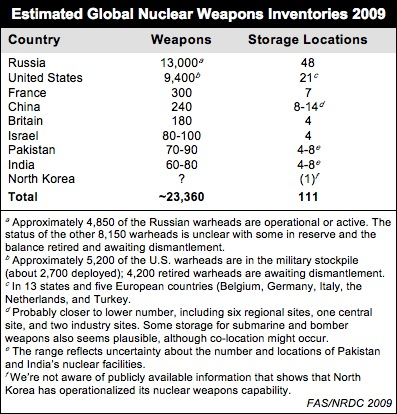

Estimated Nuclear Weapons Locations 2009

Some 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at 111 locations around the world

.The world’s approximately 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at an estimated 111 locations in 14 countries, according to an overview produced by FAS and NRDC.

Nearly half of the weapons are operationally deployed with delivery systems capable of launching on short notice.

The overview is published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and includes the July 2009 START memorandum of understanding data. A previous version was included in the annual report from the International Panel of Fissile Materials published last month.

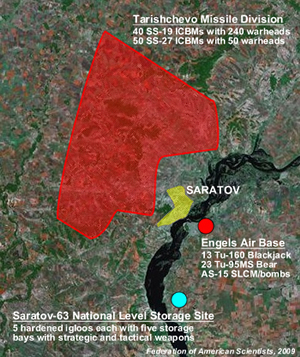

More than 1,000 nuclear weapons surround Saratov.

Russia has an estimated 48 permanent nuclear weapon storage sites, of which more than half are on bases for operational forces. There are approximately 19 storage sites, of which about half are national-level storage facilities. In addition, a significant number of temporary storage sites occasionally store nuclear weapons in transit between facilities.

This is a significant consolidation from the estimated 90 Russian sites ten years ago, and more than 500 sites before 1991.

Many of the Russian sites are in close proximity to each other and large populated areas. One example is the Saratov area where the city is surrounded by a missile division, a strategic bomber base, and a national-level storage site with probably well over 1,000 nuclear warheads combined (Figure 2).

The United States stores its nuclear weapons at 21 locations in 13 states and five European countries. This is a consolidation from the estimated 24 sites ten year ago, 50 at the end of the Cold War, and 164 in 1985 (see Figure 3).

Approximately 50 B61 nuclear bombs inside an igloo at what might be Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada. Seventy-five igloos at Nellis store “one of the largest stockpile in the free world,” according to the U.S. Air Force, one of four central storage sites in the United States.

Europe has about the same number of nuclear weapon storage locations as the Continental United States, with weapons scattered across seven countries. This includes seven sites in France and four in Britain. Five non-nuclear NATO countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey) still host U.S. nuclear weapons first deployed there during the Cold War.

We estimate that China has 8-14 facilities associated with nuclear weapons, most likely closer to the lower number, near bases with units that operate nuclear missiles or aircraft. None of the weapons are believed to be fully operational but stored separate from delivery vehicles at sites controlled by the Central Military Commission.

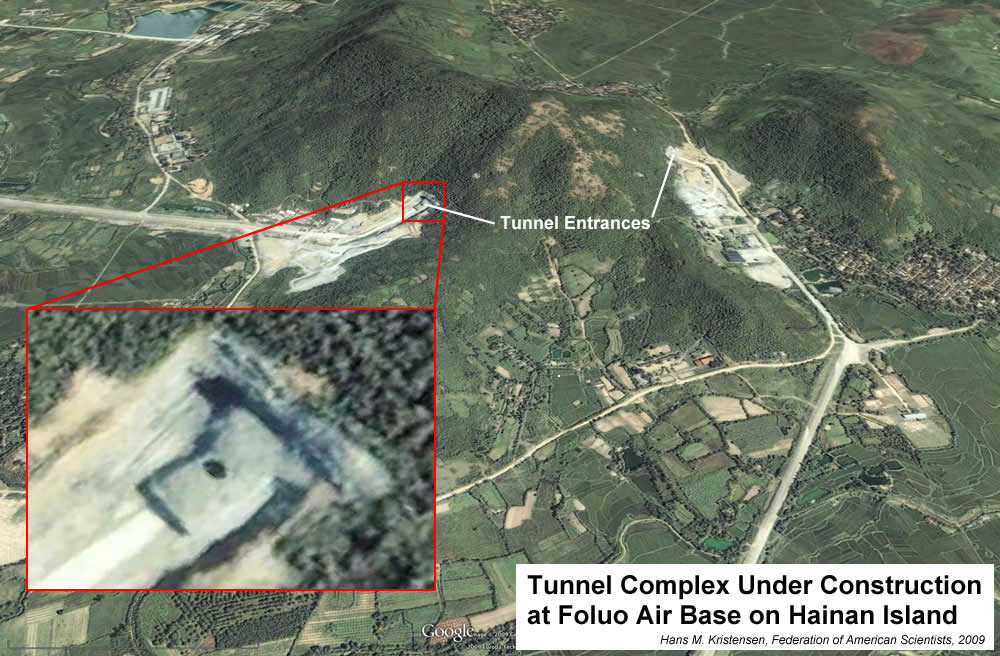

Where does China store nuclear warheads for its ballistic missile submarines? The naval base near Julin on Hainan Island has extensive underground facilities. An alternative to the base itself could potentially be a facility elsewhere on the island, such as Foluo Air Base where construction of an underground facility began five years before the first SSBN arrived at Hainan. Or are the weapons stored on the mainland? Click image to enlarge.

Israel probably has about four nuclear sites, whereas the nuclear storage facilities in India and Pakistan are – despite many rumors – largely undetermined. All three countries are thought to store warheads separate from delivery vehicles.

Despite two nuclear tests and many rumors, we are unaware of publicly available evidence that North Korea has operationalized its nuclear weapons capability.

Warhead concentrations vary greatly from country to country. With 13,000 warheads at 48 sites, Russian stores an average of 270 warheads at each location. The U.S. concentration is much higher with an average of 450 warheads at each location. These are averages, however, and in reality the distribution is thought to be much more uneven with some sites only storing tens of warheads.

