New START Numbers Show Importance of Extending Treaty

By Hans M. Kristensen

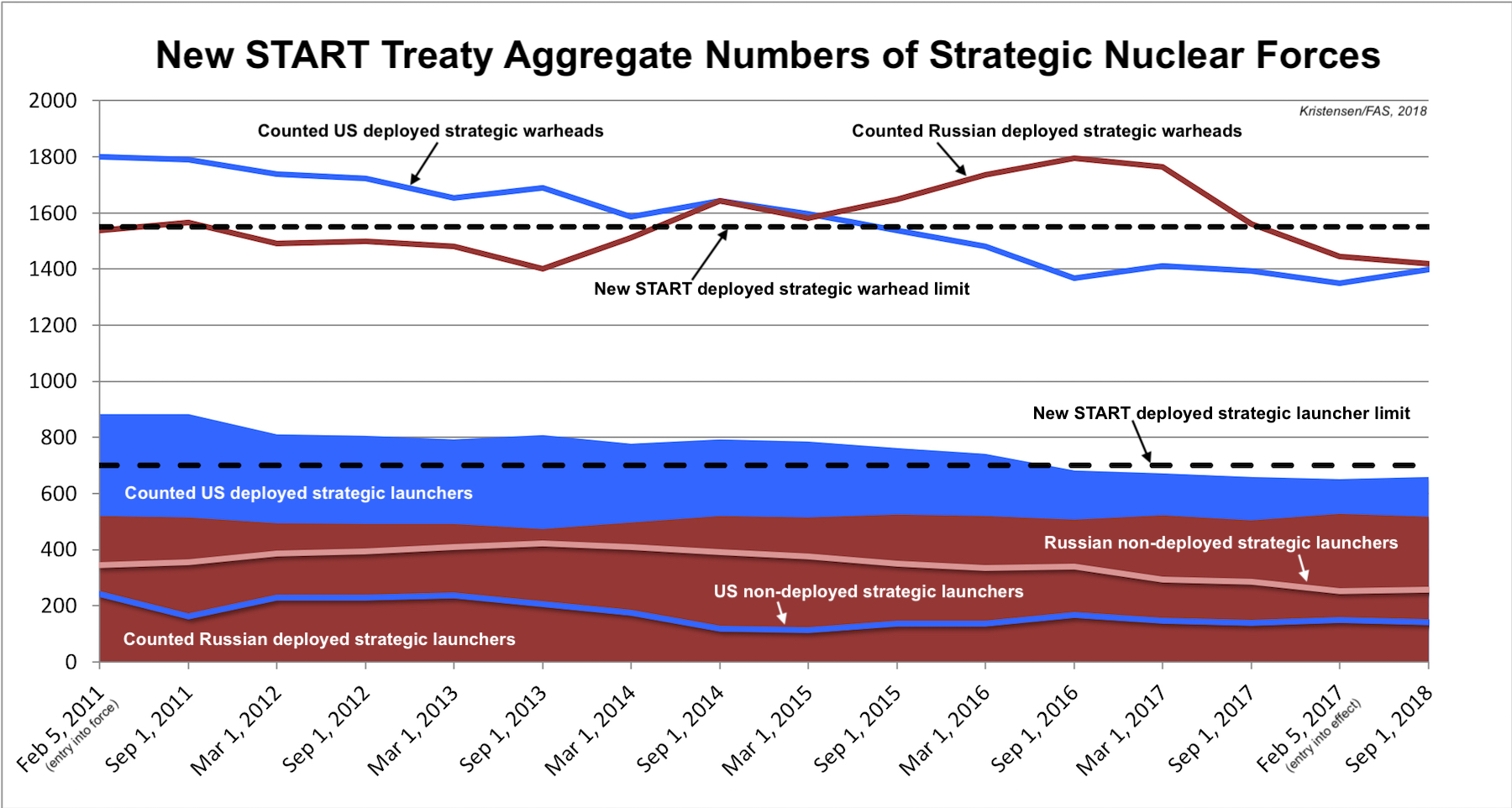

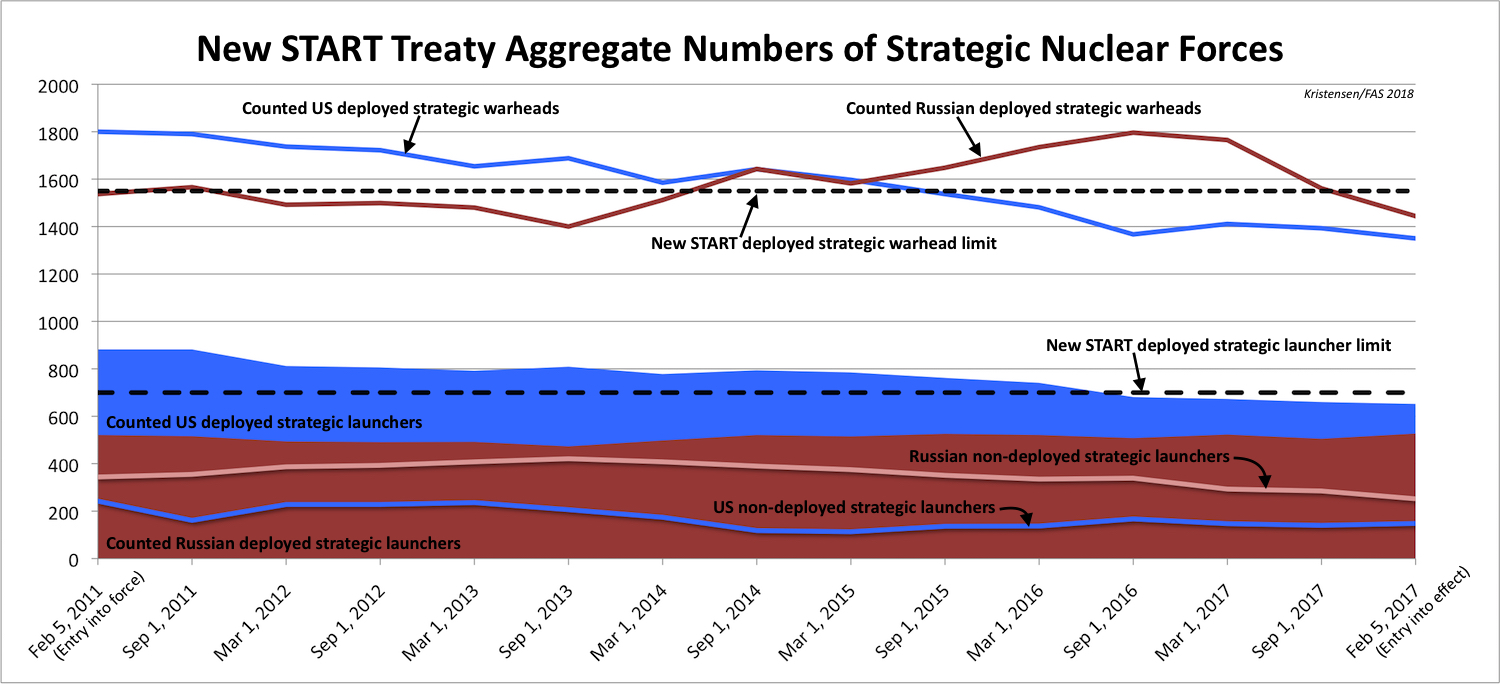

The latest New START treaty aggregate numbers published by the State Department earlier today show a slight increase in U.S. deployed strategic forces and a slight decrease in Russian deployed strategic forces over the past six months.

The data shows that the United States and Russia as of September 1, 2018 combined deployed a total of 1,176 strategic launchers with 2,818 attributed warheads. In addition, the two countries also had a total of 399 non-deployed launchers for a total of 1,576 strategic launchers.

Combined, the two countries have reduced their deployed strategic forces by 227 launchers and 519 warheads since 2011.

The warheads counted by the New START treaty are only a portion of the total warhead numbers possessed by the two countries. The Russian military stockpile includes an estimated 4,350 warheads while the United States has about 3,800.

The release of the data comes at a particular important time when the United States and Russia are considering whether to extend the New START treaty for another five years beyond 2021 when it expires. The treaty is under attack from defense hawks in Congress and the Trump administration is weighing whether to extend New START in light of Russia’s alleged violation of other agreements.

The data reaffirms that Russia, despite its modernization program, is not increasing its strategic nuclear forces but continue to limit them in compliance with the limitations of New START. In our latest Nuclear Notebook on Russia forces, we estimate that the New START limits recently caused Russia to reduce the number of warheads deployed on several of its strategic missiles.

Deployed Warheads

The data shows that the United States as of September 1 deployed 1,398 warheads on its strategic launchers. This is an increase of 48 warheads since February. Since 2011, the United States has offloaded 402 attributed warheads from its force.

The 1,398 is not the actual number of warheads deployed because bombers are artificially attributed one weapon each even though they don’t carry any weapons in peacetime. The actual number of deployed warheads is closer to 1,350.

Russia was counted with 1,420 deployed strategic warheads, a reduction of 24 warheads from February, and a total of 117 attributed warheads offloaded since 2011. Russian bombers also do not carry weapons so the Russian number is probably closer to 1,370 deployed strategic warheads.

These changes don’t reflect one country building up and the other reducing its forces, but are caused by fluctuations when launchers move in and out of maintenance or old launchers are retired or new ones added.

Deployed Launchers

The data shows the United States deployed 659 strategic launchers, an increase of 7 since February, and a total reduction of 223 launchers since 2011.

