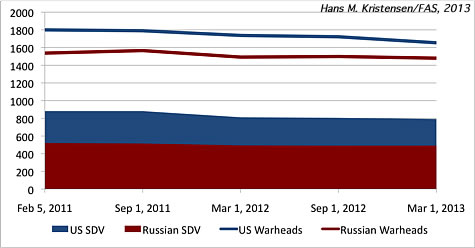

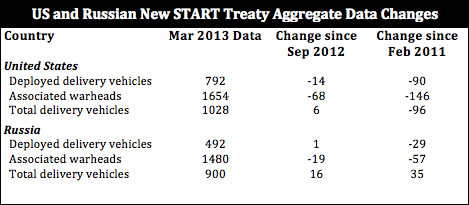

After two years of stalling, the latest New START Treaty aggregate data released today by the State Department indicates that U.S. warhead reductions under the treaty are finally picking up.

Russia, which is already below the treaty limit, has been more or less flatlining over the past year.

Seen in perspective, however, the warhead reductions achieved under New START so far are not impressive: since the treaty entered into effect in February 2011, the world’s two largest nuclear weapons states – with combined stockpiles of nearly 10,000 warheads – have only reduced their deployed arsenals by a total of 203 warheads!

The data for the United States shows a reduction of 68 warheads compared with September 2012. Fourteen of those are probably “fake” warheads attributed to B-52G bombers that are counted as deployed under the treaty, although they are neither deployed nor nuclear tasked anymore. The remaining 54-warhead reduction probably reflects downloading of the remaining MIRVed ICBMs (and some fluctuations in SLBM loadings of SSBNs in refit). Another 104 warheads will have to be reduced over the next five years to meet the treaty limit of 1,550 deployed accountable warheads by 2018 (although many of those will come from reducing bombers that are not actually assigned nuclear weapons).

Russia, which has been below the ceiling of 1,550 deployed accountable strategic warheads for the past year, appears to be flatlining. It is counted with a 19-warhead reduction compared with September 2012. But that number is too low say whether it reflects real reductions due to retirement of missiles or just fluctuations in SLBM loadings on SSBNs in refit. Russia increased its delivery vehicles slightly due to deployment of the first new Borei-class SSBN.

What’s most striking about the data, though, is the significant asymmetry in delivery vehicles: the United States has 300 deployed delivery vehicles more than Russia, a disparity that causes Russia to deploy more warheads on each delivery vehicle and fuels worst-case military planning and paranoia about treaty break-out plans.

A clear objective for the next arms control agreement between the United States and Russia will have to be to reduce the U.S. delivery vehicles and Russian warhead loading to improve stability of the postures.

Moreover, with only 203 deployed warheads cut since the New START Treaty entered into effect more than two years ago, and nearly 10,000 nuclear warheads remaining in their stockpiles combined, there is clearly a need for the United States and Russia to speed up implementation of the treaty and agree to significant additional reductions.

[Details about the reductions are murky because the aggregate data only includes overall numbers, and does not specify how many of each delivery system are counted. A more detailed analysis will follow when the full detailed U.S. data becomes available in a few weeks.]

Background: See previous New START Treaty data analysis

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Q&A Session on Recent Developments in U.S. and NATO Missile Defense with Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis

Dr. Yousaf Butt, a nuclear physicist, is professor and scientist-in-residence at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. The views expressed are his own.

Dr. George N. Lewis is a senior research associate at the Judith Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies at Cornell University.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked two physicists who are experts in missile defense issues, Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis, to weigh in on last week’s announcements on missile defense by the Obama administration.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked two physicists who are experts in missile defense issues, Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis, to weigh in on last week’s announcements on missile defense by the Obama administration.

Before exploring their reactions and insights, it is useful to identify salient elements of U.S. missile defense and place the issue in context. There are two main strategic missile defense systems fielded by the United States: one is based on large high-speed interceptors called Ground-Based Interceptors or “GBI’s” located in Alaska and California and the other is the mostly ship-based NATO/European system. The latter, European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) to missile defense is designed to deal with the threat posed by possible future Iranian intermediate- and long-range ballistic missiles to U.S. assets, personnel, and allies in Europe – and eventually attempt to protect the U.S. homeland.

The EPAA uses ground-based and mobile ship-borne radars; the interceptors themselves are mounted on Ticonderoga class cruisers and Arleigh Burke class destroyers. Two land-based interceptor sites in Poland and Romania are also envisioned – the so-called “Aegis-ashore” sites. The United States and NATO have stated that the EPAA is not directed at Russia and poses no threat to its nuclear deterrent forces, but as outlined in a 2011 study by Dr. Theodore Postol and Dr. Yousaf Butt, this is not completely accurate because the system is ship-based, and thus mobile it could be reconfigured to have a theoretical capability to engage Russian warheads.

Indeed, General James Cartwright has explicitly mentioned this possible reconfiguration – or global surge capability – as an attribute of the planned system: “Part of what’s in the budget is to get us a sufficient number of ships to allow us to have a global deployment of this capability on a constant basis, with a surge capacity to any one theater at a time.”

In the 2011 study, the authors focused on what would be the main concern of cautious Russian military planners —the capability of the missile defense interceptors to simply reach, or “engage,” Russian strategic warheads—rather than whether any particular engagement results in an actual interception, or “kill.” Interceptors with a kinematic capability to simply reach Russian ICBM warheads would be sufficient to raise concerns in Russian national security circles – regardless of the possibility that Russian decoys and other countermeasures might defeat the system in actual engagements. In short, even a missile defense system that could be rendered ineffective could still elicit serious concern from cautious Russian planners. The last two phases of the EPAA – when the higher burnout velocity “Block II” SM-3 interceptors come on-line in 2018 – could raise legitimate concerns for Russian military analysts.

A Russian news report sums up the Russian concerns: “[Russian foreign minister] Lavrov said Russia’s agreement to discuss cooperation on missile defense in the NATO Russia Council does not mean that Moscow agrees to the NATO projects which are being developed without Russia’s participation. The minister said the fulfillment of the third and fourth phases of the U.S. ‘adaptive approach’ will enter a strategic level threatening the efficiency of Russia’s nuclear containment forces.” [emphasis added]

With this background in mind, FAS’ Senior Fellow on State and Non-State Threat, Charles P. Blair (CB), asked Dr. Yousaf Butt (YB) and Dr. George Lewis (GL) for their input on recent developments on missile defense with eight questions.

