Response to Critiques Against Fordow Analysis

by Ivanka Barzashka and Ivan Oelrich

Our article “A Technical Evaluation of the Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant” published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists on November 23 and its technical appendix, an Issue Brief, “Calculating the Capacity of Fordow”, published on the FAS website, have sparked quite a discussion among the small community that follows the technical details of Iran’s program, most prominently by Joshua Pollack and friends on armscontrolwonk.com (on December 1 and December 6) and by David Albright and Paul Brannan at ISIS, who have dedicated two online reports (from November 30 and December 4) to critiquing our work. (more…)

Figuring Out Fordow

Last week, my ace research assistant, Ivanka Bazashka, and I published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists an analysis of Iran’s recently revealed Fordow uranium enrichment facility, lying just north of Qom. In summary, we concluded that the timing of the construction and announcement of the facility did not prove an Iranian intention to deceive the agency but certainly raises many troubling questions. The facility is far too small for a commercial enrichment facility, raising additional serious concerns that it might be intended as a covert facility to produce highly enriched uranium (HEU) for weapons. But we also argued that the facility is actually too small to be of great use to a weapons program. A quite plausible explanation is that the facility was meant to be one of several covert enrichment facilities and simply the only one to be discovered. We believe, however, that it is significant that the Iranians assured the agency that they “did not have any other nuclear facilities that were currently under construction or in operation that had not yet been declared to the Agency” because any additional facilities uncovered in the future will be almost impossible to explain innocently. This, however, does not preclude Iran from making a decision to construct new enrichment facilities in the future.

Well, in just a few days, things have changed. We immediately got a lot of emails (some of them quite rude!) challenging our numbers. The Bulletin does not allow for lots of technical detail and we could not put our calculation in the article. So Ivanka and I have written an explanation of the derivation of our numbers. It is the first of a new format for the FAS website, FAS Issue Briefs. I expect that Hans, Matt, Nishal, and others will make good use of the format in the future. You can see our calculations in Calculating the Capacity of Fordow.

We show in our Issue Brief that the oft-cited performance of the Iranian centrifuge is based, at best, on hearsay, and, at worst, circular citations. Reporters get away all the time with citing “high level officials” and the like but analysts do not have that luxury. The reason that we are discussing the Iranian enrichment program is because of grave, immediate policy implications. This not just a question of when Iran might get the bomb, but should we take military action, should we go to war, and when. Ivanka and I conclude that the approach most often taken for estimating Iranian performance is unreliable and will almost certainly overestimate their capabilities. We demonstrate an alternative based on universally accepted, publicly available data.

In particular, we should be very wary of Iranian statements of their own capability. If I said that the National Ignition Facility at Livermore National Laboratory was going to achieve break even laser fusion within a year and cited an interview with the director of NIF, everyone would laugh at me. Statements by Iran about Iran’s capability should be taken with an equally large grain of salt. The Iranians brag about their technological virtuosity, specifically that, in spite of sanctions, they are still able to enrich uranium. It is obviously a matter of national pride. But do they explain to their taxpayers that they are spending billions of dollars to struggle to reproduce technology that the Europeans left behind as obsolete a half century ago and even that they do inefficiently? Our calculations, based on publicly available IAEA reports, shows that Iran is operating its centrifuges at 20-25% of what we might expect.

The second big change is Iran’s announcement of ten new future enrichment facilities. We argued in our Bulletin article that it was significant that Iran told the IAEA that there were no undeclared facilities waiting to be discovered. Ivanka was more skeptical, saying that this declaration meant little if the Iranians used their definition of when they were required to “declare.” I thought it more significant because any future discovery would be impossible to portray as innocent. On the other hand, we also said that the Fordow facililty did not make much sense except as part of a network of clandestine facilities. Well, the Iranians helped resolve that question when a few days later they announced that they were going to build ten new enrichment facilities, probably similar to Fordow. It is getting harder and harder to give Iran the benefit of the doubt.

North Korea: FAS Says We Have Nukes!

|

By Hans M. Kristensen

North Korea’s news agency – Korean Central News Agency – apparently has issued a statement saying that “The Federation of American Scientists of the United States has confirmed (North) Korea as a nuclear weapon state.” According to a report in the Korea Herald, the statement said a FAS publication issued in November listed North Korea as among the nine countries that possess nuclear weapons.

It’s certainly curious that they would need our reaffirmation, but after two nuclear tests we feel it is safe to call North Korea a nuclear weapon state. However, the agency left out that our assessment comes with a huge caveat:

“We are not aware of credible information on how North Korea has weaponized its nuclear weapons capability, much less where those weapons are stored. We also take note that a recent U.S. Air Force intelligence report did not list any of North Korea’s ballistic missiles as nuclear-capable.”

In other words, two experimental nuclear test explosions don’t make a nuclear arsenal. That requires deliverable nuclear weapons, which we haven’t seen any signs of yet. Perhaps the next statement could explain what capability North Korea actually has to deliver nuclear weapons.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Estimated Nuclear Weapons Locations 2009

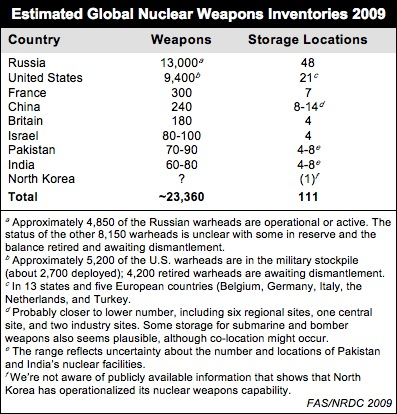

Some 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at 111 locations around the world

.The world’s approximately 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at an estimated 111 locations in 14 countries, according to an overview produced by FAS and NRDC.

Nearly half of the weapons are operationally deployed with delivery systems capable of launching on short notice.

The overview is published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and includes the July 2009 START memorandum of understanding data. A previous version was included in the annual report from the International Panel of Fissile Materials published last month.

