Chinese Nuclear Developments Described (and Omitted) by DOD Report

By Hans M. Kristensen

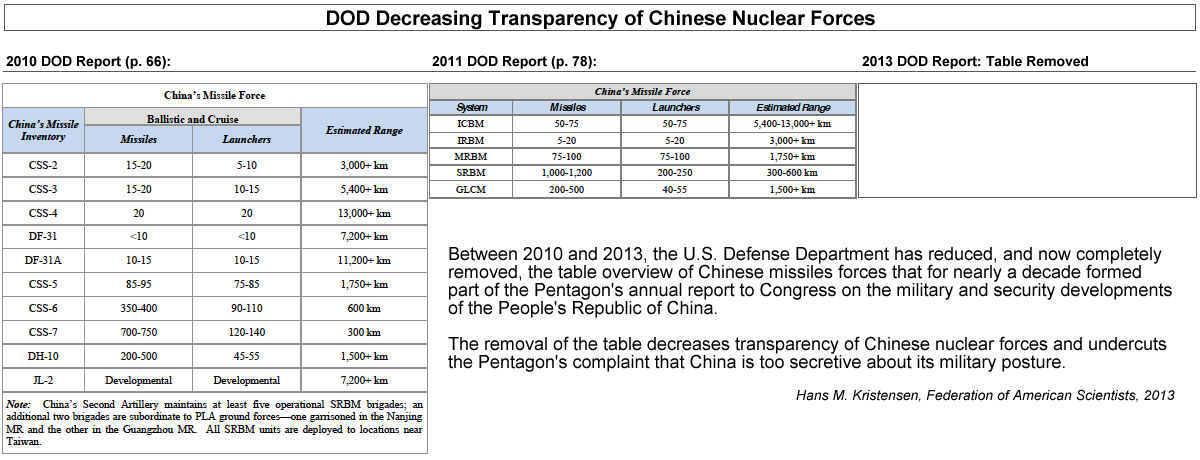

Going, going, gone! In its latest annual report to Congress on the military and security developments of the People’s Republic of China, the Pentagon has removed the last public authoritative overview of Chinese nuclear forces.

Until 2010, the annual reports included a table with a detailed breakdown of the different types of ballistic missiles that enabled the public to monitor the development of China’s nuclear modernization. In 2011, however, things began to change when a less detailed table was included that only showed overall categories of missiles. That version appeared in 2012 as well, but the 2013 report includes no table at all of China’s missile forces.

The tidbits of information left in the report indicate an ICBM force that is modernizing but leveling out and an SSBN force that is approaching functional capability.

Land-Based Nuclear Forces

DOD reports the same number of ICBMs as last year, 50-75. The Pentagon considers a missile with a range of at least 5,500 km to be an ICBM, so this number includes the DF-5A, DF-31A, DF-31 and DF-4. Of these, only the DF-5A and DF-31A can reach the continental United States.

The 50-75 ICBMs is the same number DOD has reported for the past three years, which indicates that the ICBM force level has leveled out for now. But DOD predicts that additional DF-31As will be deployed over the next two-three years.

The report also repeats the prediction from previous years that China “may also be developing” a new road-mobile ICBM that is “possible capable of” carrying MIRVed warheads. The U.S. Intelligence Community has for several decades assessed that China has a capability to develop and deploy MIRV but that it has not yet done so. One sentence in the report comes close to saying that that’s about to change with “The new generation of mobile missiles, with warheads consisting of MIRVs and penetration aids,” but the report does not confirm widespread rumors (see here and here) that a 10-warhead DF-41 ICBM was test launched last year. All appeared to feed off this article. Many MIRV reports appear to confuse warheads with decoys and penetration aids.

The report does not provide an update of nuclear medium-range missiles, except confirming that a few aging liquid-fuel DF-3As are still operational. They will likely be retired within the next few years.

As one would imagine, the new and increasingly mobile missile force requires updating the command and control system. The DOD report states that China has done so and states that “improved communications links” means that “the ICBM units now have better access to battlefield information, uninterrupted communications connecting all command echelons, and the unit commanders are able to issue orders to multiple subordinates at once, instead of serially via voice commands.”

At the same time, further increases in the number of mobile ICBMs, the DOD report states, “will force the PLA to implement more sophisticated command and control systems and processes that safeguard the integrity of nuclear release authority for a larger, more dispersed force.”

Sea-Based Nuclear Forces

The DOD report states that China has added a third Jin-class (Type 094) SSBN to its fleet and that two more are in various stages of construction. Their nuclear ballistic missile, the Julang-2, is not yet operational, however, but the report indicates that has missile program has overcome technical difficulties, completed a series of successful testing in 2012, and appears ready to reach initial operational capability in 2013.

There is no confirmation of the rumor that the JL-2 has a capability to carry multiple warheads.

The single Xia-class (Type 92) SSBN that China built back in the early 1980s has never been fully operational. It is still afloat, moored at the Jianggezhuang naval base near Qingdao in the Shandong province. The boat will likely be retired, along with its Julang-1 SLBMs, once the Jin-class SSBNs become fully operational.

Moreover, the report predicts that China within the next decade might begin construction of a new class of SSBNs, known as the Type 096. If so, that suggests that the Jin-class design may not have been considered a success.

A Jin-class (top) ballistic missile submarine and Shang-class attack submarine are seen docked at the naval base near Longpo on Hainan Island in this DigitalGlobe/GoogleEarth satellite image from June 27, 2012. Jin-class SSBN were first seen at Hainan in February 2008.

Once fully operational, the DOD report states, SSBNs based at Hainan Island “would then be able to conduct nuclear deterrence patrols.” But now China will operate the SSBN fleet remains to be seen. It might begin to mimic deterrence patrols of other nuclear weapon states, but it seems unlikely that China will begin to deploy nuclear-armed missiles on its SSBNs under normal circumstance because the Central Military Commission is unlikely to hand over nuclear warheads to the armed forces unless in an emergency.

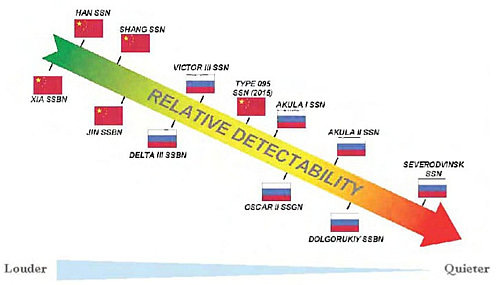

Moreover, Chinese SSBNs are relatively noisy (see graph below) and vulnerable to enemy anti-submarine capabilities, so it seems contrary to China’s core strategic objective of protecting its retaliatory nuclear capability to send some of it out to sea where it can be sunk by enemy attack submarines.

This vulnerability is compounded by the fact that Chinese SSBNs have never conducted a deterrence patrol (see below), which makes the Chinese navy woefully inexperienced in operating an SSBN effectively and safely.