Q: (CB) Last Friday, Secretary of Defense Hagel announced that the U.S. will cancel the last Phase – Phase 4 – of the European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) to missile defense which was to happen around 2021. This was the phase with the faster SM-3 “Block IIB” interceptors. Will this cancellation hurt the United State’s ability to protect itself and Europe?

A: (YB) No, because the “ability” you mention was always hypothetical. The Achilles’ Heel of all versions of the SM-3 (Block I A/B and Block II A/B) interceptors — indeed of “midcourse” missile defense, in general, is that it is straightforward to defeat the system using cheap decoy warheads. The system simply does not have a robust ability to discriminate a genuine warhead from decoys and other countermeasures. Because the intercepts take place in the vacuum of space, the heavy warhead and light decoys travel together, confusing the system’s sensors. The Pentagon’s own scientists at the Defense Science Board said as much in 2011, as did the National Academy of Sciences earlier this year.

Additionally, the system has never been successfully tested in realistic conditions stressed by the presence of decoys or other countermeasures. The majority of the system would be ship-based and is not known to work beyond a certain sea-state: as you might imagine, it becomes too risky to launch the interceptors if the ship is pitching wildly.

So any hypothetical (possibly future) nuclear-armed Middle Eastern nation with ICBMs could be a threat to the Unites States or Europe whether we have no missile defenses, have just Block I interceptors, or even the Block II interceptors. Since the interceptors would only have offered a false sense of security, nothing is lost in canceling Phase 4 of the EPAA. In fact, the other phases could also be canceled with no loss to U.S. or NATO security, and offering considerable saving of U.S. taxpayer’s money.

Q: (CB) What about Iran and its alleged desire to build ICBMs? Having just launched a satellite in January, could such actions act as a cover for an ICBM?

A: (YB) The evidence does not point that way at all. It points the other way. For instance, the latest Congressional Research Service (CRS) report on Iran’s missile program observes: (emphasis added)

“Iran also has a genuine and ambitious space launch program, which seeks to enhance Iran’s national pride, and perhaps more importantly, its international reputation as a growing advanced industrial power. Iran also sees itself as a potential leader in the Middle East offering space launch and satellite services. Iran has stated it plans to use future launchers for placing intelligence gathering satellites into orbit, although such a capability is a decade or so in the future. Many believe Iran’s space launch program could mask the development of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) – with ranges in excess of 5,500 km that could threaten targets throughout Europe, and even the United States if Iran achieved an ICBM capability of at least 10,000 km. ICBMs share many similar technologies and processes inherent in a space launch program, but it seems clear that Iran has a dedicated space launch effort and it is not simply a cover for ICBM development. Since 1999, the U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) has assessed that Iran could test an ICBM by 2015 with sufficient foreign assistance, especially from a country such as China or Russia (whose support has reportedly diminished over the past decade). It is increasingly uncertain whether Iran will be able to achieve an ICBM capability by 2015 for several reasons: Iran does not appear to be receiving the degree of foreign support many believe would be necessary, Iran has found it increasingly difficult to acquire certain critical components and materials because of sanctions, and Iran has not demonstrated the kind of flight test program many view as necessary to produce an ICBM.”

Furthermore, the payload of Iran’s space launch vehicles is very low compared to what would be needed for a nuclear warhead — or even a substantial conventional warhead. For instance, Omid, Iran’s first satellite weighed just 27 kg [60 pounds] and Rasad-1, Iran’s second satellite weighed just 15.3 kilograms [33.74 pound], whereas a nuclear warhead would require a payload capacity on the order of 1000 kilograms. Furthermore, since launching an ICBM from Iran towards the United States or Europe requires going somewhat against the rotation of Earth the challenge is greater. As pointed out by missile and space security expert Dr. David Wright, an ICBM capable of reaching targets in the United States would need to have a range longer than 11,000 km. Drawing upon the experience of France in making solid-fuel ICBMs, Dr. Wright estimates it may take 40 years for Iran to develop a similar ICBM – assuming it has the intention to kick off such an effort. A liquid fueled rocket could be developed sooner, but there is little evidence in terms of rocket testing that Iran has kicked off such an effort.

In any case, it appears that informed European officials are not really afraid of any hypothetical Iranian missiles. For example, the Polish foreign minister, Radoslaw Sikorski, once made light of the whole scenario telling Foreign Policy, “If the mullahs have a target list we believe we are quite low on it.” As if to emphasize that point, the Europeans don’t appear to be pulling their weight in terms of funding the system. “We love the capability but just don’t have the money,” one European military official stated in reference to procuring the interceptors.

Similarly, the alleged threat from North Korea is also not all that urgent.

It seems U.S. taxpayers are subsidizing a project that will have little national security benefits either for the United States or NATO countries. In contrast, it may well create a dangerous false sense of security. It has already negatively impacted ties with Russia and China.

Q: (CB) Isn’t Iran’s alleged nuclear weapons program a big concern in arguing for a missile defense? Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel said Iran may cross some red-line in the summer?

A: (YB) Iran’s nuclear program could be a concern, but the latest report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) says Iran has not even decided to make nuclear weapons yet. Building, testing and miniaturizing a warhead to fit on a missile takes years – after a country decides to do so. In any case, no matter how scary that hypothetical prospect, one would not want a missile defense system that could be easily defeated to address that alleged eventual threat. Even if you believe the threat exists now, you may want a system that is effective, not a midcourse system that has inherent flaws.

Incidentally, the DNI’s report explicitly states: “we assess Iran could not divert safeguarded material and produce a weapon-worth of WGU [weapons grade uranium] before this activity is discovered.” As for the red-line drawn by Prime Minister Netanyahu: his track-record on predicting Iranian nuclear weaponization has been notoriously bad. As I point out in a recent piece for Reuters, in 1992 Mr. Netanyahu said Iran was three to five years from a bomb. I assess he is still wrong, more than 20 years later.

Lastly, even if Iran (or other nations) obtained nuclear weapons in the future, they can be delivered in any number of ways- not just via missiles. In fact, nuclear missiles have the benefit of being self-deterring – nations are actually hesitant to use nuclear weapons if they are mated to missiles. Other nations know that the United States can pinpoint the launch sites of missiles. The same cannot be said of a nuclear device placed in a sailboat, a reality that could precipitate the use of that type of device due to the lack of attribution. So one has to carefully consider if it makes sense to dissuade the placement of nuclear weapons on missiles. If an adversarial nation has nuclear weapons it may be best to have them mated to missiles rather than boats.

