Publication: US Nuclear Weapons in Europe

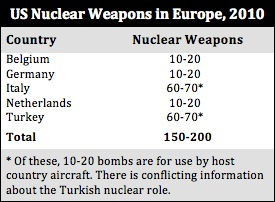

The US Air Force deploys 150-200 B61 nuclear bombs in Europe.

Following NATO’s strategic concept and expectations that the next round of US-Russian nuclear arms control negotiations will deal with tactical nuclear weapons in some shape or form, Stan Norris and I have published our latest estimate on U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Although the strategic concept states that “any” further reductions “must take into account the disparity with the greater Russian stockpiles of short-range nuclear weapons,” NATO has in fact been willing to make significant unilateral reductions in this decade regardless of disparity. Likewise, the United States has scrapped most of its tactical nuclear weapons because they are no longer important. It is important that the disparity argument does not become an excuse to prevent further reductions.

Our estimate of Russian tactical nuclear weapons is here with more details here.

Later this spring we will publish a more comprehensive report on U.S. and Russian tactical nuclear weapons.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Tac Nuke Numbers Confirmed?

|

| PDUSPD Jim Miller appears to confirm FAS/NRDC estimates for NATO and Russia tactical nuclear weapons. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

A Wikileaks document briefly posted by The Guardian Monday appears to give an official number for the U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe: 180.

The number appears in a leaked cable written by U.S. NATO Ambassador Ivo Dalder in September 2009, describing an earlier Nuclear Posture Review briefing U.S. Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Jim Miller gave to NATO in July 2009.

Miller’s number is smack in the middle of the estimate Stan Norris and I have developed. I recently published a snapshot here (previous NATO posts are here), and a more detailed overview will appear in the January Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Miller also stated that Russia had 3,000-5,000 plus tactical nuclear weapons. That also fits our estimate of approximately 5,300 weapons, previously published here and here.

Whether Miller was providing certified U.S. intelligence numbers or simply referenced good-enough nonofficial public estimates is less clear. But his use of a specific number (180) for Europe rather than a range suggests that it might an official number.

It’s Up, It’s Down

The cable first appeared in a Guardian story that was posted on the news paper’s web site Monday with the cable. The posting was a mistake and the story was quickly taken down (the editors decided that the initial story didn’t contain significant news; it may get back up), but not before bloggers had picked it up. The first reposting of the document appeared on Hedgehogs.

I’ve since tried to find the cable on the Wikileaks web site, but it doesn’t seem to be there. If anyone knows the original link, please let me know.

Implications

I’ll publish on U.S. and Russian tactical nuclear weapons later in 2011, but the importance of the number 180 (if correct) is that it confirms that the United States during the past decade has been unilaterally reducing the deployment in Europe without demanding reductions in Russian tactical nuclear weapons. Miller correctly points to “the difficulty of bringing Russia to the bargaining table with 180 NATO sub-strategic warheads on offer against the estimated 3-5 thousand Russian warheads in that category.”

As I recently pointed out, there is important progress in NATO’s new Strategic Concept, but some language is unfortunate because it appears to reinstitute Russian as an adversary by demanding that any addition reductions in U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe must take into consideration Russia’s larger inventory of tactical nuclear weapons.

Some Baltic NATO countries have called for new contingency planning against Russia, but Ambassador Dalder pointed to the dilemma this creates for NATO’s long-held position that Russia is not an enemy.

I couldn’t agree more. NATO and the United States should certainly try to convince Russia to reduce its tactical nuclear weapons, but the previous unilateral U.S. reductions in Europe demonstrate that NATO can and should decide the future of the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe independent of the number of Russian tactical nuclear weapons.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

NATO Strategic Concept: One Step Forward and a Half Step Back

|

| NATO General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen presents the alliance’s new Strategic Concept |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The new Strategic Concept adopted today by NATO represents one step forward and a half step backward for the alliance’s nuclear weapons policy.

The forward-leaning part of the nuclear policy pledges to actively try to create the conditions for further reducing the number of and reliance on nuclear weapons, recommits to the ultimate goal of nuclear disarmament, and reaffirms that circumstances in which the alliance could contemplate using its nuclear weapons are “extremely remote.”

But the strategy fails to present any steps that reduce the number of or reliance on nuclear weapons. As such, the new Strategic Concept – Active Engagement, Modern Defence – falls short of the Obama administration’s recent Nuclear Posture Review.

Even so, there are important changes in the document that hint of things to come.

The Role of Nuclear Weapons

The new Strategic Concept does not explicitly reduce the role of NATO’s nuclear weapons. Instead, it echoes the Obama administration’s formulation that “as long as nuclear weapons exist,” NATO will remain a nuclear alliance.

And the formulation in the 1999 Strategic Concept that “NATO’s nuclear forces no longer target any country” is gone from the new document. Instead, it states that NATO “does not consider any country to be its adversary.”

Overall, the 2010 document is far less explicit than the 1999 document about what the role of nuclear weapons is. The previous document explicitly described the role “to preserve peace and prevent coercion and war of any kind…by ensuring uncertainty in the mind of any aggressor about the nature of the Allies’ response to military aggression,” and “demonstrate that aggression of any kind is not a rational option.”

The new document, in contrast, describes the role of nuclear weapons in very general terms, essentially with no specifics, and as part of an overall mix of nuclear and conventional capabilities.

Gone is the previous language about U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in Europe providing an essential political and military link between Europe and North America, or that sub-strategic forces provide a link with strategic forces.

Instead, the document states that it is the strategic forces of the United States, in particular, and to some extent Britain and France, that provide the “supreme guarantee of the security of the Alliance”.

US Nuclear Forces in Europe

Combined, these significant changes could be seen as hints of an attempt to lessen the importance the alliance attributes to having U.S. tactical nuclear weapons forward deployed in Europe.

To be sure, the document still contains what appears to be a commitment to some form of U.S. nuclear presence in Europe, by committing to “the broadest possible participation of Allies in collective defence planning on nuclear roles, in peacetime basing of nuclear forces, and in command, control and consultation arrangements.” (Emphasis added)

|

But this is vague language compared with the 1999 document. It could simply be met by Allies taking part in Nuclear Planning Group meetings, deployment of some U.S. dual-capable aircraft in Europe but without weapons, and Allies continuing to be part of the decision making process for potential use of nuclear weapons.

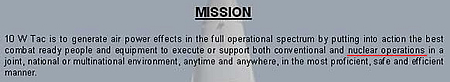

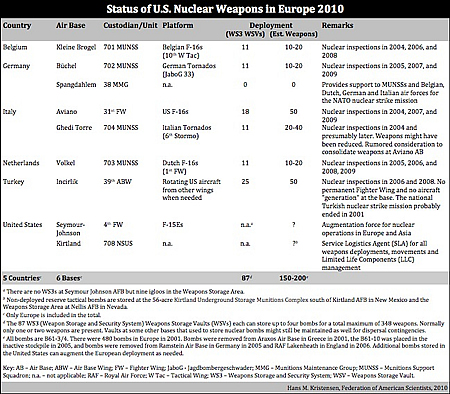

The number of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe today is down to 150-200 B61 bombs deployed at six bases in five countries (see table).

The Role of Russia

In the years between the 1999 and 2010, NATO unilaterally reduced the number of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons deployed in Europe by more than half, from 480 to 150-200 B61 bombs. The 1999 Strategic Concept did not mention Russia at all as a factor for sizing the U.S. deployment.

The new Strategic Concept, in contrast, returns Russia to a central position for how the Alliance sizes the number of U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

“In any future reductions,” NATO declares, “our aim should be to seek Russian agreements to increase transparency on its nuclear weapons in Europe and relocate these weapons away from the territory of NATO members.”

Moreover, “Any further steps must take into account the disparity with the greater Russian stockpiles of short-range nuclear weapons.”

