Carter Page: Corruption Can Erode Secrecy Authority

Corruption in the executive branch diminishes the ability of federal agencies to preserve secrecy, wrote a then-21 year old named Carter Page in 1993 when he was a midshipman at the U.S. Naval Academy. See Balancing Congressional Needs for Classified Information: A Case Study of the Strategic Defense Initiative by Carter W. Page, May 17, 1993.

More than two and a half decades later, Page’s own experience as an improper target of government surveillance tends to prove his thesis.

A series of FBI applications under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) identified Page, a former Trump adviser who had contacts with Russian government officials, as a purported agent of a foreign power. Those FBI applications were declassified and disclosed last year — the first time such documents had ever been made public — following indications that they were based on erroneous claims. Corruption, as Page had written, led to an erosion of longstanding secrecy practices.

Last week, the Department of Justice Inspector General confirmed that the Page surveillance applications were indeed defective.

“We identified at least 17 significant errors or omissions in the Carter Page FISA applications,” wrote Inspector General Michael Horowitz. The omissions included exculpatory information concerning Page that had been improperly altered by an FBI attorney.

The fact that “so many basic and fundamental errors were made” in the Carter Page case has called into question the management of the entire FISA process, Inspector General Horowitz wrote, casting a new spotlight on FISA policy and practice.

“Secrecy is an important element of power,” wrote the young midshipman Page in his 1993 report on congressional access to classified information. Official secrecy practices, he contended, are determined more by political currents than through rational or legal argumentation.

“While the sheer forces of law may be felt to some extent within this struggle, the final outcome is most often one which is based on politics,” he wrote.

“Corruption may decrease an executive’s claim to information,” he argued, particularly since “Congress is much less likely to request secret information from federal agencies which have proven themselves to run in a veracious [i.e. truthful] manner.”

Mr. Page said via email that his 1993 Naval Academy report was “inspired in significant part by prior work with Senator [Daniel Patrick] Moynihan,” whom he had served as an aide.

Pentagon Slams Door On Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Transparency

The Pentagon has decided not to disclose the current number of nuclear weapons in the Defense Department’s nuclear weapons stockpile. The decision, which came as a denial of a request from FAS’s Steven Aftergood for declassification of the 2018 nuclear weapons stockpile number, reverses the U.S. practice from the past nine years and represents an unnecessary and counterproductive reversal of nuclear policy.

The United States in 2010 for the first time declassified the entire history of its nuclear weapons stockpile size, a decision that has since been used by officials to support U.S. non-proliferation policy by demonstrating U.S. adherence to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), providing transparency about U.S. nuclear weapons policy, counter false rumors about secretly building up its nuclear arsenal, and to encourage other nuclear-armed states to be more transparent about their arsenals.

Importantly, the U.S. also disclosed the number of warheads dismantled each year back to 1994. This disclosure helped document that the United States was not hiding retired weapons but actually dismantling them. In 2014, the United States even declassified the total inventory of retired warheads still awaiting dismantlement at that time: 2,500.

The 2010 release built on previous disclosures, most importantly the Department of Energy’s declassification decisions in 1996, which included – among other issues – a table of nuclear weapons stockpile data with information about stockpile numbers, megatonnage, builds, retirements, and disassemblies between 1945 and 1994. Unfortunately, the web site is poorly maintained and the original page headlined “Declassification of Certain Characteristics of the United States Nuclear Weapon Stockpile” no longer has tables, another page is corrupted, but the raw data is still available here. Clearly, DOE should fix the site.

The decision in 2010 to disclose the size of the stockpile and the dismantlement numbers did not mean the numbers would necessarily be updated each subsequent year. Each year was a separate declassification decision that was announced on the DOD Open Government web site. The most recent decision from 2018 in response to a request from FAS showed the stockpile number as of September 2017: 3,822 stockpiled warheads and 354 dismantled warheads.

The 2017 number was extra good news because it showed the Trump administration, despite bombastic rhetoric from the president, had continued to reduce the size of the stockpile (see my analysis from 2018).

Since 2010, Britain and France have both followed the U.S. example by providing additional information about the size of their arsenals, although they have yet to disclose the entire history of their warhead inventories. Russia, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea have not yet provided information about the size or history of their arsenals.

FAS’ Role In Providing Nuclear Transparency

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has been tracking nuclear arsenals for many years, previously in collaboration with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). The 5,113-warhead stockpile number declassified by the Obama administration in 2010 was only 13 warheads off the FAS/NRDC estimate at the time.

We provide these estimates on our web site, on our Strategic Security Blog, and in publications such as the bi-monthly Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and the annual nuclear forces chapter in the SIPRI Yearbook. The work is used extensively by journalists, NGOs, scholars, parliamentarians, and government officials.

With the Pentagon decision to close the books on the stockpile, and the rampant nuclear modernization underway worldwide, the role of FAS and others in documenting the status of nuclear forces will be even more important.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The Pentagon’s decision not to disclose the 2018 nuclear weapons stockpiled and dismantled warhead numbers is unnecessary and counterproductive.

The United States or its allies are not suffering or at a disadvantage because the nuclear stockpile numbers are in the public. Indeed, there seems to be no rational national security factor that justifies the decision to reinstate nuclear stockpile secrecy.

The decision walks back nearly a decade of U.S. nuclear weapons transparency policy – in fact, longer if including stockpile transparency initiatives in the late-1990s – and places the United States is the same box as over-secretive nuclear-armed states, several of which are U.S. adversaries.

The decision also puts the United States in an even more disadvantageous position for next year’s nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) review conference where the administration will be unable to report progress on meeting its Article VI obligations. Instead, this decision, as well as decisions to withdraw from the INF treaty, start producing new nuclear weapons, and the absence of nuclear arms control negotiations, needlessly open up the United States to criticism from other Parties to the NPT – a treaty the United States needs to protect and strengthen to curtail nuclear proliferation.

The decision also puts U.S. allies like Britain and France in the awkward position of having to reconsider their nuclear transparency policies as well or be seen to be out of sync with their largest military ally at a time of increased East-West hostilities.

With this decision, the Trump administration surrenders any pressure on other nuclear-armed states to be more transparent about the size of their nuclear weapon stockpiles. This is curious since the Trump administration had repeatedly complained about secrecy in the Russian and Chinese arsenals. Instead, it now appears to endorse their secrecy.

