British Parliament Report Criticizes Government Refusal to Participate in Nuclear Deterrent Inquiry

Although the British government has promised a full and open public debate about the future of Britain’s nuclear deterrent, it has so far failed to explain what decisions need to be made, failed to provide a timetable for those decisions, and has refused to participate in a House of Commons Defence Committee inquiry on the future of Britain’s nuclear deterrent, according to a British parliamentary report. The report partially relies on research conducted by the FAS Nuclear Information Project for the SIPRI Yearbook.

Although the British government has promised a full and open public debate about the future of Britain’s nuclear deterrent, it has so far failed to explain what decisions need to be made, failed to provide a timetable for those decisions, and has refused to participate in a House of Commons Defence Committee inquiry on the future of Britain’s nuclear deterrent, according to a British parliamentary report. The report partially relies on research conducted by the FAS Nuclear Information Project for the SIPRI Yearbook.

Effort Underway in European Parliament Against US Nuclear Weapons in Europe

A Written Declaration presented in the European Parliament calls for the withdrawal of US nuclear weapons from Europe by the end of 2006. The Declaration has until December 10 to gather support from at least half of the Parliament’s 732 members to be adopted and formally submitted to the US government. The initiative comes as Russia refused last week to discuss tactical nuclear weapons with the United States. Most European want the US to withdraw its remaining nuclear weapons from Europe.

A Written Declaration presented in the European Parliament calls for the withdrawal of US nuclear weapons from Europe by the end of 2006. The Declaration has until December 10 to gather support from at least half of the Parliament’s 732 members to be adopted and formally submitted to the US government. The initiative comes as Russia refused last week to discuss tactical nuclear weapons with the United States. Most European want the US to withdraw its remaining nuclear weapons from Europe.

Background report: U.S. Nuclear Weapons In Europe

IAEA Secretary General elBaradei Supports Indian-US Nuclear Deal.

In an op-ed in last Wednesday’s Washington Post, IAEA Secretary General Mohammad elBaradei endorsed the US-India nuclear deal without reservation. The Secretary makes several good points but he fails to demonstrate his assertion that the deal will help reach his own objectives.

(more…)

37 Nobel Laureates Sign Letter Opposing the Indian-US Nuclear Deal

Thirty seven Nobel Laureates signed a letter opposing the administration’s proposed nuclear trade deal between India and the United States. The letter was released at a press briefing at the National Press Club yesterday.

The Federation of American Scientists was founded by scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project to develop the first atomic bombs. The founders of FAS understood that the technology that made nuclear power possible and the technology that made nuclear weapons possible were inextricably entangled. One of the founding issues of the Federation was, therefore, openness and international inspection, if not control, of all the world’s nuclear facilities. They recognized that this was the only hope of avoiding wide-spread proliferation of nuclear weapons.

Here we are sixty years later and faced with the same issue. The Federation strongly supports improved economic, cultural, trade, academic, and security relations with India. We would like to see Chinese, as well as US, Russian, indeed, everyone’s nuclear arsenals dramatically reduced and eventually eliminated. The Indian-US nuclear deal further undermines the already weakened non-proliferation regime and pushes the world in the wrong direction, toward greater legitimacy of nuclear weapons.

The Federation of American Scientists is proud that thirty seven Nobel Laureates on its Board of Sponsors agreed to endorse this letter to Congress.

US Air Force Publishes New Missile Threat Assessment

The Air Force has published a new report about the threat from ballistic and cruise missiles. The new report, Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat, presents the Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center’s (NASIC) assessment of current and emerging weapon systems deployed or under development by Russia, China, India, Pakistan, North Korea, Iran, Syria and others.

The Air Force has published a new report about the threat from ballistic and cruise missiles. The new report, Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat, presents the Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center’s (NASIC) assessment of current and emerging weapon systems deployed or under development by Russia, China, India, Pakistan, North Korea, Iran, Syria and others.

Among the news in the report is a different and higher estimate for China’s future nuclear arsenal than was presented in the previous NASIC report from 2003. Whereas the previous assessment stated that China in 15 years will have 75-100 warheads on ICBMs capable of reaching the United States, the 2006 report states that this number will be “well over 100” warheads. NASIC also believes that a new Chinese cruise missile under development will have nuclear capability.