Finally, a word of caution is in order: estimates such as these obviously come with a great deal of uncertainty, as we don’t have access to classified intelligence estimates. Based on publicly available information and our own assumptions we have nonetheless produced a best estimate that we hope will assist the public debate. Comments and suggestions are encouraged so we can adjust the overview in the future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

No U.S. Nukes in South Korea

|

|

North Korea mistakenly believes there are U.S. nuclear weapons in South Korea. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The North Korean newspaper Rodong Sinmun reportedly has issued a statement saying the U.S. has 1,000 nuclear weapons in South Korea. In this regional war of rhetoric it is important to at least get one fact right: The United States does not have nuclear weapons in South Korea. It used to – at some point close to 1,000 – but the last were withdrawn in 1991.

The only nuclear weapons the United States has in the Pacific today are the hundreds of warheads deployed on Trident II D5 sea-launched ballistic missiles on board eight Ohio-class nuclear-powered submarines patrolling in the Pacific Ocean. Some of them may be earmarked for potential use against targets in North Korea. Other weapons for bombers could be moved into the region if necessary, but they’re not today.

The North Korean obsession with the U.S. nuclear “threat” might be seen as confirmation that the nuclear deterrent works and hopefully will deter North Korea from attacking anyone. But the flip side of the coin is to what extent the U.S. nuclear posture in the Pacific – past and present – helps feed the North Korean nuclear rhetoric and perhaps even ambitions.

Additional information: A history of U.S. nuclear weapons deployment to and withdrawal from South Korea.

North Korea’s Nuclear Test: Another Fizzle?

|

| The North Korean nuclear test on May 25, 2009, was “heard” loud and clear around the world despite its apparent limited size. Detection of small, clandestine nuclear tests seems to work. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

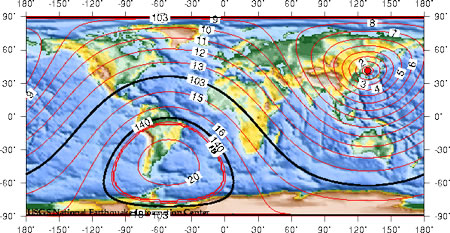

The Korean Central News Agency reportedly has announced that North Korea “successfully conducted one more underground nuclear test on May 25 as part of measures to bolster its nuclear deterrent for self-defense.” Several news media reported that the Russian Ministry of Defense estimating the test had a yield of approximately 10 to 20 kilotons.

Yet the preliminary seismic data published by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) shows that the test had a seismic magnitude of 4.7, only slightly more powerful than the 4.3 of the 2006 test.

Was it another fizzle? We’ll have to wait for more analysis of the seismic data, but so far the early news media reports about a “Hiroshima-size” nuclear explosion seem to be overblown.

Update: CTBTO’s initial findings.

.

North Korea Launches Rocket but Satellite Fails

Despite a world of advice to the contrary, the North Koreans launched their Taepodong-2 or Unha rocket yesterday morning. Recent reports are that the first two stages operated correctly but the third stage failed. Reading between the lines a bit, it might have failed to ignite rather than exploding. This seems to be a replay of the Taepodong-1 test satellite launch attempt: In that case, both stages one and two seemed to operate properly but the third stage apparently exploded and the satellite never entered orbit. (That failure did not discourage the North Koreans, who announced that the whole thing was a great success and the satellite was up there. My bet is they will do the same thing this time.)

So was the test a failure? Not at all. The reason the world is worried about this test is not because we are worried about competition in the satellite launch business. (Good luck to them!) The world worries because the launcher the North Koreans used is a Taepodong-2, which most everyone believes is their next step up toward a long-range ballistic missile. By taking a warhead off and putting a small third stage and a satellite on top, they might call it a space launcher but the first two stages are exactly the same. The last time the configuration was tested, it exploded 40 seconds into its flight and that flight was a clear failure. No doubt, the North Koreans would have been happier this time with a little satellite up there broadcasting patriotic songs but everything they needed to test for a military missile appears to have worked in yesterday’s test. From the military perspective, the test at this point seems to have been largely successful, in that it demonstrated what needed to be demonstrated and the North Koreans got the information they needed to get.

Does this mean they have a missile that can reach the United States? Well, not really. This test is a big step forward for them but one test does not make a ballistic missile program. There is much more for them to do. We have no idea what they judge the accuracy of the missile and they have not tested an appropriate reentry vehicle. This missile test is an very unfortunate development. I wish the North Koreans had more finese. But it does not give them a ballistic missile capability yet.

Addendum: More information is coming it. Apparently, not only did the satellite fail to enter orbit, but the second stage fell short of the predicted impact area. That suggests that the second stage failed. It could even be that the third stage operated successfully–separated, ignited, guidance worked, and so forth–but without the proper speed and altitude provided by the second stage, it would have no chance of making orbit. If this turns out to be the case, then the conclusions above have to be modified and this is a more limited step forward for the North Korean Taepodong-2 program.

North Korea’s Teapodong-2 Unha Missile Launch: What might we learn?

Indications are that North Korea is moving ahead with its planned launch of a missile with the intent of placing a satellite into orbit. The North Koreans are portraying the launch in purely innocuous, civilian terms even naming the rocket “Unha,” which means “Milky Way” in Korean, to emphasize its space-oriented function. In the West, the rocket is called the Taepodong-2 and is thought to be a long-range (but not truly intercontinental range) ballistic missile.

Even if the rocket launches a satellite, and recent news reports say the payload sections seems to be shaped and sized for a satellite, it would be an important step in their military ballistic missile program. In the early days of the Soviet and American space programs, there was little distinction between military and civilian rocket development and the same would be true of North Korea’s upcoming launch. What I want to discuss in this essay is the question of how much can the outside world learn if the North Korean test goes through, what does it tell us about their ballistic missile capability?

