Testing the No-New-Nuclear-Weapons Pledge

|

| The Air Force is considering a replacement for the nuclear air-launched cruise missile. Will the NPR agree or adhere to Barack Obama’s no-new-nuclear-weapons pledge? |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen [updated March 18, 2010]

One of the important tests of Obama Administration’s nuclear nonproliferation policy will be whether the long-delayed Nuclear Posture Review will approve new nuclear weapons.

During his election campaign, Barack Obama promised not to build new nuclear weapons, a pledge that recently has been reiterated by the administration.

Yet the Air Force’s budget request for 2011 includes several projects that, if approved, would contradict the pledge.

The “No New” Pledge

During the presidential election campaign, Barack Obama pledge to “stop the development of new nuclear weapons” if elected president. The pledged lived on for the first few months after the election on the Obama administration’s White House foreign policy web page, but disappeared when the page was reorganized at the time of the Prague speech in April 2009.

Since the, the president has, to my knowledge, not repeated the pledge. But Under Secretary of State Ellen Tauscher echoed the election pledge last month when she explained that the Pentagon says it does “not need new nuclear weapons capabilities. They just want to be confident in what we have,” she said and declared: “We are not in the business of seeking new nuclear capabilities. They are not needed to preserve a strong, credible deterrent.”

New Nuclear Weapons

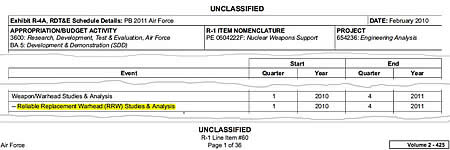

Yet “new” seems to be an elusive term. Even though Tauscher promised that the “RRW is dead and is not coming back,” the Air Force nuclear weapons support program includes “Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW) Studies & Analysis” in both 2010 and 2011. Perhaps she meant RRW as it was known rather than ruling out future replacement warheads. [Update March 18, 2010: The US Air Force now says the reference to RRW studies and analysis is an error and that the item mistakenly was left in the budget request from the previous year]

| More RRW Studies? |

|

| Despite a promise that the “RRW is dead and is not coming back,” the Air Force budget request includes RRW studies and analysis in both 2010 and 2011. Click for larger version. |

.

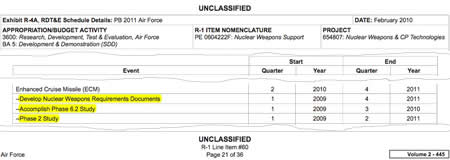

Another apparent contradictions with the administration’s no new nuclear weapons pledge is a new nuclear cruise missile to replace the current Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM) that expires in 2030. The new weapon is known as the Enhanced Cruise Missile (ECM), and development of nuclear weapons requirements documents are planned for 2010 and 2011, along with a Phase 6.2 Study, also known as a Feasibility Study and Option Down Select study. [Update March 18, 2010: The US Air Force now says the reference to the ECM is an error and that the item mistakenly was left in the budget request from the previous year. But the reference to the LRSO is not an error]

| A New Nuclear Cruise Missile? |

|

| The Air Force budget request includes what appears to be a replacement for the nuclear Air Launched Cruise Missile. Will the NPR approve? Click for larger version. |

.

The Enhanced Cruise Missile appears to be part of a program known as the Follow-On Long Range Stand-Off (LRSO) Vehicle to develop a replacement for the Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM).

The plan includes production of the Initial Capabilities Document (ICD) in early 2010, a Material Development Decision (MDD) in September 2010, and an Acquisition Decision in late 2011 or 2012. With that timeline, the NPR will have to make a decision.

New or Modified Warhead

One question is whether the new cruise missile will use a modified version of the existing W80-1 warhead currently deployed on the ALCM for B-52 delivery, or require development of a new warhead.

|

| A W80-1 warhead is mated with an ALCM. |

Until 2006, a life extension program (LEP) existed to extend the life of the W80-1. The LEP version was called W80-3. A parallel program to extend the W80-0 warhead would have produced the W80-2. But the Bush administration decided to “defer” the programs in pursuit of the RRW. That effort failed but the W80 LEP is still “archived,” according to the Air Force FY2011 budget request.

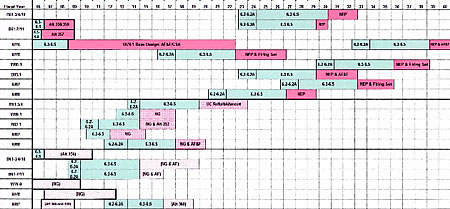

The remaining W80-1 warheads are scheduled to receive new neutron generators in 2015-2017, but a refurbishment of the nuclear explosive package is not planned until 2036-2039, according to the NNSA’s FY09 refurbishment planning schedule (no schedule exists yet for FY2010 or FY2011). No life-extension is planned for the W80-0, which will be retired.

| Warhead Refurbishment Plan? |

|

| The National Nuclear Security Administration’s nuclear warhead refurbishment plan does not include a formal life-extension program for the W80-1 warhead. An expensive program would be added if the NPR approves the Air Force’s cruise missile plan. Chart obtained under FOIA. Click for larger version. |

.

A decision to use a modified version of the existing W80-1 in the new cruise missile would involve reviving the $200 million per year W80-3 LEP program.

New or Just “New”

Nuclear weapons modernization programs risk triggering a contentious debate similar to the dispute over the RRW and whether Obama’s no-nuclear-weapons pledge can be trusted.

Does a new “weapon” refer to the warhead on the missile or the delivery vehicle itself or both? And how new must a weapon be to be considered “new” – does it require an entirely new design or can a modified design be considered a “new” weapon?

Government officials have to be crystal clear when they present the results of the NPR to make sure the administration’s nonproliferation policy doesn’t get stuck in the mud of misunderstandings and contradictions about what constitutes a “new” nuclear weapon. A lot is at stake.

Additional Information: Pentagon Eyes More Than $800 Million for New Nuclear Cruise Missile

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Jin SSBN Flashes its Tubes

|

| One of China’s two Jin-class SSBNs with two open missile tubes. Click for larger image. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

One of China’s two new Jin-class SSBNs was photographed with two of its 12 missile tubes open when it visited Xiaopingdao Naval Base in March 2009.

The Jins are being readied to carry the JL-2, a single-warhead regional sea-launched ballistic missile that was most recently test-launched in May 2008. The class may become operational soon and replace the old Xia from 1982.

Xiaopingdao Naval Base, which is where I identified the Jin-class for the first time in 2007, serves as an outfitting and testing facility for new submarines and used to be the homeport of the single Golf-class diesel submarine China used for many years as a test launch platform for its first ballistic missile.

