Marshall and the Atomic Bomb

General George C. Marshall and the Atomic Bomb (Praeger, 2016) provides the first full narrative describing General Marshall’s crucial role in the first decade of nuclear weapons that included the Manhattan Project, the use of the atomic bomb on Japan, and their management during the early years of the Cold War.

Marshall is best known today as the architect of the plan for Europe’s recovery in the aftermath of World War II—the Marshall Plan. He also earned acclaim as the master strategist of the Allied victory in World War II. Marshall mobilized and equipped the Army and Air Force under a single command, serving as the primary conduit for information between the Army and the Air Force, as well as the president and secretary of war. As Army Chief of Staff during World War II, he developed a close working relationship with Admiral Earnest King, Chief of Naval Operations; worked with Congress and leaders of industry on funding and producing resources for the war; and developed and implemented the successful strategy the Allies pursued in fighting the war. Last but not least of his responsibilities was the production of the atomic bomb.

The Beginnings

An early morning phone call to General Marshall and a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt led to Marshall’s little known, nonetheless critical, role in the development and use of the atomic bomb. The call, received at 3:00 a.m. on September 1, 1939, informed Marshall that German dive bombers had attacked Warsaw. The letter signed by noted physicist Albert Einstein and delivered a month later, informed Roosevelt of the possibility of producing an enormously powerful bomb using a nuclear chain reaction in uranium.

As Marshall hung up the phone, he told his drowsy wife, “Well, it’s come.” He dressed quickly and went to his office. Later that day he would be sworn in as Army chief of staff while German troops marched into Poland in a blitzkrieg that launched World War II.

Nearly one year before, German scientists had observed that bombarding uranium atoms with neutrons caused them to split into smaller elements, releasing a tremendous amount of energy. This fission of a uranium atom also generates additional neutrons, which can then split other uranium atoms to produce a nuclear chain reaction. Physicists in many countries recognized this rapid chain reaction in uranium could produce a powerful atomic bomb. Among them was Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard, who realized that the Germans in particular were in an excellent position to produce an atomic bomb. Szilard, like Albert Einstein, had immigrated to the United States to escape Nazi persecution. He believed the U.S. government should be alerted to this possibility. He reasoned that Einstein, a renowned scientist, would be in a position to gain the attention of the U.S. government. So, on July 12, 1939, he visited Einstein at his home on Long Island to discuss the prospect of a U.S. atomic bomb. Szilard’s explanation of a nuclear chain reaction in uranium surprised Einstein, who had not followed recent developments in nuclear physics. Einstein pondered this new revelation and then slowly remarked, “I haven’t thought about that at all.”1 He realized that nuclear fission was the conversion of mass to energy (a demonstration of his famous 1905 E=mc2 equation).

In the letter, which was delivered October 4, 1939, Einstein warned the president that the Germans might be developing a game-changing bomb, and he raised the prospect of the United States building a weapon of its own. Roosevelt immediately approved the establishment of a committee to investigate the feasibility of the United States producing such a weapon, and Marshall’s remarkable career took a significant turn.

Marshall’s direct involvement with nuclear weapons came two years after these initial communications of 1939, when the president appointed him to the Top Policy Group, established to provide Marshall with advice on atomic energy. Little did Marshall realize that the atomic bomb would hasten the end of the war, dramatically alter the future of warfare, and profoundly influence the post-war world. As a soldier who came of age in the era that saw both trench warfare and the implementation of new technologies on the battlefield, Marshall was skeptical, but open, to the possibilities this new weapon presented. Almost a decade later, as secretary of state and secretary of defense, he confronted profound issues related to nuclear weapons.

Expanding the size of the Army, training new draftees, reorganizing the command structure, and acquiring the necessary materials and equipment had required strong leadership within both the military and Congress. In guiding these efforts, Marshall had gained the confidence of the president, advisor Harry Hopkins, Stimson, and the Army officer corps. He also acquired the respect of congressmen during his numerous committee appearances in support of the funds requested for the mobilization. Thus, despite the demands of these critical assignments, it was not surprising the president appointed Marshall to the influential policy group for atomic power.

As a member of the Top Policy Group, General Marshall was privy to the reports and plans for expanding the project. In 1943, when research indicated that the United States could produce a bomb, the Army assumed responsibility for its production. That meant Marshall, as Army chief of staff, became responsible for the massive effort known as the Manhattan Project, (that built the atomic bombs dropped on Japan). His oversight of the Army’s budget allowed him to divert funds necessary to initiate the project. Later, his reputation and influence were instrumental in securing approval for additional funding from congressmen who were told only that the project was important for winning the war. When the bomb emerged as a weapon that might end the war in the Pacific, he advised Secretary of War Henry Stimson and President Harry Truman regarding its use on Japan. This decision shortened the war and unleashed the specter of nuclear holocaust on the world.2

The Manhattan Project

Marshall and Stimson oversaw the largest scientific project in history. From 1942 to 1946, an estimated 500,000 people were involved in producing the bombs, only a few of whom knew the objective of the project. According to one estimate, the Manhattan project cost $2.2 billion (approximately $30 billion in 2014 dollars) from 1942 to 1946.3

The project encompassed a nationwide system of production plants and laboratories. The Clinton Engineering Works at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, used sequence thermal diffusion, electromagnetic separation, and gaseous diffusion methods to enrich uranium in order to produce the concentrated, fissile uranium-235 required for the bomb. (Natural uranium has less than one percent uranium-235 and more than 99 percent non-fissile uranium-238, and nuclear explosives typically require a uranium mixture with 80 percent or more concentration in uranium-235.) Nuclear reactors at Hanford, Washington, produced small amounts of plutonium-239, which were separated from spent reactor fuel by chemical means. These fissile materials were then sent to Los Alamos, New Mexico, where they were transformed into the critical components of the first atomic bombs. In addition to these major installations, many other industries and laboratories throughout the U.S. contributed to the Project.

In early June 1945, the uranium and plutonium were fashioned into components for the atomic bombs nicknamed “Little Boy” (the uranium-235 bomb) and “Fat Man” (the plutonium-239 weapon). Because there was only enough enriched uranium for one “Little Boy” and its design was simpler than that of “Fat Man,” it was not tested. The weapons designers were confident in the simple gun type mechanism to trigger the bomb. One of the two available “Fat Man” weapons was used to test the more complicated implosion method of detonation on July 16 at Alamogordo, New Mexico.

Leslie Groves

In one key move, Marshall assigned Colonel Leslie Groves to manage the project and then provided him with the required resources to carry it through. The cooperation between the dynamic Groves and the reserved Marshall was critical in directing the largest scientific project in history, which produced the atomic bomb in less than two years.

Groves first met General Marshall when he reported with a group of officers for duty with the War Department General Staff in June 1939. Marshall appreciated Groves’ management skills and wanted to keep him at the War Department in Washington. Although Groves had little direct contact with Marshall, he appreciated the fact that Groves had turned down a transfer from Washington to engineering duty.

Groves was given full authority to create the organizational structure and lines of command for the project, which became an independent command, no longer held accountable to the Corps of Engineers. He reported directly to Marshall and Stimson. This structure worked well due to the relationship between Groves and his superiors during the three-year project. The relationship of mutual trust, support, and respect is reflected in a post-war interview where Groves stated:

One reason why we were so successful was non-interference from above. General Marshall never interfered with anything that was going on. He didn’t ask for regular reports; he saw me whenever I wanted to see him and his instructions were very clear. Never once did I have to talk about the approval for money appropriations. 4

Marshall’s Leadership

Marshall’s directional genius included the ability to foster collaboration among groups with disparate interests. As Army chief of staff, he worked with Allied military leaders and heads of state to implement strategies for defeating the Axis. This talent was also critical to the success of the Manhattan Project. Marshall insured cooperation between the Army and the scientists, obtained funds from Congress while keeping their intended use a secret, and supported Groves’ forceful management style. Marshall and Stimson provided continuity for the atomic program during the transition of presidential leadership from Roosevelt to Truman.

Marshall’s influence on decisions leading to the use of the atomic bomb on Japan was as important as that of President Truman’s two top advisors, Stimson and Secretary of State James Byrnes. Marshall’s wise counsel influenced the views of Truman and his advisors as they weighed options for ending the war. Marshall provided valued advice on military issues, including the impact of the Soviet Union’s entry into the Pacific war, the pros and cons of an invasion of the Japanese homeland, and the conditions for a Japanese surrender.

Uncertainty

As the war continued in the Pacific, Marshall and Stimson wrestled with the issues surrounding the use of the bomb on Japan and its implications for the post-war world. They often discussed the political and diplomatic issues associated with Japan’s surrender and Russia’s involvement in the Pacific theater. Stalin had agreed with Roosevelt and Churchill at the February 1945 Yalta Conference to enter the war against Japan within 90 days after Germany’s surrender. Marshall recognized the major role that the Soviet army could play in defeating Germany and believed it would also be valuable in the conquest of Japan. He thought Russian engagement of the Japanese on the Chinese mainland would keep Japan from moving troops to the home islands. He also noted that the Russians could invade Manchuria whenever they wished, thus allowing them to benefit from the surrender terms.

Still, Marshall kept his focus on military planning, leaving Stimson to manage the politics and diplomacy associated with the bomb. As the end of the war in the Pacific drew closer, allied military actions were dependent on Japan’s acceptance of the terms of surrender. Marshall understood that there was a choice between obtaining Japan’s unconditional surrender at a time when the nation’s morale was at a low point, and an invasion accompanied by Soviet intervention.5 He also considered the bomb as a possible means of “shocking the nation into surrender.”

