United States Removes Nuclear Weapons From German Base, Documents Indicate

|

|

The United States appears to have quietly removed nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base. Here a B61 nuclear bomb is loaded unto a C-17 cargo aircraft. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

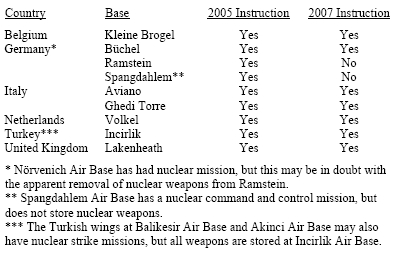

The U.S. Air Force has removed its main base at Ramstein in Germany from a list of installations that receive periodic nuclear weapons inspections, indicating that nuclear weapons previously stored at the base may have been removed and withdrawn to the United States.

If correct, the withdrawal reduces the number of U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe to an estimated 350 B61 bombs, or roughly equivalent to the size of the entire French nuclear weapons inventory.

New Nuclear Inspection List

The new nuclear inspection list is contained in the unclassified instruction Nuclear Surety Staff Assistance Visit (NSSAV) and Functional Expert Visit (FEV) Program Management published by the U.S. Air Forces in Europe (USAFE) on January 29, 2007. The instruction supersedes an earlier version from March 29, 2005, which did include Ramstein Air Base.

The NSSAV team includes 14-31 inspectors with expertise in the different areas of nuclear weapons mission management. The NSSAV normally takes place six months prior to the a Nuclear Surety Inspection (NSI), and the visit is intended to help prepare the unit for the much more rigid NSI, which units with nuclear weapons mission responsibilities must pass at least every 18 months to remain certified to handle and store nuclear weapons. During the visit, which normally lasts a week, the NSSAV team observes and evaluates how the unit conducts day-to-day operations and administers nuclear surety program management. A typical visit includes uploading and downloading of training nuclear weapons on strike aircraft.

|

|

|

|

Sources: U.S. Air Forces in Europe, Instruction 91-125, Nuclear Surety Staff Assistance Visits (NSSAV) and Functional Expert Visits (FEV) Program Management, January 29, 2007; U.S. Air Forces in Europe, Instruction 91-125, Nuclear Surety Staff Assistance Visits (NS SAV) and Functional Expert Visits |

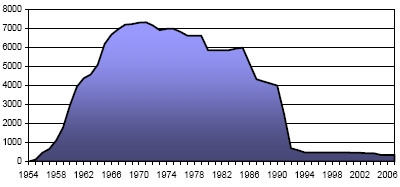

A Brief History of U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe

The current number of approximately 350 nuclear weapons is only a fraction of the force level the United States deployed in Europe during the Cold War. That level reached a peak of 7,300 weapons in 1971. The number dropped to 4,000 by the end of the Cold War in 1990, plunged to 700 in 1992, and leveled off at approximately 480 weapons (all bombs) in 1994. This ended the dramatic period of nuclear disarmament initiatives, which has since been replaced by a period of relative stability with slow and gradual reductions happening mainly due to base closures rather than arms control initiatives.

One of the last acts of the Clinton administration in late 2000 was to authorize deployment of 480 nuclear bombs at nine bases in seven European NATO countries. Twenty of the bombs were withdrawn in 2001 after Greece pulled out of the NATO nuclear strike mission, and another 20 were withdrawn in 2003 when Germany closed Memmingen Air Base.

The Bush administration updated the deployment authorization for Europe in May 2004 to reflect these changes, and it is possible that the authorization may have cleared the withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base. But as of late March 2005, Ramstein was still on the updated list of installations receiving nuclear surety staff assistance visits. The report U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe published by the Natural Resources Defense Council in February 2005 estimated 440-480 nuclear bombs deployed in Europe.

|

US Nuclear Weapons in Europe, 1954-2007 |

|

| The U.S. deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe peaked in 1971 at 7,300 weapons, was reduced significantly a decade and a half ago, but has remained comparatively stable since then. |

Then in May 2005, the German magazine Der Spiegel cited unnamed German defense officials saying that the U.S. had quietly removed nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base during major construction work at the base. The assumption was that the move was temporary, but the German officials hoped they would never return. Their wish seems to have come through with Ramstein’s removal from the updated Air Force instruction published in January 2007.

Both the U.S. government and NATO have always refused to disclose the number of weapons deployed in Europe but occasionally have provided the approximate range of the force level or the percentage of reduction since the Cold War. In an interview with Italian RAINEWS in April 2007, NATO Vice Secretary General Guy Roberts also refused to disclose the number weapons, but explained: “We do say that we’re down to a few hundred nuclear weapons.”

Seen in Cold War context, 350 bombs may not seem like a lot, but for the post-Cold War era it is a significant force. It is roughly equivalent is size to the entire French nuclear arsenal, larger than the Chinese nuclear arsenal, and it is larger that the nuclear arsenals of all the three non-NPT countries Israel, India and Pakistan combined.

Recent Reaffirmation of Nuclear Mission

Despite the apparent reduction, NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) as recently as June 15, 2007, reaffirmed the importance of deploying U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe. NPG stated that the purpose of the weapons is to “preserve peace and prevent coercion and any kind of war,” and that NATO places “great value” on the U.S. deployment in Europe. The NPG did not identify any particular enemy that the weapons are intended to protect against, but instead said they “provide an essential political and military link between the European and North American members of the Alliance.”

|

|

|

|

The only nuclear weapons storage site in Germany now appears to be Büchel Air Base, where theft – not enemy attack – is the main threat, as practiced by these security forces in February 2007. |

Germany’s Nuclear Decline

The apparent withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base also raises questions about the continued nuclear strike mission of the German Tornado squadron at Nörvenich Air Base. The base previously stored nuclear weapons, but they were moved to Ramstein in 1995 with the intent that they could quickly be returned to Nörvenich if necessary. A withdrawal from Ramstein would indicate that the 31st Wing at Nörvenich probably no longer has a nuclear strike mission, and that Germany’s contribution to NATO nuclear mission now is reduced to Büchel Air Base.

A reduction to a single German nuclear base with “only” 20 nuclear bombs is a dramatic change from the late-1980s, when more than 2,570 nuclear weapons were deployed at dozens of locations across the country. The latest withdrawal follows a political seachange in German voters’ views on nuclear weapons in the country. A poll published by Der Spiegel in 2005 revealed an overwhelming support across the political spectrum for a complete withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Germany.