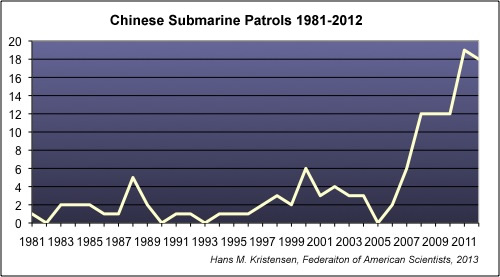

Data obtained from U.S. Naval Intelligence under the Freedom of Information Act shows that Chinese missile submarines have never conducted a deterrent patrol. The attack submarine fleet is more active, with patrols having more than quadrupled over the past decade from around four per year to approximately eighteen patrols last year (see graph).

The increase in general-purpose submarine patrols has coincided with the introduction of the Chang-class (Type 093) nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN) from 2005, but probably also reflects operations by more advanced diesel-electric submarines. The introduction of Type 093 SSNs has been slow, however, with only two in service and four improved version under construction to replace the remaining aging first-generation Han-class (Type 091) class SSNs.

Within the next decade, the DOD report predicts, China will likely begin construction of a new class of nuclear-powered attack submarines (Type 096), which might be equipped with land-attack cruise missiles.

Air-Based Nuclear Forces

The DOD report does not explicitly credit the Chinese air force with a nuclear capability but it probably has a limited secondary mission with nuclear gravity bombs. The H-6 medium-range bomber was used to carry out a dozen nuclear tests in the 1970s and 1980s.

The report states that China is modifying the H-6 to “a new variant that possesses greater range and will be armed with a long-range cruise missile.” Elsewhere the report states that H-6 upgrades “may provide the capability to carry new, longer-range cruise missiles.” So whether the H-6 upgrades involve one or more types of long-range cruise missiles is a little unclear.

So far the air-launched cruise missiles have not been credited with nuclear capability, although the ground-launched DH-10 (which is not mentioned in the DOD report) was described as “conventional or nuclear” by the Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center in 2009.

Conclusions and Implications

Chinese nuclear modernizations continue with modest pace with focus on safeguarding a retaliatory capability by replacing land-based liquid-fuel missiles with solid-fuel versions, increasing mobile ICBMs, and building a small fleet of ballistic missile submarines.

The size of the ICBM force appears to be leveling out for now, although more may be deployed in the future. And once the 36 JL-2 SLBMs on the three Jin-class SSBNs become operational, they will increase the Chinese nuclear ballistic missile force by approximately 27 percent compared with the current inventory.

Yet because older types are also being retired, the impact on the size of the total nuclear weapons stockpile so far appears to be modest. Earlier this year, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Global Affairs, Madelyn Creedon, testified before the Senate that despite China’s nuclear force modernizations, “we estimate that it has not substantially increased its nuclear warhead stockpile in the past year…” Moreover, STRATCOM Commander General Kehler last year rejected claims by some that China has hundreds or thousands more nuclear weapons than the “several hundred” estimated by the U.S. Intelligence Community.

The complete deletion of the table overview of China’s missile forces is striking because the Pentagon for years has been complaining about a lack of transparency in China’s military modernization. Ironically, this complaint was repeated when the Pentagon briefed this year’s report. Said Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for East Asia, David Helvey:

“So what – what concerns me – is the extent to which China’s military modernization occurs in – in the absence of the type of openness and transparency that others are certainly asking of China and the potential implications and consequences of that lack of transparency on the security calculations of others in the region. And so it’s that uncertainty, I think, that’s of greater concern.”

Instead of assisting Chinese nuclear secrecy, the United States should push for transparency and accountability. Authoritative overviews of Chinese nuclear force developments are important to enable the public to assess implications of China’s nuclear modernization and to counter attempts by those who use the uncertainty created by lack of information to hype the threat in order to justify excessive military spending.

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Talk At US Air Force Global Strike Command

Kristensen on the tarmac at Barksdale Air Force Base with the crew of the nuclear-capable B-52H bomber “Rolling Thunder” (61-019) from the 96th Bomb Squadron that recently flew B-52 bombers over South Korea.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Earlier this week I went to Barksdale AFB on an invitation from General Jim Kowalski at Air Force Global Strike Command to brief his Deterrence and Assurance Working Group.

Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC) is responsible for keeping U.S. strategic bombers (B-2 and B-52) and Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) combat ready. One of two B-52H wings, the 2nd Bomb Wing, is based at Barksdale AFB, as is 8th Air Force Headquarters.

Barksdale AFB has a special history because it was there, in August 2007, that a B-52 arrived from Minot AFB with six nuclear-armed Advanced Cruise Missiles strapped under its wings without anyone knowing about it.

It was a great visit. The staff did a superb job hosting me, and Gen. Kowalski and his wife Julie were the most generous hosts. But they sure kept me busy:

After getting woken up by the base bugle, I was brought to base headquarters for a one-on-one briefing by Gen. Kowalski on the mission of AFGSC. He told me about the capabilities of the command, the nuclear forces of the United States and other nuclear weapon states, nuclear modernization, as well as budget and costs issues.

After a swing by the base museum and a lunch with Gen. Kowalski and 18 members of the senior leadership, the General Larry Welch briefing room filled up with an additional 34 military and civilian officials for my talk.

In my talk I advocated further reductions of nuclear weapons, arguing that deterrence and assurance could be sustained at significantly lower levels. I pointed to the very different nuclear forces of different countries as examples of other countries ensuring their security with much smaller nuclear forces. And I predicted that new presidential guidance would probably reduce the force level further in the near future. Despite obvious disagreements, the discussion was courteous.

After the talk, they brought me out on the tarmac where the crew of a nuclear-capable B-52H from the 96th Bomb Squadron gave me a briefing and a tour of the inside. Its nuclear weapons are not stored at Barksdale AFB but up at Minot AFB. The 96th Bomb Squadron returned in April from a six-month deployment to Guam, during which some of the B-52Hs overflew the Korean Peninsula to deter North Korea and assure South Korea.

Next stop was the B-52 simulator where my co-pilot gave a few instructions, after which we powered up the six engines and took off, flew a brief tour over northern Louisiana, and returned to base (without crashing).

A cozy dinner in the beautiful home of Mr. and Mrs. Kowalski ended what had been an exciting visit with fascinating discussions with some of the men and women who operate America’s nuclear forces.

Download: Prepared remarks to U.S. Air For Global Strike Command Deterrence and Assurance Working Group

Russian SSBN Fleet: Modernizing But Not Sailing Much

The second Borei-class SSBN (Alexander Nevsky) is fitting out at the Severodvinsk Naval Shipyard in northern Russia. Six of its 16 missile tubes are open on this August 2011 satellite image by DigitalGlobe/GoogleEarth.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Russian ballistic missile submarine fleet is being modernized but conducting so few deterrent patrols that each submarine crew cannot be certain to get out of port even once a year.

During 2012, according to data obtained from U.S. Naval Intelligence under the Freedom of Information Act, the entire Russian fleet of nine ballistic missile submarines only sailed on five deterrent patrols.

The patrol level is barely enough to maintain one missile submarine on patrol at any given time.

The ballistic missile submarine force is in the middle of an important modernization. Over the next decade or so, all remaining Soviet-era ballistic missile submarines and their two types of sea-launched ballistic missiles will be replaced with a new submarine armed with a new missile (see also our latest Nuclear Notebook on Russian nuclear forces).

