New Report: Reducing Alert Rates of Nuclear Weapons

.By Hans M. Kristensen

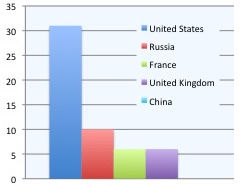

The United States and Russia have some 1,800 nuclear warheads on alert on ballistic missiles that are ready to launch in a few minutes, according to a new study published by UNIDIR. The number of U.S. and Russian alert warheads is greater than the total nuclear weapons inventories of all other nuclear weapons states combined.

The report Reducing Alert Rates of Nuclear Weapons is co-authored by Matthew McKinzie from the Natural Resources of Defense Council and yours truly.

France and Britain also keep some of their nuclear force on alert, although at lower readiness levels than the United States and Russia. No other nuclear weapon state has nuclear weapons on alert.

The report concludes that the warning made by opponents of de-alerting, that it could trigger a re-alerting race in a crisis that count undermine stability, is a “straw man” argument that overplays risks, downplays benefits, and ignores that current alert postures already include plans to increase readiness and alert rates in a crisis.

According to the report, “while there are risks with alerted and de-alerted postures, a re-alerting race that takes three months under a de-alerted posture is much preferable to a re-alerting race that takes only three hours under the current highly alerted posture. A de-alerted nuclear posture would allow the national leaders to think carefully about their decisions, rather than being forced by time constraints to choose from a list of pre-designated responses with catastrophic consequences.”

During his election campaign, Barack Obama promised to work with Russia to take nuclear weapons off “hair-trigger” alert, but the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) instead decided to keep the existing alert posture. The post-NPR review that has now been completed but has yet to be announced hopefully will include a reduction of the alert level, not least because the Intelligence Community has concluded that a Russian surprise first strike is unlikely to occur.

The UNIDIR report finds that the United States and Russia previously have reduce the alert levels of their nuclear forces and recommends that they continue this process by removing the remaining nuclear weapons from alert through a phased approach to ensure stability and develop consultation and verification measures.

Full report: Reducing Alert Rates of Nuclear Weapons (FAS mirror)

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Swiss Government. General nuclear forces research is supported by the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

New Nuclear Notebook: British Nuclear Forces 2011

|

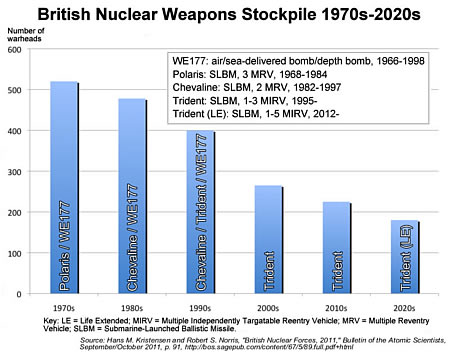

| The British Cold War stockpile was bigger than previously thought but will be the smallest of the five original nuclear weapons states by the mid-2020s. Click image for bigger version |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Britain’s disclosure last year of the size of its nuclear weapons stockpile shows, when combined with official information released earlier, that its Cold War nuclear stockpile was bigger than previously thought – more than 500 nuclear warheads in the 1970s.

Since then, Britain has reduced its stockpile by more than half to approximately 225 warheads and has decided to reduce it further to 180 warheads by the mid-2020s, a reduction of two-thirds compared with the Cold War level.

Modernization and continuous deployment at sea continues, however, and current plans might ironically lead to an increase in the number of warheads carried on each operational missile.

This and more is described in our latest Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

See also: Previous British Nuclear Notebook from 2005

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

British Submarines to Receive Upgraded US Nuclear Warhead

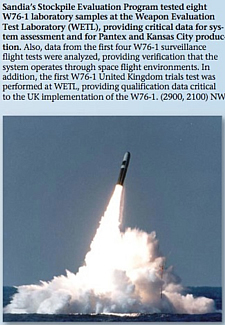

Sea-launched ballistic missiles on British ballistic missile submarines will be armed with the upgraded W76-1 nuclear warhead currently in production in the United States, according to a report from Sandia National Laboratories.

According to the Labs Accomplishments from March 2011, “the first W76-1 United Kingdom trials test was performed at WETL [Weapon Evaluation Test Laboratory], providing qualification data critical to the UK implementation of the W76-1.”

The Royal Navy plans to “integrate” the US W76-1/Mk4A warhead onto British SSBNs.

Rumors have long existed that the nuclear warhead currently used on British sea-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) is very similar to the U.S. W76 warhead deployed on American SLBMs. Official sources normally don’t give U.S. warhead designations for the British warhead but use another name. A declassified document published by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) in 1999, which I published in 2008, described maintenance work on the W76 warhead but called the British version the “UK Trident System.”

|

| Labs Accomplishments from Sandia National Laboratories describes “the first W76-1 United Kingdom trial test” and “UK implementation of the W76-1.” Download the publication here. |

The Sandia report, on the contrary, explicitly uses the U.S. warhead designation for the warhead on British SLBMs: W76-1.

Approximately 1,200 W76-1s are current in production at the Pantex Plant in Texas. The W76-1 is an upgraded version of the W76-0 (or simply W76) produced between 1978 and 1987. In its full configuration, the upgraded weapon is known as the W76-1/Mk4A, where the Mk4A is the designation for the cone-shaped reentry body that contains the W76-1 warhead.

After first denying it, the British government has since confirmed that the Mk4A reentry body is being integrated onto the British SLBMs but it has been unclear which warhead it will carry: the existing warhead or the new W76-1. The Sandia report appears to show that the United Kingdom will get the full package: W76-1/Mk4A.

HMS Vanguard launches US-supplied Trident II D5 SLBM off Florida in October 2005. In the future, missiles on British submarines will carry US-supplied W76-1/Mk4A nuclear warheads.

The upgrade extends the service life by another 30 years to arm U.S. and British nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) through the 2040s. That timeline fits the 2010 British Strategic Defence Review finding that “a replacement warhead is not required until at least the 2030s.”

|

| HMS Vanguard launches US-supplied Trident II D5 SLBM off Florida in October 2005. In the future, missiles on British submarines will carry US-supplied W76-1/Mk4A nuclear warheads. |

.

The transfer of W76-1/Mk4A warheads to the United Kingdom further erodes British claims about having an “independent” deterrent. The missiles on the SSBNs are leased from the U.S. Navy, the missile compartment on the next-generation SSBN will be supplied by the United States, and new reactor cores that last the life of future submarines hint of substantial U.S. nuclear assistance.