The decision will undoubtedly fuel suspicion and worst-case mindsets in adversarial countries. Russia will now likely argue that not only has the United States obscured conversion of nuclear launchers under the New START treaty, it has now decided also to keep secret the number of nuclear warheads it has available for them.

Finally, the decision also makes it harder to envision achieving new arms control agreements with Russia and China to curtail their nuclear arsenals. After all, if the United States is not willing to maintain transparency of its warhead inventory, why should they disclose theirs?

It is yet unclear why the decision not to disclose the 2018 stockpile number was made. There are several possibilities:

- Is it because the chaos and incompetence in the Trump administration have enabled hardliners and secrecy zealots to reverse a policy they disagreed with anyway?

- Is it a result of the Nuclear Posture Review’s embrace of Great Power Competition with Cold War-like instincts to increase reliance on nuclear weapons, kill arms control treaties, increase secrecy, and scuttle policies that some say appease adversaries?

- Is it because of a Trump administration mindset opposing anything created by president Obama?

- Or is it because the United States has secretly begun to increase the size of its nuclear stockpile? (I don’t think so; the stockpile appears to have continued to decrease to now at or just below 3,800 warheads.)

The answer may be as simple as “because it can” with no opposition from the White House. Whatever the reason, the decision to reinstate stockpile secrecy caps a startling and rapid transformation of U.S. nuclear policy. Within just a little over two years, the United States under the chaotic and disastrous policies of the Trump administration has gone from promoting nuclear transparency, arms control, and nuclear constraint to increasing nuclear secrecy, abandoning arms control agreements, producing new nuclear weapons, and increasing reliance on such weapons in the name of Great Power Competition.

This is a historic policy reversal by any standard and one that demands the utmost effort on the part of Congress and the 2020 presidential election candidates to prevent the United States from essentially going nuclear rogue but return it to a more constructive nuclear weapons policy.

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Trump Says DoD IG Reports Should Be “Private”

The recurring dispute over the appropriate degree of secrecy in the Department of Defense arose in a new form last week when President Trump said that certain audits and investigations that are performed by the DoD Inspector General should no longer be made public.

“We’re fighting wars, and they’re doing reports and releasing it to the public? Now, the public means the enemy,” the President said at a January 2 cabinet meeting. “The enemy reads those reports; they study every line of it. Those reports should be private reports. Let him do a report, but they should be private reports and be locked up.”

It is not clear what the President had in mind. Did he have reason to think that US military operations had been damaged by publication of Inspector General reports? Was he now directing the Secretary of Defense to classify such reports, regardless of their specific contents? Was he suggesting the need for a new exemption from the Freedom of Information Act to prevent their disclosure?

Or was this simply an expression of presidential pique with no practical consequence? Thus far, there has been no sign of any change to DoD publication policy in response to the President’s remarks.

Meanwhile, Rep. Adam Smith, the incoming chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, reiterated his view to the contrary that the Pentagon needs to be more forthcoming with information, not less.

“As Chairman, I will work with my colleagues to promote transparency and Congressional oversight, enhance military readiness, combat inefficiency and waste at DOD, advance green technology in defense and address the threat climate change poses to our national security, fight for an inclusive military, and move towards a responsible approach to nuclear weapons,” he said on January 4. (And, he wrote earlier, “Constant misinformation from the president is a real problem in a democratic society.”)

There are indications that some Pentagon officials may be receptive to Chairman Smith’s concerns.

After reporters complained about the growing use of “For Official Use Only” markings to restrict access to information, Under Secretary of Defense (acquisition and sustainment) Ellen Lord responded that “I understand the need, the requirement” for transparency, “and I will put out guidance to make everything open to the public to the degree we can.” See “Pentagon’s Chief Weapons Buyer Promises Less Secrecy in Reports” by Anthony Capaccio, Bloomberg, January 4.

While secrecy in the Department of Defense has increased noticeably in the Trump Administration, the Pentagon remains an astonishingly prolific publisher of military information, issuing dozens or hundreds of directives, manuals, reports and other publications each day. Most are the product of routine bureaucratic churning, and are of little if any significance, but some have broader interest or appeal. Here are a few that caught our eye.

Techniques for Visual Information Operations, ATP 6-02.40, US Army, January 3, 2019

Military Diving Operations: Multi-Service Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures, ATP 3-34.84, January 2, 2019

DoD support to non-contiguous States and territories in response to disasters, threats, and emergencies, report to Congress, n.d. (Nov. 2018)

The U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028, TRADOC Pamphlet 525-3-1, 6 December 2018

DoD Scientific and Technical Information Program (STIP), DoD Instruction 3200.12, August 22, 2013, Incorporating Change 3, Effective December 17, 2018

The latter document directs that “DoD will maximize the free flow of scientific and engineering information developed by or for DoD to the public.”

Israel’s Official Map Replaces Military Bases with Fake Farms and Deserts

Somewhat unexpectedly, a blog post that I wrote last week caught fire internationally. On Monday, I reported that Yandex Maps—Russia’s equivalent to Google Maps—had inadvertently revealed over 300 military and political facilities in Turkey and Israel by attempting to blur them out.

In a strange turn of events, the fallout from that story has actually produced a whole new one.

After the story blew up, Yandex pointed out that its efforts to obscure these sites are consistent with its requirement to comply with local regulations. Yandex’s statement also notes that “our mapping product in Israel conforms to the national public map published by the government of Israel as it pertains to the blurring of military assets and locations.”

The “national public map” to which Yandex refers is the official online map of Israel which is maintained by the Israeli Mapping Centre (מרכז למיפוי ישראל) within the Israeli government. Since Yandex claims to take its cue from this map, I wondered whether that meant that the Israeli government was also selectively obscuring sites on its national map.