Marshall was not certain that the strategic use of the bomb on a Japanese city would end the war and he believed an invasion was a real possibility. If necessary, he believed that additional atomic bombs could be used as tactical weapons to support the invasion. The low estimates of the explosive power of the bomb that Marshall received from Groves, as well as the wide range of estimates from the Project’s scientists, led him to doubt its strategic value6 Given this uncertainty, Marshall maintained his conviction that in the absence of a diplomatic solution, allied troops would have to occupy the Japanese home islands to insure the nation’s complete capitulation. If an invasion became necessary, he believed Soviet entry into the war with Japan would be most helpful.

Military Options

With the future of the bomb still uncertain, Marshall, as operative head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, heard proposals from the Army Air Forces and Navy for forcing Japan to surrender. Naval planners felt that a tight blockade would force the Japanese into capitulation, while the Air Force leaders favored bombing them into submission. Marshall maintained that invasion of the home islands would be necessary, given the resistance encountered on Saipan, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. Moreover, the resilience of the Japanese to the intense bombing of their cities reinforced his position. He remained a conventional soldier who felt an invasion would be necessary to conquer an enemy. Nevertheless, he viewed the atomic bomb as a possible means of ending the war to avoid an invasion.

Marshall supported a strategy to apply increasing pressure on Japan. It included an immediate increase in conventional bombing and a tightened naval blockade, followed by Russian entry into the war in August and use of the atomic bomb when it became available. If these actions failed to produce surrender, Kyushu would be invaded on November 1, followed by Honshu in March 1946. Marshall left the decision to use the bomb to the president. He told Assistant Secretary of War, John McCloy “whether we should drop the bomb on Japan was a matter for the president to decide, not the chief of staff, since it was not a military question.7 He maintained his position of civilian control of nuclear weapons after the war.

Japan’s Surrender

By the end of July 1945, leaders in the United States and Japan remained deadlocked on the means of ending the war. The options for the United States were either a costly invasion to force a quick surrender or the continuation of the bombing and blockade, which came with the risk of losing the American peoples’ support for the war. Japan’s choices were to seek terms of surrender that left the emperor on the throne or to offer fierce resistance, in the hopes that the American public would become weary of the war and accept surrender terms favorable to Japan. The atomic bomb changed the game for both nations.

As a result of the successful Trinity test on July 16 at Alamogordo, New Mexico, U.S. leaders activated plans for dropping the two existing atomic bombs on Japanese cities. At the Potsdam Conference, Groves informed Marshall about preparations for the bombing missions. MAGIC intercepts of Japanese diplomatic and military communications indicated to the allies that the Japanese leaders remained divided on the means of ending the war. On July 25, Marshall approved the missions for the atomic bombing of Japan.

While at dinner with his family at the Army-Navy Club on August 6, Groves received the first report that the mission to Hiroshima had left on schedule. He immediately returned to his office to await further developments. Around 11:15 pm, Colonel Frank McCarthy, Marshall’s aide, called Groves to say that the general wanted to know if there was any news on the strike. Groves responded that there was none. Shortly after McCarthy’s call, Groves received the coded strike message from General Farrell on Tinian. The mission’s crew reported:

Results clear cut, successful in all respects. Visible effects greater than New Mexico tests. Conditions normal in airplane following the delivery.8

As soon as the message was decoded, an excited Groves phoned McCarthy, who then gave Marshall the news and received Marshall’s tempered response, “Thank you very much for calling me.”

Japan announced its surrender on August 15, 1945, six days after a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki.

Marshall’s Nuclear Legacy

After the war, Truman’s selection of Marshall first as secretary of state and then as secretary of defense reflected his confidence in Marshall’s judgment and leadership. In these positions, Marshall continued to confront issues involving nuclear weapons, including the Berlin crisis, the Korean War, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. He believed that these weapons did not alleviate the need for a large conventional army and, while defending their use to end the war with Japan, he did not favor utilizing them in future wars. In an address to the United Nations assembly on September 17, 1948, he stated:

For the achievement of international security, and the well-being of the peoples of the world, it is necessary that the United Nations press forward on many fronts. Among these are the control of atomic and other weapons of mass destruction and has perhaps the highest priority if we are to remove the specter of a war of annihilation.9

As a conventional warrior, Marshall was skeptical of revolutionary technology in waging war. His view changed with the successful deployment of the atomic bomb on Japan. Inherently distrustful of wonder weapons, he nevertheless supported the Manhattan Project. Unsure that the atomic bomb would negate the need for invading Japan, he was surprised when it shocked the Japanese into surrendering. He believed the use of the atomic bomb ended the war, but realized that it posed a threat to the future of the world.

Dr. Frank A. Settle, professor emeritus of chemistry, Washington and Lee University and director of the ALSOS Digital Library for Nuclear Issues, was professor of chemistry at the Virginia Military Institute from 1964 to 1992. Before coming to W&L in 1998, he was a visiting professor at the U.S. Air Force Academy, a consultant at Los Alamos National Laboratory, and a program officer at the National Science Foundation. He is a co-author of Instrumental Methods of Analysis and the editor of The Handbook of Instrumental Analytical Techniques. He has published extensively in scientific, educational, and trade journals. At W&L he developed and taught courses on nuclear history, nuclear power, and weapons of mass destruction for liberal arts majors. This article contains excerpts from his new book, researched at the Marshall Library, General George C. Marshall and the Atomic Bomb to be published by Prager in spring 2016.

Rob Goldston: A Scientist on the Cutting Edge of Fusion and Arms Control Research

Professor Rob Goldston teaches in the areas of nuclear energy and non-proliferation at Princeton University. Rob is a leading researcher in plasma physics and fusion energy. He was director of the DOE Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL), 1997 – 2009. Since then he has published on the tradeoff between climate change mitigation by nuclear energy, fission and fusion, and nuclear proliferation risks. Recently he has collaborated with Professors Alexander Glaser of Princeton and Boaz Barak of Harvard on a Zero-Knowledge Protocol for warhead verification, for which the three were named “Leading Global Thinkers of 2014” by Foreign Policy magazine. He was acting director of the Princeton University Woodrow Wilson School Program on Science and Global Security during the Spring semester of 2015.

What inspired you to become a scientist? Was there a particular person or an event that put you on this path?

As far back as I can remember I was interested in physics, but one incident does stand out. The father of a fellow high school student was a laser physicist – back when those were rare – and he was invited to teach our 8:30 am physics class. We were so enthralled with what he could tell us about modern physics that we made him keep answering our questions until lunchtime. We cut all of the intervening classes.

What are the potential benefits of fusion energy?

Fusion has a number of potential benefits. Its fuel is abundant. It cannot melt down or run away. And its proliferation risks are small – if it is safeguarded.

What are the proliferation risks, if any, from fusion energy? What can and should be done to minimize those risks?

Proliferation risks are conventionally divided into use of clandestine facilities to produce fissile material, covert misuse of declared facilities for this purpose, and breakout. A DT [deuterium-tritium] fusion device capable of producing enough neutrons to transmute uranium or thorium to make 1 SQ [significant quantity1 worth of weapons material per year, while much smaller than a fusion power plant, is still quite large and would have very clear environmental signatures. So the risk of a clandestine facility making bomb material is small.

One could imagine, however, placing uranium or thorium targets in the vicinity of a neutron and power producing fusion plasma (the cloud of hot, ionized gas that is the fusion fuel). You would need to have safeguards to assure that no such material was present, but these would be relatively easy to implement, because the baseline amount is zero – so detection of any uranium, thorium or fission products would be a clear signature of misuse of the plant.

Finally, you could worry about breakout. The advantage of fusion is that even an unannounced breakout would be easily detected (again due to the presence of improper materials) and at the time of breakout there would be no fissile material yet produced. It would be relatively easy to disable a fusion power plant without risk of spreading radiation. I have written about these issues2 and others associated specifically with inertial confinement fusion3, and worked in an IAEA Consultative Group to suggest ways in which safeguards could best be deployed for fusion systems.

What more needs to be done to deploy the first commercially viable fusion energy power plant? How far away approximately is the world from achieving that breakthrough?

I think we know how to make commercial amounts of power from fusion, and this will be demonstrated by the ITER [Latin for “the way”] experiment now being built in France. ITER is slated to produce up to 500 MW of fusion power in pulses lasting between 400 seconds and an hour. The next challenge – which is my current area of research – is learning how the heat of the plasma escapes from the edge of the plasma45 and how to capture it most effectively. A parallel challenge is developing materials that can withstand the flux of 14 MeV neutrons from the DT reaction. In a sense our next challenges are set by our successes so far in making fusion power.

It is hard to say when all of this will come together. ITER should demonstrate major power production in the 2030s. We should bring along in parallel the other science and technology so that the device after ITER can put electricity on the grid. This is the structure of the plan that has been articulated in China, Europe, Japan and South Korea. In the U.S. we have been more reticent about articulating such a plan.

In particular, what advice would you give (or have you given) to the U.S. government (both the executive and legislative branches) to further advance the prospects for a commercial breakthrough in fusion energy?

I think that the U.S. needs to commit to being a commercial competitor in fusion energy, which means that we need a focused program with a set of specific goals and milestones. In particular, I think the winner in fusion will be the country that addresses the heat and neutron flux issues most effectively. We should be doing that in the U.S. while supporting the international ITER project, so that we can build a competitive pilot fusion power plant as soon as ITER succeeds.

Please describe in layperson’s terms what the “Zero Knowledge Protocol” is and how it can help address verification problems in nuclear arms control. Please describe the Consortium for Verification Technology.

A key issue for future arms control agreements will be for multi-national inspection teams to be able to verify that a nuclear warhead slated for dismantlement is truly a warhead, and one of the type specified. The problem is that this must be done without revealing anything about the design or composition of the warhead. (In other words, nuclear arms control should not facilitate nuclear proliferation!) Alex Glaser, Boaz Barak, and I have proposed a new interactive “Zero-Knowledge” technique6 to get around this apparent paradox. We propose that the inspectors would first select one or more warheads, randomly, from actively deployed missiles. At least one of these warheads, we assume, is a live one. If the inspectors are uncomfortable about this, they can select more. Then, say, 50 warheads are pulled out from storage. Now if the inspectors can prove to their satisfaction that these 50+ objects are identical, without learning anything about them, the problem is solved.