Q: (CB) It seems that the Russians are still concerned about the missile defense system, even after Defense Secretary Hagel said that the fourth phase of EPAA plan is canceled. Why are they evidently still concerned?

A: (YB) The Russians probably have four main concerns with NATO missile defense, even after the cancellation of Phase 4 of EPAA. For more details on some of these please see the report Ted Postol and I wrote.

1. The first is geopolitical: the Russians have never been happy about the Eastward expansion of NATO and they see joint U.S.-Polish and U.S.-Romanian missile defense bases near their borders as provocative. This is not to say they are right or wrong, but that is most likely their perception. These bases are to be built before Phase 4 of the EPAA, so they are still in the plans.

2. The Russians do not concur with the alleged long-range missile threat from Iran. One cannot entirely blame them when the Polish foreign minister himself makes light of the alleged threat saying, “If the mullahs have a target list we believe we are quite low on it.” Russian officials are possibly confused and their military analysts may even be somewhat alarmed, mulling what the real intent behind these missile defense bases could be, if – in their assessment – the Iran threat is unrealistic, as in fact was admitted to by the Polish foreign minister. The Russians also have to take into account unexpected future changes which may occur on these bases, for instance: a change in U.S. or Polish or Romanian administrations; a large expansion of the number or types of interceptors; or, perhaps even nuclear-tipped interceptors (which were proposed by former Defense Secretary Rumsfeld about ten years ago).

3. Russian military planners are properly hyper-cautious, just like their counterparts at the Pentagon, and they must assume a worst-case scenario in which the missile defense system is assumed to be effective, even when it isn’t. This concern likely feeds into their fear that the legal balance of arms agreed to in New START may be upset by the missile defense system.

Their main worry could be with the mobile ship-based platforms and less with the European bases, as explained in detail in the study Ted Postol and I did. Basically, the Aegis missile defense cruisers could be placed off of the East Coast of the U.S. and – especially with Block IIA/B interceptors –engage Russian warheads. Some statements from senior U.S. officials probably play into their fears. For instance, General Cartwright has been quoted as saying, “part of what’s in the budget is to get us a sufficient number of ships to allow us to have a global deployment of this capability on a constant basis, with a surge capacity to any one theater at a time.” To certain Russian military planners’ ears that may not sound like a limited system aimed at a primitive threat from Iran.

Because the mobile ship-based interceptors (hypothetically placed off of the U.S. East Coast ) could engage Russian warheads, Russian officials may be able claim this as an infringement on New START parity.

Missile defenses that show little promise of working well can, nevertheless, alter perceptions that the strategic balance between otherwise well-matched states is stable. Even when missile defenses reveal that they possess little, if any technical capabilities, they can still cause cautious adversaries and competitors to react as if they might work. The United States’ response to the Cold War era Soviet missile defense system was similarly overcautious.

4. Finally, certain Russian military planners may worry about the NATO EPAA missile defense system because in Phase 3, the interceptors are to be based on the SM-3 Block IIA booster. The United States has conducted research using this same type of rocket booster as the basis of a hypersonic-glide offensive strike weapon called ArcLight. Because such offensive hyper-glide weapons could fit into the very same vertical launch tubes – on the ground in Poland and Romania, or on the Aegis ships – used for the defensive interceptors, the potential exists for turning a defensive system into an offensive one, in short order. Although funding for ArcLight has been eliminated in recent years, Russian military planners may continue to worry that perhaps the project “went black” [secret], or that it may be resuscitated in the future. In fact, a recent Federal Business Opportunity (FBO) for the Department of the Navy calls for hypersonic weapons technologies that could fit into the same Mk. 41 Vertical Launch System (VLS) tubes that the SM-3 missile defense interceptors are also placed in.

To conclude, advocates of missile defense who say we need cooperation on missile defense to improve ties with Russia have the logic exactly backward: In large part, the renewed tension between Russia and the United States is about missile defense. Were we to abandon this flawed and expensive idea, our ties with Russia — and China — would naturally improve. And, in return, they could perhaps help us more with other foreign policy issues such as Iran, North Korea, and Syria. As it stands, missile defense is harming bilateral relations with Russia and poisoning the well of future arms control.

Q: (CB) Adding to the gravity of Secretary Hagel’s announcement , last week China expressed worry about Ground-Based Interceptors, the Bush administration’s missile defense initiative in Poland discarded by the Obama administration in 2009, in favor of Phase 4 of the EPAA. Why is there concern with not only the Aegis ship-based system, but also the GBIs on the West Coast?

A: (YB) Like the Russians, Chinese military analysts are also likely to assume the worst-case scenario for the system (ie. that it will work perfectly) in coming up with their counter response . Possessing a much smaller nuclear arsenal than Russia or the United States, to China, even a few interceptors can be perceived as making a dent in their deterrent forces. And I think the Chinese are likely worried about both the ship-based Aegis system as well as the West Coast GBIs.

And this concern on the part of the Chinese is nothing new. They have not been as vocal as the Russians, but it is evident they were never content with U.S. and NATO plans. For instance, the 2009 Bipartisan Strategic Posture Commission pointed out that “China may already be increasing the size of its ICBM force in response to its assessment of the U.S. missile defense program.” Such stockpile increases, if they are taking place, will probably compel India, and, in turn, Pakistan to also ramp up their nuclear weapon numbers.

The Chinese may also be looking to the future and think that U.S. defenses may encourage North Korea to field more missiles than it may originally have been intending – if and when the North Koreans make long range missiles – to make sure some get through the defense system. This would have an obvious destabilizing effect in East Asia which the Chinese would rather avoid.

Some U.S. media outlets have also said the ship-based Aegis system could be used against China’s DF-21D anti-ship missile, when the official U.S. government position has always been that the system is only intended only against North Korea (in the Pacific theater). Such mission creep could sound provocative to the Chinese, who were told that the Aegis system is not “aimed at” China.