The transfer of nuclear technology from the United States to Britain is authorized by the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defense Agreement, which was most recently updated in 2004 and extended through 2014 to permit the “transfer of nonnuclear parts, source, byproduct, special nuclear materials, and other material and technology for nuclear weapons and military reactors” between the two countries. The will text is secret but a reconstructed version is here (see note 3).

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Nick Ritchie at Bradford University (“US-UK Special Relationship”) and John Ainslie at Scottish CND.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Britain Discloses Size of Nuclear Stockpile: Who’s Next?

|

| Britain says it has 225 nuclear warheads for its Trident submarine fleet. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The new British government today followed the French and U.S. examples by disclosing its total military stockpile of nuclear weapons.

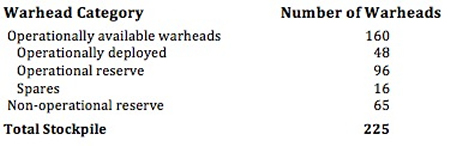

Foreign Secretary William Hague told the House of Commons that “the total number of warheads” in the “overall stockpile” will not exceed 225. Of those, “up to 160” are “operationally available” for deployment on Trident II missiles on British ballistic missile submarines.

The Royal Navy possesses four Vanguard-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), each of which can carry up to 16 U.S.-supplied Trident II long-range ballistic missiles. Each missile is thought to carry up to three UK-produced warheads closely resembling the U.S. 100-kt W76 warhead.

Stockpile and Arsenal

Whereas the United States declassified its entire stockpile history, the British government has only disclosed the current size of its stockpile, and only in the somewhat cryptic way: “the overall stockpile…will not exceed 225 warheads.”

That presumably means the stockpile actually contains 225 warheads, not that it might be smaller but “not exceed 225 warheads” even in the future.

That is 25 warheads more than the 200 Robert Norris and I have estimated in the past.

Of the 225 warheads, the government stated that it “will retain up to 160 operationally available warheads,” or as many as 71 percent of the entire inventory. There are only spaces for 144 warheads on Britain’s 50 Trident II SLBMs, of which 48 can be deployed on three operational SSBNs. The fourth boat is in refit at any given time and is not allocated missiles.

| British Nuclear Weapons Stockpile 2010 |

|

| With the British government’s declaration, it’s possible to make an estimated breakdown of the categories of nuclear warheads in the British stockpile. |

.

The “up to 160” probably refers to the 144 spaces plus a small number of spare warheads. The number of spares might increase if an SSBN deploys with less than its maximum capacity of 48 warheads. The remaining 65 warheads in the stockpile are for what is described as “routine processing, maintenance and logistic management.”

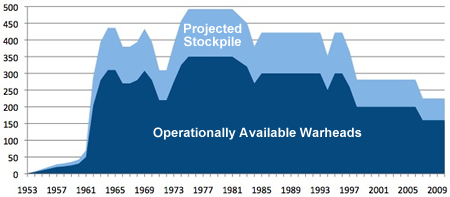

It is not yet possible to plot the history of the British nuclear stockpile with certainty. But if one assumes that the ratio of warheads in the non-operational reserve to the operationally available inventory has been roughly the same as today (approximately 1 x 2.5), then a simplistic projection of the stockpile looks like this:

| British Nuclear Weapons Stockpile 1953-2010 |

|

| The history of the British stockpile is unknown, but assuming the same percentage of warheads in reserve as today, a preliminary history can be plotted. |

.

The stockpile fluctuated considerably over the years with introduction and retirement of various weapon systems. The stockpile reached a peak in the late 1970s at nearly 500 warheads. After the Cold War, the stockpile decreased with the retirement of the WE-177 non-strategic nuclear bombs and depth charges for use by the air force and surface fleet. The last of the WE-177s was dismantled in August 1998.

Who’s Next?

Three of the five original nuclear weapon states have now disclosed the sizes of their military stockpiles of nuclear warheads. The pressure is increasing on the other nuclear weapon states to follow the good example.

The size of the Russian stockpile is unknown but Norris and I estimate Russia possesses 12,000 nuclear warheads, of which 4,600 might be operational. A Russian official recently told Reuters that Russia after ratification of the New START agreement “will likewise be able to consider disclosing the total number of Russia’s deployed strategic delivery vehicles and the warheads they can carry.” That would not be disclosing the size of the stockpile, but still be progress.

China’s stockpile is even more opaque, although Norris and I estimate it at approximately 240 warheads. That fits well with the declaration made by former British Defense Minister Des Browne in 2007, that the United Kingdom has “the smallest stockpile of any of the nuclear weapon states recognised under the NPT.”

Declarations from Indian and Pakistani would also be greatly welcomed. Israel is obviously a little more complicated because, well, it has yet to acknowledge that it has nuclear weapons, and North Korea doesn’t seem in the mood for goodwill gestures these days.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Estimated Nuclear Weapons Locations 2009

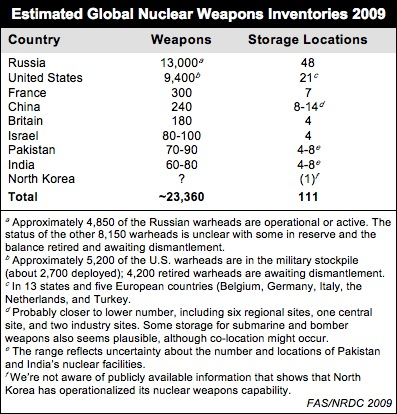

Some 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at 111 locations around the world

.The world’s approximately 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at an estimated 111 locations in 14 countries, according to an overview produced by FAS and NRDC.

Nearly half of the weapons are operationally deployed with delivery systems capable of launching on short notice.

The overview is published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and includes the July 2009 START memorandum of understanding data. A previous version was included in the annual report from the International Panel of Fissile Materials published last month.

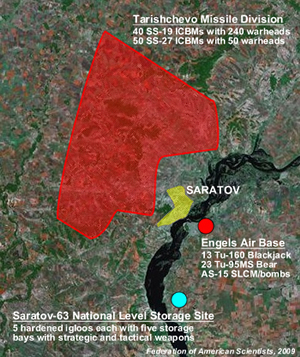

More than 1,000 nuclear weapons surround Saratov.

Russia has an estimated 48 permanent nuclear weapon storage sites, of which more than half are on bases for operational forces. There are approximately 19 storage sites, of which about half are national-level storage facilities. In addition, a significant number of temporary storage sites occasionally store nuclear weapons in transit between facilities.

This is a significant consolidation from the estimated 90 Russian sites ten years ago, and more than 500 sites before 1991.

Many of the Russian sites are in close proximity to each other and large populated areas. One example is the Saratov area where the city is surrounded by a missile division, a strategic bomber base, and a national-level storage site with probably well over 1,000 nuclear warheads combined (Figure 2).