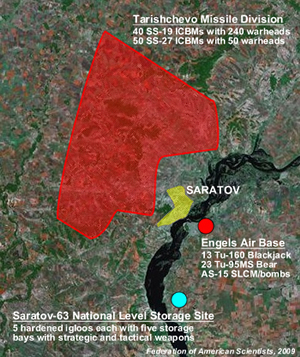

More than 1,000 nuclear weapons surround Saratov.

Russia has an estimated 48 permanent nuclear weapon storage sites, of which more than half are on bases for operational forces. There are approximately 19 storage sites, of which about half are national-level storage facilities. In addition, a significant number of temporary storage sites occasionally store nuclear weapons in transit between facilities.

This is a significant consolidation from the estimated 90 Russian sites ten years ago, and more than 500 sites before 1991.

Many of the Russian sites are in close proximity to each other and large populated areas. One example is the Saratov area where the city is surrounded by a missile division, a strategic bomber base, and a national-level storage site with probably well over 1,000 nuclear warheads combined (Figure 2).

The United States stores its nuclear weapons at 21 locations in 13 states and five European countries. This is a consolidation from the estimated 24 sites ten year ago, 50 at the end of the Cold War, and 164 in 1985 (see Figure 3).

Approximately 50 B61 nuclear bombs inside an igloo at what might be Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada. Seventy-five igloos at Nellis store “one of the largest stockpile in the free world,” according to the U.S. Air Force, one of four central storage sites in the United States.

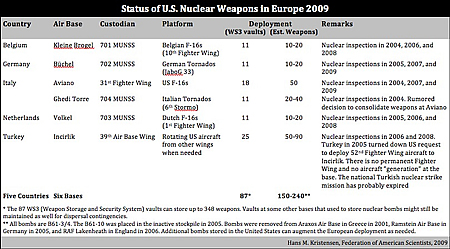

Europe has about the same number of nuclear weapon storage locations as the Continental United States, with weapons scattered across seven countries. This includes seven sites in France and four in Britain. Five non-nuclear NATO countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey) still host U.S. nuclear weapons first deployed there during the Cold War.

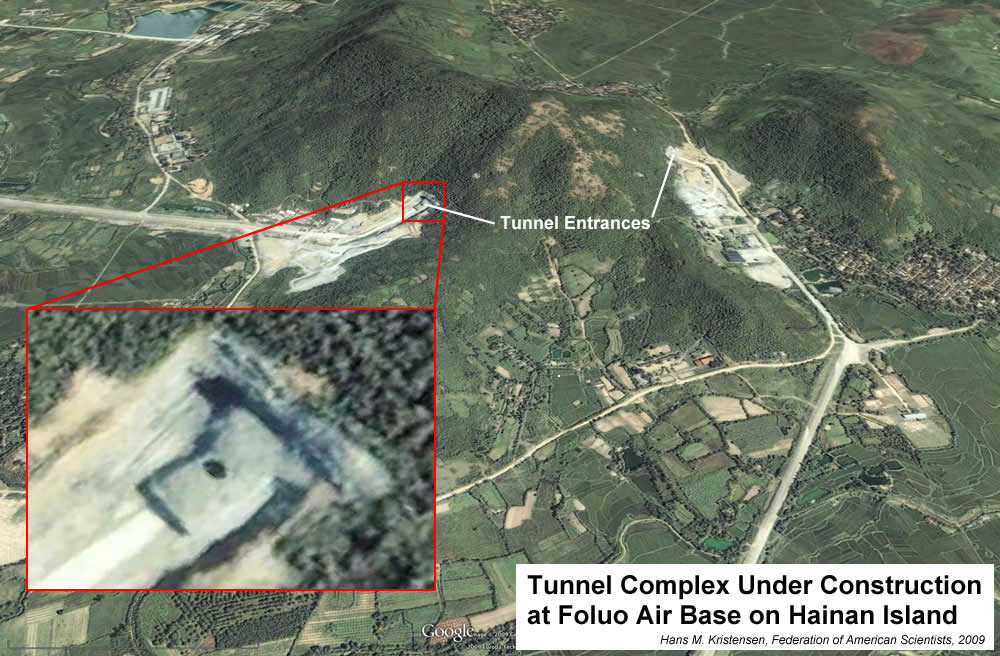

We estimate that China has 8-14 facilities associated with nuclear weapons, most likely closer to the lower number, near bases with units that operate nuclear missiles or aircraft. None of the weapons are believed to be fully operational but stored separate from delivery vehicles at sites controlled by the Central Military Commission.

Where does China store nuclear warheads for its ballistic missile submarines? The naval base near Julin on Hainan Island has extensive underground facilities. An alternative to the base itself could potentially be a facility elsewhere on the island, such as Foluo Air Base where construction of an underground facility began five years before the first SSBN arrived at Hainan. Or are the weapons stored on the mainland? Click image to enlarge.

Israel probably has about four nuclear sites, whereas the nuclear storage facilities in India and Pakistan are – despite many rumors – largely undetermined. All three countries are thought to store warheads separate from delivery vehicles.

Despite two nuclear tests and many rumors, we are unaware of publicly available evidence that North Korea has operationalized its nuclear weapons capability.

Warhead concentrations vary greatly from country to country. With 13,000 warheads at 48 sites, Russian stores an average of 270 warheads at each location. The U.S. concentration is much higher with an average of 450 warheads at each location. These are averages, however, and in reality the distribution is thought to be much more uneven with some sites only storing tens of warheads.