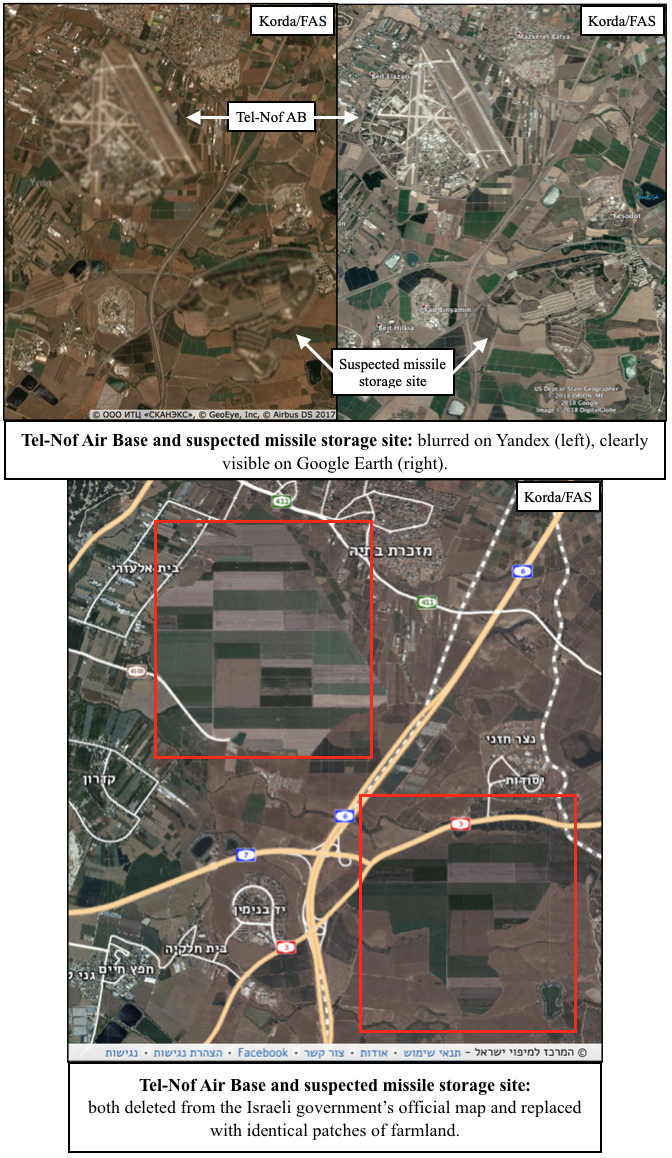

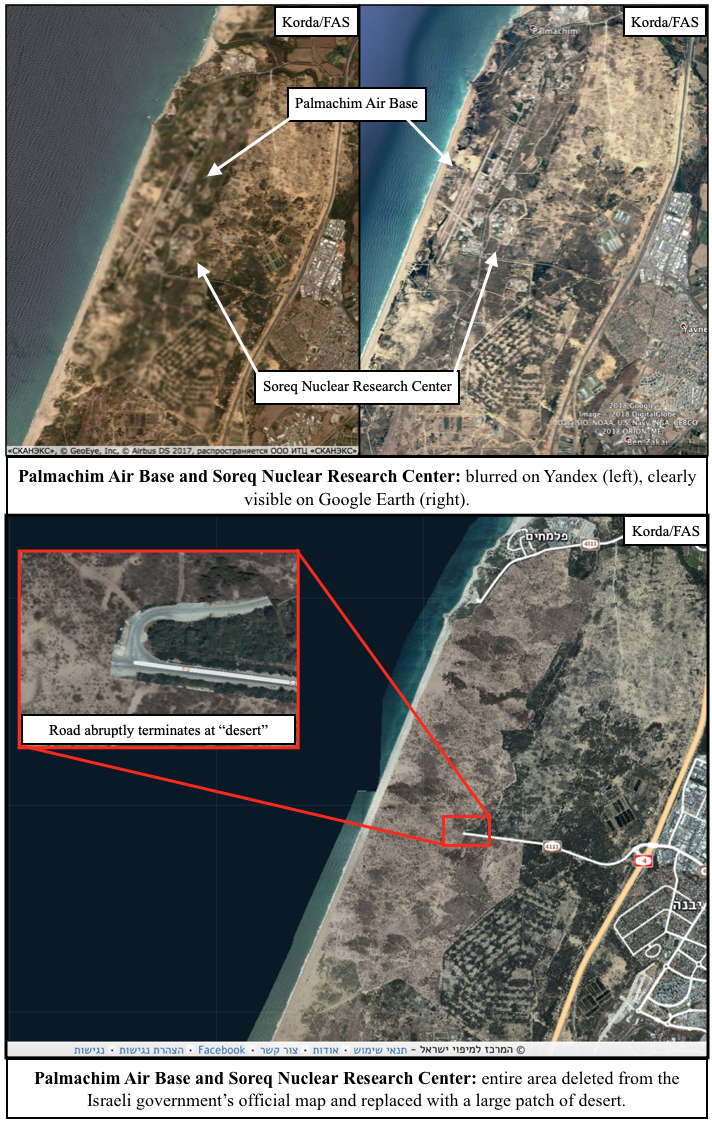

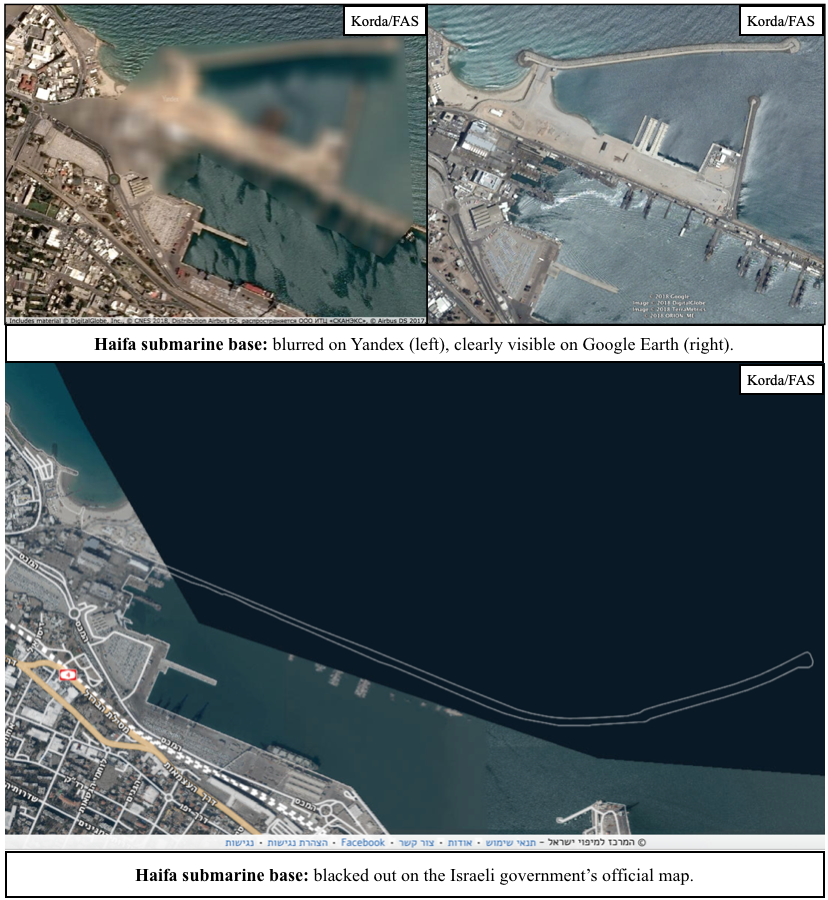

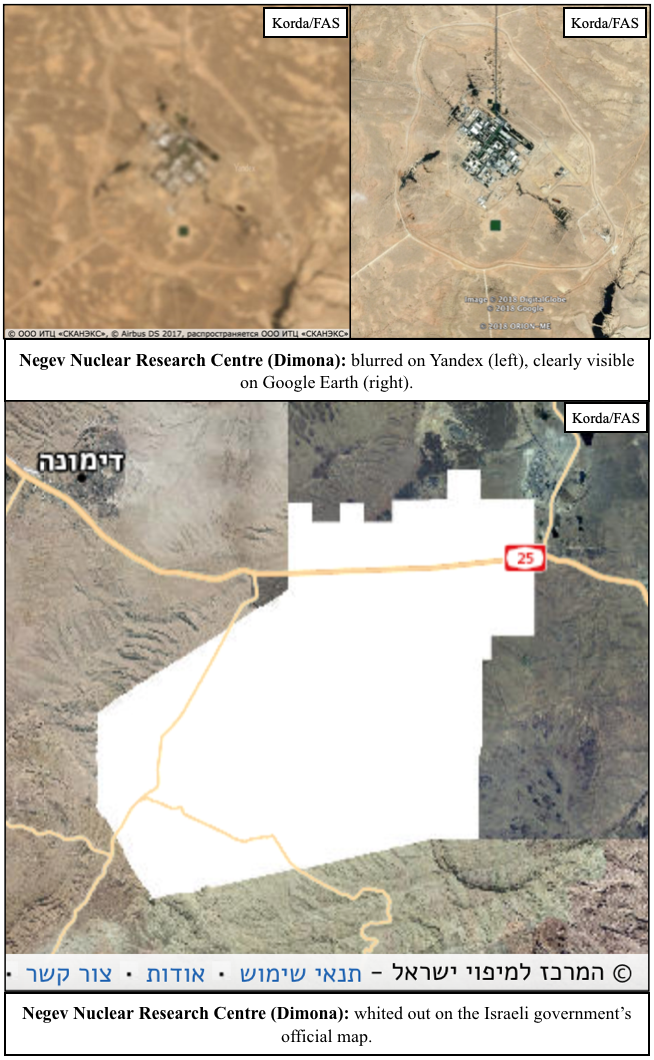

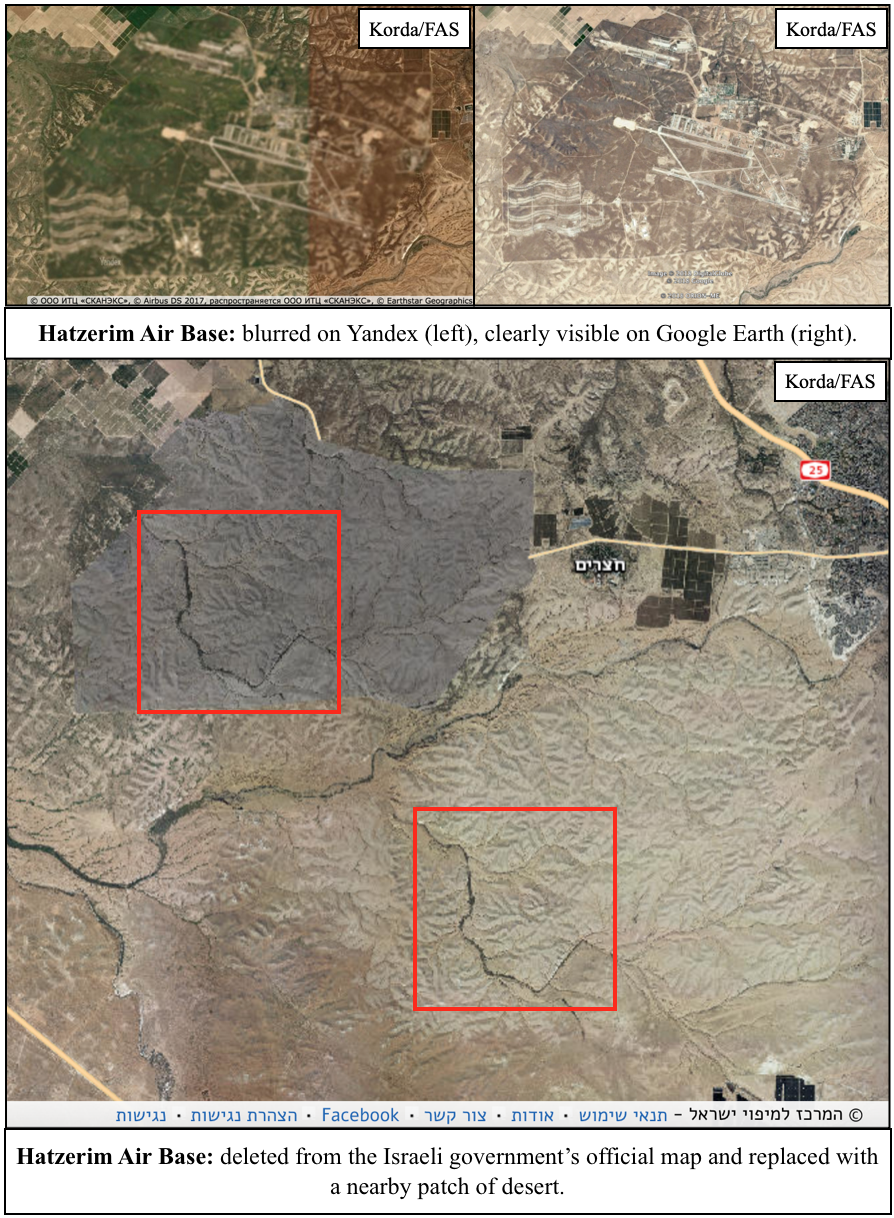

I wasn’t wrong. In fact, the Israeli government goes well beyond just blurring things out. They’re actually deleting entire facilities from the map—and quite messily, at that. Usually, these sites are replaced with patches of fake farmland or desert, but sometimes they’re simply painted over with white or black splotches.