According to the North Korean statements, the Kwangmyongsong-2, or Bright Star Light, satellite is a communications satellite. This is transparently nonsensical, of course. Most communication satellites are in geosynchronous orbit, far beyond the reach of the North Koreans. A single satellite in low Earth orbit will not be a useful communications satellite and I do not believe anyone is expecting the North Koreans to launch a whole constellation of satellites. Perhaps what they mean by a “communications satellite” is that the satellite will be communicating to us, not being used by people to communicate among themselves. According to North Korea, their last satellite, launched in August 1998, orbited the Earth continuously broadcasting the “immortal revolutionary” tune, “Song of General Kim Jung Il.” (This is consistent with the name, Kwangmyongsong or Bright Star Light or Bright Lode Star, is one of the innumerable sobriquets of Kim Jung Il.) Such a satellite never existed in fact. All reports from outside North Korea state that the last stage of the rocket exploded, destroying the satellite. United States Space Command has never tracked any object that could be the North Korean satellite and has detected no such transmission from space. (There is a musical precedent: The first Chinese satellite, which had the notable distinction of actually going into orbit, transmitted the tune, “The East Is Red.”)

The 1998 launch used a Taepodong-1 missile as the space launch vehicle (SLV). The Taepodong-1 is made up of a Nodong missile as a first stage with a Hwasong-6 missile as a second stage. (We should keep in mind that some North Korean missiles, such as the Nodong and Hwasong-6, have been produced in number and even exported so they are well characterized. The Taepodongs are different, they have never been successfully test flow and they are put together from other components. I am somewhat uncomfortable assigning them names as though they are production missiles; at this stage, each one might me a one-off. We shall see.) In the 1998 flight, a third stage was added to boost the small satellite into orbit. It was this additional third stage that apparently failed so the North Koreas could have got substantial and important data on the performance of the first two stages that would have made up the two stages of a military ballistic missile.

The Taepodong-2 was tested only once in 2006 and exploded about 40 seconds into its flight and it seems this upcoming launch is a retry of that failed test. The first stage of the Taepodong-2 appears similar to the Chinese CSS-2 missile. David Wright speculates that the first stage will have four Nodong engines operating together. A single Nodong serves as the second stage. The North Koreans have declared warning zones where the first and second stages are expected to impact. David Wright and Geoffrey Forden have worked backward from the announced splash down zones to see whether they are consistent with the presumed configuration of the Taepodong-2 and they check out.

It would be better for the world if the North Koreans did not go through with this test (perhaps the best outcome would be for the rocket to blow up a few seconds into its flight test—we can always hope) but if they conduct the test, the rest of the world might as well learn as much as we can from it and we can learn a lot.

The missile is being launched from the sort of launch pad that one would expect for a SLV. It is being assembled out in the open and the North Koreans are making no effort to hide the missile. The press has released some low resolution images but the United States, and others, have photo-satellites that can take much higher resolution images, perhaps seeing detail down to several centimeters. It is conceivable that the United States and perhaps others are bold enough to fly unmanned drones nearby to take even more detailed photographs. But unless a drone gets shot down, do not expect any public announcement from either side. So while we on the outside speculate about what the size and shape of the missile is, national intelligence services already know that before the missile even flies.

The missile will be tracked by radar—the Americans and Japanese have radar ships in the area and South Korean and Japanese will have ground-based radar—and this will provide a detailed, instant-by-instant record of the trajectory of the missile. That allows a calculation of the acceleration, which, in turn, allows us to calculate the ratio of the thrust to the weight of the rocket. If we knew one of those, we could then calculate the other and we will get to ways to determine the weight.

The rocket will accelerate and the rate of acceleration will increase because the thrust of the engines remains constant (some more advanced rockets do fancy things with throttling their engines but the North Koreans are probably not there yet) but the rocket is always getting lighter because it is burning up fuel all the time. So we do not know the weight of the rocket, or the thrust, or the fuel flow, but we can figure out all the ratios and some unknowns cancel out in the equations. By seeing how fast the acceleration changes, we can figure out one of the most important measures of rocket technology, the specific impulse. Specific impulse is the amount of “impulse” or total push (technically, momentum change) provided by a given amount of fuel. It is measured in newton-seconds/kilogram or, in English units, pound-seconds/pound. (Some American engineers cancel the pounds of force in the numerator and the pounds of mass in the denominator and report specific impulse in units of seconds, which makes any good physicist weep. And trust me, I will get tons of letters explaining how I am totally wrong and don’t understand specific impulse.) The specific impulse depends on the type of fuel, the efficiency of the combustion, and the maximum temperatures and pressures that the rocket engine can stand, all things that are technical challenges, making specific impulse a good measure of overall technical sophistication of a rocket builder.

Keep in mind that, for long-range rockets, the initial weight of the fuel is about 90% of the total weight, the structure—the tanks, engines, and so forth—are most of the remaining 10% and only a couple of percent of the total weight is payload. So when the rocket first takes off, the fuel is mostly lifting itself. So the efficiency of converting the fuel into thrust is critical; small changes in efficiency translate into large changes in payload that can be delivered to great distances.

As the first two stages separate, they will fall back to Earth. Radar will be able to track their trajectories as well and measure how they are decelerated by falling through the atmosphere. If we knew the drag coefficient of the stage, then, in principle, we could figure out the weight of the empty stage. The problem is that the stages will be tumbling in some complex way as they go down. Even so, by measuring the radar cross section at each instant, particularly at a variety of radar frequencies, and comparing measurements from more than one radar, a computer could develop a picture of how the stage tumbles and then calculate the air resistance and, from that, the weight of the empty stage. I do not know whether the accuracy is great enough to add to information that we would have from other sources, for example, based on knowledge of the Chinese CSS-2 missile. When the stage breaks up in the atmosphere, all bets are off but the first stage at least might hit the water intact. That raises the interesting possibility that pieces could be recovered but the predicted impact area is over very deep water.

Based on past North Korean practice, we know the general category of propellant the rocket uses but not the precise type. The oxidizer will be nitrogen tetroxide or nitric acid or some mixture of the two. The fuel could be kerosene or something more energetic, like dimethyl hydrazine. The two stages could use different propellants. I wondered whether, by observing the plume from the rocket, perhaps from space, and analysis of the spectra, it would be possible to determine the type of propellant. I discussed the idea with a couple of people and the consensus is that you could identify atomic species but not ratios. So the spectrum would reveal nitrogen, but not enough information to know that it came from nitric acid or hydrazine. In fact, the specific impulse will be a better indicator of the propellant type.

