Chinese Submarine Patrols Doubled in 2008

|

| Chinese submarines conducted 12 patrols in 2008, the highest ever. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Chinese attack submarines sailed on more patrols in 2008 than ever before, according to information obtained by Federation of American Scientists from U.S. naval intelligence.

The information, which was declassified by U.S. naval intelligence in response to a Freedom of Information Act request from the Federation of American Scientists, shows that China’s fleet of more than 50 attack submarines conducted 12 patrols in 2008, twice the number of patrols conducted in 2007.

China’s strategic ballistic missile submarines have never conducted a deterrent patrol.

Highest Patrol Rate Ever

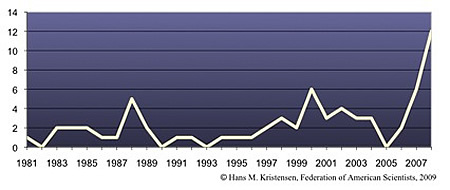

The 12 patrols conducted in 2008 constitute the highest patrol rater ever for the Chinese submarine fleet. They follow six patrols conducted in 2007, two in 2006, and zero in 2005. China has four times refrained from conducting submarine patrols since 1981, and the previous peaks were six patrols conducted in 2000 and 2007 (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1: |

|

| Chinese attack submarines conducted 12 patrols in 2008, double the number from 2007. Yet Chinese ballistic missile submarines have yet to conduct a deterrent patrol. |

.

While the increase is submarine patrols is important, it has to be seen in comparison with the size of the Chinese submarine fleet. With approximately 54 submarines, the patrol rate means that each submarine on average goes on patrol once every four and a half years. In reality, the patrols might have been carried out by only a small portion of the fleet, perhaps the most modern and capable types. A new class of nuclear-powered Shang-class (Type-093) attack submarines is replacing the aging Han-class (Type-091).

Few of the details for assessing the implications of the increased patrol rate are known, nor is it known precisely what constitutes a patrol in order for U.S. naval intelligence to count it. A request for the definition has been denied. It is assumed that a patrol in this case involves an extended voyage far enough from the submarine’s base to be different from a brief training exercise.

In comparison with other major navies, twelve patrols are not much. The patrol rate of the U.S. attack submarine fleet, which is focused on long-range patrols and probably operate regularly near the Chinese coast, is much higher with each submarine conducting at least one extended patrol per year. But the Chinese patrol rate is higher than that of the Russian navy, which in 2008 conducted only seven attack submarine patrols, the same as in 2007.

Still no SSBN Patrols

The declassified information also shows that China has yet to send one of its strategic submarines on patrol. The old Xia, China’s first SSBN, completed a multi-year overhaul in late-2007 but did not sail on patrol in 2008.

|

| Neither the Xia-class (Type-092) ballistic missile submarine (image) nor the new Jin-class (Type-094) have ever conducted a deterrent patrol. |

.

The first of China’s new Jin-class (Type-094) SSBN was spotted in February 2008 at the relatively new base on Hainan Island, where a new submarine demagnetization facility has been constructed. But the submarine did not conduct a patrol the remainder of the year. A JL-2 missile was test launched Bohai Bay in May 2008, but it is yet unclear from what platform.

Two or three more Jin-class subs are under construction at the Huludao (Bohai) Shipyard, and the Pentagon projects that up to five might be built. How these submarines will be operated as a “counter-attack” deterrent remains to be seen, but they will be starting from scratch.

China Defense White Paper Describes Nuclear Escalation

|

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A Chinese government defense white paper for the first time describes how China’s nuclear forces would gradually be brought to increased levels of alert during a crisis to deter an adversary and retaliate to nuclear attack.

The paper describes a growing portfolio of deterrence and counterattack capabilities with an ambitious agenda to control war situations with a more flexible deterrent and strategy.

Despite shortcomings, the paper provides a new level of Chinese transparency about its forces and planning.

Nuclear Escalation Phases

The white paper describes how the Second Artillery Corps (or Force, the term used by the paper) would change the operational status of the nuclear forces at different levels of crisis and conflict. Three levels of escalation are described:

Peacetime: Under normal circumstances – “in peacetime” – China’s nuclear missiles are “not aimed at any country.” The term “not aimed at any country” seems borrowed from U.S. terminology where it refers to the absence of targeting data in a missile’s guidance system rather than the alert level of the weapon. It has been assumed for many years that Chinese warheads were not mated with liquid-fuel missiles under normal circumstances (The situation with solid-fuel missiles has been less clear but might be similar).

|

Figure 1: |

|

|

A warhead section is mated with a DF-3 liquid-fuel ballistic missile. Chinese nuclear warheads are thought to be stored separate from the missiles in peacetime. Image: web |

Nuclear crisis: If China comes under a nuclear threat, the nuclear missile force of the Second Artillery Corps “will go into a state of alert, and get ready for a nuclear counterattack to deter the enemy from using nuclear weapons against China.” In this phase, depending on the situation, mobile missiles would probably be dispersed to their deployments areas and presumably be aimed at the particular threat. If nuclear warheads were not already mated, they would be so too.

Nuclear attack: If China is attacked with nuclear weapons, the nuclear missile force of the Second Artillery Corps “will use nuclear missiles to launch a resolute counterattack against the enemy either independently or together with the nuclear forces of other services.” The “nuclear forces of other services” probably refers to the navy’s SSBNs and the Air Force’s bombers (see below).

Nuclear Missile Submarines

The submarine force is said to be equipped with “nuclear-powered strategic missile submarines,” a vague reference to the small fleet of perhaps 3-4 Jin-class SSBNs under construction.

The first was spotted at Xiaopingdao Submarine Base in 2007 and Hainan Island in 2008, the old Xia ended a multi-year overhaul at Jianggezhuang Submarine Base in 2008, although its operational condition is unknown.

The mission of the SSBNs is said to be “strategic deterrence and strategic counterattack,” which probably means non-alert operations in peacetime, increased readiness in a crisis, and the ability to counterattack in wartime. The paper states that the ability to counterattack is being improved, probably a reference to the new JL-2 SLBM on the Jin-class.

The mission description is vague and inconsistent. Whereas the section describing the navy’s development history uses the term “strategic deterrence and strategic counterattack,” the general force building section states that, “the submarine force possesses underwater anti-ship, anti-submarine and mine-laying capabilities, as well as some nuclear counterattack capabilities.”

Why the authors have used “strategic deterrence” in one part but only “nuclear counterattack capabilities” in the second part is unclear. Whether it is a vague reference to a nuclear cruise missile capability being added to some attack submarines is unknown, but absent any additional information might just be a matter of language.

A New Air Force Capability?

The Air Force section is interesting because it describes a “transition from territorial air defense to both offensive and defensive operations.” While much of this has to do with the introduction of new and more capable fighter and bomber aircraft and new concepts of operations, the white paper also describes “certain capabilities to execute long-range precision strikes and strategic projection operations.”

The force building section adds that in addition to traditional air force missions such as strikes and air defense, the transition involves increasing the capabilities for “strategic projection, in an effort to build itself into a modernized strategic air force.”

A small portion of China’s H-6 bombers have for decades been thought to have a secondary nuclear mission with gravity bombs, but the language in the white paper appears to go beyond that and might refer to some of the H-6 bombers being upgraded to carry a new long-range cruise missile intended for land-attack missions.

Most new cruise missiles will carry conventional explosives, but at least one – possibly the DH-10 – might also have a nuclear capability. The operational status of a nuclear cruise missile is highly uncertain and may initially be ground-launched, yet the U.S. Defense Department’s 2008 projection for Chinese nuclear forces vaguely referred to “new air- and ground-launched cruise missiles that could perform nuclear missions” and therefore “improve the survivability, flexibility, and effectiveness of China’s nuclear forces.”

