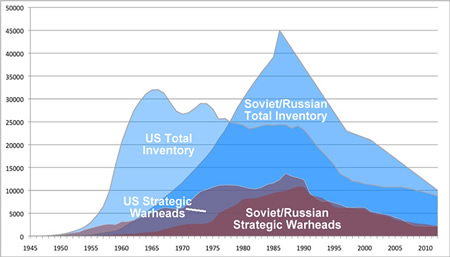

US-Russia Summit Nuclear Weapons Information

|

By Hans M. Kristensen

Can they do it? Expectations are high for the July Moscow Summit to produce an agreement to extent the START Treaty and commit to additional nuclear weapons reductions in the future. The following provides quick access to information about nuclear weapons numbers:

Overview of World Nuclear Forces

Global Nuclear Stockpiles, 1945-2006

US and Russian Total Nuclear Arsenals:

– Russia

– Briefing slides on history of US and Russian nuclear arsenals

US and Russian Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons:

– US Nuclear weapons in Europe

– History of US nuclear weapons in South Korea

– Russian Tactical Nuclear Weapons

Other Nuclear Weapon States (Most Recent Overviews):

– France, China, United Kingdom, India, Pakistan, Israel, North Korea

Japan, TLAM/N, and Extended Deterrence

|

| PACOM Commander Admiral Keating is “unaware” of the Japanese interest in the nuclear Tomahawk cruise missile reported by the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

Admiral Timothy J. Keating, who is Commander of U.S. Pacific Command, said Monday that he is “unaware of specific Japanese interests in the” nuclear-armed Tomahawk Land-Attack Missile.

That’s interesting because the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission recently pointed explicitly to such a Japanese interest in the role that the missile – known as the TLAM/N – provides in extending a U.S. nuclear umbrella over Japan to deter nuclear attacks against it from China and other potential adversaries in the region.

We would expect the commander of Pacific forces to be in close contact with the highest levels of the Japanese government and military. Shouldn’t he be aware of a specific Japanese interest in specific weapons for the U.S. nuclear umbrella? So statements to the contrary in the recent Congressional Commission report seem odd and worth investigating.

The Claims

The final report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States of America makes several claims about Japan and the TLAM/N, primarily that:

“extended deterrence [in Asia] relies heavily on the deployment of nuclear cruise missiles on some Los Angeles class attack submarines—the Tomahawk Land Attack Missile/Nuclear (TLAM/N). This capability will be retired in 2013 unless steps are taken to maintain it. U.S. allies in Asia are not integrated in the same way into nuclear planning and have not been asked to make commitments to delivery systems. In our work as a Commission it has become clear to us that some U.S. allies in Asia would be very concerned by TLAM/N retirement.”

Indeed, the report states that the TLAM/N is “primarily relevant to extended deterrence to allies in Asia.”

According to several sources, Japanese government officials provided the Commission with a written list of requirements for the nuclear umbrella. Neither the list not the wording of the Japanese statements are included in the report, which provides the following statement without mentioning Japan by name: “One particularly important ally has argued to the Commission privately that the credibility of the U.S. extended deterrent depends on its specific capabilities to hold a wide variety of targets at risk, and to deploy forces in a way that is either visible or stealthy, as circumstances may demand.”

The U.S. Nuclear Posture in the Pacific

The United States has approximately 300 nuclear-armed TLAM/N, of which about half are stored in igloos at Strategic Weapons Facility Pacific (SWFPAC) near Bangor, Washington (the other half or so are at Strategic Weapons Facility Atlantic (SWFLANT) at Kings Bay, Georgia).

Only about 100 of the TLAM/N warheads are active with limited-life components installed, but none of the missiles are deployed on attack submarines under normal circumstances. Less than a dozen of the 53 U.S. attack submarines are capable of firing the TLAM/N, and although the boats and crews periodically undergo training and inspections to certify them for the mission, they are de-certified again to focus on real-world non-nuclear missions. It would take several months to ready the missiles, recertify the submarines, and deploy the missiles at sea.

The approximately 150 TLAM/N at SWFPAC represent but a fraction of the U.S. nuclear posture in the Pacific, which includes well over 1,000 W76 and W88 warheads for Trident II sea-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) on eight Ohio-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) patrolling the Pacific Ocean. Five-six of the eight Pacific SSBNs with an estimated 480-570 warheads onboard are deployed at any given time. Hundreds of additional warheads stored at SWFPAC are available for increasing loading on the SSBNs to an estimated 1,300 warheads if necessary.

| USS Henry M. Jackson (SSBN-730) in Hawaii |

|

| The nuclear umbrella over Japan is supported by a huge nuclear arsenal in the Pacific region, including SSBNs such as this one that continuously patrol the Pacific and occasionally make their presence known by visiting Hawaii and other Pacific ports. |

In addition to this sea-based force, a portion of the 500 warheads on 450 Minuteman III Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) also cover strike options in the PACOM region, as do B-2 and B-52H bombers with nuclear bombs and cruise missiles. Moreover, F-15Es of the 4th Fighter Wing at Seymour-Johnson Air Force Base in North Carolina have contingency a nuclear strike mission in the Pacific (and elsewhere).

In addition to these nuclear forces, the U.S. Navy is moving 60 percent of its carrier battle groups and nuclear attack submarines into the Pacific. One of these battle groups is even homeported in Japan. Naval exercises in the Pacific are now bigger than even during the Cold War. The Air Force is rotating long-range bomber squadrons to Guam more or less continuously.

Why, given these extensive U.S. forces earmarked for the Pacific region, anyone in Tokyo, Washington, Beijing or Pyongyang would doubt the U.S. capability to project a nuclear umbrella over Japan – or see the TLAM/N as essential – is puzzling. While not all of these warheads are necessarily intended for the defense of Japan per ce, just how many are is probably irrelevant for the purpose of deterrence and assurance. Even if the posture were cut by fifty percent, more than three times the entire Chinese nuclear stockpile would still remain, enough to deter any real-world adversary – to the extent anything can.

The Nuclear Lobby: Articulating a Persuasive Nuclear Mission

So why do we suddenly hear all this talk of Japan being deeply worried about the future of a few hundred TLAM/Ns? After all, nearly all U.S. presidents since Kennedy have called for the elimination of nuclear weapons. As a nuclear target in World War II Japan has always called for the elimination of nuclear weapons, perhaps a little disingenuous given its reliance on the U.S. nuclear umbrella and Japanese officials privately saying that elimination probably wouldn’t happen anyway. Yet the growing international momentum across the traditional political trench-lines for moving convincingly down the nuclear ladder toward zero appears to have caught some in the Japanese government by surprise. Now they suddenly have to think about what it means to move toward zero, and change is always hard.