Some of the more obvious examples of Israeli censorship include nuclear facilities:

- Tel-Nof Air Base is just down the road from a suspected missile storage site, both of which have been painted over with identical patches of farmland.

- Palmachim Air Base doubles as a test launch site for Jericho missiles and is collocated with the Soreq Nuclear Research Center, which is rumoured to be responsible for nuclear weapons research and design. The entire area has been replaced with a fake desert.

- The Haifa Naval Base includes pens for submarines that are rumoured to be nuclear-capable, and is entirely blacked out on the official map.

- The Negev Nuclear Research Center at Dimona is responsible for plutonium and tritium production for Israel’s nuclear weapons program, and has been entirely whited out on the official map.

- Hatzerim Air Base has no known connection to Israel’s nuclear weapons program; however, the sloppy method that was used to mask its existence (by basically just copy-pasting a highly-distinctive and differently-coloured patch of desert to an area only five kilometres away) was too good to leave out.

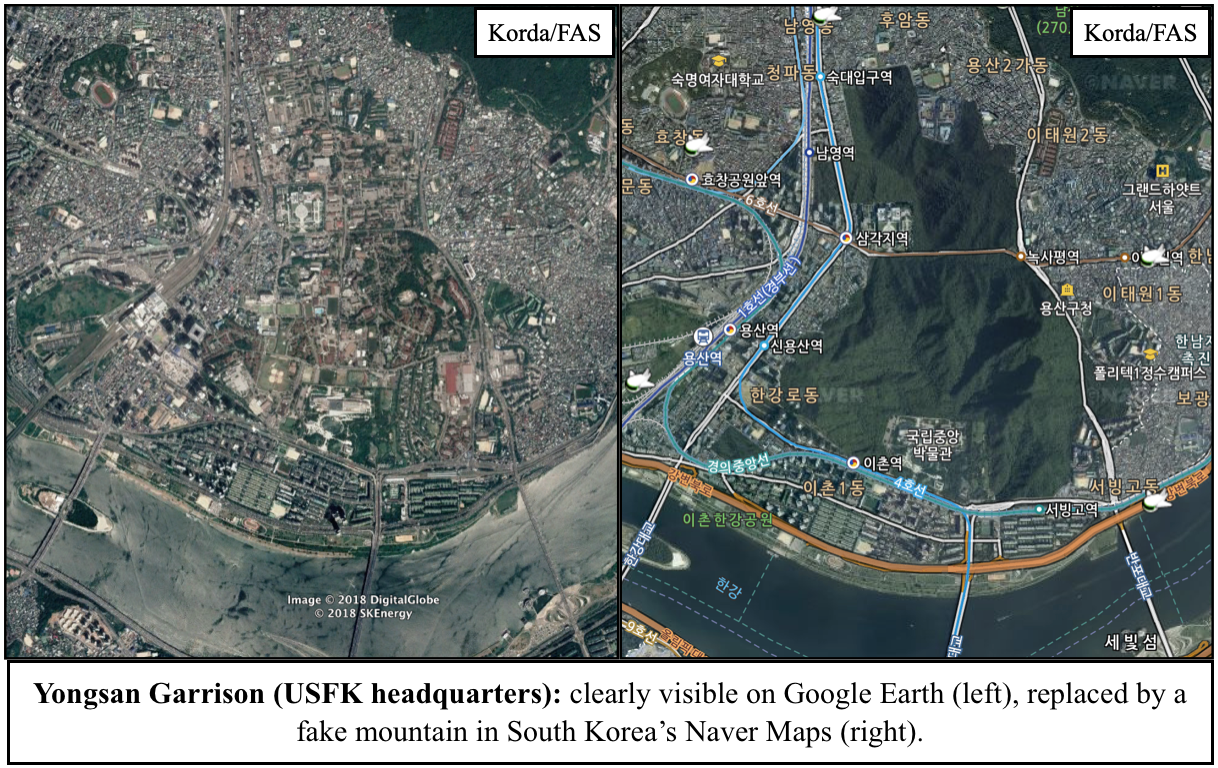

Given that all of these locations are easily visible through Google Earth and other mapping platforms, Israel’s official map is a prime example of needless censorship. But Israel isn’t the only one guilty of silly secrecy: South Korea’s Naver Maps regularly paints over sensitive sites with fake mountains or digital trees, and in a particularly egregious case, the Belgian Ministry of Defense is actually suing Google for not complying with its requests to blur out its military facilities.

Before the proliferation of high-resolution satellite imagery, obscuring aerial photos of military facilities was certainly an effective method for states to safeguard their sensitive data. However, now that anyone with an internet connection can freely access these images, it simply makes no sense to persist with these unnecessary censorship practices–especially since these methods can often backfire and draw attention to the exact sites that they’re supposed to be hiding.

Case studies like Yandex and Strava—in which the locations of secret military facilities were revealed through the publication of fitness heat-maps—should prompt governments to recognize that their data is becoming increasingly accessible through open-source methods. Correspondingly, they should take the relevant steps to secure information that is absolutely critical to national security, and be much more publicly transparent with information that is not—hopefully doing away with needless censorship in the process.

Invention Secrecy Hits Recent High

Last year the number of patent applications that were subject to a “secrecy order” under the Invention Secrecy Act of 1951 was the highest that it has been in more than two decades, according to data obtained from the US Patent and Trademark Office.

Whenever disclosure of a new invention is deemed to be “detrimental to national security,” a secrecy order may be imposed on the patent application, preventing its public disclosure and blocking issuance of the patent. Most affected inventions seem to involve technologies that have military uses. But the current criteria that are used to make the determination have not been released, so the actual scope of invention secrecy is not publicly known.