While seeking to achieve reductions in Russian tactical nuclear weapons is important – it has more than 5,000 of them, formally linking the U.S. deployment in Europe to Russia seems to contradict the policy of the past two decades that the U.S. weapons in Europe are not directed against Russia. And NATO has repeatedly made unilateral reductions without demanding Russian reductions. Indeed, the new Strategic Concept declares that “NATO poses no threat to Russia,” and that the Alliance “does not consider any country to be its adversary.”

So to begin now to argue that the size of the U.S. arsenal in Europe is linked to Russia after all resembles the Cold War policy when NATO looked to Russia for sizing the U.S. arsenal in Europe.

Moreover, Russia’s tactical nuclear weapons posture is less tied to the U.S. nuclear posture in Europe and more to Russia’s perception of countering NATO’s superior conventional forces and defending the long border with China. Since those factors determine the size of the large Russian tactical nuclear weapons arsenal, it is hard to see why Moscow would agree to reduce its tactical nuclear weapons in return for reductions of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in Europe.

The Future

The changes in the new Strategic Concept are many and important. The language could hint that NATO may be preparing the ground for the withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe. But the way forward is muddled with preconditions on Russian reductions.

A joint communiqué from the Lisbon Summit might make things clearer tomorrow but it will require a new deterrence review in 2011 for NATO to translate what the Strategic Concept means for NATO’s nuclear posture.

Conditioning future reductions on Russia could be a roadblock, so hopefully the vague “aim to seek” and “taking into account” formulations don’t imply tit-for-tat reciprocity. The success of the unilateral withdrawals in the early 1990s suggests that a unilateral withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe would be more effective in stimulating a Russian response.

The Obama administration sees the emergence of a “new, tailored, regional deterrence architecture” that “make[s] possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” The new Strategic Concept seems to agree, so hopefully the Obama administration can now become more assertive in pushing for a withdrawal of the last U.S. tactical nuclear weapons from Europe so it can focus on an agreement to reduce U.S. and Russian tactical nuclear weapons in general.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Delay: Gambling With National and International Security

|

| A few Senators are preventing US inspectors from verifying the status of Russian nuclear weapons. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The ability of a few Senators to delay ratification of the New START treaty is gambling with national and international security.

At home the delay is depriving the U.S. intelligence community important information about the status and operations of Russian strategic nuclear forces. And abroad the delay is creating doubts about the U.S. resolve to reduce the number and role of nuclear weapons, doubts that could undermine efforts to limit proliferation.

New START may not be the most groundbreaking treaty ever, but it is a vital first step in moving U.S.-Russian relations forward and paving the way for additional nuclear reductions and nonproliferation efforts. Essentially all current and former officials and experts recommend verification of New START, and after more than 20 hearings and nearly 1,000 detailed questions answered it is time for the Senate to ratify the treaty.

Important Inspections

Ratification would set in motion a wide range of data exchange and on-site inspection activities. By delaying ratification, the Senators are depriving the U.S. intelligence community important information about Russian nuclear forces. Apart from monitoring how Russian strategic nuclear forces are evolving and operating, the information is important to avoid worst-case threat assessments that can negatively affect U.S.-Russian relations.

It has now been 348 days since the last U.S. inspection team left Russia.

During the 15 years the START Treaty was in effect between 1994 and 2009, U.S. teams conducted 659 inspections of Russian nuclear weapons facilities; Russian conducted 481 inspections of U.S. facilities.

The last U.S. on-site inspection took place on November 18-19, 2009, at an SS-25 mobile missile base near Teykovo, approximately 130 miles (210 km) northeast of Moscow.

.

That inspection had special meaning because the SS-25 is being phased out from this area and replaced with the new SS-27. While each SS-25 is equipped with one warhead, the SS-27 comes in two versions: one with a single warhead and one with three warheads. The U.S. intelligence community calls the latter the SS-27 Mod 2, while the Kremlin named it RS-24 so as to avoid conflict with the now expired START treaty.

One of the four bases at Teykovo has already been equipped with the SS-27 Mod 2, two still have the SS-25, while the fourth base has been emptied and might be converting to the newer missile. Within the next decade, all four bases may be equipped with the SS-27 Mod 2.

The Russians chose Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri for their final on-site inspection in the United States. That inspection took place on December 1-2, 2009, just two days before the treaty expired.

| B-2 of the 509th Bomb Wing over Whiteman AFB |

|

| Russia chose the B-2 base at Whiteman Air Force Base as its final inspection in the United States under the now expired START treaty. |

.

The Nonproliferation Gamble

From the outset, the Obama administration appears to have seen Russia as the main potential obstacle to the treaty, rather than the U.S. Senate. Absent a strategy to secure the votes for ratification early on, the tables have now turned; with the White House desperate to secure ratification, a few Senators who still see Russia through Cold War lenses have effectively managed to use hearings and voting rules to extort concessions (read: money) from the administration to modernize the nuclear weapons production complex and delivery systems.

| Senator Jon Kyl |

|

| A few senators, most prominently Senator Jon Kyl (R-Arizona), have managed to delay ratification of the New START treaty. |

.

The administration quickly agreed to boost the FY 2011 budget for the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) well above the FY 2010 level. But that didn’t satisfy the Senators. So when Congress was unable to approve the budget before the mid-term election, the administration agreed that a Continuing Resolution (CR) designed to keep federal agencies operating at FY2010 budget levels through December 3rd would include an exemption for NNSA’s weapons program to fund the agency at the higher FY 2011 budget request – about $7 billion or an additional $625 million. But since the provisions in the defense appropriations bill and report don’t apply to the CR, the appropriators have lost control of how the funds are used; Congress is basically providing NNSA with a blank check to spend the $7 billion.

In addition, in an effort to buy the Senators’ votes for ratification during the “lame duck” session before the new Congress begins, the administration has offered $600 million more for the FY 2012 NNSA budget above FY 2011 levels, as well as an additional $3.6 billion spread out over FY 2013-2016.

Altogether, in a nuclear spending spree that would have been inconceivable during the Bush administration, the Obama administration plans to spend well over $180 billion to modernize nuclear weapons delivery systems and production facilities over the next decade.

There is a real risk that in the coming years, this modernization could backfire and undermine the second pillar of U.S. nuclear policy: strengthening nonproliferation.

The reason is simple: U.S. nonproliferation efforts dependent upon international support, but if the international community sees the increased nuclear modernizations as contradicting the U.S. pledge to work toward nuclear disarmament, some countries may well decide not to support the administration’s nonproliferation agenda.

This risk could be compounded later this week if NATO approves a new Strategic Concept that reaffirms the importance of nuclear weapons – and fails to order the withdrawal of the remaining tactical nuclear weapons from Europe.

The Senate needs to demonstrate that it understands that the Cold War is over and that it cares more about national and international security than politics by ratifying the New START treaty before Christmas. And the administration must be careful to balance its nuclear modernization plans with the need to sustain the vision of nuclear disarmament that so inspired the international community just 18 months ago.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Rasmussen: Lay Short-Range Nuclear Weapons Thinking to Rest

By Hans M. Kristensen

The next steps in European security should include additional reductions in the number short-range nuclear weapons in Europe, according to a video statement issued by NATO General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen:

“We also have to make progress sooner or later in our efforts to reduce the number of short-range nuclear weapons in Europe. NATO has cut the number of short-range nuclear weapons in Europe by over 90 percent. But there are still thousands of short-range nuclear weapons left over from the Cold War and most of them are in Russia. NATO is not threatening Russia and Russia is not threatening NATO. Time has come to lay this Cold War thinking to rest and focus on the common threats we face from outside: terrorism, extremism, narcotics, proliferation of missiles, weapons of mass destruction, side by side, and piracy. We can make progress of all three tracks – missile defense, conventional forces, and nuclear weapons – and create a secure Europe. It is time to stop spending our time and resources watching each other and look outward at how to reinforce our common security hope.”