Another reason appears to be that the end of the Cold War and a growing momentum toward a nuclear free world – even supported by even the presidents of the United States and Russia – have left defense hawks and nuclear proponents on the defensive. Chinese modernization, rogue states, and terrorism haven’t quite been able to sustain the nuclear vigor after the demise of the Soviet threat. In that void, obscure and confidential statements from Japanese and other allied officials about extended deterrence have suddenly become essential tools in an attempt to articulate a persuasive – even positive – enduring role for nuclear weapons. The essence of the message is: nuclear weapons prevent proliferation of nuclear weapons and without them more will come.

It’s tempting to see a collusion. In December 2006, the Defense Science Board (DSB) task force on nuclear capabilities warned that “entrenched views” of arms control advocates had robbed the United States of its “national consensus” on the role of nuclear weapons. The White House and senior leaders had to “engage more directly to articulate the persuasive case” for how modern nuclear weapons serve U.S. national security policy.

After clumsy attempts to get Congressional approval for Complex 2030 and the Reliable Replacement Program backfired and instead caused Congress to ask for a review of nuclear policy, a four-page joint DOD-DOE-State Department statement in July 2007 attempted to articulate one but fell short. And although the loss of control of six nuclear warheads at Minot Air Force Base the following month initially put the nuclear enterprise in doubt, the incident has since become an important vehicle for arguing the case urged by the DSB. During the past 12 months, a series of reports by government agencies and defense institutes have emerged that echo the same basic themes of an enduring role for nuclear weapons, need for modernizations, and continued nuclear threats. The extended deterrence mission underpins these themes:

* September 2008: Schlesinger Task Force Phase I report on the Air Force’s nuclear mission

* September 2008: joint DOD-DOE report on nuclear weapons in the 21st century

* October 2008: Air Force Task Force report on reinvigorating the Air Force nuclear enterprise

* January 2009: Schlesinger Task Force Phase II report on the DOD nuclear mission

* May 2009: Congressional Commission report on the strategic posture of the United States.

These reports, authored by agencies and individuals that are or have been deeply involved in the nuclear business (and many of which “ran the Cold War”), argue for a reaffirmation – even strengthening – of extended deterrence as a “good” and enduring mission for nuclear weapons to prevent proliferation in the 21st Century. They argue that since the U.S. nuclear umbrella is extended to some 30 countries (one report even says 30-plus countries; I can only count 30) it prevents them from acquiring nuclear weapons themselves. Yet for the overwhelming majority of those countries, the function of the extended deterrent is not about nonproliferation but about the ultimate security guarantee. The number of those countries that could potentially be expected to develop nuclear weapons if the U.S. nuclear umbrella disappeared is very small, perhaps a couple, and whether they would actually do so depends on a wide spectrum of factors, most of which have nothing to do with nuclear weapons. Yet the reports paint the role of nuclear weapons as alpha omega.

| James Schlesinger |

|

| James Schlesinger, who like many other key contributors to recent nuclear studies helped shape Cold War nuclear planning, has been granted a powerful role in articulating post-Cold War policy. |

The September 2008 Schlesinger report describes a “daily” contribution of nuclear weapons, a theme that is echoed by many of the other reports and has been used in testimony before Congress: “Though our consistent goal has been to avoid actual weapons use, the nuclear deterrent is ‘used’ every day by assuring friends and allies, dissuading opponents from seeking peer capabilities to the United States, deterring attacks on the United States and its allies from potential adversaries, and providing the potential to defeat adversaries if deterrence fails.”

One has to be very careful about such nuclear dogma because it quickly can balloon the perceived contribution, mission, and requirements beyond reality. Since the end of the Cold War, which country can we actually say has been deterred by nuclear weapons from attacking anyone, which country has been dissuaded by nuclear weapons from pursuing advanced military capabilities, and which allied or friendly country has been assured by nuclear weapons from pursuing nuclear weapons? This list is very small and the evidence dubious and circumstantial even in the best cases.

Yet the combined effect of these studies and the lobbying that accompany them appears to be setting the tone, at least at the outset, for the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review. Extended deterrence has risen to the top of the agenda and has been assigned to one of only four working groups in the review (International Dimensions), instead of incorporating analysis of that mission into the Policy and Strategy working group like the other missions.

Concluding Remarks

It is impossible to say to what extent Admiral Keating was aware of the public relations battle that is raging on the nuclear extended deterrence front when he gave his answer at the Atlantic Council. I think he was. He certainly looked like he was choosing his words very carefully.

Nuclear advocates and defense hawks appear to be milking the extended deterrence mission for all it’s worth to secure funding for pet projects such as the TLAM/N, a replacement missile, and a nuclear role for the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, capabilities that are not needed. Yet the Congressional Commission report concludes that assuring allies that the U.S. extended deterrent remains credible and effective “may require that the United States retain numbers or types of nuclear capabilities that it might not deem necessary if it were concerned only with its own defense.” Indeed, the Commission said, echoing the January 2009 Schlesinger report, the extended deterrence mission has “design implications for the posture” and nuclear weapons “modernization is essential to the non-proliferation benefits derived from the extended deterrent”.

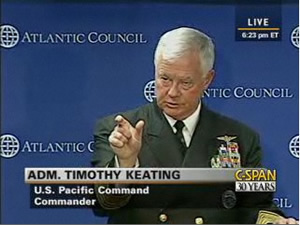

| Admiral Timothy J. Keating |

|

| The head of PACOM, Admiral Timothy Keating, says he is “unaware of specific Japanese interest in that particular system” (TLAM/N) described recently by the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission. |

The issue is not whether there should be an extended deterrent or not but what characteristics it needs to have and for what purpose. Nuclear cruise missiles and dual-capable fighter aircraft are characteristics of what nuclear extended deterrence looked like the Cold War, but they might not be necessary or even appropriate today. Long-range systems might be sufficient. Whatever Japanese officials have said about the composition and role of the U.S. nuclear umbrella, there is probably more to the story than meets the eye. Even if some Japanese express a unique value in the TLAM/N – the U.S. military certainly does not share that view – what they say might tell us more about what deterrence literature and Cold War history they have read and which U.S. officials they meet with.

