Study Calls for New U.S. Nuclear Weapons Targeting Policy

|

| Click on image for PDF-version of full report. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Federation of American Scientists and Natural Resources Defense Council today published a study that calls for fundamental changes in the way the United States military plans for using nuclear weapons.

The study From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence: A New Nuclear Policy on the Path Toward Eliminating Nuclear Weapons recommends abandoning the decades-old “counterforce” doctrine and replacing it with a new and much less ambitious targeting policy the authors call Minimal Deterrence. [Update: see Washington Post – Report Urges Updating of Nuclear Weapons Policy]

Global Security Newswire reported last week that Department of Defense officials have concluded that significant reductions to the nuclear arsenal cannot be made unless President Barack Obama scales back the nation’s strategic war plan. The FAS/NRDC report presents a plan for how to do that.

The last time outdated nuclear guidance stood in the way of nuclear cuts was in 1997, when then President Clinton had to change President Reagan’s 17-year old guidance to enable U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) to go to the START-III force level that the Bush administration subsequently adopted as the Moscow Treaty force level. The series of STRATCOM force structure studies examining lower force levels is described in The Matrix of Deterrence.

Resources: Full Report | US Nuclear Forces 2009 | United States Reaches Moscow Treaty Warhead Limit Early | Press Conference Video

Russian Tactical Nuclear Weapons

|

| New low-yield nuclear warheads for cruise missiles on Russia’s submarines?. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Two recent news reports have drawn the attention to Russia’s tactical nuclear weapons. Earlier this week, RIA Novosti quoted Vice Admiral Oleg Burtsev, deputy head of the Russian Navy General Staff, saying that the role of tactical nuclear weapons on submarines “will play a key role in the future,” that their range and precision are gradually increasing, and that Russia “can install low-yield warheads on existing cruise missiles” with high-yield warheads.

This morning an editorial in the New York Times advocated withdrawing the “200 to 300” U.S. tactical nuclear bombs deployed in Europe “to make it much easier to challenge Russia to reduce its stockpile of at least 3,000 short-range weapons.”

Both reports compel – each in their own way – the Obama administration to address the issue of tactical nuclear weapons.

The Russian Inventory

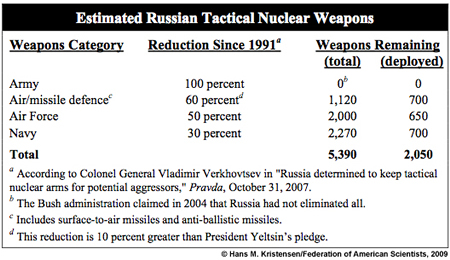

Like the United States, Russia doesn’t say much about the status of its tactical nuclear weapons. The little we have to go by is based on what the Soviet Union used to have and how much Russian officials have said they have cut since then.

Unofficial estimates set the Soviet inventory of tactical nuclear weapons at roughly 15,000 in mid-1991. In response to unilateral cuts announced by the United States in late 1991 and early 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin pledged in 1992 that production of warheads for ground-launched tactical missiles, artillery shells, and mines had stopped and that all such warheads would be eliminated. He also pledged that Russia would dispose of half of all airborne and surface-to-air warheads, as well as one-third of all naval warheads.

In 2004, the Russian Foreign Ministry stated that “more than 50 percent” of these warhead types have been “liquidated.” And in September 2007, Defense Ministry official Colonel-General Vladimir Verkhovtsev gave a status report of these reductions that appeared to go beyond President Yeltsin’s pledge.

Based on this, Robert Norris and I make the following cautious estimate (to be published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in late April) of the current Russian inventory of tactical nuclear weapons:

|

| Estimate from forthcoming Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. |

.

Based on the number of available nuclear-capable delivery platforms, we estimate that nearly two-thirds of these warheads are in reserve or awaiting dismantlement. The remaining approximately 2,080 warheads are operational for delivery by anti-ballistic missiles, air-defence missiles, tactical aircraft, and naval cruise missiles, depth bombs, and torpedoes. The Navy’s tactical nuclear weapons are not deployed at sea under normal circumstances but stored on land.

The Other Nuclear Powers

The United States retains a small inventory of perhaps 500 active tactical nuclear weapons. This includes an estimated 400 bombs (including 200 in Europe) and 100 Tomahawk cruise missiles (all on land). Others, perhaps 700, are in inactive storage.

France also has 60 tactical-range cruise missiles, including some on its aircraft carrier, although it calls them strategic weapons.

The United Kingdom has completely eliminated its tactical nuclear weapons, although it said until a couple of years ago that some of its strategic Trident missiles had a “sub-strategic” mission.

Information about possible Chinese tactical nuclear weapons is vague and contradictory, but might include some gravity bombs.

India, Pakistan, and Israel have some nuclear weapons that could be considered tactical (gravity bombs for fighter-bombers and, in the case of India and Pakistan, short-range ballistic missiles), but all are normally considered strategic.

| Russian Nuclear-Capable Cruise Missile Launch |

|

| A nuclear-capable SS-N-19 Shipwreck cruise missile is launched from a Kirov-class nuclear-powered guided missile cruiser. The ship is equipped with 20 launchers for the SS-N-19 missile, which can carry a 500-kiloton warhead. Other tactical nuclear weapon systems include the SS-N-16 anti-submarine rocket, and the SA-N-6 anti-air missile. |

.

Implications and Issues

Whether Vice Admiral Burtsev’s statement is more than boasting remains to be seen, but it is a timely reminder to the Obama administration of the need to develop a plan for how to tackle the tactical nuclear weapons.

Russia’s nuclear posture is now approaching a situation where there are more tactical nuclear weapons in the inventory than strategic weapons. And NATO’s remnant of the Cold War tactical nuclear posture in Europe seems stuck in the mud of nuclear dogma and bureaucratic inaction.

None of these tactical nuclear weapons are limited or monitored by any arms control agreements, and – for all the worries about terrorists stealing nuclear weapons – are the most easy to run away with.

In April, NATO is widely expected to kick off a (long-overdue) review of its Strategic Concept from 1999. It would be a mistake to leave the initiative on what to do with the tactical nuclear weapons to the NATO bureaucrats. The vision must come from the top and President Obama needs to articulate what it is soon.

U.S. Strategic Submarine Patrols Continue at Near Cold War Tempo

|

| U.S. ballistic missile submarines conducted 31 nuclear deterrent patrols in 2008 at an operational tempo comparable to that of the Cold War. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen [updated]

The U.S. fleet of 14 nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines conducted 31 nuclear deterrent patrols in 2008 at an operational tempo comparable to during the Cold War.

The new patrol information, which was obtained from the U.S. Navy under the Freedom of Information Act, coincides with the completion on February 11, 2009, of the 1,000th deterrent patrol by an Ohio-class submarine since 1982.

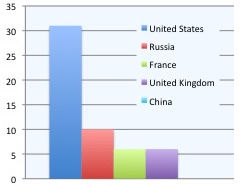

The information shows that the United States conducts more nuclear deterrent patrols each year than Russia, France, United Kingdom and China combined.

