Is ISIL a Radioactive Threat?

In the past several months, various news stories have raised the possibility that the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also commonly referred to as ISIS) could pose a radioactive threat. Headlines such as “Dirty bomb fears after ISIS rebels seize uranium stash,”1 “Stolen uranium compounds not only dirty bomb ingredients within ISIS’ grasp, say experts,”2 “Iraq rebels ‘seize nuclear materials,’” 3 and “U.S. fears ISIL smuggling nuclear and radioactive materials: ISIL could take control of radioactive, radiological materials”4 have appeared in mainstream media publications and on various blog posts. Often these articles contain unrelated file photos with radioactive themes that are apparently added to catch the eye of a potential reader and/or raise their level of concern.

Is there a serious threat or are these headlines over-hyped? Is there a real potential that ISIL could produce a “dirty bomb” and inflict radiation casualties and property damage in the United States, Europe, or any other state that might oppose ISIL as part of the recently formed U.S.-led coalition? What are the confirmed facts? What are reasonable assumptions about the situation in ISIL-controlled areas and what is a realistic assessment of the level of possible threat?

As anyone who has followed recent news reports about the rapid disintegration of the Iraqi Army in Western Iraq can appreciate, ISIL is now in control of sizable portions of Iraq and Syria. These ISIL-controlled areas include oilfields, hospitals, universities, and industrial facilities, which may be locations where various types of radioactive materials have been used, or are being used.

In July 2014, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) released a statement indicating that Iraq had notified the United Nations “that nuclear material has been seized from Mosul University.”5 The IAEA’s press release indicated that they believed that the material involved was “low-grade and would not present a significant safety, security or nuclear proliferation risk.” However, despite assessing the risk posed by the material as being low, the IAEA stated that “any loss of regulatory control over nuclear and other radioactive materials is a cause for concern.”6 The IAEA’s statement caused an initial flurry of press reports shortly after its release in July.

A second round of reports on the threat of ISIL using nuclear or radioactive material started in early September, triggered by the announcement of a U.S.-Iraq agreement on a Joint Action Plan to combat nuclear and radioactive smuggling.7 According to a Department of State (DOS) press release on the Joint Action Plan, the U.S. will provide Iraq with training and equipment via the Department of Energy’s Global Threat Reduction Initiative (GTRI) that will enhance Iraq’s capability to “locate, identify, characterize, and recover orphaned or disused radioactive sources in Iraq thereby reducing the risk of terrorists acquiring these dangerous materials.”8 Although State’s press release is not alarmist, it does state that the U.S. and Iraq share a conviction that nuclear smuggling and radiological terrorism are “critical and ongoing” threats and that the issues must be urgently addressed.9

While September’s headlines extrapolating State’s press release to U. S. “fears” might be characterized by some as over-hyping the issue, it is clear that both statements from the IAEA and the State Department have indicated that the situation in Iraq may be cause for concern. Did IAEA and DOS go too far in their statements? In their defense, it would be highly irresponsible to indicate that any situation where nuclear or other radioactive material might be in the hands of individuals or groups with a potential for criminal use is not a subject for concern. However, we need to go beyond such statements and determine what risks are posed by the materials that have been reported as possibly being under ISIL control in order to determine how concerned the public should be.

According to the IAEA’s press release, the material reported by Iraq was described as “nuclear material,” but this description does not imply that it is suitable for a yield producing nuclear weapon. In fact, the IAEA’s description of the material as “low-grade” indicates that the IAEA believes that this material is not enriched to the point where it could be used to produce a nuclear explosion. Furthermore, although the agency has not provided a technical description of the nuclear material, it is highly unlikely that this is anything other than low enriched uranium or perhaps even natural or depleted uranium, all of which would fit under the IAEA’s definition of “nuclear material.” If the material is not useful in a yield producing device, is it a radioactive hazard? All forms of uranium are slightly radioactive, but the level of radioactivity is so low that these materials would not pose a serious radioactive threat, (either to persons or property), if they were used in a Radioactive Dispersion Devices (RDDs). Even a “Dirty Bomb,” which is an RDD dispersed by explosives, would not be of significant concern.

Other than the nuclear material mentioned in the report to the United Nations, there are no known open source reports of loss of control of other radioactive materials. However, a lack of specific reporting does not mean that control is still established over any materials that are in ISIL -controlled areas. It would be prudent to assume that all materials in these areas are out of control and assessable to ISIL should it choose to use whatever radioactive materials can be found for criminal purposes. How do we know what materials may be at risk? Hopefully the Iraq Radioactive Sources Regulatory Authority (IRSRA) has/had a radioactive source registry in Iraq. If so, authorities should know in some detail what materials are in ISIL-controlled territories. The Syrian regulatory authority may have at one time had a similar registry that would indicate what may now be out of control in the ISIL-controlled areas of Syria. Unfortunately, there is no open source reporting of any of these materials so we are left to speculate as to what might be involved and what the consequences may be should those materials attempt to be used criminally.

It is doubtful that any radioactive materials in ISIL controlled areas are very large sources. The materials that would pose the greatest risk would probably be for medical uses. These sources are found in hospitals or clinics for cancer treatment or blood irradiation and typically use cesium 137 or cobalt 60, both of which are relatively long-lived (approximately 30 and five years respectively) and produce energetic gamma rays. It is also possible that radiography cameras containing iridium 192 and well logging sources that typically use cesium 137 and an americium beryllium neutron source may also be in the ISIL-controlled areas. Any technical expert would opine that these sources are capable of causing death and that dispersal of these materials would create a cleanup problem and possibly significant economic loss. However, experts almost uniformly agree that such materials do not constitute Weapons of Mass Destruction, but are potential sources for disruption and for causing public fear and panic. Furthermore the scenarios that pose the greatest risk for the United States or Europe from these materials are difficult for ISIL to organize and carry out.

If ISIL were to attempt to use such materials in an RDD, they would need to transport the materials to the target area (for example in the United States or Europe), in a manner that is undetectable and relatively safe for the person(s) transporting or accompanying a movement of the material. Although in some portions of a shipment cycle there would be no need to accompany the materials, at some point people would need to handle the materials. Even if the handlers had suicidal intent, shielding would be required in order to prevent detection of the energetic radiations that would be present for even a weak RDD. Shielding required for really dangerous amounts of these materials is typically both heavy and bulky and therefore the shielded materials cannot be easily transported simply by a person carrying them on their person or in their luggage. They would probably need to be shipped as cargo in or on some sort of vehicle (car, bus, train, ship, or plane). Surface methods of transport might reach Europe, but carriage by ship or air is necessary to reach the United States.10 Aircraft structures do not provide any inherent shielding and so the most logical (albeit not only), method of transportation to the United States or Europe would be by ship, probably from a Syrian port. Even though ISIL controls a significant land area, the logistics of shipping an item that is highly radioactive to the United States or Europe would be a complex process and need to defeat significant post-9/11 detection systems. These systems, although perhaps not 100 percent effective for all types and amounts of radioactive material, typically are thought to be very effective in the detection of high-level sources.

Any materials from ISIL-controlled areas could only be used in the United States or Europe with great difficulty. It is highly probable that the current radiation detection systems would be effective in deterring any such attempted use even if there were no human intelligence that would compromise such an effort. Even if ISIL could use materials for an RDD attack, the actual damage potential of these types of attacks is relatively low when they are compared to far simpler and often used terrorist tactics such as suicide vests and truck and car bombs. The casualties that would result from any theoretical RDD would be probably less than those resulting from a serious traffic accident and that is probably on the high end of casualty estimates. Indeed, many experts feel that most, if not all, of the serious injuries from a “dirty bomb” would result from the explosive effects of the bomb, not from the dispersal of radioactive materials. The major consequence of even a fairly effective dispersal of material would be a cleanup problem with the economic impact determined by the area contaminated and the level to which the area would need to be cleaned.

Efforts by the United States to work with the ongoing government in Iraq in improving detection and control of nuclear and other radioactive materials appear to be a prudent effort to minimize any threat from these materials in the ISIL-controlled areas. To date, ISIL has not made any threats to use radioactive material. That does not mean that ISIL is unaware of the potential, and we should be prepared for ISIL to use their surprisingly effective social media connections to attempt to make any future radioactive threat seem apocalyptic. Rational discussion of potential consequences and responses to an attack scenario should occur before an actual ISIL threat, rather than having the discussion in the 24/7 news frenzy that could invariably follow an ISIL threat.