Our approach to this next step is a form of differential neutron radiography, and we are just now starting experiments on this at PPPL – using unclassified test objects. If we just were to take a neutron radiograph of a warhead, the resulting image would be highly classified. So our concept is that the owner of the warhead preloads the complement of this image onto an array of neutron detectors of a special type that record neutron fluence by producing small bubbles. Of course, the inspectors do not get to see these preloads either. However, when they irradiate a true warhead with neutrons that ultimately fall onto the preloaded array, the total signal at each detector should add up to a pre-agreed number of bubbles – the number that would have been produced with nothing there. So if we get an image of nothing – we have a real warhead! And we convey no information. The nice trick that made me fall in love with this idea is that if the preload is given a random Poisson distribution, there isn’t even information in the noisy speckle pattern on the image, since Poisson(n) + Poisson(m) = Poisson(n+m).

The astute reader, however, may have noticed a problem. Why can’t the owner of the warheads pull out a bag of rocks from storage, and give the inspectors a detector array preloaded with the complement of the bag of rocks? The answer – and this is where the interactive Zero-Knowledge feature comes in – is that the inspectors get to choose which preloaded array of detectors goes with which putative warhead. So the preload that is complementary to the bag of rocks could well end up behind a real warhead pulled off a missile. If we do this a few times, the odds that the warhead owner can get away with cheating are infinitesimal.

The Consortium on Verification Technology is a multi-institutional activity funded by the National Nuclear Security Administration of the Department of Energy. It provides funding for universities to collaborate with National Labs to work on a number of kinds of verification technology, not just associated with warheads. Princeton University and PPPL are members of this Consortium, working together on Zero-Knowledge warhead verification.

In early August, you joined 29 leading scientists in a letter7 to President Obama in support of the nuclear deal with Iran. Why did you sign the letter?

When I read the JCPOA, I was amazed at how strong it was. Viewed in the frame of other non-proliferation agreements, it is extremely innovative, very restrictive, and very well verified. I thought it was important for non-technical people to understand that this is indeed a very good deal – indeed the best that has ever been negotiated –and in absolute terms, able to get the job done. After 15 – 25 years of “good behavior” Iran will be constrained only as any other member in good standing of the NPT and signatory to its Additional Protocol is constrained, but this was inevitable after some period of time. As we said in the letter, and I have written separately, we need to strengthen the non-proliferation regime for the long run – and this deal gives us the time to do that.

What scientific opportunities do you think American scientists can pursue in collaboration with Iranian scientists?

JCPOA indicates that Iran is interested in fusion, and in particular in ITER. I would be very glad to welcome Iranian scientists to work on these.

What advice would you give fellow scientists who are considering applying their knowledge and skills to societal issues?

First of all, science is great fun. There is no thrill greater than understanding something deeply for the first time. If you are the first person in the world to understand it – that makes it a hundred times better. And if you can be solving societally important problems at the same time, what could be better?

Not Much Below the Surface? North Korea’s Nuclear Program and the New SLBM

In May 2015, only a month after key figures in the U.S. military publicly acknowledged the possibility that North Korea has perfected the miniaturization of a nuclear warhead for long-range delivery, the secretive country seems to have confirmed these claims with a series of announcements, including a “successful” submarine launched ballistic missile (SLBM) test at sea. 1, 2 While many experts question the authenticity of these claims, the latest announcements do warrant closer scrutiny, given their implications for regional stability and order. 4 We will begin our discussion with a technical analysis of the latest available evidence about North Korea’s missile technology. Note that we will not consider the claims related to miniaturization, given that there is little open source information to confirm or disprove these claims. Instead, we provide an assessment of the so-called “KN-11” based on official photographs and a video released by the North Korean KCNA. The results of our finding are inconclusive – meaning there is not enough evidence supporting (or refuting) the existence of a functional ICBM or SLBM in North Korea. In the second part of our discussion, we will explore North Korea’s intentions by considering the broader political context within which this latest set of announcements has been made. We argue that these moves correspond to past patterns of North Korean behavior and are likely to be driven by the leadership’s desire to seek attention and possibly draw the United States to the bargaining table whereby North Korea can win important concessions.

The Chain of Events

In early April of this year, Admiral William Gortney, the head of Northern Command and the North American Aerospace Defense, stated that the North Koreans “have the ability to put a nuclear weapon on a KN-08 and shoot it at the homeland. We assess that it’s operational today….” 4 During a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing one week later, both Admiral Samuel Locklear, the head of Pacific Command, and General Curtis Scapparotti, the commander of USFK, corroborated Admiral Gortney’s statement. 5 This is not the first time that these officials have made claims to these effects, 6but it is interesting to note that they come in succession while the debate over missile defense (i.e. THAAD [Terminal High Altitude Area Defense]) has been gaining momentum in Seoul. 7 Even more importantly, they are followed by a new set of announcements from North Korea about its nuclear program.

To be more precise, the North Korean Defense Commission announced on May 20th that they “have had the capability of miniaturizing nuclear warheads… for some time.”8 This claim was preceded by another announcement on May 9th whereby the North Korean state news agency KCNA claimed that “there took place an underwater test-fire of Korean-style powerful strategic submarine ballistic missile.”9 Putting aside for the moment the motives behind these announcements and the context surrounding these events, we consider the validity of this latest claim using the photographs and video released by the North Korean media which will provide some reliable assessments about North Korea’s delivery capability (see Figure 1).

A Picture is (Not) Worth a Thousand Words

As the saying goes, “a picture is worth a thousand words”. Thankfully, the North Korean media has released more than a single photograph of the SLBM launch, which means we can piece together quite an interesting story about the North Korean missile capability using this set of pictures. The video, which was released in early June – more than three weeks after the photos, in what appeared to be a response to early Western analyses – confirms this story.

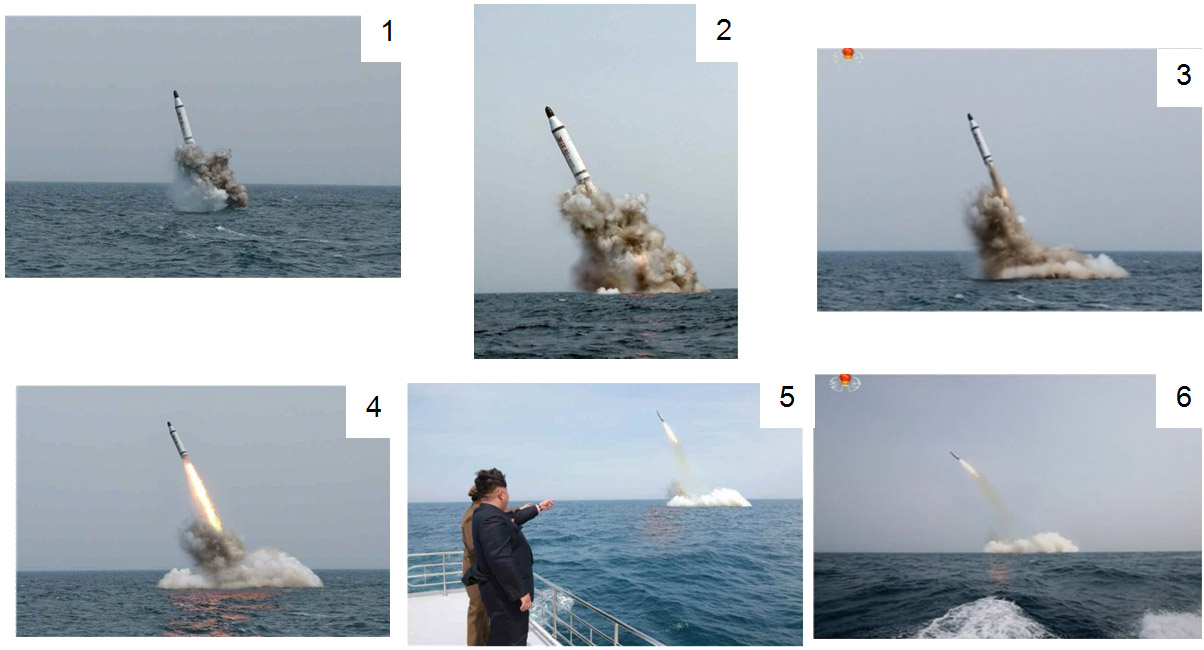

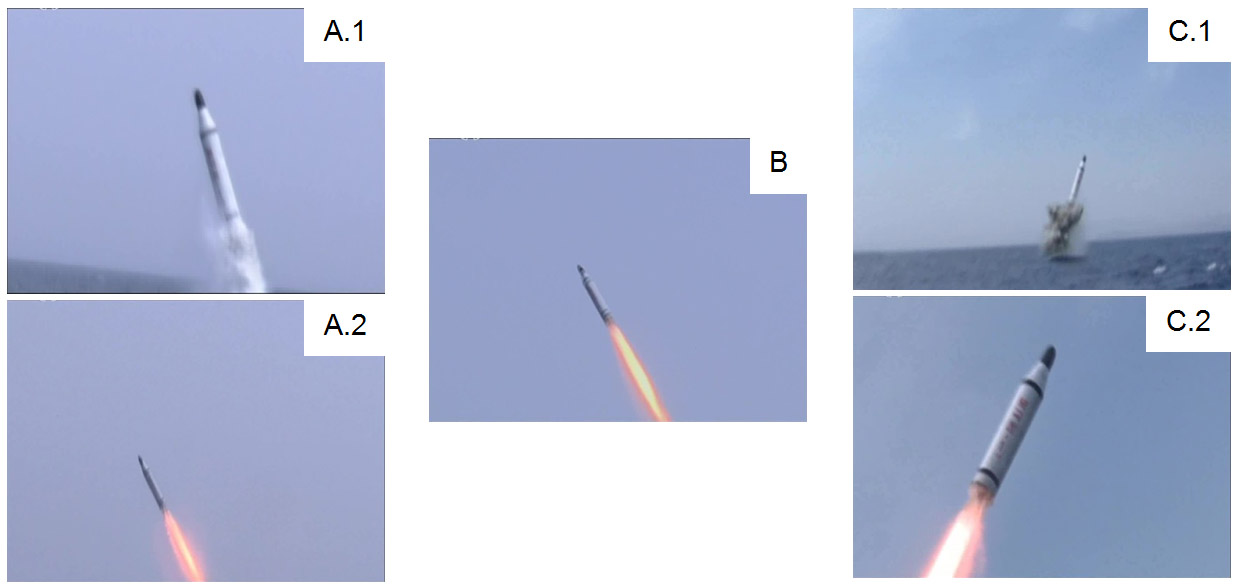

Figure 1. Selection of official launch photos

At first glance, the photos showing the North Korean leader Kim Jong-un observing the test appear to verify the official statement about an underwater missile launch. However, a closer scrutiny reveals that many of these photos were strongly modified. Therefore, technical details of this “missile” and its operational status have to remain unclear; what is clear, however, is that this event was not a full-scale launch of an operational SLBM.