Russia deployed 517 strategic launchers, 142 fewer than the United States. That is 10 launchers less than in February, and a total reduction of 4 launchers since 2011.

Non-Deployed Launchers

The data also shows how many non-deployed launchers the two countries have. These are either empty launchers that are in reserve or overhaul or have not yet been destroyed.

The United States had 141 non-deployed launchers, which included empty ICBM silos, bombers in overhaul, and empty missile tubes on SSBNs in overhaul or refit. Since 2011, the United States has destroyed 101 non-deployed launchers.

Russia was counted with 258 non-deployed launchers. This includes empty ICBM silos, empty missile tubes on SSBNs in overhaul, and bombers in overhaul. Since 2011, Russia has destroyed 86 non-deployed launchers.

Essential Verification In Troubled Times

The treaty includes an important verification system that requires the United States and Russia to exchange vast amounts of data about the numbers and operations of their strategic forces and allows them to inspect each other’s facilities.

Since the treaty entered into effect in 2011, the two countries have exchanged 16,444 notifications about launcher movements and telemetry data; 1,603 since February this year.

Data released by the State Department shows that U.S. and Russian inspectors have conducted a total of 277 on-site inspections of each other’s strategic forces and facilities since the treaty entered into force in 2011. So far this year, U.S. officials have inspected Russian facilities 13 times compared with 12 Russian inspections of U.S. facilities.

The combined effects of limiting deployed strategic forces and the verification activities requiring professional collaboration between U.S. and Russian officials, mean that the New START treaty has become a beacon of light in the otherwise troubled relations between Russia and the United States, far more so than anyone could have predicted in 2010 when the treaty was signed.

Other background information:

- Russia nuclear forces, 2018

- US nuclear forces, 2018

- Status of world nuclear forces, 2018

- After Seven Years of Implementation, New START Treaty Enters Into Effect

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Russian ICBM Upgrade at Kozelsk

By Hans M. Kristensen

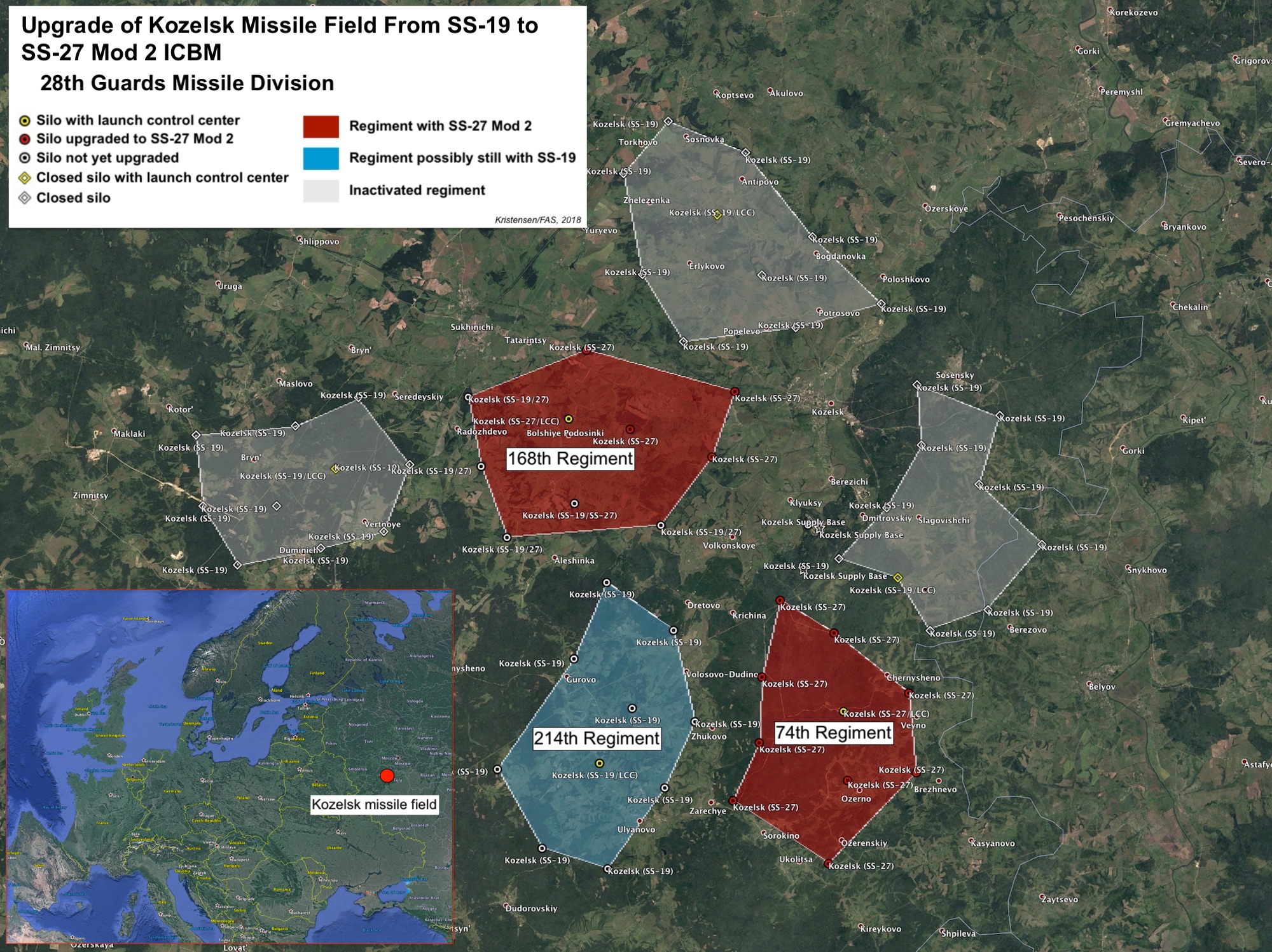

New satellite photos show substantial upgrades of ICBM silos at the missile field near Kozelsk in western Russia.

The images show that progress is well underway on at least half of the silos (possibly more) of the second regiment of the 28th Guards Missile Division from the Soviet-era SS-19 ICBM to the new SS-27 Mod (RS-24, Yars). The first regiment of ten silos completed its upgrade in late-2015. Like the SS-19, the SS-27 Mod 2 carries MIRV.

In its earlier configuration of six regiments with a total of 60 silos, the Kozelsk missile field covered an area of roughly 2,300 square-kilometers (890 square-miles). With closure of three regiments, the active field has been reduced to about 400 square-miles. That includes one 10-missile regiment (74th Regiment) that has already been upgraded to SS-27 Mod 2, a second that is being upgraded (168th Regiment), and a third (219th Regiment) that might still operate SS-19s, although the status is uncertain. It is possible that Russia will upgrade a total of 30 silos at Kozelsk. The Kozelsk missile field is located about 240 kilometers (150 miles) southwest of Moscow about 180 kilometers (115 miles) from Belarus (see image below).

Each SS-27 Mod 2 ICBM can carry up to four MIRV warheads, each with a yield of about 500 kilotons. Each SS-19 carried up to six MIRV, each with a yield of about 400 kilotons. The New START treaty apparently has forced Russia to reduce warhead loading on some of its missiles.

The latest image from Digital Globe on Google Earth is from June 22, 2018. It shows the large launch control center covering 335,000 square-meters (3,620,000 square-feet) with reconstruction nearly completed of the inner area with silo and underground command center. The administrational and technical area has been significantly expanded. A new gun turret is under construction and multi-layered security perimeter has been nearly completed around entire area (see image below).

Approximately 5 kilometers (2.8 miles) southeast of the launch control center, upgrade is underway on another of the 10 silos of the regiment. Comparison with an earlier photo from 2002 clearly shows the extensive upgrade, which is expanding the overall size of the facility to 136,000 square-meters (1,500,000 square-feet). Visible work includes a nearly finished silo, a new gun turret, trenches for new cables, and a new security perimeter (see image below).

Approximately 7 kilometers further southeast, another silo is being upgraded. This silo covers a slightly smaller are of 120,000 square-meters (1,300,000 square-meters). The upgrade appears to be less advanced with substantial work still going on in the silo, the gun turret not yet completed, no cable trenches visible yet, and the security perimeter only partially done. Visible in this area, however, is a unique entrance feature (see image below).

These are just a few facilities of Russia’s extensive land-based nuclear missile force, which has been under upgrade since the late-1990s. The upgrade of Russia’s four ICBM silo missile divisions and seven road-mobile ICBM divisions currently without just over 300 ICBMs is expected to be completed by the mid-2020s. Despite the modernization program, the U.S. Intelligence Community projects “the number of missiles in the Russian ICBM force will continue to decrease because of arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints,” according to the Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center.

For a breakdown of Russian nuclear forces, including locations of its entire land-based missile force, see the FAS Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

To compare Russia’s nuclear forces with those of the world’s other eight nuclear-armed states, go here.

This publication was made possible by generous grants from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, New Land Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Nuclear Notebook: Pakistani Nuclear Forces, 2018

A Babur-3 dual-capable SLCM is test-launched from an underwater platform in the Indian Ocean on January 9, 2017.

By Hans M. Kristensen, Robert S. Norris, and Julia Diamond

The latest FAS Nuclear Notebook has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: Pakistani nuclear forces, 2018 (direct link to PDF). We estimate that Pakistan by now has accumulated an arsenal of 140-150 nuclear warheads for delivery by short- and medium-range ballistic and cruise missiles and aircraft.

