The 2024 DOD China Military Power Report

The Department of Defense has finally released the 2024 version of the China Military Power Report. We will provide additional analysis of the Chinese arsenal in early 2025 but offer these observations for now:

The report estimates that China, as of mid-2024, had more than 600 nuclear warheads in its stockpile, an increase of roughly 100 warheads compared with the estimate for 2023 and about 400 warheads since 2019. As we have stated for several years, this increase is unprecedented for China and contradicts China’s obligations under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. DOD assesses that the Chinese nuclear buildup “almost certainly is due to the PRC’s broader and longer-term perceptions of progressively increased U.S.-PRC strategic competition.”

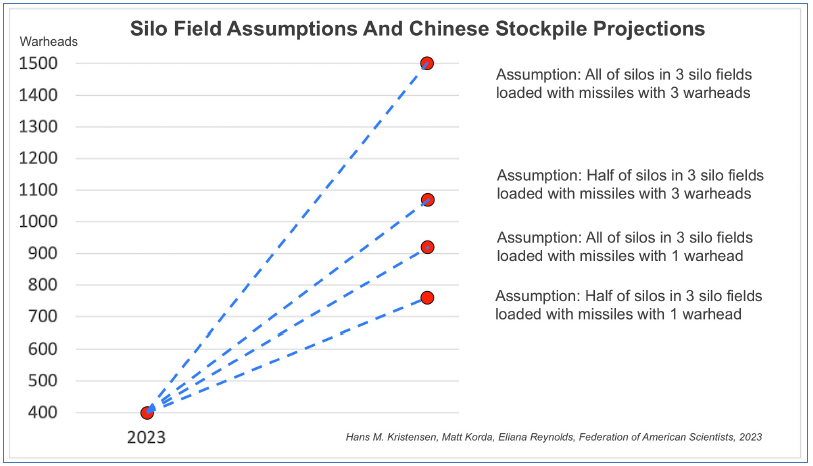

The breakdown of the DOD estimate comes with considerable uncertainty. It appears to assume that sufficient warheads have been produced to arm many – perhaps up to one third – of the silos in the three new ICBM silo fields in northern China. Different assumptions about how those silos will be armed greatly influence warhead projections:

Different assumptions about how China will arm it’s missile silos can significantly influence warhead number projections.

Matching the warhead estimate with the known force structure also depends on how many of the new liquid-fuel silos under construction in the mountains of central/southeastern China are operational, and how many of missiles carry multiple warheads. Other variables are how many warheads are assigned to the DF-26 IRBM launchers (probably not all of them), how many of the six SSBNs have been upgraded to the JL-3 SLBM and whether it is assigned multiple warheads, and how many DF-41 ICBM launchers are operational and how many warheads each missile is assigned.

As in previously years, the DOD report misleadingly describes the Chinese warheads as “operational.” This gives the false impression that they’re all deployed like Russia and U.S. nuclear warheads on their operational forces and has already created confusion in the public debate by causing some to compare all Chinese warheads with the portion of US warheads that are deployed. What DOD calls China’s “operational” warheads is equivalent to DOD’s entire nuclear warhead stockpile, whether deployed, operational, or reserve.

Except for perhaps a small number, the vast majority of Chinese warheads are thought to be in storage and not deployed on the launchers. This situation may be changing with a higher readiness level and emerging launch-on-warning capability.

The report repeats earlier projections that China might have over 1,000 warheads by 2030 but does not mention previous projections of 1,500 warheads by 2035. But this expansion requires additional plutonium production. The report confirms that China “has not produced large quantities of plutonium for its weapons program since the early 1990s” and anticipates that it “probably will need to begin producing new plutonium this decade to meet the needs of its expanding nuclear stockpile.”

ICBMs

The report lists 550 ICBM (Intercontinental-Range Ballistic Missile) launchers with 400 ICBMs, an increase of 50 launcher and 50 missiles compared with last year’s report. That is more ICBM launchers than the United States has, although far from all the Chinese silos are armed.