To that end I find it curious that the Japanese government apparently has not brought its alleged interest in the TLAM/N to the attention of PACOM even though that command works with Japanese officials on a daily basis to provide the military capabilities that make up the U.S. security guarantee to Japan. And it is not because PACOM is not aware of their interest in the nuclear umbrella. In the words of Admiral Keating, responding to a question from Miles Pompers from the Center for Nonproliferation Studies:

“As I move around the [PACOM Area of Responsibility]…sooner or later many of the folks with whom we have discussions will get around to asking ‘is your nuclear deterrent umbrella going to continue to extend over’ fill-in-the-blank country? So our capabilities in this area are not taken for granted all throughout our area of responsibility. Everywhere I go, sooner or later – not just in mil-to-mil – the conversation comes up.

I am unaware of specific Japanese interest in that particular system [TLAM/N] you describe. I am, as I said, aware of Japanese interest in the nuclear umbrella.”

It is important for the quality and credibility of the nuclear extended deterrent debate here in the United States and elsewhere to see what the Japanese officials have said and provided, what status and function the officials have within the Japanese government (the Commission report only identifies four individuals from the Japanese embassy in Washington, D.C.), and exactly what they were asked and by whom. The reason is, as all officials know, that questions asked and answers given are always influenced by such factors. It would serve neither the United States nor its allies if the future U.S. nuclear extended deterrence policy and capabilities were to fall victim to bias and special interests.

No U.S. Nukes in South Korea

|

|

North Korea mistakenly believes there are U.S. nuclear weapons in South Korea. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The North Korean newspaper Rodong Sinmun reportedly has issued a statement saying the U.S. has 1,000 nuclear weapons in South Korea. In this regional war of rhetoric it is important to at least get one fact right: The United States does not have nuclear weapons in South Korea. It used to – at some point close to 1,000 – but the last were withdrawn in 1991.

The only nuclear weapons the United States has in the Pacific today are the hundreds of warheads deployed on Trident II D5 sea-launched ballistic missiles on board eight Ohio-class nuclear-powered submarines patrolling in the Pacific Ocean. Some of them may be earmarked for potential use against targets in North Korea. Other weapons for bombers could be moved into the region if necessary, but they’re not today.

The North Korean obsession with the U.S. nuclear “threat” might be seen as confirmation that the nuclear deterrent works and hopefully will deter North Korea from attacking anyone. But the flip side of the coin is to what extent the U.S. nuclear posture in the Pacific – past and present – helps feed the North Korean nuclear rhetoric and perhaps even ambitions.

Additional information: A history of U.S. nuclear weapons deployment to and withdrawal from South Korea.

New Air Force Intelligence Report Available

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Air Force Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has published an update to its Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat. The document, which I obtained from NASIC, is sobering reading.

The latest update continues the previous user-friendly format and describes a number of important assessments and new developments in ballistic and cruise missiles of many of the world’s major military powers.

The report also helps dispel many web-rumors that have circulated about Chinese, Russian, Indian and Pakistani nuclear forces.

In this blog I’ll focus on the nuclear weapon states, particularly China.

Chinese Nuclear Forces

As the DF-3A retirement continues (there are now only 5-10 launchers left of close to 100 in the 1980s), the liquid-fuel missile is being replaced by a family of solid-fuel DF-21 variants. The NASIC identifies four, including two nuclear versions (Mod 1 and Mod 2), one conventional version, and an anti-ship version that unlike the others is not yet deployed.

Thankfully, the report dispels widespread speculation by web sites, news media, and even Jane’s after images began circulating on the Internet, that a DF-25 had been deployed, some even said with three nuclear warheads. But it was, as I predicted last year and NASIC now confirms, in fact a DF-21.

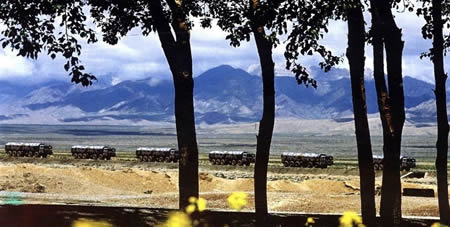

|

DF-21 Road-Mobile Launchers |

|

| A column of DF-21s on the road in what could be the Delingha deployment are in Qinghai Province. Several of the vehicles have identical camouflage patterns, raising suspicion that the image has been manipulated. Four DF-21 versions exist, two nuclear, one conventional, and one anti-ship version. Image: Web |

.

The report also reaffirms that the first of the DF-31s and DF-31As “have been deployed to units within the Second Artillery Corps,” and NASIC estimates that “less than 15” are deployed, up from the “less than 10” estimate in the Pentagon’s March 2009 report (which actually used 2008 data).

The NASIC report states that neither of China’s two types submarine-launched ballistic missiles is operational. This suggests that the multi-year overhaul of the JL-1 equipped Xia SSBN, which was completed last year, was not successful. The successor missile JL-2 for the new Jin-class SSBNs has not reached operational status either. NASIC gives the JL-2 the U.S. designation CSS-NX-14, not a numerical follow-on to the JL-1, which is listed as CSS-NX-3. The “14” could be a typo, but it appears several places in the report. The JL-2 is shown to have roughly the same dimensions as the Russian SS-N-32 SLBM.

NASIC lists single warheads on all of the Chinese missiles, not multiple warheads as speculated by many. “China could develop MIRV payloads for some of its ICBMs,” the report states. Yet it also predicts that, “Future ICBMs probably will include some with multiple independently-targetable reentry vehicles.” Whether that prediction – which appears to hint that China has more ICBMs under development – comes true remains to be seen, and the U.S. intelligence community has stated for years that one development that could trigger it is a U.S. ballistic missile defense system.

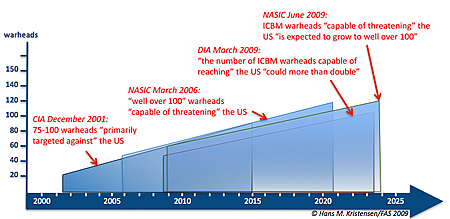

The report echoes recent statements from other branches of the U.S. intelligence community that the number of warheads on Chinese ICBM capable of reaching the United States could expand to “well over 100 in the next 15 years.” Unfortunately, “well over 100” can mean anything so it is hard to compare this NASIC’s projection with the CIA projection from 2001 of 75-100 warheads “primarily targeted against the United States” by 2015. That projection only included DF-5A and DF-31A capable of targeting all of the United States, with the high number requiring multiple warheads on DF-5A. But the timeline for the anticipated increase has slipped considerably from 2015 to 2024.

.

