ISCAP Directs NSA to Release COMINT History

In 2005, the National Security Agency released a partially declassified (pdf) 1952 history of communications intelligence prior to Pearl Harbor with several passages censored. But this month, the NSA released the complete text (pdf) of the document after the Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel (ISCAP) determined that there was no justification for continued classification of the withheld portions.

During World War II, “Collaboration with the BRITISH COMINT organization got off to a bad start so far as the Navy was concerned…,” according to one newly declassified paragraph from the official history. “For several months U.S. Navy COMINT personnel thought they had been double-crossed by the British and were reluctant to go ahead with collaboration in direction finding and other matters which were greatly to England’s advantage throughout 1941.” Subsequent cooperation, however, proved “harmonious.” Now it can be told.

The NSA document was released in response to a mandatory declassification review request, followed by an appeal to ISCAP, submitted by researcher Michael Ravnitzky. See “A Brief History of Communications Intelligence in the United States” by Captain Lawrence Safford, USN, 21-27 March 1952.

The new disclosure illustrates once again the efficacy of the ISCAP in overcoming the reflexive secrecy of executive branch agencies, including those that are represented on the ISCAP itself. More often than not, the ISCAP has released information that one of its own member agencies said must remain classified.

Fundamentally, the ISCAP’s experience over the past decade or so demonstrates the importance of extending declassification authority beyond the original classifying agency. Left to their own devices, agencies will adhere to past classification practices indefinitely. But when such practices are critically examined by others, including others within the executive branch, they often wither before the scrutiny.

If there is a solution to “the problem of overclassification,” as requested by President Obama in a May 27, 2009 memorandum, it is bound to involve this kind of independent, external review of agency classification and declassification practices.

CRS on Innovation Inducements, Postal Closures

A new report from the Congressional Research Service examines the government’s use of “grand challenges” or monetary prizes to provide incentives for technological advancement. In quite a few cases, such incentives have inspired or accelerated new technology breakthroughs — in lightweight power supplies and autonomous unmanned vehicles, for example. In other cases, the proffered prizes have gone unclaimed because the challenge was not met, as in a recent competition to generate breathable oxygen from simulated lunar soil. In any case, it seems likely that the new CRS report is the best thing ever written on the subject. See “Federally Funded Innovation Inducement Prizes” (pdf), June 29, 2009.

Another new CRS report considers the mundane but significant fact that the US Postal Service may soon close thousands of post office branches and stations due to declining demand and volume. This exhaustive report, once again, is almost certainly the best, most informative treatment of its chosen subject. See “Post Office and Retail Postal Facility Closures: Overview and Issues for Congress” (pdf), July 23, 2009.

Despite the efforts of Sen. Joseph Lieberman, Sen. John McCain and a few others, there appears to be little near-term prospect that Congress will permit direct public access to CRS reports like these. Fortunately, routine unauthorized disclosures of the reports continue to meet the need fairly well.

See also, lately (all pdf):

“Issues Regarding a National Land Parcel Database,” July 22, 2009.

“Federal Research and Development Funding: FY2010,” July 15, 2009.

“The U.S. Newspaper Industry in Transition,” July 8, 2009.

“Agricultural Conservation Issues in the 111th Congress,” July 7, 2009.

Other News and Resources

Rep. Rush Holt (D-NJ) has suggested that the time may have come to undertake a comprehensive review of U.S. intelligence agency activities and operations on the scale of the 1976 Church Committee investigation. See “Holt Calls for Next Church Committee on CIA” by Spencer Ackerman, The Washington Independent, July 27, 2009.

The corrosive tendency of government agencies to classify historical information that is already in the public domain is made vividly clear in a collection of erroneously redacted documents compiled by William Burr of the National Security Archive. See “More Dubious Secrets: Systematic Overclassification of Defense Information Poses Challenge for President Obama’s Secrecy Review,” July 17, 2009.

A 2008 intelligence community policy memorandum on “Connection of United States and Commonwealth Secure Telephone Systems” (pdf) was released in almost entirely redacted form.