The German government said in May 2005 that it would raise the issue of continued deployment within NATO, but officials later told Der Spiegel that the government had changed its mind. Yet the withdrawal from Ramstein indicates that the government has been more proactive than thought or that the Bush administration “got the message” and decided not to return the weapons. The withdrawal reduces Germany from the status of a major nuclear host nation to one on par with Belgium and the Netherlands, both of which also only have one nuclear base. The German government can now safely decide to follow Greece, which in 2001 unilaterally left NATO’s nuclear club. This in turn would open the possibility that Belgium (and likely also the Netherlands) will follow suit, essentially throwing NATO’s long-held principle of nuclear burdensharing into disarray.

A New Southern Focus

For now, the withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base shifts the geographic focus of NATO’s nuclear posture to the south. Before the withdrawal, a clear majority of NATO’s nuclear weapons were deployed in Northern and Central Europe. After the withdrawal, however, more than half (51%) of the weapons are deployed in Southern Europe along the Eastern parts of the Mediterranean Sea in Italy and Turkey.

The geographic shift has implications for international security issues that NATO countries are actively involved in, such as the attempts to create a Mediterranean Nuclear Weapons Free Zone, and the efforts to persuade countries like Iran not to develop nuclear weapons. The new southern focus of NATO’s nuclear posture will make it harder to persuade other countries in the region to show constraint.

Background: Satellite Images of U.S. Nuclear Weapon Bases Europe | U.S. Nuclear Weapons In Europe (report from 2005)

New Chinese Ballistic Missile Submarine Spotted

By Hans M. Kristensen

|

|

A new satellite image appears to have captured China’s new ballistic missile submarine. Coordinates: 38°49’4.40″N, 121°29’39.82″E. |

A commercial satellite image appears to have captured China’s new nuclear ballistic missile submarine. The new class, known as the Jin-class or Type 094, is expected to replace the unsuccessful Xia-class (Type 092) of a single boat built in the early 1980s.

The new submarine was photographed by the commercial Quickbird satellite in late 2006 and the image is freely available on the Google Earth web site.

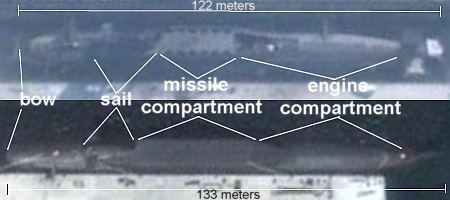

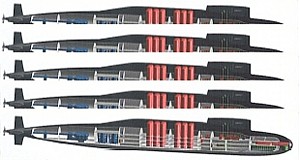

A Comparison of SSBN Dimensions

Two satellite images are now available (see figure below) that clearly show two missile submarines with different dimensions. One image from 2005 shows what is believed to be the Xia-class (Type 092) SSBN in drydock at the Jianggezhuang Submarine Base approximately 14 miles east of Qingdao. The submarine is approximately 390 feet (120 meters) long of which the missile compartment makes up roughly 80 feet (25 meters). Twelve missile launch tubes are clearly visible.

The second image from late 2006 shows what appears to be the new Jin-class (Type 094) SSBN moored at the Xiaopingdao Submarine Base south of Dalian, approximately 193 miles north of Qingdao. The Jin-class appears to be approximately 35 feet (10 meters) longer than the Xia-class SSBN, primarily due to an extended mid-section of approximately 115 feet (35 meters) that houses the missile launch tubes and part of the reactor compartment.

|

Xia- and Jin-Class SSBN Comparison |

|

|

These two commercial satellite images of the old Xia-class SSBN (top) and the new Jin-class SSBN show the different major compartments. The Jin-class appears to be approximately 35 feet (10 meters) longer with an extended missile compartment. Both images view the submarines from a “eye-altitude” of approximately 500 feet (152 meters). |

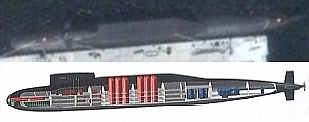

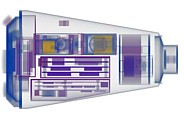

The extended missile compartment of the Jin-class seems seems intended to accommodate the Julang-2 sea-launched ballistic missile, which is larger than the Julang-1 deployed on the Xia-class. Part of the extension may also be related to the size of the reactor compartment. The U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence estimated in 2004 that the Jin-class, like the Xia-class, will have 12 missiles launch tubes (see figure below). Other non-governmental sources frequently claim the submarine will have 16 tubes. The satellite image is not of high enough resolution to show the hatches to the missile launch tubes.

|

Estimated Jin-Class SSBN Layout |

|

|

The U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence estimated in 2004 (bottom) that the Jin-class SSBN would have 12 missiles. |

The U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence estimated in December 2006 that China might build five Jin-class SSBNs. The estimate has been widely cited by non-governmental institutes and some news media as a fact, but the Pentagon’s annual report on China’s military forces from May 2007 did not repeat the estimate.

Background: Chinese Nuclear Forces and US Nuclear War Planning | Pentagon Report Ignores Five SSBN Projection

We Can Hear You Just Fine, It’s the Nuclear Missions that Don’t Make Sense

On Thursday 14 June, Dr. John Harvey, the Director of Policy Planning Staff of the National Nuclear Security Agency, spoke at the New America Foundation to explain the government’s plans for the future of nuclear weapons and the nuclear weapons manufacturing complex. While I disagree with him on virtually every point regarding nuclear weapons, I have a great deal of respect for Dr. Harvey because, after hearing his presentation, at least I know what I am disagreeing with, which is not true for every administration spokesman. I will comment on the description of the complex later; this entry comments on the government’s justifications for nuclear weapons.

When the House of Representatives Appropriations Committee recently zeroed out the money for the Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW), the accompanying report language criticized the administration for asking for money for nuclear weapons without adequate justification, without making their mission clear, and trying to justify nuclear weapons in a policy vacuum.

Dr. Harvey believes that the administration does, indeed, have a solid vision of a nuclear mission but contends that it has not been communicated well. However, because virtually everything he put forward has been known for some time—for example, I covered almost all the following missions in my paper Missions for Nuclear Weapons after the Cold War, it seems more likely that the communication is just fine. Congress has heard the administration’s story. They simply aren’t buying it. But it is always easier to believe that the other side is not hearing your argument rather than accept that their hearing is perfectly acute and they are rejecting your logic. Below I respond to a list of missions for nuclear weapons iterated by Dr. Harvey.

The first and biggest question concerns the size of our nuclear arsenal. In a rational world, numbers should follow from missions. Everyone agrees that numbers should now be lower than during the Cold War but how many nuclear weapons do we need?

Dr. Harvey said, “The President has said, and he has acted on this, that he seeks the lowest number of nuclear weapons consistent with our nation’s security and he has moved aggressively to that end since taking office. The nuclear weapons stockpile will be, by 2012, a factor of two of what it was when this administration took office and will be a factor of four below what it was at the end of the Cold War.”