Moreover, ICBMs “primarily targeted against the United States” is a smaller group of missiles than those “capable of reaching the United States,” which currently includes about 60 DF-4, DF-5A, DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs with as many warheads. For this group to grow to “well over 100 warheads” suggests that NASIC anticipates that China will deploy at least 60-70 DF-31, DF-31A and JL-2 missiles by 2024 (the DF-4 will probably have been retired by then). Assuming that includes 36 JL-2s on three Jin-class SSBNs, an additional 20-30 total DF-31s and DF-31As would have to be deployed to reach 120 ICBM warheads. If five SSBNs were deployed, then only 10 additional land-based ICBMs would be required, or 30 if the 20 DF-5As were retired.

The DH-10 land-attack cruise missile is listed as “conventional or nuclear,” the same designation used for the nuclear and conventional Russian AS-4. But unlike the 2009 DOD report on Chinese military forces, which lists 150-350 DH-10s deployed with 40-50 launchers, NASIC lists the operational status as “undetermined.”

Russian Nuclear Forces

NASIC states that “Russia retains about 2,000 warheads on ICBMs,” which is far too many for the land-based ICBM force and so probably includes SLBMs as well. The ICBM force will continue to decrease due to arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints. Even so, “Russia will probably retain the largest ICBM force outside the United States,” and “most of these missiles are maintained on alert, capable of being launched within minutes of receiving a launch order,” according to NASIC.

|

|

The multiple-warhead RS-24 ICBM is, according to NASIC, not a new missile but a modified version of the SS-27 (Topol-M). |

The NASIC report formally designates the “multiple” warhead RS-24 ICBM to be a modification of the SS-27 Mod 1. This has some significance because Russia under START is not allowed to increase the warhead loading on missiles declared under the treaty, but in anticipation of the treaty expiring in December 2009 apparently has been working on doing so anyway. The RS-24, which will exist in both silo and road-mobile versions, is not yet deployed but Russian military officials have said this will happen in December.

On the submarine force the modified SS-N-23 known as Sineva is listed as carrying the same number of warheads (4) as the original version, far less than the “up to 10” listed by NASIC in 2006 and by Russian news media. The range is listed as the usual 8,000+ km even though the Russian Navy claimed in October 2008 to have test-flown the missile to 11,547 km. NASIC also continues to list two remaining Typhoon-class SSBNs as capable of carrying the SS-N-20, even though the missile is reported to have been withdrawn from service. I suspect this is because the report uses START-counted missile tubes. A third Typhoon SSBN has been converted as a test platform for the SS-N-32/Bulava-30, and NASIC lists this submarine with 20 tubes for the new missile.

Interestingly, the kh-102 cruise missile, a replacement for the AS-15 long rumored to be under development, is not listed by NASIC.

Indian Nuclear Forces

Even though Indian news media reports and private/corporate institutes have reported for years that Agni I and Agni II were deployed, the NASIC report shows that operational deployment of the road-mobile Agni I SRBM has only recently begun, with “fewer than 25” missile launchers deployed. NASIC seems to back our assessment from last year that the Agni II at that time was not yet fully operational, by listing “fewer than 10” launchers deployed.

Two short-range sea-based ballistic missiles are under development: Dhanush and Sagarika. Neither is operational yet, and NASIC safely estimates that the Sagarika will become operational sometime after 2010.

Despite Indian news media reports of development of a nuclear-capable cruise missile, no mentioning of such a weapon system is made by NASIC.

Pakistani Nuclear Forces

There are fewer than 50 launchers for the road-mobile Ghaznavi and Shaheen I SRBMs listed in the NASIC report, and the 2,000+ km Shaheen II MRBM is not yet operational but may be soon. Pakistan also appears to have two nuclear-capable cruise missiles under development: the ground-launched Babur and the air-launched Ra’ad.

Other Nuclear Weapon States

Although “friendly” nuclear weapon states are not included because they are not a “threat” to the United States, the report’s section on cruise missiles is nonetheless interesting because it – unlike the ballistic missile sections – describes weapon systems of “friendly” nuclear weapon states such as France and Israel. Yet nuclear systems, such as the French ASMP-A, are excluded. Israeli submarine-based cruise missiles, which have been rumored to have nuclear capability (I’m not convinced), are not included either.

Curiously, even after two nuclear tests and the intelligence community stating for more than a decade that North Korea has nuclear weapons, the NASIC report does not list any of North Korea’s weapons as “nuclear” or “conventional or nuclear.” That is, I think, interesting.

Background Information: 2009 NASIC report | Previous NASIC reports

A Chinese Seabased Nuclear Deterrent?

|

|

An article in USNI, which carries this photo of USS Hartford (SSN-768) damaged in a recent collision, discusses China’s ballistic missile submarines. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The magazine U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings has an interesting article about China’s nuclear ballistic missile submarines written by Andrew S. Erickson and Michael Chase from the U.S. Naval War College. And I’m not just saying that because they reference several of my publications about China, but because they provide an interesting discussion of the possible motivations for China’s emerging sea-based nuclear force.

I, for one, have always wondered why, if China’s current strategic modernization is intended to reduce the vulnerability of its long-range nuclear deterrent, would China want to cluster a significant portion of its missiles on a few submarines and send then out to sea where U.S. attack submarines can hunt them down?

In theory a sea-based nuclear deterrent is invulnerable because it can hide. But given that the U.S. Navy’s Maritime Strategy in the 1980s was explicitly designed to find and sink Soviet ballistic missile submarines before they could launch their missiles, how secure will China’s sea-based nuclear deterrent actually be? Or how would China react in a crisis, if one of the submarines went missing due to an accident?

.

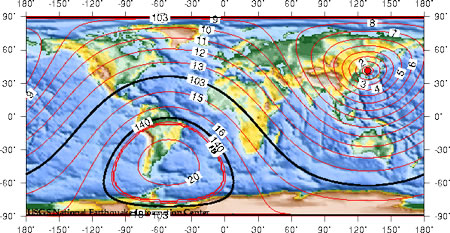

North Korea’s Nuclear Test: Another Fizzle?

|

| The North Korean nuclear test on May 25, 2009, was “heard” loud and clear around the world despite its apparent limited size. Detection of small, clandestine nuclear tests seems to work. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Korean Central News Agency reportedly has announced that North Korea “successfully conducted one more underground nuclear test on May 25 as part of measures to bolster its nuclear deterrent for self-defense.” Several news media reported that the Russian Ministry of Defense estimating the test had a yield of approximately 10 to 20 kilotons.

