NATO’s Warsaw Summit, and More from CRS

The July 8-9 NATO summit meeting in Warsaw, Poland, is previewed in a new report from the Congressional Research Service.

“Among other things, NATO leaders are expected to announce the rotational deployment of 4,000 troops to Poland and the three Baltic states, an expanded training mission for Iraqi soldiers, and additional NATO support for Afghanistan and Ukraine. NATO leaders will also assess member state progress in implementing defense spending and capabilities development commitments, a key U.S. priority. Finally, NATO is expected to formally invite Montenegro to become the 29th member of the alliance,” the report said.

The new report includes data on alliance defense spending and defense spending by individual NATO member states. See NATO’s Warsaw Summit: In Brief, June 30, 2016.

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

“Right-Sizing” the National Security Council Staff?, CRS Insight, June 30, 2016

Diversity, Inclusion, and Equal Opportunity in the Armed Services: Background and Issues for Congress, updated July 1, 2016

Sanctuary Jurisdictions and Criminal Aliens: In Brief, updated July 1, 2016

Brazil in Crisis, CRS Insight, updated July 6, 2016

State Voter Identification Requirements: Analysis, Legal Issues, and Policy Considerations, updated July 5, 2016

Derivatives: Introduction and Legislation in the 114th Congress, July 1, 2016

Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges, updated July 1, 2016

Military Benefits for Former Spouses: Legislation and Policy Issues, updated July 1, 2016

The Freedom of Information Act Turns Fifty & Is Revised, CRS Legal Sidebar, July 1, 2016

Questions About The Nuclear Cruise Missile Mission

During a Senate Appropriations Committee hearing on March 16, Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), the ranking member of the committee, said that U.S. Strategic Command had failed to convince her that the United States needs to develop a new nuclear air-launched cruise missile; the LRSO (Long-Range Standoff missile).

“I recently met with Admiral Haney, the head of Strategic Command regarding the new nuclear cruise missile and its refurbished warhead. I came away unconvinced of the need for this weapon. The so-called improvements to this weapon seemed to be designed candidly to make it more usable, to help us fight and win a limited nuclear war. I find that a shocking concept. I think this is really unthinkable, especially when we hold conventional weapons superiority, which can meet adversaries’ efforts to escalate a conflict.”

Feinstein made her statement only a few hours after Air Force Secretary Deborah James had told the House Armed Services Committee on the other side of the Capitol that the LRSO will be capable of “destroying otherwise inaccessible targets in any zone of conflict.”

Lets ignore for a moment that the justification used for most nuclear and advanced conventional weapons also is to destroy otherwise inaccessible targets, what are actually the unique LRSO targets? In theory the missile could be used against anything that is within range but that is not good enough to justify spending $20-$30 billion.

So Air Force officials have portrayed the LRSO as a unique weapon that can get in where nothing else can. The mission they describe sounds very much like the role tactical nuclear weapons played during the Cold War: “I can make holes and gaps” in air defenses, then Air Force Global Strike Command commander Lieutenant General Stephen Wilson explained in 2014, “to allow a penetrating bomber to get in.”

And last week, shortly before Admiral Haney failed to convince Sen. Feinstein, EUCOM commander General Philip Breedlove added more details about what they want to use the nuclear LRSO to blow up:

“One of the biggest keys to being able to break anti-access area denial [A2AD] is the ability to penetrate the air defenses so that we can get close to not only destroy the air defenses but to destroy the coastal defense cruise missiles and the land attack missiles which are the three elements of an A2AD environment. One of the primary and very important tools to busting that A2AD environment is a fifth generation ability to penetrate. In the LRSB you will have a platform and weapons that can penetrate.” (Emphasis added.)

Those A2/AD targets would include Russian S-400 air-defense, Russian Bastion-P coastal defense, and Chinese DF-10A land-attack missile launchers (see images).

Judging from Sen. Feinstein’s conclusion that the LRSO seems “designed candidly to make it more usable, to help us fight and win a limited nuclear war,” Admiral Haney probably described similar LRSO targets as Lt. Gen. Wilson and Gen. Breedlove.

After hearing these “shocking” descriptions of the LRSO’s warfighting mission, Senator Feinstein asked NNSA’s Gen. Klotz if he could do a better job in persuading her about the need for the new nuclear cruise missile:

Sen. Feinstein: “So maybe you can succeed where Admiral Haney did not. Let me ask you this question: Why do we need a new nuclear cruise missile?”

Gen. Klotz: “My sense at the time, and it still is the case, is that the existing cruise missile, the air-launched cruise missile, is getting rather long in the tooth with the issues that are associated with an aging weapon system. It was first deployed in 1982. And therefore it is well past it service life. In the meantime, as you know from your work on the intelligence committee, there has been an increase in the sophistication and capabilities as well as proliferation of sophisticated air- and missile-defenses around the world. Therefore the ability of the cruise missile to pose the deterrent capability, the capability that is necessary to deter, is under question. Therefore, just based on the ageing and the changing nature of the threat we need to replace a system we’ve had, again, since the early 1980s with an updated variant….I guess I didn’t convince you any more than the Admiral did.”

Sen. Feinstein: “No you didn’t convince me. Because this just ratchets up warfare and ratchets up deaths. Even if you go to a low kiloton of six or seven it is a huge weapon. And I thought there was a certain morality that we should have with respect to these weapons. If it’s really mutual deterrence, I don’t see how this does anything other…it’s like the drone. The drone has been invented. It’s been armed. Now every county wants one. So they get more and more sophisticated. To do this with nuclear weapons, I think, is awful.”

Conclusion and Recommendations

Senator Feinstein has raised some important questions about the scope of nuclear strategy. How useful should nuclear weapons be and for what type of scenarios?

Proponents of the LRSO do not seem to question (or discuss) the implications of developing a nuclear cruise missile intended for shooting holes in air- and coastal-defense systems. Their mindset seems to be that anything that can be used to “bust the A2AD environment” – even a nuclear weapon – must be good for deterrence and therefore also for security and stability.

While a decision to authorize use of nuclear weapons would be difficult for any president, the planning for the potential use does not seem to be nearly as constrained. Indeed, the nuclear LRSO anti-A2AD mission that defense officials describe raises some serious questions about how soon in a conflict nuclear weapons might be used.

Since A2AD systems would likely be some of the first targets to be attacked in a war, a nuclear LRSO anti-A2AD mission appears to move nuclear use to the forefront of a conflict instead of keeping nuclear weapons in the background as a last resort where they belong.

And the nuclear LRSO anti-A2AD mission sounds eerily similar to the outrageous threats that Russian officials have made over the past several years to use nuclear weapons against NATO missile defense systems – threats that NATO and US officials have condemned. Of course, they don’t brandish the nuclear LRSO anti-A2AD mission as a threat – they call it deterrence and reassurance.

Nor do LRSO proponents seem to ask questions about redundancy and which types of weapons are most useful or needed for the anti-A2AD mission. The A2AD targets that the military officials describe are not “otherwise inaccessible targets,” as suggested by Secretary James, but are already being held at risk with conventional cruise missiles such as the Air Force’s JASSM-ER (extended range Joint Air-to-Surface Missile) and the navy’s Tactical Tomahawk, as well as with other nuclear weapons. The Air Force doesn’t have endless resources but must prioritize weapon systems.

Gen. Klotz defended the LRSO as if it were a choice between having a nuclear deterrent or not. But, of course, even without a nuclear LRSO, US stealth bombers will still be armed with the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb and the US nuclear deterrent will still include land- and sea-based long-range ballistic missiles as well as F-35A stealthy fighter-bombers also armed with the B61-12.

The White House needs to rein in the nuclear warfighters and strategists to ensure that US nuclear strategy and modernization plans are better in tune with US policy to “reduce the role of nuclear weapons in deterring non-nuclear attacks” and enable non-nuclear weapons to “take on a greater share of the deterrence burden.” Canceling the nuclear LRSO would be a good start.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

RAND Report Questions Nuclear Role In Defending Baltic States

By Hans M. Kristensen

The RAND Corporation has published an interesting new report on how NATO would defend the Baltic States against a Russian attack.

Without spending much time explaining why Russia would launch a military attack against the Baltic States in the first place – the report simply declares “the next [after Ukraine] most likely targets for an attempted Russian coercion are the Baltic Republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania” – the report contains some surprising (to some) observations about the limitations of nuclear weapons in the real world (by that I mean not in the heads of strategists and theorists).

The central nuclear observation of the report is that NATO nuclear forces do not have much credibility in protecting the Baltic States against a Russian attack.

That conclusion is, to say the least, interesting given the extent to which some analysts and former/current officials have been arguing that NATO/US need to have more/better limited regional nuclear options to counter Russia in Europe.

The report is very timely because the NATO Summit in Warsaw in six months will decide on additional responses to Russian aggression. Unfortunately, some of the decisions might increase the role or readiness of nuclear weapons in Europe.

Limits of Nuclear Weapons

The RAND report contains important conclusions about the role that nuclear weapons could play in deterring and repelling a Russian attack on the Baltic States. Here are the relevant nuclear-related excerpts from the report:

“Any counteroffensive would also be fraught with severe escalatory risks. If the Crimea experience can be taken as a precedent, Moscow could move rapidly to formally annex the occupied territories to Russia. NATO clearly would not recognize the legitimacy of such a gambit, but from Russia’s perspective it would at least nominally bring them under Moscow’s nuclear umbrella. By turning a NATO counterattack aimed at liberating the Baltic republics into an “invasion” of “Russia,” Moscow could generate unpredictable but clearly dangerous escalatory dynamics.”

[…]

“The second option would be for NATO to turn the escalatory tables, taking a page from its Cold War doctrine of “massive retaliation,” and threaten Moscow with a nuclear response if it did not withdraw from the territory it had occupied. This option was a core element of the Alliance’s strategy against the Warsaw Pact for the duration of the latter’s existence and could certainly be called on once again in these circumstances.

The deterrent impact of such a threat draws power from the implicit risk of igniting an escalatory spiral that swiftly reaches the level of nuclear exchanges between the Russian and U.S. homelands. Unfortunately, once deterrence has failed—which would clearly be the case once Russia had crossed the Rubicon of attacking NATO member states—that same risk would tend to greatly undermine its credibility, since it may seem highly unlikely to Moscow that the United States would be willing to exchange New York for Riga. Coupled with the general direction of U.S. defense policy, which has been to de-emphasize the value of nuclear weapons, and the likely unwillingness of NATO’s European members, especially the Baltic states themselves, to see their continent or countries turned into a nuclear battlefield, this lack of believability makes this alternative both unlikely and unpalatable.”

[…]

“We did not portray nuclear use in any of our games, although we did explore the effects of various kinds of constraints on each side’s operations intended to represent limitations that might be imposed by national or alliance political leaderships anxious to avoid setting off escalatory spirals.”