This is an increase of about ten warheads compared with our estimate from last year and continues the pace of the gradual increase of Pakistan’s arsenal we have seen for the past couple of decades. The arsenal is now significantly bigger than the 60-80 warheads the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency in 1999 initially estimated Pakistan might have by 2020. If the current trend continues, we estimate that the Pakistani nuclear warhead stockpile could potentially grow to 220-250 warheads by 2025.

The future development obviously depends on many factors, not least the Pakistani military believes the arsenal needs to continue to grow or level out at some point. Also important is how the Indian nuclear arsenal evolves.

The Pakistani government and officials initially described Pakistan’s posture as a “credible minimum deterrent” but with development of tactical nuclear weapons later began to characterize it as a “full spectrum deterrent.” Moreover, development is now underway to add a sea-based leg to its nuclear posture, and a flight test was conducted in 2017 of a ballistic missile that Pakistani officials said would be capable of carrying multiple warheads to overcome missile defense systems.

Additional information can be found here:

The Pentagon’s Annual Report on Chinese Military

[Updated August 21, 2018] The Pentagon’s annual report to Congress on China’s military and security developments has finally been published, several months later than previous volumes. Normally it takes about one month after the report is generated to be published. This year it took three times that long.

The report covers many aspects of Chinese military developments. In this article I’ll briefly review the nuclear weapons related aspects of the report.

Overall, nuclear developments are not what stand out in this report. Although there are important nuclear developments, the Pentagon’s primary concern is clearly about China’s conventional forces.

Nuclear Policy and Strategy

The DOD report repeats the conclusion from previous reports that China has not, despite writings by some PLA officers (and occasional speculations by outside analysts), changed its nuclear policy but retains a no-first-use (NFU) policy and a pledge not to use nuclear weapons against any non-nuclear weapon state or in nuclear-weapon-free zones. That would, strictly speaking, include Japan, even though it hosts large numbers of U.S. forces.

The NFU policy, DOD says, has “contributed to the construction of [underground facilities] for the country’s nuclear forces, which plan to survive an initial nuclear strike.” Stimulants for the tunneling efforts were the 1991 Gulf War and 1999 Kosovo war, which made the Chinese realize how vulnerable their forces would be in a war with the United States.

Nor does the report indicate China has yet mated nuclear warheads to its missiles or placed nuclear forces on alert under normal circumstances. The report repeats the assessment from last that “China is enhancing peacetime readiness levels for these nuclear forces to ensure responsiveness.” That responsiveness is thought to ensure the force can disperse and go on alert if necessary.

The report mentions unidentified PLA writings expressing the value of a “launch on warning” nuclear posture, but it does not say China has adopted such a posture. A launch on warning posture would require high readiness of nuclear forces to be able to launch as soon as a warning of an incoming nuclear attack was received. China already has a “ready the forces on warning” posture that involves gradually raising the readiness level in response to growing tension in a crisis.

In U.S. military terminology, “launch on warning” is a higher readiness level than “launch under attack” because it would involve being able to launch upon detection that an attack was imminent but before incoming missiles had been detected. “Launch under attack,” in contrast, would require the force to be able to launch before incoming warheads hit U.S. launchers. The DOD report says the PLA writings highlight the “launch on warning” posture would be consistent with China’s no-first-use policy, which would imply it is more compatible with a “launch under attack” posture.

The DOD report also continues to describe China’s work on MIRV, the capability to equip missile with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles. Rather than a sign of an emerging counterforce strategy, however, DOD states that the purpose of the Chinese MIRV program is to “ensure the viability of its strategic deterrent in the face of continued advances in U.S. and, to a lesser extent, Russian strategic ISR, precision strike, and missile defense capabilities.”

Indeed, the counterproductive effects of U.S. ballistic missile defenses on Chinese offensive force developments is clearly spelled out in the report: “The PLA is developing a range of technologies China perceives are necessary to counter U.S. and other countries’ ballistic missile defense systems, including MaRV, MIRVs, decoys, chaff, jamming, thermal shielding, and hypersonic glide vehicles.”

The growing inventory of ICBMs and SSBNs means that China has to improve nuclear command and control of these systems for them to be effective. It is unknown if Chinese SSBNs have yet sailed on a deterrent patrol (we assume not), much less with nuclear warheads onboard (we also assume not). But the growing and increasingly mobile ICBM force is carrying out extensive combat patrol exercises that place new demands on the nuclear command and control system.

A unique feature of the Chinese missile force is the mixing of nuclear and conventional versions of the same missiles (DF-21 and DF-26 have both nuclear and conventional roles). For China, this is a means to provide the leadership with non-nuclear strike options without having to resort to nuclear use. For China’s potential adversaries, it is a dangerous and destabilizing practice that risks causing confusion about the character of missile attacks and potentially trigger mistaken nuclear escalation in a conflict.

China has, like other nuclear-armed states, lowered the yield of its nuclear warheads as ballistic missiles became more accurate. The current warhead used on the DF-31/A ICBMs is thought to be ten times less powerful than the multi-megaton warhead developed for the DF-5. Moreover, as China seeks to ensure the survivability of its warheads against missile defense systems, it is likely to continue to try to reduce the weight and size of its warheads to maximize penetration aids on the missiles.

The DOD report mentions a “defense industry publication has also discussed the development of a new low-yield nuclear weapon,” but does not provide any details about the publication or what it said. The classified version apparently has more details.

The Land-Based Missile Force

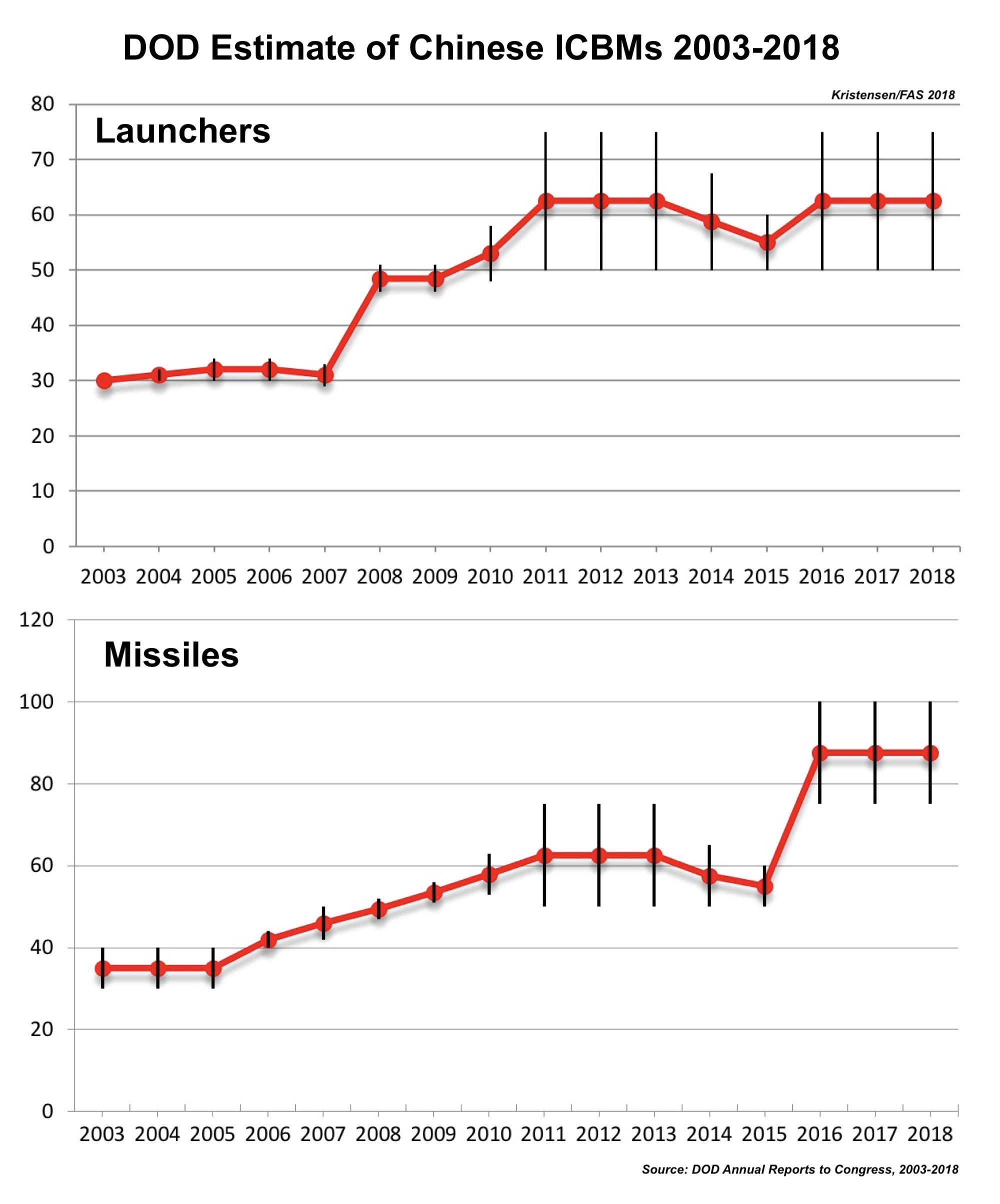

The overall number of Chinese ICBM launchers reported by DOD has remained stable since 2011: 50-75. One type (DF-4) has reload capability, so the number of available missiles is a little higher: 75-100 missiles. That number has also remained stable for the past three years. Indeed, other than the arrival of the DF-26 IRBM force, the total Chinese rocket forces estimate is identical to that of presented in the 2017 report.