Finally, a word of caution is in order: estimates such as these obviously come with a great deal of uncertainty, as we don’t have access to classified intelligence estimates. Based on publicly available information and our own assumptions we have nonetheless produced a best estimate that we hope will assist the public debate. Comments and suggestions are encouraged so we can adjust the overview in the future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

China’s Noisy Nuclear Submarines

|

| China’s newest nuclear submarines are noisier than 1970s-era Soviet nuclear submarines. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

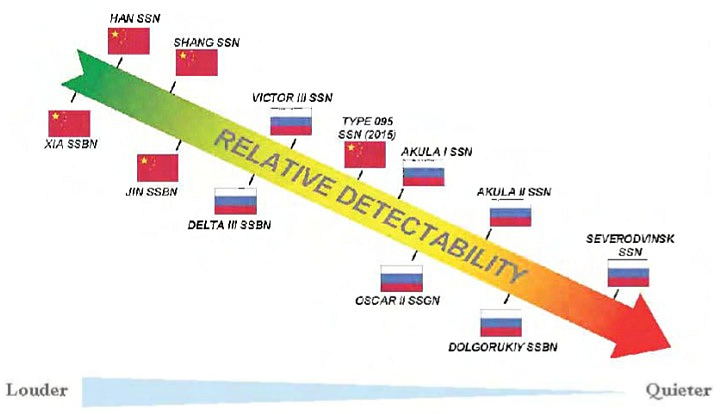

China’s new Jin-class ballistic missile submarine is noisier than the Russian Delta III-class submarines built more than 30 years ago, according to a report produced by the U.S. Navy’s Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI).

The report The People’s Liberation Army Navy: A Modern Navy With Chinese Characteristics, which was first posted on the FAS Secrecy News Blog and has since been removed from the ONI web site [but now back here; thanks Bruce], is to my knowledge the first official description made public of Chinese and Russian modern nuclear submarine noise levels.

Force Level

The report shows that China now has two Jin SSBNs, one of which is based at Hainan Island with the South Sea Fleet, along with two Type 093 Shang-class nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSN). The Jin was first described at Hainan in February 2008 and the two Shangs in September 2008. The second Jin SSBN is based at Jianggezhuang with the North Sea Fleet alongside the old Xia-class SSBN and four Han-class SSNs.

The report confirms the existence of the Type 095, a third-generation SSN intended to follow the Type 093 Shang-class. Five Type 095s are expected from around 2015. The Type-95 is estimated to be noisier than the Russian Akula I SSN built 20 years ago.

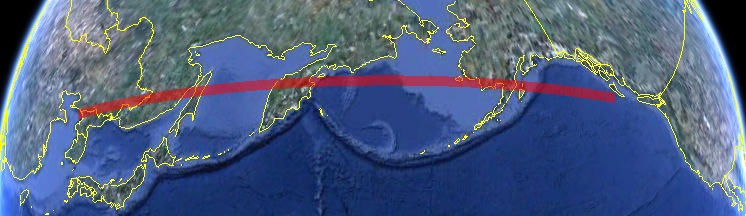

Missile Range

The ONI report states that the JL-2 sea-launched ballistic missile on the Jin SSBNs has a range of ~4,000 nautical miles (~7,400 km) “is capable of reaching the continental United States from Chinese littorals.” Not quite, unless Chinese littorals extend well into the Sea of Japan. Since the continental United States does not include Alaska and Hawaii, a warhead from a 7,400-km range JL-2 would fall into the sea about 800 km from Seattle. A JL-2 carrying penetration aids in addition to a warhead would presumably have a shorter range.

|

Julang-2 SLBM Range According to ONI |

|

| Although the ONI report states that the Julang-2 can target the Continental United States, the range estimate it provides is insufficient to reach the lower 48 states or Hawaii. |

.

Alaska would be in range if the JL-2 is launched from the very northern parts of Chinese waters, but Hawaii is out of range unless the missile is launched from a position close to South Korea or Japan. The U.S. Defense Department’s 2009 report to Congress on the Military Power of the People’s Republic of China also shows the range of the JL-2 to be insufficient to target the Continental United States or Hawaii from Chinese waters. The JL-2 instead appears to be a regional weapon with potential mission against Russia and India and U.S. bases in Guam and Japan.

Patrol Levels

The report also states that Chinese submarine patrols have “more than tripled” over the past few years, when compared to the historical levels of the last two decades.

That sounds like a lot, but given that the entire Chinese submarine fleet in those two decades in average conducted fewer than three patrols per year combined, a trippling doesn’t amout to a whole lot for a submarine fleet of 63 submarines. According to data obtained from ONI under FOIA, the patrol number in 2008 was 12.

Since only the most capable of the Chinese attack submarines presumably conduct these patrols away from Chinese waters – and since China has yet to send one of its ballistic missile submarines on patrol – that could mean one or two patrols per year per submarine.

Implications

The ONI report concludes that the Jin SSBN with the JL-2 SLBM gives the PLA Navy its first credible second-strike nuclear capability. The authors must mean in principle, because in a war such noisy submarines would presumably be highly vulnerabe to U.S. or Japanese anti-submarine warfare forces. (The noise level of China’s most modern diesel-electric submarines is another matter; ONI says some are comparable to Russian diesel-electric submarines).

That does raise an interesting question about the Chinese SSBN program: if Chinese leaders are so concerned about the vulnerability of their nuclear deterrent, why base a significant portion of it on a few noisy platforms and send them out to sea where they can be sunk by U.S. attack submarines in a war? And if Chinese planners know that the sea-based deterrent is much more vulnerable than its land-based deterrent, why do they waste money on the SSBN program?

The answer is probably a combination of national prestige and scenarios involving India or Russia that have less capable anti-submarine forces.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

JASON and Replacement Warheads

|

|

Claims that nuclear weapons need to be as safe as a coffee table might drive warhead replacement |

By Hans M. Kristensen and Ivan Oelrich

The latest study from the JASON panel is an unambiguous rejection of claims made by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), the nuclear weapon labs, defense secretary Robert Gates, and U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) that some or all U.S. nuclear weapons should be replaced to ensure the future reliability of the arsenal.

The executive summary of the study, Lifetime Extension Program (LEP), finds “no evidence that accumulation of changes incurred from aging and LEPs have increased risk to certification of today’s deployed nuclear warheads.” The study concludes that the lifetime of today’s nuclear warheads “could be extended for decades, with no anticipated loss in confidence, by using approaches similar to those employed in LEPs today.” [Emphasis added.]

