New Report: Trimming Nuclear Excess

The US and Russian nuclear arms reduction process needs to be revitalized by new treaties and unilateral initiatives to reduce nuclear force levels, a new FAS report argues (click on image to download report).

By Hans M. Kristensen

Despite enormous reductions of their nuclear arsenals since the Cold War, the United States and Russia retain more than 9,100 warheads in their military stockpiles. Another 7,000 retired – but still intact – warheads are awaiting dismantlement, for a total inventory of more than 16,000 nuclear warheads.

This is more than 15 times the size of the total nuclear arsenals of all the seven other nuclear weapon states in the world – combined.

The U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals are far beyond what is needed for deterrence, with each side’s bloated force level justified only by the other’s excessive force level.

A new FAS report – Trimming Nuclear Excess: Options for Further Reductions of U.S. and Russian Nuclear Forces – describes the status and 10-year projection for U.S. and Russian nuclear forces.

The report concludes that the pace of reducing nuclear forces appears to be slowing compared with the past two decades. Both the United States and Russia appear to be more cautious about reducing further, placing more emphasis on “hedging” and reconstitution of reduced nuclear forces, and both are investing enormous sums of money in modernizing their nuclear forces over the next decade.

Even with the reductions expected over the next decade, the report concludes that the United States and Russia will continue to possess nuclear stockpiles that are many times greater than the rest of the world’s nuclear forces combined.

New initiatives are needed to regain the momentum of the nuclear arms reduction process. The New START Treaty from 2011 was an important but modest step but the two nuclear superpowers must begin negotiations on new treaties to significantly curtail their nuclear forces. Both have expressed an interest in reducing further, but little has happened.

New treaties may be preferable, but reaching agreement on the complex inter-connected issues ranging from nuclear weapons to missile defense and conventional forces may be unlikely to produce results in the short term (not least given the current political climate in the U.S. Congress). While the world waits, the excess nuclear forces levels and outdated planning principles continue to fuel justifications for retaining large force levels and new modernizations in both the United States and Russia.

To break the stalemate and reenergize the arms reductions process, in addition to pursuing treaty-based agreements, the report argues, unilateral steps can and should be taken in the short term to trim the most obvious fat from the nuclear arsenals. The report includes 32 specific recommendations for reducing unnecessary and counterproductive U.S. and Russian nuclear force levels unilaterally and bilaterally.

Full report: Trimming Nuclear Excess

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Cuban Missile Crisis: Nuclear Order of Battle

|

| At the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis blockade, unknown to the United States, the Soviet Union already had short-range nuclear weapons on the island, such as this FKR-1 cruise missile, that would most likely have been used against a U.S. invasion. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris

Fifty years ago the world held its breath for a few weeks as the United States and the Soviet Union teetered on the brink of nuclear war in response to the Soviet deployment of medium-range nuclear missiles in Cuba.

The United States imposed a military blockade around Cuba to keep more Soviet weapons out and prepared to invade the island if necessary. As nuclear-armed warships sparred to enforce and challenge the blockade, a few good men made momentous efforts and decisions that prevented use of nuclear weapons and eventually defused the crisis.

What the Kennedy administration did not know, however, was that the Soviet Union had 158 nuclear warheads of five types already in Cuba by the time of the blockade. This included nearly 100 warheads for short-range ballistic missiles and cruise missiles. If the invasion had been launched, as the military recommended but the White House fortunately decided against, it would most likely have triggered Soviet use of those short-range nuclear weapons against the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo and at amphibious forces storming the Cuban beaches. That, in turn, would have triggered wider use of nuclear forces.

In our latest Nuclear Notebook – The Cuban Missile Crisis: a nuclear order of battle, October and November 1962 – we outline the nuclear order of battle that the United States and the Soviet Union had at their disposal. At the peak of the crisis, the United States had some 3,500 nuclear weapons ready to use on command, while the Soviet Union had perhaps 300-500.

The Cuban Missile Crisis order of battle of useable weapons represented only a small portion of the total inventories of nuclear warheads the United States and Russia possessed at the time. Illustrating its enormous numerical nuclear superiority, the U.S. nuclear stockpile in 1962 included more than 25,500 warheads (mostly for battlefield weapons). The Soviet Union had about 3,350.

