Estimated Nuclear Weapons Locations 2009

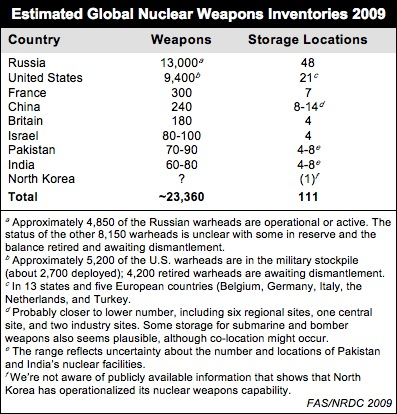

Some 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at 111 locations around the world

.The world’s approximately 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at an estimated 111 locations in 14 countries, according to an overview produced by FAS and NRDC.

Nearly half of the weapons are operationally deployed with delivery systems capable of launching on short notice.

The overview is published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and includes the July 2009 START memorandum of understanding data. A previous version was included in the annual report from the International Panel of Fissile Materials published last month.

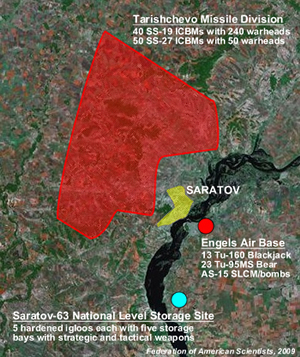

More than 1,000 nuclear weapons surround Saratov.

Russia has an estimated 48 permanent nuclear weapon storage sites, of which more than half are on bases for operational forces. There are approximately 19 storage sites, of which about half are national-level storage facilities. In addition, a significant number of temporary storage sites occasionally store nuclear weapons in transit between facilities.

This is a significant consolidation from the estimated 90 Russian sites ten years ago, and more than 500 sites before 1991.

Many of the Russian sites are in close proximity to each other and large populated areas. One example is the Saratov area where the city is surrounded by a missile division, a strategic bomber base, and a national-level storage site with probably well over 1,000 nuclear warheads combined (Figure 2).

The United States stores its nuclear weapons at 21 locations in 13 states and five European countries. This is a consolidation from the estimated 24 sites ten year ago, 50 at the end of the Cold War, and 164 in 1985 (see Figure 3).

Approximately 50 B61 nuclear bombs inside an igloo at what might be Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada. Seventy-five igloos at Nellis store “one of the largest stockpile in the free world,” according to the U.S. Air Force, one of four central storage sites in the United States.

Europe has about the same number of nuclear weapon storage locations as the Continental United States, with weapons scattered across seven countries. This includes seven sites in France and four in Britain. Five non-nuclear NATO countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey) still host U.S. nuclear weapons first deployed there during the Cold War.

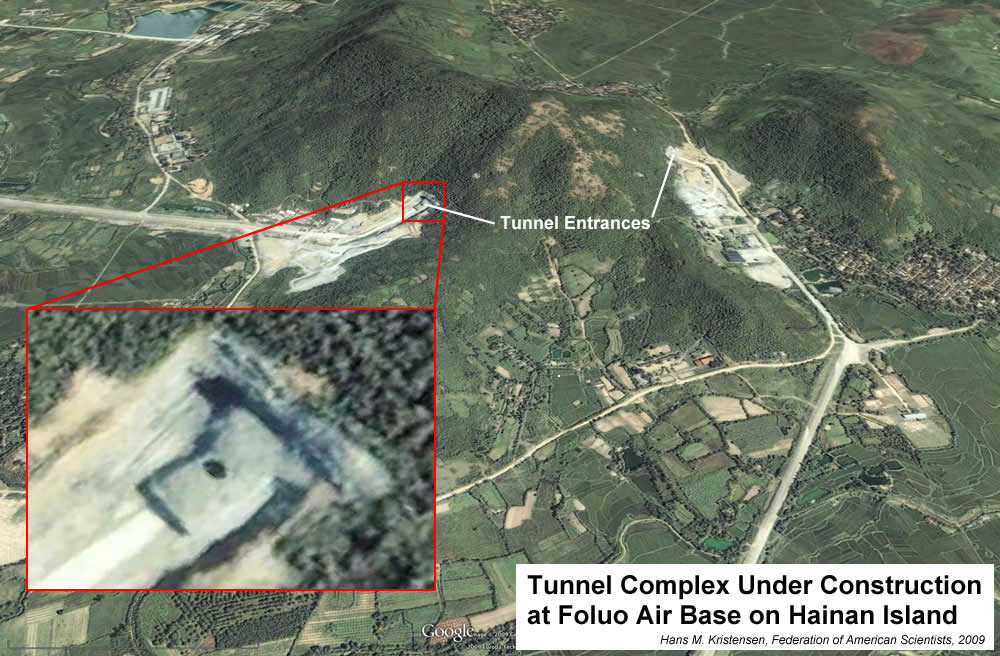

We estimate that China has 8-14 facilities associated with nuclear weapons, most likely closer to the lower number, near bases with units that operate nuclear missiles or aircraft. None of the weapons are believed to be fully operational but stored separate from delivery vehicles at sites controlled by the Central Military Commission.

Where does China store nuclear warheads for its ballistic missile submarines? The naval base near Julin on Hainan Island has extensive underground facilities. An alternative to the base itself could potentially be a facility elsewhere on the island, such as Foluo Air Base where construction of an underground facility began five years before the first SSBN arrived at Hainan. Or are the weapons stored on the mainland? Click image to enlarge.

Israel probably has about four nuclear sites, whereas the nuclear storage facilities in India and Pakistan are – despite many rumors – largely undetermined. All three countries are thought to store warheads separate from delivery vehicles.

Despite two nuclear tests and many rumors, we are unaware of publicly available evidence that North Korea has operationalized its nuclear weapons capability.

Warhead concentrations vary greatly from country to country. With 13,000 warheads at 48 sites, Russian stores an average of 270 warheads at each location. The U.S. concentration is much higher with an average of 450 warheads at each location. These are averages, however, and in reality the distribution is thought to be much more uneven with some sites only storing tens of warheads.

Finally, a word of caution is in order: estimates such as these obviously come with a great deal of uncertainty, as we don’t have access to classified intelligence estimates. Based on publicly available information and our own assumptions we have nonetheless produced a best estimate that we hope will assist the public debate. Comments and suggestions are encouraged so we can adjust the overview in the future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Germany and NATO’s Nuclear Dilemma

|

| Security personnel monitor nuclear weapons transport at German air base. Image: USAF |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The new German government has announced that it wants to enter talks with its NATO allies about the withdrawal of the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Germany.

The announcement coincides with the Obama administration’s ongoing Nuclear Posture Review, which is spending an unprecedented amount of time pondering the “international aspects” of to what extent nuclear weapons help assure allies of their security.

Germany and many other NATO countries apparently don’t want to be protected by U.S. forward-deployed tactical nuclear weapons, which they see as a relic of the Cold War that locks NATO in the past and prevents it’s transition to the future.

