New Report Analyzing Iran’s Nuclear Program Costs and Risks

Iran’s quest for the development of nuclear program has been marked by enormous financial costs and risks. It is estimated that the program’s cost is well over $100 billion, with the construction of the Bushehr reactor costing over $11 billion, making it one of the most expensive reactors in the world.

The Federation of American Scientists and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace have released a new report, “Iran’s Nuclear Odyssey: Costs and Risks” which analyzes the economic effects of Iran’s nuclear program, and policy implications of sanctions and other actions by the United States and other allies. Co-authored by Ali Vaez and Karim Sadjadpour, the report details the history of the program, beginning with its inception under the Shah in 1957, and how the Iranian government has continue to grow their nuclear capabilities under a shroud of secrecy. Coupled with Iran’s limited supply of uranium and insecure stockpiles of nuclear materials, along with Iran’s desire to invest in nuclear energy to revitalize their energy sector (which is struggling due to international sanctions), the authors examine how these huge costs have led to few benefits.

The report analyzes the policy implications of Iran’s nuclear program for the United States and its allies, concluding that economic sanctions nor military force cannot end this prideful program; it is imperative that a diplomatic solution is reached to ensure that Iran’s nuclear program remains peaceful. Finally, efforts need to be made to the Iranians from Washington which clearly state that America and its allies prefer a prosperous and peaceful Iran versus an isolated and weakened Iran. Public diplomacy and nuclear diplomacy must go hand in hand.

FAS Symposium Provides Recommendations to Next Administration on Catastrophic Threats

On November 9, 2012, FAS hosted the Symposium on Preventing Catastrophic Threats at the National Press Club in Washington, DC. The symposium consisted of three panels that explored catastrophic threats to national and international security, including those posed by nuclear and radiological weapons; biological, chemical, cyber, and advanced conventional weapons; and threats to energy supply and infrastructure.

Distinguished panelists at the symposium offered recommendations to the Obama administration on dealing with these challenges. The following summary offers a glimpse of the issues raised and points made throughout the day. A more detailed account that includes each speaker’s memo to the president is also available in FAS’s symposium report, Recommendations to Prevent Catastrophic Threats.

Nukes, Nukes, and More Nukes

The first panel of the symposium addressed a complex set of problems regarding nuclear weapons. Mr. David Hoffman of the Washington Post served as moderator of the panel.

Dr. Sidney Drell, Deputy Director Emeritus of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, began by arguing for a reduction in the nuclear stockpiles leftover from the Cold War, renewed talks for data exchange, and increased transparency. Drell proposed reducing nuclear weapons to 1,000 or fewer. Also, he recommended that the United States and Russia create a Joint Data Exchange Center, which would foster cooperation between the two nuclear powers and provide added protection against conflict resulting from misinterpreted data. In the end, he questioned if the United States could escape the “nuclear deterrence trap.”

Dr. Richard L. Garwin, IBM Fellow Emeritus of the Thomas J. Watson Research Center, commented that nuclear weapons are a threat more than a tool, since just one nuclear explosion would cause massive destruction and death. Among the known concerns of bloated stockpiles and Pakistan’s nuclear program, Garwin addressed the possibility of improvised nuclear explosives of a “yield comparable with that of the Hiroshima or Nagasaki bombs.” He said the administration should discuss several topics together, including the role of nuclear weaponry in U.S. military forces and the managing the risks and rewards of technology built around nuclear fission. Garwin recommended that the United States remove B-61 bombs from Europe and spoke against the tendency to focus on only those issues deemed to have the highest priority, arguing the United States had enough resources to work on all of these issues at once.

Mr. Charles P. Blair, Senior Fellow on State and Non-State Threats at FAS, described a new paradigm for countering the threat of radiological and nuclear terrorism. He cautioned against presupposing that all violent non-state actor groups represent a potential nuclear threat. The counter-nuclear terrorism paradigm predicated on this assumption is costly, inefficient, and, ultimately, cannot be sustained. Blair explained that ideology indicates whether a terrorist organization would seek out and use nuclear weapons. Some terrorists might be more likely to seek a nuclear weapon given their unlimited objectives and belief in divine orders. Others will have different aims. He recommended more robust efforts to understand terrorist ideology and also their behavior after acquiring a nuclear weapon, including their likely command and control structure.

Dr. Robert S. Norris, Senior Fellow for Nuclear Policy at FAS, recommended that the Obama administration eliminate all but one mission for nuclear weapons: deterrence, narrowly defined as preserving the means for retaliation if anyone uses nuclear weapons against the United States or certain allies. Norris questioned whether the changes to U.S. nuclear policy were real or illusory, and noted the ability of bureaucracies to maintain the status quo. However, changes are necessary, Norris argued, especially with U.S. nuclear war planning – only this will allow for reductions of nuclear stockpiles.

Mr. Hans Kristensen, Director of the Nuclear Information Project at FAS, concluded the panel by analyzing the current world nuclear force structure. He argued that Russia has already moved below the New START upper limits, and they will go lower. A similar response by the U.S. would indicate our cooperation. Obama said that the U.S. needed to move away from “Cold War thinking.” Kristensen recommended reductions in the nuclear arsenal and delivery systems. One recommendation included reducing the ICBM force from 450 to 300 missiles.

The panelists addressed the nuances of nuclear weapons. All called for greater comprehension of the complexity of the problem by Obama’s administration rather than restrictive labels that indicate maintaining the status quo.

Biological, Chemical, Conventional and Cyber Threats

The second panel at the symposium discussed the threats posed by biological, chemical, conventional, and cyber weapons. Ms. Siobhan Gorman, Intelligence Reporter at the Wall Street Journal, moderated the discussion.

Mr. Matt Schroeder, Director of the Arms Sales Monitoring Project at FAS, began by describing the complexity of conventional threats, choosing to focus on the subcategory of small arms and light weapons (SALW). He explained that SALW posed the “most immediate, multi-faceted threat to U.S. interests abroad.” Mr. Schroeder argued that the United States needed to include parts, accessories, and ammunition in its definition of SALW when discussing arms control. “Without ammunition,” he said, “small arms and light weapons are useless.” Mr. Schroeder explained how SALW pose a threat because they are the “weapons of choice” for transnational forces. In particular, transnational forces favor MANPADs (man-portable air-defense systems); they are easily transportable and can do significant damage to aircraft. He recommended that the United States expand the stockpile security and destruction aid programs, targeting surplus arsenals of MANPADs that can easily be sold on the black market.

Dr. Kennette Benedict, Executive Director of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, followed by reiterating the Obama administration’s principles for cyber security, emphasizing the need for adequate defenses for the private sector. She said that the administration currently does not outline rules for cyber-attacks on other countries’ infrastructure. Dr. Benedict pointed out that current U.S. policy views cyber-attacks by another government as an act of war, allowing the United States to respond with military means. However, if a non-state actor employs a cyber-attack, then it is a criminal act. Dr. Benedict noted the difficulty in finding the origin of a cyber-attack; in fact, an individual can assume the identity of a state for a cyber-attack. She recommended that a “good defense is a good offense,” yet it could have unintended effects. Moreover, she stressed the importance of pursuing a deeper level of understanding of the relationship between cybersecurity operations to protect infrastructure and other efforts to ensure the availability and usability of cyberspace for communication, commerce, and free speech.

Ms. Marina Voronova-Abrams, Program Associate at Global Green USA, began the discussion on chemical and biological threats. She reminded the panel that several states are not parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention, including Syria and North Korea among others such as Angola, Egypt, Israel, Myanmar, Somalia, and South Sudan. Ms. Abrams called for more inspections, yet calculated the enormous number needed given that there are 4,913 declared dual-use industrial facilities across the globe. She highlighted the importance of the United States completing the destruction of its chemical weapons stockpile and then turned to the issue of biosecurity threats in the former Soviet Union. Though the threat has decreased and there is little possibility of someone using a bioweapon inside the former USSR, Ms. Abrams explained how terrorists could use their contacts in the former Soviet Union to gain access to bioagents.