Published Photographs

To date, six different launch photos have been identified from the set of photos that were officially released by North Korean media. 10 Although there may be more, these six are already sufficient for an analysis. The photos are hereby arbitrarily numbered, in this case according to the most likely chronological sequence (Figure 2).

Figure 2. KN-11 launch photos

Missile Characteristics at First Glance

The missile, by now designated the “KN-11” by Western analysts, looks quite similar to the Soviet R-27/SS-N-6 submarine missile that was developed in the 1960s. For more than 10 years now, North Korea is attributed with having access to the SS-N-6 technology, and even having developed a road-mobile version of this missile termed “Musudan”. However, no test of the Musudan has been observed as of yet, and there is no clear evidence that North Korea actually has access to this special kind of technology.

The presented SLBM seems to be a one-stage design with a length-to-diameter ratio of 6. This would mean a length of around 9 m for a diameter of roughly 1.5 m, which is consistent with the original SS-N-6 missile. With comparable size and technology, this missile could offer a performance of perhaps 2,400 km or more with a 650 kg warhead.

Nonetheless, it is important not to make too much out of this resemblance. Comparisons with the geometrical shape of the Chinese JL-1 missile, for example, also yield close similarities, but do not necessarily mean anything.

Launch Analysis

The early trajectory of missiles the size of an SS-N-6 has to be relatively steep for energetic reasons. SLBMs of this size might tilt at quite an angle just after clearing the water surface post submarine ejection, but they quickly readjust their angle to recover the steep trajectory once the engine is ignited. The photographs, however, reveal a different story. In this case, the missile’s trajectory already starts with a noteworthy angle instead of a vertical alignment, and this angle quickly continues to decline instead of recovering. This angled launch is typical for unguided missiles. It could also mean that this specific missile has low thrust or low acceleration.

The photographs also reveal some inconsistent information regarding the propellants used by this missile. The lack of a white smoke trail indicates that the missile does not use composite solid propellants. The lack of brownish-red nitric gases at ignition essentially rules out double-base solid propellants, as well as any liquid-propellant combinations with nitric acid or nitrogen tetroxide (NTO) as an oxidizer (for example, the combination of inhibited red fuming nitric acid (IRFNA) and kerosene). A blackish-grey cloud appears when the missile breaks the water surface and the cloud rapidly turns white; this is very unusual for any rocket launch, be it underwater or land launched. The shining exhaust flame also rules out unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH)-based propellant combinations, which are normally characterized by a transparent flame. In photograph #4, the shining flame seems to be detached from the nozzle by some distance, which in turn would actually indicate a double-base solid propellant. These inconsistencies suggest that there is something wrong with the photographs.

Photo Analysis

A detailed look at the available photographs reveals considerable irregularities and poor Photoshop edits.

Figure 3. KN-11 launch sequence

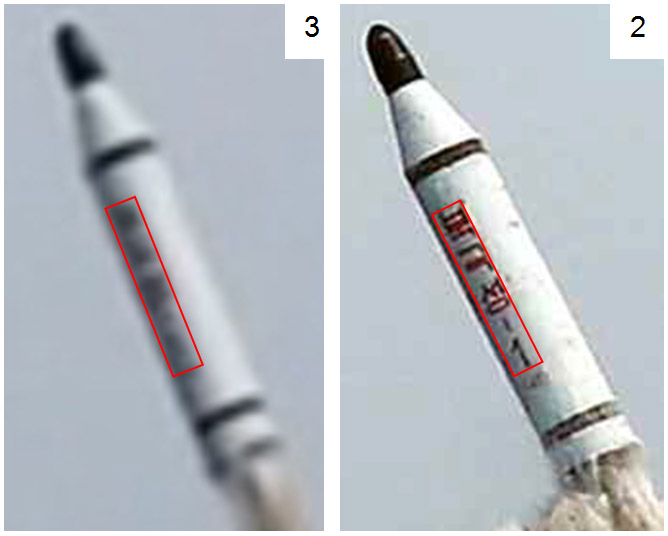

Figure 4. Identical position of letters and numbers

1. Photograph #2 is not part of the main photo sequence (Figure 3).

- The missile angle is lower than that of photographs #3 and #4; only at photograph #5, the missile starts to show a lower angle.

- If the pictures were not altered and we can assume that they are the same missile, the different angles can only be explained by a different camera position. Careful analysis shows that the red letters on the missile would have to be in a very different position due to the different perspective; however, they appear at the same position as in the other photos (Figure 4).

- The smoke cloud looks distinctly different from the other photos and also lacks the flat white spray water cloud.

- The smoke cloud touches down at the photo’s horizon line.

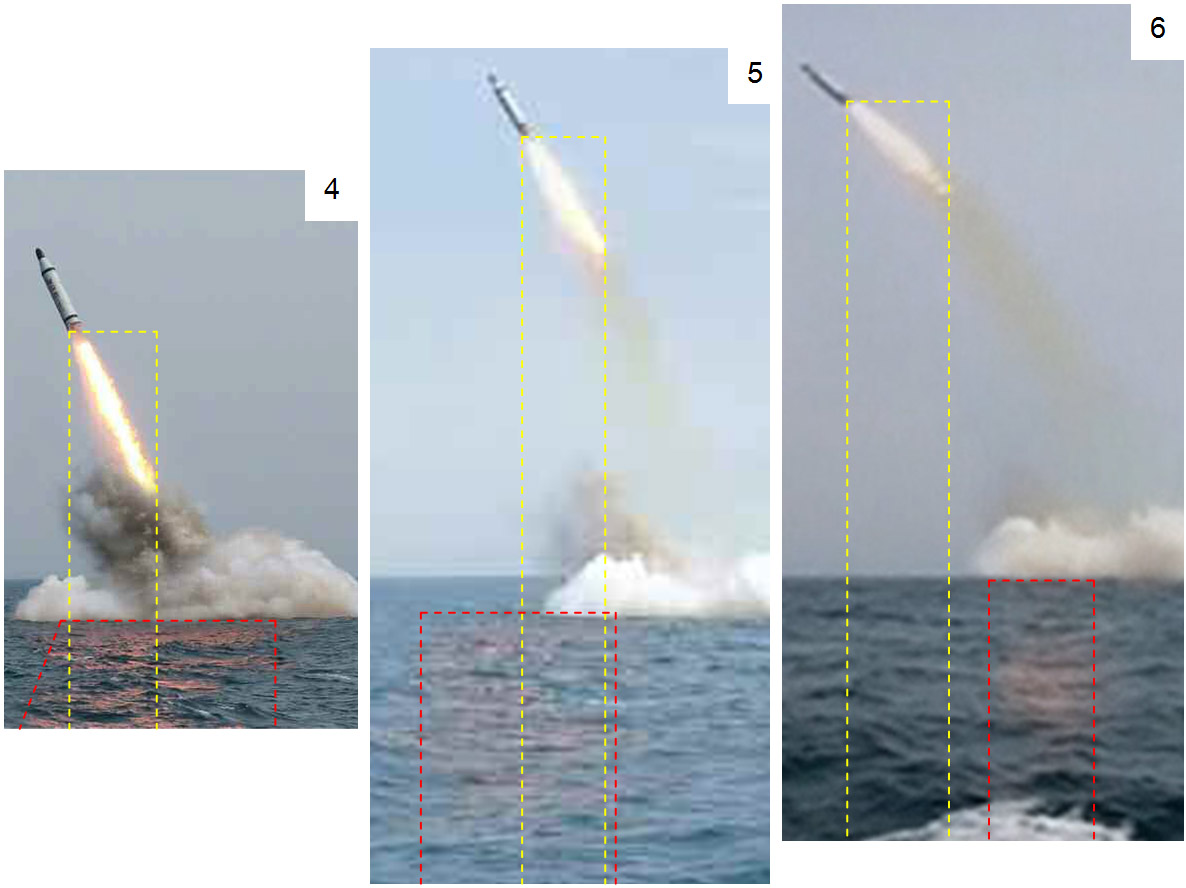

Figure 5. KN-11 exhaust flame reflection in the water

2. Photo 6 is also not part of the main photo sequence. The smoke cloud touches down at the photo’s horizon line, as well (Figure 3).

3. The dark smoke cloud dissipates rapidly from photographs #4 to #5 (Figure 3).

4. The reflection of the shiny exhaust flame in photographs #4, #5, and #6 are inconsistent (Figure 5).

- The reflection looks reddish. The flame itself is yellowish.

- The position of the flame reflection is of differing width, and also misplaced, shifting its relative position to the exhaust flame at each of the photos.

