Figuring Out Fordow

Last week, my ace research assistant, Ivanka Bazashka, and I published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists an analysis of Iran’s recently revealed Fordow uranium enrichment facility, lying just north of Qom. In summary, we concluded that the timing of the construction and announcement of the facility did not prove an Iranian intention to deceive the agency but certainly raises many troubling questions. The facility is far too small for a commercial enrichment facility, raising additional serious concerns that it might be intended as a covert facility to produce highly enriched uranium (HEU) for weapons. But we also argued that the facility is actually too small to be of great use to a weapons program. A quite plausible explanation is that the facility was meant to be one of several covert enrichment facilities and simply the only one to be discovered. We believe, however, that it is significant that the Iranians assured the agency that they “did not have any other nuclear facilities that were currently under construction or in operation that had not yet been declared to the Agency” because any additional facilities uncovered in the future will be almost impossible to explain innocently. This, however, does not preclude Iran from making a decision to construct new enrichment facilities in the future.

Well, in just a few days, things have changed. We immediately got a lot of emails (some of them quite rude!) challenging our numbers. The Bulletin does not allow for lots of technical detail and we could not put our calculation in the article. So Ivanka and I have written an explanation of the derivation of our numbers. It is the first of a new format for the FAS website, FAS Issue Briefs. I expect that Hans, Matt, Nishal, and others will make good use of the format in the future. You can see our calculations in Calculating the Capacity of Fordow.

We show in our Issue Brief that the oft-cited performance of the Iranian centrifuge is based, at best, on hearsay, and, at worst, circular citations. Reporters get away all the time with citing “high level officials” and the like but analysts do not have that luxury. The reason that we are discussing the Iranian enrichment program is because of grave, immediate policy implications. This not just a question of when Iran might get the bomb, but should we take military action, should we go to war, and when. Ivanka and I conclude that the approach most often taken for estimating Iranian performance is unreliable and will almost certainly overestimate their capabilities. We demonstrate an alternative based on universally accepted, publicly available data.

In particular, we should be very wary of Iranian statements of their own capability. If I said that the National Ignition Facility at Livermore National Laboratory was going to achieve break even laser fusion within a year and cited an interview with the director of NIF, everyone would laugh at me. Statements by Iran about Iran’s capability should be taken with an equally large grain of salt. The Iranians brag about their technological virtuosity, specifically that, in spite of sanctions, they are still able to enrich uranium. It is obviously a matter of national pride. But do they explain to their taxpayers that they are spending billions of dollars to struggle to reproduce technology that the Europeans left behind as obsolete a half century ago and even that they do inefficiently? Our calculations, based on publicly available IAEA reports, shows that Iran is operating its centrifuges at 20-25% of what we might expect.

The second big change is Iran’s announcement of ten new future enrichment facilities. We argued in our Bulletin article that it was significant that Iran told the IAEA that there were no undeclared facilities waiting to be discovered. Ivanka was more skeptical, saying that this declaration meant little if the Iranians used their definition of when they were required to “declare.” I thought it more significant because any future discovery would be impossible to portray as innocent. On the other hand, we also said that the Fordow facililty did not make much sense except as part of a network of clandestine facilities. Well, the Iranians helped resolve that question when a few days later they announced that they were going to build ten new enrichment facilities, probably similar to Fordow. It is getting harder and harder to give Iran the benefit of the doubt.

Change at the United Nations

by: Alicia Godsberg

The First Committee of this year’s 64th United Nations General Assembly (GA) just wrapped up a month of meetings. The GA breaks up its work into six main committees, and the First Committee deals with disarmament and international security issues. During the month-long meetings, member states give general statements, debate on such issues as nuclear and conventional weapons, and submit draft resolutions that are then voted on at the end of the session. Comparing the statements and positions of the U.S. on certain votes from one year to the next can help gauge how an administration relates to the broader international community and multilateralism in general. Similarly, comparing how other member states talk about the U.S. and its policies can give insight into how likely states may be to support a given administration’s international priorities.

The Obama administration will certainly be looking in the near future for support on some of its new international priorities – the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference is happening in May, 2010 and the U.S. delegation will likely seek to promote certain non-proliferation measures, such as universal acceptance of the Additional Protocol and the creation of a nuclear fuel bank.[i] However, many states see these and other proposed non-proliferation measures as further restrictions on their NPT rights while the U.S. and the other NPT nuclear weapon states parties (NWS) continue to avoid adequate progress in implementing their nuclear disarmament obligation. At the same time, other states with nuclear weapons continue to develop them (and the fissile material needed for them) with no regulation at all. The United Nations (UN) is the court of world public opinion, a place where all member states have a voice. If President Obama expects to win support for his non-proliferation agenda next May, he needs to win the GA’s support by showing that the U.S. is ready to engage multilaterally again and take seriously its past commitments and the concerns of other states.

While the U.S. continued to vote “no” on certain nuclear disarmament resolutions[ii], there were some noteworthy changes in the position of the new U.S. administration during this year’s voting. One major shift away from the Bush administration’s voting through last year was a change to a “yes” vote on a resolution entitled, “Renewed determination towards the total elimination of nuclear weapons.” In fact, the U.S. also became a co-sponsor of this resolution. The change in the U.S. position on the CTBT was likely an important factor in this reversal, as the resolution “urges” states to ratify the Treaty, something Bush opposed but the Obama administration strongly supports. Similarly, the U.S. voted “yes” on the resolution entitled, “Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty,” and for the first time all five permanent members of the Security Council joined this resolution as co-sponsors.

The change in the U.S. position on the CTBT was welcomed by many delegations on the floor. Indonesia stated it would move to ratify the Treaty once the U.S. ratifies, and China has hinted at a similar position. Non-nuclear weapon states have found the past U.S. position – that no new states should have nuclear weapons programs while the U.S. continues its own without any legal restrictions on the right to test nuclear weapons – to be hypocritical. Add to this that the U.S. and other NWS have promised to work for the entry into force of the CTBT in the final documents of the 1995 and 2000 NPT Review Conferences, even using this promise as a way to get the indefinite extension of the NPT in 1995, and it may be that the CTBT is the sine qua non for the future of the NPT regime.

The U.S. delegation gave some strong signals that the Obama administration may be planning on decreasing the operational readiness of U.S. nuclear weapons (so-called “de-alerting”) in the upcoming Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). This speculation comes from remarks on the floor, when the sponsors of a resolution that had been tabled for the past two years entitled, “Decreasing the operational readiness of nuclear weapon systems” stated they would not be tabling the resolution this year.[iii] The sponsors stated that they would not be tabling the resolution because nuclear posture reviews were underway in a few countries and they hoped leaving the issue of operational readiness off the floor would, “facilitate inclusion of disarmament-compatible provisions in these upcoming reviews and help maintain a positive atmosphere for the NPT Review Conference.” Apparently the U.S. delegation pushed to leave this resolution off the floor, not wanting to vote against it again while the NPR was underway. Many took these political dealings as a sign that the Obama administration was pushing at home for a review of the operational readiness of the U.S. nuclear arsenal. Decreasing the operational readiness of U.S. nuclear forces would be a welcome change in the U.S. nuclear posture, adding time for decision-making and deliberation during a potential nuclear crisis. Such a change would also send an unambiguous signal to the international community that the U.S. was taking its nuclear disarmament obligation seriously, the perception of which is necessary for cooperation on non-proliferation goals in 2010 and beyond.