This indicates that the DF-31A force is not continuing to increase, that the DF-31AG has not yet been operationally deployed (or is replacing older DF-31s on a one-for-one basis), and that the DF-41 is still in development more than 20 years after it was first listed in the annual DOD report.

DOD’s reporting shows that the number of Chinese ICBM launchers has roughly doubled since 2003, while the number of missile available for those launchers has more than doubled. The numbers of missiles show a mysterious increase in 2016 from just over 40 to more than 80 (see table below). The increase is curious because it does not follow the number of launchers but suddenly jumps even though there was no corresponding increase in launchers that year.

The DF-4 is thought to have reloads but that system has been deployed since the 1980s. There is considerable uncertainty in the number of launchers (some years 25). The increase coincides with the deployment of the MIRVed DF-5Bs, so a potential explanation might be that there are two full sets of DF-5 versions. But it should be underscored that it is unknown if this is the reason.

The old liquid-fuel DF-4 (CSS-3) ICBM is still listed as operational, even though the relocatable missile will probably be replaced by more survivable road-mobile missiles in the near future. The DF-4 appears to be retained in a roll-out-to-launch posture.

The old, but updated, liquid-fuel, silo-based DF-5 ICBM is still listed in two version: the single-warhead DF-5A and the MIRVed DF-5B. This missile was first deployed in the early-1980s and is based in 20 silos in the eastern part of central China. There is no mentioning of a rumored C version.

The DF-31 and DF-31A are the most modern operational ICBMs in the Chinese inventory. First fielded in 2006 and 2007, respectively, deployment of the DF-31 appears to have stalled and DF-31A is operational in perhaps three brigades. Each missile can carry a single warhead. The DF-31AG is mentioned for the first time as an enhanced DF-31 with improved launcher maneuverability and survivability but may not yet be fully operational.

The long-awaited DF-41 ICBM remains in development and is listed by DOD as MIRV-capable. The report states that China is “considering additional launch options” for the DF-41, including rail-mobile and silo-basing. In silo-based version it would likely replace the DF-5.

The medium- and intermediate-range nuclear missile force is made up of three types: the new DF-26 IRBM, which is dual-capable and able to conduct conventional (both land-attack and anti-ship) and nuclear precision attacks; and two versions of the DF-21: DF-21A and DF-21E. The DF-21 A (SSC-5 Mod 2) has been deployed since the late-1990s. The DF-21E (note: the E designation is not official but assumed) is known as the SSC-5 Mod 6 and was first reported in 2016. The DF-21 also exists in two conventional versions: DF-21C and DF-21D (anti-ship).

The dual-capable DF-26, first fielded in 2016, is capable of conducting “nuclear precision strikes against ground targets.” There appears to be one or two DF-26 brigades.

The role of the new Strategic Support Force is listed as intended to “centralize the military’s space, cyber, and EW [Early Warning] missions. These would probably support the rocket force.

The Submarine Force

The DOD report says that China still operates four Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs (all based at Hainan), each of which can carry up to 12 JL-2 SLBMs. At least one more Jin-SSBN is said to be under construction. Construction of a new SSBN (Type 096) may begin in the mid-2020s with a new SLBM (JL-3). DOD speculates that Type 094 and Type 096 SSBNs might end up operating concurrently, which, if accurate, could increase the size of the total SSBN fleet.

China also operates five Shang-class (Type 093/A) nuclear-powered attack submarines, with a sixth under construction. The Shang has now completely replaced the old Han-class (Type 092). DOD anticipates that a modified Shang (Type 093B) equipped with land-attack cruise missiles may begin building in the early-2020s. [Note: while many public sources call the two existing Shang versions Type 093A and Type 093B, the DOD report calls them Type 093 and Type 093A. The Type 093B is listed as a future type that until 2016 was called Type 095.]

Overall, China operates 56 submarines, of which 47 are diesel-electric. The report projects this force may increase to 69-78 submarines by 2020, a significant increase in only two years.

There is no mentioning in the DOD report of the nuclear sea-launched cruise missile listed in the Nuclear Posture Review fact sheet from February 2018.

The Bomber Force

One of the most interesting nuclear developments in the DOD report is the assessment that “the PLAAF has newly been re-assigned a nuclear mission.” This contrasts with last year’s report, which stated the “PLAAF does not currently have a nuclear mission.” The “re-assignment” indicates that the bombers previous had a nuclear mission. We have estimated that a small number of bombers had a dormant nuclear capability for gravity bombs as indicated by their extensive role in the nuclear weapons testing program and China’s display of nuclear bombs in military museums.

The DOD report states that the H-6 and the future stealth bomber could both be nuclear-capable. The future bomber, according to the DOD report, could potentially be operational within the next ten years.

The report repeats the estimate made by the U.S. Intelligence Community from the past two years that China is upgrading its aircraft with two new air-launched ballistic missiles, one of which may include a nuclear payload.

The DOD report does not mention the nuclear air-launched cruise missile listed the Nuclear Posture Review fact sheet from February 2018.

Additional Background:

Russia Upgrades Nuclear Weapons Storage Site In Kaliningrad

A buried nuclear weapons storage bunker in the Kaliningrad district has been under major renovation since mid-2016. Click on image to see full size.

By Hans M. Kristensen

During the past two years, the Russian military has carried out a major renovation of what appears to be an active nuclear weapons storage site in the Kaliningrad region, about 50 kilometers from the Polish border.

A Digital Globe satellite image purchased via Getty Images, and several other satellite images viewable on TerraServer, show one of three underground bunkers near Kulikovo being excavated in 2016, apparently renovated, and getting covered up again in 2018 presumably to return operational status soon.

The site was previously upgraded between 2002 and 2010 when the outer security perimeter was cleared. I described this development in my report on U.S. and Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons from 2012.

Between 2002 and 2010, the security perimeter around the Kulikovo nuclear weapons storage site were cleared and upgraded. Click on image to view full size.

The latest upgrade obviously raises questions about what the operational status of the site is. Does it now, has it in the past, or will it in the future store nuclear warheads for Russian dual-capable non-strategic weapon systems deployed in the region? If so, does this signal a new development in Russian nuclear weapons strategy in Kaliningrad, or is it a routine upgrade of an aging facility for an existing capability? The satellite images do not provide conclusive answers to these questions. The Russian government has on numerous occasions stated that all its non-strategic nuclear warheads are kept in “central” storage, a formulation normally thought to imply larger storage sites further inside Russia. So the Kulikovo site could potentially function as a forward storage site that would be supplied with warheads from central storage sites in a crisis.

The features of the site suggest it could potentially serve Russian Air Force or Navy dual-capable forces. But it could also be a joint site, potentially servicing nuclear warheads for both Air Force, Navy, Army, air-defense, and costal defense forces in the region. It is to my knowledge the only nuclear weapons storage site in the Kaliningrad region. Despite media headlines, the presence of nuclear-capable forces in that area is not new; Russia deployed dual-capable forces in Kaliningrad during the Cold War and has continued to do so after. But nearly all of those weapon systems have recently been, or are in the process of being modernized. The Kulikovo site site is located:

- About 8 kilometers (5 miles) miles from the Chkalovsk air base (54.7661°, 20.3985°), which has been undergoing major renovation since 2012 and hosts potentially dual-capable strike aircraft.

- About 27 kilometers (16 miles) from the coastal-defense site near Donskoye (54.9423°, 19.9722°), which recently switched from the SSC-1B Sepal to the P-800 Bastion coastal-defense system. The Bastion system uses the SS-N-26 (3M-55, Yakhont) missile, that U.S. Intelligence estimates is “nuclear possible.”

- About 35 kilometers (22 miles) from the Baltic Sea Fleet base at Baltiysk (54.6400°, 19.9175°), which includes nuclear-capable submarines, destroyers, frigates, and corvettes.

- About 96 kilometers (60 miles) from the 152nd Detachment Missile Brigade at Chernyakovsk (54.6380°, 21.8266°), which has recently been upgraded from the SS-21 SRBM to the SS-26 (Islander) SRBM. Unlike other SS-26 bases, however, Chernyakovsk has not (yet) been added a new missile storage facility.

- Near half a dozen S-300 and S-400 air-defense units deployed in the region. The 2018 NPR states that Russian’s air-defense forces are dual-capable. These sites are located 20 kilometers (13 miles) to 98 kilometers (60 miles) from the storage site.

So there are many potential clients for the Kulikovo nuclear weapons storage site. Similar upgrades have been made to other Russian nuclear weapons storage sites over the base decade, including for the Navy’s nuclear submarine base on the Kamchatka peninsula. There are also ongoing upgrades to other weapons storage sites in the Kaliningrad region, but they do not appear to be nuclear.

A Google street-view image from 2017 shows a military stop sign at the approach to the suspected nuclear weapons storage site north of Kaliningrad. Click image to view full size.

The issue of Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons has recently achieved new attention because of the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, which accused Russia of increasing the number and types of its non-strategic nuclear weapons. The Review stated Russia has “up to 2,000” non-strategic nuclear weapons, indirectly confirming FAS’ estimate.

NATO has for several years urged Russia to move its nuclear weapons further back from NATO borders. With Russia’s modernization of its conventional forces, there should be even less, not more, justification for upgrading nuclear facilities in Kaliningrad.