It is unclear what operational status a missile must have to be included in the count or whether 400 is simply the total number of missile available for the launchers. If it means operational (which I don’t think is the case), then 400 ICBMs would imply a significant number of the new silos loaded.

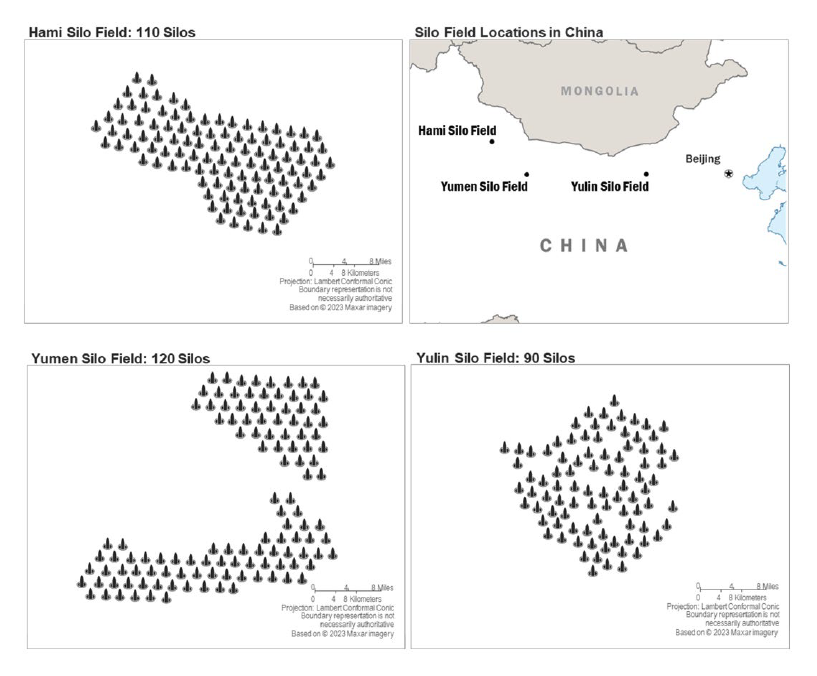

The report includes a map that appears to match previous FAS analysis of the three silo fields:

The DOD map of the three northern silo fields appears to match earlier FAS analysis.

The report states that the three ICBM fields were probably completed in 2022 and that PLARF has loaded “at least some” ICBMs into the silos. The report says China “probably continues to arm” the silo fields.

For now, the new silo fields appear intended for the solid-fuel DF-31A. The DOD report identifies a new version of the DF-31 (CSS-10 Mod 3), which is probably the version intended for the silos.

The ICBM estimate appears to come with several caveats. One is that the number of ICBM launchers is not the same as the number of operational ICBMs. A silo launcher appears to be counted when construction is completed, whether it is operational with missile or not. To get to 550 launchers, it is necessary to count everything, including all the 320 silos in the three new northern silo fields as well as all the silos under construction in the southeastern mountains.