Current Deployment

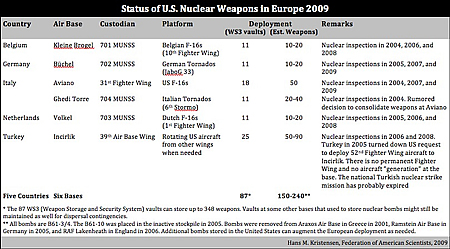

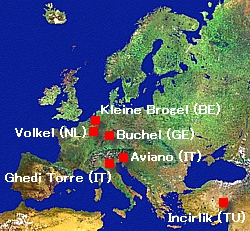

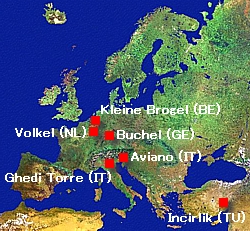

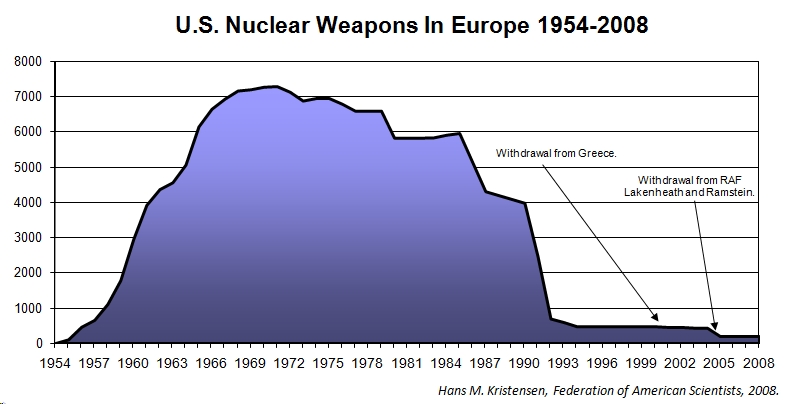

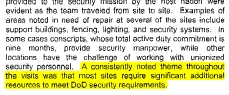

The U.S. Air Force currently deploys approximately 200 B61 nuclear bombs at six bases in five NATO countries (see Table 1). The weapons are the last remnant of a vast force of more than 7,000 tactical nuclear weapons that used to clutter bases in Europe during the Cold War as a defense against the Soviet threat and the Warsaw Pact’s large conventional forces.

|

Table 1: |

|

| Approximately 200 U.S. nuclear bombs are currently deployed at six bases in five European countries. Click image to download larger table. |

.

The bombs are scattered among 87 individual aircraft shelters where they are stored in underground vaults. Although well protected, this widespread deployment contrasts normal U.S. nuclear weapons security procedures that favor consolidation at as few locations as possible.

An Air Force investigation concluded in 2008 that “most” sites in Europe did not meet U.S. security requirements. NATO officials publicly dismissed the conclusion, and a visit by a team from the U.S. government apparently found issues but nothing alarming.

Consolidation Versus Withdrawal

Rumors have circulated for several years about plans to consolidate the remaining weapons from the current six bases to one or two bases. The plans would either terminate the Cold War arrangement of non-nuclear NATO countries being assigned strike missions with U.S. nuclear weapons, or move the weapons to U.S. bases with the promise that they could be returned if necessary.

Consolidation has occurred frequently since the end of the Cold War: withdrawal from Turkish national bases Akinci and Balikesir in 1995; withdrawal from German national bases Memmingen and Norvenich in 1996; withdrawal from Greek national base Araxos in 2001; withdrawal from Ramstein in Germany in 2005 ; withdrawal from Lakenheath in England in 2006. Another round of consolidation would just be another slow step toward the inevitable: withdrawal from Europe.

Consolidation of the remaining nuclear bombs to the two U.S. southern bases at Aviano in Italy and Incirlik in Turkey would be problematic for two reasons. First, Turkey does not allow the U.S. Air Force to deploy the fighter-bombers to Incirlik that are needed to deliver the bombs if necessary, and has several times restricted U.S. deployments through Turkey into Iraq. Given that history, and apparent doubts about Turkey’s future direction, is nuclear deployment in Turkey a credible posture? Second, absent a fighter wing deployment to Incirlik, Aviano carries the overwhelming burden of conventional air operations on the southern flank of NATO, operations that are already burdened by the nuclear addendum and would further be so by a decision to consolidate the nuclear mission at the base.

An End to NATO Nuclear Strike Mission

The German policy to seek withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Büchel Air Base essentially means – if implemented – the unraveling of the NATO nuclear strike mission, whereby non-nuclear NATO countries equip and train their air forces to deliver U.S. nuclear weapons. Germany shares this mission with Belgium, Italy, and the Netherlands, while Greece and Turkey opted out in 2001.

|

Table 1: |

|

| German personnel attach a U.S. B61 nuclear bomb shape to a German Tornado fighter-bomber under supervision of U.S. personnel. As a signatory to the NPT Germany has pledged not to receive nuclear weapons, yet, as this picture illustrates, is preparing its military to do so anyway. Image: German Ministry of Defense/Der Spiegel |

.

The mission is highly controversial because these countries as signatories to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) have all pledged not to receive nuclear weapons: “undertakes not to receive the transfer from any transferor whatsoever of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices or of control over such weapons or explosive devices directly, or indirectly.” Yet that’s precisely what the NATO strike mission entails: peacetime preparations for direct transfer of nuclear weapons and control over such weapons in times of war.

The mission is clearly inconsistent with if not the letter then certainly the spirit of the NPT. The arrangement was tolerated during the Cold War but is incompatible with nonproliferation policy is the 21st century.

Real-World Security Commitments

Germany is one of the “30-plus” allies and friends that some have argued recently need to be protected by nuclear weapons to prevent them from developing their own nuclear weapons. It has even been suggested that extended deterrence necessitates equipping the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter with nuclear capability.

Yet high-level officials in both the White House and the Pentagon have already concluded that the United States no longer needs to deploy nuclear bombs in Europe to meet its security obligations to NATO. Those security obligations today have very little to do with nuclear weapons and extended deterrence is predominantly served by non-nuclear means. The limited role nuclear weapons still serve can adequately be fulfilled by long-range weapon systems just as they have been in the Pacific for 17 years. Whether the ongoing Nuclear Posture Review will reflect those views will be seen in February 2010 when the review is completed.

|

Figure 2: |

|

| The U.S. nuclear bombs were deployed in Europe to defend NATO against a conventional attack from the Warsaw Pact, a threat that has long-since disappeared. |

Regardless, Germany apparently does not want to be protected by U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe. Neither does Belgium, where the parliament unanimously has requested nuclear bombs be withdrawn. Dutch officials privately say that they see no need for the deployment either. In fact, in all of the countries where nuclear weapons are deployed, an overwhelming majority of the public favors withdrawal. Turkey – one of the countries said by some to oppose withdrawal – has the highest public support for withdrawal of any of the countries that currently store nuclear weapons. In the long run this is a serious challenges for NATO; that its nuclear posture is so clearly out of sync with public opinion.

The biggest challenge seems to be to convince Poland and Turkey that withdrawal will not undermine the U.S. security commitment. Poland is worried about Russia; Turkey about Iran. But tactical nuclear weapons were the Cold War way of addressing such concerns. What’s needed now is focused diplomacy, stewardship, and reaffirmation of non-nuclear arrangements to convince these countries that the nuclear bombs that were deployed in Europe to defend NATO against a conventional attack from the Warsaw Pact can now finally be withdrawn.

The previous two German governments also favored withdrawal but did little to push the issue. Whether the new government will be any different will be put to the test during NATO’s ongoing revision of its Strategic Concept scheduled for completion in 2010.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Russian Tactical Nuclear Weapons

|

| New low-yield nuclear warheads for cruise missiles on Russia’s submarines?. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Two recent news reports have drawn the attention to Russia’s tactical nuclear weapons. Earlier this week, RIA Novosti quoted Vice Admiral Oleg Burtsev, deputy head of the Russian Navy General Staff, saying that the role of tactical nuclear weapons on submarines “will play a key role in the future,” that their range and precision are gradually increasing, and that Russia “can install low-yield warheads on existing cruise missiles” with high-yield warheads.

This morning an editorial in the New York Times advocated withdrawing the “200 to 300” U.S. tactical nuclear bombs deployed in Europe “to make it much easier to challenge Russia to reduce its stockpile of at least 3,000 short-range weapons.”

Both reports compel – each in their own way – the Obama administration to address the issue of tactical nuclear weapons.

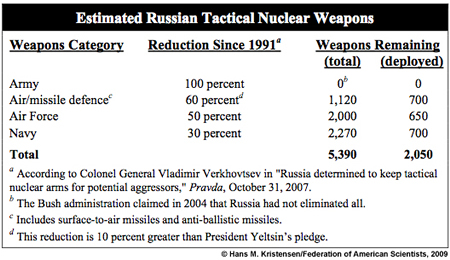

The Russian Inventory

Like the United States, Russia doesn’t say much about the status of its tactical nuclear weapons. The little we have to go by is based on what the Soviet Union used to have and how much Russian officials have said they have cut since then.