Another long-standing U.S. position apparently under review by the Obama administration relates to outer space activities. The Bush administration spoke of achieving “total space dominance” and the U.S. has been against the multilateral development of a legal regime on outer space security for 30 years. U.S. Ambassador to the CD Garold N. Larson spoke during the First Committee’s thematic debate on space issues, saying that the administration is now in the process of assessing U.S. space policy, programs, and options for international cooperation in space as part of a comprehensive review of space policy. The U.S. delegation changed its vote on the resolution, “Prevention of an arms race in outer space” from a “no” last year to an abstention this year, and did not participate in a vote on a resolution entitled, “Transparency and confidence-building measures in outer space” due to the current review of space policy. The U.S. message on outer space issues seemed to be that here too the new administration was looking to engage multilaterally instead of pursuing a unilateral agenda.

Under Secretary of State Ellen Tauscher mentioned another change in U.S. policy in her remarks to the First Committee – the support for the negotiation of an effectively verifiable fissile material cutoff treaty (FMCT)[iv]. Previously, the Bush administration had removed U.S. support for negotiating an FMCT with verification protocols, stating that such a Treaty would be impossible to verify. Without verification measures, which were part of the original Shannon Mandate[v] for the negotiation of an FMCT, many non-nuclear weapon states saw little value in negotiating the Treaty. Further, because verification was part of the original package for negotiation, the Bush administration’s change was seen as dismissive of the multilateral process and a further example of U.S. unilateral action without regard for the concerns of other countries or the value of multilateral processes. With the U.S. delegation stating that it supported negotiating an effectively verifiable FMCT as called for under the original mandate, the Obama administration again showed a marked change from its predecessor and a willingness to engage in multilateralism.

What does all this mean? President Obama stood before the world in Prague and pledged that the U.S. would work toward achieving a world free of nuclear weapons and has brought the issue of nuclear disarmament back to the forefront of international politics. President Obama recognizes that the U.S. cannot work toward this vision alone – we have security commitments to allies that need to be addressed as the U.S. makes changes to its strategic posture and policy, there are other nuclear armed countries that need to have the same goal and work toward it in a safe and verifiable manner, and there is the danger of nuclear terrorism and unsecured fissile material that needs to be addressed by the entire global community. In other words, the new administration recognizes the value in collective action to solve global problems, and at the 64th annual meeting of the UN General Assembly this year, the U.S. began putting some specific meaning behind President Obama’s general statements. With a pledge to work toward ratifying the CTBT at home and to work for other ratifications necessary for the Treaty’s entry into force, a renewed commitment to negotiating an effectively verifiable FMCT, and changes in long standing positions on outer space security and likely also on operational readiness of nuclear weapons, the Obama administration has shown the U.S. is back as a willing partner to the institutions of multilateral diplomacy. More than anything, this change – if it turns out to be genuine – will help advance President Obama’s non-proliferation goals at the upcoming NPT Review Conference. Of course the U.S. has internal battles to overcome, such as Senate ratification of the CTBT, but if promise and policy reviews are met with actions that can easily be interpreted by the rest of the world as genuine nuclear disarmament measures, President Obama has a greater chance to achieve an atmosphere of cooperation on U.S. non-proliferation goals at the upcoming NPT Review Conference in May, 2010.

[i] President Obama’s non-proliferation agenda was presented on May 5, 2009 to the United Nations by Rose Gottemoeller (Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Verification, Compliance, and Implementation) at the Third Session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2010 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference. http://www.state.gov/t/vci/rls/122672.htm

[ii] A few of the nuclear disarmament-related resolutions the US voted “no” on were: Towards a nuclear weapon free world: accelerating the implementation of nuclear disarmament commitments; Nuclear disarmament; and Follow-up to nuclear disarmament obligations agreed to at the 1995 and 200 Review Conferences of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

[iii] The US had voted “no” on this resolution the past two years, joined only by France and the UK.

[iv] Ellen Tauscher mentioned that the US “looks forward to the start of negotiations on a Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty” without further elaboration. President Obama, unlike President Bush, has made clear that his administration supports an effectively verifiable FMCT. For examples of this new policy direction, see: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/us-eu-joint-declaration-and-annexes; http://geneva.usmission.gov/2009/06/04/gottemoeller/; and http://www.state.gov/t/vci/rls/127958.htm

[v] Historical background on FMCT negotiations: http://www.reachingcriticalwill.org/legal/fmct.html

Waiting for Answers on Fordo: What IAEA Inspections Will Tell Us

by Ivanka Barzashka and Ivan Oelrich

After a cascade of disclosures and official announcements, followed by a great deal of conjecture from experts and the media, the Fordo enrichment plant, Iran’s newest enrichment facility located in the mountains near Qom, opened its doors on October 25 to International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspections. The US, France, and Britain accuse Iran of building the facility covertly and “challenging the basic compact at the center of the non-proliferation regime.” Iran claims the accusations are “hypothetical” and “fantasy” and are part of a conspiracy against Iran’s nuclear program. The Agency has an indispensable role of providing an objective technical account of the facility and ultimately determining whether Iran violated its Safeguards Agreement. But how much can we expect to learn from the first visit to the facility and would that provide sufficient information to resolve the accusations made against Iran?

The text under the Iranian flag with the atomic symbol says, “Nuclear power is our undeniable right.”

Location

With a brief letter to the IAEA on September 21, Iran formally announced the existence of the third enrichment plant new Qom, in addition to its commercial-scale Fuel Enrichment Plant (FEP) and the Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant (PFEP) at Natanz. It is not clear whether Iran provided the exact location of the new enrichment facility in the original letter to the IAEA. The White House said that the facility was located near Qom and was “very heavily protected, very heavily disguised,” but also did not disclose the exact location. The same day, Western media quoted Western diplomatic sources saying that the enrichment site was “on a mountain on a former Iranian Revolutionary Guards missile site to the north-east of Qom on the Qom-Aliabad highway”. This unleashed a frantic search by the expert community, which days later produced satellite images of potential sites. The best analysis came from Jane’s IHS, which placed the enrichment facility 20 miles (or about 32 km) northeast of Qom.

The head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization (AEOI), Ali Akbar Salehi, stated on October 26 that the enrichment plant was located 100 km from Tehran. Since Qom is by road 156 km southwest of Tehran, this places the location about 56 km north of the holy city, which is different from Jane’s location. Most likely, Salehi’s statement was only an approximation and is therefore consistent with Western accounts. The AEOI, however, did not release images of the facility.

However, a statement by the Office of Public Relations of AEOI, reprinted by Iranian news channel IRINN on October 28, requested that media refer to the nuclear site as Fordo, not Qom. Fordo, which means heaven (from the Farsi word “ferdos”), is a village 50 km south of Qom, but still in the province of Qom. According to the city’s official website, which is “subtly” adorned with an Iranian flag superimposed with a symbol of the atom, the enrichment site was located 160 km south of Tehran, placing it just south of Qom and north of Fordo.

The apparent contradiction was later resolved. The name of the facility was not due to geographic proximity, rather to appreciate the courage of the great number of casualties suffered by the town of Fordo during the Iran-Iraq war. Although, the website of Fordo (make sure your sound is turned off if you are in the office) may not be the most trustworthy source of information, the official name of Iran’s new enrichment plant is Fordo. This is what it will most probably be called in coming IAEA reports (perhaps, FFEP, or Fordo Fuel Enrichment Plant?), so use Fordo instead of Qom if you want to be up to date.

IAEA inspections will most definitely resolve the question of exact location, since inspectors have to physically get to the site. The exact coordinates will not become available, so Jane’s satellite imagery are and probably will be our best bet.

Timing

Timing is crucial in determining Iranian intention and whether the disclosure of the new facility met legal requirements. There are several important dates to watch out for – when a decision was made to construct the facility, when the construction actually began, when nuclear material was or will be introduced and when the facility was announced to the IAEA. The only date we know for certain is the last one – October 21.

The White House, learning that Iran had informed the IAEA of the Fordo plant on October 21, told other world leaders during the meetings at the UN in New York on October 23 The US and European nations presented a joint intelligence presentation to the IAEA on October 24, followed by more technical meetings on the 25th. On October 25, Obama, Sarkozy, and Brown made a public announcement about the facility during the G-20 meeting in Pittsburgh. The same day, Salehi announced the facility domestically.

