Nuclear Missile Testing Galore

(Updated January 3, 2007)

(Updated January 3, 2007)

North Korea may have gotten all the attention, but all the nuclear weapon states were busy flight-testing ballistic missiles for their nuclear weapons during 2006. According to a preliminary count, eight countries launched more than 28 ballistic missiles of 23 types in 26 different events.

Unlike the failed North Korean Taepo Dong 2 launch, most other ballistic missile tests were successful. Russia and India also experienced missile failures, but the United States demonstrated a very reliable capability including the 117th consecutive successful launch of the Trident II D5 sea-launched ballistic missile.

The busy ballistic missile flight testing represents yet another double standard in international security, and suggests that initiatives are needed to limit not only proliferating countries from developing ballistic missiles but also find ways to curtail the programs of the existing nuclear powers.

The ballistic missile flight tests involved weapons ranging from 10-warhead intercontinental ballistic missiles down to single-warhead short-range ballistic missiles. Most of the flight tests, however, involved long-range ballistic missiles and the United States, Russia and France also launched sea-launched ballistic missiles (see table below).

|

Ballistic Missile Tests |

||

| Date | Missile | Remarks |

| China | ||

| 5 Sep | 1 DF-31 ICBM |

From Wuzhai, impact in Takla Makan Desert. |

| France | ||

| 9 Nov | 1 M51 SLBM | From Biscarosse (CELM facility), impact in South Atlantic. |

| India | ||

| 13 Jun | 1 Prithvi I SRBM |

From Chandipur, impact in Indian Ocean. |

| 9 Jul | 1 Agni III IRBM |

From Chandipur. Failed. |

| 20 Nov | 1 Prithvi I SRBM |

From Chandipur, impact in Indian Ocean. |

| Iran** | ||

| 23 May | 1 Shahab 3D MRBM |

From Emamshahr. |

| 3 Nov | 1 Shahab 3 MRBM, as well as “dozens” of Shahab 2, Scud B and other SRBMs |

Part of the Great Prophet 2 exercise. |

| North Korea*** | ||

| 4 Jul | 1 Taepo Dong 2 ICBM and 6 Scud C and Rodong SRBMs |

From Musudan-ri near Kalmo. ICBM failed. |

| Pakistan | ||

| 16 Nov | 1 Ghauri MRBM |

From Tilla? |

| 29 Nov | 1 Hatf-4 (Shaheen-I) SRBM |

Part of Strategic Missile Group exercise. |

| 9 Dec | 1 Haft-3 (Ghaznavi) SRBM |

Part of Strategic Missile Group exercise. |

| Russia | ||

| 28 Jul | 1 SS-18 ICBM | Attempt to launch satellite, but technically an SS-18 flight test (see comments below). |

| 3 Aug | 1 Topol (SS-25) ICBM |

From Plesetsk, impact on Kura range. |

| 7 Sep | 1 Bulava SLBM |

From Dmitry Donskoy (Typhoon) in White Sea. Failed. |

| 9 Sep | 1 SS-N-23 SLBM |

From K-84 (Delta IV) at North Pole, impact on Kizha range. |

| 10 Sep | 1 SS-N-18 SLBM |

From Delta III in Pacific, impact on Kizha range. |

| 25 Oct | 1 Bulava SLBM |

From Dmitry Donskoy (Typhoon) in White Sea. Failed. |

| 9 Nov | 1 SS-19 ICBM |

From Silo in Baykonur, impact on Kura range. |

| 21 Dec | 1 SS-18 ICBM |

From Orenburg, impact on Kura range. |

| 24 Dec | 1 Bulava SLBM |

From White Sea. Third stage failed. |

| United States | ||

| 16 Feb | 1 Minuteman III ICBM |

From Vandenberg AFB, impact Kwajalein. Final W87/Mk-21 SERV test flight. |

| Mar/Apr | 2 Trident II D5 SLBMs |

From SSBN. |

| 4 Apr | 1 Minuteman III ICBM |

From Vandenberg AFB, impact near Guam. Extended-range, single-warhead flight test. |