Unofficial estimates set the Soviet inventory of tactical nuclear weapons at roughly 15,000 in mid-1991. In response to unilateral cuts announced by the United States in late 1991 and early 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin pledged in 1992 that production of warheads for ground-launched tactical missiles, artillery shells, and mines had stopped and that all such warheads would be eliminated. He also pledged that Russia would dispose of half of all airborne and surface-to-air warheads, as well as one-third of all naval warheads.

In 2004, the Russian Foreign Ministry stated that “more than 50 percent” of these warhead types have been “liquidated.” And in September 2007, Defense Ministry official Colonel-General Vladimir Verkhovtsev gave a status report of these reductions that appeared to go beyond President Yeltsin’s pledge.

Based on this, Robert Norris and I make the following cautious estimate (to be published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in late April) of the current Russian inventory of tactical nuclear weapons:

|

| Estimate from forthcoming Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. |

.

Based on the number of available nuclear-capable delivery platforms, we estimate that nearly two-thirds of these warheads are in reserve or awaiting dismantlement. The remaining approximately 2,080 warheads are operational for delivery by anti-ballistic missiles, air-defence missiles, tactical aircraft, and naval cruise missiles, depth bombs, and torpedoes. The Navy’s tactical nuclear weapons are not deployed at sea under normal circumstances but stored on land.

The Other Nuclear Powers

The United States retains a small inventory of perhaps 500 active tactical nuclear weapons. This includes an estimated 400 bombs (including 200 in Europe) and 100 Tomahawk cruise missiles (all on land). Others, perhaps 700, are in inactive storage.

France also has 60 tactical-range cruise missiles, including some on its aircraft carrier, although it calls them strategic weapons.

The United Kingdom has completely eliminated its tactical nuclear weapons, although it said until a couple of years ago that some of its strategic Trident missiles had a “sub-strategic” mission.

Information about possible Chinese tactical nuclear weapons is vague and contradictory, but might include some gravity bombs.

India, Pakistan, and Israel have some nuclear weapons that could be considered tactical (gravity bombs for fighter-bombers and, in the case of India and Pakistan, short-range ballistic missiles), but all are normally considered strategic.

| Russian Nuclear-Capable Cruise Missile Launch |

|

| A nuclear-capable SS-N-19 Shipwreck cruise missile is launched from a Kirov-class nuclear-powered guided missile cruiser. The ship is equipped with 20 launchers for the SS-N-19 missile, which can carry a 500-kiloton warhead. Other tactical nuclear weapon systems include the SS-N-16 anti-submarine rocket, and the SA-N-6 anti-air missile. |

.

Implications and Issues

Whether Vice Admiral Burtsev’s statement is more than boasting remains to be seen, but it is a timely reminder to the Obama administration of the need to develop a plan for how to tackle the tactical nuclear weapons.

Russia’s nuclear posture is now approaching a situation where there are more tactical nuclear weapons in the inventory than strategic weapons. And NATO’s remnant of the Cold War tactical nuclear posture in Europe seems stuck in the mud of nuclear dogma and bureaucratic inaction.

None of these tactical nuclear weapons are limited or monitored by any arms control agreements, and – for all the worries about terrorists stealing nuclear weapons – are the most easy to run away with.

In April, NATO is widely expected to kick off a (long-overdue) review of its Strategic Concept from 1999. It would be a mistake to leave the initiative on what to do with the tactical nuclear weapons to the NATO bureaucrats. The vision must come from the top and President Obama needs to articulate what it is soon.

The Minot Investigations: From Fixing Problems to Nuclear Advocacy

|

| The second report from the Schlesinger Task Force goes beyond fixing nuclear problems to promoting new nuclear weapons. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

For nuclear weapon advocates, the Minot incident in August 2007, where the Air Force lost track of six nuclear-armed cruise missiles for 36 hours, was a gift sent from heaven. No other event short of a nuclear attack against the United States could have provided a better opportunity to breathe new life into the declining nuclear mission.

But where is the line between fixing problems and advocacy?

Although the latest report from the Secretary of Defense Task Force on DOD Nuclear Weapons Management, also known as the Schlesinger report, contains many reasonable recommendations to ensure that the Services and agencies are capable of fulfilling the nuclear mission, it is also sprinkled with recommendations that have more to do with promoting nuclear weapons.

And it makes some remarkable claims about the deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe.

Fuzzy Tasking Leads to Fuzzy Focus

The leap from investigation to promotion is an unfortunate byproduct of the tasking Defense Secretary Robert Gates provided to the Schlesinger Task Force in June 2008. That letter not only directed the task force to examine accountability and control procedures for nuclear weapons to “sustain public confidence in the safe handling of DoD nuclear assets,” but also to “bolster a clear international understanding of the continued role and credibility of the U.S. nuclear deterrent.”

The task force appears to have taken the second objective a bit far.

Rather than being focused on fixing the problems that resulted in the Minot incident and several other events, the report reads like a second volume of the Defense Science Board (DSB) report from 2006 in which disgruntled nuclear advocates lamented a decline in support for the nuclear mission.

The Schlesinger report is, at times, a phenomenal concoction of Cold War nuclear jargon and claims made without presenting any evidence or analysis to support their continued validity. The report skips over the expansion from deterring nuclear to deterring all forms of WMD (it doesn’t even list the difference), and it suggests that U.S. nuclear weapons even have a mission against “violent extremists and nonstate actors.”

Nuclear Promotions

Anticipating that some elements of the nuclear posture will probably be cut in the future as a result of the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission, the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, and an potential arms control agreement with Russia, the Schlesinger report correctly states that such cuts “should be a reflection of policy decisions at the highest level rather than a result of Service preferences or budgetary concerns.” Given this conclusion, it is all the more noteworthy how the Schlesinger report throws itself into a blunt advocacy of nuclear posture issues that clearly should be the purview of the next administration.

Examples of posture recommendations that go beyond “accountability and control procedures” to promotion of new nuclear weapons include:

* Develop follow-on capabilities that can come online prior to expiration of the nuclear Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM-N) effectiveness or, should there be a gap, extend the TLAM-N service life commensurate with introduction of the new system.

* The Secretary of Defense should direct the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to develop validated operational requirements for modernizing or replacing the capabilities now provided by Dual-Capable Aircraft (DCA), Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM), and TLAM-N.

* Review and update the concept of operations for the TLAM-N to make it a more viable and responsive option for national leadership.

Clearly, these appear to be future posture decisions that are beyond the job the Schlesinger Task Force was asked to do.

The Extended Deterrence Confusion

The TLAM and DCA are weapons that are weapon systems that are both have roles in the extended deterrence mission. Yet the authors of the Schlesinger report repeatedly confuse the description of what extended deterrence means. Sometime they describe it as forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. At other times they describe as a nuclear umbrella extended over allies from afar.

For example, in the opening paragraphs of the section called “The Special Case of NATO,” the report concludes: “As long as NATO members rely on U.S. nuclear weapons for deterrence, no action should be taken to remove them without a thorough and deliberate process of consultation.”