Whether that means China is deploying nuclear cruise missiles remains to be seen.

Nuclear Weapons Capabilities

The paper describes that China over the past decades has built a weaponry and equipment system with both nuclear and conventional missiles, both solid-fueled and liquid-fueled missiles, with different ranges and “different types of warheads.”

The safety and surety features of those warheads and the personnel that handle them have been changed, the white paper states. For example, safety measures have been established to “avoid unauthorized and accidental launches,” measures that are needed for enhancing security but probably also for enhancing command and control of the weapons in the increasingly flexible scenarios the paper describes.

|

Figure 2: |

|

| Do Chinese solid-fuel DF-31 and DF-31A long-range ballistic missiles carry nuclear warheads in peacetime? In a crisis they most likely would under the escalation procedures described in the 2008 Defense White Paper. Image: CCTV7 |

.

Nuclear Weapons Policy

The white paper states that new military strategic guidelines have been issued that are aimed at “winning local wars in conditions of informationization.” The new guidelines stress “deterring crises and wars,” and “effectively control war situations,” and calls for “the building of a lean and effective deterrent force and the flexible use of different means of deterrence.”

Hovering above that evolution is a long-held policy of no-first-use of nuclear weapons, a self-defensive nuclear strategy, and a pledge never to enter into a nuclear arms race with any other country.

The good news about the no-first-use policy is that it is explicitly nuclear focused, and that China does not yet appear to have made it conditional on specific situations such as conventional attacks against China’s nuclear forces. This is important because some Chinese officials privately insist that a conventional attack against China’s nuclear forces would be considered a nuclear attack and the no-first-use policy therefore not a limiting factor in China’s response.

The not so good news is that the no-first-use policy in certain situations doesn’t seem credible. The pledge to “not be the first to use nuclear weapons at any time and in any circumstances” means that if an adversary invaded China and threatened the survival of the state, China’s nuclear forces would not be used as long as the invader did not use nuclear weapons. Hardly a credible policy.

Likewise, the pledge to “unconditionally not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states or in nuclear-weapon-free zones,” means that if the United States staged strikes against China from Japan or South Korea, Chinese nuclear weapons would not be used against U.S. bases in those countries. In that credible?

Despite these “credibility issues” in Chinese nuclear policy, the white paper is noteworthy because it indicates that China – unlike the other nuclear weapon states – has not yet fallen for the temptation to broaden its nuclear policy to deter all forms of weapons of mass destruction. The policy seems entirely focused on deterring and responding to nuclear attacks.

The white paper also states that China would like the nuclear weapon states to stop research into and development of new types of nuclear weapons, reduce the role of nuclear weapons in their national security policy, and reduce their nuclear arsenals. Those are good policy goals but they ring hollow given that China is busy deploying new nuclear weapons with new nuclear warheads and is the only of the five original nuclear weapon states that is thought to be increasing its nuclear arsenal.

As China increases its capabilities and pursues a more flexible deterrent posture, there is a risk that its policies will be modified too. With increased flexibility in capability tends to come increased flexibility in mission.

Oh, and in case you wondered: while the U.S. military plans against “red forces,” the Chinese plan against “blue forces.” Some things never change.

The Minot Investigations: From Fixing Problems to Nuclear Advocacy

|

| The second report from the Schlesinger Task Force goes beyond fixing nuclear problems to promoting new nuclear weapons. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

For nuclear weapon advocates, the Minot incident in August 2007, where the Air Force lost track of six nuclear-armed cruise missiles for 36 hours, was a gift sent from heaven. No other event short of a nuclear attack against the United States could have provided a better opportunity to breathe new life into the declining nuclear mission.

But where is the line between fixing problems and advocacy?

Although the latest report from the Secretary of Defense Task Force on DOD Nuclear Weapons Management, also known as the Schlesinger report, contains many reasonable recommendations to ensure that the Services and agencies are capable of fulfilling the nuclear mission, it is also sprinkled with recommendations that have more to do with promoting nuclear weapons.

And it makes some remarkable claims about the deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe.

Fuzzy Tasking Leads to Fuzzy Focus

The leap from investigation to promotion is an unfortunate byproduct of the tasking Defense Secretary Robert Gates provided to the Schlesinger Task Force in June 2008. That letter not only directed the task force to examine accountability and control procedures for nuclear weapons to “sustain public confidence in the safe handling of DoD nuclear assets,” but also to “bolster a clear international understanding of the continued role and credibility of the U.S. nuclear deterrent.”

The task force appears to have taken the second objective a bit far.

Rather than being focused on fixing the problems that resulted in the Minot incident and several other events, the report reads like a second volume of the Defense Science Board (DSB) report from 2006 in which disgruntled nuclear advocates lamented a decline in support for the nuclear mission.

The Schlesinger report is, at times, a phenomenal concoction of Cold War nuclear jargon and claims made without presenting any evidence or analysis to support their continued validity. The report skips over the expansion from deterring nuclear to deterring all forms of WMD (it doesn’t even list the difference), and it suggests that U.S. nuclear weapons even have a mission against “violent extremists and nonstate actors.”

Nuclear Promotions

Anticipating that some elements of the nuclear posture will probably be cut in the future as a result of the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission, the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, and an potential arms control agreement with Russia, the Schlesinger report correctly states that such cuts “should be a reflection of policy decisions at the highest level rather than a result of Service preferences or budgetary concerns.” Given this conclusion, it is all the more noteworthy how the Schlesinger report throws itself into a blunt advocacy of nuclear posture issues that clearly should be the purview of the next administration.

Examples of posture recommendations that go beyond “accountability and control procedures” to promotion of new nuclear weapons include:

* Develop follow-on capabilities that can come online prior to expiration of the nuclear Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM-N) effectiveness or, should there be a gap, extend the TLAM-N service life commensurate with introduction of the new system.

* The Secretary of Defense should direct the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to develop validated operational requirements for modernizing or replacing the capabilities now provided by Dual-Capable Aircraft (DCA), Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM), and TLAM-N.

* Review and update the concept of operations for the TLAM-N to make it a more viable and responsive option for national leadership.

Clearly, these appear to be future posture decisions that are beyond the job the Schlesinger Task Force was asked to do.

The Extended Deterrence Confusion

The TLAM and DCA are weapons that are weapon systems that are both have roles in the extended deterrence mission. Yet the authors of the Schlesinger report repeatedly confuse the description of what extended deterrence means. Sometime they describe it as forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. At other times they describe as a nuclear umbrella extended over allies from afar.

For example, in the opening paragraphs of the section called “The Special Case of NATO,” the report concludes: “As long as NATO members rely on U.S. nuclear weapons for deterrence, no action should be taken to remove them without a thorough and deliberate process of consultation.”

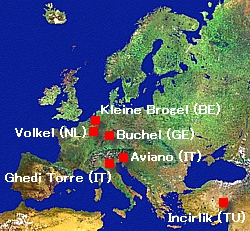

Certainly NATO members should be consulted, but withdrawing “them” (which refers to the roughly 200 tactical nuclear bombs deployed in five European countries) hardly constitutes eliminating the entire U.S. nuclear weapons deterrent. A withdrawal from Europe would not be the end of the nuclear umbrella, as the Schlesinger report indicates, which could be continued by long-range forces just like it was in the Pacific after tactical nuclear weapons were withdrawn from South Korea in 1991.

|

Figure 1: |

|

|

About 200 U.S. tactical nuclear weapons are deployed at six bases in five European countries. After the Blue Ribbon Review report in 2008 concluded that it would take considerable additional resources for security at European nuclear sites to meet DOD standards, the Schlesinger report now concludes that everything is fine. |

The Deployment in Europe

One of the most interesting parts of the report concerns the deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. Unfortunately, the European section is filled with sweeping statements and conclusions about the virtues of the deployment that are not supported by any accompanying analysis except deterrence jargon and echoes from the Cold War:

“Much of the deterrent value of NATO’s DCA deployment is derived from their in-theater presence, demonstrating and maintaining the capability to employ them. This creates in the minds of potential aggressors an unacceptable level of uncertainty concerning the success of any contemplated attack on NATO. This deterrent effect cannot be created by simply having nuclear weapons stored and locked up or relying exclusively on “over-the-horizon” nuclear delivery capabilities.”

