New START Ratification: Seeing the Bigger Picture

|

| Morton Halperin speaks at CSIS |

By Hans M. Kristensen

Kevin Kallmyer at CSIS has an interesting recap of a recent debate between Paula DeSutter and Mort Halperin about the New START Treaty.

Ratification of the treaty is held up in Congress by a handful of Senators who (mis)use questions about, among other issues, verification to extort billions of dollars to pet nuclear modernization projects at the expense of greater U.S. interests.

During the CSIS debate, Mort Halperin provided an enlightening anecdote about how to judge whether ratification of the treaty is in the U.S. interest. It cuts to the heart of what is important and deserves a repost here:

How do you decide whether a Treaty is in the American interest in relation to verification? The question cannot be are we sure that we will have 100% confidence that we would detect the first instance of Russian cheating. The question has to take into account the limits of the Treaty, and some degree of Russian cheating, is it in our interest to have the limit in the treaty, as opposed to not constraining the Russian forces. Our notion of what is acceptable verification goes back to the Reagan administration, it actually goes back before that…because the last time the Joint Chiefs of Staff held the view that a limit was not acceptable unless it could be 100% verifiable was in 1968. At that point, the Administration was planning to put forward a proposal to the Soviet Union to ban the further production of any ballistic missiles or submarines. The Joint Chief’s position then was to we can only include things in the agreement if we could be absolutely certain there will be no Russian cheating. A navy officer came to me one day and said, “Well, we cannot include submarines in the agreement.”

I said, “Why is that?”

He said, “Because the CIA has just come out with its estimate that said the Russians could cheat on an agreement that bans Russia from building any more ballistic missile submarines.”

And I said, “What does it say?”

He said, “It says the Russians could build as many as 3 submarines and we wouldn’t detect it, and only if they build a fourth submarine could we have very high confidence of detection.”

And I said, “How many submarines doe we have now?”

He said, “41.”I said, “How many submarines do we plan to have 10 years from now.”

He said “41.”

I said, “How many submarines do the Russians have now?”

He said, “I think one.”

I said, “How many do we think they will have in 10 years from now.”

He said, “50.”

I said, “So, you prefer a world where we do not limit this and the Russians have 50 submarines and we have 41, to a world where we have 41, and the Russians have [4] until we can be sure we detect the [5th] submarine.”

And he said, “That’s right, the principle is that you do not include something in an agreement that cannot be verified.”

I looked at him and said, “Well, I think I’m going to win this fight…and I did.”

And the Joint Chiefs changed their position then, to what is clearly the correct position. You ask yourself about each limit, including the warhead limit in this treaty; is it in our interest to have this limit, recognizing that there obviously could be some amount of Russian cheating. The question is how much Russian cheating can there be before we detect it, and the question is what is the strategic significance of that cheating. We have seen no such analysis, because no such analysis that could be presented would be the slightest bit persuasive. The fact is that with the margin of deterrence we have to deter a Russian attack, that the margins of cheating the Russians can do is simply insignificant to the security to the United States.

Check out the full debate at the CSIS web site.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

NATO Strategic Concept: One Step Forward and a Half Step Back

|

| NATO General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen presents the alliance’s new Strategic Concept |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The new Strategic Concept adopted today by NATO represents one step forward and a half step backward for the alliance’s nuclear weapons policy.

The forward-leaning part of the nuclear policy pledges to actively try to create the conditions for further reducing the number of and reliance on nuclear weapons, recommits to the ultimate goal of nuclear disarmament, and reaffirms that circumstances in which the alliance could contemplate using its nuclear weapons are “extremely remote.”

But the strategy fails to present any steps that reduce the number of or reliance on nuclear weapons. As such, the new Strategic Concept – Active Engagement, Modern Defence – falls short of the Obama administration’s recent Nuclear Posture Review.

Even so, there are important changes in the document that hint of things to come.

The Role of Nuclear Weapons

The new Strategic Concept does not explicitly reduce the role of NATO’s nuclear weapons. Instead, it echoes the Obama administration’s formulation that “as long as nuclear weapons exist,” NATO will remain a nuclear alliance.

And the formulation in the 1999 Strategic Concept that “NATO’s nuclear forces no longer target any country” is gone from the new document. Instead, it states that NATO “does not consider any country to be its adversary.”

Overall, the 2010 document is far less explicit than the 1999 document about what the role of nuclear weapons is. The previous document explicitly described the role “to preserve peace and prevent coercion and war of any kind…by ensuring uncertainty in the mind of any aggressor about the nature of the Allies’ response to military aggression,” and “demonstrate that aggression of any kind is not a rational option.”

The new document, in contrast, describes the role of nuclear weapons in very general terms, essentially with no specifics, and as part of an overall mix of nuclear and conventional capabilities.

Gone is the previous language about U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in Europe providing an essential political and military link between Europe and North America, or that sub-strategic forces provide a link with strategic forces.

Instead, the document states that it is the strategic forces of the United States, in particular, and to some extent Britain and France, that provide the “supreme guarantee of the security of the Alliance”.

US Nuclear Forces in Europe

Combined, these significant changes could be seen as hints of an attempt to lessen the importance the alliance attributes to having U.S. tactical nuclear weapons forward deployed in Europe.

To be sure, the document still contains what appears to be a commitment to some form of U.S. nuclear presence in Europe, by committing to “the broadest possible participation of Allies in collective defence planning on nuclear roles, in peacetime basing of nuclear forces, and in command, control and consultation arrangements.” (Emphasis added)

|

But this is vague language compared with the 1999 document. It could simply be met by Allies taking part in Nuclear Planning Group meetings, deployment of some U.S. dual-capable aircraft in Europe but without weapons, and Allies continuing to be part of the decision making process for potential use of nuclear weapons.

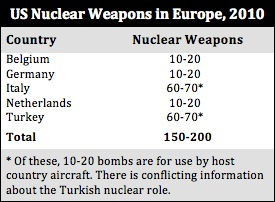

The number of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe today is down to 150-200 B61 bombs deployed at six bases in five countries (see table).