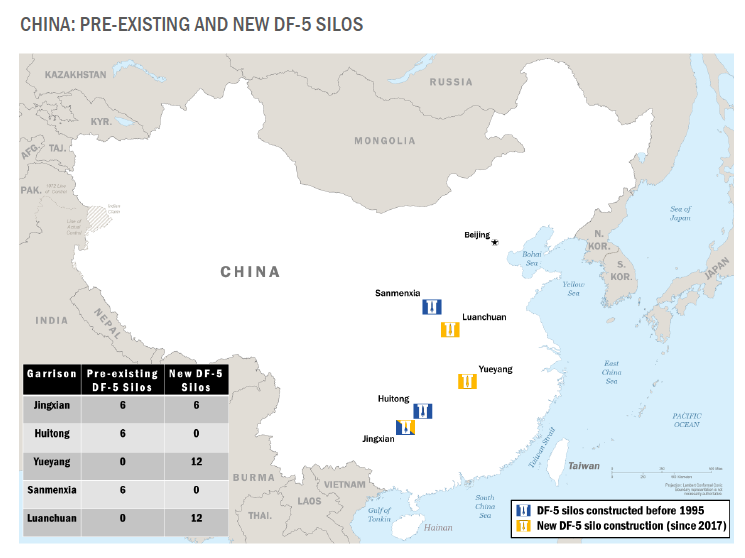

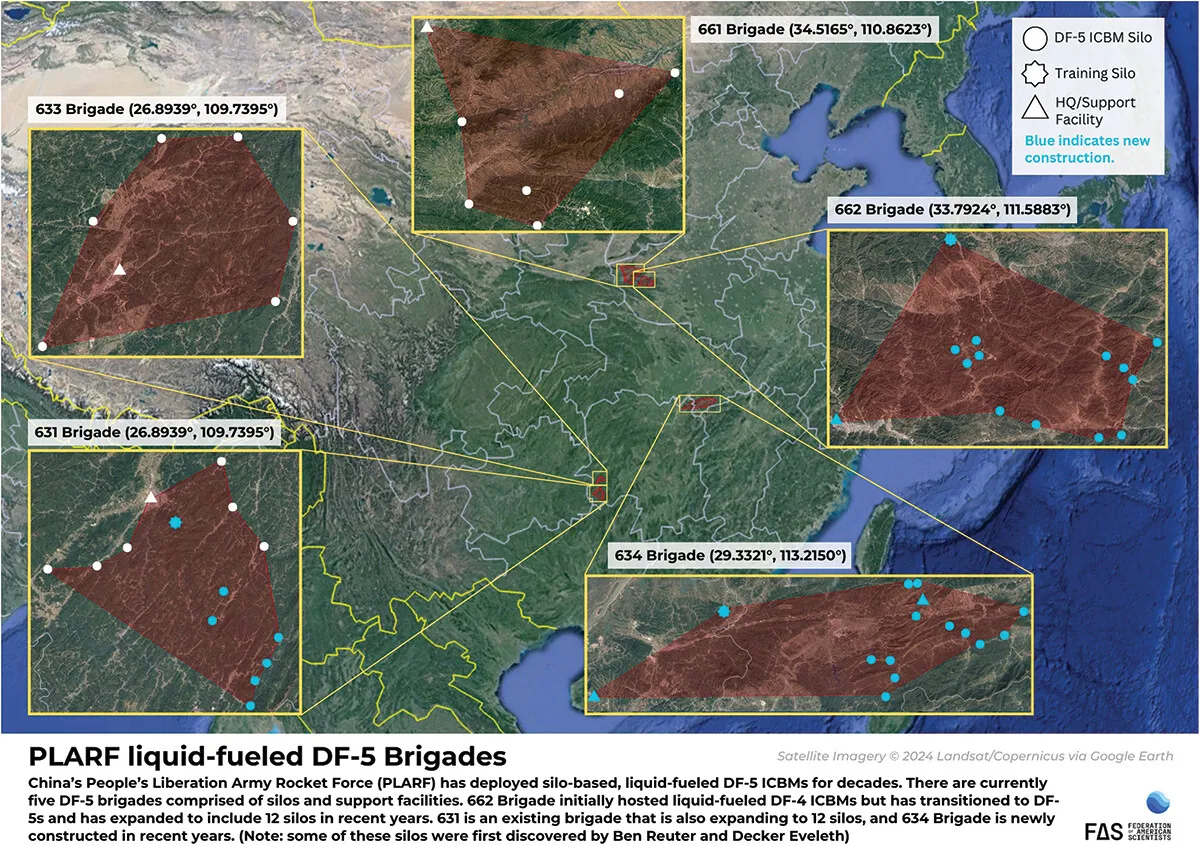

The report says the silo construction in the central/southeastern part of China will probably result in about 50 silos there, matching estimates made by FAS and others. The report confirms that those new silos are intended for DF-5 liquid-fuel missiles and appears to suggest that at least two brigades with the new silos are intended for the new multi-megaton DF-5C that it says China is now fielding.