Remember that radar tracking gives us ratios, of weight to thrust, for example. If we had one, we could calculate the other but we cannot calculate payload mass directly. If this were a ballistic missile test, then the weight of the reentry vehicle could be determined by watching how it decelerated in the atmosphere. Then we could make a guess as to whether they could build a nuclear bomb within that size and weight. But this looks to be a satellite launch. Instead of a reentry vehicle, the rocket will have a small third stage that will push a small satellite into orbit. The payload ends up in a ballistic orbit in space where there is no air resistance (or very little). So a one kilogram satellite will follow the same trajectory as a thousand kilogram satellite. That is unfortunate, because if we knew how much the third stage weighed, or how much the rocket could launch into space, then we could calculate how far the rocket could throw a payload of any chosen weight. Because the payload ends up in space, we have to make some guesses about the weight.

Telemetry offers the potential for a great deal of information. By intercepting telemetry, we could get direct information on fuel flows and the like. Since the Taepodong-2 is still being developed—they have never had a successful launch—one would expect the North Koreans to have the rocket heavily instrumented and to transmit all those data back. They might do that but, in past flights, their telemetry has been quite limited.

Could the United States shoot the rocket down? Well, sort of. We do not have the capability to intercept the boosting rocket. But a satellite has to be boosted up to the point where it enters its orbit. (In fact, that is sort of the definition of the “orbit,” the point where the boosting stops and the object goes into an unpowered ballistic trajectory; if it is a ballistic trajectory that doesn’t later intercept the atmosphere, we call it an orbit.) The United States has already demonstrated that it can intercept low altitude satellites; lat year the Navy intercepted an old U.S. spy satellite in a decaying orbit. That was in some ways an easier target because the path could be calculated days in advance. While the North Korean satellite is still under power and being boosted up to orbit, it will not have a perfectly predictable path, making intercept complex but not impossible especially because, based on the predicted first and second stage impact areas, we can make a good guess about the flight path and the Aegis missile could be positioned to make an intercept of the third stage or the satellite before it reached final orbit. Note that this intercept would destroy the satellite, which is a stunt which is just a North Korean stunt anyway, but does not deny any information to the North Koreans about what they presumably really care about, a two-stage ballistic missile with military applications. So, intercept of the third stage might give the U.S. some macho pleasure but would not accomplish any military goal. (It would have political implications that I won’t even try to guess at.)

Does this mean that Aegis would work as an intercontinental ballistic missile defense? No, for several reasons, for example, a ballistic missile does not have to power the reentry vehicle up to orbit, the rockets burn for three to five minutes and the RV is on its way and the trajectory is pointing up rather than horizontally, quickly getting out of range of the Aegis.

Overall, the outside world will gather a lot of information about the Taepodong-2 as a ballistic missile based on this satellite test. We will not know the exact payload and range of the ballistic missile version but will certainly know a great deal more than we do now. Unfortunately, so will the North Koreans. Especially since their test of a nuclear explosive, this is a dangerous development.

Nuclear Déjà Vu At Carnegie

By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

Only one week before Barack Obama is expected to win the presidential election, Defense Secretary Robert Gates made one last pitch for the Bush administration’s nuclear policy during a speech Tuesday at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

What is the opposite of visionary? Whatever, that’s the word that best describes Mr. Gates’s speech. Had it been delivered in the mid-1990s it would not have sounded out of place. The theme was that the world is the way the world is and, not only is there little to be done about changing the world, our response pretty much has to be more of the same.

Granted, Gates’s job is to implement nuclear policy not change it but, at a time when Russia is rattling its nuclear sabers, China is modernizing its forces, some regional states either have already acquired or are pursuing nuclear weapons, and yet inspired visions of a world free of nuclear weapons are entering the political mainstream, we had hoped for some new ideas. Rather than articulating ways to turn things around, Gates’ core message seemed to be to “hedge” and hunker down for the long haul. And, while his arguments are clearer than most, this speech is yet another example of faulty logic and sloppy definitions justifying unjustifiable nuclear weapons.

They Do It So We Must Do It Too

Reductions cannot go on forever, Secretary Gates argues because there is still a mission for nuclear weapons. Using language from the Clinton Administration, he says we can reduce our arsenal but we must also “hedge” against unexpected threats. He said, “Rising and resurgent powers, rogue nations pursuing nuclear weapons, proliferation of international terrorism, all demand that we preserve this hedge. There is no way to ignore efforts by rogue states such as North Korea and Iran to develop and deploy nuclear weapons or Russian or Chinese strategic modernization programs.”

While the potential threats he lists are real and must be addressed, how do nuclear weapons address these threats? And even if there were some nuclear component to our responses, the nature of those responses would be so varied that lumping these threats together muddles the issue. A nuclear response to international terrorism? Even if, for example, al Qaeda used a nuclear weapon to attack an American city, what target would we strike back at with a nuclear weapon? The implicit argument of symmetry is unsustainable. Just as we don’t respond to roadside bombs with our own roadside bombs, nor would we respond to chemical attack with chemical weapons or biological attack with biological weapons. We might respond to nuclear attack with nuclear weapons but we should not allow this to be an unstated assumption. The reason rogue nations, let’s say Iran and North Korea, are developing nuclear weapons is not to counter our nuclear weapons but as a counter to our overwhelming conventional capability. They certainly are not making the mistake of implicitly assuming symmetry.

The near universal logical sleight of hand is to make some argument for nuclear weapons, let’s say we need them because North Korea has them, and then, when people nod in agreement that we need nuclear weapons, let slip in the assumption that this implies we need the nuclear arsenal the administration wants. Not so fast. If North Korea has one, perhaps we need two, but that does not mean we need two thousand.

It helps to clarify the typically foggy nuke-think if we remove Russia and China from the picture and ask whether the United States could justify anything near its currently planned nuclear arsenal only to deter and defeat rogue states and terrorists. Of course not. And perhaps we don’t need nuclear weapons for regional scenarios at all, given our overwhelming conventional capabilities. So those odds and ends are thrown into the pot just to scare, not to explain, and not because there is any well thought out strategy for how nuclear weapons are going to stop a terrorist attack on an American city, or why it be an appropriate response to a regional state that doesn’t have the capability to threaten the survival of the United States.