As I discussed in Sizing Nuclear Forces, whenever anyone discusses nuclear weapon numbers in terms of reductions from Cold War levels they are using the Cold War as a baseline for judging nuclear numbers today. There is no justification for this, for two reasons. First, the world today is radically different from the Cold War. In fact, today many of the Cold War incentives for having nuclear weapons are exactly reversed. There is no more justification for comparing our nuclear weapons to Cold War numbers than there is for comparing the number of horses we had during the Spanish-American War. The comparison is not even wrong, it is simply irrelevant. Rather than start with irrelevant Cold War numbers and work down, let’s start with the assumption that we need none and work up from there. Second, even if there were some relevance to the Cold War, why should we think that nuclear weapons numbers during the Cold War were determined rationally? A reasonable person could make a reasonable argument that, during the Cold War, we had ten times more nuclear weapons than we needed, so if we have reduced nuclear weapons by a factor of four, we now have two and a half times more than we needed during the Cold War, and we probably still have ten times more than we need now.

In the context of the justification for US nuclear forces, Dr. Harvey said “Russia’s no longer an immediate threat.” I agree that this is true but it is not reflected in the numbers and deployments of US nuclear forces. In Missions, I argue that if we ignore what the administration says and look only at the numbers and deployment of US nuclear forces, there is one and only one mission that can justify having hundreds, even thousands, of multi-hundred kiloton nuclear bombs on hair-trigger alert, many on fast-flying, highly accurate missiles on forward-deployed submarines, just minutes from their targets: a surprise disarming first strike against Russian central nuclear forces. Politically, Russia may no longer be an immediate threat but, as our nuclear war planners recognize, Russian nuclear forces are the only threat that could end the United States as a society. This threat continues and, regardless of what we say, we appear to deploy forces to counter it. Within the current administration, arms control is so thoroughly discredited that no serious thought is given to eliminating this threat through mutually beneficial negotiation. If Russia is not the justification for the day-to-day deployment pattern of US nuclear forces, then there is no justification.

Dr. Harvey seems to pick the latter alternative when he says, “We no longer can predict where and when major new threats will emerge. Nuclear force planning is, thus, no longer threat based.” What this means is that, if North Korea, Iran, China, and Russia were taken over by Quakers tomorrow, we would not necessarily change our nuclear force posture one iota. Once we accept this, then all discussion ends because no justification for nuclear forces is offered and none is needed. We shall have nuclear weapons forever because we decide that, independent of threat, we need them. This puts the lie to administration claims that nuclear disarmament remains a long-term goal. If nuclear force planning is not threat- based then, even if the world were judged threat-free, we would still retain nuclear weapons. If nuclear weapons are justified even absent a threat under what circumstances could we ever get rid of them, even in theory?

The administration believes that we need to maintain nuclear forces and a nuclear infrastructure, again quoting Dr. Harvey, “Because we don’t know the threats, the threats will emerge in the future, we are uncertain about them, our infrastructure must be able to respond on a time scale commensurate with the emergence of threats.” To argue that the United States, with the most advanced technology, by far the world’s largest military-industrial base, and the world’s largest economy, has to keep a vast nuclear production line going because the Russians, Chinese, North Koreans, or the Iranians might be more responsive and might out produce us is simply absurd. Moreover, this assumes that the number of nuclear weapons required depends sensitively on the threat It does not. If we think through carefully how we might use nuclear weapons, does it make a difference if we have one hundred and the Russians have a hundred and one? Before we can make statements about needing to respond to potential threats with nuclear weapons, we need to explain how nuclear weapons are a response to potential threats and how many we need to respond. The administration has not done that. Their logic is that we need some, therefore we need thousands.

Dr. Harvey went on to list several more specific justifications for maintaining a nuclear arsenal, beginning with “Nuclear weapons prevent large scale wars of aggression. In the one case where they were used, they terminated a large scale war of aggression.” This is clearly not true. Nuclear weapons did not prevent the Korean War or the Vietnam War waged against a nuclear-armed United States. Nuclear weapons did not prevent smaller scale aggression like the Falklands War. China and Russia fought each other along their border when both had nuclear weapons. But, for the sake of argument, let’s assume that nuclear weapons might contribute to deterrence of large scale wars of aggression. This is a good example of the weakness of every argument in favor of nuclear weapons. While it may be true that nuclear weapons contribute to conventional deterrence, many things contribute to that deterrence, for example, potential political isolation, diversion of resources, destruction of industrial capacity, massive military fatalities, danger of domestic political upheaval, and loosing the war. So even if, as we have assumed, nuclear weapons contribute to preventing aggressive wars, what is their relative contribution and at what cost? And how do they prevent wars? By threatening nuclear Armageddon or by threatening to inflict pain greater than any gain from aggression. If the former, then do we want that mission? If the latter, then how many nuclear weapons do we need? Dozens? Finally, even the statement that the nuclear weapons ended World War II is no longer assumed.

The next justification for nuclear weapons is that “Nuclear weapons discourage the use of weapons of mass destruction against the United States and its allies.” Again, this may be true to some extent. But many things discourage the use of nuclear weapons. If North Korea used nuclear weapons against the United States, the U.S. would, I am absolutely certain, invade and occupy North Korea, Kim Jung Il, would not survive. The US might or might not use nuclear bombs in that military operation but, regardless, it would have little effect on the outcome and would make little if any difference to the North Korean deterrent calculation. Many things also contribute to that deterrence so what is the net contribution of using nuclear weapons for this role and what are the costs and risks? I am sure that nuclear bombs could be used as doorstops but that does not mean that stopping doors is desirable nuclear mission because a lot of other things can be used as doorstops with less risk.

Next Dr. Harvey says, “They [nuclear weapons] dissuade potential adversaries from engaging in nuclear arms races with the United States.” This is an incomplete statement at best. Clearly the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in arms races because of the other’s nuclear weapons. This is most likely a statement of what is often called the “lowered bar” argument. It is an argument for why we need thousands of nuclear weapons because if we had only hundreds then lesser powers, like China, might be tempted to compete with us, while they will not even try as long as we have thousands. While I cannot disprove this argument, it is utterly contrary to Chinese nuclear doctrine and behavior that has been consistent for three decades. Moreover, this argument disregards completely the potential role of mutually beneficial negotiated arms control agreements that could bring all the world’s nuclear arsenals down to very low levels.

Dr. Harvey even fit in the terrorist threat, saying “They won’t deter terrorists but they could deter rogue states from transferring nuclear warheads or materials to terrorists.” The logic here is just as empty as it is in the case of deterrence of large scale wars. Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that nuclear weapons do contribute some such deterrence. Given our overwhelming conventional superiority, don’t you think North Korea and Iran are already largely deterred? So the question is not whether they are deterred or whether nuclear weapons contribute to deterrence but what is the marginal contribution of nuclear weapons and what are the risks of having nuclear weapons and of legitimizing them for this mission? Dr. Harvey and the rest of the Bush Administration have yet to address these questions.