Also new is that NASIC reports that the Indian Agni I ballistic missile has not yet been deployed despite claims by the Indian government that the weapon was “inducted” into the Indian Army in 2004. Contrary to claims made by some media and experts, the NASIC report states that the Indian Bramos cruise missile does not have a nuclear capability. The Babur cruise missile under development by Pakistan, however, is assessed to have a nuclear capability.

A copy of the report, which was published in March 2006 and recently obtained by the Federation of American Scientists, is available in full along with previous versions here.

Council on Foreign Relations Gets It Wrong on India

The Council on Foreign Relations just released a “Special Report,” U.S.-India Nuclear Cooperation by Michael Levi and Charles Ferguson. Mike and Charles are first rate thinkers but I disagree with almost every aspect of their report.

The report is seductively misleading because many of the recommendations make good sense given the presumptions and context of the report. But the presumptions and context are wrong. So first, we need to step back and examine the context. The authors state early on that “…the Bush administration has stirred deep passions and put Congress in the seemingly impossible bind of choosing between approving the deal and damaging nuclear nonproliferation, or rejecting the deal and thereby setting back an important strategic relationship.” [p. 3] This is true, but the problem is with the deal, not the implementation.

(more…)

NATO Nuclear Policy at Odds with Public Opinion

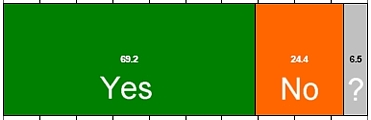

Almost 70 percent of people in European countries that currently store U.S. nuclear weapons want a Europe free of nuclear weapons, according to an opinion poll published by Greenpeace International. In contrast, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld suggested in an interview with Der Spiegel last November that the Europeans want to keep U.S. nuclear weapons.

Question: “Do You Want Europe to be Free of Nuclear Weapons or Not?”

Background: U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe

Turkish Parliament Debates US Nuclear Weapons At Incirlik Air Base

Deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Turkey was brought up in a debate in the Turkish Parliament today by Turkey’s former Ambassador to the United States, Sukru Elekdag. According to an article in the Turkish paper Hürriyet, Elekdag called attention to a report, US Nuclear Weapons In Europe, which asserts that the U.S. Air Force stores 90 nuclear bombs at the Incirlik Air Base in southern Turkey.

Deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Turkey was brought up in a debate in the Turkish Parliament today by Turkey’s former Ambassador to the United States, Sukru Elekdag. According to an article in the Turkish paper Hürriyet, Elekdag called attention to a report, US Nuclear Weapons In Europe, which asserts that the U.S. Air Force stores 90 nuclear bombs at the Incirlik Air Base in southern Turkey.

The report was published one year ago, but the initiative by Elekdag, who represents the Republican People’s Party (CHP), is the first time the findings have been brought before the Tuskish Parliament. The Tuskish debate follows calls last year in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands for a withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe, something NATO and the Pentagon have rejected. Elekdag pointed out that nuclear weapons were removed from Greece only a few years ago and that Turkey’s continued allowance of U.S. nuclear bombs at Incirlik is hard to explain to Muslim and Arab neighbors.

WMD Commission Seeks to Revive Disarmament

In a whopper 231-page report published today, the Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission presented 60 specific recommendations for how to move the nonproliferation and disarmament agenda forward.

In a whopper 231-page report published today, the Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission presented 60 specific recommendations for how to move the nonproliferation and disarmament agenda forward.

The recommendations are familiar to anyone involved in these matters over the past 50 years: reduce the danger of nuclear arsenals; prevent proliferation of weapons of mass destruction; outlaw weapons of mass destruction; etc.

The Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission (WMDC) was established in 2003 by the Swedish Government acting on a proposal by then United Nations Under-Secretary-General Jayantha Dhanapala to present realistic proposals aimed at the greatest possible reduction of the dangers of weapons of mass destruction. The Commission is chaired by Hans Blix, the former Executive Chairman of the UN Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC), and includes among others William J. Perry, former U.S. Secretary of Defense, Jayantha Dhanapala, the former UN Under-Secretary-General for Disarmament Affairs, and Alexei G. Arbatov of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

The Commission’s report uses the World Nuclear Forces overview co-produced by Federation of American Scientists for the SIPRI Yearbook to describe the status of existing nuclear arsenals, but the report does not dwell on past nuclear arms reductions which are often used by the nuclear weapon states to say they have done enough. Instead, the Commission calls for new and additional actions to curb existing weapons of mass destruction arsenals and prevent new ones from emerging. Commission chairman Hans Blix writes in the foreword that “the climate for agreements on arms control and disarmament has actually deteriorated” in recent years and “nuclear-weapon states no longer seem to take their commitment to nuclear disarmament seriously.”