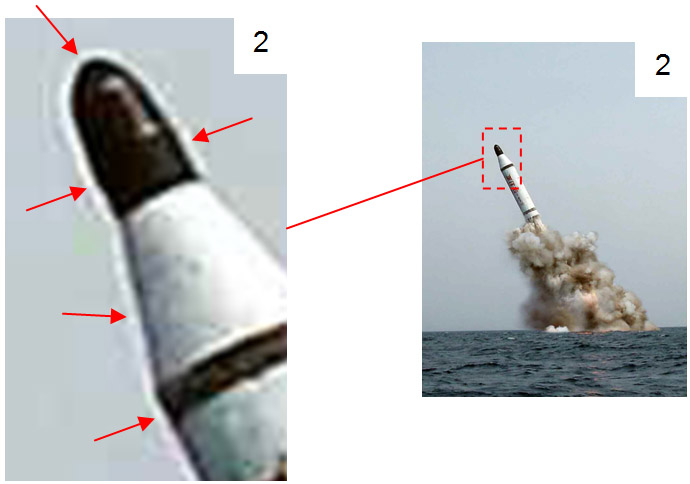

Figure 6. White line along the missile outline

5. There is a white line along parts of the missile in photograph #2 (Figure 6). This is most likely due to heavy photo editing.

6. A closer look at photograph #4 reveals very low-quality Photoshop work at the back end of the missile (Figure 7). Rectangular graphic blocks appear to have been inserted. The detached flame could be a result of this editing. Thus, any conclusions about the propellants derived from the exhaust flame are ambiguous.

Figure 7. Photoshop editing

Video Analysis

The brief video (of only 1:05 minutes) further shows Kim observing the test, including a total of 3 very short sequences showing a missile in flight (Figure 8). Sequences #A and #C actually consist of two sequences each, first showing the missile breaking through the ocean’s surface, and then quickly cutting to the missile in flight, while sequence #B only shows what looks like the missile in flight.

Figure 8. Launch video

sequence

Again, the video is not very convincing, and it appears that its intent is to create a different impression than what was actually shown.

1. The camera work is extremely shaky at sequences #A and #C, perhaps to make an analysis more difficult.

2. There is always a cut between the missile pushing through the surface of the water and the missile flying, thus disclosing the possibility that the in-flight sequences are not connected to the ejection sequences.

3. The dark smoke cloud at sequences #A and #C appears virtually out of nothing and starts disappearing just as quickly, within a few frames of the video (meaning within fractions of a second).

4. A blackish smoke cloud at ignition typically hints toward kerosene as a fuel, with a kerosene-rich ignition sequence. This was demonstrated by the Saturn V Moon rocket, for example, but no missile has yet been identified showing such a characteristic ignition cloud.

5. There is no way to ascertain the size of the missile depicted in the in-flight sequences, and if this is the same missile that was launched out of the water.

6. The length of the flame in the in-flight sequences is too long, more than two times the length of the missile body. Assuming a missile length of 9 m, the flame would be approximately 20 m. Comparable flame-missile length ratios are only known from small artillery rockets.

7. A later sequence just after #A, #B, and #C displays Kim in front of what appears to be the underwater launch site at the right half of the frame, marked by white water with traces of vapor or smoke still hanging in the air. Strangely, there is another area of white water a short distance to the left of the first area (Figure 9). Combining the size of this white water area, the distance of this area to the supposed launch site, and the trajectory of the ejected missile from the available photographs (Figure 3), it is possible that the ejected missile fell back into the ocean at this site.

Figure 9. Two white water areas

All this, along with some other inconsistencies, suggests that the released imagery and video footage was heavily edited by North Korean authorities.

Implied Aspects

The published photos apparently imply some aspects that fail to be validated with careful analysis.

Figure 10. Submarine and

surface ship

1. In several photographs, a submarine is clearly visible, surfaced in some photos and partially submerged in others. This would suggest that the missile was launched by this very submarine. But as was already pointed out on armscontrolwonk.com,11 a photo with a surface ship in close proximity to the launch site, as well as several other indications, point toward a submerged barge being used at this event as opposed to a submarine (Figure 10).

Figure 11. Smoke trail and smokeless missile

2. Another photo publicized on North Korean TV displays a thick white smoke trail high up in the sky, implying that a successful missile launch took place, and also indicating the use of composite solid propellants. However, there is no trace of a white smoke trail in any of the other available launch photographs (Figure 11) or the video.

Questioning Motives

As our discussion has revealed, the photographs and video both prove inadequate in providing a sufficient basis for concluding that North Korea has mastered the technology to enable long range delivery of a miniaturized nuclear warhead. If anything, they do not reveal any new information about the progress of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. What then might we conclude was the motive behind these announcements? Given the lack of adequate information, we can only speculate.

One possibility is that North Korea possesses a fully functional SLBM but does not want to put “all of their cards on the table”. That is, they may have modified their image productions to keep their true accomplishments clandestine. Of all conceivable scenarios, this is the least likely, given that the authorities could have accomplished the same objective by simply making an announcement without having released any photographs or video. In fact, we would argue that a simple announcement would have been superior to actually releasing any photographs or video footage, given that the poor editing work on these images only raises more questions and causes North Korea to look less credible in the eyes of many outside observers. In this sense, one could argue that these images have had the opposite of the intended effect.

Of course, there is also the possibility that North Korea is releasing bad signals to conceal its capabilities and has every intention of engaging in an armed conflict with the United States and its allies. We would argue that this scenario is only likely if the North Korean authorities truly believe that they can prevail against superior adversaries (i.e. the United States and its allies) in an all-out war. Given the number of instances where the United States has displayed its military prowess in recent years (e.g. Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya), it is difficult to see how the North Korean leadership could conceivably reach this kind of conclusion. Nonetheless, the possibility that the leadership is engaged in this type of thinking cannot be discounted altogether given the stakes of an armed conflict with North Korea.12 We think that this partially explains the cautionary words from a number of officials within U.S. military circles who have openly acknowledged the existence of a “functional ICBM” in North Korea.

But one could also argue that this was North Korea’s intention from the outset. Assuming that North Korea does not possess long-range strike capability, the “next best” option is to make its adversaries believe that it does. By being deliberately opaque and deceptive, North Korea could be trying to make the United States and its allies unable to choose between an option that involves the use of military force and one that does not. The goal in this scenario is to forestall an imminent attack by keeping its adversaries guessing. Given the recent set of announcements by the U.S. military, one could argue that North Korea is succeeding with this strategy.

There is another scenario where North Korea does not possess long-range strike capability but is instead using these announcements to signal that it intends to develop this technology and subsequently demonstrate how far along it may be in this process. On the one hand, this achieves some of the objectives laid out above, but it also impels the United States and its allies to weigh the possibility of a diplomatic solution to North Korea’s nuclear program. The thinking would run along the following lines: “Given that North Korea has not fully perfected its nuclear capability, could it be possible to negotiate a deal with them in order to halt or delay this process?” This appears to be the guiding principle behind past deals with North Korea and even the current deal with Iran.

The likelihood that North Korea’s strategic logic may follow this line of reasoning is backed by several contextual factors surrounding the recent set of events, as well as a pattern of past practices that corroborates this type of behavior. First and foremost, we must recognize that the targeted recipient of this signal is the United States. Undeniably, North Korea having possession of a nuclear-tipped ICBM sends a strong message to the world, but the intended target of this capability must be none other than the United States, (the greatest threat for North Korea presently). If the United States perceives these images as serious threats to homeland security, U.S. leaders are likely to act. North Korea is staking that the reaction will not involve the use of military force, since the cost of an armed conflict would be too high for the allies, so this leaves open the possibility of diplomatic engagement. Recent moves by the Obama administration to normalize relations with Cuba and finalize a nuclear deal with Iran may have caught Pyongyang’s attention. While the comparison is hardly apropos, the latest SLBM announcement would be one way for Pyongyang to test the allies’ resolve to “stay the course” or revive the Six Party Talks.

An increase in the number of meetings between officials in China, Japan, Russia, South Korea and the United States over the past several months suggests that this “bet” may be paying off. Aside from the fact that South Korean President Park Geun-hye expressed her desire to resume talks with North Korea on several occasions – (the latest being January of this year), there has been a significant upswing in the number of meetings among chief negotiators in the United States, South Korea, and Japan in recent months. But what of China and Russia? As early as March of this year, both countries expressed a willingness to reopen talks, and the chief negotiators appear to be reaching out to their counterparts in these countries.13 While it is unclear how long this consensus may last given the continuing evolution of North Korea’s nuclear program, the latest SLBM test seems to have created some sense of urgency and momentum on the diplomatic side.

Finally, North Korea’s relation with its closest ally in China is deteriorating with each additional test, inviting further rebuke and concern.14 Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Seoul last year marked the first time in history that a Chinese leader visited Seoul without having first visited Pyongyang.15 This change explains North Korea’s interest in improving relations with Russia. It is unclear, however, whether Russia will serve as a more reliable surrogate, as it currently appears to be mired in an economic crisis of its own. Given all this, the conditions are ripe for North Korea to turn instead towards gaining back the attention of its old adversaries. What better way to achieve this than by test launching a SLBM in its development phase?

What of the possibility that North Korea is reacting to the recent military exercises in the region by the US-ROK forces? One could argue that the latest test was a reaction to Key Resolve and Foal Eagle, which took place in March. Indeed, Pyongyang sees these annual U.S. and South Korean military exercises as more than irritable saber-rattling, but that they also warrant vitriolic complaints. Nonetheless they have responded with drills of their own, including firing rounds of mortars on the open sea. And two months is much too long of a delay for a response in the form of a poorly-staged mock SLBM launch.