Dr. David Franz, Senior Advisor to the Office of the Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs, quoted Dr. Joshua Lederberg who stated that “there is no technical solution to the problem of biological weapons […] but would an ethical solution appeal to a sociopath?” Excessive regulatory requirements can hinder productivity and creativity in the life sciences, but it is the risk that the United States has been willing to take to address the insider threat. However, looking abroad he emphasized the importance of the human dimension to biosecurity and the personal relationships among scientists, which allow not only for early warning of natural or accidental outbreaks of diseases but also for sustained, collaborative efforts that extend beyond the initial engagement phase of international outreach. Dr. Franz explained how the United States cannot lead with security in these relationships; rather, an emphasis on public health is more appropriate for tackling biosecurity challenges collaboratively. This is especially important for countries whose concern with their existing disease burdens greatly exceeds their concern for what the United States deems “especially dangerous pathogens.” Hence, Dr. Franz proposed policies that foster relationships between scientists.

Energy and Infrastructure

The symposium concluded with a panel on the issues surrounding energy and infrastructure. Mr. Miles O’Brien, Science Correspondent at PBS NewsHour, moderated the panel.

Dr. John Ahearne, former NRC Commissioner and the 2012 recipient of FAS’s Richard L. Garwin Award, began the discussion by analyzing the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident. He explained how risk analysis recommended a higher wall against tsunamis given events in the area one thousand years ago. Yet, decision makers chose a study using events in Chile in regards to earthquakes to use as the basis of their safety designs. Thus, the plant chose to build a 20-foot wall rather than the 50-foot wall proposed by the former study. He argued that this is not a lesson against nuclear power, but the problem of regulators and operators. Dr. Ahearne advised against the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) assuming the role of global regulator; rather, regulation is a national duty. However, he also noted that regulation is not the only solution; states must ensure that operators take on ensuring safety as their duty.

Dr. Steven Koonin, Director of the Center for Urban Science and Progress at New York University, argued that energy policy “success” is achieved mostly through appropriate structures and processes. He called for the establishment of a Quadrennial Energy Review (QER) process to guide energy policy. He also asserted that, ultimately, changes to the energy structure are “in the hands of the private sector.” It requires a mix of business regulations and technology development with attention paid to private sector considerations. Dr. Koonin recommended that energy policy separate stationary from transport sectors, something that is done practically yet not in policy legislation. As a result, he argued that energy policy focuses too much on stationary research and development given the importance of transportation and oil.

FAS President Dr. Charles D. Ferguson, concluded the panel by discussing international science partnerships and their role in national security. For example, FAS’s pilot project in Yemen, the International Science Partnership, is a science diplomacy initiative that brings scientists and engineers from the United States together with their counterparts from countries of security concern to solve critical water and energy security issues. Dr. Ferguson recommended specifically that the Obama administration should ensure that there are a sufficient number of scientists and engineers in government, especially in agencies such as USAID and the Department of State to facilitate science diplomacy.

Meggaen Neely was an intern communications at the Federation for American Scientists during the Fall 2012 semester, and is currently interning at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. She coordinated authors for the Up for Debate project, worked on the Did You Know Campaign and wrote accounts of events hosted by FAS. Neely is pursuing a Master of Arts in security policy studies at The Elliott School at George Washington University. She comes to Washington, DC with a Masters of Public Policy and Administration and a Bachelor of Arts in political science from Baylor University.

Photography by Monica Amarelo.

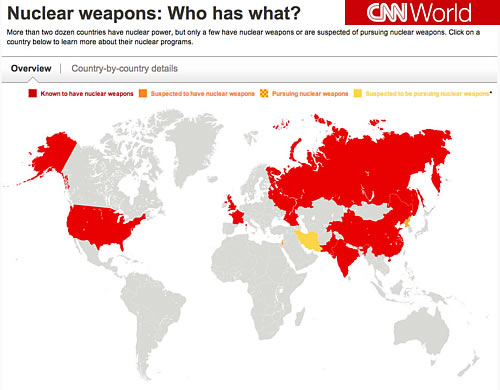

CNN Publishes Map Based on FAS Research

FAS supplied the data for a new interactive web site published by CNN. The site enables you to get a quick overlook of the nuclear arsenals of the world’s nine nuclear weapon states. Check it out here.

Update (April 17, 2013): CNN told me that the site had just under 2 million page views, with average time spent of well over 3 minutes per visit. “That’s really good,” they said.

Q&A Session on Recent Developments in U.S. and NATO Missile Defense with Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis

Dr. Yousaf Butt, a nuclear physicist, is professor and scientist-in-residence at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. The views expressed are his own.

Dr. George N. Lewis is a senior research associate at the Judith Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies at Cornell University.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked two physicists who are experts in missile defense issues, Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis, to weigh in on last week’s announcements on missile defense by the Obama administration.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked two physicists who are experts in missile defense issues, Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis, to weigh in on last week’s announcements on missile defense by the Obama administration.

Before exploring their reactions and insights, it is useful to identify salient elements of U.S. missile defense and place the issue in context. There are two main strategic missile defense systems fielded by the United States: one is based on large high-speed interceptors called Ground-Based Interceptors or “GBI’s” located in Alaska and California and the other is the mostly ship-based NATO/European system. The latter, European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) to missile defense is designed to deal with the threat posed by possible future Iranian intermediate- and long-range ballistic missiles to U.S. assets, personnel, and allies in Europe – and eventually attempt to protect the U.S. homeland.

The EPAA uses ground-based and mobile ship-borne radars; the interceptors themselves are mounted on Ticonderoga class cruisers and Arleigh Burke class destroyers. Two land-based interceptor sites in Poland and Romania are also envisioned – the so-called “Aegis-ashore” sites. The United States and NATO have stated that the EPAA is not directed at Russia and poses no threat to its nuclear deterrent forces, but as outlined in a 2011 study by Dr. Theodore Postol and Dr. Yousaf Butt, this is not completely accurate because the system is ship-based, and thus mobile it could be reconfigured to have a theoretical capability to engage Russian warheads.

Indeed, General James Cartwright has explicitly mentioned this possible reconfiguration – or global surge capability – as an attribute of the planned system: “Part of what’s in the budget is to get us a sufficient number of ships to allow us to have a global deployment of this capability on a constant basis, with a surge capacity to any one theater at a time.”

In the 2011 study, the authors focused on what would be the main concern of cautious Russian military planners —the capability of the missile defense interceptors to simply reach, or “engage,” Russian strategic warheads—rather than whether any particular engagement results in an actual interception, or “kill.” Interceptors with a kinematic capability to simply reach Russian ICBM warheads would be sufficient to raise concerns in Russian national security circles – regardless of the possibility that Russian decoys and other countermeasures might defeat the system in actual engagements. In short, even a missile defense system that could be rendered ineffective could still elicit serious concern from cautious Russian planners. The last two phases of the EPAA – when the higher burnout velocity “Block II” SM-3 interceptors come on-line in 2018 – could raise legitimate concerns for Russian military analysts.

A Russian news report sums up the Russian concerns: “[Russian foreign minister] Lavrov said Russia’s agreement to discuss cooperation on missile defense in the NATO Russia Council does not mean that Moscow agrees to the NATO projects which are being developed without Russia’s participation. The minister said the fulfillment of the third and fourth phases of the U.S. ‘adaptive approach’ will enter a strategic level threatening the efficiency of Russia’s nuclear containment forces.” [emphasis added]

With this background in mind, FAS’ Senior Fellow on State and Non-State Threat, Charles P. Blair (CB), asked Dr. Yousaf Butt (YB) and Dr. George Lewis (GL) for their input on recent developments on missile defense with eight questions.

Q: (CB) Last Friday, Secretary of Defense Hagel announced that the U.S. will cancel the last Phase – Phase 4 – of the European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) to missile defense which was to happen around 2021. This was the phase with the faster SM-3 “Block IIB” interceptors. Will this cancellation hurt the United State’s ability to protect itself and Europe?

A: (YB) No, because the “ability” you mention was always hypothetical. The Achilles’ Heel of all versions of the SM-3 (Block I A/B and Block II A/B) interceptors — indeed of “midcourse” missile defense, in general, is that it is straightforward to defeat the system using cheap decoy warheads. The system simply does not have a robust ability to discriminate a genuine warhead from decoys and other countermeasures. Because the intercepts take place in the vacuum of space, the heavy warhead and light decoys travel together, confusing the system’s sensors. The Pentagon’s own scientists at the Defense Science Board said as much in 2011, as did the National Academy of Sciences earlier this year.