Some 700 classified images of Arctic sea ice have been declassified and released, the Department of Interior noted in a July 15 news release. “It reportedly is the largest release of [imagery] information derived from classified material since the declassification of CORONA satellite images during the Clinton Administration,” the DOI said. The release followed a National Research Council report that said the release of such classified imagery was needed to support climate change research. (See also coverage from Mother Jones and The Guardian.)

Persistent concerns over the government’s use of the state secrets privilege to curtail civil litigation were aired at a June 9, 2009 hearing before Rep. Jerrold Nadler’s House Judiciary Subcommittee. The record of that hearing, with abundant supporting materials submitted for the record, has just been published. See “State Secret Protection Act of 2009.”

Senate Bill Would Disclose Intel Budget Request

The Senate version of the FY2010 intelligence authorization bill (pdf) would require the President to disclose the aggregate amount requested for intelligence each year when the coming year’s budget request is submitted to Congress. Currently, only the total appropriation for the National Intelligence Program is disclosed — not the request — and not before the end of the fiscal year in question.

Disclosure of the budget request would enable Congress to appropriate a stand-alone intelligence budget that would no longer need to be concealed misleadingly in other non-intelligence budget accounts.

“This reform makes possible a recommendation of the 9/11 Commission to improve oversight by passing a separate intelligence appropriations bill and provides for greater transparency and accountability for intelligence spending,” said Sen. Russ Feingold, who sponsored the proposal, together with Committee Vice Chairman Sen. Christopher Bond and Sen. Ron Wyden. (Curiously, the measure was opposed by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse.) See Senate Report 111-55 (pdf) on the FY2010 Intelligence Authorization Act, Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, July 22 (sec. 356).

Intelligence budget disclosure has been and still remains a subject of extraordinary sensitivity to some officials. In 1999, DCI George J. Tenet specifically opposed the idea of releasing the annual budget request because he said it would damage national security by revealing intelligence strengths and defects.

“Disclosure of the budget request reasonably could be expected to provide foreign governments with the United States’ own assessment of its intelligence capabilities and weaknesses. The difference between the appropriation for one year and the Administration’s budget request for the next provides a measure of the Administration’s unique, critical assessment of its own intelligence programs,” Mr. Tenet argued in an April 6, 1999 affidavit filed in a FOIA lawsuit brought by the Federation of American Scientists.

This is surprisingly close to nonsense. Changes in aggregate spending levels occur for many reasons, including the start of new programs, the termination of completed programs, shifts in acquisition phases, personnel changes and inflation. The difference between the previous year’s expenditures and the following year’s request represents the outcome of thousands of individual programmatic decisions. Looking at last year’s NASA budget and this year’s NASA request, one could not possibly infer a meaningful assessment of the performance of the civilian space program. The same is true of the vastly more complicated intelligence bureaucracy.

But implausible as it seems, Mr. Tenet’s argument was sufficient to convince D.C. District Judge Thomas F. Hogan that disclosure would in fact threaten national security. And so the intelligence budget request has never been released.

Even now, the CIA takes great pains to conceal budget information that is more than half a century old, as if national security were somehow at stake. This week, the CIA published an historical document on its website concerning the “Central Intelligence Group Budget, Fiscal Year 1948” (pdf) with the ancient budget numbers meticulously removed.

Today, Bill Gertz of the Washington Times reported on a working draft of a new executive order on classification that he obtained. The principal feature of the new draft seems to be a National Declassification Center, designed to coordinate and expedite the declassification of historical records across the government. But it remains unclear if the proposed Center will include a mechanism for overturning erroneous classification policies like CIA’s indiscriminate budget secrecy. If it does not provide an error correction mechanism, then the Center might end up perversely reinforcing today’s retrograde classification policies and implementing them even more efficiently.

OSC Sees Signs of North Korean Succession

North Korea has renewed its planning for the likely succession of leadership from the ailing Kim Jong Il to his youngest son Kim Cho’ng-un (or Kim Jong Un), according to a deeply researched assessment by the DNI Open Source Center (OSC).

“Pyongyang last autumn reinvigorated a nuanced propaganda campaign that it apparently began eight years ago to prepare for the emergence of a hereditary successor to Kim Jong Il,” the OSC said. “The recent signals have been extremely subtle, suggesting that they are designed to inform internal audiences without alerting outsiders.”