Russia is a very different case: Russian long-range nuclear forces are the only things in the world today that could destroy us as a nation and society, just as we could destroy them. While relations with Russia are not friendly, no conceivable difference between the United States and Russia justifies this mutual hostage relationship. This pointless threat to our very existence persists because of a failure of imagination typified by this speech. In this case, it is the nuclear weapons that are creating the threat, not protecting us from it.

That Ole Warhead Production Fever

Whatever the supposed justification of nuclear weapons, the primary purpose of the Secretary’s speech seemed to be to promote the Reliable Replacement Warhead or RRW but again, his argument rests on hidden (and unjustified) assumptions and, at times, misstatements of fact. The basic premise is that, without testing, we are slowly but certainly losing confidence in the reliability of our nuclear arsenal. He said, “With every adjustment, we move farther away from the original design that was successfully tested when the weapons was first fielded.”

We do? The implication is that we have no other choice, what we could do in 1990 we simply can’t reproduce today, like handing a modern-day native American a hunk of flint and asking him to chip out an arrowhead. Why should this be? With a budget of billions of dollars, we can’t duplicate parts that we could make twenty years ago? We can spend billions on the National Ignition Facility to create the world’s most powerful laser but we can’t reproduce a 1980s O-ring? The problem the Secretary describes is certainly possible and something we have to be alert to but it isn’t inevitable; we can maintain weapons within design margins as long as we want and in the past—pre-RRW—that was precisely the plan. And parts of the weapon that are not the nuclear core of the bomb can be improved and modernized and tested as much as we want.

But Mr. Gates claims that we are slowly and helplessly drifting, “So the information on which we base our annual certification of the stockpile grows increasing dated and incomplete.” This implies the Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP) has failed. We believe the Secretary is wrong. Everyone we have talked to who is familiar with the enormous effort that has gone into the SSP says that our understanding of nuclear weapons today is substantially greater than it was the day after our last nuclear test. Our knowledge of the aging of nuclear warheads is increasing faster than the warheads are aging. Early uncertainties and concerns about stability, for example, of the plutonium parts of the weapon have been resolved and the parts have been shown to be stable for many decades, if not a century or more. Our computer models are dramatically and significantly more detailed and sophisticated. In fact, one weapon designer has told us that, given a fixed budget, the best investment of your next dollar would never be in a nuclear test but in more inspections, more computer simulations, more replacement of non-nuclear components, more material tests, more frequent tritium replenishment, and so forth.

|

How Many Times Does Congress Have to Say No? |

|

| Every time the Pentagon has proposed a new nuclear warhead since the end of the Cold War, Congress has refused to fund it. Now that the RRW appears to have been whacked, what will the next proposal for a new warhead look like? |

.

Aside from the question of the reliability of current warheads, Mr. Gates argues that we still need an RRW because we need to modernize. The British, French, Russians, and Chinese are modernizing so we must too, obviously. Why? Nuclear weapons are a mature technology. There is no new science in nuclear weapons. They are powerful, efficient explosives. They are intended to blow up things and they have specific missions, which typically involve blowing up specific things. If they can accomplish these missions, what is the problem? If the technology, even the weapons, is decades, even centuries old, if they work then they work. Nuclear weapons are not fighter planes or tanks or submarines, duking it out on a battlefield with the enemy’s opposite number, so our nuclear weapons should be evaluated with regard to the targets they are expected to destroy, not anyone else’s nuclear weapons. They can destroy the targets. We’re done.

The important factor is not the warhead but the delivery vehicle that is intended to bring the warhead to the target. And the reason the United States is not producing new nuclear weapons while Russia and China do is not because they can and we can’t, or they’re ahead and we’re behind, as the Secretary indicated. Rather, the United States has not been producing new nuclear weapons because it didn’t have to – the existing ones are more than adequate – and because not producing has been seen as much more important to U.S. foreign policy objectives. And if Russian and Chinese warhead production is a problem, why not propose how to influence them to change rather than advocating that we repeat their mistake?

The final argument for the RRW is that the US must maintain a nuclear production industry and the RRW is grist for that mill. But many of the RRW technologies and capabilities were developed by the very SSP that Gates now implies is failing. Six years ago – before they came up with RRW after having failed to get permission to build the Precision Low-Yield Weapon Design (PLYWD) and the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP) – the National Nuclear Security Administration assured Congress: “We believe the life extension programs authorized by the Nuclear Weapons Council for the B61, W80, and the W76 will sufficiently exercise the design, production and certification capabilities of the weapons complex” (emphasis added). That assurance was given after the Foster Panel recommended, “developing new designs of robust, alternative warheads.” Now the claim suddenly is that the life extension programs do not sufficiently exercise the weapons complex. At least get the argument straight.

What’s Around the Corner?

We would be more sympathetic to the production argument if the fundamental minimal needs of the nuclear production industry were better thought out and justified, but what we see is an effort to maintain a slimmed down version of what we have without thinking through what we need. In fact, if maintaining the production industry is the core objective, we would have expected the administration to ask for an RRW design that doesn’t need a complex production industry, one that is extremely simple, perhaps using uranium rather than plutonium, perhaps a clunky design but one sure to work that does not require any sophisticated skills that must be maintained in standby in perpetuity.

We’re concerned that in the end Congress will accept a beefed-up life extension program – they seem to have already found a name for it: Advanced Certification Program – that will relax the restrictions for what modifications can be made to existing warheads in order to incorporate as much as the RRW concept as possible and add new capabilities if necessary. Unless the next president significantly changes the nuclear guidance for what the Pentagon is required to plan for, RRW-like proposals will likely continue to make it harder to create a national consensus on the future role of nuclear weapons. And Barack Obama has not explicitly rejected the RRW, but said he does “not support a premature decision to produce the RRW” and “will not authorize the development of new nuclear weapons and related capabilities.” Enhanced life-extended warheads could fit within such a policy.

In the end, justifying the nuclear weapons production industry is shaky because the justification for the weapons themselves is shaky, resting on assertion and Cold War momentum – as Gates’ speech illustrated – more than on rigorous assessments of missions and the security of the nation.