[…]

“Other options have been discussed to enhance NATO’s deterrent posture without significantly increasing its conventional force deployments. For example, NATO could rely on an increased availability and reliance on tactical and theater nuclear weapons. However, as recollections of the endless Cold War debates about the viability of nuclear threats to deter conventional aggression by a power that itself has a plethora of nuclear arms should remind us, this approach has issues with credibility similar to those already discussed with regard to the massive retaliation option in response to a Russian attack.”

Even So…

Not surprisingly, some analysts and former officials (even some current officials) are busy arguing – even lobbying for – that NATO and the United States need more tailored nuclear capabilities to be able to deter and, if necessary, respond to precisely the type of scenario the RAND study had doubts about.

There’s no doubt that Vladimir Putin’s escapades are creating security concerns in the Baltic States and NATO. The invasion of Ukraine, increased military operations, direct nuclear threats, and a host of less visible activities effectively have killed the trust between Russia and NATO. Relations have deteriorated to an officially adversarial and counter-responsive climate. It is in this atmosphere that analysts and nuclear hardliners are trying to understand how it affects nuclear weapons policy.

Hardliners are convinced that Russia has increased reliance on nuclear weapons in a whole new way that envisions first-use of nuclear weapons. One former official who helped shape the George W. Bush administration’s nuclear policy recently warned that Russia “seeks to prevent any significant collective Western defensive opposition by threatening limited nuclear first-use in response,” and that the Russian threat to use nuclear weapons first “is a new reality more dangerous than the Cold War.” (Emphasis added.)

That is probably a bit over the top. As for the claim that Russia is “pursuing” low-yield nuclear weapons to “make its first-use threat credible,” that rumor dates back to a number of articles in Russian media in the 1990s. Those rumors followed reports in the United States in 1993 that the Clinton administration was considering low-yield nuclear weapons – even “micro-nukes.” The Bush administration in the 2000s pursued pre-emptive nuclear strike scenarios and advanced-concept nuclear weapons for tailored use. Although Congress rejected these plans, some of the ideas seem to have influenced Russian nuclear thinking.

The US Air Force plans to deploy the new F-35A with the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb in Europe from 2024. The B61-12 will be more accurate than current bombs and appears to have earth-penetration capability.

Now we’re again hearing proposals from some analysts that the United States should develop a “measured response” strategy that includes “discriminate nuclear options at all rungs of the nuclear escalation ladder” to ensure that “there are no gaps in U.S. nuclear response options that would prevent it from retaliating proportionately to any employment of a nuclear weapon against the United States and its allies.” This would require “low-yield, accurate, special-effects options that can respond proportionately at the lower end of the nuclear continuum.”

It is easy to get spooked by public statements and led astray by entangled logic and worst-case scenarios that spin into claims and recommendations that may be based on misunderstood or exaggerated information. It would be more interesting and beneficial to the public debate to hear what the U.S. Intelligence Community has concluded Russia has developed and what is new and different in Russian nuclear strategy today.

A Better Strategy

Fortunately, Russia’s general military capabilities – although important – are so limited that the RAND study concludes that for NATO to be able to counter a Russian attack on the Baltic States “does not appear to require a Herculean effort.”

The LRSO, not yet developed, could pay for 10 years of real-world protection of the Baltic States.

Instead, the report concludes that a NATO force of about seven brigades, including three heavy armored brigades – adequately supported by airpower, land-based fires, and other enablers on the ground and ready to fight at the onset of hostilities – might prevent such an outcome.

NATO has already created a conventional Spearhead Force brigade of about 5,000 troops. Seven brigades of that size would include about 35,000 troops.

Creating and maintaining such a force, RAND estimates, might cost on the order of $2.7 billion per year.

Put in perspective, the $30 billion the Pentagon plans to spend on a new nuclear air-launched cruise missile (LRSO) that is not needed could buy NATO more a decade worth of real protection of the Baltic States.

Guess what would help the Baltic States the most.

Background: Rand Report

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Declassified: US Nuclear Weapons At Sea

ASROC nuclear test, 1962

Remember during the Cold War when US Navy warships and attack submarines sailed the World’s oceans bristling with nuclear weapons and routinely violated non-nuclear countries’ bans against nuclear weapons on their territories in peacetime?

The weapons were onboard ballistic missile submarines, attack submarines, aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers, destroyers, frigates and supply ships. The weapons were brought along on naval exercises, spy missions, freedom of navigation demonstrations and port visits.

Sometimes the vessels they were on collided, ran aground, caught fire, or sank.

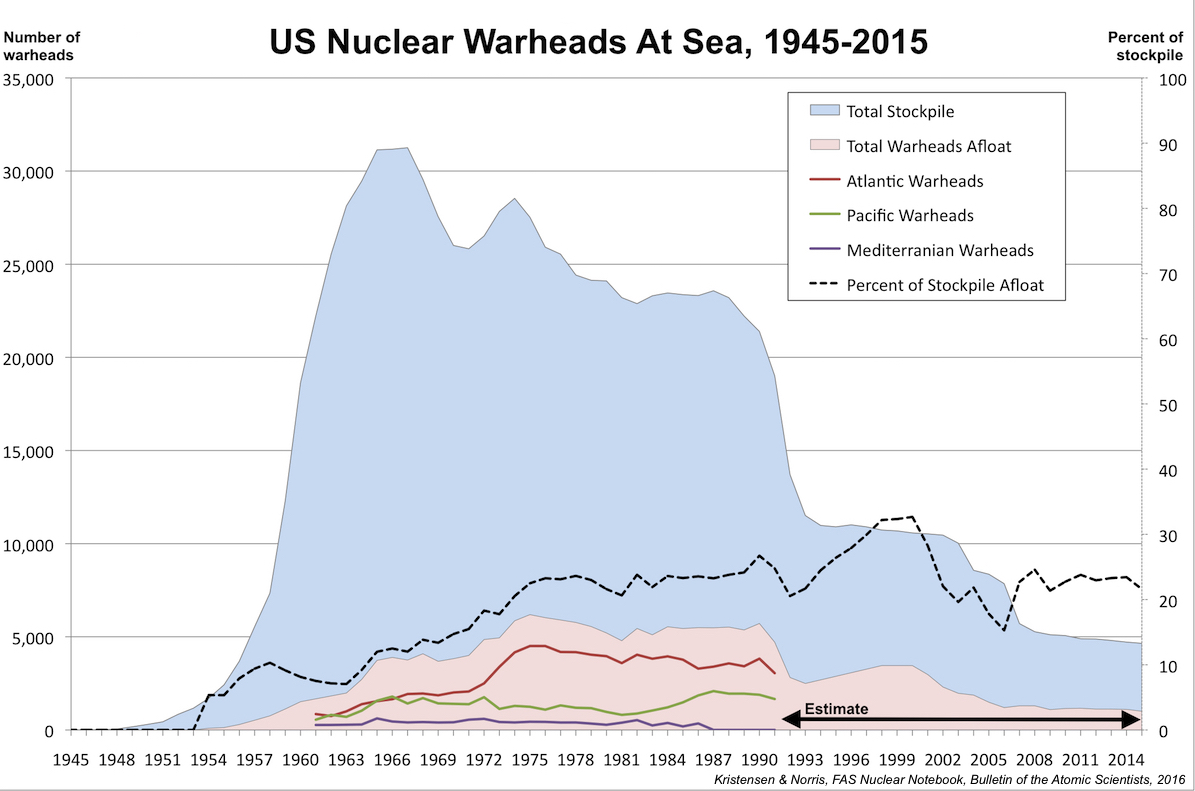

Not many remember today. But now the Pentagon has declassified how many nuclear weapons they actually deployed in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Mediterranean. In our latest FAS Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists we review this unique new set of de-classified Cold War nuclear history.

The Numbers

The declassified documents show that the United States during much of the 1970s and the 1980s deployed about a quarter of its entire nuclear weapons stockpile at sea. The all-time high was in 1975 when 6,191 weapons were afloat, but even in 1990, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, there were 5,716 weapons at sea. That’s more nuclear weapons than the size of the entire US nuclear stockpile today.

The declassified data provides detailed breakdowns for weapons in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Mediterranean for the 30-year period between 1961 and 1991. Prior to 1961 only totals are provided. Except for three years (1962, 1965 and 1966), most weapons were always deployed in the Atlantic, a reflection of the focus on defending NATO against the Soviet Union. When adding the weapons in the Mediterranean, the Euro-centric nature of the US nuclear posture during the Cold War becomes even more striking. The number of weapons deployed in the Pacific peaked much later, in 1987, at 2,085 weapons.

The declassified numbers end in 1991 with the offloading of non-strategic naval nuclear weapons from US Navy vessels. After that only strategic missile submarines (SSBNs) have continued to deploy with nuclear weapons onboard. Those numbers are still secret.

In the table above we have incorporated our estimates for the number of nuclear warhead deployed on US ballistic missile submarines since 1991. Those estimates show that afloat weapons increased during the 1990s as more Ohio-class SSBNs entered the fleet.

Because the total stockpile decreased significantly in the early 1990s, the percentage of it that was deployed at sea grew until it reached an all-time high of nearly 33 percent in 2000. Retirement of four SSBNs, changes to strategic war plans, and the effect of arms control agreements have since reduced the number of nuclear weapons deployed at sea to just over 1,000 in 2015. That corresponds to nearly 22 percent of the stockpile deployed at sea.

The just over 1,000 afloat warheads today may be less than during the Cold War, but it is roughly equivalent to the nuclear weapons stockpiles of Britain, China, France, India, Israel, Pakistan and North Korea combined.

Mediterranean Mystery

The declassification documents do not explain how the numbers are broken down. The “Atlantic,” “Pacific,” and “Mediterranean” regions are not the only areas where the U.S. Navy sent nuclear-armed warships. Afloat weapons in the Indian and Arctic oceans, for example, are not listed even though nuclear-armed warships sailed in both oceans. Similarly, the declassified documents show the number of afloat weapons in the Mediterranean suddenly dropping to zero in 1987, even though the U.S. Navy continued so deploy nuclear-armed vessels into the Mediterranean Sea.

During the naval deployments in support of Operation Desert Storm against Iraq in early 1991, for example, the aircraft carrier USS America (CV-66) deployed with its nuclear weapons division (W Division) and B61 nuclear strike bombs and B57 nuclear depth bombs. The W Division was still onboard when America deployed to Northern Europe and the Mediterranean in 1992 but had been disbanded by the time it deployed to the Mediterranean in 1993.

B61 and B57 nuclear weapons are displayed on board the USS America (CV-66) during its deployment to Operation Desert Storm in 1991. The nuclear division was also onboard in 1992 but gone in 1993.