Two or three Jin-class SSBN have been under construction, and it remains to be seen if China will build up to five as projected by U.S. intelligence. China’s nuclear submarines appear to be the noisiest nuclear submarines in the world and will probably be highly vulnerable at sea.

The U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence described in August 2009 that two of China’s SSBNs (probably one Jin and the Xia) were based at the Northern Fleet Base in Jianggezhuang, and the third boat (probably the second Jin) at the Southern Fleet Base on Hainan Island. I identified the Jin at Hainan in February 2008.

The Obama administration’s first version of The Military Power of the People’s Republic of China is expected within the next month or two.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Changing the Nuclear Posture: moving smartly without leaping

Release of the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) is delayed once again. Originally due late last year, in part so it could inform the on-going negotiations on the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty Follow-on (START-FO), after a couple of delays it was supposed to be released today, 1 March, but last week word got out that it will be coming out yet another 2-4 weeks later. Some reports are that the delay reflects deep divisions within the administration over the direction of the NPR. That means that there is really only one person left whose opinion matters and that is the president.

We can only hope that President Obama makes clear that he meant what he said in Prague and elsewhere. This NPR is crucial. If it is incremental, if it relegates a world free of nuclear weapons to an inspiring aspiration, then we are stuck with our current nuclear standoff for another generation. This is the time to decisively shift direction. But we should not be paralyzed by thinking that the only movement available is a giant leap into the unknown. We need to move decisively in the right direction, sure, but we can do that in steps. (more…)

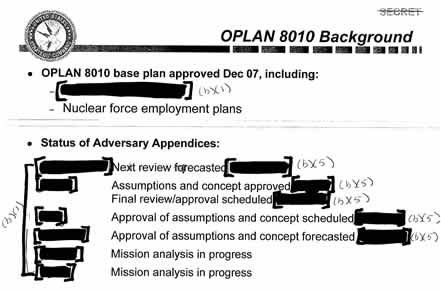

Obama and the Nuclear War Plan

|

| The current U.S. strategic war plan is directed against six adversaries. Guess who. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

While the completion of the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review continues to slide, FAS today published an issue paper on how a decision to reduce the role of nuclear weapons might influence the U.S. strategic war plan.

President Obama pledged in his Prague speech last year that he would “reduce the role of nuclear weapons” to “put an end to Cold War thinking,” and reaffirmed earlier this month that the “Nuclear Posture Review will reduce [the] role….”

How to reduce the role in a way that is seen as significant by the global nonproliferation community, visible to adversaries, and compatible with the president’s other pledge to “maintain a safe, secure and effective arsenal to deter any adversary…as long as these weapons exist” apparently is the subject of a heated debate within the administration.

|

| Click image to download report. |

The most persistent rumor is that the review might remove a requirement to plan nuclear strikes against chemical and biological weapons; reduce the mission to the core role of deterring use of other nuclear weapons. I recently described that the Quadrennial Defense Review stated that new regional deterrence architectures and non-nuclear capabilities “make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.”

A reduction of the mission to only deter nuclear use would roll back much of the expansion of nuclear doctrine that happened during the Clinton and Bush administrations. But it would not “put an end to Cold War thinking,” but to post-Cold War thinking.

To put an end to Cold War thinking, the reduced role would have to affect the core of the war plan that is directed against Russia and China.

The issue paper describes how the strategic war plan is structured, how it has evolved, and discusses options for reducing the mission and the war plan itself.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Posture Review to Reduce Regional Role of Nuclear Weapons

|

| The Quadrennial Deference Review forecasts reduction in regional role of nuclear weapons. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

A little-noticed section of the Quadrennial Defense Review recently published by the Pentagon suggests that that the Obama administration’s forthcoming Nuclear Posture Review will reduce the role of nuclear weapons in regional scenarios.

The apparent reduction coincides with a proposal by five NATO allies to withdraw the remaining U.S. tactical nuclear weapons from Europe.

Another casualty appears to be a decision to retire the nuclear-armed Tomahawk sea-launched land-attack cruise missile, despite the efforts of the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission.

New Regional Deterrence Architectures

Earlier this month President Barack Obama told the Global Zero Summit in Paris that the NPR “will reduce [the] role and number of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” The reduction in numbers will initially be achieved by the START follow-on treaty soon to be signed with Russia, but where the reduction in the role would occur has been unclear.

Yet the Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) published earlier this month strongly suggests that the reduction in the role will occur in the regional part of the nuclear posture:

“To reinforce U.S. commitments to our allies and partners, we will consult closely with them on new, tailored, regional deterrence architectures that combine our forward presence, relevant conventional capabilities (including missile defenses), and continued commitment to extend our nuclear deterrent. These regional architectures and new capabilities, as detailed in the Ballistic Missile Defense Review and the forthcoming Nuclear Posture Review, make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” (emphasis added)

There are two parts (with some overlap) to the regional mission: the role of nuclear weapons against regional adversaries (North Korea, Iran, and Syria); and the role of nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

Rumors have circulated for long that the administration will remove the requirement to plan nuclear strikes against chemical and biological weapons from the mission; to limit the role to deterring nuclear attacks. Doing so would remove Iran, Syria and others as nuclear targets unless they acquire nuclear weapons. A broader regional change could involve leaving regional deterrence against smaller regional adversaries (including North Korea) to non-nuclear forces and focus the nuclear mission on the large nuclear adversaries (Russia and China).

An immediate consequence of the new architecture appears to be a decision to retire the nuclear Tomahawk sea-launched land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N). According to a report by Kyodo News (see also report by Daily Yomiuri), Washington has informally told the Japanese government that it intends to retire the weapon. The 2009 Congressional Strategic Posture Commission report had recommended retaining the weapons, but neither the Pentagon nor the Japanese government apparently agreed.

| Nuclear Tomahawk To Be Retired |

|

| The Obama administration has informally told the Japanese government that the nuclear Tomahawk cruise missile will be retired. The retirement appears to be part of a new regional deterrence architecture that enables a reduction of the role of nuclear weapons. |

.

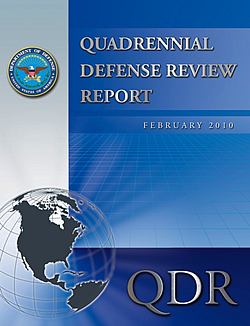

A Nuclear Withdrawal From Europe?

The other part of the regional mission concerns the deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe, where the U.S. Air Force currently deploys 150-200 nuclear bombs at six bases in five NATO countries. Some of the TLAM/Ns also are earmarked for support of NATO, but are stored on land in the United States. The weapons are the last remnant of the Cold War deployment of thousands of tactical nuclear weapons to deter a Soviet attack on Europe. Similar deployments in the Pacific ended two decades ago and pressure has been building for NATO to finally end the Cold War.