For all the lessons the Cuban Missile Crisis taught the world about nuclear dangers, it also left some enduring legacies and challenges that are still confronting the world today. Among other things, the crisis fueled a build-up of quick-reaction nuclear weapons that could more effectively hold a risk the other side’s nuclear forces in a wider range of different strike scenarios.

Today, 50 years later and more than 20 years after the Cold War ended, the United States and Russia still have more than 10,000 nuclear weapons combined. Of those, an estimated 1,800 nuclear warheads are on alert on top of long-range ballistic missiles, ready to be launched on short notice to inflict unimaginable devastation on each other. The best way to honor the Cuban Missile Crisis would be to finally end that legacy and take nuclear weapons off alert.

Nuclear Notebook: The Cuban Missile Crisis: A nuclear order of battle, October and November 1962

NATO: Nuclear Transparency Begins At Home

|

| What’s wrong with this picture? Despite NATO’s call for greater nuclear transparency, old-fashioned nuclear secrecy prevents media access to the Nuclear Planning Group. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Less than six months after NATO’s Deterrence and Defense Posture Review (DDPR) adopted at the Chicago Summit called for greater transparency of non-strategic nuclear force postures in Europe, the agenda for the NATO defense minister get-together in Brussels this week listed the Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) meeting with the usual constraint: “no media opportunity.”

Why should the news media not have access to the NPG meeting just like they have access to other meetings discussing NATO security issues? After all, the high stakes that justified nuclear secrecy in the past disappeared with the demise of the Soviet Union, no urgent military mission is (publicly) attributed to the remaining nearly 200 U.S. nuclear bombs left in Europe, and NATO now officially advocates greater nuclear transparency.

Whatever the reason, the “no media opportunity” is symbolic of the old-fashioned secrecy that continues to constrain NATO nuclear policy discussions. The nuclear planners are insulated deep within the alliance with little or no public scrutiny. Even for NATO officials, tradition, past political statements, and turf can make it difficult to ascertain and question the rationales behind the nuclear posture.

The DDPR determined “that the Alliance’s nuclear force posture currently meets the criteria for an effective deterrence and defense posture.” The reasons for that conclusion remain elusive and the news media should have access to the NPG meeting to ask the questions. Not least because the conclusion is now resulting in significant modernization of NATO’s nuclear forces at considerable cost to the Alliance and some of its member countries. Another potential cost is how it will affect relations with Russia.

If NATO wants to increase nuclear transparency, it should and could break with old-fashioned nuclear secrecy and disclose the broad outlines of its non-strategic nuclear deployment in Europe. It is already widely known and NATO’s nuclear members are already transparent about the broad outlines of their strategic nuclear forces – those that unlike the non-strategic weapons in Europe are actually tasked to provide the ultimate security guarantee to the Allies.

Rather than limiting nuclear transparency efforts to prolonged negotiations for what’s likely to be small incremental steps that essentially surrender the agenda to hardliners in Moscow, unilateral disclosure of NATO’s non-strategic posture would jump-start the process, put pressure on Russia to follow suit, and be consistent with the already considerable transparency of NATO’s strategic forces.

See also: Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons, FAS, May 2012.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

DOD: Strategic Stability Not Threatened Even by Greater Russian Nuclear Forces

A Department of Defense (DOD) report on Russian nuclear forces, conducted in coordination with the Director of National Intelligence and sent to Congress in May 2012, concludes that even the most worst-case scenario of a Russian surprise disarming first strike against the United States would have “little to no effect” on the U.S. ability to retaliate with a devastating strike against Russia.

I know, even thinking about scenarios such as this sounds like an echo from the Cold War, but the Obama administration has actually come under attack from some for considering further reductions of U.S. nuclear forces when Russia and others are modernizing their forces. The point would be, presumably, that reducing while others are modernizing would somehow give them an advantage over the United States.

But the DOD report concludes that Russia “would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty” (emphasis added).

The conclusions are important because the report come after Vladimir Putin earlier this year announced plans to produce “over 400” new nuclear missiles during the next decade. Putin’s plan follows the Obama administration’s plan to spend more than $200 billion over the next decade to modernize U.S. strategic forces and weapons factories.

The conclusions may also hint at some of the findings of the Obama administration’s ongoing (but delayed and secret) review of U.S. nuclear targeting policy.