Dr. George Moore is currently a Scientist in Residence and Adjunct Faculty Member at the Monterey Institute of International Studies’ James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, a Graduate School of Middlebury College, in Monterey, California. He teaches courses and workshops in nuclear trafficking, nuclear forensics, cyber security, drones and surveillance, and various other legal and technical topics. He also manages an International Safeguards Course sponsored by the National Nuclear Security Agency in cooperation with Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

From 2007-2012 Dr. Moore was a Senior Analyst in the IAEA’s Office of Nuclear Security where he was involved with, among other issues, the IAEA’s Illicit Trafficking Database System and the development of the Fundamentals of Nuclear Security publication, the top-level document in the Nuclear Security Series. Dr. Moore has over 40 years of computer programming experience in various programming languages and has managed large database and document systems. He completed IAEA training in cyber security at Brandenburg University and is the first instructor to use the IAEA’s new publication NS22 Cyber Security for Nuclear Security Professional as the basis for a course.

Dr. Moore is a former staff member of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory where he had various assignments in areas relating to nuclear physics, nuclear effects, radiation detection and measurement, nuclear threat analysis, and emergency field operations. He is also a former licensed research reactor operator (TRIGA).

Thinking More Clearly About Nuclear Weapons: The Ukrainian Crisis’ Overlooked Nuclear Risk

The destructive potential of nuclear weapons is so great that decisions impacting them should be made in a fully conscious, objective manner. Unfortunately, there is significant evidence that this is not the case. One of my Stanford course handouts1 lists almost two dozen assumptions which underlie our nuclear posture, but warrant critical re-examination. This column applies that same kind of analysis to the current Ukrainian crisis.

It is surprising and worrisome that almost none of the mainstream media’s coverage of the Ukrainian crisis has mentioned its nuclear risk. With the West feeling that Russia is solely to blame, and Russia having the mirror image perspective, neither side is likely to back down if one of their red lines is crossed. Add in America’s overwhelming conventional military superiority and Russia’s 8,000 nuclear weapons, and there is the potential for nuclear threats. And, where there is the potential for nuclear threats, there is also some potential for nuclear use.

I’m not saying a repeat of the Cuban Missile Crisis is likely, but given the potential consequences, even a small risk of the Ukrainian crisis escalating to nuclear threats would seem too high.

The frequency with which we find ourselves in such confrontations is also a factor. A low probability nuclear risk that occurs once per century is ten times less likely to explode in our faces than one that occurs once per decade. And the latter hypothesis (confrontations occurring approximately once per decade, instead of once per century) is supported by the empirical evidence, as the Georgian War occurred just six years ago.

While both Russia and the West are wrong that the current crisis is solely the other side’s fault, this article focuses on our mistakes since those are the ones we have the power to correct.

An example of the West’s belief that the crisis is all Russia’s fault appeared in a July 18 editorial 2 in The New York Times which claimed, “There is one man who can stop [the Ukrainian conflict] — President Vladimir Putin of Russia.”

Another example occurred on September 3, when President Obama stated: “It was not the government in Kyiv that destabilized eastern Ukraine; it’s been the pro-Russian separatists who are encouraged by Russia, financed by Russia, trained by Russia, supplied by Russia and armed by Russia. And the Russian forces that have now moved into Ukraine are not on a humanitarian or peacekeeping mission. They are Russian combat forces with Russian weapons in Russian tanks. Now, these are the facts. They are provable. They’re not subject to dispute.” (emphasis added)

So what’s the evidence that the New York Times and the president might be wrong? In early February, when the crisis was in its early and much less deadly stages, Ronald Reagan’s Ambassador to Moscow, Jack Matlock, wrote3: “I believe it has been a very big strategic mistake – by Russia, by the EU and most of all by the U.S. – to convert Ukrainian political and economic reform into an East-West struggle. … In both the short and long run only an approach that does not appear to threaten Russia is going to work.” (emphasis added)

A month later, on March 3, Dmitri Simes, a former adviser to President Nixon, seconded Ambassador Matlock’s perspective when he said in an interview4: “I think it [the Obama administration’s approach to the Ukraine] has contributed to the crisis. … there is no question in my mind that the United States has a responsibility to act. But what Obama is doing is exactly the opposite from what should be done in my view.”

Two days later, on March 5, President Nixon’s Secretary of State and National Security Adviser, Henry Kissinger, wrote:5 “Each [Russia, the West, and the various Ukrainian factions] has made the situation worse.”

A number of other articles by foreign policy experts also question the Times and President Obama placing all the blame for the crisis on Russia, but I hope I’ve made the point that Putin is not the only man who could end the fighting. Indeed, he may not be capable of doing that without us also correcting some of our mistakes.

Further evidence that the New York Times and President Obama might be wrong can be found in an intercepted and leaked phone conversation6 in which Estonia’s Foreign Minister, Urmas Paet – clearly no friend of Russia’s – stated that the sniper fire on February 20, which killed dozens of Maidan protesters and led to calls for Yanukovych’s head, appeared to have been a false flag operation perpetrated by the most violent elements within the protesters – for example, the ultra-nationalist Right Sektor, which is seen as neo-Nazi in some quarters.

Here is the exact wording of Paet’s key allegation in that phone call: “There is now stronger and stronger understanding that behind [the] snipers … it was not Yanukovych, but it was somebody from the new coalition.” That “new coalition” is now the Ukrainian government.

While this allegation has received little attention in the American mainstream media, German public television sent an investigative reporting team which reached the same conclusion7: “The Kiev Prosecutor General’s Office [of the interim government] is confident in their assessment [that Yanukovych’s people are to blame for the sniper fire, but] we are not.”

This is not to say that Paet and the German investigators are correct in their conclusions – just that it is dangerously sloppy thinking about nuclear matters not to take those allegations more seriously than we have.

While Putin has exaggerated the risk to ethnic Russians living in Ukraine for his own purposes, the West has overlooked those same risks. For example, on May 2 in Odessa, dozens of pro-Russian demonstrators were burned alive when an anti-Russian mob prevented them from fleeing the burning building into which they had been chased. According to the New York Times8: “The pro-Russians, outnumbered by the Ukrainians, fell back … [and] sought refuge in the trade union building. Yanus Milteynus, a 42-year-old construction worker and pro-Russian activist, said he watched from the roof as the pro-Ukrainian crowd threw firebombs into the building’s lower windows, while those inside feared being beaten to death by the crowd if they tried to flee. … As the building burned, Ukrainian activists sang the Ukrainian national anthem, witnesses on both sides said. They also hurled a new taunt: “Colorado” for the Colorado potato beetle, striped red and black like the pro-Russian ribbons. Those outside chanted “burn Colorado, burn,” witnesses said. Swastikalike symbols were spray painted on the building, along with graffiti reading “Galician SS,” though it was unclear when it had appeared, or who had painted it.”

Adding to the risk, on August 29, Ukraine took steps to move from non-aligned status to seeking NATO membership, and NATO’s Secretary-General Anders Fogh Rasmussen said he would “fully respect if the Ukrainian parliament decides to change that policy [of non-alignment].” Somewhat paradoxically, it is extremely dangerous – especially for Ukraine – for Rasmussen to encourage its hopes of joining NATO since Russia would likely respond aggressively to prevent that from occurring.

Also adding to the danger is an escalatory spiral that appears to be in process, with NATO taking actions that are seen as threatening by Russia and Russia responding in kind, with Putin reminding the world9 that, “Russia is one of the most powerful nuclear nations. This is a reality, not just words.”

We also need to question whether it is in our national security interests to ally ourselves with the Kiev government when, on September 1, its Defense Minister declared that, “A great war has arrived at our doorstep – the likes of which Europe has not seen since World War Two.”10

Also on September 1, a group of former CIA intelligence analysts warned11that: “Accusations of a major Russian invasion of Ukraine appear not to be supported by reliable intelligence. Rather, the intelligence seems to be of the same dubious, politically fixed kind used 12 years ago to justify the U.S.-led attack on Iraq.” (The group also warned about faulty intelligence in the lead-up to the Iraq War.)

These former intelligence analysts are not saying that our government’s accusation is wrong. But they are reminding us that there is historical evidence indicating that we should be more cautious in assuming that it is correct.

In a September 4 article in Foreign Policy, “Putin’s Nuclear Option,” 12 Jeffrey Taylor argues that: “Putin would never actually use nuclear weapons, would he? The scientist and longtime Putin critic Andrei Piontkovsky, a former executive director of the Strategic Studies Center in Moscow and a political commentator for the BBC World Service, believes he might. In August, Piontkovsky published a troubling account of what he believes Putin might do to win the current standoff with the West – and, in one blow, destroy NATO as an organization and finish off what’s left of America’s credibility as the world’s guardian of peace.”

I strongly encourage readers to read the full article. Again, Piotkovsky’s scenario is not likely, but given the consequences, even a small risk could be intolerable.