Additional Resources:

This publication was made possible by generous grants from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, New Land Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

US SSBN Patrols Steady, But Mysterious Reduction In Pacific In 2017

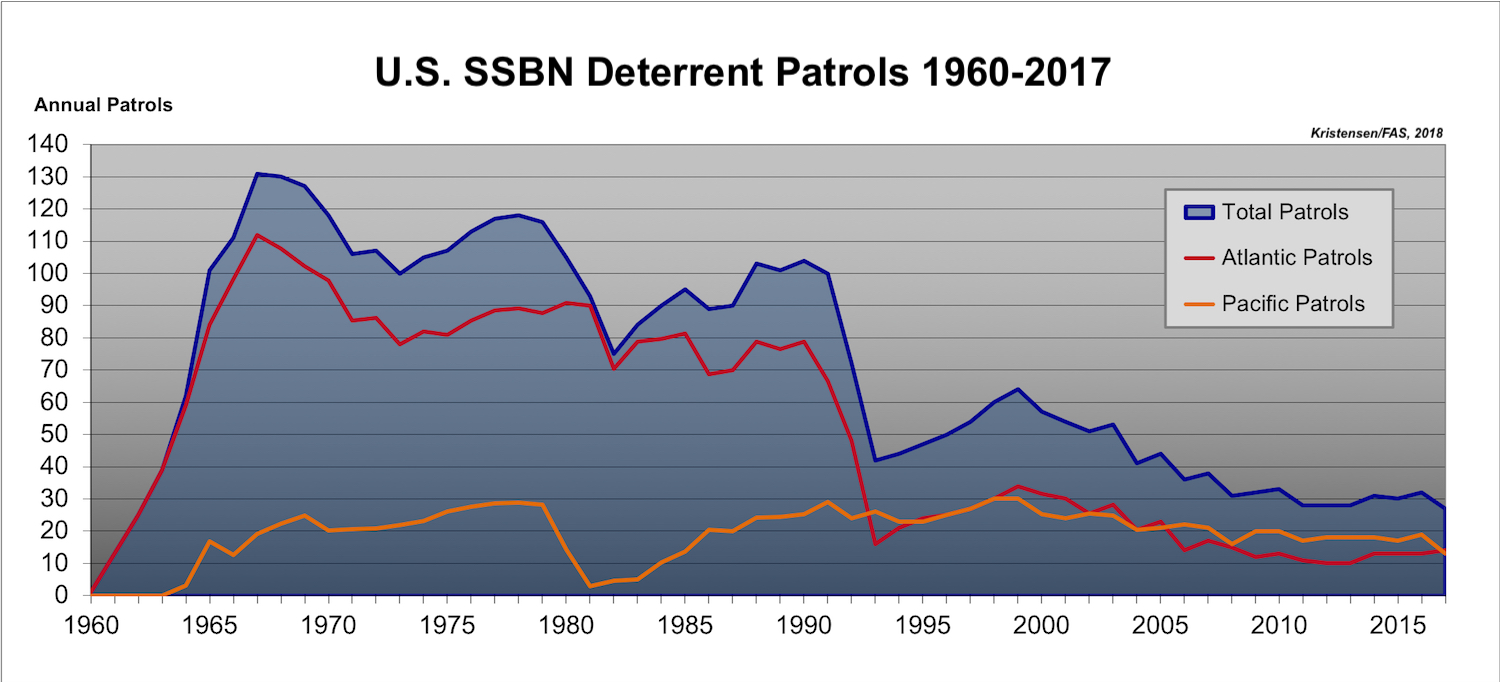

The U.S. SSBN fleet conducted 27 nuclear deterrent patrols in 2017, but with a mysterious reduction in the Pacific. Click graph to view full size.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Despite their age, U.S. nuclear ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) continue to carry out strategic deterrent patrols at a steady rate of around 30 patrols per year, according to data obtained from the U.S. Navy under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) by the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project.

Yet the data shows the U.S. SSBN fleet conducted a total of 27 patrols in 2017 (five less than in 2016), the lowest number of patrols in as single year since the early-1960s when SSBN deterrent patrols began. Even so, the fluctuations are small, modern SSBNs patrol longer than 1960s SSBNs, and the overall patrol number has remained relatively steady for the past decade.

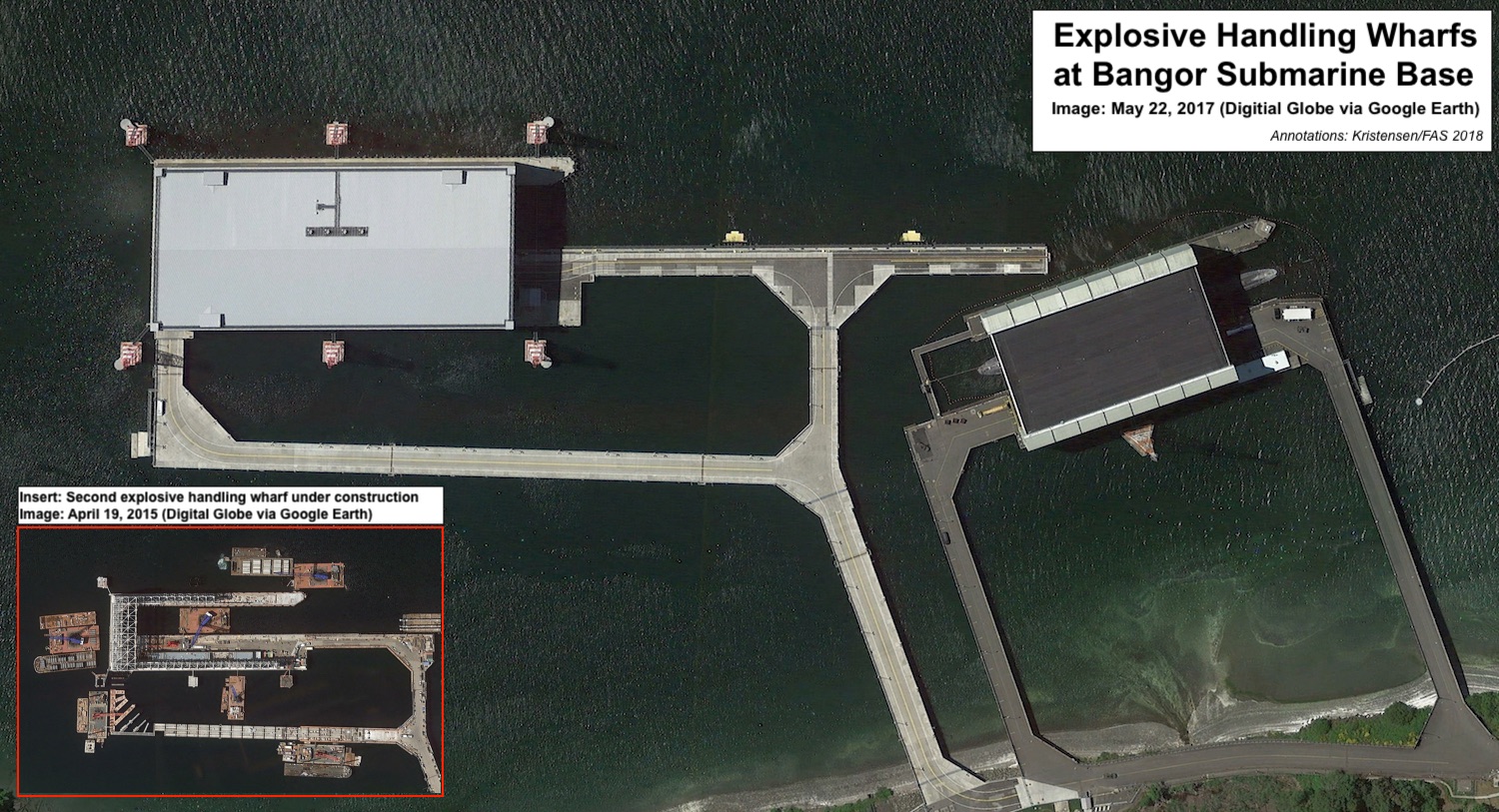

Nonetheless, the new data reveals a mysterious reduction of deterrent patrols in the Pacific in 2017: a nearly one-third drop from the 2016 level of 19 patrols to only 13 in 2017. The drop in Pacific patrols in 2017 happened despite completion of a second Explosive Handling Wharf at the Kitsap-Bangor Submarine Base that same year, which is intended to allow for additional maintenance needed as the submarines get older.

The drop in Pacific SSBN patrols happened despite completion of a second explosive handling wharf at Bangor. Click on image to view full size.

It is unknown what has caused the Pacific reduction. The size of the SSBN fleet at Kitsap-Bangor Submarine Base hasn’t changed, the Navy and U.S. Strategic Command haven’t announced a change in strategy, and there has been no public reports about serious technical problems that could have forced the reduction.

In any case, the SSBN fleet appears have picked up some patrol slack in early-2018. In mid-March this year, the Navy told Congress that SSBNs “conducted 33 strategic deterrent patrols…over the past year,” or five more than the 27 patrols the FOIA release says were conducted through 2017.

Coinciding with the reduction in Pacific patrols, the smaller Atlantic SSBN fleet (6 boats versus 8 in the Pacific) increased its patrols slightly in 2017 (from 13 to 14). As a result, the Atlantic SSBNs in 2017 conducted more deterrent patrols than the Pacific SSBN fleet for the first time since 2005 (14 patrol versus 13 patrols, respectively) when the majority of the SSBN force was shifted to operations in the Pacific.

Altogether, between 1960 and 2017, the US SSBN fleet conducted a total of 4,083 deterrent patrols, which adds up to an average of just over three patrols per submarine per year.