Additionally, the system has never been successfully tested in realistic conditions stressed by the presence of decoys or other countermeasures. The majority of the system would be ship-based and is not known to work beyond a certain sea-state: as you might imagine, it becomes too risky to launch the interceptors if the ship is pitching wildly.

So any hypothetical (possibly future) nuclear-armed Middle Eastern nation with ICBMs could be a threat to the Unites States or Europe whether we have no missile defenses, have just Block I interceptors, or even the Block II interceptors. Since the interceptors would only have offered a false sense of security, nothing is lost in canceling Phase 4 of the EPAA. In fact, the other phases could also be canceled with no loss to U.S. or NATO security, and offering considerable saving of U.S. taxpayer’s money.

Q: (CB) What about Iran and its alleged desire to build ICBMs? Having just launched a satellite in January, could such actions act as a cover for an ICBM?

A: (YB) The evidence does not point that way at all. It points the other way. For instance, the latest Congressional Research Service (CRS) report on Iran’s missile program observes: (emphasis added)

“Iran also has a genuine and ambitious space launch program, which seeks to enhance Iran’s national pride, and perhaps more importantly, its international reputation as a growing advanced industrial power. Iran also sees itself as a potential leader in the Middle East offering space launch and satellite services. Iran has stated it plans to use future launchers for placing intelligence gathering satellites into orbit, although such a capability is a decade or so in the future. Many believe Iran’s space launch program could mask the development of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) – with ranges in excess of 5,500 km that could threaten targets throughout Europe, and even the United States if Iran achieved an ICBM capability of at least 10,000 km. ICBMs share many similar technologies and processes inherent in a space launch program, but it seems clear that Iran has a dedicated space launch effort and it is not simply a cover for ICBM development. Since 1999, the U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) has assessed that Iran could test an ICBM by 2015 with sufficient foreign assistance, especially from a country such as China or Russia (whose support has reportedly diminished over the past decade). It is increasingly uncertain whether Iran will be able to achieve an ICBM capability by 2015 for several reasons: Iran does not appear to be receiving the degree of foreign support many believe would be necessary, Iran has found it increasingly difficult to acquire certain critical components and materials because of sanctions, and Iran has not demonstrated the kind of flight test program many view as necessary to produce an ICBM.”

Furthermore, the payload of Iran’s space launch vehicles is very low compared to what would be needed for a nuclear warhead — or even a substantial conventional warhead. For instance, Omid, Iran’s first satellite weighed just 27 kg [60 pounds] and Rasad-1, Iran’s second satellite weighed just 15.3 kilograms [33.74 pound], whereas a nuclear warhead would require a payload capacity on the order of 1000 kilograms. Furthermore, since launching an ICBM from Iran towards the United States or Europe requires going somewhat against the rotation of Earth the challenge is greater. As pointed out by missile and space security expert Dr. David Wright, an ICBM capable of reaching targets in the United States would need to have a range longer than 11,000 km. Drawing upon the experience of France in making solid-fuel ICBMs, Dr. Wright estimates it may take 40 years for Iran to develop a similar ICBM – assuming it has the intention to kick off such an effort. A liquid fueled rocket could be developed sooner, but there is little evidence in terms of rocket testing that Iran has kicked off such an effort.

In any case, it appears that informed European officials are not really afraid of any hypothetical Iranian missiles. For example, the Polish foreign minister, Radoslaw Sikorski, once made light of the whole scenario telling Foreign Policy, “If the mullahs have a target list we believe we are quite low on it.” As if to emphasize that point, the Europeans don’t appear to be pulling their weight in terms of funding the system. “We love the capability but just don’t have the money,” one European military official stated in reference to procuring the interceptors.

Similarly, the alleged threat from North Korea is also not all that urgent.

It seems U.S. taxpayers are subsidizing a project that will have little national security benefits either for the United States or NATO countries. In contrast, it may well create a dangerous false sense of security. It has already negatively impacted ties with Russia and China.

Q: (CB) Isn’t Iran’s alleged nuclear weapons program a big concern in arguing for a missile defense? Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel said Iran may cross some red-line in the summer?

A: (YB) Iran’s nuclear program could be a concern, but the latest report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) says Iran has not even decided to make nuclear weapons yet. Building, testing and miniaturizing a warhead to fit on a missile takes years – after a country decides to do so. In any case, no matter how scary that hypothetical prospect, one would not want a missile defense system that could be easily defeated to address that alleged eventual threat. Even if you believe the threat exists now, you may want a system that is effective, not a midcourse system that has inherent flaws.

Incidentally, the DNI’s report explicitly states: “we assess Iran could not divert safeguarded material and produce a weapon-worth of WGU [weapons grade uranium] before this activity is discovered.” As for the red-line drawn by Prime Minister Netanyahu: his track-record on predicting Iranian nuclear weaponization has been notoriously bad. As I point out in a recent piece for Reuters, in 1992 Mr. Netanyahu said Iran was three to five years from a bomb. I assess he is still wrong, more than 20 years later.

Lastly, even if Iran (or other nations) obtained nuclear weapons in the future, they can be delivered in any number of ways- not just via missiles. In fact, nuclear missiles have the benefit of being self-deterring – nations are actually hesitant to use nuclear weapons if they are mated to missiles. Other nations know that the United States can pinpoint the launch sites of missiles. The same cannot be said of a nuclear device placed in a sailboat, a reality that could precipitate the use of that type of device due to the lack of attribution. So one has to carefully consider if it makes sense to dissuade the placement of nuclear weapons on missiles. If an adversarial nation has nuclear weapons it may be best to have them mated to missiles rather than boats.

Q: (CB) It seems that the Russians are still concerned about the missile defense system, even after Defense Secretary Hagel said that the fourth phase of EPAA plan is canceled. Why are they evidently still concerned?

A: (YB) The Russians probably have four main concerns with NATO missile defense, even after the cancellation of Phase 4 of EPAA. For more details on some of these please see the report Ted Postol and I wrote.

1. The first is geopolitical: the Russians have never been happy about the Eastward expansion of NATO and they see joint U.S.-Polish and U.S.-Romanian missile defense bases near their borders as provocative. This is not to say they are right or wrong, but that is most likely their perception. These bases are to be built before Phase 4 of the EPAA, so they are still in the plans.

2. The Russians do not concur with the alleged long-range missile threat from Iran. One cannot entirely blame them when the Polish foreign minister himself makes light of the alleged threat saying, “If the mullahs have a target list we believe we are quite low on it.” Russian officials are possibly confused and their military analysts may even be somewhat alarmed, mulling what the real intent behind these missile defense bases could be, if – in their assessment – the Iran threat is unrealistic, as in fact was admitted to by the Polish foreign minister. The Russians also have to take into account unexpected future changes which may occur on these bases, for instance: a change in U.S. or Polish or Romanian administrations; a large expansion of the number or types of interceptors; or, perhaps even nuclear-tipped interceptors (which were proposed by former Defense Secretary Rumsfeld about ten years ago).

3. Russian military planners are properly hyper-cautious, just like their counterparts at the Pentagon, and they must assume a worst-case scenario in which the missile defense system is assumed to be effective, even when it isn’t. This concern likely feeds into their fear that the legal balance of arms agreed to in New START may be upset by the missile defense system.

Their main worry could be with the mobile ship-based platforms and less with the European bases, as explained in detail in the study Ted Postol and I did. Basically, the Aegis missile defense cruisers could be placed off of the East Coast of the U.S. and – especially with Block IIA/B interceptors –engage Russian warheads. Some statements from senior U.S. officials probably play into their fears. For instance, General Cartwright has been quoted as saying, “part of what’s in the budget is to get us a sufficient number of ships to allow us to have a global deployment of this capability on a constant basis, with a surge capacity to any one theater at a time.” To certain Russian military planners’ ears that may not sound like a limited system aimed at a primitive threat from Iran.