As ships offloaded their weapons, the on-board nuclear divisions gradually were disbanded in anticipation of the upcoming denuclearization of the surface fleet. One of the last carriers to deploy with a W Division was the USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67), which upon its return to the United States from a Mediterranean deployment in 1992-1993 ceremoniously photographed the W crew with the sign: “USS John F. Kennedy, CV 67, last W-Division, 17 Feb. 93.” The following year, the Clinton administration publicly announced that all carriers and surface ships would be denuclearized.

The last nuclear weapons division on the USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) is disbanded in February 1993. The following year the entire surface fleet was denuclearized.

Since nuclear weapons clearly deployed to the Mediterranean Sea after the declassified documents showing zero afloat nuclear weapons in the area, perhaps the three categories “Atlantic,” “Pacific,” and “Mediterranean” refer to overall military organization: “Atlantic” might be weapons under the command of the Atlantic Fleet (LANTFLT); “Pacific” might refer to the Pacific Fleet (PACFLT); and “Mediterranean” might refer to the Sixth Fleet. Yet I’m not convinced that organization is the whole story; the Atlantic numbers didn’t suddenly increase when the Mediterranean numbers dropped to zero.

The declassified afloat numbers end in 1991. After that year the only nuclear weapons deployed at sea have been strategic weapons onboard ballistic missile submarines. Most of those deploy in the Atlantic and Pacific but have occasionally deployed into the Mediterranean even after the declassified documents list zero afloat weapons in that region, and even after the surface fleet was denuclearized.

In 1999, for example, the ballistic missile submarine USS Louisiana (SSBN-743) conducted a port visit to Souda Bay on Crete with it load of 24 Trident missiles and an estimated 192 warheads. The ship’s Command History states that the port visit, which took place December 12-16, 1999, occurred during the “Alert Strategic Deterrent Patrol in support of national tasking” that included a “Mediterranean Sea Patrol.”

Risks of Nuclear Accidents

Deploying nuclear weapons on ships and submarines created unique risks of accidents and incidents. Because warships sometimes collide, catch fire, or even sink, it was only a matter of time before the nuclear weapons they carried were threatened, damaged, or lost. This really happened.

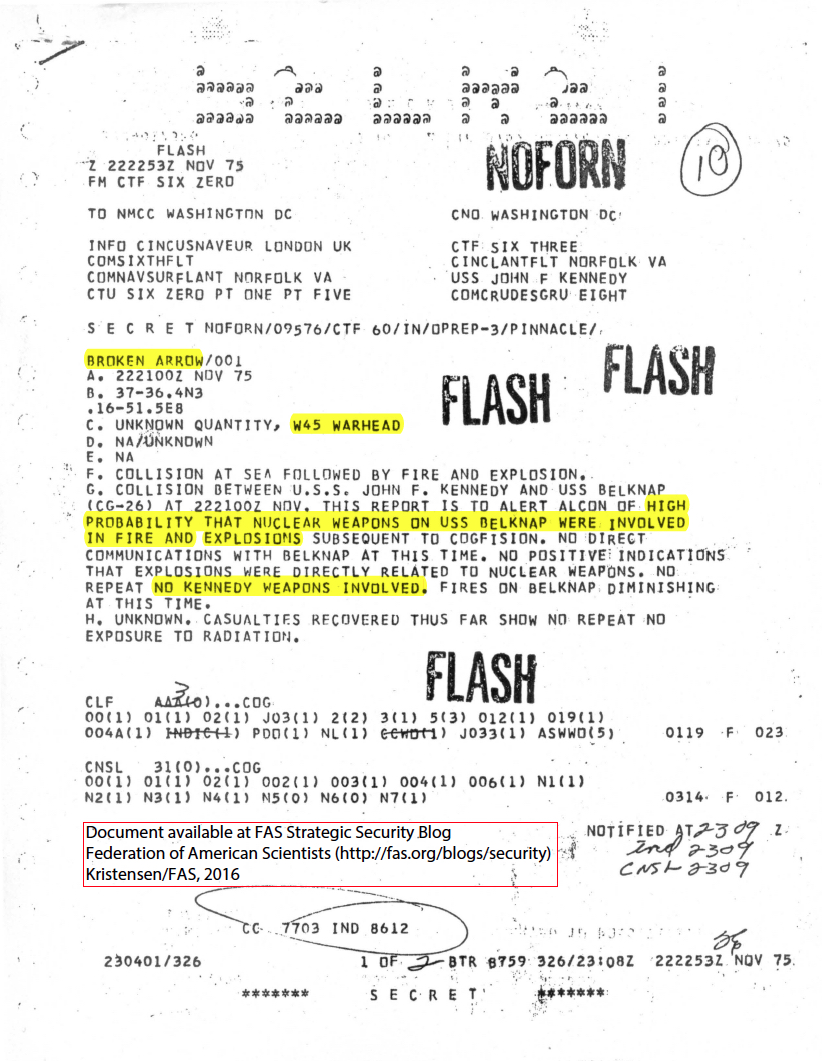

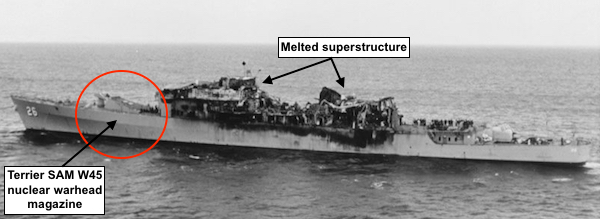

During night air exercises on November 22, 1975, for example, the aircraft carrier USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) and cruiser USS Belknap (CG-26) collided in rough seas 112 kilometers (70 miles) east of Sicily. The carrier’s flight deck cuts into the superstructure of the Belknap setting off fires on the cruiser, which burned out of control for two-and-one-half hours. The commander of Carrier Striking Force for the U.S. Sixth Fleet on board the Kennedy issues a Broken Arrow alert to higher commands stating there was a “high probability that nuclear weapons (W45 Terrier missile warheads) on the Belknap were involved in fire and explosions.” Eventually the fire was stopped only a few meters from Belknap’s nuclear weapons magazine.

The fire-damaged USS Belknap (CG-26) after colliding with USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) new Sicily in 1975. The fire stopped a few meters from the nuclear warhead magazine.

The Kennedy also carried nuclear weapons, approximately 100 gravity bombs for delivery by aircraft. The carrier caught fire but luckily it was relatively quickly contained. Another carrier, the USS Enterprise (CVN-65), had been less fortunate six years earlier when operating 112 kilometers (70 miles) southwest of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. A rocket on a F-4 Phantom aircraft exploded puncturing fuel tanks and starting violent fires that caused other rockets and bombs to explode. The explosions were so violent that they tore holes in the carrier’s solid steel deck and engulfed the entire back of the ship. The captain later said: “If the fire had spread to the hangar deck [below], we could have very easily lost the ship.” The Enterprise probably carried about 100 nuclear bombs and was powered by eight nuclear reactors.

The nuclear-armed and nuclear-powered USS Enterprise (CVN-65) burns off Hawaii on January 14, 1969. The carrier could have been lost, the captain said.

Dozens of nuclear weapons were lost at sea over the decades because they were on ships, submarines, or aircraft that were lost. On December 5, 1965, for example, while underway from operations off Vietnam to Yokosuka in Japan, an A-4E aircraft loaded with one B43 nuclear weapon rolled overboard from the Number 2 Elevator. The aircraft sank with the pilot and the bomb in 2,700 fathoms (4,940 meters) of water. The bomb has never been recovered. The Department of Defense reported the accident took place “more than 500 miles [805 kilometers] from land” when it revealed the accident in 1981. But Navy documents showed the accident occurred about 80 miles (129 kilometers) east of the Japanese Ryukyu Island chain, approximately 250 miles (402 kilometers) south of Kyushu Island, Japan, and about 200 miles (322 kilometers) east of Okinawa. Japan’s public policy and law prohibit nuclear weapons. (For a video if B43 aircraft carrier handling and A-4 loading, see this video.)

An A-4 Skyhawk with a B43 nuclear bomb under its belly rises on an elevator from the hangar deck to the flight deck on the USS Independence (CV-62) in an undated US Navy photo. In December 1965, a B43 attached to an A-4 rolled off the elevator on the USS Ticonderoga (CVA-14) while the carrier was on its way to Yokosuka in Japan.

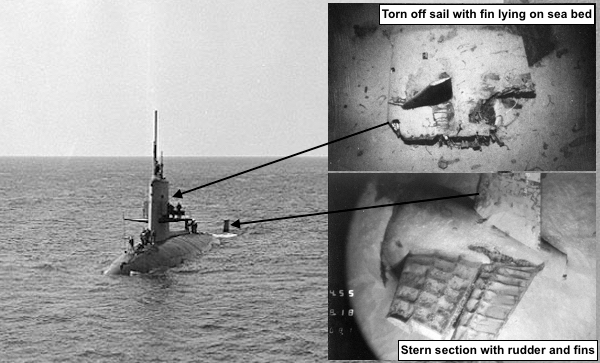

Three years later, on May 27, 1968, the nuclear-powered attack submarine USS Scorpion (SSN-589) suffered an accident and sank with all 99 men on board in the Atlantic Ocean approximately 644 kilometers (400 miles) southwest of the Azores. The Department of Defense in 1981 mentioned a nuclear weapons accident occurred in the Atlantic in the spring of 1968 but continues to classify the details. It is thought that two nuclear ASTOR torpedoes were on board the Scorpion when it sank.

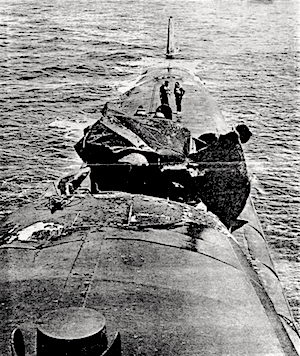

The USS Scorpion (SSN-589) photographed in the Mediterranean Sea in April 1968, one month before it sank in the Atlantic Ocean. The Navy later located and photographed the wreck (inserts).

Risks of Nuclear Incidents

Another kind of risk was that nuclear weapons onboard US warships could become involved in offensive maneuvers near Soviet warships that also carried nuclear weapons. Sometimes those nuclear-armed vessels collided – sometimes deliberately. Other times they were trapped in stressful situation. The presence of nuclear weapons could significantly increase the stakes and symbolism of the incidents and escalate a crisis.

Some of the most dramatic incidents happened during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 where crisis-stressed personnel on Soviet nuclear-armed submarines readied nuclear weapons for actual use as they were being hunted by US naval forces, many of which were also nuclear-armed. At the time there were approximately 750 U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in the Atlantic Ocean.