The new fleet will carry more nuclear warheads than the one it replaces, however, because the Russian military is trying to maintain parity with the larger U.S. nuclear arsenal.

Sluggish Deterrent Patrols

The operational tempo of the Russian SSBN fleet – measured in the number of deterrent patrol conducted each year – has declined significantly – actually plummeted – since the end of the Cold War.

At their peak in 1984 – the year after the Russian military became convinced that the NATO exercise Able Archer was in fact disguised preparations for a nuclear first strike against the Soviet Union, Russian SSBNs carried out 102 patrols. Under Mikhail Gorbachev, operations quickly declined in the second half of the 1980s. But even as the Warsaw Pact collapsed and the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the fleet was able to muster a slight comeback in 1990.

As the Cold War officially ended in 1990, the Soviet Union dissolved and Russia descended into financial recession, the SSBN force increasingly stayed in port until in 2002, when no deterrent patrols were conducted all.

Since then, the performance has been a mixed bag. After a slight whiff of new life with 10 patrols in 2008 (up from 3 in 2007), the number of SSBN patrols has declined again to around five in 2012.

The recent decline contrasts with the Russian Navy’s declaration last year that it would resume continuous deterrent patrols from mid-2012. Assuming the five patrols occurred throughout the year and not just in the last six months, the fleet would have had a hard time maintaining a continuous at-sea presence with only five patrols. Theoretically, it could be done if each patrol lasted an average of 73 days. That is how long a U.S. SSBN deploys on a good day. But Russian SSBNs are thought to do shorter patrols, probably 40-60 days each, in which case most of the five patrols would have had to occur between July and December to maintain continuous patrol from mid-2012.

Even if the navy were able to squeeze a more or less continuous at-sea presence out of the five patrols, it would at best have consisted of a single SSBN – not much for a fleet of nine submarines or demonstrating a convincing secure retaliatory capability.

Perhaps more significantly, the five deterrent patrols conducted in 2012 are not enough for each SSBN in the fleet to be able to conduct even one patrol a year. The five patrols by nine SSBNs indicate that only five or less submarines are active. That means that submarine crews do not get much hands-on training in how to operate the SSBNs so they actually have a chance to survive and provide a secure retaliatory strike capability in a crisis. Crews probably compensate for this by practicing alert operations at pier-side at their bases.

Unlike U.S. SSBNs, which can patrol essentially with impunity in the open oceans, Russian deterrent patrols are thought to take place in “strategic bastions” relatively close to Russia where the SSBNs can be protected by the Russian navy against the U.S. and British attack submarines that probably occasionally monitor their potential targets.

The Russian navy remembers all too well the 1980s when the aggressive U.S. Maritime Strategy envisioned using attack submarines to hunt down and destroy Soviet SSBNs early on in a conflict, a highly controversial strategy [see here and here] that could likely have triggered escalation to strategic nuclear war. Hunting Russian SSBNs is no longer a primary mission for U.S. attack submarines, but it is probably still part of the mission package and one that Russian planners cannot afford to ignore. As a result, Russian SSBNs probably continue to patrol in the areas used in the late-1980s and early-1990s (see map) to provide maximum protection.

Force Structure

Russia currently operates 10 ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), of which three Delta IIIs based in the Pacific are outdated and six Delta IVs based in the Barents Sea have recently been refurbished to serve for another decade or so. The 10th SSBN added in January 2013 is the first of a new type of Borei-class SSBNs that are scheduled to replace all Deltas by the mid/late-2020s.

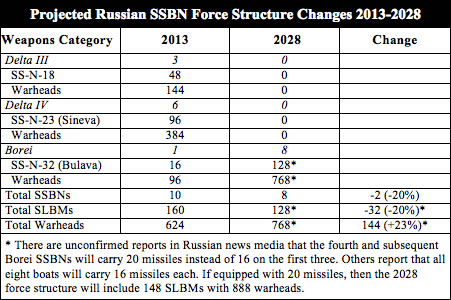

The first Borei-class (Project 955) SSBN, Yuri Dolgoruki, entered service after more than 15 years of design and construction, marking the first time in 25 years that the Russian Navy had commissioned a new SSBN. A second Borei has been launched and a third is under construction. Russia has announced plans to build a total of eight Boreis. Each Borei is equipped with 16 SS-N-32 (Bulava) SLBMs, a missile that Russia has declared can carry up to six warheads.

The fourth and subsequent Borei-class SSBNs will be of an improved design, known as Borei-II or Project 955A). Russian news media is full of rumors that the improved Boreis will be equipped with 20 SLBMs instead of 16 on each of the first three boats. Some Russian officials dispute that, saying all Boreis will be equipped with 16 missiles.

This force structure plan has implications for Russia’s nuclear posture and strategic priorities. The replacement of the Delta SSBNs with eight Borei SSBNs will reduce the size of the Russian SSBN fleet and the number of SLBMs, but result in a 23-percent increase in the number of sea-based warheads because the SS-N-32 carries more warheads than the SS-N-18 and SS-N-23 SLBMs it replaces.

In other words, Russia will be placing more eggs in fewer baskets at sea, which increases the importance of each SSBN – something strategists say is bad for crisis stability.

Conclusions and Implications

The Russian SSBN force is in the middle of a transition from Soviet-era weapons to a smaller but more warhead-heavy fleet of new submarines.

This means that the SSBN fleet will carry a growing portion of Russia’s strategic missile warheads – up from about a third today to nearly half by the mid-2020s.

The trend of increased warhead loading on sea-launched ballistic missiles is similar to the development on land where reduction of the Russian ICBM force will result in a greater portion of the remaining force being equipped with multiple warheads.

This is perhaps the most dominant trend of Russia’s nuclear forces today: fewer launchers but each carrying more warheads. Not that Russia will have more total nuclear warheads than before (their arsenal is declining), but that military planners have fallen for the temptation to place more nuclear eggs in each basket.

They appear to do so to compensate againt the larger U.S. nuclear missile force and its significant reserve of additional warheads. But it would be helpful if the Russian government would declare how many Borei-class SSBNs it plans to build in total and limit the number of missiles on each to 16.

The Russian modernization is motivating Cold Warriors in the U.S. Congress to argue that the United States should not reduce but modernize its nuclear forces. They are wrong for many reasons, not least because the two postures are very different.

The U.S. SSBN fleet is more modern with another 15 service years left in it, and it carries many more missiles that are much more reliable with more warheads. The U.S. could in fact easily reduce its SSBN fleet to ten boats, perhaps fewer.

Moreover, in contrast with U.S. SSBN operations, where each operational submarine conducts an average of 2-3 patrols each year, Russian SSBN crews do not get a lot of operational training with an average of less than one patrol per submarine per year.

Rather than opposing further reductions, U.S. lawmakers should support limitations on the growing asymmetry between U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear forces – an asymmetry that is significantly in the U.S. advantage – to help limit further concentration of nuclear warheads on Russia’s declining numbers of strategic missiles. That would actually help the national security interests of all.