The next justification, “They assure allies who rely on US extended deterrence guarantees provided by our nuclear forces,” is true because it is a tautology. Again, even if nuclear weapons do assure our allies, there are many more effective ways to assure our allies. What is the marginal contribution? And what are the risks of using nuclear weapons for this mission. This is another doorstop argument.

Finally, Dr. Harvey concluded his list with, “More broadly, nuclear weapons serve as an insurance policy for an uncertain future.” This is, at best, an argument that we don’t have any really good arguments but we want nuclear weapons anyway. It would be persuasive if nuclear weapons were free. But they are not, neither to the taxpayer nor to the security of the world. Fire insurance on your house is almost always a good idea but what if the insurance policy itself had some chance of bursting into flames and burning your house down? One would have to make a careful assessment of risks. The insurance argument ignores the costs of nuclear weapons. It is a thoughtless assertion, not a reason.

Key Senate Vote on the Reliable Replacement Warhead Coming Up

On 6 June, the House Appropriations Committee eliminated funding for the Reliable Replacement Warhead [RRW] requested by the administration. [In an earlier blog entry, I discuss why the Reliable Replacement Warhead is a misnomer.] The report language is quite damning. I believe that the nuclear policy of the United States since the end of the Cold War has been, to put it charitably, absent-minded, programs have been sustained more by momentum than careful analysis. The House report recognizes that, almost two decades after the end of the Cold War, the United States does not have a plausible nuclear strategy and essentially puts a freeze on long-term spending until we develop one.

(more…)

The Stockpile Stewardship Program: Fifteen Years On

Nuclear weapons, while simple in principle, are technically complex devices with a multitude of components. As with any complicated piece of equipment, there may be concern that, over time, a weapon’s reliability could decline. To coordinate efforts to maintain the nation’s existing nuclear weapons, the Department of Energy developed a Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP). A recently released Federation of American Scientists Occasional Paper, The Stockpile Stewardship Program: Fifteen Years On (PDF), by FAS analysts Anne Fitzpatrick and Ivan Oelrich, reviews the status of the experimental devices that support the SSP, describes how each experiment is supposed to work, and identifies the problems that have been encountered.

All of the expensive SSP experiments were initiated because of the cessation of nuclear testing, with the expectation that they would be essential to maintaining the nuclear stockpile. The major components of SSP are all seriously over budget and seriously behind schedule but, even so, our scientists now have a much better understanding of nuclear weapons and how they age. Now the DOE is proposing moving away from indefinite stockpile stewardship to a “Reliable, Replacement Warhead,” which, if designed for simplicity and with broad performance margins, could avoid the need for the SSP experiments. It is fair then to ask just how essential these megaprojects continue to be.

The SSP supported three major experiments: the National Ignition Facility (NIF) to use laser beams to compress a hydrogen target to densities and pressures where fusion would occur; the Dual-Axis Radiographic Hydrodynamic Test (DARHT) Facility uses x-rays to follow the shape of sections of plutonium when they are compressed as they would be in a nuclear bomb; and the Accelerated Strategic Computing Initiative (ASCI)—renamed Advanced Simulation and Computing (ASC) — to build supercomputers and associated software to use the information from other experiments to model nuclear warheads and predict their behavior. Two other experiments later fell under the SSP: The Joint Actinide Shock Physics Experimental Research (JASPER) facility is a high speed gun used to study shock waves in plutonium and the Z-Machine, or Z-Accelerator, creates the x-ray intensity used to study nuclear explosive conditions.

The National Ignition Facility (NIF) was originally budgeted to cost just a shade over one billion dollars and to be finished four years ago. It is now expected to carry out its first experiments in 2010 and to cost more than another billion dollars to complete, greater than the original estimates of total cost. Based on unclassified sources, it appears that the connection between NIF and the current SSP is at best indirect. We believe that NIF could be ended without reducing the confidence in the existing nuclear stockpile.

The Dual-Axis Radiographic Hydrodynamic Test (DARHT) Facility is designed to have two, hence “dual-axis,” x-ray machines that look at a subcritical plutonium pit as it is compressed by conventional explosives. Only one axis is currently operating and is providing valuable information.

The computer effort, ASC, has also been plagued with problems but is different from the two big physics experiments because it never had a focus on one particular machine. Indeed, it is not at all clear when the ASC program will be “done.” Being able to model a nuclear weapon on a computer is one of the critical substitutes for nuclear testing. The Advanced Simulation and Computing (ASC) program has already made important contributions to understanding the behavior of nuclear weapons and reportedly has resolved some worrying questions.

The ASC initiative has supported the construction of several large supercomputers. To achieve the necessary speeds, thousands of central processing units, CPUs, have been linked together to operate in parallel. These ambitious development programs have all had problems. Construction on some computers was started but never completed while some computers suffered from low reliability because of their complexity. In many cases, Herculean hardware developments were not matched by development of software that could fully exploit the new machines’ capability. Even successes were short lived: the world’s fastest computer today will be overtaken by some rival within months or a year.

To the greatest extent possible, DOE should use new computer capability coming out of industry and the universities and focus its efforts on DOE-specific problems, and get a better balance between hardware and software. DOE must justify why it needs leading edge computers when that edge is inevitably overtaken within a year or two. A decade into the SSP, DOE knows that nuclear weapons are far more stable than initially feared, and our understanding of the aging and stability of nuclear weapons continues to increase. There can and should be less urgency to DOE computer development.

All of the SSP experiments, but NIF in particular, are promoted as a means to attract top new scientific talent to DOE and the SSP. FAS remains deeply skeptical. The universities and industry are now at the cutting edge of scientific and technical advance. Anecdotal evidence strongly suggests that newly minted scientists do not look to the DOE labs as their first choice for doing pioneering research. Yet even if NIF did contribute to this goal to some degree, it is far from being the most efficient means of applying those billions of dollars. The great majority of the resources going to NIF support engineering problems—related to lasers, clean rooms, and power supplies—that have nothing whatsoever to do with either nuclear weapons or basic physics. That money could have gone directly to support university research of interest to DOE or to create smaller but scientifically more interesting experiments within the labs.

The current approach to stockpile stewardship, careful surveillance and monitoring along with judicious replacement of parts, has maintained a nuclear stockpile that is safe and reliable. Of the three major experiments supported by SSP, ASC and DARHT are already making contributions. NIF is more uncertain, both its ultimate success and its contribution to our confidence in the stockpile. But even without NIF, the United States can maintain its existing nuclear weapons without a return to testing.