| 14 Jun | 1 Minuteman III ICBM |

From Vandenberg AFB, impact Kwajalein. Three-warhead payload. |

| 20 Jul | 1 Minuteman III ICBM |

From Vandenberg AFB, impact Kwajalein. Three-warhead flight test. Launched by E-6B TACAMO airborne command post. |

| 21 Nov | 2 Trident II D5 SLBMs |

From USS Maryland (SSBN-738) off Florida, impact in South Atlantic. |

| * Unreported events may add to the list. ** Iran does not have nuclear weapons but is suspected of pursuing nuclear weapons capability. *** It is unknown if North Korea has developed a nuclear reentry vehicle for its ballistic missiles. |

||

The Putin government’s reaffirmation of the importance of strategic nuclear forces to Russian national security was tainted by the failure of three consecutive launches of the new Bulava missile, but tests of five other missile types shows that Russia still has effective missile forces.

Along with China, Russia’s efforts continue to have an important influence on U.S. nuclear planning, and the eight Minuteman III and Trident II missiles launched in 2006 were intended to ensure a nuclear capability second to none. The first ICBM flight-test signaled the start of the deployment of the W87 warhead on the Minuteman III force.

China’s launch of the (very) long-awaited DF-31 ICBM and India’s attempts to test launch the Agni III raised new concerns because of the role the weapons likely will play in the two countries’ targeting of each other. But during a visit to India in June 2006, U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Peter Pace, downplayed at least the Indian issue saying other countries in the region also have tested missiles. In a statement that North Korea would probably find useful to use, Gen. Pace explained that “the fact that a country is testing something like a missile is not destabilizing” as long as it is “designed for defense, and then are intended for use for defense, and they have competence in their ability to use those weapons for defense, it is a stabilizing event.”

But since all “defensive” ballistic missiles have very offensive capabilities, and since no nation plans it defense based on intentions and statements anyway but on the offensive capabilities of potential adversaries, Gen. Pace’s explanation seemed disingenuous and out of sync with the warnings about North Korean, Iranian and Chinese ballistic missile developments.

The Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) seeks to limit the proliferation of ballistic missiles, but that vision seems undercut by the busy ballistic missile launch schedule demonstrated by the nuclear weapon states in 2006. Some MTCR member countries have launched the International Code of Conduct Against Ballistic Missile Proliferation initiative in an attempt to establish a norm against ballistic missiles, and have called on all countries to show greater restraint in their own development of ballistic missiles capable of delivering weapons of mass destruction and to reduce their existing missile arsenals if possible.

All the nuclear weapons states portray their own nuclear ballistic missile developments as stabalizing and fully in compliance with their pledge under the Non-Proliferation Treaty to pursue nuclear disarmament in good faith. But fast-flying ballistic missiles are inherently destablizing because of their vulnerability to attack may trigger use early on in a conflict. And the busy missile testing in 2006 suggests that the “good faith” is wearing a little thin.

Britain’s Next Nuclear Era

After having spent the last several years sending diplomats to Teheran to try to persuade Iran not to develop nuclear weapons, the British government announced Monday that it plans to renew its own nuclear arsenal.

If approved by the parliament, Monday’s decision means that the United Kingdom will extend its nuclear deterrent beyond 2050, essentially doubling the timeline of its own nuclear era.

Doing so is entirely consistent with the United Kingdom’s international obligations under the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and with a policy that favors complete elimination of nuclear weapons, the government insisted in a fact sheet, because the British nuclear arsenal today is smaller than during the Cold War, and because the Treaty does not say exactly when nuclear disarmament has to be accomplished. In fact, the new plan has “the right balance,” the government claims, between working for a world free of nuclear weapons and keeping those weapons.