See also: Russian nuclear forces, 2013

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Declining Deterrent Patrols Indicate Too Many SSBNs

By Hans M. Kristensen

Does the U.S. Navy have more ballistic missile submarines than it needs? Dramatic reductions in deterrent patrols – but not submarines – suggest so.

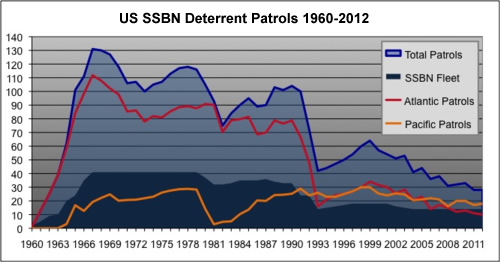

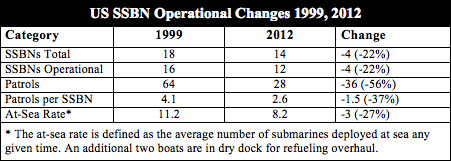

Over the past thirteen years, the number of deterrent patrols conducted each year by U.S. ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) has declined by more than half.

During most of the same period, the size of the SSBN fleet has remained relatively steady at 14 boats, after four were retired in 2001-2003. Yet the decline in deterrent patrols has continued.

As a result, each SSBN now conducts one deterrent patrol less per year, in average, than it did a decade ago. At any given time, there are fewer SSBNs on deterrent patrol today than in the early-1960s when SSBN patrols first began.

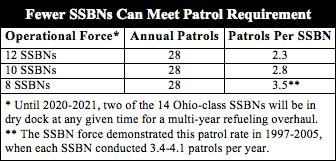

The development indicates that the U.S. Navy may currently be operating more SSBNs than are needed for U.S. security needs, and that the current patrol rate could in fact be maintained with fewer submarines.

This also raises questions about the navy’s plan to build a new class of 12 SSBNs to replace the current class of 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. Fewer than 12 submarines would be able to meet the current deterrent patrol level and the number of patrols may even decline further in the future.

Declining Deterrent Patrols

Since 1999, the number of deterrent patrols the U.S. SSBN fleet conducts each year has declined by more than 56 percent from 64 patrols in 1999 to 28 in 2012. The decline has reduced the number of annual patrols to the lowest level since 1962 (see graph).

The decline has been most significant in the Atlantic where the number of annual patrols has dropped from 34 in 1999 to only 10 in 2012, a decline that was expected because King’s Bay has lost four SSBNs since 1999 and now operates only six boats.

But even in the Pacific, where most SSBNs are now based and the fleet has remained steady at eight boats, the decline has also been significant, from 30 patrols in 1999 to 18 patrols in 2012.

Effects on Operational Tempo

Ohio-class SSBNs were optimized for long deterrent patrols and each boat has two crews (Gold and Blue) to enable the submarines to spend as little time in port as possible.

Yet each SSBN now spends less than half of the year on deterrent patrol – the purpose for which it was built – compared with 60-70 percent a decade ago. The decline means that each submarine today conducts an average of 2.3 deterrence patrols per year, down from 4.1 a decade ago. In fact, today’s patrol rate is the lowest ever for the Ohio-class SSBNs.

Each patrol lasts an average of 70 days but the duration can fluctuate significantly, from as little as 30 days to more than 100 days, due to targeting requirements and technical issues.

The longest-ever known patrol conducted by a U.S. SSBN took place in 2010 when the USS Maine (SSBN-741) deployed continuously for 105 days between August and December.

Patrol Rate Versus At-Sea Rate

The decline in deterrent patrols should theoretically result in 5-6 SSBNs (36-43 percent) deployed at any given time and the remaining 8-9 boats visible in port. But the patrol rate does not match the at-sea rate; there are more SSBNs at sea than on patrol.

Between 1998 and 2001, the U.S. Navy periodically disclosed how many SSBNs were at sea at any given time: an average of 11 boats out of a fleet of 18 SSBNs (about 61 percent). The terrorist attacks in September 2001 put an end to that transparency and subsequent requests to the navy for the information were denied.

Yet high-resolution commercial satellite images have since become widely available to the general public via Google Earth and other sources. Examination of more than two dozen satellite images from 1993-2012 shows that an average of ten SSBNs (71 percent) are normally absent from the two bases. Two of those SSBNs are in dry dock for refueling while the remaining eight (57 percent) are deployed at sea.

So why doesn’t the patrol rate not match the at-sea rate? The reason is that deterrent patrols are not the only thing that SSBNs do. Between patrols and maintenance, each submarine deploys on sea-trials, midshipmen cruises and exercises. Yet the decline in deterrent patrols means that SSBNs are now doing more of the other things than they did a decade ago.

Fewer SSBNs Can Do The Job

The dramatic decline in deterrent patrols over the past decade suggests that the U.S. Navy can meet its deterrence requirements with fewer SSBNs than the 14 boats it currently operates. In fact, if each SSBN conducted as many patrols as a decade ago, no more than eight operational SSBNs would be needed to conduct the 28 deterrent patrols required today. With two additional SSBNs in refueling overhaul at any given time, the fleet could be reduced from 14 to 10 boats, saving millions of dollars in operational, maintenance, personnel, and inspections.

Even if the navy needed to retain an additional two SSBNs as a couching against technical problems, the fleet could probably be reduced to 12 boats. Indeed, the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review forecasts such a reduction:

Depending on future force structure assessments, and on how remaining SSBNs age in the coming years, the United States will consider reducing from 14 to 12 Ohio-class submarines in the second half of this decade. This decision will not affect the number of deployed nuclear warheads on SSBNs.

The reason a reduction of two submarines would not affect the number of deployed nuclear warheads on SSBNs is that the two “reduced” SSBNs are the ones that are not deployed but in dry dock for refueling at any given time. The last of those multi-year refueling overhauls is scheduled for the end of this decade, so the NPR projection appears to make a virtue out of necessity. Indeed, unless the two submarines are retired, the navy would actually operate 14 deployed SSBNs during most of the 2020s, or more than is required for national security.

The navy is planning a new generation of 12 SSBNs to replace the current 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. The new submarine will have a new reactor core that can last the entire life of the ship; no multi-year refueling overhaul will be needed (individual submarines will still need to go into dry dock for shorter periods for maintenance and upgrades). The new SSBNs will also be equipped with a new electrical drive and probably be significantly quieter than the Ohio-class. These factors will allow additional reductions.

Moreover, the next-generation SSBNs will only carry 16 missiles each, down from 24 today and 20 by 2018. The first new SSBN will not deploy on patrol until 2031 but it nonetheless indicates that U.S. Strategic Command has already determined that there are 30 percent too many sea-launched ballistic missiles. “The Milestone A decision [12 SSBNs with 16 missiles each] did not assume any specific changes to targeting or employment guidance,” STRATCOM commander Robert Kehler testified before Congress in November 2011. If so, why continue to deploy with the extra missiles for another two decades?

The eight SSBNs that are currently at sea carry 192 missiles with an estimated 860 warheads. Of those, four-five SSBNs with 96-120 missiles and 430-540 warheads are on alert holding targets at risk in Russia, China and North Korea. Eight next-generation SSBNs could carry the same number of warheads on 128 missiles by increasing the warhead loading on each missile. But by 2031, nearly two decades from now, the targeting requirement is likely to be lower than today.