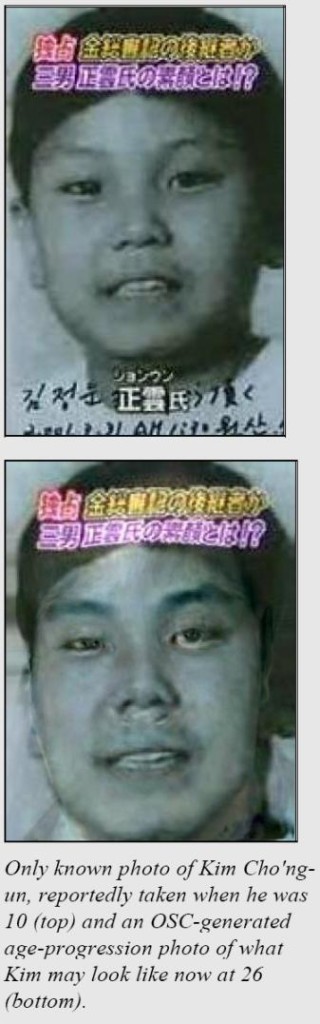

The OSC report (pdf) is a virtuoso piece of analysis that includes rich detail on the three generations of Kims, the development of the unfolding information campaign on leadership succession, and background on the little-known Kim Cho’ng-un. It even presents “an OSC-generated age-progression photo” that extrapolates from the only available photograph of the younger Kim, taken at age 10, to show what he may look like now at age 26. And it shows an amazing familiarity with obscure facets of North Korea’s notoriously secretive society.

The OSC report (pdf) is a virtuoso piece of analysis that includes rich detail on the three generations of Kims, the development of the unfolding information campaign on leadership succession, and background on the little-known Kim Cho’ng-un. It even presents “an OSC-generated age-progression photo” that extrapolates from the only available photograph of the younger Kim, taken at age 10, to show what he may look like now at age 26. And it shows an amazing familiarity with obscure facets of North Korea’s notoriously secretive society.

Thus, it finds a possibly significant allusion to Kim Cho’ng-un, who is his father’s third-born son, in the recent broadcast of “a children’s program entitled ‘Good Heart of the Third Child,’ which emphasized the moral virtue of the youngest of three brothers in his adherence to socialist principles.” This is something of a departure from the Confucian tradition which favors the eldest son, the OSC explains.

The OSC analysis, marked “for official use only,” has not been approved for public release, but a copy was obtained by Secrecy News. It was mentioned in “Who Will Succeed Kim Jong Il?” by Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, July 16, 2009. See “North Korean Media Campaign Suggests Long-Term Planning for Hereditary Successor,” Open Source Center, 6 May 2009.

For all of its detail and sophistication, the OSC assessment is inconclusive. A Russian analyst this week told Gazeta.ru that the anticipated selection of Kim Cho’ng-un is merely “conjecture and rumor” (Interview with Vasiliy Mikheyev, Gazeta.ru, July 21, 2009, translated by OSC). He recalled witnessing the ascension of Kim Jong Il to power in 1975 when Kim was publicly presented together with his father Kim Il Sung in joint portraits and official news stories. But “nothing of the sort is happening now… If only speculation is occurring, I think the successor has still not been chosen.”

Court Rebukes Government Over “Secret Law”

“Government must operate through public laws and regulations” and not through “secret law,” a federal appellate court declared in a decision last month. When our government attempts to do otherwise, the court said, it is emulating “totalitarian regimes.”

The new ruling (pdf) overturned the conviction of a defendant who had been found guilty of exporting rifle scopes in violation of the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR). The court said that the government had failed to properly identify which items are subject to export control regulations, or to justify the criteria for controlling them. It said the defendant could not be held responsible for violating such vague regulations.

Accepting the State Department’s claim of “authority to classify any item as a ‘defense article’ [thereby making it subject to export controls], without revealing the basis of the decision and without allowing any inquiry by the jury, would create serious constitutional problems,” wrote Chief Judge Frank H. Easterbrook of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals. “It would allow the sort of secret law that [the Supreme Court in] Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan, 293 U.S. 388 (1935), condemned.”