The Reduction

Probably in acknowledgment that it will be a hard sell domestically and internationally, the $40 billion nuclear plan was sweetened with an announcement that Britain will reduce the number of “operationally available warheads” from fewer than 200 today to fewer than 160 at some future date.

The gesture is somewhat hollow, however, because Britain only has enough Trident D5 missiles to arm three of its four SSBNs with a maximum of 144 warheads anyway. The Blair government previously decided in 1998 to purchase only 58 missiles instead of 65. Since then, eight missiles have been used in operational test launches, leaving 50 missiles in the inventory – barely enough to fill the tubes of three SSBNs.

The British government has stated that the single SSBN on patrol at any given time carries “up to 48” warheads, a statement that partly reflects that some of the missiles have been given a “substrategic” mission, probably with only one warhead each. Depending on the number of substrategic mission missiles carried, the actual loading of the patrolling submarine probably is 36-44 warheads. Assuming a similar loading for the other two SSBNs for which there are missiles available, the estimated number of warheads needed for the British SSBN fleet since the substrategic mission first became operational in 1996 is 108-132 warheads.

The announcement to retain “fewer than 160” operationally available warheads seems to reflect this existing reality rather than an additional operational reduction. But it raises the question why the British government for the past eight years has retained 20 percent more warheads than it actually needed.

The Catch

The plan to replace the submarines comes with a catch: Half-way through their service-life, the missiles will expire, necessitating further investment to purchase new missiles and possibly also new warheads. The U.K. government has already received, the White Paper states, assurance from the U.S. government that Britain can be a partner if the United States later decides to build a successor to the D5 missile, and that such a missile will be compatible, or can be made compatible, with Britain’s new SSBNs.

The Warheads

The type of warhead deployed on Britain’s D5 missiles will last at least into the 2020, according to the White Paper. But the U.K. government says it doesn’t yet know whether the warhead can be “refurbished” to last longer, or whether it will be necessary to develop a replacement warhead. The next Parliament will have to make that decision, the government says, an option that of course will be harder to reject if a decision has already been made to build the new submarines.

How British are the warheads on the British SSBN fleet? The Ministry of Defence stated in a fact sheet that the warheads on the D5 missiles were “designed and manufactured in the U.K.” Even so, rumors have persisted for years that the warheads are in fact modified U.S. W76 warheads.

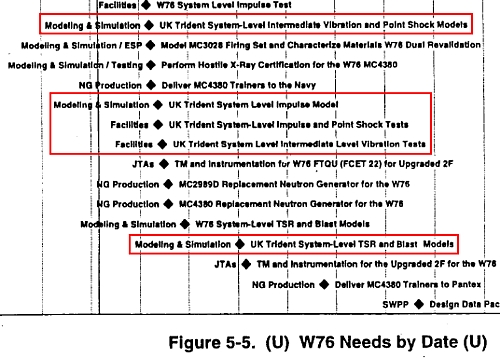

Now a U.S. Department of Energy document – declassified after eight years of processing – directly links the warhead designs on U.S. and U.K. Trident missiles. The document shows that the “U.K. Trident System,” as the British warhead modification is called, is similar enough to the U.S. W76 warhead to make up an integral part of the W76 engineering, design and evaluation schedule (see figure below).

|

How British is Britain’s Nuclear Warhead? |

|

| The British Trident warhead is similar enough to the U.S. W76 to form an integral part of the U.S. Department of Energy’s “W76 Needs” schedule, according to this document declassified and released under the Freedom of Information Act. The document directly links the warhead designs on U.S. and U.K. Trident missiles. To download a PDF-copy of the declassified document, click here. |

Specifically, the document shows that between 1999 and 2001, work on five of 13 “W76 needs” involved the “U.K. Trident System.” These activities included vibration and point shock models, impulse models, impulse and point shock tests, vibration tests, as well as “TSR [thermostructural response] and Blast Models.”

The activities listed in the chronology are contained in a detailed database that “maps the requirements and capabilities for replacement subsystem and component modeling development, test, and production to the specific organizations tasked with meeting these requirements.”