The Secretary’s speech was a disappointing missed opportunity. We are a bit perplexed about why he gave it and gave it now. Perhaps he is putting down a marker for a debate he expects in the next administration and Congress. We welcome that debate because we believe that, with careful attention to definition and no hidden assumptions, the arguments for nuclear weapons fade away.

White House Guidance Led to New Nuclear Strike Plans Against Proliferators, Document Shows

By Hans M. Kristensen

The 2001 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) and White House guidance issued in response to the terrorist attacks against the United States in September 2001 led to the creation of new nuclear strike options against regional states seeking to acquire weapons of mass destruction, according to a military planning document obtained by the Federation of American Scientists.

Rumors about such options have existed for years, but the document is the first authoritative evidence that fear of weapons of mass destruction attacks from outside Russia and China caused the Bush administration to broaden U.S. nuclear targeting policy by ordering the military to prepare a series of new options for nuclear strikes against regional proliferators.

Responding to nuclear weapons planning guidance issued by the White House shortly after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, U.S. Strategic Command created a series of scenario driven nuclear strike options against regional states. Illustrations in the document identify the states as North Korea and Libya as well as SCUD-equipped countries that appear to include Iran, Iraq (at the time), and Syria – the very countries mentioned in the NPR. The new strike options were incorporated into the strategic nuclear war plan that entered into effect on March 1, 2003.

The creation of the new strike options contradict statements by government officials who have insisted that the NPR did not change U.S. nuclear policy but decreased the role of nuclear weapons.

Non-Denial Denials and a Few Hints

When portions of the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) were leaked in the Los Angeles Times in March 2002, government officials responded by playing down the importance of the document and its effect on nuclear planning. And officials have since continue to credit the NPR with reducing the reliance on nuclear weapons.

The NPR is “not a plan, it’s not an operational plan,” then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Richard B. Myers insisted on CNN the day after the NPR was leaked. “It’s a policy document. And it simply states our deterrence posture, of which nuclear weapons are a part….And it’s been the policy of this country for a long time, as long as I’ve been a senior officer, that the president would always reserve the right up to and including the use of nuclear weapons if that was appropriate. So that continues to be the policy.”

A formal statement published by the Department of Defense added that the NPR “does not provide operational guidance on nuclear targeting or planning,” but that the military simply “continues to plan for a broad range of contingencies and unforeseen threats to the United States and its allies.”

Most recently, on October 9, 2007, Christina Rocca, the U.S. permanent representative to the Conference on Disarmament, told the First Committee of the U.N. General Assembly that the United States has been “reducing the…degree of reliance on [nuclear] weapons in national security strategies….It was precisely the new thinking embodied in the NPR that allowed for the historic reductions we are continuing today.”

Yet a few officials hinted in 2002 that the same guidance expanded nuclear planning. “There are nations out there developing weapons of mass destruction,” then Secretary of State Colin Powell said on CBS’ Face the Nation. “Prudent planners have to give some consideration as to the range of options the president should have available to him to deal with these kinds of threat,” he said.

The declassified U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) document shows that one of the first results of “the new thinking” of the NPR was the creation of a series of new nuclear strike options against regional states.

A Series of Regional Options

The 26-page declassified document, an excerpt from a 123-page STRATCOM briefing on the production of the 2003 strategic nuclear war plan known as OPLAN 8044 Revision 03, includes two slides that describe the planning against “regional states.” The first of these slides lists a “series of [deleted] options” directed against regional countries with weapons of mass destruction programs. The planning is “scenario driven,” according to the document. The majority of the document deals with targeting of Russia and China, but virtually all of those sections were withheld by the declassification officer.

The names of the “regional states” were also withheld, but three images used to illustrate the planning were released, and they leave little doubt who the regional states are: One of the images is the North Korean Taepo Dong 1 missile; another image shows the Libyan underground facility at Tarhuna; and the third image shows a SCUD B short-range ballistic missile. The SCUD B image is not country-specific, but the Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center report Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat from 2003 listed 12 countries with SCUD B missiles: Belarus, Bulgaria, Egypt, Iran, Kazakhstan, Libya, North Korea, Syria, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Vietnam and Yemen. Five of these were listed in the NPR as examples of countries that were “immediate, potential, or unexpected contingencies…setting requirements for nuclear strike capabilities”: Iran, Iraq, Libya, North Korea and Syria.

|

|

Images included in the declassified STRATCOM document identify several regional states as targets for new nuclear strike plans. |

The inclusion of regional nuclear counterproliferaiton strike options into the national (strategic) war plan is a new development because such scenarios have normally been thought to reside at a lower level than the national strategic plan, which has traditionally been focused on targeting of Russia and China. During the 1990s, STRATCOM developed adaptive planning capabilities that enabled quick production of strikes against “rogue” states if necessary, but “there were no immediate plans on the shelf for target packages to give to bombers or missile crews,” a former senior Pentagon official told Washington Post in 2002. OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 changed that by producing executable strike options to the nuclear forces.

The “target base” for the regional states is outlined in the STRATCOM document, but everything except the title has been withheld. But the target base probably included weapons of mass destruction, deep, hardened bunkers containing chemical or biological weapons, or the command and control infrastructure required for the states to execute a WMD attack against the United States or its friends and allies. The U.S. Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy (NUWEP) that entered into effect one year after OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 stated in part: “U.S. nuclear forces must be capable of, and be seen to be capable of, destroying those critical war-making and war-supporting assets and capabilities that a potential enemy leadership values most and that it would rely on to achieve its own objectives in a post-war world.”

The creation of a “target base” indicates that the planning went further than simple retaliatory punishment with one or a few weapons, but envisioned actual nuclear warfighting intended to annihilate a wide range of facilities in order to deprive the states the ability to launch and fight with WMD. The new plan formally broadened strategic nuclear targeting from two adversaries (Russia and China) to a total of seven.

Iraq presumably disappeared from the war plan again after U.S. forces invaded the country in March 2003 – only three weeks after OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 went into effect – and discovered that Iraq did not have weapons of mass destruction. Libya presumably disappeared after December 2003, when President Muammar Gaddafi declared that he was giving up efforts to develop weapons of mass destruction.

