NPT RevCon ends with a consensus Final Document

by Alicia Godsberg

The NPT Review Conference ended last Friday with the adoption by consensus of a Final Document that includes both a review of commitments and a forward looking action plan for nuclear disarmament, non-proliferation and the promotion of the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. In the early part of last week it was unclear if consensus would be reached, as states entered last-minute negotiations over contentious issues. While the consensus document represents a real achievement and is a relief after the failure of the last Review Conference in 2005 to produce a similar document, much of the language in the action plan has been watered down from previous versions and documents, leaving the world to wait until the next review in 2015 to see how far these initial steps will take the global community toward fulfilling the Treaty’s goals. (more…)

Iran Beat Us to It.

Ivan Oelrich and Ivanka Barzashka

Back in October, when Iran put in a request to the IAEA for a new load of fuel for its medical isotope reactor in Tehran, the United States proposed that Iran ship out an equivalent amount of its low enriched uranium (LEU) in exchange. It turns out, purely coincidentally, that the amount of LEU equivalent to about 20-years worth of fuel for the reactor was almost exactly the amount that Iran would need as feedstock to produce a bomb’s worth of material. No one seems to question Iran’s right to purchase fuel, but the purpose of the swap was two-fold: to get the bomb’s worth of LEU out of Iran, which would have left Iran with less than a bomb’s worth of LEU feedstock, and to provide a seed for improved cooperation and trust. (more…)

FAS side events at the RevCon

by Alicia Godsberg

Yesterday FAS premiered our documentary Paths To Zero at the NPT RevCon. The screening was a great success and there was a very engaging conversation afterward between the audience and Ivan Oelrich, who was there to promote the film. As a result of some suggestions, we are hoping to translate the narration to different languages so the film can be used as an educational tool around the world. You can see Paths To Zero by following this link – we will also be putting up the individual chapters soon.

This morning I spoke at a side event at the NPT RevCon entitled “Law Versus Doctrine: Assessing US and Russian Nuclear Postures.” I was asked to give FAS’s perspective on the New START, NPR, and new Russian military doctrine. Several people asked me for my remarks, so I’m posting them below the jump. (more…)

Speaking at the NPT-Review Conference

|

| The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference is Underway in New York |

By Hans M. Kristensen

I gave two talks at the review conference of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, both on non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The first was an FAS/BASIC panel on May 10 on Prospects for a shift in NATO’s nuclear posture.

The second was a panel organized by Pax Christi on May 12 on NATO’s nuclear policy.

My prepared remarks follow below:

U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Which Way Forward?

Hans M. Kristensen

Director, Nuclear Information Project

Federation of American Scientists

Presentation to FAS/BASIC Panel on Shifting NATO’s Nuclear Posture

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference, New York, May 10, 2010I’ve been asked to talk about the status of the deployment in Europe and about the Obama administration’s policy. There are of course many other issues affecting the status and future of the deployment, but let me focus on those two here.

There are currently about 200 U.S. nuclear bombs deployed in Europe. That is a far cry from the peak of 7,300 tactical nuclear weapons that were deployed there in 1971. But comparing with the Cold War is no longer relevant; the issue is how the posture fits the security challenges of today.

The deployment currently is about as big as the entire Chinese arsenal, or nearly as much as India, Pakistan, and Israel have combined. That’s a lot for an arsenal that NATO says is not targeted or directed against anyone.

Yet for an alliance that officially emphasizes the importance of continued and widespread deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, the past two decades have been a contradiction: since 1993 when the withdrawal of ground-launched and naval weapons was completed, these “essential” bombs have been reduced from 700 to 200, the number of nuclear bases reduced from 14 to 6, and the number of countries participating in the NATO strike mission reduced from six to four.

The burden sharing principle has been reduced to a shadow of it former self: out of NATO’s 28 members, only five (18 percent) have nuclear weapons on their territory, and only four (14 percent) have the strike mission. Most recently, three of the remaining four asked NATO to formally discuss the future of the mission.