The United States stores its nuclear weapons at 21 locations in 13 states and five European countries. This is a consolidation from the estimated 24 sites ten year ago, 50 at the end of the Cold War, and 164 in 1985 (see Figure 3).

Approximately 50 B61 nuclear bombs inside an igloo at what might be Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada. Seventy-five igloos at Nellis store “one of the largest stockpile in the free world,” according to the U.S. Air Force, one of four central storage sites in the United States.

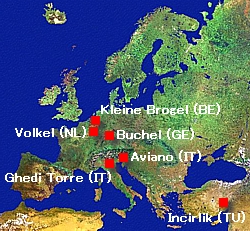

Europe has about the same number of nuclear weapon storage locations as the Continental United States, with weapons scattered across seven countries. This includes seven sites in France and four in Britain. Five non-nuclear NATO countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey) still host U.S. nuclear weapons first deployed there during the Cold War.

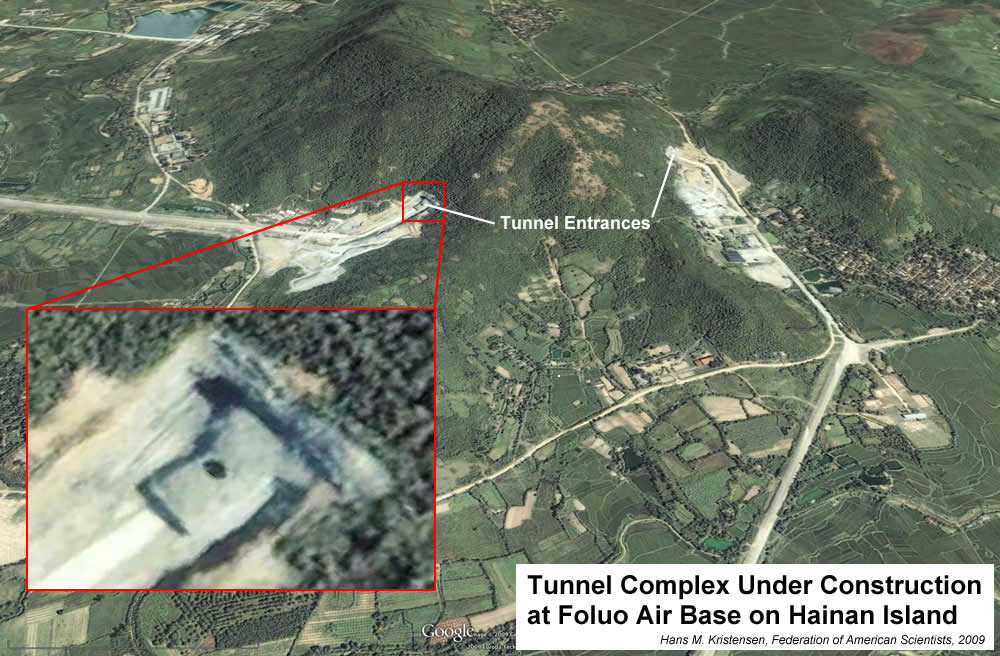

We estimate that China has 8-14 facilities associated with nuclear weapons, most likely closer to the lower number, near bases with units that operate nuclear missiles or aircraft. None of the weapons are believed to be fully operational but stored separate from delivery vehicles at sites controlled by the Central Military Commission.

Where does China store nuclear warheads for its ballistic missile submarines? The naval base near Julin on Hainan Island has extensive underground facilities. An alternative to the base itself could potentially be a facility elsewhere on the island, such as Foluo Air Base where construction of an underground facility began five years before the first SSBN arrived at Hainan. Or are the weapons stored on the mainland? Click image to enlarge.

Israel probably has about four nuclear sites, whereas the nuclear storage facilities in India and Pakistan are – despite many rumors – largely undetermined. All three countries are thought to store warheads separate from delivery vehicles.

Despite two nuclear tests and many rumors, we are unaware of publicly available evidence that North Korea has operationalized its nuclear weapons capability.

Warhead concentrations vary greatly from country to country. With 13,000 warheads at 48 sites, Russian stores an average of 270 warheads at each location. The U.S. concentration is much higher with an average of 450 warheads at each location. These are averages, however, and in reality the distribution is thought to be much more uneven with some sites only storing tens of warheads.

Finally, a word of caution is in order: estimates such as these obviously come with a great deal of uncertainty, as we don’t have access to classified intelligence estimates. Based on publicly available information and our own assumptions we have nonetheless produced a best estimate that we hope will assist the public debate. Comments and suggestions are encouraged so we can adjust the overview in the future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Russian Tactical Nuclear Weapons

|

| New low-yield nuclear warheads for cruise missiles on Russia’s submarines?. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Two recent news reports have drawn the attention to Russia’s tactical nuclear weapons. Earlier this week, RIA Novosti quoted Vice Admiral Oleg Burtsev, deputy head of the Russian Navy General Staff, saying that the role of tactical nuclear weapons on submarines “will play a key role in the future,” that their range and precision are gradually increasing, and that Russia “can install low-yield warheads on existing cruise missiles” with high-yield warheads.

This morning an editorial in the New York Times advocated withdrawing the “200 to 300” U.S. tactical nuclear bombs deployed in Europe “to make it much easier to challenge Russia to reduce its stockpile of at least 3,000 short-range weapons.”

Both reports compel – each in their own way – the Obama administration to address the issue of tactical nuclear weapons.

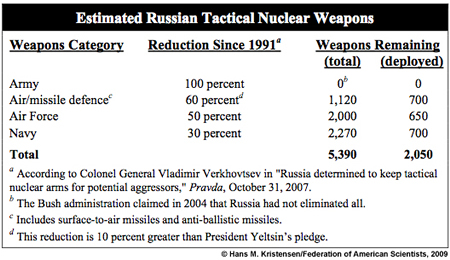

The Russian Inventory

Like the United States, Russia doesn’t say much about the status of its tactical nuclear weapons. The little we have to go by is based on what the Soviet Union used to have and how much Russian officials have said they have cut since then.

Unofficial estimates set the Soviet inventory of tactical nuclear weapons at roughly 15,000 in mid-1991. In response to unilateral cuts announced by the United States in late 1991 and early 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin pledged in 1992 that production of warheads for ground-launched tactical missiles, artillery shells, and mines had stopped and that all such warheads would be eliminated. He also pledged that Russia would dispose of half of all airborne and surface-to-air warheads, as well as one-third of all naval warheads.