Yet the preliminary seismic data published by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) shows that the test had a seismic magnitude of 4.7, only slightly more powerful than the 4.3 of the 2006 test.

Was it another fizzle? We’ll have to wait for more analysis of the seismic data, but so far the early news media reports about a “Hiroshima-size” nuclear explosion seem to be overblown.

Update: CTBTO’s initial findings.

.

Congressional Commission and Nuclear “Requirements”

The Congressional Commission on the strategic posture report released yesterday is what the Air Force calls a “target rich environment.” There is a lot to shoot at. This essay follows up on the post that Hans Kristensen and I published yesterday. I want to continue the theme I discussed yesterday that the recommendations of the report are based on assumptions about nuclear weapons characteristics, assumptions that are implicit, unexamined, and unsupportable.

For example, “Although nuclear weapons have existed for over sixty years, weapons science was largely an empirical science for much of that period. Nuclear weapons are exceptionally complex, involving temperatures as high as the sun and times measured in nanoseconds. Understanding these weapons from first principles requires a broad, diverse and deep set of scientific skills, along with complex experimental tools and some of the fastest and most powerful computers in the world.”

But didn’t we build nuclear weapons in 1945 while armed only with slide rules? The above statement about the science of nuclear weapons is partially true about our current nuclear weapons but that is because our current weapons are high performance, two-stage thermonuclear bombs with yields of up to fifty times greater than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. As I have written elsewhere, these powerful bombs are needed to conduct first strike attacks against Soviet, and now Russian, hardened silos containing nuclear-armed missiles. The reason they must be of such sophisticated design is to make them small and light so many of them can fit atop one missile, to increase American strike power efficiently. The requirement for knowledge of plutonium behavior comes about because plutonium is a far better trigger than uranium for multi-hundred kiloton weapons. These were all important nuclear weapons requirements during the Cold War.

Do these “requirements” persist today? In fact there is no new physics needed to understand nuclear weapons adequately; they are, in principle, well understood, the challenges are technical, not scientific, and there is little to no technical challenge left for American and other advanced nuclear weapon states in just getting a bomb to explode and we could design bombs that do not require a complex supporting infrastructure. There is, however, a challenge in getting a dozen warheads, each with several hundred kilotons of yield, on one missile and that was important at a time when the United States was planning a nation-crushing attack on the Soviet Union. The stated need to maintain expertise in the labs rests, then, on an implicit endorsement of a nuclear mission that many of us think ought to be explicitly rejected. This occurs at several points in the report; the commission is so comfortable with the nuclear status quo that they seem unaware of fundamental questions that are being widely discussed today about the future of nuclear weapons.

The report repeatedly makes implicit assumptions about nuclear weapon performance characteristics that depend on nuclear missions while never saying anything specific about the missions themselves. For example, “So long as the nation continues to require a nuclear deterrent, these weapons should meet the highest standards of safety, security, and reliability.” This is an open-ended requirement. We are not given the faintest clue about how we will know when we will be done. When will our nuclear weapons be safe, secure, and reliable enough? The political answer is that they will never be safe enough, the weapon labs will make nuclear weapons as safe as they can with the biggest budget they can convince the Congress to send to them and if you send them more money the weapons will be more safe. More safety is always better, right? Apparently not, because we could dramatically increase the safely of nuclear weapons by storing them disassembled. But since this would not allow them to be used quickly (in another place the report advocates ICBMs because they are “immediately responsive”) it is too far outside the box to be considered by the Commission. The Commission’s constraints on considering what is available to enhance safety implies, without examination, certain mission requirements and it is precisely these mission requirements that the Commission ought to have been focusing on. Instead, they talk about lab budgets.

An amusing comparison is the discussion of how the labs ought to be relieved of some of their safety and security burden. While nuclear weapons should meet the “highest standards” of safety and security, the Commission later writes,

“A significant new cost driver is security. Costs to protect nuclear weapons and material have dramatically increased over the past few years. Today, security costs at NNSA sites consume one out of every five dollars appropriated for the weapons program or approximately $1 billion per year. Some increase was inevitable in the aftermath of the attacks of September 11, 2001. But in the view of the Commission, some of the increase is not warranted. Both the Congress and the Department of Energy have been reluctant to take actions that might be interpreted as a lessening of security. As a result, the security program has become unbalanced, with few incentives for reducing costs and a tendency to apply standard procedures even when illogical.”

And later, the report states,

“Costs for security are inordinately high in part because of the incentive structure. There are no incentives to do more than simply comply withexisting standards and, instead, to use good judgment in the service of innovation. Conditional probability metrics are not being used as the basis for defining the necessary security protection at the sites.”

Nor are “conditional probability metrics” being used to determine the required safety and security requirements for the warheads themselves.

Some others have written on the report. A brief piece is in Wired and Kingston Reif at the Center for Arms Control and Non-proliferation did a good analysis.

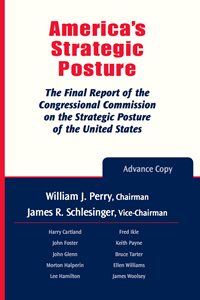

Strategic Failure: Congressional Strategic Posture Commission Report

|

| The final report from the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission seems focused on hedging rather than leading. |

By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

The Congressional Strategic Posture Commission report published today is definitely not the place that the President or the nation should look for new ideas on how to reduce the role of nuclear weapons and lead the world toward a world free of nuclear weapons.

Even for a compromise document written by a diverse group, it is a work of deeply disappointing failure of imagination. The recommendations can be summarized as: the nuclear world should stay pretty much the way it is but at slightly lower force levels, incrementalism is the most we can hope for, and even that should be approached very cautiously.

The report comes close to dismissing the President’s vision of a world free of nuclear weapons – and the enthusiastic support it has generated worldwide – as a utopian dream: “The conditions that might make the elimination of nuclear weapons possible are not present today and establishing such conditions would require a fundamental transformation of the world political order.” The United States should retain a viable nuclear deterrence “indefinitely.” The Commission surrenders to the nuclear problems of the world rather than recommending a proactive way forward out of the mess.

Of course, the Commission is not opposed to nuclear reductions per se and supports them under certain conditions, but it recommends that the approach “balances deterrence, arms control, and non-proliferation. Singular emphasis on one or another element,” the report says, apparently hinting at disarmament, “would reduce the nuclear security of the United States and its allies.”

If the Commission’s report is any preview of the Pentagon’s Nuclear Posture Review, we should expect minimal changes in nuclear forces, structure, or mission. The report recommends a nuclear policy of “leading and hedging” but seems to be focused on hedging.