Conclusions and Implications

The significant reduction in SSBN deterrent patrols over the past decade suggests that the U.S. Navy currently operates more SSBNs than are needed.

Compared with a decade ago, each submarine is doing less of what it was designed to do – conducting deterrent patrol with ready nuclear weapons – and spending more time in port and on exercises.

The declining deterrent patrols, combined with a decision to reduce the number of sea-launched ballistic missiles by a third over the next two decades without reduced targeting requirements, indicate that the current SSBN posture is bloated and in excess of national security needs.

The navy could easily cut the SSBN fleet from 14 to 12 boats now and reduce the requirement for the next-generation SSBN from 12 to 10 boats and save billions of dollars in the process.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

PREPCOM Nuclear Weapons De-Alerting Briefing

By Hans M. Kristensen

Greetings from Geneva! I’m at the Palais des Nations for the second Preparatory Committee (PREPCOM) meeting for the 2015 Review Conference of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). I was invited by the Swiss and New Zealand UN Missions to brief our report Reducing Alert Rates of Nuclear Weapons.

With me on the panel was Richard Garwin, an FAS board member who for more than five decades has advised U.S. governments on nuclear weapons and other issues, and Gareth Evans, former Australian Foreign Minister and now Chancellor of the Australian National University.

The panel was co-chaired by Ambassador H.E. Dell Higgie, the head of the New Zealand UN Mission and Permanent Representative to the United Nations and Conference on Disarmament, and Ambassador Benno Laggner, the head of the Swiss Foreign Ministry’s Division for Security Policy and Ambassador for Nuclear Disarmament and Non-Proliferation. Switzerland and New Zealand have for several years spearheaded efforts in the United Nations to reduce the alert level of nuclear weapons.

I wrote the de-alerting report together with Matthew McKinzie who directs the nuclear program at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Click to download my briefing slides (7.6 MB) and prepared remarks.

B-2 Stealth Bomber To Carry New Nuclear Cruise Missile

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. Air Force plans to arm the B-2A stealth bomber with a new nuclear cruise missile that is in the early stages of development, according to Air Force officials and budget documents.

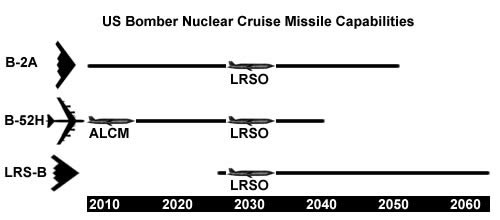

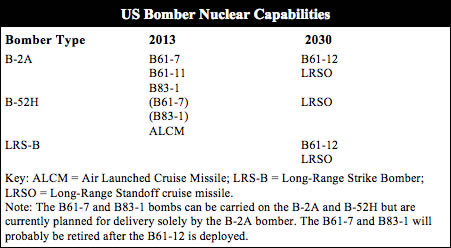

The B-2A bomber, which is designed to slip through air defenses undetected, does not currently have a capability to deliver nuclear cruise missiles, a role reserved exclusively for B-52H bombers.

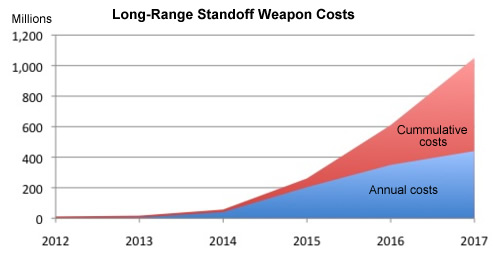

Under the Air Force’s plans, however, the new nuclear cruise missile – known as the Long-Range Standoff Weapon – will arm three nuclear bombers: the B-2A, the B-52H, and the next-generation Long-Range Strike Bomber.

Recent Statements

The disclosure that the new nuclear cruise missile will be carried on the B-2A, B-52H, as well as the next generation bomber has emerged in recent Air Force testimony to Congress, the Air Force’s FY2014 budget request, and in a little notice interview in Air Force Magazine.

Maj. Gen. Garrett Harencak, assistant chief of staff for Air Force strategic deterrence and nuclear integration, informed Congress last week that the Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) nuclear cruise missile “will be designed at its outset to be compatible with B-52, B-2, and the LRS-B” (Long-Range Strike-Bomber).

Lieutenant General James Kowalski, the commander of Air Force Global Strike Command, confirmed: “The LRSO will be the follow-on to the aging ALCM and will be compatible with the B-52, B-2 and LRS-B.”

The Air Force budget request for FY2014 reveals that integration on the B-2 is already underway as part of a program known as Flexible Strike:

B-2 armament upgrades integrate new and/or advanced weapons on the B-2 to address a wider array of target sets, to include moving targets, and hardened, deeply buried targets. The Flexible Strike Phase 1 program — formerly known as Stores Management Operational Flight Program re-host — will recombine and rehost the current B-2 stores management software onto a new integrated processor, providing the processing and bandwidth to handle advanced digital weapons such as B61-12 or Long Range Stand Off (LRSO).

Production and fielding of the Flexible Strike Phase 1 program is planned for FY2016-FY2017, in time to receive the new guided B61-12 bomb in 2019 and the LRSO cruise missile in the mid/late-2020s.

An Expensive New Nuclear Weapon

In the public debate about the cost of nuclear weapons modernizations, it is often said that the new long-range strike bomber is not a significant nuclear cost because most of its mission is non-nuclear. But that ignores the expensive nuclear payloads (B61-12 and LRSO) that are intended to arm the new bomber.

The full cost of the new nuclear cruise missile is not known yet, because it will not become operational until the mid/late-2020s. But the budget projections in the FY2014 budget request indicate that it will be a very expensive weapon system.

Over the next five years alone, design and development costs for the missile are expected to reach more than $1 billion. Costs will presumably continue to accumulate significantly through the mid/late-2020s as full-scale production and delivery of the weapon get underway.

In addition to the cost of the missile itself, the production of the nuclear warhead will add even more. Rather than a new warhead, the Air Force plans to use a life-extended version of an existing warhead: W80-1, W84, or the B61. If other life-extension programs are any indication, then the LRSO warhead program can be expected to cost several billion dollars.

The Mission

The B-2A bomber is designed to penetrate air defenses undetected. So why would the Air Force want to add a nuclear cruise missile to its mission? The answer appears to be that expected improvements in enemy air defense systems by 2030 will make the stealth bomber less stealthy and that a standoff capability therefore is needed for the nuclear strike mission.

When deployed on the B-2A, the LRSO will give the stealth bombers a nuclear standoff capability to carry out missions in heavy air defense environments, according to Billy Mullins, the associated director of strategic deterrence and nuclear integration on the Air Staff.

But that doesn’t quite explain why the Air Force has decided to make the new cruise missile compatible with all three bombers. After all, the B-52H already provides a standoff capability. Perhaps the LRSO will be dual-capable (although this has not been stated) or that the Air Force has simply decided to add a new nuclear cruise missile to all three bombers to provide maximum flexibility.