The practice of equipping and training non-nuclear NPT signatories in NATO with U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities was largely tolerated by the NPT community during the Cold War. But this arrangement is untenable in an era where the focus is on nonproliferation because it muddles the message, condones double standards, and is – plain and simple – in contradiction with the intention of the NPT. It is not a standard NATO or the United States should defend today.

So although some officials cling to Cold War arguments for maintaining U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, the reality is that it is entirely in line with post-Cold War NATO policy and actions to reduce, curtail, and phase out the nuclear mission. It’s not going the other way. So NATO’s focus should not be whether to withdraw the weapons but how.

The top of the new American administration supports a withdrawal from Europe. You might be surprised to hear that given Hillary Clinton’s statements in Tallinn last month and what some defense officials are saying inside. But those statements are part of a strategy intended to avoid triggering a backlash from some Eastern European NATO countries and Turkey that could lock NATO’s Strategic Concept into decades of nuclear status quo.

The strategy reflects that a clear priority of the Obama administration is to reassure allies and partners and repair the rift that began to open during the previous administration. The Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), the Ballistic Missile Defense Review (BMDR), and the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) all emphasize this, and all hint of changes to come in the European deployment.

The QDR states: “To reinforce U.S. commitments to our allies and partners, we will consult closely with them on new, tailored, regional deterrence architectures that combine our forward presence, relevant conventional capabilities (including missile defenses), and continued commitment to extend our nuclear deterrent. These regional architectures and new capabilities, as detailed in the Ballistic Missile Defense Review and the forthcoming Nuclear Posture Review, make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” (Emphasis added.)

The BMDR is a little more explicit, stating: “Against nuclear-armed states, regional deterrence will necessarily include a nuclear component (whether forward-deployed or not). But the role of U.S. nuclear weapons in these regional deterrence architectures can be reduced by increasing the role of missile defenses and other capabilities.” (Emphasis added.)

Although the NPR states that the presence of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe and the nuclear sharing arrangement “contribute to Alliance cohesion and provide reassurance to allies and partners who feel exposed to regional threats,” it also reminds that extended deterrence relies less and less of nuclear weapons and that the role will continue to decrease as the new, regional, deterrence architecture matures.

This new, tailored, regional deterrence architecture includes all components of U.S. military capabilities, ranging from effective missile defense, counter-WMD capabilities, conventional power-projection capabilities, and integrated command and control – all underwritten by strong political commitments. The missile defense, the NPR states explicitly, is “part of our extended deterrent and a visible demonstration of our Article 5 commitment to Europe.”

So it is important to understand that the Obama administration sees its security commitments as much more – and increasingly other – than forward deployment of nuclear bombs in Europe. In fact, the forward deployment is the least relevant today, and many U.S. officials privately make no attempt to conceal that they would like to withdraw the weapons and for NATO to move out of the Cold War.

Not only does the NPR retire the nuclear Tomahawk that supported NATO, there are subtle hints that the nuclear bombs may be withdrawn. The NPR reminds that even if the bombs were withdrawn from Europe, the United States will “retain the capability to forward-deploy U.S. nuclear weapons on tactical fighter-bombers (in the future, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter) and heavy bombers (the B-2 and B-52H).” In addition, the NPR promises, the United States will “continue to maintain and develop long-range strike capabilities that supplement U.S. forward military presence and strengthen regional deterrence.”

The subtle point, I think, is that forward deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe is not very suitable for today’s security challenges, that regional deterrence and reassurance of allies are better served by a new regional security architecture that relies less on nuclear weapons, and that there are plenty of other nuclear capabilities to provide the nuclear umbrella anyway. But none of those changes to U.S. extended deterrence capabilities will be made, the NPR promises, without close consultations with allies and partners.

So I don’t think it’s matter of if but when and how the remaining U.S. weapons will be withdrawn from Europe. The problem with additional gradual unilateral reductions is that it’s hard to cut much more without looking increasingly silly when arguing that the few that will remain are still essential for NATO.

Well aware of this dilemma, opponents of withdrawal have proposed linking further cuts to reductions in Russian tactical nuclear weapons; they know full well that such a link would means nothing will happen anytime soon.

