India’s SSBN Shows Itself

|

| A new satellite image appears to show part of India’s new SSBN partly concealed at the Visakhapatnam naval base on the Indian east coast (17°42’38.06″N, 83°16’4.90″E). |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

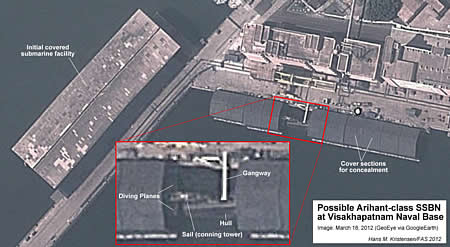

Could it be? It is not entirely clear, but a new satellite image might be showing part of India’s first nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine, the Arihant.

The image, taken by GeoEye’s satellite on March 18, 2012, and made available on Google Earth, shows what appears to be the conning tower (or sail) of a submarine in a gap of covers intended to conceal it deep inside the Visakhapatnam (Vizag) Naval Base on the Indian east coast.

The image appears to show a gangway leading from the pier with service buildings and a large crane to the submarine hull just behind the conning tower. The outlines of what appear to be two horizontal diving planes extending from either side of the conning tower can also be seen on the grainy image.

The Arihant was launched in 2009 from the shipyard on the other side of the harbor and moved under an initial cover. An image released by the Indian government in 2010 appears to show the submarine inside the initial cover.

|

| The Indian government published this image in 2010, apparently showing the Arihant inside the initial concealment building. |

.

The new cover, made up of what appears to be 13-meter floating modules that can be assembled to fit the length of the submarine, similarly to what Russia is using at its submarine shipyard in Severodvinsk, first appeared in 2010. Images from 2011 show the modules in various configurations but without the submarine inside.

The movement of the Arihant from the initial cover building to the module covers next to the service facilities and large crane indicates that the submarine has entered a new phase of fitting out. The initial cover building appeared empty in April 2012 when the Indian Navy show-cased its new Russia-supplied Akula-class nuclear-powered attack submarine: the Chakra.

It is thought that the Arihant is equipped with less than a dozen launch tubes behind the conning tower for short/medium-range nuclear-armed ballistic missiles. Before it can become fully operational, however, the Arihant will have to undergo extensive refitting and sea-trials that may last through 2013. It is expected that India might be building several SSBNs.

Like the other nuclear weapon states, India continues to modernize its nuclear forces, despite pledges to work for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See also: Indian nuclear forces, 2012.

In Warming US-NZ Relations, Outdated Nuclear Policy Remains Unnecessary Irritant

|

| U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta meets with New Zealand Defense Minister Jonathan Coleman, in a first step to normalize relations between the two countries nearly 30 years after the U.S. punished New Zealand for its ban on nuclear weapons. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Hat tip to the Obama administration for doing the right and honorable thing: breaking with outdated Reagan administration policy and sending Defense Secretary Leon Panetta to New Zealand and ease restrictions on New Zealand naval visits to U.S. military bases.

The move shows that Washington after nearly 30 years of punishing the small South Pacific nation for its ban against nuclear weapons may finally have come to its senses and decided to end the vendetta in the interest of more important issues.

The New Zealand defense minister made it quite clear that the move does not mean a change to New Zealand’s policy of denying nuclear warships access to its harbors. “New Zealand has made it very clear that the policy remains unchanged and will remain unchanged.”

Whether (or how soon) the move will result in a resumption of U.S. naval visits to New Zealand remains to be seen. The U.S. Navy still has two policies that would appear to prevent this. One is a “one-fleet” policy that holds that if any U.S. ships are restricted from an area, it will refrain from sending any ships there. The other is the Neither Confirm Nor Deny Policy (NCND), which prohibits disclosing if a warship carries nuclear weapons or not, a leftover from the Cold War when stuff like that was important.

These policies leave an irritant in place that doesn’t need to be there. It seems that both countries can makes modifications to their policies to allow normal military relations to resume.

Cold War Policy in Need of Change

Panetta’s visit to New Zealand is the first by a U.S. defense secretary in 30 years since the gong ho nuclear policy of the Reagan administration threw New Zealand out of the Australia-New Zealand-US (ANZUS) alliance for refusing to accept visits by nuclear-armed warships to its ports. The treatment of New Zealand was intended as a warning to countries not to dare enforce their non-nuclear policies. As former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Leslie Gelb diplomatically put it in the New York Times at the time: “Unless we hold our allies’ feet to the fire over ship visits and nuclear deployments, one will run away and then the next.”

At the core of the dispute is the so-called Neither Confirm Nor Deny Policy (NCND), according to which the U.S. will not reveal – directly or indirectly – whether nuclear weapons are present on a warship, an aircraft, or on a base. The policy emerged in the 1950s as a way to counter anti-nuclear and left wing demonstrations in Europe during port visits. Later it was re-coined as a way to protect ships against terrorist attacks and to complicate Soviet military planning. Spin aside, the central objective was always to ensure unfettered access for U.S. warships to foreign ports – no matter the nuclear policy of the host country. (For a chronology of the NCND policy, see: The Neither Confirm Nor Deny Policy: Nuclear Diplomacy at Work).

During the Cold War, U.S. warships bristled with non-strategic nuclear weapons. Bombs, anti-submarine rockets, air-defense missiles, land-attack cruise missiles, depth bombs and torpedoes were continuously at sea onboard aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, frigates, supply ships and attack submarines. Every single day some of them sailed into foreign ports around the world. The deployment war part of a global posture against the Soviet Union, which also deployed non-strategic nuclear weapons on its fleet (Britain and France had similar postures).

The NCND was a brilliant diplomatic arrangement. The host country could have whatever nuclear policy it wanted and the United States could continue to visit its ports with nuclear-armed warships. The only problem with the NCND was that it put allied governments with non-nuclear policies in an unreasonable dilemma: one, reject the visit or ask the United States to deny that the ship carried nuclear weapons; or, two, turn a blind eye and accept that nuclear weapons come in on warships once in a while.

That dilemma is the dirty little secret of the NCND: It required not just that the United States was ambiguous about the weapons loadout, but also that the host country accepted ambiguity about the armament. For the host country to accept ambiguity was, of course, incompatible with a policy that prohibited nuclear weapons on its territory.