The Nuclear Mission and Deterrence

While President Obama believes the United States should “put an end to Cold War thinking” and “reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, and urge others to do the same,” the Commission offers little support for this approach or analysis of what it would mean.

Indeed, while the report concludes that, “…as long as other nations have nuclear weapons, the U.S. must continue to safeguard its security by maintaining an appropriately effective nuclear deterrent force,” the Commission fails to ask fundamental questions about what nuclear weapons are for and what their character should be. This is probably because there was no consensus on these matters, but better to ask the question and admit they have no answer than to simply state over and over again that nuclear weapons are for “deterrence.” Since some will believe that “appropriately effective” is two thousand nuclear weapons and others think it will be twenty, what does the statement mean?

But it is also an assertion that should be, but is not, challenged. Does this really mean that if North Korea has one nuclear bomb, intended to counter our overwhelming conventional capability, we need to have nuclear weapons to counter it? That may be true but it is certainly not clear to us and should not be asserted as though it needs no explanation. Elsewhere the report says the United States faces decisions about how to reduce “nuclear weapons to the absolute minimum.” Again, two honest people could agree on this goal and differ by a factor of a hundred or a thousand on what an “absolute minimum” is. When the United States had 32,000 nuclear weapons, that was also considered the “absolute minimum” needed for national security.

Without examination of the mission of nuclear weapons, how can we say what their characteristics should be? Even if nuclear weapons are for deterrence, how do they deter? What are their targets? How should those targets be attacked? If we do not answer, or even ask, those questions, how can we say that we need high levels of reliability? How can we say we need land-based missiles that can be launched on a moment’s notice? How can we say we need a vast nuclear weapons complex to design complex two-stage thermonuclear weapons with hundreds of kilotons of yield? There are other examples as well, about reliability, safety, and so on, that presume missions for nuclear weapons that simply should not be presumed.

The Commission acknowledges that it is difficult to replicate the “relatively simple” deterrence calculus of the Cold War, determined by the damage inflicted, in today’s much more complex and fluid security environment. Even so, the report states, the United States still “needs a spectrum of nuclear and non-nuclear force employment options and flexibility in planning along with the traditional requirements for forces that are sufficiently lethal and certain of their result to threaten an appropriate array of targets credibly.” The justification for this sweeping conclusion about capabilities is that “the security environment has grown more complex and fluid.”

As with so many discussions of nuclear weapons, the use of the term “deterrence” in particular is confused and the logic self-referencial. Throughout the report, in too many places to cite, are repeated explicit declarations that nuclear weapons are for deterrence. The report frequently makes the mistake of talking about nuclear weapons and deterrence and then slipping into the error of assuming that deterrence must be nuclear deterrence, or the report makes true statements about deterrence but then implies that the deterrence must be effected with nuclear weapons. It repeatedly refers to our nuclear forces as our “deterrent” or our “deterrent forces” as though they were the same thing. Nuclear weapon designers are maintaining their “deterrent skills.”

In describing the role of deterrence, the Commission glosses over many important developments that have shaped U.S. nuclear policy, strategy, and doctrine over the years. “In a basic sense, the principal function of nuclear weapons has not changed in decades: deterrence. The United States has these weapons in order to create the conditions in which they are never used,” the report declares. Yet we recall hugely important developments ranging from Mutual Assured Destruction, flexible response, adaptive planning, Global Strike, and preemptive strike options, all of which changed the policies and conditions under which the weapons might be used. The report’s more accurate statement would be: “Presidents have not changed their reluctance in decades to authorize use of nuclear weapons.”

Likewise, the report does not describe the important development after the end of the Cold War, where U.S. nuclear targeting policy expanded from Russia and China and their satellite states to deterring all forms of weapons of mass destruction use by six individual countries today (some of which do not have nuclear weapons).

Non-Use and First Strike

One of the most important conclusions in the Commission report is that the “tradition of non-use serves U.S. interests and should be reinforced by U.S. policy and capabilities.” But what that implies for policies and capabilities is not explained.

Even so, the Commission concludes that not only must U.S. nuclear forces be able to retaliate against an attack, “the United States must also design its strategic forces with the objective of being able to limit damage from an attacker if a war begins.” Such damage-limitation capabilities “are important because of the possibility of accidental or unauthorized launches by a state or attacks by terrorists,” and can be achieved “not only by active defenses, such as missile defenses, “but also by the ability to attack forces that might yet be launched against the United States or its allies.”

Such first strike planning might be relevant with conventional forces against rogue states and terrorists, but first strike planning of course can also be used against other nuclear weapon states as it was during the Cold War against the Soviet Union and China. For the Commission to advocate such a mission for nuclear forces today, however, is deeply troubling because it is a primary reason why Russia insists it must have large numbers of nuclear weapons on alert – a dangerous posture that is a direct threat to the interest of the United States or its allies.

Extended deterrence

The Commission report echoes many of the points raised in the Schlesinger report from December last year about extended deterrence and views expressed by officials from some allies about the importance and mission of nuclear weapons. The good news is that the Commission report makes clear that those allies are not all of the same mind concerning the requirements for extended deterrence and assurance, and that substantive and high-level consultations are needed.

But the Commission does not explain the different capabilities that contribute to extended deterrence, but instead equates “extended deterrence” with nuclear weapons and implicitly non-strategic nuclear weapons. This after NATO for almost two decades has insisted that the U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons deployed in Europe have no military – only a political – role.

The Commission reports that “some allies located near Russia” are saying that “U.S. non-strategic forces in Europe are essential to prevent nuclear coercion by Moscow and indeed that modernized U.S./NATO forces are essential for restoring a sense of balance in the face of Russia’s nuclear renewal.” Yet the Commission does not say that the German foreign minister has called publicly for the withdrawal of the U.S. weapons from Europe, the Belgian Senate has unanimously called for the same, and that the overwhelming majority of Europeans want the weapons to go.

Worst-case analysis is to reference only what is a concern, but that is not the full picture.

The Influence of Russia

After nearly two decades of the Clinton and Bush administrations insisting that Russia is not an adversary and not an immediate contingency for setting U.S. nuclear force levels, the Commission at least admits that Russia largely is what drives U.S. nuclear posturing, saying, “The sizing of U.S. forces remains overwhelmingly driven by the requirements of essential equivalence and strategic stability with Russia.”