But making further reductions conditioned on Russia reducing its non-strategic nuclear weapons seems insincere because NATO for the past two decades has been perfectly capable of and willing to reduce unilaterally without any demands on Russia. Insisting on reciprocity now, when NATO has been insisting for years that the weapons are not directed against Russia, seems like a step back to the 1980s and intended to shield the last weapons against withdrawal.

Another reason why it makes little sense to link further reductions to Russian reductions is that the improved conventional and missile defense capabilities that are required by the new, tailored, regional deterrence architecture likely will deepen Russian concerns about NATO conventional capabilities. Even though Russia’s non-strategic forces are expected to decline significantly during the next decade, this will probably increase the importance of the remaining weapons in Russian thinking even more.

Fortunately, none of this prevents a unilateral withdrawal of the remaining U.S. weapons from Europe. Indeed, it seems that the way forward is perhaps a two-step process beginning with ending the nuclear sharing mission followed by complete withdrawal a little later. Whatever the schedule is, the good news is that reducing the deployment in Europe is both consistent with NATO history and security interests.

Thank you.

U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Status and Issues

Hans M. Kristensen

Presentation toPax Christi Panel on Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Europe

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference, New York, May 12, 2010I’ve been asked to talk about the status of the deployment in Europe and what some of the implications are for NATO.

The 200 U.S. nuclear bombs currently deployed in Europe are a far cry from the peak of 7,300 tactical nuclear weapons in 1971, but comparing with the Cold War is no longer relevant; the issue is how the posture fits the security challenges of today. The current deployment is about as big as the entire Chinese arsenal, or nearly as much as India, Pakistan, and Israel have combined. That’s a lot for an arsenal that NATO says has no military mission.

Yet for an alliance that officially emphasizes the importance of continued and widespread deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, the past two decades have been somewhat of a contradiction: since 1993 when the withdrawal of ground-launched and naval weapons was completed, these “essential” bombs have been reduced from 700 to 200, the number of nuclear bases reduced from 14 to 6, and the number of countries participating in the NATO strike mission reduced from six to four countries that now appear to have serious doubts about continuing the mission. And burden sharing in NATO is actually not very widespread: out of NATO’s 28 members, only five (18 percent) have nuclear weapons on their territory, and only four of those (14 percent) have the strike mission. So nuclear burden sharing is the exception, not the rule, in NATO.

There are several issues that need to be addressed. The first is the mission. NATO is fond of saying that the forward deployment no longer has any military mission. It only serves as a symbol of the U.S. commitment to defend NATO, and without this forward symbol, so the argument goes, the U.S. security interest in Europe would weaken. Whether one agrees with this argument – and I for one believe it is absolutely nonsense – the last thing Europe should look to as the Atlantic glue is a deployment that the United States itself no longer thinks is important. There is a view forming back in Washington that it’s kind of silly for some of the NATO governments to continue to put so much emphasis on this deployment and you only have to look to the NPR report to see how much effort it makes to signal to Europe that extended deterrence and Article V do not depend on deploying nuclear bombs in Europe.

NATO is currently reviewing the nuclear mission, of which the forward deployment is a sub-issue. I think the deployment constrains the review and limits NATO’s ability think anew about the appropriate contribution of nuclear weapons to NATO security. No matter how the forward deployment has been adjusted and what one might otherwise think about the virtues of the deployment, it is at its core a Cold War posture.

Related to the mission review is the question of resources. The forward deployment requires special personnel, special equipment, special command and control, special inspections, special security arrangements, special emergency plans, special political and legal agreements, and special funding, all of which compete with conventional missions and place unnecessary burdens on people, equipment, and institutions. The weapons were withdrawn from Lakenheath and Ramstein partly because those bases needed to focus their mission on real-world contingencies. Those who insist that the deployment is still necessary need to demonstrate what the net benefit is to NATO.

The mission review is closely related to how the deployment affects relations with Russia and other potential adversaries. NATO has insisted for two decades that the weapons in Europe are not aimed at Russia or any country. That may or may not be true, but the deployment is frequently used by Russian officials as an excuse to reject constraints on their own non-strategic nuclear weapons. And Russian military planners will necessarily have to plan contingencies against potential NATO attacks with the weapons deployed in Europe. This ties NATO and Russia to a deterrence relationship that they don’t need to have, and that works against closer relations.