New Zealand was the first allied country that refused to accept that ambiguity. It did so in 1984 by adopting a law that prohibited access for nuclear-armed and nuclear-propelled vessels. The law did not demand that the United States confirm or deny whether there were nuclear weapons on the ships (that is a widespread misperception); it only required the New Zealand government in its own right to make a determination and announce its decision. But such an announcement was incompatible with the NCND, which required the host country to keep quiet about what it knew.

|

| The USS Buchanan (DDG-14) arrives in Sydney, Australia, in March 1985 after it was barred from visiting New Zealand. |

When the U.S. wanted to send a warship to New Zealand in the spring of 1985, it could have sent a warship that was not nuclear-capable (in fact, the News Zealand government asked the U.S. to do so, but it refused). But that would not have fully tested New Zealand’s adherence to the NCND. So the Reagan administration decided to send the guided missile destroyer USS Buchannan (DDG-14), which was equipped to carry nuclear ASROC missiles. This visit was to be followed by several other ships, some of which most likely carried nuclear weapons.

The New Zealand government turned down the request and the Reagan administration retaliated by throwing New Zealand out of the ANZUS alliance, curtailing intelligence sharing, and prohibiting New Zealand warships from visiting U.S. military and Cost Guard facilities in the region. In effect, the Reagan administration chose to sacrifice an ally in a part of the world where the military implications were limited to prevent the anti-nuclear “allergy” from spreading to other more vital parts of the world.

The strategy failed. In 1988, the nuclear port visits issue triggered an election in Denmark, and in 1990 the Swedish governing party decided to enforce Sweden’s ban against nuclear weapons on its territory after a study determined that U.S. warships routinely carried nuclear weapons into Swedish ports despite the ban.

Instead of a tool for protecting nuclear warships and ensuring allied security, the NCND policy became a lightening rod for political controversy and soured relations with U.S. allies all over the world. Whenever a nuclear-capable warship sailed into a foreign port on a “goodwill visit,” the thorny issue of whether it carried nuclear weapons and the host government being seen as turning a blind eye to violations of its own non-nuclear policy overshadowed the goodwill the U.S. and the host government were trying to demonstrate.

Today the policy continues even though it is hopelessly outdated and counterproductive. All non-strategic nuclear weapons were removed from U.S. surface ships and attack submarines by the first Bush administration in 1992 – effectively rendering the nuclear port visit issue moot. Moreover, the Clinton administration decided in 1994 to denuclearize all U.S. surface ships. The only remaining non-strategic naval nuclear weapon – the Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N) – has been stored on land since 1992 and is now being scrapped. (Russia has also offloaded its naval non-strategic nuclear weapons and Britain has completely eliminated its inventory.)

Restoration of Normal Relations is Possible

There is nothing that prevents restoration of normal U.S.-New Zealand military relations. Yet even though the non-strategic nuclear weapons have been offloaded and the U.S. surface fleet denuclearized, there are still Cold War warriors inside the bureaucracies who argue that it is necessary to maintain ambiguity about what U.S. warships carry and that no warship should sail where others are rejected.

Likewise, given that the U.S. surface fleet has been denuclearized and the last non-strategic naval nuclear weapon is being retired, there is no problem in the New Zealand government ascertaining – even publicly – that visiting U.S. warships do not carry nuclear weapons.

The policies that required nuclear ambiguity for warship visits to New Zealand are unnecessary and counterproductive and should be abolished. Hopefully they will not prevail for long. It is only a matter of time before U.S. warships begin visiting New Zealand again and Panetta must order the navy to stop pretending ambiguity where there is none: U.S. warships no longer carry nuclear weapons.

In the meantime, the U.S. embassy in Wellington might want to update its fact sheet on New Zealand-U.S. relations, which doesn’t seem to have caught up with Panetta’s visit:

“New Zealand’s legislation prohibiting visits of nuclear-powered ships continues to preclude a bilateral security alliance with the U.S. The legislation enjoys broad public and political support in New Zealand. The United States would welcome New Zealand’s reassessment of its legislation to permit that country’s return to full ANZUS cooperation.” (Emphasis added).

I think that ship has sailed.

STRATCOM Commander Rejects High Estimates for Chinese Nuclear Arsenal

|

| STRATCOM Commander estimates that China has “several hundred” nuclear warheads. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The commander of U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) has rejected claims that China’s nuclear arsenal is much larger than commonly believed.

“I do not believe that China has hundreds or thousands more nuclear weapons than what the intelligence community has been saying, […] that the Chinese arsenal is in the range of several hundred” nuclear warheads.

General Kehler’s statement was made in an interview with a group of journalists during the Deterrence Symposium held in Omaha in early August (the transcript is not yet public, but was made available to me).

General Kehler’s statement comes at an important time because much higher estimates recently have created a lot of news media attention and are threatening to become “facts” on the Internet. A Georgetown University briefing last year hypothesized that the Chinese arsenal might include “as many as 3,000 nuclear warheads,” and General Victor Yesin, a former commander of Russia’s Strategic Rocket Forces, recently published an article on the Russian web site vpk-news in which he estimates that the Chinese nuclear weapons arsenal includes 1,600-1,800 nuclear warheads.

In contrast, Robert S. Norris and I have published estimates of the Chinese nuclear weapons inventory for years, and we currently set the arsenal at approximately 240 warheads. That estimate – based in part on statements from the U.S. intelligence community, fissile material production estimates, and our assessment of the composition of the Chinese nuclear arsenal – obviously comes with a lot of uncertainly and assumptions, but we’re pleased to see that it appears to fit with the “several hundred” warheads mentioned by General Kehler.

Like the other nuclear weapon states, China is modernizing its nuclear arsenal, but it is the only one of the five original nuclear powers (P-5) that appears to be increasing the size of its warhead inventory. That increase is modest and appears to be slower than the U.S. intelligence community projected a decade ago. Those who see an interest in exaggerating China’s nuclear developments thrive on secrecy, so it is important that China – and others who know – provide some basic information about trends and developments to avoid exaggerated estimates. The reality is bad enough as it is.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Talks at U.S. Strategic Command and University of California San Diego

By Hans M. Kristensen

It’s been a busy week with two talks; the first to the U.S. Strategic Command’s Deterrence Symposium on August 9, and the second to the Public Policy and Nuclear Threats “boot camp” workshop at the University of California San Diego on August 10.

STRATCOM asked me to talk on the question: Will advanced conventional capabilities undermine or enhance deterrence. My panel included former STRATCOM Commander General James Cartwright, former SAC CINC General Larry Welch, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Global Strategic Affairs Madelyn Creedon. The panel was chaired by Rear Admiral John Gower of the U.K. Ministry of Defense. My speech is reproduced below. The video of Panel #7 is available later at the STRATCOM web site.

UCSD asked me to speak on New Directions for U.S. Nuclear Strategy. My panel included Daryl Press, who is Associate Professor in the Department of Government at Dartmouth College, and Anne Harrington, a Postdoctoral Fellow at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. A copy of my briefing slides is available here.