The nuclear strike plans against Iran, North Korea and Syria, however, presumably were carried forward into the next OPLAN 8044 Revision 05 from October 2004, a plan that was still in effect as recently as July 2007.

|

Nuclear Guidance |

|

|

|

|

| “The 2001 Nuclear Posture Review (top) and White House guidance led to an expansion of U.S. nuclear targeting plans. |

New Guidance for the Regions

The STRATCOM document indicates that National Security Presidential Directive (NSPD)-14 signed by President Bush on June 28, 2002, was the key While House guidance that resulted in the incorporation into the strategic nuclear war plan of strike options against regional proliferators.

Very little has been disclosed about NSPD-14, except that it laid out Presidential nuclear weapons planning guidance and provided broad overarching directions to the agencies and commands for nuclear weapon planning. As such, NSPD-14 might have been replacing Presidential Decision Directive (PDD)-60 signed by President Clinton in November 1997 as the primary White House guidance for nuclear weapons planning. PDD-60 reportedly also required planning against proliferators, but the new strike options incorporated into Revision 03 were “notable changes” compared with the previous plan, according to the STRATCOM document.

Flowing from NSPD-14 were several other important guidance documents that deepened the commitment to targeting regional proliferators. The first was the JSCP Transitional Guidance in June 2002, which directed changes to the Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan (JSCP). JSCP includes a nuclear annex or supplement, known as JSCP-N, that give detailed nuclear planning guidance to the unified and regional commanders. The new JSCP-N was published on October 1, 2002. Another document was the NUWEP (Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy) Transitional Guidance signed on August 29, 2002, which led to the publication of NUWEP-04 in April 2004.

Three months after NSPD-14, on September 14, 2002, President Bush also signed NSPD-17 (National Strategy to Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction), a directive that articulated a comprehensive strategy to counter nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction. NSPD-17 reaffirmed that, if necessary, the United States will use nuclear weapons against anyone using weapons of mass destruction against the United States, its forces abroad, and friends and allies, according to Washington Times. But a top-secret appendix to NSPD 17 specifically named Iran, Syria, North Korea and Libya as being among the countries that are the central focus of the new strategy, and that options included nuclear weapons. Those options were in place with OPLAN 8044 Revision 03. The motivation for the new strategy, one participant in the interagency process that drafted it told Washington Post, was the conclusion that “traditional nonproliferation has failed, and now we’re going into active interdiction.” NSPD-17 is sometimes also called the preemption doctrine.

The regional strike plans also found their way into the draft Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations (Joint Publication 3-12), which was under preparation within the military at the time Revision 03 was created. Yet the doctrine showed that planning went beyond retaliation and included preemptive strikes. The second draft from March 2005 listed five scenarios where use of nuclear weapons might be requested:

• To counter an adversary intending to use weapons of mass destruction against U.S., multinational, or allies forces or civilian populations;

• To counter an imminent attack from an adversary’s biological weapons that only effects from nuclear weapons can safely destroy;

• To attack on adversary installations including weapons of mass destruction, deep, hardened bunkers containing chemical or biological weapons, or the command and control infrastructure required for the adversary to execute a WMD attack against the United States or its friends and allies; [this was probably the “target base” in OPLAN 8044 Revision 03]

• To counter potentially overwhelming adversary conventional forces;

• To demonstrate U.S. intent and capability to use nuclear weapons to deter adversary WMD use.

After I disclosed this development in an article in Arms Control Today in September 2005 and the Washington Post followed up with a front-page story, sixteen members of Congress – including the current chair of the House Armed Services Committee – reacted by writing to the president to object to what they considered to be a “drastic shift in U.S. nuclear policy.”

Embarrassed by the exposure, the Pentagon canceled not only the draft doctrine (and four other related doctrine documents) but also the existing Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations document that had been publicly available on the Joint Chiefs of Staff web site for a decade. A Joint Staff official explained that the documents would not be published, revised or classified, explaining that that they had been found not to be real doctrine documents but “pseudo doctrine” documents discussing nuclear policy issues. The public “visibility led a lot of people to question why we have them,” he said.

|

|

|

|

During the tenure of Admiral Ellis (right), STRATCOM prepared, and CJCS Richard Myers (left) approved, an expansion of the SIOP to “a family of plans applicable in a wider range of scenarios.” |

From SIOP to OPLAN 8044: A “Family of Plans”

There is no indication that cancelation of the Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations documents changed nuclear policy. The declassified STRATCOM document describes OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 as “a transitional step toward the new TRIAD and future war plans.” That transition began long before the “New Triad” phrase was coined by the 2001 NPR, and has gradually transformed the top-heavy self-standing Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP) to a broader set of strike options applicable in a wider range of scenarios against more adversaries. When preparation of Revision 03 began in March 2002, the combat employment portion of the strategic nuclear war plan was still known as the SIOP, but the name had to be changed to reflect the emerging multitude of strike options.

As the Joint Staff started to review the new war plan, STRATCOM commander Admiral James Ellis wrote to General Myers that the name SIOP did not properly describe the new plan. “STRATCOM is changing the nation’s nuclear war plan from a single, large, integrated plan to a family of plans applicable in a wider range of scenarios,” Ellis explained with a reference to Revision 03. The first STRATCOM commander, General George Lee Butler, had tried to change the name in 1992, but with no luck. Butler wanted to change the name to National Strategic Response Plans. Eleven years later, Admiral Ellis tried again. The SIOP name, he said, was a Cold War legacy.

This time, the JCS chairman was more receptive. On February 8, 2003, only one month before Revision 03 went into effect, General Myers authorized STRATCOM to formally change the name to reflect the creation the “new family of plans.” Yet Myers was concerned that confusion might arise “between the basic USSTRATCOM OPLAN 8044 and the combat employment portion of that OPLAN, currently known as the SIOP.” The solution, he decided, was to continue to call the basic plan OPLAN 8044, but incorporate the term OPLAN 8044 Revision (FY) to describe that portion of the plan currently known as the SIOP. The Revision number (FY) would correspond to the fiscal year the combat employment plan was put into effect. OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 of March 1, 2003, was the first plan to carry the new name.