FAS Nuclear Weapon Stockpile Stewardship Report Released

Nuclear weapons, while simple in principle, are technically complex devices with a multitude of components. As with any complicated piece of equipment, there may be concern that, over time, a weapon’s reliability could decline. To coordinate efforts to maintain the nation’s existing nuclear weapons, the Department of Energy developed a Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP). A recently released Federation of American Scientists Occasional Paper, The Stockpile Stewardship Program: Fifteen Years On (PDF), by FAS analysts Anne Fitzpatrick and Ivan Oelrich, reviews the status of the experimental devices that support the SSP, describes how each experiment is supposed to work, and identifies the problems that have been encountered.

Pentagon China Report Ignores Five SSBNs Projection

|

|

How many SSBNs are China building? |

The Pentagon’s new annual report on Chinese military power ignores a recent projection made by the Office of Naval Intelligence that China may be building five new ballistic missile submarines. The projection has since become a public “fact” after being spread around the world by news papers and private web sites.

Several news papers said earlier today – after the DOD report was leaked to them – that it identified the five Jin-class (Type 094) nuclear ballistic missile submarines. One senior defense official even was quoted saying that when the Chinese “develop five vessels like this, they are making a statement.”

Yet the DOD report does not say that China is building five SSBNs. In fact, it doesn’t give any number projection whatsoever. Instead, it repeats the projection from last year’s report that the first new SSBN may become operational sometime before the end of the decade.

So What Did Naval Intelligence Say?

When the news media first reported in March that the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) said China is building five Jin-class SSBNs, I requested the ONI report under the Freedom of Information Act. It is always good to check the primary source. The released report consists of answers to eight questions from Seapower Magazine about the Chinese submarine force.

Although some news media described the ONI report as saying China is building five SSBNs, ONI’s language was more vague, saying that “a fleet of probably five TYPE 094 SSBNs will be built in order to provide more redundancy and capacity for a near-continuous at-sea SSBN presence.” To me this language suggested that ONI was making a projection. So I asked ONI if it could clarify whether the number five was an assumption or a fact. In other words, does ONI know that five SSBNs are under construction (or ordered), or was the sentence a projection for what China would have to build if it wanted to have a near-continuous SSBN presence at sea?

The response was: “ONI can neither confirm or [sic] deny that ‘five’ is an actual number.”

Now that’s bureaucracy! If China is building five SSBNs, and ONI’s declassified letter to Seapower Magazine says that five are under construction, why can’t ONI confirm that five are under construction?

So I sent the declassified ONI letter to the Chinese Embassy and asked if they could confirm or deny. Here is what ONI and the media say. Are you building five SSBNs or not? Sorry, came the reply, even if we wanted to help you, no one here even knows the answer to your question.

I guess lack of transparency is a problem on both sides of the Pacific.

What the DOD Report Says

Perhaps there is disagreement within the intelligence community about the Chinese SSBN program. Perhaps DOD wanted to tone down the report and decided to remove ONI’s number from the final version. ONI said that

“a TYPE 094″ could reach Initial Operating [sic] Capability (IOC) as early as 2008,” but the submarine reaching IOC is not necessarily the same as the weapon system (including the JL-2) becoming operational. The DOD report limits itself to predicting that China’s strategic nuclear forces by 2010 likely include the JL-2.

In stark contrast with previous annual reports, the new report doesn’t highlight cases of dramatic Chinse submarine operations. Earlier this year I reported that Chinese submarines actually don’t sail on very many patrols; The single Xia SSBN not at all. The new DOD report does mention the Song-class submarine that “broached the surface in close proximity” to the U.S. aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk in October 2006 “in waters near Japan.” But rather than using the incident to warn about Chinese submarines pushing further and further into the Pacific, DOD uses it to talk about safety, saying it “demonstrated the importance of long-standing U.S. efforts to improve the safety of U.S. and Chinese military air and maritime assets operating near each other.”

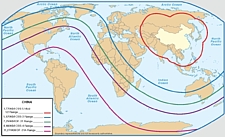

DF-31 (Almost) Operational

Another “almost operational” new weapons system is the long-awaited DF-31, which finally has achieved what the DOD report calls “initial threat availability.” This allegedly occurred in 2006 after more than 20 years in development. DF-31 was first test flown in 1999 and most recently in September 2006. Actual operational capability will likely be achieved in the near future, if it has not already happened, the report states. The DF-31 will probably replace the DF-4 and likely be used for regional targeting against Guam, India and Russia.

DF-31A Operational in 2007?

A surprising prediction in the DOD report is that the longer-range version of the DF-31 – the DF-31A – may achieve IOC in 2007. This is surprising because there are no authoritative public reports, to my knowledge, that the DF-31A has yet been flight tested. The world has yet to see a picture – even a drawing – of the DF-31A. The missile is expected to supplement and eventually replace 20 old silo-based DF-5As that have been used to target the United States and Russia since the 1980s.

After the 2006 FAS/NRDC report (p. 58) described inconsistent DOD range maps for the DF-5A, the authors of the new DOD report (p. 19) have corrected the map which now shows the DF-5A as having a greater range than the DF-31A. The inaccurate range map became an issue in 2006 because it caused many news media to errouneously report that the new DF-31A will give China the ability to target all of the United States for the first time, although China has had the capability to do so with the DF-5/A since the early 1980s.

| DOD Corrects Missile Range Map | |

|

|

| The 2007 DOD report corrects the faulty missile range map from the 2006 report (left), which caused news media to write that the DF-31A would allow China to target all of the United States for the first time. The error was pointed out in the 2006 FAS/NRDC report. | |

Other Ballistic Missiles

The DOD report states that China maintains 40-50 DF-21s, an increase in the projection from the 19-23 missiles reported in 2005 and 19-50 in 2006. The reason for the changed estimate is unknown, but could be due to deployment of more conventional DF-21s. Another possibility is the DF-21’s long-awaited taking over the role of the DF-3A. It may also indicate that the “dip” in DF-21 reported by DOD in 2005 and 2006 in fact never happened.

The build-up of short-range conventional missiles continues off Taiwan, the DOD report says, with about 900 missiles had been deployed by October 2006. With a rate of about 100 missile per year, the number may have increased to approximately 950 by now. Even so, the report observes that things have been relatively quiet in the Taiwan Strait for the past two years.

The Nuclear Weapons Forecast

The DOD report does not give actual numbers for its projection of Chinese nuclear forces. It doesn’t repeat the 2001 CIA projection of 75-100 warheads primarily targeted against the United States by 2015, or mention the earlier DOD projection of 60 ICBMs primarily targeted against the United States by 2010. The new DOD report only lists the types of weapons it expect will make up the Chinese strategic nuclear arsenal by 2010: DF-4, DF-5A, DF-21, DF-31, DF-31A, JL-1, JL-2 and nuclear cruise missiles.