In reality, while the Aegis system’s sensors may be able to help track the DF-21D it is unlikely that the interceptors could be easily modified to work within the atmosphere where the DF-21D’s kill vehicle travels. (It could perhaps be intercepted at apogee during the ballistic phase). A recent CRS report was quite explicit that the DF-21D is a threat which remains unaddressed in the Navy: “No Navy target program exists that adequately represents an anti-ship ballistic missile’s trajectory,’ Gilmore said in the e-mail. The Navy ‘has not budgeted for any study, development, acquisition or production’ of a DF-21D target, he said.”

Chinese concerns about U.S. missile defense systems are also a source of great uncertainty, reducing Chinese support for promoting negotiations on the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty (FMCT). China’s leaders may wish to maintain the option of future military plutonium production in response to U.S. missile defense plans.

The central conundrum of midcourse missile defense remains that while it creates incentives for adversaries and competitors of the United States to increase their missile stockpiles, it offers no credible combat capability to protect the United States or its allies from this increased weaponry.

Q: (CB) Will a new missile defense site on the East Coast protect the United States? What would be the combat effectiveness of an East Coast site against an assumed Iranian ICBM threat?

A: (GL) I don’t see any real prospect for even starting a program for interceptors such as the [East Coast site] NAS is proposing any time soon in the current budget environment, and even if they did it probably would not be available until the 2020s. The recent announcement of the deployment of additional GBI interceptors is, in my view, just cover for getting rid of the Block II Bs, and was chosen because it was relatively ($1+ billion) inexpensive and could be done quickly.

The current combat effectiveness of the GBIs against an Iranian ICBM must be expected to be low. Of course there is no current Iranian ICBM threat. However, the current GMD system shows no prospect of improved performance against any attacker that takes any serious steps to defeat it as far out in time, as plans for this system are publicly available. Whether the interceptors are based in Alaska or on the East Coast makes very little difference to their performance.

Q: (CB) There were shortcomings reported by the Defense Science Board and the National Academies regarding the radars that are part of the system. Has anything changed to improve this situation?

A: (GL) With respect to radars, the main point is that basically nothing has happened. The existing early warning radars can’t discriminate [between real warheads and decoys]. The only radar that could potentially contribute to discrimination, the SBX, has been largely mothballed.

Q: (CB) Let’s say the United States had lots of money to spend on such a system, would an East Coast site have the theoretical ability to engage Russian warheads? Regardless of whether Russia could defeat the system with decoys or countermeasures, does the system have an ability to reach or engage the warheads? In short, could such a site be a concern for Russia?

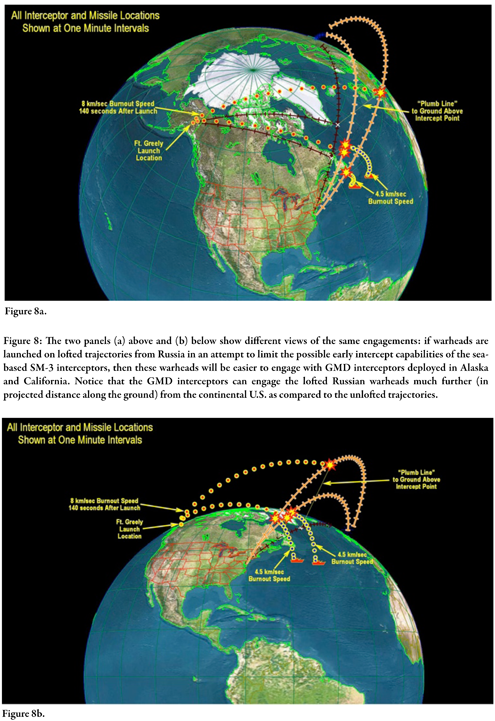

A: (YB) If you have a look at Fig 8(a) and 8(b) in the report Ted Postol and I wrote you’ll see pretty clearly why an East Coast site might be a concern for Russia, especially with faster interceptors that are proposed for that site. Now I’m not saying it necessarily should be a concern – because they can defeat the system rather easily – but it may be. Whether they object to it or not vocally depends on other factors also. For instance, such a site will obviously not be geopolitically problematic for the Russians.

Figures 8(a) and 8(b) from the FAS Special Report Upsetting the Reset: The Technical Basis of Russian Concern Over NATO Missile Defense, by Yousaf Butt and Theodore Postol (p. 27).

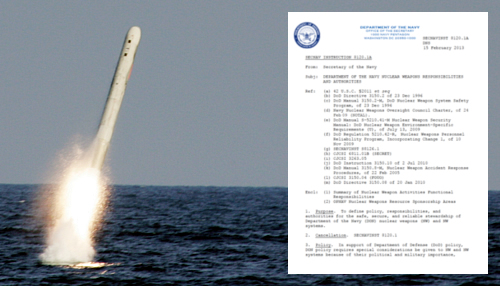

US Navy Instruction Confirms Retirement of Nuclear Tomahawk Cruise Missile

The U.S. Navy has quietly removed the nuclear Tomahawk cruise missile from its inventory, a new Secretary of the Navy Instruction shows.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Although the U.S. Navy has yet to make a formal announcement that the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N) has been retired, a new updated navy instruction shows that the weapon is gone.

The evidence comes not in the form of an explicit statement, but from what has been deleted from the U.S. Navy’s instruction Department of the Navy Nuclear Weapons Responsibilities and Authorities (SECNAVINST 8120.1A).

While the previous version of the instruction from 2010 included a whole sub-section describing TLAM/N responsibilities, the new version published on February 15, 2013, contains no mentioning of the TLAM/N at all and the previous sub-section has been deleted.

The U.S. Navy is finally out of the non-strategic nuclear weapons business. The stockpile has declined and a substantial number of TLAM/N warheads (W80-0) have already been dismantled. [Update 21 Mar: FY12 Pantex Performance Evaluation Report states (p.24): “All W80-0 warheads in the stockpile have been dismantled.” (Thanks Jay!)].

The End Of An Era

The retirement of the TLAM/N completes a 25-year process of eliminating all non-strategic naval nuclear weapons from the U.S. Navy’s arsenal.

In 1989, diligent researchers using the Freedom of Information Act discovered that the navy planned to unilaterally retire three of its non-strategic nuclear weapons.

|

| Retirement of the TLAM/N comes two decades after the U.S. Navy retired the SUBROC, ASROC, and Terrier. |

The first to go was the SUBROC, a submarine-launched rocket introduced in 1965 to deliver a 5-kiloton nuclear torpedo against another submarine. The SUBROC was widely deployed on attack submarines for 24 years and retired in 1989.