Certainly NATO members should be consulted, but withdrawing “them” (which refers to the roughly 200 tactical nuclear bombs deployed in five European countries) hardly constitutes eliminating the entire U.S. nuclear weapons deterrent. A withdrawal from Europe would not be the end of the nuclear umbrella, as the Schlesinger report indicates, which could be continued by long-range forces just like it was in the Pacific after tactical nuclear weapons were withdrawn from South Korea in 1991.

|

Figure 1: |

|

|

About 200 U.S. tactical nuclear weapons are deployed at six bases in five European countries. After the Blue Ribbon Review report in 2008 concluded that it would take considerable additional resources for security at European nuclear sites to meet DOD standards, the Schlesinger report now concludes that everything is fine. |

The Deployment in Europe

One of the most interesting parts of the report concerns the deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. Unfortunately, the European section is filled with sweeping statements and conclusions about the virtues of the deployment that are not supported by any accompanying analysis except deterrence jargon and echoes from the Cold War:

“Much of the deterrent value of NATO’s DCA deployment is derived from their in-theater presence, demonstrating and maintaining the capability to employ them. This creates in the minds of potential aggressors an unacceptable level of uncertainty concerning the success of any contemplated attack on NATO. This deterrent effect cannot be created by simply having nuclear weapons stored and locked up or relying exclusively on “over-the-horizon” nuclear delivery capabilities.”

It is? It does? It cannot? Why?

Many actually do believe – including apparently U.S. European Command (EUCOM) – that the deployment in Europe is not necessary anymore. But the authors of the Schlesinger report do not share that view and they spend a good portion of the report criticizing EUCOM for believing that “deterrence provided by USSTRATCOM’s strategic nuclear capabilities outside of Europe are more cost effective” and that “an ‘over the horizon’ strategic capability is just as credible.”

That assessment sounds pretty sound to me. But instead of accepting EUCOM’s assessment that forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe is not necessary for extended deterrence and a burden on real-world nonnuclear operations, the Schlesinger report brushes aside EUCOM’s “narrow assessment.” It is a much broader issue, the authors’ claim, about Russia, flexible regional nuclear deterrence (although the weapons are not targeted against anyone), and a trans-Atlantic link between Europe and the United States. But as far as the tactical nuclear weapons in Europe are concerned, that link was a Cold War link between a Soviet conventional invasion of Europe and U.S. strategic nuclear weapons, a concept that is getting a little dated. And if the glue in NATO depends on forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons, then I think the alliance is in deeper trouble that people normally think.

Interestingly, one person who shares the view of EUCOM was recently selected to become national security advisor to President-elect Barack Obama: General James L. Jones. When he was the head of EUCOM and Supreme Allied Commander Europe in 2005, the New York Times reported that Jones “has privately told associates that he favors eliminating the American nuclear stockpile in Europe, but has met resistance from some NATO political leaders.”

|

Figure 2: |

|

| Unlike the authors of the Schlesinger report, General (Ret.) James Jones, who is President-elect Obama’s national security advisor and former Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR), reportedly favors a withdrawal of tactical nuclear weapons from Europe. |

.

Shortly before the U.S. in 2005 and 2006 secretly withdrew half of the nuclear weapons from Europe – including all weapons from the United Kingdom, Jones told a Belgian Senate committee: “The reduction will be significant. Good news is on the way.” NATO sources attempted to downplay the issue by claiming Jones had not mentioned nuclear weapons specifically, but the Belgian government later stated for the record that, “the United States has decided to withdraw part of its nuclear arsenal deployed in Europe….” German weekly Der Spiegel followed up by asking “whether German nuclear weapons sites will benefit from Gen. Jones’ ‘good news.’” They did: all weapons were withdrawn from Ramstein Air Base.

The authors also leave out that the European political landscape on the tactical nuclear weapons issue has changed dramatically since the justifications the authors use were concocted. An overwhelming majority of the public today favors a withdrawal, the German government parties favor a withdrawal, and the Belgium Senate has unanimously called for a withdrawal. While ignoring those views, the Schlesinger report instead refers to anonymous allies who allegedly have expressed concern over calls for a unilateral withdrawal.

Who are those allies? From what department in the government bureaucracies did the officials that sent those signals come from? Whenever I mention these “allied concerns” during conversations with European government officials, they always smile because they know quite well that what’s a play here is a small group of nuclear bureaucrats deep within the ministries of defense who are defending their own turf. [There are some hints here; none of them seem to be directly related to the deployment in Europe].

Extended Deterrence as Nonproliferation

Another prominent assertions in the NATO section of the report is that by holding a nuclear umbrella over allied countries – by promising to retaliate with nuclear weapons if they are attacked by nuclear weapons (or weapons of mass destruction, as the authors say) – U.S. nuclear weapons prevent allied countries from developing nuclear weapons themselves. This sure sounds good and is a popular claim, but how widespread is this effect.

The report states that the United States has “extended its nuclear protective umbrella to 30-plus friends and allies.” The countries are not identified, but most of them are known:

NATO (25): Albania, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Turkey.

ANZUS (2): Australia, New Zealand.

Northeast Asia (3): Japan, South Korea, Taiwan .

That’s 30, so who are the remaining -plus countries are that the authors say are covered by the U.S. umbrella? France and the U.K. obviously don’t need it because they have their own nuclear deterrents. So do Israel and India. Are there non-nuclear allies in the Middle East that are under the umbrella?

|

Figure 3: |

|

|

A NATO briefing in 2006 acknowledged serious pressure for a withdrawal of nuclear weapons. Click image to download. |

The Schlesinger report recommends that the views of those 30-plus countries should be included in U.S. nuclear policy guidance documents. That would indeed be interesting, given that many of the countries actually have policies that favor a total withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Europe, elimination of non-strategic nuclear weapons, and total nuclear disarmament – political realities the report completely leave out.

Although all 30-plus are used to underscore the virtue of extended deterrence, how many of them would seriously consider acquiring their own nuclear weapons if things changed? Denmark? Iceland? Lithuania? Luxembourg? Portugal? New Zealand? Seriously! Only a few of the 30 are normally considered potential nuclear weapon proliferators: Germany, Japan, and perhaps South Korea.

It is probably also worth mentioning that two NATO countries – France and the United Kingdom – decided years ago to go nuclear even though the United States had thousands of nuclear weapons deployed to defend them. The report doesn’t mention why the NATO countries would not feel sufficiently protected by British or French nuclear forces in Europe.

The report also doesn’t mention that the United States since the early-1990 has maintained a nuclear umbrella over its allies in Northeast Asia without it requiring forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in those countries. Why is it possible to maintain extended deterrence with long-range nuclear weapons in the Pacific but not in Europe?

Conclusions and Remarks

Obviously the virtues of extended deterrence and the deployment in Europe are a little more nuanced than the Schlesinger report purports. But the central proposition that NATO and extended deterrence will go down the tube if tactical nuclear weapons were withdrawn from Europe seems preposterous.

It asks us to believe that if NATO really were attacked or threatened with nuclear (or, for those who believe nuclear weapons are also needed to deter chemical or biological weapons, WMD), U.S., British, and French ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), land-based missiles (ICBMs), and long-range bombers – along with all of NATO combined conventional military might (which is far more credible as a deterrent) – would sit idle in their bases because the political and military leaders somehow were incapable of reacting.

The decline in nuclear prowess that the Minot investigations have detected hasn’t simply happened because overstretched officers failed to do their job or the nation lost faith in nuclear weapons. It is a symptom, a hint. It has declined because nuclear weapons are no longer center and square to the national security of the United States nor its foreign policy. For sure, nuclear weapons haven’t gone away and there are still many challenges, but there are elements of the nuclear mission that are no longer essential and can and should be reassessed.

But the Minot investigations haven’t done that. Instead they have gone beyond fixing safety and security issues to using the incident to reaffirm status quo and reject change. Hopefully the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission and the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review can do better.

Nuclear Déjà Vu At Carnegie

By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

Only one week before Barack Obama is expected to win the presidential election, Defense Secretary Robert Gates made one last pitch for the Bush administration’s nuclear policy during a speech Tuesday at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

What is the opposite of visionary? Whatever, that’s the word that best describes Mr. Gates’s speech. Had it been delivered in the mid-1990s it would not have sounded out of place. The theme was that the world is the way the world is and, not only is there little to be done about changing the world, our response pretty much has to be more of the same.