Three of the five NATO countries that currently host the U.S. nuclear bombs on their territories are expected to ask for the weapons to be withdrawn, according to a report by AFP.

A spokesperson for the Belgian Prime Minister said that Belgium, German, and the Netherlands, together with Norway and Luxemburg, in the coming weeks will formally propose within NATO that “that nuclear arms on European soil belonging to other NATO member states are removed.”

Presumably, some coordination with Washington has taken place. Otherwise, if the NPR does not recommend a withdrawal from Europe, the five countries’ initiative will from the outset be in conflict with the Obama administration’s nuclear policy, which NATO likely will follow.

The European initiative would help the Obama administration justify a decision to withdraw the weapons from Europe by demonstrating that key NATO allies no longer see a need for the deployment. Extended nuclear deterrence would continue, as the QDR language underscores, but with long-range strategic weapons as it is done in the Pacific.

Other than the forthcoming NPR, the political context for the European initiative is NATO’s ongoing review of its Strategic Concept, scheduled for completion in November. The Obama administration might not want to preempt that review, so an alternative could be that the NPR concludes that the U.S. sees no need for the continued deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe but leaves it up to NATO’s new Strategic Concept to make the formal decision. In that case, the initiative by the five NATO countries could serve to formally start that process within NATO. (see comments by U.S. NATO Ambassador Ivo Daalder)

Whether that means a complete withdrawal from Europe now, a decision to end the NATO strike portion (a controversial Cold War mission that assigns nuclear weapons for delivery by Belgian, Dutch, German, and Italian aircraft) and consolidating the remaining weapons at one or two U.S. bases in Europe, or something else remains to be seen. But a reduction rather than complete withdrawal would achieve little.

Heated Debate

The debate over the deployment in Europe is in full swing, recently triggered by the new German government’s decision to work for a withdrawal.

A paper by Franklin Miller, a former top-Pentagon official in charge of the deployment in Europe, and former NATO head George Robertson calling the German position dangerous was rejected as old-fashioned thinking on the New York Times’ opinion pages by Wolfgang Ischinger, Germany’s former foreign deputy foreign minister and chairman of the Munich Security Conference, and Ulrich Weisser, a former director of the policy planning staff of the German defense minister.

And suggestions by some supporters of continued deployment that Eastern European countries oppose withdrawal have suffered recently with Poland’s Prime Minister Radek Sikorski calling for the reduction and elimination of non-strategic nuclear weapons, and a report from the Polish Institute of International Affairs in March 2009 that appeared to question the need for the nuclear deployment.

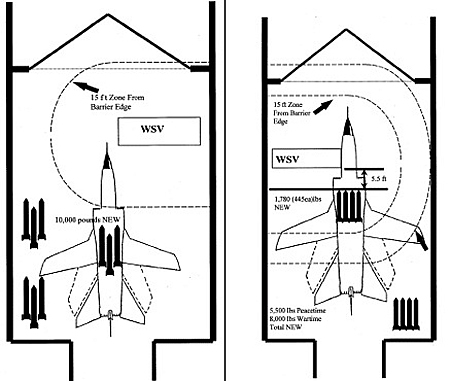

Status of U.S. Nuclear Deployment in Europe

The U.S. Air Force currently deploys an estimated 150-200 U.S. nuclear bombs in 87 aircraft shelters at six bases in five countries, a reduction from approximately 480 bombs in 2001. The breakdown by country looks like this:

|

| Click image to download larger pdf-version. |

.

Additional Background: History of U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Kleine Brogel Nukes: Not There, Over Here!

|

| The U.S. Air Force’s 701 Munitions Support Squadron at Kleine Brogel Air Base must protect and handle the nuclear weapons at the base. |

An astounding statement by a Belgian defense official has pointed an unexpected light on the apparent location of nuclear weapons at the Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium.

After a group of peace activists climbed the base fence and made their way deep into an area assumed to store nuclear weapons, Ingrid Baeck, a chief spokesperson for the Belgian Ministry of Defense, bluntly told Stars and Stripes: “I can assure you these people never, ever got anywhere near a sensitive area. They are talking nonsense….It was an empty bunker, a shelter,” she said and added: “When you get close to sensitive areas, then it’s another cup of tea.”

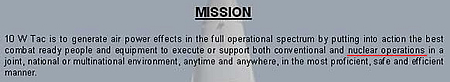

Baeck did not go so far as to explicitly confirm or deny if there were nuclear weapons on the base, but the Belgium Ministry of Defense’s mission statement for the 10th Tactical Wing clearly shows that it has a nuclear mission (see Figure 1).

| Figure 1: Belgian 10th Tactical Wing Mission |

|

| The Belgian Ministry of Defense’s mission statement for the 10th Tactical Wing (10 W Tac) at Kleine Brogel clearly lists a nuclear mission. Emphasis added. |

.

Shelter Searching

It is unclear whether Baeck as a spokesperson actually knows where the weapons are stored or if “sensitive area” only refers to the particular shelter the activists reached. But her statement that the activists “ever got anywhere near a sensitive area” inadvertently redirects the attention to the western area of the base.

Kleine Brogel has 26 Protective Aircraft Shelters (PAS) located in three clusters: Area 1 at the western part of the base with 11 shelters; Area 2 at the center of the base also with 11 shelters; and Area 3 at the eastern end of the base with four shelters (see Figure 2).

| Figure 2: Nuclear Weapons Storage Areas |

|

| Estimated locations for nuclear weapons at Kleine Brogel Air Base have changed over the years. Click image for large version. |

.

During the Cold War, nuclear weapons were stored in the Weapons Storage Area northeast of the base, while aircraft loaded with nuclear weapons stood alert in the shelters in Area 3.

Area 2 has long been the suspected nuclear weapons storage area, given its 11 shelters, pronounced fencing, and separation from the outer base perimeter. This is the area the activists managed to penetrate on January 31st.

Baeck’s statement appears to draw the attention to Area 1 at the western end of the base where 11 shelters are clustered. It also has an additional fence perimeter that appears to have been improved since 2006, but the gates were open on a satellite image dated April 8, 2007. Moreover, the area is close to the outer base fence, with the busy N748 highway only 225 feet (68 meters) from one shelter and another shelter only 134 feet (40 meters) from a residential neighborhood. Jeffrey L also has an interesting photo interpretation.

Whether the nuclear shelters necessarily have to be in one cluster inside the same perimeter is unknown, although safety and management issues seem to suggest so.