That vision appears similar to the “new regional deterrence architecture” that several recent Obama administration reviews concluded would permit a reduction of the role of nuclear weapons. With that in mind, and Rasmussen’s conclusion that “Russia is not threatening NATO” and that the “time has come to lay this Cold War thinking to rest,” it should be relatively straightforward for him to recommend a withdrawal of the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe.

Unfortunately, rather than taking the initiative to complete the withdrawal of U.S. short-range nuclear weapons from Europe – a process that have been underway now for two decades but held up by Cold War thinking and NATO bureaucrats, Rasmussen instead appears to weave the future of the weapons in Europe into a web of new conditions that must be met first. In a speech at the Aspen Institute in Rome, Rasmussen described his three-track vision of collaborating with Russia on missile defenses, conventional weapons negotiations, and reducing short-range nuclear weapons:

“I think we have before us three tracks, which, if we follow them, will lead to a different, better and safer Europe: where we don’t look over our shoulders for someone else’s tanks or fighters; where missile defences bind us together, and protect us too; and where steadily, the number of short-range nuclear weapons on the continent is going down.”

Nuclear reductions appear to be the third track, after missile defense collaboration and conventional arms negotiations with Russia. For two decades, NATO has insisted the U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe have no military mission and that they’re not linked to Russia. The alliance has repeatedly been capable of and willing to make unilateral reductions – even complete withdrawal from Greece and the United Kingdom – without conditions or demanding reductions in Russian short-range nuclear weapons.

So why start linking reductions to Russia now?

Doing so seems to turn back the clock to the Cold War when NATO looked to Russia’s military forces to determine its nuclear posture in Europe. If the conclusion that “Russia is not threatening NATO” is more than words, then why make a three-track vision that assumes that Russia’s short-range nuclear weapons threaten NATO? Because the short-range weapons are not covered by any arms control regime, Rasmussen explains, the lack of transparency “makes allies cautious.”

There are certainly many good reasons to want to try to secure and reduce Russian short-range nuclear weapons. But if Russia is not threatening NATO, then Russian and U.S. short-range nuclear weapons should be addressed as a generic arms control challenge and not one that is linked to whether the U.S. has nuclear weapons in Europe or not.

| Did They Lay Cold War Nuclear Thinking to Rest? |

|

| During his meeting with Italian defense minister Ignazio La Russa, did Rasmussen discuss the possibility of a withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe, including Italy, or just the threat of Russian short-range nuclear weapons? |

.

If NATO unilaterally withdrew the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe, what would happen?

Would Russia decide that it didn’t have to reduce its short-range nuclear weapons? Hardly, since those forces seem to be more tied to Russia’s perception of NATO’s conventional superiority and a need to safeguard the long border with China. Besides, many of the Russian weapons are so old that they’re likely to be retired soon.

Would Russia get an advantage in a hypothetical crisis with NATO? Hardly, since it would require that Russia ignores NATO’s conventional superiority and U.S., British, and French long-range nuclear forces.

Would Russia decide that it had more freedom to deploy conventional forces on NATO periphery? Hardly, since such decisions seem to be made regardless of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe.

Would Iran somehow conclude that it could take additional steps acquiring nuclear weapons capability? Hardly, since its security assessment is not affected by whether the U.S. deploys nuclear weapons in Europe and it would still face serious consequences if it developed – certainly if it used – nuclear weapons.

Would Turkey and Eastern European NATO members conclude that NATO’s security guarantee was no longer credible and begin building nuclear weapons? Hardly, since their assurance is much more determined by conventional forces and political relations, and, to the limited extent nuclear forces play any role, the long-range forces of the United States, Britain, and France, would be more than adequate for any realistic scenario. Moreover, any NATO member country that began to develop nuclear weapons would face enormous pressure from the international community and from within NATO itself.

To the extent that some officials in some eastern European NATO countries feel uneasy about the inevitable withdrawal of U.S. short-range nuclear weapons from Europe, the obvious job for the Obama administration and the majority of NATO countries that favor a withdrawal is a concerted effort to educate those officials about the significant conventional and long-range nuclear capabilities that will continue to provide security when the short-range weapons are withdrawn. The revised Strategic Concept to be adopted at the Lisbon Summit in November is expected to reaffirm a role for nuclear weapons in NATO.

Rasmussen would do more for European security if he tried to decouple the future of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe from the need to reduce and eventually eliminate short-range nuclear weapons in general. Doing so would indeed be to “lay this Cold War thinking to rest.”

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

FAS side events at the RevCon

by Alicia Godsberg

Yesterday FAS premiered our documentary Paths To Zero at the NPT RevCon. The screening was a great success and there was a very engaging conversation afterward between the audience and Ivan Oelrich, who was there to promote the film. As a result of some suggestions, we are hoping to translate the narration to different languages so the film can be used as an educational tool around the world. You can see Paths To Zero by following this link – we will also be putting up the individual chapters soon.

This morning I spoke at a side event at the NPT RevCon entitled “Law Versus Doctrine: Assessing US and Russian Nuclear Postures.” I was asked to give FAS’s perspective on the New START, NPR, and new Russian military doctrine. Several people asked me for my remarks, so I’m posting them below the jump. (more…)

Speaking at the NPT-Review Conference

|

| The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference is Underway in New York |

By Hans M. Kristensen

I gave two talks at the review conference of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, both on non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The first was an FAS/BASIC panel on May 10 on Prospects for a shift in NATO’s nuclear posture.

The second was a panel organized by Pax Christi on May 12 on NATO’s nuclear policy.

My prepared remarks follow below:

U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Which Way Forward?

Hans M. Kristensen

Director, Nuclear Information Project

Federation of American Scientists

Presentation to FAS/BASIC Panel on Shifting NATO’s Nuclear Posture

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference, New York, May 10, 2010I’ve been asked to talk about the status of the deployment in Europe and about the Obama administration’s policy. There are of course many other issues affecting the status and future of the deployment, but let me focus on those two here.

There are currently about 200 U.S. nuclear bombs deployed in Europe. That is a far cry from the peak of 7,300 tactical nuclear weapons that were deployed there in 1971. But comparing with the Cold War is no longer relevant; the issue is how the posture fits the security challenges of today.

The deployment currently is about as big as the entire Chinese arsenal, or nearly as much as India, Pakistan, and Israel have combined. That’s a lot for an arsenal that NATO says is not targeted or directed against anyone.

Yet for an alliance that officially emphasizes the importance of continued and widespread deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, the past two decades have been a contradiction: since 1993 when the withdrawal of ground-launched and naval weapons was completed, these “essential” bombs have been reduced from 700 to 200, the number of nuclear bases reduced from 14 to 6, and the number of countries participating in the NATO strike mission reduced from six to four.

The burden sharing principle has been reduced to a shadow of it former self: out of NATO’s 28 members, only five (18 percent) have nuclear weapons on their territory, and only four (14 percent) have the strike mission. Most recently, three of the remaining four asked NATO to formally discuss the future of the mission.

The practice of equipping and training non-nuclear NPT signatories in NATO with U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities was largely tolerated by the NPT community during the Cold War. But this arrangement is untenable in an era where the focus is on nonproliferation because it muddles the message, condones double standards, and is – plain and simple – in contradiction with the intention of the NPT. It is not a standard NATO or the United States should defend today.

So although some officials cling to Cold War arguments for maintaining U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, the reality is that it is entirely in line with post-Cold War NATO policy and actions to reduce, curtail, and phase out the nuclear mission. It’s not going the other way. So NATO’s focus should not be whether to withdraw the weapons but how.

The top of the new American administration supports a withdrawal from Europe. You might be surprised to hear that given Hillary Clinton’s statements in Tallinn last month and what some defense officials are saying inside. But those statements are part of a strategy intended to avoid triggering a backlash from some Eastern European NATO countries and Turkey that could lock NATO’s Strategic Concept into decades of nuclear status quo.