At the end of FY 2018 (September 30, 2018), there were 5,792 secrecy orders in effect, up slightly from 5,784 the year before.

There were 85 new orders imposed, and 77 existing orders that were rescinded. The remaining orders, which were originally imposed in previous years, were renewed. Among the new orders, there were 43 that were imposed on private inventors (i.e., not government employees or contractors). These so-called “John Doe” secrecy orders are a constitutionally suspect category, since they involve prior restraint on the speech of a private citizen or business.

The new total of 5,792 secrecy orders in effect is the highest since 1993, when the total was 5,909.

When a secrecy order is rescinded — years or sometimes decades after it was imposed — the invention may finally be patented.

When asked whether any of the inventions that were released from a secrecy order in 2018 had subsequently been patented, the US Patent and Trademark Office said it had no record of such patents.

See, relatedly, “The U.S. Government’s Secret Inventions” by Arvind Dilawar, Slate, May 9, 2018.

Growing Pentagon Secrecy Draws Questions

In just the last few weeks and months, U.S. military officials imposed new restrictions on media interviews and base visits, at least temporarily; they blocked (but later permitted) publication of current data on the extent of insurgent control of Afghanistan; and they classified previously unclassified information concerning future flight tests of ballistic missile defense systems.

“We’ve seen multiple instances in the past year where the [military] services have sought to be more guarded in their transparency and accessibility to the media,” said Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-WI) at an April 12 hearing of the House Armed Services Committee. “Part of that’s understandable, but I think transparency is needed now more than ever.”

Defense Secretary James Mattis said in response that he didn’t exactly disagree.

“I want more engagement with the media, [but] I want you to give your name, I don’t want to read that somebody spoke on condition of anonymity because they weren’t authorized to speak,” Mattis said.

“I have yet to tell anyone they’re not authorized to speak. So if they’re not willing to say they know about the issue and give their name that would concern me. If they’re giving background, they should just be a defense official giving background information authorized to give it.”

“What I don’t want is pre-decisional information, or classified information or any information about upcoming military movements or operations, which is the normal lose lips sink ships kind of restriction.”

“Pre-decisional, we do not close the president’s decision making maneuver space by saying things before the president has made a decision. But otherwise, I want more engagement with the military, and I don’t want to see an increase in opaqueness about what we’re doing.”

“We’re already remote enough from the American people by our size and by our continued focus overseas. We need to be more engaged here at home,” Secretary Mattis said.

Part of that is understandable, as Rep. Gallagher said. But it does not correspond to, or justify, the way that DoD conducts itself in practice, which has certainly produced “an increase in opaqueness.”

Last week, for example, DoD published its regular quarterly report for December 2017 on the number of US troops deployed abroad — but now with the number of troops in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan deleted. See Pentagon strips Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria troop numbers from web by Tara Copp, Military Times, April 9. (Previously disclosed numbers in prior quarterly reports were also deleted but then reposted last week.)

Citing the new secrecy, Rep. Jackie Speier (D-CA) said “I’m very concerned about that. I think that there’s no combat advantage to obfuscating the number of U.S. service members that were in these countries three months ago. And, furthermore, the American public has a right to know. Do you intend to restore that information to the website?,” she asked Secretary Mattis at last week’s hearing.

“I’ll certainly look at it,” he replied. “I share your conviction that the American people should know everything that doesn’t give the enemy an advantage.”

The Expanding Secrecy of the Afghanistan War

Last year, dozens of categories of previously unclassified information about Afghan military forces were designated as classified, making it more difficult to publicly track the progress of the war in Afghanistan.

The categories of now-classified information were tabulated in a memo dated October 31, 2017 that was prepared by the staff of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), John Sopko.

In the judgment of the memo authors, “None of the material now classified or otherwise restricted discloses information that could threaten the U.S. or Afghan missions (such as detailed strategy, plans, timelines, or tactics).”

But “All of the [newly withheld] data include key metrics and assessments that are essential to understanding mission success for the reconstruction of Afghanistan’s security institutions and armed forces.”

So what used to be available that is now being withheld?

“It is basically casualty, force strength, equipment, operational readiness, attrition figures, as well as performance assessments,” said Mr. Sopko, the SIGAR.

“Using the new [classification criteria], I would not be able to tell you in a public setting or the American people how their money is being spent,” Mr. Sopko told Congress at a hearing last November.

The SIGAR staff memo tabulating the new classification categories was included as an attachment for the hearing record, which was published last month. See Overview of 16 Years of Involvement in Afghanistan, hearing before the House Government Oversight and Reform Committee, November 1, 2017.

In many cases, the information was classified by NATO or the Pentagon at the request of the Government of Afghanistan.

“Do you think that it is an appropriate justification for DOD to classify previously unclassified information based on a request from the Afghan Government?,” asked Rep. Val Demings (D-FL). “Why or why not?”

“I do not because I believe in transparency,” replied Mr. Sopko, “and I think the loss of transparency is bad not only for us, but it is also bad for the Afghan people.”

“All of this [now classified] material is historical in nature (usually between one and three months old) because of delays incurred by reporting time frames, and thus only provides ‘snapshot’ data points for particular periods of time in the past,” according to the SIGAR staff memo.

“All of the data points [that were] classified or restricted are ‘top-line’ (not unit-level) data. SIGAR currently does not publicly report potentially sensitive, unit-specific data.”

Yesterday at a hearing of the House Armed Services Committee, Rep. Walter Jones (R-NC) asked Secretary of Defense James N. Mattis about the growing restrictions on information about the war in Afghanistan.

“We are now increasing the number of our troops in Afghanistan, and after 16 years, the American people have a right to know of their successes. Some of that, I’m sure it is classified information, which I can understand. But I also know that we’re not getting the kind of information that we need to get to know what successes we’re having. And after 16 years, I do not think we’re having any successes,” Rep. Jones said.

Secretary Mattis said that the latest restriction of unclassified information about the extent of Taliban or government control over Afghanistan that was withheld from the January 2018 SIGAR quarterly report had been “a mistake.” He added, “That information is now available.” But Secretary Mattis did not address the larger pattern of classifying previously unclassified information about Afghan forces that was discussed at the November 2017 hearing.