The JASON appears to have prevented a wasteful and counterproductive nuclear warhead replacement program. Even so, we expect parts of the report’s conclusions to be used by proponents of nuclear warhead replacements in the months and years ahead.

The Surety Argument

With JASON’s rejection in 2006 that pit aging is a reason to build replacement warheads, and its latest conclusion that stockpile reliability is achievable with the existing Live Extension Programs, only two of the core justifications used by proponents of RRW remains: surety and training. (There is no agreed definition of the terms safety, security, and surety. The DOD defines that nuclear safety reduces the probability of accidental explosion of the warhead; security reduces the possibility of unintentional or unauthorized intentional use of the warhead; surety combines these aspects.)

The report leaves the door open for replacement warheads by concluding that addition of nuclear surety or use-control features to the nuclear explosive package of reentry vehicles on ballistic missiles (W76, W78, W87, and W88) “would require reuse or replacement LEP options.” Note that replacement warhead would not necessarily be a new design, but could be new components in an existing design.

Additional use-control, not warhead reliability, has thus become the main technical justification for building replacement warheads and we expect to see a sudden emphasis on surety by those who want to build new warheads.

This begs the questions: how much surety is enough, who sets the bar, and what is it worth?

All U.S. warheads contain one or several surety features to prevent unauthorized use and accidents (see Table). The last time the United States went through a stockpile-wide safety and security related upgrade was in the early 1990s. Back then several weapons were phased out because they didn’t meet new safety and security standards, and new features were added to others. Not all nuclear weapons were created equal, however, and those that were seen as too important to retire were allowed to remain in the inventory even thought they did not meet the standard. But they will be gone soon.

|

U.S. Nuclear Warhead Surety Features |

|

| All U.S. nuclear warheads have surety features but details vary greatly due to history and deployment. Click for table. |

.

After 9/11, the administration began arguing for raising the standard again. National Security Presidential Directive 28 (NSPD-28) issued in June 20, 2003, ordered the “incorporation of enhanced surety features independent of any threat scenario,” a capability-based safety philosophy based on technology rather than threats. Under the headline “Urgency of RRW,” NNSA Director Thomas D’Agostino told Congress in February 2008 that “after 9/11 we realized that the security threat to our nuclear warheads had fundamentally changed.”

We have repeatedly probed officials about this alleged change, and they say it has to do with fear that terrorists will do anything to steal and use a nuclear weapon. The theory was that terrorists would go to greater length to steal U.S. nuclear weapons than the Soviet Union. Existing security features and well-protected storage sites are no longer sufficient; a nuclear weapon must be as inherently safe against unauthorized use as a coffee table, as one senior official recently put it.

Who can be against safety of nuclear weapons? But if the price is several billion dollars then it is appropriate to ask what the surety and safety requirements are for U.S. nuclear weapons, how they have been set, by whom, and for what purpose. Another way to pose the question is: How will we know when we are done?

Since 9/11 the government has already spent huge sums to improve the physical security of nuclear weapons at bases and storage sites, and has upgraded use control features of some weapons. The safety of US nuclear weapons is probably better today than it has ever been. The greatest weakness is almost certainly administrative, as when military personnel loose track of the weapons, which happened in August 2007 at Minot Air Force Base. We also note that suggestions to increase surety by changing the deployment and readiness of nuclear weapons, for example, taking weapons off alert or removing warheads from missiles and storing them separately, are dismissed out of hand. So there are some actions that could improve surety that are clearly out of bounds.

The claim that the weapons themselves have to be made even more secure came later. It was not a prominent component of the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review, and a concurrent review of “all activities involved in maintaining the highest standards of nuclear weapons safety, security, control, and reliability” did not result in a list of new warhead surety features in the subsequent Stockpile Stewardship Plans. Indeed, the 2004-2008 plan instead declared: “The physical protection and security of nuclear weapons…remains [sic] strong….”

But after the Bush administration in 2004-2005 began lobbying Congress for authorization to begin industrial-scale production of new warheads to replace existing ones, the claim that additional warhead surety features are necessary has become a key justification. For example, STRATCOM has recently proposed consolidating four versions of the B61 bomb into one based on the need for additional surety features (see Figure).

|

New Bombs For Surety |

|

| STRATCOM has recently used hypothetical needs for additional surety features as justification for building a new version of the B61 nuclear bomb. Click to download. |

.

The slide includes some interesting assertions and assumptions underlined by a quote by Osama bin Laden saying it is a religious duty to acquire nuclear weapons to defend Muslims. The main assertion is that current U.S. nuclear weapons are “not designed to address potential for nuclear terrorism.” That certainly depends on what the “potential” is. If it means terrorists trying to force their way into a storage facility, steal a weapon, and detonate it somewhere at their choosing, the claim is almost certainly wrong. If on the other hand “potential” refers to the most worst-case scenario, where all U.S. safety and defensive efforts fail, then everything is of course possible. But worst-case scenarios are not interesting when assessing what is necessary; realistic scenarios are.

The statement that only a small percentage of the stockpile has “internal disablement features” to prevent unauthorized use probably refers to bombs and cruise missiles that happen to make up a smaller portion of the stockpile than reentry vehicles for ballistic missiles. But as the Jason report concludes, “All proposed surety features for today’s air-carried systems could be implemented through reuse LEP options.” Reentry vehicle warheads do not have these surety features, which might be a problem, but adding some does not necessarily requirement replacements, according to JASON.

The claim that all weapons lack modern surety features “to further reduce” the possibility that an accident could trigger a nuclear yield is of course true because one can always add more security features to further reduce the possibility. The sky is the limit. The issue is, however, how much is needed. In fact, once the remaining W62 warheads are retired (DOD missed the October 1, 2009, deadline), the entire stockpile will contain surety features that reduce the chance of warhead detonation due to accidents or terrorist attacks to less than one in a million.