The Navy occasionally announces in public when SSBNs complete deterrent patrols, and less frequently when they begin a patrol. But it far from announces all of them. During the past decade, for example, only about one-third of the annual patrols were announced on average.

The duration of SSBN patrols can vary considerably. The Ohio-class SSBN is designed for 70-day patrols but individual patrols can be cut short by technical difficulties, in which case another submarine will have to take over the assignment. Similarly, sometimes a submarine approaching the end of its scheduled patrol will be forced stay out longer cause the submarine that was supposed to replace it delayed by technical problems. In 2014, for example, the USS Pennsylvania (SSBN-735) stayed out for 140 days – more than four-and-a-half months or twice its normal patrol duration – because of maintenance problems with its replacement submarine. The Navy said it was the longest patrol ever conducted by an Ohio-class SSBN. Again, toward the end of 2017, the USS Pennsylvania stayed on patrol for 116 days.

The USS Pennsylvania (SSBN-735) arrives at Kitsap-Bangor Submarine Base on June 14, 2014, after a 140-day deterrent patrol – the longest ever for an Ohio-class SSBN. Click image to view full size.

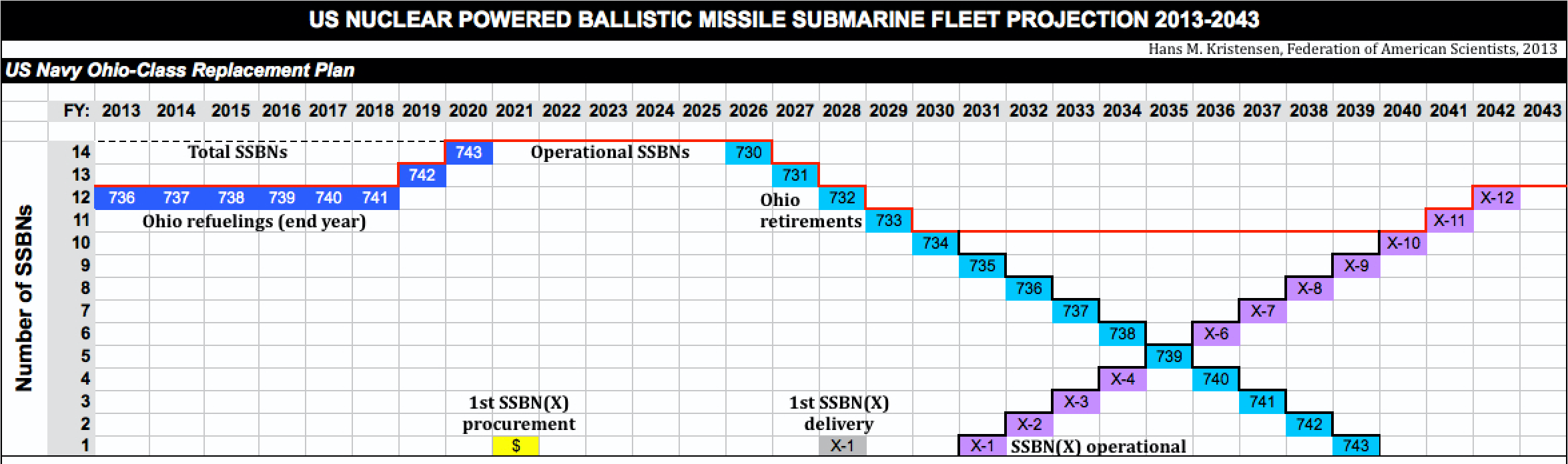

The USS Pennsylvania was commissioned in September 1989 – 29 years ago – and completed a mid-life complex reactor refueling overhaul in 2012. The boat is scheduled to be retired in 2031 at age 42, the year the first new Columbia-class (SSBN-826) will sail on its first deterrent patrol.

The 14 Ohio-class SSBNs will start retiring in 2027 and be replaced by 12 Columbia-class SSBNs from 2031. During much of the 2020s, the Navy will have more deployable SSBNs than it needs. Click graph to view full size.

Of the Navy’s 14 Ohio-class SSBNs, 12 are considered deployable (the 13th and 14th boats are in refueling overhaul). Of those, an average of 8-9 are normally at sea, of which 4-5 are thought to be on “hard alert” within range and position of their priority target strike package. The deployed SSBN force normally carries just over 200 SLBMs with around 900 warheads. Another 1,000 SLBM warheads are in storage for potential upload if necessary.

The last two SSBN reactor refueling overhauls will be completed in 2020-2021, after which the Navy will be operating 14 deployable SSBNs, or two more than it needs for deterrent operations. At that point, the two oldest SSBNs – USS Henry M. Jackson (SSBN-730) and USS Alabama (SSBN-731) – can probably be retired.

This publication was made possible by generous grants from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, and the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Weapons Maintenance as a Career Path

The US Air Force has published new guidance for training military and civilian personnel to maintain nuclear weapons as a career specialty.

See Nuclear Weapons Career Field Education and Training Plan, Department of the Air Force, April 1, 2018.

An Air Force nuclear weapons specialist “inspects, maintains, stores, handles, modifies, repairs, and accounts for nuclear weapons, weapon components, associated equipment, and specialized/general test and handling equipment.” He or she also “installs and removes nuclear warheads, bombs, missiles, and reentry vehicles.”

A successful Air Force career path in the nuclear weapons specialty proceeds from apprentice to journeyman to craftsman to superintendent.

“This plan will enable training today’s workforce for tomorrow’s jobs,” the document states, confidently assuming a future that resembles the present.

Meanwhile, however, the Air Force will also “support the negotiation of, implementation of, and compliance with, international arms control and nonproliferation agreements contemplated or entered into by the United States Government,” according to a newly updated directive.

See Air Force Policy Directive 16-6, International Arms Control and Nonproliferation Agreements and the DoD Foreign Clearance Program, 27 March 2018.