The new nuclear cruise missile will probably have extended range and stealth features similar to or better than the Advanced Cruise Missile (ACM) that the Air Force retired in 2007. The Air Force states that LRSO “will be capable of penetrating and surviving advanced Integrated Air Defense Systems (IADS) from significant stand off range to prosecute strategic targets in support of the Air Force’s global attack capability and strategic deterrence core function.”

Expanding Nuclear Capabilities

Since the B-2A does not currently carry nuclear cruise missiles, which are exclusively for B-52H bombers, but only gravity bombs (B61-7, B61-11, and B83-1), adding the LRSO will significantly increase the military capability of the B-2A weapon system.

Moreover, adding LRSO capability to all three bombers would be a significant expansion of the nuclear cruise missile capacity of the U.S. bomber fleet. Currently, some 528 ALCMs are assigned to 44 B-52H bombers in four squadrons of the 2nd and 5th Bomb Wings. In the future, also the 509th Bomb Wing at Whiteman AFB would also receive nuclear cruise missiles, as would the bases that receive the next-generation bomber.

Most important in term of capability, perhaps, is the transition of nuclear cruise missiles onto stealth platforms (B-2A and LRS-B) that have a much better penetration capability than the current cruise missile carrier (B-52H). This will significantly change where and when in a conflicts nuclear cruise missiles can be used, an enhancement that will be boosted even further by the fact that the LRSO cruise missile probably will be more advanced than the ALCM it replaces.

It seems a bit strange, though, to spend money adding LRSO capability to the B-52H because that bomber is scheduled to retain the ALCM to 2030 and retire only 10 years later. The ALCM is currently undergoing refurbishment to ensure that it can remain in service through the 2020s.

Overall, the nuclear capability of the bomber force is expected to change significantly over the next couple of decades as older weapons are retired and new ones added. In addition to the new LRSO, this includes the new guided B61-12 bomb and the possible retirement of the B61-7 and B83-1 bombs.

Eventually, both the B-2A and B-52H (as well as the non-nuclear B-1B) will be replaced by a fleet of 100 Long-Range Strike Bombers. Probably not all of them will be nuclear-capable, though, but perhaps half equipped with the B61-12 and LRSO nuclear weapons.

Implications and Recommendations

The implications of adding nuclear cruise missile capability to the B-2A stealth bomber are many. They include improved military capabilities, extensive costs, and the international perception of what U.S. nuclear arms control policy is in the 21st century.

If one believes that a nuclear cruise missile is still needed, a better and less expensive alternative would be to only add LRSO capability to the next-generation bomber and phase out the nuclear capability of B-52H when the current ALCM retires around 2030.

Either way, deploying an improved nuclear cruise missile on improved stealthy bombers appears to challenge the Obama administration’s promise to reduce the role of nuclear weapons and not to add military capabilities during life-extension programs.

The United States is not alone in the continued modernization of nuclear weapons. Russia is also building a new nuclear cruise missile for its bombers, and China is adding cruise missiles to some of its intermediate-range bomber (although there is no indication yet that they are nuclear). France has just introduced a new nuclear cruise missile on its fighter-bombers, and Pakistan is working on two nuclear cruise missiles for its aircraft.

These are only a fraction of the nuclear modernizations underway in all the nuclear weapons states. All hold speeches about ending nuclear arms competition, reducing the numbers and role of nuclear weapons, and pursuing a world free of nuclear weapons, yet all continue to do what they have always done: building and deploying new nuclear weapons.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

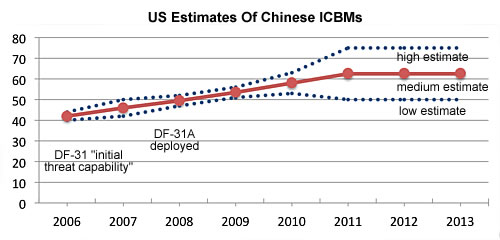

Chinese ICBM Force Leveling Out?

By Hans M. Kristensen

The size of China’s intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) force appears to be leveling out instead of increasing.

During Thursday’s Senate Armed Services Committee hearing on Current and Future Worldwide Threats, Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) director Lieutenant General Michael T. Flynn told the lawmakers:

China’s nuclear arsenal currently consists of approximately 50-75 ICBMs, including the silo-based CSS-4 (DF-5); the solid-fueled, road-mobile CSS-10 Mod 1 and 2 (DF-31 and DF-31A); and the more limited CSS-3 (DF-3) [sic*].

The force level of 50-75 ICBMs is the same as the U.S. Defense Department reported in 2012 and 2011, slightly up from a medium estimate of 55-65 ICBMs reported in 2010 and rising since the DF-31 and DF-31A first started deploying in 2006-2008. But instead of continuing to increase, the force level estimate has been steady for the past three years at a medium estimate of about 63 ICBMs.

Of the 50-75 ICBMs reported for the past three years, “less than 50” can reach the continental United States, according to DIA. Twenty of those are the silo-based DF-5A. That means that China has deployed fewer than 30 DF-31As, six years after it first started fielding the new missile. DOD stopped providing detailed breakdowns of the Chinese missile force in 2011, but the actual DF-31A number might only be around 20 (2-3 brigades) because the total ICBM estimate also includes DF-4 and DF-31, neither of which can reach the continental United States from their deployment areas in China.

This year’s DIA assessment does not include the prediction from previous years that the number of Chinese ICBMs that can strike the continental United States “probably will more than double…by 2025” to around 100 missiles. This estimate has continued to slide. In 2001 CIA predicted deployment of 75-100 ICBMs “deployed primarily against the United States” by 2015, a prediction that seems in doubt if the the current trend continues.

This year’s DIA threat assessment is also interesting because it doesn’t mention the fabled DF-41, a possible MIRVed ICBM that was rumored to have been test-launched in August 2012. Nor are any of the other new potential launchers identified.

Finally, introduction of China’s new Jin-class SSBN continues to slide; DIA projects the ballistic missile submarine “may reach initial operational capability around 2014,” or four-seven years later than the intelligence community predicted in 2006. Apparently, there have been problems with the Julang-2 missile.

* Note: The designation “DF-3” for the CSS-3 is a typo. It should have been DF-4, for the ageing 5,400-km liquid-fueled ICBM. The DF-3 is an intermediate-range, liquid-fueled ballistic missile that is being retired. Neither the DF-3 nor the DF-21, a more modern medium-range ballistic missile, is mentioned in the testimony.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Better Understanding North Korea: Q&A with Seven East Asian Experts, Part 2

Editor’s Note: This is the second of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Editor’s Note: This is the second of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked seven individuals who are experts in East Asia about the the recent escalation in tensions on the Korean Peninsula. Is North Korea’s recent success with its nuclear test and satellite launch evidence that it is maturing? Is there trepidation in Japan over the perceived threat of North Korea attacking Japan with a nuclear weapon? Has North Korea mastered re-entry vehicle (RV) technology? Is there any plausible way to de-nuclearize North Korea?