The strategy reflects that a clear priority of the Obama administration is to reassure allies and partners and repair the rift that began to open during the previous administration. The Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), the Ballistic Missile Defense Review (BMDR), and the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) all emphasize this, and all hint of changes to come in the European deployment.

The QDR states: “To reinforce U.S. commitments to our allies and partners, we will consult closely with them on new, tailored, regional deterrence architectures that combine our forward presence, relevant conventional capabilities (including missile defenses), and continued commitment to extend our nuclear deterrent. These regional architectures and new capabilities, as detailed in the Ballistic Missile Defense Review and the forthcoming Nuclear Posture Review, make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” (Emphasis added.)

The BMDR is a little more explicit, stating: “Against nuclear-armed states, regional deterrence will necessarily include a nuclear component (whether forward-deployed or not). But the role of U.S. nuclear weapons in these regional deterrence architectures can be reduced by increasing the role of missile defenses and other capabilities.” (Emphasis added.)

Although the NPR states that the presence of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe and the nuclear sharing arrangement “contribute to Alliance cohesion and provide reassurance to allies and partners who feel exposed to regional threats,” it also reminds that extended deterrence relies less and less of nuclear weapons and that the role will continue to decrease as the new, regional, deterrence architecture matures.

This new, tailored, regional deterrence architecture includes all components of U.S. military capabilities, ranging from effective missile defense, counter-WMD capabilities, conventional power-projection capabilities, and integrated command and control – all underwritten by strong political commitments. The missile defense, the NPR states explicitly, is “part of our extended deterrent and a visible demonstration of our Article 5 commitment to Europe.”

So it is important to understand that the Obama administration sees its security commitments as much more – and increasingly other – than forward deployment of nuclear bombs in Europe. In fact, the forward deployment is the least relevant today, and many U.S. officials privately make no attempt to conceal that they would like to withdraw the weapons and for NATO to move out of the Cold War.

Not only does the NPR retire the nuclear Tomahawk that supported NATO, there are subtle hints that the nuclear bombs may be withdrawn. The NPR reminds that even if the bombs were withdrawn from Europe, the United States will “retain the capability to forward-deploy U.S. nuclear weapons on tactical fighter-bombers (in the future, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter) and heavy bombers (the B-2 and B-52H).” In addition, the NPR promises, the United States will “continue to maintain and develop long-range strike capabilities that supplement U.S. forward military presence and strengthen regional deterrence.”

The subtle point, I think, is that forward deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe is not very suitable for today’s security challenges, that regional deterrence and reassurance of allies are better served by a new regional security architecture that relies less on nuclear weapons, and that there are plenty of other nuclear capabilities to provide the nuclear umbrella anyway. But none of those changes to U.S. extended deterrence capabilities will be made, the NPR promises, without close consultations with allies and partners.

So I don’t think it’s matter of if but when and how the remaining U.S. weapons will be withdrawn from Europe. The problem with additional gradual unilateral reductions is that it’s hard to cut much more without looking increasingly silly when arguing that the few that will remain are still essential for NATO.

Well aware of this dilemma, opponents of withdrawal have proposed linking further cuts to reductions in Russian tactical nuclear weapons; they know full well that such a link would means nothing will happen anytime soon.

But making further reductions conditioned on Russia reducing its non-strategic nuclear weapons seems insincere because NATO for the past two decades has been perfectly capable of and willing to reduce unilaterally without any demands on Russia. Insisting on reciprocity now, when NATO has been insisting for years that the weapons are not directed against Russia, seems like a step back to the 1980s and intended to shield the last weapons against withdrawal.

Another reason why it makes little sense to link further reductions to Russian reductions is that the improved conventional and missile defense capabilities that are required by the new, tailored, regional deterrence architecture likely will deepen Russian concerns about NATO conventional capabilities. Even though Russia’s non-strategic forces are expected to decline significantly during the next decade, this will probably increase the importance of the remaining weapons in Russian thinking even more.

Fortunately, none of this prevents a unilateral withdrawal of the remaining U.S. weapons from Europe. Indeed, it seems that the way forward is perhaps a two-step process beginning with ending the nuclear sharing mission followed by complete withdrawal a little later. Whatever the schedule is, the good news is that reducing the deployment in Europe is both consistent with NATO history and security interests.

Thank you.

U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Status and Issues

Hans M. Kristensen

Presentation toPax Christi Panel on Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Europe

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference, New York, May 12, 2010I’ve been asked to talk about the status of the deployment in Europe and what some of the implications are for NATO.

The 200 U.S. nuclear bombs currently deployed in Europe are a far cry from the peak of 7,300 tactical nuclear weapons in 1971, but comparing with the Cold War is no longer relevant; the issue is how the posture fits the security challenges of today. The current deployment is about as big as the entire Chinese arsenal, or nearly as much as India, Pakistan, and Israel have combined. That’s a lot for an arsenal that NATO says has no military mission.

Yet for an alliance that officially emphasizes the importance of continued and widespread deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, the past two decades have been somewhat of a contradiction: since 1993 when the withdrawal of ground-launched and naval weapons was completed, these “essential” bombs have been reduced from 700 to 200, the number of nuclear bases reduced from 14 to 6, and the number of countries participating in the NATO strike mission reduced from six to four countries that now appear to have serious doubts about continuing the mission. And burden sharing in NATO is actually not very widespread: out of NATO’s 28 members, only five (18 percent) have nuclear weapons on their territory, and only four of those (14 percent) have the strike mission. So nuclear burden sharing is the exception, not the rule, in NATO.

There are several issues that need to be addressed. The first is the mission. NATO is fond of saying that the forward deployment no longer has any military mission. It only serves as a symbol of the U.S. commitment to defend NATO, and without this forward symbol, so the argument goes, the U.S. security interest in Europe would weaken. Whether one agrees with this argument – and I for one believe it is absolutely nonsense – the last thing Europe should look to as the Atlantic glue is a deployment that the United States itself no longer thinks is important. There is a view forming back in Washington that it’s kind of silly for some of the NATO governments to continue to put so much emphasis on this deployment and you only have to look to the NPR report to see how much effort it makes to signal to Europe that extended deterrence and Article V do not depend on deploying nuclear bombs in Europe.

NATO is currently reviewing the nuclear mission, of which the forward deployment is a sub-issue. I think the deployment constrains the review and limits NATO’s ability think anew about the appropriate contribution of nuclear weapons to NATO security. No matter how the forward deployment has been adjusted and what one might otherwise think about the virtues of the deployment, it is at its core a Cold War posture.

Related to the mission review is the question of resources. The forward deployment requires special personnel, special equipment, special command and control, special inspections, special security arrangements, special emergency plans, special political and legal agreements, and special funding, all of which compete with conventional missions and place unnecessary burdens on people, equipment, and institutions. The weapons were withdrawn from Lakenheath and Ramstein partly because those bases needed to focus their mission on real-world contingencies. Those who insist that the deployment is still necessary need to demonstrate what the net benefit is to NATO.

The mission review is closely related to how the deployment affects relations with Russia and other potential adversaries. NATO has insisted for two decades that the weapons in Europe are not aimed at Russia or any country. That may or may not be true, but the deployment is frequently used by Russian officials as an excuse to reject constraints on their own non-strategic nuclear weapons. And Russian military planners will necessarily have to plan contingencies against potential NATO attacks with the weapons deployed in Europe. This ties NATO and Russia to a deterrence relationship that they don’t need to have, and that works against closer relations.

We now see some proposing that further reductions in the U.S. deployment should be linked to reductions in Russian non-strategic weapons. That would of course be one way to make sure the U.S. weapons are not withdrawn anytime soon, but making further reductions conditioned on Russia reducing its non-strategic nuclear weapons is misguided for several reasons. First, because NATO for the past two decades has been perfectly capable of and willing to reduce unilaterally without any demands on Russia. Second, the United States has unilaterally reduced its nonstrategic arsenal far more than Russia because these weapons are no longer seen as important to national security. Insisting on reciprocity now, when NATO has been insisting for years that the deployment is not linked to Russia, seems a step back that would give the European deployment an importance it doesn’t deserve and risk complicating prospects for Russian reductions.