Defusing the Ukrainian crisis will require a more mature approach on the part of all parties. Focusing on what we need to do, we need to stop seeing Ukraine as a football game that will be won by the West or by Russia, and start being concerned with the safety of all its residents, of all ethnicities. If we do that, we will also reduce the risk that we find ourselves repeating the mistakes of the Cuban Missile Crisis, when neither side wanted to stare into the nuclear abyss, but both found themselves doing so.

As noted earlier, our mishandling of the Ukrainian crisis is unfortunately just one instance of a larger problem – dangerously sloppy thinking about nuclear weapons. Given that the survival of our homeland is at stake, our government needs to undertake a top-to-bottom review of the assumptions which underlie our current nuclear posture and correct any that are found to be wanting.

Dr. Martin E. Hellman is an Adjunct Senior Fellow for Nuclear Risk Analysis at FAS. Hellman was at IBM’s Watson Research Center from 1968-69 and an Assistant Professor of EE at MIT from 1969-71. Returning to Stanford in 1971, he served on the regular faculty until becoming Professor Emeritus in 1996. He has authored over seventy technical papers, ten U.S. patents and a number of foreign equivalents.

Along with Diffie and Merkle, Hellman invented public key cryptography, the technology which allows secure transactions on the Internet, including literally trillions of dollars of financial transactions daily. He has also been a long-time contributor to the computer privacy debate, starting with the issue of DES key size in 1975 and culminating with service (1994-96) on the National Research Council’s Committee to Study National Cryptographic Policy, whose main recommendations have since been implemented.

His current project, Defusing the Nuclear Threat, is applying quantitative risk analysis to a potential failure of nuclear deterrence. In addition to illuminating the level of risk inherent in threatening to destroy civilization in an effort to maintain the peace, this approach highlights how small changes, early in the accident chain, can reduce the risk far more than might first appear. This methodology has been endorsed by a number of prominent individuals including a former Director of the National Security Agency, Stanford’s President Emeritus, and two Nobel Laureates.

The New York Times: Which President Cut the Most Nukes?

By Hans M. Kristensen

The New York Time today profiles my recent blog about U.S. presidential nuclear weapon stockpile reductions.

The core of the story is that the Obama administration, despite its strong arms control rhetoric and efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons, so far has cut fewer nuclear warheads from the U.S. nuclear weapon stockpile than any other administration in history.

Even in terms of effect on the overall stockpile size, the Obama administration has had the least impact of any of the post-Cold War presidents.

There are obviously reasons for the disappointing performance: The administration has been squeezed between, on the one side, a conservative U.S. congress that has opposed any and every effort to reduce nuclear forces, and on the other side, a Russian president that has rejected all proposals to reduce nuclear forces below the New START Treaty level and dismissed ideas to expand arms control to non-strategic nuclear weapons (even though he has recently said he is interested in further reductions).

As a result, the United States and its allies (and Russians as well) will be threatened by more nuclear weapons than could have been the case had the Obama administration been able to fulfill its arms control agenda.

Congress only approved the modest New START Treaty in return for the administration promising to undertake a sweeping modernization of the nuclear arsenal and production complex. Because the force level is artificially kept at levels above and beyond what is needed for national and international security commitments, the bill to the American taxpayer will be much higher than necessary.

The New York Times article says the arms control community is renouncing the Obama administration for its poor performance. While we are certainly disappointed, what we’re actually seeking is a policy change that cuts excess capacity in the arsenal, eliminates redundancy, stimulates further international reductions, and saves the taxpayers billions of dollars in the process.

In addition to taking limited unilateral steps to reduce excess nuclear capacity, the Obama administration should spend its remaining two years in office testing Putin’s recent insistence on “negotiating further nuclear arms reductions.” The fewer nuclear weapons that threaten Americans and Russians the better. That should be a no-brainer for any president and any congress.

New York Times: Which President Cut the Most Nukes?

FAS Blog: How Presidents Arm and Disarm

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Polish F-16s In NATO Nuclear Exercise In Italy

NATO is currently conducting a nuclear strike exercise in northern Italy.

The exercise, known as Steadfast Noon 2014, practices employment of U.S. nuclear bombs deployed in Europe and includes aircraft from seven NATO countries: Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Turkey, and United States.

The timing of the exercise, which is held at the Ghedi Torre Air base in northern Italy, coincides with East-West relations having reached the lowest level in two decades and in danger of deteriorating further.

It is believed to be the first time that Poland has participated with F-16s in a NATO nuclear strike exercise.

Coinciding with the Steadfast Noon exercise, NATO is also conducting a Strike Evaluation (STRIKEVAL) nuclear certification inspection at Ghedi.

A nuclear security exercise was conducted at Ghedi Torre AB in January 2014, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of U.S. nuclear weapons deployment at the base.

Steadfast Noon/STRIKEVAL is the second nuclear weapons strike exercise in Italy in two years, following Steadfast Noon held at Aviano AB in 2013.

Italy hosts 70 of the 180 U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

The Role of Polish F-16s

The participation of Polish F-16s in a NATO nuclear strike exercise is noteworthy because Polish F-16s are not thought to be capable of delivery nuclear weapons or assigned nuclear strike missions under NATO or U.S. nuclear planning.

The two Polish F-16s that have been photographed at Ghedi Torre Air Base are from the 10th Tactical Squadron (ELT) of the 32nd Wing (BL) at Lask Air Base in western Poland. (Another source reported three Polish F-16s).

If Polish F-16s were directly involved in NATO nuclear strike planning, it would be a significant new development. NATO officially adheres to its “three no’s” policy, first adopted by the alliance in December 1996, according to which “NATO countries have no intention, no plan, and no reason to deploy nuclear weapons on the territory of new members nor any need to change any aspect of NATO’s nuclear posture or nuclear policy – and we do not foresee any future need to do so.” (Emphasis added).

Since then, NATO has in fact changed the posture several times, although not eastward: In 2001, by withdrawing nuclear weapons from Araxos AB earmarked for use by Greek aircraft; and later also withdrawing Incirlik AB weapons that during the first part of the W Bush administration were intended for use by Turkish aircraft (weapons for U.S. aircraft are still present at Incirlik); in 2002, by reducing the readiness level of nuclear aircraft from weeks to months; in 2003, by Germany closing Memmingen AB; in 2005, by withdrawing nuclear weapons from Ramstein AB in Germany; and in 2007, by withdrawing nuclear weapons from England. Overall, these changes have resulted in a unilateral reduction of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe by 62 percent since the “three no’s” policy was adopted in 1996, from 480 to 180 today.

The Deterrence and Defense Posture Review (DDPR) approved by NATO in 2012 determined that the remaining “nuclear force posture currently meets the criteria for an effective deterrence and defence posture.” And when asked in May 2014 if the Ukraine crisis would lead NATO to reconsider its pledge not to place nuclear weapons on the territory of new member states, then-NATO General Secretary Rasmussen said no: “At this stage, I do not foresee any NATO request to change the content of the NATO-Russia founding act.”

The 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act Agreement reference by Rasmussen echoed the 1996 policy but further explained that the three no’s policy “subsumes the fact that NATO has decided that it has no intention, no plan, and no reason to establish nuclear weapon storage sites on the territory of those members, whether through the construction of new nuclear storage facilities or the adaptation of old nuclear storage facilities. Nuclear storage sites are understood to be facilities specifically designed for the stationing of nuclear weapons, and include all types of hardened above or below ground facilities (storage bunkers or vaults) designed for storing nuclear weapons.” (Emphasis added).

The 1997 Founding Act language clearly seems more focused on storage facilities rather than other parts of the posture, such as aircraft or command and control facilities that could support the nuclear mission.

Lask AB As Nuclear Staging Base?

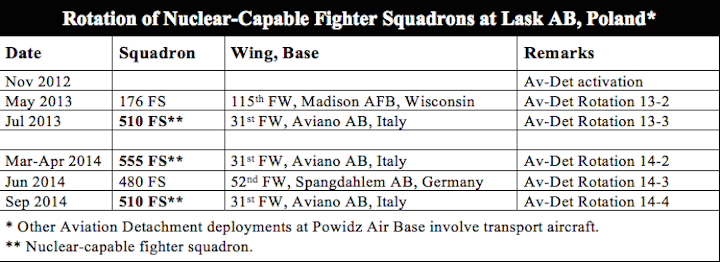

The participation of Polish F-16s from Lask AB in a NATO nuclear exercise is also interesting because the base is the primary base used by NATO aircraft deploying to Poland on temporary rotational deployments under a bilateral U.S. –Polish reinforcement treaty. Some of the U.S. squadrons that have deployed to Lask AB since 2012 are nuclear-capable.