Patrols by the Number

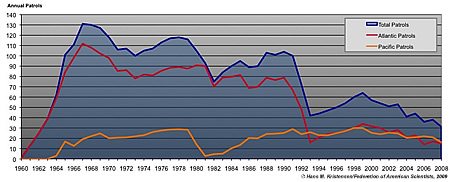

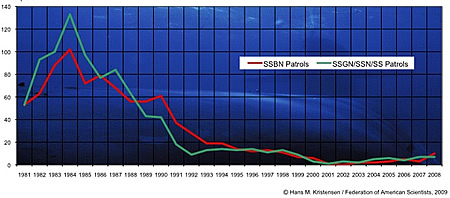

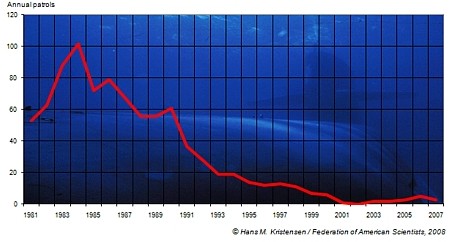

The 31 patrols conducted in 2008 top a 48-year history of continuous deterrent patrols. Since the USS George Washington (SSBN-598) departed Charleston, S.C., on the first nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) patrol on November 15, 1960, 59 SSBNs have conducted 3,814 patrols through 2008 (see Figure 1).

.

The annual number of patrols has fluctuated considerably over the years, peaking at 131 patrols in 1967. Declines occurred mainly due to retirement of SSBNs rather than changes in the mission. The retirement of the early classes of SSBNs in 1979-1981 almost eliminated patrols in the Pacific, but the new Ohio-class gradually rebuilt the posture. The stand-down of Poseidon SSBNs in October 1991 and the retirement of all non-Ohio-class SSBNs by 1993 reduced Atlantic patrols by nearly 60 percent. The patrols increased again in the second half of the 1990s and more Ohio-class SSBNs were added to the fleet, but started dropping from 2000 as four Ohio-class SSBNs were withdrawn from nuclear missions and four others underwent lengthy backfits from the Trident I C4 to the Trident II D5 Trident missile.

|

Figure 2: |

|

|

The United States conducts more SSBN patrols than all other nuclear powers combined. China’s SSBNs have yet to conduct a deterrent patrol. |

During the Cold War standoff with the Soviet Union, the vast majority of patrols were done in the Atlantic Ocean. Since the early 1990s, patrols in the Atlantic have plummeted and the SSBN force been concentrated on the west coast. The majority of U.S. SSBN patrols today occur in the Pacific.

The current number of patrols is significantly greater than the patrol levels of other countries with sea-based nuclear weapon systems. In fact, the U.S. navy conducted three times the number of SSBN patrols that the Russian navy did in 2008, and more patrols than Russia, France, Britain and China combined (see figure 2).

High Operational Tempo

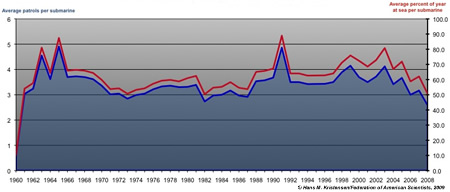

Although the total annual number of SSBN patrols has decreased significantly since the end of the Cold War, the operational tempo of each submarine has not. Each Ohio-class SSBNs today conducts about the same number of patrols per year as during the Cold War, but the duration of each patrol has increased, with each submarine spending approximately 50-60 percent of its time on patrol (see Figure 3).

.

The high operational tempo is made possibly by each SSBN having two crews, Blue and Gold. Each time a submarine returns from a patrol, the other crew takes over, spends a few weeks repairing and replenishing the boat, and takes the SSBN out for its next patrol.

The data also reveals a couple of interesting spikes of increased patrols in 1963/1965 and 1991. The reasons for this increased activity is not known but the periods coincide with the Cuban missile crisis and the failed coup attempt in the final days of the Soviet Union in 1991.

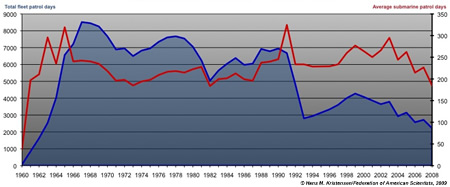

Another way to examine the data is to see how may patrol days each submarine and the fleet accumulate each year. During the Cold War the larger submarine fleet averaged approximately 6,000 patrol days each year, with a peak of 8,515 patrol days in 1967. That performance declined to an average of 3,400 days in the post-Cold War era as the size of the SSBN fleet was reduced. With the removal of four SSBNs from nuclear operations and four others undergoing lengthy missile backfits, the fleet’s total patrol days has now dropped to a little over 2,200 (see figure 4).

.

Yet total patrol day numbers can be deceiving because they can obscure how each submarine is doing. Because the Ohio-class SSBN design was optimized for lengthy deterrent patrols, the average number of days each submarine spends on patrol has been higher in the post-Cold War period than during the Cold War itself. Patrols can be shortened by technical problems, but many Ohio-class submarines today stay on patrol for more than 80 days. Last year, the USS Maine (SSBN-741) conducted a 98-day patrol in the Pacific.

What is a Deterrent Patrol?

An SSBN deterrent patrol is an extended operational deployment during part of which the submarine covers its assigned target package in support of the strategic war plan. Each Ohio-class patrol typically lasts 60-90 days, but one submarine in late 2008 conducted an extended patrol of 98 day and patrols have occasionally exceeded 100 days. Occasionally a patrol is cut short by technical problems, in which case another SSBN can be deployed on short notice. As a result, patrols today in average last about 72 days.

Being on patrol does not mean the submarine is continuously submerged on-station and holding targets at risk. In fact, when the submarine is not on Hard Alert holding targets at risk in Russia, China, or regional states, much of the patrol time is spent on cruising between homeport, patrol areas, exercising with other naval forces, undergoing inspections and certifications, performing Weapon System Readiness Tests (WSRTs), conducting retargeting exercises, and Command and Control exercises.

Another activity involves so-called SCOOP exercises (SSBN Continuity of Operations Program) where the SSBN will practice replenishment or refit in forward ports in case the homeport is annihilated in wartime. In the Pacific, the SCOOP ports include Pearl Harbor, Hawaii (see Figure 5), Guam, Seaward, Alaska, Astoria, Oregon, and San Diego, California. In the Atlantic they include Port Canaveral and Mayport, Florida, Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico, and Halifax, Canada. The SSBN may even return to its homeport and redeploy a day or two later on the same patrol.

|

Figure 5: |

|

| USS Henry M. Jackson (SSBN-730) loading fresh fruit in Pearl Harbor during a SCOOP visit to Hawaii in March 2008 on its first patrol after a four-year overhaul where it was refueled and modernized to carry the Trident II D5 ballistic missile. |

.

Although patrols normally end at the base where they started, this is not always the case. An SSBN that departs Naval Submarine Base Bangor, Washington, might go on-station for several weeks in alert operational areas, conduct various training and exercises, and then arrive at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. After a brief port visit and replenishment the submarine typically resumes its patrol and eventually returns to Bangor. But sometimes the patrol will end in Hawaii, a new crew be flown in to replace the old, and the submarine undergo refit at the forward location as part of a SCOOP exercise. The SSBN then departs Hawaii on a new patrol, goes on-station in alert operational areas, conducts more exercises and inspections, and eventually returns to Bangor where the new patrol ends.

This type of broken up patrol where the submarine is allowed to do more than on-station operations is sometimes described as “modified alert” and said to be different from the Cold War. But SSBNs have never been on-station all the time, with most deployed submarines being in transit between on-station alert areas and other non-alert operations. In fact, “modified alert” patrols date back to the early 1970s.