Because the mobile ship-based interceptors (hypothetically placed off of the U.S. East Coast ) could engage Russian warheads, Russian officials may be able claim this as an infringement on New START parity.

Missile defenses that show little promise of working well can, nevertheless, alter perceptions that the strategic balance between otherwise well-matched states is stable. Even when missile defenses reveal that they possess little, if any technical capabilities, they can still cause cautious adversaries and competitors to react as if they might work. The United States’ response to the Cold War era Soviet missile defense system was similarly overcautious.

4. Finally, certain Russian military planners may worry about the NATO EPAA missile defense system because in Phase 3, the interceptors are to be based on the SM-3 Block IIA booster. The United States has conducted research using this same type of rocket booster as the basis of a hypersonic-glide offensive strike weapon called ArcLight. Because such offensive hyper-glide weapons could fit into the very same vertical launch tubes – on the ground in Poland and Romania, or on the Aegis ships – used for the defensive interceptors, the potential exists for turning a defensive system into an offensive one, in short order. Although funding for ArcLight has been eliminated in recent years, Russian military planners may continue to worry that perhaps the project “went black” [secret], or that it may be resuscitated in the future. In fact, a recent Federal Business Opportunity (FBO) for the Department of the Navy calls for hypersonic weapons technologies that could fit into the same Mk. 41 Vertical Launch System (VLS) tubes that the SM-3 missile defense interceptors are also placed in.

To conclude, advocates of missile defense who say we need cooperation on missile defense to improve ties with Russia have the logic exactly backward: In large part, the renewed tension between Russia and the United States is about missile defense. Were we to abandon this flawed and expensive idea, our ties with Russia — and China — would naturally improve. And, in return, they could perhaps help us more with other foreign policy issues such as Iran, North Korea, and Syria. As it stands, missile defense is harming bilateral relations with Russia and poisoning the well of future arms control.

Q: (CB) Adding to the gravity of Secretary Hagel’s announcement , last week China expressed worry about Ground-Based Interceptors, the Bush administration’s missile defense initiative in Poland discarded by the Obama administration in 2009, in favor of Phase 4 of the EPAA. Why is there concern with not only the Aegis ship-based system, but also the GBIs on the West Coast?

A: (YB) Like the Russians, Chinese military analysts are also likely to assume the worst-case scenario for the system (ie. that it will work perfectly) in coming up with their counter response . Possessing a much smaller nuclear arsenal than Russia or the United States, to China, even a few interceptors can be perceived as making a dent in their deterrent forces. And I think the Chinese are likely worried about both the ship-based Aegis system as well as the West Coast GBIs.

And this concern on the part of the Chinese is nothing new. They have not been as vocal as the Russians, but it is evident they were never content with U.S. and NATO plans. For instance, the 2009 Bipartisan Strategic Posture Commission pointed out that “China may already be increasing the size of its ICBM force in response to its assessment of the U.S. missile defense program.” Such stockpile increases, if they are taking place, will probably compel India, and, in turn, Pakistan to also ramp up their nuclear weapon numbers.

The Chinese may also be looking to the future and think that U.S. defenses may encourage North Korea to field more missiles than it may originally have been intending – if and when the North Koreans make long range missiles – to make sure some get through the defense system. This would have an obvious destabilizing effect in East Asia which the Chinese would rather avoid.

Some U.S. media outlets have also said the ship-based Aegis system could be used against China’s DF-21D anti-ship missile, when the official U.S. government position has always been that the system is only intended only against North Korea (in the Pacific theater). Such mission creep could sound provocative to the Chinese, who were told that the Aegis system is not “aimed at” China.

In reality, while the Aegis system’s sensors may be able to help track the DF-21D it is unlikely that the interceptors could be easily modified to work within the atmosphere where the DF-21D’s kill vehicle travels. (It could perhaps be intercepted at apogee during the ballistic phase). A recent CRS report was quite explicit that the DF-21D is a threat which remains unaddressed in the Navy: “No Navy target program exists that adequately represents an anti-ship ballistic missile’s trajectory,’ Gilmore said in the e-mail. The Navy ‘has not budgeted for any study, development, acquisition or production’ of a DF-21D target, he said.”

Chinese concerns about U.S. missile defense systems are also a source of great uncertainty, reducing Chinese support for promoting negotiations on the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty (FMCT). China’s leaders may wish to maintain the option of future military plutonium production in response to U.S. missile defense plans.

The central conundrum of midcourse missile defense remains that while it creates incentives for adversaries and competitors of the United States to increase their missile stockpiles, it offers no credible combat capability to protect the United States or its allies from this increased weaponry.

Q: (CB) Will a new missile defense site on the East Coast protect the United States? What would be the combat effectiveness of an East Coast site against an assumed Iranian ICBM threat?

A: (GL) I don’t see any real prospect for even starting a program for interceptors such as the [East Coast site] NAS is proposing any time soon in the current budget environment, and even if they did it probably would not be available until the 2020s. The recent announcement of the deployment of additional GBI interceptors is, in my view, just cover for getting rid of the Block II Bs, and was chosen because it was relatively ($1+ billion) inexpensive and could be done quickly.

The current combat effectiveness of the GBIs against an Iranian ICBM must be expected to be low. Of course there is no current Iranian ICBM threat. However, the current GMD system shows no prospect of improved performance against any attacker that takes any serious steps to defeat it as far out in time, as plans for this system are publicly available. Whether the interceptors are based in Alaska or on the East Coast makes very little difference to their performance.

Q: (CB) There were shortcomings reported by the Defense Science Board and the National Academies regarding the radars that are part of the system. Has anything changed to improve this situation?

A: (GL) With respect to radars, the main point is that basically nothing has happened. The existing early warning radars can’t discriminate [between real warheads and decoys]. The only radar that could potentially contribute to discrimination, the SBX, has been largely mothballed.

Q: (CB) Let’s say the United States had lots of money to spend on such a system, would an East Coast site have the theoretical ability to engage Russian warheads? Regardless of whether Russia could defeat the system with decoys or countermeasures, does the system have an ability to reach or engage the warheads? In short, could such a site be a concern for Russia?

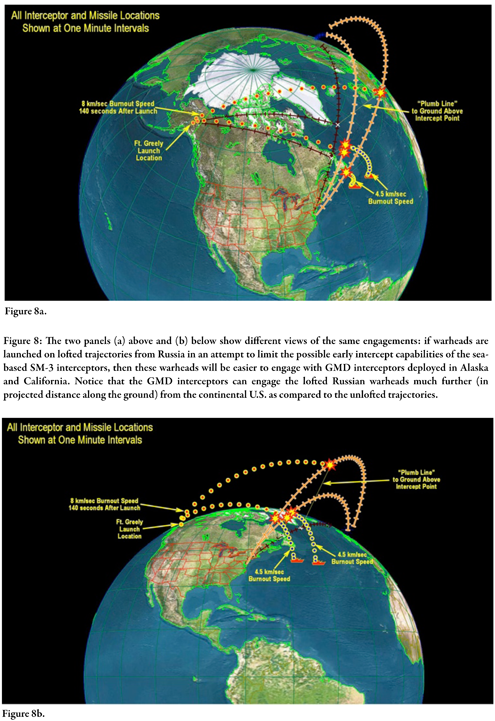

A: (YB) If you have a look at Fig 8(a) and 8(b) in the report Ted Postol and I wrote you’ll see pretty clearly why an East Coast site might be a concern for Russia, especially with faster interceptors that are proposed for that site. Now I’m not saying it necessarily should be a concern – because they can defeat the system rather easily – but it may be. Whether they object to it or not vocally depends on other factors also. For instance, such a site will obviously not be geopolitically problematic for the Russians.

Figures 8(a) and 8(b) from the FAS Special Report Upsetting the Reset: The Technical Basis of Russian Concern Over NATO Missile Defense, by Yousaf Butt and Theodore Postol (p. 27).