In 2011, Poland and the United States signed an agreement to deploy a permanent U.S. Air Force aviation detachment (AV-DET) to Poland. The detachment organized under the 52nd Operations Group at Spangdahlem AB in Germany, which is also the home of the 52nd Munitions Maintenance Group that oversees the operations of the four MUNSS units deployed in four of the five western NATO countries that host U.S. nuclear weapons on their territory.

The Role of Polish F-16s

Since Polish F-16s are not nuclear-capable or assigned nuclear strike missions under U.S. and NATO strike planning, the aircraft participating in the Steadfast Noon-STRIKEVAL exercise instead are thought to serve other non-nuclear roles.

One role might be air-defense or suppression of ground-based radars. A nuclear strike would not only involve the aircraft carrying the nuclear weapon but also support aircraft to protect the strike package.

It is also potentially possible that participation of Polish F-16s reflects that NATO is working on increasing the role of conventional forces in Article V missions. The Obama administration’s nuclear employment strategy from June 2013 directed the U.S. military to “assess what objectives and effects could be achieved through integrated non-nuclear strike options” to reduce the role of nuclear weapons.

Poland is planning to equip its F-16s with the U.S.-produced Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missiles (JASSM), a new highly accurate standoff missile that was recently approved for sale to Poland.

The U.S. Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCS) claims that Poland’s acquisition of the JASSM “will not alter the basic military balance in the region,” but the sale of the weapon to Poland (and other European countries such as Finland) in fact seems likely to do so anyway.

The only standoff weapon currently on Polish F-16s is the 23-kilometer (13 miles) range Maverick (AGM-65) [update: as several readers have pointed out (see comments below), a number of other weapons are also available]; the JASSM, in contrast, will be able to hold at risk targets at more than ten times that range with greater accuracy. Moreover, while Maverick has an optical guidance, the JASSM has all-weather GPS guidance. The JASSM is “designed to destroy high-value, well-defended, fixed and relocateable targets.” The “significant standoff range” of more than 370 kilometers (230 miles) and jam resistant GPS-guided “pinpoint accuracy,” according to Lockheed Martin, means that JASSM’s “mission effectiveness approaches a single missile required to destroy a target.”

The Pentagon says Poland’s acquisition of the JASSM missile, seen here flying through a target hole in a test, “will not alter the basic military balance” in Eastern Europe.

DSCA anticipates that Poland will use the “enhanced capability [of the JASSM] as a deterrent to regional threats and to strengthen its homeland defense.” The JASSMs and associated aircraft upgrades, according to DSCA, “will allow Poland to strengthen its air-to-ground strike capabilities and increase its contribution to future NATO operations.”

Integration of weapons such as JASSM into NATO’s posture would seem to fit well with the U.S. goal to reduce the role of nuclear weapons by providing increased conventional target destruction capability backed by a strategic nuclear deterrent that “supports our ability to project power by communicating to potential nuclear-armed adversaries that they cannot escalate their way out of failed conventional aggression,” as stated in the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review. A total of 5,000 JASSMs are planned.

Lask AB is located only 286 kilometers (178 miles) from the Belarusian border and 324 kilometer (201 miles) from the Russian border in Kaliningrad Oblast. At a speed of 1,800 kilometers per hour (1,119 miles/hour, or Mach 1.47), an F-16 launched from Lask AB would be able to reach Kaliningrad in 12 minutes and Moscow in less than an hour.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Although the Steadfast Noon-STRIKEVAL nuclear exercise has been planned for a couple of years, the timing is delicate, to say the least, because of deteriorating East-West relations following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier this year. Russian and NATO exercises have combined to fuel a perception of a crisis that goes well beyond words to increased military posturing on both sides, reminiscent of mindsets we haven’t seen in Europe since the 1980s.

Under these conditions, there is a real risk that the tactical nuclear strike exercise at Ghedi AB with participation of Polish F-16s could feed into Russian paranoia about NATO’s military intensions. A comparable operation would be if Russia were to conduct nuclear air-strike exercises to reassure Belarus. That would deepen paranoia in eastern NATO countries and could give tactical nuclear forces in Europe a prominence that is not in anyone’s interest.

Both sides need to calm their military operations and focus on rebuilding normal relations. For Russia, that means pulling back forces from Ukrainian and NATO borders and end provocative aircraft operations near or into NATO (and Swedish and Finnish) airspace.

For NATO, that means explaining Poland’s role in the Steadfast Noon-STRIKEVAL nuclear strike exercise and the rotational deployments of U.S. nuclear-capable fighter-squadrons to Lask AB in the context of the “three no’s” policy. And it requires ensuring that reassurance of Eastern European allies does not result in conventional modernization programs or operations that deepen Russian paranoia.

Credit: Thanks to Roel Stynen of Vredesactie for first alerting me to the NATO exercise.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

How Presidents Arm and Disarm

The Obama administration has cut fewer nuclear weapons than any other post-Cold War administration.

It’s a funny thing: the administrations that talk the most about reducing nuclear weapons tend to reduce the least.

Analysis of the history of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile shows that the Obama administration so far has had the least effect on the size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile of any of the post-Cold War presidencies.

In fact, in terms of warhead numbers, the Obama administration so far has cut the least warheads from the stockpile of any administration ever.

I have previously described how Republican presidents historically – at least in the post-Cold War era – have been the biggest nuclear disarmers, in terms of warheads retired from the Pentagon’s nuclear warhead stockpile.

Additional analysis of the stockpile numbers declassified and published by the Obama administration reveals some interesting and sometimes surprising facts.

What went wrong? The Obama administration has recently taken a beating for its nuclear modernization efforts, so what can President Obama do in his remaining two years in office to improve his nuclear legacy?

Effect on Warhead Numbers

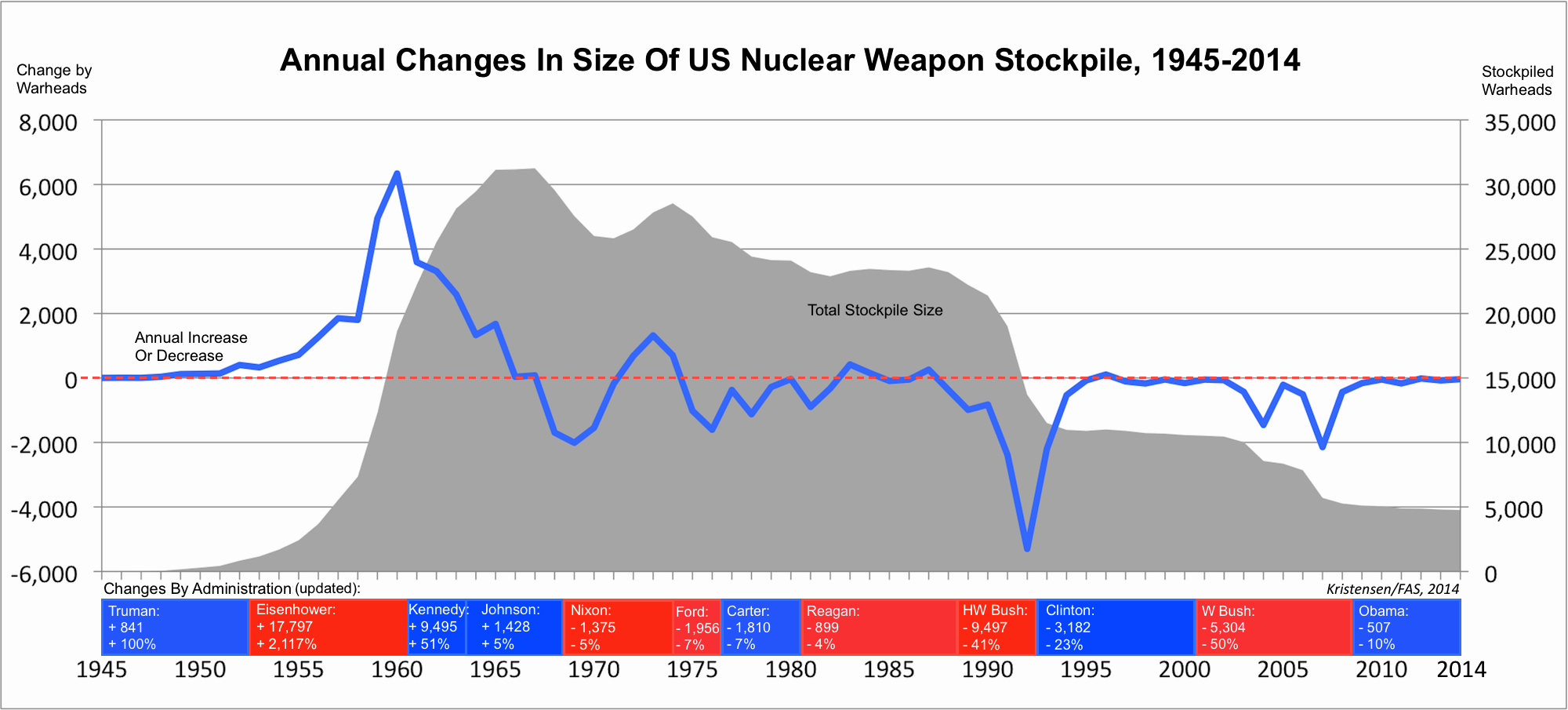

On the graph above I have plotted the stockpile changes over time in terms of the number of warheads that were added or withdrawn from the stockpile each year. Below the graph are shown the various administrations with the total number of warheads that each added or withdrew from the stockpile during its period in office.