It is? It does? It cannot? Why?

Many actually do believe – including apparently U.S. European Command (EUCOM) – that the deployment in Europe is not necessary anymore. But the authors of the Schlesinger report do not share that view and they spend a good portion of the report criticizing EUCOM for believing that “deterrence provided by USSTRATCOM’s strategic nuclear capabilities outside of Europe are more cost effective” and that “an ‘over the horizon’ strategic capability is just as credible.”

That assessment sounds pretty sound to me. But instead of accepting EUCOM’s assessment that forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe is not necessary for extended deterrence and a burden on real-world nonnuclear operations, the Schlesinger report brushes aside EUCOM’s “narrow assessment.” It is a much broader issue, the authors’ claim, about Russia, flexible regional nuclear deterrence (although the weapons are not targeted against anyone), and a trans-Atlantic link between Europe and the United States. But as far as the tactical nuclear weapons in Europe are concerned, that link was a Cold War link between a Soviet conventional invasion of Europe and U.S. strategic nuclear weapons, a concept that is getting a little dated. And if the glue in NATO depends on forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons, then I think the alliance is in deeper trouble that people normally think.

Interestingly, one person who shares the view of EUCOM was recently selected to become national security advisor to President-elect Barack Obama: General James L. Jones. When he was the head of EUCOM and Supreme Allied Commander Europe in 2005, the New York Times reported that Jones “has privately told associates that he favors eliminating the American nuclear stockpile in Europe, but has met resistance from some NATO political leaders.”

|

Figure 2: |

|

| Unlike the authors of the Schlesinger report, General (Ret.) James Jones, who is President-elect Obama’s national security advisor and former Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR), reportedly favors a withdrawal of tactical nuclear weapons from Europe. |

.

Shortly before the U.S. in 2005 and 2006 secretly withdrew half of the nuclear weapons from Europe – including all weapons from the United Kingdom, Jones told a Belgian Senate committee: “The reduction will be significant. Good news is on the way.” NATO sources attempted to downplay the issue by claiming Jones had not mentioned nuclear weapons specifically, but the Belgian government later stated for the record that, “the United States has decided to withdraw part of its nuclear arsenal deployed in Europe….” German weekly Der Spiegel followed up by asking “whether German nuclear weapons sites will benefit from Gen. Jones’ ‘good news.’” They did: all weapons were withdrawn from Ramstein Air Base.

The authors also leave out that the European political landscape on the tactical nuclear weapons issue has changed dramatically since the justifications the authors use were concocted. An overwhelming majority of the public today favors a withdrawal, the German government parties favor a withdrawal, and the Belgium Senate has unanimously called for a withdrawal. While ignoring those views, the Schlesinger report instead refers to anonymous allies who allegedly have expressed concern over calls for a unilateral withdrawal.

Who are those allies? From what department in the government bureaucracies did the officials that sent those signals come from? Whenever I mention these “allied concerns” during conversations with European government officials, they always smile because they know quite well that what’s a play here is a small group of nuclear bureaucrats deep within the ministries of defense who are defending their own turf. [There are some hints here; none of them seem to be directly related to the deployment in Europe].

Extended Deterrence as Nonproliferation

Another prominent assertions in the NATO section of the report is that by holding a nuclear umbrella over allied countries – by promising to retaliate with nuclear weapons if they are attacked by nuclear weapons (or weapons of mass destruction, as the authors say) – U.S. nuclear weapons prevent allied countries from developing nuclear weapons themselves. This sure sounds good and is a popular claim, but how widespread is this effect.

The report states that the United States has “extended its nuclear protective umbrella to 30-plus friends and allies.” The countries are not identified, but most of them are known:

NATO (25): Albania, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Turkey.

ANZUS (2): Australia, New Zealand.

Northeast Asia (3): Japan, South Korea, Taiwan .

That’s 30, so who are the remaining -plus countries are that the authors say are covered by the U.S. umbrella? France and the U.K. obviously don’t need it because they have their own nuclear deterrents. So do Israel and India. Are there non-nuclear allies in the Middle East that are under the umbrella?

|

Figure 3: |

|

|

A NATO briefing in 2006 acknowledged serious pressure for a withdrawal of nuclear weapons. Click image to download. |

The Schlesinger report recommends that the views of those 30-plus countries should be included in U.S. nuclear policy guidance documents. That would indeed be interesting, given that many of the countries actually have policies that favor a total withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Europe, elimination of non-strategic nuclear weapons, and total nuclear disarmament – political realities the report completely leave out.

Although all 30-plus are used to underscore the virtue of extended deterrence, how many of them would seriously consider acquiring their own nuclear weapons if things changed? Denmark? Iceland? Lithuania? Luxembourg? Portugal? New Zealand? Seriously! Only a few of the 30 are normally considered potential nuclear weapon proliferators: Germany, Japan, and perhaps South Korea.

It is probably also worth mentioning that two NATO countries – France and the United Kingdom – decided years ago to go nuclear even though the United States had thousands of nuclear weapons deployed to defend them. The report doesn’t mention why the NATO countries would not feel sufficiently protected by British or French nuclear forces in Europe.

The report also doesn’t mention that the United States since the early-1990 has maintained a nuclear umbrella over its allies in Northeast Asia without it requiring forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in those countries. Why is it possible to maintain extended deterrence with long-range nuclear weapons in the Pacific but not in Europe?

Conclusions and Remarks

Obviously the virtues of extended deterrence and the deployment in Europe are a little more nuanced than the Schlesinger report purports. But the central proposition that NATO and extended deterrence will go down the tube if tactical nuclear weapons were withdrawn from Europe seems preposterous.

It asks us to believe that if NATO really were attacked or threatened with nuclear (or, for those who believe nuclear weapons are also needed to deter chemical or biological weapons, WMD), U.S., British, and French ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), land-based missiles (ICBMs), and long-range bombers – along with all of NATO combined conventional military might (which is far more credible as a deterrent) – would sit idle in their bases because the political and military leaders somehow were incapable of reacting.

The decline in nuclear prowess that the Minot investigations have detected hasn’t simply happened because overstretched officers failed to do their job or the nation lost faith in nuclear weapons. It is a symptom, a hint. It has declined because nuclear weapons are no longer center and square to the national security of the United States nor its foreign policy. For sure, nuclear weapons haven’t gone away and there are still many challenges, but there are elements of the nuclear mission that are no longer essential and can and should be reassessed.

But the Minot investigations haven’t done that. Instead they have gone beyond fixing safety and security issues to using the incident to reaffirm status quo and reject change. Hopefully the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission and the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review can do better.

The Myth of Nuclear Modernization and the Ikea Bomb.

In the closing days of the Bush administration, we see nuclear advocates laying down markers for the debate about nuclear weapons that is expected early in Senator Obama’s presidency. In a recent speech at Carnegie and in an article in Foreign Affairs, Robert Gates, slated to stay on as Secretary of Defense, has called for developing a new nuclear bomb — the so-called Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW) (“so-called” because it is no more reliable than current warheads and it will not replace them, but it is otherwise appropriately named). General Kevin Chilton, head of Strategic Command, has made similar statements.