Granted, Gates’s job is to implement nuclear policy not change it but, at a time when Russia is rattling its nuclear sabers, China is modernizing its forces, some regional states either have already acquired or are pursuing nuclear weapons, and yet inspired visions of a world free of nuclear weapons are entering the political mainstream, we had hoped for some new ideas. Rather than articulating ways to turn things around, Gates’ core message seemed to be to “hedge” and hunker down for the long haul. And, while his arguments are clearer than most, this speech is yet another example of faulty logic and sloppy definitions justifying unjustifiable nuclear weapons.

They Do It So We Must Do It Too

Reductions cannot go on forever, Secretary Gates argues because there is still a mission for nuclear weapons. Using language from the Clinton Administration, he says we can reduce our arsenal but we must also “hedge” against unexpected threats. He said, “Rising and resurgent powers, rogue nations pursuing nuclear weapons, proliferation of international terrorism, all demand that we preserve this hedge. There is no way to ignore efforts by rogue states such as North Korea and Iran to develop and deploy nuclear weapons or Russian or Chinese strategic modernization programs.”

While the potential threats he lists are real and must be addressed, how do nuclear weapons address these threats? And even if there were some nuclear component to our responses, the nature of those responses would be so varied that lumping these threats together muddles the issue. A nuclear response to international terrorism? Even if, for example, al Qaeda used a nuclear weapon to attack an American city, what target would we strike back at with a nuclear weapon? The implicit argument of symmetry is unsustainable. Just as we don’t respond to roadside bombs with our own roadside bombs, nor would we respond to chemical attack with chemical weapons or biological attack with biological weapons. We might respond to nuclear attack with nuclear weapons but we should not allow this to be an unstated assumption. The reason rogue nations, let’s say Iran and North Korea, are developing nuclear weapons is not to counter our nuclear weapons but as a counter to our overwhelming conventional capability. They certainly are not making the mistake of implicitly assuming symmetry.

The near universal logical sleight of hand is to make some argument for nuclear weapons, let’s say we need them because North Korea has them, and then, when people nod in agreement that we need nuclear weapons, let slip in the assumption that this implies we need the nuclear arsenal the administration wants. Not so fast. If North Korea has one, perhaps we need two, but that does not mean we need two thousand.

It helps to clarify the typically foggy nuke-think if we remove Russia and China from the picture and ask whether the United States could justify anything near its currently planned nuclear arsenal only to deter and defeat rogue states and terrorists. Of course not. And perhaps we don’t need nuclear weapons for regional scenarios at all, given our overwhelming conventional capabilities. So those odds and ends are thrown into the pot just to scare, not to explain, and not because there is any well thought out strategy for how nuclear weapons are going to stop a terrorist attack on an American city, or why it be an appropriate response to a regional state that doesn’t have the capability to threaten the survival of the United States.

Russia is a very different case: Russian long-range nuclear forces are the only things in the world today that could destroy us as a nation and society, just as we could destroy them. While relations with Russia are not friendly, no conceivable difference between the United States and Russia justifies this mutual hostage relationship. This pointless threat to our very existence persists because of a failure of imagination typified by this speech. In this case, it is the nuclear weapons that are creating the threat, not protecting us from it.

That Ole Warhead Production Fever

Whatever the supposed justification of nuclear weapons, the primary purpose of the Secretary’s speech seemed to be to promote the Reliable Replacement Warhead or RRW but again, his argument rests on hidden (and unjustified) assumptions and, at times, misstatements of fact. The basic premise is that, without testing, we are slowly but certainly losing confidence in the reliability of our nuclear arsenal. He said, “With every adjustment, we move farther away from the original design that was successfully tested when the weapons was first fielded.”

We do? The implication is that we have no other choice, what we could do in 1990 we simply can’t reproduce today, like handing a modern-day native American a hunk of flint and asking him to chip out an arrowhead. Why should this be? With a budget of billions of dollars, we can’t duplicate parts that we could make twenty years ago? We can spend billions on the National Ignition Facility to create the world’s most powerful laser but we can’t reproduce a 1980s O-ring? The problem the Secretary describes is certainly possible and something we have to be alert to but it isn’t inevitable; we can maintain weapons within design margins as long as we want and in the past—pre-RRW—that was precisely the plan. And parts of the weapon that are not the nuclear core of the bomb can be improved and modernized and tested as much as we want.

But Mr. Gates claims that we are slowly and helplessly drifting, “So the information on which we base our annual certification of the stockpile grows increasing dated and incomplete.” This implies the Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP) has failed. We believe the Secretary is wrong. Everyone we have talked to who is familiar with the enormous effort that has gone into the SSP says that our understanding of nuclear weapons today is substantially greater than it was the day after our last nuclear test. Our knowledge of the aging of nuclear warheads is increasing faster than the warheads are aging. Early uncertainties and concerns about stability, for example, of the plutonium parts of the weapon have been resolved and the parts have been shown to be stable for many decades, if not a century or more. Our computer models are dramatically and significantly more detailed and sophisticated. In fact, one weapon designer has told us that, given a fixed budget, the best investment of your next dollar would never be in a nuclear test but in more inspections, more computer simulations, more replacement of non-nuclear components, more material tests, more frequent tritium replenishment, and so forth.

|

How Many Times Does Congress Have to Say No? |

|

| Every time the Pentagon has proposed a new nuclear warhead since the end of the Cold War, Congress has refused to fund it. Now that the RRW appears to have been whacked, what will the next proposal for a new warhead look like? |

.

Aside from the question of the reliability of current warheads, Mr. Gates argues that we still need an RRW because we need to modernize. The British, French, Russians, and Chinese are modernizing so we must too, obviously. Why? Nuclear weapons are a mature technology. There is no new science in nuclear weapons. They are powerful, efficient explosives. They are intended to blow up things and they have specific missions, which typically involve blowing up specific things. If they can accomplish these missions, what is the problem? If the technology, even the weapons, is decades, even centuries old, if they work then they work. Nuclear weapons are not fighter planes or tanks or submarines, duking it out on a battlefield with the enemy’s opposite number, so our nuclear weapons should be evaluated with regard to the targets they are expected to destroy, not anyone else’s nuclear weapons. They can destroy the targets. We’re done.

The important factor is not the warhead but the delivery vehicle that is intended to bring the warhead to the target. And the reason the United States is not producing new nuclear weapons while Russia and China do is not because they can and we can’t, or they’re ahead and we’re behind, as the Secretary indicated. Rather, the United States has not been producing new nuclear weapons because it didn’t have to – the existing ones are more than adequate – and because not producing has been seen as much more important to U.S. foreign policy objectives. And if Russian and Chinese warhead production is a problem, why not propose how to influence them to change rather than advocating that we repeat their mistake?

The final argument for the RRW is that the US must maintain a nuclear production industry and the RRW is grist for that mill. But many of the RRW technologies and capabilities were developed by the very SSP that Gates now implies is failing. Six years ago – before they came up with RRW after having failed to get permission to build the Precision Low-Yield Weapon Design (PLYWD) and the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP) – the National Nuclear Security Administration assured Congress: “We believe the life extension programs authorized by the Nuclear Weapons Council for the B61, W80, and the W76 will sufficiently exercise the design, production and certification capabilities of the weapons complex” (emphasis added). That assurance was given after the Foster Panel recommended, “developing new designs of robust, alternative warheads.” Now the claim suddenly is that the life extension programs do not sufficiently exercise the weapons complex. At least get the argument straight.

What’s Around the Corner?

We would be more sympathetic to the production argument if the fundamental minimal needs of the nuclear production industry were better thought out and justified, but what we see is an effort to maintain a slimmed down version of what we have without thinking through what we need. In fact, if maintaining the production industry is the core objective, we would have expected the administration to ask for an RRW design that doesn’t need a complex production industry, one that is extremely simple, perhaps using uranium rather than plutonium, perhaps a clunky design but one sure to work that does not require any sophisticated skills that must be maintained in standby in perpetuity.