That is certainly true. Nuclear disarmament has all but disappeared from the arms control agenda, and the nuclear weapons states instead use proliferation to justify their own nuclear weapons which they are busy modernizing and tailoring against the new enemies. Proliferators, in turn, use the offensive military postures of the nuclear weapon states as an excuse to develop their own nuclear weapons.

The Commission’s recommendations are a wide-ranging list of constraints that, if implemented, will constrain all actors, existing nuclear weapon states as well as proliferators. But from the outset, the report is strongly at odds with the policies of several of the major nuclear weapon states, particularly the United States. The Commission is unlikely to have many friends in the current White House, which will almost certainly reject its call for a revitalization of the “thirteen practical steps” to disarmament adopted at the 2000 nuclear nonproliferation treaty review conference, steps that have specifically been rejected by the Bush administration.

Other recommendations include a no-first-use policy for nuclear weapons, an idea the U.S. will almost certainly reject, as will many of the other nuclear powers. A no-first-use policy has been explicitly rejected by the United States and NATO, and Russia has abandoned its no-first-use policy. The report also calls for nuclear weapon states to abandon the practice of deploying nuclear forces in a triad of sea-, land- and air-based delivery platforms, something most of the nuclear powers insist is necessary. The Commission also wants nuclear weapon states to end deployment of nuclear weapons outside their own territories, an indirect call for a withdrawal of the remaining U.S. nuclear bombs from Europe.

With an eye to the new roles that existing nuclear weapon states are creating for their nuclear arsenals against proliferators of weapons of mass destruction, the Commission recommends that nuclear weapons states “refrain from developing nuclear weapons with new military capabilities or for new missions,” and they “must not adopt systems or doctrines that blur the distinction between nuclear and conventional weapons or lower the nuclear threshold.”

Some of the Commission’s recommendations extend to indirect measures, such as a freeze on ballistic missile defense systems, a key priority for the United States and increasingly also other countries. The Commission also wants assurances that Iran will not be attacked or forced to change government in the conflict over the country’s clandestine nuclear weapons program.

Surprisingly, the report does not recommend that India and Pakistan join the non-proliferation treaty, although their absence is said to hurt the regime. Instead, both countries are urged to join a number of other initiatives such as the Comprehensive test Ban Treaty.

The report’s greatest weakness may be that it doesn’t sufficiently incorporate “the other side” of the debate and therefore runs the risk of being seen as a manifesto of arms control proposals from the past that “preach to the choir” rather than presenting new ideas on how to move the agenda forward.

On the other hand, the fact that the Bush administration’s policies – and those of several other nuclear powers i.e. Russia – are so at odds with a revitalized disarmament and nonproliferation agenda suggests how necessary the Commission’s recommendations are. The United States has considerable leverage on these issues, the report acknowledges, but all countries – not only the proliferators – must accept constraints on their own operations if the disarmament and nonproliferation agenda is to move forward. The alternative is indefinite insecurity for all.

NNSA Walking a Fine Line on Divine Strake

Update (February 22, 2007): DTRA announces that Divine Strake has been canceled.

Update (February 22, 2007): DTRA announces that Divine Strake has been canceled.

In a surprising move, the National Nuclear Security Administration last week withdrew (!) its Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) for Divine Strake, a document issued in April that declared that a planned detonation of 700 tons of chemical explosives at the Nevada Test Site “would not result in the suspension or dispersion of radioactive materials or human exposure to radioactive materials.”

The question therefore is: Does this mean that Divine Strake could result in the suspension or dispersion of radioactive materials or human exposure to radioactive materials? And do other assurances about the test need to be reassessed?

The decision to withdraw the FONSI, NNSA says in a press release, which is not available on their web site, was made “to clarify and provide further information regarding background levels of radiation from global fallout in the vicinity of the Divine Strake Experiment.” That seems to be beaucratish for “sorry, we were wrong.”