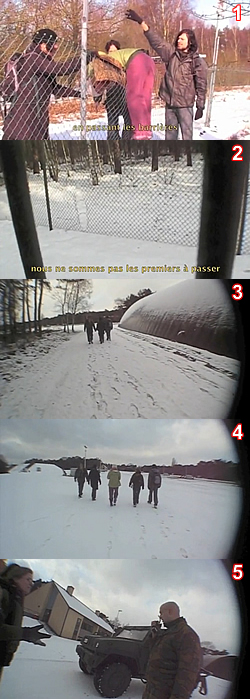

Then there is the issue of safety. This is more significant than people generally think. The 200 weapons are scattered in 87 aircraft shelters at six bases in five countries. Ten years ago, the U.S. Air Force discovered that weapons maintenance procedures at the shelters under specific conditions could lead to accidents with a nuclear yield. Two years ago, the Air Force Blue Ribbon Review determined that security at the host country bases did not meet U.S. security standards. And just a few months ago, peace activists at Kleine Brogel demonstrated loudly and clearly that despite extensive security arrangements unauthorized people can get deep into a nuclear base and very close to the weapons. The widespread deployment was designed to survive a Soviet attack, but in today’s world widespread deployment is out of sync with nuclear weapons storage in the age of extreme terrorism.

Finally there is the issue of NATO’s nonproliferation standard. The practice of equipping and training non-nuclear NPT signatories in NATO with U.S. nuclear weapons capabilities was largely tolerated by the NPT community during the Cold War. But this arrangement is untenable in an era where the focus is on nonproliferation because it muddles the message, creates double standards, and is – plain and simple – in contradiction with the intention of the NPT. It is not a standard that NATO or the United States should defend today. The nuclear sharing is simply not important enough to justify this contradiction.

—

The top of the new American administration supports a withdrawal from Europe. You might be surprised to hear that given Hillary Clinton’s statements in Tallinn last month and what some defense officials are saying inside. But those statements are, I think, part of a strategy intended to avoid triggering a backlash from some Eastern European NATO countries and Turkey that could lock NATO’s Strategic Concept into another two decades of nuclear status quo.

Not only does the NPR retire the nuclear Tomahawk that supported NATO, there are subtle hints that the bombs may be withdrawn. The NPR reminds that even if the nuclear bombs were withdrawn from Europe, the United States will “retain the capability to forward-deploy U.S. nuclear weapons on tactical fighter-bombers (in the future, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter) and heavy bombers (the B-2 and B-52H).” In addition, the NPR promises, the United States will “continue to maintain and develop long-range strike capabilities that supplement U.S. forward military presence and strengthen regional deterrence.”

The subtle message to NATO, I think, is that the Obama administration does not believe that forward deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe is necessary for today’s security challenges, that regional deterrence and reassurance of allies are better served by a new regional security architecture that relies less on nuclear weapons, and that there are plenty of other nuclear capabilities to provide the nuclear umbrella to the limited extent that that is necessary. Such a posture has been in effect in Northeast Asia since 1992, and many U.S. officials privately make no attempt to conceal that they would like to withdraw the weapons from Europe too and for NATO to move on.

So I don’t think it’s matter of if but when and in what form the U.S. weapons will be withdrawn from Europe. A way forward might be a two-step process beginning with ending the nuclear sharing mission followed by complete withdrawal a little later. Whatever the schedule is, the good news is that reducing the deployment in Europe is both consistent with NATO history and security interests and the views of the new American administration.

Thank you.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

“A Nuclear Weapons Free NATO”

|

| Imagine that: a nuclear weapons free NATO working for nuclear disarmament? |

By Hans M. Kristensen

While NATO struggles with whether and how it can discuss the future of nuclear weapons in the alliance, the Obama administration timidly avoids addressing the issue head on, and NGOs try to play government by proposing sensible steps such as consolidation and gradual reductions, three U.S. active duty military officers have taken the leap and written a thought-provoking and visionary article in American Diplomacy in which they argue that the United States should withdraw its nuclear weapons from Europe and NATO adopt a nuclear weapons-free policy.

The core of their proposal is for NATO to “talk the talk” and “walk the walk” by ending the Cold War nuclear structure of direct allied involvement in nuclear planning and leave potential nuclear missions in support of Article V to US, British, and French national nuclear capabilities outside of the NATO Command and Control architecture. NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group and SHAPE’s Nuclear Operations Branch would be disestablished and a Nuclear Weapons Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Group established in Brussels to lead the international effort of reduce and eventually eliminate nuclear weapons.

Now that’s what I call a vision!

Additional information: Kleine Brogel Nukes

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The Nuclear Posture Review

|

| The Nuclear Posture Review enshrines nuclear disarmament as a real goal for U.S. nuclear weapons policy for the first time. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

It’s finally here! Hot off the press after a three months delay. For the first time since the end of the Cold War, the United States has published a Nuclear Posture Review report.

Granted, it’s a sanitized version, but the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) contains strong language that commits the United States to work for nonproliferation. And for the first time, the goal of elimination of nuclear weapons is enshrined into the NPR.

By incorporating a broader range of policy issues in setting the nuclear posture, the review represents a break with the Bush administration’s NPR, which was more focused on military capabilities. As such, the new NPR is more a nuclear policy review than a nuclear posture review.

At the same time, the new NPR comes across as a surprisingly cautious document that recommends curtailing the U.S. nuclear posture further in the future but for now preserves many of the key nuclear weapons force structure and policy elements of the previous administration.

Proliferators and Peer Adversaries

The truly new in this NPR is that a good portion of it has very little to do with the U.S. nuclear posture and more to do with policies intended to curtail the spread of nuclear weapons to others. As such, this NPR has a much broader horizon than previous versions. A much needed update.

The NPR illustrates how proliferation has had and continues to have a real effect on U.S. nuclear weapons policy. This is most vivid in the sections dealing with the role of nuclear weapons and regional deterrence.

In the end, however, the NPR illustrates that proliferation is a side-chapter for the sizing and characteristics of the U.S. nuclear posture, which continues to be dominated by planning against Russia and China.

As such, it is in the regional mission that most of the change that President Obama has promised may eventually emerge.

Clarifying the Nuclear Carrot

The NPR adopts a much needed simplification and clarification of the U.S. negative security assurance, an important “carrot” intended to help persuade countries not to acquire nuclear weapons. This is not a new policy by any means, but the NPR surely clarifies it:

|

| The NPR clarifies and simplifies the “nuclear carrot” |

The “United States will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapons states that are party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and in compliance with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations.”

Compare that to the Cold War version most recently repeated by the Bush administration in 2002:

The United States “will not use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states parties to the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons [NPT], except in the case of an invasion or any other attack on the United States, its territories, its armed forces or other troops, its allies or on a state toward which it has a security commitment, carried out or sustained by such a non-nuclear weapon state in association or alliance with a nuclear weapon state.”

Oy ve! There were so many exemptions buried in the old version that it was hard to understand what it meant. The new version fixes that: sign and abide by the NPT and you’re covered!

Yet as soon as you begin thinking about how this policy would be applied in the real world, questions arise.

Take Iran, for example, a non-nuclear weapon state that has signed the NPT, but is not – how to say it – on the best terms with the regime. How much in breach of its obligations under the NPT does Iran have to be before the policy kicks in? In other words, at what point would the president decide to include or exclude Iran from the list of potential adversaries he orders the military to plan nuclear strikes against?