The Skills Argument

Proponents of the RRW frequently have argued that it is necessary to build replacement warheads to keep a cadre of scientists, designers, and builders well trained and at the ready so that if sometime in the future we need new weapons we will be able to produce them. The JASON recommends improving the surveillance programs, but the language that “Continued success of the stockpile stewardship is threatened by lack of program stability, placing any LEP strategy at risk,” seems to criticize the NNSA and labs for being so fixated on building new bombs that the surveillance program has suffered.

The training argument depends on a combination of assumptions: (1) the country will eventually need new nuclear weapons and these will need to be sophisticated weapons requiring high levels of expertise, (2) the expertise needed for continuing stockpile maintenance is not adequate to maintain the expertise needed to design and build new weapons, and (3) the knowledge and skills needed to build new weapons cannot be written down and can only be preserved over the next two or three decades by keeping it alive in people. The truth of all of these assumptions depends in large part on choices we make about the future missions and requirements for nuclear weapons. None of the assumptions is of necessity true.

Recommendations

The quest for new weapons is not dead yet. Now that one main justification, reliability, has been deflated, those who want to continue to build new warheads are more likely to retreat to the second line of defense rather than surrender. We expect the NNSA, the nuclear laboratories, and the military to focus their efforts on surety technology and laboratory expertise. We need Congress (and perhaps JASON) to study the need for new surety features, and determine what level is sufficient for real-world threat levels.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Change at the United Nations

by: Alicia Godsberg

The First Committee of this year’s 64th United Nations General Assembly (GA) just wrapped up a month of meetings. The GA breaks up its work into six main committees, and the First Committee deals with disarmament and international security issues. During the month-long meetings, member states give general statements, debate on such issues as nuclear and conventional weapons, and submit draft resolutions that are then voted on at the end of the session. Comparing the statements and positions of the U.S. on certain votes from one year to the next can help gauge how an administration relates to the broader international community and multilateralism in general. Similarly, comparing how other member states talk about the U.S. and its policies can give insight into how likely states may be to support a given administration’s international priorities.

The Obama administration will certainly be looking in the near future for support on some of its new international priorities – the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference is happening in May, 2010 and the U.S. delegation will likely seek to promote certain non-proliferation measures, such as universal acceptance of the Additional Protocol and the creation of a nuclear fuel bank.[i] However, many states see these and other proposed non-proliferation measures as further restrictions on their NPT rights while the U.S. and the other NPT nuclear weapon states parties (NWS) continue to avoid adequate progress in implementing their nuclear disarmament obligation. At the same time, other states with nuclear weapons continue to develop them (and the fissile material needed for them) with no regulation at all. The United Nations (UN) is the court of world public opinion, a place where all member states have a voice. If President Obama expects to win support for his non-proliferation agenda next May, he needs to win the GA’s support by showing that the U.S. is ready to engage multilaterally again and take seriously its past commitments and the concerns of other states.

While the U.S. continued to vote “no” on certain nuclear disarmament resolutions[ii], there were some noteworthy changes in the position of the new U.S. administration during this year’s voting. One major shift away from the Bush administration’s voting through last year was a change to a “yes” vote on a resolution entitled, “Renewed determination towards the total elimination of nuclear weapons.” In fact, the U.S. also became a co-sponsor of this resolution. The change in the U.S. position on the CTBT was likely an important factor in this reversal, as the resolution “urges” states to ratify the Treaty, something Bush opposed but the Obama administration strongly supports. Similarly, the U.S. voted “yes” on the resolution entitled, “Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty,” and for the first time all five permanent members of the Security Council joined this resolution as co-sponsors.

The change in the U.S. position on the CTBT was welcomed by many delegations on the floor. Indonesia stated it would move to ratify the Treaty once the U.S. ratifies, and China has hinted at a similar position. Non-nuclear weapon states have found the past U.S. position – that no new states should have nuclear weapons programs while the U.S. continues its own without any legal restrictions on the right to test nuclear weapons – to be hypocritical. Add to this that the U.S. and other NWS have promised to work for the entry into force of the CTBT in the final documents of the 1995 and 2000 NPT Review Conferences, even using this promise as a way to get the indefinite extension of the NPT in 1995, and it may be that the CTBT is the sine qua non for the future of the NPT regime.

The U.S. delegation gave some strong signals that the Obama administration may be planning on decreasing the operational readiness of U.S. nuclear weapons (so-called “de-alerting”) in the upcoming Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). This speculation comes from remarks on the floor, when the sponsors of a resolution that had been tabled for the past two years entitled, “Decreasing the operational readiness of nuclear weapon systems” stated they would not be tabling the resolution this year.[iii] The sponsors stated that they would not be tabling the resolution because nuclear posture reviews were underway in a few countries and they hoped leaving the issue of operational readiness off the floor would, “facilitate inclusion of disarmament-compatible provisions in these upcoming reviews and help maintain a positive atmosphere for the NPT Review Conference.” Apparently the U.S. delegation pushed to leave this resolution off the floor, not wanting to vote against it again while the NPR was underway. Many took these political dealings as a sign that the Obama administration was pushing at home for a review of the operational readiness of the U.S. nuclear arsenal. Decreasing the operational readiness of U.S. nuclear forces would be a welcome change in the U.S. nuclear posture, adding time for decision-making and deliberation during a potential nuclear crisis. Such a change would also send an unambiguous signal to the international community that the U.S. was taking its nuclear disarmament obligation seriously, the perception of which is necessary for cooperation on non-proliferation goals in 2010 and beyond.

Another long-standing U.S. position apparently under review by the Obama administration relates to outer space activities. The Bush administration spoke of achieving “total space dominance” and the U.S. has been against the multilateral development of a legal regime on outer space security for 30 years. U.S. Ambassador to the CD Garold N. Larson spoke during the First Committee’s thematic debate on space issues, saying that the administration is now in the process of assessing U.S. space policy, programs, and options for international cooperation in space as part of a comprehensive review of space policy. The U.S. delegation changed its vote on the resolution, “Prevention of an arms race in outer space” from a “no” last year to an abstention this year, and did not participate in a vote on a resolution entitled, “Transparency and confidence-building measures in outer space” due to the current review of space policy. The U.S. message on outer space issues seemed to be that here too the new administration was looking to engage multilaterally instead of pursuing a unilateral agenda.