The biggest increase in the stockpile occurred during the Eisenhower administration, which added a total of 17,797 warheads – an average of 2,225 warheads per year! Those were clearly crazy times; the all-time peak growth in one year was 1960, when 6,340 warheads were added to the stockpile! That same year, the United Sates produced a staggering 7,178 warheads, rolling them off the assembly line at an average rate of 20 new warheads every single day.

The Kennedy administration added another 9,495 warheads in the nearly three years before President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in October 1963. The Johnson administration initially continued increasing the stockpile and it was in 1967 that the stockpile reached its all-time high of 31,255 warheads. In its second term, however, the Johnson administration began reducing the stockpile – the first U.S. administration to do so – and ended up shrinking the stockpile by 1,428 warheads.

During the Nixon administration, the military started loading multiple warheads on ballistic missiles, but the stockpile declined for the first time due to retirement of large numbers of older warhead types. The successor, the Ford administration, reduced the stockpile and President Gerald Ford actually became the Cold War-period president who reduced the size of the stockpile the most: 1,956 warheads.

The Carter administration came in a close second Cold War disarmer with 1,810 warheads withdrawn from the stockpile.

The Reagan administration, which in its first term was seen by many as ramping up the Cold War, ended up shrinking the total stockpile by almost 900 warheads. But during three of its years in office, the administration actually increased the stockpile slightly, and the portion of those warheads that were deployed on strategic delivery vehicles increased as well.

As the first post-Cold War administration, the George H.W. Bush presidency initiated enormous nuclear weapons reductions and ended up shrinking the stockpile by almost 9,500 warheads – almost exactly the number the Kennedy administration increased the stockpile. In one year (1992), Bush cut 5,300 warheads, more than any other president – ever. Much of the Bush cut was related to the retirement of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The Clinton administration came into office riding the Bush reduction wave, so to speak, and in its first term cut approximately 3,000 warheads from the stockpile. But in his second term, President Clinton slowed down significantly and in one year (1996) actually increased the stockpile by 107 weapons – the first time since 1987 that had happened and the only increase in the post-Cold War era so far. It is still unclear what caused the 1996 increase. When the Clinton administration left office, there were still approximately 10,500 nuclear warheads in the stockpile.

President George W. Bush, who many of us in the arms control community saw as a lightning rod for trying to build new nuclear weapons and advocating more proactive use against so-called “rogue” states, ended up becoming one of the great nuclear disarmers of the post-Cold War era. Between 2004 and 2007 (mainly), the Bush W. administration unilaterally cut the stockpile by more than half to roughly 5,270 warheads, a level not seen since the Eisenhower administration. Yet the remaining Bush arsenal was considerably more capable than the Eisenhower arsenal.

President Barack Obama took office with a strong arms control profile, including a pledge to reduce the number and role of nuclear weapons, taking nuclear weapons off “hair-trigger” alert, and “put and end to Cold War thinking.” So far, however, this policy appears to have had only limited effect on the size of the stockpile, with about 500 warheads retired over six years.

Effect On Stockpile Size

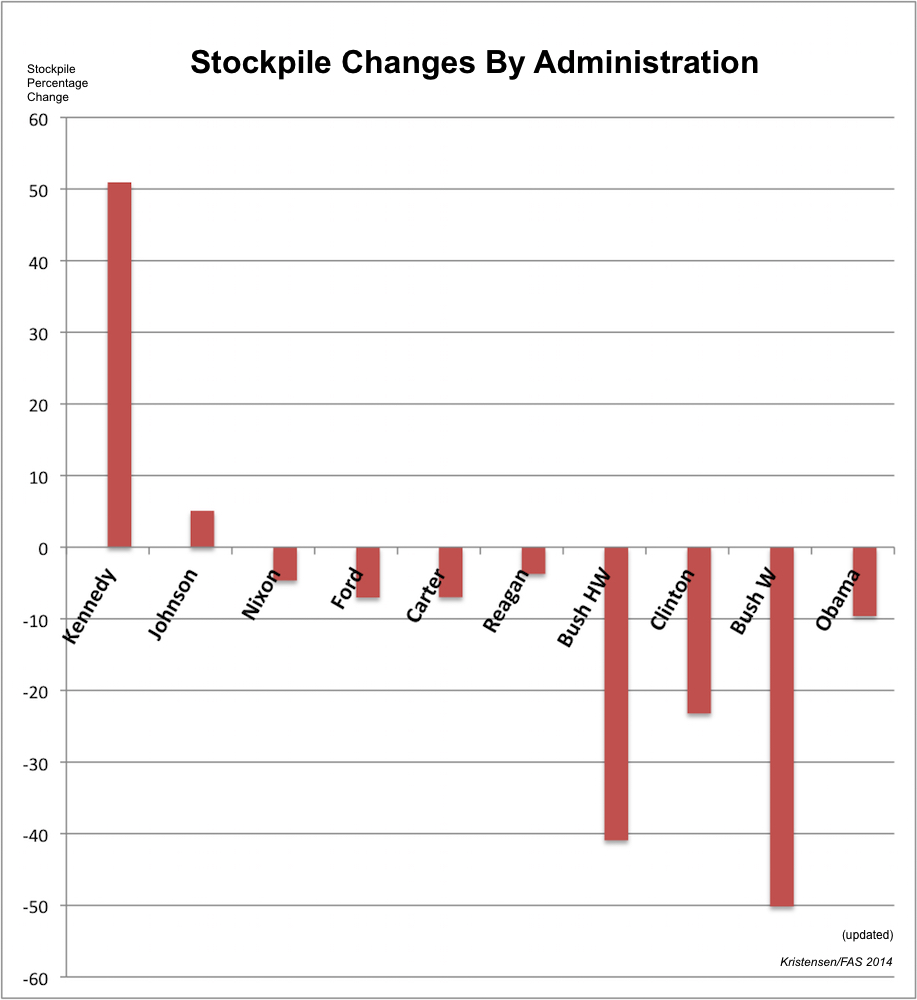

Counting warhead numbers is interesting but since the stockpile today is much smaller than during the previous three presidencies, comparing the number of warheads retired doesn’t accurately describe the degree of change inflicted by each president.

A better way is to compare the reductions as a percentage of the size of the stockpile at the beginning of each presidency. That way the data more clearly illustrates how much of an impact on stockpile size each president was responsible for.

This type of comparison shows that George W. Bush changed the stockpile the most: by a full 50 percent. His father, President H.W. Bush, came in a strong second with a 41 percent reduction. Combined, the Bush presidents cut a staggering 14,801 warheads from the stockpile during their 12 years in office – 1,233 warheads per year. President Clinton reduced the stockpile by 23 percent during his eight years in office.

The Obama administration has had less effect on the nuclear weapon stockpile than any other post-Cold War administration.

Despite his strong rhetoric about reducing the numbers of nuclear weapons, however, President Obama so far had the least effect on the size of the stockpile of any of the post-Cold War presidents: a reduction of 10 percent over six years. The remaining two years of the administration will likely see some limited reductions due to force adjustments and management, but nothing on the scale seen during the tree previous post-Cold War presidencies.

What Went Wrong?

There are of course reasons for the Obama administration’s limited success in reducing the number of nuclear weapons compared with the accomplishments of previous post-Cold War administrations.

The first reason is that the Obama administration during all of its tenure has faced a conservative Congress that has openly opposed any attempts to reduce the arsenal significantly. Even the modest New START Treaty was only agreed to in return for commitments to modernize the remaining arsenal. A conservative Congress does not complain when Republican presidents reduce the stockpile, only when Democratic president try to do so. As a result of the opposition, the United States is now stuck with a larger and more expensive nuclear arsenal than had Congress agreed to significant reductions.

A second reason is that Russian president Vladimir Putin has rejected additional arms reductions beyond the New START Treaty. Because the Obama administration has made additional reductions conditioned on Russian agreement, the United States today deploys one-third more nuclear warheads than it needs for national and international security commitments. Ironically, because of Putin’s opposition to additional reductions, Russia will now be “threatened” by more U.S. nuclear weapons than had Putin agreed to further reductions beyond New START. As a result, Russian taxpayers will have to pay more to maintain a bigger Russian nuclear force than would otherwise have been necessary.