Of the 14 SSBNs currently in the fleet, two are normally in overhaul at any given time. Of the remaining operational 12 submarines, 8-9 are deployed on patrol at any given time. Four of these (two in each ocean) are on “Hard Alert” while the 4-5 non-alert SSBNs can be brought to alert level within a relatively short time if necessary. One to three SSBNs are in refit at the home base in preparation for their next patrol.

The SSBNs on Hard Alert continuously hold at risk facilities in Russia, China and regional states with an estimated 384 nuclear warheads on 96 Trident II D5 missiles that can be launched within “a few minutes” after receiving the launch order. The targets in the “target packages” are selected based on the taskings of the strategic war plan, known today as Operations Plan (OPLAN) 8010.

What is the Mission?

But why, nearly two decades after the Cold War ended, are 28 crews ordered to sail 14 SSBNs with more than 1,000 nuclear warheads on 30-plus patrols each year at an operational tempo comparable to that of the Cold War?

The official line is, as stated last month by Secretary of the Navy Donald Winter during the celebration of the 1,000th Ohio-class deterrent patrol, that “the ability of our Trident fleet to [be ready to launch its missiles] 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year, has promoted the interests of peace and freedom around the world….Since the beginning of the nuclear age, the world has seen a drastic reduction in wartime deaths.”

|

Figure 6: |

|

|

STRATCOM commander General Kevin Chilton (left) and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Gary Roughead. General Chilton says SSBNs deter not only nuclear conflict but “conflict in general” and are “as equally important today, as they ever were during the height of the Cold War.” |

The warfighters add more nuances, including Commander Jeff Grimes of the Trident submarine USS Maryland (SSBN-738) who at the start of a recent deterrent patrol explained it to Navy Times: “There are nuclear weapons in the world today. Many nations have them. Proliferation is possible in the growing technologies societies have. The power of the deterrent is the knowledge that the capability exists in the hands of controlled people. So on a global scale, deterrence is showing how it’s working every day. We haven’t had a global, world war, in a long time,” he said. “Intelligence is different, the threats are different, so we do adjust the planning and contingencies for strategic operations continually to face the threats that may or may not be seen….We’re there on the front line, ready to go,” Grimes declared.

STRATCOM commander General Kevin Chilton, who in a war would advise the president on which nuclear strike options to use, said recently that although some people thought the Trident mission would end with the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, the SSBNs “are as equally important today, as they ever were during the height of the Cold War….The application of deterrence can actually be more complicated in the 21st century, but some fundamentals don’t change,” he said and added: “And it is not just to deter nuclear conflict. These forces have served to deter conflict in general, writ large, since they’ve been fielded.”

These are strong and diverse claims that are also made in some of the command histories that each SSBN produces. Some of them state that the mission is to “maintain world peace,” which has certainly not been the case in the post-Cold War era. Others describe the mission as “providing strategic deterrence to prevent nuclear war” (my emphasis), which sounds more credible. But even in that case, can we really tell whether it is the SSBNs that prevent nuclear war and not the ICBMs or bombers?

The enormous differences between maintaining world peace, preventing wars, and preventing nuclear war demand that officials articulate the SSBN mission much more clearly. To that end, it would be good to hear why it takes 12 operational SSBNs with more than 1,100 nuclear warheads on 30-plus patrols per year to deter nuclear attack against the United States, but only three operational SSBNs with less than 160 warheads on six patrols per year to safeguard the United Kingdom.

|

Figure 7: |

|

| USS Maryland (SSBN-738) departs Kings Bay on February 15, 2009, for its 53rd deterrent patrol in the Atlantic Ocean to prevent nuclear war, prevent world war, deter conflict, maintain world peace, promote the interests of peace of freedom, deter proliferators, in a mission that remains“equally important…as during the height of the Cold War,” depending on who is describing it. |

.

Last year Russia’s SSBNs returned to sea at a level not seen in a decade and it plans to build eight new Borey-class SSBNs with new multi-warhead missiles. France is completing its fourth Triomphant-class SSBNs also with a new multi-warhead missile, and Britain has announced plans to build four new SSBNs. China is building 3-5 new Jin-class SSBNs with 8000-kilometer missiles, and India is said to be working on an SSBN as well. The U.S. Navy has also begun design work on its next ballistic missile submarine to replace the Ohio-class.

In short, the nuclear powers seem to be recommitting themselves to an era of deploying large numbers of nuclear weapons in the oceans. Most people tend to view sea-based nuclear weapons as the most legitimate leg of the Triad. Yet of all strategic nuclear weapons, sea-based ballistic missiles are the most difficult to track, the most problematic to communicate with in a crisis, the hardest to verify in an arms control agreement, and the only ones that can sneak up on an adversary in a surprise attack.

If the Obama administration wants to decisively move the world toward “dramatic reductions” and ultimately the elimination of nuclear weapons, then it must seek answers to these issues. In the short term, it needs to ask whether the Cold War operational tempo of U.S. SSBNs is counterproductive by sending a signal to other nuclear weapon states that triggers modernization of their forces and makes reductions harder to achieve than otherwise. In other words, what is the net impact of the SSBN patrols on U.S. national security objectives in an era of pursuing nuclear disarmament?

Addition Resources: Russian Sub Patrols | Chinese Sub Patrols

_____________________________________________________________

Russian Strategic Submarine Patrols Rebound

|

| Russian SSBN patrols tripled from 2007 to 2008. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russia sent more nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines on patrol in 2008 than in any other year since 1998, according to information obtained by Federation of American Scientists from U.S. naval intelligence.

The information shows that Russian missile submarine conducted ten patrols in 2008, compared with three in 2007 and five in 2006. In 2002, no patrols were conducted at all.

Return of Continuous Russian SSBN Patrols?

For the past ten years, Russian remaining 11 SSBNs have not maintained continuous patrols, but instead carried out occasional patrols for training purposes. Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov said in on September 11, 2006, that five SSBNs were on patrol at that time. But since that number matched the total number of patrols conducted that year, it revealed a cluster of patrols rather than a continuous at-sea presence.

The United States, France and Britain, in contrast, continuously have at least one SSBN on patrol. In the case of the United States, two-thirds of its 14 SSBNs are at sea at any given time, of which four are on alert.

.

The ten Russian patrols in 2008 raise the question whether Russia has now resumed continuous SSBN patrols. Neither the duration nor the dates of Russian SSBN patrols are known, but if they east last more than 36 days and do not overlap, then Russia could have a continuous at-sea deterrent. If the patrols cluster like in 2006, then the posture might still be sporadic.

The Voyage of Ryazan

Although not specified in the information obtained from U.S. naval intelligence, one of the Russian patrols probably was the 30-days under-ice voyage of the Delta III-class submarine Ryazan from the Northern Fleet on the Kola Peninsula in the Barents Sea to the Pacific Fleet on the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Pacific.

|

Figure 2: |

|

| One of the 10 SSBN patrols probably involved the transfer of a Delta III SSBN from the Northern Fleet to the Pacific Fleet. |

.

The voyage occurred shortly after Ryazan completed a successful test launch of a ballistic missile – probably an SS-N-18 – from the Barents Sea on August 1, 2008. The missile type was not announced, which is unusual, but its payload flew across Northern Russia and impacted in the Kura test range on the Kamchatka Peninsula.

At end the of August, Ryazan departed the Northern Fleet and sailed submerged along Russia’s ice covered northern coast through the Bering Strait before it headed south to the ballistic missile submarine base in Vladivostok, where it arrived on September 30.