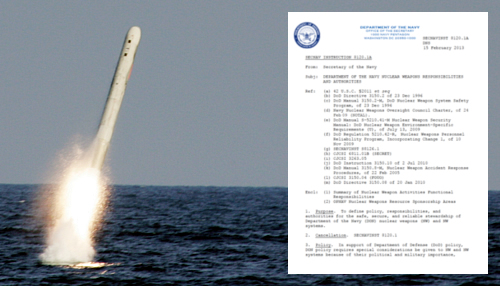

US Navy Instruction Confirms Retirement of Nuclear Tomahawk Cruise Missile

The U.S. Navy has quietly removed the nuclear Tomahawk cruise missile from its inventory, a new Secretary of the Navy Instruction shows.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Although the U.S. Navy has yet to make a formal announcement that the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N) has been retired, a new updated navy instruction shows that the weapon is gone.

The evidence comes not in the form of an explicit statement, but from what has been deleted from the U.S. Navy’s instruction Department of the Navy Nuclear Weapons Responsibilities and Authorities (SECNAVINST 8120.1A).

While the previous version of the instruction from 2010 included a whole sub-section describing TLAM/N responsibilities, the new version published on February 15, 2013, contains no mentioning of the TLAM/N at all and the previous sub-section has been deleted.

The U.S. Navy is finally out of the non-strategic nuclear weapons business. The stockpile has declined and a substantial number of TLAM/N warheads (W80-0) have already been dismantled. [Update 21 Mar: FY12 Pantex Performance Evaluation Report states (p.24): “All W80-0 warheads in the stockpile have been dismantled.” (Thanks Jay!)].

The End Of An Era

The retirement of the TLAM/N completes a 25-year process of eliminating all non-strategic naval nuclear weapons from the U.S. Navy’s arsenal.

In 1989, diligent researchers using the Freedom of Information Act discovered that the navy planned to unilaterally retire three of its non-strategic nuclear weapons.

|

| Retirement of the TLAM/N comes two decades after the U.S. Navy retired the SUBROC, ASROC, and Terrier. |

The first to go was the SUBROC, a submarine-launched rocket introduced in 1965 to deliver a 5-kiloton nuclear torpedo against another submarine. The SUBROC was widely deployed on attack submarines for 24 years and retired in 1989.

The ASROC was next in line, a ship-launched rocket introduced in 1961 to deliver a 10-kiloton depth bomb against submarines. The ASROC was widely deployed on cruisers, destroyers, and frigates for 29 years and retired in 1990.

The third non-strategic nuclear weapon to be unilaterally retired was the nuclear Terrier, a ship-launched surface-to-air missile introduced in 1961 to deliver a 1-kiloton warhead against aircraft. The nuclear Terrier was retired in 1990 after 29 years.

These weapons had little military value but huge political consequences when they sailed into ports of allied countries whose governments were forced to ignore violation of their own non-nuclear policies to avoid being seen as disloyal to their nuclear-armed ally.

The Regan administration planned to replace all of these weapons with new types: the SUBROC would be replaced by the Sea Lance rocket; the ASROC would be replaced with the Vertical ASROC; and the Terrier was to be replaced by the Standard 2 missile. But all of these replacement programs were cancelled. The Harpoon cruise missile was also intended to have a nuclear warhead option, but that was also canceled. Originally 758 TLAM/Ns were planned but only 350 were built, and 260 were left when the Obama administration decided to retire the weapon.

After the unilateral retirement of the SUBROC, ASROC, and Terrier missiles, the navy was left with B61 and B57 bombs on aircraft carriers and land-based anti-submarine aircraft, as well as the TLAM/N. Work initially continued on the B90 NSDB (nuclear strike and depth bomb) to replace the naval B61 and B57, but in September 1991 president George H.W. Bush unilaterally cancelled the program and ordered the offloading and withdrawal of all non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The Clinton administration’s 1994 Nuclear Posture Review followed up by denuclearizing the entire surface fleet, leaving only TLAM/N for some of the navy’s attack submarines. The missiles were stored on land, however, and never made it back to sea.

In the early part of the George W. Bush administration, the navy wanted to retire the TLAM/N, but some officials in the National Security Council and the Office of the Secretary of Defense insisted that the weapon was needed for certain missions in defense of allied countries. As a result, the TLAM/N survived the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review, and up through 2005 the navy continued to test launch the missile from attack submarines.

Some official and lobbyists tried to protect the TLAM/N during the 2009 Congressional Strategic Posture Commission process, but they failed. The Obama administration’s 2010 Nuclear Posture Review determined that the TLAM/N should finally be retired because it was redundant.

Implications

More than two decades after the end of the Cold War, and tens of millions of dollars and countless of navy personnel hours wasted on retaining the TLAM/N, the weapon has finally been retired and the navy is out of the non-strategic nuclear weapons business altogether.

This is monumental achievement and marks the end of a long process. In 1987, the U.S. Navy possessed more than 3,700 non-strategic nuclear weapons for use by almost 240 nuclear-capable ships and attack submarines in nuclear battles on the high seas. Today the number is zero.

Submarine crews can finally focus on real-world operations without the burden of non-strategic nuclear weapons, and government officials from the United States and its Pacific allies can finally begin to think about how to structure extended deterrence without clinging to the Cold War illusion that it requires tactical naval nuclear weapons.

I only wish the Obama administration and its allies were not so timid about the achievement. The unilateral elimination of naval non-strategic nuclear weapons is an important milestone in U.S. nuclear weapons history that demonstrates that non-strategic nuclear weapons have lost their military and political value. Russia has partly followed the initiative by eliminating a third of its non-strategic naval nuclear weapons since 1991, but is holding on to the rest to compensate against superior U.S. conventional naval forces.

But why not propose to Russia that they follow the TLAM/N retirement by retiring their nuclear land-attack cruise missile, the SS-N-21, and stop building new ones? The land-attack cruise missiles have nothing to do with compensating for naval conventional inferiority. Highlighting the retirement of the TLAM/N, moreover, might even help undercut some of the North Korean Generals’ rhetoric about a U.S. nuclear threat. Milk the TLAM/N retirement for all it’s worth!

Documents: SECNAVINST 8120.1 (2010) | SECNAVINST 8120.1A (2013) | Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons (FAS, May 2012)

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Q&A Session on Recent Developments in U.S. and NATO Missile Defense

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked two physicists who are experts in missile defense issues, Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis, to weigh in on the announcement on March 15, 2013 regarding missile defense by the Obama administration.

Before exploring their reactions and insights, it is useful to identify salient elements of U.S. missile defense and place the issue in context. There are two main strategic missile defense systems fielded by the United States: one is based on large high-speed interceptors called Ground-Based Interceptors or “GBI’s” located in Alaska and California and the other is the mostly ship-based NATO/European system. The latter, European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) to missile defense is designed to deal with the threat posed by possible future Iranian intermediate- and long-range ballistic missiles to U.S. assets, personnel, and allies in Europe – and eventually attempt to protect the U.S. homeland.

The EPAA uses ground-based and mobile ship-borne radars; the interceptors themselves are mounted on Ticonderoga class cruisers and Arleigh Burke class destroyers. Two land-based interceptor sites in Poland and Romania are also envisioned – the so-called “Aegis-ashore” sites. The United States and NATO have stated that the EPAA is not directed at Russia and poses no threat to its nuclear deterrent forces, but as outlined in a 2011 study by Dr. Theodore Postol and Dr. Yousaf Butt, this is not completely accurate because the system is ship-based, and thus mobile it could be reconfigured to have a theoretical capability to engage Russian warheads.

Indeed, General James Cartwright has explicitly mentioned this possible reconfiguration – or global surge capability – as an attribute of the planned system: “Part of what’s in the budget is to get us a sufficient number of ships to allow us to have a global deployment of this capability on a constant basis, with a surge capacity to any one theater at a time.”

In the 2011 study, the authors focused on what would be the main concern of cautious Russian military planners —the capability of the missile defense interceptors to simply reach, or “engage,” Russian strategic warheads—rather than whether any particular engagement results in an actual interception, or “kill.” Interceptors with a kinematic capability to simply reach Russian ICBM warheads would be sufficient to raise concerns in Russian national security circles – regardless of the possibility that Russian decoys and other countermeasures might defeat the system in actual engagements. In short, even a missile defense system that could be rendered ineffective could still elicit serious concern from cautious Russian planners. The last two phases of the EPAA – when the higher burnout velocity “Block II” SM-3 interceptors come on-line in 2018 – could raise legitimate concerns for Russian military analysts.