The Role of Russia

In the years between the 1999 and 2010, NATO unilaterally reduced the number of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons deployed in Europe by more than half, from 480 to 150-200 B61 bombs. The 1999 Strategic Concept did not mention Russia at all as a factor for sizing the U.S. deployment.

The new Strategic Concept, in contrast, returns Russia to a central position for how the Alliance sizes the number of U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

“In any future reductions,” NATO declares, “our aim should be to seek Russian agreements to increase transparency on its nuclear weapons in Europe and relocate these weapons away from the territory of NATO members.”

Moreover, “Any further steps must take into account the disparity with the greater Russian stockpiles of short-range nuclear weapons.”

While seeking to achieve reductions in Russian tactical nuclear weapons is important – it has more than 5,000 of them, formally linking the U.S. deployment in Europe to Russia seems to contradict the policy of the past two decades that the U.S. weapons in Europe are not directed against Russia. And NATO has repeatedly made unilateral reductions without demanding Russian reductions. Indeed, the new Strategic Concept declares that “NATO poses no threat to Russia,” and that the Alliance “does not consider any country to be its adversary.”

So to begin now to argue that the size of the U.S. arsenal in Europe is linked to Russia after all resembles the Cold War policy when NATO looked to Russia for sizing the U.S. arsenal in Europe.

Moreover, Russia’s tactical nuclear weapons posture is less tied to the U.S. nuclear posture in Europe and more to Russia’s perception of countering NATO’s superior conventional forces and defending the long border with China. Since those factors determine the size of the large Russian tactical nuclear weapons arsenal, it is hard to see why Moscow would agree to reduce its tactical nuclear weapons in return for reductions of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in Europe.

The Future

The changes in the new Strategic Concept are many and important. The language could hint that NATO may be preparing the ground for the withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe. But the way forward is muddled with preconditions on Russian reductions.

A joint communiqué from the Lisbon Summit might make things clearer tomorrow but it will require a new deterrence review in 2011 for NATO to translate what the Strategic Concept means for NATO’s nuclear posture.

Conditioning future reductions on Russia could be a roadblock, so hopefully the vague “aim to seek” and “taking into account” formulations don’t imply tit-for-tat reciprocity. The success of the unilateral withdrawals in the early 1990s suggests that a unilateral withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe would be more effective in stimulating a Russian response.

The Obama administration sees the emergence of a “new, tailored, regional deterrence architecture” that “make[s] possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” The new Strategic Concept seems to agree, so hopefully the Obama administration can now become more assertive in pushing for a withdrawal of the last U.S. tactical nuclear weapons from Europe so it can focus on an agreement to reduce U.S. and Russian tactical nuclear weapons in general.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Delay: Gambling With National and International Security

|

| A few Senators are preventing US inspectors from verifying the status of Russian nuclear weapons. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The ability of a few Senators to delay ratification of the New START treaty is gambling with national and international security.

At home the delay is depriving the U.S. intelligence community important information about the status and operations of Russian strategic nuclear forces. And abroad the delay is creating doubts about the U.S. resolve to reduce the number and role of nuclear weapons, doubts that could undermine efforts to limit proliferation.

New START may not be the most groundbreaking treaty ever, but it is a vital first step in moving U.S.-Russian relations forward and paving the way for additional nuclear reductions and nonproliferation efforts. Essentially all current and former officials and experts recommend verification of New START, and after more than 20 hearings and nearly 1,000 detailed questions answered it is time for the Senate to ratify the treaty.

Important Inspections

Ratification would set in motion a wide range of data exchange and on-site inspection activities. By delaying ratification, the Senators are depriving the U.S. intelligence community important information about Russian nuclear forces. Apart from monitoring how Russian strategic nuclear forces are evolving and operating, the information is important to avoid worst-case threat assessments that can negatively affect U.S.-Russian relations.

It has now been 348 days since the last U.S. inspection team left Russia.

During the 15 years the START Treaty was in effect between 1994 and 2009, U.S. teams conducted 659 inspections of Russian nuclear weapons facilities; Russian conducted 481 inspections of U.S. facilities.

The last U.S. on-site inspection took place on November 18-19, 2009, at an SS-25 mobile missile base near Teykovo, approximately 130 miles (210 km) northeast of Moscow.

.

That inspection had special meaning because the SS-25 is being phased out from this area and replaced with the new SS-27. While each SS-25 is equipped with one warhead, the SS-27 comes in two versions: one with a single warhead and one with three warheads. The U.S. intelligence community calls the latter the SS-27 Mod 2, while the Kremlin named it RS-24 so as to avoid conflict with the now expired START treaty.

One of the four bases at Teykovo has already been equipped with the SS-27 Mod 2, two still have the SS-25, while the fourth base has been emptied and might be converting to the newer missile. Within the next decade, all four bases may be equipped with the SS-27 Mod 2.

The Russians chose Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri for their final on-site inspection in the United States. That inspection took place on December 1-2, 2009, just two days before the treaty expired.

| B-2 of the 509th Bomb Wing over Whiteman AFB |

|

| Russia chose the B-2 base at Whiteman Air Force Base as its final inspection in the United States under the now expired START treaty. |

.

The Nonproliferation Gamble

From the outset, the Obama administration appears to have seen Russia as the main potential obstacle to the treaty, rather than the U.S. Senate. Absent a strategy to secure the votes for ratification early on, the tables have now turned; with the White House desperate to secure ratification, a few Senators who still see Russia through Cold War lenses have effectively managed to use hearings and voting rules to extort concessions (read: money) from the administration to modernize the nuclear weapons production complex and delivery systems.

| Senator Jon Kyl |

|

| A few senators, most prominently Senator Jon Kyl (R-Arizona), have managed to delay ratification of the New START treaty. |

.