According to Iran, there are no centrifuges installed at the Fordo enrichment plant and no nuclear material has entered the site. Salehi gives a time range from 1.5 to 2 years before the facility is operational, a year before the 6 months mandated by what Ahmadinejad claims is its legal obligations to the IAEA. According to US officials, the facility was most likely to be “at least a few months, perhaps more” from being operational. If the U.S. number is correct, then inspectors are likely to see centrifuges installed. At Natanz, it took about a year to install the first 18-cascades (about 3,000 centrifuges). Even if the Iranians have gotten more efficient and are able to install the machines in half the time, some machine installation would have already begun if operation is less than six months away. If that is the case, it is theoretically possible that nuclear material could have been introduced already. Instead of following normal practice and waiting until the entire facility had been completed, Iran started feeding each cascade at Natanz with UF6 as soon as it had been installed, possibly for political bragging rights and possibly because they were feeling their way forward with a new design. With their greater experience now, we cannot predict which path Iran will follow at Fordo.

The IAEA will do a base environmental sampling, which will show whether nuclear material has been introduced in the facility at some point in time. If the results are positive, then this will be an apparent breach of legal obligations and will open a whole can of worms, raising question where the material came from and bringing up bigger issues of material accountancy and intent.

When did construction of the facility start? US, French, and British intelligence agencies had been aware of the site for several years and claim that the construction began before March 2007, when Iran unilaterally withdrew from the modified Code 3.1 of the Subsidiary Arrangements to its Safeguards Agreement. Although we haven’t seen any Iranian official position on when construction started, the Fordo village website (the same one that claims that the enrichment plant is between Fordo and Qom and not between Qom and Tehran) states that construction began in 2006, which would mean that a political decision was made around the time that Iran decided to resume uranium enrichment, which was followed by UN Security Council resolutions condemning the decision. The IAEA may be able to confirm when the decision was made based on documents and interviews with Iranians involved in the project. In the past, Iran has been slow and reluctant to provide these, so it may be some time before the Agency reveals the truth.

Capacity, number and type of machines

To estimate what the Fordo facility was designed to do, we need to know its separative capacity or the number and type of machines that it will hold. The letter to the IAEA and the initial statements from Iranian officials said that those details would be revealed later. Salehi said that Iran hopes to employ a new type of machine, more advanced than the IR-1, which is currently operational at FEP in Natanz. Iran has been testing 4 types of machines (IR-2, IR-2m, IR-3 and IR-4) at PFEP for a while now, so it is foreseeable that one of the new models will soon be ready for industrial application.

According to the US, Iran was planning on installing 3,000 machines, which would have been enough IR-1s for about a bomb’s worth of HEU a year. In an earlier blog, we discussed how US intelligence could have known and what could be done with that many machines. Iranian media have referred to 3,000 machines but Foreign Minister Mottaki said in an NPR interview the plan was to have 7,000 machines.

Iran has probably by now submitted design information to the IAEA as requested. The report will include the intended capacity and throughput of the facility, as well as the expected concentrations of the waste and product. However, inspectors can visually verify the number of machines installed, if those are in place, and can see whether they are different from the machines at Natanz. Visual inspection will not give much information about the potential output of the machines, but that can be deduced based on future data on overall performance.

Legality

According to the US, the construction of the Fordo facility is in clear violation of Security Council resolutions and it has called on Iran to suspend all of its enrichment-related activities there. Iran does not accept these resolutions, claiming they are in contradiction to its right under the NPT to pursue nuclear technology for peaceful goals and also continues operating centrifuges at Natanz.

The US claims that Iran was obligated, under a revision of Code 3.1 of the Subsidiary Arrangements, which Iran agreed to in February 2003 (GOV/2003/40), to announce the facility to the IAEA as soon as a decision was made to begin construction. Iran counters that, in March 2007 it informed the IAEA that it had “suspended” the implementation of the revised Code 3.1 and would “revert” to the 1976 version, which only requires states to submit design information “no later than 180 days before the facility is scheduled to receive nuclear material for the first time” (GOV/2007/22). Salehi attributes this decision to “unfair entry of the U.N. Security Council into Iran’s nuclear dossier”. The IAEA finally concluded that, in accordance with Article 39 of Iran’s Safeguards Agreement, agreed Subsidiary Arrangements cannot be modified unilaterally (GOV/2007/22). The issue was brought up again in the latest IAEA report, noting that Iran had not yet provided design information for the Darkhovin nuclear plant (GOV/2009/55). El Baradei has stated explicitly that “Iran should have informed the IAEA the day they had decided to construct the [Fordo] facility.”

Moreover, the US insists that, in any case, construction started prior to the March 2007 when even Iran agrees it was subject to the Code 3.1 rules and failure to disclose the activity means that Iran was purposefully concealing the enrichment plant. It is possible that Iran would say that they were just digging a hole on the side of a mountain (there are many such installations in that area, as FAS has discovered) and the decision to use it as a centrifuge plant was made much later.

It seems that the Agency is already firm on the issue of legality. Inspections will do little to change that. What we should be expecting in the next report to the Board of Governors is a phrase that starts with “Iran has failed to provide design information”.

Purpose and Intent

According to Salehi, this installation is “semi-industrial,” although the letter to the IAEA described it as a “pilot plant.” Salehi explains that “in any technical issue we have pilot, semi-industrial, and then industrial steps. What we mean by semi-industrial in our nuclear program is that the number of centrifuges is not going to be more than a certain amount and a higher enrichment level is not important.” Later on, he specifies that the facility will enrich up to 5 percent.

Salehi further states that the facility has both passive and active defense – the former referring to its underground location covered by rock and the latter alluding to its proximity to a Revolutionary Guard base equipped with surface-to-air missiles. Persistent hints of Israeli attack, as well as Israel’s bombing of an alleged Syrian nuclear military facility in 2007 and an Iraqi nuclear reactor in 1981 provide grounds for Iranian worry. An interesting explanation is given by a website called the Iranian Revolution Document Center: by building fortified enrichment facilities, the value of an aerial attack against Natanz is greatly diminished since it will not stop Iranian enrichment. Thus, Fordo serves as a deterrent to an attack on Natanz.

The US has insisted, however, that the “size and configuration of the facility is inconsistent with a peaceful program” (for a more thorough analysis, see an earlier blog post). That the Fordo facility might provide a basis for a possible nuclear weapons breakout is an obvious concern, especially if suspicions persist that the Iranians had hoped and expected to keep the facility secret. The size of the facility is suspicious. Based on overhead photos and statements from the Iranians, the facility does not seem to be large enough to be economically viable as an enrichment facility for a commercial nuclear reactor. It might be sized appropriately, however, for a modest nuclear weapon production program. (A plant to power a large nuclear reactor has the capacity to produce about twenty nuclear weapons a year.)

The White House admits that its public announcement on October 25 was prompted by intelligence that Iran knew that the US knew of the facility. Had Iran not found out, the US and its allies would have waited until “actual construction caught up with intent,” although the White House claims that “certainly within the last few months, we think we’ve had a very strong basis on which to make our argument.” Based on this, we can conclude at the time of disclosure Fordo was close to, but not quite at, a stage where construction reveals intent.

It is unclear what intent the US had in mind, since the White House stated that “from the very beginning, [the US] had information indicating that the intent of this facility was as a covert centrifuge facility.” Intent could mean simply to enrich uranium covertly or to produce highly-enriched uranium. However, a covert centrifuge facility makes sense if the intention is to produce weapon-grade uranium. (Iran might also keep it secret to forestall preemptive attack.) But, if the US knew that Iran was planning on producing HEU prior to 2007 (the White House claims that construction started prior to Iran’s unilateral withdrawal from the revised Code 3.1 of the Subsidiary Arrangements), it raises the question why the 2007 National Intelligence Estimate concluded that Iran had halted its nuclear weapons program in 2003. (There are rumors that the intelligence community will be reconsidering its assessment.) So either the US wasn’t sure what Iran was constructing or the construction started after the NIE came out.