We’re concerned that in the end Congress will accept a beefed-up life extension program – they seem to have already found a name for it: Advanced Certification Program – that will relax the restrictions for what modifications can be made to existing warheads in order to incorporate as much as the RRW concept as possible and add new capabilities if necessary. Unless the next president significantly changes the nuclear guidance for what the Pentagon is required to plan for, RRW-like proposals will likely continue to make it harder to create a national consensus on the future role of nuclear weapons. And Barack Obama has not explicitly rejected the RRW, but said he does “not support a premature decision to produce the RRW” and “will not authorize the development of new nuclear weapons and related capabilities.” Enhanced life-extended warheads could fit within such a policy.

In the end, justifying the nuclear weapons production industry is shaky because the justification for the weapons themselves is shaky, resting on assertion and Cold War momentum – as Gates’ speech illustrated – more than on rigorous assessments of missions and the security of the nation.

The Secretary’s speech was a disappointing missed opportunity. We are a bit perplexed about why he gave it and gave it now. Perhaps he is putting down a marker for a debate he expects in the next administration and Congress. We welcome that debate because we believe that, with careful attention to definition and no hidden assumptions, the arguments for nuclear weapons fade away.

Dutch Government Rejects Blue Ribbon Review Findings

|

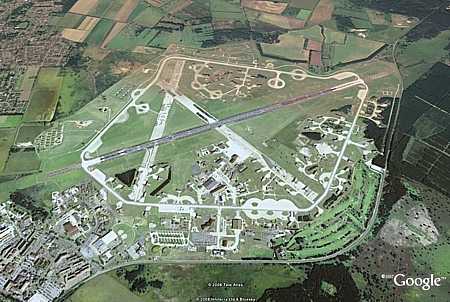

| The nuclear base at Volkel is pixeled out on Google Earth (why, Google?). Click on image to download map of the base (note: 1 MB). Image: GoogleEarth (outline and label added) |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Dutch Government today rejected the findings of the U.S. Air Force’s Blue Ribbon Review, saying the safety and security at the nuclear weapons base at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands “are in good order.”

The Blue Ribbon Review final report in February concluded that “most” nuclear sites in Europe do not meet U.S. safety requirements and that it would take “significant additional resources” to bring them up to standard. The disclosure of the findings has led to calls in some European countries that the remaining tactical nuclear weapons should be withdrawn.

During a meeting earlier today in the Defense Committee of the Dutch Parliament, Defense Minister Eimert van Middelkoop responded to a question from Krista van Velzen (Socialist Party) about the findings of the Blue Ribbon Review:

“Ms. van Velzen asked a question about the American report concerning the storage of nuclear weapons and Volkel. Insofar as this is relevant, safety and security at Volkel are in good order, but the government of the Netherlands does not make any announcements concerning the presence or absence of nuclear weapons embodying that single Dutch nuclear mission.” (unofficial translation)

|

Figure 1: |

|

| Dutch Defense Minister Eimert van Middelkoop (left) met with U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates in October 2007. Afghanistan was on the agenda, but isn’t it time to talk about the withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe? |

.

Although Mr. Middelkoop refused to confirm or deny whether there are nuclear bombs at the base, he did confirm that the Netherlands still has a nuclear mission. It would have been more interesting to hear his explanation for why that mission is still needed. The enemy is gone, the weapons would take “months” to ready for strike, and the U.S. Air Force would like to see the weapons withdrawn. The deployment increasingly looks like nuclear social welfare for a small group of NATO bureaucrats.

There are an estimated 10-20 U.S. B61 nuclear bombs stored at Volkel Air Base for delivery by Dutch F-16 fighter jets, part of an arsenal of approximately 200 nuclear bombs at six bases in five European countries.

Previous reports: USAF Report: “Most” Nuclear Sites in Europe do not Meet US Security Requirements (FAS, June 2008) | U.S. Nuclear Weapons Withdrawn From the United Kingdom (FAS, June 2008) | United States Removes Nuclear Weapons from German Base, Documents Indicate (FAS, July 2007) | U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe (NRDC, 2005)

U.S. Nuclear Weapons Withdrawn From the United Kingdom

More than 100 U.S. nuclear bombs have been withdrawn from RAF Lakenheath, the forward base of the U.S. Air Force 48th Fighter Wing. Image: GoogleEarth

The United States has withdrawn nuclear weapons from the RAF Lakenheath air base 70 miles northeast of London, marking the end to more than 50 years of U.S. nuclear weapons deployment to the United Kingdom since the first nuclear bombs first arrived in September 1954.

The withdrawal, which has not been officially announced but confirmed by several sources, follows the withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base in Germany in 2005 and Greece in 2001. The removal of nuclear weapons from three bases in two NATO countries in less than a decade undercuts the argument for continuing deployment in other European countries.

Status of European Deployment

I have previously described that President Bill Clinton in November 2000 authorized the Pentagon to deploy 110 nuclear bombs at Lakenheath, part of a total of 480 nuclear bombs authorized for Europe at the time.

US Nuclear Weapons in Europe 2008

President George Bush updated the authorization in May 2004, which apparently ordered the withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base in Germany. The withdrawal from Lakenheath might also have been authorized by the Bush directive, or by an update issued within the past three years. This reduction and consolidation in Europe was hinted by General James Jones, the NATO Supreme Commander at Europe at the time, when he stated in a testimony to a Belgian Senate committee: “The reduction will be significant. Good news is on the way.”

Last week I reported that security deficiencies found by the U.S. Air Force Blue Ribbon Review at “most” sites were likely to lead to further consolidation of the weapons, and that “significant changes” were rumored at Lakenheath.

Withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from three European bases since 2001 means that two-thirds of the arsenal is now on the southern flank.

The withdrawal from Lakenheath means that the U.S. nuclear weapons deployment overseas is down to only two U.S. Air Force bases (Aviano AB in Italy and Incirlik in Turkey) plus four other national European bases in Belgium, Germany, Holland and Italy, for a total of six bases in Europe. It is estimated that there are 150-240 B61 nuclear bombs left in Europe, two-thirds of which are based on NATO’s southern flank (see Table 1).

Some Implications

Why NATO and the United States have decided to keep these major withdrawals secret is a big puzzle. The explanation might simply be that “nuclear” always means secret, that it was done to prevent a public debate about the future of the rest of the weapons, or that the Bush administration just doesn’t like arms control. Whatever the reason, it is troubling because the reductions have occurred around the same time that Russian officials repeatedly have pointed to the U.S. weapons in Europe as a justification to reject limitations on Russia’s own tactical nuclear weapons.

In fact, at the very same time that preparations for the withdrawal from Ramstein and Lakenheath were underway, a U.S. State Department delegation visiting Moscow clashed with Russian officials about who had done enough to reduce its non-strategic nuclear weapons. General Jones’ “good news” could not be shared.

While NATO boasts about its nuclear reductions since the Cold War, the Alliance is more timid about the reductions in recent years.

By keeping the withdrawals secret, NATO and the United States have missed huge opportunities to engage Russia directly and positively about reductions to their non-strategic nuclear weapons, and to improve their own nuclear image in the world in general.

The news about the withdrawal from Lakenheath comes at an inconvenient time for those who advocate continuing deployment of U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe. By following on the heels of the withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base in 2004-2005 and Greece in 2001, the Lakenheath withdrawal raises the obvious question at the remaining nuclear sites: If they can withdraw, why can’t we?

What is at stake is not whether NATO should be protected with nuclear weapons, but why it is still necessary to deploy tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. Japan and South Korea are also covered by the U.S. nuclear umbrella, but without tactical nuclear weapons deployed in Asia. The benefits from withdrawing the remaining non-strategic nuclear weapons from Europe far outweigh the costs, risks and political objectives of keeping them there. The only question is: who will make the first move?