Invention Secrecy Activity Rises Slightly

A total of 5,784 patent applications remained subject to invention secrecy orders at the end of Fiscal Year 17, according to new data provided by the US Patent and Trademark Office.

The secrecy orders, issued under the Invention Secrecy Act of 1951, restrict disclosure of patent applications considered to be “detrimental to national security” if published.

That total number was up slightly from the 5,680 secrecy orders that were in effect a year earlier.

Most existing patent secrecy orders are renewed year after year.

In FY17, there were 132 new secrecy orders that were imposed, and 28 existing orders that were rescinded, according to the US PTO data. There were 39 new “John Doe” orders imposed on private inventors who sought to patent inventions in which the government has no property interest.

Most invention secrecy applies to inventions involving technology relevant to military applications, but the full scope of the invention secrecy program is not described in public documents.

Patents Granted to Two Formerly Secret Inventions

Two patent applications that had been subject to “secrecy orders” under the Invention Secrecy Act for years or decades were finally granted patents and publicly disclosed in 2016.

“Only two patents have been granted so far on cases in which the secrecy order was rescinded in FY16,” the US Patent and Trademark Office said this week in response to a Freedom of Information Act request. They were among the 20 inventions whose secrecy orders were rescinded over the past year.

One of the patents concerns “a controllable barrier layer against electromagnetic radiation, to be used, inter alia, as a radome for a radar antenna for instance.” The inventor, Anders Grop of Sweden, filed the patent application in 2007 and it was granted on April 5, 2016 (patent number 9,306,290).

The other formerly secret invention that finally received a patent this year described “multi-charge munitions, incorporating hole-boring charge assemblies.” Detonation of the munitions is “suitable for defeating a concrete target.” That invention was originally filed in 1990 by Kevin Mark Powell and Edward Evans of the United Kingdom and was granted on October 25, 2016 (patent number 9,476,682).

The inventors could not immediately be contacted for comment. But judging from appearances, the decision to control the disclosure of these two inventions for a period of time and then to grant them a patent was consistent with the terms of the Invention Secrecy Act, and it had no obvious adverse impacts.

Invention Secrecy Increased in 2016

There were 5,680 invention secrecy orders in effect at the end of Fiscal Year 2016. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office reported that 121 new secrecy orders were issued in 2016, but also that 20 existing orders were rescinded, for a net increase of 101 over the year before. The latest figures were released under the Freedom of Information Act.

The government may impose a “secrecy order” on a patent application under the Invention Secrecy Act of 1951 if it believes that disclosure of the underlying invention would be “detrimental to national security.” Under those circumstances, a patent is withheld and the inventor is prohibited from revealing the invention unless and until the secrecy order is withdrawn.

The majority of secrecy orders apply to inventions that were developed with government sponsorship, in national or military laboratories or by government-funded contractors. So the ensuing secrecy amounts to the government silencing itself.

In a subset of cases, however, secrecy orders are imposed on private inventors who developed their idea without government support. There were 49 such orders in FY 2016. These orders, known as “John Doe” secrecy orders, seem like a form of prior restraint on individual speech that would be arguably inconsistent with the First Amendment.

But there have been few constitutional challenges to the Invention Secrecy Act to date, and none that has dislodged or modified the Act.

In 2014, inventors Budimir Damnjanovic and Desanka Damnjanovic filed a lawsuit seeking compensation for a secrecy order that the U.S. Air Force imposed on them. They also argued that the Invention Secrecy Act itself was unconstitutional.

“Because the Patent Secrecy Act prohibits Plaintiffs from speaking of their Invention to third parties, including potential customers, it violates the First Amendment of the Constitution,” their May 14, 2014 complaint stated.

Moreover, “the Patent Secrecy Act has resulted in Plaintiffs being deprived of property without due process and just compensation in violation of the Fifth Amendment.”

The court dismissed the constitutional claim because by that time the secrecy orders had been lifted and therefore, the court determined, the inventors did not have standing to make their constitutional case.

“Plaintiffs’ First Amendment argument fails because the harms they claim they suffered are past injuries. Further, the purported prohibition on speech Plaintiffs allegedly endured is not an ongoing issue, given that the secrecy orders have been lifted,” according to a September 22, 2015 court order. (Damnjanovic v. US Air Force, E.D. of Michigan, S. Div., 14-11920).

Ultimately, however, the parties reached a settlement regarding the compensation issues, and in December 2015 the government agreed to pay the inventors a lump sum of $63,000 to dismiss the case.

For related background, see “Congratulations, Your Genius Patent is Now a Military Secret” by Joshua Brustein, Bloomberg, June 8, 2016.

The Department of Defense published a proposed rule in the Federal Register today on “Withholding of Unclassified Technical Data and Technology From Public Disclosure.”

The rule “is meant to control the transfer of technical data and technology contributing to the military potential of any country or countries, groups, or individuals that could prove detrimental to U.S, national security or critical interests.”

“For the purposes of this regulation, public disclosure of technical data and technology is the same as providing uncontrolled foreign access. This rule instructs DoD employees, contractors, and grantees to ensure unclassified technical data and technology that discloses technology or information with a military or space application may not be exported without authorization and should be controlled and disseminated consistent with U.S. export control laws and regulations.”

Government Secrecy and Censorship

From its beginning, the Federation of American Scientists has been immersed in policies and issues regarding government secrecy and censorship. By the time World War II broke out, the fission process had been observed, followed by detection of the neutron, and recognition of induced uranium fission. In the early 1940s, some scientists in the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and Germany realized the potential for nuclear weapons.

The three atomic bombs detonated in the summer of 1945 were created and assembled at secret U.S. government sites by a mixed pedigree of scientists, engineers, and military officers. The decision to drop two of them on Japanese cities was determined by military and political events then occurring, particularly in the final year of World War II.

Our Soviet wartime ally, excluded from the American, British, and Canadian nuclear coalition, used its own espionage network to remain informed. Well-placed sympathizers and spies conveyed many essential details of nuclear-explosive development. Through this network, Stalin learned of the Manhattan Project and the Trinity test. As the German invaders began to retreat from Soviet borders, he established his own secret nuclear development project.