Conclusions

It is important to remember that this IAEA inspection is the first step in bringing Fordo under the safeguards, whose main goal is material accountancy or to ensure that no fissile material is diverted from a nuclear facility. Inspectors will probably do two technical assessments: verify the design information provided by Iran, upon the Agency’s request, and take base environmental samples to see whether nuclear material has been present. Cameras and seals will most likely not be introduced unless there is nuclear material in the vicinity, but key safeguards-relevant points in the facility will be considered based on design plans. The technical part is straightforward and provides important facts, but assessing the veracity of Iran’s statements and proving purpose and intent is hard. Inspectors will collect official documents and may conduct interviews with Iranian officials and scientists involved in the project to gather information on the decision-making, timing, support facilities (where parts are made, etc.) and the wider purpose of the facility in the context of Iran’s fuel cycle.

Inspections will be immediately effective in reconciling issues on the location of the plant (although concrete information will not be made public), enrichment capacity should be stated in the design information and type of machines could be assessed if installation has begun (which Iran is claiming has not). The specific purpose of the Fordo facility, which according to Iran is analogous to that of Natanz – to enrich uranium up to LEU levels for nuclear reactor fuel, is also stated in the documents. However, if Iran is actually uncertaint about the types of machines employed, the design information submitted is most likely preliminary or incomplete and will change. The Agency is firm in that the Islamic Republic should have declared the Fordo plant, as soon as a decision was made to construct it. However, based on past experience with Natanz, other questions, such as timing and purpose in the context of the entire fuel cycle, will be answered gradually as information is gathered by scientific methods, interviews, and collection of documents. This will be compared to information provided by other sources, such as foreign intelligence agencies.

The inspection may cast some light on Iran’s intentions by probing the consistency of its explanation of its overall program. Even if we accept Iran’s explanations entirely, the way the facility was announced shows that they are following only the strict letter of what they believe are their legal requirements. And there is a big gap between Iran and Vienna about what those obligations are.

The only way to prove ill intent may be to show that, even by Iran’s own standards, their story is inconsistent. That will be hard but the overall inspection exercise will provide some hints. Will the Iranians be prepared with what they consider to be all the required documentation? Or will there be long delays that suggest Iran is preparing documentation on the fly to retroactively explain what the inspectors are seeing on the ground? The state of development will give some idea of what the schedule might have been and whether the Iranians are meeting what they consider to be their six month warning time requirement. The Iranians can always drag out construction to meet their prediction of a year and a half to completion. But Natantz gives the world a rough guide to how long construction could have taken. Machines in place will strongly suggest a shorter schedule. The layout and planned number of machines will place some limits on what the capacity of the facility might be.

Once safegurards are in place, the nuclear weapon threat from Fordo will be no greater than from Natantz. The goals of the IAEA will remain the same: to give adequate warning if ever Iran begins to produce material that could be used for a weapon. As Iran’s total enrichment production increases, the relative accuracy of safeguard measurements has to increase to be sure of catching any given quantity of diverted material. If the Fordo facility eventually becomes a significant fraction of Iran’s total enrichment capacity, the stringency of IAEA accounting at Natantz may have to increase.

Of course, there is the question of whether Fordo is simply the only “secret” facility that we know about. The danger is that there are other facilities that can escape safeguards because the IAEA does not know about them. A clandestine enrichment facility would also require a clandestine conversion facility to produce UF6 feedstock because the output of the current facility at Esfahan is under IAEA inventory. We can never know exactly what we don’t know but there may be a silver lining to the cloud: Fordo might be another example of Iran trying, and failing, to keep a facility secret from Western intelligence, suggesting it is hard for Iran, or any other country ,to develop a clandestine capability. That may be too optimistic as a bottom line message, but the good news in this story is that the facility is now known and the IAEA kicked in exactly as it should.

We would like to thank our FAS intern, a native Farsi speaker who wished to remain nameless, for research support to this blog post. Please note that some of the articles referenced here are in Farsi, but can be easily translated using an online translator application.

CTBT Article XIV Conference

by: Alicia Godsberg

This past Thursday and Friday marked the 6th bi-annual Article XIV Conference, the Conference on Facilitating the Entry Into Force of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). This year’s conference was held at the United Nations in New York and was met with a measure of cautious optimism – most states voiced their appreciation of President Obama’s pledge to work toward US ratification of the CTBT, while many states recognized the challenges of obtaining all the necessary ratifications for entry into force of the Treaty and mentioned the challenges to the nonproliferation regime stemming from the lack of the Treaty’s entry into force (despite former commitments to do so) and from the DPRK’s 2006 and 2009 nuclear tests.

Entry into force of the CTBT has been on the international agenda for thirteen years. Because the US, China, UK, France, and Russian Federation have all imposed a voluntary moratorium on national nuclear testing, many question the need for entry into force of the CTBT. Although the Treaty would bring few new tangible benefits, the political impact of entry into force would be tremendous. As explained below, the vast majority of sates see entry into force of the CTBT as somewhat of a litmus test for the future viability of the nonproliferation regime.

The CTBT was opened up for signature in 1996 and since then the Treaty has obtained 181 signatories and 150 ratifications. In order for the Treaty to enter into force, 44 states mentioned in annex II of the Treaty must ratify. As of today, only 35 of these states have ratified the Treaty, leaving the full implementation of the Treaty in the hands of the remaining nine states.[i] The Treaty has an extensive verification system that is continuing to be built and includes 321 monitoring stations and 16 laboratories in 89 countries that make up an International Monitoring System (IMS). This system is now approximately 85% operational and since 2000 has been transmitting data to an International Data Center (IDC) to be interpreted and shared with all signatories to the Treaty. The IMS provides valuable data for civilian applications, such as advance tsunami warnings, but the main focus of the IMS is detection and attribution of nuclear test explosions. The system was proven effective even without the CTBT entering into force after collecting and interpreting data from both of the recent DPRK nuclear tests. However, the option of imposing intrusive on-site inspections is necessary for an extra layer of investigation into the attribution of nuclear explosions. According to the terms of the CTBT this option cannot be exercised before the Treaty enters into force, and is one main reason for the need to obtain the remaining nine “annex II” state ratifications.

Entry into force of the CTBT is also important, as many states reiterated at this latest conference, because the early entry into force of the CTBT was one of the conditions under which the non-nuclear weapon states parties (NNWS) to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) agreed to indefinitely extend the NPT in 1995. Similarly, at the 2000 NPT Review Conference, early entry into force of the CTBT was the first of 13 Practical Steps toward nuclear disarmament that was adopted by consensus by all states parties to the NPT that year. Nuclear weapon states parties to the NPT (NWS) have all signed the CTBT, but China and the US have not ratified the Treaty. President Obama has pledged to work toward US ratification, but it seems he is going to have to fight to get the 67 votes he needs in the Senate to do so. Indonesia, also an annex II state, recently publicly stated that once the US ratifies the CTBT they will follow with ratification, and it is likely that China will follow US ratification as well. Ratification of the CTBT by the last two NWS before the NPT Review Conference in May 2010 would be an important first step toward fulfilling NWS’s political commitments and legal obligations to NNWS. US and China’s ratifications of the CTBT could set the tone for cooperation on President Obama’s nonproliferation agenda and perhaps even on the sensitive topic of the control of the nuclear fuel cycle at the upcoming NPT Review Conference in May.