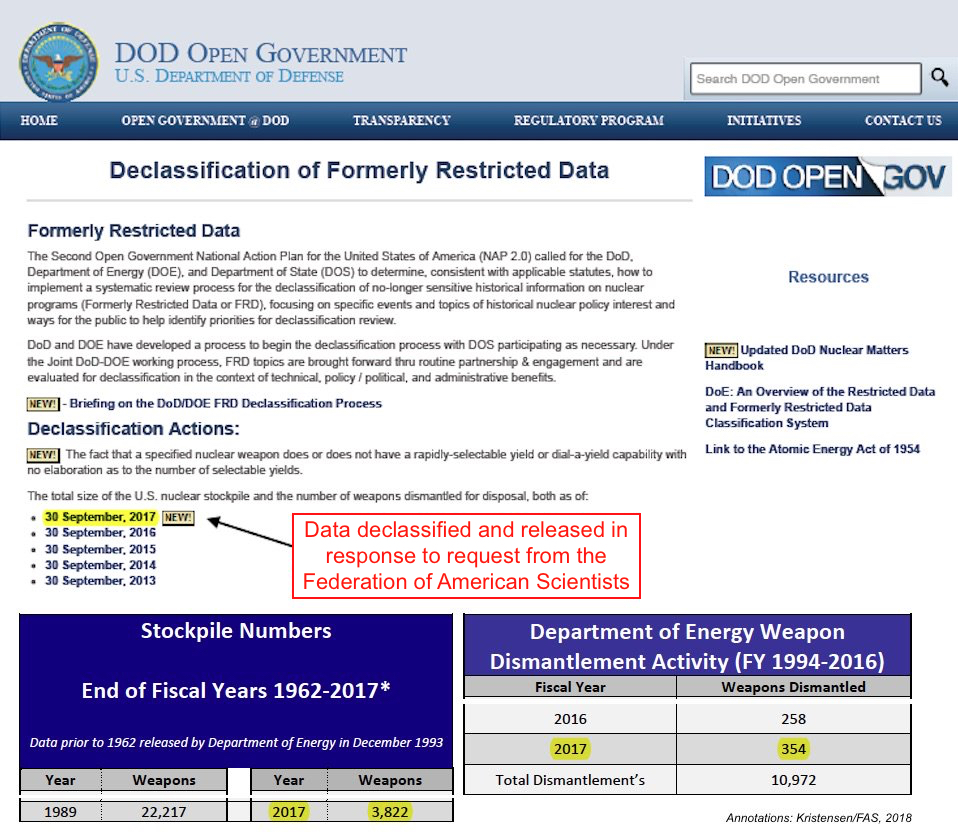

2017 Nuclear Stockpile Total Declassified

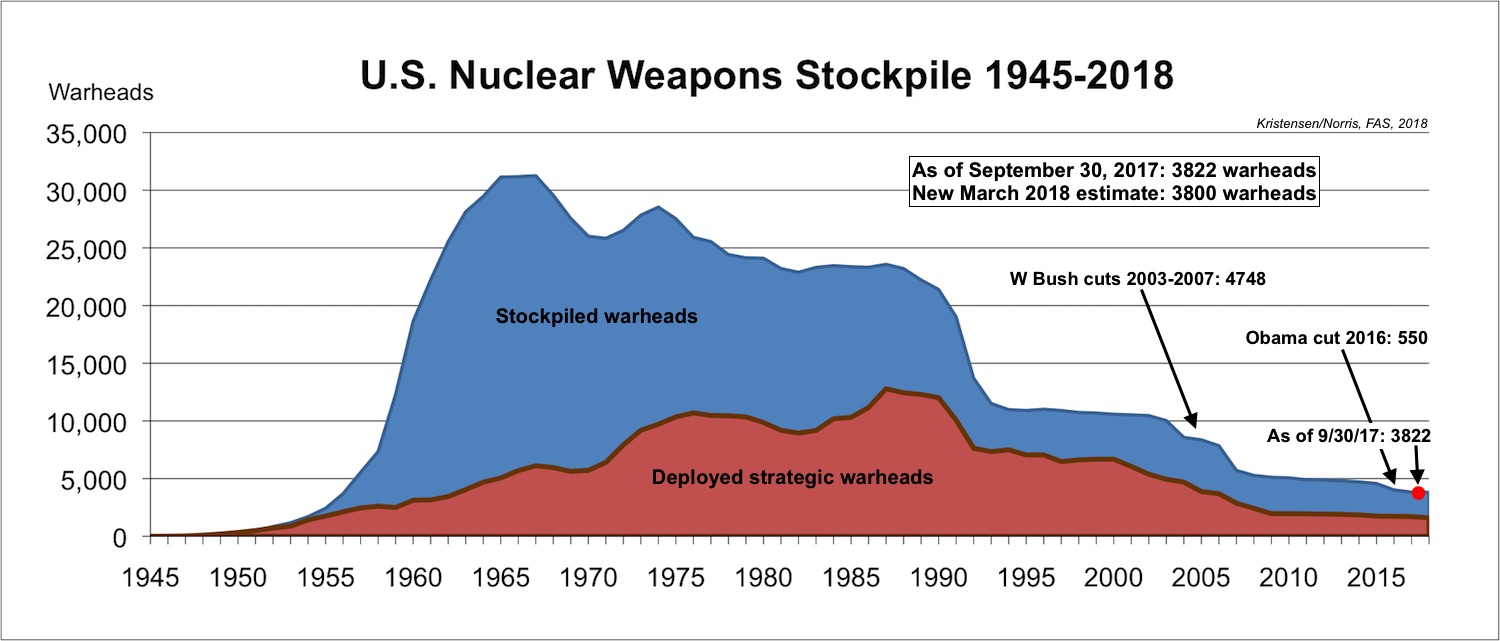

The number of nuclear weapons in the U.S. nuclear stockpile dropped to 3,822 as of September 30, 2017, down from 4,018 a year earlier. (Retired weapons awaiting dismantlement are not included in the totals.)The totals do not include weapons that are retired and awaiting dismantlement.)

Meanwhile, 354 nuclear weapons were dismantled in 2017, up from 258 the year before.

These figures were declassified in response to a request from the Federation of American Scientists and were made public yesterday.

The declassification of the current size of the US nuclear arsenal was a breakthrough in national security transparency that was accomplished for the first time by the Obama Administration in 2010.

It was uncertain until now whether or when the Trump Administration would follow suit.

Because the stockpile information qualifies as Formerly Restricted Data under the Atomic Energy Act, its declassification does not occur spontaneously or on a defined schedule. Disclosure requires coordination and approval by both the Department of Energy and the Department of Defense, and it often needs to be prompted by some external factor.

Last October, the Federation of American Scientists petitioned for declassification of the stockpile numbers, and the request was ultimately approved.

“Your request was the original driver for the declassification,” said Dr. Andrew Weston-Dawkes, the director of the DOE Office of Classification. “We regret the long time to complete the process but in the end the process does work.”

Earlier this week, FAS requested declassification of the current inventory of Highly Enriched Uranium, which has not been updated since 2013.

Despite Rhetoric, US Stockpile Continues to Decline

Click on image to view full size. Full document here.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The US nuclear weapons stockpile dropped to 3,822 warheads by September 2017 – down nearly 200 warheads from the last year of the Obama administration, according to new information released by the Department of Defense in response to a request from the Federation of American Scientists (see here for full document).

Since September 2017, the number has likely declined a little further to about 3,800 warheads as of March 2018. This is the lowest number of stockpiled warheads since 1957 (see graph), although the nuclear weapons and the conventional capabilities that make up today’s arsenal are vastly more capable than back then.

The new data also shows that the United States dismantled 354 warheads during the period October 2016 to September 2017 – the highest number of warheads dismantled in a single year since 2009. Since 1994, the United States has dismantled nearly 11,000 nuclear warheads.

The continued reductions are not the result of new arms control agreements or a change in defense planning, but reflects a longer trend of the Pentagon working to reduce excess numbers of warheads while upgrading the remaining weapons. This trend is as old as the Post Cold war era.

The majority of the warheads retired during the Trump administration’s first year probably included W76-0 warheads no longer needed as feedstock for the Navy’s W76-1 life-extension program.

The reduction has happened despite tensions with Russia, bombastic nuclear statements by President Donald Trump, and Nuclear Posture Review assertions about return of Great Power competition and need for new nuclear weapons.

The apparent disconnect between rhetoric and the stockpile trend illustrates that nuclear deterrence and national security are less about the size of the arsenal than what it, and the overall defense posture, can do and how it is postured.

Although defense hawks home and abroad will likely seize upon the reduction and argue that it undermines deterrence and reassurance, the reality is that it does not; the remaining arsenal is more than sufficient to meet the requirements for national security and international obligations. On the contrary, it is a reminder that there still is considerable excess capacity in the current nuclear arsenal beyond what is needed.

President Trump recently said he expected to meet Russian President Vladimir Putin “in the not-too-distant future to discuss the arms race,” which Trump added “is getting out of control…” He is right. In such discussions he should urge Russia to follow the U.S. example and also disclose the size of its nuclear warhead stockpile, agree to extend the New START treaty for five years, work out a roadmap to resolve INF Treaty compliance issues, and develop new agreements to regulate nuclear and advanced conventional forces.

There is much work to be done.

Additional information:

Declassified stockpile numbers.

Recent FAS Nuclear Notebook on US nuclear forces (written before the new stockpile information became available).

For an overview of all nuclear-armed states, see our Status of World Nuclear Forces.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

US Strategic Nuclear Forces, and More from CRS

The Congressional Research Service recently updated its report on US nuclear weapons and programs. See U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces: Background, Developments, and Issues by Amy F. Woolf, March 6, 2018.

That is also the subject of a new survey prepared by Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris of the Federation of American Scientists. See United States nuclear forces, 2018, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March 5, 2018.

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Joint Resolution Seeks to End U.S. Support for Saudi-led Coalition Military Operations in Yemen, CRS Insight, March 5, 2018

Iraq: In Brief, March 5, 2018

Tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean Focus on the Politics of Energy, CRS Insight, March 1, 2018

Qatar: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, updated March 1, 2018

Millennium Challenge Corporation, updated March 7, 2018

Material Support for Terrorism Is Not Always an “Act of International Terrorism,” Second Circuit Holds, CRS Legal Sidebar, March 5, 2018

So, Now Can Menachem Zivotofsky Get His Passport Reissued to Say “Israel”?, CRS Legal Sidebar, March 1, 2018

Responding to the Opioid Epidemic: Legal Developments and FDA’s Role, CRS Legal Sidebar, March 6, 2018

Banking Policy Issues in the 115th Congress, updated March 7, 2018

How Hard Should It Be To Bring a Class Action?, CRS Legal Sidebar, March 7, 2018

Nuclear Weapons Spending, Blockchain, & More from CRS

The Trump Administration requested $11.02 billion for maintenance and refurbishment of nuclear weapons in the coming year. This represents a 19% increase over the amount appropriated in FY2017.

Recent and proposed nuclear weapons-related spending is detailed by Amy F. Woolf of the Congressional Research Service in Energy and Water Development Appropriations: Nuclear Weapons Activities, February 27, 2018.

Another new CRS report discusses blockchain, the technology that underlies cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. Blockchain provides a way to securely record transactions of various types. “Despite public intrigue and excitement around the technology, questions still surround what it is, what it does, how it can be used, and its tradeoffs.”

“This report explains the technologies which underpin blockchain, how blockchain works, potential applications for blockchain, concerns with it, and potential considerations for Congress.” See Blockchain: Background and Policy Issues, February 28, 2018.

Other recent reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Defense Spending Under an Interim Continuing Resolution: In Brief, updated February 23, 2018

Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S. Response, updated February 27, 2018

U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel, updated February 26, 2018

Federal Civil Aviation Programs: In Brief, updated February 27, 2018

Health Care for Dependents and Survivors of Veterans, updated February 26, 2018

Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV): Background and Issues for Congress, updated February 27, 2018

The European Union: Questions and Answers, updated February 23, 2018

After Seven Years of Implementation, New START Treaty Enters Into Effect

Russia and the United States are currently in compliance with the treaty limits of the New START treaty. This table summarizes the evolution of the three weapons categories reported between 2011 and 2018. (Click on graph to view full size.)

By Hans M. Kristensen

[Note: On February 22nd, the US State Department published updated numbers instead of relying on September 2017 numbers. This blog and tables have been updated accordingly.]

Seven years after the New START treaty between Russia and the United States entered into force in 2011, the treaty entered into effect on February 5. The two countries declared they have met the limits for strategic nuclear forces.

At a time when relations between the two countries are at a post-Cold War low and defense hawks in both countries are screaming for new nuclear weapons and declaring arms control dead, the achievement couldn’t be more timely or important.