Previous reports: USAF Report: “Most” Nuclear Sites in Europe do not Meet US Security Requirements (FAS, June 2008) | United States Removes Nuclear Weapons from German Base, Documents Indicate (FAS, July 2007) | U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe (NRDC, 2005)

USAF Report: “Most” Nuclear Weapon Sites In Europe Do Not Meet US Security Requirements

|

| Members of the 704 Munition Support Squadron at Ghedi Torre in Italy are trained to service a B-61 nuclear bomb inside a Munitions Maintenance Truck. Security at “most” nuclear bases in Europe does not meet DOD safety requirements, a newly declassified U.S. Air Force review has found. Withdrawal from some is rumored. Image: USAF |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen [article updated June 26 following this report]

An internal U.S. Air Force investigation has determined that “most sites” currently used for deploying nuclear weapons in Europe do not meet Department of Defense security requirements.

A summary of the investigation report was released by the Pentagon in February 2008 but omitted the details. Now a partially declassified version of the full report, recently obtained by the Federation of American Scientists, reveals a much bigger nuclear security problem in Europe than previously known.

As a result of these security problems, according to other sources, the U.S. plans to withdraw its nuclear custodial unit from at least one base and consolidate the remaining nuclear mission in Europe at fewer bases.

European Nuclear Safety Deficiencies Detailed

The national nuclear bases in Europe, those where nuclear weapons are stored for use by the host nation’s own aircraft, are at the center of the findings of the Blue Ribbon Review (BRR), the investigation that was triggered by the notorious incident in August 2007 when the U.S. Air Force lost track of six nuclear warheads for 36 hours as they were flow across the United States without the knowledge of the military personnel in charge of safeguarding and operating the nuclear weapons.

|

Figure 1: |

|

|

“Most” nuclear sites in Europe don’t meet DOD security standards, according to the Blue Ribbon Review report. |

The final report of the investigation – Air Force Blue Ribbon Review of Nuclear Weapons Policies and Procedures – found that “host nation security at overseas nuclear-capable units varies from country to country in terms of personnel, facilities, and equipment.” The report describes that “inconsistencies in personnel, facilities, and equipment provided to the security mission by the host nation were evident as the team traveled from site to site….Examples of areas noted in need of repair at several of the sites include support buildings, fencing, lighting, and security systems.”

The situation is significant: “A consistently noted theme throughout the visits,” the BRR concluded, “was that most sites require significant additional resources to meet DOD security requirements.” Despite overall safety standards and close cooperation and teamwork between U.S. Air Force personnel and their host nation counterparts, the inspectors found that “each site presents unique security challenges.”

Specific examples of security issues discovered include conscripts with as little as nine months active duty experience being used protect nuclear weapons against theft.

Inspections can hypothetically detect deficiencies and inconsistencies, but the BRR team found that U.S. Air Force inspectors are hampered in performing “no notice inspections” because the host nations and NATO require advance notice before they can visit the bases. If crews know when the inspection will occur, their performance might not reflect the normal situation at the base.

Many of the safety issues discovered are precipitated by the fact that the primary mission of the squadrons and wings is not nuclear deterrence but real-world conventional operations in support of the war on terrorism and other campaigns. This dual-mission has created a situation where many nuclear positions are “one deep,” and where rotations, deployments, and illnesses can cause shortfalls.

The review recommended consolidating the bases to “minimize variances and reduce vulnerabilities at overseas locations.”

USAFE Commander Visits Nuclear Bases

In light of the findings about Air Force nuclear security, General Roger Brady, the USAFE Commander, on June 11 visited Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium and Volkel Air Base in Holland. Both bases store U.S. nuclear weapons for delivery by their national F-16 fighters.

.

A news story on a USAF web site notes that the weapons security issues found by the BRR investigation were “at other bases,” suggesting that Büchel Air Base in Germany or Ghedi Torre Air Base in Italy were the problem. Even so, the BRR found problems at “most sites,” visits to Kleine Brogel and Volkel were described in the context of these findings. Two commanders of the 52 Fighter Wing at Spangdahlem Air Base, which controls the 701st and 703rd Munitions Support Squadrons at the national bases, were also present “to witness both units for the first time.”

Withdrawal and Consolidation

The deficiencies at host nation bases apparently have triggered a U.S. decision to withdraw the Munition Support Squadron (MUNSS) from one of the national bases.

Four MUNSS are currently deployed a four national bases in Europe: the 701st MUNSS at Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium, the 702nd MUNSS at Büchel Air Base in Germany, the 703rd MUNSS at Volkel Air Base in Holland, and the 704th MUNSS at Ghedi Torre in Italy (see top image).

It is not yet known which base it is, but sources indicate that it might involve the 704th MUNSS at Ghedi Torre in Northern Italy.

Status of Nuclear Weapons Deployment [June 26: warhead estimate updated here]

The number and location of nuclear weapons in Europe are secret. However, based in previous reports, official statements, declassified documents and leaks, a best estimate can be made that the current deployment consists of approximately 150-240 B61 nuclear bombs (see update here). The most recent public official statement was made by NATO Vice Secretary General Guy Roberts in an interview with the Italian RAINEWS in April 2007: “We do say that we’re down to a few hundred nuclear weapons.”

|

Table 1: |

|

|

Derived from more extensive table. Click table or here to download the full table. |

The U.S. weapons are stored in underground vaults, known as WS3 (Weapon Storage and Security System), at bases in Belgium, Germany, Holland, Italy, and Turkey. Most of the weapons are at U.S. Air Force bases, but Belgium, Germany, Holland and Italy each have nuclear weapons at one of their national air bases.

The weapons at each of the national bases are under control of a U.S. Air Force MUNSS in peacetime but would, upon receipt of proper authority from the U.S. National Command Authority, be handed over to the national Air Force at the base in a war for delivery by the host nation’s own aircraft. This highly controversial arrangement contradicts both the Non-Proliferation Treaty and NATO’s international nonproliferation policy.

Implications and Observations

The main implication of the BRR report is that the nuclear weapons deployment in Europe is, and has been for the past decade, a security risk. But why it took an investigation triggered by the embarrassing Minot incident to discover the security problems in Europe is a puzzle.

Since the terrorist attacks in September 2001, billions of dollars have been poured into the Homeland Security chest to increase security at U.S. nuclear weapons sites, and a sudden urge to improve safety and use control of nuclear weapons has become a principle justification in the administration’s proposal to build a whole new generation of Reliable Replacement Warheads.

But, apparently, the nuclear deployment in Europe has been allowed to follow a less stringent requirement.

This contradicts NATO’s frequent public assurances about the safe conditions of the widespread deployment in Europe. Coinciding with the dramatic reduction of nuclear weapons in Europe after the Cold War 15 years ago, “a new, more survivable and secure weapon storage system has been installed,” a NATO fact sheet from January 2008 states. “Today, the remaining gravity bombs associated with DCA [Dual-Capable Aircraft] are stored safely in very few storage sites under highly secure conditions.”

Apparently they are not. Yet despite the BRR findings, the NATO Nuclear Planning Group meeting in Brussels last week did not issue a statement. But at the previous meeting in June 2007 the group reaffirmed the “great value” of continuing the deployment in Europe, “which provide an essential political and military link between the European and North American members of the Alliance.”

That NATO – nearly two decades after the Cold War ended – believes it needs U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in Europe to keep the alliance together is a troubling sign. NATO air forces are stretched thin to meet real-world operations in the war against terrorism and other campaigns, and tactical nuclear weapons are not a priority, no matter what nuclear bureaucrats might claim.

Even Republican presidential candidate John McCain apparently does not believe tactical nuclear weapons in Europe are essential for NATO. On May 27 he stated that, if elected, he would, “in close consultation with our allies…like to explore ways we and Russia can reduce – and hopefully eliminate – deployments of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe.”

Many European governments would support such a plan – even though some of the new eastern European NATO members see Russian resurgence as a reason to continue the deployment. But their security concerns can be met by other means, and Germany and Norway have already been pushing a proposal inside NATO for a review of the alliance’s nuclear policy, the Belgium parliament has called for a withdrawal, and there is overwhelming cross-political public support in Germany to end the deployment in Europe.