No Effects on Strategic Stability

The DOD report – Report on the Strategic Nuclear Forces of the Russian Federation Pursuant to Section 1240 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 – was obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. It describes the U.S. intelligence community’s projection for the likely development of Russian nuclear forces through 2017 and 2022, the timelines of the New START Treaty, and possible implications for U.S. national security and strategic stability.

Much of the report’s content was deleted before release – including general and widely reported factual information about Russian nuclear weapons systems that is not classified. But the important concluding section that describes the effects of possible shifts in the number and composition of Russian nuclear forces on strategic stability was released in its entirety.

|

| As long as a sufficient number of U.S. SSBNs are at sea, strategic stability is intact even with significantly greater Russian nuclear forces, the DOD says. |

.

The section “Effects on Strategic Stability” begins by defining that stability in the strategic nuclear relationship between the United States and the Russian Federation depends upon the assured capability of each side to deliver a sufficient number of nuclear warheads to inflict unacceptable damage on the other side, even with an opponent attempting a disarming first strike.

Consequently, the report concludes, “the only Russian shift in its nuclear forces that could undermine the basic framework of mutual deterrence that exists between the United States and the Russian Federation is a scenario that enables Russia to deny the United States the assured ability to respond against a substantial number of highly valued Russian targets following a Russian attempt at a disarming first strike” (emphasis added). The DOD concludes that such a first strike scenario “will most likely not occur.”

But even if it did and Russia deployed additional strategic warheads to conduct a disarming first strike, even significantly above the New START Treaty limits, DOD concludes that it “would have little to no effects on the U.S. assured second-strike capabilities that underwrite our strategic deterrence posture” (emphasis added).

In fact, the DOD report states, the “Russian Federation…would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty, primarily because of the inherent survivability of the planned U.S. Strategic force structure, particularly the OHIO-class ballistic missile submarines, a number of which are at sea at any given time.” (more…)

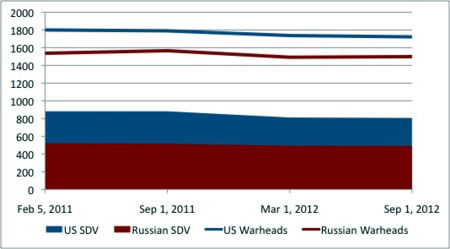

New START Data Released: Nuclear Flatlining

|

| Reductions under the New START Treaty have gotten off to a very slow start |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

More than a year and a half after the New START Treaty between the United States and Russia entered into force on January 5, 2011, one thing is clear: they are not in a hurry to reduce their nuclear forces.

Earlier today the fourth batch of so-called aggregate data was released by the U.S. State Department. It shows that the United States and Russia since January 5, 2011, have reduced their accountable deployed strategic delivery vehicles by 76 and 30, respectively. Parts of those numbers are fluctuations due to delivery platforms entering or leaving maintenance. The U.S. number obscures the fact that it involves destruction of some of three dozen old B-52G bombers that still count as deployed even though they were retired two decades ago. The Russian number obscures replacement of older missiles with new ones on a less than one-for-one basis.

During the same period, the United States and Russia have reduced their number of accountable deployed strategic warheads by 78 and 38, respectively. Much of these numbers are fluctuations due to delivery platform maintenance and it is not clear that either country has made any explicit warhead reductions yet under the treaty. In any case, 38-78 warheads don’t amount to much out of the approximately 5,000 nuclear warheads the two countries retain in each of their respective nuclear stockpiles.

With 1,499 accountable warheads on 491 deployed strategic delivery vehicles, Russia is already well below the treaty limit and is only required to scrap 84 non-deployed delivery vehicles before the treaty enters into effect in six years on February 5, 2018.

The United States is well above the Russian force level, with 1,722 accountable warheads on 806 deployed strategic delivery vehicles. Over the next six years, it will have to remove 96 deployed delivery vehicles with 172 accountable warheads, and scrap 234 non-deployed platforms.

The U.S. posture appears even more bloated when considering that the Pentagon retains a large reserve of non-deployed warheads intended to increase the loading on the missiles in a crisis.

Russia does not have such an upload capacity. And even President Putin’s promised increased missile production over the next decade will not be able to offset the expected continued decline in the Russian triad that will result form the retirement of four old ICBM and SLBM systems over the next decade-plus.