The administration quickly agreed to boost the FY 2011 budget for the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) well above the FY 2010 level. But that didn’t satisfy the Senators. So when Congress was unable to approve the budget before the mid-term election, the administration agreed that a Continuing Resolution (CR) designed to keep federal agencies operating at FY2010 budget levels through December 3rd would include an exemption for NNSA’s weapons program to fund the agency at the higher FY 2011 budget request – about $7 billion or an additional $625 million. But since the provisions in the defense appropriations bill and report don’t apply to the CR, the appropriators have lost control of how the funds are used; Congress is basically providing NNSA with a blank check to spend the $7 billion.

In addition, in an effort to buy the Senators’ votes for ratification during the “lame duck” session before the new Congress begins, the administration has offered $600 million more for the FY 2012 NNSA budget above FY 2011 levels, as well as an additional $3.6 billion spread out over FY 2013-2016.

Altogether, in a nuclear spending spree that would have been inconceivable during the Bush administration, the Obama administration plans to spend well over $180 billion to modernize nuclear weapons delivery systems and production facilities over the next decade.

There is a real risk that in the coming years, this modernization could backfire and undermine the second pillar of U.S. nuclear policy: strengthening nonproliferation.

The reason is simple: U.S. nonproliferation efforts dependent upon international support, but if the international community sees the increased nuclear modernizations as contradicting the U.S. pledge to work toward nuclear disarmament, some countries may well decide not to support the administration’s nonproliferation agenda.

This risk could be compounded later this week if NATO approves a new Strategic Concept that reaffirms the importance of nuclear weapons – and fails to order the withdrawal of the remaining tactical nuclear weapons from Europe.

The Senate needs to demonstrate that it understands that the Cold War is over and that it cares more about national and international security than politics by ratifying the New START treaty before Christmas. And the administration must be careful to balance its nuclear modernization plans with the need to sustain the vision of nuclear disarmament that so inspired the international community just 18 months ago.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

START in a Lame Duck

|

| The Senate should vote on the New START during the “lame duck” session. |

The New START arms control treaty, negotiated between the United States and Russia and signed by the presidents of both countries last April, is awaiting ratification by the United States Senate. Objections to the treaty rest primarily upon misunderstandings or misrepresentation. In addition, though, some opponents of the treaty are arguing that, whether one supports or opposes the treaty, it is improper for the Senate to vote on the treaty during the post-election or “lame duck” session of Congress. But there is neither a constitutional nor a commonsense reason to delay a vote.

Some of us who hope to dramatically and rapidly reduce the salience of nuclear weapons were disappointed that the treaty was rather modest, but it clearly moves in the right direction. This treaty is not a radical departure from past treaties, it is not even a post-Cold War treaty; it is an extrapolation of the Cold War SALT and START treaties stretching back to the days of the Soviet Union. Given the current strategic security environment, neither Richard Nixon, nor Ronald Reagan, nor George H. W. Bush would blink an eye at this treaty. (more…)

Nuclear De-Alerting Panel at the United Nations

|

| Panelists from left: Hans M. Kristensen (FAS), John Hallam (Nuclear Flashpoint), Dell Higgie (New Zealand Ambassador for Disarmament), Christian Schoenenberger (Swiss UN Mission), Col Valery Yarynich (Institute of the United States and Canada, Russian Academy of Sciences), Stephen Starr (Physicians for Social Responsibility) |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

On Wednesday, October 13th, I gave a briefing at the United Nations on the status of U.S. and Russian nuclear forces in the context of the interesting article Safe and Smaller recently published in Foreign Affairs.

One of the co-authors, Valery Yarynich, a retired colonel who served at the Center for Operational and Strategic Studies of the Russian General Staff, spoke about the main conclusion of the article: that is possible to significantly reduce the alert-level of U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear weapons without creating risks of crisis instability.

That conclusion directly contradicts the Obama administration’s recently completed Nuclear Posture Review, which rejected a reduction of the alert rates for land- and sea-based ballistic missiles because, “such steps could reduce crisis stability by giving an adversary the incentive to attack before ‘re-alerting’ was complete.”

The panel coincided with the meeting of the First Committee of the General Assembly, during which New Zealand submitted a resolution on decreasing the operational readiness of nuclear weapons.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Rasmussen: Lay Short-Range Nuclear Weapons Thinking to Rest

By Hans M. Kristensen

The next steps in European security should include additional reductions in the number short-range nuclear weapons in Europe, according to a video statement issued by NATO General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen:

“We also have to make progress sooner or later in our efforts to reduce the number of short-range nuclear weapons in Europe. NATO has cut the number of short-range nuclear weapons in Europe by over 90 percent. But there are still thousands of short-range nuclear weapons left over from the Cold War and most of them are in Russia. NATO is not threatening Russia and Russia is not threatening NATO. Time has come to lay this Cold War thinking to rest and focus on the common threats we face from outside: terrorism, extremism, narcotics, proliferation of missiles, weapons of mass destruction, side by side, and piracy. We can make progress of all three tracks – missile defense, conventional forces, and nuclear weapons – and create a secure Europe. It is time to stop spending our time and resources watching each other and look outward at how to reinforce our common security hope.”

That vision appears similar to the “new regional deterrence architecture” that several recent Obama administration reviews concluded would permit a reduction of the role of nuclear weapons. With that in mind, and Rasmussen’s conclusion that “Russia is not threatening NATO” and that the “time has come to lay this Cold War thinking to rest,” it should be relatively straightforward for him to recommend a withdrawal of the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe.

Unfortunately, rather than taking the initiative to complete the withdrawal of U.S. short-range nuclear weapons from Europe – a process that have been underway now for two decades but held up by Cold War thinking and NATO bureaucrats, Rasmussen instead appears to weave the future of the weapons in Europe into a web of new conditions that must be met first. In a speech at the Aspen Institute in Rome, Rasmussen described his three-track vision of collaborating with Russia on missile defenses, conventional weapons negotiations, and reducing short-range nuclear weapons:

“I think we have before us three tracks, which, if we follow them, will lead to a different, better and safer Europe: where we don’t look over our shoulders for someone else’s tanks or fighters; where missile defences bind us together, and protect us too; and where steadily, the number of short-range nuclear weapons on the continent is going down.”