The ASROC was next in line, a ship-launched rocket introduced in 1961 to deliver a 10-kiloton depth bomb against submarines. The ASROC was widely deployed on cruisers, destroyers, and frigates for 29 years and retired in 1990.

The third non-strategic nuclear weapon to be unilaterally retired was the nuclear Terrier, a ship-launched surface-to-air missile introduced in 1961 to deliver a 1-kiloton warhead against aircraft. The nuclear Terrier was retired in 1990 after 29 years.

These weapons had little military value but huge political consequences when they sailed into ports of allied countries whose governments were forced to ignore violation of their own non-nuclear policies to avoid being seen as disloyal to their nuclear-armed ally.

The Regan administration planned to replace all of these weapons with new types: the SUBROC would be replaced by the Sea Lance rocket; the ASROC would be replaced with the Vertical ASROC; and the Terrier was to be replaced by the Standard 2 missile. But all of these replacement programs were cancelled. The Harpoon cruise missile was also intended to have a nuclear warhead option, but that was also canceled. Originally 758 TLAM/Ns were planned but only 350 were built, and 260 were left when the Obama administration decided to retire the weapon.

After the unilateral retirement of the SUBROC, ASROC, and Terrier missiles, the navy was left with B61 and B57 bombs on aircraft carriers and land-based anti-submarine aircraft, as well as the TLAM/N. Work initially continued on the B90 NSDB (nuclear strike and depth bomb) to replace the naval B61 and B57, but in September 1991 president George H.W. Bush unilaterally cancelled the program and ordered the offloading and withdrawal of all non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The Clinton administration’s 1994 Nuclear Posture Review followed up by denuclearizing the entire surface fleet, leaving only TLAM/N for some of the navy’s attack submarines. The missiles were stored on land, however, and never made it back to sea.

In the early part of the George W. Bush administration, the navy wanted to retire the TLAM/N, but some officials in the National Security Council and the Office of the Secretary of Defense insisted that the weapon was needed for certain missions in defense of allied countries. As a result, the TLAM/N survived the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review, and up through 2005 the navy continued to test launch the missile from attack submarines.

Some official and lobbyists tried to protect the TLAM/N during the 2009 Congressional Strategic Posture Commission process, but they failed. The Obama administration’s 2010 Nuclear Posture Review determined that the TLAM/N should finally be retired because it was redundant.

Implications

More than two decades after the end of the Cold War, and tens of millions of dollars and countless of navy personnel hours wasted on retaining the TLAM/N, the weapon has finally been retired and the navy is out of the non-strategic nuclear weapons business altogether.

This is monumental achievement and marks the end of a long process. In 1987, the U.S. Navy possessed more than 3,700 non-strategic nuclear weapons for use by almost 240 nuclear-capable ships and attack submarines in nuclear battles on the high seas. Today the number is zero.

Submarine crews can finally focus on real-world operations without the burden of non-strategic nuclear weapons, and government officials from the United States and its Pacific allies can finally begin to think about how to structure extended deterrence without clinging to the Cold War illusion that it requires tactical naval nuclear weapons.

I only wish the Obama administration and its allies were not so timid about the achievement. The unilateral elimination of naval non-strategic nuclear weapons is an important milestone in U.S. nuclear weapons history that demonstrates that non-strategic nuclear weapons have lost their military and political value. Russia has partly followed the initiative by eliminating a third of its non-strategic naval nuclear weapons since 1991, but is holding on to the rest to compensate against superior U.S. conventional naval forces.

But why not propose to Russia that they follow the TLAM/N retirement by retiring their nuclear land-attack cruise missile, the SS-N-21, and stop building new ones? The land-attack cruise missiles have nothing to do with compensating for naval conventional inferiority. Highlighting the retirement of the TLAM/N, moreover, might even help undercut some of the North Korean Generals’ rhetoric about a U.S. nuclear threat. Milk the TLAM/N retirement for all it’s worth!

Documents: SECNAVINST 8120.1 (2010) | SECNAVINST 8120.1A (2013) | Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons (FAS, May 2012)

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Invitation to Debate on Nuclear Weapons Reductions

Nuclear Debate at the Big 1800 Tonight

.By Hans M. Kristensen

Tonight I’ll be debating additional nuclear weapons reductions with former Assistant Secretary of State Stephen Rademaker at a PONI event at CSIS.

I will argue (prepared remarks here) that the United States could make more unilateral nuclear arms reductions in the future, as it has safely done in the past, as I argued in Trimming Nuclear Excess, in addition to pursuing arms control agreements. Mr. Rademaker will argue against unilateral reductions in favor of reciprocal or negotiated ones.

I suspect there will be a fair amount of overlap in the arguments but it is certainly a timely debate with the Obama administration pursuing additional reductions with Russia, the still-to-be-announced Nuclear Posture Review Implementation Study having determined that the United States can meet its national security and extended deterrence obligations with 500 fewer deployed strategic warheads, and budget cuts forcing new thinking about how many nuclear weapons and of what kind are needed.

The doors open at CSIS on 1800 K Street at 6 PM for a reception followed by the debate starting at 6:30 PM.

Document: Prepared remarks

(Still) Secret US Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Reduced

The United States has unilaterally reduced the size of its nuclear weapons stockpile by nearly 500 warheads since 2009.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The United States has quietly reduced its nuclear weapons stockpile by nearly 500 warheads since 2009. The current stockpile size represents an approximate 85-percent reduction compared with the peak size in 1967, according to information provided to FAS by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA).

The reduction is unilateral and not required by any arms control treaty. It apparently includes retirement of warheads for the last non-strategic naval nuclear weapon, the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N).

85 Versus 87

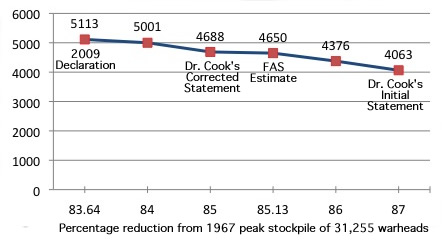

One of the interesting moments at the Deterrence Summit last week came when Dr. Donald Cook, who is NNSA’s administrator for defense programs, talked about the size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile.

At one point, Dr. Cook said that there are “roughly 5,000” warheads in the stockpile today. And then he added: “Today it’s, I’ll just say it’s a bit under about 5,000…about an 87 percent reduction” compared with the peak in 1967. (The 87 percent statements occurs 2:52:25 into the CSPAN recording).