Arms Control Implications

It would be ironic – now that the Obama administration has proposed reductions in strategic nuclear forces and Kremlin seems to respond favorably – if Russian SSBNs returned to the Cold War practice of continuous deterrent patrols.

SSBNs continuously roaming the oceans are one of the last symbols of the Cold War when long-range nuclear missiles were hidden in the deep to survive a massive first strike. United States SSBNs continue a patrol rate comparable to that of the 1980s, France and Britain try to keep one or two at sea at any time – two apparently collided last month, and China and India are trying to build SSBNs fleets too.

Many still see SSBNs as purely retaliatory weapons passively hiding in the oceans. But as U.S. and Russian nuclear forces are reduced further and China and India join the SSBS club, forward deployed submerged nuclear weapons could become some of the most problematic challenges for nuclear arms control.

Chinese Submarine Patrols Doubled in 2008

|

| Chinese submarines conducted 12 patrols in 2008, the highest ever. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Chinese attack submarines sailed on more patrols in 2008 than ever before, according to information obtained by Federation of American Scientists from U.S. naval intelligence.

The information, which was declassified by U.S. naval intelligence in response to a Freedom of Information Act request from the Federation of American Scientists, shows that China’s fleet of more than 50 attack submarines conducted 12 patrols in 2008, twice the number of patrols conducted in 2007.

China’s strategic ballistic missile submarines have never conducted a deterrent patrol.

Highest Patrol Rate Ever

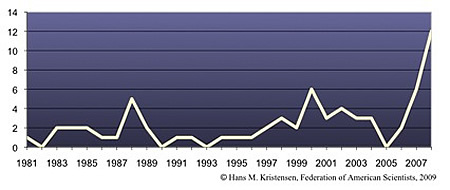

The 12 patrols conducted in 2008 constitute the highest patrol rater ever for the Chinese submarine fleet. They follow six patrols conducted in 2007, two in 2006, and zero in 2005. China has four times refrained from conducting submarine patrols since 1981, and the previous peaks were six patrols conducted in 2000 and 2007 (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1: |

|

| Chinese attack submarines conducted 12 patrols in 2008, double the number from 2007. Yet Chinese ballistic missile submarines have yet to conduct a deterrent patrol. |

.

While the increase is submarine patrols is important, it has to be seen in comparison with the size of the Chinese submarine fleet. With approximately 54 submarines, the patrol rate means that each submarine on average goes on patrol once every four and a half years. In reality, the patrols might have been carried out by only a small portion of the fleet, perhaps the most modern and capable types. A new class of nuclear-powered Shang-class (Type-093) attack submarines is replacing the aging Han-class (Type-091).

Few of the details for assessing the implications of the increased patrol rate are known, nor is it known precisely what constitutes a patrol in order for U.S. naval intelligence to count it. A request for the definition has been denied. It is assumed that a patrol in this case involves an extended voyage far enough from the submarine’s base to be different from a brief training exercise.

In comparison with other major navies, twelve patrols are not much. The patrol rate of the U.S. attack submarine fleet, which is focused on long-range patrols and probably operate regularly near the Chinese coast, is much higher with each submarine conducting at least one extended patrol per year. But the Chinese patrol rate is higher than that of the Russian navy, which in 2008 conducted only seven attack submarine patrols, the same as in 2007.

Still no SSBN Patrols

The declassified information also shows that China has yet to send one of its strategic submarines on patrol. The old Xia, China’s first SSBN, completed a multi-year overhaul in late-2007 but did not sail on patrol in 2008.

|

| Neither the Xia-class (Type-092) ballistic missile submarine (image) nor the new Jin-class (Type-094) have ever conducted a deterrent patrol. |

.

The first of China’s new Jin-class (Type-094) SSBN was spotted in February 2008 at the relatively new base on Hainan Island, where a new submarine demagnetization facility has been constructed. But the submarine did not conduct a patrol the remainder of the year. A JL-2 missile was test launched Bohai Bay in May 2008, but it is yet unclear from what platform.

Two or three more Jin-class subs are under construction at the Huludao (Bohai) Shipyard, and the Pentagon projects that up to five might be built. How these submarines will be operated as a “counter-attack” deterrent remains to be seen, but they will be starting from scratch.

Nuclear Déjà Vu At Carnegie

By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

Only one week before Barack Obama is expected to win the presidential election, Defense Secretary Robert Gates made one last pitch for the Bush administration’s nuclear policy during a speech Tuesday at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

What is the opposite of visionary? Whatever, that’s the word that best describes Mr. Gates’s speech. Had it been delivered in the mid-1990s it would not have sounded out of place. The theme was that the world is the way the world is and, not only is there little to be done about changing the world, our response pretty much has to be more of the same.

Granted, Gates’s job is to implement nuclear policy not change it but, at a time when Russia is rattling its nuclear sabers, China is modernizing its forces, some regional states either have already acquired or are pursuing nuclear weapons, and yet inspired visions of a world free of nuclear weapons are entering the political mainstream, we had hoped for some new ideas. Rather than articulating ways to turn things around, Gates’ core message seemed to be to “hedge” and hunker down for the long haul. And, while his arguments are clearer than most, this speech is yet another example of faulty logic and sloppy definitions justifying unjustifiable nuclear weapons.

They Do It So We Must Do It Too

Reductions cannot go on forever, Secretary Gates argues because there is still a mission for nuclear weapons. Using language from the Clinton Administration, he says we can reduce our arsenal but we must also “hedge” against unexpected threats. He said, “Rising and resurgent powers, rogue nations pursuing nuclear weapons, proliferation of international terrorism, all demand that we preserve this hedge. There is no way to ignore efforts by rogue states such as North Korea and Iran to develop and deploy nuclear weapons or Russian or Chinese strategic modernization programs.”

While the potential threats he lists are real and must be addressed, how do nuclear weapons address these threats? And even if there were some nuclear component to our responses, the nature of those responses would be so varied that lumping these threats together muddles the issue. A nuclear response to international terrorism? Even if, for example, al Qaeda used a nuclear weapon to attack an American city, what target would we strike back at with a nuclear weapon? The implicit argument of symmetry is unsustainable. Just as we don’t respond to roadside bombs with our own roadside bombs, nor would we respond to chemical attack with chemical weapons or biological attack with biological weapons. We might respond to nuclear attack with nuclear weapons but we should not allow this to be an unstated assumption. The reason rogue nations, let’s say Iran and North Korea, are developing nuclear weapons is not to counter our nuclear weapons but as a counter to our overwhelming conventional capability. They certainly are not making the mistake of implicitly assuming symmetry.

The near universal logical sleight of hand is to make some argument for nuclear weapons, let’s say we need them because North Korea has them, and then, when people nod in agreement that we need nuclear weapons, let slip in the assumption that this implies we need the nuclear arsenal the administration wants. Not so fast. If North Korea has one, perhaps we need two, but that does not mean we need two thousand.

It helps to clarify the typically foggy nuke-think if we remove Russia and China from the picture and ask whether the United States could justify anything near its currently planned nuclear arsenal only to deter and defeat rogue states and terrorists. Of course not. And perhaps we don’t need nuclear weapons for regional scenarios at all, given our overwhelming conventional capabilities. So those odds and ends are thrown into the pot just to scare, not to explain, and not because there is any well thought out strategy for how nuclear weapons are going to stop a terrorist attack on an American city, or why it be an appropriate response to a regional state that doesn’t have the capability to threaten the survival of the United States.