In 2004, the Russian Foreign Ministry stated that “more than 50 percent” of these warhead types have been “liquidated.” And in September 2007, Defense Ministry official Colonel-General Vladimir Verkhovtsev gave a status report of these reductions that appeared to go beyond President Yeltsin’s pledge.

Based on this, Robert Norris and I make the following cautious estimate (to be published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in late April) of the current Russian inventory of tactical nuclear weapons:

|

| Estimate from forthcoming Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. |

.

Based on the number of available nuclear-capable delivery platforms, we estimate that nearly two-thirds of these warheads are in reserve or awaiting dismantlement. The remaining approximately 2,080 warheads are operational for delivery by anti-ballistic missiles, air-defence missiles, tactical aircraft, and naval cruise missiles, depth bombs, and torpedoes. The Navy’s tactical nuclear weapons are not deployed at sea under normal circumstances but stored on land.

The Other Nuclear Powers

The United States retains a small inventory of perhaps 500 active tactical nuclear weapons. This includes an estimated 400 bombs (including 200 in Europe) and 100 Tomahawk cruise missiles (all on land). Others, perhaps 700, are in inactive storage.

France also has 60 tactical-range cruise missiles, including some on its aircraft carrier, although it calls them strategic weapons.

The United Kingdom has completely eliminated its tactical nuclear weapons, although it said until a couple of years ago that some of its strategic Trident missiles had a “sub-strategic” mission.

Information about possible Chinese tactical nuclear weapons is vague and contradictory, but might include some gravity bombs.

India, Pakistan, and Israel have some nuclear weapons that could be considered tactical (gravity bombs for fighter-bombers and, in the case of India and Pakistan, short-range ballistic missiles), but all are normally considered strategic.

| Russian Nuclear-Capable Cruise Missile Launch |

|

| A nuclear-capable SS-N-19 Shipwreck cruise missile is launched from a Kirov-class nuclear-powered guided missile cruiser. The ship is equipped with 20 launchers for the SS-N-19 missile, which can carry a 500-kiloton warhead. Other tactical nuclear weapon systems include the SS-N-16 anti-submarine rocket, and the SA-N-6 anti-air missile. |

.

Implications and Issues

Whether Vice Admiral Burtsev’s statement is more than boasting remains to be seen, but it is a timely reminder to the Obama administration of the need to develop a plan for how to tackle the tactical nuclear weapons.

Russia’s nuclear posture is now approaching a situation where there are more tactical nuclear weapons in the inventory than strategic weapons. And NATO’s remnant of the Cold War tactical nuclear posture in Europe seems stuck in the mud of nuclear dogma and bureaucratic inaction.

None of these tactical nuclear weapons are limited or monitored by any arms control agreements, and – for all the worries about terrorists stealing nuclear weapons – are the most easy to run away with.

In April, NATO is widely expected to kick off a (long-overdue) review of its Strategic Concept from 1999. It would be a mistake to leave the initiative on what to do with the tactical nuclear weapons to the NATO bureaucrats. The vision must come from the top and President Obama needs to articulate what it is soon.

U.S. Strategic Submarine Patrols Continue at Near Cold War Tempo

|

| U.S. ballistic missile submarines conducted 31 nuclear deterrent patrols in 2008 at an operational tempo comparable to that of the Cold War. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen [updated]

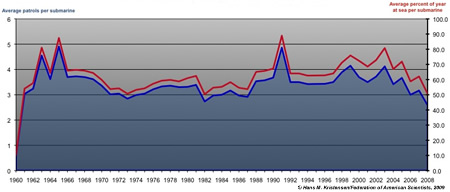

The U.S. fleet of 14 nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines conducted 31 nuclear deterrent patrols in 2008 at an operational tempo comparable to during the Cold War.

The new patrol information, which was obtained from the U.S. Navy under the Freedom of Information Act, coincides with the completion on February 11, 2009, of the 1,000th deterrent patrol by an Ohio-class submarine since 1982.

The information shows that the United States conducts more nuclear deterrent patrols each year than Russia, France, United Kingdom and China combined.

Patrols by the Number

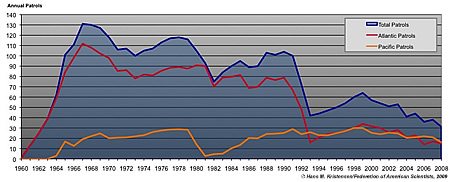

The 31 patrols conducted in 2008 top a 48-year history of continuous deterrent patrols. Since the USS George Washington (SSBN-598) departed Charleston, S.C., on the first nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) patrol on November 15, 1960, 59 SSBNs have conducted 3,814 patrols through 2008 (see Figure 1).

.

The annual number of patrols has fluctuated considerably over the years, peaking at 131 patrols in 1967. Declines occurred mainly due to retirement of SSBNs rather than changes in the mission. The retirement of the early classes of SSBNs in 1979-1981 almost eliminated patrols in the Pacific, but the new Ohio-class gradually rebuilt the posture. The stand-down of Poseidon SSBNs in October 1991 and the retirement of all non-Ohio-class SSBNs by 1993 reduced Atlantic patrols by nearly 60 percent. The patrols increased again in the second half of the 1990s and more Ohio-class SSBNs were added to the fleet, but started dropping from 2000 as four Ohio-class SSBNs were withdrawn from nuclear missions and four others underwent lengthy backfits from the Trident I C4 to the Trident II D5 Trident missile.

|

Figure 2: |

|

|

The United States conducts more SSBN patrols than all other nuclear powers combined. China’s SSBNs have yet to conduct a deterrent patrol. |

During the Cold War standoff with the Soviet Union, the vast majority of patrols were done in the Atlantic Ocean. Since the early 1990s, patrols in the Atlantic have plummeted and the SSBN force been concentrated on the west coast. The majority of U.S. SSBN patrols today occur in the Pacific.

The current number of patrols is significantly greater than the patrol levels of other countries with sea-based nuclear weapon systems. In fact, the U.S. navy conducted three times the number of SSBN patrols that the Russian navy did in 2008, and more patrols than Russia, France, Britain and China combined (see figure 2).

High Operational Tempo

Although the total annual number of SSBN patrols has decreased significantly since the end of the Cold War, the operational tempo of each submarine has not. Each Ohio-class SSBNs today conducts about the same number of patrols per year as during the Cold War, but the duration of each patrol has increased, with each submarine spending approximately 50-60 percent of its time on patrol (see Figure 3).

.

The high operational tempo is made possibly by each SSBN having two crews, Blue and Gold. Each time a submarine returns from a patrol, the other crew takes over, spends a few weeks repairing and replenishing the boat, and takes the SSBN out for its next patrol.