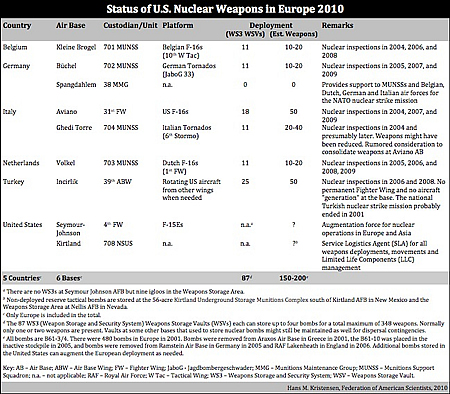

The Weapons Security and Storage System (WS3)

Only 11 of the 26 Protective Aircraft Shelters at Kleine Brogel are equipped with the Weapons Storage Security System (WS3), a nuclear weapons storage system unique to Europe. The system at Kleine Brogel was completed in 1992.

The mechanical part of the WS3 includes a Weapons Storage Vault (WSV), a reinforced concrete foundation and a steel structure recessed into the floor of the shelter. The vault platform can be elevated out of the concrete foundation by means of an elevator drive system to provide access to the weapons in two stages or levels, or can be lowered into the floor to provide protection and security for the weapons. The floor slab is approximately 16 inches (40 cm) thick. Sensors to detect intrusion attempts are embedded in the concrete vault body.

Each of the 11 vaults can store up to four B61 bombs, but normally contains only one or two for a total of 10-20 bombs currently at Kleine Brogel.

Location of the vault inside the shelter depends on the size of the shelter and the proximity of conventional weapons storage racks. Two layouts are in use (see Figure 3), and the vaults at Kleine Brogel are the smaller located at the front-left end of the shelter.

| Figure 3: Weapons Storage Vaul Locations |

|

| The location of the underground Weapons Storage Vault depends on the size of the aircraft shelter. Kleine Brogel shelters use the right-hand layout. |

.

The vaults are rarely visible on photos from outside the shelters, but in this unique photo (see Figure 4) taken at nearby Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands in 2009 the outline of the vault can be seen in the front-left corner (right in the picture) of the shelter.

| Figure 4: External View of Munitions Storage Vault |

|

| A vault cover is visible inside this shelter at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands. The picture of the specially painted F-16 (no. J-015) was taken during a pilot ceremony in 2009. Reprinted with permission. Original photo at Touchdown Aviation. |

.

The vault can be elevated in two stages, halfway to provide access to the top rack, or fully to provide access to the lower rack as well. An example of halfway elevation is the photo below showing the command of U.S. Air Forces in Europe, General Roger Brady, receiving a briefing next to a vault at Volkel Air Base in June 2008 (see Figure 5) (he also visited Kleine Brogel). The visits happened shortly after the Blue Ribbon Review report concluded that “most sites” storing nuclear weapons in Europe did not meet DOD security standards.

| Figure 5: Halfway Elevation of Weapons Storage Vault |

|

| This picture, taken inside a shelter at Volkel Air Base, shows Gen. Grady receiving a briefing from a member of the 703rd MUNSS. The vault is halfway raised showing one B61 bomb, with the lower bomb rack hidden below the floor level. |

.

If fully elevated the vault appears as on the image below (see Figure 6). The base name is unknown, but given the location of the vault it appears to be inside a large shelter at a U.S. base, possibly Aviano Air Base in Italy or Ramstein Air Base in Germany (all B61s were removed from Ramstein in 2005).

| Figure 6: Full Elevation of Weapons Storage Vault |

|

| Full elevation of the Weapons Storage Vault inside what appears to be an aircraft shelter at Aviano Air Base or Ramstein Air Base. |

.

What is Security?

Kleine Brogel base commander Col. Fred Vansina insisted that the penetration of the base by the activists did not constitute a security incident: “Our installations are very well secured, in different ways,” there was “no single security incident, whatever the activists claim.”

A nuclear base is a sensitive area and unauthorized personnel meandering around deep inside its inner perimeters is a security incident, but Vansina’s definition appears to require an unauthorized and dangerous approach of a nuclear facility. Both he and Baeck have great confidence in the WS3 and the security forces’ ability to protect the weapons under all circumstances.

I agree that it would be very difficult for anyone to steal or destroy the weapons under normal circumstances when they’re stored underground. But it is the abnormal circumstances that concern me; weapons are occasionally brought up from the vault, serviced, and moved (see Figure 7). Overconfidence is dangerous because incidents and accidents have a nasty habit of happening in ways that were not anticipated. And that requires us to weigh the risks against the necessity of the deployment, a necessity I have an increasingly hard time to see.

| Figure 7: Halfway Elevation of Weapons Storage Vault |

|

| The safety of the underground Weapons Storage Vault no longer applies when nuclear bombs in Europe are brought up for maintenance or transport. A 1997 Air Force study even found a risk of lightning causing a nuclear detonation. |

.

Status of Nuclear Weapons in Europe

The 10-20 weapons at Kleine Brogel are part of a stockpile of an estimated 150-200 U.S. nuclear bombs scattered in 87 vaults at six bases in five countries, a reduction from approximately 480 bombs in 2001. My current estimate looks like this (see Figure 8):

| Figure 8: |

|

| Click image to download larger pdf-version. |

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

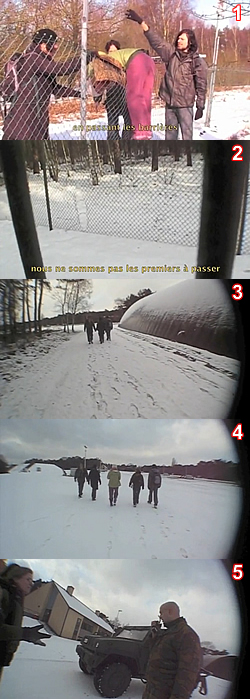

US Nuclear Weapons Site in Europe Breached

|

| Peace activists walked one kilometer onto a US nuclear weapons storage site in Belgium for more than one hour before security personnel reacted. Click image for larger version. (For an update to this map, go here) |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A group of people last week managed to penetrate deep onto Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium where the U.S. Air Force currently deploys 10-20 nuclear bombs. (For an update to this blog, go here)

Fortunately, the people were not terrorists but peace activists from a group known as Vredesactie, who managed to climb the outer base fence, walk cross the runway, breach a double-fenced security perimeter, and walk into the very center of the air base alongside the aircraft shelters where the nuclear bombs are thought to be stored in underground vaults.