A third reason is that the U.S. nuclear establishment during internal nuclear policy reviews was largely successful in beating back the more drastic disarmament ambitions president Obama may have had. Even before the Nuclear Posture Review was completed in April 2010, a future force level had already been decided for the New START Treaty based largely on the Bush administration’s guidance from 2002. President Obama’s Employment Strategy from June 2013 could have changed that, but it didn’t. It failed to order additional reductions beyond New START, reaffirmed the need for a Triad, retained the current alert and readiness level, and rejected less ambitious and demanding targeting strategies.

In the long run, some of the Obama administration’s policies are likely to result in additional unilateral reductions to the stockpile. One of these is the decision that fewer non-deployed warheads are needed in the “hedge.” Another effect will come from the decision to reduce the number of missiles on the next-generation ballistic missile submarine from 24 to 16, which will unilaterally reduce the number of warheads needed for the sea-based leg of the Triad. A third effect will come from a decision to phase out most of the gravity bombs in the arsenal. But these decisions depend on modernization of nuclear weapons production facilities and weapons and are unlikely to have a discernible effect on the size of the stockpile or arsenal until well after president Obama has left office.

The Next Two Years

During its last two years in office, the Obama administration’s best change to achieve some of the stockpile reductions it failed to demonstrate in the first six years would be to initiate reductions now that are planned for later. In addition to implementing the reductions planned under the New START Treaty early, potential options include offloading excess Trident II SLBMs and retiring excess W76 warheads above what is needed for arming the future fleet of 12 SSBNX submarines; there are currently nearly 50 Trident II SLBMs too many deployed and about 800 W76s too many in the stockpile, so many that the Navy has asked DOE to accept transfer of excess W76s from navy depots faster than planned to free up space and save money. It also includes retiring excess warheads for cruise missiles and gravity bombs above what’s required for the B61-12 and LRSO programs; most, if not all, B61-3, B61-10, B83-1, and W84 warheads could probably be retired right away. Moreover, several hundred W78 and W87 warheads for the Minuteman ICBMs could probably be retired because they’re in excess of what’s needed for the force planned under New START.

But in addition to retiring excess warheads, there are also strong fiscal and operational reasons to work with congressional leaders interested in trimming the planned modernization of the remaining nuclear forces. Options include reducing the SSBNX program from 12 to 10 or 8 operational submarines, reducing the ICBM force to 300 by closing one of the three bases and ending considerations to develop a new mobile or “hybrid” ICBM, delaying the next-generation bomber, canceling the new cruise missile (LRSO), scaling back the B61-12 program to a simple life-extension of the B61-7, canceling nuclear capability for the F-35 fighter-bomber, and work with NATO allies to phase out deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe. Such reductions would have the added benefit of significantly reducing the capacity needed for warhead life-extension programs and production facilities.

Achieving some or all of these reductions would free up significant resources more urgently needed for maintaining and modernizing non-nuclear forces. The excess nuclear forces provide no discernible benefits to day-to-day national security needs and the remaining forces would still be more than adequate to deter and defeat potential adversaries – even a more assertive Russia.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

W80-1 Warhead Selected For New Nuclear Cruise Missile

The U.S. Nuclear Weapons Council has selected the W80-1 thermonuclear warhead for the Air Force’s new nuclear cruise missile (Long-Range Standoff, LRSO) scheduled for deployment in 2027.

The W80-1 warhead is currently used on the Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM), but will be modified during a life-extension program and de-deployed with a new name: W80-4.

Under current plans, the ALCM will be retired in the mid-2020s and replaced with the more advanced LRSO, possibly starting in 2027.

The enormous cost of the program – $10-20 billion by some estimates – is robbing defense planners of resources needed for more important non-nuclear capabilities.

Even though the United States has thousands of nuclear warheads on ballistic missiles and is building a new penetrating bomber to deliver nuclear bombs, STRATCOM and Air Force leaders are arguing that a new nuclear cruise missile is needed as well.

But their description of the LRSO mission sounds a lot like old-fashioned nuclear warfighting that will add new military capabilities to the arsenal in conflict with the administration’s promise not to do so and reduce the role of nuclear weapons.

What Kind of Warhead?

The selection of the W80-1 warhead for the LRSO completes a multi-year process that also considered using the B61 and W84 warheads.

The W80-4 selected for the LRSO will be the fifth modification name for the W80 warhead (see table below): The first was the W80-0 for the Navy’s Tomahawk Land-Attack Cruise Missile (TLAM/N), which was retired in 2011; the second is the W80-1, which is still used the ALCM; the third was the W80-2, which was a planned LEP of the W80-0 but canceled in 2006; the fourth was the W80-3, a planned LEP of the W80-1 but canceled in 2006.

The B61 warhead has been used as the basis for a wide variety of warhead designs. It currently exists in five gravity bomb versions (B61-4, B61-4, B61-7, B61-10, B61-11) and was also used as the basis for the W85 warhead on the Pershing II ground-launched ballistic missile. After the Pershing II was eliminated by the INF Treaty, the W85 was converted into the B61-10. But the B61 was not selected for the LRSO partly because of concern about the risk of common-component failure from basing too many warheads on the same basic design.

The W84 was developed for the ground-launched cruise missile (BGM-109G), another weapon eliminated by the INF Treaty. As a more modern warhead, it includes a Fire Resistant Pit (which the W80-1 does not have) and a more advanced Permissive Action Link (PAL) use-control system. The W84 was retired from the stockpile in 2008 but was brought back as a LRSO candidate but was not selected, partly because not enough W84s were built to meet the requirement for the planned LRSO inventory.

Cost Estimates

In the past two year, NNSA has provided two very different cost estimates for the W80-4. The FY2014 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) published in June 2013 projected a total cost of approximately $11.6 billion through 2030. The FY2015 SSMP, in contrast, contained a significantly lower estimate: approximately $6.8 billion through 2033 (see graph below).

Official cost estimates for the W80-4 vary significantly.

The huge difference in the cost estimates (nearly 50%) is not explained in detail in the FY2015 SSMP, which only states that the FY2014 numbers were updated with a smaller “escalation factor” and “improvements in the cost models.” Curiously, the update only reduces the cost for the years that were particularly high (2019-2027), the years with warhead development and production engineering. The two-third reduction in the cost estimate may make it easier for NNSA to secure Congressional funding, but it also raises significant uncertainty about what the cost will actually be.

Assuming a planned production of approximately 500 LRSOs (there are currently 528 ALCMs in the stockpile and the New START Treaty does not count or limit cruise missiles), the cost estimates indicate a complex W80-4 LEP on par with the B61-12 LEP. NNSA told me the plan is to use many of the non-nuclear components and technologies on the W80-4 that were developed for the B61-12.

In addition to the cost of the W80-4 warhead itself, the cost estimate for completing the LRSO has not been announced but $227 million are programmed through 2019. Unofficial estimates put the total cost for the LRSO and W80-4 at $10-20 billion. In addition to these weapons costs, integration on the B-2A and next-generation long-range bomber (LRS-B) will add hundreds of millions more.

The W80-1 is not big, seen here with the author at the nuclear museum in Albuquerque, but it packs explosive yields of 5-150 kilotons.

What’s The Mission?

Why does the Air Force need a new nuclear cruise missile?

During a recent meeting with Pentagon officials, I asked why the LRSO was needed, given that the military also has gravity bombs on its bombers. “Because of what you see on that map,” a senior defense official said pointing to a large world map on the wall. The implication was that many targets would be risky to get to with a bomber. When reminded that the military also has land- and sea-based ballistic missiles that can reach all of those targets, another official explained: “Yes but they’re all brute weapons with high-yield warheads. We need the targeting flexibility and lower-yield options that the LRSO provides.”

The assumption for the argument is that if the Air Force didn’t have a nuclear cruise missile, an adversary could gamble that the United States would not risk an expensive stealth bomber to deliver a nuclear bomb and would not want to use ballistic missiles because that would be escalating too much. That’s quite an assumption but for the nuclear warfighter the cruise missile is seen as this great in-between weapon that increases targeting flexibility in a variety of regional strike scenarios.

That conversation could have taken place back in the 1980s because the answers sounded more like warfighting talk than deterrence. The two roles can be hard to differentiate and the Air Force’s budget request seems to include a bit of both: the LRSO “will be capable of penetrating and surviving advanced Integrated Air Defense Systems (IADS) from significant stand off range to prosecute strategic targets in support of the Air Force’s global attack capability and strategic deterrence core function.”