The data also reveals a couple of interesting spikes of increased patrols in 1963/1965 and 1991. The reasons for this increased activity is not known but the periods coincide with the Cuban missile crisis and the failed coup attempt in the final days of the Soviet Union in 1991.

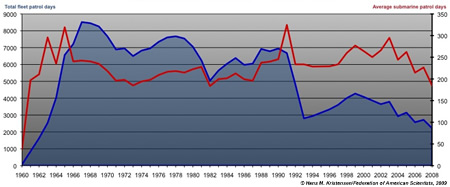

Another way to examine the data is to see how may patrol days each submarine and the fleet accumulate each year. During the Cold War the larger submarine fleet averaged approximately 6,000 patrol days each year, with a peak of 8,515 patrol days in 1967. That performance declined to an average of 3,400 days in the post-Cold War era as the size of the SSBN fleet was reduced. With the removal of four SSBNs from nuclear operations and four others undergoing lengthy missile backfits, the fleet’s total patrol days has now dropped to a little over 2,200 (see figure 4).

.

Yet total patrol day numbers can be deceiving because they can obscure how each submarine is doing. Because the Ohio-class SSBN design was optimized for lengthy deterrent patrols, the average number of days each submarine spends on patrol has been higher in the post-Cold War period than during the Cold War itself. Patrols can be shortened by technical problems, but many Ohio-class submarines today stay on patrol for more than 80 days. Last year, the USS Maine (SSBN-741) conducted a 98-day patrol in the Pacific.

What is a Deterrent Patrol?

An SSBN deterrent patrol is an extended operational deployment during part of which the submarine covers its assigned target package in support of the strategic war plan. Each Ohio-class patrol typically lasts 60-90 days, but one submarine in late 2008 conducted an extended patrol of 98 day and patrols have occasionally exceeded 100 days. Occasionally a patrol is cut short by technical problems, in which case another SSBN can be deployed on short notice. As a result, patrols today in average last about 72 days.

Being on patrol does not mean the submarine is continuously submerged on-station and holding targets at risk. In fact, when the submarine is not on Hard Alert holding targets at risk in Russia, China, or regional states, much of the patrol time is spent on cruising between homeport, patrol areas, exercising with other naval forces, undergoing inspections and certifications, performing Weapon System Readiness Tests (WSRTs), conducting retargeting exercises, and Command and Control exercises.

Another activity involves so-called SCOOP exercises (SSBN Continuity of Operations Program) where the SSBN will practice replenishment or refit in forward ports in case the homeport is annihilated in wartime. In the Pacific, the SCOOP ports include Pearl Harbor, Hawaii (see Figure 5), Guam, Seaward, Alaska, Astoria, Oregon, and San Diego, California. In the Atlantic they include Port Canaveral and Mayport, Florida, Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico, and Halifax, Canada. The SSBN may even return to its homeport and redeploy a day or two later on the same patrol.

|

Figure 5: |

|

| USS Henry M. Jackson (SSBN-730) loading fresh fruit in Pearl Harbor during a SCOOP visit to Hawaii in March 2008 on its first patrol after a four-year overhaul where it was refueled and modernized to carry the Trident II D5 ballistic missile. |

.

Although patrols normally end at the base where they started, this is not always the case. An SSBN that departs Naval Submarine Base Bangor, Washington, might go on-station for several weeks in alert operational areas, conduct various training and exercises, and then arrive at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. After a brief port visit and replenishment the submarine typically resumes its patrol and eventually returns to Bangor. But sometimes the patrol will end in Hawaii, a new crew be flown in to replace the old, and the submarine undergo refit at the forward location as part of a SCOOP exercise. The SSBN then departs Hawaii on a new patrol, goes on-station in alert operational areas, conducts more exercises and inspections, and eventually returns to Bangor where the new patrol ends.

This type of broken up patrol where the submarine is allowed to do more than on-station operations is sometimes described as “modified alert” and said to be different from the Cold War. But SSBNs have never been on-station all the time, with most deployed submarines being in transit between on-station alert areas and other non-alert operations. In fact, “modified alert” patrols date back to the early 1970s.

Of the 14 SSBNs currently in the fleet, two are normally in overhaul at any given time. Of the remaining operational 12 submarines, 8-9 are deployed on patrol at any given time. Four of these (two in each ocean) are on “Hard Alert” while the 4-5 non-alert SSBNs can be brought to alert level within a relatively short time if necessary. One to three SSBNs are in refit at the home base in preparation for their next patrol.

The SSBNs on Hard Alert continuously hold at risk facilities in Russia, China and regional states with an estimated 384 nuclear warheads on 96 Trident II D5 missiles that can be launched within “a few minutes” after receiving the launch order. The targets in the “target packages” are selected based on the taskings of the strategic war plan, known today as Operations Plan (OPLAN) 8010.

What is the Mission?

But why, nearly two decades after the Cold War ended, are 28 crews ordered to sail 14 SSBNs with more than 1,000 nuclear warheads on 30-plus patrols each year at an operational tempo comparable to that of the Cold War?

The official line is, as stated last month by Secretary of the Navy Donald Winter during the celebration of the 1,000th Ohio-class deterrent patrol, that “the ability of our Trident fleet to [be ready to launch its missiles] 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year, has promoted the interests of peace and freedom around the world….Since the beginning of the nuclear age, the world has seen a drastic reduction in wartime deaths.”

|

Figure 6: |

|

|

STRATCOM commander General Kevin Chilton (left) and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Gary Roughead. General Chilton says SSBNs deter not only nuclear conflict but “conflict in general” and are “as equally important today, as they ever were during the height of the Cold War.” |

The warfighters add more nuances, including Commander Jeff Grimes of the Trident submarine USS Maryland (SSBN-738) who at the start of a recent deterrent patrol explained it to Navy Times: “There are nuclear weapons in the world today. Many nations have them. Proliferation is possible in the growing technologies societies have. The power of the deterrent is the knowledge that the capability exists in the hands of controlled people. So on a global scale, deterrence is showing how it’s working every day. We haven’t had a global, world war, in a long time,” he said. “Intelligence is different, the threats are different, so we do adjust the planning and contingencies for strategic operations continually to face the threats that may or may not be seen….We’re there on the front line, ready to go,” Grimes declared.

STRATCOM commander General Kevin Chilton, who in a war would advise the president on which nuclear strike options to use, said recently that although some people thought the Trident mission would end with the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, the SSBNs “are as equally important today, as they ever were during the height of the Cold War….The application of deterrence can actually be more complicated in the 21st century, but some fundamentals don’t change,” he said and added: “And it is not just to deter nuclear conflict. These forces have served to deter conflict in general, writ large, since they’ve been fielded.”