Those of us who are interested in working toward a world free of nuclear weapons realize that progress will involve many steps, some large, some small. One important step will be ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). Some CTBT supporters suspect that the outlines of a deal are coalescing: those who want the RRW will try to make the CTBT and the RRW a package deal, arguing that we will be able to maintain a reliable, safe nuclear deterrent without testing, as the CTBT would require, only if the weapon labs are allowed to proceed with weapon modernization. The Congressional Strategic Posture Commission interim report appears to be at least sympathetic to this view. This artificial link is based on both faulty logic and a long list of unstated and unsupportable assumptions.

The assertion that our nuclear weapons need any modernizing implies, usually implicitly, that current weapons are antiques that are not quite up to snuff. Chilton, in the article cited above, specifically links U.S. modernization to Russian and Chinese nuclear weapons. This superficially makes sense: after all, we don’t send our military out to fight with World War II vintage tanks, ships, and airplanes. Certainly the United States should be armed with the latest and best nuclear weapons; at the very least, our weapons have to be at least as modern as any possible competitors, right? The simple analogy to conventional weapons doesn’t hold because of the types of tasks assigned to nuclear weapons and some confusion about just what a “nuclear weapon” is.

A nuclear bomb is an immensely powerful explosive, whose job is to blow things up. Our tanks fight other tanks and our ships fight other ships in an intrinsically competitive interaction. If our potential enemies improve their tanks or ships, then we must improve ours. But nuclear bombs do not fight other nuclear bombs, they blow things up. They might be expected to blow up airbases, ports, or oil refineries; whatever they are expected to blow up, if they can do that, then they accomplish their mission. There are certain targets that even the most powerful nuclear bombs cannot blow up, for example, targets buried in tunnels in hard rock or targets whose location is unknown or potential targets that we do not even know exist. Whether a target can be destroyed or not depends on how big a bang the bomb makes (and how accurately it is delivered), not how “modern” it is. Even when one of the main missions of U.S. nuclear weapons was to attack and destroy the Soviet Union’s nuclear-armed missiles in their silos, we were pitting our nuclear weapons, not against Soviet nuclear weapons, but against Soviet concrete. The world’s most modern nuclear weapon would be easily destroyed if a 1945-vintage Hiroshima-style bomb blew up next to it.

A conventional analogy makes the point: The Joint Direct Attack Munition, or JDAM, is a family of highly accurate conventional bombs. The bombs are dropped from the world’s most sophisticated, multi-million dollar aircraft, including the B-2, the radar-evading stealth bomber, which costs over a billion dollars. Once in free-fall, the guidance system on the JDAM picks up signals broadcast to Earth from a multi-billion dollar constellation of satellites that make up the Global Positioning System. These satellites broadcast time signals with an accuracy of a few billionths of a second, allowing tiny computers on the JDAM to calculate the bomb’s trajectory to within a few feet. Some JDAMs are outfitted with smart fuzes. When a bomb crashes through a building, it will decelerate when it goes through the floors of the building but not in the airspace between the floors. A smart fuze will detect these decelerations and count the number of floors that it has passed through, allowing the bomb to be exploded on a particular floor. Obviously, this bomb is extremely sophisticated—a marvel of modern military technology. So what is the explosive used in the bomb? Something called tritonal, which is a mixture of TNT and powdered aluminum. TNT, the shorthand for trinitrotoluene, was discovered in 1863. Millions of pounds of it were used in the First World War. The trick of mixing TNT with powdered aluminum to increase its power is a more modern innovation, only going back to the Second World War. Clearly, this astonishingly sophisticated bomb does not depend on some modern sophisticated explosive to make it effective. The explosive is the easiest part of the job. If you can use a highly accurate guidance and fuzing system to place a few hundred pounds of TNT into, say, a communications headquarters, the fact that the bomb uses an explosive that is a century-old technology is not going to save the world’s most modern electronics.

Do not misunderstand: nuclear weapons are very complex, precision devices. And they can have specialized performance, for example, when the Nixon-era ballistic missile defense system used nuclear-armed interceptor missiles, the nuclear warheads for use in space were tailored to produce extra x-rays while those for use in the atmosphere were tailored to produce extra neutrons. A nuclear weapon intended to produce an electromagnetic pulse should be designed to maximize the second derivative of the gamma ray flux (you will just have to trust me on that one). I am simply saying that nuclear bombs do not have to be complex and their required complexity depends on the missions assigned to them, and those missions should be dramatically different now that the Cold War is over.

During the Cold War, there was a great incentive to build huge numbers of nuclear bombs. The United States was the first to put some of these bombs on missiles that were small enough to fit on submarines. In the interests of efficiency, both the United States and the Soviets put several bombs on a single missile. Both sides wanted the bombs to be able to attack missile silos and other very hard targets. The Soviets tended to build bigger missiles than the United States. The United States took the more sophisticated course of building smaller missiles and put a great deal of effort into getting nuclear weapons to be as small as possible, which required sophisticated designs and precision manufacturing.

But nuclear bombs are, in principle, pretty simple. The complexity of current weapons comes about because of the extreme performance required, not because of any necessary and intrinsic characteristic of nuclear weapons. The first bomb used in war, the one that destroyed Hiroshima, was such a simple uranium design that Manhattan Project scientists had enough confidence to use it without testing it beforehand. So the first thing to note is that any statement about the need for weapons modernization or the needed sophistication of nuclear bombs rests on a hidden assumption about what the mission for that nuclear bomb will be and how it will be delivered to its target. Since the fundamental missions of nuclear weapons—the the question of what we are asking them to do, what they are for—are now being reevaluated and remain unsettled, it is premature to say just how sophisticated nuclear weapons have to be and whether they need any “modernizing” at all.

We must also be careful not to be confused by what a nuclear weapon is. There is a part that simply goes boom. That can be simple or complex. But the bomb sits atop a missile or in a bomber or submarine that is a truly complex piece of machinery. The bomb will be guided by advanced electronic systems, perhaps including sensors. All together, this makes up a “weapon,” almost all of the components of which are non-nuclear and can be tested fully under a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, which only prohibits tests that produce a nuclear reaction. The job of the nuclear part of the weapon could in principle be very simple indeed: to explode and blow something up.

Paying attention to what is the nuclear part of the nuclear bomb is also relevant to DOE’s claim that we need a new weapon because of safety. Most of the safety attributes are in the electronics that is outside the nuclear package and can be developed and tested without nuclear testing. A few safety features are intimately connected to the nuclear package but before the RRW was even thought up DOE had plans for retroactively inserting new safety features, some quite major, into existing warheads.

I have written here about how the characteristics of the RRW imply, without debate or even apparent conscious thought, certain missions for nuclear weapons, missions that are at best of dubious relevance and most likely clearly outmoded and contrary to the security interests of the United States and the world. The most insidious part of this RRW-CTBT “deal” is the implied assertion that the new nuclear bomb we need is exactly the one that the Department of Energy (DOE) and weapon labs are trying to foist on us, along with all of its implied missions.

The United States does not need a new nuclear bomb but let’s assume for a moment that under a CTBT it does. What should that bomb be? The DOE presents many arguments. Some are based on assertion, such as the RRW will save money in the long term, even though the DOE has not done a sufficiently detailed cost study to support that statement (and historically DOE cost estimates are mind-bogglingly inaccurate). Another argument is that the labs have to physically build new bombs simply to continue to be able to build new bombs. That is, the labs need to maintain the expertise required to design and build modern, sophisticated nuclear bombs and, to do that, they need modern, sophisticated bombs to practice on. But without Cold War mission requirements, why do they need to be particularly sophisticated?

If some sort of machine, whether a computer or a toaster, has some manufacturing step that is complex and difficult, any engineer will be proud to develop some clever process to more simply and cheaply carry out that step. But the engineer will admit that that is the second best solution; the ideal solution is to redesign the machine so it still does what it is supposed to do but it does not even include that step in its manufacture. In other words, the ideal solution is not to solve the problem but to design the problem out of the system.