Under Secretary of State Ellen Tauscher mentioned another change in U.S. policy in her remarks to the First Committee – the support for the negotiation of an effectively verifiable fissile material cutoff treaty (FMCT)[iv]. Previously, the Bush administration had removed U.S. support for negotiating an FMCT with verification protocols, stating that such a Treaty would be impossible to verify. Without verification measures, which were part of the original Shannon Mandate[v] for the negotiation of an FMCT, many non-nuclear weapon states saw little value in negotiating the Treaty. Further, because verification was part of the original package for negotiation, the Bush administration’s change was seen as dismissive of the multilateral process and a further example of U.S. unilateral action without regard for the concerns of other countries or the value of multilateral processes. With the U.S. delegation stating that it supported negotiating an effectively verifiable FMCT as called for under the original mandate, the Obama administration again showed a marked change from its predecessor and a willingness to engage in multilateralism.

What does all this mean? President Obama stood before the world in Prague and pledged that the U.S. would work toward achieving a world free of nuclear weapons and has brought the issue of nuclear disarmament back to the forefront of international politics. President Obama recognizes that the U.S. cannot work toward this vision alone – we have security commitments to allies that need to be addressed as the U.S. makes changes to its strategic posture and policy, there are other nuclear armed countries that need to have the same goal and work toward it in a safe and verifiable manner, and there is the danger of nuclear terrorism and unsecured fissile material that needs to be addressed by the entire global community. In other words, the new administration recognizes the value in collective action to solve global problems, and at the 64th annual meeting of the UN General Assembly this year, the U.S. began putting some specific meaning behind President Obama’s general statements. With a pledge to work toward ratifying the CTBT at home and to work for other ratifications necessary for the Treaty’s entry into force, a renewed commitment to negotiating an effectively verifiable FMCT, and changes in long standing positions on outer space security and likely also on operational readiness of nuclear weapons, the Obama administration has shown the U.S. is back as a willing partner to the institutions of multilateral diplomacy. More than anything, this change – if it turns out to be genuine – will help advance President Obama’s non-proliferation goals at the upcoming NPT Review Conference. Of course the U.S. has internal battles to overcome, such as Senate ratification of the CTBT, but if promise and policy reviews are met with actions that can easily be interpreted by the rest of the world as genuine nuclear disarmament measures, President Obama has a greater chance to achieve an atmosphere of cooperation on U.S. non-proliferation goals at the upcoming NPT Review Conference in May, 2010.

[i] President Obama’s non-proliferation agenda was presented on May 5, 2009 to the United Nations by Rose Gottemoeller (Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Verification, Compliance, and Implementation) at the Third Session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2010 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference. http://www.state.gov/t/vci/rls/122672.htm

[ii] A few of the nuclear disarmament-related resolutions the US voted “no” on were: Towards a nuclear weapon free world: accelerating the implementation of nuclear disarmament commitments; Nuclear disarmament; and Follow-up to nuclear disarmament obligations agreed to at the 1995 and 200 Review Conferences of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

[iii] The US had voted “no” on this resolution the past two years, joined only by France and the UK.

[iv] Ellen Tauscher mentioned that the US “looks forward to the start of negotiations on a Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty” without further elaboration. President Obama, unlike President Bush, has made clear that his administration supports an effectively verifiable FMCT. For examples of this new policy direction, see: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/us-eu-joint-declaration-and-annexes; http://geneva.usmission.gov/2009/06/04/gottemoeller/; and http://www.state.gov/t/vci/rls/127958.htm

[v] Historical background on FMCT negotiations: http://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/legal/fmct.html

Iran Owned Part of Eurodif – Document Posted

By Ivanka Barzashka

FAS has posted a report on “Enrichment Supply and Technology Outside the United States” by S. A. Levin and S. Blumkin from the Enrichment Department of the Oak Ridge Gaseous Diffusion Plant, operated at the time by Union Carbide. The document, prepared for the U.S. Energy Research and Development Administration, reviews international uranium enrichment capacity and isotope separation technology as of 1977.

Apart from being of historical interest, the report explicitly states that Eurodif, a French-organized multinational enrichment consortium, was in part owned by Iran.

“The membership and apportionment of shares in Eurodif has been changeable. Presently, it is constituted by Belgium and Spain 11% each. Italy 25%, France 28% and Sofidif 25%, which is 40% owned by Iran and 60% by France.”

“In 1975, another consortium called Coredif with the same multinational membership as Eurodif but a different distribution of shares (Eurodif 51%, France 29% and Iran 20%) was organized to assess future nuclear demand and build a second Eurodif-type plant if the study results justified it.”

This is consistent with Iran’s claims that it owned shares of the enrichment company prior to the Islamic Revolution in 1979. This claim has been confirmed by the French government, but Iran has never received enriched uranium from the company.

The document has a disclaimer that “[i]t should not be presumed that the inclusion in this presentation of any reported information necessarily attests to its validity.”

Germany and NATO’s Nuclear Dilemma

|

| Security personnel monitor nuclear weapons transport at German air base. Image: USAF |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The new German government has announced that it wants to enter talks with its NATO allies about the withdrawal of the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Germany.

The announcement coincides with the Obama administration’s ongoing Nuclear Posture Review, which is spending an unprecedented amount of time pondering the “international aspects” of to what extent nuclear weapons help assure allies of their security.

Germany and many other NATO countries apparently don’t want to be protected by U.S. forward-deployed tactical nuclear weapons, which they see as a relic of the Cold War that locks NATO in the past and prevents it’s transition to the future.