Frequent contributor and longtime FAS member Dr. Alexander DeVolpi has just published a new book, Cold War Brinkmanship. Dr. DeVolpi’s firsthand account “chronicles the half-century nuclear crisis,” with several mentions of and citations to the work of FAS. It is available now in paperback on Amazon.

Nuclear Transparency and the Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan

By Hans M. Kristensen

By Hans M. Kristensen

I was reading through the latest Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan from the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) and wondering what I should pick to critique the Obama administration’s nuclear policy.

After all, there are plenty of issues that deserve to be addressed, including:

– Why NNSA continues to overspend and over-commit and create a spending bow wave in 2021-2026 in excess of the President’s budget in exactly the same time period that excessive Air Force and Navy modernization programs are expected to put the greatest pressure on defense spending?

– Why a smaller and smaller nuclear weapons stockpile with fewer warhead types appears to be getting more and more expensive to maintain?

– Why each warhead life-extension program is getting ever more ambitious and expensive with no apparent end in sight?

– And why a policy of reductions, no new nuclear weapons, no pursuit of new military missions or new capabilities for nuclear weapons, restraint, a pledge to “put an end to Cold War thinking,” and the goal of disarmament, instead became a blueprint for nuclear overreach with record funding, across-the-board modernizations, unprecedented warhead modifications, increasing weapons accuracy and effectiveness, reaffirmation of a Triad and non-strategic nuclear weapons, continuation of counterforce strategy, reaffirmation of the importance and salience of nuclear weapons, and an open-ended commitment to retain nuclear weapons further into the future than they have existed so far?

What About The Other Nuclear-Armed States?

Despite the contradictions and flaws of the administration’s nuclear policy, however, imagine if the other nuclear-armed states also published summaries of their nuclear weapons plans. Some do disclose a little, but they could do much more. For others, however, the thought of disclosing any information about the size and composition of their nuclear arsenal seems so alien that it is almost inconceivable.

Yet that is actually one of the reasons why it is necessary to continue to work for greater (or sufficient) transparency in nuclear forces. Some nuclear-armed states believe their security depends on complete or near-compete nuclear secrecy. And, of course, some nuclear information must be protected from disclosure. But the problem with excessive secrecy is that it tends to fuel uncertainty, rumors, suspicion, exaggerations, mistrust, and worst-case assumptions in other nuclear-armed states – reactions that cause them to shape their own nuclear forces and strategies in ways that undermine security for all.

Nuclear-armed states must find a balance between legitimate secrecy and transparency. This can take a long time and it may not necessarily be the same from country to country. The United States also used to keep much more nuclear information secret and there are many institutions that will always resist public access. But maximum responsible disclosure, it turns out, is not only necessary for a healthy public debate about nuclear policy, it is also necessary to communicate to allies and adversaries what that policy is about – and, equally important, to dispel rumors and misunderstandings about what the policy is not.

Nuclear transparency is not just about pleasing the arms controllers – it is important for national security.

So here are some thoughts about what other nuclear-armed states should (or could) disclose about their nuclear arsenals – not to disclose everything but to improve communication about the role of nuclear weapons and avoid misunderstandings and counterproductive surprises:

Russia should publish:

Russia should publish:

– Full New START aggregate data numbers (these numbers are already shared with the United States, that publishes its own numbers)

– Size and history of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Number of history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has made statements about percentage reductions since 1991 but not disclosed numbers or history)

– Basic overview of which nuclear forces are nuclear-capable (has made some statements about strategic forces but not shorter-range forces)

– Plans for future years force levels of long-range nuclear forces (has made occasional statements about modernizations but no detailed plan)

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

China should publish:

China should publish:

– Size and history of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (stated in 2004 that it possessed the smallest arsenal of the nuclear weapon states but has not disclosed numbers or history)

– Basic overview of its nuclear-capable forces

– Plans for future years force levels of long-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

France should publish:

France should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (has disclosed the size of its nuclear stockpile in 2008 and 2015 (300 weapons), but not the history)

– Number and history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has declared dismantlement of some types but not history)

(France has disclosed its overall force structure and some nuclear budget information is published each year.)

Britain should publish:

Britain should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (has declared some approximate historic numbers, declared the approximate size in 2010 (no more than 225), and has declared plan for mid-2020s (no more than 180), but has not disclosed history)

– Number and history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has announced dismantlement of systems but not numbers or history)

(Britain has published information about the size of its nuclear force structure and part of its nuclear budget.)

Pakistan should publish:

Pakistan should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Basic overview of nuclear-capable forces (occasionally declares that a missile test involves nuclear-capable weapon)

– Plans for future years force levels of longer-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

India should publish:

India should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Basic overview of nuclear-capable forces (occasionally declares that a missile test involves nuclear-capable weapon)

– Plans for future years force levels of longer-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

Israel should publish:

Israel should publish:

…or should it? Unlike other nuclear-armed states, Israel has not publicly confirmed it has a nuclear arsenal and has said it will not be the first to introduce nuclear weapons in the Middle East. Some argue Israel should not confirm or declare anything because of fear it would trigger nuclear arms programs in other Middle Eastern countries.

On the other hand, the existence of the Israeli nuclear arsenal is well known to other countries as has been documented by declassified government documents in the United States. Official confirmation would be politically sensitive but not in itself change national security in the region. Moreover, the secrecy fuels speculations, exaggerations, accusations, and worst-case planning. And it is hard to see how the future of nuclear weapons in the Middle East can be addressed and resolved without some degree of official disclosure.

North Korea should publish:

North Korea should publish:

Well, obviously this nuclear-armed state is a little different (to put it mildly) because its blustering nuclear threats and statements – and the nature of its leadership itself – make it difficult to trust any official information. Perhaps this is a case where it would be more valuable to hear more about what foreign intelligence agencies know about North Korea’s nuclear arsenal. Yet official disclosure could potentially serve an important role as part of a future de-tension agreement with North Korea.

Additional information:

Status of World Nuclear Forces with links to more information about individual nuclear-armed states.

“Nuclear Weapons Base Visits: Accident and Incident Exercises as Confidence-Building Measures,” briefing to Workshop on Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Transparency and Confidence-Building Measures in Practice, German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin, 27-28 March 2014.

“Nuclear Warhead Stockpiles and Transparency” (with Robert Norris), in Global Fissile Material Report 2013, International Panel on Fissile Materials, October 2013, pp. 50-58.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.