This is the second part of the Q&A, featuring Dr. Yousaf Butt, Dr. Jacques Hymans and Ms. Masako Toki. Read the first part here. (more…)

Better Understanding North Korea: Q&A with Seven East Asian Experts, Part 1

Editor’s Note: This is the first of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Editor’s Note: This is the first of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked seven individuals who are experts in East Asia about the the recent escalation in tensions on the Korean Peninsula. Is North Korea serious about their threats and are we on the brink of war? What influence does China exert over DPRK, and what influence is China wiling to exert over the DPRK? How does the increase in tension affect South Korean President Park Guen-he’s political agenda?

This is the first part of the Q&A featuring Dr. Ted Galen Carpenter, Dr. Balbina Hwang, Ms. Duyeon Kim and Dr. Leon Sigal. Read part two here.

$1 Billion for a Nuclear Bomb Tail

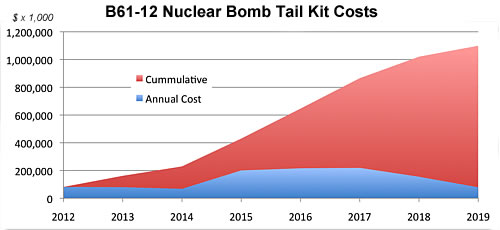

The U.S. Air Force plans to spend more than $1 billion on developing a guided tailkit to increase the accuracy of the B61 nuclear bomb.

The cost is detailed (to some extent) in the Air Force’s budget request for FY2014, which shows development and engineering through FY2014 and full-scaled production starting in FY2015.

The annual costs increase by nearly 200 percent from $67.9 million in FY2014 to more than $200 million in FY2015. The high cost level will be retained for three years until the project decreases after production ceases in FY2018. Some additional funding is needed after that to complete the integration and certification on (see graph).

Production of the guided tailkit is intended to match completion of the first new B61-12 bomb in 2019, a program that is estimated to cost more than $10 billion. Although the number is a secret, it is thought that the U.S. plans to produce roughly 400 B61-12s.

The expensive guided tailkit is needed, advocates claim, to make it possible to use the 50-kiloton nuclear explosive package from the tactical B61-4 bomb in the new B61-12 against targets that today require the 360-kiloton strategic B61-7 bomb. By increasing accuracy, the B61-12 becomes more useable because it significantly reduces the amount of radioactive fallout created in an attack.

Once deployed in Europe, the B61-12 will also be able to hold at risk targets that the B61-3 and B61-4 bombs currently deployed in Belgium, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, and Turkey cannot target.

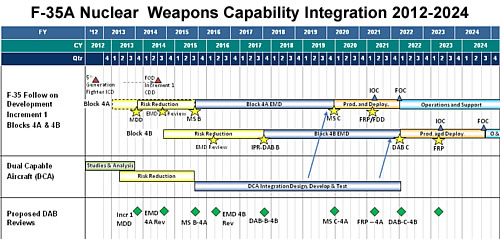

The B61-12 program will maintain compatibility on all five current B61-capable aircraft (B-2A, B-52H, F-16, F-15E and PA 200). In 2015, integration, design and testing will begin on the new stealthy F-35A Joint Strike Fighter. The Air Force budget request shows that B61-12 integration is scheduled for Block 4A and Block 4B aircraft in 2015-2021 with full operational capability in 2022 – three years after the first B61-12 is scheduled to be delivered (see table).

The combination of the new and more accurate guided B61-12 on the stealthy F-35A will significantly increase the capability of the U.S. non-strategic nuclear posture in Europe. This development is out of tune with U.S. and NATO pledges to reduce the role and reliance on nuclear weapons, and will make it a lot easier for hardliners in the Russian military to reject reductions of Russia’s larger inventory of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

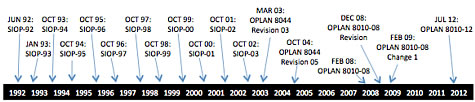

US Nuclear War Plan Updated Amidst Nuclear Policy Review

At the same time the White House is finishing a review of nuclear weapons policy, U.S. Strategic Command has quietly put into effect a new strategic nuclear war plan.

The new plan, which entered into effect in July 2012, is called OPLAN 8010-12 Strategic Deterrence and Force Employment. It replaces an earlier plan from 2008, that was revised in 2009.

A copy of the front page of OPLAN 8010-12 was obtained from U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) under the Freedom of Information Act.

OPLAN 8010-12 is the first strategic nuclear war plan update made since the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review in 2010. The administration has completed another review of nuclear targeting policy but not yet issued new presidential guidance, so the new war plan probably does not incorporate changes resulting from the review.

Triggering Plan Changes

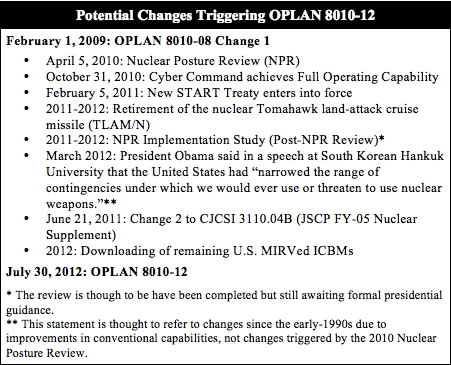

Details of OPLAN 8010-12 are highly classified and it is yet unclear why a new plan has been issued at this point instead of awaiting the results of the administration’s targeting review. Minor adjustments are made to war plans all the time but new plan numbers are thought to reflect more significant changes.

Plan updates can be triggered by several factors: changes in the adversaries that are targeted by the plan; changes to the U.S. nuclear force structure (introduction, modification, or retirement of nuclear weapon systems); or promulgation of new military or political guidance. Since the previous plan change in 2009, several important developments have occurred that could potentially have triggered production of OPLAN 8010-12 (see table).

The formal reason for the new plan was probably the update of the Nuclear Supplement to the Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan (CJCSI 3110.04B) that was issued by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in June 2011. The document, known as JSCP-N (formerly Annex C), provides nuclear planning guidance to combatant commanders in accordance with the Policy Guidance for the Employment of Nuclear Weapons (NUWEP) issued by the Secretary of Defense. This probably eliminates strike scenarios involving the recently retired nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N).

Over the same time period, the number of Russian ICBMs declined by approximately 80 missiles, most of them silo-based SS-18 and SS-19 missiles, a change that potentially would allow a reduction of at least 160 warheads from the U.S. war plan.

Plan Context

OPLAN 8010-12 is the nuclear combat employment portion (known as SIOP during the Cold War) of a wider plan also known as OPLAN 8010 (but without the update year). OPLAN 8010 is a “base plan” with annexes, one of which is OPLAN 8010-12. The annexes consist of plans for different elements of national power that span the entire spetrum of STRATCOM missions: nuclear forces; conventional strike options; non-kinetic (incuding cyber operaitons); misssile defense; intelligence, surveillance and reconnaisance; and counter-WMD.

The base plan (OPLAN 8010) is thought to be directed against six potential adversaries: Russia, China, North Korea, Iran, Syria, and WMD attacks by non-state actors.

OPLAN 8010-12 replaces the previous nuclear war plan from 2008 (OPLAN 8010-08), which was most recently updated in February 2009. The current plan is the 18th major plan update since the end of the Cold War (see table).