Current Deployment

The U.S. Air Force currently deploys approximately 200 B61 nuclear bombs at six bases in five NATO countries (see Table 1). The weapons are the last remnant of a vast force of more than 7,000 tactical nuclear weapons that used to clutter bases in Europe during the Cold War as a defense against the Soviet threat and the Warsaw Pact’s large conventional forces.

|

Table 1: |

|

| Approximately 200 U.S. nuclear bombs are currently deployed at six bases in five European countries. Click image to download larger table. |

.

The bombs are scattered among 87 individual aircraft shelters where they are stored in underground vaults. Although well protected, this widespread deployment contrasts normal U.S. nuclear weapons security procedures that favor consolidation at as few locations as possible.

An Air Force investigation concluded in 2008 that “most” sites in Europe did not meet U.S. security requirements. NATO officials publicly dismissed the conclusion, and a visit by a team from the U.S. government apparently found issues but nothing alarming.

Consolidation Versus Withdrawal

Rumors have circulated for several years about plans to consolidate the remaining weapons from the current six bases to one or two bases. The plans would either terminate the Cold War arrangement of non-nuclear NATO countries being assigned strike missions with U.S. nuclear weapons, or move the weapons to U.S. bases with the promise that they could be returned if necessary.

Consolidation has occurred frequently since the end of the Cold War: withdrawal from Turkish national bases Akinci and Balikesir in 1995; withdrawal from German national bases Memmingen and Norvenich in 1996; withdrawal from Greek national base Araxos in 2001; withdrawal from Ramstein in Germany in 2005 ; withdrawal from Lakenheath in England in 2006. Another round of consolidation would just be another slow step toward the inevitable: withdrawal from Europe.

Consolidation of the remaining nuclear bombs to the two U.S. southern bases at Aviano in Italy and Incirlik in Turkey would be problematic for two reasons. First, Turkey does not allow the U.S. Air Force to deploy the fighter-bombers to Incirlik that are needed to deliver the bombs if necessary, and has several times restricted U.S. deployments through Turkey into Iraq. Given that history, and apparent doubts about Turkey’s future direction, is nuclear deployment in Turkey a credible posture? Second, absent a fighter wing deployment to Incirlik, Aviano carries the overwhelming burden of conventional air operations on the southern flank of NATO, operations that are already burdened by the nuclear addendum and would further be so by a decision to consolidate the nuclear mission at the base.

An End to NATO Nuclear Strike Mission

The German policy to seek withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Büchel Air Base essentially means – if implemented – the unraveling of the NATO nuclear strike mission, whereby non-nuclear NATO countries equip and train their air forces to deliver U.S. nuclear weapons. Germany shares this mission with Belgium, Italy, and the Netherlands, while Greece and Turkey opted out in 2001.

|

Table 1: |

|

| German personnel attach a U.S. B61 nuclear bomb shape to a German Tornado fighter-bomber under supervision of U.S. personnel. As a signatory to the NPT Germany has pledged not to receive nuclear weapons, yet, as this picture illustrates, is preparing its military to do so anyway. Image: German Ministry of Defense/Der Spiegel |

.

The mission is highly controversial because these countries as signatories to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) have all pledged not to receive nuclear weapons: “undertakes not to receive the transfer from any transferor whatsoever of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices or of control over such weapons or explosive devices directly, or indirectly.” Yet that’s precisely what the NATO strike mission entails: peacetime preparations for direct transfer of nuclear weapons and control over such weapons in times of war.

The mission is clearly inconsistent with if not the letter then certainly the spirit of the NPT. The arrangement was tolerated during the Cold War but is incompatible with nonproliferation policy is the 21st century.

Real-World Security Commitments

Germany is one of the “30-plus” allies and friends that some have argued recently need to be protected by nuclear weapons to prevent them from developing their own nuclear weapons. It has even been suggested that extended deterrence necessitates equipping the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter with nuclear capability.

Yet high-level officials in both the White House and the Pentagon have already concluded that the United States no longer needs to deploy nuclear bombs in Europe to meet its security obligations to NATO. Those security obligations today have very little to do with nuclear weapons and extended deterrence is predominantly served by non-nuclear means. The limited role nuclear weapons still serve can adequately be fulfilled by long-range weapon systems just as they have been in the Pacific for 17 years. Whether the ongoing Nuclear Posture Review will reflect those views will be seen in February 2010 when the review is completed.

|

Figure 2: |

|

| The U.S. nuclear bombs were deployed in Europe to defend NATO against a conventional attack from the Warsaw Pact, a threat that has long-since disappeared. |

Regardless, Germany apparently does not want to be protected by U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe. Neither does Belgium, where the parliament unanimously has requested nuclear bombs be withdrawn. Dutch officials privately say that they see no need for the deployment either. In fact, in all of the countries where nuclear weapons are deployed, an overwhelming majority of the public favors withdrawal. Turkey – one of the countries said by some to oppose withdrawal – has the highest public support for withdrawal of any of the countries that currently store nuclear weapons. In the long run this is a serious challenges for NATO; that its nuclear posture is so clearly out of sync with public opinion.

The biggest challenge seems to be to convince Poland and Turkey that withdrawal will not undermine the U.S. security commitment. Poland is worried about Russia; Turkey about Iran. But tactical nuclear weapons were the Cold War way of addressing such concerns. What’s needed now is focused diplomacy, stewardship, and reaffirmation of non-nuclear arrangements to convince these countries that the nuclear bombs that were deployed in Europe to defend NATO against a conventional attack from the Warsaw Pact can now finally be withdrawn.

The previous two German governments also favored withdrawal but did little to push the issue. Whether the new government will be any different will be put to the test during NATO’s ongoing revision of its Strategic Concept scheduled for completion in 2010.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Clinton On Nuclear Preemption

|

|

No preemptive nuclear options, according to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

During an interview with Ekho Moskvy Radio last week, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton was asked if “the American [nuclear] doctrine incorporate[s] preemptive nuclear strikes against an aggressor?”