The “U.K. Trident System” is thought to consist of a 100-kiloton thermonuclear warhead encased in a cone-shaped U.S. Mark-4 reentry vehicle. The W76 is the most numerous warhead (approximately 3,200) in the U.S. stockpile. Built between 1978 and 1988, about a third of the W76s are being modified as the W76-1 (see figure below) and equipped with a new fuze with ground-burst capability to “enable the W76 to take advantage of the higher accuracy of the D5” against harder targets. Delivery of the first W76-1 is scheduled for 2007 and the last in 2012. The W76 is also the first warhead scheduled to be modified under the proposed Reliable Replacement Warhead program.

|

The W76 |

|

| This is believed to be the first publicly available picture of the W76. It shows the four First Production Units of the modified W76-1/Mk4A reentry vehicle. The British version of the W76 probably looks similar. Source: Sandia National Laboratories. |

The Nuclear Mission

The U.K. government presents several specific military and political justifications for why it intends to double Britain’s nuclear era.

One is that none of the other nuclear weapon states are even considering getting rid of their nuclear weapons, but instead are modernizing – some even increasing – their nuclear arsenals.

Another justification is that North Korea and Iran are pursuing nuclear weapons too, and that some countries might even “sponsor nuclear terrorism from their soil.”

Finally, the world is an uncertain and risky place, the White Paper concludes, and adds that it is “not possible to accurately predict the global security environment over the next 20 to 50 years.”

Those who question that these justifications are sufficient to retain the nuclear deterrent, Prime Minister Tony Blair writes in the foreword of the White Paper, “need to explain why disarmament by the U.K. would help our security.”

Analysis

The White Paper fails to identify a specific, urgent mission for British nuclear weapons. Instead, the justification to keep them seems like a little of everything: A couple of Cold War leftovers (Russia is still looming on the horizon and China might rise), a little sheep mentality (the other nuclear powers won’t give them up either), a little mission-creep (we might have to use them against proliferators), and a little hype (a role against terrorists). All of this is wrapped in the popular post-Cold War mantra that claims that the world suddenly is very uncertain and impossible to predict. As Prime Minister Tony Blair told the Parliament Monday:

“It is just that, in the final analysis, the risk of giving up something that has been one of the mainstrays of our security since the war [World War II], and moreover doing so when the one certain thing about our world today is its uncertainty, is not a risk I feel we can reasonably take.” The world has changed “beyond recognition,” and “it is precisely because we could not have recognized then, the world we live in now, that it would not be wise to predict the unpredictable in the times to come.”

Of course, it is one thing to argue that Britain needs a nuclear bomb in the basement or a mothballed nuclear production capability just in case. It is quite another to claim that strategic submarines need to continue to hide deep in the oceans much like they did during the Cold War without an urgent threat against the survival of the nation.

That’s for the U.K. Parliament to debate in the next months, followed – presumably – by a decision whether to approve the government’s plan sometime in 2007.

Background: MOD White Paper and Fact Sheets | British Nuclear Forces, 2005

British Parliament Report Criticizes Government Refusal to Participate in Nuclear Deterrent Inquiry

Although the British government has promised a full and open public debate about the future of Britain’s nuclear deterrent, it has so far failed to explain what decisions need to be made, failed to provide a timetable for those decisions, and has refused to participate in a House of Commons Defence Committee inquiry on the future of Britain’s nuclear deterrent, according to a British parliamentary report. The report partially relies on research conducted by the FAS Nuclear Information Project for the SIPRI Yearbook.

Although the British government has promised a full and open public debate about the future of Britain’s nuclear deterrent, it has so far failed to explain what decisions need to be made, failed to provide a timetable for those decisions, and has refused to participate in a House of Commons Defence Committee inquiry on the future of Britain’s nuclear deterrent, according to a British parliamentary report. The report partially relies on research conducted by the FAS Nuclear Information Project for the SIPRI Yearbook.