We now see some proposing that further reductions in the U.S. deployment should be linked to reductions in Russian non-strategic weapons. That would of course be one way to make sure the U.S. weapons are not withdrawn anytime soon, but making further reductions conditioned on Russia reducing its non-strategic nuclear weapons is misguided for several reasons. First, because NATO for the past two decades has been perfectly capable of and willing to reduce unilaterally without any demands on Russia. Second, the United States has unilaterally reduced its nonstrategic arsenal far more than Russia because these weapons are no longer seen as important to national security. Insisting on reciprocity now, when NATO has been insisting for years that the deployment is not linked to Russia, seems a step back that would give the European deployment an importance it doesn’t deserve and risk complicating prospects for Russian reductions.

Then there is the issue of safety. This is more significant than people generally think. The 200 weapons are scattered in 87 aircraft shelters at six bases in five countries. Ten years ago, the U.S. Air Force discovered that weapons maintenance procedures at the shelters under specific conditions could lead to accidents with a nuclear yield. Two years ago, the Air Force Blue Ribbon Review determined that security at the host country bases did not meet U.S. security standards. And just a few months ago, peace activists at Kleine Brogel demonstrated loudly and clearly that despite extensive security arrangements unauthorized people can get deep into a nuclear base and very close to the weapons. The widespread deployment was designed to survive a Soviet attack, but in today’s world widespread deployment is out of sync with nuclear weapons storage in the age of extreme terrorism.

Finally there is the issue of NATO’s nonproliferation standard. The practice of equipping and training non-nuclear NPT signatories in NATO with U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities was largely tolerated by the NPT community during the Cold War. But this arrangement is untenable in an era where the focus is on nonproliferation because it muddles the message, creates double standards, and is – plain and simple – in contradiction with the intention of the NPT. It is not a standard that NATO or the United States should defend today. The nuclear sharing is simply not important enough to justify this contradiction.

—

The top of the new American administration supports a withdrawal from Europe. You might be surprised to hear that given Hillary Clinton’s statements in Tallinn last month and what some defense officials are saying inside. But those statements are, I think, part of a strategy intended to avoid triggering a backlash from some Eastern European NATO countries and Turkey that could lock NATO’s Strategic Concept into another two decades of nuclear status quo.

Not only does the NPR retire the nuclear Tomahawk that supported NATO, there are subtle hints that the bombs may be withdrawn. The NPR reminds that even if the nuclear bombs were withdrawn from Europe, the United States will “retain the capability to forward-deploy U.S. nuclear weapons on tactical fighter-bombers (in the future, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter) and heavy bombers (the B-2 and B-52H).” In addition, the NPR promises, the United States will “continue to maintain and develop long-range strike capabilities that supplement U.S. forward military presence and strengthen regional deterrence.”

The subtle message to NATO, I think, is that the Obama administration does not believe that forward deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe is necessary for today’s security challenges, that regional deterrence and reassurance of allies are better served by a new regional security architecture that relies less on nuclear weapons, and that there are plenty of other nuclear capabilities to provide the nuclear umbrella to the limited extent that that is necessary. Such a posture has been in effect in Northeast Asia since 1992, and many U.S. officials privately make no attempt to conceal that they would like to withdraw the weapons from Europe too and for NATO to move on.

So I don’t think it’s matter of if but when and in what form the U.S. weapons will be withdrawn from Europe. A way forward might be a two-step process beginning with ending the nuclear sharing mission followed by complete withdrawal a little later. Whatever the schedule is, the good news is that reducing the deployment in Europe is both consistent with NATO history and security interests and the views of the new American administration.