These are strong and diverse claims that are also made in some of the command histories that each SSBN produces. Some of them state that the mission is to “maintain world peace,” which has certainly not been the case in the post-Cold War era. Others describe the mission as “providing strategic deterrence to prevent nuclear war” (my emphasis), which sounds more credible. But even in that case, can we really tell whether it is the SSBNs that prevent nuclear war and not the ICBMs or bombers?

The enormous differences between maintaining world peace, preventing wars, and preventing nuclear war demand that officials articulate the SSBN mission much more clearly. To that end, it would be good to hear why it takes 12 operational SSBNs with more than 1,100 nuclear warheads on 30-plus patrols per year to deter nuclear attack against the United States, but only three operational SSBNs with less than 160 warheads on six patrols per year to safeguard the United Kingdom.

|

Figure 7: |

|

| USS Maryland (SSBN-738) departs Kings Bay on February 15, 2009, for its 53rd deterrent patrol in the Atlantic Ocean to prevent nuclear war, prevent world war, deter conflict, maintain world peace, promote the interests of peace of freedom, deter proliferators, in a mission that remains“equally important…as during the height of the Cold War,” depending on who is describing it. |

.

Last year Russia’s SSBNs returned to sea at a level not seen in a decade and it plans to build eight new Borey-class SSBNs with new multi-warhead missiles. France is completing its fourth Triomphant-class SSBNs also with a new multi-warhead missile, and Britain has announced plans to build four new SSBNs. China is building 3-5 new Jin-class SSBNs with 8000-kilometer missiles, and India is said to be working on an SSBN as well. The U.S. Navy has also begun design work on its next ballistic missile submarine to replace the Ohio-class.

In short, the nuclear powers seem to be recommitting themselves to an era of deploying large numbers of nuclear weapons in the oceans. Most people tend to view sea-based nuclear weapons as the most legitimate leg of the Triad. Yet of all strategic nuclear weapons, sea-based ballistic missiles are the most difficult to track, the most problematic to communicate with in a crisis, the hardest to verify in an arms control agreement, and the only ones that can sneak up on an adversary in a surprise attack.

If the Obama administration wants to decisively move the world toward “dramatic reductions” and ultimately the elimination of nuclear weapons, then it must seek answers to these issues. In the short term, it needs to ask whether the Cold War operational tempo of U.S. SSBNs is counterproductive by sending a signal to other nuclear weapon states that triggers modernization of their forces and makes reductions harder to achieve than otherwise. In other words, what is the net impact of the SSBN patrols on U.S. national security objectives in an era of pursuing nuclear disarmament?

Addition Resources: Russian Sub Patrols | Chinese Sub Patrols

_____________________________________________________________

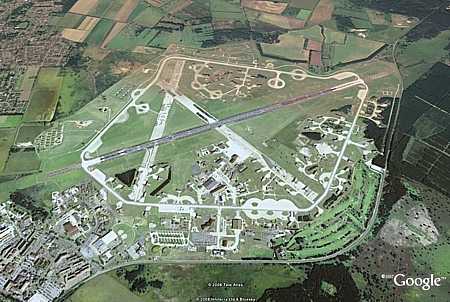

U.S. Nuclear Weapons Withdrawn From the United Kingdom

More than 100 U.S. nuclear bombs have been withdrawn from RAF Lakenheath, the forward base of the U.S. Air Force 48th Fighter Wing. Image: GoogleEarth

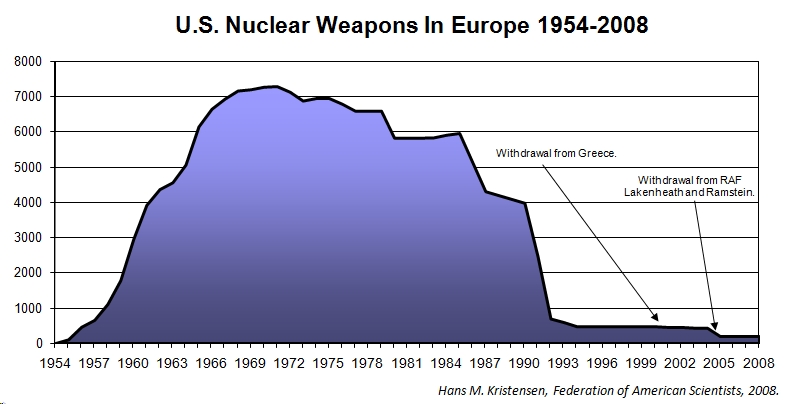

The United States has withdrawn nuclear weapons from the RAF Lakenheath air base 70 miles northeast of London, marking the end to more than 50 years of U.S. nuclear weapons deployment to the United Kingdom since the first nuclear bombs first arrived in September 1954.

The withdrawal, which has not been officially announced but confirmed by several sources, follows the withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base in Germany in 2005 and Greece in 2001. The removal of nuclear weapons from three bases in two NATO countries in less than a decade undercuts the argument for continuing deployment in other European countries.

Status of European Deployment

I have previously described that President Bill Clinton in November 2000 authorized the Pentagon to deploy 110 nuclear bombs at Lakenheath, part of a total of 480 nuclear bombs authorized for Europe at the time.

US Nuclear Weapons in Europe 2008

President George Bush updated the authorization in May 2004, which apparently ordered the withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base in Germany. The withdrawal from Lakenheath might also have been authorized by the Bush directive, or by an update issued within the past three years. This reduction and consolidation in Europe was hinted by General James Jones, the NATO Supreme Commander at Europe at the time, when he stated in a testimony to a Belgian Senate committee: “The reduction will be significant. Good news is on the way.”

Last week I reported that security deficiencies found by the U.S. Air Force Blue Ribbon Review at “most” sites were likely to lead to further consolidation of the weapons, and that “significant changes” were rumored at Lakenheath.

Withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from three European bases since 2001 means that two-thirds of the arsenal is now on the southern flank.

The withdrawal from Lakenheath means that the U.S. nuclear weapons deployment overseas is down to only two U.S. Air Force bases (Aviano AB in Italy and Incirlik in Turkey) plus four other national European bases in Belgium, Germany, Holland and Italy, for a total of six bases in Europe. It is estimated that there are 150-240 B61 nuclear bombs left in Europe, two-thirds of which are based on NATO’s southern flank (see Table 1).