Nuclear reductions appear to be the third track, after missile defense collaboration and conventional arms negotiations with Russia. For two decades, NATO has insisted the U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe have no military mission and that they’re not linked to Russia. The alliance has repeatedly been capable of and willing to make unilateral reductions – even complete withdrawal from Greece and the United Kingdom – without conditions or demanding reductions in Russian short-range nuclear weapons.

So why start linking reductions to Russia now?

Doing so seems to turn back the clock to the Cold War when NATO looked to Russia’s military forces to determine its nuclear posture in Europe. If the conclusion that “Russia is not threatening NATO” is more than words, then why make a three-track vision that assumes that Russia’s short-range nuclear weapons threaten NATO? Because the short-range weapons are not covered by any arms control regime, Rasmussen explains, the lack of transparency “makes allies cautious.”

There are certainly many good reasons to want to try to secure and reduce Russian short-range nuclear weapons. But if Russia is not threatening NATO, then Russian and U.S. short-range nuclear weapons should be addressed as a generic arms control challenge and not one that is linked to whether the U.S. has nuclear weapons in Europe or not.

| Did They Lay Cold War Nuclear Thinking to Rest? |

|

| During his meeting with Italian defense minister Ignazio La Russa, did Rasmussen discuss the possibility of a withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe, including Italy, or just the threat of Russian short-range nuclear weapons? |

.

If NATO unilaterally withdrew the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe, what would happen?

Would Russia decide that it didn’t have to reduce its short-range nuclear weapons? Hardly, since those forces seem to be more tied to Russia’s perception of NATO’s conventional superiority and a need to safeguard the long border with China. Besides, many of the Russian weapons are so old that they’re likely to be retired soon.

Would Russia get an advantage in a hypothetical crisis with NATO? Hardly, since it would require that Russia ignores NATO’s conventional superiority and U.S., British, and French long-range nuclear forces.

Would Russia decide that it had more freedom to deploy conventional forces on NATO periphery? Hardly, since such decisions seem to be made regardless of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe.

Would Iran somehow conclude that it could take additional steps acquiring nuclear weapons capability? Hardly, since its security assessment is not affected by whether the U.S. deploys nuclear weapons in Europe and it would still face serious consequences if it developed – certainly if it used – nuclear weapons.

Would Turkey and Eastern European NATO members conclude that NATO’s security guarantee was no longer credible and begin building nuclear weapons? Hardly, since their assurance is much more determined by conventional forces and political relations, and, to the limited extent nuclear forces play any role, the long-range forces of the United States, Britain, and France, would be more than adequate for any realistic scenario. Moreover, any NATO member country that began to develop nuclear weapons would face enormous pressure from the international community and from within NATO itself.

To the extent that some officials in some eastern European NATO countries feel uneasy about the inevitable withdrawal of U.S. short-range nuclear weapons from Europe, the obvious job for the Obama administration and the majority of NATO countries that favor a withdrawal is a concerted effort to educate those officials about the significant conventional and long-range nuclear capabilities that will continue to provide security when the short-range weapons are withdrawn. The revised Strategic Concept to be adopted at the Lisbon Summit in November is expected to reaffirm a role for nuclear weapons in NATO.

Rasmussen would do more for European security if he tried to decouple the future of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe from the need to reduce and eventually eliminate short-range nuclear weapons in general. Doing so would indeed be to “lay this Cold War thinking to rest.”

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Commanders Endorse New START

|

| The men behind a decade and a half of U.S. strategic nuclear planning say the New START treaty will enhance American national security. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Seven former commanders of U.S. nuclear strategic planning have endorsed the New START treaty and recommended early ratification by the U.S. Senate.

In a letter sent to Senator Carl Levin and John McCain of the Senate Armed Services Committee and Senators John Kerry and Richard Lugar of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the retired nuclear commanders conclude that the treaty “will enhance American national security in several important ways.”

The list includes four former commanders of U.S. Strategic Air Command (SAC) and four former commanders of U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) – one served both as SAC and STRATCOM commander – who were responsible for U.S. strategic nuclear war planning and for executing the strategic war plan during the last phases of the Cold War and until as recently as 2004.

In doing so, the nuclear commanders – who certainly can’t be accused of being peaceniks – effectively pull the rug under the feet of the small number of conservative Senators who have held the treaty and U.S. nuclear policy hostage with a barrage of nitpicking and frivolous questions and claims about weakening U.S. national security interests.

The endorsement by the former nuclear commanders adds to the extensive list of current and former military and civilian leaders who have recommended ratification of the New START treaty. In fact, it is hard to find any credible leader who does not support ratification.

It’s time to end the show and do what’s right: ratify the New START treaty!

REPRODUCTION OF LETTER:

July 14, 2010

Senator Carl Levin, Chairman, Armed Services Committee

Senator John McCain, Ranking Member, Senate Armed Services CommitteeSenator John F. Kerry, Chairman, Senate Foreign Relations Committee

Senator Richard G. Lugar, Ranking Member, Senate Foreign Relations CommitteeGentlemen:

As former commanders of Strategic Air Command and U.S. Strategic Command, we collectively spent many years providing oversight, direction and maintenance of U.S. strategic nuclear forces and advising presidents from Ronald Reagan to George W. Bush on strategic nuclear policy. We are writing to express our support for ratification of the New START Treaty. The treaty will enhance American national security in several important ways.

First, while it was not possible at this time to address the important issues of non-strategic weapons and total strategic nuclear stockpiles, the New START Treaty sustains limits on deployed Russian strategic nuclear weapons that will allow the United States to continue to reduce its own deployed strategic nuclear weapons. Given the end of the Cold War, there is little concern today about the probability of a Russian nuclear attack. But continuing the formal strategic arms reduction process will contribute to a more productive and safer relationship with Russia.