The deterrence function is provided by the existence of the weapon, but the global attack capability is what’s needed when deterrence fails. At that point, the mission is about target destruction: holding at risk what the adversary values most. Getting to the target is harder with a cruise missile than a ballistic missile, but it is easier with a cruise missile than a gravity bomb because the latter requires the bomber to fly very close to the target. That exposes the platform to all sorts of air defense capabilities. That’s why the Pentagon plans to spend a lot of money on equipping its next-generation long-range bomber (LRS-B) with low-observable technology.

The LRSO is therefore needed, STRATCOM commander Admiral Cecil Haney explained in June, to “effectively conduct global strike operations in the anti-access, access-denial environments.” When asked why they needed a standoff missile when they were building a stealth bomber, Haney acknowledge that “if you had all the stealth you could possibly have in a platform, then gravity bombs would solve it all.” But the stealth of the bomber will diminish over time because of countermeasures invented by adversaries, he warned. So “having standoff and stealth is very important” given how long the long-range bomber will operate into the future.

Lt. Gen. Stephen Wilson, the head of Air Force Global Strike Command, says the LRSO is needed to shoot holes in air defense systems.

Still, one could say that for any weapon and it doesn’t really explain what the nuclear mission is. But around the same time Admiral Haney made his statement, Air Force Global Strike Command commander General Wilson added a bit more texture: “There may be air defenses that are just too hard, it’s so redundant, that penetrating bombers become a challenge. But with standoff, I can make holes and gaps to allow a penetrating bomber to get in, and then it becomes a matter of balance.”

In this mission, the LRSO would not be used to keep the stealth bomber out of harms way per ce but as a nuclear sledgehammer to “kick down the door” so the bomber – potentially with B61-12 nuclear bombs in its bomb bay – could slip through the air defenses and get to its targets inside the country. Rather than deterrence, this is a real warfighting scenario that is a central element of STRATCOM’s Global Strike mission for the first few days of a conflict and includes a mix of weapons such as the B-2, F-22, and standoff weapons.

But why the sledgehammer mission would require a nuclear cruise missile is still not clear, as conventional cruise missiles have become significantly more capable against air defense and hard targets. In fact, most of the Global Strike scenarios would involve conventional weapons, not nuclear LRSOs. The Air Force has a $4 billion program underway to develop the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM) and an extended-range version (JASSM-ER) for deliver by B-1B, B-2A, B-52H bombers and F-15E, F-16, and F-35 fighters. A total of 4,900 missiles are planned, including 2,846 JASSM-ERs.

The next-generation bomber will be equipped with non-nuclear weapons such as the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM) that will provide it with a standoff capability similar to the LRSO, although with shorter range.

Since the next-generation long-range bomber would also be the launch platform for those conventional weapons, it will be exposed to the same risks with or without a nuclear LRSO.

Most recently, according to the Nuclear Security & Deterrence Monitor, Gen. Wilson added another twist to the justification:

“If I take a bomber, and I put standoff cruise missiles on it, in essence, it becomes very much like a sub. It’s got close to the same magazine capacity of a sub. So once I generate a bomber with standoff cruise missiles, it becomes a significant deterrent for any adversary. We often forget that. It possesses the same firepower, in essence, as a sub that we can position whenever and wherever we want, and it becomes a very strong deterrent. So I’m a strong proponent of being able to modernize our standoff missile capability.”

Although the claim that a bomber has “close to the same capacity of a sub” is vastly exaggerated (it is up to 20 warheads on 20 cruise missiles on a B-52H bomber versus 192 warheads on 24 sea-launched ballistic missiles on an Ohio-class submarine), the example helps illustrates the enormous overcapacity and redundancy in the current arsenal.

What Kind of Missile?

Although we have yet to see what kind of capabilities the LRSO will have, the Air Force description is that LRSO “will be capable of penetrating and surviving advanced Integrated Air Defense Systems (IADS) from significant stand off range to prosecute strategic targets in support of the Air Force’s global attack capability and strategic deterrence core function.”

There is every reason to expect that STRATCOM and the Air Force will want the weapon to have better military capabilities than the current Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM), perhaps with features similar to the Advanced Cruise Missile (ACM). After all, so the thinking goes, air defenses have improved significantly since the ALCM was deployed in 1982 and the LRSO will have to operate well into the middle of the century when air defense systems can be expected to be even better than today.

With a 3,000-km range similar to the ACM, the LRSO would theoretically be able to reach targets in much of Russia and most of China from launch-positions 1,000 kilometers from their coasts. Most of Russia and China’s nuclear forces are located in these areas.

In thinking about which capabilities would be needed for the LRSO, it is useful to recall the last time the warfighters argued that an improved cruise missile was needed. The ALCM was also “designed to evade air and ground-based defenses in order to strike targets at any location within any enemy’s territory,” but that was not good enough. So the Advanced Cruise Missile (ACM) was developed and deployed in 1992 to provide “significant improvements” over the ALCM in “range, accuracy, and survivability.” The rest of the mission was similar – “evade air and ground-based defenses in order to strike heavily defended, hardened targets at any location within any enemy’s territory” – but the requirement to hold at risk “heavily defended, hardened targets” was unique.

Yet when comparing the ALCM and ACM mission requirements and capabilities with the operational experience, GAO in 1993 found that “air defense threats had been overestimated” and that “tests did not demonstrate low ALCM survivability.” The ACM’s range was found to be “only slightly better than the older ALCM’s demonstrated capability,” and GAO concluded that “the improvement in accuracy offered by the ACM appears to have little real operational significance.”

The ACM was produced at great cost to provide improved targeting capabilities over the ALCM but apparently had little operational significance and was retired early in 2007. Will LRSO repeat the mistake?

Nonetheless, the ACM was produced in 1992-1993 at a cost of more than $10 billion. Strategic Air Command initially wanted 1461 missiles, but the high cost and the end of the Cold War caused Pentagon to cut the program to only 430 missiles. A sub-sonic cruise missile with a range of 3,000 kilometers (1,865 miles) and hard-target kill capability with the W80-1 warhead, the ACM was designed for external carriage on the B-52H bomber, with up to 12 missiles under the wings. The B-2 was also capable of carrying the ACM but as a penetrating stealth bomber there was never a need to assign it the stealthy standoff missile as well.

The ACM was supposed to undergo a life extension program to extend it to 2030, but after only 15 years of service the missile was retired early in 2007. An Enhanced Cruise Missile (ECM) was planned by the Bush administration, but it never materialized. It is likely, but still not clear, that LRSO will make use of some of the technologies from the ACM and ECM programs.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The W80-1 warhead has been selected to arm the new Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) missile, a $10-20 billion weapon system the Air Force plans to deploy in the late-2020s but can poorly afford.

Even though the United States has thousands of nuclear warheads on land- and sea-based ballistic missiles that can reach the same targets intended for the LRSO, the military argues that a new nuclear standoff weapon is needed to spare a new penetrating bomber from enemy air-defense threats.

Yet the same bomber will be also equipped with conventional weapons – some standoff, some not – that will expose it to the same kinds of threats anyway. So the claim that the LRSO is needed to spare the next-generation bomber from air-defense threats sounds a bit like a straw man argument.

The mission for the LRSO is vague at best and to the extent the Air Force has described one it sounds like a warfighting mission from the Cold War with nuclear cruise missiles shooting holes in enemy air defense systems. Given the conventional weapon systems that have been developed over the past two decades, it is highly questionable whether such a mission requires a nuclear cruise missile.

The Air Force has a large inventory of W80-1 warheads. Nearly 2,000 were built, 528 are currently used on the ALCM, and hundreds are in storage at the Kirtland Underground Maintenance and Munitions Storage Complex (KUMMSC) near Kirtland AFB in New Mexico.

The warfighters and the strategists might want a nuclear cruise missile as a flexible weapon for regional scenarios. But good to have is not the same as essential. And the regional scenarios they use to justify it are vague and largely unknown – certainly untested – in the public debate.

In the nuclear force structure planned for the future, the United States will have roughly 1,500 warheads deployed on land- and sea-based ballistic missiles. Nearly three-quarters of those warheads will be onboard submarines that can move to positions off adversaries anywhere in the world and launch missiles that can put warheads on target in as little as 15 minutes.

It really stretches the imagination why such a capability, backed up by nuclear bombs on bombers and the enormous conventional capability the U.S. military possesses, would be insufficient to deter or dissuade any potential adversary that can be deterred or dissuaded.

As the number of warheads deployed on land- and sea-based ballistic missiles continues to drop in the future, long-range, highly accurate, stealthy, standoff cruise missiles will increasingly complicate the situation. These weapons are not counted under the New START treaty and if a follow-on treaty does not succeed in limiting them, which seems unlikely in the current political climate, a new round of nuclear cruise missile deployments could become real spoilers. There are currently more ALCMs than ICBMs in the U.S. arsenal and with each bomber capable of loading up to 20 missiles the rapid upload capacity is considerable.