Russia is a very different case: Russian long-range nuclear forces are the only things in the world today that could destroy us as a nation and society, just as we could destroy them. While relations with Russia are not friendly, no conceivable difference between the United States and Russia justifies this mutual hostage relationship. This pointless threat to our very existence persists because of a failure of imagination typified by this speech. In this case, it is the nuclear weapons that are creating the threat, not protecting us from it.

That Ole Warhead Production Fever

Whatever the supposed justification of nuclear weapons, the primary purpose of the Secretary’s speech seemed to be to promote the Reliable Replacement Warhead or RRW but again, his argument rests on hidden (and unjustified) assumptions and, at times, misstatements of fact. The basic premise is that, without testing, we are slowly but certainly losing confidence in the reliability of our nuclear arsenal. He said, “With every adjustment, we move farther away from the original design that was successfully tested when the weapons was first fielded.”

We do? The implication is that we have no other choice, what we could do in 1990 we simply can’t reproduce today, like handing a modern-day native American a hunk of flint and asking him to chip out an arrowhead. Why should this be? With a budget of billions of dollars, we can’t duplicate parts that we could make twenty years ago? We can spend billions on the National Ignition Facility to create the world’s most powerful laser but we can’t reproduce a 1980s O-ring? The problem the Secretary describes is certainly possible and something we have to be alert to but it isn’t inevitable; we can maintain weapons within design margins as long as we want and in the past—pre-RRW—that was precisely the plan. And parts of the weapon that are not the nuclear core of the bomb can be improved and modernized and tested as much as we want.

But Mr. Gates claims that we are slowly and helplessly drifting, “So the information on which we base our annual certification of the stockpile grows increasing dated and incomplete.” This implies the Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP) has failed. We believe the Secretary is wrong. Everyone we have talked to who is familiar with the enormous effort that has gone into the SSP says that our understanding of nuclear weapons today is substantially greater than it was the day after our last nuclear test. Our knowledge of the aging of nuclear warheads is increasing faster than the warheads are aging. Early uncertainties and concerns about stability, for example, of the plutonium parts of the weapon have been resolved and the parts have been shown to be stable for many decades, if not a century or more. Our computer models are dramatically and significantly more detailed and sophisticated. In fact, one weapon designer has told us that, given a fixed budget, the best investment of your next dollar would never be in a nuclear test but in more inspections, more computer simulations, more replacement of non-nuclear components, more material tests, more frequent tritium replenishment, and so forth.

|

How Many Times Does Congress Have to Say No? |

|

| Every time the Pentagon has proposed a new nuclear warhead since the end of the Cold War, Congress has refused to fund it. Now that the RRW appears to have been whacked, what will the next proposal for a new warhead look like? |

.

Aside from the question of the reliability of current warheads, Mr. Gates argues that we still need an RRW because we need to modernize. The British, French, Russians, and Chinese are modernizing so we must too, obviously. Why? Nuclear weapons are a mature technology. There is no new science in nuclear weapons. They are powerful, efficient explosives. They are intended to blow up things and they have specific missions, which typically involve blowing up specific things. If they can accomplish these missions, what is the problem? If the technology, even the weapons, is decades, even centuries old, if they work then they work. Nuclear weapons are not fighter planes or tanks or submarines, duking it out on a battlefield with the enemy’s opposite number, so our nuclear weapons should be evaluated with regard to the targets they are expected to destroy, not anyone else’s nuclear weapons. They can destroy the targets. We’re done.

The important factor is not the warhead but the delivery vehicle that is intended to bring the warhead to the target. And the reason the United States is not producing new nuclear weapons while Russia and China do is not because they can and we can’t, or they’re ahead and we’re behind, as the Secretary indicated. Rather, the United States has not been producing new nuclear weapons because it didn’t have to – the existing ones are more than adequate – and because not producing has been seen as much more important to U.S. foreign policy objectives. And if Russian and Chinese warhead production is a problem, why not propose how to influence them to change rather than advocating that we repeat their mistake?

The final argument for the RRW is that the US must maintain a nuclear production industry and the RRW is grist for that mill. But many of the RRW technologies and capabilities were developed by the very SSP that Gates now implies is failing. Six years ago – before they came up with RRW after having failed to get permission to build the Precision Low-Yield Weapon Design (PLYWD) and the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP) – the National Nuclear Security Administration assured Congress: “We believe the life extension programs authorized by the Nuclear Weapons Council for the B61, W80, and the W76 will sufficiently exercise the design, production and certification capabilities of the weapons complex” (emphasis added). That assurance was given after the Foster Panel recommended, “developing new designs of robust, alternative warheads.” Now the claim suddenly is that the life extension programs do not sufficiently exercise the weapons complex. At least get the argument straight.

What’s Around the Corner?

We would be more sympathetic to the production argument if the fundamental minimal needs of the nuclear production industry were better thought out and justified, but what we see is an effort to maintain a slimmed down version of what we have without thinking through what we need. In fact, if maintaining the production industry is the core objective, we would have expected the administration to ask for an RRW design that doesn’t need a complex production industry, one that is extremely simple, perhaps using uranium rather than plutonium, perhaps a clunky design but one sure to work that does not require any sophisticated skills that must be maintained in standby in perpetuity.

We’re concerned that in the end Congress will accept a beefed-up life extension program – they seem to have already found a name for it: Advanced Certification Program – that will relax the restrictions for what modifications can be made to existing warheads in order to incorporate as much as the RRW concept as possible and add new capabilities if necessary. Unless the next president significantly changes the nuclear guidance for what the Pentagon is required to plan for, RRW-like proposals will likely continue to make it harder to create a national consensus on the future role of nuclear weapons. And Barack Obama has not explicitly rejected the RRW, but said he does “not support a premature decision to produce the RRW” and “will not authorize the development of new nuclear weapons and related capabilities.” Enhanced life-extended warheads could fit within such a policy.

In the end, justifying the nuclear weapons production industry is shaky because the justification for the weapons themselves is shaky, resting on assertion and Cold War momentum – as Gates’ speech illustrated – more than on rigorous assessments of missions and the security of the nation.

The Secretary’s speech was a disappointing missed opportunity. We are a bit perplexed about why he gave it and gave it now. Perhaps he is putting down a marker for a debate he expects in the next administration and Congress. We welcome that debate because we believe that, with careful attention to definition and no hidden assumptions, the arguments for nuclear weapons fade away.

Nuclear Policy Paper Embraces Clinton Era “Lead and Hedge” Strategy

By Hans M. Kristensen

The new nuclear policy paper National Security and Nuclear Weapons in the 21st Century published quietly Tuesday by the Defense and Energy Departments embraces the “lead and hedge” strategy of the first Clinton administration for how US nuclear forces and policy should evolve in the future.

Yet the “leading” is hard to find in the new paper, which seems focused on hedging.

Instead of offering different alternative options for US nuclear policy, the paper comes across as a Cold War-like threat-based analysis that draws a line in the sand against congressional calls for significant changes to US nuclear policy.

Strong Nuclear Reaffirmation

The paper presents a strong reaffirmation of an “essential and enduring” importance of nuclear weapons to US national security. Russia, China and regional “states of concern” – even terrorists and non-state actors – are listed as justifications for hedging with a nuclear arsenal “second to none” with new warheads that can adapt to changing needs.

