Empowering States for Resilient Infrastructure by Diffusing Federal Responsibility for Flood Risk Management

State and local failure to appropriately integrate flood risk into planning is a massive national liability – and a massive contributor to national debt. Though flooding is well recognized as a growing problem, our nation continues to address this threat through reactive, costly disaster responses instead of proactive, cost-saving investments in resilient infrastructure.

President Trump’s Executive Order (EO) on Achieving Efficiency Through State and Local Preparedness introduces a nationally strategic opportunity to rethink how state and local governments manage flood risk. The EO calls for the development and implementation of a National Resilience Strategy and National Risk Register, emphasizing the need for a decentralized approach to preparedness. To support this approach, the Trump Administration should mandate that state governments establish and fund flood infrastructure vulnerability assessment programs as a prerequisite for accessing federal flood mitigation funds. Modeled on the Resilient Florida Program, this policy would both improve coordination among federal, state, and local governments and yield long-term cost savings.

Challenge and Opportunity

President Trump’s aforementioned EO signals a shift in national infrastructure policy. The order moves away from a traditional “all-hazards” approach to a more focused, risk-informed strategy. This new framework prioritizes proactive, targeted measures to address infrastructure risks. It also underscores the crucial role of state and local governments in enhancing national security and building a more resilient nation—emphasizing that preparedness is most effectively managed at subnational levels, with the federal government providing competent, accessible, and efficient support.

A core provision of the EO is the creation of a National Resilience Strategy to guide efforts in strengthening infrastructure against risks. The order mandates a comprehensive review of existing infrastructure policies, with the goal of recommending risk-informed approaches. The EO also directs development of a National Risk Register to document and assess risks to critical infrastructure, thereby providing a foundation for informed decision-making in infrastructure planning and funding.

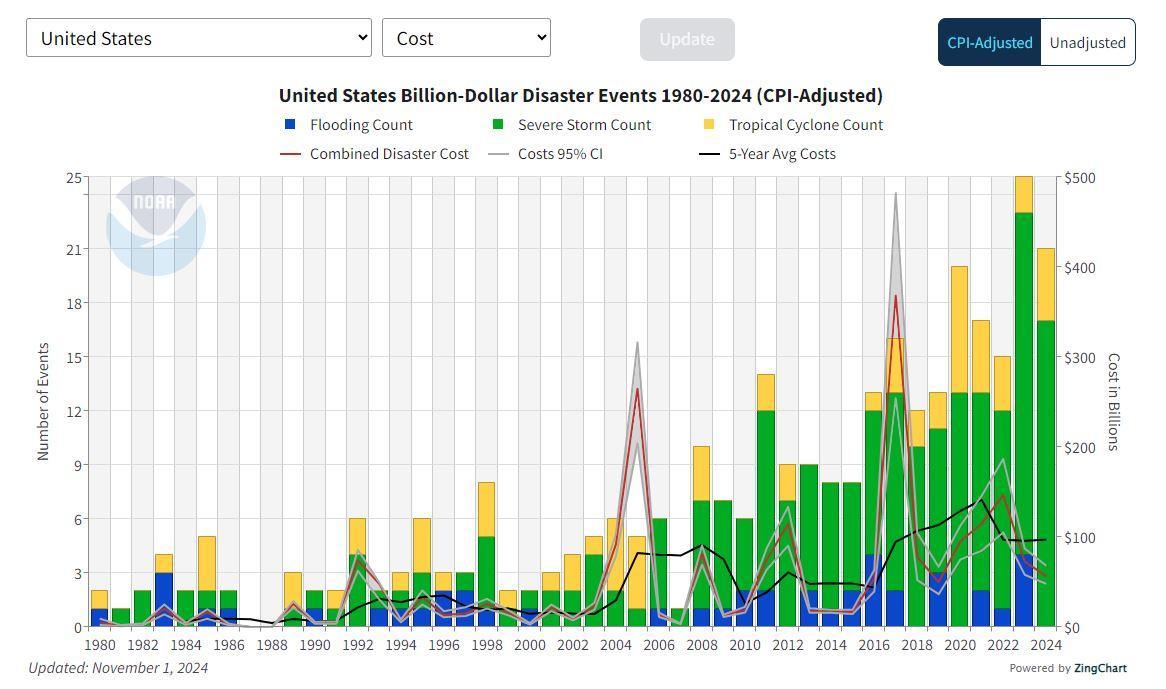

In carrying out these directives, the risks of flooding on critical infrastructure must not be overlooked. The frequency and cost of weather- and flood-related disasters are increasing nationwide due to a combination of heightened exposure (infrastructure growth due to population and economic expansion) and vulnerability (susceptibility to damage). As shown in Figure 1, the cost of responding to disaster events such as flooding, severe storms, and tropical cyclones has risen exponentially since 1980, often reaching hundreds of billions of dollars annually.