A Nuclear Cake Walk |

|

| The activists climbed the outer base fence (1), breached the inner double-fence (2), tagged a nuclear aircraft shelter (3), walked across the tarmac (4), before being arrested (5) after more than one hour inside the base. The numbers on the images correspond to the location of the numbers on the map above. |

The activists penetrated nearly one kilometer onto the base over more than an hour before a single armed security guard appeared and asked what they were doing. Soon more arrived to arrest the activists, who later described: “The military blindfolded for hours, they forced us to kneel in the snow, arms outstretched at 90° and threatened us if we intend to return to the base in the months to come.”

The activists videotaped their entire walk across the base. The security personnel confiscated cameras, but the activists removed the memory card first and smuggled it out of the base. Ahem…

In June 2008, I disclosed how an internal Air Force investigation had concluded that most nuclear weapons sites in Europe did not meet US security requirements. The Dutch government denied there was a problem, and an investigative team later sent by the US congress concluded that the security was fine.

They might have to go back and check again.

The nuclear bombs at Kleine Brogel are part of a stockpile of about 200 nuclear weapons left in Europe after the Cold War ended. Whereas nuclear weapons have otherwise been withdrawn to the United States and consolidated, the bombs in Europe are scattered across 62 aircraft shelters at six bases in five European countries. The 130-person US 701st Munitions Support Squadron (MUNSS) is based at Kleine Brogel to protect and service the nuclear bombs and facilities.

They might have to go back to training.

The activists will likely be charged with trespassing a military base but they should actually get a medal for having exposed security problems at Kleine Brogel. And this follows two years of the Air Force creating new nuclear command structures and beefing up inspections and training to improve nuclear proficiency following the embarrassing incident at Minot Air Force Base in 2007. Despite that, the activists not only made their way deep into the nuclear base but also discovered that the double-fence around the nuclear storage area had a hole in it! “We’re not the first,” one of the activists said.

NATO needs to get over its obsession with nuclear weapons and move out of the Cold War and the Obama administration’s upcoming Nuclear Posture Review needs to bring those weapons home before the wrong people try to do what the peace activists did.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Flight Testing a Centrifuge

On 13 January, Ivanka Barzashka and I gave a briefing at the AAAS on our work regarding Iran’s uranium enrichment capacity. Joshua Pollack also gave a briefing, which he has described. Joshua’s analysis is thorough and interesting but I think I would use a different distinction than the “actual” and “nominal” values that he defines.

Pollack shows how the estimates of the capability of Iran’s centrifuge, the IR-1, have declined over time. That is intriguing but I worry that it makes the calculations that Ivanka and I and others have performed using data reported from International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) on-site inspections seem like the next step in a series of similar estimates. They are not. There are two very different types of approaches being taken here. Here I present an analogy that I think might make the differences clear. (more…)

Japanese Government Rejects TLAM/N Claim

|

| Katsuya Okada and Hillary Clinton met in September 2009. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Japanese government has officially rejected claims made by some that Japan is opposed to the United States retiring the nuclear Tomahawk Land-Attack Missile (TLAM/N).

The final report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States from May 2009 emphasized the importance of maintaining the TLAM/N for extended deterrence in Asia by referring to private conversations with specifically “one particularly important ally” (read: Japan) that “would be very concerned by TLAM/N retirement.”

In a letter sent to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on December 24, 2009, Japanese Foreign Minister Katsuya Okada explicitly says that the Japanese government has expressed no such views.

The Japanese Foreign Minister’s letter explicitly refers to the Commission: “It was reported in some sections of the Japanese media that, during the production of the report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States released in May this year, Japanese officials of the responsible diplomatic section lobbied your government not to reduce the number of its nuclear weapons, or, more specifically, opposed the retirement of the United States Tomahawk Land Attack Missile – Nuclear (TLAM/N) and requested that the United States maintain a Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP).

I don’t know who made a reference to RNEP (the Commission didn’t; perhaps it was a reference to earth-penetration capabilities in general rather than RNEP per ce), but Okada’s rejection of the TLAM/N claim is clear:

“[A]lthough the discussions were held under the previous Cabinet, it is my understanding that, in the course of exchanges between our countries, including the deliberations of the above mentioned Commission, the Japanese Government has expressed no view concerning whether or not your government should possess particular [weapons] systems such as TLAM/N and RNEP.” (my emphasis)

Okada’s statement suggests that he has checked the government’s files. It also matches the statement made by Admiral Timothy J. Keating, the former Commander of U.S. Pacific Command, in July 2009, that he was “unaware of specific Japanese interests in the” TLAM/N.

If the TLAM/N were retired, Okada says, Japan would of course like to be informed about how this would affect extended deterrence and how it could be supplemented. I hope “supplemented” means by other existing nuclear and non-nuclear means, not by new nuclear weapon system.

It seem so, because Okada writes that he favors nuclear disarmament, and he also expresses interest in the proposal made recently by the International Commission on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Nuclear Disarmament (ICNND) – and many others – that the role of nuclear weapons be restricted to deterrence of the use of nuclear weapons. That is important for the Japanese government to say because one of the current missions for U.S. nuclear weapons involve North Korean chemical and biological attacks on Japan. Apparently, closer consultations between the United States and Japan on extended deterrence issues would be a good idea.

It seems more and more that the TLAM/N claim resulted from a shady collusion between a few U.S. and Japanese officials (some current and some former) who sought to present private views as more than that in an effort to put brakes on the Obama administration’s disarmament agenda.

Hopefully the pending Nuclear Posture Review will not be led astray.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Russian Nuclear Forces 2010

|

| Russia’s Teykovo 4 missile garrison northeast of Moscow is undergoing major upgrades for new SS-27 mobile nuclear missiles. Click image for large illustration of the changes. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The latest overview of Russia’s nuclear forces produced by Robert Norris from NRDC and myself is now available on the website of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

We estimate that Russia currently (January 2010) deploys approximately 4,600 nuclear weapons, down from roughly 4,800 a year ago. The arsenal includes some 2,600 strategic warheads and about 2,000 warheads for nonstrategic forces. Another 7,300 weapons are thought to be in reserve or awaiting dismantlement for a total inventory of approximately 12,000 nuclear warheads. We estimate the weapons are stored at 48 permanent storage sites.

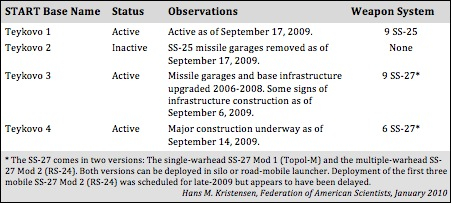

SS-27 Modernization at Teykovo

One of the interesting developments is Teykovo northeast of Moscow where four missile garrisons are in the process of upgrading from the SS-25 road-mobile intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) to the newer SS-27. One base still has SS-25s while the other three are in various stages of upgrading.