Some Implications

Why NATO and the United States have decided to keep these major withdrawals secret is a big puzzle. The explanation might simply be that “nuclear” always means secret, that it was done to prevent a public debate about the future of the rest of the weapons, or that the Bush administration just doesn’t like arms control. Whatever the reason, it is troubling because the reductions have occurred around the same time that Russian officials repeatedly have pointed to the U.S. weapons in Europe as a justification to reject limitations on Russia’s own tactical nuclear weapons.

In fact, at the very same time that preparations for the withdrawal from Ramstein and Lakenheath were underway, a U.S. State Department delegation visiting Moscow clashed with Russian officials about who had done enough to reduce its non-strategic nuclear weapons. General Jones’ “good news” could not be shared.

While NATO boasts about its nuclear reductions since the Cold War, the Alliance is more timid about the reductions in recent years.

By keeping the withdrawals secret, NATO and the United States have missed huge opportunities to engage Russia directly and positively about reductions to their non-strategic nuclear weapons, and to improve their own nuclear image in the world in general.

The news about the withdrawal from Lakenheath comes at an inconvenient time for those who advocate continuing deployment of U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe. By following on the heels of the withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base in 2004-2005 and Greece in 2001, the Lakenheath withdrawal raises the obvious question at the remaining nuclear sites: If they can withdraw, why can’t we?

What is at stake is not whether NATO should be protected with nuclear weapons, but why it is still necessary to deploy tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. Japan and South Korea are also covered by the U.S. nuclear umbrella, but without tactical nuclear weapons deployed in Asia. The benefits from withdrawing the remaining non-strategic nuclear weapons from Europe far outweigh the costs, risks and political objectives of keeping them there. The only question is: who will make the first move?

Previous reports: USAF Report: “Most” Nuclear Sites in Europe do not Meet US Security Requirements (FAS, June 2008) | United States Removes Nuclear Weapons from German Base, Documents Indicate (FAS, July 2007) | U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe (NRDC, 2005)

Nuclear Arms Racing in the Post-Cold War Era: Who is the Smallest?

|

|

China and the Uniked Kingdom have started a new arms race over who has the smallest nuclear weapons arsenal. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

Mine is smaller! No, mine is smaller!!

China and the United Kingdom have started a new type of nuclear arms race for the honor to have the smallest number of nuclear weapons.

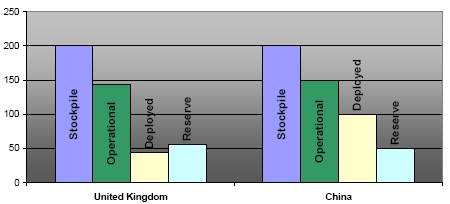

In April 2004, the Chinese Foreign Ministry declared in the fact sheet China: Nuclear Disarmament and Reduction of: “Among the nuclear-weapon states, China…possesses the smallest nuclear arsenal.”

In May 2007, British Defense Minister Des Browne stated in a written response to a parliamentary question that the United Kingdom has “the smallest stockpile of any of the nuclear weapon states recognised under the NPT.”

Apparently, the race is on for who is the smallest.

So Who Is The Smallest Nuclear Power?

The size of the nuclear weapons inventory of both countries is secret, but it is possible to make best estimates.

Britain announced in December 2006 that it had reduced the number of “operationally available warheads” from fewer than 200 to “less than 160.” The gesture was somewhat hollow, however, because Britain hasn’t had room for more than 144 warheads on its Trident D5 missiles for years. Moreover, the language hints that Britain has more nuclear warheads in storage. Assuming it retains a small reserve, the total British stockpile is probably around 200 warheads.

The British government has stated that the single SSBN on patrol at any given time carries “up to 48” warheads, a statement that partly reflects that some of the missiles have been given a “substrategic” mission, probably with only one warhead each. Depending on the number of substrategic mission missiles carried, the actual loading of the patrolling submarine probably is 36-44 warheads. Assuming a similar loading for the other two SSBNs for which there are missiles available, the estimated number of warheads needed for the British SSBN fleet since the substrategic mission first became operational in 1996 is 108-132 warheads.

The Chinese government’s statement that it possesses the smallest nuclear arsenal among the nuclear-weapon states is different than the British statement. First, the Chinese statement refers to the “arsenal” rather than stockpile described by the British statement. It is unclear what the Chinese mean by “arsenal” – whether it refers to the entire stockpile or only operational warheads. Second, the statement refers to “the nuclear-weapon states,” rather than the NPT-declared nuclear weapon states (Britain, China, France, Russia, United States), and thus appears to include India and Pakistan as well. Yet elsewhere in the statement, the foreign minister uses the term “nuclear-weapon states” to refer to Britain, China, France, Russia, and the United States. Based on publicly available information and assessments made by the U.S. Intelligence Community, China is estimated to have approximately 150 operational nuclear weapons and a total stockpile of roughly 200 warheads. Only about 100 of these may actually be deployed with the delivery systems, although few (if any) of the warheads are thought to be mated on the weapon.

|

|

|

|

Britain and China both claim to have the lowest number of nuclear weapons of the original five nuclear weapon states. Both refuse to say how many they have. In reality, the two countries are estimated to have about the same total number of nuclear warheads, but the numbers can very considerably depending on which part of the posture is presented. |

The two postures differ significantly. China does not have a permanent deployment of nuclear weapons at sea, and most (if not all) of China’s land-based missiles are thought to be deployed without the nuclear warheads installed. Unlike Britain, moreover, China has a no-first-use policy for its nuclear weapons.

In the future, however, China may have to revisit its statement about its nuclear weapons inventory. Whereas the British stockpile has declined an is unlikely to increase in the future, the Chinese stockpile may be increasing some in the next decade.

Confidence Reaffirmed (Silly Secrecy Too)

The statements made by the two countries have revealed a curious phenomenon: both apparently are confident that they know how many nuclear weapons the other has. Indeed, confidence appears to be so high that both are willing to say so in public.

This is curious because both countries insist that the size of their nuclear stockpiles must be kept a secret, or national security would be jeopardized. But if they both know the size of the other’s arsenal, who are they keeping it secret from?

Background: Britain’s Next Nuclear Era | Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning | British Nuclear Forces, 2005

Update on UK Foot and Mouth Disease Outbreak

Most Strategic Security Blog readers are probably already aware of the recent outbreak of Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) in the UK, but I thought it might be useful to post summary information on what we know to date. In short, it appears as if the virus was found on two farms, that the likely source of the virus was a research and vaccine production facility located nearby, and that there will be hell to pay if it is determined that someone at that facility is responsible for the outbreak and subsequent shut down of beef exports from the UK. The good news is that the response to this outbreak was vastly improved from a 2001 outbreak, which resulted in close to 7 million animals being destroyed. The bad news is that it was probably released from a laboratory and will no doubt spark new concerns about animal disease research.