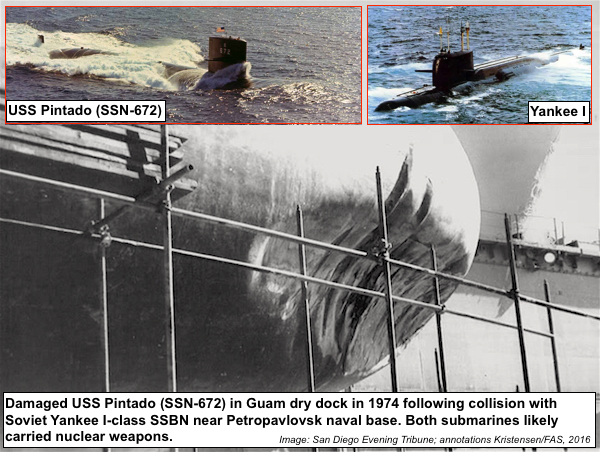

Less serious but nonetheless potentially dangerous incidents continued throughout the Cold War. In May 1974 the nuclear-powered attack submarine USS Pintado (SSN-672) collided almost head-on with a Soviet Yankee I-class ballistic missile submarine while cruising 200 feet (60 meters) below the surface in the approaches to the Petropavlovsk naval base on the Kamchatka Peninsula. The collision smashed much Pintado’s bow sonar, jammed shut a starboard side torpedo hatch, and damaged the diving plane. The Pintado, which probably carried 4-6 nuclear SUBROC missiles, sailed to Guam for seven weeks of repairs. The Soviet submarine, which probably carried its complement of 16 SS-N-6 ballistic missiles with 32 nuclear warheads, surfaced immediately and presumably limped back to port.

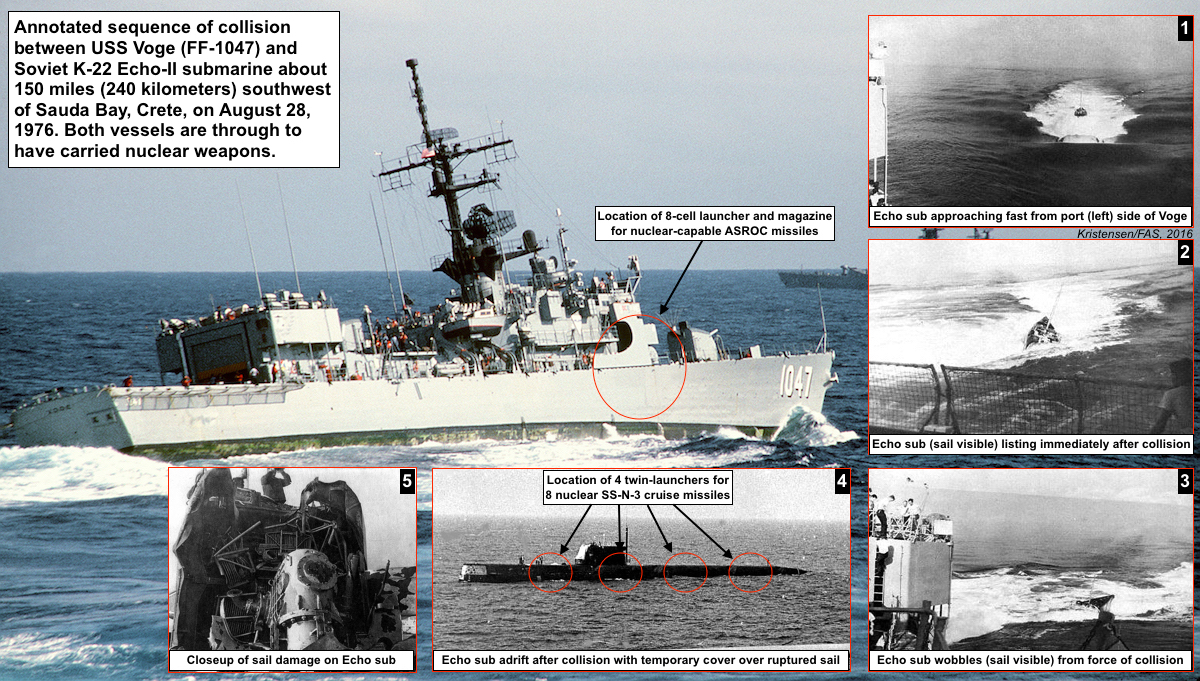

On August 22, 1976, for example, US anti-submarine forces in the Atlantic and Mediterranean had been tracking a Soviet nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed Echo II-class attack submarine for ten days. The Soviet sub partially surfaced alongside the US frigate USS Voge (FF-1047), then turned right and ran into the frigate. The collision tore off part the Voge’s propeller and punctured the hull. The Voge is thought to have carried nuclear ASROC anti-submarine rockets. At the time there were around 430 U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in the Mediterranean Sea. The Soviet submarine suffered serious damage to its sail and some to its front hull section. (For a US account of the incident, see here; a Russian account is here.)

A starboard view of the frigate USS VOGE (FF-1047) conducting a high speed evasive maneuver while operating with the aircraft carrier USS JOHN F. KENNEDY (CV-67) battle group.

Even toward the very end of the Cold War in the late-1980s, nuclear-capable warships continued to get involved in serious incidents at sea. During a Freedom of Navigation exercise in the Black Sea on February 12, 1988, the cruiser USS Yorktown (CG-48) and destroyer USS Caron (DD-970) were bumped by a Soviet Krivak-class frigate and a Mirka-class frigate, respectively. Both U.S. ships were equipped to carry the nuclear-capable ASROC missile and the Caron had completed a series of nuclear certification inspections prior to its departure from the United States. Yet the W44 warhead for the ASROC was in the process of being phased out and it is possible that the vessels did not carry nuclear warheads during the incident. The declassified data shows that the number of U.S. nuclear weapons in the Mediterranean dropped to zero in 1987. The Soviet Krivak frigate, however, probably carried nuclear anti-submarine weapons at the time of the collision.

Nuclear Diplomacy Headaches

In addition to the risks created by accidents and incidents, nuclear-armed warships were a constant diplomatic headache during the Cold War. Many U.S. allies and other countries did not allow nuclear weapons on their territory in peacetime but the United States insisted that it would neither confirm nor deny the presence of nuclear weapons anywhere. So good-will port visits by nuclear-armed warships instead turned into diplomatic nightmares as protestors battled what they considered blatant violations of the nuclear ban.

The port visit protests were endless, happening in countries all over the world. The national governments were forced to walk a fine line between their official public anti-nuclear policies and the secret political arrangements that allowed the weapons in anyway.

Public sentiments were particularly strong in Japan because it was the target of two nuclear weapon attacks in 1945. Japanese law banned the presence of nuclear weapons on its territory and required consultation prior to introduction, but the governments secretly accepted nuclear weapons in Japanese ports.

During the 1970s and early-1980s, opposition to nuclear ship visits grew in New Zealand and in 1984 culminating in the David Lange government banning visits by nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed vessels. The Reagan administration reacted angrily by ending defense cooperation with New Zealand under the ANZUS alliance. Only much later, during the Obama administration, have defense relations been restored.

The nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed attack submarine USS Haddo (SSN-604) is barraged by protestors during a port visit to Auckland in New Zealand in 1979.

The treatment of New Zealand was partially intended to deter other more important allies in Europe from adopting similar anti-nuclear legislation. But not surprisingly, the efforts backfired and instead increased opposition. In Denmark the growing evidence that nuclear weapons were actually being brought into Danish harbors despite its clear prohibition soon created political pressure to tighten up the ban. In 1988, this came to a head when a majority in the parliament adopted a resolution requiring the government to inform visiting warships of Denmark’s ban. The procedure did not require the captain to reveal whether his ship carried nuclear weapons, but the conservative government called an election and asked the United States to express its concern.

The crew of the nuclear-armed destroyer USS Conyngham (DDG-17) uses high-pressure hoses to wash anti-nuclear protestors off its anchor chain during a standoff in Aalborg, Denmark, in 1988.

Across the Danish Straits in Sweden, the growing evidence that non-nuclear policies were violated in 1990 resulted in the government party deciding to begin to reinforce Sweden’s nuclear ban. The policy would essentially have created a New Zealand situation in Europe, a political situation that was a direct threat to the US Navy sailing its nuclear warships anyway it wanted.

These diplomatic battles over naval nuclear weapons were so significant that many US officials gradually began to wonder if nuclear weapons at sea were creating more trouble than good.

After The Big Nuke Offload

Finally, on September 27, 1991, President George H.W. Bush announced during a primetime televised address that the United States would unilaterally offload all non-strategic nuclear weapons from its naval forces, bring all those weapons home, and destroy many of them. Warships would immediately stop loading nuclear weapons when sailing on overseas deployments and deployed vessels would offload their weapons as they rotated back to the United States. The offload was completed in mid-1992.

Two years later, the Clinton administration’s 1994 Nuclear Posture Review, decided that all surface ships would loose the capability to launch nuclear weapons. Only selected attack submarines would retain the capability to fire the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack sea-launched cruise missile (TLAM/N), but the weapons would be stored on land. Sixteen years later, in 2010, the Obama administration decided to retire the TLAM/N as well, ending decades of nuclear weapons deployments on ships, attack submarines, and on land-based naval air bases.

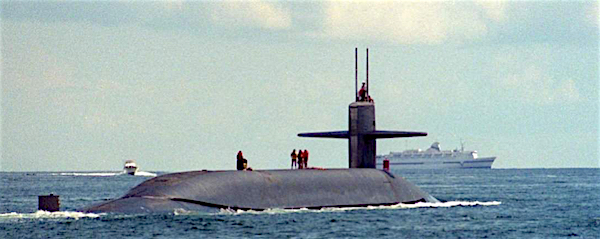

After the summer of 1992, only strategic submarines armed with long-range ballistic missiles have carried U.S. nuclear weapons at sea, a practice that is planned to continue through at least through the 2080s. These strategic submarines (SSBNs) have also been involved in accidents and incidents, risks that will continue as long as nuclear weapons are deployed at sea. Because secrecy is so much tighter for SSBN operations than for general naval forces, most accidents and incidents involving SSBNs probably escape public scrutiny. But a few reports, mainly collisions and groundings, have reached the public over the years.

USS Von Steuben (SSBN-632) after collision with tanker Sealady.