Perhaps one can formulate a better argument that accounts for North Korea’s broader security dilemma. We cannot lose sight of the fact that North Korea’s desire to build a nuclear arsenal is largely based on its perception of the threat that the United States and U.S. allies pose for North Korea’s national security. Hence, we should not ignore the possibility that North Korea’s nuclear ambition is set on an irreversible course. If this were the case, North Korea would continue the development of its nuclear program with or without diplomatic overtures, which has been the case in the past. In this scenario, negotiations are not going to be effective in halting or delaying North Korea’s nuclear program.

So the question remains: why the announcements? It is important to note that these announcements come on the heels of public statements by high-ranking officers within the U.S. military, which confirms (if not overestimates) North Korea’s nuclear capability. If the goal was to impress, there was no need for North Korea to release these photographs because the U.S. military was already doing it for them. Perhaps the North Korean authorities thought that these images and announcements would reinforce these assessments. But if this was their primary objective, our analysis has shown that they have failed. Even if they were successful in convincing the world that they possess a fully functional SLBM, what then? Is this their way of taunting their enemies into war? Undoubtedly, instigating a military response is not in the North Korean regime’s interest unless it is about to implode on its own.

Perhaps these images were never meant for consideration outside of North Korea. That is, the circulation of these images may have been a way to raise domestic support and national pride for the Kim Jong-un regime’s accomplishments. There is something to be said about the effect that these images have on the domestic audience in North Korea. But it is difficult to believe that the regime would need to go through all this trouble simply to raise public support when it has other means to maintain and manage its own legitimacy. Domestic appeal is most likely just a part of a broader agenda for a staged event such as this.

This brings us back to the hypothesis that North Korea may be signaling a readiness to talk. As we have discussed, these images achieve two objectives. First, they assist North Korea in further reinforcing the perception that it is developing the ability to deter its foes from exercising the military option. Second, they push the United States and its allies to consider a diplomatic response to North Korea’s nuclear problem. Already, some pundits are suggesting that the Obama administration should consider a different approach.16 However, the success of the diplomatic approach would depend on North Korea’s willingness to negotiate over the U.S. demand for verifiable denuclearization, which is a rather difficult proposition. Should North Korea be unwilling to accept these terms, the next question would be whether the United States and its allies would accept North Korea as a nuclear weapons state—which would be an equally difficult proposition that would depend on the likelihood of installing a sophisticated combination of conventional offensive and defensive capabilities based in South Korea or Japan. However, it is clear that until this impasse is somehow resolved, North Korea will continue its slow but defiant march towards attaining an arsenal of long-range missiles tipped with miniaturized nuclear warheads. Which begs the question: what would the United States and its allies do then?

Conclusion

North Korea’s latest announcement regarding its nuclear capability should not be taken lightly. It has revealed the Kim Jong-un regime’s desire and intention to continue the development of its nuclear weapons program. The silver lining, of course, is that there is no verifiable proof that North Korea possesses a functional SLBM or ICBM tipped with a miniaturized nuclear warhead just yet. The latest revelation of the KN-11 corresponds with the broader pattern of claiming significant advances in missile technology while trying to substantiate them with contradictory proof. Poor mock-ups of the KN-08 missile that were paraded through Pyongyang in 2012 and 2013 are just one of many examples.17 We have considered several explanations for why North Korea may be engaged in this kind of enterprise. While we think that diplomatic engagement is the most plausible motive behind the latest announcements, there are significant hurdles that the negotiators must overcome if this approach is to bear fruit.

It is also important to bear in mind that there may be other factors motivating the display of these mock-ups. For instance, we should not rule out the possibility that the North Korean leadership may be made to believe that its own missile program is more advanced than it really is, simply out of fear of not meeting given objectives – the fate of the late North Korean Defense Minister, Hyong Yong Chol, who was reportedly executed by antiaircraft fire for falling asleep at military events, indicates what the consequences might be if the Supreme Leader is not pleased. Whatever the case, it is resoundingly clear that North Korea wants to possess this capability. The recent rise in the number of missile tests suggests that they are redoubling their effort18 – meaning that we have not seen the last of these types of announcements in looking ahead.

Until there is some break in this trend, the best that we can do is continued observation and study. To gain insights on the reasons for North Korea’s announcements about its missile program, it is essential to closely follow any missile related developments in the future, but also to frequently revisit past developments and events to gain a better and more comprehensive sense of North Korea’s missile story.19

Markus Schiller holds degrees in mechanical and aerospace engineering from TU Munich. He was employed at Schmucker Technologie since 2006, except for a one-year Fellowship at the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, California, in 2011. In 2015, he started his own consulting firm ST Analytics, focusing on space technology, security and threat, and – of course – rockets and missiles.

Robert Schmucker has more than five decades of experience researching rocketry, missiles, and astronautics. In the 1990s, he was a weapons inspector for UNSCOM in Iraq. His consulting firm, Schmucker Technologie, provided threat and security analyses for national and international organizations about activities of developing countries and proliferation for more than 20 years.

James Kim is a research fellow at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies and an adjunct lecturer in the Executive Master of Public Policy and Administration program at Columbia University. He has held positions at the California State Polytechnic University (Pomona), the RAND Corporation, and the Institute for Social and Economic Research and Planning at the School of International and Public Affairs in Columbia University.

Nuclear War, Nuclear Winter, and Human Extinction

While it is impossible to precisely predict all the human impacts that would result from a nuclear winter, it is relatively simple to predict those which would be most profound. That is, a nuclear winter would cause most humans and large animals to die from nuclear famine in a mass extinction event similar to the one that wiped out the dinosaurs.

Following the detonation (in conflict) of US and/or Russian launch-ready strategic nuclear weapons, nuclear firestorms would burn simultaneously over a total land surface area of many thousands or tens of thousands of square miles. These mass fires, many of which would rage over large cities and industrial areas, would release many tens of millions of tons of black carbon soot and smoke (up to 180 million tons, according to peer-reviewed studies), which would rise rapidly above cloud level and into the stratosphere. [For an explanation of the calculation of smoke emissions, see Atmospheric effects & societal consequences of regional scale nuclear conflicts.]

The scientists who completed the most recent peer-reviewed studies on nuclear winter discovered that the sunlight would heat the smoke, producing a self-lofting effect that would not only aid the rise of the smoke into the stratosphere (above cloud level, where it could not be rained out), but act to keep the smoke in the stratosphere for 10 years or more. The longevity of the smoke layer would act to greatly increase the severity of its effects upon the biosphere.

Once in the stratosphere, the smoke (predicted to be produced by a range of strategic nuclear wars) would rapidly engulf the Earth and form a dense stratospheric smoke layer. The smoke from a war fought with strategic nuclear weapons would quickly prevent up to 70% of sunlight from reaching the surface of the Northern Hemisphere and 35% of sunlight from reaching the surface of the Southern Hemisphere. Such an enormous loss of warming sunlight would produce Ice Age weather conditions on Earth in a matter of weeks. For a period of 1-3 years following the war, temperatures would fall below freezing every day in the central agricultural zones of North America and Eurasia. [For an explanation of nuclear winter, see Nuclear winter revisited with a modern climate model and current nuclear arsenals: Still catastrophic consequences.]

Nuclear winter would cause average global surface temperatures to become colder than they were at the height of the last Ice Age. Such extreme cold would eliminate growing seasons for many years, probably for a decade or longer. Can you imagine a winter that lasts for ten years?

The results of such a scenario are obvious. Temperatures would be much too cold to grow food, and they would remain this way long enough to cause most humans and animals to starve to death.

Global nuclear famine would ensue in a setting in which the infrastructure of the combatant nations has been totally destroyed, resulting in massive amounts of chemical and radioactive toxins being released into the biosphere. We don’t need a sophisticated study to tell us that no food and Ice Age temperatures for a decade would kill most people and animals on the planet. Would the few remaining survivors be able to survive in a radioactive, toxic environment?

It is, of course, debatable whether or not nuclear winter could cause human extinction. There is essentially no way to truly “know” without fighting a strategic nuclear war. Yet while it is crucial that we all understand the mortal peril that we face, it is not necessary to engage in an unwinnable academic debate as to whether any humans will survive.

What is of the utmost importance is that this entire subject –the catastrophic environmental consequences of nuclear war – has been effectively dropped from the global discussion of nuclear weaponry. The focus is instead upon “nuclear terrorism”, a subject that fits official narratives and centers upon the danger of one nuclear weapon being detonated – yet the scientifically predicted consequences of nuclear war are never publically acknowledged or discussed.

Why has the existential threat of nuclear war been effectively omitted from public debate? Perhaps the leaders of the nuclear weapon states do not want the public to understand that their nuclear arsenals represent a self-destruct mechanism for the human race? Such an understanding could lead to a demand that nuclear weapons be banned and abolished.

Consequently, the nuclear weapon states continue to maintain and modernize their nuclear arsenals, as their leaders remain silent about the ultimate threat that nuclear war poses to the human species.

Steven Starr is the director of the University of Missouri’s Clinical Laboratory Science Program, as well as a senior scientist at the Physicians for Social Responsibility. He has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and the Strategic Arms Reduction (STAR) website of the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology; he also maintains the website Nuclear Darkness. Starr also teaches a class on the Environmental, Health and Social Effects of nuclear weapons at the University of Missouri.

Exceptions to the “No Comment” Rule on Nuclear Weapons

In response to public inquiries about the location of nuclear weapons, Department of Defense officials are normally supposed to respond: “It is U.S. policy to neither confirm nor deny the presence or absence of nuclear weapons at any general or specific location.”

Remarkably, “This response must be provided even when such location is thought to be known or obvious,” according to a DoD directive that was issued this week.

But there are exceptions to the rule, noted in the directive.

In the case of a nuclear weapons or radiological accident or incident within the United States, DoD personnel “are required to confirm to the general public the presence or absence of nuclear weapons… in the interest of public safety or to reduce or prevent widespread public alarm.”

“Notification of public authorities also is required if the public is, or may be, in danger of radiation exposure or other threats posed by the weapon or its components.”