If you go here and read a random selection of statements from the Article XIV Conference, you will find that most states are looking to the US to fulfill its past promises and to take up the leadership position on nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament, about which President Obama speaks so eloquently. Yet, with all the positive reasons for states to ratify the CTBT, there still remain some important international and domestic stumbling blocks. Because countries like the DPRK and Iran are on the list of annex II states, many in the US and around the world believe that the Treaty will never enter into force. These voices in the US use such countries as one excuse not to support US ratification of the Treaty. While US ratification is not sufficient for the Treaty to enter into force it is necessary, and US ratification is likely to be followed by the ratification of at least some other annex II states as well. In addition, the international community would certainly see US ratification of the CTBT as a positive step toward a world free of nuclear weapons and toward fulfilling the nuclear disarmament obligation under Article VI of the NPT.

Policy makers in Washington don’t seem to make the connection between keeping political commitments/upholding international treaty obligations and getting support from the global community for US nonproliferation objectives. This point is never lost at the UN on the vast majority of states (meaning all but the five permanent members of the Security Council). In speech after speech, in forum after forum, NNWS – along with India, Pakistan, and Israel – call upon NWS to fulfill their obligations from the indefinite extension of the NPT in 1995 and from the 13 Practical Steps of the 2000 NPT Review Conference. President Obama recognizes the need for the international community to work together to manage our common security (see his speech to the GA here and to the Security Council here) and last week began reasserting US leadership at the UN in matters of nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation. To show the high-level of engagement that the US intends to have on the subject, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton led the US delegation to the Article XIV Conference (the first US delegation at an Article XIV Conference in ten years) and President Obama addressed the 64th General Assembly the day before the conference started and chaired the first ever Security Council Summit on nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation in a separate meeting on the conference’s first day. All this high-level attention from the US for the CTBT, nuclear disarmament, and nonproliferation was noted and welcomed by most of the states in attendance at the conference.

One thing that was not mentioned by any states in their official statements to the conference was the possibility of the provisional entry into force of the Treaty prior to obtaining all remaining annex II ratifications. Provisional entry into force of the CTBT could allow states parties to the Treaty to agree to on-site inspections when necessary, an important added layer to detect potential cheating. Provisional entry into force might also put pressure on those annex II states that have not yet ratified the Treaty to do so by being yet another indicator of the importance the vast majority of the international community places on the CTBT. Recognizing that international law helps solidify norms of state behavior and brings predictability and stability to international relations, many states at the conference spoke about the importance of codifying the voluntary nuclear testing moratoria the NWS have made into the CTBT, a legally binding treaty. Provisional entry into force of the Treaty before all annex II states have ratified could be an important step in the cementing of the norm against nuclear testing, thus providing another motivation for more annex II states to work toward ratification of the Treaty.

One other interesting note from the conference is that the actual measures to promote early entry into force of the CTBT – the main stated purpose of the conference – were not mentioned by many countries. Japan was one of only a few countries to discuss such measures in their speech, measures that included sending high-level envoys to annex II states to encourage their ratification of the Treaty at an early date. And while 103 states were represented at the conference, attendance during the bulk of state speeches was relatively low. This could be due to the fact that the General Assembly was simultaneously in session, and it should be noted that the large number of participants is indicative of the importance the international community places on the early entry into force of the CTBT.

The conference ended with the adoption of a final document but without much celebration. NNWS want serious progress to be made toward nuclear disarmament before NWS further restrict nuclear technology for peaceful purposes; the ratification of the CTBT by the two hold-out NWS is a promise that needs to be fulfilled for the vast majority of the world to recognize such serious progress. Despite the positive developments many states mentioned since the last Article XIV Conference in 2007, the CTBT is still not in force. US ratification of the CTBT might become the strongest signal of the revitalization of the nonproliferation regime, which will be tested for its durability at the upcoming NPT Review Conference in May 2010.

[i] The following is the list of annex II states that need to ratify the CTBT before it can enter into force: China; DPRK; Egypt; Indonesia; India; Islamic Republic of Iran; Israel; Pakistan; and the United States of America. Of these nine countries, three have not yet signed the Treaty (DPRK, India, and Pakistan).

Calculating Output of the New Iranian Uranium Enrichment Plant

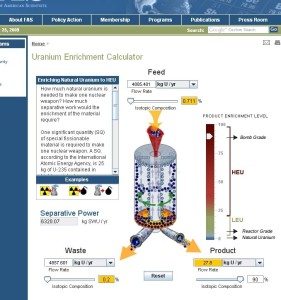

On Friday, President Obama announced that the United States knows of a new, undeclared, and hidden underground gas-centrifuge uranium enrichment facility in Iran, near the city of Qom. Some news reports suggest that 3000 centrifuges will be housed there. How significant is this discovery? Well, just in time, our crack FAS researcher, Ivanka Barzashka, has posted on the FAS website a calculator to help you answer questions just like that.

Natural uranium is made up predominantly of two isotopes, that is, atoms of the same element with the same chemical properties but very slightly different masses and, therefore, dramatically different nuclear properties. Uranium-235 is the isotope that powers nuclear reactors and nuclear bombs. Natural uranium is less than one percent 235 but approximately 90 percent U-235 is needed for a bomb. Getting these higher concentrations is called “enrichment”. Today gas centrifuges are the method of choice for enriching uranium. Hence the great concern about the latest revelation. [We have a nice little video that explains how centrifuges work.]

The calculator can be used to investigate possible Iranian breakout scenarios. In summary, the user has to supply the calculator with the concentration of uranium-235 in the input, or feed. Natural uranium is 0.7%. If the Iranians used the output of the enrichment plant at Natanz as input to the Qom plant, then they could start with 3.5%. The user must also specify the U-235 concentration in the waste. If Iran wants to get as much U-235 as possible out of its uranium supply, then this number will be small, usually 0.2-0.25%. If Iran is in a rush, it could feed uranium through faster but throw away more U-235. For example, if it used 3.5% as input, it could have “waste” of 1%, which is a higher U-235 concentration than natural uranium.

The calculator then returns the value of amounts of uranium and the “separative work” needed. Separative work is a general measure of the capacity of an enrichment element (such as a centrifuge or centrifuge plant) to enrich a certain amount of material over a given time. A plant operator can utilize any given plant capacity to enrich a large amount of uranium a little bit (as you would for a nuclear reactor) or to enrich a small amount of uranium a lot (as you would for a nuclear bomb). It is as though we had a pump of a certain power available and we could choose to pump a large volume of water a small distance uphill or a small quantity of water much further uphill. Separative work is measured in Separative Work Units or SWUs, performed on a certain amount of material, almost always kilograms, so the unit is kg-SWU.

How many SWUs would the enrichment plant at Qom have and what could the Iranians do with it? First, keep in mind that all information we currently have on the new facility is pretty vague and based on a few news reports. Iran has not officially declared the capacity of the Qom plant or what kind of machines it will contain. But it was reported to have 3000 centrifuges. Very simple calculations based on IAEA reports suggest that the first generation Iranian centrifuges produce approximately 0.5 kg-SWU/year so the plant would produce 1500 kg-SWU/year. Perhaps the second generation centrifuges would go in the new facility. We really know very little at all about these except that they are presumably better than the first generation. You can speculate on the separative work of these centrifuges and multiply by 3000.

Using some of the examples above, we can use the calculator to estimate the bomb-making potential of the new Iranian facility. For example, if we start with natural uranium and calculate how many SWUs are needed to produce on bomb’s worth of 90% U-235 (estimated to be 27.8 kg for the simplest bomb, significantly less for a more sophisticated bomb), we find that 6400 SWUs are required or over four year’s worth of production at 1500 SWU a year. If we start with 3.5% U-235 from the Natanz plant and have wastes of 1%, then we need 1328 SWUs, so a 1500 SWU plant could produce a bomb’s worth in a little less than a year. Of course, if the individual centrifuges are higher performance, these times are reduced proportionately. We don’t know enough about the new facility to say much more than that.