Depending on how many of each of the older weapon types that will remain, and how many of the new types China will actually produce and deploy in the next three years, I carefully estimate that the DOD list for 2010 translates into a Chinese arsenal of some 150-200 deployed nuclear warheads. The intelligence community does not appear to think that any of the new missiles will be equipped with multiple warheads.

Chinese Nuclear Policy

The DOD report continues previous years’ assessments of Chinese nuclear policy but now concludes that China’s no-first-use nuclear policy is “ambiguous.” The reason is that Chinese “doctrinal material” includes “additional missions for China’s nuclear forces,” DOD says, such as deterrence of conventional attacks against the Chinese mainland, reinforcing China’s great power status, and increasing its freedom of action by limiting the extent to which others can coerce China. A vigorous Chinese debate about the future role of nuclear weapons, combined with the “introduction of more capable and survivable nuclear systems in greater numbers suggest Beijing may be exploring the implications of China’s evolving force structure, and the new options that force structure may provide,” DOD states.

FAS and NRDC Almost Mentioned

The DOD report describes many more interesting statements than can be mentioned here, but one is a vague reference to the work FAS and NRDC did in 2006 where we analyzed commercial satellite photos of Chinese military facilities, including the nuclear submarine base at Jianggezhuang. In response to this (and several other cases), the DOD report describes, Chinese authorities warned that “foreigners who illegally survey, gather and publish geographical information on China will be severely punished.” DOD’s assessment of this series of events is that it “may indicate that China is attempting to lay the groundwork to extend the concept of the ‘information blockade’ into space.” Watch out DigitalGlobe; your QuickBird satellite may be next.

Background: Chinese Nuclear Forces and US Nuclear War Planning | Chinese Nuclear Forces Guide | Office of Naval Intelligence Letter

Article: Pakistani Nuclear Forces, 2007

|

|

Shaheen 2 launch |

By Hans M. Kristensen

Pakistan is preparing its next-generation of nuclear-capable ballistic missile for deployment. A satellite image taken on June 5, 2005, shows what appears to be 15 Transporter Erector Launchers (TELs) for the medium-range Shaheen 2 fitting out at the National Defense Complex near Fatehjang approximately 30 kilometers southwest of Islamabad.

The vehicles were discovered as part of preparations for the latest Nuclear Notebook on Pakistani nuclear forces published in the May/June issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The Notebook is written by Hans M. Kristensen of the Federation of American Scientists and Robert S. Norris of the Natural Resources Defense Council.

The authors estimate that Pakistan currently has an arsenal of about 60 nuclear weapons. In the last five and a half years, Pakistan has deployed two new nuclear-capable ballistic missiles, entered the final development stages of a potentially nuclear-capable cruise missile, started construction of a new plutonium production reactor, and is close to completing a second chemical separation facility. As Pakistan completes development of two more nuclear-cable ballistic missiles and a cruise missile in the next few years, the nuclear arsenal will increase further.

| Pakistani government responds to blog:The government downplayed a report by an organization of American scientists that Pakistan is preparing its next generation nuclear-capable ballistic missile for deployment. “This is a speculative report which contains part fact and part fiction,” is how the spokesperson characterized the report.”Source: Dawn, “N-Capable Missiles,” May 11, 2007. |

The main driver for Pakistan’s nuclear modernization appears to be India’s nuclear build-up, although national prestige probably also is a factor. The two countries appear to be entering a new phase in their regional nuclear arms race with medium-range ballistic missiles gradually replacing aircraft as the backbone of their nuclear strike forces. In contrast to aircraft, ballistic missiles have a very short flight time and cannot be recalled once launched.

(more…)

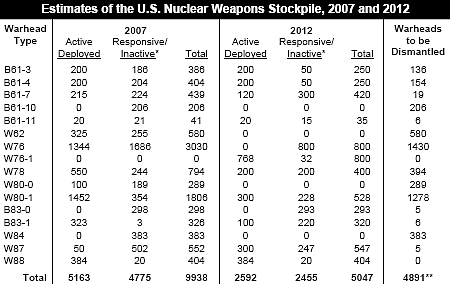

Estimates of the US Nuclear Weapons Stockpile, 2007 and 2012

|

Click on figure to open full fact sheet. For an updated stockpile estimate, go here.

The Bush administration announced in 2004 that it had decided to cut the nuclear weapons stockpile “nearly in half” by 2012, but has refused to disclose the actual numbers. Yet a fact sheet published by the Federation of American Scientists and Natural Resources Defense Council estimates that the stockpile will decline from approximately 9,938 warheads today to approximately 5,047 warheads by the end of 2012.

FAS and NRDC publish the fact sheet now because Congress is considering whether to approve a proposal by the administration to resume industrial production of new nuclear weapons, and because government officials have told Congress that production of new warheads will make it possible to reduce further the size of the stockpile in the future.

The fact sheet estimates are based on information collected by the authors over several decades about production, dismantlement and operation of US nuclear weapons.

(more…)

Article: Russian Nuclear Forces 2007

(Updated May 9, 2007)

At the beginning of 2007, Russia maintained approximately 5,600 operational nuclear warheads for delivery by ballistic missiles, aircraft, cruise missiles and torpedoes, according to the latest Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The Russian Notebook, which is written by Hans M. Kristensen of FAS and Robert S. Norris of NRDC, breaks down the Russian arsenal into roughly 3,300 warheads for delivery by strategic weapon systems and 2,300 warheads for delivery by tactical systems.

In addition to operational warheads, the Notebook estimates that Russia has a stock of roughly 9,400 warheads intended as a reserve or awaiting dismantlement, for a total stockpile of approximately 15,000 warheads.

The Importance of Arms Control (Section below updated May 9, 2007)

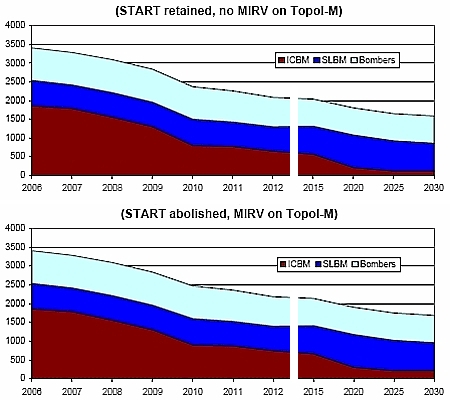

Russia and the United States apparently have decided not to extend the START agreement when it expires in 2009. The demise of the treaty will effect the number of warheads deployed on Russia’s ICBMs. Russia has already announced its intention to change the warhead loading on its Topol-M ICBMs.