This nuclear force structure asymmetry must be addressed in the next round of U.S.-Russian strategic nuclear talks. But even before such talks get underway, reductions can and should be made. There is simply no reason for the Pentagon to stretch reductions of excess nuclear forces through 2017. Forces slated for retirement should be removed from service now and the reserve of upload warheads should be trimmed. Doing so is good planning. Not only is it expensive (and stupid) to keep more nuclear forces than needed. But a bloated force structure provides unhelpful justification for those in the Russian establishment who argue for increasing missile production and deploying new missiles.

See previous analysis of New START data:

1. Second Batch of New START Data Released

2. US Releases Full New START Data

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Event: Conference on Using Satellite Imagery to Monitor Nuclear Forces and Proliferators

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Earlier today we convened an exciting conference on use of commercials satellite imagery and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to monitor nuclear forces and proliferators around the world. I was fortunate to have two brilliant users of this technology with me on the panel:

- Tamara Patton, a Graduate Research Assistant at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, who described her pioneering work to use freeware to creating 3D images of uranium enrichment facilities and plutonium production reactors in Pakistan and North Korea. Her briefing is available here.

- Matthew McKinzie, a Senior Scientists with the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Nuclear Program and Lands and Wildlife Program, who has spearheaded non-governmental use of GIS technology since commercial satellite imagery first became widely available. His presentation is available here.

- My presentation focused on using satellite imagery and Freedom of Information Act requests to monitor Chinese and Russian nuclear force developments, an effort that is becoming more important as the United States is decreasing its release of information about those countries. My briefing slides are here.

In all of the work profiled by these presentations, the analysts relied on the unique Google Earth and the generous contribution of high-resolution satellite imagery by DigitalGlobe and GeoEye.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Report: US and Russian Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

|

| A new report describes U.S. and Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A new report estimates that Russia and the United States combined have a total of roughly 2,800 nuclear warheads assigned to their non-strategic nuclear forces. Several thousands more have been retired and are awaiting dismantlement.

The report comes shortly before the NATO Summit in Chicago on 20-21 May, where the alliance is expected to approve the conclusions of a year-long Deterrence and Defense Posture Review that will, among other things, determine the “appropriate mix” of nuclear and non-nuclear forces in Europe. It marks the 20-year anniversary of the Presidential Unilateral Initiatives in the early 1990s that resulted in sweeping reductions of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

Twenty years later, the new report Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons estimates that U.S. and Russian non-strategic nuclear forces are deployed at nearly 100 bases across Russia, Europe and the United States. The nuclear warheads assigned to these forces are in central storage, except nearly 200 bombs that the U.S. Air Force forward-deploys in almost 90 underground vaults inside aircraft shelters at six bases in five European countries.

The report concludes that excessive and outdated secrecy about non-strategic nuclear weapons inventories, characteristics, locations, missions and dismantlements have created unnecessary and counterproductive uncertainty, suspicion and worst-case assumptions that undermine relations between Russia and NATO.

Russia and the United States and NATO can and should increase transparency of their non-strategic nuclear forces by disclosing overall numbers, storage locations, delivery vehicles, and how much of their total inventories have been retired and are awaiting dismantlement.

The report concludes that unilateral reductions have been, by far, the most effective means to reducing the number and role of non-strategic nuclear weapons. Yet now the two sides appear to be holding on to the remaining weapons to have something to bargain with in a future treaty to reduce non-strategic nuclear weapons.

NATO has decided that any further reductions in U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe must take into account the larger Russian arsenal, and Russia has announced that it will not discuss reductions in its non-strategic nuclear forces unless the U.S. withdraws its non-strategic nuclear bombs from Europe. Combined, these positions appear to obstruct reductions rather facilitate reductions. Russian reductions should be a goal, not a precondition, for further NATO reductions.

Download the full report here: /_docs/Non_Strategic_Nuclear_Weapons.pdf

Slides from briefing at U.S. Senate are here: /programs/ssp/nukes/publications1/Brief2012_TacNukes.pdf

See also our Nuclear Notebooks on the total nuclear arsenals of Russia and the United States.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

On May 20-21, 28 NATO member countries will convene in Chicago to approve the conclusions of a year-long Deterrence and Defense Posture Review (DDPR). Among other issues, the review will determine the number and role of the U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons deployed in Europe and how NATO might work to reduce its nuclear posture as well as Russia’s inventory of such weapons in the future.