The calculator was developed by an interdisciplinary team with background including scientists and programmers. The calculator is geared toward people without a technical background. The programming was done predominantly by FAS intern Augustine Sebastionelli, a computer systems major at Alvernia University. The technical aspect of the project was managed by Greg Watson, IT manager at FAS and, when Greg left FAS to return to get his master’s degree in political science, finished by our new IT Manager, Robert Lilly. FAS intern Amit Talapatra, a chemical engineering major from the University of Virginia, worked with the programmers to develop an algorithm to perform the dynamic calculation. Overall coordination and concept design was Ivanka Barzashka’s.

Increased Safeguards at Natanz: What Does It All Mean?

by Ivanka Barzashka and Ivan Oelrich

A much anticipated IAEA report on Iran’s nuclear activities was leaked today. The report indicates that, among other things, Iran has conceded to additional safeguard at Natanz. This is a welcome development but occurring amidst a contested Iranian election, European threats of increased sanctions, continuing oblique hints of Israeli military action, and US talk of cutting off Iranian gasoline imports if nuclear talks are rejected. How important are these increased safeguards? Do they represent a change of course for Iran?

Current IAEA Safeguards in Iran

IAEA safeguards ensure that no country with a peaceful nuclear program will use that technology to develop a nuclear weapon. Specifically, safeguards provide credible assurances that fissile material is not being diverted from declared nuclear facilities. In accordance with Iran’s Safeguards Agreement, IAEA inspectors monitor any facilities that have nuclear material “of composition and purity suitable for fuel fabrication or for isotopic enrichment.” This includes the conversion plant in Esfahan, where yellow cake is converted to UF6, and the uranium enrichment facility in Natanz, where UF6 with natural concentrations is further enriched to concentrations suitable to fuel a commercial light water reactor. Uranium mines and ore processing facilities are not monitored. If Iran ratifies the Additional Protocol, then the IAEA will have access to all parts of the nuclear fuel cycle.

The safeguards objective is to ensure that, if a significant quantity (SQ) of material (that is, roughly enough to make a primitive bomb, in the case of highly enriched uranium, about 25 kg) is diverted, then the diversion will be detected within a certain time. In the case of Iran, the IAEA guarantees detection within one month of diversion of one SQ and a high probability that they can detect much smaller diversion.

Safeguards at enrichment plants are mostly based on material accountancy, which confirms that declared material in a facility is not secretly diverted. Safeguards start with an initial report by Iran of all nuclear material that is subject to safeguards, supplemented by design information of the facilities where this material is contained. This information is confirmed by the IAEA during design information verification (DIV). This information is used to identify general information about the facility (location, capacity, throughput) , as well as strategic points relevant to material accountancy (locations where key measurements are made and inventory locations).

The latest IAEA report (GOV/2009/55) states that Iran has not yet implemented early provisions of design information in accordance with the revised Code 3.1 of the Subsidiary Arrangements General Part, which would require Iran to notify the agency of the construction of new facilities or modifications to existing ones as soon as such a decision has been authorized by the government or the plant operator. The original agreement required Iran to submit such information no later than 180 days before the introduction of nuclear material into the facility (GOV/2003/40).

Based on these data, the IAEA and the Iranians then agree to the locations for containment and surveillance measures. Containment measures verify the physical integrity of an area or storage container. For example, this is done by placing seals on uranium cylinders under autoclaves. Surveillance cameras are placed at key locations to record activities at the facility ensuring that no unauthorized movement of nuclear material occurs. In addition, the cameras may confirm that, for example, the Iranians are making changes in the connections among centrifuges. Re-piping a cascade would be one of the ways to produce highly enriched uranium. The images from the cameras are periodically downloaded by IAEA inspectors. Camera cases are designed to reveal any attempt to tamper with them between inspections.

Iran submits reports to the Agency on uranium inventories and material flows. Inspectors verify this information during on-site inspections by comparing declared amounts to Iran’s daily operating records. Under the Safeguards Agreement, inspectors have the right to unannounced inspections. In Iran, 24 inspections are done per year, half of which are unannounced. Furthermore, inspectors perform physical inventory verification (PIV) once a year and have the option of interim inventory checks as well. A PIV is a kind of super inspection in which storage containers are weighed to determine actual quantities of uranium at each enrichment stage and samples are taken to confirm enrichment levels.

Increased Safeguards: Two Components

Beefing up safeguards at Natanz is not a sudden gesture of Iranian cooperation with the IAEA. The changes are not drastic and are consistent with the current Iran-IAEA Safeguards Agreement. Safeguard changes are in response to accounting problems and Agency requests already laid out in the last two IAEA reports issued in June and February this year.

Part of the enhanced safeguards will be improvements in Iran’s own inventory estimating. There was great brouhaha when the results of the November 2008 PIV were released in the Agency’s February 2009 report, revealing more uranium than the Iranians had declared. Several times in the press and elsewhere, this was described as the IAEA “discovering” Iranian uranium when, in fact, it simply revealed that Iran’s ability to estimate its own throughput was inadequate. FAS wrote a blog on this issue.

The changes are due, in part, to “the increasing number of cascades being installed at FEP” and “increased rate of production of LEU at the facility” (GOV/2009/35). The June report states that containment and surveillance measures need to be improved “in order for the agency to continue to fully meet its safeguards objectives.”

Improving Accounting

The IAEA has been insisting that Iran improve its own inventory control to make its declarations more credible. Between PIVs, IAEA inspectors base their reports on Iranian logbook data of how much material has been put through the machines and Iranian calculations of capacity. Iranian scientists do not have precise measurements of total production because some cylinders of UF6 are still connected to the cascade output, partially full, and cannot be weighed. Because filling a cylinder with enriched uranium takes a long time, Iranian engineers have developed an algorithm to estimate how much uranium has been enriched and is in each cylinder.

There have been two PIVs at Natanz – one in November 2008 and in December 2007. Iran started putting up machines in February 2007, so the first PIV reported only small amounts—75 kg—of product (GOV/2008/4). There were no reports of material enriched prior to the 2007 PIV. Therefore, the first real comparison between Iranian logbook data and IAEA physical inventory results was in February 2009, when the report with the 2008 PIV came out in public. It was clear that the algorithm estimating the amount of feed was very good, because logbook results matched IAEA’s findings. In the case of the product, this was not so. There was a 209 kg difference between Iranian logbook data and the results of the PIV, which amounted to about a third increase in product as declared previously.

Problems with Iran’s mass spectrometer – the device that measures the concentration of U-235 or the enrichment of the UF6, have also been reported. This would account for any differences between Iranian overall product enrichment measurements and what was recorded by the Agency.

An additional explanation cited in today’s report is the uncertainty in the amount of UF6 in cold traps. Cold traps are cryogenic traps that hold the output of the vacuum pumps, which are used to maintain the vacuum inside the centrifuge casing and collect small amounts of uranium gas leaked through the centrifuge rotor shaft. The amount of material contained in the cold traps is measured only by heating them up and cleaning them out so they are missed from day-to-day inventory control. The report states that a difference of 538 kg could result from “mainly a hold up in the various cold traps,” and that such a large amount of material is “not inconsistent with the design information provided by Iran” (GOV/2009/55).

Containment and Surveillance Changes

An increasing enrichment capacity requires additions to existing safeguards, according to the June IAEA report. The FEP design information shows that the plant is divided into two cascade halls: Cascade Hall A and B. Cascade Hall A has 8 units. As of the end of May 2009 one unit (A24) was completed. About a third of the total capacity of Unit A26 was operational, while another third had been installed, but operating under vacuum. In other words, as the number of centrifuges increases and the operating area of the plant increases, the IAEA needs more monitoring assets on the ground just to stay even. In addition, the IAEA is calling on Iran to address long-standing problems with their own inventory accounting.