Perhaps the BRR findings will help empower these countries and convince NATO and the next U.S. administration that the time has come to finally complete the withdrawal of tactical nuclear weapons from Europe.

Additional Information: Blue Ribbon Review (2008 report) | United States Removes Nuclear Weapons From German Base, Documents Indicate (2007 report) | US Nuclear Weapons in Europe (2005 report)

United States Removes Nuclear Weapons From German Base, Documents Indicate

|

|

The United States appears to have quietly removed nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base. Here a B61 nuclear bomb is loaded unto a C-17 cargo aircraft. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. Air Force has removed its main base at Ramstein in Germany from a list of installations that receive periodic nuclear weapons inspections, indicating that nuclear weapons previously stored at the base may have been removed and withdrawn to the United States.

If correct, the withdrawal reduces the number of U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe to an estimated 350 B61 bombs, or roughly equivalent to the size of the entire French nuclear weapons inventory.

New Nuclear Inspection List

The new nuclear inspection list is contained in the unclassified instruction Nuclear Surety Staff Assistance Visit (NSSAV) and Functional Expert Visit (FEV) Program Management published by the U.S. Air Forces in Europe (USAFE) on January 29, 2007. The instruction supersedes an earlier version from March 29, 2005, which did include Ramstein Air Base.

The NSSAV team includes 14-31 inspectors with expertise in the different areas of nuclear weapons mission management. The NSSAV normally takes place six months prior to the a Nuclear Surety Inspection (NSI), and the visit is intended to help prepare the unit for the much more rigid NSI, which units with nuclear weapons mission responsibilities must pass at least every 18 months to remain certified to handle and store nuclear weapons. During the visit, which normally lasts a week, the NSSAV team observes and evaluates how the unit conducts day-to-day operations and administers nuclear surety program management. A typical visit includes uploading and downloading of training nuclear weapons on strike aircraft.

|

|

|

|

Sources: U.S. Air Forces in Europe, Instruction 91-125, Nuclear Surety Staff Assistance Visits (NSSAV) and Functional Expert Visits (FEV) Program Management, January 29, 2007; U.S. Air Forces in Europe, Instruction 91-125, Nuclear Surety Staff Assistance Visits (NS SAV) and Functional Expert Visits |

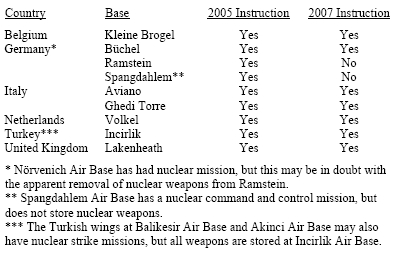

A Brief History of U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe

The current number of approximately 350 nuclear weapons is only a fraction of the force level the United States deployed in Europe during the Cold War. That level reached a peak of 7,300 weapons in 1971. The number dropped to 4,000 by the end of the Cold War in 1990, plunged to 700 in 1992, and leveled off at approximately 480 weapons (all bombs) in 1994. This ended the dramatic period of nuclear disarmament initiatives, which has since been replaced by a period of relative stability with slow and gradual reductions happening mainly due to base closures rather than arms control initiatives.

One of the last acts of the Clinton administration in late 2000 was to authorize deployment of 480 nuclear bombs at nine bases in seven European NATO countries. Twenty of the bombs were withdrawn in 2001 after Greece pulled out of the NATO nuclear strike mission, and another 20 were withdrawn in 2003 when Germany closed Memmingen Air Base.

The Bush administration updated the deployment authorization for Europe in May 2004 to reflect these changes, and it is possible that the authorization may have cleared the withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base. But as of late March 2005, Ramstein was still on the updated list of installations receiving nuclear surety staff assistance visits. The report U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe published by the Natural Resources Defense Council in February 2005 estimated 440-480 nuclear bombs deployed in Europe.

|

US Nuclear Weapons in Europe, 1954-2007 |

|

| The U.S. deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe peaked in 1971 at 7,300 weapons, was reduced significantly a decade and a half ago, but has remained comparatively stable since then. |

Then in May 2005, the German magazine Der Spiegel cited unnamed German defense officials saying that the U.S. had quietly removed nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base during major construction work at the base. The assumption was that the move was temporary, but the German officials hoped they would never return. Their wish seems to have come through with Ramstein’s removal from the updated Air Force instruction published in January 2007.

Both the U.S. government and NATO have always refused to disclose the number of weapons deployed in Europe but occasionally have provided the approximate range of the force level or the percentage of reduction since the Cold War. In an interview with Italian RAINEWS in April 2007, NATO Vice Secretary General Guy Roberts also refused to disclose the number weapons, but explained: “We do say that we’re down to a few hundred nuclear weapons.”

Seen in Cold War context, 350 bombs may not seem like a lot, but for the post-Cold War era it is a significant force. It is roughly equivalent is size to the entire French nuclear arsenal, larger than the Chinese nuclear arsenal, and it is larger that the nuclear arsenals of all the three non-NPT countries Israel, India and Pakistan combined.

Recent Reaffirmation of Nuclear Mission

Despite the apparent reduction, NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) as recently as June 15, 2007, reaffirmed the importance of deploying U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe. NPG stated that the purpose of the weapons is to “preserve peace and prevent coercion and any kind of war,” and that NATO places “great value” on the U.S. deployment in Europe. The NPG did not identify any particular enemy that the weapons are intended to protect against, but instead said they “provide an essential political and military link between the European and North American members of the Alliance.”

|

|

|

|

The only nuclear weapons storage site in Germany now appears to be Büchel Air Base, where theft – not enemy attack – is the main threat, as practiced by these security forces in February 2007. |

Germany’s Nuclear Decline

The apparent withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base also raises questions about the continued nuclear strike mission of the German Tornado squadron at Nörvenich Air Base. The base previously stored nuclear weapons, but they were moved to Ramstein in 1995 with the intent that they could quickly be returned to Nörvenich if necessary. A withdrawal from Ramstein would indicate that the 31st Wing at Nörvenich probably no longer has a nuclear strike mission, and that Germany’s contribution to NATO nuclear mission now is reduced to Büchel Air Base.

A reduction to a single German nuclear base with “only” 20 nuclear bombs is a dramatic change from the late-1980s, when more than 2,570 nuclear weapons were deployed at dozens of locations across the country. The latest withdrawal follows a political seachange in German voters’ views on nuclear weapons in the country. A poll published by Der Spiegel in 2005 revealed an overwhelming support across the political spectrum for a complete withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Germany.

The German government said in May 2005 that it would raise the issue of continued deployment within NATO, but officials later told Der Spiegel that the government had changed its mind. Yet the withdrawal from Ramstein indicates that the government has been more proactive than thought or that the Bush administration “got the message” and decided not to return the weapons. The withdrawal reduces Germany from the status of a major nuclear host nation to one on par with Belgium and the Netherlands, both of which also only have one nuclear base. The German government can now safely decide to follow Greece, which in 2001 unilaterally left NATO’s nuclear club. This in turn would open the possibility that Belgium (and likely also the Netherlands) will follow suit, essentially throwing NATO’s long-held principle of nuclear burdensharing into disarray.

A New Southern Focus

For now, the withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base shifts the geographic focus of NATO’s nuclear posture to the south. Before the withdrawal, a clear majority of NATO’s nuclear weapons were deployed in Northern and Central Europe. After the withdrawal, however, more than half (51%) of the weapons are deployed in Southern Europe along the Eastern parts of the Mediterranean Sea in Italy and Turkey.

The geographic shift has implications for international security issues that NATO countries are actively involved in, such as the attempts to create a Mediterranean Nuclear Weapons Free Zone, and the efforts to persuade countries like Iran not to develop nuclear weapons. The new southern focus of NATO’s nuclear posture will make it harder to persuade other countries in the region to show constraint.

Background: Satellite Images of U.S. Nuclear Weapon Bases Europe | U.S. Nuclear Weapons In Europe (report from 2005)