See Nuclear-Radiological Incident Public Affairs (PA) Guidance, DoD Instruction 5230.16, October 6, 2015.

Tolman Reports on Declassification Now Online

This week the Department of Energy posted the first declassification guidance for nuclear weapons-related information, known as the Tolman Committee reports, prepared in 1945-46. The Tolman reports were an early and influential effort to conceptualize the role of declassification of atomic energy information and the procedures for implementing it. Though the reports themselves were declassified in the 1970s, they have not been readily available online until now.

US Drops Below New START Warhead Limit For The First Time

By Hans M. Kristensen

The number of U.S. strategic warheads counted as “deployed” under the New START Treaty has dropped below the treaty’s limit of 1,550 warheads for the first time since the treaty entered into force in February 2011 – a reduction of 263 warheads over four and a half years.

Russia, by contrast, has increased its deployed warheads and now has more strategic warheads counted as deployed under the treaty than in 2011 – up 111 warheads.

Similarly, while the United States has reduced its number of deployed strategic launchers (missiles and bombers) counted by the treaty by 120, Russia has increased its number of deployed launchers by five in the same period. Yet the United States still has more launchers deployed than allowed by the treaty (by 2018) while Russia has been well below the limit since before the treaty entered into force in 2011.

These two apparently contradictory developments do not mean that the United States is falling behind and Russia is building up. Both countries are expected to adjust their forces to comply with the treaty limits by 2018.

Rather, the differences are due to different histories and structures of the two countries’ strategic nuclear force postures as well as to fluctuations in the number of weapons that are deployed at any given time.

Deployed Warhead Status

The latest warhead count published by the U.S. State Department lists the United States with 1,538 “deployed” strategic warheads – down 60 warheads from March 2015 and 263 warheads from February 2011 when the treaty entered into force.

But because the treaty artificially counts each bomber as one warhead, even though the bombers don’t carry warheads under normal circumstances, the actual number of strategic warheads deployed on U.S. ballistic missiles is around 1,450. The number fluctuates from week to week primarily as ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) move in and out of overhaul.

Russia is listed with 1,648 deployed warheads, up from 1,537 in 2011. Yet because Russian bombers also do not carry nuclear weapons under normal circumstances but are artificially counted as one warhead per bomber, the actual number of Russian strategic warheads deployed on its ballistic missiles is closer to 1,590 warheads.

Because it has fewer ICBMs than the United States (see below), Russia is prioritizing deployment of multiple warheads on its new intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). In contrast, the United States has downloaded its ICBMs to carry a single warhead – although the missiles retain the capability to load the warheads back on if necessary. And the next-generation missile (GBSD; Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent) the Air Force plans to deploy a decade from now will also be capable of carry multiple warheads.

Warheads from the last MIRVed U.S. ICBM are moved to storage at Malmstrom AFB in June 2014. The sign “MIRV Off Load” has been altered from “Wide Load” on the original photo. Image: US Air Force.

This illustrates one of the deficiencies of the New START Treaty: it does not limit how many warheads Russia and the United States can keep in storage to load back on the missiles. Nor does it limit how many of the missiles may carry multiple warheads.

And just a reminder: the warheads counted by the New START Treaty are not the total arsenals or stockpiles of the United States and Russia. The total U.S. stockpile contains approximately 4,700 warheads (with another 2,500 retired but still intact warheads awaiting dismantlement. Russia has a stockpile of approximately 4,500 warheads (with perhaps 3,000 more retired warheads awaiting dismantlement).

Deployed Launcher Status

The New START Treaty count lists a total of 762 U.S. deployed strategic launchers (ballistic missiles and long-range bombers), down 23 from March 2015 and a total reduction of 120 launchers since 2011. Another 62 launchers will need to be removed before February 2018.

Four and a half years after the treaty entered into force, the U.S. military is finally starting to reduce operational nuclear launchers. Up till now all the work has been focused on eliminating so-called phantom launchers, that is launchers that were are no longer used in the nuclear mission but still carry some equipment that makes them accountable. But that is about to change.

On September 17, the Air Force announced that it had completed denuclearization of the first of 30 operational B-52H bombers to be stripped of their nuclear equipment. Another 12 non-deployed bombers will also be denuclearized for a total of 42 bombers by early 2017. That will leave approximately 60 B-52H and B-2A bombers accountable under the treaty.

The Air Force is also working on removing Minuteman III ICBMs from 50 silos to reduce the number of deployed ICBMs from 450 to no more than 400. Unfortunately, arms control opponents in the U.S. Congress have forced the Air Force to keep the 50 empted silos “warm” so that missiles can be reloaded if necessary.

Finally, this year the Navy is scheduled to begin inactivating four of the 24 missile tubes on each of its 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. The work will be completed in 2017 to reduce the number of deployed sea-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) to no more than 240, down from 288 missiles today.

Russia is counted with 526 deployed launchers – 236 less than the United States. That’s an addition of 11 launchers since March 2015 and five launchers more than when New START first entered into force in 2011. Russia is already 174 deployed launchers below the treaty’s limit and has been below the limit since before the treaty was signed. So Russia is not required to reduce any more deployed launchers before 2018 – in fact, it could legally increase its arsenal.

Yet Russia is retiring four Soviet-era missiles (SS-18, SS-19, SS-25, and SS-N-18) faster than it is deploying new missiles (SS-27 and SS-N-32) and is likely to reduce its deployed launchers more over the next three years.

Russia is also introducing the new Borei-class SSBN with the SS-N-32 (Bulava) SLBM, but slower than previously anticipated and is unlikely to have eight boats in service by 2018. Two are in service with the Northern Fleet (although one does not appear fully operational yet) and one arrived in the Pacific Fleet last month. The Borei SSBNs will replace the old Delta III SSBNs in the Pacific and later also the Delta IV SSBNs in the Northern Fleet.

Russian Borei- and Delta IV-class SSBNs at the Yagelnaya submarine base on the Kola Peninsula. Click to open full size image.

The latest New START data does not provide a breakdown of the different types of deployed launchers. The United States will provide a breakdown in a few weeks but Russia does not provide any information about its deployed launchers counted under New START (nor does the U.S. Intelligence Community say anything in public about what it sees).

As a result, we can’t see from the latest data how many bombers are counted as deployed. The U.S. number is probably around 88 and the Russian number is probably around 60, although the Russian bomber force has serious operational and technical issues. Both countries are developing new strategic bombers.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Four and a half years after the New START Treaty entered into force in 2011, the United States has reduced its “accountable” deployed strategic warheads below the limit of 1,550 warheads for the first time. The treaty limit enters into effect in February 2018.

Russia has moved in the other direction and increased its “accountable” deployed strategic warheads and launchers since the treaty entered into force in 2011. Not by much, however, and Russia is expected to reduce its deployed strategic warheads as required by the New START Treaty by 2018. Russia is not in a build-up but in a transition from Soviet-era weapons to newer types that causes temporary fluctuations in the warhead count. And Russia is far below the treaty’s limit on deployed strategic launchers.

Yet it is disappointing that Russia has allowed its number of “accountable” deployed strategic warheads to increase during the duration of the treaty. There is no need for this increase and it risks fueling exaggerated news media headlines about a Russian nuclear “build-up.”

Overall, however, the New START reductions are very limited and are taking a long time to implement. Despite souring East-West relations, both countries need to begin to discuss what will replace the treaty after it enters into effect in 2018; it will expire in 2021 unless the two countries agree to extend it for another five years. It is important that the verification regime is not interrupted and failure to agree on significantly lower limits before the next Non-Proliferation Treaty review conference in 2020 will hurt U.S. and Russian status.

Moreover, defining lower limits early rather than later is important now to avoid that nuclear force modernization programs already in full swing in both countries are set higher (and more costly) than what is actually needed for national security.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Understanding the Dragon Shield: Likelihood and Implications of Chinese Strategic Ballistic Missile Defense

While China has received growing attention for modernizing and expanding its strategic offensive nuclear forces over the last ten years, little attention has been paid to Chinese activities in testing and developing ballistic missile defenses (BMD). Motivated to understand the strategic implications of this testing and to learn Chinese views, Adjunct Senior Fellow and Professor, Bruce MacDonald and FAS President, Dr. Charles Ferguson, over the past twelve months, have studied these issues and have had extensive discussions with more than 50 security experts in China and the United States. Ever since the end of the Cold War, U.S. security policy has largely assumed that only the United States would possess credible strategic ballistic missile defense capabilities with non-nuclear interceptors. This tacit assumption has been valid for the last quarter century but may not remain valid for long. Since 2010, China has been openly testing missile interceptors purportedly for BMD purposes, but also useful for anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons.

A full PDF version of the report can be found here.