Likewise, the negative security assurance only relates to Iran’s nuclear status. But Iran is already a target for U.S. nuclear planning because of its chemical and biological weapons capabilities. And as the NPR makes clear, U.S. nuclear weapons continue to play a role in deterring chemical and biological weapons. So could a country that has signed the NPT and abide by its obligations still be a target because it has chemical and biological weapons? In other words, which part of the policy rules?

Reducing the Role of Nuclear Weapons?

President Obama pledged in his Prague speech last year that he would “reduce the role of nuclear weapons” to “put an end to Cold War thinking,” and reaffirmed in February this year that the “Nuclear Posture Review will reduce [the] role….”

At a first glance the NPR appears to reduce the role of nuclear weapons. The document states in the executive summary that, the “fundamental role of U.S. nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attack on the United States, our allies, and partners.” (They’ll probably have to add “U.S. forces” to that list.)

While most of the debate so far has focused on what “fundamental” means, I think the important part of that statement is the word “nuclear.” Because the two previous administrations used a broader role: to deter weapons of mass destruction attacks. Weapons of mass destruction (WMD) is a much broader category that includes nuclear, biological, chemical, and radiological weapons. Nuclear strike plans against regional adversaries armed with WMD were added to the strategic war plan in 2003.

Under the section “Reducing the Role of U.S. Nuclear Weapons” the NPR lists three overall conclusions about the role:

- The United States will continue to strengthen conventional capabilities and reduce the role of nuclear weapons in deterring non-nuclear attack, with the objective of making deterrence of nuclear attack on the United States or our allies and partners the sole purpose of U.S. nuclear weapons.

- The United States would only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defense the vital interests of the United States or its allies and partners.

- The United States will not use of threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapons states that are party to the NPT and in compliance with their nuclear proliferation obligations.

The “deter nuclear attack” and pursuit of “sole purpose” is clearly new language, and they would, if implemented, constitute a roll-back of the Clinton and Bush administrations’ policy of using nuclear weapons to deter all forms of WMD.

But a little further into the document, it soon becomes clear that the actual reduction in the nuclear mission – at least for now – is rather modest, if anything at all. In fact, it’s difficult to see why under the language used in this NPR, U.S. nuclear planning would not continue pretty much the way it is now.

|

| The NPR appears to continue nuclear planning against regional adversaries with weapons of mass destruction |

The NPR explicitly rejects the adoption of a “sole purpose” policy for now, and leaves it up to future presidents to possibly change the policy in that direction. The price for a “sole purpose” policy, it seems, is more conventional weapons.

Changes in the role of nuclear weapons are much harder to see when it comes to Russia and China, where the NPR appears to continue the Bush administration’s policies. The retention of the Triad and an upload capability seem explicitly tied to those scenarios. Indeed, the NPR bluntly states that “Russia’s nuclear force will remain a significant factor in determining how much and how fast we are prepared to reduce U.S. forces.”

The first test of how and when the role of U.S. nuclear weapons might be reduced will come in a few months when president Obama issues his first presidential directive with nuclear weapons planning guidance to the military. The U.S. nuclear war plan is currently based on NSPD-14 from June 2002.

Reducing the Number of Nuclear Weapons?

President Obama also pledged in the Prague speech that he would “reduce the number of nuclear weapons” to “put an end to Cold War thinking.”

The NPR force structure analysis was the basis for the New START limits of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads and 700 deployed strategic delivery vehicles. Those limits represent a reduction compared with previous limits set by the 1991 START and 2002 Moscow Treaty.

But, as I’ve said earlier, and president Obama acknowledged in his interview with the New York Times, the New START reduces the limit for how many warheads can be deployed but not the actual number of warheads in the arsenal.

Surprisingly, the NPR does not identify how the New START limits will be achieved. Potential areas for the reductions are: a retirement of two SSBNs from the nuclear mission; a cut of about 50-100 additional Minuteman III ICBMs; conversion of some of the B-52s to conventional-only aircraft.

The NPR continues the conversion of the ICBM force to single-warhead configuration. That decision implements a decision made by the 1994 NPR, but which the Bush administration modified to allow for a few ICBMs to continue to carry multiple warheads. They were not many, though, so the reduction in warheads from finishing the conversion will be modest, although a decision to reduce the number of ICBMs further would increase the reduction.

|

| The NPR and START “will not affect the number of deployed nuclear warheads on SSBNs” |

One apparent example of the effect of not counting bomber weapons under the START ceiling is the NPR decision that even a retirement of two SSBNs “will not affect the number of deployed nuclear warheads on SSBNs.”

The NPR does not clearly direct a reduction in the size of the total nuclear weapons stockpile, which currently contains about 5,000 warheads. The Bush administration reduced the stockpile by nearly 50 percent between 2004 and 2007, and announced an additional 12 percent reduction by 2012, leaving about 4,600 warheads.

A change might come from a reduction in the inventory of non-deployed warheads. The Bush administration’s decision in 2001 to retain a Responsive Force of reserve warheads that can be loaded back onto missiles and bombers if necessary received a lot of criticism for making a mockery of arms cuts. There are currently an estimated 2,500 active warheads in that hedge. The new NPR says that the U.S. will “significantly reduce” the size of the hedge, but that the United States will retain the ability to ‘upload’ some nuclear warheads as a technical hedge against any future problems with U.S. delivery systems or warheads, or as a result of a fundamental deterioration of the security environment.” Whether the reduction will happen unconditionally or be dependent on Congressional approval of new bomb factories is unclear, but it appears to depend on construction of the new facilities.

Overall, the NPR retains the Cold War force structure of nuclear weapons deployed on a Triad of delivery vehicles and concludes that, “the current alert posture of U.S. strategic forces – with heavy bombers off full-time alert, nearly all ICBMs on alert, and a significant number of SSBNs at sea at any given time – should be retained for the present.” President Obama’s campaign pledge to “work with Russia to take U.S. and Russian ballistic missiles off hair trigger alert” appears to have been put on hold.

No doubt, retaining a Cold War posture with only modest reductions and delaying decisions about where the cuts will fall will help win crucial votes in the Senate for ratification of the New START treaty and the CTBT.

With the modest reductions recommended by this NPR, the report states that president Obama has already directed a review of future reductions of nuclear weapons. But potential reductions are conditioned on further strengthening regional deterrence, maintain strategic stability with Russia and China, provide nuclear umbrellas over allies, and building new bomb making factories.

Extended Deterrence and Nuclear Weapons

The NPR does a good job of underscoring that extended deterrence is much more than nuclear weapons. There has been an unfortunate tendency in the public debate to equate extended deterrence for NATO allies with a need to forward deploy tactical nuclear weapons in Europe.

Unfortunately, the NPR does not recommend reducing or withdrawing the approximately 200 nuclear bombs currently deployed at six bases in five European countries. Instead, it says the U.S. “will consult with our allies regarding the future basing of nuclear weapons in Europe, and is committed to making consensus decisions through NATO processes.” This is probably intended to formally leave a decision to NATO’s Strategic Review process scheduled for completion in November.

For a document that emphasizes nonproliferation and adherence to NPT obligations, the description of “NATO’s unique nuclear sharing arrangements under which non-nuclear members participate in nuclear planning and possess specially configured aircraft capable of delivering nuclear weapons” does come across as somewhat out of sync. Training and equipping non-nuclear countries to deliver nuclear weapons is not a standard the Obama administration should support.

|

| The NPR recommends production of a new nuclear fighter (F-35) with a new nuclear weapon (B61-12) |

Regardless of what NATO might decide, the NPR concludes that some of the Joint Strike Fighters (F-35) will be equipped to deliver the new B61-12 nuclear bomb to “retain the capability to forward-deploy non-strategic nuclear weapons in support of its Alliance commitments.” So even if NATO decides the weapons can be withdrawn, a tactical nuclear fighter capability will remain.