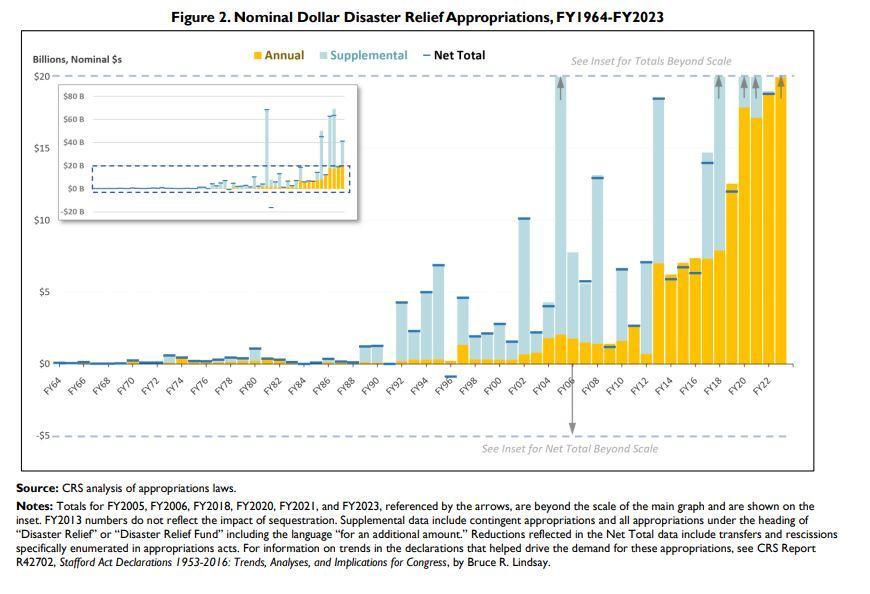

Financial implications for the U.S. budget have also grown. As illustrated in Figure 2, federal appropriations to the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) have surged in recent decades, driven by the demand for critical response and recovery services.

Infrastructure across the United States remains increasingly vulnerable to flooding. Critical infrastructure – including roads, utilities, and emergency services – is often inadequately equipped to withstand these heightened risks. Many critical infrastructure systems were designed decades ago when flood risks were lower, and have not been upgraded or replaced to account for changing conditions. The upshot is that significant deficiencies, reduced performance, and catastrophic economic consequences often result when floods occur today.

The costs of bailing out and patching up this infrastructure time and time again under today’s flood risk environment have become unsustainable. While agencies like the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) maintain and publish extensive flood risk datasets, no federal requirements mandate state and local governments to integrate this data with critical infrastructure data through flood infrastructure vulnerability assessments. This gap in policy demonstrates a disconnect between federal, state, and local efforts to protect critical infrastructure from flooding risks.

The only way to address this disconnect, and the recurring cost problem, is through a new paradigm – one that proactively integrates flood risk management and infrastructure resilience planning through mandatory, comprehensive flood infrastructure vulnerability assessments (FIVAs).

Multiple state programs demonstrate the benefits of such assessments. Most notably, the Resilient Florida Program, established in 2021, represents a significant investment in enhancing the resilience of critical infrastructure to flooding, rainfall, and extreme storms. Section 380.093 of the Florida Statutes requires all municipalities and counties across the state to conduct comprehensive FIVAs in order to qualify for state flood mitigation funding. These assessments identify risks to publicly owned critical and regionally significant assets, including transportation networks; evacuation routes; critical infrastructure; community and emergency facilities; and natural, cultural, and historical resources. To support this requirement, the Florida Legislature allocated funding to ensure municipalities and counties could complete the FIVAs. The findings then quickly informed statewide flood mitigation projects, with over $1.8 billion invested between 2021 and 2024 to reduce flooding risks across 365 implementation projects.

To support the National Resilience Strategy and Risk Register, the Trump Administration should consider leveraging Florida’s model on a national scale. By requiring all states to conduct FIVAs, the federal government can limit its financial liability while advancing a more efficient and effective model of flood resilience that puts states and localities at the fore.