The SS-27 comes in two versions: single-warhead SS-27 Mod 1 (Topol-M) and the multiple-warhead SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24). The two versions can be deployed in silos or on mobile launchers. All Teykovo missiles are mobile. Fifteen SS-27 Mod 1s have already been deployed, and the Russian military stated repeatedly in 2009 that the first SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24) would become operational at Teykovo by the end of the year, which we wrote in our overview. That apparently did not happen after all and the system is now expected to become operational sometime in early-2010.

Commercial satellite images taken over the past five years clearly show major construction work at the garrisons. The newest images from late-2009 show that two garrisons appear to be active, one is undergoing major upgrades (see image above), and one was inactive as of September 2009.

| Teykovo ICBM Garrison Status 2009 |

|

| Click table for larger version. |

.

Teykovo 1 (56°48’33.11″N, 40°10’15.89″E) appears to be active with the SS-25. Nine launchers (one regiment) are deployed. A satellite photo from September 17, 2009, shows no construction. The base might be converted to SS-27 in the future.

Teykovo 2 (56°55’0.42″N, 40°18’31.39″E) no longer has operational SS-25s with all missile garages missing in a satellite image from September 17, 2009. No construction has begun but the base might be converted to SS-27 in the future.

Teykovo 3 (56°55’56.98″N, 40°32’38.47″E) appears to have almost completed its upgrade. Major construction occurred in 2006-2008 and some remaining construction is visible in a satellite image from September 6, 2009. Nine SS-27s are operational.

Teykovo 4 (56°42’15.10″N, 40°26’25.29″E) appears to be in the process of upgrading to SS-27, with six of eventually nine launchers apparently operational. Deployment of the first three SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24) was scheduled for late-2009 but appears to have been delayed to later this year.

Modernization and Fear Mongering

Russian nuclear modernization is a hot topic in Washington with some trying to block new nuclear arms reductions by claiming that the United States is falling behind. That is fortunately far from the truth (see here and here) and the upgrade at Teykovo has been long in the coming and slow.

Like the United States, Russia is reducing its nuclear weapons but also modernizing its remaining forces. How the Kremlin plans to reconcile this modernization with the pledge to pursue nuclear disarmament that president Dmitry Medvedev made with his U.S. counterpart in 2009 will be interesting to see in the years ahead.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Doctrine and Missing the Point.

The government’s much anticipated Nuclear Posture Review, originally scheduled for release in the late fall, then last month, then early February is now due out the first of March. The report is, no doubt, coalescing into final form and a few recent newspaper articles, in particular articles in Boston Globe and Los Angeles Times, have hinted at what it will contain.

Before discussing the possible content of the review, does yet another release date delay mean anything? I take the delay of the release as the only good sign that I have seen coming out of the process. Reading the news, going to meetings where government officials involved in the process give periodic updates, and knowing something of the main players who are actually writing the review, what jumps out most vividly to me is that no one seems to share President Obama’s vision. And I mean the word vision to have all the implied definition it can carry. The people in charge may say some of the right words, but I have not yet discerned any sense of the emotional investment that should be part of a vision for transforming the world’s nuclear security environment, of how to make the world different, of how to escape old thinking. As I understand the president, his vision is truly transformative. That is why he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. His appointees who are developing the Nuclear Posture Review, at least the ones I know anything about, are incredibly smart and knowledgeable, but they are also careful, cautious, and, I suspect, incrementalists who might understand intellectually what the president is saying but don’t feel it (and, in many cases, fundamentally don’t really agree with it). A transformative vision not driven by passion will die. As far as I can see (and, I admit, I am not the least bit connected so perhaps I simply cannot see very far) the only person in the administration working on the review who really feels the president’s vision is the president. Much of what I hear from appointees in the administration has, to me at least, the feel of “what the president really means is…” If the cause of the delay is that yet more time is needed to find compromise among centers of power, reform is in trouble because we will see a nuclear posture statement that is what it is today neatened up around the edges. But if the delay is because the president is not getting the visionary document he demands, delay might be the only hopeful sign we are getting.

Now, onto the possible content of the review: The main question to be addressed by the review is what the nuclear doctrine and policy of the United States ought to be. This has sparked a secondary debate about just how specific any declaration of policy should be and the value of declaratory policy at all.

Some hints coming out of the administration suggest that the new review may explicitly state that the sole purpose of nuclear weapons be specifically limited to countering enemy nuclear weapons, what we and others have called a “minimal deterrence” doctrine. Currently, the United States claims that chemical and biological weapons may merit nuclear attack and that could go away with the current review.

Most reports leaking out from the review participants hint that the NPR almost certainly will not include a declaration that the United States will not be the first to use nuclear weapons. The current U.S. policy is to intentionally maintain ambiguity about how and when we might use nuclear weapons, to keep the bad guys guessing. The new review could keep that basic idea and still be a little less ambiguous around the edges.

Some question the value of having a declaratory policy at all. For example, if a no-first-use policy can be reversed by a phone call from the president, what does it actually mean? As Jeffrey Lewis argues, if having a declared policy causes an intense drilling down into what-ifs, it can increase suspicion and do actual harm. (Although the example Lewis offers raises questions about whether China should have a no-first-use policy and is not particularly relevant to whether the U.S. should.)

A bigger problem with any declaratory policy is figuring out what it actually means. Do we agree on what “no first use” means? I think it means that we will not be the first to explode a nuclear weapon. But, for example, in a recent article in Foreign Affairs, Lieber and Press argue that the United States could be justified in using nuclear weapons if an adversary first “introduced” nuclear weapons into a conflict, where “introduce” might be to explode one, but might also include putting them on higher alert, moving them, or simply implying their relevance to the contest. So a nuclear war-planner and I could agree on a no-first-use policy and have differing, almost opposite, views of what that meant.

But if statements of doctrine don’t mean anything, then why the big deal? Why would the nuclear establishment invest any political capital fighting for or against them? While it is true that doctrinal statements are always taken with a huge grain of salt by other nations (just as the United States applies a steep discount to statements coming from others), they do make a difference in the domestic debate. In the previous administration, the Department of Energy went to the Congress with a request to build a new facility to build the plutonium cores or “pits” for 250 new nuclear warheads every year. This made no sense whatsoever; it was completely out of synch with our own plans for future nuclear forces and Congress voted it down because the DOE was not remotely able to justify its request. The DOE proposal went down to 125, then 80, and some current variations on the basic proposal are for a dozen or so, which actually makes some sense.

So doctrine and declaratory policy are important in very concrete ways when they can affect force structure decisions, including the numbers and types of weapons we have, their capabilities, and how they are deployed. Moreover, these are the sorts of changes that other nations will see and pay attention to.