A Russian news report sums up the Russian concerns: “[Russian foreign minister] Lavrov said Russia’s agreement to discuss cooperation on missile defense in the NATO Russia Council does not mean that Moscow agrees to the NATO projects which are being developed without Russia’s participation. The minister said the fulfillment of the third and fourth phases of the U.S. ‘adaptive approach’ will enter a strategic level threatening the efficiency of Russia’s nuclear containment forces.” [emphasis added]

With this background in mind, FAS’ Senior Fellow on State and Non-State Threat, Charles P. Blair (CB), asked Dr. Yousaf Butt (YB) and Dr. George Lewis (GL) for their input on recent developments on missile defense with eight questions.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Q: (CB)On March 15, Secretary of Defense Hagel announced that the U.S. will cancel the last Phase – Phase 4 – of the European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) to missile defense which was to happen around 2021. This was the phase with the faster SM-3 “Block IIB” interceptors. Will this cancellation hurt the United State’s ability to protect itself and Europe?

A: (YB) No, because the “ability” you mention was always hypothetical. The Achilles’ Heel of all versions of the SM-3 (Block I A/B and Block II A/B) interceptors — indeed of “midcourse” missile defense, in general, is that it is straightforward to defeat the system using cheap decoy warheads. The system simply does not have a robust ability to discriminate a genuine warhead from decoys and other countermeasures. Because the intercepts take place in the vacuum of space, the heavy warhead and light decoys travel together, confusing the system’s sensors. The Pentagon’s own scientists at the Defense Science Board said as much in 2011, as did the National Academy of Sciences earlier this year.

Additionally, the system has never been successfully tested in realistic conditions stressed by the presence of decoys or other countermeasures. The majority of the system would be ship-based and is not known to work beyond a certain sea-state: as you might imagine, it becomes too risky to launch the interceptors if the ship is pitching wildly.

So any hypothetical (possibly future) nuclear-armed Middle Eastern nation with ICBMs could be a threat to the Unites States or Europe whether we have no missile defenses, have just Block I interceptors, or even the Block II interceptors. Since the interceptors would only have offered a false sense of security, nothing is lost in canceling Phase 4 of the EPAA. In fact, the other phases could also be canceled with no loss to U.S. or NATO security, and offering considerable saving of U.S. taxpayer’s money.

Q: (CB) What about Iran and its alleged desire to build ICBMs? Having just launched a satellite in January, could such actions act as a cover for an ICBM?

A: (YB) The evidence does not point that way at all. It points the other way. For instance, the latest Congressional Research Service (CRS) report on Iran’s missile program observes: (emphasis added)

“Iran also has a genuine and ambitious space launch program, which seeks to enhance Iran’s national pride, and perhaps more importantly, its international reputation as a growing advanced industrial power. Iran also sees itself as a potential leader in the Middle East offering space launch and satellite services. Iran has stated it plans to use future launchers for placing intelligence gathering satellites into orbit, although such a capability is a decade or so in the future. Many believe Iran’s space launch program could mask the development of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) – with ranges in excess of 5,500 km that could threaten targets throughout Europe, and even the United States if Iran achieved an ICBM capability of at least 10,000 km. ICBMs share many similar technologies and processes inherent in a space launch program, but it seems clear that Iran has a dedicated space launch effort and it is not simply a cover for ICBM development. Since 1999, the U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) has assessed that Iran could test an ICBM by 2015 with sufficient foreign assistance, especially from a country such as China or Russia (whose support has reportedly diminished over the past decade). It is increasingly uncertain whether Iran will be able to achieve an ICBM capability by 2015 for several reasons: Iran does not appear to be receiving the degree of foreign support many believe would be necessary, Iran has found it increasingly difficult to acquire certain critical components and materials because of sanctions, and Iran has not demonstrated the kind of flight test program many view as necessary to produce an ICBM.”

Furthermore, the payload of Iran’s space launch vehicles is very low compared to what would be needed for a nuclear warhead — or even a substantial conventional warhead. For instance, Omid, Iran’s first satellite weighed just 27 kg [60 pounds] and Rasad-1, Iran’s second satellite weighed just 15.3 kilograms [33.74 pound], whereas a nuclear warhead would require a payload capacity on the order of 1000 kilograms. Furthermore, since launching an ICBM from Iran towards the United States or Europe requires going somewhat against the rotation of Earth the challenge is greater. As pointed out by missile and space security expert Dr. David Wright, an ICBM capable of reaching targets in the United States would need to have a range longer than 11,000 km. Drawing upon the experience of France in making solid-fuel ICBMs, Dr. Wright estimates it may take 40 years for Iran to develop a similar ICBM – assuming it has the intention to kick off such an effort. A liquid fueled rocket could be developed sooner, but there is little evidence in terms of rocket testing that Iran has kicked off such an effort.

In any case, it appears that informed European officials are not really afraid of any hypothetical Iranian missiles. For example, the Polish foreign minister, Radoslaw Sikorski, once made light of the whole scenario telling Foreign Policy, “If the mullahs have a target list we believe we are quite low on it.” As if to emphasize that point, the Europeans don’t appear to be pulling their weight in terms of funding the system. “We love the capability but just don’t have the money,” one European military official stated in reference to procuring the interceptors.

Similarly, the alleged threat from North Korea is also not all that urgent.

It seems U.S. taxpayers are subsidizing a project that will have little national security benefits either for the United States or NATO countries. In contrast, it may well create a dangerous false sense of security. It has already negatively impacted ties with Russia and China.

Q: (CB) Isn’t Iran’s alleged nuclear weapons program a big concern in arguing for a missile defense? Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel said Iran may cross some red-line in the summer?

A: (YB) Iran’s nuclear program could be a concern, but the latest report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) says Iran has not even decided to make nuclear weapons yet. Building, testing and miniaturizing a warhead to fit on a missile takes years – after a country decides to do so. In any case, no matter how scary that hypothetical prospect, one would not want a missile defense system that could be easily defeated to address that alleged eventual threat. Even if you believe the threat exists now, you may want a system that is effective, not a midcourse system that has inherent flaws.

Incidentally, the DNI’s report explicitly states: “we assess Iran could not divert safeguarded material and produce a weapon-worth of WGU [weapons grade uranium] before this activity is discovered.” As for the red-line drawn by Prime Minister Netanyahu: his track-record on predicting Iranian nuclear weaponization has been notoriously bad. As I point out in a recent piece for Reuters, in 1992 Mr. Netanyahu said Iran was three to five years from a bomb. I assess he is still wrong, more than 20 years later.

Lastly, even if Iran (or other nations) obtained nuclear weapons in the future, they can be delivered in any number of ways- not just via missiles. In fact, nuclear missiles have the benefit of being self-deterring – nations are actually hesitant to use nuclear weapons if they are mated to missiles. Other nations know that the United States can pinpoint the launch sites of missiles. The same cannot be said of a nuclear device placed in a sailboat, a reality that could precipitate the use of that type of device due to the lack of attribution. So one has to carefully consider if it makes sense to dissuade the placement of nuclear weapons on missiles. If an adversarial nation has nuclear weapons it may be best to have them mated to missiles rather than boats.

Q: (CB) It seems that the Russians are still concerned about the missile defense system, even after Defense Secretary Hagel said that the fourth phase of EPAA plan is canceled. Why are they evidently still concerned?

A: (YB) The Russians probably have four main concerns with NATO missile defense, even after the cancellation of Phase 4 of EPAA. For more details on some of these please see the report Ted Postol and I wrote.

1. The first is geopolitical: the Russians have never been happy about the Eastward expansion of NATO and they see joint U.S.-Polish and U.S.-Romanian missile defense bases near their borders as provocative. This is not to say they are right or wrong, but that is most likely their perception. These bases are to be built before Phase 4 of the EPAA, so they are still in the plans.