OPLAN 8010-12 is produced, maintained, and – if so ordered by the president – executed by the Joint Functional Component Command for Global Strike (JFCC-GS), a 430-people unit located at STRATCOM at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska. JFCC-GS is responsible for not only nuclear plans but for the full spectrum of kinetic (nuclear and conventional) and non-kinetic effects.

The Name Game

The new plan has a new name: Strategic Deterrence and Force Employment. The previous plan from 2009 was called Strategic Deterrence and Global Strike, changed from the original Global Deterrence and Strike in 2008.

- OPLAN 8010-08 Revision (December 1, 2008): Global Deterrence and Strike

- OPLAN 8010-08 Change 1 (February 1, 2009): Strategic Deterrence and Global Strike

- OPLAN 8010-12 (July 30, 2012): Strategic Deterrence and Force Employment

Three names in five years indicate a plan in evolution. The frequent name changes probably reflect an ongoing search for a name that more accurately captures the essense of the plan. Global Strike might have caused confusion with the non-nuclear Prompt Global Strike mission.

Guiding Further Reductions

As mentioned above, the Obama administration has completed an internal review of U.S. nuclear targeting policy, but has yet to issue formal presidential guidance to the military for how this will affect future revisions of OPLAN 8010-12. Yet indications are that important changes might be forthcoming.

While defense hawks lament the administration’s intension to reduce U.S. (and Russian) nuclear forces, the military has already concluded that nuclear forces can be reduced without undermining national or extended deterrence commitments:

- The Pentagon’s February 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review concluded that “new, tailored, regional deterrence architectures…make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.”

- The Pentagon’s February 2010 Ballistic Missile Defense Review stated: “Against nuclear-armed states, regional deterrence will necessarily include a nuclear component (whether forward-deployed or not). But the role of U.S. nuclear weapons in these regional deterrence architectures can be reduced by increasing the role of missile defenses and other capabilities.”

- The Pentagon’s April 2010 Nuclear Posture Review Report concluded that the United States can deter potential adversaries and reassure allies and partners “at significantly lower nuclear force levels and with reduced reliance on nuclear weapons” while “working to reduce the salience of nuclear weapons in international affairs and moving step-by-step toward eliminating them…”

- The Pentagon’s January 2012 strategy Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense concluded that, “It is possible that out deterrence goals can be achieved with a smaller nuclear force, which would reduce the number of nuclear weapons in our inventory as well as their role in U.S. national security strategy.” (Emphasis in original).

Underpinning these decisions is that only small nuclear forces are needed for contingencies against regional adversaries such as North Korea and Iran, which can better be addressed with conventional forces. But even against Russia (and increasingly China), which continues to dominate U.S. nuclear planning, the Pentagon and the Intelligence Community have concluded that “a disarming first strike [against the United States] will most likely not occurr,” and that Russia would “not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or break-out scenario under the New START Treaty…”

These changes have allowed reductions of nuclear forces and strike scenarios in the past, leaving a stockpile of roughly 4,650 warheads. But although very different from the SIOP, OPLAN 8010-12 is still thought to be focused on nuclear warfighting scenarios using a Cold War-like Triad of nuclear forces on high alert to hold at risk and, if necessary, hunt down and destroy nuclear (and to a smaller extent chemical and biological) forces, command and control facilities, military and national leadership, and war supporting infrastructure in a myriad of tailored strike scenarios.

In Prague four years ago, President Obama said: “To put an end to Cold War thinking, we will reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security…” Doing so takes more than trimming limited scenarios against small regional adversaries but changing the core mission against Russia and China.

So when President Obama signs his new Presidential Policy Directive in the near future, it is important that it directs the military to change OPLAN 8010-12 in such a way that it actually puts an end to Cold War thinking. This will be his last chance to do so.

Other background: Reviewing Nuclear Guidance: Putting Obama’s Words Into Action (Arms Control Today, 2011) | Obama and the Nuclear War Pan (FAS 2010) | From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence (FAS/NRDC 2009)

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

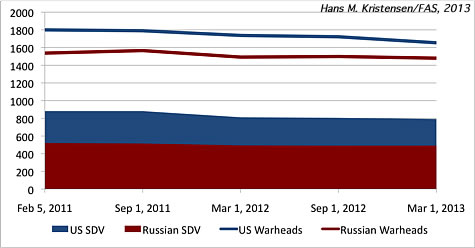

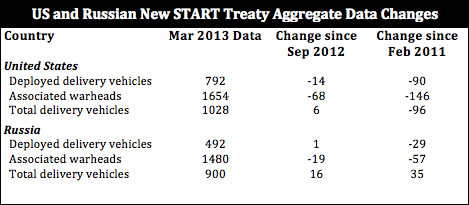

New START Data: US Reductions Finally Picking Up; Russia Flatlining

By Hans M. Kristensen

After two years of stalling, the latest New START Treaty aggregate data released today by the State Department indicates that U.S. warhead reductions under the treaty are finally picking up.

Russia, which is already below the treaty limit, has been more or less flatlining over the past year.

Seen in perspective, however, the warhead reductions achieved under New START so far are not impressive: since the treaty entered into effect in February 2011, the world’s two largest nuclear weapons states – with combined stockpiles of nearly 10,000 warheads – have only reduced their deployed arsenals by a total of 203 warheads!

The data for the United States shows a reduction of 68 warheads compared with September 2012. Fourteen of those are probably “fake” warheads attributed to B-52G bombers that are counted as deployed under the treaty, although they are neither deployed nor nuclear tasked anymore. The remaining 54-warhead reduction probably reflects downloading of the remaining MIRVed ICBMs (and some fluctuations in SLBM loadings of SSBNs in refit). Another 104 warheads will have to be reduced over the next five years to meet the treaty limit of 1,550 deployed accountable warheads by 2018 (although many of those will come from reducing bombers that are not actually assigned nuclear weapons).

Russia, which has been below the ceiling of 1,550 deployed accountable strategic warheads for the past year, appears to be flatlining. It is counted with a 19-warhead reduction compared with September 2012. But that number is too low say whether it reflects real reductions due to retirement of missiles or just fluctuations in SLBM loadings on SSBNs in refit. Russia increased its delivery vehicles slightly due to deployment of the first new Borei-class SSBN.

What’s most striking about the data, though, is the significant asymmetry in delivery vehicles: the United States has 300 deployed delivery vehicles more than Russia, a disparity that causes Russia to deploy more warheads on each delivery vehicle and fuels worst-case military planning and paranoia about treaty break-out plans.

A clear objective for the next arms control agreement between the United States and Russia will have to be to reduce the U.S. delivery vehicles and Russian warhead loading to improve stability of the postures.

Moreover, with only 203 deployed warheads cut since the New START Treaty entered into effect more than two years ago, and nearly 10,000 nuclear warheads remaining in their stockpiles combined, there is clearly a need for the United States and Russia to speed up implementation of the treaty and agree to significant additional reductions.

[Details about the reductions are murky because the aggregate data only includes overall numbers, and does not specify how many of each delivery system are counted. A more detailed analysis will follow when the full detailed U.S. data becomes available in a few weeks.]

Background: See previous New START Treaty data analysis

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.