Lack of transparency fuels mistrust and worst-case assumptions and the concerns some eastern NATO countries have about Russia have been used to prevent a withdrawal of the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe. The DDPR is expected to endorse the current deployment in Europe.

A new FAS report (PDF) concludes that non-strategic nuclear weapons are neither the reason nor the solution for Europe’s security issues today but that lack of political leadership has allowed bureaucrats to give these weapons a legitimacy they don’t possess and shouldn’t have.

New Nuclear Notebook: Russian Nuclear Forces 2012

|

| More than two-thirds of Russia’s current ICBM force will be retired over the next 10 years, a reduction that will only partly be offset by deployment of new road-mobile RS-24 Yars (SS-27 Mod 2) ICBMs such as this one near Teykovo northeast of Moscow. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russia is planning to retire more than two-thirds of its current arsenal of nuclear land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles by the early 2020a. That includes some of the most iconic examples of the Soviet threat against the United States: SS-18 Satan, SS-19 Stiletto, and the world’s first road-mobile ICBM, the SS-25.

The plan coincides with the implementation of the New START treaty but significantly exceeds the reductions required by the treaty.

During the same period, Russia plans to deploy significant numbers of new missiles, but the production will not be sufficient to offset the retirement of old missiles. As a result, the size of Russia’s ICBM force is likely to decline over the next decade – with or without a new nuclear arms control treaty.

This and much more is described in our latest Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

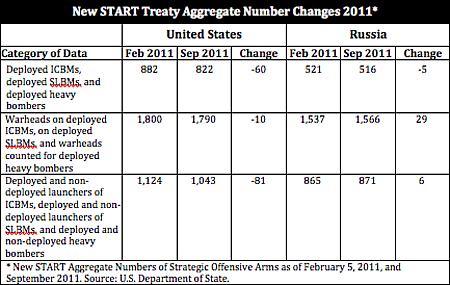

New START Data: Modest Reductions and Decreased Transparency

|

| New START aggregate numbers have been published by the United States and Russia. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The latest New START treaty aggregate numbers of strategic arms, which was quietly released by the State Department earlier last week, shows modest reductions and important changes in U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear forces.

Most surprisingly, the data shows that Russia has increased its number of deployed strategic nuclear warheads and is now again above the New START limit.

Because of the limited format of the released aggregate numbers, however, the changes are not explained or apparent. As a result, though not yet one year old, the New START treaty is already beginning to increase uncertainty about the status of U.S. and Russian nuclear forces.

Overall Changes

Combined, the data shows that the United States and Russia as of September 2011 deployed 3,356 nuclear warheads on 1,338 strategic delivery vehicles, down from 3,337 warheads on 1,403 delivery vehicles in February 2011.

A modest combined reduction of 65 delivery vehicles in seven months, but an increase of 19 warheads; apparently they two nuclear superpowers are not in a hurry to reduce.

|

| The New START aggregate data shows modest reductions in strategic delivery vehicles and a Russian increase of deployed strategic warheads. |

.

The aggregate numbers not include thousands of additional strategic and non-strategic warheads that are not counted by the treaty. To put things in perspective, the U.S. military stockpile includes nearly 5,000 warheads; the Russian stockpile probably about 8,000. In addition, thousands of retired, but still intact, warheads are in storage for a total combined U.S. and Russian inventory of perhaps 19,000 warheads.

Russia

Most surprising is that the New START data erases Russia’s achievement from earlier this year when its number of deployed strategic warheads temporarily dipped below the treaty limit of 1,550 warheads. According to the new data, Russia has slightly increased (by 29) the number of warheads deployed on its ballistic missiles and now stands 16 warheads above the treaty limit.

The warhead increase comes at the same time that the number of delivery vehicles has declined by five. But since the New START aggregate data – unlike the previous START treaty – does not include a breakdown of missile types, it is impossible to see where the change happened. As a result, transparency of Russia’s strategic nuclear forces is decreasing.

Part of the explanation is the deployment of additional RS-24 ICBMs, which carry three warheads each. But that’s a limited deployment that doesn’t account for all. Other parts of the puzzle include continued reduction of the single-warhead SS-25 ICBM force, the operational status of individual Delta IV SSBNs, and possibly retirement of one of the aging Delta III SSBNs.

The United States

The New START data shows that the United States only removed 10 warheads from its ballistic missiles during the previous seven months, down from 1,800 to 1,790 warheads.

The number of delivery vehicles declined by 60, from 882 to 822, a change that probably reflects the removal of nuclear-capable equipment from so-called “phantom” bombers. These bombers are counted under the treaty even though they are not actually assigned nuclear missions. The U.S. has not disclosed the number, but another 24, or so, “phantom” bombers probably need to be denuclearized. Stripping these aircraft of their leftover equipment reduces the number of nuclear delivery vehicles counted by the treaty, although it doesn’t actually reduce the nuclear force.

Later this decade will come a gradual reduction of the number of SLBMs deployed on SSBNs from 288 to 240. Likewise, if the bomber force is retained, the ICBM force might be reduced to 400 missiles from 450 today.

Conclusions

The New START data shows that Russia and the United States have gotten off to a slow start and excessive nuclear secrecy is reducing the international community’s ability to monitor and analyze the changes.

Russia essentially has seven and half years to offload 16 warheads from its force to be in compliance with New START by 2018. Not an impressive arms control standard. Instead, the task for Russian planners will be how to phase out old missiles and phase in new missiles. There will be no real constraint on the Russian force.

|

| The United States ICBM force could be a big as Russia’s entire triad by the mid-2020s. |

The new data underscores the substantial lead the United States has over Russia in strategic nuclear delivery vehicles. Even as Russia deploys the RS-24 ICBM and Bulava SLBM in the coming years, the gradual retirement of the SS-18, SS-19, SS-25 and SS-N-18 could reduce the total number of delivery vehicles to perhaps 400 by the time the New START treaty enters into force in 2018.

In contrast, under current plans, the United States intends to retain 700 strategic delivery vehicles by 2018. Without additional unilateral reductions, the United States could end up with 50 percent more strategic delivery vehicles than Russia in its triad by the turn of the decade. Indeed, the U.S. ICBM force alone could at that time include as many delivery vehicles as the entire Russian triad!

The U.S. force will retain a huge upload capability with several thousand non-deployed nuclear warheads that can double the number of warheads on deployed ballistic missiles if necessary. Russia’s ballistic missile force, which is already loaded to capacity, does not have such an upload capability.

This disparity creates fear of strategic instability and is fueling worst-case planning in Russia to deploy a new “heavy” ICBM later this decade.

To prevent a deepening of this trend, the Obama administration’s ongoing nuclear targeting review (see also forthcoming article in Arms Control Today) must significantly reduce the excessive nuclear posture currently planned under New START.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

A Nuclear- Free Mirage

Charles P. Blair, Senior Fellow on State and Non-State Threats, interviewed Federation of American Scientists’ Senior Fellow for Nuclear Policy Dr. Robert Standish Norris. The report takes a deeper look at the nuclear policies of the Obama administration—polices that Dr. Norris terms “radical” with regard to their vision of a nuclear weapon free world.

20th Anniversary of START

July 31st is the 20-year anniversary of signing of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) between the United States and the Soviet Union. The treaty, also known as START I, marked the beginning of a treaty-based reduction of U.S. and Soviet (later Russian) strategic nuclear forces after the end of the Cold War.

START I required each country to limit its number of accountable strategic delivery vehicles (ballistic missiles and long-range bombers) to no more than 1,600 with no more than 6,000 accountable warheads. The treaty came with a unique on-site inspection regime where inspectors from the two countries would inspect each other’s declared force levels. Thousands of other warheads were not affected and the treaty did not require destruction of a single nuclear warhead. START I entered into effect on December 5th, 2001, and expired on December 4, 2009.

Twenty years after the signing of START I, the United States and Russia are still in the drawdown phase of their strategic nuclear forces: START II followed in 1993, limiting the force levels to 3,500 accountable warheads by 2007 with no multiple warheads on land-based missiles; START II was never ratified by the U.S. Senate but surpassed by the Moscow Treaty in 2002, limiting the number of operationally deployed strategic warheads to 2,200 by 2012; The Moscow Treaty was replaced by the New START treaty signed in 2010, which limits the number of accountable strategic warheads to 1,550 on 700 deployed ballistic missiles and long-range bombers by 2018. Like its predecessors, New START does not limit thousands of non-deployed and non-strategic nuclear warheads and does not require destruction of a single warhead.

The Obama administration has stated that the next treaty must also place limits on non-deployed and non-strategic nuclear warheads.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.