The Secretary’s answer was: “No, no.”

Ahem….

Secretary Clinton’s denial that U.S. nuclear doctrine incorporates preemptive strike options is at odds with numerous statements made by U.S. government officials over the past eight years, who have sought to give precisely the opposite impression; that the nuclear doctrine does indeed also contains preemptive options. An draft revision of U.S. nuclear doctrine in 2005 revealed such options.

So unless the U.S. has changed its nuclear doctrine since the Bush administration, then the Secretary’s denial is, well, at odds with the doctrine.

The confusion could of course be academic; that Secretary Clinton is under the impression that the doctrine includes preventive, no preemptive, strike options. Or perhaps she simply doesn’t know, yet believes that preemptive nuclear strike options should not be part of U.S. nuclear doctrine. It is of course important that the U.S. Secretary of State knows what U.S. nuclear policy is, since she is in charge of negotiations with Russia about the START Follow-On treaty and laying the groundwork for a subsequent and more substantial treaty and nuclear relationship.

The context of her denial was an Izvestia interview with Nikolai Patrushev, Secretary of Russia’s Security Council, about Russia’s ongoing review of its nuclear doctrine. Mr. Patrushev reportedly said: “In situations critical to national security, a nuclear strike, including a preventative one, against an aggressor is not ruled out.”

Russia’s current doctrine already allows preemptive strikes, something the Kremlin says it needs because of Russian inferior conventional forces. Whether the new revision will change or reaffirm preemptive options remains to be seen.

Background: Counterproliferation and US Nuclear Strategy (2009); Global Strike Chronology (2006); Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations (2005)

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Obama Asks UN De-Alerting Resolution to Wait

|

| President Barack Obama, here shown speaking to the United Nations in September, is seeking to delay a UN Resolution calling for De-Alerting Nuclear Forces. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Obama administration has asked four countries to postpone a resolution at the United Nations calling for reducing the alert-level of nuclear weapons.

The intervention apparently is intended to avoid the Obama administration having to vote against the resolution before the important Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference in May 2010 — on an issue Barack Obama promised to support when he ran for president.

The resolution, which was last adopted by the U.N. General Assembly with overwhelming support on December 2, 2008, calls for “further practical steps to be taken to decrease the operational readiness of nuclear weapons systems, with a view to ensuring that all nuclear weapons are removed from high alert status.”

Obama’s De-Alerting Pledge

During the presidential election campaign, Barack Obama pledged that as president he would “work with Russia to take nuclear weapons off hair-trigger alert.” This pledge was part of the foreign policy agenda of the Obama for America campaign, and for several months after the election was part of the White House web site:

“The United States and Russia have thousands of nuclear weapons on hair-trigger alert. Barack Obama believes that we should take our nuclear weapons off hair-trigger alert – something that George W. Bush promised to do when he was campaigning for president in 2000. Maintaining this Cold War stance today is unnecessary and increases the risk of an accidental or unauthorized nuclear launch. As president, Obama will work with Russia to find common ground and bring significantly more weapons off hair-trigger alert.”

Apparently Russia has shown little interest in de-alerting, and the pledge has since disappeared from the White House web site and was not mentioned in President Obama’s speech in Prague in April this year.

The Nuclear Posture Review

The Obama administration is more than halfway through a Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) that is analyzing, among other issues, what alert level is appropriate for U.S. nuclear forces in the future.

Currently, virtually all of the 450 Minuteman III land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles are on alert with approximately 500 warheads. Another 96 Trident II sea-launched ballistic missiles with nearly 400 warheads are on alert onboard four of the nine-ten Ohio-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines that are at sea at any given time.

Why U.S. national security 20 years after the Cold War ended still depends on the ability to launch nearly 900 nuclear warheads with 12 minutes (actually only four minutes for the ICBMs) is one of the great mysteries the NPR has to answer.

|

| The EastWest Institute de-alerting report is worth reading. |

The long-range bombers were removed from nuclear alert in 1991 and – despite recent attempts to increase their readiness – will remain off alert with no detrimental impact on U.S. national security.

Reframing Nuclear De-Alert

The EastWest Institute has, with the support of the Swiss and New Zealand governments, just published a highly-recommendable study Reframing Nuclear De-Alert: Decreasing the Operational Readiness of U.S. and Russia Arsenals.

The study, which was briefed to the United Nations yesterday, does a good job of trying to elevate the de-alerting debate from whether or not nuclear alert should be called “hair-trigger alert” to actually considering practical steps for lowering the operational readiness of nuclear forces.

Whether the Obama administration’s request to postpone the U.N. resolution indicates that the NPR will recommend lowering the readiness of U.S. nuclear forces remains to be seen. But it will be truly disappointing if it does not.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Pentagon Misses Warhead Retirement Deadline

|

| Retirement of the W62 warhead, seen here at Warren Air Force Base, has been been delayed. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Pentagon has missed the deadline set by the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review for the retirement of the W62 nuclear warhead.

Retirement of the warhead, which arms a portion of the 450 U.S. Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles, was scheduled for completion in Fiscal Year 2009, which ended on September 30th.

But the Department of Defense has been unable to confirm the warhead has been retired, saying instead earlier today: “The retirement of the W62 is progressing toward completion.”

The 2001 Nuclear Posture Review decided that, “the W62 will be retired by the end of Fiscal Year 2009.” The schedule was later reaffirmed by government officials and budget documents. But the February 2009 NNSA budget for Fiscal Year 2010 did not report a retirement but a reduction in “W62 Stockpile Systems” – meaning the warhead was still in the Department of Defense stockpile, adding that a final annual assessment report and dismantlement activities will be accomplished in FY2010.

Offloading of the W62 from the Minuteman force has been underway for the past several years. First deployed in 1970, the W62 has a yield of 170 kilotons and is the oldest and least safe warhead in the U.S. stockpile. It is being replaced on the Minuteman III by the 310-kiloton W87 warhead previously deployed on the MX/Peacekeeper missile.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.