Normally, “A regulation is published for all to see,” explained Judge Easterbrook, a Reagan appointee who is considered a judicial conservative. “People can adjust their conduct to avoid liability. [In contrast,] a designation by an unnamed official, using unspecified criteria, that is put in a desk drawer, taken out only for use at a criminal trial, and immune from any evaluation by the judiciary, is the sort of tactic usually associated with totalitarian regimes,” he said. See the Court’s ruling in United States of America v. Doli Syarief Pulungan, June 15, 2009.

The new ruling “could be a very big deal in terms of export controls, and indeed in terms of ‘secret law’ in general,” said Gerald Epstein, a science and security policy scholar who served on a recent National Academy of Sciences panel on export control policy. “This case goes to the heart of the ambiguity of the International Traffic in Arms Regulations, which give the State Department great latitude in determining what is and what is not covered, and which are administered in a notoriously opaque way,” Dr. Epstein told Secrecy News.

Export control policy was addressed from various perspectives in an April 24, 2008 Senate hearing entitled “Beyond Control: Reforming Export Licensing Agencies for National Security and Economic Interests” (pdf) that was published last month.

Last year, Sen. Russ Feingold convened a hearing on the subject of “Secret Law and the Threat to Democratic and Accountable Government.” My prepared statement from that hearing on the diverse categories of secret law is available here (pdf).

State Dept Offers New Caveat on Nixon Tapes

The transcripts of Nixon White House tape recordings that are published in the State Department’s official Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) series are merely “interpretations,” not official records, the State Department acknowledged in the latest FRUS volume that was released this month. As such, those transcripts are susceptible to revision and correction.

“Readers are advised that the tape recording is the official document, while the transcript represents solely an interpretation of that document,” the new FRUS volume states in the Preface. The statement goes beyond previous FRUS references to poor tape quality. It is evidently a response to a simmering scholarly controversy over the accuracy of published FRUS transcriptions of the Nixon tapes, which appear to include clear errors.

Here are some examples of suspect “interpretations” from the Nixon FRUS Volume XIV (Soviet Union, October 1971-May 1972) that was published in December 2006 (with audio clips courtesy of nixontapes.org):

FRUS, as published (p.171): Kissinger: “On the other hand, you and I know that you were going to go for broke against the North.”

Probable Correction: Kissinger: “On the other hand, you and I know that you weren’t going to go for broke against the North.” (.mp3).

FRUS, as published (p.172): “What they do is they’re asking for, cuddling for, the things we are going to do anyway. Like troop withdrawal.”

Probable Correction: “What they do is they’re asking toughly for the things they know we’re going to do anyway, like troop withdrawals.” (.mp3)

FRUS, as published (p.743): Nixon: “You see, that’s the point [South Vietnamese President Nguyen] Thieu made which is tremendously compelling.”

Probable Correction: Nixon: “You see? That’s the point that you made which is tremendously compelling.” (.mp3)

FRUS, as published (p.746): Nixon: “And, you see, I’m going to lift the blockade as I’ve said. It’s not over yet–the bombing’s not over yet.”

Probable Correction: Nixon: “And, you see, that I’m going to live with the blockade as I’ve said. Well, it’s an ultimatum.” Kissinger: “Yeah.” Nixon: “Bombing is not an ultimatum.” (.mp3)

There is widespread agreement that it is not possible to produce a perfect transcript of the Nixon tapes. “Audio fidelity was never one of the design considerations of the original, surreptitious taping system,” said one former official. But by publishing the transcripts alongside other undisputed archival records, the FRUS series has appeared to boast a higher level of transcription accuracy than it has in fact provided.

“It is perfectly possible for two experienced auditors to transcribe two conflicting versions of the same conversation,” said Dr. William B. McAllister, the Acting General Editor of the FRUS series, though he admitted that only one of them could be correct. He said that the problem of interpreting official records was not altogether new and was also not limited to the Nixon tapes. The renowned Long Telegram that was sent by George Kennan in 1946 has some garbled text that has been interpreted in different ways. And with the growing importance for historians of audio, video, and even twitter records, “It’s only going to get more tricky.”