Even within the New Triad – a concept presented by the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review as a way to decrease the role of nuclear weapons and increasing the role of conventional weapons and missile defense – the new paper states that nuclear weapons “underpin in a fundamental way these new capabilities.”

In defining the role of nuclear weapons, the paper borrows from and builds on statements, guidance and assertions about the role of nuclear weapons issued by the Clinton and Bush administrations during the past 15 years. This consensus seeking style presents a strong reaffirmation of the continued importance – even prominence – of nuclear weapons in US national security.

Threat-Based Analysis After All

Officials have argued for years that US military planning is no longer based on specific threats and that the security environment is too uncertain to predict them with certainty. But there is nothing uncertain about who the threats are in this paper, which seems to place renewed emphasis on threat-based analysis. The earlier version from 2007 did not mention Russia and China by name, but both countries and their nuclear modernizations are prominently described in the new paper.

Russia is said to have a broad nuclear modernization underway of all major weapons categories, increased emphasis on nuclear weapons in its national security policy and military doctrine, possess the largest inventory of non-strategic nuclear weapons in the world, and re-incorporated theater nuclear options into its military planning. This modernization, resumption of long-range bomber patrols, threats to target US missile defense systems in Europe with nuclear weapons, have created “considerable uncertainty” about Russia’s future course that makes it “prudent” for the US to hedge.

China is said to be the only major nuclear power that is expanding the size of its nuclear arsenal, qualitatively and quantitatively modernizing its nuclear forces, developing and deploying new classes of missiles, and upgrading older systems. The paper repeats the assessment from the 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review that “China has the greatest potential to compete militarily with the United States and field disruptive technologies that could, over time, offset traditional U.S. military advantages.” To that end, the paper indirectly points to China as having influenced the US force level planned for 2012 in “retaining a sufficient margin over countries with expanding nuclear arsenals….”

Regional “states of concern” – formerly known as rogue states – with (or developing) weapons of mass destruction are also highlighted in the paper as an enduring mission for US nuclear weapons. This broadened role for US nuclear weapons, which evolved during the 1990s and in 2003 led to incorporation of nuclear strike options into the US strategic war plan, focuses on Iran, North Korea and Syria. But the paper warns that a significant change in the “alignment among states of concern” in the future may require “adjustments to US deterrent capabilities.”

“Violent extremists and non-state actors” – commonly known as terrorists – are also listed as potential missions for US nuclear weapons. Most analysts agree that terrorists cannot or do not need to be affected by nuclear threats, so the paper instead declares that it is US policy “to hold state sponsors of terrorism accountable for the actions of their proxies.”

In addition to these potential threats, the paper describes how regional dynamics lead other nations, “such as India and Pakistan, to attach similar significance to their nuclear forces.” Israel is not mentioned in the paper.

And if all of this fails to impress, the paper also includes France and the United Kingdom to show that they have already committed themselves to extending and maintaining modern nuclear forces well into the 21st century.

These trends “clearly indicate the continued relevance of nuclear weapons, both today and in the foreseeable future,” the paper concludes. Therefore, it asserts, it is prudent that the United States maintains a viable nuclear capability that is “second to none” well into the 21st century.

Sizing a “Second to None” Nuclear Arsenal

“Second to none” means a US arsenal that is better than Russia’s arsenal. At the same time, the paper states that the criteria for sizing the US arsenal “are no longer based on the size of Russian forces and the accumulative targeting requirements for nuclear strike plans.” This has been said before and has confused many; some officials have even claimed that target plans do not affect the size of the arsenal at all. So the paper adds a lot of new information – probably the most interesting and valuable part of the paper – to clarify the situation:

| “Prior to the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review, force sizing considerations were based on target defeat criteria with the objective of rendering a nuclear-armed adversary incapable of prosecuting conflict, and terminating any conflict on terms favorable to the United States. U.S. Forces were sized to defeat all credible nuclear-armed adversary targets, and the United States retained a small reserve to ensure sufficient capability to deter further aggression in any post-exchange, post-conflict environment. Weapons were dedicated to specific targets, and the requirements for target defeat did not change dramatically year-to-year….” The 2001 NPR “made distinctions among the contingencies for which the United States must be prepared. These contingencies were categorized as immediate, potential, or unexpected….” “Instead, the size of the U.S. nuclear force is now based on the ability of the operationally deployed force, the force structure, and the supporting nuclear infrastructure to meet a spectrum of political and military goals. These considerations reflect the view that the political effects of U.S. strategic forces, particularly with respect to both central strategic deterrence and extended deterrence, are key to the full range of requirements for these forces and that those broader goals are not reflected fully by military targeting requirements alone.” |

.

Still confused? What I think they are trying to say is that the target sets for some contingencies no longer have to be covered by operationally deployed nuclear warheads on a day-by-day basis.

What has permitted this change is not a deletion of strike plans against the Russian target base per ce (which has shrunk considerably since the 1980s), but rather the extraordinary flexibility that has been added to the nuclear planning system and the weapons themselves over the past decade and a half. This flexible targeting capability – which ironically was started in the late 1980s in an effort to hunt down Soviet mobile missile launchers – has since produced a capability to rapidly target or retarget warheads in adaptively planned scenarios. Put simply, it is no longer necessary to “tie down” entire sections of the force to a particular scenario or group of targets (although some targets due to their characteristics necessitate use of certain warheads).

The more flexible war plan that exists today, which the 1,700-2,200 operational deployed strategic warhead level of the SORT agreement is sized to meet, is “a family of plans applicable to a wider range of scenarios” with “more flexible options” for potential use “in a wider range of contingencies.” And although they are no longer the same kind of strike plans that existed in the 1980s, some of them still cover Russia to meet the guidance of the Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy document from 2004:

| “U.S. nuclear forces must be capable of, and be seen to be capable of, destroying those critical war-making and war-supporting assets and capabilities that a potential enemy leadership values most and that it would rely on to achieve its own objectives in a post-war world.” |

.

Concluding Observations

The political motivation for this paper is Congress’ demand for a comprehensive review of US nuclear policy before considering whether to approve industrial-scale production of new nuclear warheads. To that end, the paper presents the Defense and Energy department’s nuclear weapons requirement “logic” in an attempt to create a basis for anyone who is considering changing US nuclear weapons policy, strategy, and force structure.

The paper says the US has already made “historic reductions” in its deployed nuclear forces – a fact given the Cold War only happened once and has been over for two decades – and comes tantalizingly close to acknowledging that the warhead level set by the SORT agreement essentially is the START III level framework agreed to by Presidents Clinton and Yeltsin in Helsinki in 1997.

Indeed, by closely and explicitly aligning itself with policies pursued by the Clinton and first Bush administrations, the paper seeks to tone down the controversial aspects of the current administration’s nuclear policy and portray it as a continuation of long-held positions. Whether that will help ease congressional demands for change remains to be seen.

Yet for a paper that portrays to describe the role of nuclear weapons “in the 21st century” – a period extending further into the future than the nuclear era has lasted so far – is comes across as strikingly status quo. A better title would have been “in the first decade of the 21st century.”

It offers no options for changing the role of nuclear weapons or reducing their numbers beyond the SORT agreement – it even states that “no decisions have been made about the number or mix of specific warheads to be fielded in 2012.” The only option for reducing further, the paper indicates, is if Congress approves production of new nuclear warheads (including the RRW that Congress has rejected) that can replace the current types. And even that would require a production far above the currently planned level.