Thank you.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

2010 RevCon begins

by Alicia Godsberg

Today marked the opening of the 8th Review Conference to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons at the United Nations. The general debate began today and will continue through Thursday, with an NGO presentation to the delegates this Friday to end the week. Today’s plenary provided a few revelations from the U.S. and Indonesia that could impact the rest of the RevCon and the nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament regime in general… (more…)

Documentary “Paths to Zero” Premiering at the NPT RevCon

by: Alicia Godsberg

On Tuesday May 11 FAS will be premiering our documentary, “Paths to Zero,” at the United Nations during the 2010 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT RevCon). The screening will be part of FAS’s official UN Office of Disarmament Affairs side event for the RevCon, which will be held from 10 am – 12 pm in Conference Room A of the North Building. To attend, you must be registered for the RevCon, but after the Conference FAS will be screening Paths to Zero in Washington, DC and we will be uploading the video to our website.

The world’s combined stockpile of nuclear weapons remains at a high and frightening level – over 24,000 – despite being two decades past the end of the Cold War. In the documentary film Paths to Zero, Federation of American Scientists Vice President Dr. Ivan Oelrich explains the history of how the nuclear-armed world got to this point, and how we can begin to move down a global path to zero nuclear weapons.

The Twenty Percent Solution: Breaking the Iranian Stalemate

President Obama’s deadline to address concerns about Tehran’s nuclear program passed at the end of 2009, so the White House is moving to harsher sanctions. But the U.S. is having trouble rallying the needed international support because Iranian intentions remain ambiguous.

Twenty Percent Solution: Breaking the Iranian Stalemate

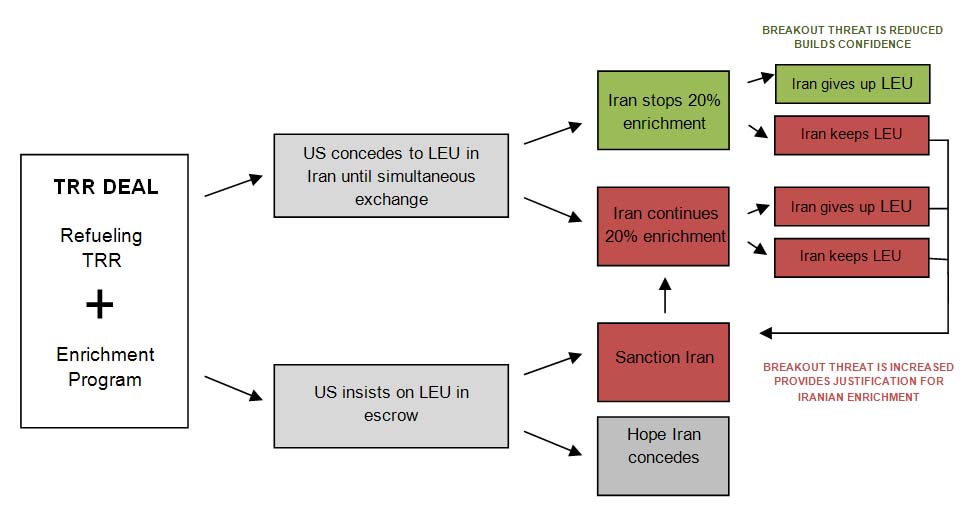

by Ivanka Barzashka and Ivan Oelrich

Iran and the rest of the world are stalemated. Obama’s deadline for Tehran to address concerns about its nuclear program passed at the end of 2009, so the White House is moving to harsher sanctions. But the US is having trouble rallying the needed international support because Iranian intentions remain ambiguous. The deadlock includes negotiations on fueling Iran’s medical isotope reactor. With no progress on that front, Iran has begun its own production of 20-percent uranium for reactor fuel, a worrying development that could put Iran closer to a nuclear weapon. Yet, even while talk of sanctions escalates, Tehran says it is still interested in buying the 20 percent reactor fuel from foreign suppliers.

The Tehran Research Reactor (TRR) deal has backfired. The offer, to trade a large part of Iran’s low enriched uranium (LEU) for finished TRR fuel elements, was meant to abate the potential Iranian nuclear threat by reducing Iran’s stockpile of enriched nuclear material. By artificially coupling two distinct problems, re-fueling the TRR and Iran’s enrichment program, the US, France and Russia have given Tehran a reason, even a humanitarian one, to enrich to higher concentrations. The move to 20 percent enrichment will reduce by more than half the time needed for Iran to get a bomb’s worth of material. (more…)

The Revelation of Fordow+10: What Does It Mean?