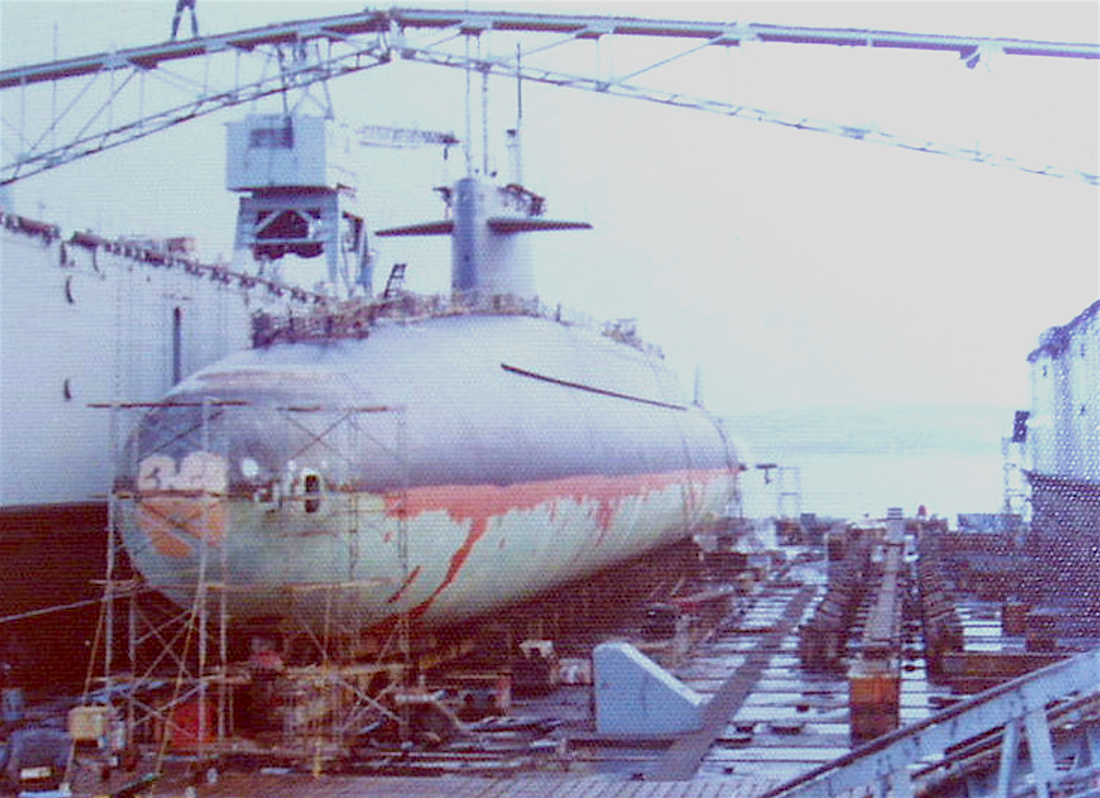

During a strategic deterrent patrol on August 9, 1968, the USS Von Steuben (SSBN-632) was struck by a submerged tow cable while operating submerged about 40 miles (64 kilometers) off the southern coast of Spain. As it surfaces, the submarine collides with the tanker Sealady, suffering damage to the superstructure and main deck (see image right). The submarine carried 16 Polaris A3 ballistic missiles with 48 nuclear warheads.

Two years later, on November 29, 1970, a fire breaks out onboard the nuclear submarine tender USS Canopus (AS-34) at the Holy Loch submarine base in Scotland. Two nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (USS Francis Scott Key (SSBN-657) and USS James K. Polk (SSBN-645)) were moored alongside Canapus. The Francis Scott Key cast off, but the Polk remained alongside. The fire burns out of control for four hours killing three men. The submarine tender carried nuclear missiles and warheads and the two submarines combined carried 32 Polaris A3 ballistic missiles with a total of 96 nuclear warheads.

Four years later, in November 1974, after having departed from its base at Holy Loch in Scotland, the ballistic missile submarine USS James Madison (SSBN-627) collides with a Soviet submarine in the North Sea. The collision left a nine-foot scrape in the Madison, which apparently dove onto the Soviet submarine, thought to have been a Victor-class nuclear-powered attack submarine. The Madison carried 16 Poseidon (C3) ballistic missiles with 160 nuclear warheads. The Soviet submarines probably carried nuclear rockets and torpedoes. Madison crew members called the incident The Victor Crash. Two days after the collision, the Madison enters dry dock at Holy Loch for a week of inspection and repairs.

The missile submarine USS James Madison (SSBN-627) in dry dock in Scotland in 1974 only days after it collided with a Soviet Victor-class nuclear-powered attack submarine in the North Sea.

After nuclear weapons were offloaded from surface ships and attack submarines in 1991-1992, nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines have continued to run aground or bump into other vessels from time to time.

On September 24, 1993, for example, after conducting a medical evacuation for a suck crew member, the ballistic missile submarine USS Maryland (SSBN-738) ran aground at Port Canaveral, Florida. The submarine was on a strategic deterrent patrol with 24 missiles onboard carrying an estimated 192 warheads. The Maryland eventually pulled free and continued the patrol two days later.

On March 19, 1998, while operating on the surface 125 miles (200 kilometers) off Long Island, New York, the ballistic missile submarine USS Kentucky (SSBN-737) was struck by the attack submarine USS San Juan (SSN-751). The Kentucky suffered damaged to its rudder and San Juan’s forward ballast tank was ruptured. In a typical display of silly secrecy, the Navy refused to say whether the Kentucky carried nuclear weapons. But it did; the Kentucky was in the middle of its 21st strategic deterrent patrol and carried its complement of 24 Trident II missiles with an estimated 192 nuclear warheads.

In 1998, the USS Kentucky (SSBN-737) carrying nearly 200 nuclear warheads collided with an attack submarine less than 230 miles (378 kilometers) from New York City.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The Obama administration has made an important contribution to nuclear policy by declassifying the documents with official numbers of US nuclear weapons deployed at sea during the Cold War. This adds an important chapter to the growing pool of declassified information about the history of the U.S. nuclear arsenal.

The new declassified information helps us better understand the extent to which nuclear weapons were involved in day-to-day operations around the world. Every day, nuclear-armed warships of the US and Soviet navies were rubbing up against each other on the high seas in gong-ho displays of national determination. Some saw it as necessary for nuclear deterrence; others as dangerous nuclear brinkmanship. Many of those who were on the ships submarines still get goosebumps when they talk about it and wonder how we survived the Cold War. The tactical naval nuclear weapons were considered more acceptable to use early in a conflict because there would be few civilian casualties. But any use would probably quickly have escalated into large-scale nuclear war and the end of the world as we know it.

The declassified information, when correlated with the many accidents and incidents that nuclear-armed ships and submarines were involved in over the years, also helps us remember a key lesson about nuclear weapons: when they are operationally deployed they will sooner or later be involved in accidents and incidents.

This is not just a Cold War lesson: thousands of nuclear weapons are still operationally deployed on ballistic missile submarines, on land-based ballistic missiles, and on bomber bases. And not just in the United States but also in Britain, France, and Russia. Some of those deployed weapons will have accidents in the future. (See here for the most recent.)

Moreover, growing tensions with Russia and China now make some ask if the United States needs to increase the role of its nuclear weapons and once again equip aircraft carriers with the capability to deliver nuclear bombs and once again develop and deploy nuclear land-attack sea-launched cruise missiles on attack submarines.

Doing so would be to roll back the clock and ignore the lessons of the Cold War and likely make the current tensions worse than they already are.

Instead, the United States should seek to work with Russia – even though it is challenging right now – to reduce deployed nuclear weapons and jointly try to persuade smaller nuclear-armed countries such as China, India, and Pakistan from increasing the operational readiness of their nuclear forces. That ought to be one thing Russia and the United States could actually agree on.

Background information:

- Department of Defense, “Nuclear Weapons Afloat: End of Fiscal Years 1953-1991,” n.d.

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: Declassified: US Nuclear Weapons at Sea During the Cold War, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, February 2016.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

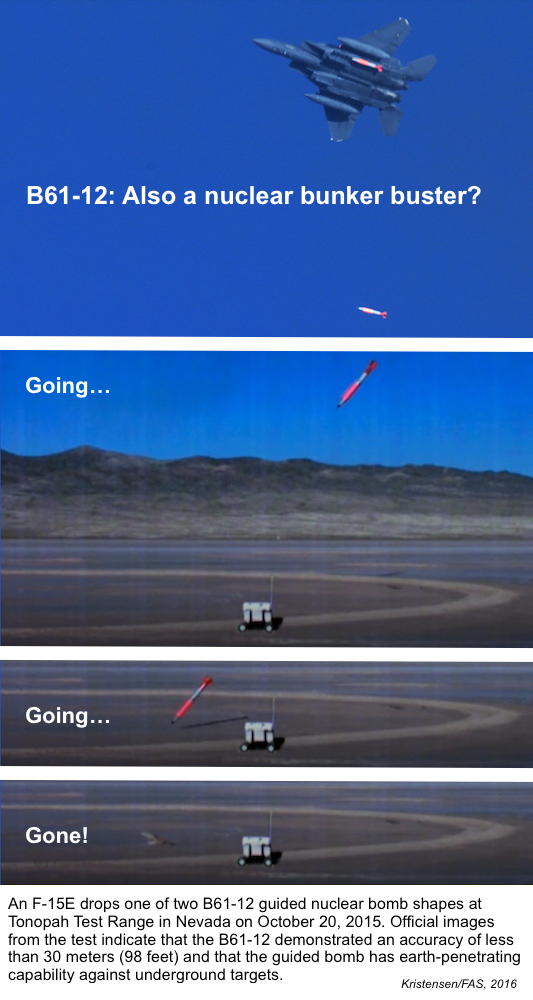

Video Shows Earth-Penetrating Capability of B61-12 Nuclear Bomb

The capability of the new B61-12 nuclear bomb seems to continue to expand, from a simple life-extension of an existing bomb, to the first U.S. guided nuclear gravity bomb, to a nuclear earth-penetrator with increased accuracy.

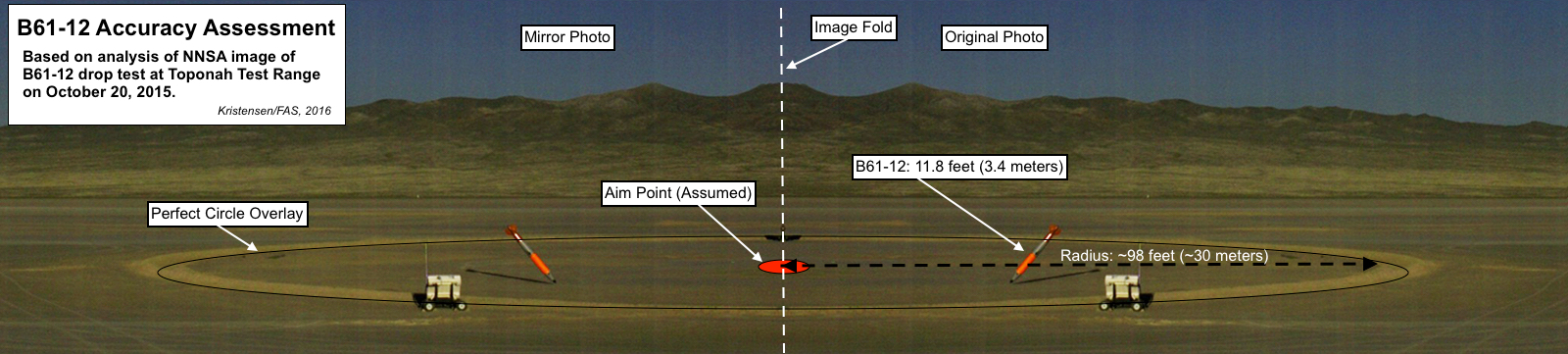

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) previously published pictures of the drop test from October 2015 that showed the B61-12 hitting inside the target circle but without showing the bomb penetrating underground.