Details:

An out break of FMD was confirmed on August 3rd on a farm in Surrey, according to the British Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). A second case was found at a nearby farm, but tests at two other farms were negative. The owner of the Woolford Farm, where the first disease outbreak was found, reported symptoms to his veterinarian and then DEFRA on the 2nd. DEFRA said in a statement that the strain is a 01 BFS67-like virus, isolated in the 1967 FMD outbreak in the UK. That strain was being used this past July for vaccine production at a nearby facility run by Merial Animal Health, which is jointly owned by Merck and French pharmaceutical company Sanofi-Aventis.

Small Fuze – Big Effect

“It is not true,” British Defence Secretary Des Browne insisted during an interview with BBC radio, that a new fuze planned for British nuclear warheads and reported by the Guardian will increase their military capability. The plan to replace the fuze “was reported to the [Parliament’s] Select Committee in 2005 and is not an upgrading of the system; it is merely making sure that the system works to its maximum efficiency,” Mr. Browne says.

The minister is either being ignorant or economical with the truth. According to numerous statements made by US officials over the past decade, the very purpose of replacing the fuze is – in stark contrast to Mr. Browne’s assurance – to give the weapon improved military capabilities it did not have before.

The matter, which is controversial now because Britain is debating whether to build a new generation of nuclear-armed submarines, concerns the Mk4 reentry vehicle on Trident D5 missiles deployed on British (and US) ballistic missile submarines. The cone-shaped Mk4 contains the nuclear explosive package itself and is designed to protect it from the fierce heat created during reentry of the Earth’s atmosphere toward the target. A small fuze at the tip of the Mk4 measures the altitude and detonates the explosive package at the right “height of burst” to create the maximum pressure to ensure destruction of the target. The new fuze will increase the “maximum efficiency” significantly and give the British Trident submarines hard target kill capability for the first time.

US Statements About Enhanced Capability

Unlike the British government, US officials and agencies have been very clear that the new fuze is not merely a replacement but a significant upgrade that will give the Mk4 significant military capabilities. The Department of Energy’s Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan from 1997 stated that the whole purpose of developing a new fuze in the first place was to “enable [the] W76 to take advantage of [the] higher accuracy of the D5 missile.”

At about the same time, the head of the US Navy’s Strategic Systems Command, Rear Admiral George P. Nanos, explained in The Submarine Review that the “capability for the [existing] Mk4…is not very impressive by today’s standards, largely because the Mk4 was never given a fuze that made it capable of placing the burst at the right height to hold other than urban industrial targets at risk.” But “with the accuracy of D5 and Mk4, just by changing the fuse in the Mk4 re-entry body, you get a significant improvement,” Admiral Nanos stated. In fact, “the Mk4, with a modified fuze and Trident II accuracy, can meet the original D5 hard target requirement.”

| Trident Mk4A Reentry Vehicle |

|

| The US Navy is saying – and the British government is denying – that a new fuze for the Mk4 reentry vehicle will increase the capability against hard targets. |

For US war planners, this improvement was necessary because the main US hard target killer, the MX Peacekeeper ICBMs with high-yield W87 warheads, were being retired as a result of the never-ratified 1992 START II treaty and the 2002 Moscow Treaty (SORT). The last Peacekeeper stood down in 2005. Some of the W87 are now being backfitted unto the Minuteman III ICBMs with a new guidance system to retain ICBM hard target kill capability. The Navy has a dedicated hard target kill W88 warhead on some of its D5 missiles, but with the new fuze on the W76-1/Mk4A the hard target kill capability will increase significantly. The first W76-1/Mk4A is scheduled to be delivered in September 2007.

Implications for British Deterrence

Admiral Nanos’ statement implies that British Trident submarines have never had hard target kill capability “because the Mk4 was never given a fuze that made it capable of placing the burst at the right height to hold other than urban industrial targets at risk.” With the new fuze, however, the British Trident submarines “can meet the original D5 hard target requirement,” and hold at risk the full range of targets.

So why does the British upgrade come now? After all, British nuclear submarines have cruised the oceans for decades with less capable fuzes and still ensured, so it has been said, Britain’s survival and made “significant contributions” to NATO’s deterrence.

There are several possibilities. British nuclear planners may have successfully argued that they need more accurate nuclear weapons to better deter potential adversaries. That is the dynamic the created in the Trident system during the Cold War. Since then, Britain has moved from a Soviet-focused deterrent to a “Goldilocks doctrine” today aimed against three incremental sizes of adversaries: Russia, “rogue” states, and terrorists.

Another possibility is that it may be a result of Britain not having an independent deterrent. Rather than designing and building its nuclear missiles itself, British leases them from the US missile inventory. The warhead installed on the “British” missiles is believed to be a modified – but very similar – version of the American W76. But the reentry vehicle that contains the explosive package appears to be the same: the Mk4. And since the US is upgrading its Mk4 to the Mk4A with the new fuze, Britain may simply have gotten the new capability with its existing lease.

Whatever the reason, the British government’s denial is clearly flawed. If the government believes so strongly that a nuclear deterrent is still necessary, why be so timid about its new capability? After all, what is the new capability good for if the potential adversaries can’t be told about it? And if the British government believes in the nuclear deterrent, then it has to play the deterrence role and be honest about it, and not – as it does now – pretend to be a nuclear disarmer while secretly enhancing its nuclear weapons capabilities.

No Need to Replace UK Nuclear Subs Now, FAS Board Member Tells Brits

(Updated January 26, 2007)

(Updated January 26, 2007)

British Vanguard-class ballistic missile submarines have at least 15 years more service life in them, and the U.K. government does not have to make a decision now on whether to replace them with a new class of submarines, Richard Garwin told BBC radio Tuesday.

Garwin, who is a member of the Federation of American Scientists Board of Directors and a long-term adviser to the U.S. government on defense matters, is in Britain to testify before the House of Commons Defence Select Committee on the future of Britain’s nuclear deterrent.

The U.K. government announced on December 4, 2006, that it had decided to replace its current Vanguard-class sea-launched ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) with a new class to enter operation in 2024. If approved by the parliament, the plan would extend Britain’s nuclear era into the 2050s.

According to the U.K. government, a decision to build a new new class must be made now because the Vanguard-class SSBNs only have a have a design life of 25 years. But Garwin says that the submarines have a minimum design life of 25 years, which can be extended by at least another 15 years. A decision made now is premature and unwise, Garwin told BBC, because the large Trident missiles may not be necessary 15 years from now.

New additions: Garwin testimony / House of Lords debate

Background: BBC Today | Garwin Archive at FAS | Britain’s Next Nuclear Era