The 2024 China Military Power Report confirms reports by FAS, Ben Reuter, and Decker Eveleth about the modernization of the DF-5 silos in central/southeastern China.

The report does not say how many of the new DF-5 silos – if any – have been loaded with missiles.

The new DF-41 ICBM is not said to be deployed in silos but so far only as a road-mobile system in a few brigades. But the DOD report says China might pursue silo and rail deployments for the missile in the future.

The new DF-27 is described as dual-capable and while capable of shorter ICBM ranges mainly be intended for conventional IRBM missions.

IRBMs and MRBMs

The report lists 250 IRBM (Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missile) launchers with 500 missiles, the same as in 2023. This force apparently consists entirely of the DF-26, of which the report identifies three versions. Previously an anti-ship version was identified in addition to the basic version, so it is unclear if the first two versions are used to differentiate between the conventional and nuclear versions. Regardless, the DF-26 is replacing the DF-21 MRBM (Medium-Range Ballistic Missile) and the report says there are no longer any brigades with “dual nuclear-conventional capable DF-21Cs” (which is odd because the C was the conventional and the A was the nuclear).

The DF-17 MRBM maneuverable glide vehicle is described as conventional.

SSBNs

The report says that China continues to operate six Jin-class Type 094 SSBNs (nuclear powered ballistic missiles submarines) equipped with either the JL-2 or the 10,000-km range JL-3 SLBM (Sea-Launched Ballistic Missile). Despite the longer range of the JL-3 SLBM, it is not capable of targeting the Continental United States from the South China Sea. A submarine would have to deploy up into the shallow Bohai Sea to be able to target part of CONUS.

The DOD report says the six SSBNs “are conducting at sea deterrent patrols.” In the U.S. Navy, that means the missiles are armed with nuclear warheads, but the DOD report does not explicitly say this is the case for China.

The report says the SSBNs are “representing the PRC’s first viable sea-based nuclear deterrent,” and says China “has the capacity to maintain a constant at sea deterrent presence.” More Jin-class SSBNs apparently are under construction.

The next-generation Type 096 apparently is not yet under construction. It is said it will get a new longer-range missile, although it is unclear if that is older language that used to refer to the JL-3. The report says the Type 096 SSBN “probably is intended to field MIRVed SLBMs,” indicating that the SLBMs on the current Jin-class are not.

Bombers

The report repeats previous statements that China is fielding a nuclear version of the H-6 medium-range bomber. The nuclear version H-6N is capable of carrying a large air-launched ballistic missile that “may be” nuclear capable. Although China is often said to have a Triad, the air-leg is nascent and still only includes one brigade that is developing tactics and procedures for the PLAAF nuclear mission.

As mentioned above, we will provide additional analysis of the DOD report and Chinese nuclear forces early in the new year. More information: The Nuclear Information Project

The Federation of American Scientists’ work on nuclear transparency would not be possible without generous support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Longview Philanthropy, the Jubitz Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

A Decade After Signing, New START Treaty Is Working

On this day, ten years ago, U.S. President Barack Obama and Russian President Dmitri A. Medvedev signed the New START treaty during a ceremony in Prague. The treaty capped the number of strategic missiles and heavy bombers the two countries could possess to 800, with no more than 700 launchers and 1,550 warheads deployed. The treaty entered into force in February 2011 and into effect in February 2018.