If maintaining design expertise is a challenge, the labs should be designing bombs, and procedures for designing future bombs, that do not require such sophisticated design expertise. If manufacturing plutonium pits is so difficult, then design bombs that do not use plutonium. (The reply will come back that we need plutonium pits because we need triggers for two-stage thermonuclear bombs with yields of tens or hundreds of kilotons of TNT explosive force. But what future missions require such huge yields? During the Cold War, the answer was attacking Soviet missile silos in a disarming first strike. If that is the future mission they have in mind, we should debate that first and only then build the new weapon to carry out that mission.) If maintaining a nuclear weapons industrial complex and the corresponding sophisticated work force is such a challenge, then DOE should design new weapons that do not require either. DOE will respond that that is precisely what they are trying to do with the RRW, but that claim is contradicted by the scale of their multi-billion dollar budget requests for the future nuclear weapons complex. Even if that is DOE’s direction, it does not go anywhere far enough.

Simple uranium bombs with high reliability and yields of twenty kilotons (or the power of the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima) or more would be easy to manufacture. We could design such a weapon, perhaps build one or two, and put the plans on the shelf in case we ever needed it. I can’t help but imagine those language-free schematic assembly instructions that come along with unassembled Ikea furniture, describing how to put a bookshelf together without special skills or complex tools. We should design the Ikea Bomb. The DOE’s arguments for a new nuclear bomb design would be a lot more convincing if DOE were eagerly trying to design themselves out of a job rather than looking at a future that has them building nuclear weapons forever.

Cautious Interim Report From Congressional Strategic Posture Commission

|

| The interim report from the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States appears to reinstate Russia as a center for U.S. nuclear thinking. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States has published an interim report that buys into many of the arguments of the Bush administration, but also appears to accept some points made by the arms control community.

Overall, however, the report comes across as a cautious and somewhat lukewarm report that doesn’t rock the boat; that appears to reinstate Russia at the center of U.S. nuclear thinking; that strongly reaffirms extended nuclear deterrence (but ignores whether that requires U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe); that accepts many of the administration’s key arguments for modernizing the nuclear weapons production complex and building modified nuclear weapons; that accepts a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (if the Stockpile Stewardship Program is revitalized); that recommends additional reductions in deployed and (if the production complex is modernized) reserve warheads; that sees nuclear disarmament as a distant future dream; and accepts that a strong and credible nuclear posture likely will be needed for the “indefinite future.”

The findings will be subject to five months of debate before the full report is published in April 2009. After that the Obama administration is expected to conduct a Nuclear Posture Review.

India’s Nuclear Forces 2008

|

| Mystery missile: widely reported as a future sea-launched ballistic missile, is the Shourya launch in November 2008 (right) a land-based mobile missile (left), a silo-based missile, or a hybrid? Images: DRDO |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A decade after India officially crossed the nuclear threshold and announced its intention to develop a Triad of nuclear forces based on land-, air-, and sea-based weapon systems, its operational force primarily consists of gravity bombs delivered by fighter jets. Short of the short-range Prithvi, longer-range Agni ballistic missiles have been hampered by technical problems limiting their full operational status [Update Feb. 2, 2009: “Defense sources” quoted by Times of India appear to confirm that the Agni missiles are not yet fully operational]. A true sea-based deterrent capability is still many years away.

Despite these constraints, indications are that India’s nuclear capabilities may evolve significantly in the next decade as Agni II and Agni III become operational, the long-delayed ATV nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine is delivered, and warhead production continues for these and other new systems.

Our latest estimate of India’s nuclear forces is available from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Nuclear Déjà Vu At Carnegie

By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

Only one week before Barack Obama is expected to win the presidential election, Defense Secretary Robert Gates made one last pitch for the Bush administration’s nuclear policy during a speech Tuesday at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

What is the opposite of visionary? Whatever, that’s the word that best describes Mr. Gates’s speech. Had it been delivered in the mid-1990s it would not have sounded out of place. The theme was that the world is the way the world is and, not only is there little to be done about changing the world, our response pretty much has to be more of the same.

Granted, Gates’s job is to implement nuclear policy not change it but, at a time when Russia is rattling its nuclear sabers, China is modernizing its forces, some regional states either have already acquired or are pursuing nuclear weapons, and yet inspired visions of a world free of nuclear weapons are entering the political mainstream, we had hoped for some new ideas. Rather than articulating ways to turn things around, Gates’ core message seemed to be to “hedge” and hunker down for the long haul. And, while his arguments are clearer than most, this speech is yet another example of faulty logic and sloppy definitions justifying unjustifiable nuclear weapons.

They Do It So We Must Do It Too

Reductions cannot go on forever, Secretary Gates argues because there is still a mission for nuclear weapons. Using language from the Clinton Administration, he says we can reduce our arsenal but we must also “hedge” against unexpected threats. He said, “Rising and resurgent powers, rogue nations pursuing nuclear weapons, proliferation of international terrorism, all demand that we preserve this hedge. There is no way to ignore efforts by rogue states such as North Korea and Iran to develop and deploy nuclear weapons or Russian or Chinese strategic modernization programs.”

While the potential threats he lists are real and must be addressed, how do nuclear weapons address these threats? And even if there were some nuclear component to our responses, the nature of those responses would be so varied that lumping these threats together muddles the issue. A nuclear response to international terrorism? Even if, for example, al Qaeda used a nuclear weapon to attack an American city, what target would we strike back at with a nuclear weapon? The implicit argument of symmetry is unsustainable. Just as we don’t respond to roadside bombs with our own roadside bombs, nor would we respond to chemical attack with chemical weapons or biological attack with biological weapons. We might respond to nuclear attack with nuclear weapons but we should not allow this to be an unstated assumption. The reason rogue nations, let’s say Iran and North Korea, are developing nuclear weapons is not to counter our nuclear weapons but as a counter to our overwhelming conventional capability. They certainly are not making the mistake of implicitly assuming symmetry.

The near universal logical sleight of hand is to make some argument for nuclear weapons, let’s say we need them because North Korea has them, and then, when people nod in agreement that we need nuclear weapons, let slip in the assumption that this implies we need the nuclear arsenal the administration wants. Not so fast. If North Korea has one, perhaps we need two, but that does not mean we need two thousand.

It helps to clarify the typically foggy nuke-think if we remove Russia and China from the picture and ask whether the United States could justify anything near its currently planned nuclear arsenal only to deter and defeat rogue states and terrorists. Of course not. And perhaps we don’t need nuclear weapons for regional scenarios at all, given our overwhelming conventional capabilities. So those odds and ends are thrown into the pot just to scare, not to explain, and not because there is any well thought out strategy for how nuclear weapons are going to stop a terrorist attack on an American city, or why it be an appropriate response to a regional state that doesn’t have the capability to threaten the survival of the United States.

Russia is a very different case: Russian long-range nuclear forces are the only things in the world today that could destroy us as a nation and society, just as we could destroy them. While relations with Russia are not friendly, no conceivable difference between the United States and Russia justifies this mutual hostage relationship. This pointless threat to our very existence persists because of a failure of imagination typified by this speech. In this case, it is the nuclear weapons that are creating the threat, not protecting us from it.

That Ole Warhead Production Fever

Whatever the supposed justification of nuclear weapons, the primary purpose of the Secretary’s speech seemed to be to promote the Reliable Replacement Warhead or RRW but again, his argument rests on hidden (and unjustified) assumptions and, at times, misstatements of fact. The basic premise is that, without testing, we are slowly but certainly losing confidence in the reliability of our nuclear arsenal. He said, “With every adjustment, we move farther away from the original design that was successfully tested when the weapons was first fielded.”