Second, the New START Treaty contains verification and transparency measures—such as data exchanges, periodic data updates, notifications, unique identifiers on strategic systems, some access to telemetry and on-site inspections—that will give us important insights into Russian strategic nuclear forces and how they operate those forces. We will understand Russian strategic forces much better with the treaty than would be the case without it. For example, the treaty permits on-site inspections that will allow us to observe and confirm the number of warheads on individual Russian missiles; we cannot do that with just national technical means of verification. That kind of transparency will contribute to a more stable relationship between our two countries. It will also give us greater predictability about Russian strategic forces, so that we can make better-informed decisions about how we shape and operate our own forces.

Third, although the New START Treaty will require U.S. reductions, we believe that the post-treaty force will represent a survivable, robust and effective deterrent, one fully capable of deterring attack on both the United States and America’s allies and partners.

The Department of Defense has said that it will, under the treaty, maintain 14 Trident ballistic missile submarines, each equipped to carry 20 Trident D-5 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). As two of the 14 submarines are normally in long-term maintenance without missiles on board, the U.S. Navy will deploy 240 Trident SLBMs.

Under the treaty’s terms, the United States will also be able to deploy up to 420 Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and up to 60 heavy bombers equipped for nuclear armaments. That will continue to be a formidable force that will ensure deterrence and give the President, should it be necessary, a broad range of military options.

We understand that one major concern about the treaty is whether or not it will affect U.S. missile defense plans. The treaty preamble notes the interrelationship between offense and defense; this is a simple and long-accepted reality. The size of one side’s missile defenses can affect the strategic offensive forces of the other. But the treaty provides no meaningful constraint on U.S. missile defense plans. The prohibition on placing missile defense interceptors in ICBM or SLBM launchers does not constrain us from planned deployments.

The New START Treaty will contribute to a more stable U.S.-Russian relationship. We strongly endorse its early ratification and entry into force.

Sincerely,

General Bennie Davis (USAF, Ret) [SAC CINC 1981-1985]

General Larry Welch (USAF, Ret) [SAC CINC 1985-1986]

General John Chain (USAF, Ret) [SAC CINC 1986-1991]

General Lee Butler (USAF, Ret) [SAC CINC 1991-1992, STRATCOM CINC 1992-1994]

Admiral Henry Chiles (USN, Ret) [STRATCOM CINC 1994-1996]

General Eugene Habiger (USAF, Ret) [STRATCOM CINC 1996-1998]

Admiral James Ellis (USN, Ret) [STRATCOM CINC 2002-2004]

The original letter is here.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

FAS side events at the RevCon

by Alicia Godsberg

Yesterday FAS premiered our documentary Paths To Zero at the NPT RevCon. The screening was a great success and there was a very engaging conversation afterward between the audience and Ivan Oelrich, who was there to promote the film. As a result of some suggestions, we are hoping to translate the narration to different languages so the film can be used as an educational tool around the world. You can see Paths To Zero by following this link – we will also be putting up the individual chapters soon.

This morning I spoke at a side event at the NPT RevCon entitled “Law Versus Doctrine: Assessing US and Russian Nuclear Postures.” I was asked to give FAS’s perspective on the New START, NPR, and new Russian military doctrine. Several people asked me for my remarks, so I’m posting them below the jump. (more…)

Russian Nuclear Weapons Account Falls Short

|

| A Russian brochure misrepresents the size of the Russian arsenal. Click image to download copy of full procure |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A brochure handed out by the Russian government at the ongoing nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference in New York appears to misrepresent the size of the Russian nuclear arsenal.

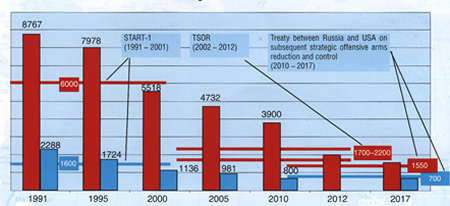

The brochure Practical steps of the Russian Federation in the field of nuclear disarmament includes a chart that lists the reduction in Russian strategic nuclear weapons under three arms control agreements and is intended to demonstrate Russia compliance with the NPT’s Article VI. The chart shows strategic warhead numbers for roughly five-year intervals in 1991-2017 and characterizes the numbers as the “actual quantity of nuclear weapons.”

But the numbers are not “actual quantities” of weapons but so-called aggregate numbers previously published in the Memorandum of Understanding exchanged by Moscow and Washington under the now expired START treaty.

| SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24) |

|

| The brochure lists more strategic warheads in 2012 than Russian missiles can carry. |

The aggregate numbers are inaccurate because they include so-called phantom weapons that were not operational at the time, and because they attribute a declared warhead number to each delivery platform rather than what is actually deployed. The aggregate numbers also do not include strategic warheads that are not counted as deployed.

The number for 2012 on the graph is curious because it lists 2,000 strategic warheads, the medium value of the 1,700-2,200 of the Moscow Treaty. But since Russia doesn’t count its strategic bomber weapons as deployed under the Moscow Treaty and the New START agreement only counts one warhead per bomber, practically all of the listed 2,000 warheads would have to be on ballistic missiles. Yet the ballistic missiles Russia is projected to deploy in two years don’t have enough warhead spaces for 2,000 warheads.

The Russian brochure also illustrates the reduction that has occurred in Russian tactical nuclear weapons, stating that the current inventory is 25% of what it was in 1991. But, again, Russia fails to disclose the real number, which is now at an estimated 5,000 warheads.

| Russian Non-Strategic Weapons Reduced |

|

| The Russian brochure states that non-strategic warheads have been reduced but to what? |

.

The United States disclosed the size of its military nuclear weapons stockpile last week and has been declaring since 2006 how many of those warheads are deployed on ballistic missiles and heavy bomber bases. Russia should follow the American example and disclose the size of its nuclear weapons stockpile. Doing so would support Russian interests far better than outdated Cold War nuclear secrecy.