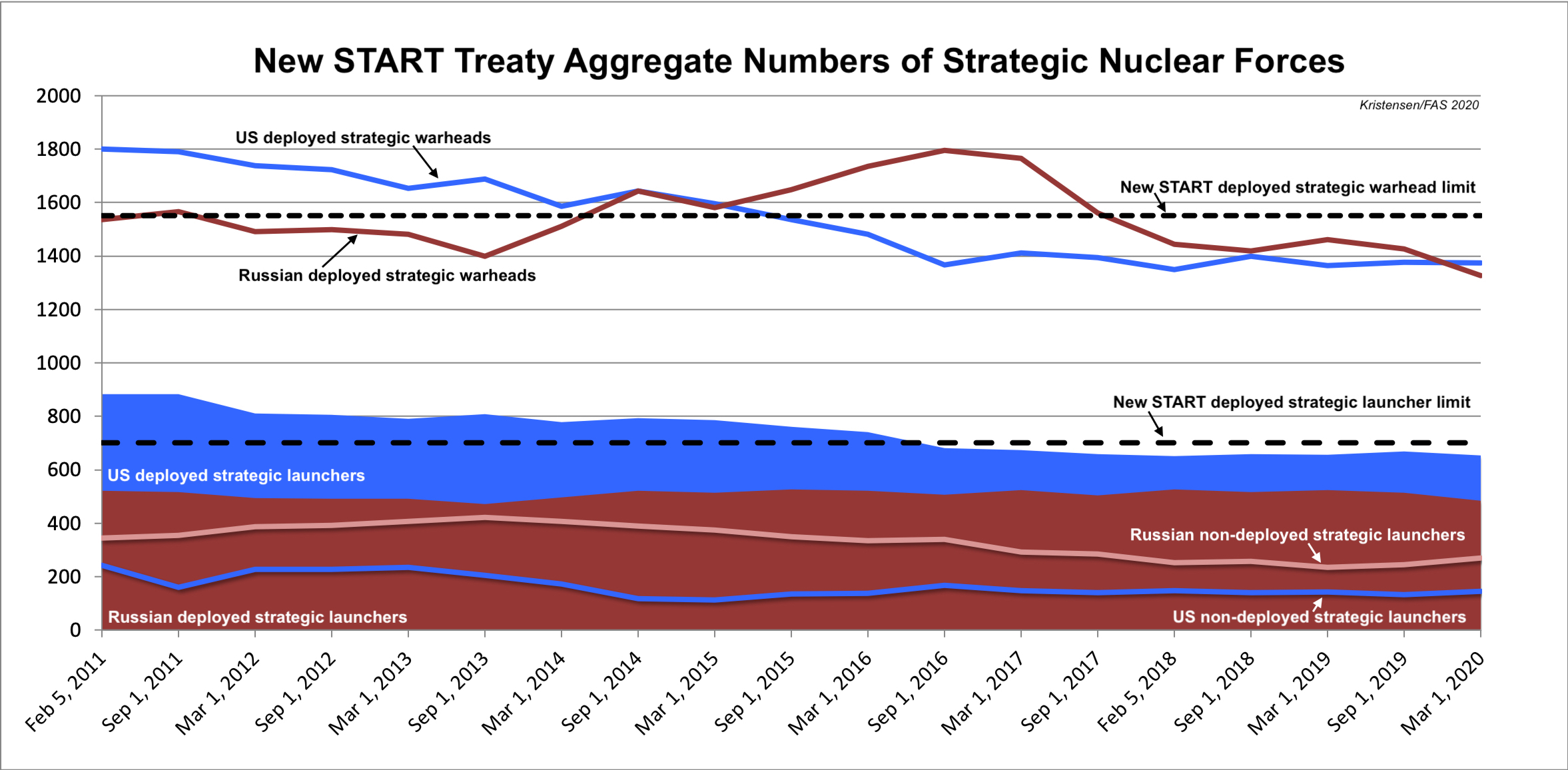

Twice a year, the two countries have exchanged detailed data on their strategic forces. Of that data, the public gets to see three sets of numbers: the so-called aggregate data of deployed launchers, warheads attributed to those launchers, and total launchers. Nine years of published data looks like this:

The latest set of this data was released by the U.S. State Department last week and shows the situation as of March 1, 2020. As of that date, the two countries possessed a combined total of 1,554 strategic missiles and heavy bombers, of which

1,140 launchers were deployed with 2,699 warheads (note: the warhead number is actually about 100 too high because each deployed bomber is counted as one weapon even though bombers don’t carry weapons under normal circumstances).