In doing so, combined with numerous other references to Russia throughout the report, the Commission essentially reinstates Russia as a central pillar in U.S. nuclear posture planning. The report seems to accept that we are locked in an arms race with Russia and it is surprisingly cautious about how to free ourselves from it. It even concludes that, “the United States should not abandon strategic equivalency with Russia,” because overall equivalence is important to many allies in Europe, and that the “The United States should not cede to Russia a posture of superiority in the name of deemphasizing nuclear weapons in U.S. military strategy.”

While the commission says there is no risk of such an imbalance emerging in strategic weapons in the near-term, the situation is different with non-strategic weapons. The Commission doesn’t know how many Russia has and it can’t say how many the United States has, but while acknowledging that strict U.S.-Russian equivalence in non-strategic force numbers is unnecessary the Commission concludes that the current imbalance is stark and will become apparent as strategic weapons are reduced. This, the report correctly concludes, “points to the urgency of an arms control approach” involving non-strategic weapons.

Overall, the Commission concludes, the United States should “retain enough capacity, whether in its existing delivery systems and supply of reserve warheads or in its infrastructure, to impress upon Russian leaders the impossibility of gaining a position of nuclear supremacy over the United States by breaking out of an arms control agreement.”

Rising China

China looms in the background in many places of the report, reflecting uneasiness among the Commission members about the direction China is taking. But how that direction relates to the U.S. nuclear posture is not analyzed well. Even so, the Commission concludes, in addition to being able to deal with Russian and regional scenarios, the United States “should also retain a large enough force of nuclear weapons that China is not tempted to try to reach a posture of strategic equivalency with the United States or of strategic supremacy in the Asian theater.”

Curiously, the Commission is so concerned about China’s potential nuclear capacity that it urges that Russia – which it is otherwise concerned about – not reduce its nuclear forces too much. This is a mild reversed version of the Reagan administration’s policy that sought China as a nuclear deterrence partner against the Soviet Union.

Therefore…

Based on all of these assumptions (and many more we don’t have room to mention here), the Commission lands on a conclusion that the United States should retain the Cold War nuclear force structure of the Triad. All three legs have unique characteristics that are all needed, the Commission concludes, and because two will be left if one fails, and because “resilience and flexibility of the triad have proven valuable as the number of operationally deployed strategic nuclear weapons has declined.”

Yet the Commission could not come up with a specific force structure or a specific number for the correct size of the U.S. nuclear force, even though it was asked to do so by Congress. The issue is too complex, the authors concluded, and really should be left to deal with by the President in consultation with the military.

The United States should reduce nuclear forces only in bi-lateral negotiations with Russia (and others later), but not pursue unilateral reductions except in reserve warheads — and only if the nuclear warhead production capacity is increased.

Conclusion

In conclusion we were greatly disappointed with the Commission’s report because we see it preoccupied with hedging and failing to offer the leading that is necessary to change status quo.

Indeed, the report seems strangely detached from the President’s vision and the widespread support it and the “gang of four” op-eds have received worldwide.

It would be ironic if the Pentagon’s Nuclear Posture Review ends up recommending bigger changes than the Commission. That shouldn’t be hard.

The task at hand is how to challenge the role of nuclear weapons, we agree with the President, not perpetuate it.

Briefing on US-Russian Nuclear Forces

|

| Vast inventories of nuclear weapons remain after the Cold War arms race ended. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russia’s nuclear forces are expected to drop well below 500 offensive strategic delivery vehicles within the next five years, less than one-third of what’s permitted by the 1991 START treaty. Unless the next U.S. Nuclear Posture Review significantly reduces the number of land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, that single leg of the U.S. Triad of nuclear forces alone could soon include more delivery vehicles than the entire Russian strategic arsenal of land- and sea-based ballistic missiles and long-range bombers. With this in mind, Russia is MIRVing its ballistic missile to keep some level of parity with the United States.

This and more from a briefing I gave this morning at the Arms Control Association meeting Next Steps in U.S.-Russian Nuclear Arms Reductions. I was in good company with Ambassador Linton Brooks, the former U.S. chief negotiator on the START treaty, who spoke about the key issues and challenges the START follow-on negotiators will face, and Greg Thielmann, formerly senior professional staffer of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, who discussed how the a new agreement might be verified through START-style verification tools.

Download: Briefing on US-Russian Nuclear Forces

.

Concern Over Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons

|

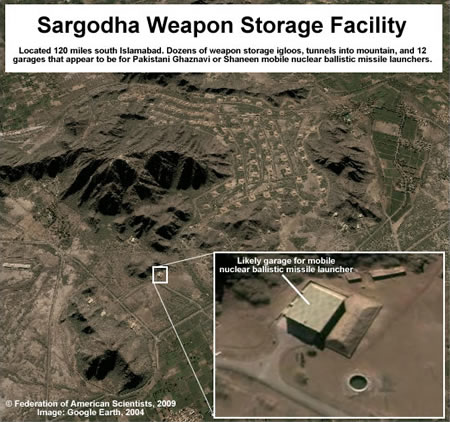

| Pakistan’s nuclear weapons are “widely dispersed” says Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Does that include the large weapons storage complex at Sargodha? Click for image. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has expressed concern over the safety of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons in the light of increasing violence in the country. The weapons “are widely dispersed in the country – they are not at a central location,” she said in what is perhaps the first U.S. public indication of its knowledge about how Pakistan stores its nuclear weapons.

We’re pleased that both Washington Times and the Carnegie Endowment use our estimates for how many nuclear weapons Pakistan and other countries have. For additional information about Pakistan’s nuclear forces, see:

* Preparation of Shaheen-2 ballistic missile launchers.

* Nuclear Notebook: Pakistan’s Nuclear Forces, 2007 (most recent update).

.

Russian Foreign Ministry Responds to FAS/NRDC Study

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russia’s Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sergey Ryabkov, gave a lengthy reaction to the FAS/NRDC report From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence during a press conference Wednesday.

The transcript from the press conference shows that in response to a question that the “report [is] suggesting a possible retargeting of US missile from Russian cities to key economic facilities,” Ryabkov correctly stated: “I have read the report and think that in the Russian media the thesis mentioned by you was taken our of context. That is not the essence of the report.”

Instead, Ryabkov said correctly described that the report “contains an analysis of the hypothetical consequences of the use of nuclear weapons against large industrial and infrastructure facilities, as well as of what the losses might be in the case of the use of warheads of varying yield.” The rest of Ryabkov’s response is reproduced below:

| Question: The Federation of American Scientists has published a report suggesting a possible retargeting of US missiles from Russian cities to key economic facilities. How can you comment on this?