But a Sandia National Laboratories video made available by the New York Times shows the B61-12 penetrating completely underground. (A longer version of the video is available at the Los Alamos Study Group web site.)

Implication of Earth-Penetration Capability

The evidence that the B61-12 can penetrate below the surface has significant implications for the types of targets that can be held at risk with the bomb. A nuclear weapon that detonates after penetrating the earth more efficiently transmits its explosive energy to the ground, thus is more effective at destroying deeply buried targets for a given nuclear yield. A detonation above ground, in contrast, results in a larger fraction of the explosive energy bouncing off the surface. Two findings of the 2005 National Academies’ study Effects of Earth-Penetrator and other Weapons are key:

“The yield required of a nuclear weapon to destroy a hard and deeply buried target is reduced by a factor of 15 to 25 by enhanced ground-shock coupling if the weapon is detonated a few meters below the surface.”

And

“Nuclear earth-penetrator weapons (EPWs) with a depth of penetration of 3 meters capture most of the advantage associated with the coupling of ground shock.”

Given that the length of the B61-12 is about three-and-a-half meters, and that the Sandia video shows the bomb disappearing completely beneath the surface of the Nevada desert, it appears the B61-12 will be able to achieve enhanced ground-shock coupling against underground targets in soil. We know that the B61-12 is designed to have four selectable explosive yields: 0.3 kilotons (kt), 1.5 kt, 10 kt and 50 kt. Therefore, given the National Academies’ finding, the maximum destructive potential of the B61-12 against underground targets is equivalent to the capability of a surface-burst weapon with a yield of 750 kt to 1,250 kt.

One of the bombs the Pentagon plans to retire after the B61-12 is deployed is the B83-1, which has a maximum yield of 1,200 kt.

Even at the lowest selective yield setting of only 0.3 kt, the ground-shock coupling of a B61-12 exploding a few meters underground would be equivalent to a surface-burst weapon with a yield of 4.5 kt to 7.5 kt.

Implications of Increased Accuracy

Existing B61 versions (B61-3, -4, 7, -10) are thought to have some limited earth-penetration capability but with much less accuracy than the B61-12. The only official nuclear earth-penetrator in the U.S. arsenal, the unguided B61-11, compensates for poor accuracy with a massive yield: 400 kt. The ground-shock coupling of 400 kt, using the National Academies’ finding, is equivalent to the effect of a surface-burst of 6 Megatons (MT) to 10 MT. The B61-11 replaced the old B53, the Cold War bunker buster bomb, which had a yield of 9 MT. The B61-11 can penetrate into frozen soil; it is yet unknown if the B61-12 has a similar capability. Currently there is no life-extension planned for the B61-11, which is not part of NNSA’s so-called 3+2 stockpile plan and is expected to be phased out when it expires in the 2030s.

What makes the B61-12 special is that the B61 capability is enhanced by the increased accuracy provided by the new guided tail kit assembly, a unique feature of the new weapon. The combination of increased accuracy with earth-penetration and low-yield options provides for unique targeting capabilities. Moreover, while the B61-11 can only be delivered by the B-2 strategic bomber, the B61-12 will be integrated on virtually all nuclear-capable U.S. and NATO aircraft: B-2, LRS-B (next-generation long-range bomber), F-35A, F-16, F-15E, and PA-200 Tornado.

How accurate the B61-12 will be is a secret. In an article from 2011 we estimated the accuracy might be on the order of 30-plus meters. Back then no test drop had been conducted and we didn’t have imagery. But now we do.

We cannot see with certainty on the NNSA photo and Sandia video how accurate the November 2015 drop test was. The video and image clearly show the B61-12 impacting the ground well within a large circle. Unfortunately the imagery does not show the full circle and the low angle makes it hard to determine the diameter. But by flipping the image horizontally and combining the copy with the original, the two appear to make a nearly perfect circle. Because we know the length of the B61-12 (11.8 feet; 3.4 meters), it appears the circle has a diameter of approximately 197 feet (60 meters). Since the point of impact is well within circle (roughly one bomb length inside), the B61-12 appears to have hit less than 100 feet (30 meters) from the center of the circle (see analysis of NNSA photo below).

Accuracy of a weapon is expressed as CEP (Circular Error Probability), which is defined as the radius of a circle centered at the target aim-point within which 50% of the weapons will fall. Formally estimating the accuracy of the B61-12 requires more information than the ground zero location of the drop test in the November 2015 event. Even so, the image indicates that at least the November 2015 drop test impacted well within the 30-meter diameter circle.

Little is known in public about the accuracy of nuclear gravity bombs. But information previously released by the U.S. Air Force to Kristensen under the Freedom of Information Act states that drop tests in the late-1990s normally achieved an accuracy of 380 feet (116 meters) for both high- and low-altitude releases and occasionally down to around 300 feet (91 meters) for low-altitude bombing runs.

In other words, although formal and more comprehensive data is missing, the November 2015 drop test indicates a B61-12 performance three times more accurate than existing non-guided gravity bombs.

That increased accuracy and earth-penetration capability will allow strike planners to chose lower selectable yields than are needed with the accuracy of current B61 and B83 bombs to destroy the same targets. Selecting lower yields will reduce the radioactive fallout from an attack, a feature that would make a B61-12 attack more attractive to military planners and less controversial to political decision makers.

Contradictions

The ability of the B61-12 to penetrate below the surface before detonating as seen on the video will further increase the capability against underground targets, especially when combined with the improved accuracy. This opens up a range of options for destroying underground targets with lower selectable nuclear yield settings than with the bombs in the current arsenal. We believe this constitutes an enhanced military capability that is in conflict with the Obama administration’s stated policy not to develop new capabilities for nuclear weapons.

The New York Times article is well written because it captures the contradiction between the denial by some officials (in this case NNSA’s Madelyn Creedon) that the B61-12 has new military capabilities while others (in this case former under secretary of defense for policy James Miller) seem to think it is a good thing that it does.

To that end the article is astute because it quotes the White House pledge not to pursue new military capabilities:

“The United States will not develop new nuclear warheads or pursue new military mission or new capabilities for nuclear weapons.”

…instead of using the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) Report formulation:

“The United States will not develop new nuclear warheads. Life Extension Programs (LEPs) will use only nuclear components based on previously tested designs, and will not support new military missions or provide for new military capabilities.”

This is important because the NPR formulation is a little less clear and is being used by some officials and defense contractors to argue that the pledge not to pursue new military missions or new military capabilities only refers to the warhead itself and not nuclear weapons in general. That may seem pedantic so the White House statement helps clarify, in case anyone is confused, that the policy indeed applies to “weapons” and not just “warheads.”

The officials who claim the B61-12 will not have new military capabilities say so because the United States already has the capability to hold at risk surface and underground targets, or to the fact that the warhead within the bomb –the so-called “physics package” –remains the same Cold War design. But the combination of increased accuracy and limited earth-penetrating capability allow the B61-12 to threaten below-ground structures with less radioactive fallout. That is a new military capability.

Back in 2011, before the B61-12 development program had progressed to the point of no return, FAS sent a letter to the White House and the Office of the Secretary of Defense pointing out the contradiction with the administration’s policy and implications for nuclear strategy. They never responded.

Worrying about the Bomb

The B61-12 earth-penetration capability may be less than the existing B61-11 earth-penetrator and the accuracy less than a conventional GPS-guided smart bomb, but the Sandia video shows a versatile new weapon that is intended for deployment on both strategic and non-strategic aircraft in the United States and Europe.

Such a capability begs the question of which targets in which countries are envisioned for B61-12 missions, and under what circumstances could use of such a weapon be ordered by the President? The National Academies’ study also found that earth penetration by a nuclear weapon could not contain the effects of the nuclear explosion, and that casualties would likely be the same as if the weapon were detonated at the surface of the earth. These findings particularly speak to the implications of dropping the B61-12 on a bunker located underneath a city.

Moreover, the significant improvements being made to non-nuclear earth-penetrators begs the question why it is necessary to enhance the capabilities of the B61 gravity bomb in the first place.

Both the United State and Russia (and the other nuclear-armed states) have extensive and expensive nuclear force modernization programs underway. What we are seeing today lies somewhere between parallel efforts to refurbish Cold War arsenals and the emergence of a new arms competition fueled by enhancements to existing weapons or production of new or significantly modified types. These enhancements are being developed without nuclear test explosions.

Inevitably the most important capabilities for nuclear deterrent forces are stability, control and safety – daily operational procedures embodying restraint, and strong channels of communication between nuclear weapon states with safeguards against accidental or unauthorized use of nuclear weapons. This area needs a lot of work right now as US-Russian relations continue to fray, already triggering calls from some analysts to further enhance nuclear weapons.

The Sandia video of the B61-12 slipping into the earth like a hot knife into butter doesn’t make the situation better.

* Matthew McKinzie is the nuclear program director at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Kalibr: Savior of INF Treaty?

By Hans M. Kristensen

With a series of highly advertised sea- and air-launched cruise missile attacks against targets in Syria, the Russian government has demonstrated that it doesn’t have a military need for the controversial ground-launched cruise missile that the United States has accused Russia of developing and test-launching in violation of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty.

Moreover, President Vladimir Putin has now publicly confirmed (what everyone suspected) that the sea- and air-launched cruise missiles can deliver both conventional and nuclear warheads and, therefore, can hold the same targets at risk. (Click here to download the Russian Ministry of Defense’s drawing providing the Kalibr capabilities.)

The United States has publicly accused Russia of violating the INF treaty by developing, producing, and test-launching a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) to a distance of 500 kilometers (310 miles) or more. The U.S. government has not publicly identified the missile, which has allowed the Russian government to “play dumb” and pretend it doesn’t know what the U.S. government is talking about.

The lack of specificity has also allowed widespread speculations in the news media and on private web sites (this included) about which missile is the culprit.

As a result, U.S. government officials have now started to be a little more explicit about what the Russian missile is not. Instead, it is described as a new “state-of-the-art” ground-launched cruise missile that has been developed, produced, test-launched – but not yet deployed.