Part of the enhanced IAEA monitoring capability may simply be more efficient use of current assets, such as surveillance cameras. Standard practice at other enrichment plants is to construct the entire enrichment plant and only upon completion begin feeding the machines with UF6. In contrast, Iran starts up each cascade of 164 coupled centrifuges as it is completed. Thus, at the Natanz facility, there is an ongoing process of installing new centrifuge cascades in the same hall where previously installed machines are already operating. Elsewhere, common practice is to have IAEA surveillance only in storage areas, keeping an eye on the seals on UF6 cylinders to make sure they are not tampered with. In Iran, this is more of a problem, since new centrifuges are continually coming on line. In theory, output of new cascades could be diverted. This is why Iran has agreed to put surveillance around the cascade area as well. For this to be affective, the cameras need to be able to have a clear view of the technicians to make sure that they are not removing nuclear material. This was less of a problem in the past since there were few cascades, but this is changing with the increase of plant throughput. As construction takes place at several units at once, inspectors have problems monitoring who is coming and going, especially since some new units may be out of view camera in their original positions.

Part of the enhanced IAEA monitoring capability may simply be more efficient use of current assets, such as surveillance cameras. Standard practice at other enrichment plants is to construct the entire enrichment plant and only upon completion begin feeding the machines with UF6. In contrast, Iran starts up each cascade of 164 coupled centrifuges as it is completed. Thus, at the Natanz facility, there is an ongoing process of installing new centrifuge cascades in the same hall where previously installed machines are already operating. Elsewhere, common practice is to have IAEA surveillance only in storage areas, keeping an eye on the seals on UF6 cylinders to make sure they are not tampered with. In Iran, this is more of a problem, since new centrifuges are continually coming on line. In theory, output of new cascades could be diverted. This is why Iran has agreed to put surveillance around the cascade area as well. For this to be affective, the cameras need to be able to have a clear view of the technicians to make sure that they are not removing nuclear material. This was less of a problem in the past since there were few cascades, but this is changing with the increase of plant throughput. As construction takes place at several units at once, inspectors have problems monitoring who is coming and going, especially since some new units may be out of view camera in their original positions.

A normal centrifuge plant requires very little personnel presence in the production areas. The numerous workers installing centrifuges adjacent to the production area complicates the IAEA monitoring. For example, Iranian attempts to change the piping on existing machines could be hidden within other, permissible, construction work. If the operating machines were isolated from the construction, even by a simple partition, the additional activity of reworking the piping would stand out more clearly. This would allow IAEA photo analysts to more effectively focus their efforts. Iran may also accept some work restrictions, such as leaving equipment in front of a surveillance camera for some agreed length of time to allow its identification before moving it to another part of the plant. Iran continues to resist remote monitoring so data from camera are downloaded when inspectors arrive on site and it analyzed later.

Political Implications

Some have suggested that Iranian compliance with IAEA requests is a sign that Teheran is preparing the ground for negotiations. Iranian officials themselves have stated that they are open to talks without preconditions and there was even a domestic proposal for an enrichment halt. The statement was quickly corrected making Iranian intentions as ambiguous as ever.

From a technical perspective, we believe that Iranian concessions on enhancing safeguards at Natanz do no present a fundamental change nor do they cause Iran much inconvenience. The changes are proportionate with the continued build up in the number of centrifuges and failure to implement them would have soon amounted to a violation of Iran’s Safeguards Agreement.

We should not read much political significance into Iran’s acceptance of additional safeguards. Whether Iran is cooperating with inspections because of, or in spite of, the threat of increased sanctions, their centrifuge program is continuing. Indeed, cooperation with the IAEA helps to weaken international political support for sanctions against Iran because of its nuclear program. We could say that Iran would rather have IAEA inspections than violate its Safeguards Agreement and suffer greater international sanctions, but we believe that agreeing to additional safeguards monitoring is not, by itself, an indication that Iran is willing to sit down at the negotiating table, let alone give up its centrifuge program.

The Big Picture – what is really at stake with the START follow-on Treaty

by Alicia Godsberg

There is cause for cautious optimism after Presidents Obama and Medvedev signed their START follow-on Joint Understanding in Moscow last Monday – the goal of completing a legally binding bilateral nuclear disarmament agreement with verification measures is preferable to letting START expire without an agreement or without one that keeps some sort of verification protocol. The Joint Understanding leaves some familiar questions open, such as the lack of definition of a “strategic offensive weapon” and what to do about the thousands of nuclear warheads in reserve or awaiting dismantlement. But so far few analysts on either side of the nuclear debate have been talking about the big picture, what for the vast majority of the world (and therefore our own national security) is really at stake here – the viability of the nonproliferation regime itself.

Why will the follow-on treaty to START have such a great impact on the entire nonproliferation regime? Simply, the rest of the world is looking for the possessors of 95% of the global nuclear weapon stockpiles to show greater effort in working toward their nuclear disarmament obligation under the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). The NPT is both a nonproliferation and disarmament treaty, and at the NPT Review Conferences (RC’s) and Preparatory Committees (PrepCom’s) the Non-Nuclear Weapons States Parties (NNWS) continue to voice their growing concern and anger over what they perceive to be lack of real progress on nuclear disarmament. At the PrepCom this past May those voices – including many of our closest allies – spoke loudly, stating that continued failure by the NWS to work in good faith toward their nuclear disarmament obligation could eventually break up the nonproliferation regime, spelling the end of the other part of the Treaty’s bargain: the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons.

Just to put things in perspective, NNWS are every country in the world except the five NWS (US, Russia, UK, France, and China) and the three countries that have never signed the NPT (Israel, India, and Pakistan – with a question now about the obligations of North Korea and without including Taiwan, which is not recognized by the United Nations). While the NPT has an elaborate mechanism to verify the compliance of NNWS with their nonproliferation obligations under the Treaty (i.e. the IAEA and its Safeguards Agreements), there are no institutionalized means to monitor or enforce compliance with the disarmament obligation of NWS under Article VI of the Treaty. And while some NWS are now proposing further restrictions on NNWS nuclear energy programs through preventing the spread of sensitive fuel-cycle technology, NNWS are increasingly voicing their frustration over nuclear trade restrictions while greater progress on nuclear disarmament remains in some distant future. Further fueling this distrust of the NWS and of new technology transfer restrictions was the Bush administration’s ill-advised US-India nuclear cooperation deal, seen by many NNWS as “rewarding” India with an exception to nuclear trade laws and export controls while India continues to operate its nuclear programs largely outside the NPT’s nonproliferation regime and its oversight and restrictions.

This blog is not meant to weigh in on the controversy surrounding the inalienable right of NNWS to nuclear technology under Article IV of the NPT, but rather to state the fact that a series of what are perceived as broken promises by NWS to NNWS has led the regime to approach what many have seen as a breaking point. Some of those promises include the ratification of the CTBT, strengthening of the ABM Treaty, and the establishment of a Nuclear Weapon Free Zone in the Middle East. These promises have special significance, as they were part of political commitments made to get the indefinite extension of the NPT in 1995, thereby removing any small pressure NNWS might have been able to place on NWS to meet their disarmament obligation by threatening not to renew the Treaty at future RC’s.

The US has a special role to play in this drama for two reasons. First, the US is the second largest possessor of nuclear weapons in the world and as such needs to be at the forefront of nuclear disarmament for that goal to be taken seriously and eventually come to fruition. Second, President Obama has publicly reversed some positions of President George W. Bush on nuclear disarmament and the world is waiting to see if his vision will be translated into action by the US. For example, at the 2005 NPT RC the Bush administration stated it would not consider as binding any of the commitments made by prior US administrations at previous RC’s, such as the commitment to the “unequivocal undertaking” to eliminate nuclear weapons and the commitment to work toward ratifying the CTBT. Contrast that with Obama’s policy speeches, especially the one in Prague on April 5, 20009 in which he placed a high priority on US verification of the CTBT and on his vision of a world free of nuclear weapons, and you can begin to understand the feeling of hope surrounded by a continued atmosphere of mistrust that pervaded the United Nations in May.