The revised Environmental Assessment for Divine Strake, which has not been withdrawn but could potentially be revised, concluded earlier this month: “Results confirm there is no radiological contamination within the impact area of DIVINE STRAKE; therefore, no contamination could be resuspended into the environment.” The claim echoes the statement made last month by the Environmental Protection Specialist for Divine Strake, Linda Cohn: “There is literally no way this experiment can pick up radioactive contamination because it does not exist here.”

Yet since “here” is the Nevada Test Site, the home of well over 1,000 nuclear explosions in the past, many of which scattered radioactive nuclear fallout over adjacent states, many were surprised by NNSA’s radiation-does-not-exist-here-assurance. The FONSI withdrawal follows a lawsuit that claims the government failed to complete required environmental studies for Divine Strake. NNSA’s withdrawal of the FONSI acknowledges that atmospheric testing in the 1950s and 1960s “resulted in the dispersion of radioactive fallout throughout the northern hemisphere,” presumably also at the Nevada test Site. Time will tell whether NNSA ignored public health to get approval for Divine Strake.

Time will also test another of the government’s claims: That Divine Strake is not related to nuclear weapons missions at all. This claim is particularly problematic because the government in consecutive budget requests informed Congress that the experiment is intended to provide information that will permit warfighters to set the yield accurately when attacking underground facilities with nuclear weapons.

The Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA), NNSA’s contractor for Divine Strake, confirmed in writing to FAS on April 3, 2006, that “Yes, the event described [in the budget documents] is Divine Strake,” and even elaborated that “Better predictive tools will reduce the uncertainties involved with defeating very hard targets, and therefore reduce the need for higher yield weapons to overcome those uncertainties.”

When that confirmation became public, DTRA suddenly change its story, saying it had made a mistake and that Divine Strake was is not related to nuclear weapons missions at all. The nuclear reference “got left in” improperly, DTRA told Washington Post, and there is “no relationship between this test and any new nuclear weapons.” Moreover, DTRA later explained to me, even though the 700 tons of explosive exceeds [by far] the capability of any conventional weapon – but fits nicely with the low yield of the B61 nuclear bomb – the “explosive amount represents no specific weapon, nuclear or conventional. Warfighters can use the models for their planning. Their planning is for conventional, advance conventional and high energetics weapons.” But not for nuclear weapons?

Contrast that explanation with the statement made by DTRA’s director of the counter-WMD program, Douglas J. Bruder, on CNN in late April: “Particularly a charge of this size would be more related to a nuclear weapon.”

It is true that the Pentagon is developing non-nuclear weapons to destroy underground targets, but the claim about “no relationship” to nuclear weapons is suspect also because Los Alamos National Laboratory as recently as in 2004 conducted a high-speed computer simulation of a 10-kiloton nuclear earth-penetration weapon against the same tunnel that is used for Divine Strake. The 10 kiloton is considerably less than the 400-kiloton single-yield of the existing B61-11 earth-penetrating nuclear bomb currently in the stockpile, but it might be a yield that was envisioned for the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP).

Yet Congress has repeatedly rejected the Administration’s request to fund work on the RNEP, partially due to concern that more useable nuclear weapons with lower yields for these kinds of earth-penetrating missions will make nuclear weapons more acceptable to use.

“Officials who say they are using this Divine Strake test in planning for new nuclear weapons seem to be ignoring Congressional intent about no nuclear weapons,” Congressman Jim Matheson said after a tour at the test site and a DTRA briefing in late April.

The political explosiveness of Divine Strake far exceeds its military power and the government appears to be walking a fine line to avoid a clash with Congress – so fine that it can’t seem to get its story straight.

Make Trident Conventional

The week before last, Harold Brown and James Schlesinger argued in an op-ed in the Washington Post that the United States should arm some of the ballistic missiles on the Trident submarine with conventional warheads. Michael Gordon had a story in yesterday’s New York Times explaining that Rumsfeld fully supports the idea and hopes to get the system operational within two years. This is the implementation of the Global Strike plan that FAS’s Hans Kristensen has recently documented in detail.