The central message of the paper seems to be that two decades of nuclear decline is coming to an end and that all nuclear weapon states will retain, prioritize, and modernize their nuclear forces for the indefinite future. The US should follow their lead, the paper indicates, and “maintain a credible deterrent at these lower levels” for the long haul. To do that, the United States needs nuclear forces “second to none” “that can adapt to changing needs.”

Background Information: National Security and Nuclear Weapons in the 21st Century | US Nuclear Forces 2008 | 2001 Nuclear Posture Review Report (reconstructed)

Online debate on Russia at The Economist

At a House Committee on Foreign Affairs meeting 9 September 08 members of Congress discussed what the U.S. response should be to Russia’s aggressive actions in Georgia last month. Most members of the Committee acknowledged that some sort of response was necessary to voice U.S. concerns about the possibility of a more aggressive Russian foreign policy, while they also conceded that the U.S. does need Russia’s cooperation on important matters of international security, such as helping to influence Iran’s nuclear ambitions. An interesting debate is being hosted online on this topic by The Economist – click here to link to it.

War in Georgia and Repercussions for Nuclear Disarmament Cooperation with Russia

In an earlier blog post, arguments were discussed from a 12 June 08 meeting of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs for and against the signing of a civilian nuclear cooperation agreement (123 Agreement) with Russia. At the time, the most salient issues were our ability to influence Russia’s position vis-à-vis Iran’s nuclear ambitions and the possibility that the 123 Agreement would restart domestic reprocessing, reversing 30 years of US policy. Since then, a full scale military operation has taken place between Russia and Georgia, a newly democratic ally of the U.S. who sent 2,000 troops to support U.S. efforts in Iraq. Now both Russian and American leaders want to remove the 123 Agreement from consideration for the time being, so as not to allow current events to color any debates about passing the legislation. Those in favor of the 123 Agreement believe that it would open up greater cooperation with Russia on issues such as pressuring Iran on its nuclear program. Whether this is true or not, if the 123 Agreement is now off the table because of Russia’s actions in Georgia, how much has this conflict damaged our ability to cooperate with Russia on nuclear arms control in the future? (more…)

The RISOP is Dead – Long Live RISOP-Like Nuclear Planning

|

| Launch control officers at Minot Air Force Base practice launching their high-alert ICBM. But the hypothetical Russian nuclear strike plan that originally led to the requirement to have nuclear forces on alert has been canceled. So why are the ICBMs still on alert? |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. military has canceled the Red Integrated Strategic Offensive Plan (RISOP), a hypothetical Russian nuclear strike plan against the United States created and used for decades by U.S. nuclear war planners to improve U.S. nuclear strike plans against Russia.

The cancellation appears to substantiate the claim made by Bush administration and military official, that the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review removed Russia as an immediate contingency for U.S. nuclear strike planning. But implementing the shift was not a high priority, lasting almost the entire first term of the administration.

Despite the shift, however, declassified documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act also show that RISOP-like and “red” analysis continues, and that that the cancellation was necessary to allow STRATCOM to broaden nuclear strike planning beyond Russia.

A Brief RISOP History

The RISOP dates back to the 1960s shortly after the first SIOP (Single Integrated Operational Plan), the Cold War name for the overall U.S. strategic war plan. An important element of refining and improving the effectiveness of the SIOP was to “wargame” it against the Soviet Union and more recently Russia. To do that, planners at Joint Staff and Strategic Air Command (SAC) developed a hypothetical Soviet War plan based on the latest intelligence about Soviet/Russian doctrine, strategy and weapons capabilities. To assist with coordination and planning, Joint Staff established the Red Planning Board (RPB), which included members of all the services and key agencies but was chaired by Joint Staff.

|

Figure 1: |

|

|

RISOP updates coincided with SIOP updates. The following declassified (heavily redacted) briefings show the content and structure of the 1996, 1997 and 1998 RISOP plans: * Joint Staff RISOP-96 Brief, April 1995 |

RISOP was based on the latest intelligence about Soviet/Russian nuclear strategy and forces, but the declassified documents show that Joint Staff and STRATCOM did not consider it an intelligence appraisal of those capabilities. Nor did it represent a judgment on the most likely Russian geopolitical intentions. Instead, RISOP was described as one of many possible and plausible courses of action based on Defense Intelligence Agency estimates of Russia force employment consistent with their military doctrine. But since planners probably didn’t want to wargame SIOP against anything but the “real” threat, RISOP most likely was the best possible estimate of the Russian posture.

RISOP was primarily a U.S. nuclear war planning tool. As a detailed opposing force threat plan, it was used by SAC and later STRATCOM in computer simulations to evaluate updates to the SIOP plan; RISOP updates coincided with SIOP updates. RISOP was also used to conduct force structure, arms control, and continuity of government analysis, and to carry out communications studies and prelaunch survivability computations and other strategic analysis.

The Slow Wheels of Change

Responsibility for production of RISOP was transferred from Joint Staff to STRATCOM in late 1996. The RPB was maintained, however, to ensure, among other things, that STRATCOM didn’t “cook the books,” as one of the declassified briefings put it. But the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) changed the planning assumptions against Russia. Whereas the RISOP plans of the late 1990s (see Figure 1) envisioned Russian nuclear attacks against the United States, its allies, and China, those assumptions were clearly out of sync with the political and military realities in Russia. The NPR instead determined that “a [nuclear strike] contingency involving Russia, while plausible, is not expected,” and that the size of the operational U.S. nuclear arsenal is “not driven by an immediate contingency involving Russia.” Thus, the overall planning assumption shifted from urgent to plausible.

|

Table 1: |

|

Dec 2001: NPR completed

|

But despite statements about the importance of ending the adversarial relationship with Russia, changing the nuclear planning against Russia apparently was not a priority and would have to wait almost the entire first term of the Bush administration. The NPR was completed in late 2001, the NPR Implementation Plan published in March 2003, the new Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy (NUWEP) signed in April 2004, and a new Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan nuclear supplement issued in December 2004, formally removing the requirement for the RISOP. Finally, in February 2005, four years and two months after the NPR, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued the instruction that formally cancelled the RISOP and the RPB (see Table 1).

Despite the policy change toward Russia, the RPB had not made any changes to the RISOP since 1998, following President Clinton’s PDD-60 directive that removed the requirement to plan for protracted nuclear war with Russia. As one Joint Staff official remarked in an email: “Sometimes the wheels of change move slowly.”

The “New” Nuclear Planning

The new planning guidance was laid out in the nuclear supplement to the Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan (JSCP), formally known as CJCSI 3110.04B or JSCP-N (see Figure 2 for earlier JSCP-N), which was published on December 31, 2004. This document instructed STRATCOM to “perform broader campaign level analysis than the previous requirement which focused on the RISOP.” In the words of the RPB, STRATCOM’s “red attack plan may also be broader than the scope of the RISOP.”

|

Figure 2: |

|

|

|

This broadening probably reflects the efforts to expand strike planning beyond Russia with increased focus on China and regional states armed with weapons of mass destruction (WMD). A “notable change” for the strike plan put in effect in March 2003 (OPLAN 8044 Revision 03) included executable strike options against regional states, options that were probably carried forward into the current OPLAN 8044 Revision 05.

Of course, Russia didn’t just disappear from the planning requirements. The NPR itself warned that although the country no longer is considered an immediate contingency, “Russia’s nuclear forces and programs, nevertheless, remain a concern. Russia faces many strategic problems around its periphery and its future course cannot be charted with certainty.” The NPR concluded that “U.S. planning must take this into account.” In addition, the NPR hedged, “in the event that U.S. relations with Russia significantly worsen in the future, the U.S. may need to revise its nuclear force levels and posture.” Relations have certainly not improved.