Under the 1,500 deployed strategic warhead posture of the New START treaty, the unaccounted cruise missiles could very quickly increase the force by one-third to 2,000 warheads. Under a posture of 1,000 deployed strategic warheads, which the Obama administration has proposed for the future, the effect would be even more dramatic: the air-launched cruise missiles could quickly increase the number of deployed warheads by 50 percent. Not good for crisis stability!

As things stand at the moment, the only real argument for the new cruise missile seems to be that the Air Force currently has one, but it’s getting old, so it needs a new one. Add to that the fact that Russia is also developing a new cruise missile, and all clear thinking about whether the LRSO is needed seems to fly out the window. Rather than automatically developing and deploying a new nuclear cruise missile, the administration and Congress need to ask tough questions about the need for the LRSO and whether the money could be better spent elsewhere on non-nuclear capabilities that – unlike a nuclear cruise missile – are actually useful in supporting U.S. national and international security commitments.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Transcript of 1954 Oppenheimer Hearing Declassified in Full

The transcript of the momentous 1954 Atomic Energy Commission hearing that led the AEC to revoke the security clearance of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist who had led the Manhattan Project to produce the first atomic bomb, has now been declassified in full by the Department of Energy.

“The Department of Energy has re-reviewed the original transcript and is making available to the public, for the first time, the full text of the transcript in its original form,” according to a notice posted on Friday.

The Oppenheimer hearing was a watershed event that signaled a crisis in the nuclear weapons bureaucracy and a fracturing of the early post-war national security consensus. Asked for his opinion of the proceedings at the time, Oppenheimer told an Associated Press reporter (cited by Philip Stern) that “People will study the record of this case and reach their own conclusions. I think there is something to be learned from it.”

And so there is. But what?

“No document better explains the America of the cold war — its fears and resentments, its anxieties and dilemmas,” according to Richard Polenberg, who produced an abridged edition of the hearing transcript in 2002 based on the redacted original. “The Oppenheimer hearing also serves as a reminder of the fragility of individual rights and of how easily they may be lost.”

It further represented a breakdown in relations between scientists and the U.S. government and within the scientific community itself.

“The Oppenheimer hearing claims our attention not only because it was unjust but because it undermined respect for independent scientific thinking at a time when such thinking was desperately needed,” wrote historian Priscilla J. McMillan.

First published in redacted form by the Government Printing Office in 1954, the Oppenheimer hearing became a GPO best-seller and went on to inform countless historical studies.

The transcript has attracted intense scholarly attention even to some of its finer details. At one point (Volume II, p. 281), for example, Oppenheimer is quoted as saying “I think you can’t make an anomalous rise twice.” What he actually said, according to author Philip M. Stern, was “I think you can’t make an omelet rise twice.”

The Department of Energy has previously declassified some portions of the Oppenheimer transcript in response to FOIA requests. But this is said to be the first release of the entire unredacted text. It is part of a continuing series of DOE declassifications of historical records of documents of particular historic value and public interest.

The newly declassified portions are helpfully consolidated and cross-referenced in a separate volume entitled “Record of Deletions.”

At first glance, it is not clear that the new disclosures will substantially revise or add to previous understandings of the Oppenheimer hearing. But their release does finally remove a blemish of secrecy from this historic case.

New START: Russia and the United States Increase Deployed Nuclear Arsenals

Three and a half years after the New START Treaty entered into force in February 2011, many would probably expect that the United States and Russia had decisively reduced their deployed strategic nuclear weapons.

On the contrary, the latest aggregate treaty data shows that the two nuclear superpowers both increased their deployed nuclear forces compared with March 2014 when the previous count was made.

Russia has increased its deployed weapons the most: by 131 warheads on 23 additional launchers. Russia, who went below the treaty limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads in 2013, is now back above the limit by 93 warheads. And Russia is now counted – get this – as having more strategic warheads deployed than when the treaty first went into force in February 2011!

Before arms control opponents in Congress get their banners out, however, it is important to remind that these changes do not reflect a build-up the Russian nuclear arsenal. The increase results from the deployment of new missiles and fluctuations caused by existing launchers moving in and out of overhaul. Hundreds of Russian missiles will be retired over the next decade. The size of the Russian arsenals will most likely continue to decrease over the next decade.

Nonetheless, the data is disappointing for both nuclear superpowers – almost embarrassing – because it shows that neither has made substantial reductions in its deployed nuclear arsenal since the New START Treaty entered into force in 2011.

The meager performance is risky in the run-up to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty review conference in April 2015 where the United States and Russia – together with China, Britain, and France – must demonstrate their progress toward nuclear disarmament to ensure the support of the other countries that have signed the NPT in strengthening the non-proliferation treaty regime.

Russian Deployments

The data for Russia is particularly interesting because it now has 106 warheads more deployed than when the New START Treaty went into force in February 2011. The number of deployed launchers is exactly the same: 106.

This does not mean that Russia is in the middle of a nuclear arms build-up; over the next decade more than 240 old Soviet-era land- and sea-based missiles are scheduled to be withdrawn from service. But the rate at which the older missiles are withdrawn has been slowing down recently from about 50 missiles per year before the New START treaty to about 22 missiles per year after New START. The Russian military wants to retire all the old missiles by the early 2020s, so the current rate will need to pick up a little.

At the same time, the rate of introduction of new land-based missiles to replace the old ones has increased from approximately 9 missiles per year to about 18. The net effect is that the total missile force and warheads deployed on it have increased slightly since 2013.

The new deployments include the SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24) ICBM, of which the first two regiments with 18 mobile missiles were put in service with the Teykovo division in 2010-2012, replacing SS-25s (Topol) previously there. Deployment followed in late-2013 at the Novosibirsk and Nizhniy Tagil divisions, each of which now has one regiment for a total of 36 RS-24s. This number will grow to 54 missiles by the end of this year because the two divisions are scheduled to receive a second regiment. And because each RS-24 carries an estimated 4 warheads (compared with a single warhead on the SS-25), the number of deployed warheads has increased.

Introduction of the SS-27 Mod (RS-24) road-mobile ICBM is underway at the 42nd Missile Division at Nizhniy Tagil in central Russia. Click to see full size image.

Also underway is the deployment of SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24) in silos at the Kozelsk division, where they are replacing old SS-19s. The first regiment of 10 RS-24s was scheduled to become operational by the end of this year but appears to have fallen behind schedule with only 4 missiles expected. It has not been announced how many missiles are planned for Kozelsk but it might involve 6 regiments with a total of 60 missiles (a similar number of SS-27 Mod 1s (Topol-M) were installed at Tatishchevo between 1997 and 2013). Since each RS-24 carries 4 warheads compared with the 6 on the SS-19, the number of silo-based warheads will decrease over the next decade.

Another reason for the increase in the latest New START data is probably the long-awaited introduction of the new Borei-class of ballistic missile submarines. The precise loadout status of the first submarines is uncertain, but the first might have been partially or fully loaded by now. The first two boats (Yuri Dolgoruy and Alexander Nevsky) entered service in late-2013 but have been without missiles because of the troubled test-launch performance of their missile (SS-N-32, Bulava), which has failed about half of its test launched since 2005. After fixes were made, a successful launch took place on September 10 from the third Borei SSBN, the Vladimir Monomakh. The Yuri Dolgoruy is scheduled to conduct an operational launch later this month. A total of 8 Borei SSBNs are planned, each with 16 Bulavas, each with 6 warheads, for a total of nearly 100 warheads per boat.

A new Borei-class SSBN at missile loading pier by the Okolnaya SLBM Deport at Severomorsk on the Kola Peninsula. Click to see full size image.

United States

For the United States, the data shows that the number of warheads deployed on strategic missiles increased slightly since March, by 57 warheads from 1,585 to 1,642. The number of deployed launchers also increased, by 16 from 778 to 794.

The reason for the U.S. increase is not an actual increase of the nuclear arsenal but reflects fluctuations caused by the number of launchers in overhaul at any given time. The biggest effect is caused by SSBNs loading or offloading missiles, most importantly the return to service of the USS West Virginia (SSBN-736) after a refueling overhaul with a load of 24 missiles and approximately 100 warheads.

More details will be come available in December when the State Department is expected to release the detailed unclassified breakdown of the U.S. aggregate data for October.

Overall, however, the U.S. performance under the treaty is better than that of Russia because the data shows that the United States has actually reduced its deployed force structure since 2011: by 158 warheads and 88 launchers. In addition, the U.S. military has also destroyed 124 non-deployed launchers including empty silos and retired bombers.