The uncertainty of the link between words and weapons is what causes wariness on every side of the debate. Foreign governments might not believe our declarations but such declarations might form the basis for changes in the U.S. nuclear force structure, with all the implications for budgets and personnel, weapons, bases, and jobs back home. That is why the nuclear establishment is resisting. On the other hand, those who desire fundamental and profound change could be completely hoodwinked by nice sounding words that allow the status quo to coast ahead on its own momentum.

The danger I see is that, if discussion is so tightly focused on what we say, then too little attention will be given to what we do. If we take our declarations seriously, they should have profound effects on the nuclear posture but I can imagine big changes in the review with little real physical change actually resulting. For example, if we take seriously a no-first-use policy, our deployment of forces could be radically different. Reentry vehicles could be stored separated from their missiles, missiles in silos could be made visibly unable to launch quickly, for example, by piling boulders over the silo doors. Much of the ambiguity in any verbal statement of doctrine is squeezed out when we discuss the concrete questions of what the forces look like. The nuclear war-planner and I might have effectively opposite definitions of “no first use” but we would agree entirely on what it means to piles boulders on our ICBM silo doors.

What I would hope to see come out of the NPR is not simply a statement of no first use but a plan for, for example, taking our nuclear weapons off alert. We will certainly hear that nuclear weapons are for deterrence, perhaps that they are only for deterrence. But that has become utterly meaningless because the definition of deterrence has been warped to the point that it can now be defined as whatever it is that nuclear weapons do. Indeed, nuclear weapons are often simply called our “deterrent.” Michele Flournoy, the current Undersecretary of Defense in charge of the NPR process, wrote a report while at CSIS describing how U.S. nuclear weapons should be able, among other things, to execute a disarming first strike against central Soviet nuclear forces, the better to “deter.” When a word has that much flexibility, I don’t care whether it gets included in the posture statement or not but I do care whether we mount our nuclear weapons on fast flying ballistic missiles or on slow, air-breathing cruise missiles.

If we take seriously some of the statements that might come out of the review, then we can start to imagine radically different force structures. For example, if the requirement for nuclear preemption is removed and the number of nuclear targets is substantially reduced, then new ways to base nuclear weapons become feasible. We could, for example, store missiles in tunnels dug deep inside a mountain where the missiles would be both invulnerable and impossible to launch quickly. We could invite a Russian to live in a Winebago on top of the mountain to confirm to his own nuclear commanders that we were not preparing our missiles for launch.

These are things the world can see. Indeed, if we have no interest in a first strike capability, we have every incentive to invite the world to come in and see for themselves. These are the types of changes that need to occur in the U.S. nuclear force structure and, if they do, debate about the words in the review is less important.

You Don’t Have to Be a Mouse to Be Wary of Mousetraps

Happy New Year. We at FAS are a serious, hard-working lot but I thought I would start the year with a blog somewhat less Earth-shattering than we normally do. The following is the result of some research made possible by free time over the holidays.

It is with a combination of despair and delight that we discover that what we thought to be true is not. I guess it is all part of learning. Thus with mousetraps and ping-pong balls.

I often get science questions from film-makers. Most recently from a production group doing a piece on nuclear energy and nuclear weapons. I was explaining chain reactions and mentioned the famous demonstration using mousetraps and ping-pong balls. If you are a techie sort reading this blog, you have probably seen one demonstration or another; from my childhood, I can remember one featured in Disney’s 1957 Our Friend the Atom. (The cloud chamber demo is also very cool, and check out the extremely trendy lab coat the female lab tech is wearing; the 50’s were, indeed, the good old days).

After this discussion with the film team, I got online and started looking for other examples of the demonstration. I expected to find some but not many. I was particularly curious to find how large was the biggest layout that had ever been done. Doing this demonstration is a lot of work after all, setting all those mousetraps and carefully placing the ping-pong balls on top. And one mistake and…start all over. (And what do you do afterwards with hundreds of mousetraps and ping-pong balls?)

In my search, I discovered a few very slow motion videos that show that the demonstration is entirely misleading. The mousetraps-with-ping-pong-balls is a terrible analog for a nuclear chain reaction.

The basic idea is simple: In a nuclear fission chain reaction, one neutron splits an atomic nucleus, or induces the fission of the nucleus. (I think the latter, while fancy, is actually a better term. “Splitting” the nucleus suggests to me shooting a bowling ball with a rifle bullet and breaking it in two. That isn’t really what happens. The neutron may be fast or it may be very slowly passing by when it falls into the nucleus and finds an unmated neutron. The binding energy of those neutrons releases so much energy into the nucleus that it comes apart. The kinetic energy of the neutron can be negligible compared to the binding energy released. That is why slow moving neutrons are more likely than fast neutrons to cause the fission of a susceptible nucleus: the kinetic energy of the neutron is unneeded and the slower neutrons are easier to catch.) The nucleus splits into two big chunks, which will become the nuclei of new, lighter atoms, but in the process it releases a couple of neutrons. These neutrons go on to cause additional fissions, which produces more neutrons, which produce more fissions, and so on. If the reaction is allowed to go as fast as possible, the number of neutrons and the rate of fission increase exponentially and very rapidly and an explosion results. In a nuclear reactor, the rate of reaction is carefully controlled to keep a steady rate of fission.

So the macroscopic model is the array of mousetraps with each trap topped by a pair of ping-pong balls. One ball is dropped onto the array and trips a trap. It is the energy of the trap, not the energy of the ball that flings the other two balls up in the air. These come down, setting off two more traps, releasing four balls. These four balls set off four traps releasing eight balls, and so forth and, in a few seconds, ping-pong balls are flying everywhere and all the traps have been tripped.

Or so we were lead to believe. (We can’t even believe Walt Disney?) But some of the videos are slow motion and bear careful study. This one in particular (be sure to have your sound turned on) shows that most of the traps are tripped, not by balls, but by flying traps. Note that balls often hit traps and knock the balls free without tripping the traps. This is the equivalent of the (n,3n) nuclear reaction, which would be very rare because it requires breaking apart a pair of fermions, and fermions just love their pairs. A much more common nuclear reaction is (n,2n), which is equivalent to having one ball come in and knock just one ball off. With nuclei, this is not common enough to sustain a chain reaction.

I have not done a careful counting but my uncareful counting shows that most of the ball impacts occur without setting traps off. That is OK, it is the equivalent of a collision in which no reaction takes place, which is, at least for some energies, the most likely thing to happen when a neutron hits a nucleus. In the video above, keep your eye on one trap about a third of the way up from the bottom and a quarter of the way in from the right hand side. It is hit by several balls during the whole chain reaction and at the end remains unsprung.