Nuclear Tomahawk sea-launched land-attack cruise missiles (TLAM/Ns) that previously supported extended deterrence of NATO and Pacific allies will be retired and the NPR correctly concludes that the remaining nuclear forces provide amble capability to both signal and deter. This brushes aside warnings from the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission and others. As for the future role of nuclear weapons in regional scenarios, the NPR states:

“U.S. nuclear weapons will play a role in the deterrence of regional states so long as those states have nuclear weapons, but the decisions taken in the NPR, BMDR, and QDR reflect the U.S. desire to increase reliance on non-nuclear means to accomplish our objectives of deterring such states and reassuring our allies and partners.”

Warhead Dismantlement and Production

There are currently about 4,500 retired nuclear warheads in queue to be dismantled. At the low dismantlement rate currently used (200-400 warheads per year) it will take more than decade to dismantle the backlog. More retired warheads will come from the decision to “significantly reduce” the hedge, further extending the timeline.

Dismantlements compete with warhead maintenance and production for limited capacity at the Pantex Plant in Texas. The NPR recommends full-rate production of the W76-1 warhead, followed by the B61-12, and possibly the W78.

These programs are described as extending the lives of existing warhead designs, although modifications can be significant. The NPR pledges that

“The United States will not develop new nuclear warheads. Life Extension Programs will use only nuclear components based on previously tested designs, and will not support new military missions or provide for new military capabilities.”

This policy leaves the door open for extensive modifications of nuclear warheads – it would even permit production of the Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW), although officials insist that program is “dead” – and the NPR states that the full range of warhead work will be considered: refurbishment of existing warheads, reuse of nuclear components from different warheads, and replacement of nuclear components.

Mindful of how controversial a decision to build replacement warheads is, the NPR assures that decisions to modify warheads “will give strong preference to options for refurbishment or reuse” rather than replacement.

Conclusion

The NPR elevates nonproliferation to the same level in U.S. nuclear policy as the nuclear weapons posture. It enshrines eventual nuclear disarmament as a central goal for U.S. nuclear weapons policy for the first time, and it sets the stage for possible future reductions in the role and numbers of nuclear weapons.

For those of us who looked forward to the NPR to clearly and significantly reduce the role and numbers of nuclear weapons, however, the report is a disappointment. President Obama has cautioned that his vision of a nuclear free world might not happen in our lifetime and the NPR shows why he might be right.

The options for how to reduce nuclear weapons are vague in the NPR but probably buried in the classified version. Some of those options, including how deep many reserve warheads will be retired, and how many ICBMs, SSBNs and bombers will be cut, will be made in the months and years ahead.

Above all, the NPR is a pragmatic policy document that combines maintaining a strong nuclear arsenal, modest reductions in nuclear weapons, nonproliferation efforts, and a vision of a world free of nuclear weapons to position the Obama administration for the April Nuclear Summit, the May NPT Review Conference, and ratification of the New START treaty and Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty.

Successful outcomes of those milestones are essential for the prospects of future reductions in the role and number of nuclear weapons, as is honest critique of when initiatives don’t go far enough.

There is a risk here, of course, that after having galvanized international hopes and expectations about dramatic changes to decisively move the world toward nuclear disarmament, the modest NPR instead will be seen by the international community as a sign that Cold Warriors managed to block much of president Obama’s vision.

Hopefully that won’t happen, but there sure is a lot of work ahead.

Further Reading: 1994 NPR | 2001 NPR

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Posture Review to Reduce Regional Role of Nuclear Weapons

|

| The Quadrennial Deference Review forecasts reduction in regional role of nuclear weapons. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

A little-noticed section of the Quadrennial Defense Review recently published by the Pentagon suggests that that the Obama administration’s forthcoming Nuclear Posture Review will reduce the role of nuclear weapons in regional scenarios.

The apparent reduction coincides with a proposal by five NATO allies to withdraw the remaining U.S. tactical nuclear weapons from Europe.

Another casualty appears to be a decision to retire the nuclear-armed Tomahawk sea-launched land-attack cruise missile, despite the efforts of the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission.

New Regional Deterrence Architectures

Earlier this month President Barack Obama told the Global Zero Summit in Paris that the NPR “will reduce [the] role and number of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” The reduction in numbers will initially be achieved by the START follow-on treaty soon to be signed with Russia, but where the reduction in the role would occur has been unclear.

Yet the Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) published earlier this month strongly suggests that the reduction in the role will occur in the regional part of the nuclear posture:

“To reinforce U.S. commitments to our allies and partners, we will consult closely with them on new, tailored, regional deterrence architectures that combine our forward presence, relevant conventional capabilities (including missile defenses), and continued commitment to extend our nuclear deterrent. These regional architectures and new capabilities, as detailed in the Ballistic Missile Defense Review and the forthcoming Nuclear Posture Review, make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” (emphasis added)

There are two parts (with some overlap) to the regional mission: the role of nuclear weapons against regional adversaries (North Korea, Iran, and Syria); and the role of nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

Rumors have circulated for long that the administration will remove the requirement to plan nuclear strikes against chemical and biological weapons from the mission; to limit the role to deterring nuclear attacks. Doing so would remove Iran, Syria and others as nuclear targets unless they acquire nuclear weapons. A broader regional change could involve leaving regional deterrence against smaller regional adversaries (including North Korea) to non-nuclear forces and focus the nuclear mission on the large nuclear adversaries (Russia and China).

An immediate consequence of the new architecture appears to be a decision to retire the nuclear Tomahawk sea-launched land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N). According to a report by Kyodo News (see also report by Daily Yomiuri), Washington has informally told the Japanese government that it intends to retire the weapon. The 2009 Congressional Strategic Posture Commission report had recommended retaining the weapons, but neither the Pentagon nor the Japanese government apparently agreed.

| Nuclear Tomahawk To Be Retired |

|

| The Obama administration has informally told the Japanese government that the nuclear Tomahawk cruise missile will be retired. The retirement appears to be part of a new regional deterrence architecture that enables a reduction of the role of nuclear weapons. |

.

A Nuclear Withdrawal From Europe?

The other part of the regional mission concerns the deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe, where the U.S. Air Force currently deploys 150-200 nuclear bombs at six bases in five NATO countries. Some of the TLAM/Ns also are earmarked for support of NATO, but are stored on land in the United States. The weapons are the last remnant of the Cold War deployment of thousands of tactical nuclear weapons to deter a Soviet attack on Europe. Similar deployments in the Pacific ended two decades ago and pressure has been building for NATO to finally end the Cold War.

Three of the five NATO countries that currently host the U.S. nuclear bombs on their territories are expected to ask for the weapons to be withdrawn, according to a report by AFP.

A spokesperson for the Belgian Prime Minister said that Belgium, German, and the Netherlands, together with Norway and Luxemburg, in the coming weeks will formally propose within NATO that “that nuclear arms on European soil belonging to other NATO member states are removed.”

Presumably, some coordination with Washington has taken place. Otherwise, if the NPR does not recommend a withdrawal from Europe, the five countries’ initiative will from the outset be in conflict with the Obama administration’s nuclear policy, which NATO likely will follow.

The European initiative would help the Obama administration justify a decision to withdraw the weapons from Europe by demonstrating that key NATO allies no longer see a need for the deployment. Extended nuclear deterrence would continue, as the QDR language underscores, but with long-range strategic weapons as it is done in the Pacific.

Other than the forthcoming NPR, the political context for the European initiative is NATO’s ongoing review of its Strategic Concept, scheduled for completion in November. The Obama administration might not want to preempt that review, so an alternative could be that the NPR concludes that the U.S. sees no need for the continued deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe but leaves it up to NATO’s new Strategic Concept to make the formal decision. In that case, the initiative by the five NATO countries could serve to formally start that process within NATO. (see comments by U.S. NATO Ambassador Ivo Daalder)

Whether that means a complete withdrawal from Europe now, a decision to end the NATO strike portion (a controversial Cold War mission that assigns nuclear weapons for delivery by Belgian, Dutch, German, and Italian aircraft) and consolidating the remaining weapons at one or two U.S. bases in Europe, or something else remains to be seen. But a reduction rather than complete withdrawal would achieve little.