Compared with September 2019, the data shows the two countries combined cut 3 strategic launchers, reduced deployed strategic launchers by 41, and reduced the number of deployed strategic warheads by 103. Of these numbers, only the “3” is real; the other changes reflect natural fluctuations as launchers move in and out of maintenance or are being upgraded.

Compared with February 2011, the data shows the two countries combined have cut 435 strategic launchers, reduced deployed strategic launchers by 263, and reduced the number of deployed strategic warheads by 638. While important, it’s important to remind that this warhead reduction is but a fraction (less than 8 percent) of the estimated 8,110 warheads that remain in the two countries combined nuclear weapons stockpiles (less than 6 percent if counting their total combined inventories of 12,170 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The United States

The data shows the United States currently possessing 800 strategic launchers, of which 655 are deployed with 1,373 warheads attributed to them. This is a reduction of 13 deployed strategic launchers and 3 deployed strategic warheads over the past 6 months. These are not actual reductions but reflect normal fluctuations caused by launchers moving in and out of maintenance. The United States has not reduced its total inventory of strategic launchers since 2017.

Compared with February 2011, the United States has reduced its inventory of strategic launchers by 324, deployed launchers by 227, and deployed strategic warheads by 427. While important, the warhead reduction represents only a small fraction (about 11 percent) of the 3,800 warheads that remain in the U.S. stockpile (a little over 7 percent if counting total inventory of 5,800 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The Russian Federation

The New START data shows Russia with an inventory of 764 strategic launchers, of which 485 are deployed with 1,326 warheads attributed to them. Compared with six months ago, this is a reduction of 28 deployed launchers and 100 deployed strategic warheads and reflects launcher maintenance and upgrade work to new systems.

Compared with February 2011, Russia has cut its inventory of strategic launchers by 111, deployed launchers by 36, and deployed strategic warheads by 211. This modest reduction represents less than 5 percent of the estimated 4,310 warheads that remain in Russia’s nuclear weapons stockpile (less than 4 percent if counting the total inventory of 6,370 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) Russian warheads).

The Russian reductions accomplished under New START are smaller than the U.S. reductions because Russia had fewer strategic forces than the United States when the treaty entered into force in 2011.

Build-up, What Build-up?

With frequent claims by U.S. officials and nuclear weapons advocates that Russia is increasing its nuclear arsenal, it is interesting that despite a significant modernization program, the New START data shows this increase is not happening in the size of Russia’s strategic nuclear forces.

On the contrary, the New START data shows that Russia now has 170 deployed strategic launchers fewer than the United States, a number that exceeds the size of an entire US Air Force ICBM wing. The Russian launcher deficit has been growing by more than one-third since the lowest point of 125 in February 2018.

The Russian military is trying to compensate for this launcher disparity by increasing the number of warheads that can be carried on newer missiles replacing older types. Most of these warheads are not deployed on the missiles under normal circumstance but stored and could potentially be uploaded onto launchers in a crisis. The United States also has such an upload capability for its larger inventory of launchers and therefore is not at a strategic disadvantage.

Two of Russia’s new strategic nuclear weapons (Avangard and Sarmat) are covered by New START. Other types are in relatively small numbers and do not appear capable of upsetting the strategic balance. The treaty includes provisions for including new weapon types.