Of course, eventually a ball will set off a trap but then something interesting happens: the trap goes flying. (If we really wanted to demonstrate fission, the trap would have to split in two, but we will overlook that.) And it is the big, heavy trap that sets off neighboring traps when it hits the ground. The analog would be that the fission products, not the neutrons, induce further fissions, say, a big heavy cesium nucleus runs into the nearby uranium nucleus and caused it to split. Of course, that never happens.

Another interesting case is here; at time 2:05, note right along the center, a column of traps snaps in sequence when clearly the balls go flying straight up and do not have time to set off the next trap. What is happening is that the hammer (that is the bar that actually whacks the mouse on the back of his neck; I had to look it up) swings from one side to the other and, through conservation of momentum, the base of the traps scoots along in the opposite direction. The trap then whacks the next trap in line, setting it off, and that hits the next, and so on. The video shows clearly that the ping-pong balls have nothing to do with the process in that particular case. (Before you get all huffy about conservation of momentum, remember that, because these demonstrations are taking place in a gravitational field with the traps sitting on the floor, there is an asymmetry, for example, when the hammer is going up, it pushes the trap against the floor and doesn’t move it but when the hammer is on the way down, it can lift the trap up and scoot it in the opposite direction.)

Obviously, some balls do trip some traps; I am just saying that that is not the dominant process, it is traps tripping traps. To see a nice example of traps tripping traps, watch the first video above, right in the center, at 3:08, and see one trap land on another, be actually trapped by it, and then the two go off in a nice 2001: A Space Odyssey-style weightless waltz. I guess this is the equivalent of a fusion that might be seen in a heavy ion accelerator.

So, what would be a good analog? If you meet the following criteria:

(1) You want to demonstrate several aspects of neutron-induced nuclear fission chain reactions,

(2) You have several hundred mousetraps and twice as many ping-pong balls handy, and

(3) You have WAY too much time on your hands,

then you may want to construct the following demonstrations. I know I am not going to be doing this. (And don’t forget to video tape everything and post it on YouTube and let me know.)

First, and most important, the mousetraps have to be glued down. I think it might work to get small pieces of plywood and glue traps to them in sets of 20 or so. Then the number of traps can be varied (see below) and the big plywood base isn’t going to move. You can see one example of fixed traps here, but note the perfect reflector (see below).

But it gets worse. Note from the video that the balls hitting the traps routinely knock the resting balls free without setting off the trap. This is equivalent to the (n,3n) reaction cited above, which is quite rare. Even the (n,2n) reaction is not common enough to sustain a chain reaction. To make our model faithful, we need to stop this reaction. Perhaps a small spot of glue could be used to fasten each ball to the trap. The glue would have to be strong enough to hold when hit by another ping-pong ball, but the bond would have to be weak enough to allow the balls to go flying when the trap was tripped. I think it would just require some experimenting with different types of glue. If the hammer is steel, then perhaps a small magnet poked inside each ping-pong ball would be enough to hold it on and stop the (n,2n) reactions. (I tested a Victor mouse trap. The hammer looks to be copper but must be just copper coating over steel because the hammer is attracted by a magnet.) The effects of having lots of magnetic ping-pong balls flying around might be interesting.

Note that in all the demonstrations, the traps are enclosed by walls (often mirrors to fool you into thinking there are more traps than there actually are). This is equivalent to having a perfect neutron reflector, which doesn’t exist. The height of the walls could be adjusted to show the effect of having some balls escape.

Ironically, the more energetic balls are good analogs for the slowest neutrons. By flying high, they come down with the greatest force and are more likely to “induce a fission,” that is, set off a trap, just as slow neutrons have a greater likelihood, described by a larger “cross-section,” of inducing a fission. In addition, by flying high, they take a long time to come back down just as slow neutrons take longer to get from one nucleus to another. So just lowering the walls of the cage has the effect of letting the slow neutrons out and keeping the fast neutrons in. Hmmm, that doesn’t seem right. Maybe we need to put holes in the sides rather than simply lower the walls or just make a picket fence, with slats and gaps between.

With leaky walls that allow some balls to escape, we will discover the mousetrap equivalent of a critical mass. Below some number, mousetraps within a lower wall, the will not be able to sustain a chain reaction because each reaction will result in two new balls being released but if, on average, more than one ball escapes, then the reaction will die out. That is, it will not “go critical.” But by increasing the number of traps, just increasing the floor space covered by traps, we reduce the surface to volume ratio or, since this is really a two dimensional model, the circumference to area ratio, and the chain reaction should be sustaining because the probability is increased that any given ping-pong ball will induce another reaction before jumping over the wall. This is how a gun-assembled nuclear bomb works, taking two masses of fissionable material and bringing them together quickly to form a mass large enough to sustain a chain reaction.

We could also show how criticality depends not just on the number of traps but on their density. If we placed the traps, not side-by-side, but with some separation, then some of the balls would land between the traps and not set another trap off. The ball would bounce and might bounce over the wall, being lost. If balls bounced out frequently enough, the reaction would not be sustaining. But the same number of traps, simply packed closer, could sustain a reaction. (This is how an implosion bomb works, the amount of mass is constant but the compression increases the density.)

We could also demonstrate the difference between critical masses of different nuclei. The critical mass of plutonium-239 is much less than uranium-235. Why? Two big reasons: (1) When a plutonium nucleus splits, it emits slightly more neutrons on average than when a uranium nucleus does. So we could load the traps with different numbers of ping-pong balls, some with two, some with only one. A lower average number would represent uranium and a higher average would represent plutonium. We would find that we need fewer traps loaded with more balls to sustain a chain reaction. (2) A plutonium nucleus is more likely to be split by a neutron than a uranium nucleus is. The part of the trap where you put the cheese is called the catch (I had to look that up, too). Most traps have just a little metal tab for the cheese (I find peanut butter actually works better) but some traps have a larger plastic tab that the mouse can step on. Such a tab would be equivalent to a larger neutron cross section. We would find that fewer large-catch traps would be needed to sustain a reaction than small-catch traps, just as less plutonium is needed compared to uranium.

So there is some hope for the mousetrap analog but it would be a lot more work. I suspect we will continue to see the simple mousetrap demonstrations and I will just pretend not to have all the above objections because I do think it is very cool.

If you really want to impress me, you could do all of the above using rat traps and billiard balls. (But stand back.)

I hope our readers are not devastated by having a cherished childhood image crushed but we are, after all, the Federation of American Scientists and sworn to the relentless pursuit of truth.

So much for the holiday break. Back to saving the world.