Since the peak size of the stockpile has been declassified (31,255 warheads in 1967), an 87 percent reduction would in fact be quite a bit under 5,000 – a stockpile of 4,063 warheads, to be precise. If so, the stockpile would have shrunk by 1,050 warheads since September 2009 when the stockpile contained 5,113 warheads.

The number didn’t fit the stockpile estimate that Norris and I currently have (4,650 warheads), so I contacted Dr. Cook to double check if he meant to say 87 percent. He told me that it was an error and that the correct figure was “approximately 85% reduction.” That corresponds to a stockpile of roughly 4,688 warheads (depending on how many digits “approximately” implies), or about 38 warheads off our estimate of 4,650 warheads.

The warheads retired since 2009 apparently include the W80-0 warhead previously used on the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N). The 2010 Nuclear Posture Review decided the weapon was no longer needed, and “a very substantial number of W80-0″ warheads already have been dismantled, Dr. Cook told Congress last week. [Update 21 Mar: FY12 Pantex Performance Evaluation Report states (p.24): “All W80-0 warheads in the stockpile have been dismantled.” (Thanks Jay!)].

|

| The last remaining U.S. non-strategic naval nuclear weapon – the Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N – appears to have been retired in accordance with the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review determination that the weapon is no longer needed. |

.

Implications

Why is the size of the stockpile an issue? Well, first, because the Obama administration in 2010 declassified the 64-year history of the stockpile from 1945 through September 2009 because, as the Pentagon explained at the time, increasing transparency is important for U.S. nonproliferation efforts and additional arms reductions beyond the New START treaty. In his briefing, Dr. Cook also pointed to the importance of transparency.

Second, the size of the stockpile is important because although the administration has declassified 64 years of its history, its current size is – yes, you guessed it – still a secret. In fact, officials have told us that the 2010 disclosure was a one-time decision, not something that would be updated each year. So all stockpile numbers after September 2009 are still secret. Deep in the dark corridors of the Pentagon there are still people who believe this is necessary for national security.

Third, the unilateral retirement of roughly 500 warheads from the stockpile since 2009 – an inventory comparable to the total stockpiles of China and Britain combined – is political dynamite (no pun intended) because conservative Cold Warriors in Congress (and elsewhere) vehemently oppose unilateral reductions of U.S. nuclear weapons. Their argument is (as best I can gauge) that Russia and China are modernizing their nuclear weapons, and North Korea has just conducted a nuclear test. Therefore, so the thinking goes, it would somehow be detrimental to U.S. national security to unilaterally reduce its nuclear weapons.

The argument is, of course, deeply flawed because the reductions that Dr. Cook describe are warheads that the military has decided it no longer needs to meet presidential guidance for maintaining a strong nuclear deterrent in support of national security and reassurance of allies. Similar unilateral adjustments of the stockpile have been made by both Republican and Democratic administrations in the past.

The saga about stockpile classification and declassification is also important because it exemplifies a deeply schizophrenic policy. On the one hand, the administration has declassified decades worth of formerly secret stockpile information, emphasizes the continued importance of nuclear weapons transparency to support nonproliferation and arms control efforts, and urges other nuclear weapons states to be more open about their arsenals. At the same time, the administration continues to keep secret the current size of the stockpile, which, among other effects, forces officials such as Dr. Cook to be unnecessarily vague about the extent to which the United States continues to make progress on reducing nuclear weapons in compliance with its obligations under the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Recommendations

If the administration believes that nuclear transparency is important, then it must continue to disclose stockpile numbers and avoid drifting back into automatic nuclear secrecy. It should also declassify how many weapons are dismantled each year and how many retired warheads are in storage awaiting dismantlement.

The Pentagon said in 2010 that it was looking at declassifying the number of weapons awaiting dismantlement, but so far nothing has happened.

The Nuclear Posture Review stated in 2010: “Today, there are several thousand nuclear warheads awaiting dismantlement, and this number will increase as weapons are removed from the stockpile under New START.” Actually, the New START Treaty does not require that nuclear warheads be removed from the stockpile, but the military will nonetheless probably retire the roughly 500 warheads assigned to the 48 SLBMs and 50 ICBMs that will be retired under the treaty.

We estimate that “several thousand” currently means about 3,000 retired warheads, and that 300-400 warheads are dismantled each year.

Declassification of the back-end (dismantlement numbers) of the nuclear posture goes hand in hand with declassification of the front-end (stockpile size) because dismantlement numbers prove that the United States is actually getting rid of the weapons and not just putting them in storage. That is the key message that unnecessary secrecy prevents U.S. officials from being able to convey to the international nonproliferation community.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Additional Delays Expected in B61-12 Nuclear Bomb Schedule

The B61-7, which completed a limited life-extension program in 2006, will be retired by the more extensive B61-12 program.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) expects additional delays in production and delivery of the B61-12 nuclear bomb as a result of so-called sequestration budget cuts.

During testimony before the Hours Energy and Water Subcommittee last week, NNSA’s Acting Administrator Neile Miller said an expected $600 million reduction of the agency’s weapons activities budget could “slow the B61-12 LEP” and other weapons programs.

The Nuclear Posture Review set delivery of the first B61-12 for 2017, but that timeline has since slipped to 2019. Miller did not say how long production could be delayed but it could potentially slip into the 2020s.

The B61 LEP is already the most expensive and complex warhead modernization program since the Cold War, with cost estimates ranging from $8 billion to more than $10 billion, up from $4 billion in 2010. The price hike has triggered Congressional questions and efforts to trim the program. B61-12 proponents argue the weapon is needed to provide extended nuclear deterrence to NATO and Asian allies, but the mission in Europe is fading out and a cheaper alternative could be to retaining the B61-7 for the B-2A bomber and retire other B61 versions.

The B61-12 program extends the life of the tactical B61-4 warhead, incorporates selected components from three other B61 versions (B61-3, B61-7, and B61-10), adds unknown new safety and security features, and adds a guided tail kit to increase the accuracy and target kill capability of the B61-12 compared with the B61-4.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Report: Reducing Alert Rates of Nuclear Weapons

.By Hans M. Kristensen

The United States and Russia have some 1,800 nuclear warheads on alert on ballistic missiles that are ready to launch in a few minutes, according to a new study published by UNIDIR. The number of U.S. and Russian alert warheads is greater than the total nuclear weapons inventories of all other nuclear weapons states combined.