According to a recent article by the New York Times, Western intelligence agencies and international inspectors now “suspect that Tehran is preparing to build more [enrichment] sites”. This revelation, according to the newspaper, comes at a “crucial moment in the White House’s attempts to impose tough new sanctions against Iran.”

However, these “suspicions” come months after Iran publicly disclosed such intentions. Tehran declared plans to build 10 additional sites on 29 November 2009, a couple of days after an IAEA Board of Governors resolution called on Tehran to confirm that it had “not taken a decision to construct, or authorize construction of, any other nuclear facility” and suspend enrichment in accordance with UN Security Council resolutions.

At the time, the Iran’s decision to construct more enrichment sites was widely dismissed in the West as an act of defiance and unlikely more than mere bravado. On 30 November 2009 the New York Times wrote that “it [was] doubtful Iran could execute that plan for years, maybe decades”. The same article referred to a high-ranking Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS) official claiming that taking the declaration seriously was “akin to believing in the tooth fairy” and that this effort would likely produce “‘one small plant somewhere that they’re not going to tell us about’ and be military in nature.”

In fact, a week before Iran’s original announcement, Ivan Oelrich and I argued in an article at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists that Fordow is likely one of many similar sites. A technical analysis of the facility’s planned capacity showed that, alone, it was not well-suited for either a commercial or a military function. The facility’s low capacity also undermined other strategic roles suggested by official and quasi-official Iranian sources – that Fordow is a contingency plant in case Natanz were attacked or that Fordow was even meant to deter an attack on Natanz. (more…)

Nuclear Doctrine and Missing the Point.

The government’s much anticipated Nuclear Posture Review, originally scheduled for release in the late fall, then last month, then early February is now due out the first of March. The report is, no doubt, coalescing into final form and a few recent newspaper articles, in particular articles in Boston Globe and Los Angeles Times, have hinted at what it will contain.

Before discussing the possible content of the review, does yet another release date delay mean anything? I take the delay of the release as the only good sign that I have seen coming out of the process. Reading the news, going to meetings where government officials involved in the process give periodic updates, and knowing something of the main players who are actually writing the review, what jumps out most vividly to me is that no one seems to share President Obama’s vision. And I mean the word vision to have all the implied definition it can carry. The people in charge may say some of the right words, but I have not yet discerned any sense of the emotional investment that should be part of a vision for transforming the world’s nuclear security environment, of how to make the world different, of how to escape old thinking. As I understand the president, his vision is truly transformative. That is why he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. His appointees who are developing the Nuclear Posture Review, at least the ones I know anything about, are incredibly smart and knowledgeable, but they are also careful, cautious, and, I suspect, incrementalists who might understand intellectually what the president is saying but don’t feel it (and, in many cases, fundamentally don’t really agree with it). A transformative vision not driven by passion will die. As far as I can see (and, I admit, I am not the least bit connected so perhaps I simply cannot see very far) the only person in the administration working on the review who really feels the president’s vision is the president. Much of what I hear from appointees in the administration has, to me at least, the feel of “what the president really means is…” If the cause of the delay is that yet more time is needed to find compromise among centers of power, reform is in trouble because we will see a nuclear posture statement that is what it is today neatened up around the edges. But if the delay is because the president is not getting the visionary document he demands, delay might be the only hopeful sign we are getting.

Now, onto the possible content of the review: The main question to be addressed by the review is what the nuclear doctrine and policy of the United States ought to be. This has sparked a secondary debate about just how specific any declaration of policy should be and the value of declaratory policy at all.

Some hints coming out of the administration suggest that the new review may explicitly state that the sole purpose of nuclear weapons be specifically limited to countering enemy nuclear weapons, what we and others have called a “minimal deterrence” doctrine. Currently, the United States claims that chemical and biological weapons may merit nuclear attack and that could go away with the current review.