Achievements by the Numbers

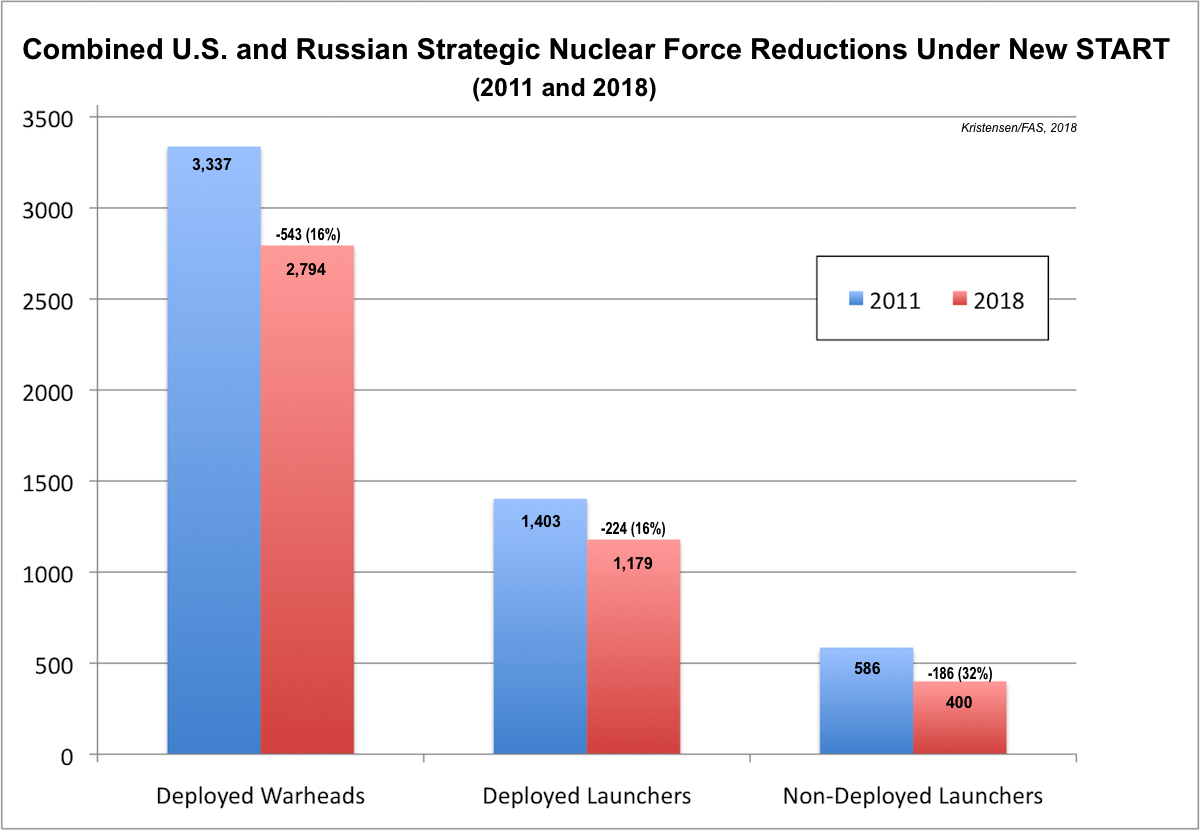

The declarations show that Russia and the United States currently deploy a combined total of 2,794 warheads on 1,179 deployed strategic launchers. An additional 400 non-deployed launchers are empty, in overhaul, or awaiting destruction.

Compare that with the same categories in 2011: 3,337 warheads on 1,403 deployed strategic launchers with an additional 586 non-deployed launchers.

In other words, since 2011, the two countries have reduced their combined strategic forces by: 543 deployed strategic warheads, 224 deployed strategic launchers, and 186 non-deployed strategic launchers. These are modest reductions of about 16 percent over seven years for deployed forces (see chart below).

The New START data shows the world’s two largest nuclear powers have reduced their deployed strategic force by about 15 percent over the past seven years. (Click on graph to view full size.)

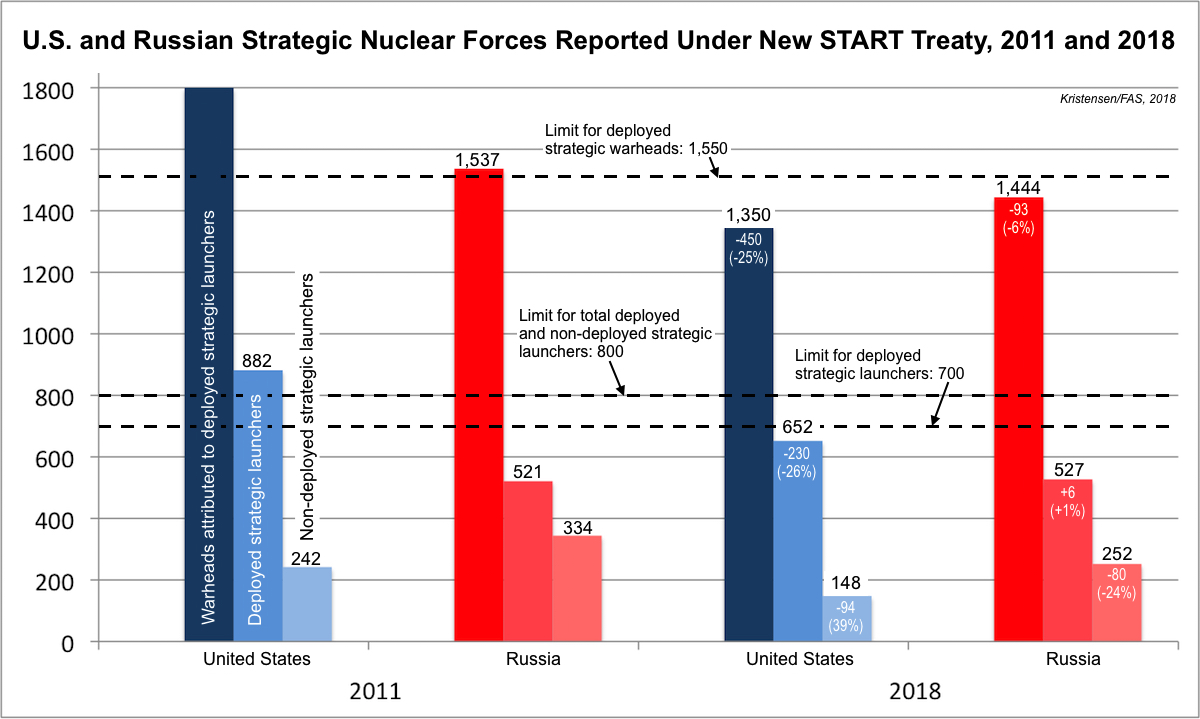

The Russian statement reports 1,444 warheads on 527 deployed strategic launchers with another 392 non-deployed launchers.

That means Russia since 2011 has reduced its deployed strategic warheads by 93, or only 6 percent. The number of deployed launchers has increased a little, by 6, while non-deployed launchers have declined by 80, or 24 percent (see chart below).

The Russian numbers hide an important new development: In order to meet the New START treaty limit, the warhead loading on some Russian strategic missiles has been reduced. The details of the download are not apparent from the limited data published by Russia. I am currently working on developing the estimate for how the download is distributed across the Russian strategic forces. The analysis will be published in a subsequent blog, as well in our next FAS Nuclear Notebook and in the 2018 SIPRI Yearbook.

The US statement lists 1,350 warheads on 652 deployed strategic launchers, and 148 non-deployed launchers.

That means the United States since 2011 has reduced its deployed strategic warheads by 450, or 25 percent. The number of deployed launchers has been reduced by 230, or 26 percent, while the number of non-deployed launchers had declined by 94, or 39 percent (see chart below).

US and Russian strategic force structures differ significantly. As a result, the reductions under New START have affected the two countries differently. Russia has significantly fewer launchers so rely on great warhead-loading to maintain rough overall parity. (Click on chart to view full size.)

In Context

The reason for the different reductions is, of course, that the United States in 2011 had significantly more warheads and launchers deployed than Russia. During the New START negotiations, the US military insisted on a higher launcher limit than proposed by Russia. So while Russia by the latest count has 94 deployed warheads more than the United States, the United States enjoys a sizable advantage of 125 deployed strategic launchers more than Russia. Those extra launchers have a significant warhead upload capacity, a potential treaty breakout capability that Russian officials often complain about.

So despite the importance of the New START treaty and its achievements, not least its important verification regime, the declared numbers are a reminder of how far the two nuclear superpowers still have to go to reduce their unnecessarily large nuclear forces. Ironically, because the US military insisted on a higher launcher limit, Russia could – if it decided to do so, although that seems unlikely – build up its strategic launchers to reduce the US advantage, and still be in compliance with the treaty limits. The United States, in contrast, is at full capacity.

But the apparent download of warheads on Russia’s strategic missiles demonstrates an important effect of New START: It actually keeps a lid on the strategic force levels.

Still, not to forget: The deployed strategic warhead numbers counted under New START represent only a portion of the total number of warheads the two countries have in the arsenals. We estimate that the deployed strategic warheads declared by the two countries represent on about one-third of the total number of warheads in their nuclear stockpiles (see here for details).

This all points to the importance of the two countries agreeing to extend the New START treaty for an additional five years before it expires in 2021. Neither can afford to abandon the only strategic limitations treaty and its verification regime. Failing this most basic responsibility would, especially in the current political climate, remove any caps on strategic nuclear forces and potentially open the door to a new nuclear arms race. The warning signs are all there: East and West are in an official adversarial relationship, increasing military posturing, modernizing and adding nuclear weapons to their arsenals, and adjusting their nuclear policies for a return to Great Power competition.

The symbolic importance of New START could not be greater!

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.