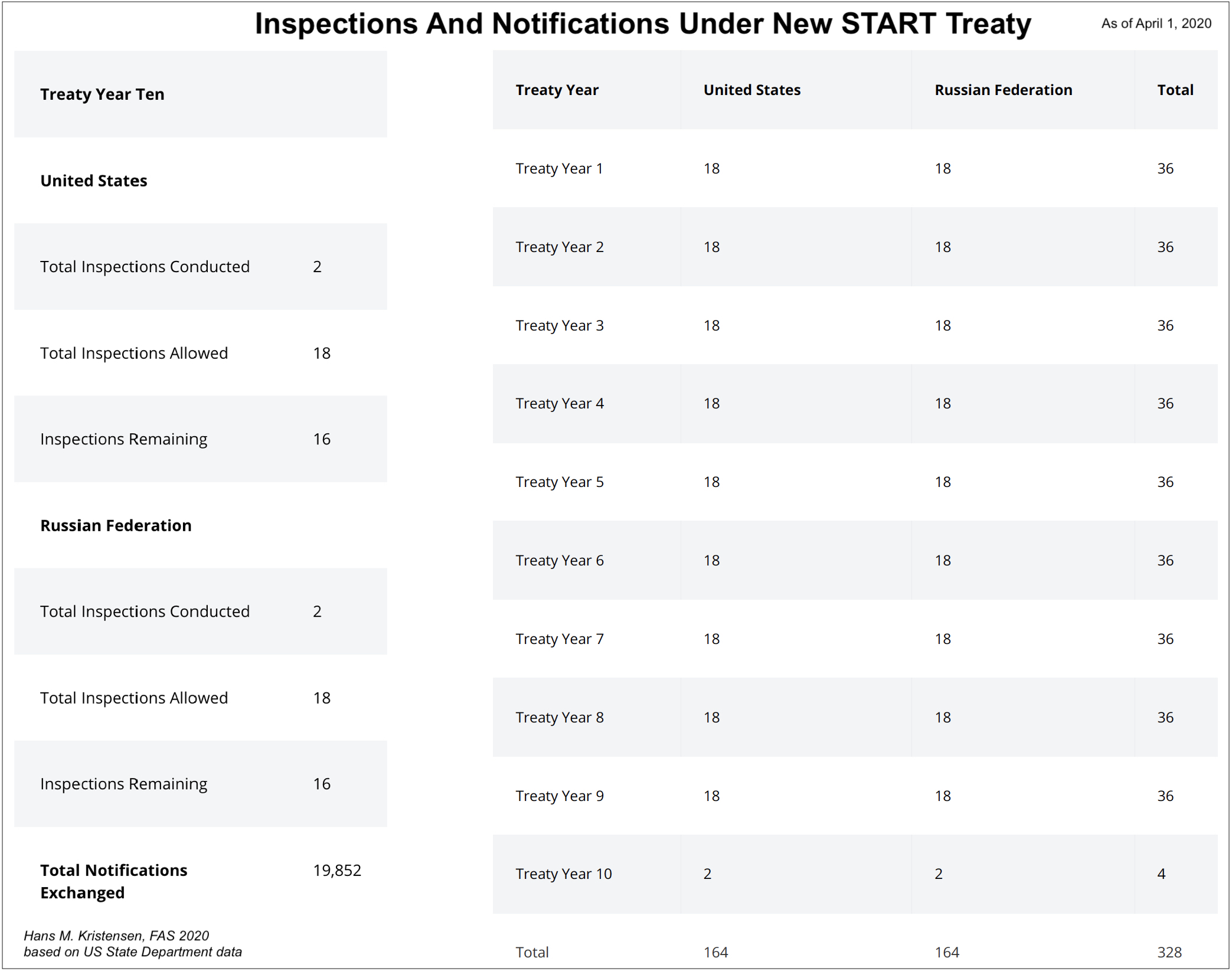

Inspections and Notifications

In addition to the New START data, the U.S. State Department also recently updated its overview of the status of the on-site inspections and notification exchanges that are part of the treaty’s verification regime.

Since February 2011, U.S. and Russian inspectors have carried out 328 on-site inspections of each other’s strategic nuclear forces and exchanged 19,852 notifications of launcher movements and activities. Four inspections happened this year before activities were temporarily halted due to the Coronavirus.

This inspection and notification regime and record are crucial parts of the treaty and increasingly important for U.S.-Russian strategic relations as other treaties and agreements have been scuttled.

But time is now also running out for New START with only a little over 10 months remaining before the treaty expires on February 5, 2021.

Russia and the United States can extend the New START treaty by up to 5 more years. It is essential both sides act responsibly and do so to preserve this essential agreement.

See also: Count-Down Begins For No-Brainer: Extend New START Treaty

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.