We do? The implication is that we have no other choice, what we could do in 1990 we simply can’t reproduce today, like handing a modern-day native American a hunk of flint and asking him to chip out an arrowhead. Why should this be? With a budget of billions of dollars, we can’t duplicate parts that we could make twenty years ago? We can spend billions on the National Ignition Facility to create the world’s most powerful laser but we can’t reproduce a 1980s O-ring? The problem the Secretary describes is certainly possible and something we have to be alert to but it isn’t inevitable; we can maintain weapons within design margins as long as we want and in the past—pre-RRW—that was precisely the plan. And parts of the weapon that are not the nuclear core of the bomb can be improved and modernized and tested as much as we want.

But Mr. Gates claims that we are slowly and helplessly drifting, “So the information on which we base our annual certification of the stockpile grows increasing dated and incomplete.” This implies the Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP) has failed. We believe the Secretary is wrong. Everyone we have talked to who is familiar with the enormous effort that has gone into the SSP says that our understanding of nuclear weapons today is substantially greater than it was the day after our last nuclear test. Our knowledge of the aging of nuclear warheads is increasing faster than the warheads are aging. Early uncertainties and concerns about stability, for example, of the plutonium parts of the weapon have been resolved and the parts have been shown to be stable for many decades, if not a century or more. Our computer models are dramatically and significantly more detailed and sophisticated. In fact, one weapon designer has told us that, given a fixed budget, the best investment of your next dollar would never be in a nuclear test but in more inspections, more computer simulations, more replacement of non-nuclear components, more material tests, more frequent tritium replenishment, and so forth.

|

How Many Times Does Congress Have to Say No? |

|

| Every time the Pentagon has proposed a new nuclear warhead since the end of the Cold War, Congress has refused to fund it. Now that the RRW appears to have been whacked, what will the next proposal for a new warhead look like? |

.

Aside from the question of the reliability of current warheads, Mr. Gates argues that we still need an RRW because we need to modernize. The British, French, Russians, and Chinese are modernizing so we must too, obviously. Why? Nuclear weapons are a mature technology. There is no new science in nuclear weapons. They are powerful, efficient explosives. They are intended to blow up things and they have specific missions, which typically involve blowing up specific things. If they can accomplish these missions, what is the problem? If the technology, even the weapons, is decades, even centuries old, if they work then they work. Nuclear weapons are not fighter planes or tanks or submarines, duking it out on a battlefield with the enemy’s opposite number, so our nuclear weapons should be evaluated with regard to the targets they are expected to destroy, not anyone else’s nuclear weapons. They can destroy the targets. We’re done.

The important factor is not the warhead but the delivery vehicle that is intended to bring the warhead to the target. And the reason the United States is not producing new nuclear weapons while Russia and China do is not because they can and we can’t, or they’re ahead and we’re behind, as the Secretary indicated. Rather, the United States has not been producing new nuclear weapons because it didn’t have to – the existing ones are more than adequate – and because not producing has been seen as much more important to U.S. foreign policy objectives. And if Russian and Chinese warhead production is a problem, why not propose how to influence them to change rather than advocating that we repeat their mistake?

The final argument for the RRW is that the US must maintain a nuclear production industry and the RRW is grist for that mill. But many of the RRW technologies and capabilities were developed by the very SSP that Gates now implies is failing. Six years ago – before they came up with RRW after having failed to get permission to build the Precision Low-Yield Weapon Design (PLYWD) and the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP) – the National Nuclear Security Administration assured Congress: “We believe the life extension programs authorized by the Nuclear Weapons Council for the B61, W80, and the W76 will sufficiently exercise the design, production and certification capabilities of the weapons complex” (emphasis added). That assurance was given after the Foster Panel recommended, “developing new designs of robust, alternative warheads.” Now the claim suddenly is that the life extension programs do not sufficiently exercise the weapons complex. At least get the argument straight.

What’s Around the Corner?

We would be more sympathetic to the production argument if the fundamental minimal needs of the nuclear production industry were better thought out and justified, but what we see is an effort to maintain a slimmed down version of what we have without thinking through what we need. In fact, if maintaining the production industry is the core objective, we would have expected the administration to ask for an RRW design that doesn’t need a complex production industry, one that is extremely simple, perhaps using uranium rather than plutonium, perhaps a clunky design but one sure to work that does not require any sophisticated skills that must be maintained in standby in perpetuity.

We’re concerned that in the end Congress will accept a beefed-up life extension program – they seem to have already found a name for it: Advanced Certification Program – that will relax the restrictions for what modifications can be made to existing warheads in order to incorporate as much as the RRW concept as possible and add new capabilities if necessary. Unless the next president significantly changes the nuclear guidance for what the Pentagon is required to plan for, RRW-like proposals will likely continue to make it harder to create a national consensus on the future role of nuclear weapons. And Barack Obama has not explicitly rejected the RRW, but said he does “not support a premature decision to produce the RRW” and “will not authorize the development of new nuclear weapons and related capabilities.” Enhanced life-extended warheads could fit within such a policy.

In the end, justifying the nuclear weapons production industry is shaky because the justification for the weapons themselves is shaky, resting on assertion and Cold War momentum – as Gates’ speech illustrated – more than on rigorous assessments of missions and the security of the nation.

The Secretary’s speech was a disappointing missed opportunity. We are a bit perplexed about why he gave it and gave it now. Perhaps he is putting down a marker for a debate he expects in the next administration and Congress. We welcome that debate because we believe that, with careful attention to definition and no hidden assumptions, the arguments for nuclear weapons fade away.

Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Secrecy And Confusion

|

| Sorry, can’t tell! The size of the nuclear weapons stockpile is secret, but not hard to figure out. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

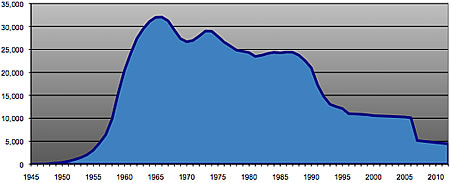

In a letter to the editor in Boston Globe, Thomas D’Agostino, the administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), writes that the United States is reducing its nuclear weapons and that, “Currently, the stockpile is the smallest it has been since the Eisenhower administration.”

That statement leaves considerable confusion about the size of the stockpile. If “since the Eisenhower administration” means counting from 1961 when the Kennedy administration took over, that would mean the stockpile today contains nearly 20,000 warheads. If it means counting from the day the Eisenhower administration took office in 1953, it would mean fewer than 1,500 warheads.

Why leave an order of magnitude of confusion about the size of the nuclear weapons stockpile?

Stockpile History

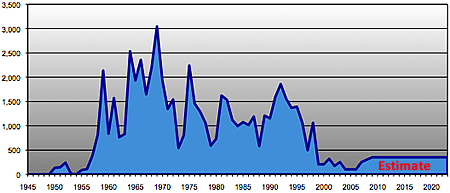

Neither number is correct. The actual stockpile size today, based on what I and my colleagues at NRDC can piece together, is approximately 5,300 warheads, or roughly the size of the stockpile in 1957 (see Figure 1). That is certainly a lot less than the 1980s, but it’s also an awful lot for the 21st century.

|

Figure 1: |

|

| The size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile has declined ever since the mid-1960s, and currently includes roughly 5,300 warheads, or approximately the size of the stockpile in 1957. When all announced reductions have been implemented in 2012, the size of the stockpile will have returned to the 1956-level of approximately 4,600 warheads. |

.