Most reports leaking out from the review participants hint that the NPR almost certainly will not include a declaration that the United States will not be the first to use nuclear weapons. The current U.S. policy is to intentionally maintain ambiguity about how and when we might use nuclear weapons, to keep the bad guys guessing. The new review could keep that basic idea and still be a little less ambiguous around the edges.

Some question the value of having a declaratory policy at all. For example, if a no-first-use policy can be reversed by a phone call from the president, what does it actually mean? As Jeffrey Lewis argues, if having a declared policy causes an intense drilling down into what-ifs, it can increase suspicion and do actual harm. (Although the example Lewis offers raises questions about whether China should have a no-first-use policy and is not particularly relevant to whether the U.S. should.)

A bigger problem with any declaratory policy is figuring out what it actually means. Do we agree on what “no first use” means? I think it means that we will not be the first to explode a nuclear weapon. But, for example, in a recent article in Foreign Affairs, Lieber and Press argue that the United States could be justified in using nuclear weapons if an adversary first “introduced” nuclear weapons into a conflict, where “introduce” might be to explode one, but might also include putting them on higher alert, moving them, or simply implying their relevance to the contest. So a nuclear war-planner and I could agree on a no-first-use policy and have differing, almost opposite, views of what that meant.

But if statements of doctrine don’t mean anything, then why the big deal? Why would the nuclear establishment invest any political capital fighting for or against them? While it is true that doctrinal statements are always taken with a huge grain of salt by other nations (just as the United States applies a steep discount to statements coming from others), they do make a difference in the domestic debate. In the previous administration, the Department of Energy went to the Congress with a request to build a new facility to build the plutonium cores or “pits” for 250 new nuclear warheads every year. This made no sense whatsoever; it was completely out of synch with our own plans for future nuclear forces and Congress voted it down because the DOE was not remotely able to justify its request. The DOE proposal went down to 125, then 80, and some current variations on the basic proposal are for a dozen or so, which actually makes some sense.

So doctrine and declaratory policy are important in very concrete ways when they can affect force structure decisions, including the numbers and types of weapons we have, their capabilities, and how they are deployed. Moreover, these are the sorts of changes that other nations will see and pay attention to.

The uncertainty of the link between words and weapons is what causes wariness on every side of the debate. Foreign governments might not believe our declarations but such declarations might form the basis for changes in the U.S. nuclear force structure, with all the implications for budgets and personnel, weapons, bases, and jobs back home. That is why the nuclear establishment is resisting. On the other hand, those who desire fundamental and profound change could be completely hoodwinked by nice sounding words that allow the status quo to coast ahead on its own momentum.

The danger I see is that, if discussion is so tightly focused on what we say, then too little attention will be given to what we do. If we take our declarations seriously, they should have profound effects on the nuclear posture but I can imagine big changes in the review with little real physical change actually resulting. For example, if we take seriously a no-first-use policy, our deployment of forces could be radically different. Reentry vehicles could be stored separated from their missiles, missiles in silos could be made visibly unable to launch quickly, for example, by piling boulders over the silo doors. Much of the ambiguity in any verbal statement of doctrine is squeezed out when we discuss the concrete questions of what the forces look like. The nuclear war-planner and I might have effectively opposite definitions of “no first use” but we would agree entirely on what it means to piles boulders on our ICBM silo doors.

What I would hope to see come out of the NPR is not simply a statement of no first use but a plan for, for example, taking our nuclear weapons off alert. We will certainly hear that nuclear weapons are for deterrence, perhaps that they are only for deterrence. But that has become utterly meaningless because the definition of deterrence has been warped to the point that it can now be defined as whatever it is that nuclear weapons do. Indeed, nuclear weapons are often simply called our “deterrent.” Michele Flournoy, the current Undersecretary of Defense in charge of the NPR process, wrote a report while at CSIS describing how U.S. nuclear weapons should be able, among other things, to execute a disarming first strike against central Soviet nuclear forces, the better to “deter.” When a word has that much flexibility, I don’t care whether it gets included in the posture statement or not but I do care whether we mount our nuclear weapons on fast flying ballistic missiles or on slow, air-breathing cruise missiles.