Speech: USSTRATCOM Deterrence Symposium 2012

Hans M. Kristensen

Federation of American Scientists

August 9, 2012

The question for this panel – Will advanced conventional capabilities undermine or enhance deterrence? – is a difficult question to answer for several reasons. First, “advanced conventional capabilities” is a very broad definition that can include everything that’s better than what we had last year. Second, deterrence is a subjective condition that doesn’t come in one shape or form but depends on actors and scenarios.

So at the outset, I’ll say: Whether advanced conventional capabilities will undermine or enhance deterrence depends on what kinds of adversary we seek to deter, with what, in what scenario, and for what objective.

Unfortunately, “deterrence” is one of the most overused and abused terms. It is still widely associated with nuclear weapons, which are often called “the deterrent force” or “the strategic deterrent,” or the SLBMs, which are referred to as “the sea-based deterrent.” National leaders have been busy after the end of the Cold War reminding us that deterrence is not just nuclear but a much wider host of capabilities and scenarios.

For purpose of this talk, I will focus on advanced conventional weapons such as Prompt Global Strike (PGS), how they might effect deterrence, how they are different from nuclear weapons, whether they can be used as strategic deterrents – perhaps even replacing nuclear weapons?

Currently, much of the public debate on advanced conventional capabilities has focused on speed: that very quick strikes are needed to knock out targets in rogue states or non-state actors armed with weapons of mass destruction. Part of that perception is rooted in the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review and its promotion of a New Triad with a seamless string of Global Strike capabilities ranging from nuclear, to non-nuclear, to non-kinetic effects.

This led to the Global Strike mission assigned to STRATCOM in 2003, at first a designated prompt Global Strike plan known as CONPLAN 8022, but later an integrated plan known as OPLAN 8010-08: Strategic Deterrence and Global Strike, which is currently in effect. The name reflects the dual mission of providing deterrence and, if that fails, Global Strike (or counterforce war fighting).

Compared with the old SIOP, the new plan includes “more flexible options to assure allies, and dissuade, deter, and if necessary, defeat adversaries in a wider range of contingencies.” So despite the challenges of tailoring deterrence to today’s world, it would seem that out strategic war plan has already been tailored to a considerable extent.

For the purpose of deterrence, despite significant advances in conventional weapons, nuclear weapons are still in a completely separate category because of their immensely destructive capability and will remain so for the foreseeable future.

But for war fighting, the Global Strike mission appears to accept that advanced conventional weapons can serve some missions that previously were only available for nuclear weapons. I have heard knowledgeable people say that up to 30 percent of the target base potentially could be covered with PGS weapons. But for all the talk of the urgency and importance of this mission, the weapons have been slow to emerge.

But what strikes me about the quest for PGS weapons is that it appears to be motivated less by deterrence and more by an expectation that deterrence will fail, and that new capabilities are therefore needed to destroy time-critical targets without having to resort to nuclear weapons.

Adversaries and allies alike have all seen the United State after the Cold War repeatedly being willing to use its ever-improving conventional forces in scenarios ranging from brief and limited punitive strikes to massive use of force over extensive periods of time to decisively defeat even large adversaries. In all of those cases, deterrence obviously failed despite our overwhelming capabilities; otherwise it wouldn’t have been necessary to strike.

PGS weapons would add to the toolbox and an adversary would obviously have to work around the capability. But it is much harder to predict whether – or to what extent – that would deter the adversary from taking action more or better than current capabilities would.

In the public debate the mission is almost entirely focused on regional and non-state adversary scenarios. Planners spend a lot of time trying to get inside the heads of these adversaries to understand what they value so we can figure out what to hold at risk to deter them. But if they’re already set on taking hostile action and know that they would be turned into rubble, why would PGS matter for deterrence?

Regional adversaries already bury their time-critical assets. Just look at North Korea where everything seems to live underground. Why has Iran focused its ballistic missile posture on mobile launchers? It’s a lot cheaper and simpler to build silos. China is no different; it’s hard to find a high-priority base that doesn’t include underground storage and their entire mobile missile modernization program is a reaction to someone holding their silos better at risk with more capable weapons.

All of these adversaries are already trying to work around our targeting capabilities. So why do we think that hitting them a little faster or a little better would strengthen deterrence? It seems more likely that PGS would push them even further toward more prompt launch capabilities. More trigger-happy postures could in fact weaken deterrence and increase the risk of mistaken, inadvertent, or even deliberate escalation. Keir Lieber made a similar argument yesterday.

What if the mission includes holding Chinese ASAT launchers a risk? China’s demonstration of an ASAT capability appears to have triggered a requirement for a quick-strike conventional capability to protect our eyes and ears in the sky.

Targeting ASAT missiles on DF-21 launchers is only a hairbreadth away from targeting other road-mobile launchers, whether for conventional DF-21C medium-range ballistic missiles, DF-21D anti-ship ballistic missiles, or even nuclear DF-31A missiles.

And how about using unmanned aerial vehicles with Hellfire missiles to hunt down Chinese mobile launchers?

Chinese planners would obviously have to assume that strikes would come quickly, that it could be preemptive, and that the risk to their nuclear launchers were increasing. In fact, they would have to conclude that a strike against their nuclear deterrent could come before the conflict had escalated to nuclear use.

Then suddenly the deterrence question changes dramatically. Add to that that some of the enablers for making PGS possible would require improvements to ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance) and C3 (Command, Control, Communication) systems that would probably also significantly improve the capability of nuclear forces. Russia and China will probably detect these improvements and compensate for them in their own nuclear planning.

Add to that an advanced ballistic missile defense system that could take out some of the surviving weapons, and we could end up significantly exacerbating a budding and counterproductive nuclear competition with Russia and China. Whether we agree or not, Russia is already making this argument in Europe and China has warned against it.

The point here is not that we should simply give in and capitulate to Russian and Chinese concerns. The point is that we better think carefully about these side-effects before rushing to acquire more advanced conventional capabilities for what in any case is argued to be a very limited niche mission against small adversaries that won’t be able to provide an existential threat. And these are very expensive systems. So they better be essential and not just good to have.

In summary, in some limited scenarios, such as escalation, advanced conventional capabilities might enhance deterrence by providing senior leaders with additional non-nuclear options for signaling or striking. But it is hard to predict, to say the least. In other scenarios they may do exactly the opposite and weaken deterrence by triggering use-it-or-loose-it postures and deepen nuclear competition.

So to answer the panel question of whether advanced conventional capabilities will undermine or enhance deterrence, I’d say the answer is: probably yes.