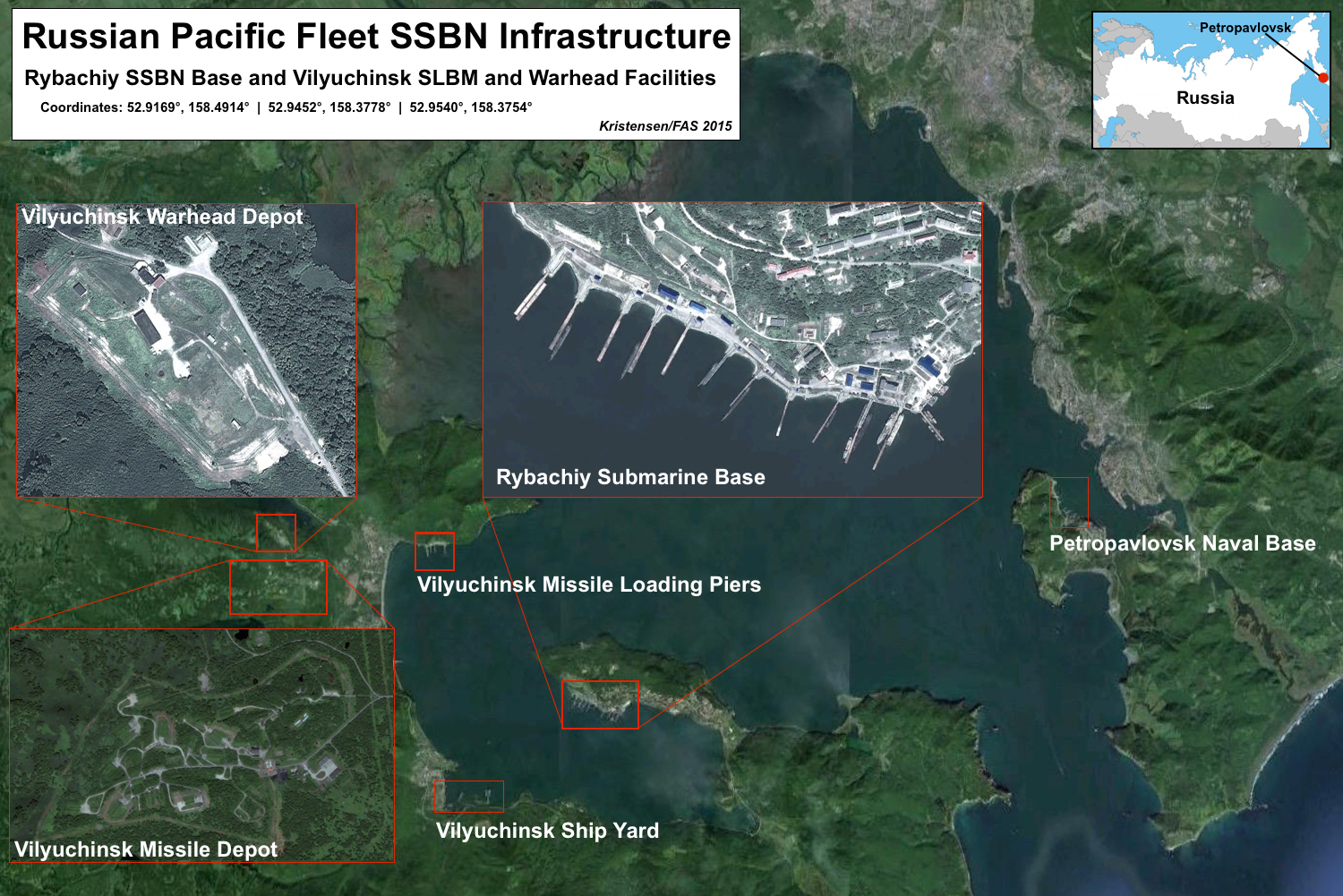

Russian Pacific Fleet Prepares For Arrival of New Missile Submarines

Later this fall (possibly this month) the first new Borei-class (sometimes spelled Borey) nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) is scheduled to arrive at the Rybachiy submarine base near Petropavlovsk on the Kamchatka Peninsula.

[Update September 30, 2015: Captain First Rank Igor Dygalo, a spokesperson for the Russian Navy, announced that the Aleksander Nevsky (K-550) arrived at Rybachiy Submarine Base at 5 PM local time (5 AM GMT) on September 30, 2015.]

At least one more, possibly several, Borei SSBNs are expected to follow over the next few years to replace the remaining outdated Delta-III SSBNs currently operating in the Pacific.

The arrival of the Borei SSBNs marks the first significant upgrade of the Russian Pacific Fleet SSBN force in more than three decades.

In preparation for the arrival of the new submarines, satellite pictures show upgrades underway to submarine base piers, missile loading piers, and nuclear warhead storage facilities.

Several nuclear-related facilities near Petropavlovsk are being upgraded.

Upgrade of Rybachiy Submarine Base Pier

Similar to upgrades underway at the Yagelnaya Submarine Base to accommodate Borei-class SSBNs in the Northern Fleet on the Kola Peninsula, upgrades visible of submarine piers at Rybachiy Submarine Base are probably in preparation for the arrival of the first Borei SSBN – the Aleksandr Nevskiy (K-550) in the near future (see below).

Upgrades at Rybachiy submarine base.

Commercial satellite images from 2014 show a new large pier under construction. The pier includes six large pipes, probably for steam and water to maintain the submarines and their nuclear reactors while in port.

The image also shows two existing Delta III SSBNs, one with two missile tubes open and receiving service from a large crane. Other visible submarines include a nuclear-powered Oscar-II class guided missile submarine, a nuclear-powered Victor III attack submarine, and a diesel-powered Kilo-class submarine.

The arrival of the Borei-class in the Pacific has been delayed for more than a year because of developmental delays of the Bulava missile (SS-N-32) and the SSBN construction program. Russian Deputy Defence Minister Ruslan Tsalikov recently visited the base and promised that infrastructure and engineering work for the Borei-class SSBNs would be completed in time for the arrival of the Aleksander Nevsky (K-550). Predictions for arrival range from early- to late-September 2015.

Upgrade of Missile Depot Loading Pier

When not deployed onboard SSBNs, sea-launched ballistic missiles and their warheads are stored at the Vilyuchinsk missile deport and warhead storage site across the bay approximately 8 kilometers (5 miles) east-northwest of the Rybachiy submarine base. To receive and offload missiles and warheads, an SSBN will moor at one of two piers where a large floating crane is used to lift missiles into or out of the submarine’s 16 launch tubes.

Upgrades of Vilyuchinsk missile loading piers.

Satellite images show that a larger third pier is under construction possibly to accommodate the Borei SSBNs and the Bulava SLBM loadings (see above). This will also provide additional docking space for both submarines and surface ships that use the facility.

SS-N-18 handling at Vilyuchinsk missile loading pier.

The missile depot itself includes approximately 60 earth-covered bunkers (igloos) and a number of service facilities located inside a 2-kilometer (1.3- mile) long, multi-fenced facility covering an area of 2.7 square kilometer (half a square mile). The igloos have large front doors that allow SLBMs to be rolled in for horizontal storage inside the climate-controlled facilities (see image below).

Vilyuchinsk missile depot.

In addition to SLBMs for SSBNs, the depot probably also stores cruise missiles for attack submarines and surface ships. A supply ship will normally load the missiles at Vilyuchinsk and then deliver them to the attack submarine or surface ship back at their base piers. However, most of the Russian surface fleet in the Pacific is based at Vladivostok, some 2,200 kilometers (1,400 miles) to the southwest near North Korea, and has its own nuclear weapons storage sites.

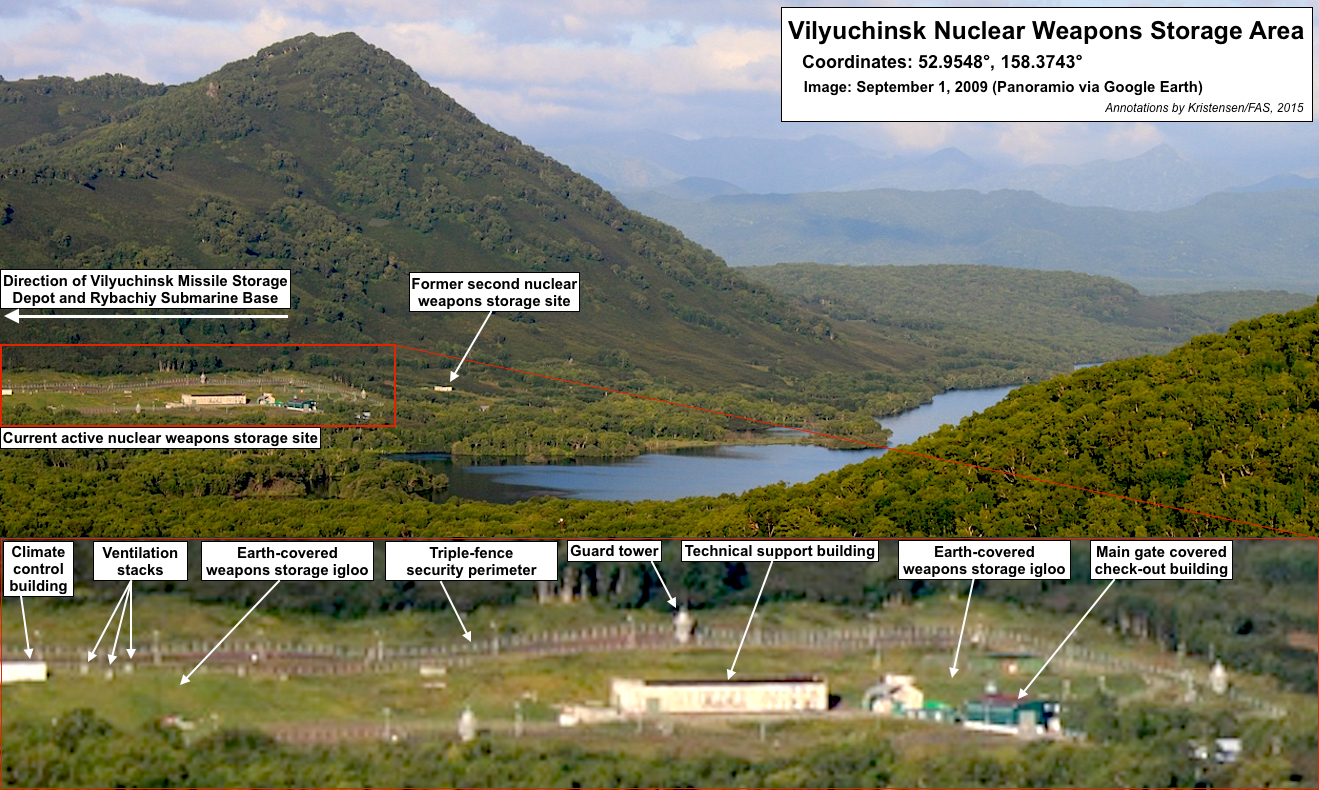

Upgrade of Warhead Storage Site