The new strike options apparently were carried forward into OPLAN 8044 Revision 05, the next strategic war plan that entered into effect on October 1, 2004. This plan was described as a “major revamping” of the U.S. strategic war plan, which, according to General Myers, “provides more flexible options to assure allies, and dissuade, deter, and if necessary, defeat adversaries in a wider range of contingencies.” OPLAN 8044 Revision 05 was still in effect as of July 2007 (for a chronology of U.S. nuclear guidance and war plans under the Bush administration, go here).

Claims About Reducing Reliance On Nuclear Weapons

Officials frequently credit the NPR with having significantly reduced the reliance on nuclear weapons in U.S. nuclear policy. The basis for this claim is that non-nuclear capabilities also should play a role in deterring potential adversaries, an goal exemplified by the incorporation of conventional strike options into OPLAN 8044 Revision 05, the war plan than followed OPLAN 8044 Revision 03, and the removal of Russia as an “immediate contingency.”

“The United States has set in motion an entirely new way of looking at the role of nuclear weapons in our defense strategy,” Jackie W. Sanders, U.S. Ambassador and Special Representative of the President for the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, told the 2005 Nonproliferation Treaty Review Conference. “I speak, Mr. Chairman, of the U.S. Nuclear Posture Review, or NPR, of 2001. The United States has undertaken reviews of this sort in the past, but the 2001 NPR is unique, and fully consistent with Article VI. The 2001 NPR established a New Triad of strategic capabilities, one that places far less reliance on nuclear weapons to meet U.S. defense policy goals…. Let me emphasize, Mr. Chairman, that the New Triad concept resulting from the NPR, in principle and in practice, will reduce reliance on nuclear weapons in U.S. national security strategy. It reflects a totally new vision of the future, and is fully consistent with our indisputable resolve to implement Article VI.”

But while some conventional weapons are being incorporated into the national war plan and planning against Russia is not done in the same way it was during the Cold War, the NPR (building on the 1997 PDD-60) and White House guidance also resulted in an increased nuclear targeting of China and, as the declassified STRATCOM document illustrates, an geographic expansion of national-level nuclear targeting to regional proliferators. Prudent or not, this is not a development that is highlighted by U.S. diplomats at NPT conferences.

Description of Document

The declassified document is heavily redacted and consists of 26 of a total of 123 slides from the Revision 03 Periodic Update of the U.S. strategic war plan that went into effect on March 1, 2003. The plan was the first strategic war plan to carry the new name Operations Plan (OPLAN) 8044 Revision 03, which replaced the Single Operational Strategic Plan (SIOP) name used since 1960. OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 replaced SIOP-03 from October 1, 2002.

The document describes six parts of the new plan preparation: Revision 03 production status, planning guidance, target base, committed forces, options, and conclusions.

The document is not dated, but appears to be from October 2002, shortly before the Secretary of Defense was briefed. Targeting intelligence and selection had been completed, warheads allocated to the strike plans, and strike (sortie) planning for Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs), Sea-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs), and long-range bombers nearly completed. After a Joint Staff review and production of the final Revision Report 03 in January 2003, final Defense Secretary review and approval by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff were scheduled for late January 2003 before OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 went into effect on March 1, 2003.

Declassification of the document took four years. It was released in response to a FOIA request submitted in October 2003 for documents pursuant to remarks made by then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Richard Myers during a Senate Foreign Relations Committee Hearing in July 2002. When asked if there had been a review of the SIOP since the mid-1990s, Myers replied: “Yes, there absolutely has. In fact, the secretary and I spent considerable time revising the SIOP. I think we started that last year and have gotten another major review ongoing.” The declassified document was released on October 10, 2007.

Resources: U.S. Nuclear Weapons Guidance | The Matrix of Deterrence | The Post Cold War SIOP and Nuclear Warfare Planning: A Glossary, Abbreviations, and Acronyms

Acknowledgements: This research has been made possible by support from the Ford Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund.

Reaffirming the Nuclear Umbrella: Nuclear Policy on Autopilot

In condemning the North Korean nuclear test and repeating its call for a denuclearized Korean Peninsula, one of the Bush administration’s first acts ironically has been to reaffirm the importance of nuclear weapons in the region.

In condemning the North Korean nuclear test and repeating its call for a denuclearized Korean Peninsula, one of the Bush administration’s first acts ironically has been to reaffirm the importance of nuclear weapons in the region.

“The United States will meet the full range of our deterrent and security commitments,” President Bush told Japan and South Korea after last week’s test. On Wednesday, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice strongly hinted that the commitments potentially include nuclear strikes against North Korea.

But is it helpful or counterproductive at this stage to threaten North Korea with nuclear weapons?

(more…)

US Says North Korean Test Was Nuclear

In an extraordinarily brief statement, the Director of the National Intelligence Office announced that the United States has confirmed that North Korea’s large explosion last week was nuclear. How do they know and why did it take them so long to confirm?

(more…)

North Korea’s Bomb: A technical assessment [edited 16 October]

Last Sunday, North Korea apparently tested a nuclear explosive. The “apparently” is needed because the explosion was so small—by nuclear standards—that some have speculated that it may have been a large conventional explosion. What is the technical significance of the test, what does it mean, and what should we do now?

There is no question that the political and security implications of the test are huge and almost entirely negative. The technical implications are more mixed; the technical significance of the test is somewhat less than meets the eye.

(more…)

Article: Nuclear Threats Then And Now

A decision to trim a tree in the Korean demilitarized zone in 1976 escalated into a threat to use nuclear weapons. After a fatal skirmish between U.S. and North Korean border guards, U.S. forces in the region were placed on heightened alert (DEFCON 3) and nuclear forces were deployed to signal preparations for an attack on North Korea. The North Koreans did not interfere with the tree trimming again, so the threat must have worked, the Pentagon concluded.

Thirty years later, North Korea has probably developed nuclear weapons and is trying to develop long-range ballistic missiles to threaten you-know-who, and the United States has ventured into a multi-billion dollar effort to build a missile defense system and a “New Triad” to better dissuade, deter, and defeat North Korea and other “rogue” states.

So, did the threat work?

The “tree-trimming incident,” as the U.S.-North Korean scuffle has come to be known, and other examples of using nuclear threats are described in the article “Nuclear Threats Then And Now” in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.