Whether or not one believes the U.S. accusation or the Russian denial, the latest cruise missile attacks in Syria demonstrate that there is no military need for Russia to develop a ground-launched cruise missile. The Kalibr SLCM finally gives Russia a long-range conventional SLCM similar to the Tomahawk SLCM the U.S. navy has been deploying since the 1980s.

What The INF Violation Is Not

Although the U.S. government has yet to publicly identify the GLCM by name, it has gradually responded to speculations about what it might be by providing more and more details about what the GLCM is not. Recently two senior U.S. officials privately explained about the INF violation that:

- it is not the R-500 cruise missile (Iskander-K);

- it is not the RS-26 road-mobile ballistic missile;

- it is not a sea-launched cruise missile test-launched from a ground launcher;

- it is not an air-launched cruise missile test-launched from a ground launcher;

- it is not a technical mistake;

- it is not one or two test slips;

- it is in development but has not yet been deployed.

Rose Gottemoeller, the U.S. under secretary of state for and international security, said in response to a question at the Brookings Institution in December 2014: “It is a ground-launched cruise missile. It is neither of the systems that you raised. It’s not the Iskander. It is not the other one, X-100. Is that what it is? Yeah, I’ve seen some of those reflections in the press and it’s not that one.” [The question was in fact about the X-101, sometimes used as a designation for the air-launched Kh-101, a conventional missile that also exists in a nuclear version known as the Kh-102.]

The explicit ruling out of the Iskander as an INF violation is important because numerous news media and private web sites over the past several years have claimed that the ballistic missile (SS-26; Iskander-M) has a range of 500 km (310 miles), possibly more. Such a range would be a violation of the INF. In contrast, the U.S. National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has consistently listed the range as 300 km (186 miles). Likewise, the cruise missile known as Iskander-K (apparently the R-500) has also been widely rumored to have a range that violates the INF, some saying 2,000 km (1,243 miles) and some even up to 5,000 kilometers (3,107 miles). But Gottemoeller’s statement seems to undercut such rumors.

Gottemoeller told Congress in December 2015 that “we had no information or indication as of 2008 that the Russian Federation was violating the treaty. That information emerged in 2011.” And she repeated that “this it is not a technicality, a one off event, or a case of mistaken identity,” such as a SLCM launched from land.

Instead, U.S. officials have begun to be more explicit about the GLCM, saying that it involves “a state-of-the-art ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has tested at ranges capable of threatening most of [the] European continent and out allies in Northeast Asia” (emphasis added). Apparently, the “state-of-the-art” phrase is intended to underscore that the missile is new and not something else mistaken for a GLCM.

Some believe the GLCM may be the 9M729 missile, and unidentified U.S. government sources say the missile is designated SSC-X-8 by the U.S. Intelligence Community.

Forget GLCM: Kalibr SLCM Can Do The Job

Whatever the GLCM is, the Russian cruise missile attacks on Syria over the past two months demonstrate that the Russian military doesn’t need the GLCM. Instead, existing sea- and air-launched cruise missiles can hold at risk the same targets. U.S. intelligence officials say the GLCM has been test-launched to about the same range as the Kalibr SLCM.

Following the launch from the Kilo-II class submarine in the Mediterranean Sea on December 9, Putin publicly confirmed that the Kalibr SLCM (as well as the Kh-101 ALCM) is nuclear-capable. “Both the Calibre [sic] missiles and the Kh-101 [sic] rockets can be equipped either with conventional or special nuclear warheads.” (The Kh-101 is the conventional version of the new air-launched cruise missile, which is called Kh-102 when equipped with a nuclear warhead.)

The conventional Kalibr version used in Syria appears to have a range of up to 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles). It is possible, but unknown, that the nuclear version has a longer range, possibly more than 2,500 kilometers (1,550 miles). The existing nuclear land-attack sea-launched cruise missile (SS-N-21) has a range of more than 2,800 kilometers (the same as the old AS-15 air-launched cruise missile).

The Russian navy is planning to deploy the Kalibr widely on ships and submarines in all its five fleets: the Northern Fleet on the Kola Peninsula; the Baltic Sea Fleet in Kaliningrad and Saint Petersburg; the Black Sea Fleet bases in Sevastopol and Novorossiysk; the Caspian Sea Fleet in Makhachkala; and the Pacific Fleet bases in Vladivostok and Petropavlovsk.

The Russian navy is already bragging about the Kalibr. After the Kalibr strike from the Caspian Sea, Vice Admiral Viktor Bursuk, the Russian navy’s deputy Commander-in-Chief, warned NATO: “The range of these missiles allows us to say that ships operating from the Black Sea will be able to engage targets located quite a long distance away, a circumstance which has come as an unpleasant surprise to counties that are members of the NATO block.”

With a range of 2,000 kilometers the Russian navy could target facilities in all European NATO countries without even leaving port (except Spain and Portugal), most of the Middle East, as well as Japan, South Korea, and northeast China including Beijing (see map below).

As a result of the capabilities provided by the Kalibr and other new conventional cruise missiles, we will probably see many of Russia’s old Soviet-era nuclear sea-launched cruise missiles retiring over the next decade.

The nuclear Kalibr land-attack version will probably be used to equip select attack submarines such as the Severodvinsk (Yasen) class, similar to the existing nuclear land-attack cruise missile (SS-N-21), which is carried by the Akula, Sierra, and Victor-III attack submarines, but not other submarines or surface ships.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Now that Russia has demonstrated the capability of its new sea- and air-launched conventional long-range cruise missiles – and announced that they can also carry nuclear warheads – it has demonstrated that there is no military need for a long-range ground-launched cruise missile as well.

This provides Russia with an opportunity to remove confusion about its compliance with the INF treaty by scrapping the illegal and unnecessary ground-launched cruise missile project.

Doing so would save money at home and begin the slow and long process of repairing international relations.

Moreover, Russia’s widespread and growing deployment of new conventional long-range land-attack and anti-ship cruise missiles raises questions about the need for the Russian navy to continue to deploy nuclear cruise missiles. Russia’s existing five nuclear sea-launched cruise missiles (SS-N-9, SS-N-12, SS-N-19, SS-N-21 and SS-N-22) were all developed at a time when long-range conventional missiles were non-existent or inadequate.

Those days are gone, as demonstrated by the recent cruise missile attacks, and Russia should now follow the U.S. example from 2011 when it scrapped its nuclear Tomahawk sea-launched cruise missile. Doing so would reduce excess types and numbers of nuclear weapons.

Background:

- Russian Nuclear Forces, 2015, FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, 2015

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Adjusting NATO’s Nuclear Posture

By Hans M. Kristensen

The new Polish government caused a stir last weekend when deputy defense minister Tomasz Szatkowski said during an interview with Polsat News 2 that Poland was taking “concrete steps” to consider joining NATO’s so-called nuclear sharing program.

The program is a controversial arrangement where the United States makes nuclear weapons available for use by a handful of non-nuclear NATO countries.

The Polish Ministry of Defense quickly issued a denial saying Poland “is not engaged in any work aimed at joining NATO’s nuclear sharing program.”

Mr. Szatkowski’s statement, the Ministry said, “should be seen in the context of recent remarks made by serious Western think tanks, which point to deficits in NATO’s nuclear deterrent capability on its eastern flank.”

No Smoke Without A Fire

NATO has stated that it has no plans or intensions to deploy nuclear weapons further east in new NATO countries. Despite the Polish denial, however, Mr. Szatkowski’s statement didn’t come out of thin air but reflects deepening discussions within NATO about how the alliance should adjust its nuclear posture in Europe in response to Russia’s recent military operations and statements.

Only a few weeks ago senior U.K. officials said NATO was actively considering whether to reinstate nuclear escalation exercises in Europe to counter Russia. “Since the end of the Cold War, NATO has done conventional exercising and nuclear exercising, both, but not exercised the transition from one to the other,” said Sir Adam Thomson, the British permanent representative to NATO. That recommendation is now being looked at he said and added: “It is safe to say the UK does see merit in making sure we know how, as an Alliance, to transition up the escalatory ladder in order to strengthen our deterrence.” Defence Secretary Michael Fallon added: “We have to know how they fit together, nuclear and conventional.”

The British statements followed preliminary NATO discussion in June and more formal talks in October after warnings in February that Russia was adjusting its nuclear posture. Back then Fallon explained there were three concerns: “first that they (the Russians) may have lowered the threshold for use of nuclear. Secondly, they seem to be integrating nuclear with conventional forces in a rather threatening way and [third]… at a time of fiscal pressure they are keeping up their expenditure on modernizing their nuclear forces.”

While the diplomats in public are talking about considerations, the military has already begun to adjust the nuclear posture. As part of Operation Atlantic Resolve, a new set of military operations and exercises recently created to provide “a unified response to revanchist Russia,” U.S. European Command (EUCOM) has quietly “forged a link between STRATCOM Bomber Assurance and Deterrence missions to NATO regional exercises” to beef up the NATO nuclear deterrence mission.

One of the first examples of this new “link” was Operation Polar Growl, a bomber exercise in April where four B-52 bombers took off from the United States and flew a non-stop strike mission over the North Pole and North Sea. The bombers did not carry nuclear weapons on the exercise but were equipped to carry a total of 80 air-launched cruise missiles with a total explosive power equivalent to 1,000 Hiroshima bombs – a subtle warning to Putin not seen since the Cold War.

Two B-52 bombers take off from Barksdale AFB on April 1, 2015 as part of Exercise Polar Growl over the North Pole and North Sea.

Conclusions and Recommendations

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, increased military operations, and explicit nuclear threats, General Philip Breedlove, the head of U.S. European Command (EUCOM) and NATO’s military commander, told the US Congress that the crisis in Europe is “not based on the nuclear piece. That’s not what worries me.” And U.S. Defense Secretary Ashton Carter declared that “In our response [to Russia], we will not rely on the Cold War play book.”

Yet NATO is starting to adjust its nuclear posture in Europe in ways that seem similar (but far from identical) to the Cold War play book: increased reliance on U.S. nuclear forces, adjustment of strategy and planning, more exercises and rotational deployments of nuclear-capable forces.

The statement by Polish deputy defense minister Tomasz Szatkowski is but the latest sign of that development.

It is unlikely that NATO will broaden its nuclear sharing arrangement to include Poland. It is already a member of NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group where it participates and votes on issues related to NATO nuclear planning. And Poland already participates in the so-called SNOWCAT program where it contributes non-nuclear capabilities in support of the nuclear mission in Europe but is not directly nuclear tasked. Last year we saw Polish F-16s participate in NATO’s nuclear strike exercise for the first time in SNOWCAT role.

Taking this one step further for Poland to become part of the nuclear sharing arrangement similar to Belgium, Germany, Holland, Italy and Turkey that store US nuclear weapons on their territory, equip their national jets and train their national pilots with the capability to deliver U.S. nuclear weapons, would be an unnecessary and counterproductive overreaction to Putin’s unacceptable military escapades.