Mr. D’Agostino is, of course, in a bind because even though he and others at NNSA might agree that the stockpile size could be declassified, the Department of Defense insists it has to be kept secret. Even disclosing the number of nuclear weapons dismantled each year is prohibited, because it could help reveal the size of the nuclear stockpile. As it turns out, warhead dismantlement during the Bush administration has been the lowest since 1956 (see Figure 2).

|

Figure 2: |

|

| Even with the recent announcement of an “astounding 146 percent increase” in warhead dismantlement in 2007 and another 20 percent in 2008, the Bush administration’s dismantlement rate remains the lowest of any administration since 1956. |

.

What motivates this secrecy, other than the usual resistance to transparency in nuclear weapons matters, is preparation for a world of smaller nuclear arsenals a decade or two from now, when the United States might have reduced the number of deployed nuclear weapons to perhaps 1,000 or even less. In such a world, some fear, Russia or China might suddenly turn for the worse and secretly increase their nuclear arsenals and change the strategic balance. Knowing how many nuclear weapons the United States holds in reserve to increase the deployed force could, so the argument goes, greatly affect the U.S. ability to act and protect its allies. It’s kind of like reverse psychology: With fewer nuclear weapons it matters more what adversaries know.

A Policy For The Future

Keeping the size of the stockpile secret might have been a valid national security requirement during the Cold War, even though I don’t find the arguments very convincing. But today, nearly two decades after the Cold War ended, it is fair to ask: So what if potential adversaries know how many nuclear weapons the United States has?

If my colleagues and I can make a fairly accurate estimate, so can Russia and China. How can anyone in this day and age seriously argue that it matters that they’re 10-100 warheads off? And isn’t it better that they and our allies know the truth, instead of making their own assumptions?

More importantly, however, is that the stockpile and dismantlement numbers today are very effective instruments for showing the world that the United States is not building up its nuclear arsenal. They reassure allies and deprive adversarial hardliners the uncertainty they need to argue for nuclear modernization. Stockpile transparency, not worst-case breakout and warfighting theories, combined with an aggressive and sustained foreign policy effort to engage other nuclear weapon states, should be the priority for the next administration.

Background Information: Status of World Nuclear Forces 2008 | US Nuclear Force 2008 | Russian Nuclear Forces 2008 | Chinese Nuclear Forces 2008

State Department Arms Control Board Declares Cold War on China

After planning the war against Iraq, former Assistant Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz now heads the State Department’s International Security Advisory Board that recommends a Cold War against China.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A report from an advisory board to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice has recommended that the United States beefs up its nuclear, conventional, and space-based posture in the Pacific to counter China.

The report, which was first described in the Washington Times, portrays China’s military modernization and intentions in highly dramatic terms that appear go beyond the assessments published so far by the Defense Department and the intelligence community.

Although the Secretary of State asked for recommendations to move US-Chinese relations away from competition and conflict toward greater transparency, mutual confidence and enhanced cooperation, the board instead has produced a report that appears to recommend policies that would increase and deepen military competition and in essence constitute a small Cold War with China.

China’s “Creeping” Nuclear Doctrine

Although the report China’s Strategic Modernization – written by the International Security Advisory Board (ISAB) – deals with China’s overall military modernization, its focus is clearly on nuclear forces. What underpins China’s expansion of its offensive nuclear capabilities, the report says, is an “emerging creep toward a Chinese assured destruction capability” to create a “mutual vulnerability relationship” with the United States.

The objective is, an interpretation the authors say is supported by “numerous Chinese military statements,” for Beijing to get enough nuclear capability “to subject the United States to coercive nuclear threats to limit potential US intervention in a regional conflict” over Taiwan and oilfields in the South China Sea.

Yet “assured destruction,” to the extent that means confidence in a retaliatory capability against the United States and Russia, has been Chinese nuclear policy for decades. Increasing US and Russian nuclear capabilities, however, convinced Chinese planners that their deterrent might not survive. The current deployment of three long-range ballistic missile versions of the mobile DF-31 is supposed to restore the survivability of their strategic deterrent.

The “mutual vulnerability relationship” the authors say China is trying to create to deter the United States from defending Taiwan or limit US escalation options is a curious argument because it implies that the United States has not been vulnerable to Chinese nuclear threats in the past. In fact, US bases and allies in the Western Pacific have been vulnerable to Chinese attacks since the 1970s and the Continental United States since the early 1980s.

It is tempting to read the authors’ use of the terms “assured destruction” and “mutual vulnerability relationship” as borrowed components of “mutual assured destruction,” or MAD, the term for the nuclear relationship that existed between the United States and the Soviet Union during much of the Cold War.

But in responding to China’s nuclear modernization and policy, it is very important not to resort to Cold War-like worst-case analysis. To that end, two of the best analyzes on Chinese nuclear policy are Iain Johnston’s China’s New ‘Old Thinking:’ The Concept of Limited Deterrence, and Michael S. Chase and Evan Medeiros’ China’s Evolving Nuclear Calculus: Modernization and Doctrinal Debate. The ISAB members should read them.

Misperceptions or Just Out of Touch

The report contains several claims about Chinese nuclear forces and recommendations for counter-steps that appear out of sync with what the US intelligence community has stated and steps that the US has already taken. Some of the most noteworthy are listed below followed by my remarks:

* “By 2015, China is projected to have in excess of 100 nuclear-armed missiles…that could strike the United States.” Actually, the projection the intelligence community has made in public is for 60 ICBMs by 2010 and “about 75 to 100 warheads deployed primarily against the United States” by 2015. The ISAB report talks about targeting of the US “homeland.” If that includes Guam, then the force could reach a little above 100 by 2015 (it’s about 70 today). If “homeland” means the Continental United States, which has been the focus of the intelligence community’s projection, then a force carrying 75-100 warheads would likely include 20 DF-5As and 40-55 DF-31A. China so far is thought to have deployed fewer than 10 DF-31As.

* Some of the missiles “may be MIRVed” by 2015. What the intelligence community has said is that China has had the capability to MIRV its silo-based missiles for years but has not yet done so. MIRV on the mobile missiles, however, represents significant technical hurdles and “would be many years off,” according to the CIA, and “would probably require nuclear testing to get something that small.” Instead, if Chinese planners determine that the US missile defense system would degrade the effectiveness of the Chinese force, they “could use a DF-31 type RV for a multiple-RV payload for the CSS-4 in a few years,” the CIA stated in 2002. Even so, a multiple-RV payload is not necessarily the same as MIRV.

* China’s “substantial expansion” of its nuclear posture “includes development and deployment of…tactical nuclear arms, encompassing enhanced radiation weapons, nuclear artillery, and anti-ship missiles.” That would certainly be news if it were true, but the intelligence community hasn’t talked much about Chinese tactical nuclear weapons and what it has said has been contradictory, ranging from China might have some to “there is no evidence” that they have any. Several of China’s tests reportedly involved enhanced radiation or tactical warhead designs, but whether China is working on fielding tactical nuclear weapons has not been confirmed. China did conduct what appeared to be operational tests of tactical bombs in the past, which they might have fielded, but ISAB does not mention bombs.

* China’s modernization includes “a growing capability for Conventional Precision Strike and other anti-access/area-denial capabilities” including “submarine-launched ballistic missiles.” That China would use nuclear missiles on its future strategic submarines for “anti-access/area-denial” capabilities is news to me and would, if it were true, represent a dramatic change in Chinese nuclear policy. But I haven’t seen anything that suggests its true, and the overwhelming expectation is that China will use its SSBNs as a retaliatory strike force, if and when they manage to operationalize it.

* The US “should reaffirm its formal security guarantees to allies, including the nuclear umbrella.” The US does that regularly when it extends the security agreement with South Korea and Japan. In addition, in response to the North Korean nuclear test in October 2006, President Bush reaffirmed that “The United States will meet the full range of our deterrent and security commitments.” One week later, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice arrived in Tokyo where she emphasized the nuclear component by saying that “the United States has the will and the capability to meet the full range – and I underscore full range – of its deterrent and security commitments to Japan.”