The report Reducing Alert Rates of Nuclear Weapons is co-authored by Matthew McKinzie from the Natural Resources of Defense Council and yours truly.

France and Britain also keep some of their nuclear force on alert, although at lower readiness levels than the United States and Russia. No other nuclear weapon state has nuclear weapons on alert.

The report concludes that the warning made by opponents of de-alerting, that it could trigger a re-alerting race in a crisis that count undermine stability, is a “straw man” argument that overplays risks, downplays benefits, and ignores that current alert postures already include plans to increase readiness and alert rates in a crisis.

According to the report, “while there are risks with alerted and de-alerted postures, a re-alerting race that takes three months under a de-alerted posture is much preferable to a re-alerting race that takes only three hours under the current highly alerted posture. A de-alerted nuclear posture would allow the national leaders to think carefully about their decisions, rather than being forced by time constraints to choose from a list of pre-designated responses with catastrophic consequences.”

During his election campaign, Barack Obama promised to work with Russia to take nuclear weapons off “hair-trigger” alert, but the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) instead decided to keep the existing alert posture. The post-NPR review that has now been completed but has yet to be announced hopefully will include a reduction of the alert level, not least because the Intelligence Community has concluded that a Russian surprise first strike is unlikely to occur.

The UNIDIR report finds that the United States and Russia previously have reduce the alert levels of their nuclear forces and recommends that they continue this process by removing the remaining nuclear weapons from alert through a phased approach to ensure stability and develop consultation and verification measures.

Full report: Reducing Alert Rates of Nuclear Weapons (FAS mirror)

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Swiss Government. General nuclear forces research is supported by the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons Discussed in Warsaw

The conference was held in this elaborate room at the Intercontinental Warsaw hotel.

By Hans M. Kristensen

In early February, I participated in a conference in Warsaw on non-strategic nuclear weapons. The conference was organized by the Polish Institute of International Affairs, the Norwegian Institute for Defense Studies, and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. It was supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland, with the participation of the U.S. State Department.

The conference had very high-level government representation from the United States and NATO, and included non-governmental experts from the academic and think-tank communities in Russia and NATO countries. The Russian government unfortunately did not send participants.

The United States and NATO want to broaden the arms control agenda to non-strategic nuclear weapons, which have so far largely eluded limitations and verification. The objective of the conference was to try to identify options for how NATO and Russia might begin to discuss confidence-building measures and eventually limitations on non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The conference commissioned eight working papers to form the basis for the discussions. My paper, which focused on identifying common definitions for categories of non-strategic nuclear weapons, recommended starting with air-delivered weapons as the only compatible category for negotiations on U.S-Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons.

Background: Working papers and lists of participants are available on the PISM web site. For background on non-strategic nuclear weapons, see this FAS report.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Options for Reducing Nuclear Weapons Requirements

By Hans M. Kristensen

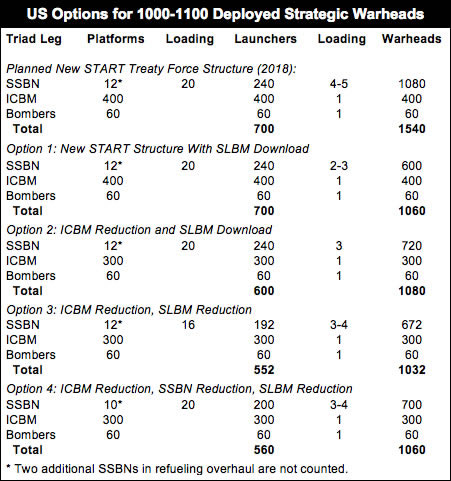

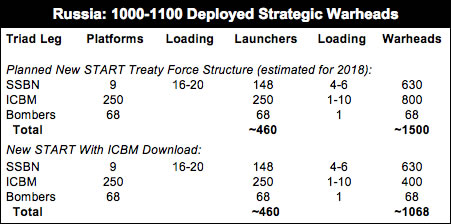

With the ink barely dry on the New START Treaty, Jeff Smith at the Center for Public Integrity reports that the Obama administration has determined that the United States can meet its national and international security requirements with 1,000-1,100 deployed strategic nuclear warheads – 450-550 warheads less than planned under the New START Treaty.

The administration is exploring how to get Russian agreement to the reductions without a new treaty, according to the New York Times. That would avoid a new agreement being held hostage to conservative Cold Warriors in Congress who fought ratification of the New START Treaty. Their efforts will be complicated by the fact that the U.S. military (and others) backs the reduced force level.

This is great news that reaffirms the administration’s commitment to continuing reducing excessive nuclear force levels. The fact that the new force level ended up closer to 1,000 than 1,200 warheads continues the 30 percent step-by-step reduction trend of the New START Treaty. The new initiative apparently also seeks reductions of non-deployed and non-strategic nuclear weapons, although it is unclear whether this is part of the first phase of the effort.

The lower force level has the potential to save billions of dollars, but how much depends on how the administration decides to implement it.

Reduction Options

The United States could meet the lower force level simply by reducing the warhead loading on ballistic missile submarines but without changing the force structure planned under the New START Treaty (see Table 1, Option 1). This would be a mistake because it would make it hard to convince Russia to join and it would save little money.

A more likely option would be to combine an ICBM reduction with a smaller SLBM download (Table 1, Option 2). That would reduce the ICBM force to 300 missiles and the overall force structure to 600 deployed launchers, or 100 less than under New START. Reducing the ICBM force to 300 from 400 planned under new START – a reduction of 150 from today’s 450 Minuteman III missiles – could be achieved by closing one of the three ICBM bases. A more likely option would be to spread job losses across the force by reducing the number of missile squadrons at each wing from three to two.

Another option would be to cut the ICBM force to 300 and reduce the missile loading on each SSBN from 20 planned under New START to 16, the same number planned for the next-generation SSBN (Table 1, Option 3). This option would reduce the force structure by nearly 150 deployed launchers below New START limit, thereby limiting the large advantage compared with Russia’s smaller force structure.

Yet another option could be to retire two SSBNs and reduce the ICBM force to 300. This option (Table 1, Option 4) would cancel the expensive refueling overhauls of the USS Wyoming (SSBN-742) and USS Louisiana (SSBN-743), retire the two submarines, and reduce the SSBN force to 12. Only 10 of those would be available for deployment.