Rather than relying on federal funds to conduct these assessments, the federal government should implement a policy mandate requiring state governments to establish and fund their own FIVA programs. This mandate would diffuse federal responsibility of identifying flood risks to the state and local levels, ensuring that the assessments are tailored to the unique geographic conditions of each region. By decentralizing flood risk management, states can adopt localized strategies that better reflect their specific vulnerabilities and priorities.

These state-led assessments would, in turn, provide a critical foundation for informed decision-making in national infrastructure planning, ensuring that federal investments in flood mitigation and resilience are targeted and effective. Specifically, the federal government would use the compiled data from state and local assessments to prioritize funding for projects that address the most pressing infrastructure vulnerabilities. This would enable federal agencies to allocate resources more efficiently, directing investments to areas with the highest risk exposure and the greatest potential for cost-effective mitigation. A standardized federal FIVA framework would ensure consistency in data collection, risk evaluation, and reporting across states. This would facilitate better coordination among federal, state, and local entities while improving integration of flood risk data into national infrastructure planning.

By implementing this strategy, the Trump Administration would reinforce the principle of shared responsibility in disaster preparedness and resilience, encouraging state and local governments to take the lead in safeguarding critical infrastructure. State-led FIVAs would also deliver significant long-term cost savings, given that investments in resilient infrastructure yield a substantial return on investment. (Studies show a 1:4 ratio of return on investment, meaning every dollar spent on resilience and preparedness saves $4 in future losses.) Finally, requiring FIVAs would build a more resilient nation, ensuring that communities are better equipped to withstand the increasing challenges posed by flooding and that federal investments are safeguarded.

Plan of Action

The Trump Administration can support the National Resilience Strategy and National Risk Register by taking the following actions to promote state-led development and adoption of FIVAs.

Recommendation 1. Create a Standardized FIVA Framework.

President Trump should direct his Administration, through an interagency FIVA Task Force, to create a standardized FIVA framework, drawing on successful models like the Resilient Florida Program. This framework will establish consistent methodologies for data collection, risk evaluation, and reporting, ensuring that assessments are both thorough and adaptable to state and local needs. An essential function of the task force should be to compile and review all existing federally maintained datasets on flood risks, which are maintained by agencies such as FEMA, NOAA, and USACE. By centralizing this information and providing streamlined access to high-quality, accurate data on flood risks, the task force will reduce the burden on state and local agencies.

Recommendation 2. Create Model Legislation.

The FIVA Task Force, working with leading organizations such as the American Flood Coalition (AFC), and Association of State Floodplain Managers (ASFPM), should create model legislation that state governments can adapt and enact to require local development and adoption of FIVAs. This legislation should outline the requirements for conducting assessments, including which infrastructure types need to be evaluated, what flood risk scenarios need to be considered, and how the findings must be used to guide infrastructure planning and investments.

Recommendation 3. Spur Uptake and Establish Accountability and Reporting Mechanisms.

Once the FIVA framework and model legislation are created, the Administration should require states to enact FIVA laws in order to be eligible for receiving federal infrastructure funding. This requirement should be phased in on clear and feasible timelines, with clear criteria for what provisions FIVA laws must include. Regular reporting requirements should also be established, whereby states must provide updates on their progress in conducting FIVAs and integrating findings into infrastructure planning. Updates should be captured in a public tracking system to ensure transparency and hold states accountable for completing assessments on time. Federal agencies should evaluate federal infrastructure funding requests based on the findings from state-led FIVAs to ensure that investments are targeted at areas with the highest flood risks and the greatest potential for resilience improvements.

Recommendation 4. Use State and Local Data to Shape Federal Policy.

Ensure that the results of state-led FIVAs are incorporated into future updates of the National Resilience Strategy and Risk Register, as well as other relevant federal policy and programs. This integration will provide a comprehensive view of national infrastructure risks and help inform federal decision-making and resource allocation for disaster preparedness and response.

Conclusion

The Trump Administration’s EO on Achieving Efficiency Through State and Local Preparedness opens the door to comprehensively rethink how we as a nation approach planning, disaster risk management, and resilience. Scaling successful approaches from states like Florida can deliver on the goals of the EO in at least five ways:

- Empowering state and local governments to take the lead in managing flood risks, ensuring that assessments and strategies are more reflective of local needs and conditions.

- Distributing the responsibility for identifying and mitigating flood risks across all levels of government, reducing the burden on the federal government and allowing more tailored, efficient responses.

- Reducing disaster response costs by prioritizing proactive, risk-informed planning over reactive recovery efforts, leading to long-term savings.

- Strengthening infrastructure resilience by making vulnerability assessments a condition for federal funding, driving investments that protect communities from flooding risks.

- Fostering greater accountability at the state and local levels, as governments will be directly responsible for ensuring that infrastructure is resilient to flooding, leading to more targeted and effective investments.

“Melbourne Florida Flooding” by highlander411 is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

- Several states have enacted policies advancing FIVAs or resilience programming, demonstrating this type of program could readily achieve bipartisan support.

The Resilient Florida Program, established in 2021, marks the state’s largest investment in preparing communities for the impacts of intensified storms and flooding. This program includes mandates and grants to analyze, prepare for, and implement resilience projects across the state. A key element of the program is the required vulnerability assessment, which focuses on identifying risks to critical infrastructure. Counties and municipalities must analyze the vulnerability of regionally significant assets and submit geospatial mapping data to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP). This data is used to create a comprehensive, statewide flooding dataset, updated every five years, followed by an annual Resilience Plan to prioritize and fund critical mitigation projects.

In Texas, the State Flood Plan, enacted in 2019, initiated the first-ever regional and state flood planning process. This legislation established the Flood Infrastructure Fund to support financing for flood-related projects. Regional flood planning groups are tasked with submitting their regional flood plans to the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB), starting in January 2023 and every five years thereafter. A central component of these plans is identifying vulnerabilities in communities and critical facilities within each region. Texas has also developed a flood planning data hub with minimum geodatabase standards to ensure consistent data collection across regions, ultimately synthesizing this information into a unified statewide flood plan.

The Massachusetts Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness (MVP) Program, established in 2016, requires all state agencies and authorities, and all cities and town, to assess vulnerabilities and adopt strategies to increase the adaptive capacity and resilience of critical infrastructure assets. The Massachusetts model reflects an incentive-based approach that encourages municipalities to conduct vulnerability assessments and create actionable resilience plans with technical assistance and funding. The state awards communities with funding to complete vulnerability assessments and develop action-oriented resilience plans. Communities that complete the MVP program become certified as an MVP community and are eligible for grant funding and other opportunities.

- Infrastructure vulnerability assessments differ from federally mandated hazard mitigation planning programs in both scope and focus. While both aim to enhance resilience, they target different aspects of risk management.

Infrastructure vulnerability assessments are highly specific, concentrating on the resilience of individual critical infrastructure systems—such as water supply, transportation networks, energy grids, and emergency response systems. These assessments analyze the specific vulnerabilities of these assets to both acute shocks, such as extreme weather events or floods, and chronic stressors, such as aging infrastructure. The process typically involves detailed technical analyses, including simulations, modeling, and system-level evaluations, to identify weaknesses in each asset. The results inform tailored, asset-specific interventions, like reinforcing flood barriers, upgrading infrastructure, or improving emergency response capacity. These assessments are focused on ensuring that essential systems are resilient to specific risks, and they typically involve detailed contingency planning for each identified vulnerability.

In contrast, federally mandated hazard mitigation planning, such as FEMA’s programs under the Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000, focuses on community-wide risk reduction. These programs aim to reduce overall exposure to natural hazards, like floods, wildfires, or earthquakes, by developing broad strategies that apply to entire communities or regions. Hazard mitigation planning involves public input, policy changes, and community-wide infrastructure improvements, which may include measures like zoning regulations, public awareness campaigns, or building codes that aim to reduce vulnerability on a large scale. While these plans may identify specific hazards, the solutions they propose are generally community-focused and may not address the nuanced vulnerabilities of individual infrastructure systems. Rather than offering a deep dive into the resilience of specific assets, hazard mitigation planning focuses on reducing overall risk and improving long-term resilience for the community as a whole.

- A proven methodology can be drawn from the Resilient Florida Program’s Standard Vulnerability Assessment Scope of Work Guidance. This methodology integrates geospatial mapping data with modeling outputs for a range of flood risks, including storm surge, tidal flooding, rainfall, and compound flooding. Communities overlay this flood risk data with their local infrastructure information – such as roads, utilities, and bridges – to identify vulnerable assets and prioritize resilience strategies.

For the nationwide mandate, this framework can be adapted, with technical assistance from federal agencies like FEMA, NOAA, and USACE to ensure consistency across regions and the integration of up-to-date flood risk data. FEMA could assist localities in adopting this methodology, ensuring that their vulnerability assessments are comprehensive and aligned with the latest flood risk data. This approach would help standardize assessments across the country while allowing for region-specific considerations, ensuring the mandate’s effectiveness in building resilience across the local, state, and national levels.

- This requirement will diffuse the responsibility of flood risk management to state and local governments by requiring them to take the lead in conducting FIVAs. Under this approach, the federal government will shift from being the primary entity responsible for identifying flood risks to a more supportive role, providing resources and guidance to state and local governments.

State governments will be required to establish and fund their own FIVAs, ensuring that each region’s unique geographic, climatic, and socioeconomic factors are considered when identifying and addressing flood risks. By decentralizing the process, states can tailor their strategies to local needs, which improves the efficiency of flood risk management efforts.

Local governments will also play a key role by implementing these assessments at the community level, ensuring that critical infrastructure is evaluated for its vulnerability to flooding. This will allow for more targeted interventions and investments that reflect local priorities and risks.

The federal government will use the data from these state and local assessments to prioritize funding and allocate resources more efficiently, ensuring that infrastructure resilience projects address the highest flood risks with the greatest potential for long-term savings.

Enhancing Local Capacity for Disaster Resilience

Across the United States, thousands of communities, particularly rural ones, don’t have the capacity to identify, apply for, and manage federal grants. And more than half of Americans don’t feel that the federal government adequately takes their interests into account. These factors make it difficult to build climate resilience in our most vulnerable populations. AmeriCorps can tackle this challenge by providing the human power needed to help communities overcome significant structural obstacles in accessing federal resources. Specifically, federal agencies that are part of the Thriving Communities Network can partner with the philanthropic sector to place AmeriCorps members in Community Disaster Resilience Zones (CDRZs) as part of a new Resilient Communities Corps. Through this initiative, AmeriCorps would provide technical assistance to vulnerable communities in accessing deeply needed resources.

There is precedent for this type of effort. AmeriCorps programming, like AmeriCorps VISTA, has a long history of aiding communities and organizations by directly helping secure grant monies and by empowering communities and organizations to self-support in the future. The AmeriCorps Energy Communities is a public-private partnership that targets service investment to support low-capacity and highly vulnerable communities in capitalizing on emerging energy opportunities. And the Environmental Justice Climate Corps, a partnership between the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and AmeriCorps, will place AmeriCorps VISTA members in historically marginalized communities to work on environmental justice projects.

A new initiative targeting service investment to build resilience in low-capacity communities, particularly rural communities, would help build capacity at the local level, train a new generation of service-oriented individuals in grant writing and resilience work, and ensure that federal funding gets to the communities that need it most.

Challenge and Opportunity

A significant barrier to getting federal funding to those who need it the most is the capacity of those communities to search and apply for grants. Many such communities lack both sufficient staff bandwidth to apply and search for grants and the internal expertise to put forward a successful application. Indeed, the Midwest and Interior West have seen under 20% of their communities receive competitive federal grants since the year 2000. Low-capacity rural communities account for only 3% of grants from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)’s flagship program for building community resilience. Even communities that receive grants often lack the capacity for strong grant management, which can mean losing monies that go unspent within the grant period.

This is problematic because low-capacity communities are particularly vulnerable to natural disasters from flooding to wildfires. Out of the nearly 8,000 most at-risk communities with limited capacity to advocate for resources, 46% are at risk for flooding, 36% are at risk for wildfires, and 19% are at risk for both.

Ensuring communities can access federal grants to help them become more climate resilient is crucial to achieving an equitable and efficient distribution of federal monies, and to building a stronger nation from the ground up. These objectives are especially salient given that there is still a lot of federal money available through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) that low-capacity communities can tap into for climate resilience work. As of April 2024, only $60 billion out of the $145 billion in the IRA for energy and climate programs had been spent. For the IIJA, only half of the nearly $650 billion in direct formula funding had been spent.

The Biden-Harris Administration has tried to address the mismatch between federal resilience funding and community capacity in a variety of ways. The Administration has deployed resources for low-capacity communities, agencies tasked with allocating funds from the IRA and IIJA have held information sessions, and the IRA and IIJA contain over a hundred technical assistance programs. Yet there still is not enough support in the form of human capacity at the local level to access grants and other resources and assistance provided by federal agencies. AmeriCorps members can support communities in making informed decisions, applying for federal support, and managing federal financial assistance. Indeed, state programs like the Maine Climate Corps, include aiding communities with both resilience planning and emergency management assistance as part of their focus. Evening the playing field by expanding deployment of human capital will yield a more equitable distribution of federal monies to the communities that need it the most.

AmeriCorps’ Energy Communities initiative serves as a model for a public-private partnership to support low-capacity communities in meeting their climate resilience goals. Over a three-year period, the program will invest over $7.8 million from federal agencies and philanthropic dollars to help communities designated by the Interagency Working Group on Coal & Power Plant Communities & Economic Revitalization on issues revolving around energy opportunity, environmental cleanup, and economic development to help communities capitalize on emerging energy opportunities.

There is an opportunity to replicate this model towards resilience. Specifically, the next Administration can leverage the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA’s) Community Disaster Resilience Zone (CDRZ) designations to target AmeriCorps support to the communities that need it most. Doing so will not only build community resilience, but will help restore trust in the federal government and its programs (see FAQ).

Plan of Action

The next administration can support vulnerable communities in building climate resilience by launching a new Resilient Communities Corps through AmeriCorps. The initiative can be launched through a three-part Plan of Action: (1) find a philanthropic partner to fund AmeriCorps placements in CDRZs, (2) engage federal agencies that are part of the Thriving Communities Network to provide resilience training and support to Corps members, and (3) use the CDRZ designations to help guide where AmeriCorps members should be placed.

Recommendation 1. Secure philanthropic funding

American service programs have a history of utilizing philanthropic monies to fund programming. The AmeriCorps Energy Communities is funded with philanthropic monies from Bloomberg Philanthropies. California Volunteers Fund (CVF), the Waverly Street Foundation, and individual philanthropists helped fund the state Climate Corps. CVF has also provided assistance and insights for state Climate Corps officials as they develop their programs.

A new Resilient Communities Corps under the AmeriCorps umbrella could be funded through one or several major philanthropic donors, and/or through grassroots donations. Widespread public support for AmeriCorps’ ACC that transcends generational and party lines presents the opportunity for new grassroots donations to supplement federal monies allocated to the program along with tapping the existing network of foundations, individuals, companies, and organizations that have provided past donations. The Partnership for the Civilian Climate Corps (PCCC), which has had a history of collaborating with the ACC’s federal partners, would be well suited to help spearhead this grassroots effort.

America’s Service Commissions (ASC), which represents state service commissions, can also help coordinate with state service commissions to find local philanthropic monies to fund AmeriCorps work in CDRZs. There is precedent for this type of fundraising. Maine’s state service commission was able to secure private monies for one Maine Service Fellow. The fellow has since worked with low-capacity communities in Maine on climate resilience. ASC can also work with state service commissions to identify current state, private, and federally funded service programming that could be tapped to work in CDRZs or are currently working in CDRZs. This will help tie in existing local service infrastructure.

Recommendation 2. Engage federal agencies participating in the Thriving Communities Network and the American Climate Corps (ACC) interagency working group.

Philanthropic funding will be helpful but not sufficient in launching the Resilient Communities Corps. The next administration should also engage federal agencies to provide AmeriCorps members participating in the initiative with training on climate resilience, orientations and points of contact for major federal resilience programs, and, where available, additional financial support for the program. The ACC’s interagency working group has centered AmeriCorps as a multiagency initiative that has directed resources and provides collaboration in implementing AmeriCorps programming. The Resilient Communities Corps will be able to tap into this cross-agency collaboration in ways that align with the resilience work already being done by partnership members.

There are currently four ACC programs that are funded through cooperation with other federal agencies. These are the Working Lands Climate Corps with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s Natural Resources and Conservation Service, AmeriCorps NCCC Forest Corps with the USDA Forest Service, Energy Communities AmeriCorps with the Department of Interior and the Department of Commerce, and the Environmental Justice Corps, which was announced in September 2024 and will launch in 2025, with the EPA. The Resilient Communities Corps could be established as a formal partnership with one or more federal agencies as funding partners.