* The US should “pursue new missile defense capabilities, including taking full advantage of space,” to counter China’s growing nuclear capability. For a State Department advisory committee to recommend using missile defenses to counter Chinese nuclear missiles is, to say the least, interesting given that the State Department has publicly stated and assured the Chinese that the missile defense system “it is not directed against China.”

* The US should “publicly reaffirm its commitment to retain a forward-based US military presence in East Asia.” The US has actually done that quite explicitly over the past seven years by shifting the majority of its aircraft carrier battle groups and nuclear attack submarines to bases in the Pacific, by beginning to forward deploy nuclear attack submarines to Guam, by sending strategic B-2 and B-52 bombers on extended deployments to Guam, and by forward deploying the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS George Washington (CVN-75) to Japan. The Pentagon describes the recent Valiant Shield exercises as “the largest Pacific exercise since the Vietnam War.”

|

Pacific Exercises Now Biggest Since Vietnam War |

|

| While ISAB recommends increasing the US military posture in the Pacific to counter China, the Pentagon says recent exercises, including the thee carrier battle group Valiant Shield 06, are now the largest since the Vietnam War.

|

.

* “For almost two decades, the United States has allowed its nuclear posture – its stockpile, infrastructure, and expertise – to deteriorate and atrophy across the board.” Although the stockpile is much smaller compared with the Cold War and industrial-scale production of new nuclear warheads has ceased, ISAB’s characterization of the US nuclear posture is way off.

Instead, during the nearly two decades the authors describe (assuming that means since 1990), the US has deployed eight new SSBNs, deployed 336 Trident II D-5 SLBM on its entire SSBN fleet, deployed 21 B-2 stealth bombers, deployed the Advanced Cruise Missile, deployed the hard-target kill W88 warhead (including in the Pacific), deployed three modified nuclear weapons (B61-10, B61-11 and W76-1), completely overhauled the Minuteman III ICBM force, deployed two new classes of nuclear-powered attack submarines capable of launching nuclear cruise missiles, deployed a modern nuclear command and control system with new satellites and command centers, modernized the Strategic War Planning System (now called ISPAN), created a “living SIOP” strategic nuclear war plan with broadened targeting against China and new strike options against regional adversaries, and built a multi-billion dollar Science Based Stockpile Stewardship Program to certify the reliability of the nuclear stockpile without nuclear testing and provide weapons designers with unprecedented knowledge about warhead aging and the skills and tools to refurbish existing warheads or build modified ones.

Where Are The Non-Military Policy Recommendations?

One of the most striking features of the report is its almost complete focus on military options and the absence of other policy components. It contains no analysis of or recommendations for how to engage China on nuclear arms control or confidence building measures to limit or influence the nuclear modernization, operations and policy. It is almost as if there must be another unknown chapter to the report.

Although the authors believe there are a number of measures the US should take to reduce the prospect for misunderstanding and the chance of miscalculation, those recommendations are few and limited to continuing existing Track II discussions, military-to-military contacts, and asking the Chinese to be more transparent.

The report concludes that China does not desire a conflict with the United States, and describes a disconnect between the political and military leadership, and a “clear paranoia and misperceptions about US intentions….” Without presenting any analysis, it concludes that the US ability to shape or change Chinese choices related to its strategic modernization may be “very constrained” and that there is no point in trying to “educate” the Chinese.

On the contrary, the report concludes that the US should “reject” Chinese arms control proposals because they will constrain US military freedom. And US arms transfer to allied countries in the region “should be an important dimension of US non-proliferation policy.” Indeed, the “most important” policy recommendation is for the United States to “demonstrate its resolve to remain militarily strong….”

And in a recommendation blatantly “imported” from the Cold War, the authors say the US should “focus” its research and development on “high technology military capabilities” that China doesn’t have to “demonstrate to Beijing that trying to get ahead of the United States is futile (much the way SDI did against the Soviet Union.”

The report essentially capitulates on non-military policy options toward China.

So What Exactly Was ISAB Asked To Do?

The advisory board was asked to come up with ideas that could “move the US-China security relationship toward greater transparency and mutual confidence, enhance cooperation, and reduce the likelihood of misunderstanding or miscalculation that can contribute to competition or conflict.” That’s a quote!

Instead, the authors appear to have produced a paper that would – if implemented – likely move the US-Chinese security relationship in the opposite direction by deepening military competition and mistrust.

Indeed, the review looks more like the kind one would expect from the Pentagon rather than the State Department, which is supposed to pursue a wider set of policies and different agenda than the military. It is all the more striking given that the charter for ISAB – which used to be called the Arms Control and Nonproliferation Advisory Board (ACNAB) – describes that the board is supposed to “advise with and make recommendations to the Secretary of State on United States arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament policies and activities.”

The Secretary’s hope has been for ISAB to provide “independent insight, advice, and innovation,” and serve as “a single advisory board, dealing with scientific, military, diplomatic, political, and public diplomacy aspects of arms control, disarmament, international security, and nonproliferation, would provide valuable independent insight and advice….”

Concluding Remarks

The militaristic focus of ISAB’s report and its lack of recommendations for arms control and broader public diplomacy to defuse rather than continuing and deepening the competitive and mistrustful relationship between the United States and China suggest that ISAB has failed to live up to its charter.

No matter what one might think of China’s military modernization, the ISAB appears instead to have drawn up a very effective plan for a Cold War with China.

Although the authors correctly state up front that the US-Chinese relationship “differs fundamentally from the US-Soviet relationship and the strategic rivalry of the Cold War,” they nonetheless land on a set of recommendations and observations that strongly resemble a China-version of the Reagan administration’s aggressive military posture against the Soviet Union.

If implemented or allowed to color US policy toward China, the policy recommendations would continue and very likely lead to a deepening of military competition and adversarial relationship between the United States and China – exactly the opposite of what the Board was asked to come up with. It is precisely reports like this that create the “deep paranoia and misperceptions about US intentions” in the Chinese military.

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice should denounce the ISAB report to make it clear that the core of US policy toward China is not containment and Cold War posturing. And one of the first acts of the next Secretary should be to appoint a new advisory board that can – and will – develop recommendations that can “move the US-China security relationship toward greater transparency and mutual confidence, enhance cooperation, and reduce the likelihood of misunderstanding or miscalculation that can contribute to competition or conflict.” Mission not accomplished!

Background Information: ISAB Report: China’s Strategic Modernization | Chinese Nuclear Forces 2008 | US Nuclear Forces 2008 | FAS/NRDC Report: Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning

Nuclear Policy Paper Embraces Clinton Era “Lead and Hedge” Strategy

By Hans M. Kristensen

The new nuclear policy paper National Security and Nuclear Weapons in the 21st Century published quietly Tuesday by the Defense and Energy Departments embraces the “lead and hedge” strategy of the first Clinton administration for how US nuclear forces and policy should evolve in the future.

Yet the “leading” is hard to find in the new paper, which seems focused on hedging.

Instead of offering different alternative options for US nuclear policy, the paper comes across as a Cold War-like threat-based analysis that draws a line in the sand against congressional calls for significant changes to US nuclear policy.

Strong Nuclear Reaffirmation

The paper presents a strong reaffirmation of an “essential and enduring” importance of nuclear weapons to US national security. Russia, China and regional “states of concern” – even terrorists and non-state actors – are listed as justifications for hedging with a nuclear arsenal “second to none” with new warheads that can adapt to changing needs.

Even within the New Triad – a concept presented by the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review as a way to decrease the role of nuclear weapons and increasing the role of conventional weapons and missile defense – the new paper states that nuclear weapons “underpin in a fundamental way these new capabilities.”