2. The Russians do not concur with the alleged long-range missile threat from Iran. One cannot entirely blame them when the Polish foreign minister himself makes light of the alleged threat saying, “If the mullahs have a target list we believe we are quite low on it.” Russian officials are possibly confused and their military analysts may even be somewhat alarmed, mulling what the real intent behind these missile defense bases could be, if – in their assessment – the Iran threat is unrealistic, as in fact was admitted to by the Polish foreign minister. The Russians also have to take into account unexpected future changes which may occur on these bases, for instance: a change in U.S. or Polish or Romanian administrations; a large expansion of the number or types of interceptors; or, perhaps even nuclear-tipped interceptors (which were proposed by former Defense Secretary Rumsfeld about ten years ago).

3. Russian military planners are properly hyper-cautious, just like their counterparts at the Pentagon, and they must assume a worst-case scenario in which the missile defense system is assumed to be effective, even when it isn’t. This concern likely feeds into their fear that the legal balance of arms agreed to in New START may be upset by the missile defense system.

Their main worry could be with the mobile ship-based platforms and less with the European bases, as explained in detail in the study Ted Postol and I did. Basically, the Aegis missile defense cruisers could be placed off of the East Coast of the U.S. and – especially with Block IIA/B interceptors –engage Russian warheads. Some statements from senior U.S. officials probably play into their fears. For instance, General Cartwright has been quoted as saying, “part of what’s in the budget is to get us a sufficient number of ships to allow us to have a global deployment of this capability on a constant basis, with a surge capacity to any one theater at a time.” To certain Russian military planners’ ears that may not sound like a limited system aimed at a primitive threat from Iran.

Because the mobile ship-based interceptors (hypothetically placed off of the U.S. East Coast ) could engage Russian warheads, Russian officials may be able claim this as an infringement on New START parity.

Missile defenses that show little promise of working well can, nevertheless, alter perceptions that the strategic balance between otherwise well-matched states is stable. Even when missile defenses reveal that they possess little, if any technical capabilities, they can still cause cautious adversaries and competitors to react as if they might work. The United States’ response to the Cold War era Soviet missile defense system was similarly overcautious.

4. Finally, certain Russian military planners may worry about the NATO EPAA missile defense system because in Phase 3, the interceptors are to be based on the SM-3 Block IIA booster. The United States has conducted research using this same type of rocket booster as the basis of a hypersonic-glide offensive strike weapon called ArcLight. Because such offensive hyper-glide weapons could fit into the very same vertical launch tubes – on the ground in Poland and Romania, or on the Aegis ships – used for the defensive interceptors, the potential exists for turning a defensive system into an offensive one, in short order. Although funding for ArcLight has been eliminated in recent years, Russian military planners may continue to worry that perhaps the project “went black” [secret], or that it may be resuscitated in the future. In fact, a recent Federal Business Opportunity (FBO) for the Department of the Navy calls for hypersonic weapons technologies that could fit into the same Mk. 41 Vertical Launch System (VLS) tubes that the SM-3 missile defense interceptors are also placed in.

To conclude, advocates of missile defense who say we need cooperation on missile defense to improve ties with Russia have the logic exactly backward: In large part, the renewed tension between Russia and the United States is about missile defense. Were we to abandon this flawed and expensive idea, our ties with Russia — and China — would naturally improve. And, in return, they could perhaps help us more with other foreign policy issues such as Iran, North Korea, and Syria. As it stands, missile defense is harming bilateral relations with Russia and poisoning the well of future arms control.

Q: (CB) Adding to the gravity of Secretary Hagel’s announcement , last week China expressed worry about Ground-Based Interceptors, the Bush administration’s missile defense initiative in Poland discarded by the Obama administration in 2009, in favor of Phase 4 of the EPAA. Why is there concern with not only the Aegis ship-based system, but also the GBIs on the West Coast?

A: (YB) Like the Russians, Chinese military analysts are also likely to assume the worst-case scenario for the system (ie. that it will work perfectly) in coming up with their counter response . Possessing a much smaller nuclear arsenal than Russia or the United States, to China, even a few interceptors can be perceived as making a dent in their deterrent forces. And I think the Chinese are likely worried about both the ship-based Aegis system as well as the West Coast GBIs.

And this concern on the part of the Chinese is nothing new. They have not been as vocal as the Russians, but it is evident they were never content with U.S. and NATO plans. For instance, the 2009 Bipartisan Strategic Posture Commission pointed out that “China may already be increasing the size of its ICBM force in response to its assessment of the U.S. missile defense program.” Such stockpile increases, if they are taking place, will probably compel India, and, in turn, Pakistan to also ramp up their nuclear weapon numbers.

The Chinese may also be looking to the future and think that U.S. defenses may encourage North Korea to field more missiles than it may originally have been intending – if and when the North Koreans make long range missiles – to make sure some get through the defense system. This would have an obvious destabilizing effect in East Asia which the Chinese would rather avoid.

Some U.S. media outlets have also said the ship-based Aegis system could be used against China’s DF-21D anti-ship missile, when the official U.S. government position has always been that the system is only intended only against North Korea (in the Pacific theater). Such mission creep could sound provocative to the Chinese, who were told that the Aegis system is not “aimed at” China.

In reality, while the Aegis system’s sensors may be able to help track the DF-21D it is unlikely that the interceptors could be easily modified to work within the atmosphere where the DF-21D’s kill vehicle travels. (It could perhaps be intercepted at apogee during the ballistic phase). A recent CRS report was quite explicit that the DF-21D is a threat which remains unaddressed in the Navy: “No Navy target program exists that adequately represents an anti-ship ballistic missile’s trajectory,’ Gilmore said in the e-mail. The Navy ‘has not budgeted for any study, development, acquisition or production’ of a DF-21D target, he said.”

Chinese concerns about U.S. missile defense systems are also a source of great uncertainty, reducing Chinese support for promoting negotiations on the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty (FMCT). China’s leaders may wish to maintain the option of future military plutonium production in response to U.S. missile defense plans.

The central conundrum of midcourse missile defense remains that while it creates incentives for adversaries and competitors of the United States to increase their missile stockpiles, it offers no credible combat capability to protect the United States or its allies from this increased weaponry.

Q: (CB) Will a new missile defense site on the East Coast protect the United States? What would be the combat effectiveness of an East Coast site against an assumed Iranian ICBM threat?

A: (GL) I don’t see any real prospect for even starting a program for interceptors such as the [East Coast site] NAS is proposing any time soon in the current budget environment, and even if they did it probably would not be available until the 2020s. The recent announcement of the deployment of additional GBI interceptors is, in my view, just cover for getting rid of the Block II Bs, and was chosen because it was relatively ($1+ billion) inexpensive and could be done quickly.

The current combat effectiveness of the GBIs against an Iranian ICBM must be expected to be low. Of course there is no current Iranian ICBM threat. However, the current GMD system shows no prospect of improved performance against any attacker that takes any serious steps to defeat it as far out in time, as plans for this system are publicly available. Whether the interceptors are based in Alaska or on the East Coast makes very little difference to their performance.

Q: (CB) There were shortcomings reported by the Defense Science Board and the National Academies regarding the radars that are part of the system. Has anything changed to improve this situation?

A: (GL) With respect to radars, the main point is that basically nothing has happened. The existing early warning radars can’t discriminate [between real warheads and decoys]. The only radar that could potentially contribute to discrimination, the SBX, has been largely mothballed.

Q: (CB) Let’s say the United States had lots of money to spend on such a system, would an East Coast site have the theoretical ability to engage Russian warheads? Regardless of whether Russia could defeat the system with decoys or countermeasures, does the system have an ability to reach or engage the warheads? In short, could such a site be a concern for Russia?

A: (YB) If you have a look at Fig 8(a) and 8(b) in the report Ted Postol and I wrote you’ll see pretty clearly why an East Coast site might be a concern for Russia, especially with faster interceptors that are proposed for that site. Now I’m not saying it necessarily should be a concern – because they can defeat the system rather easily – but it may be. Whether they object to it or not vocally depends on other factors also. For instance, such a site will obviously not be geopolitically problematic for the Russians.

Charles P. Blair is the Senior Fellow on State and Non-State Threats at the Federation of American Scientists.

Dr. Yousaf Butt, a nuclear physicist, is professor and scientist-in-residence at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. The views expressed are his own.

Dr. George N. Lewis is a senior research associate at the Judith Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies at Cornell University.