How would a reduction to 1,000-1,100 deployed strategic warheads affect Russia’s posture? There are many uncertainties about how Russia’s missile forces will evolve over the next decade, but by the early 2020s the number of deployed missiles might decline to some 350 (down from around 450 today), or significantly less than the 700 permitted by the New START Treaty. So a new treaty would likely have little effect on reducing Russian deployed launchers.

The most important effect of a new limit of 1,000-1,100 deployed strategic warheads would be to reduce the warhead loading on Russia’s ICBMs. This is particularly important because Russia compensates for its smaller missile inventory by deployed more warheads on each missile. Again, the numbers are uncertain, but the lower warhead limit could potentially reduce Russian ICBM warheads by as much as 50 percent from roughly 800 estimated under the New START Treaty to approximately 400 warheads under the new reduced limit (see Table 2).

The only reason Russia would agree to this, it seems, is if the United States significantly reduced its deployed missiles and also reduced the number of warheads kept in reserve as a potential upload capability. The combination of a larger U.S. missile force with a large upload capacity is a significant breakout capability that undermines the changes of reaching a new agreement.

It is double important that a new agreement limits the upload capability because it could otherwise result in Russia also creating a “hedge” of non-deployed strategic warheads. Closing this “reconstitution” loophole in the arms reduction process is important for making nuclear reductions irreversible.

Effect on Role of Nuclear Weapons

How the reduced force level will reduce the role of nuclear weapons is yet unclear. President Obama stated in his Prague speech that he wanted to “put an end to Cold War thinking” by reducing “the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.”

We have yet to hear how the new guidance puts and end to Cold War thinking in the way the military is required to plan for the potential use of nuclear weapons. Smith’s article states that the lower deployed warhead level would be achieved by U.S. Strategic Command “targeting fewer, but more important, military or political sites in Russia, China, and several other countries.”

If so, that would appear to refer to what is known as “nodal targeting,” in which planners focus targeting with nuclear forces on the most important facilities rather than holding at risk all facilities within a target category. Nodal targeting has been used for the past two decades to reduce warhead requirements and focus the strategic nuclear war plan on effects rather than on creating rubble.

The current nuclear war plan (OPLAN 8010, Strategic Deterrence and Global Strike [/blog/ssp/2010/02/warplan.php]) is designed to hold at risk nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction (WMD) forces, command and control, military and political leadership, and war supporting industries of six potential adversaries: Russia, China, North Korea, Iran, Syria (a country that might be dropped from the plan soon, if it hasn’t happened already), and a non-state WMD attack.

|

| The Obama administration’s nuclear targeting review appears to have considered a nuclear targeting option similar to what we proposed in this study in 2009. |

Focusing nodal targeting more would not necessarily change how nuclear targeting is performed. Nor does a force level itself of 1,000-1,100 deployed strategic warheads suggest that the day-to-day alert level of the forces has been reduced significantly. Indeed, Smith’s story describes that the review considered, but rejected, a proposal by the State Department, National Security Council staff, and Vice President Biden’s staff to consider changing targeting policy more fundamentally:

“A much steeper reduction, to around 500 total warheads, was debated within the administration last year, but rejected, sources said. Known as the “deterrence only” plan, it would have aimed U.S. warheads at a narrower range of targets related to an enemy’s economic capacity and no longer emphasized striking the enemy’s leadership and weaponry in the first wave of an attack. […]

Some officials at the State Department, the NSC staff, and Vice president Biden’s staff urged consideration of the smaller arsenal and new targeting policy, officials said. But ‘a small brake’ was applied by the Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman, Army Gen. Martin E. Dempsey, who worried that making such a major policy change was too risky at a moment of upheaval in conventional military strategy, and would create too much uncertainty among allies, said one of the sources with knowledge of the discussion.”

This appears to refer to a targeting policy similar to the one FAS and NRDC proposed in our 2009 study From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence as a way of putting an end to Cold War thinking in nuclear planning. President Obama apparently “decided we did not need to do deterrence-only targeting now,” but did not rule it out for later.

Obviously, we have more work to do to put an end to Cold War thinking.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Trimming Nuclear Excess

Despite enormous reductions of their nuclear arsenals since the Cold War, the United States and Russia retain more than 9,100 warheads in their military stockpiles. Another 7,000 retired – but still intact – warheads are awaiting dismantlement, for a total inventory of more than 16,000 nuclear warheads.

This is more than 15 times the size of the total nuclear arsenals of all the seven other nuclear weapon states in the world – combined.

The U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals are far beyond what is needed for deterrence, with each side’s bloated force level justified only by the other’s excessive force level.

The FAS report – Trimming Nuclear Excess: Options for Further Reductions of U.S. and Russian Nuclear Forces – describes the status and 10-year projection for U.S. and Russian nuclear forces.

The report concludes that the pace of reducing nuclear forces appears to be slowing compared with the past two decades. Both the United States and Russia appear to be more cautious about reducing further, placing more emphasis on “hedging” and reconstitution of reduced nuclear forces, and both are investing enormous sums of money in modernizing their nuclear forces over the next decade.

Even with the reductions expected over the next decade, the report concludes that the United States and Russia will continue to possess nuclear stockpiles that are many times greater than the rest of the world’s nuclear forces combined.

New initiatives are needed to regain the momentum of the nuclear arms reduction process. The New START Treaty from 2011 was an important but modest step but the two nuclear superpowers must begin negotiations on new treaties to significantly curtail their nuclear forces. Both have expressed an interest in reducing further, but little has happened.

New treaties may be preferable, but reaching agreement on the complex inter-connected issues ranging from nuclear weapons to missile defense and conventional forces may be unlikely to produce results in the short term (not least given the current political climate in the U.S. Congress). While the world waits, the excess nuclear forces levels and outdated planning principles continue to fuel justifications for retaining large force levels and new modernizations in both the United States and Russia.

To break the stalemate and reenergize the arms reductions process, in addition to pursuing treaty-based agreements, the report argues, unilateral steps can and should be taken in the short term to trim the most obvious fat from the nuclear arsenals. The report includes 32 specific recommendations for reducing unnecessary and counterproductive U.S. and Russian nuclear force levels unilaterally and bilaterally.