Heated Debate

The debate over the deployment in Europe is in full swing, recently triggered by the new German government’s decision to work for a withdrawal.

A paper by Franklin Miller, a former top-Pentagon official in charge of the deployment in Europe, and former NATO head George Robertson calling the German position dangerous was rejected as old-fashioned thinking on the New York Times’ opinion pages by Wolfgang Ischinger, Germany’s former foreign deputy foreign minister and chairman of the Munich Security Conference, and Ulrich Weisser, a former director of the policy planning staff of the German defense minister.

And suggestions by some supporters of continued deployment that Eastern European countries oppose withdrawal have suffered recently with Poland’s Prime Minister Radek Sikorski calling for the reduction and elimination of non-strategic nuclear weapons, and a report from the Polish Institute of International Affairs in March 2009 that appeared to question the need for the nuclear deployment.

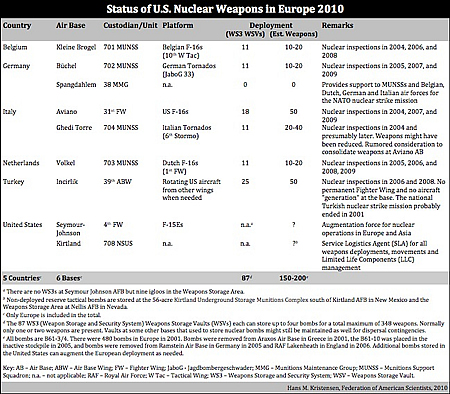

Status of U.S. Nuclear Deployment in Europe

The U.S. Air Force currently deploys an estimated 150-200 U.S. nuclear bombs in 87 aircraft shelters at six bases in five countries, a reduction from approximately 480 bombs in 2001. The breakdown by country looks like this:

|

| Click image to download larger pdf-version. |

.

Additional Background: History of U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Kleine Brogel Nukes: Not There, Over Here!

|

| The U.S. Air Force’s 701 Munitions Support Squadron at Kleine Brogel Air Base must protect and handle the nuclear weapons at the base. |

An astounding statement by a Belgian defense official has pointed an unexpected light on the apparent location of nuclear weapons at the Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium.

After a group of peace activists climbed the base fence and made their way deep into an area assumed to store nuclear weapons, Ingrid Baeck, a chief spokesperson for the Belgian Ministry of Defense, bluntly told Stars and Stripes: “I can assure you these people never, ever got anywhere near a sensitive area. They are talking nonsense….It was an empty bunker, a shelter,” she said and added: “When you get close to sensitive areas, then it’s another cup of tea.”

Baeck did not go so far as to explicitly confirm or deny if there were nuclear weapons on the base, but the Belgium Ministry of Defense’s mission statement for the 10th Tactical Wing clearly shows that it has a nuclear mission (see Figure 1).

| Figure 1: Belgian 10th Tactical Wing Mission |

|

| The Belgian Ministry of Defense’s mission statement for the 10th Tactical Wing (10 W Tac) at Kleine Brogel clearly lists a nuclear mission. Emphasis added. |

.

Shelter Searching

It is unclear whether Baeck as a spokesperson actually knows where the weapons are stored or if “sensitive area” only refers to the particular shelter the activists reached. But her statement that the activists “ever got anywhere near a sensitive area” inadvertently redirects the attention to the western area of the base.

Kleine Brogel has 26 Protective Aircraft Shelters (PAS) located in three clusters: Area 1 at the western part of the base with 11 shelters; Area 2 at the center of the base also with 11 shelters; and Area 3 at the eastern end of the base with four shelters (see Figure 2).

| Figure 2: Nuclear Weapons Storage Areas |

|

| Estimated locations for nuclear weapons at Kleine Brogel Air Base have changed over the years. Click image for large version. |

.

During the Cold War, nuclear weapons were stored in the Weapons Storage Area northeast of the base, while aircraft loaded with nuclear weapons stood alert in the shelters in Area 3.

Area 2 has long been the suspected nuclear weapons storage area, given its 11 shelters, pronounced fencing, and separation from the outer base perimeter. This is the area the activists managed to penetrate on January 31st.

Baeck’s statement appears to draw the attention to Area 1 at the western end of the base where 11 shelters are clustered. It also has an additional fence perimeter that appears to have been improved since 2006, but the gates were open on a satellite image dated April 8, 2007. Moreover, the area is close to the outer base fence, with the busy N748 highway only 225 feet (68 meters) from one shelter and another shelter only 134 feet (40 meters) from a residential neighborhood. Jeffrey L also has an interesting photo interpretation.

Whether the nuclear shelters necessarily have to be in one cluster inside the same perimeter is unknown, although safety and management issues seem to suggest so.

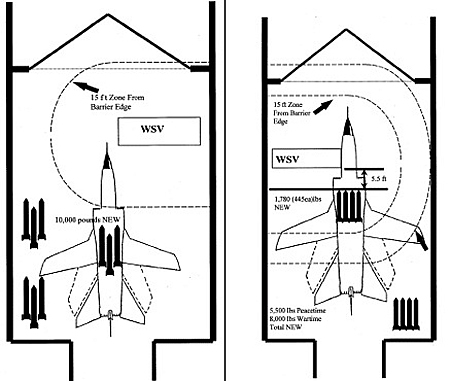

The Weapons Security and Storage System (WS3)

Only 11 of the 26 Protective Aircraft Shelters at Kleine Brogel are equipped with the Weapons Storage Security System (WS3), a nuclear weapons storage system unique to Europe. The system at Kleine Brogel was completed in 1992.

The mechanical part of the WS3 includes a Weapons Storage Vault (WSV), a reinforced concrete foundation and a steel structure recessed into the floor of the shelter. The vault platform can be elevated out of the concrete foundation by means of an elevator drive system to provide access to the weapons in two stages or levels, or can be lowered into the floor to provide protection and security for the weapons. The floor slab is approximately 16 inches (40 cm) thick. Sensors to detect intrusion attempts are embedded in the concrete vault body.

Each of the 11 vaults can store up to four B61 bombs, but normally contains only one or two for a total of 10-20 bombs currently at Kleine Brogel.

Location of the vault inside the shelter depends on the size of the shelter and the proximity of conventional weapons storage racks. Two layouts are in use (see Figure 3), and the vaults at Kleine Brogel are the smaller located at the front-left end of the shelter.

| Figure 3: Weapons Storage Vaul Locations |

|

| The location of the underground Weapons Storage Vault depends on the size of the aircraft shelter. Kleine Brogel shelters use the right-hand layout. |

.

The vaults are rarely visible on photos from outside the shelters, but in this unique photo (see Figure 4) taken at nearby Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands in 2009 the outline of the vault can be seen in the front-left corner (right in the picture) of the shelter.

| Figure 4: External View of Munitions Storage Vault |

|

| A vault cover is visible inside this shelter at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands. The picture of the specially painted F-16 (no. J-015) was taken during a pilot ceremony in 2009. Reprinted with permission. Original photo at Touchdown Aviation. |

.

The vault can be elevated in two stages, halfway to provide access to the top rack, or fully to provide access to the lower rack as well. An example of halfway elevation is the photo below showing the command of U.S. Air Forces in Europe, General Roger Brady, receiving a briefing next to a vault at Volkel Air Base in June 2008 (see Figure 5) (he also visited Kleine Brogel). The visits happened shortly after the Blue Ribbon Review report concluded that “most sites” storing nuclear weapons in Europe did not meet DOD security standards.

| Figure 5: Halfway Elevation of Weapons Storage Vault |

|

| This picture, taken inside a shelter at Volkel Air Base, shows Gen. Grady receiving a briefing from a member of the 703rd MUNSS. The vault is halfway raised showing one B61 bomb, with the lower bomb rack hidden below the floor level. |

.