Ironically, Russia could have demonstrated deeper reductions had it listed its actual number of deployed strategic warheads instead of the aggregate numbers. Russia currently deploys an estimated 2,600 strategic warheads, significantly less than the 3,900 listed in the brochure. Transparency is better.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

United States Discloses Size of Nuclear Weapons Stockpile

|

| The Obama administration has declassified the history and size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile, a long-held national secret. Click image to get the fact sheet. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

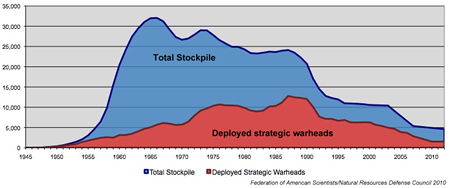

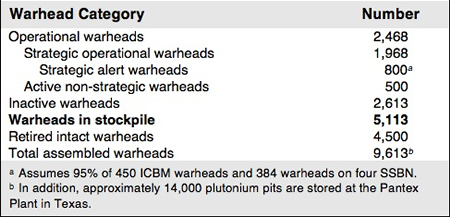

The Obama administration has formally disclosed the size of the Defense Department’s stockpile of nuclear weapons: 5,113 warheads as of September 30, 2009.

For a national secret, we’re pleased that the stockpile number is only 87 warheads off the estimate we made in February 2009. By now, the stockpile is probably down to just above 5,000 warheads.

The disclosure is a monumental step toward greater nuclear transparency that breaks with outdated Cold War nuclear secrecy and will put significant pressure on other nuclear weapon states to reciprocate.

The stockpile disclosure, along with the rapid reduction of operational deployed warheads disclosed yesterday, the Obama administration is significantly strengthening the U.S. position at the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference.

Progress toward deep nuclear cuts and eventual nuclear disarmament would have been very difficult without disclosing the inventory of nuclear weapons.

FAS and others have long advocated disclosure and argued that keeping the size of the nuclear arsenal secret serves no real national security purpose in the post-Cold War era. Now that the size of the nuclear stockpile is no longer a secret, that dismantlement numbers are no longer secret, and the number of deployed strategic warheads is no longer a secret, the United States should also disclose the total number of strategic and non-strategic weapons in the stockpile.

Stockpile History and Forecast

When the Bush administration took office in 2001, the stockpile included 10,526 warheads. In June 2004, the NNSA announced a decision to cut the 2001 stockpile “nearly in half” by 2012. That goal was achieved five years early in December 2007, at which point the White House announced an additional cut of 15 percent by 2012. Once these reductions are completed, the stockpile will include approximately 4,600 warheads, a force level last seen in 1956.

.

The Obama administration has not yet announced a decision to further reduce the nuclear stockpile, but there are several hints in the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) that it intends to reduce the stockpile further. The NPR states that the United States will be “significantly reducing the size of the technical hedge overall,” a reference to the thousands of non-deployed but intact warheads kept in storage for potential upload back unto missiles and bombers in case of Russia or China building up and to replace warheads that develop technical problems.

The NPR also states that the number of warheads awaiting dismantlement “will increase as weapons are removed from the stockpile under New START.” Since the New START does not require removing weapons from the stockpile – only from strategic delivery vehicles – this is also a reference to further stockpile reductions. One senior official told me that some of these reductions would be made soon.

But the “major reductions in the nuclear stockpile” promised by the NPR appear to be conditioned on “implementation of the Stockpile Stewardship Program and the nuclear infrastructure investments….” If Congress approves these investments, some “hedge” warheads can “be retired along with other stockpile reductions planned over the next decade.”

| Estimated U.S. Nuclear Weapons Inventories, 2010 |

|

| The nuclear stockpile is only a portion of the total U.S. inventory of nuclear weapons. We estimate the total number of assembled warheads is close to 9,600, probably a little less given ongoing dismantlement of retired warheads. |

.

Stockpile Warhead Categories

The stockpile contains many subcategories of warheads. There are two overall categories: active and inactive. The active category includes two subcategories: deployed warheads on missiles and bomber bases and nondeployed warheads in the “Responsive Force” for uploading in case of Russia or China building up or technical failure of deployed warheads. The inactive category includes warheads without limited-life components (such as tritium) in long-term storage.

But since the stockpile is always in a flux with warheads being moved between platforms and maintenance, each of these subcategories have numerous other categories that relate to the readiness of the warheads. According to information obtained from the government, there are four readiness state (RS) categories related to warhead functions:

RS-A: Warheads that may be used for possible wartime employment.

RS-B: Warheads intended to be used for logistical purposes (e.g., LLC exchange (LLCE), repairs, surveillance, transportation, etc.).

RS-C: Warheads intended to be used for QUART replacement.

RS-D: Warheads intended to be used for reliability replacement.

There are also five readiness state categories that relate to the warhead location an maintenance requirements:

RS-1: Active stockpile warheads intended to be located primarily on launchers or at an operational base.

RS-2: Active stockpile warheads intended to be located primarily at either an operational base or depot.

RS-3: Inactive stockpile warheads intended to be located primarily at a depot, have the LLCs removed as soon as logistically practical, require refurbishment, and require reliability and safety assessments.

RS-4: Inactive stockpile warheads intended to be located primarily at a depot, have the LLCs removed as soon as logistically practical, do NOT require refurbishment, but do require reliability and safety assessments.

RS-5: Inactive stockpile warheads intended to be located at a depot, have LCCs removed as soon as logistically practical, do NOT require refurbishment, do NOT require reliability assessments, but do require safety assessments.

Other Countries

The disclosure puts pressure of the other nuclear weapon states to reciprocate. Nuclear weapon states that do not disclose the size of their nuclear arsenals will now be seen as secretive and obstructing nuclear transparency and progress towards deep cuts and eventually disarmament. Some nuclear countries have given ballpark numbers:

The Chinese Foreign Ministry declared in a fact sheet in 2004 that, “Among the nuclear-weapon states, China. . . possesses the smallest nuclear arsenal.” That suggested fewer than 200 operationally available warheads, as declared by Britain in 1998. (See also the latest Nuclear Notebook on China.)