The previous JSCP-N from January 2000, which was updated in July 2001 (see here for chronology of nuclear guidance), required Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) and Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) to provide information to the Joint Staff for use in RISOP development. But the new JSCP-N moved this role to STRATCOM by directing that DIA and DISA “will support USSTRATCOM directly by providing data for red analysis.” The JSCP-N directs STRATCOM to perform three levels of analysis for the strike plans:

Phase I: Consequence of Execution Analysis

Phase II: Campaign Level Analysis

Phase III: Intelligence Assessment Analysis

Campaign Analysis is “a campaign level analysis to provide a stochastic check of the deterministic models used for the revision report consequences of execution analysis and to assess OPLAN 8044, REVISION XX’s [formerly SIOP] capability to comply with approved guidance. Such analysis will encompass various scenarios and may include the potential contribution of SACEUR’s MCOs [Major Combat Operations] as required.”

Despite the cancellation of RISOP, a 2004 STRATCOM briefing stated, STRATCOM “will continue to produce RISOP-like analysis,” and “procedures for requesting data and providing products will remain the same.” As before, use of the data will support prelaunch survivability analysis for ICBMs and bombers, base survivability of SSBN bases, and command, control and communication vulnerability and survivability analysis. All to ensure that U.S. nuclear forces will survive and endure against any nuclear adversary, including Russia.

Comments

U.S. nuclear forces were placed on high alert to counter the Soviet nuclear threat, and the effectiveness of the strike plan for their potential use continuously refined and improved by wargaming it against the RISOP. Now that Russia is not considered a nuclear threat and the RISOP has been canceled, how long will it be before the alert posture is canceled as well?

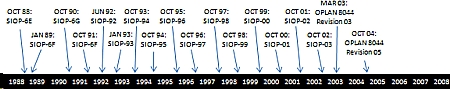

The U.S. strategic war plan – OPLAN 8044 Revision 05 – is currently structured around a reduced but more flexible posture with the same overall Triad structure as during the Cold War and over 1,000 nuclear warheads on high alert. Surprisingly, although RISOP was canceled in 2005, no revision has been made to OPLAN 8044 since October 2004 – the first time in U.S. post-Cold War nuclear history that the nation’s strategic war plan has not been overhauled at least once per year (see Figure 3).

|

Figure 3: |

|

| STRATCOM has not published an updated U.S. strategic war plan since October 2004, breaking with a historical pattern of annual overhauls. The change probably reflects development of a new plan structure and more flexible adaptive planning capabilities. |

.

The explanation might be that major overhauls are no longer necessary because today’s plan has become flexible enough to accommodate changes on a ongoing basis without a need for a new revision; a “living SIOP.” OPLAN 8044 now consists of a family of plans applicable in a wider range of scenarios, with more flexible options to defeat adversaries in a wider range of contingencies than during the Cold War. Cancellation of RISOP might have reduced the focus on Russia, but it was also part of a broadening of nuclear strike planning to other potential adversaries.

The s l o w cancellation of the Russian-focused RISOP and the continuation of RISOP-like and red nuclear war planning for a broader and more flexible war plan should be an important lesson for the next president: unless he keeps his eye on the issue and pays continuous attention to how and when the military translates his initial guidance into a myriad of war planning requirements and strike options, the future U.S. nuclear posture – and with it the hope of significantly reducing the role and salience of nuclear weapons in the world – will only change v e r y slowly and not necessarily in the direction he had intended.

US – Russia 123 Agreement on the Hill

On Thursday, June 12 the House Foreign Relations Committee met for over three hours and heard testimony from members of the Committee, a representative of the Bush administration, and expert witnesses regarding the pros and cons of supporting the Agreement Between the United States and Russia for Cooperation in the Field of Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy (Agreement) that President Bush submitted to Congress. As discussed in an earlier blog, the Agreement will have to sit before the Congress for 90 continuous days, and will pass unless Congress enacts a joint resolution of disapproval. Such legislation, H.J.Res 85, has already been submitted by Congressman Edward J. Markey (D – MA), a staunch opponent to nuclear power and thus to civilian nuclear cooperation agreements. The mood of those legislators at the hearing was generally one of skepticism, as members of Congress searched for reasons to support the Agreement. (more…)

Russian Nuclear Missile Submarine Patrols Decrease Again

By Hans M. Kristensen

The number of deterrence patrols conducted by Russia’s 11 nuclear-powered ballistic missiles submarines (SSBNs) decreased to only three in 2007 from five in 2006, according to our latest Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

In comparison, U.S. SSBNs conducted 54 patrols in 2007, more than three times as many as all the other nuclear weapon states combined.

The low Russian patrol number continues the sharp decline from the Cold War; no patrols at all were conducted in 2002 (see Figure 1). The new practice indicates that Russia no longer maintains a continuous SSBN patrol posture like that of the United States, Britain, and France, but instead has shifted to a new posture where it occasionally deploys an SSBN for training purposes.

An Occasional Sea-Based Deterrent

The shift to an occasional sea-based deterrent became apparent in 2007, when then Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov declared on September 11 that five SSBNs were on patrol at that time. Four months later, I received information from U.S. Naval Intelligence showing that those five patrols were all Russian SSBNs did that year. Combined, the two sources indicated a cluster of patrols at approximately the same time rather than distributed throughout the year.

|

Figure 1: |

|

| Russian SSBNs conducted only three deterrent patrols in 2007, a decline from five in 2006. |

.

The reason for the shift is unclear. Perhaps the Russian navy is still not over the financial and technical constraints that hit it after the collapse of the Soviet Union. SSBNs can launch their missile from pier side if necessary, although such a posture essentially converts each SSBN into a very soft and vulnerable target. Russia might simply have decided that it’s no longer necessary to maintain a continuous nuclear retaliatory force at sea, and that a few training patrols are all that’s needed to be able to deploy the SSBNs in a hypothetical crisis if necessary.

SSBN Patrol Areas

Little is known in public about where Russian SSBNs conduct their deterrent patrols. However, in 2000, U.S. Naval Intelligence released a series of rough patrol maps for Soviet/Russian SSBNs that showed the locations of the patrol areas used by Delta IV and Typhoon class SSBNs in the late-1980s and 1990s (see Figure 2). The few SSBNs that occasionally sail on patrol today probably use roughly the same areas.

|

Figure 2: |

|

| Russian SSBN patrol areas today are probably similar to those used in the 1990s. |

.

In Perspective

The decline in SSBN patrols is in stark contrast to Russian bomber and surface fleet operations in 2006-2007, which are said to have increased in scope and reach. For now, at least, SSBN patrols are not used to “signal” Russian status.

Approximately 20 percent of Russia’s strategic warheads are sea-based. But with the upcoming replacement of old Delta III SSBNs and their three-warhead missiles with the new Borey SSBNs (the first of which is scheduled to enter service later this year) with six-warhead missiles, the SSBNs’ share of the posture might increase to approximately 30 percent by 2015.

Overall, the Nuclear Notebook estimates that Russia currently has approximately 5,200 nuclear warheads in its operational stockpile, including some 3,110 strategic and 2,090 non-strategic warheads. Another 8,800 warheads are thought to be in reserve or awaiting dismantlement.

Additional information: Russian Nuclear Forces 2007, Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists