American Rescue Plan Funding: A Playbook for Efficiently Getting the Lead Out

Summary

Lead is a neurotoxin that continues to harm communities across the country. Though new uses of lead in paint, gasoline, and pipes have been banned for several decades, lead in legacy products and materials remains in communities, posing an ongoing threat to human and economic development. Anywhere from 6 to 10 million residential lead service lines (LSLs), for instance, are still in use nationwide.

Funding included in American Rescue Plan (ARP) grant programs gives cities and states the opportunity to finally eradicate lead contamination in water lines. These steps outlined in this memo (and summarized in the figure below) represent a data- driven approach to rid American communities of the pernicious effects of lead contamination in water systems. This approach builds on research from the University of Michigan and subsequent implementation by BlueConduit in more than 50 cities in the United States and Canada.

Ensuring Good Governance of Carbon Dioxide Removal

Climate change is an enormous environmental, social, and economic threat to the United States. Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from burning fossil fuels and other industrial processes are a major driver of this threat. Even if the world stopped emitting CO2 today, the huge quantities of CO2 generated by human activity to date would continue to sit in the atmosphere and cause dangerous climate effects for at least another 1,000 years. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has reported that keeping average global warming below 1.5°C is not possible without the use of carbon dioxide removal (CDR).2 While funding and legislative support for CDR has greatly increased in recent years, the United States does not yet have a coordinated plan for implementing CDR technologies. The Department of Energy’s CDR task force should recommend a governance strategy for CDR implementation to responsibly, equitably, and effectively combat climate change by achieving net-negative CO2 emissions.

Challenge and Opportunity

There is overwhelming scientific consensus that climate change is a dangerous global threat. Climate change, driven in large part by human-generated CO2 emissions, is already causing severe flooding, drought, melting ice sheets, and extreme heat. These phenomena are in turn compromising human health, food and water security, and economic growth.

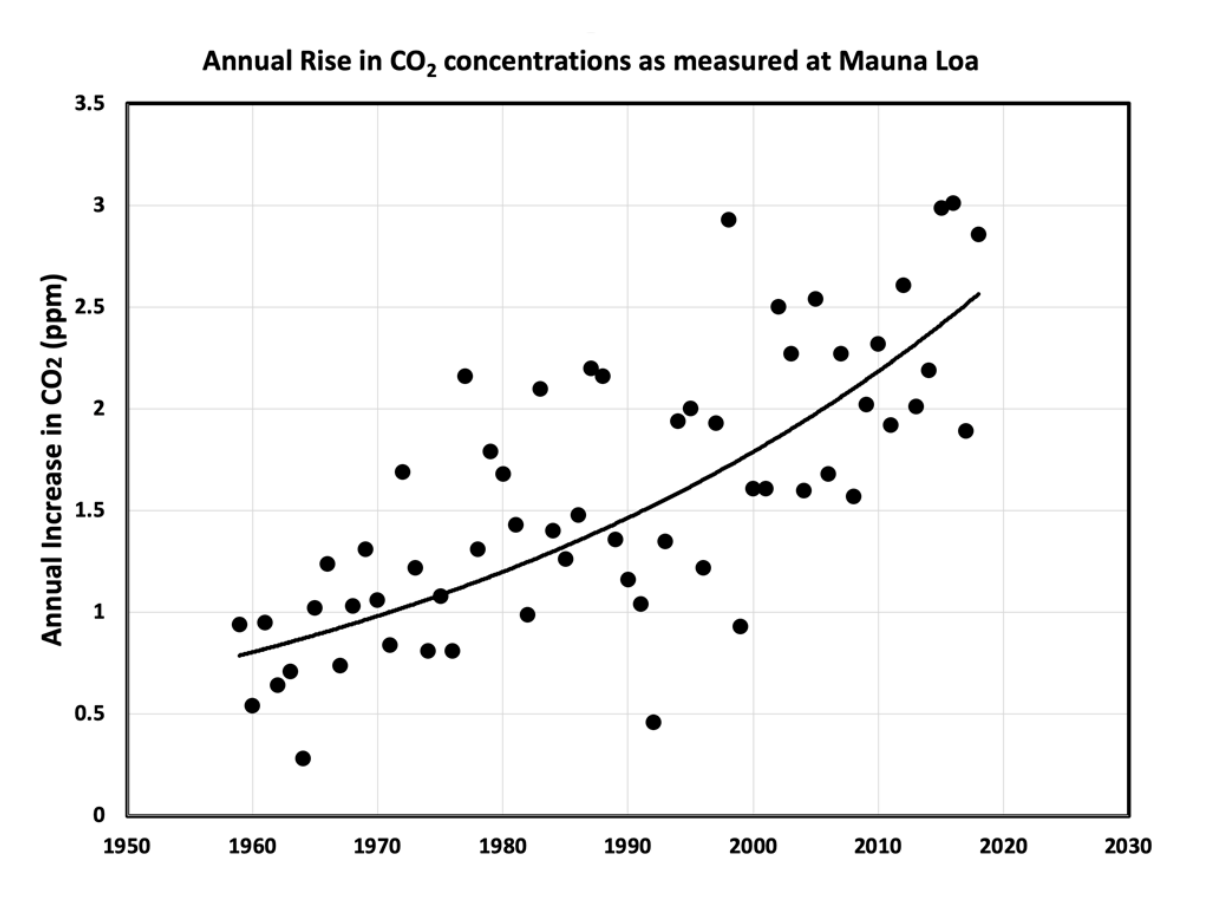

Figure 1. Data collected from observation stations show how noticeably atmospheric CO2 concentrations have risen over the past several decades. (Data compiled by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association; figure by Klaus S. Lackner.)

Morton, E.V. (2020). Reframing the Climate Change Problem: Evaluating the Political, Technological, and Ethical Management of Carbon Dioxide Emissions in the United States. Ph.D. thesis, Arizona State University.

CO2 concentrations are higher today than they have been at any point in the last 3 million years. The contribution of human activity is causing CO2 emissions to rise at an unprecedented rate — approximately 2% per year for the past several decades (Figure 1) — a rate that far outpaces the rate at which the natural world can adapt and adjust. A monumental global effort is needed to reduce CO2 emissions from human activity. But even this is not enough. Because CO2 can persist in the atmosphere for hundreds or thousands of years, CO2 already emitted will continue to have climate impacts for at least the next 1,000 years. Keeping the impacts of climate change to tolerable levels requires not only a suite of actions to reduce future CO2 emissions, but also implementation of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) strategies to mitigate the damage we have already done.

The IPCC defines CDR as “anthropogenic activities removing CO2 from the atmosphere and durably storing it in geological, terrestrial, or ocean reservoirs, or in products.” While becoming more energy efficient can reduce emissions and using renewable energy causes zero emissions, only CDR can achieve the “net negative” emissions needed to help restore climate stability.

Five companies around the world — two of which are based in the United States — have already begun commercializing a particular CDR technology called direct air capture. Climeworks is the most advanced company, and can already remove 900 tons of atmospheric CO2 per year at its plant in Switzerland. Though these companies have demonstrated that CDR technologies like direct air capture work, costs need to come down and capacity needs to expand for CDR to remove meaningful levels of past emissions from the atmosphere.

Thankfully, the Energy Act of 2020, a subsection of the 2021 Consolidated Appropriations Act, was passed into law in December 2020. This act creates a carbon removal research, development, and demonstration program within the Department of Energy. It also establishes a prize competition for pre-commercial and commercial applications of direct air capture technologies, provides grants for direct air capture and storage test centers, and creates a CDR task force.

The CDR task force will be led by the Secretary of Energy and include the heads of any other relevant federal agencies chosen by the Secretary. The task force is mandated to write a report that includes an estimate of how much excess CO2 needs to be removed from the atmosphere by 2050 to achieve net zero emissions, an inventory and evaluation of CDR approaches, and recommendations for policy tools that the U.S. government can use to meet the removal estimation and advance CDR deployment. This report will be used to advise the Secretary of Energy on next steps for CDR development and will be submitted to the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and the House of Representatives Committees on Energy and Commerce and Science, Space, and Technology.

The Biden administration has clearly shown its commitment to combating climate change by rejoining the Paris Agreement and signing several Executive Orders that take a whole-of-government approach to the climate crisis. The Energy Act complements these actions by advancing development and demonstration of CDR. However, the Energy Act does not address CDR governance, i.e., the policy tools necessary to efficiently and ethically steward CDR implementation. A proactive governance strategy is needed to ensure that CDR is used to repair past damage and support communities that have been disproportionately harmed by climate change — not as an excuse for the fossil-fuel industry and other major contributors to the climate crisis to continue dumping harmful greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The CDR task force should therefore leverage the crucial opportunity it has been given to shape future use of CDR by incorporating governance recommendations into its report.

Plan of Action

The Department of Energy’s CDR task force should consider recommending the following options in its final report. Taken together, these recommendations form the basis of a governance framework to ensure that CDR technologies are implemented in a way that most responsibly, equitably, and effectively addresses climate change.

Establish net-zero and net-negative carbon removal targets.

The Energy Act commendably directs the CDR task force to estimate the amount of CO2 that the United States must remove to become net zero by 2050. But the task force should not stop there. The task force should also estimate the amount of CO2 that the United States must remove to limit average global warming to 1.5°C (a target that will require net negative emissions) and estimate what year this goal could feasibly be achieved. Much like the National Ambient Air Quality Standards enforced by the Environmental Protection Agency, there should be a specific amount of CO2 that the United States should work toward removing to enhance environmental quality. This target could be based on how much CO2 the United States has put into the atmosphere to date and how much of that amount the United States should be responsible for removing. Both net-zero and net-negative removal targets should be preserved through legislation to continue progress beyond the Biden administration.

Design a public carbon removal service.

If carbon removal targets become law, the federal government will need to develop an organized way of removing and storing CO2 in order to reach those targets. Therefore, the CDR task force should also consider what it would take to develop a public carbon removal service. Just as waste disposal and sewage infrastructure are public services paid for by those that generate waste, industries would pay for the service of having their past and current CO2 emissions removed and stored securely. Revenue generated from a public carbon removal service could be reinvested into CDR technology, carbon storage facilities, maintenance of CDR infrastructure, environmental justice initiatives, and job creation. As the Biden administration ramps up its American Jobs Plan to modernize the country’s infrastructure, it should consider including carbon removal infrastructure. A public carbon removal service could materially contribute to the goals of expanding clean energy infrastructure and creating jobs in the green economy that the American Jobs Plan aims to achieve.

Planning the design and implementation of a public carbon removal service should be conducted in parallel with CDR technology development. Knowing what CDR technologies will be used may change how prize competitions and grant programs funded by the Energy Act are evaluated and how the CDR task force will prioritize its policy recommendations. The CDR task force should assess the CDR technology landscape and determine which technologies — including mechanical, agricultural, and ocean-based processes — are best suited for inclusion in a public carbon removal service. The assessment should be based on factors such as affordability, availability, and storage permanence. The assessment could also consider results from the research, development, and demonstration (RD&D) program and the prize competitions mandated by the Energy Act when making its determination. The task force should also recommend concrete steps towards getting a public carbon removal service up and running. Steps could include, for instance, establishing public-private partnerships with prize competition winners and other commercialized CDR companies.

Create a national carbon accounting standard.

The Energy Act directs the RD&D program to collaborate with the Environmental Protection Agency to develop an accounting framework to certify how much carbon different techniques can remove and how long that carbon can be stored. This may involve investigating the storage permanence of various carbon storage and utilization options. This may also involve creating a database of storage lifetimes for CDR products and processes and identification of CDR techniques best suited for attaining carbon removal targets. The task force could recommend to the Secretary of Energy that the framework becomes a standard. A national carbon accounting standard will be integral for achieving carbon removal targets and verifying removal through public service described above.

Ensure equity in CDR.

While much of the technical and economic aspects of carbon removal have been (or are being) investigated, questions related to equity remain largely unaddressed. The CDR task force should investigate and recommend policies and actions to ensure that carbon removal does not impose or exacerbate societal inequities, especially for vulnerable communities of color and low-income communities. Recommendations that the task force could explore include:

- Establishing a tax credit for investing in CDR on private land. This credit would be similar to existing credits for installing solar and selling electricity back to the grid. Some or all of proceeds from the credit should go to help communities previously harmed by environmental injustice (i.e., “environmental justice communities”).

- Launching a CDR technology deployment program that gives environmental justice communities a tax credit or other financial benefit for allowing a CDR technology to be deployed in their communities. This “hosting” compensation would be earmarked for local environmental remediation.

- Incentivizing design of CDR technologies that deliver co-benefits. For instance, planting trees not only helps remove carbon from the atmosphere but also creates shade, provides habitat, and helps mitigate urban heat-island effects. Industrial direct air capture plants can be surrounded by greenspace and art to create public parks.

- Interviewing environmental justice communities to understand their needs and how those needs could be met through strategic implementation of CDR.

Include CDR in international climate discussions.

Because CDR is a necessary part of any realistic strategy to keep average global warming to tolerable levels, CDR is a necessary part of future international discussions on climate change. The United States can take the lead by including CDR in its nationally determined contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement. The U.S. NDC most recently submitted in April 2021 does discuss increasing carbon sequestration through agriculture and oceans but could be even more aggressive by including a broader suite of CDR technologies (e.g., engineered direct air capture) and prioritizing pursuit of carbon-negative solutions. The CDR task force could recommend that the Department of Energy work with the Special Presidential Envoy for Climate and the Department of State Office of Global Change on (1) enhancing the NDC through CDR, and (2) developing climate-negotiation strategies intended to increase the use of CDR globally.

Conclusion

Global climate change has worsened to the point where simply reducing emissions is not enough. Even if all global emissions were to cease today, the climate impacts of the carbon we have dumped into the atmosphere would continue to be felt for centuries to come. The only solution to this problem is to achieve net-negative emissions by dramatically accelerating development and deployment of carbon dioxide removal (CDR). As one of the world’s biggest emitters, the United States has a responsibility to do all it can to tackle the climate crisis. And as one of the world’s technological and geopolitical leaders, the United States is well positioned to rise to the occasion, investing in CDR governance alongside the technical and economic aspects of CDR. The CDR task force can lead in this endeavor by advising the Secretary of Energy on an overall governance strategy and specific policy recommendations to ensure that CDR is used in an aggressive, responsible, and equitable manner.

Establish a $100M National Lab of Neurotechnology for Brain Moonshots

A rigorous scientific understanding of how the brain works would transform human health and the economy by (i) enabling design of effective therapies for mental and neurodegenerative diseases (such as depression and Alzheimer’s), and (ii) fueling novel areas of enterprise for the biomedical, technology, and artificial intelligence industries. Launched in 2013, the U.S. BRAIN (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) Initiative has made significant progress toward harnessing the ingenuity and creativity of individual laboratories in developing neurotechnological methods. This has provided a strong foundation for future work, producing advances like:

- 3-D microscopy and ultra-fast imaging that enables real-time observations of brain-cell activity in intact tissues: key data for understanding circuit principles underlying human behavior.

- A sophisticated genetic method that could be helpful for finding new druggable targets that could be engaged to manage pain effectively, helping avoid the risks and harms of opioid drug addiction.

- A portable backpack supporting (i) simultaneous recording from a stimulator implanted into a human subject’s brain (part of an early-stage clinical trial), (ii) measurement of other biomarkers, and (iii) recording of the subject’s positions and movements within their environment. This integrated and comprehensive dataset is helping researchers understand links between neural-circuit activity and behavior in humans.

However, pursuing these ambitious goals will require new approaches to brain research, at greater scale and scope.

Given the BRAIN Initiative’s momentum, this is the moment to expand the Initiative by investing in a National Laboratory of Neurotechnology (NLN) that would bring together a multidisciplinary team of researchers and engineers with combined expertise in physical and biomedical sciences. The NLN team would develop large-scale instruments, tools, and methods for recording and manipulating the activity of complex neural circuits in living animals or humans — studies that would enable us to understand how the brain works at a deeper, more detailed level than ever before. Specific high-impact initiatives that the NLN team could pursue include:

- Developing a multibeam, large-scale electron microscope to map the wiring of neural circuits.

- Determining the molecular components of each cell of the brain.

- Fabricating a diverse array of implantable and wearable devices.

- Conducting supercomputer-enabled mining of large datasets to support neurotechnology development.

The BRAIN Initiative currently funds small teams at existing research institutes. The natural next step is to expand the Initiative by establishing a dedicated center — staffed by a large, collaborative, and interdisciplinary team — capable of developing the high-cost, large-scale equipment needed to address complex and persistent challenges in the field of neurotechnology. Such a center would multiply the return on investment in brain research that the federal government is making on behalf of American taxpayers. Successful operation of a National Laboratory of Neurotechnology would require about $100 million per year.

To read a detailed vision for a National Laboratory of Neurotechnology, click here.

Support Electrification at Regional Airports to Preserve Competitiveness & Improve Health Outcomes

Summary

The Biden-Harris Administration, Congress, and state legislatures should adopt measures to reduce the substantial health and environmental impact of America’s 5,000+ public airports while improving the competitiveness of American aviation. Aviation is our largest non-agricultural export industry, but we are losing our technological advantage to countries that have prioritized sustainable aviation technologies. Because our airports and aircraft use outdated technology, they disproportionately pollute the often-disadvantaged communities adjacent to them, causing health externalities while providing few benefits and job opportunities to local residents. Fixing this public health problem should start with the immediate phaseout of leaded aviation fuel, which is the largest source of lead emissions in the U.S. This should also be coupled with incentivizing advancements in sustainable aviation technology. The phaseout and innovation incentivization can be accomplished through regulatory agency mandates, new fees collected from combustion aircraft users, reprioritization of existing recurring federal funds for aviation, and allocation of additional funding—such as from the proposed national infrastructure plan—towards sustainable solutions. The focus of this funding should be comprehensive electrification of the entire aviation ecosystem, including airports, ground vehicles, support equipment, and aircraft. Electrification will remove the lead concern while also reducing other pollution and creating jobs. Funding for pollution mitigation and green job creation should be directed toward disadvantaged communities located near airports and U.S.-based small businesses developing green aviation technologies. These actions must be taken immediately, lest our public health continue to suffer, and lest we jeopardize the future of the U.S. aviation industry.

Challenge and Opportunity

Small aircraft are the largest source of environmental lead pollution in the US. Blood lead levels are significantly elevated for children living within 0.6 mi (1,000m) of airports where leaded aviation fuel (avgas) is used. An estimated 16 million Americans are at risk of elevated blood lead levels because they live near a regional airport, where the majority of flight operations are undertaken by small piston engine aircraft burning leaded fuel. Lead is a neurotoxin for which there is no safe level of exposure, as determined by both the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). However, the EPA has continued to permit over 2 grams of lead content per gallon of aviation gasoline, which is aerosolized into extremely dangerous microscopic particulate matter (PM) when burned in an aircraft piston engine. When inhaled, small PM is capable of directly entering the bloodstream. This lead exposure is especially dangerous for fetal development and for cognitive development in children. The science behind these effects is very well established because of decades of research into the effects of leaded automotive gasoline; this resulted in a complete ban of leaded gasoline in 1996, although aviation successfully lobbied for a special temporary exemption.

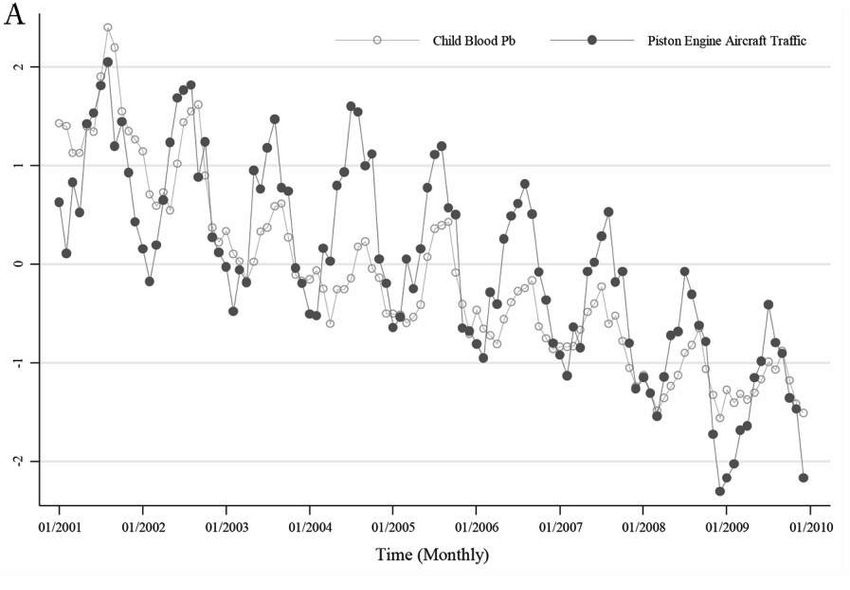

Monthly average child blood lead levels vs. sum of piston engine aircraft takeoffs and landings over time. This data was collected from over 1 million children living within 6.2 miles of 27 airports in Michigan with piston aircraft traffic. It is clear that blood lead levels rise and fall in concert with piston aircraft traffic.

Although most attention has been focused on about 30 large hub airports in the U.S., lead pollution occurs primarily at smaller regional airports due to their reliance on piston-engine aircraft. There are over 10,000 airstrips and over 5,000 public airports in the U.S., or a public airport within a 16-minute drive of the average American. The nearly 200,000 leaded-fuelburning aircraft operating from these airports are incapable of readily switching to unleaded fuel due to their outdated engine technology and the lack of availability of unleaded gasoline at most airports.

This is a map of regional airports where leaded avgas and other polluting fossil fuels are used. There are over 5,000 public airports in the US — or one within a 16-minute drive of the average American.

For both economic and technical reasons, a widespread, drop-in replacement for leaded aviation gasoline (avgas) has failed to emerge, despite the fact that leaded fuel was fully eliminated on our roads decades ago. Because of limited unleaded fuel supply, reduced power output, safety concerns, and pilot retraining needs, even engines theoretically capable of switching to unleaded fuel continue to use leaded fuel almost exclusively. However, simply switching to planes that use diesel or jet fuel is not the answer. Unlike cars, aircraft have no emissions control systems, and there is no existing way to install such systems. As a result, even aircraft that do not burn leaded fuel emit very high levels of PM and other forms of pollution detrimental to human health. For example, LAX alone produces nearly as much particulate pollution as all LA-area freeways combined, and LAX is just one of 39 airports in the local air district. It is critical to American public health that any policies to phase out leaded avgas concurrently foster adoption of reduced-emission and reduced-fuel-burn technologies (such as electric propulsion), rather than encourage switching to fuel-hungry and high-pollution unleaded gasoline engines, diesel engines, turboprops, and jet engines.

This is also critical to American economic health: European and Asian companies are beating the U.S. at developing efficient unleaded-fuel engines and electric propulsion technology, winning market share in regions traditionally dominated by US-built light aircraft (e.g. where leaded fuel is unavailable or expensive). We need to invest in sustainable propulsion systems to maintain U.S. competitiveness, and lack of supportive policy action has hampered technological advancement.

Zero funding, for example, has been allocated in the proposed American Jobs Plan to deal with dangerous aerosolized lead pollution from aviation, even though the plan dedicates $45B toward replacing lead pipes. Combating aviation pollution, however, offers a significant opportunity to pursue electrification, with a wide variety of shovel-ready airport project locations. The U.S. workforce can electrify airport infrastructure, ground vehicles, and aircraft domestically using existing and proposed federal funding as well as revenue from fees targeted at polluting aircraft. Shared charging infrastructure should be a special priority. Installing basic charging infrastructure at every one of the 5,000 public airports in the U.S. — focusing first on the 500 most heavily-used airports located closest to populated areas and in disadvantaged communities — is a highly achievable near-term goal at moderate expense. For instance, installing a 30-60 kW DC fast charger, which could charge small electric planes or ground vehicles, at the 500 highestpriority airports would cost less than $25M and could be completed in 2-3 years with sufficient federal backing.

Transitioning to biofuels or other so-called “sustainable” fuels can play a role, but should not be considered a substitute for fuel use reduction via electrification because their emissions can still be harmful. Both the biofuel supply chain and burning of biofuels, for example, emit a wide range of pollutants. Even green hydrogen, currently a tiny fraction of the world’s mostly fossil-fuel derived hydrogen supply, would still lead to emissions of water vapor. Water vapor is a powerful greenhouse gas when emitted at high altitude, and in some proposed implementations (such as direct hydrogen turbine combustion) hydrogen aircraft could also lead to significant high altitude nitrogen oxide pollution.

Electrification also offers an opportunity to better integrate airports into both urban and rural transit networks, provide clean energy and charging services to local communities (e.g., charging buses overnight), and improve resilience to power outages by offering grid storage. Electrification infrastructure at airports could include, for example, solar panels and grid storage doubling as power backup systems at airports. This would serve not just airport power needs but also those of surrounding communities, especially in remote areas prone to outages. This power system resilience is especially critical in disaster situations, where airports often serve as hubs for emergency responders.

In the near term, electrifying aviation entails plugging planes into gate power instead of burning fuel, using electric power to taxi to the runway, and operating electric tugs and ground equipment. Electrifying aviation also means investing in R&D, scaleup, and adoption of electric trainer aircraft, hybrid electric short-range cargo and passenger planes, and eventually longerrange commercial planes. As batteries and electronics improve, larger and larger planes will become more and more electric over time. To facilitate these technological advances in electric aviation and maximize public benefit, federal funding should focus on promoting adoption of electrification on routes not currently serviced or readily serviceable by rail or other alternative rapid, sustainable forms of transportation.

Plan of Action

Infrastructure Funding

Reprioritize existing funding sources, such as the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Voluntary Airport Low Emissions Program (VALE) program, to focus on sustainable infrastructure such as solar, storage, and chargers at both public airports and military airports. Supplement this funding by dedicating at least $10B of the proposed $25B of airport funding in the American Jobs Plan, or $20B of the proposed $56B Republican counter-offer, towards electrification across airports of all sizes. Initially prioritize:

- The 500 most heavily-used airports located closest to populated areas and in disadvantaged communities,

- Regional airports that have far fewer logistical barriers to infrastructure projects than congested hubs, and

- Airports supporting routes not currently serviced or readily serviceable by rail.

R&D Funding

Reprioritize existing federal research funding toward technologies aimed at reducing fuel burned by aircraft, such as significantly expanding current hybrid and electric aviation initiatives at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Department of Defense (DOD), Department of Transportation (DOT), and Department of Energy (DOE).1 Additional funding paid for by fees on polluting aircraft should be added to these existing pools of research dollars (see “Plan of Action” items 4-6). To remain competitive with accelerating civil and defense aviation technology development overseas, the government should direct a minimum of $2B in annual federal funding to electric aviation R&D. Funding should prioritize the development of US-designed and manufactured electric and hybrid electric aircraft technologies, including both retrofit and new-build planes, ground equipment, and ground vehicles. At least 50% of funds should be dedicated to small businesses.

The U.S. is currently the world leader in small aircraft production, but we are falling far behind Europe and Asia on electrifying fixed wing aircraft, funding development of new efficiency technologies, and implementing relevant policies. U.S. companies have instead focused primarily on low-capacity “flying cars” for carrying high-net-worth individuals short distances over traffic. The lack of funding and policy support for practical, high-impact innovation poses a significant threat to future U.S. competitiveness and jobs, especially in the export market.

Regulations

The EPA should issue its final endangerment finding banning leaded fuels, and the Biden-Harris Administration should issue an executive order instructing the EPA and FAA to work together to eliminate lead pollution. This includes immediately implementing a 10-year phaseout mandate for the sale of leaded fuel, with use of leaded fuel banned after 2030 except for a limited number of historic aircraft. This phaseout timeline should be extended to 2040 in Alaska, due to the disproportionate impact on the greater than 80% of Alaskan communities reliant on small planes for year-round access. During the Obama Administration, an attempt was made to phase out leaded avgas, but it stalled largely because of the perceived impact on mobility in Alaska. It is critical to ensure that a phaseout plan recognizes Alaska’s needs and funds sustainable solutions suitable for an arctic operating environment.

It is not enough to simply ban lead, because this may incentivize switching to other highly polluting technologies like dirty unleaded gasoline engines, diesel engines, and far less fuelefficient turboprop or jet engines. Thus, it is critical that a leaded fuel ban be accompanied by the immediate implementation of a fuel efficiency mandate for aircraft that are based in or that regularly fly to the U.S. Inspired by the federal automotive Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) Standards program, this efficiency mandate should utilize multiple aircraft size categories with targets based on maximum takeoff weight (e.g., <1,000 lb, 1,000-5,000 lb, 5,000- 19,000 lb, 19,000-75,000 lb, 75,000-250,000 lb, and 250,000 lb+ categories). Efficiency targets should take into consideration typical missions and technical difficulty in reducing fuel burn for various types of aircraft. For instance, <19,000 lb aircraft are readily able to use hybrid electric propulsion — and, in some cases, pure electric propulsion — with existing technology and regulations. The largest aircraft flying long distance routes, on the other hand, will initially need to focus on smaller steps such as more efficient flight patterns, plugging into gate power/HVAC, electric taxi (either onboard or via tug), etc. until future technologies are developed; therefore, larger aircraft should have less aggressive targets (similar to less aggressive CAFE standards for larger vehicles). Technologies piloted in smaller electric aircraft will eventually make their way to larger aircraft, initially as high-power subsystems. Thus, these technologies are key early targets for federal funding and mandates. The overall “CAFE” goal should be a 25% reduction in overall U.S. aviation fossil fuel burned per passenger by 2030, and a 50% reduction by 2040.

Taxes

The following programs offer pathways for making electrification programs financially sustainable beyond the initial infusions of funding for infrastructure transformation and R&D.

Immediately implement a national $10 per flight hour use tax on all aircraft with 19 passenger seats or below. This should include an additional $2 per flight hour tax on leaded fuel burning aircraft and on any other aircraft burning more than 4 gallons of fuel per seat per flight hour. It is essential to avoid solely targeting leaded fuel piston aircraft, which would incentivize a switch to less fuel-efficient turboprop aircraft and business jets. 100% of tax revenues should be dedicated to the aviation industry and airports, and at least 50% of funds should go to small businesses. Tax revenues should be allocated toward:

- The electrification of airports

- A “cash for clunkers” program to retire or retrofit polluting aircraft, with commercial and government operators receiving priority for funding. This funding should only be provided for US-manufactured or US-retrofit electrified aircraft.

- Jobs training and career development for airport-adjacent communities.

This would not be an undue burden on air travelers, because the owners and users of small aircraft are generally affluent. The Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association reports that the net worth of its average member is over $1.6 million. Aircraft operating in Alaska should be exempt from this tax until 2030. Revenue should exceed $260M/year based only on the base $10 fee, assuming pre-pandemic flight hour totals.

Immediately implement a $10 “Clean Skies Fee” per passenger for all international flights on planes with more than 19 passenger seats, excluding flights within North America, to be collected by air carriers from passengers at the time air transportation is purchased. The September 11 Security Fee offers a precedent for this type of fee.

An optional “Clean Skies Fund” contribution with suggested donations of $5, $10, $25, and $50 should also be offered at time of purchase for all flights on planes with more than 19 passenger seats—both domestic and international—to allow passengers an opportunity to further fund pollution-reducing technologies across the aviation ecosystem and to offset their personal environmental impact from flying. This fund is modeled after optional federal contributions such as the Presidential Election Campaign Fund.

A portion of collected funds should be provided to airlines and travel booking services in order to implement and maintain this contribution mechanism, which must be prominently featured in the booking process. Carriers will remit the fees to federal programs promoting reduction in fuel use, airport electrification, and jobs training. At least 50% of funds should go to small businesses. Revenue should exceed $2.34B/year assuming pre-pandemic international flight passenger demand.

For planes with more than 19 passenger seats, implement a similar $0.25/mile per passenger fee on all domestic and North America region flights effective in 2030 to fund fuel burn reduction and airport electrification. At least 50% of funds should go to small businesses, and all funds should be dedicated to projects that directly benefit airports and aviation, as well as increasing accessibility to all Americans.

Jobs

The actions above should be immediately implemented in order to preserve the millions of U.S. jobs in the aerospace industry. Aircraft are the largest non-agricultural U.S. export product and one of the largest domestic manufacturing industries. As of 2018, the aerospace industry was directly responsible for over 2.4 million primarily high-paying U.S. jobs, many of which are union jobs or in STEM fields. Airlines directly employ nearly 500,000 Americans, and a wide variety of indirect jobs in travel agencies, airports, construction, and related industries are reliant on aviation. Although we support expanded low-emissions rail transportation, continued modal shift away from aviation towards automobiles would be devastating to the airline industry and increase overall emissions.

The U.S. currently leads the world in aviation manufacturing, but we are falling behind in electric aviation technology, including both airport-based ground vehicles and aircraft. We are headed towards an inflection point that will determine the future of the U.S. aviation industry. Either U.S. policy will promote adoption of more efficient technologies for aircraft as well as airport vehicles and equipment, thereby maintaining U.S. world leadership in aviation, or the U.S. will lose this market to other nations in Asia and Europe. The only way to preserve aviation jobs is by investing in efficiency and by enacting smart policies that promote private investment in and adoption of cleaner technologies.

Not only can aviation jobs be preserved, but electrification of the aviation ecosystem will serve to create new green jobs related to air travel. This will include jobs in charging infrastructure installation, solar and storage construction, as well as related industries, which must be based locally and use U.S. labor. Further, if the U.S. leads in developing aviation electrification, there will be substantial export opportunities as other nations look to reduce aviation emissions and improve mobility. Potential clean aviation technology markets include countries such as Norway, which has committed to an electrified aircraft fleet by 2040 for all flights under 90 minutes duration, and Scotland, which has committed to a zero emissions airspace. Numerous other countries are actively considering similar policies, creating a significant opportunity for U.S. products.

Conclusion

Aviation emissions, especially lead, are a clear and present danger to the health of Americans and the global climate. Failing to develop and deploy more efficient technology represents an equal danger to U.S. jobs and competitiveness. Thankfully, practical solutions exist today and even more are being developed to mitigate these dangers. To advance this mitigation, the Biden-Harris Administration and legislators should ensure that existing and new federal funding prioritizes holistic electrification of the aviation ecosystem, in addition to enacting legislation and regulations that ensure the success of this transition.

Federally-supported initiatives aim to reduce maternal mortality and shed light on the effects of therapeutics on pregnant and lactating women

Each year about 700 women die from pregnancy or birth complications in the U.S., the worst maternal mortality rate out of all industrialized countries. The need to improve U.S. rates of maternal mortality, as well as bolster research on the safety of prescription drugs for the health of pregnant and lactating women, were both raised during last week’s House Appropriations Committee hearing about the National Institutes of Health (NIH) future research and funding priorities.

The maternal mortality crisis

The rate of maternal deaths has been rising in the U.S. since 2000, taking a serious toll on families from all different backgrounds. Maternal mortality is defined as any deaths during a pregnancy or within 42 days of the end of the pregnancy from “any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management.” More than half of maternal deaths occur after the day of birth, and one third occur during the pregnancy. The most common causes of death are cardiomyopathy (weakened heart muscles), blood clots, hypertension (high blood pressure), stroke, infection, and hemorrhage (heavy bleeding). This crisis is also exacerbated by disparities experienced by people of color: Black women are 2.5 times more likely to die than White women and three times more likely to die than Hispanic women.

Reducing maternal deaths, particularly among communities of color, is a top priority for Diana Bianchi, the director of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Just last year, the NIH established the Implementing a Maternal health and PRegnancy Outcomes Vision for Everyone (IMPROVE) Initiative. It aims to “mitigate preventable maternal mortality… and promote health equity” by using “an integrated approach to understand biological, behavioral, sociocultural, and structural factors.” The IMPROVE initiative has already awarded over $7 million in grants to address disparities in maternal mortality.

The lack of knowledge about safe drugs for pregnant and lactating women

While there are several active efforts to address maternal mortality, one aspect of women’s health that has not received as much attention: there is a significant lack of knowledge as to which drugs are safe for pregnant and lactating women to use. While this problem has existed for a long time, it is brought into clear focus when examining the recent clinical trials for COVID-19 treatments. Out of 927 clinical trials worldwide, only 16, less than 2%, evaluated the effectiveness of a treatment on pregnant women and their fetuses. More than half of the clinical trials excluded pregnant women specifically. Both Representatives John Moolenaar (R-MI) and Lois Frankel (D-FL) raised the knowledge gap in safe treatments for pregnant and lactating women during the hearing.

The exclusion of pregnant women from clinical trials largely stems from the thalidomide and diethylstilbestrol (DES) tragedies in the mid-1900s. DES entered the market in 1938 and was promoted as a way to prevent miscarriages and premature births, but almost 40 years later, researchers found the drug actually caused rare cancers in the daughters born to mothers who took it, as well as structural changes to the reproductive tract, and infertility. It also elevated risks of breast cancer in the mothers. Thalidomide was used during the late 1950s and early 1960s to treat morning sickness. Researchers found, however, that the drug caused devastating birth defects in babies. After these tragedies, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published guidelines in 1977 that prevented pregnant women from participating in phase I and phase II clinical trials.

Though it is now possible for pregnant women to enroll in clinical trials due to the passage of the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993, the researchers may only recruit them if the clinical trials adhere to strict regulations. Current regulations require conducting preclinical studies with pregnant animals and clinical studies with nonpregnant women prior to enrolling pregnant women. The clinical trials must also ensure the “least possible” risk to achieve objectives of the research, among other obligations. Because these requirements add time and cost to clinical trials, as well as necessitate the recruitment of sufficient numbers of pregnant women, many researchers opt not to include them. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that 70% of pregnant women take at least one prescription drug. Nevertheless, the fact that researchers rarely include pregnant women in clinical trials results in these women not having clear information about what drugs are safe for them and their babies. One study found that 90% of drugs approved by the FDA between 1980 and 2000 had no data about the drugs’ potential effects on pregnant women and their fetuses. Drug manufacturers now choose to track possible side effects after a drug’s release via self-reported registries. However, the requirement for pregnant women to report their own symptoms can skew the data toward only severe reactions, and omit any milder, but still clinically important, symptoms.

As part of the 21st Century Cures Act, NIH established the Task Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women (PRGLAC) to provide recommendations and an implementation plan on how to integrate pregnant and lactating women into drug safety research. The task force has already had a positive effect on the work at NIH, and helped launch the Maternal and Pediatric Precision in Therapeutics (MPRINT) Hub. The goal of the hub is to establish a center of knowledge that explains what drugs pregnant and lactating women can take safely, and the effects of medicines on babies.

More to be done

The initiatives NIH has launched so far are vital to reduce maternal mortality and support the health of pregnant and lactating women. These topics will likely continue to be priorities of the Biden Administration and Congress. If you have ideas on how the federal government can support further research in maternal health, we encourage you to serve as a resource for Members of Congress and their staff.

A health-oriented ARPA could help the U.S. address challenges like antimicrobial resistance

To help catalyze innovation in the health and biomedical sciences, research and development (R&D) paradigms with a track record of producing ‘moonshot’-scale breakthroughs – such as the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) model – stand at the ready. The Biden Administration has recognized this, proposing the establishment of an ARPA for health (ARPA-H) as part of its fiscal year 2022 budget request. Done right, ARPA-H would be created in the image of existing ARPAs – DARPA (defense), ARPA-E (energy), and IARPA (intelligence) – and be capable of mobilizing federal, state, local, private sector, academic, and nonprofit resources to directly address the country’s most urgent health challenges, such as the high cost of therapies for diseases like cancer, or antimicrobial resistance. During a recent House Energy and Commerce Committee hearing, Chairwoman Anna Eshoo (D-CA) raised the Administration’s proposal for ARPA-H with Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Xavier Becerra, expressing her interest in exploring how to best position a potential ARPA-H for success.

Keys to the ARPA model

The success of the ARPA model is attributed in part to the high level of autonomy with which its program leaders select R&D projects (compared to those at traditional federal research agencies), a strong sense of agency mission, and a culture of risk-taking with a tolerance for failure, resulting in a great degree of flexibility to pursue bold agendas and adapt to urgent needs. Policymakers have debated situating a potential ARPA-H within the National Institutes of Health (NIH), or outside of NIH, elsewhere under the umbrella of HHS. Regardless, it is essential that ARPA-H retain an independent and innovative culture.

The first ARPA – DARPA – was established in 1958, the year after Sputnik was launched, and is credited with developing GPS, the stealth fighter, and computer networking. DARPA continues to serve its customer – the Department of Defense – by developing groundbreaking defense technologies and data analysis techniques. Nevertheless, DARPA operates separately from its parent organization. This is also true of ARPA-E, which was launched in 2007 based on a recommendation from a National Academies consensus study report which called for implementing the DARPA model to drive “transformational research that could lead to new ways of fueling the nation and its economy,” and IARPA, created in 2006, to foster advances in intelligence collection, research, and analysis.

If ARPA-H is organized within NIH, it is essential that it maintain the innovative spirit and independence characteristic of established ARPAs. NIH already has some experience overseeing a partially independent entity: the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Compared to other NIH institutes, NCI’s unique authorities include:

- Direct access to the president;

- A requirement to submit a completely separate budget proposal to the president each year without getting approval from NIH or HHS; and

- The ability of the NCI director to form new cancer centers and training programs, establish advisory committees, and independently collaborate with other federal, state, and local entities.

This level of independence has contributed to NCI achieving a number of significant milestones in cancer treatment, including developing a chemotherapy treatment to cure choriocarcinoma (a rare type of cancer that starts in the womb), publishing the now-widely-used Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Model, and creating an anticancer drug for ovarian cancer that was unresponsive to other treatments.

If the NCI model were to be used as the foundation for the launch of ARPA-H, insulation from political considerations, whether those of Congress or the Executive Branch, would be critical. With DARPA-like autonomy, a potential ARPA-H could help push the boundaries of enrichments to human health.

Antimicrobial resistance as a case study for an ARPA-H

An example of a grand challenge that an ARPA-H could take on is addressing antimicrobial resistance, a worsening situation that, without intervention, will lead to a significant public health crisis. Antimicrobial resistance occurs when “bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites change over time and no longer respond to medicines, making infections harder to treat and increasing the risk of disease spread, severe illness, and death.” Microbes have the potential to gain resistance to drugs when not all of the pathogens or parasites are killed by a treatment, either because the treatment was the not correct option for the illness (like using antibiotics for viruses), or refraining from completing a prescribed course of an antimicrobial drug. The organisms that are not killed, presumably because they harbor genetic factors that confer resistance, then reproduce and pass along those genes, which make it harder for the treatments to kill them.

The most immediate concerns regarding antimicrobial resistance come from bacteria and fungi. The CDC considers some of the biggest threats to be Acinetobacter, Candida auris, and C. difficile, which are often present in healthcare and hospital settings and mainly threaten the lives of those with already weakened immune systems. Every year in the U.S., almost 3 million people are infected with antimicrobial-resistant bacteria or fungi, and as a result, more than 35,000 people die. While the toll of antibiotic resistance in the U.S. is devastating, the global outlook is perhaps even more concerning: in 2019, the United Nations warned that if no action is taken, antimicrobial resistance could cause 10 million deaths per year worldwide by 2050.

Developing new and effective antibiotics can help counter antimicrobial resistance; however, progress has been extremely slow. The last completely new class of antibiotics was discovered in the late 1980s, and developing new antibiotics is often not profitable for pharmaceutical companies. It is estimated that it takes $1.5 billion to create a new antibiotic, while the average revenue is about $46 million per year. In addition, while pharmaceutical companies receive an exclusivity period during which competitors cannot manufacture a generic version of their drug, the period is only five to ten years, which is too short to recoup the cost of research and development. Furthermore, doctors are often hesitant to prescribe new antibiotics in hopes of delaying the development of newly drug-resistant microbes, which also contributes to driving down the amount pharmaceutical companies earn for antibiotics.

Early last year, the World Health Organization reported that out of 60 antibiotics in development, there would be very little additional benefit over existing treatments, and few targeted the most resistant bacteria. Moreover, the ones that appeared promising will take years to get to the market. This year, Pew Research conducted a study on the current antibiotic development landscape and found that out of 43 antibiotics under development, at least 19 have the potential to treat the most resistant bacteria. However, the likelihood of all, or even some of these products making it to patients is low: over 95 percent of the products in development are being studied by small companies, and more than 70 percent of these companies do not have any other products on the market.

There is both a dire need for new innovations in the space, such as using cocktails of different viruses that attack bacteria to treat infections, and a gap between the research into and commercialization of new antibiotics – a perfect opportunity for a potential ARPA-H to make an impact. With this new agency, experimental treatments could be supported through the technology transfer process and matured to the point that the private sector is able to take the baton and move a new antimicrobial to market. This would be revolutionary for public health, and, combined with improved messaging around best practices for the use of antibiotics, save many lives.

Moving forward

The need for, structure, and possible priorities of a potential ARPA-H will continue to be discussed over the course of the congressional appropriations process, with consultation between the Legislative and Executive Branches. We encourage the CSPI community to serve as a resource for Members of Congress and their staffs to ensure that the new agency will be properly positioned to contribute to significant advances in human health and biomedical technologies.

FAS Announces Organ Procurement Organization Innovation Cohort

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Today, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), with financial support from Schmidt Futures, announced that six organ procurement organizations (OPOs) have joined the FAS Organ Procurement Organization Innovation Cohort, committing to use data science and transparency to accelerate improved patient outcomes and to inform ongoing, data-driven policy development.

This follows the finalization of the bipartisan, scientifically-informed OPO rule that can save more than 7,000 lives each year, and which has been highlighted by both Senate and House leaders as an urgent equity issue. Given COVID-19’s potential to affect and attack organs, coupled with its disproportionate impact on communities of color, the need for reform is only intensifying.

Through the Federation of American Scientists, the OPO Innovation Cohort will share data to establish open and transparent lines of communication between OPOs as nonprofit government contractors and the public they serve, including branches of the federal government, in an effort to build trust and support further reforms that will save patient lives. (See data visualization from the OPO final rule here.)

Working with alumni from the United States Digital Service, over the next 12 months the Innovation Cohort will leverage the most granular OPO data ever shared with external researchers to inform ongoing policy development at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and in Congress. During a transformative period in the organ procurement industry, the Innovation Cohort will help shape the future of organ recovery in America, improving OPO practice and informing OPO policy. Most importantly, the Innovation Cohort will help return OPOs to their core mission by singly focusing on striving toward new heights of operational excellence in order to increase organ transplants in an effort to best serve the public, organ donors, donor families and patients waiting for transplants.

In the coming months, the FAS OPO Innovation Cohort will share additional de-identified, retrospective data with the Federation of American Scientists to be published openly – including all referrals for donation made to the OPOs with every outcome documented, audits of hospital-level deaths, OPO financials (including organ acquisition charges), procurement and organ recovery data from organ recovery centers, and staffing models – and will work actively to source data science partners and researchers to mine these datasets for performance improvement insights.

“COVID-19’s ravaging effect on organs has further increased the urgency of accelerating accountability for the government’s contractors in organ donation. Transparency is a critical first step, and the Federation of American Scientists applauds today’s commitments from six OPO leaders to break from their peers and prioritize patients and the public interest.”

Federation of American Scientists Acting President Dan Correa

“So many of the problems and inefficiencies of the organ waiting list are solvable, but we need a new, data-driven approach. We look forward to seeing how the OPO Innovation Cohort, paired with interdisciplinary talent, can bring transformational change to a sector in dire need of it.”

Schmidt Futures Managing Director and Head of Partnerships Kumar Garg

The six OPO CEOs below have underscored their commitment to the following principles:

- Transparency: public sharing of data/analysis in order to set a standard to which all OPOs can be held;

- Accountability: support for the OPO final rule, and any efforts to move up implementation date so all parts of the country can be served by high-performing OPOs as soon as possible in 2024; and

- Equity: commitment to analyzing/publishing data to ensure all parts of community served.

Diane Brockmeier, Mid-America Transplant

Helen Irving, LiveOnNY

Ginny McBride, Our Legacy

Patti Niles, Southwest Transplant Alliance

Kelly Ranum, Louisiana Organ Procurement Agency

Matthew Wadsworth, LifeConnection of Ohio

Further, as the House Committee on Oversight and Reform is investigating “poor performance, waste, and mismanagement in organ transplant industry”, the OPOs in the FAS OPO Innovation Cohort offer themselves as a resource for Congressional staff, noting their commitment to transparency, accountability, and equity, setting a standard to which all OPOs should be held. The participating OPOs have informed AOPO that they are leaving AOPO, noting the Committee’s investigation into AOPO’s “lobbying against life-saving reforms.”

A full visualization of the final rule from Bloom can be viewed here.

Repurposing Generic Drugs to Combat Cancer

Summary

Cancer patients urgently need more effective treatments that are accessible to everyone. This year alone, an estimated 1.9 million people in the United States will receive new cancer diagnoses, and cancer will kill more than 600,000 Americans. Yet there are no targeted therapeutics for many cancers, and the treatments that do exist can be prohibitively scarce or expensive.

Repurposing existing drugs, especially off-patent generics, is the fastest way to develop new treatments. Hundreds of non-cancer generic drugs have already been tested by researchers and physicians in preclinical and clinical studies for cancer, some up to Phase II trials, and show intriguing promise. But due to a market failure, there is a lack of funding for clinical trials that evaluate generic drugs. This means that there isn’t conclusive evidence of the efficacy and safety of repurposed generics for treating cancer, and so cancer patients who desperately need more (and more affordable) treatment options are unable to realize the benefits that existing generics might offer.

To quickly and affordably improve the lives of cancer patients, the Biden-Harris Administration should create the Repurposing Generics Grant Program through the National Cancer Institute. This program would fund definitive clinical trials evaluating repurposed generic drugs for cancer. A key first step would be for President Biden to include this program in his FY2022 budget proposal. Congress could then authorize the program and related appropriations totaling $100 million over 5 years.

Strengthening the Economy, Health, & Climate Security through Resilient Agriculture and Food Systems

Introduction

For those who can afford to fill their fridge by clicking a button on their smartphone or walking around to the organic grocery around the corner, it is easy to forget how complex and fragile our food systems can be. However, for millions of Americans who suffer from poor health because of food insecurity, or farmers and ranchers whose yields are decreasing along with the nutrient density of their product, that fragility is felt every day. Sustainable food systems engender intricate connections and feedback loops among climate change, public health, food security, national security, and social equity. When one of these factors is overstressed, disaster can result.

COVID-19 has underscored the vulnerability of our food systems. The pandemic caused restaurants to close overnight, strained supply chains, and led to food rotting on land, in warehouses, and on shelves. Low-income and food-insecure families waited in lines that stretched for miles while producers and distributors struggled to figure out how to get supplies to those who needed them. Concurrently, generations of racial inequity and the coordinated disenfranchisement of Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) has crystalized as an issue that needs to be addressed at every level in our country, especially within our food and agricultural systems.

Addressing these issues—now and for the future—requires a coordinated response across sectors. Food security is deeply intertwined with public health and social equity. Un- and under- employment, the racial wealth gap, and increased financial hardships for certain communities result in increased malnutrition, obesity, metabolic diseases, and chronic illness, as well as particular susceptibility to severe impacts from COVID-19 infections during the present pandemic. The climate crisis compounds these issues. Farming practices that degrade soil health, reduce agriculture capacity, and compromise the well-being of small farms and rural communities prevent us as a nation from becoming healthier and more secure. As we look at opportunities to “build back better,” we must embrace paradigmatic shifts—fundamental restructuring of our systems that will support equitable and inclusive futures. Compounding crises require changes in not only what we do, but how we think about what we do.

A fundamental problem is that progress in modern agriculture has been implicitly defined as progress in agricultural technology (AgTech) and biotechnology. Little emphasis is placed on examining whole-systems dependencies and on how connections among soil health, gut bacteria, and antibiotic use in livestock impact human health, economic prosperity, and climate change. With such a narrow view of “innovation,” current practices will solve a handful of isolated problems but create many more.

Fortunately, alternatives are ripe for adoption. Regenerative farming, for instance, is a proven way to combat future warming while increasing the adaptive capacity of our lands, providing equitable access to food, and creating viable rural economies. Regenerative farming can also restore soil health, which in turn improves food quality while enhancing carbon sequestration and providing natural water treatment.

Transitioning away from dominant but harmful practices is not easy. The shift will require an inclusive innovation ecosystem, investors with long time horizons, new infrastructure, tailored education, economic incentives, and community safety nets. This document explores how the agricultural sector can support, and be supported by, policies that advance science, technology, and innovation while revitalizing living systems and equitable futures. We recognize that agricultural policy often overlooks interventions that are appropriately suited to advance these concepts with Black, Indigenous, people of color (BIPOC) communities and on tribal lands. To avoid this mistake, the concepts presented herein start from the ground up. We focus on the benefits of improving soil health and food security through regenerative agricultural activities, and provide examples of policies that could promote such activities in a variety of ways. Letting practice drive policy— instead of having policy dictate practice—will result in more sustainable, inclusive outcomes for all communities.

While agricultural policy can and should be shaped at the local, regional, state, and national level, this document places special emphasis on the role of the federal government. Building better food systems will require multiple government agencies, especially federal agencies, to collaboratively advance more equitable policies and practices. Most national agricultural programs are housed within the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). But the interconnectedness of how we produce food and fiber (and the ways in which those practices impact our environment and nourish people) demands priority investment not only from USDA, but also from the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Energy, the Department of the Interior, the Department of Defense, and the Department of Health and Human Services—to name just a few. This document—based on a review of existing policy recommendations and current practice, development and refinement of new ideas, and identification of underleveraged roles and programs within the government— suggests what such investments might look like in practice.

Improving genome sequencing infrastructure to detect coronavirus variants is a priority for CDC

As the U.S. continues to grapple with the pandemic, there are growing concerns about the risks posed by variants of SARS-CoV-2 – the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Recent data have shown that at least one SARS-CoV-2 variant is more transmissible than the original, and there are questions as to whether any variants could be more deadly. The main way to detect emerging variants is to perform widespread genome sequencing, but the sequencing infrastructure in the U.S. is struggling to keep up with demand. This issue was a major focus of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) briefing to the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies this week.

Origin of variants and their detection

Viruses replicate by taking advantage of a person’s own cells, and each replication introduces small changes into a virus’ genetic code. Usually, these mistakes either have no impact, or are harmful to the virus. Sometimes, though, these errors give the virus an advantage, like increased ability to infect other people. Besides increased transmissibility, it is possible that variants could also cause more severe disease, evade detection by diagnostic tests, reduce the effectiveness of treatments, escape infection-induced immunity, or render vaccines less effective.

These risks are why it is imperative that public health officials track the emergence of variants around the country, and around the globe. Variants are found by extracting genetic material from patient samples, using sequencing equipment to read the virus’ genetic code, and comparing it with other known samples. When increasing numbers of cases of disease are found to have been caused by a virus with a genetic signature that is only slightly different from that of the known samples, scientists can estimate that they may have found a new variant. For SARS-CoV-2 specifically, there are a few variants that appear to have an advantage and are able to spread much more easily than the original strain. These variants include the UK and South African strains. There are also some early data that a variant discovered in California is more contagious than the original.

Challenges for genome sequencing of viruses in the U.S.

Public health officials use genomic sequencing to monitor for a variety of viruses, but the increased demand during the COVID-19 pandemic has put the U.S.’ sequencing infrastructure under strain. Though the U.S. has over 28 million COVID-19 cases, or about one-fourth of the total number of cases in the world, only about 96,000 samples, or around 0.3 percent, have been sequenced. For U.S. labs, the sequencing process can be costly and time-consuming, taking 48 hours to readout a virus’ genome in the best case scenario, though typical turnaround times stretch up to seven days. The cost of just one virus genome sequence can be anywhere from $80 to $500.

The country’s current genomic sequencing infrastructure has not been prioritized as a public health need and, in the past, sequencing was typically performed only by research universities. In 2014, the CDC started funding public health labs to track foodborne illnesses with genomic sequencing. By 2017 every state had labs which could perform genome sequencing, but obtaining funding is still difficult.

Current efforts and the road ahead

The CDC has been working to form various partnerships to boost the U.S.’ capacity for virus genome sequencing. According to its website, CDC has focused on several activities to increase genomic sequencing capacity, including:

- Leading the National SARS-CoV-2 Strain Surveillance (NS3) system;

- Partnering with commercial diagnostic laboratories;

- Collaborating with universities;

- Supporting state, territorial, local, and tribal health departments; and

- Leading the SARS-CoV-2 Sequencing for Public Health Emergency Response, Epidemiology, and Surveillance (SPHERES) consortium.

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky echoed this during Tuesday’s briefing and noted that under her leadership, the agency has scaled from 250 SARS-CoV-2 sequences per week to 14,000 per week. She hopes to scale up enough that the CDC can sequence 25,000 samples per week, which is close to about 5% of positive cases. To do this, the White House announced last week it would provide $200 million to support more genomic sequencing, and the U.S. Congress is considering adding almost $2 billion to that effort in the next economic relief package.

This funding is also intended to sustain the U.S.’ genomic sequencing infrastructure for the future. Senator Tammy Baldwin (D-WI), who introduced the legislation to support further sequencing, said the federal government should establish “the basis of a permanent infrastructure that would allow us not only to do surveillance for COVID-19, to be on the leading edge of discovering new variants, but also…have that capacity for other diseases.” During Tuesday’s briefing, Ranking Member Tom Cole (R-OK) affirmed this idea, saying that the House Appropriations Committee needs to think about establishing long-term funding streams to ensure that infrastructure developed during this crisis can last well in the future.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted gaps in U.S. infrastructure for the genomic sequencing of pathogens, and the importance of tracking virus variants for our public health. While the CDC works with its partners to rapidly scale up sequencing capacity, lawmakers need to consider how to sustain it for future outbreaks. As the Biden Administration and Congress consider scaling and sustainment, we encourage the CSPI community to serve as a resource to federal officials on this topic.

Advanced air filtration may help limit the spread of COVID-19 when combined with other protective measures

Given the pervasiveness of COVID-19 throughout the U.S., the risk of infection to transportation workers and passengers is significant. For instance, in a survey of over 600 bus and subway workers in New York City, almost one quarter reported contracting COVID-19, and 76 percent personally knew a coworker who had died from the disease. During last week’s hearing, the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee discussed best practices for protecting transportation workers and passengers from COVID-19, with a particular focus on preventing the spread of the coronavirus through the air.

Transmission of COVID-19 via aerosols

In early October 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated its guidance, confirming that COVID-19 can be transmitted via aerosols in addition to larger respiratory droplets. When an individual with COVID-19 coughs, speaks, or breathes, tiny coronavirus-carrying droplets can travel over distances longer than six feet and stay suspended in the air for up to several hours. For the coronavirus, most transmission via aerosols occurs in enclosed, poorly ventilated spaces, when a person is exposed to respiratory particles for an extended period of time. Mass transit vehicles can be one such pathway for infection since people from different households share the same spaces while either working or riding to their destinations.

Protecting people from COVID-19 involves implementing measures to keep virus particles from entering individuals’ noses and mouths. Scientists have found that wearing a face covering can limit the amount of droplets an individual releases, and thus also reduce the amount of virus particles in the air. Masks can also provide some degree of protection to the wearer by providing a barrier between coronavirus-carrying droplets and the person’s nose and mouth. The CDC also suggests that buildings and transportation systems examine the quality of their ventilation and filtration systems to reduce spread of COVID-19. Effective ventilation quickly dilutes the amount of virus particles in the air and allows clean air to quickly circulate in enclosed spaces. Advanced filtration systems can help catch and retain virus-carrying particles on tightly woven inserts, keeping them from reentering the space. While any one of these methods alone is not sufficient to protect people from the coronavirus, a layered approach that combines many safeguards can reduce the ability of respiratory diseases like COVID-19 to spread.

Using advanced filters to remove coronavirus-carrying particles from enclosed spaces

Several Members of the Committee noted the importance of developing and implementing advanced filtration technologies on transportation systems and in buildings. Scientists estimate that the coronavirus can spread even via airborne particles under 5 microns in diameter. (For comparison, a single raindrop is typically about 2,000 microns in diameter.) Most buildings have filters with a Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value (MERV) rating of between 7 and 8, which means they can filter up to 84.9 percent of particles between 3 and 10 microns in diameter. Subway cars also use these filters. The highest rated filters (MERV 16 to 20) can capture over 75 percent of particles that are between 0.3 and 1 micron in diameter, and high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, which are used on airplanes, can theoretically remove at least 99.97 percent of particles 0.3 microns in diameter and larger. To better protect workers and passengers, transportation systems like Washington, DC’s Metro and the Bay Area Transit system in San Francisco are already testing out more advanced filtration technologies through pilot programs funded by the Federal Transit Administration.

Benefits of advanced filters beyond reducing spread of COVID-19

Widespread adoption of advanced filtration technologies can be beneficial not only to reduce the amount of coronavirus-carrying particles in the air, but also to trap other harmful aerosols. During the hearing, Dr. David Michaels from George Washington University and Dr. William Bahnfleth from Penn State University both noted that investing in better filters now can also protect people from inhaling harmful particulate matter from other sources. For example, wildfires contribute about 30% of all fine particulate emissions in the U.S., with many of these being 2.5 microns or smaller. Inhaling these harmful particles can be associated with cardiovascular and respiratory issues, as well as premature mortality, particularly in vulnerable groups such as the elderly, children, and pregnant women.

Enhanced air filtration is a useful tool to help slow the spread of COVID-19, especially when used alongside other measures like wearing masks, improving ventilation, social distancing, and hand washing. As the new administration and Congress work toward ending the pandemic, practices such as the widespread adoption of more robust filters are likely to be examined in more detail. We encourage our community to get involved in the effort to counter COVID-19 by engaging in future congressional hearings through our Calls to Action.

Delivering Healthcare Services to the American Home

Summary

The coronavirus pandemic has forced a sudden acceleration of a prior trend toward the virtual provision of healthcare, also known as telemedicine. This acceleration was necessary in the short term so that provision of non-urgent health services could continue despite lockdowns and self- isolation. Federal and state policymakers have supported the shift toward telemedicine through temporary adjustments to health benefits, reimbursements, and licensure restrictions.

Yet if policymakers direct their attention too narrowly on expanding telemedicine they risk missing a larger—and as yet mostly unrealized—opportunity to improve healthcare in the United States: increasing the overall share of health services provided directly to the home. At-home healthcare includes not only telemedicine, but also medical house calls (home-based primary care) as well as models in which individuals within communities offer simple support services to one another (i.e., the “village” model of senior care, which could be extended to included peer- to-peer health service delivery). The advent of “exponential” technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and the Internet of Things (IoT) is unlocking new possibilities for at- home healthcare across each of these models.

The next administration should act to reduce four types of barriers currently preventing at-home healthcare from reaching its full potential:

- Labor-market barriers (e.g., unnecessarily restrictive scope-of-practice rules and requirements for licensing and certification)

- Technical barriers (e.g., excessively slow and burdensome processes for regulatory approval, weak or absent standards for interoperability)

- Financial/regulatory barriers (e.g., methodologies for determining eligibility for reimbursements that favor incumbents over innovators)