“Readers are urged to consult the recordings themselves for a full appreciation of those aspects of the conversations that cannot be captured in a transcript,” the FRUS volumes recommend, “such as the speakers’ inflections and emphases that may convey nuances of meaning, as well as the larger context of the discussion.”

A growing selection of Nixon audio tapes can be found online at www.nixontapes.org.

The interesting new FRUS volume on “American Republics,” which is the first FRUS publication in 2009, addresses U.S. policy towards Latin America and the Caribbean between 1969 and 1972, including covert action. The new volume, published online only, excludes materials on Bolivia, which the editors say have not yet been declassified, and it also omits records on Chile, which are to be published separately. The Preface states that documents on Uruguay are not being published “due to space constraints.” In fact, however, space is not at a premium in online “e-volumes,” and Secrecy News is told that the Uruguay compilation has not been declassified, which ought to have been noted.

JFK Urged Release of Most Diplomatic Records After 15 Years

The latest volume of the Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) series, the official record of U.S. foreign policy, reflects events that took place from 1969 to 1972, or nearly forty years ago. This represents a continuing violation of a 1991 statute which requires the Secretary of State to publish FRUS “not more than 30 years after the events recorded.” But even that seemingly unachievable goal is insufficiently ambitious, according to a 1961 directive issued by President John F. Kennedy.

“It has long been a point of pride of our government that we have made the historical record of our diplomacy available more promptly than any other nation in the world,” President Kennedy wrote.

“In recent years the publication of the ‘Foreign Relations’ series has fallen farther and farther behind currency,” he wrote back then. “The lag has now reached approximately twenty years. I regard this as unfortunate and undesirable. It is the policy of this Administration to unfold the historical record as fast and as fully as is consistent with national security and with friendly relations with foreign nations.”

“In my view, any official should have a clear and precise case involving the national interest before seeking to withhold from publication documents or papers fifteen or more years old,” President Kennedy concluded. See National Security Action Memorandum No. 91, “Expediting Publication of ‘Foreign Relations’,” September 6, 1961.

Barriers to Archival Access Stymie Historical Research

Notwithstanding official proclamations of a new era of transparency, public access to declassified historical records continues to be obstructed by procedural potholes, limited resources for processing records, competing priorities and, sometimes, bad faith.

At the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), declassified files that used to be open to the public have been withdrawn indefinitely so that they may reviewed for inadvertent releases of classified nuclear weapons-related information, pursuant to the 1999 “Kyl-Lott” Amendment. Nearly all Navy records there dating from the 1960s forward are now completely unavailable to the public, said historians Larry Berman of UC Davis and William Burr of the National Security Archive.

The blanket closure of entire collections, they suggested in an April 29 letter (pdf), is “wholly inconsistent with the spirit of the new presidential administration.”

As an alternative, Berman and Burr asked the Navy to at least permit expedited review of specific records in response to researcher interests, as the National Archives did when it implemented a similar Kyl-Lott review. Earlier this month, their proposal was denied.

“I regret to inform you that the Navy is unable to support your request at this time due to previously established government declassification priorities,” wrote Vice Admiral J.C. Harvey, Jr. (pdf), Director of the Navy Staff on July 1.

Not only that, he said, but the barriers preventing public access to Navy historical records will remain in place for at least several years to come. “A Kyl-Lott review of the NHHC holdings may start in 2012 barring any change in, or additions to, government priorities.”

Until then, researchers interested in Navy history are stymied. “Any researcher who wants to look at Navy records from the early 1960s forward is frozen out by this policy,” said Mr. Burr of the National Security Archive. “If David Vine, the author of the recent book on Diego Garcia ‘Island of Shame,’ which made good use of records at the Navy Yard, was starting his work this year he would be totally out of luck.”

Faced with such an uncompromising response, researchers can still employ the Freedom of Information Act, which is arguably even more burdensome for the government to implement but which is legally enforceable.