The idea is that we might get some indication that something dire is about to happen but only have a moment to act because the vulnerability of the target will be fleeting, requiring that it be attacked within an hour. It is a challenge to try to think of any such situation. The Times article proffered a meeting of terrorists. Terrorists who we knew enough about to monitor their communications, but without knowing their locations (otherwise we could have attacked them earlier), terrorists who are going to get together for a meeting that will last an hour (if shorter, then even the Trident couldn’t get them), but no longer (because then cruise missiles have time to get to them). Readers should try their hand at thinking up other scenarios and ranking them for plausibility.

Our recent experience with intelligence should make us wary but intelligence that has to be digested in a half hour (the other half of the hour goes to the missile’s flight time) should be particularly suspect. One could even imagine the enemy spoofing the system, drawing a multi-million dollar missile onto an empty barn, or worse, the Chinese ambassador’s mistress’s apartment. Can we be confident, after half an hour’s research, that the target is not the Chinese ambassador’s mistress’s apartment?

Like many other proposals out of the Pentagon, this one is far too broad; it squanders resources on hypothetical threats because it fails to take into account the actual world we live in. We need this system because of some unnamed threat in some unnamed place. But where? North Korea? When are we likely to not have a military presence near North Korea that could launch air craft or cruise missiles? The same with Iran. If there were terrorists in Mongolia, this might make sense. So tell us that the system is for attacking targets in Mongolia. Then we can evaluate it honestly.

This proposal should (but probably won’t) raise some profound fundamental questions. The conventional warheads have to be mounted on Trident missiles because they are the only launch platform that is routinely forward deployed within the requisite half hour flight time. So the first question is: why? Why are Trident submarines—carrying missiles capable of flying thousands of miles in thirty minutes and armed with highly accurate nuclear warheads of hundred of kilotons yield—forward deployed at all times? If we ignore what the government says and just focus on the structure and deployment of our nuclear forces, their primary mission is clear: the US nuclear force is still deployed to execute a disarming nuclear first strike against Russia’s central nuclear forces. No other mission comes even remotely close to justifying the current force posture. This proposal would be a good thing if it resulted in a serious reevaluation of the role of the US nuclear forces and Trident in particular.

The implausibility of a target is really a minor problem; by itself that would mean this new system would be, at worst, simply a waste of money. A much graver concern is the dangers such a system might raise. If the Russians and the Chinese can detect Trident missiles launches (and both can to a limited degree), then, when the missile breaks the surface, how do these potential target nations know that the missile is a conventional missile headed toward North Korea and not a nuclear missile headed toward them? While thinking about this, consider that the Russians are not stupid, they can look at the US nuclear force posture and figure out what its primary mission is. Also, when considering nuclear weapons, a cautious worst-case analysis is called for. We should plan for a time when relations with China or Russia are strained. Does the “they’ll trust us” argument work the day after a US reconnaissance plane has been forced down? If the Chinese or Russians see a Trident launch, they will assume (a) that it is nuclear and (b) headed toward them until they get evidence that it is not.

Fortunately, I have the answer: de-nuclearize Trident. Don’t convert just one or two missiles per boat to conventional warheads but all of them. Follow the lead of the surface Navy and eliminate the nuclear/conventional ambiguity by removing all nuclear warheads from the Tridents and inviting in Russian and Chinese observers to confirm it. The Chinese do not have any intercontinental nuclear weapons on alert and if, as the US declares, we have no plans for a disarming first strike against Russia, there is absolutely no plausible justification for keeping Trident constantly forward deployed armed with nuclear warheads. A de-nuclearized Trident armed with conventional warheads would be a big improvement over what we have today.

Visting the Titan Missile Museum

On a recent trip to Tucson, Arizona I visited the Titan Missile Museum, something I recommend for all FAS blog readers who might be in the area. The tour was great. You get to visit the silo and the launch control area. They even have a decommissioned Titan missile in the silo. All very impressive.

I confess, I was a bit apprehensive about the lecture I was going to get as part of our orientation. I fully expected it to be a Cold War propaganda fest. But the comments were, in fact, quite good. There was one description of deterrence that I could have quibbled with a bit but overall I was pleased. Still, it is sometimes best to look to a child for clarity. One young visitor sent in a drawing that I think sums up the Titan missile perfectly, everything else is just details. I posted it here.