For additional background on the Global Strike mission, see: Hans M. Kristensen, Global Strike: A Chronology of the Pentagon’s New Offensive Strike Plan, FAS, March 2006.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

B61-12: NNSA’s Gold-Plated Nuclear Bomb Project

Escalating cost estimates for the B61 Life- Extension Program threaten to make the new B61-12 bomb the most expensive ever.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The disclosure during yesterday’s Senate Appropriations Subcommittee hearing that the cost of the B61 Life Extension Program (LEP) is significantly greater that even the most recent cost overruns calls into question the ability of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) to manage the program and should call into question the B61 LEP itself.

If these cost overruns were in the private sector, heads would roll and the program would probably be canceled.

At the hearing yesterday, Senator Dianne Feinstein revealed that NNSA recently told her that the $4 billion cost estimate they provided in the FY2011 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan was too low and that they would need $4 billion more to complete the program. Two months ago I reported that the cost had increased to $6 billion.

NNSA’s new cost estimate is already being challenged, this time by the Pentagon’s Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) office, which only a few days ago increased the estimate by another $2 billion to a whopping $10 billion.

But get this: the already too high B61 LEP cost estimate does not include other pricy elements of the B61 modernization program. In addition to the LEP itself comes a new guided tail kit assembly that the Air Force is developing to increase the accuracy of the B61. The cost estimate for that tail kit has recently increased by 50 percent from $800 million to $1.2 billion.

Add to that the cost of equipping the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter with the capability to carry the new weapons, recently estimated at around $340 million. If the LEP and tail kit increases mentioned above are any indication, however, then the cost of equipping the F-35 with nuclear capability is also likely to increase.

The escalating costs may eventually make the B61 LEP the most expensive nuclear weapons program (per warhead unit) in the U.S. arsenal. Already the projected B61 LEP cost far exceeds the cost of the W76 LEP, which probably involves three times as many warheads as will produced by the B61 LEP. As Nick Roth points out, the new $10 billion estimate is equivalent to two-thirds of what NNSA planned to spend on life extending all the other warhead types in the US arsenal over the next twenty years!

The precise number of B61-12 planned is still a secret. My take currently is around 400. If so, that would mean each B61-12 bomb would cost $28 million (including cost of tail kit).

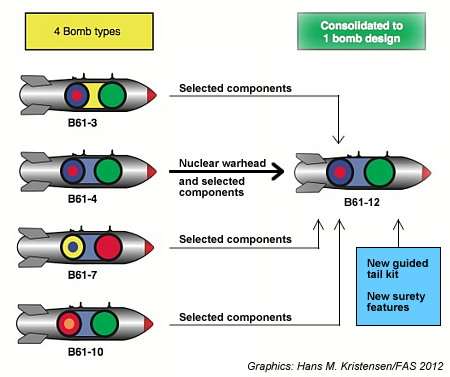

Because of the way the B61 LEP has been presented, many have the impression that the program will life-extend all four versions of the B61. In reality, only one of the four versions will be life-extended: the B61-4. It may cannibalize components from the other three (B61-3/7/10), but the heart of the new B61-12 is the B61-4 nuclear explosive package. Instead of the simple chart that STRATCOM has been circulating, the following chart more accurately illustrates the process:

Rather than a B61 life-extension program that consolidates four bombs into one, the B61 LEP should more accurately be described as a life-extension of the B61-4 that incorporates selected non-nuclear components from three other B61 versions that will be retired with new surety features and a new guided tail kit assembly.

Implications and Recommendations.

The fact that the B61-12 will use the B61-4 nuclear explosive package obviously limits the number of B61-12s that can be built to the number of B61-4 that were originally produced. That number is about 660. But most of those have been retired and only about 200 are thought to be left in the DOD stockpile. If B61-12 production is to exceed 200, then it would have to also use warheads from retired B61-4s. Given that the B61-12 will not be carried on the B-52 bomber, that B-2 bombers are probably not allocated a maximum load of weapons (they also carry others), and that the stockpile in Europe is likely to decrease within the next decade, it seems reasonable to assume a B61-12 stockpile of around 400 weapons. But the number is secret – not because it matters to national security but because it is nuclear.

The escalating cost of the B61 LEP adds to NNSA’s abysmal record of underestimating costs of nuclear weapons programs. It follows enormous budget overruns of the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement – Nuclear Facility (CMRR-NF) at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, and the Uranium Processing Facility (UPF) at the Y-12 National Security Complex at Oak Ridge in Tennessee.

As mentioned above, if these cost overruns happened in the private sector, heads would roll and the program would probably be canceled.

Apart from poor planning, the B61 LEP cost escalation is probably also fueled by planners that appear to be drunk on promises of increased nuclear funding and political commitments to nuclear modernization. The result is an overly ambitious program that instead of doing basic life-extension of existing designs is trying to add exotic features and components to the weapon that was originally tested. And the planned B61-12 is not even the most ambitious version the planners had asked for (they were not allowed to add multi-point safety and optical firing sets), which would have been even more expensive.

If poor planning is not the reason, then NNSA must be working under the assumption that costs should be underestimated when seeking initial program approval from Congress because the taxpayers will have to pay for the cost increase later on anyway. To her credit, Senator Feinstein is pushing for greater program control and told Aviation Week that the cost escalation will trigger additional congressional scrutiny. “We have to find a way to stop this from happening. …We’ve asked that we receive monthly reports, that one person be put in charge. … The purpose of that is to make people solve problems quickly, before they are left and they just continue to grow.”

The B61 LEP is not the only or necessarily most complex LEP on the horizon. NNSA and DOD are already planning the W78 LEP and envision building a “common” warhead that can be used on both ICBMs and SLBMs. Such a warhead is not currently in the stockpile. Although the design is still being worked out, it could combine W78 and W88 features and use a plutonium pit from a third warhead – the W87. If you’re worried about B61 LEP costs, just wait for the W78 LEP! Is Congress prepared to authorize $10 billion-plus per exotic LEP versus more basic LEPs?

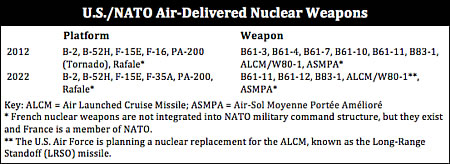

But apart from money, the escalating B61 LEP costs must also raise questions about the importance of the mission. While the strategic mission on the B-2 strategic bomber is probably not in doubt, the non-strategic mission certainly should be. Under current plans, the B61-12 will be fitted onto four tactical aircraft – F-15E Strike Eagle, F-16 Falcon, F-35A Lightning and PA-200 Tornado. There are no important or urgent threats that require the United States to equip all these tactical aircraft with the new bomb. But the modernization will increase the military capability of NATO’s nuclear posture, not exactly in sync with the pledges from the White House and NATO to reduce the role of nuclear weapons and not increase military capabilities during LEPs.