But Prof. Berman said this option was problematic as well. The Navy “denied access to their finding aids because they feared this would ease my FOIA request,” he said. And Navy officials also denied his request for a FOIA fee waiver on the extraordinary grounds that the records he requested will be used to support his work on the first scholarly biography of Admiral Elmo Zumwalt. “Imagine that, a historian plans to write a book,” he said.

It is well established in FOIA case law that scholarship, like news gathering, is not a private commercial interest that would disqualify a requester from receiving a fee waiver. Prof. Berman said he would appeal the denial.

New Light on Intelligence Notifications to Congress

The White House has threatened to veto the FY2010 intelligence bill if it amends the National Security Act to permit expanded notification of sensitive intelligence activities to more members of the intelligence committees, as the House Intelligence Committee proposed. However, based on the findings of a new report from the Congressional Research Service, the controversial amendment may not be necessary in order to achieve the intended result.

The new CRS report (pdf) explains the role of the “Gang of Four,” meaning the chairmen and ranking members of the House and Senate Intelligence Committees, who are to be informed of particularly sensitive intelligence activities. (When the Bush Administration first notified Congress of its warrantless surveillance program, it limited the disclosure to the “Gang of Four.”)

The “Gang of Four,” the CRS explains, is distinct from the “Gang of Eight,” which includes the leaders of the intelligence committees as well as the majority and minority leaders of the House and Senate. The Gang of Eight is notified regarding sensitive covert action programs. The Gang of Four is notified in cases of certain non-covert action intelligence programs, mainly sensitive intelligence collection programs. The Gang of Eight has a basis in statute. The Gang of Four does not.

Both notification arrangements have been criticized for unduly restricting the ability of congressional leaders to consult colleagues and staff. Rep. Jane Harman, for example, complained in 2006 that members of the Gang of Eight who are granted official notifications of covert actions “cannot take notes, seek the advice of their counsel, or even discuss the issues raised with their committee colleagues.” It is these sort of restrictions that the proposed House amendment aimed to revise.

But remarkably, the idea that such internal disclosures are barred seems to be more a matter of convention than a binding requirement, the CRS report concluded.

“There arguably is no provision in statute that restricts whether and how the Chairman and Ranking Members of the intelligence committees share with committee members information pertaining to intelligence activities that the executive branch has provided only to the committee leadership, either through Gang of Four or Gang of Eight notifications. Nor apparently is there any statutory provision which sets forth any procedures that would govern the access of appropriately cleared committee staff to such classified information.”

And as a matter of fact, “there have been instances when intelligence committee leadership has decided to inform the full membership of the intelligence committees of certain Gang of Four notifications,” the CRS found.

A copy of the CRS report was obtained by Secrecy News. See “‘Gang of Four’ Congressional Intelligence Notifications,” July 14, 2009.

Some More From CRS

Other noteworthy new Congressional Research Service reports that have not previously been made available online include (both pdf):

“Afghanistan: U.S. Foreign Assistance,” July 8, 2009.

“Chemical Facility Security: Reauthorization, Policy Issues, and Options for Congress,” July 13, 2009.

Classified Intelligence Leaks, 2001-2008

Between September 2001 and February 2008, the Federal Bureau of Investigation initiated and closed the investigation of 85 reported leaks of classified intelligence information, “all of which concerned unauthorized disclosures of classified information to the media,” FBI Director Robert S. Mueller III told the Senate Intelligence Committee in a written response to questions (pdf) dated February 4, 2008.

“None of these cases reached prosecution,” he said. As of February 2008, “21 such cases are [still] under investigation.”

This information appeared in questions for the record that were appended to “Current and Projected National Security Threats to the United States” (pdf), a hearing before the Senate Intelligence Committee that was held January 11, 2007. The complete hearing volume was finally published last month, and the newly published questions for the record are excerpted here.

The Senate Intelligence Committee has renewed its practice of including questions for the record (QFRs) in published hearing volumes, for which one may be thankful, even when the answers are classified or are not provided by the agencies at all. Some additional QFRs, also newly published last month, appear in “Statutory Authorities of the Director of National Intelligence” (pdf), Senate Intelligence Committee, February 14, 2008.