Britain further declared in 2007 that it would “reduce the maximum number of operationally available warheads from fewer than 200 to fewer than 160” by 2007. This suggests that a limited inventory of non-operationally available warheads exists.

France declared in 2008 that its “arsenal will include fewer than 300 nuclear warheads” following a reduction of the bombers. French president Nicolas Sarkozy claimed France was “completely transparent because it has no other weapons beside those in its operational arsenal.” Nonetheless, a small number of spares or warheads undergoing surveillance probably exist in additional to those in the “operational arsenal.” (See also the latest Nuclear Notebook on France.)

Russia has not, to my knowledge, disclosed anything about the size of its stockpile. (See latest Nuclear Notebook on Russia.)

Dismantlements

The Pentagon also released warhead dismantlement numbers back to 1995. I’ll blog later on what that means.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Treaty Has New Counting

|

| An important new treaty reduces the limit for deployed strategic warheads but not the number. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

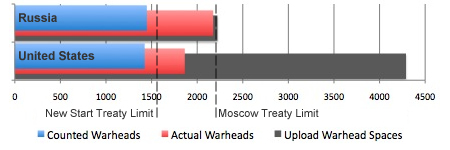

The White House has announced that it has reached agreement with Russia on the New START Treaty. Although some of the documents still have to be finished, a White House fact sheet describes that the treaty limits the number of warheads on deployed ballistic missiles and long-range bombers on both sides to 1,550 and the number of missiles and bombers capable of launching those warheads to no more than 700.

The long-awaited treaty is a vital symbol of progress in U.S.-Russian relations and an important additional step in the process of reducing and eventually perhaps even achieving the elimination nuclear weapons. It represents a significant arms control milestone that both countries should ratify as soon as possible so they can negotiate deeper cuts.

Yet while the treaty reduces the legal limit for deployed strategic warheads, it doesn’t actually reduce the number of warheads. Indeed, the treaty does not require destruction of a single nuclear warhead and actually permits the United States and Russia to deploy almost the same number of strategic warheads that were permitted by the 2002 Moscow Treaty.

The major provisions of the New START Treaty are:

- 1,550 deployed strategic warheads: Warheads on deployed ICBMs and deployed SLBMs count toward this limit and each deployed heavy bomber equipped for nuclear armaments counts as one warhead toward this limit.

- A limit of 700 deployed ICBMs, deployed SLBMs, and deployed heavy bombers equipped for nuclear armaments.

- A limit of 100 non-deployed ICBM launchers (silos), SLBM launchers (tubes), and heavy bombers equipped for nuclear armaments.

These limits don’t have to be met until 2017, and will remain in effect for three years until the treaty expires in 2020 (assuming ratification occurs this year). Once it is ratified, the 2002 Moscow Treaty (SORT) falls away.

Verification Extended

The most important part of the new treaty is that it extends a verification regime at least a decade into the future. The inspections and other verification procedures in this Treaty will be simpler and less costly to implement than the old START treaty, according to the White House.

This includes on-site inspections. Each side gets a total of 18 per year, ten of which are actual warhead counts of deployed missiles and the remaining eight being “Type 2” inspections of storage and dismantlement facilities.

Exchange of missile test telemetry data has been limited partly because it is not as necessary for verification as previously; there are other means for collecting this information. Even so, the treaty includes exchange of telemetry data for five test flights each year.

The Fine Print: Limits Versus Reductions

The White House fact sheet states that the new limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads is 74% lower than the 6,000 warhead limit of the 1991 START Treaty, and 30% lower than the 2,200 deployed strategic warhead limit of the 2002 Moscow Treaty.

That is correct, but the limit allowed by the treaty is not the actual number of warheads that can be deployed. The reason for this paradox is a new counting rule that attributes one weapon to each bomber rather than the actual number of weapons assigned to them. This “fake” counting rule frees up a large pool of warhead spaces under the treaty limit that enable each country to deploy many more warheads than would otherwise be the case. And because there are no sub-limits for how warheads can be distributed on each of the three legs in the Triad, the “saved warheads” from the “fake” bomber count can be used to deploy more warheads on fast ballistic missiles than otherwise.

| Under the New START Treaty That’s One Nuclear Bomb! |

|

| The New START Treaty counts each nuclear bomber as one nuclear weapon even though U.S. and Russian bombers are equipped to carry up to 6-20 weapons each. This display at Barksdale Air Base shows a B-52 with six Air Launched Cruise Missiles, four B-61-7 bombs, two B83 bombs, six Advanced Cruise Missiles (now retired), and eight Air Launched Cruise Missiles. Russian bombers can carry up to 16 nuclear weapons. |

.

The Moscow Treaty attributed real weapons numbers to bombers. The United States defined that weapons were counted as “operationally deployed” if they were “loaded on heavy bombers or stored in weapons storage areas of heavy bomber bases.” As a result, large numbers of bombs and cruise missile have been removed from U.S. bomber bases to central storage sites over the past five years, leaving only those bomber weapons that should be counted against the 2,200-warhead Moscow Treaty limit.

Since the new treaty attributes only one warhead to each bomber, it no longer matters if the weapons are on the bomber bases or not; it’s the bomber that counts not the weapons. As a result, a base with 22 nuclear tasked B-52 bombers will only count as 22 weapons even though there may be hundreds of weapons on the base.

According to U.S. officials, the United States wanted the New START Treaty to count real warhead numbers for the bombers but Russia refused to prevent on-site inspections of weapons storage bunkers at bomber bases. As a result, the 36 bombers at the Engels base near Saratov will count as only 36 weapons even though there may be hundreds of weapons at the base.