Had START been extended, Russia’s arsenal of deployed strategic nuclear warheads would likely have declined to approximately 2,040 warheads by 2015 and roughly 1,590 warheads by 2030.

Once the treaty expires, however, and the Topol-M is equipped with three warheads (MIRVs, Multiple Independently Targeted Reentry Vehicles), the arsenal will reach roughly 2,210 warheads in 2015. Deployment of the silo-based Topol-M apparently will finish in 2020, in which case the warhead level will fall to approximately 1,810 warheads by 2030, depending on missile production rates for the mobile version of the Topol-M (see figure below).

|

Russian Strategic Nuclear Warheads 2006-2030 |

|

| The expiration of START in 2009 will have a significant impact on the future warhead level on Russia’s ICBMs. Beyond 2015, plans for the Russian force structure are uncertain. This projection a total of 84 Topol ICBMs on duty in 2015, and deployment of up to eight Borei-class SSBNs with 6 MIRVs per missile. The lower chart assumes up to 3 MIRVs on both silo and mobile Topol-M. |

Col. Gen. Nikolai Solovtsov, the commander of the Russian Strategic Rocket Forces (SRF), declared in December 2006 and again in May 2007 that Russia will begin to substitute the single warheads on Topol-M ICBMs with multiple warheads after START expires in 2009. He did not specify if that includes both the silo-based and mobile Topol-Ms. If only the silo-based Topol M is MIRVed, then Russia would have some 2,140 strategic warheads in 2015 and approximately 1,690 warheads deployed by 2030.

Current plans will leave Russia with roughly 146 ICBMs by 2015, a significant reduction from the 489 it had at the beginning of 2007, less than half of what the United States plans to have at that time. Russian planning also takes into consideration the Chinese posture, and the U.S. Air Force reported in March 2006 that work may be underway on a new strategic missile that can be deployed in both land-based and sea-based versions.

Russia apparently no longer believes it is necessary to maintain the same number of nuclear warheads as its potential adversaries, but still sees a significant strategic force as necessary. “For us,” President Vladimir Putin said in May 2006, “this idea of maintaining the strategic balance will mean that our strategic deterrence forces must be capable of destroying any potential aggressor, no matter what modern weapons systems this aggressor possesses.”

A Need For Additional Arms Control

Russia is currently, like the United States, making the decisions that will shape the long-term size and composition of its nuclear forces. Seventeen years after the Cold War ended, those decisions are still closely tied to the size and composition of the U.S. nuclear posture.

Putin proposed in June 2006 that START be replaced with a new treaty, and warned that “the stagnation we see today in the area of disarmament is of particular concern.” Although talks are underway with Washington on how to administer the strategic relationship after 2009, START apparently will not be extended.

The governments of both countries urgently need to articulate and decide on a new phase of arms control that will replace the open-ended, ad hoc nuclear planning of today with a framework for how to get to very low numbers with the medium-term goal of concluding the nuclear era.

Background: Russian Nuclear Forces 2007 | Status of World Nuclear Forces |

New US Navy Report on Chinese Navy

Despite frequent complains about lack of transparency in Chinese military planning, a new report from the Office of Naval Intelligence – recently described in the Washington Times and subsequently released to the Federation of American Scientists in response to a Freedom of Information Act request – boasts a high degree of knowledge about meticulous details of the Chinese navy’s operations, training, personnel and regulations.

The details in the report China’s Navy 2007 are many but unfortunately largely superfluous to the main answers many want to hear from the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) and other intelligence agencies: How are Chinese naval forces and operations evolving, and what do the changes mean?

Questionable Reporting

Unfortunately, some have already (mis)used the ONI report to hype fear that China is rising and out to get us. One example is the Washington Times, which last week described the report findings in a highly selective manner. Despite many unknowns about China’s military modernization and intentions, the paper’s description only included excerpts that indicate a threat or worrisome development. Moreover, the paper appears to have distorted the ONI report’s description of the Chinese submarine force’s importance: “China’s submarine forces are given ‘first priority’ of all branches of the navy, it states.”

But that’s not what the ONI report states. In fact, “first priority” as quoted by the Washington Times does not appear in the report at all. What the report says is very different: “The PLA Navy’s submarine forces…are generally listed as first in protocol order among the PLAN’s five branches.”

Being listed first in the protocol order is not the same as being the “first priority” of all the navy branches. According to the RAND Cooperation’s reference book The People’s Liberation Army as Organization:

| “PROTOCOL ORDER IN THE PLA: The PLA [People’s Liberation Army] is a very protocol oriented institution. When the PLA lists its military regions, services, service branches, administrative organizations, or its key personnel, the lists are almost always in protocol order, what the PLA calls organizational order (zuzhi xulie). The first criterion is generally the date a particular organization was established. For example, the order of the three services (junzhong) is always Army (August 1927), Navy (April 1949), and Air Force (November 1949). Since the Second Artillery Corps (July 1966) is technically a branch/service arm (bingzhong), and is usually not listed with the services….Therefore, the protocol order is more of an administrative tool today rather than a reflection of priority within the hierarchy.” (Emphasis added) |

What the ONI Report Does (and Doesn’t) Say

In contrast with the threat-focused style of the Washington Times reporting, the ONI report purports to have a much broader objective to “better understand the world’s fastest growing maritime power and its means of naval action and thereby foster a better understanding of China’s Navy.” The report observes up front that the enhanced naval power sought by China “is meant to answer global changes in the nature of warfare and domestic concerns about continued economic prosperity.” The drive to build a military component to protect the means of economic development, ONI states, “is one of the most prevalent historical reasons for building a blue water naval capability.”

Part of what has triggered the Chinese modernization is the extraordinary military capabilities that the United States have developed and deployed and demonstrated over the past two decades. The point is not that the United States is to blame and China just an innocent victim, but that all military modernization influences potential adversaries.

To that end the most interesting aspect about the ONI report may not be so much what it says but what it leaves out. Missing are many of the key developments that most concern US military planners and lawmakers, and many of the developments that are ignored by those who hype the Chinese “threat.”

For example, the ONI report does not include new information about the size of the Chinese navy. Instead it reprints a brief overview from the 2006 DOD report Military Power of the People’s Republic of China. Nor does the ONI report describe the construction of several new types of submarines, including the Type 093 nuclear-powered attack submarine and the Type 094 ballistic missile submarine.

Likewise, the ONI report begins with reprinting portions of two Chinese government documents, one of which states that the Chinese navy’s “capability of nuclear counter-attacks has also been enhanced.” This refers to China’s current possession of a single Xia-class ballistic missile submarine, but the ONI leaves out any information about what that enhancement actually is.