And the few NATO officials that have either misunderstood their security requirements or been lobbied by nuclear cold warriors to support continued deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe need to be debriefed – or asked to pay their share. That would certainly end the deployment quickly.

Whatever the best way forward, the U.S. should phase out its remaining non-strategic nuclear weapons, delay and redesign the B61 LEP, and focus its resources on maintaining the strategic nuclear weapons and conventional forces that are actually needed for U.S. and allied security in the foreseeable future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Nuclear Notebook: Indian Nuclear Forces, 2012

|

| The Indian government says its first nuclear ballistic missile submarine – the Arihant – will be “inducted” in mid-2013, a term normally meaning delivered to the armed forces. Several boats are thought to be under construction. Image: Government of India |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris

Our latest Nuclear Notebook has been published by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. We estimate that India currently has 80-100 nuclear warheads for its emerging Triad of air-, land-, and sea-based nuclear-capable delivery vehicles.

The latest test launch of a nuclear-capable ballistic missile occurred yesterday when an Agni I missile was launched by the Strategic Forces Command from a road-mobile launcher at the missile test launch center on Wheeler Island on India’s east coast in what the Indian government described as a “training exercise to ensure preparedness.”

|

| India’s east coast missile test launch center has been expanded with a second launch pad since 2003. Click image for larger version. |

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Event: Conference on Using Satellite Imagery to Monitor Nuclear Forces and Proliferators

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Earlier today we convened an exciting conference on use of commercials satellite imagery and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to monitor nuclear forces and proliferators around the world. I was fortunate to have two brilliant users of this technology with me on the panel:

- Tamara Patton, a Graduate Research Assistant at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, who described her pioneering work to use freeware to creating 3D images of uranium enrichment facilities and plutonium production reactors in Pakistan and North Korea. Her briefing is available here.

- Matthew McKinzie, a Senior Scientists with the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Nuclear Program and Lands and Wildlife Program, who has spearheaded non-governmental use of GIS technology since commercial satellite imagery first became widely available. His presentation is available here.

- My presentation focused on using satellite imagery and Freedom of Information Act requests to monitor Chinese and Russian nuclear force developments, an effort that is becoming more important as the United States is decreasing its release of information about those countries. My briefing slides are here.

In all of the work profiled by these presentations, the analysts relied on the unique Google Earth and the generous contribution of high-resolution satellite imagery by DigitalGlobe and GeoEye.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Sanctions and Nonproliferation in North Korea and Iran

The nuclear programs of North Korea and Iran have been, for many years, two of the most pressing and intractable security challenges facing the United States and the international community. While frequently lumped together as “rogue states,” the two countries have vastly different social, economic, and political systems, and the history and status of their nuclear and long-range missile programs differ in several critical aspects.

The international responses to Iranian and North Korean proliferation bear many similarities, particularly in the use of economic sanctions as a central tool of policy. Daniel Wertz, Program Officer at the National Committee on North Korea, and Dr. Ali Vaez, former Director of the Iran Project at the Federation of American Scientists, offer a comparative analysis of U.S. policy toward Iran and North Korea in a FAS issue.

Second Batch of New START Data Released

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. State Department today released the full (unclassified) aggregate data for U.S. strategic nuclear forces as counted under the New START treaty. The data shows only very modest reductions of deployed strategic nuclear weapons over the past six months.

The full U.S. aggregate data follows the joint and much more limited overall U.S. and Russian aggregate numbers released in March 2012. Under the previous START treaty, the United States used to make Russian data available, but accepted Russia’s demand during the New START negotiations to no longer release their data.

The joint aggregate data and the full U.S. aggregate data are released at different times and not all information is made reality available on the Internet. Therefore, a full compilation of the data is made available here.

Overall U.S. Posture

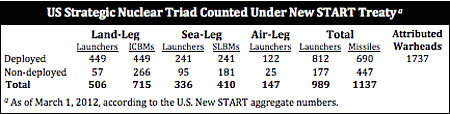

The New START data attributes 1,737 warheads to 812 deployed ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers as of March 1, 2012. This is a reduction of 53 deployed warheads and 10 deployed delivery vehicles compared with the previous data set from September 2011.

A large number of non-deployed missiles and launchers that could be deployed are not attributed warheads.

The data shows that the United States will have to eliminate 289 launchers over the next six years to be in compliance with the treaty limit of 700 deployed and non-deployed launchers by 2018. Fifty-six of these will come from reducing the number of launch tubes per SSBN from 24 to 20, roughly 80 from stripping B-52Gs and nearly half of the B-52Hs of their nuclear capability, possibly retiring 50 ICBMs, and destroying about 100 old ICBM silos.

The released data does not contain a breakdown of how the 1,737 deployed warheads are distributed across the three legs of the Triad. But because the bomber number is now disclosed and each bomber counts as one warhead, and because between 450 and 500 warheads remain on the ICBMs, it appears that the deployed SLBMs carried 1,112 to 1,165 warheads, or about two-thirds of the total number of warheads counted by New START.

Just to remind readers: the New START numbers do not represent the total number of nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal – only about a third. The total military stockpile is just under 5,000 warheads, with several thousand additional retired (but still intact) warheads awaiting dismantlement. For an overview, see this article.

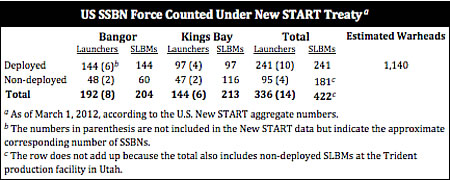

Ballistic Missile Submarines

The New START data shows that the United States as of March 1, 2012, had 241 Trident II SLBMs onboard its SSBN fleet. That is a reduction of eight SLBMs compared with the New START data from September 2011, but it doesn’t reflect an actual reduction in missiles on deployable submarines but a fluctuation in the number of missiles onboard SSBNs during loadout. Each SSBN has 24 missile tubes for a maximum loadout of 288 missiles, but at the time of the New START count two SSBNs were empty and two only partially loaded. With an estimated 1,140 warheads on the SLBMs, that translates to an average of 4-5 warheads per missile.

It is widely assumed that 12 out of 14 SSBNs normally are deployed, but two sets of aggregate New START data both indicate that the force ready for deployment at any given time may be closer to 10. This ratio can fluctuate significantly and in average 64 percent (8-9) of the SSBNs are at sea with roughly 920 warheads. Up to five of those subs are on alert with 120 missiles carrying an estimated 540 warheads – enough to obliterate every major city on the face of the earth.