In addition, the Resilient Communities Corps can and should leverage existing work that federal agencies are doing to build community capacity and enhance community climate resilience. For instance, USDA’s Rural Partners Network helps rural communities access federal funding while the EPA’s Environmental Justice Thriving Communities Technical Assistance Centers Program provides training and assistance for communities to build the capacity to navigate, develop proposals, and manage federal grants. The Thriving Communities Network provides a forum for federal agencies to provide technical assistance to communities trying to access federal monies. Corps members, through the network, can help federal agencies provide communities they are working with building capacity to access this technical assistance.

Recommendation 3. Use CDRZ designations and engage with state service commissions to guide Resilient Communities Corps placements

FEMA, through its National Risk Index, has identified communities across the country that are most vulnerable to the climate crisis and need targeted federal support for climate resilience projects. CDRZs provide an opportunity for AmeriCorps to identify low-capacity communities that need their assistance in accessing this federal support. With assistance from partner agencies and philanthropic dollars, the AmeriCorps can fund Corps members to work in these designated zones to help drive resources into them. As part of this effort, the ACC interagency working group should be broadened to include the Department of Homeland Security (which already sponsors FEMA Corps).

In 2024, the Biden-Harris Administration announced Federal-State partnerships between state service commissions and the ACC. This partnership with state service commissions will help AmeriCorps and partner agencies identify what is currently being done in CDRZs, what is needed from communities, and any existing service programming that could be built up with federal and philanthropic monies. State service commissions understand the communities they work with and what existing programming is currently in place. This knowledge and coordination will prove invaluable for the Resilient Communities Corps and AmeriCorps more broadly as they determine where to allocate members and what existing service programming could receive Resilient Communities Corps designation. This will be helpful in deciding where to focus initial/pilot Resilient Communities Corps placements.

Conclusion

A Resilient Communities Corps presents an incredible opportunity for the next administration to support low-capacity communities in accessing competitive grants in CDRZ-designated areas. It will improve the federal government’s impact and efficiency of dispersing grant monies by making grants more accessible and ensure that our most vulnerable communities are better prepared and more resilient in the face of the climate crisis, introduce a new generation of young people to grant writing and public service, and help restore trust in federal government programs from communities that often feel overlooked.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Funding for one AmeriCorps member in each of FEMA’s 483 designated Community Disaster Resilience Zones would cost around $14,500,000 per year. This is with an estimate of $30,000 per member. However, this figure will be subject to change due to overhead and living adjustment costs.

There are many communities that could benefit from additional support when it comes to building resilience. Headwater Economics, a research institute in Montana, has flagged that the CDRZ does not account for all low-capacity communities hampered in their efforts to become more climate resilient. But the CDRZ designation does provide a federal framework that can serve as a jumping-off point for AmeriCorps to begin to fill capacity gaps. These designations, identified through the National Risk Index, provide a clear picture for where federal, public and private monies are needed the most. These communities are some of the most vulnerable to climate change, lack the resources for resilience work, and need the human capacity to access them. Because of these reasons, the CDRZ communities provide the ideal and most appropriate area for the Resilient Communities Corps to first serve in.

Funding for national service programming, particularly for the ACC, has bipartisan support. 53% of likely voters say that national service programming can help communities face climate-related issues.

On the other hand, 53% of Americans also feel that the federal government doesn’t take into account “the interests of people like them.” ACC programming, like what Maine’s Climate Corps is doing in rural areas, can help reach communities and build support among Americans for government programs that can be at times met with hostility.

For example, in Maine, the small and politically conservative town of Dover-Foxcroft applied for and was approved to host a Maine Service Fellow (part of the Maine Climate Corps network) to help the local climate action committee to obtain funding for and implement energy efficiency programs. The fellow, a recent graduate from a local college, helped Dover-Foxcroft’s new warming/cooling emergency shelter create policies, organized events on conversations about climate change, wrote a report about how the county will be affected by climate change, and recruited locals at the Black Fly Festival to participate in energy efficiency programs.

Like the Maine Service Fellows, Resilient Communities Corps members will be integral members of the communities in which they serve. They will gather essential information about their communities and provide feedback from the ground on what is working and what areas need improvement or are not being adequately addressed. This information can be passed up to the interagency working groups that can then be relayed to colleagues administering the grants, improving information flow, and creating feedback channels to better craft and implement policy. It also presents the opportunity for representatives of those agencies to directly reach out to those communities to let them know they have been heard and proactively alert residents to any changes they plan on making.