The other Chinese government statement used describes that the Chinese navy is “enhancing its capabilities in…nuclear counterattacks.” This is a hint that China is building a new class (Type 094 or Jin-class) of ballistic missile submarines that will be equipped with the long-range Julang-2 ballistic missile. Yet the ONI report does not give any details about the status of those programs much less what they mean for the Chinese navy or Chinese intentions.

In addition, the ONI report contains a very detailed description of the various categories of training used by the Chinese submarine force, yet it doesn’t mention submarine patrols with one word. The omission is curious because the report describes that Chinese submarines in the late 1970s began conducting independent sustained operations in the Pacific, and that “long-range navigation training is an important overall type of training for submarines.” So why leave out the important fact that the number of patrols have declined since 2000 rather than increased with the acquisition of more capable submarines?

To that end, the ONI report describes how the “basic hands-on and crisis-management training for strategic-missile submarines that cannot be conducted while the submarine is navigating underwater for long periods of time must be conducted on shore.” Yet it leaves out the important piece of information that China’s missile submarine Xia has never conducted a patrol.

Apparently, too little transparency is not only a problem in the Chinese military.

Balanced Reporting

One week before the Washington Times hyped the ONI report, the nominated commander of Pacific Command, Admiral Timothy J. Keating, testified before the Senate Armed Services Committee where he dismissed alarmist reports of recent gains in Chinese submarine development.

“If the reports are fairly accurate, they are well behind us technologically. We enjoy significant advantages across the spectrum of defensive and offensive systems, in particular undersea warfare,” he said according to Taipei Times. In an interview with the paper, Keating added: “Should it become necessary for us to put our forces [in harm’s way], the development of Chinese submarines are [sic] a concern to us, but it is hardly an insurmountable concern.”

Admiral Keating’s testimony was not covered by the Washington Times.

Breaking the cycle of military modernizations that trigger military modernizations is perhaps the biggest challenge in US-Chinese relations. Balanced reporting is another.

Background: China’s Navy 2007 | China Naval Modernization | FAS/NRDC Report

Small Fuze – Big Effect

“It is not true,” British Defence Secretary Des Browne insisted during an interview with BBC radio, that a new fuze planned for British nuclear warheads and reported by the Guardian will increase their military capability. The plan to replace the fuze “was reported to the [Parliament’s] Select Committee in 2005 and is not an upgrading of the system; it is merely making sure that the system works to its maximum efficiency,” Mr. Browne says.

The minister is either being ignorant or economical with the truth. According to numerous statements made by US officials over the past decade, the very purpose of replacing the fuze is – in stark contrast to Mr. Browne’s assurance – to give the weapon improved military capabilities it did not have before.

The matter, which is controversial now because Britain is debating whether to build a new generation of nuclear-armed submarines, concerns the Mk4 reentry vehicle on Trident D5 missiles deployed on British (and US) ballistic missile submarines. The cone-shaped Mk4 contains the nuclear explosive package itself and is designed to protect it from the fierce heat created during reentry of the Earth’s atmosphere toward the target. A small fuze at the tip of the Mk4 measures the altitude and detonates the explosive package at the right “height of burst” to create the maximum pressure to ensure destruction of the target. The new fuze will increase the “maximum efficiency” significantly and give the British Trident submarines hard target kill capability for the first time.

US Statements About Enhanced Capability

Unlike the British government, US officials and agencies have been very clear that the new fuze is not merely a replacement but a significant upgrade that will give the Mk4 significant military capabilities. The Department of Energy’s Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan from 1997 stated that the whole purpose of developing a new fuze in the first place was to “enable [the] W76 to take advantage of [the] higher accuracy of the D5 missile.”

At about the same time, the head of the US Navy’s Strategic Systems Command, Rear Admiral George P. Nanos, explained in The Submarine Review that the “capability for the [existing] Mk4…is not very impressive by today’s standards, largely because the Mk4 was never given a fuze that made it capable of placing the burst at the right height to hold other than urban industrial targets at risk.” But “with the accuracy of D5 and Mk4, just by changing the fuse in the Mk4 re-entry body, you get a significant improvement,” Admiral Nanos stated. In fact, “the Mk4, with a modified fuze and Trident II accuracy, can meet the original D5 hard target requirement.”

| Trident Mk4A Reentry Vehicle |

|

| The US Navy is saying – and the British government is denying – that a new fuze for the Mk4 reentry vehicle will increase the capability against hard targets. |

For US war planners, this improvement was necessary because the main US hard target killer, the MX Peacekeeper ICBMs with high-yield W87 warheads, were being retired as a result of the never-ratified 1992 START II treaty and the 2002 Moscow Treaty (SORT). The last Peacekeeper stood down in 2005. Some of the W87 are now being backfitted unto the Minuteman III ICBMs with a new guidance system to retain ICBM hard target kill capability. The Navy has a dedicated hard target kill W88 warhead on some of its D5 missiles, but with the new fuze on the W76-1/Mk4A the hard target kill capability will increase significantly. The first W76-1/Mk4A is scheduled to be delivered in September 2007.

Implications for British Deterrence

Admiral Nanos’ statement implies that British Trident submarines have never had hard target kill capability “because the Mk4 was never given a fuze that made it capable of placing the burst at the right height to hold other than urban industrial targets at risk.” With the new fuze, however, the British Trident submarines “can meet the original D5 hard target requirement,” and hold at risk the full range of targets.

So why does the British upgrade come now? After all, British nuclear submarines have cruised the oceans for decades with less capable fuzes and still ensured, so it has been said, Britain’s survival and made “significant contributions” to NATO’s deterrence.

There are several possibilities. British nuclear planners may have successfully argued that they need more accurate nuclear weapons to better deter potential adversaries. That is the dynamic the created in the Trident system during the Cold War. Since then, Britain has moved from a Soviet-focused deterrent to a “Goldilocks doctrine” today aimed against three incremental sizes of adversaries: Russia, “rogue” states, and terrorists.

Another possibility is that it may be a result of Britain not having an independent deterrent. Rather than designing and building its nuclear missiles itself, British leases them from the US missile inventory. The warhead installed on the “British” missiles is believed to be a modified – but very similar – version of the American W76. But the reentry vehicle that contains the explosive package appears to be the same: the Mk4. And since the US is upgrading its Mk4 to the Mk4A with the new fuze, Britain may simply have gotten the new capability with its existing lease.

Whatever the reason, the British government’s denial is clearly flawed. If the government believes so strongly that a nuclear deterrent is still necessary, why be so timid about its new capability? After all, what is the new capability good for if the potential adversaries can’t be told about it? And if the British government believes in the nuclear deterrent, then it has to play the deterrence role and be honest about it, and not – as it does now – pretend to be a nuclear disarmer while secretly enhancing its nuclear weapons capabilities.