Of the eight SSBNs based at Bangor (Kitsap) Submarine Base in Washington, the New START data indicates that two were out of commission on March 11, 2012: one had empty missile tubes – possibly because it was in dry dock – and another was only partially loaded – possibly because it was in the middle of a missile exchange when the count occurred. This means that six SSBNs at the base were loaded with Trident II D5 missiles carrying some 650 warheads at the time of the New START count.

For the six SSBNs based at Kings Bay Submarine Base in Georgia, the New START data shows that 97 missiles were deployed on March 1, 2012. That number is enough to load four SSBNs, with a fifth boat partially loaded. The 96 Trident II SLBMs on four SSBNs carried an estimated 430 warheads.

The New START data indicates that the U.S. Navy has not yet begun to reduce the number of missile tubes on each SSBN. The number will be reduced from 24 to 20 before the New START enters into effect in 2018.

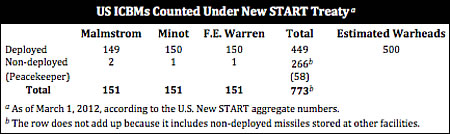

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles

The New START data shows that the United States deployed 449 Minuteman III ICBMs as of March 1, 2012. That is one more than on September 1, 2011. Most were at the three launch bases, but a significant number were in storage at maintenance and storage facilities in Utah. That included 58 MX Peacekeeper ICBMs retired in 2003-2005 but which have not been destroyed.

The New START data does not show how many warheads were loaded on the 449 deployed ICBMs, but the number is thought to be nearly 500. The 2010 NPR decided to “de-MIRV” the ICBM force, an unfortunately choice of words because the force will be downloaded to one warhead per missile, but retain the capability to re-MIRV if necessary. Downloading might have begun, but the status is unclear.

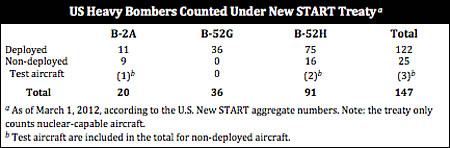

Heavy Bombers

The New START data shows that the U.S. Air Force possessed 147 B-2 and B-52 bombers as of March 1, 2012. Of these, 122 were counted as deployed, a reduction of three compared with September 2011.

Unfortunately the bomber data is misleading because it counts 36 retired B-52G bombers stored at Davis Monthan AFB in Arizona as “deployed” at Minot AFB in North Dakota. The miscount is the result of a counting rule in the treaty, which says that bombers can only be deployed at certain bases. As a result, the 36 retired B-52Gs are listed in the treaty as deployed at Minot AFB – even though there are no B-52Gs at that base. According to Air Force Global Strike Command, “There are no B-52Gs at Minot AFB, N.D…In accordance with accounting requirements, we have them assigned to Minot and as visiting David Monthan.” The actual number of heavy bombers should more accurately be listed as 86 B-2A and B-52H, with another 61 non-deployed (including the 36 at Davis Monthan AFB.

All of these bombers carry equipment that makes them accountable under New START, but only a portion of them are actually involved in the nuclear mission. Of the 20 B-2s and 91 B-52s, 18 and 76, respectively, are nuclear-capable, although only about 60 of those are thought to be nuclear tasked at any given time. None of the aircraft are loaded with nuclear weapons under normal circumstances but are attributed a fake count under New START of only one nuclear weapon per aircraft even though each B-2 and B-52s can carry up to 16 and 20 nuclear weapons, respectively. Roughly 1,000 nuclear bombs and cruise missiles are in storage for use by these bombers. Stripping excess B-52Hs and the remaining B-52Gs of their nuclear equipment will be necessary to get down to 60 counted nuclear bombers by 2018.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The New START data released by the State Department continues the decision made last year to release the full U.S. unclassified aggregate numbers, an important policy that benefits nuclear transparency and counters misunderstandings and rumors. In parallel with the data comes a busy treaty implementation effort and inspection schedule that reassures the United States and Russia that each side is abiding by the terms of the treaty. Now we need Russia to follow the U.S. example and also release its full unclassified data under New START.

The latest data set shows that the U.S. reduction of its deployed strategic nuclear warheads over the past six months has been modest: 53 warheads. The reduction is so modest that it might not reflect a cut as much as a fluctuation in the number of deployed weapons at any given time due to maintenance of delivery systems. While there have been some reductions of non-deployed and retired weapon systems, there is no indication from the New START data that the United States has yet begun to reduce its deployed strategic nuclear weapons.

Those reductions are scheduled to come, however, over the next five years as the New START treaty limits of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads and 700 deployed strategic delivery vehicles are to be met in February 2018. Despite the high cost of maintaining unnecessary weapon systems, 18 months after the New START treaty entered into force the Pentagon does not seem to be in a hurry to meet the treaty limits.

Download the full New START data here.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

NATO’s Nuclear Groundhog Day?

|

| At the Chicago Summit NATO will once again reaffirm nuclear status quo in Europe |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Does NATO have a hard time waking up from its nuclear past? It would seem so.

Similar to the movie Groundhog Day where a reporter played by Bill Murray wakes up to relive the same day over and over again, the NATO alliance is about to reaffirm – once again – nuclear status quo in Europe.

The reaffirmation will come on 20-21 May when 28 countries participating in the NATO Summit in Chicago are expected to approve a study that concludes that the alliance’s existing nuclear force posture “currently meets the criteria for an effective deterrence and defense posture.” [Update May 20, 2011: Turns out I was right. Here is the official document.]

In other words, NATO will not order a reduction of its nuclear arsenal but reaffirm a deployment of nearly 200 U.S. non-strategic nuclear bombs in Europe that were left behind by arms reductions two decades ago.

Visions Apart?

Although no one expected NATO to simply disarm, the reaffirmation of the current nuclear posture nonetheless falls far short of the visionary and bold initiatives that U.S. and Russian presidents took twenty year ago when they ordered sweeping reductions – and eliminations – of entire classes of non-strategic nuclear weapons deployed in Europe and around the world at the time.

President George W. Bush followed up by unilaterally reducing the remaining U.S. inventory in Europe by more than 50 percent, and president Barack Obama reinvigorated arms control and disarmament aspirations around the world when he declared in Prague in 2009 that he would reduce the role of nuclear weapons to put and end to Cold War thinking. He started by ordering the unilateral retirement of the Tomahawk sea-launched land attack cruise missile – completing the elimination of all U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons from the navy, whose warships just two decades ago brought non-strategic nuclear weapons to all corners of the world.

Since then, current and former officials have been busy attaching preconditions to further reductions of non-strategic nuclear weapons. The venue for these efforts was NATO’s new Strategic Concept adopted in November 2010, which broke with two decades of unilateral reductions and decided that any further reductions of NATO forces must take into account the disparity with Russia’s larger inventory of non-strategic nuclear weapons. Why NATO suddenly needs to care so much about Russia’s aging and declining inventory of non-strategic nuclear weapons makes little sense.