If the New START Treaty counting rule is used on today’s postures, then the United States currently only deploys some 1,650 strategic warheads, not the actual 2,100 warheads; Russia would be counted as deploying about 1,740 warheads instead of its actual 2,600 warheads. In other words, the counting rule would “hide” approximately 450 and 860 warheads, respectively, or 1,310 warheads. That’s more warheads that Britain, China, France, India, Israel, and Pakistan possess combined!

| Dodging The Issue |

|

|

Update March 30: Ellen Tauscher, the U.S. Under Secretary for Arms Control and International Security, was asked at a press briefing to explain the rationale behind the “fake” bomber warhead counting rule, but dodged the issue: “Well, I think what we want to do right now is talk about why this is an important treaty….” Increased transparency of bomber weapons would greatly improve the importance of the new treaty; the U.S. and Russia have more bomber warheads than the total nuclear weapon inventory of all other nuclear weapon states combined. If they have to use an arbitrary bomber warhead number because it’s too hard to verify, why chose 1? Why not 10 (as START I did) or 12, the medium loading capacity of U.S. and Russian bombers? |

The paradox is that with the “fake” bomber counting rule the United States and Russia could, if they chose to do so, deploy more strategic warheads under the New START Treaty by 2017 than would have been allowed by the Moscow Treaty by 2012.

Force Structure Changes

How the new treaty and the “fake” counting rule will affect U.S. and Russian nuclear force structures depends on decisions that will be made in the near future. In the negotiations both Russia and the United States resisted significant changes to their nuclear forces structures.

Russia resisted restrictions on warheads numbers to keep some degree of parity with the United States. It achieved this by the “fake” bomber weapon count and the delivery platform limit that is higher than what Russia deploys today. Under the New START Treaty, Russia can deploy more strategic warheads on its ballistic missiles than it would have been able to under the Moscow Treaty, although it probably won’t do so due to retirement of older systems. It can continue all its current and planned force structure modernizations.

The United States resisted restrictions on its upload capability, which it achieved by the high limit on delivery platforms. The “fake” bomber count enables more weapons to be deployed on ballistic missiles and more weapons to be retained at bomber bases than would have been possible under the Moscow Treaty. The SLBM-heavy (in terms of warheads) U.S. posture “eats up” a large portion of the 1,550 warhead limit, so the U.S. Nuclear Posture Review soon to be completed will probably reduce the warhead loading on each SLBM, and possible cut about 100 missiles from the ICBM force. The incentive to limit bomber weapons further is gone with the new treaty, although it could happen for other reasons. All current and planned modernizations can continue.

Although Russia has thousands of extra weapons in storage, all its deployed missiles are thought to be loaded to near capacity. As a result, under the New START Treaty, Russia will have little upload capacity. The United States, on the other hand, has only a portion of its available warheads deployed and lots of empty spaces on its missiles. The large pool of reserve warheads available for potential upload creates a significant disparity in the two postures so it is likely that the Nuclear Posture Review will reduce the size of the reserve.

| Estimated U.S. and Russian Strategic Warheads, 2017 |

|

| Although the New START Treaty reduces the limit for deployed strategic warheads, a “fake” bomber weapon counting rule enables both countries to continue to deploy as many weapons as under the Moscow Treaty. A high limit for delivery vehicles protects a significant U.S. upload capacity, whereas Russia will have essentially none. Future force structure decisions might affect the exact numbers but this graph illustrates the paradox. |

.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The New START Treaty is an important achievement in restarting relations with Russia after the abysmal decline during the Bush administration. And extending and updating the important verification regime creates a foundation for transparency and confidence building.

The treaty will also, if ratified quickly and followed up by additional reductions, assist in strengthening the international nonproliferation regime and efforts to prevent other countries from developing nuclear weapons.

The United States and Russia must be careful not to “oversell” the treaty as creating significant reductions in nuclear arsenals and strategic delivery systems. Although the treaty reduces the limit, the achievement is undercut by a new counting rule that enables both countries to deploy as many strategic warheads as under the Moscow Treaty.

Indeed, the New START Treaty is not so much a nuclear reductions treaty as it is a verification and confidence building treaty. It is a ballistic missile focused treaty that essentially removes strategic bombers from arms control.

The good news is that a modest treaty will hopefully be easier to ratify.

Because the treaty protects current force structures rather than reducing them, it will inevitably draw increased attention to the large inventories of non-deployed weapons that both countries retain and can continue to retain under the new treaty. Whereas the United States force structure is large enough to permit uploading of significant numbers of reserve warheads, the Russian force is too small to provide a substantial upload capacity. Even with a significant production of new missiles, it is likely that Russia’s entire Triad will drop to around 400 delivery vehicles by 2017 – fewer than the United States has today in its ICBM leg alone. That growing disparity makes it imperative that the forthcoming U.S. Nuclear Posture Review reduces the number of delivery vehicles and reserve warheads.

To that end it is amazing to hear some people complaining that the U.S. deterrent is dilapidating and that the United States doesn’t gain anything from the New START Treaty. In the words of one senior White House official, the United States came away as a “clean winner.”

Because the treaty does not force significantly deeper reductions in the number of nuclear weapons compared with the Moscow Treaty, it is important that presidents Obama and Medvedev at the signing ceremony in Prague on 8 April commit to seeking rapid ratification and achieving additional and more drastic nuclear reductions.

See also Ivan Oelrich’s blog.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Changing the Nuclear Posture: moving smartly without leaping

Release of the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) is delayed once again. Originally due late last year, in part so it could inform the on-going negotiations on the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty Follow-on (START-FO), after a couple of delays it was supposed to be released today, 1 March, but last week word got out that it will be coming out yet another 2-4 weeks later. Some reports are that the delay reflects deep divisions within the administration over the direction of the NPR. That means that there is really only one person left whose opinion matters and that is the president.

We can only hope that President Obama makes clear that he meant what he said in Prague and elsewhere. This NPR is crucial. If it is incremental, if it relegates a world free of nuclear weapons to an inspiring aspiration, then we are stuck with our current nuclear standoff for another generation. This is the time to decisively shift direction. But we should not be paralyzed by thinking that the only movement available is a giant leap into the unknown. We need to move decisively in the right direction, sure, but we can do that in steps. (more…)