A recent New York Times op-ed[i] pointed out that there is no guarantee the US Senate is going to go along with President Obama’s nuclear policy vision, and he may in fact encounter difficulty ratifying the CTBT and gaining support for the reductions outlined in last week’s Joint Statement. In a June 30 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal,[ii] Senator Kyl and Richard Perle voiced this side of the debate, stating:

There is a fashionable notion that if only we and the Russians reduced our nuclear forces, other nations would reduce their existing arsenals or abandon plans to acquire nuclear weapons altogether… this is dangerous, wishful thinking. If we were to approach zero nuclear weapons today, others would almost certainly try even harder to catapult to superpower status by acquiring a bomb or two. A robust American nuclear force is an essential discouragement to nuclear proliferators; a weak or uncertain force just the opposite.

This fear mongering, unsupported by the facts, is the type of rhetoric that will confuse the debate once any START or CTBT-related issues hit the Senate floor. In a world where reductions would still leave actively deployed nuclear warheads in the thousands – with thousands more on reserve – “superpower status” will not be achieved by acquiring “a bomb or two.” Think about North Korea – are they a “superpower” now that they have exploded two nuclear devices and we know they are continuing to work on their nuclear weapon program? Hardly. Instead, they are international outcasts, condemned even by China for their latest atomic experiment, and have become weaker still in their attempt to achieve international status. And if the US, the country with the most powerful and advanced conventional forces, needs a “robust” nuclear force to protect its national security and fulfill security commitments, then it seems that any country with a weaker conventional force (which is everyone else) should seek nuclear weapons. So, I would argue exactly the opposite Senator Kyl and Mr. Perle, and say that a diminishing role for nuclear weapons in US security actually lessens the case for other nations to develop their own nuclear weapons, which are more costly both economically and politically than conventional forces.

Whether the US can restore the faith of the rest of the world in our leadership on nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament by meeting previous political commitments and working toward fulfilling Treaty obligations remains to be seen. Rose Gottemoeller’s remarks to the 2009 NPT PrepCom at the UN in May were well received by the global community, but NNWS also made clear that words need to be followed by concrete actions. The US needs the cooperation of the global community to continue the success of the nonproliferation regime, which has been largely successful over the past 39 years minus the few notable failures. To do this, the US must understand that the follow-on treaty to START will directly impact the perception the rest of our global community has about the seriousness of our commitment to the NPT. That is because the NPT is both a disarmament and nonproliferation treaty; if the US recognizes and acts on this truth, it will be able to achieve the urgent goal of regaining its leadership position on the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons.

[i] Taubman, Philip. “Obama’s Big Missile Test.” Editorial. New York Times 8 July 2009.

[ii] Jon Kyl and Richard Perle. “Our Decaying Nuclear Deterrent.” Editorial. Wall Street Journal 30 June 2009.

North Korea’s Nuclear Test: Another Fizzle?

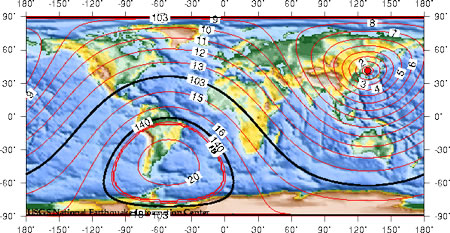

|

| The North Korean nuclear test on May 25, 2009, was “heard” loud and clear around the world despite its apparent limited size. Detection of small, clandestine nuclear tests seems to work. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Korean Central News Agency reportedly has announced that North Korea “successfully conducted one more underground nuclear test on May 25 as part of measures to bolster its nuclear deterrent for self-defense.” Several news media reported that the Russian Ministry of Defense estimating the test had a yield of approximately 10 to 20 kilotons.

Yet the preliminary seismic data published by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) shows that the test had a seismic magnitude of 4.7, only slightly more powerful than the 4.3 of the 2006 test.

Was it another fizzle? We’ll have to wait for more analysis of the seismic data, but so far the early news media reports about a “Hiroshima-size” nuclear explosion seem to be overblown.

Update: CTBTO’s initial findings.

.

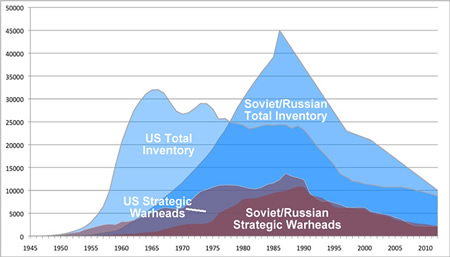

Briefing on US-Russian Nuclear Forces

|

| Vast inventories of nuclear weapons remain after the Cold War arms race ended. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russia’s nuclear forces are expected to drop well below 500 offensive strategic delivery vehicles within the next five years, less than one-third of what’s permitted by the 1991 START treaty. Unless the next U.S. Nuclear Posture Review significantly reduces the number of land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, that single leg of the U.S. Triad of nuclear forces alone could soon include more delivery vehicles than the entire Russian strategic arsenal of land- and sea-based ballistic missiles and long-range bombers. With this in mind, Russia is MIRVing its ballistic missile to keep some level of parity with the United States.

This and more from a briefing I gave this morning at the Arms Control Association meeting Next Steps in U.S.-Russian Nuclear Arms Reductions. I was in good company with Ambassador Linton Brooks, the former U.S. chief negotiator on the START treaty, who spoke about the key issues and challenges the START follow-on negotiators will face, and Greg Thielmann, formerly senior professional staffer of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, who discussed how the a new agreement might be verified through START-style verification tools.

Download: Briefing on US-Russian Nuclear Forces

.

Iran’s Fuel Fabrication: Step closer to energy independence or a bomb?

By Ivanka Barzashka and Ivan Oelrich

Yesterday, on Iran’s national Nuclear Technology Day, President Ahmadinejad announced the country’s latest nuclear advances, which seem to have become an important source of national pride and international  rancor. April 9 marks the day when Iran claimed to have enriched its first batch of uranium in 2006. Yesterday, Ahmadinejad inaugurated Iran’s Fuel Manufacturing Plant (FMP) at Isfahan and announced the installation of a new “more accurate” type of centrifuge at the Fuel Enrichment Plant (FEP) at Natanz.

rancor. April 9 marks the day when Iran claimed to have enriched its first batch of uranium in 2006. Yesterday, Ahmadinejad inaugurated Iran’s Fuel Manufacturing Plant (FMP) at Isfahan and announced the installation of a new “more accurate” type of centrifuge at the Fuel Enrichment Plant (FEP) at Natanz.

A fuel fabrication facility, the last element of the front-end fuel cycle, is where nuclear reactor fuel is made. For light water reactors (LWR), such as the one in Bushehr, uranium is mined, turned into yellow cake, and converted to uranium hexafluoride (UF6), the UF6 is enriched using centrifuges, converted into uranium oxide pellets, and made into fuel rods, which go into the reactor core. For pressurized heavy water reactors (PHWR), such as the one in Arak, uranium doesn’t need to be enriched, so the yellow cake is directly converted to uranium oxide pellets.

Fuel fabrication is not nearly the technical challenge of building and operating a cascade of centrifuges, but it is not trivial either. No one wants a multi-billion dollar reactor contaminated because a fuel element has failed, so quality control is vital. Fuel rods must not rupture or corrode while in the reactor, which requires careful control of the purity of materials and integrity of seals.