Yet the Strategic Concept also promised that NATO would “seek to create the conditions for further reductions in the future” and, ultimately, “create the conditions of a world without nuclear weapons….”

Creating Conditions

So how will NATO create the conditions for further reductions and a world without nuclear weapons? The seven-page Deterrence and Defense Posture Review (DDPR) report to be released in Chicago (yes, the document will be made public) repeats this promise, but the short answer is: not by reducing forces but by studying it some more.

To that end, according to official sources, the DDPR will ask the North Atlantic Council (NAC) to task its committees to “develop concepts for how to ensure the broadest possible participation of Allies concerned [note: the DDPR identifies the “Allies concerned” as the members of the Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) – which is everyone except France] in their nuclear sharing arrangements, including in case NATO were to decide to reduce its reliance on non-strategic nuclear weapons based in Europe.” (Emphasis added).

So there appears to be some intent to reduce reliance on non-strategic nuclear weapons and adjust NPG procedures accordingly. But the DDPR also echoes the Strategic Concept formally making further reductions conditioned on Russian reductions:

“NATO is prepared to consider further reducing its requirement for non-strategic nuclear weapons assigned to the Alliance in the context of reciprocal steps by Russia, taking into account the greater Russian stockpiles of non-strategic nuclear weapons stationed in the Euro-Atlantic Area.” (Emphasis added).

Creating Obstacles

But one of the problems with using words such as “disparity” and “reciprocity” is that it is unclear what they mean and NATO has yet to explain it. For example, how much disparity is acceptable? No one expects NATO to seek parity in non-strategic nuclear weapons with Russia, so at what level does continued disparity become acceptable?

And what kinds of forces are counted when NATO talks disparity? Russia’s estimated inventory of air-delivery weapons is only a little greater than that of the United States (730 versus 500), so disparity is not significant in that weapons category. And while the Russian air-delivered weapons are stored separate from their bases, nearly 200 U.S. bombs in Europe are stored at the bases, inside aircraft shelters, a few feet below the wings of operational aircraft.

Likewise, most of Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons are in categories where NATO and the United States have none because they no longer needed them: naval weapons, air-defense weapons, and short-range ballistic missiles. No one expects NATO to argue that it needs such non-strategic nuclear weapons as well or that Russia must eliminate what it has in those categories. So does NATO’s concern over “disparity” not include those categories or does it?

The asymmetric composition of the non-strategic nuclear arsenals is one reason why it seems unclear (at best) why NATO would be able to “trade” an offer to reduce or withdraw U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe for Russian reductions in its non-strategic nuclear weapons. Most of Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons don’t exist because of U.S. nuclear bombs in Europe but to compensate for what Russia sees as NATO’s conventional superiority. So unless NATO reduces its conventional anti-submarine warfare capability, why would it expect Russia to agree to reduce or eliminate its non-strategic nuclear anti-submarine weapons?

It is simple questions like these that indicate that NATO hasn’t thought through what it means when it says that further reductions must take disparity and reciprocity with Russia into account. The DDPR to some extent acknowledges this by ordering NAC to task its committees to “develop ideas for what NATO would expect to see in the way of reciprocal Russian actions to allow for significant reductions in the forward-based non-strategic nuclear weapons assigned to NATO.” One would image that NATO had identified what it wanted from Russia before it started using “disparity” and “reciprocity” as conditions for additional reductions.

Looking Ahead

Despite the reaffirmation of nuclear status quo and other weaknesses in the DDPR, it seems that a process has been started. The Strategic Concept cleaned out most of the language that in the previous version explicitly identified the importance of U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe, and the DDPR now tasks the NAC to figure out what it would look like if NATO reduced reliance on the weapons.

But while the NATO bureaucrats cautiously consider the next round of opportunities and definitions, modernization of the nuclear posture with the more accurate B61-12 bomb and stealthy F-35 aircraft is moving ahead to improve the military capabilities of NATO’s nuclear arsenal. This undercuts the pledge to create the conditions for further reductions and a world free of nuclear weapons.

To avoid that Chicago will be seen as a nuclear arms control disappointment and NATO as a military dinosaur incapable of shedding its Cold War non-strategic nuclear armor, it is essential that NATO announces new initiatives on limiting and eliminating non-strategic nuclear weapons quickly after Chicago.

The bureaucrats cannot deliver this; it requires presidential leadership. And that’s what’s missing in Chicago: the boldness that characterized earlier unilateral initiatives. The DDPR is ironically a more cautious document produced under far less threatening circumstances. Bold reductions have been reduced to a promise to develop confidence-building and transparency measures to increase mutual understanding of NATO and Russian non-strategic weapons in Europe. That’s nice and needed, but it doesn’t make the cut.

Rather than spending yet another decade thinking about how to adjust the role of nuclear weapon in Europe, NATO needs to move quickly on a next round of non-strategic nuclear arms reductions. Instead of getting lost in “disparity” and “reciprocity,” NATO should set the pace and announce its decision to withdraw the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe and call on Russia to follow suit with its own initiatives. Doing so would create room to maneuver for moderates in Moscow and deny hardliners (in the Kremlin as well as in Brussels) the excuse to stall the process of reducing non-strategic nuclear weapons. Otherwise 2022 will be NATO Nuclear Groundhog Day all over again.

Additional Information: Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons report, May 2012 | NATO DDPR 2012

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

B61 Nuclear Bomb Costs Escalating

|

| The expected cost of the B61 Life-Extension Program has increased by 50 percent to $6 billion |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The expected cost of the B61 Life-Extension Program (LEP) has increased by 50 percent to $6 billion dollars, according to U.S. government sources.

Only one year ago, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) estimated in its Stockpile Stewardship and Management Program report to Congress that the cost of the program would be approximately $4 billion.

The escalating cost of the program – and concern that NNSA does not have an effective plan for managing it – has caused Congress to cap spending on the B61 LEP by 60 percent in 2012 and 100 percent in 2013. The Pentagon’s Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) office is currently evaluating NNSA’s cost estimate and is expected to release its assessment in July. After that, NNSA is expected to release a validated cost, schedule and scope estimate for the B61 LEP, a precondition for Congress releasing the program funds for Phase 6.3 of the program.

Ambitious Program

Beyond mismanagement, the 50 percent increase is due to the ambitious modifications that NNSA, the nuclear laboratories, and the Pentagon say are needed to extend the life of the bomb.

That includes new use-control and safety features to increase the surety of what is already the most safe warhead design in the stockpile. Several warhead design options were proposed, ranging from a simple life-extension with the current features to a significantly altered design with new optical wiring and multi-point safety. The Nuclear Weapons Council in December chose the second-most ambitious design without optical wiring and multi-point safety.