If we take seriously some of the statements that might come out of the review, then we can start to imagine radically different force structures. For example, if the requirement for nuclear preemption is removed and the number of nuclear targets is substantially reduced, then new ways to base nuclear weapons become feasible. We could, for example, store missiles in tunnels dug deep inside a mountain where the missiles would be both invulnerable and impossible to launch quickly. We could invite a Russian to live in a Winebago on top of the mountain to confirm to his own nuclear commanders that we were not preparing our missiles for launch.

These are things the world can see. Indeed, if we have no interest in a first strike capability, we have every incentive to invite the world to come in and see for themselves. These are the types of changes that need to occur in the U.S. nuclear force structure and, if they do, debate about the words in the review is less important.

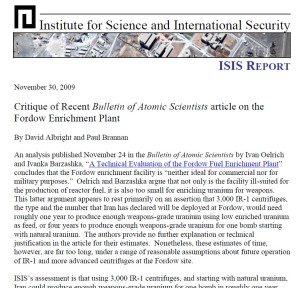

Response to Critiques Against Fordow Analysis

by Ivanka Barzashka and Ivan Oelrich

Our article “A Technical Evaluation of the Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant” published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists on November 23 and its technical appendix, an Issue Brief, “Calculating the Capacity of Fordow”, published on the FAS website, have sparked quite a discussion among the small community that follows the technical details of Iran’s program, most prominently by Joshua Pollack and friends on armscontrolwonk.com (on December 1 and December 6) and by David Albright and Paul Brannan at ISIS, who have dedicated two online reports (from November 30 and December 4) to critiquing our work. (more…)

Calculating the Capacity of Fordow – Updated Issue Brief Posted

by Ivanka Barzashka

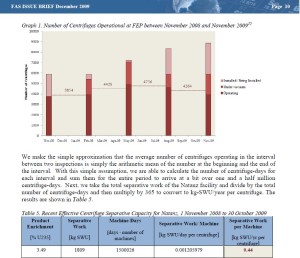

We have posted an updated version of our latest Issue Brief “Calculating the Capacity of Fordow” – the technical appendix to our November 23 article “A Technical Evaluation of the Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant” published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

This is the document summary:

This brief serves as a technical appendix to our November 23 article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which premised that Iran’s Fordow enrichment plant is well-sized neither for a commercial nor military program. We concluded that Fordow may be one of several facilities planned. Our estimates of the plant’s capacity are based on current performance of IR-1 centrifuges at Natanz. Underlying our assessment is a calculation of the effective separative capacity per machine of 0.44 kg-SWU/year. This result is based on IAEA data, which we consider as the most credible open-source information on Iran’s nuclear program. Our estimate for the IR-1 performance is significantly lower than values published in the literature, which cannot account for the current performance of Natanz. We argue that, despite Iranian rhetoric, Tehran’s strategic planning for Fordow is based on actual enrichment performance rather than on desired results.

We have made significant layout improvements and have edited the text for clarity. More importantly, we have added detailed explanations on the calculations behind two additional scenarios that we considered in the Bulletin article, namely producing LEU for a commercial reactor from natural uranium and producing a bomb’s worth of HEU from LEU. We have used more precise numbers than the conservative estimates reflected in the Bulletin article, which yield longer timelines and only strengthen our conclusions. Also, version one of the Brief contained numbers only on Fordow’s capability to produce a significant quantity of HEU from natural uranium. This was the only scenario that we have received questions about despite the fact that all three calculations are based on the same premise regarding the effective capacity of the IR-1.

In addition, we have included a section explaining our rationale behind using IAEA’s significant quantity as the amount of uranium required for a bomb. When allowing the Iranians the opportunity to get to a “bomb’s worth” of material faster by assuming less material is needed, one is also assuming a more sophisticated bomb design that will require a longer design phase and will almost certainly require testing, which will be unambiguous. In effect, cutting down on the material production time will result in a longer time to develop a weapon.

We thank everyone for their interest in our work and will address published criticisms directly in an upcoming blog.