It would worsen, not improve, security in Europe, waste resources that are needed for conventional forces, and deepen the political and military crisis between NATO and Russia. It would be akin to Russia deciding to provide nuclear weapons for Belarusian fighter jets.

Moreover, while the existing nuclear sharing arrangements in NATO (all of which are bi-lateral arrangements between the United States and the host country) date back from before the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) came into effect and therefore was accepted by the treaty regime, broadening the arrangement to Poland (or anyone else) would be a new situation and therefore a violation of the NPT.

Yet some NATO officials, former government officials, and academics, have been trying for years to persuade NATO to increase – or at least not reduce – reliance on nuclear weapons in Europe. For them, Putin’s actions represent a refreshing opportunity to get what they wanted anyway. The NATO Summit in Warsaw next summer is expected to decide on how far to go.

NATO should reject attempts to reinvigorate the nuclear posture in Europe and instead focus its military planning where it matters: enhancing conventional capabilities (to the extent it doesn’t further increase Russian reliance on nuclear weapons) with U.S. nuclear forces (and to a lesser extent those of Britain and France) providing an assured nuclear retaliatory capability in the background.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

General Cartwright Confirms B61-12 Bomb “Could Be More Useable”

By Hans M. Kristensen

General James Cartwright, the former commander of U.S. Strategic Command and former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, confirmed in an interview with PBS Newshour that the increased accuracy of the new guided B61-12 nuclear bomb could make the weapon “more useable” to the president or national-security making process.

GEN. JAMES CARTWRIGHT (RET.), Former Commander, U.S. Strategic Command: If I can drive down the yield, drive down, therefore, the likelihood of fallout, et cetera, does that make it more usable in the eyes of some — some president or national security decision-making process? And the answer is, it likely could be more usable.

Cartwright’s confirmation follows General Norton Schwartz, the former U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff, who in 2014 assessed that the increased accuracy would have implications for how the military thinks about using the B61. “Without a doubt. Improved accuracy and lower yield is a desired military capability. Without a question,” he said.

In an article in 2011 I first described the potential effects the increased accuracy provided by the new guided tail kit and the option to select lower yields in nuclear strike could have for nuclear planning and the perception of how useable nuclear weapons are. I also discuss this in an interview on the PBS Newshour program.

In contrast to the enhanced military capabilities offered by the increased accuracy of the B61-12, and its potential impact on nuclear planning confirmed by generals Cartwright and Schwartz, it is U.S. nuclear policy that nuclear weapons “Life Extension Programs…will not support new military missions or provide for new military capabilities,” as stated in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review Report.

The effect of the B61-12 modernization will be most dramatic in Europe where less accurate older B61s are currently deployed at six bases in five countries for delivery by older aircraft. The first B61-12 is scheduled to roll off the assembly line in 2020 and enter the stockpile in 2024 after which some of the estimated 480 bombs to be built and, under current policy, would be deployed to Europe for deliver by the new F-35A Lightning II fifth-generation fighter-bomber and (for a while) older aircraft.

For background information, see:

- B61 LEP: Increasing NATO Nuclear Capability and Precision Low-Yield Strikes

- General Confirms Enhanced Targeting Capabilities of B61-12 Nuclear Bomb

- Upgrades At US Nuclear Bases Acknowledge Security Risk

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Upgrades At US Nuclear Bases In Europe Acknowledge Security Risk

Security upgrades underway at U.S. Air Force bases in Europe indicate that nuclear weapons deployed in Europe have been stored under unsafe conditions for more than two decades.

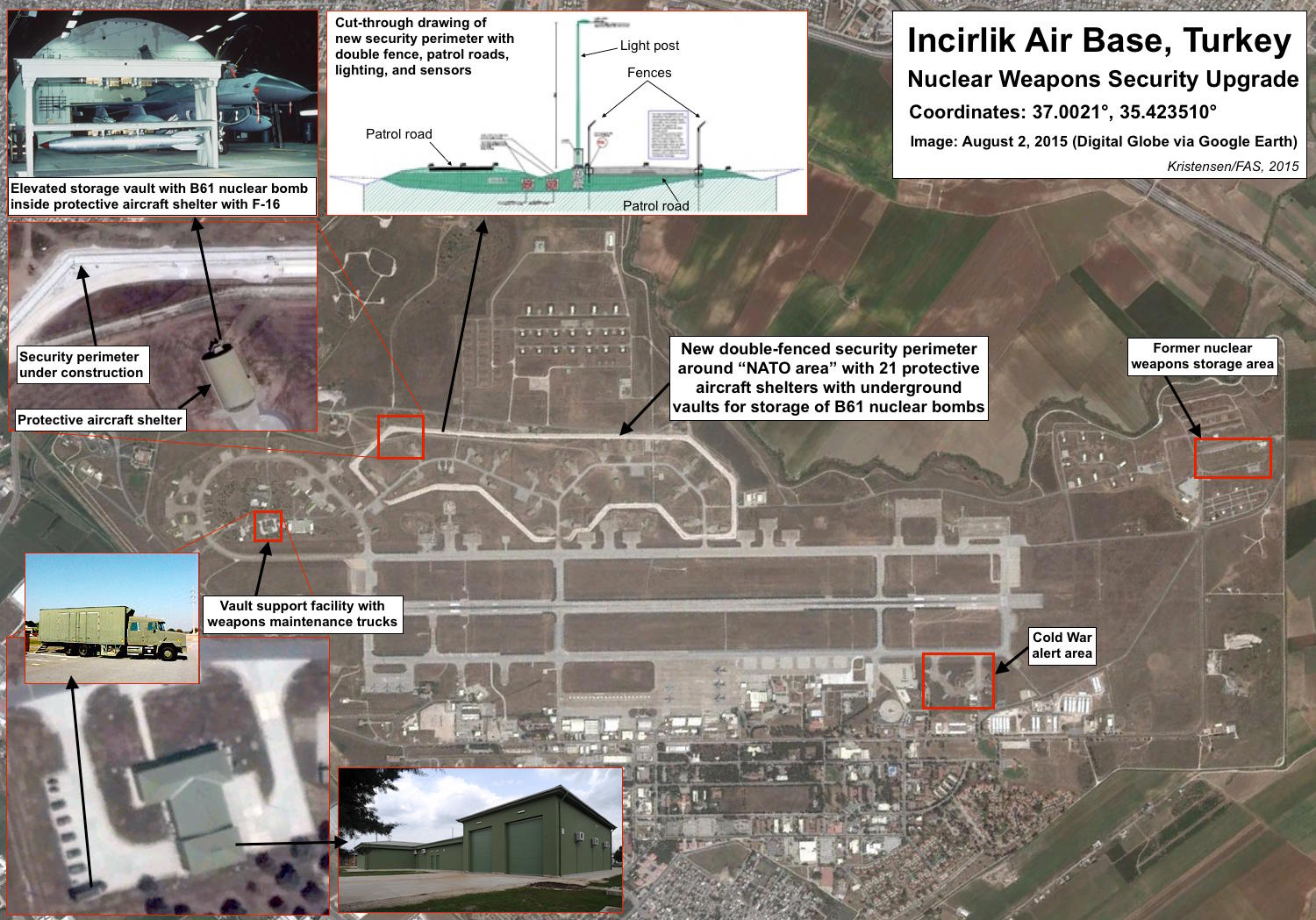

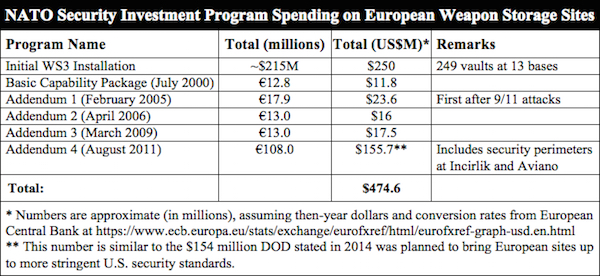

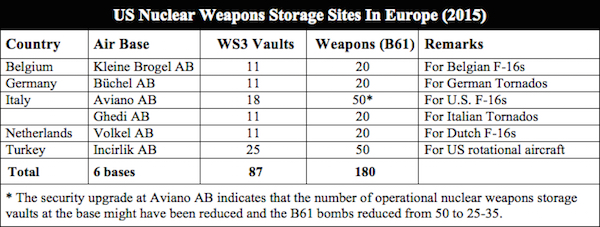

Commercial satellite images show work underway at Incirlik Air Base in Turkey and Aviano Air Base in Italy. The upgrades are intended to increase the physical protection of nuclear weapons stored at the two U.S. Air Force Bases.

The upgrades indirectly acknowledge that security at U.S. nuclear weapons storage sites in Europe has been inadequate for more than two decades.

And the decision to upgrade nuclear security perimeters at the two U.S. bases strongly implies that security at the other four European host bases must now be characterized as inadequate.

Security challenges at Incirlik AB are unique in NATO’s nuclear posture because the base is located only 110 kilometers (68 miles) from war-torn Syria and because of an ongoing armed conflict within Turkey between the Turkish authorities and Kurdish militants. The wisdom of deploying NATO’s largest nuclear weapons stockpile in such a volatile region seems questionable. (UPDATE: Pentagon orders “voluntary departure” of 900 family members of U.S. personnel stationed at Incirlik.)

Upgrades at Incirlik Air Base

Incirlik Air Base is the largest nuclear weapons storage site in Europe with 25 underground vaults installed inside as many protective aircraft shelters (PAS) in 1998. Each vault can hold up to four bombs for a maximum total base capacity of 100 bombs. There were 90 B61 nuclear bombs in 2000, or 3-4 bombs per vault. This included 40 bombs earmarked for deliver by Turkish F-16 jets at Balikesir Air Base and Akinci Air Base. There are currently an estimated 50 bombs at the base, or an average of 2-3 bombs in each of the 21 vaults inside the new security perimeter.

The new security perimeter under construction surrounds the so-called “NATO area” with 21 aircraft shelters (the remaining four vaults might be in shelters inside the Cold War alert area that is no longer used for nuclear operations). The security perimeter is a 4,200-meter (2,600-mile) double-fenced with lighting, cameras, intrusion detection, and a vehicle patrol-road running between the two fences. There are five or six access points including three for aircraft. Construction is done by Kuanta Construction for the Aselsan Cooperation under a contract with the Turkish Ministry of Defense.

A major nuclear weapons security upgrade is underway at the U.S. Air Force base at Incirlik in Turkey.

In addition to the security perimeter, an upgrade is also planned of the vault support facility garage that is used by the special weapons maintenance trucks (WMT) that drive out to service the B61 bombs inside the aircraft shelters. The vault support facility is located outside the west-end of the security perimeter. The weapons maintenance trucks themselves are also being upgraded and replaced with new Secure Transportable Maintenance System (STMS) trailers.