Expectation for the ambitious B61-12 program has already spawned a hiring frenzy at Sandia National Laboratory for a program that dwarfs the W76 LEP, the ongoing production of one of the navy’s Trident missile warheads. “It is the largest effort in more than 30 years, the largest, probably, since the original development of the B61-3,4,” according to the head of the B61 LEP at Sandia.

Program Justification

The Pentagon is promoting the consolidation of four B61 versions into the B61-12 as an effort to increase efficiency and lowering costs. But we have yet to see the budget justification for that and it is not clear how much of the savings will come from consolidation or from simply reducing the overall number of B61s in the stockpile. Already the consolidation part is turning out to be much more expensive than we were led to believe.

The B61 LEP was catapulted forward by the April 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, which committed – before a validated cost, schedule and scope estimate had been developed – the United States to conduct a “full scope” B61 LEP. That commitment came as part of a “deal” that promised significant investments in nuclear weapons modernization in return for Congressional approval of the New START treaty.

The Mission

The administration says that the B61 LEP is needed to provide nuclear extended deterrence to NATO allies and to continue a gravity bomb capability on the B-2 stealth bomber. According to the U.S. Air Force, the B61-12 is “critical” to “deterrence of adversaries in a regional context, and support of our extended deterrence commitments.”

But privately, U.S. Air Force officials do not see a need to continue the deployment in Europe, where the United States currently deploys nearly 200 B61-3/4 bombs in 87 aircraft shelters at six bases in five countries. And although the NATO Summit later this month is expected to endorse – for now – continuation of the current nuclear posture in Europe, none of the European allies appear to be willing to pay for continuing the mission.

Extended deterrence can be provided with other means and the B61-12 is not the only U.S. air-delivered nuclear weapon system. Indeed, the U.S. Air Force currently has seven different nuclear weapons for delivery by five different delivery platforms. After completion of the B61-12 program, the Air Force will still have four different nuclear weapons for delivery by five different aircraft.

|

| The U.S. Air Force has six different nuclear weapons for delivery by five different aircraft. After the B61 LEP it will still have four weapons for five aircraft. |

.

Why so many different ways of delivering a nuclear weapon from the sky is needed for deterrence is anyone’s guess. The nuclear redundancy in the bomber leg is significantly greater than for ICBMs and SLBMs and appears to be the result of a combination of a left-over Cold War mission in Europe and requirements developed by warfighters to hold a variety of targets at risk in a variety of different ways.

Conclusions

After having spent hundreds of millions of dollars between 2006 and 2010 on extending the service life of the secondary of the B61-7 (and adding new spin-rocket motors to improve performance), NNSA and DOD are now planning to scrap the weapon and replace it with the $6 billion B61-12.

Although the cost estimate of the B61 LEP has increased by 50 percent over the past year, the $6 billion price tag is only part of the cost. The new guided tail kit the Air Force is developing to increase the accuracy of the B61-12 is expected to cost about $800 million. And the cost of making the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter capable of delivering the bomb is estimated to add another $340 million.

|

| After having spent hundreds of millions of dollars on refurbishing the B61-7, NNSA now plans to scrap the weapon and replace it with the B61-12. |

.

The anticipated cost of the B61-12 program is now greater than the high-end cost estimate for the CMRR-NF, the plutonium pit production factory planned at Los Alamos that the Senate recently decided to mothball for at least five years due to its high cost. Or if that is not impressive enough, the cost of the B61 LEP is comparable to what NNSA plans to spend on sustaining the entire active stockpile for the next decade.

This level of nuclear cost increase and mismanagement is neither justifiable nor sustainable. It shouldn’t be normally, but it certainly isn’t in the current financial crisis. And all of this to sustain a nuclear deployment is Europe that may well end before the B61 LEP is completed and a nuclear capability on the B-2 bomber that already carries another nuclear bomb.

The current B61-12 program should be stopped and reassessed to reduce cost and scope. Congress has already asked the JASONs to examine the scope of the program and provide an assessment of any major concerns. In the meantime, the mission in Europe should temporarily be sustained with a much more basic life-extension program while the administration works to convince NATO to agree to a withdrawal of the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe. The nuclear capability of the B-2 bomber should be limited to what it already carries.

See also report: Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Report: US and Russian Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

|

| A new report describes U.S. and Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A new report estimates that Russia and the United States combined have a total of roughly 2,800 nuclear warheads assigned to their non-strategic nuclear forces. Several thousands more have been retired and are awaiting dismantlement.

The report comes shortly before the NATO Summit in Chicago on 20-21 May, where the alliance is expected to approve the conclusions of a year-long Deterrence and Defense Posture Review that will, among other things, determine the “appropriate mix” of nuclear and non-nuclear forces in Europe. It marks the 20-year anniversary of the Presidential Unilateral Initiatives in the early 1990s that resulted in sweeping reductions of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

Twenty years later, the new report Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons estimates that U.S. and Russian non-strategic nuclear forces are deployed at nearly 100 bases across Russia, Europe and the United States. The nuclear warheads assigned to these forces are in central storage, except nearly 200 bombs that the U.S. Air Force forward-deploys in almost 90 underground vaults inside aircraft shelters at six bases in five European countries.

The report concludes that excessive and outdated secrecy about non-strategic nuclear weapons inventories, characteristics, locations, missions and dismantlements have created unnecessary and counterproductive uncertainty, suspicion and worst-case assumptions that undermine relations between Russia and NATO.

Russia and the United States and NATO can and should increase transparency of their non-strategic nuclear forces by disclosing overall numbers, storage locations, delivery vehicles, and how much of their total inventories have been retired and are awaiting dismantlement.

The report concludes that unilateral reductions have been, by far, the most effective means to reducing the number and role of non-strategic nuclear weapons. Yet now the two sides appear to be holding on to the remaining weapons to have something to bargain with in a future treaty to reduce non-strategic nuclear weapons.

NATO has decided that any further reductions in U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe must take into account the larger Russian arsenal, and Russia has announced that it will not discuss reductions in its non-strategic nuclear forces unless the U.S. withdraws its non-strategic nuclear bombs from Europe. Combined, these positions appear to obstruct reductions rather facilitate reductions. Russian reductions should be a goal, not a precondition, for further NATO reductions.

Download the full report here: /_docs/Non_Strategic_Nuclear_Weapons.pdf

Slides from briefing at U.S. Senate are here: /programs/ssp/nukes/publications1/Brief2012_TacNukes.pdf

See also our Nuclear Notebooks on the total nuclear arsenals of Russia and the United States.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.