President’s Message: Reducing Catastrophic Risks: Why FAS Matters

Senator Sam Nunn has often underscored that humanity is in “a race between cooperation and catastrophe.” As co-chairman of the Nuclear Threat Initiative, he has urged greater and faster international action on reducing nuclear dangers. He has also joined with former Secretary of State George Shultz, former Secretary of Defense William Perry, and former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, a bipartisan group of senior statesmen, to put forward an agenda for taking the next steps to achieve a nuclear weapon free world. They are making progress in convincing more and more political leaders to support their initiative.

To complement their efforts, we now need a dedicated coalition of scientists, engineers, and other technically trained people to work together and devote their knowledge and skills toward reducing the risks of catastrophes. As the founders of the Federation of American Scientists knew very well from their experience serving in the Manhattan Project, humanity has within its power the capability to destroy itself. Even though there would have been survivors from a massive thermonuclear war during the Cold War, they would have envied the dead (as Soviet Chairman Nikita Khrushchev observed after the Cuban Missile Crisis) because the effects of such a war would have been catastrophic on billions of people worldwide, not just in the countries directly targeted. “Nuclear War is National Suicide,” warns a sticker pinned to my office’s bulletin board. Emblazoned with a mushroom cloud, the sticker was made by FAS more than thirty years ago.

While the likelihood of nuclear war between Russia and the United States has faded with the receding shadow of the Cold War, nuclear dangers have arguably grown even more threatening, with the race to secure vulnerable nuclear materials before they land in the hands of terrorists, the possibility of inadvertent nuclear war between Russia and the United States, the increasing nuclear arsenal of North Korea, the continuing build up of nuclear arms in India and Pakistan, the expanding latent weapons capability of Iran’s nuclear program, and the interest among some non-nuclear weapon states such as Japan and the Republic of Korea to use or continue to use plutonium in nuclear fuels. Today more than ever, the Federation of American Scientists must redouble its efforts to lessen these threats.

I am pleased to announce that FAS is nearing the conclusion of more than a yearlong strategic planning process to assess its future direction. I am very grateful to all of you who took part in the membership survey and other interviews last year. Your advice was essential to help guide us and refocus our work in what matters. In effect, we are launching a “back to the future” strategy that will replant FAS’s roots from its founding in 1945 to its new beginning in the 21st Century. That is, we will not just counter nuclear threats that stemmed from the Second World War, but we will become the organization that will provide science-based analysis and solutions

to catastrophic risks. I purposely use the word “risks” (defined as probability times consequences) to make clear that FAS will work to reduce the probability of the threats occurring as well as offer ways to mitigate massively destructive or disruptive consequences that these threats can cause.

Catastrophic threats can affect millions or perhaps billions of people through huge numbers of deaths and serious illnesses, massive economic damage, extensive and lasting harm to food, water, and energy supplies, or widespread dislocations of populations. These threats can be human-induced, such as use of biological or nuclear weapons or too much emissions of greenhouse gases, or naturally occurring, such as pandemics, massive earthquakes, tsunamis, or major asteroid collisions with earth. Moreover, new catastrophic threats could emerge with the misuse of cyber technologies, synthetic biology, or robots, to name a few possibilities.

In this renewed mission, FAS has multi-fold audiences: the scientific and engineering communities, policymakers in the executive and legislative branches of the United States and other governments, the public, and the news media. FAS will serve as the bridge between the technical communities and the policymaking community. In the coming months, we will improve our communications to these audiences and communities. For example, we will refresh FAS.org, which is a treasure trove of tens of thousands of documents, features innovative analysis and tools such as uranium enrichment and nuclear weapon effect calculators, and receives up to one million visitors monthly. But this website needs significant updating and a more user-friendly structure. We will keep you informed of the updates.

With this issue of the Public Interest Report, you will see a new look, which aims to provide a user-friendlier online magazine with articles focused on our renewed mission of science-based analysis and solutions to catastrophic risks. We very much welcome your advice about how to further improve the PIR. FAS can only do its work with members and supporters like you.

Similarly, humanity can only reduce the risks of catastrophes though cooperation. We need to break free of zero-sum mindsets and urgently come together in the spirit of cooperative games. I am heartened that one of the most popular recently released games is PandemicTM in which the players work as a team to cure four diseases before the globe becomes engulfed in a pandemic. One of the team members is a scientist. But the scientist alone does not have enough skills and powers to win the game. She needs an operation officer, a medic, a dispatcher, and a researcher.

The core belief of FAS’s founders is as relevant today as it was in 1945. Scientists and engineers have the ethical obligation to ensure that the fruits of their intellectual labor benefit humankind. I look forward to continue working with you to support that endeavor.

Charles D. Ferguson, Ph.D.

President, FAS

Invitation to Debate on Nuclear Weapons Reductions

Nuclear Debate at the Big 1800 Tonight

.By Hans M. Kristensen

Tonight I’ll be debating additional nuclear weapons reductions with former Assistant Secretary of State Stephen Rademaker at a PONI event at CSIS.

I will argue (prepared remarks here) that the United States could make more unilateral nuclear arms reductions in the future, as it has safely done in the past, as I argued in Trimming Nuclear Excess, in addition to pursuing arms control agreements. Mr. Rademaker will argue against unilateral reductions in favor of reciprocal or negotiated ones.

I suspect there will be a fair amount of overlap in the arguments but it is certainly a timely debate with the Obama administration pursuing additional reductions with Russia, the still-to-be-announced Nuclear Posture Review Implementation Study having determined that the United States can meet its national security and extended deterrence obligations with 500 fewer deployed strategic warheads, and budget cuts forcing new thinking about how many nuclear weapons and of what kind are needed.

The doors open at CSIS on 1800 K Street at 6 PM for a reception followed by the debate starting at 6:30 PM.

Document: Prepared remarks

(Still) Secret US Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Reduced

The United States has unilaterally reduced the size of its nuclear weapons stockpile by nearly 500 warheads since 2009.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The United States has quietly reduced its nuclear weapons stockpile by nearly 500 warheads since 2009. The current stockpile size represents an approximate 85-percent reduction compared with the peak size in 1967, according to information provided to FAS by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA).

The reduction is unilateral and not required by any arms control treaty. It apparently includes retirement of warheads for the last non-strategic naval nuclear weapon, the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N).

85 Versus 87

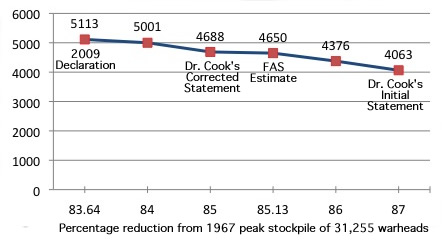

One of the interesting moments at the Deterrence Summit last week came when Dr. Donald Cook, who is NNSA’s administrator for defense programs, talked about the size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile.

At one point, Dr. Cook said that there are “roughly 5,000” warheads in the stockpile today. And then he added: “Today it’s, I’ll just say it’s a bit under about 5,000…about an 87 percent reduction” compared with the peak in 1967. (The 87 percent statements occurs 2:52:25 into the CSPAN recording).

Since the peak size of the stockpile has been declassified (31,255 warheads in 1967), an 87 percent reduction would in fact be quite a bit under 5,000 – a stockpile of 4,063 warheads, to be precise. If so, the stockpile would have shrunk by 1,050 warheads since September 2009 when the stockpile contained 5,113 warheads.

The number didn’t fit the stockpile estimate that Norris and I currently have (4,650 warheads), so I contacted Dr. Cook to double check if he meant to say 87 percent. He told me that it was an error and that the correct figure was “approximately 85% reduction.” That corresponds to a stockpile of roughly 4,688 warheads (depending on how many digits “approximately” implies), or about 38 warheads off our estimate of 4,650 warheads.

The warheads retired since 2009 apparently include the W80-0 warhead previously used on the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N). The 2010 Nuclear Posture Review decided the weapon was no longer needed, and “a very substantial number of W80-0″ warheads already have been dismantled, Dr. Cook told Congress last week. [Update 21 Mar: FY12 Pantex Performance Evaluation Report states (p.24): “All W80-0 warheads in the stockpile have been dismantled.” (Thanks Jay!)].

|