Sergey Ryabkov: I have read this report and think that in the Russian media the thesis mentioned by you was taken out of context. That is not the essence of the report. It contains an analysis of the hypothetical consequences of the use of nuclear weapons against large industrial and infrastructure facilities, as well as of what the losses might be in the case of the use of warheads of varying yield. It is deplorable and regrettable that the really existing facilities on Russian territory were chosen for such an analytical and speculative work. In my opinion, this evidences the authors’ somewhat detached attitude to the fact that much has changed in Russian-US relations in recent years. Considering Russia as a target for potential use of nuclear weapons is not a good idea. This only adds arguments to those who stick to Cold War thinking. In addition, undoubtedly, the very fact of the appearance of that report bears out our thesis that we cannot approach the question of existing potentials abstractly. Intentions, however positive and constructive today, may change tomorrow. The Federation of American Scientists is perfectly aware of this. And the very fact of the appearance of this material suggests that there needs to be serious negotiation, and that the logic of strategic equilibrium and a super-responsible approach to this sphere cannot be sacrificed to any, even the most constructive political intentions or a general favorable disposition. Intentions and dispositions are very ephemeral magnitudes, and the potentials and capacity to deal a blow, as the Association writes quite cynically and coldly about this in its report, enumerating the exponentially increasing millions of victims and speculating about how many more and what kind of warheads are needed for this knockout, are a wake-up call and a reminder to us that we live in a harsh world, whose realities can’t be disregarded.” |

.

Russian Reactions to Minimal Deterrence Study

If you have followed Russian news media recently, you might have gotten the impression that FAS and NRDC are in charge of U.S. nuclear strike planning and are recommending increasing nuclear targeting of Russia.

Of course, neither is true.

Yet major Russian news media – and apparently also the chairman of the Russia’s parliament’s international affairs committee – have so misread and misrepresented the FAS/NRDC study From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence that we are compelled to publish this rebuttal.

Pravda Article Gets It Wrong

A Pravda article under the headline “U.S. retargets nuclear missiles to 12 Russian economic facilities” misrepresents the study as saying that the United States has already developed a new doctrine that is “going to retarget their nuclear missiles from large Russian cities to 12 most important economic facilities.”

|

| The headline and first paragraph of this Pravda article misrepresent what the FAS/NRDC study From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence actually says. |

.

Rather, our study does not say U.S. nuclear weapons are targeted at Russian cities. In fact, we believe cities are explicitly off-limit to U.S. nuclear strike plans unless vital military targets are present.

Nor does the study conclude it has to be 12 industrial targets. Rather, it includes a nominal list of 12 industrial targets for illustrative purposes.

Nor does the study say the U.S. has developed or is implementing a doctrine to retarget nuclear weapons at Russia’s 12 most important economic facilities. Rather, based on U.S. government documents, which we reference in the study, we estimate that U.S. nuclear strike plans already hold at risk nuclear (and other WMD) forces, command and control facilities, military and political leadership, and war-supporting infrastructure. What we’re proposing is to end nuclear planning against the first three of those target categories and limit the remaining effort – in a transition period toward elimination of nuclear weapons – against a sharply curtailed subset of the fourth target category.

Our correction sent to Pravda has so far been ignored.

|

Konstantin Kosachev Interview |

|

|

Konstantin Kosachev, the chairman of the International Affairs Committee of the Russia Duma, misrepresents the FAS/NRDC report. |

Duma Committee Chairman Also Gets It Wrong

In an interview with Russia Today, Konstantin Kosachev, who is chairman of the Russian parliament’s international affairs committee, said he had discussed the study with Carl Levin, chairman of the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee, “in the presence of the U.S. ambassador to Moscow.” Their reaction, Kosachev said, “was something like, ‘strange, we should detarget not retarget our missiles’….”

The interviewer then suggested, and Kosachev agreed, that “reports such as this” can have the effect of “scaremongering” people and “derail relations between the United States and Russia.” Kosachev added that, “This type of reports make [Russian hawks who oppose disarmament] even stronger.”

Yet the U.S. nuclear war plan already contains strike options against facilities in Russia (and other countries with WMD) – and it’s surprising if the chairman of the International Affairs Committee is not aware of this. Russia is not an “immediate contingency,” but it’s very much a contingency because of its large numbers of nuclear weapons and history. The recommendations in the FAS/NRDC report would not “retarget” but significantly curtail existing planning.

“Detargeting” is a controversial word that refers to the 1994 bilateral agreement between Russia and the United States (a similar arrangement was made between China and the United States) according to which the two countries pledged not to store targeting coordinates for the other country in their respective missiles. As a result, U.S. Trident SLBMs and Peacekeeper ICBMs were said no longer to store target coordinates in their onboard computers, and the Minuteman III ICBMs, which for technical reasons had to store some coordinates, were targeted on the oceans.

The objective was to avoid an accidental launch of a missile striking the other country. It was a symbolic “detargeting” agreement, not a constraining “nontargeting” agreement, and both countries continue to design and maintain detailed strike plans against each other. Close to 2,000 warheads are on alert, ready to fly within minutes, despite the “detargeting” agreement.

Our report is proposing that we replace that form of planning with a much more constrained policy during the transition period where the United States and Russia figure out how to retain national security without nuclear weapons.

Vice-Chairman of Russian Council Foreign Affairs Committee Also Gets it Wrong

Vasily Likhachyov [Lykhachev], the Vice-Chairman of the Russian Council’s Foreign Affairs Committee told RIA Novosti that our proposal to go to a minimal deterrence posture represents “an infringement on the fundamental principles of international law.” The basis for this assessment apparently was the 1994 detargeting agreement that he said Russia “strictly adheres to,” and that targeting of facilities in Russia demonstrate “disrespect for the soverignty of the Russian Federation.”

Again, the 1994 detargeting agreement is not a nontargeting agreement (see above), but it is particularly interesting if a member of the Russian Council indicates that it would be against international law if the Russian military targeted the United States with nuclear weapons.

Mr. Likhachyov also questioned our calculations of expected casualties from strikes on Russian infrastructure targets arguing that “anyone who knows what a nuclear weapon is also understands that the effect of an atomic explosion spreads over tens and even hundreds of kilometers.”

But as we explain in the report, the selection of “soft” surface targets such as industry allows the Optimum Height of Burst to be set high above the surface, thus avoiding the generation of large amounts of fallout that Mr. Likhachyov appears to assume comes from any nuclear detonation.

Resources: FAS/NRDC Press Release and Full Report